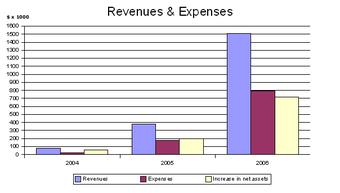

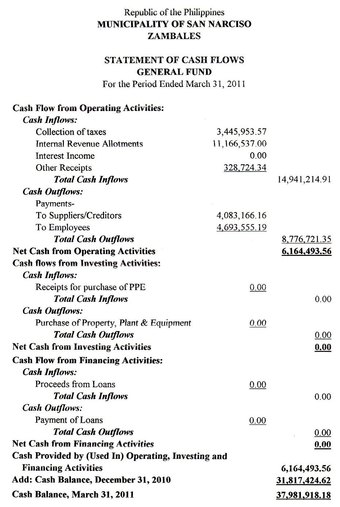

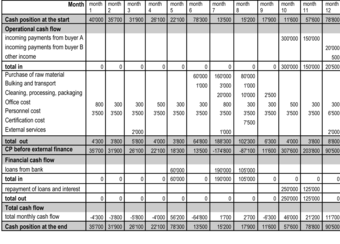

Operating cash flow refers to the amount of cash a company generates from the revenues it brings in, excluding costs associated with long-term investment on capital items or investment in securities. The International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) defines operating cash flow as cash generated from operations less taxation and interest paid, investment income received and less dividends paid. Business operations have daily cash inflows and outflows. Cash inflows come from cash sales of inventory, collection of credit sales, sales of other assets, and funds obtained through credit financing. Cash outflows occur due to cash payment of business expenses, purchase of assets, and payment on debt .

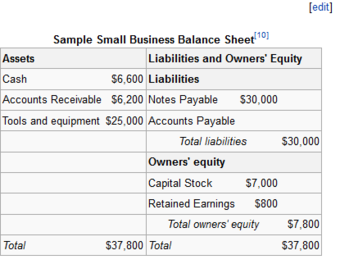

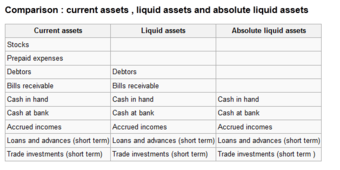

“Cash and cash equivalents” on the balance sheet are the most liquid assets found on this statement. They are assets that are readily convertible into cash, such as money market holdings, short-term government bonds or Treasury bills, marketable securities, and commercial paper. Cash equivalents are distinguished from other investments through their short-term existence; they mature within three months and have insignificant risk of change in value.

Cash and cash equivalents are also used in the contexts of payments and payment transactions and refer to currency, money orders, paper checks, and stored value products, such as gift certificates and gift cards.

Cash flow forecasting or cash flow management is a key aspect of the financial management of a business, because planning for future cash requirements can help to avoid a liquidity crisis in the business. Cash flow is the life-blood of all businesses, particularly start-ups and small enterprises. As a result, it is essential that management forecast (predict) what is going to happen to cash flow to make sure the business has enough to survive.

Capital expenditures (“CAPEX”) are one-time expenses incurred for the purchase of land, buildings, construction of buildings and other assets, and equipment used in the production of goods or in the rendering of services. In short, capital expenditures are the total costs needed to bring a project to a commercially operable status.

Whether a particular cost is a CAPEX or not depends on many factors, such as accounting rules, tax laws, and materiality. CAPEX include expenses for tangible goods, such as the purchase of plants and machinery, as well as expenses for intangibles assets, such as trademarks and software development. CAPEX are not limited to the initial construction of a building or other asset and should include other expense items, such as interest incurred during the construction phase.

A CAPEX cannot be deducted as an expense in the year in which it is paid or incurred and must be capitalized. The general rule is that if the acquired property’s useful life is longer than the taxable year, then the cost must be capitalized. The CAPEX costs are then amortized or depreciated over the life of the asset in question. The following capital expenditures are capitalized:

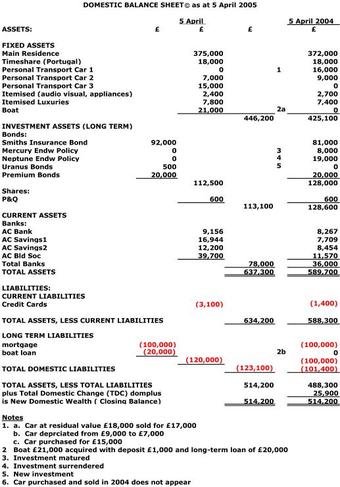

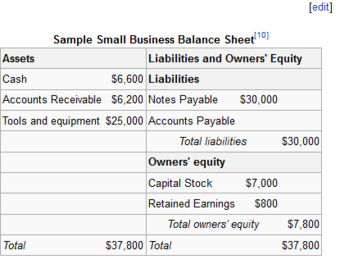

An ongoing question for the accounting of any company is whether certain expenses should be capitalized. Costs that are expensed in a particular month simply appear on the financial statement as a cost incurred that month. Costs that are capitalized, however, are amortized or depreciated over multiple years. Capitalized expenditures show up on the balance sheet. Most ordinary business expenses are clearly either expensable or capitalizable, but some expenses could be treated either way, according to the preference of the company. Capitalized interest, if applicable, is also spread out over the life of the asset.The counterpart of capital expenditure is operational expenditure (“OpEx”).

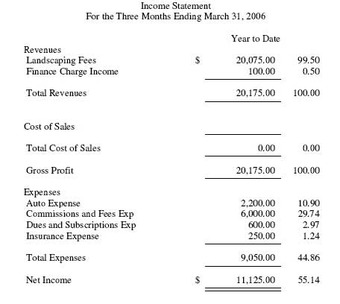

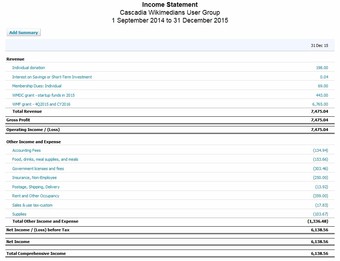

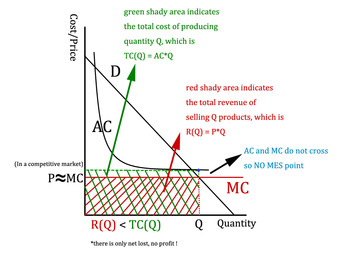

Funds for business operations typically originate from company sales and earning revenue. However, a business can also generate cash funds from other sources as well, such as the sale of non-current assets and through the sale of company stock. The cash flow statement, which shows cash inflows and outflows for a specific reporting period and distinguishes between three types of activities that generate or use cash: operating, investing, and financing.

Operating activities include the production, sales, and delivery of the company’s product, as well as collecting payment from its customers. This could include purchasing raw materials, building inventory, advertising, and shipping the product. Operating activities that generate cash flows are:

Cash inflows from investing activities involve cash flows associated with non-current assets:

Financing activities include the inflow of cash from investors, such as banks and shareholders. Other activities which impact long-term liabilities and equity of the company are also listed under financing activities, such as:

Business operations can require the use of credit and financing to meet operating needs. Credit, in commerce and finance, is a term used to denote transactions involving the transfer of money or other property on promise of repayment, usually at a fixed future date and at a specific interest rate . The transferor thereby becomes a creditor, and the transferee (the recipient of the funds or property) becomes a debtor. Credit is sometimes not granted to a person or business with financial instability or difficulty. Companies frequently offer credit to their customers as part of the terms of a purchase agreement. Organizations that offer credit to their customers frequently employ a credit manager .

A line of credit is any credit source extended to a business or individual by a bank or other financial institution. A line of credit may take several forms, such as overdraft protection, demand loan, special purpose, export packing credit, term loan, discounting, purchase of commercial bills, traditional revolving credit card account, etc. It is effectively a source of funds that can readily be used at the borrower’s discretion. Interest is paid only on money actually withdrawn. Lines of credit can be secured by collateral or may be unsecured.

A revolving credit line provides a borrower with a maximum aggregate amount of capital, available over a specified period of time. However, unlike a term loan, revolving debt allows the borrower to draw down, repa,y and re-draw credit amounts advanced to her by the available capital during the term of the debt. Each credit line is borrowed for a set period of time, usually one, three, or six months, after which time it is technically repayable. Repayment of revolving credit is achieved either by scheduled payments on the total amount of the debt over time, or by all outstanding loans being repaid on the date of termination.

In a loan, the borrower initially receives or borrows an amount of money, called the “principal,” from the lender and is obligated to pay back or repay an equal amount of money to the lender at a later time. Typically, the money is paid back in regular installments, or partial repayments; in an annuity, each installment is the same amount. The loan is generally provided at a cost, referred to as interest on the debt, which provides an incentive for the lender to engage in the loan.

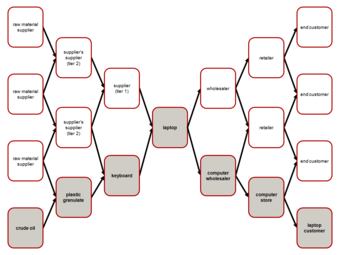

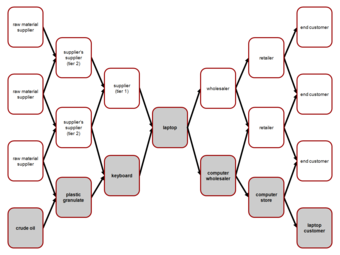

Inventory management is primarily about specifying the quantity and placement of stocked goods. Inventory management is required at different locations within a facility or within multiple locations of a supply network to maintain the regular and planned course of production and to manage the risk of running out of materials or goods for sale. The scope of inventory management also involves stock replenishment lead time, carrying costs of inventory, asset management, inventory forecasting, inventory valuation, inventory visibility, future inventory price forecasting, physical inventory, available physical space for inventory, quality management, returns and defective goods, and demand forecasting .

Purchasing refers to a business or organization acquiring goods or services to accomplish the goals of its enterprise. Companies generally use operating funds to finance their purchasing program. Most organizations use a three-way check as the foundation of their purchasing programs. This involves three departments in the organization completing separate parts of the acquisition process. These departments can be purchasing, receiving, and accounts payable; or engineering, purchasing, and accounts payable; or a plant manager, purchasing, and accounts payable. Combinations can vary significantly, but a purchasing department and accounts payable are usually two of the three departments involved.

Historically, the purchasing department issued purchase orders for supplies, services, equipment, and raw materials. Then, in an effort to decrease the administrative costs associated with the repetitive ordering of basic consumable items, “blanket” or “master” agreements were put into place. These types of agreements typically have a longer duration and increased scope to maximize the quantities of scale concept. When additional supplies were required, a simple release would be issued to the supplier to provide the goods or services.

From time to time, an organization will “shop” for suppliers through the process of bidding. When selecting bidders, an organization identifies potential suppliers for specified supplies, services, or equipment. These suppliers’ credentials and history are analyzed, together with the products or services they offer. The bidder selection process varies from organization to organization, but can include running credit reports, interviewing management, testing products, and touring facilities. Organizational goals will dictate the criteria for the selection process of bidders. It is also possible that the product or service being procured is so specialized that the number of bidders are limited and the criteria must be very wide to permit competition.

Negotiating is a key skill in purchasing. One of the goals of purchasing inventory is to acquire goods at the most advantageous terms for the buying entity (the “Buyer”). Purchasing agents typically attempt to decrease costs while meeting the Buyer’s other requirements, such as an on-time delivery and compliance to the commercial terms and conditions (including the warranty, the transfer of risk, assignment, auditing rights, confidentiality, remedies, etc.).

19.4: Short-Term Financing

19.4.1: Commercial Paper

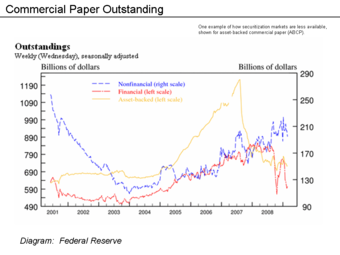

Commercial paper is a money-market security issued (sold) by large corporations to get money to meet short term debt obligations.

Learning Objective

Analyze the commercial paper market

Key Points

- There are two methods of issuing paper. The issuer can market the securities directly to a buy and hold investor such as most money market funds. Alternatively, it can sell the paper to a dealer, who then sells the paper in the market.

- Commercial paper is a lower cost alternative to a line of credit with a bank. Once a business becomes established, and builds a high credit rating, it is often cheaper to draw on a commercial paper than on a bank line of credit.

- Asset-Backed Commercial Paper (ABCP) is a form of commercial paper that is collateralized by other financial assets.

Key Term

- money market

-

A market for trading short-term debt instruments, such as treasury bills, commercial paper, bankers’ acceptances, and certificates of deposit.

Commercial Paper

In the global money market, commercial paper is an unsecured promissory note with a fixed maturity of one to 364 days. Commercial paper is a money-market security issued (sold) by large corporations to get money to meet short term debt obligations (for example, payroll), and is only backed by an issuing bank or a corporation’s promise to pay the face amount on the maturity date specified on the note. Since it is not backed by collateral, only firms with excellent credit ratings from a recognized rating agency will be able to sell their commercial paper at a reasonable price. Commercial paper is usually sold at a discount from face value, and carries higher interest repayment rates than bonds. Typically, the longer the maturity on a note, the higher the interest rate the issuing institution must pay. Interest rates fluctuate with market conditions, but are typically lower than banks’ rates.

There are two methods of issuing paper. The issuer can market the securities directly to a buy and hold investor such as most money market funds. Alternatively, it can sell the paper to a dealer, who then sells the paper in the market . The dealer market for commercial paper involves large securities firms and subsidiaries of bank holding companies. Most of these firms are also dealers in US Treasury securities. Direct issuers of commercial paper are usually financial companies that have frequent and sizable borrowing needs, and find it more economical to sell paper without the use of an intermediary. In the United States, direct issuers save a dealer fee of approximately five basis points, or 0.05% annualized, which translates to $50,000 on every $100 million outstanding. This saving compensates for the cost of maintaining a permanent sales staff to market the paper. Dealer fees tend to be lower outside the United States .

Commercial paper is a lower cost alternative to a line of credit with a bank. Once a business becomes established and builds a high credit rating, it is often cheaper to draw on a commercial paper than on a bank line of credit. Nevertheless, many companies still maintain bank lines of credit as a backup. Banks often charge fees for the amount of the line of the credit that does not have a balance.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages of commercial paper include lower borrowing costs; term flexibility; and more liquidity options for creditors due to its trade-ability.

Disadvantages of commercial paper include its limited eligibility; reduced credit limits with banks; and reduced reliability due to its strict oversight.

Asset-Backed Commercial Paper (ABCP)

Asset-Backed Commercial Paper (ABCP) is a form of commercial paper that is collateralized by other financial assets. ABCP is typically a short-term instrument that matures between one and 180 days from issuance and is typically issued by a bank or other financial institution. The firm wishing to finance its assets through the issuance of ABCP sells the assets to a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) or Structured Investment Vehicle (SIV), created by a financial services company. The SPV/SIV issues the ABCP to raise funds to purchase the assets. This creates a legal separation between the entity issuing and the institution financing its assets.

19.4.2: Factoring Accounts Receivable

Factoring makes it possible for a business to readily convert a substantial portion of its accounts receivable into cash.

Learning Objective

Explain the business of factoring and assess the risks of the involved parties

Key Points

- Debt factoring is also used as a financial instrument to provide better cash flow control especially if a company currently has a lot of accounts receivables with different credit terms to manage.

- The three parties directly involved in factoring are: the one who sells the receivable, the debtor (the account debtor, or customer of the seller), and the factor.

- There are two principal methods of factoring: recourse and non-recourse. Under recourse factoring, the client is not protected against the risk of bad debts. Under non-recourse factoring, the factor assumes the entire credit risk.

Key Term

- factoring

-

A financial transaction whereby a business sells its accounts receivable to a third party (called a factor) at a discount.

Factoring

Factoring is a financial transaction whereby a business sells its accounts receivable to a third party (called a “factor”) at a discount. Factoring makes it possible for a business to convert a readily substantial portion of its accounts receivable into cash. This provides the funds needed to pay suppliers and improves cash flow by accelerating the receipt of funds.

Companies factor accounts when the available cash balance held by the firm is insufficient to meet current obligations and accommodate its other cash needs, such as new orders or contracts. In other industries, however, such as textiles or apparel, for example, financially sound companies factor their accounts simply because this is the historic method of finance. The use of factoring to obtain the cash needed to accommodate a firm’s immediate cash needs will allow the firm to maintain a smaller ongoing cash balance. By reducing the size of its cash balances, more money is made available for investment in the firm’s growth. Debt factoring is also used as a financial instrument to provide better cash flow control, especially if a company currently has a lot of accounts receivables with different credit terms to manage. A company sells its invoices at a discount to their face value when it calculates that it will be better off using the proceeds to bolster its own growth than it would be by effectively functioning as its “customer’s bank. “

Types of Factoring

There are two principal methods of factoring: recourse and non-recourse. Under recourse factoring, the client is not protected against the risk of bad debts. On the other hand, the factor assumes the entire credit risk under non-recourse factoring (i.e., the full amount of invoice is paid to the client in the event of the debt becoming bad). Other variations include partial non-recourse, where the factor’s assumption of credit risk is limited by time, and partial recourse, where the factor and its client (the seller of the accounts) share credit risk. Factors never assume “quality” risk, and even a non-recourse factor can charge back a purchased account which does not collect for reasons other than credit risk assumed by the factor, (e.g., the account debtor disputes the quality or quantity of the goods or services delivered by the factor’s client).

In “advance” factoring, the factor provides financing to the seller of the accounts in the form of a cash “advance,” often 70-85% of the purchase price of the accounts, with the balance of the purchase price being paid, net of the factor’s discount fee (commission) and other charges, upon collection. In “maturity” factoring, the factor makes no advance on the purchased accounts; rather, the purchase price is paid on or about the average maturity date of the accounts being purchased in the batch.

There are three principal parts to “advance” factoring transaction:

- The advance, a percentage of the invoice’s face value that is paid to the seller at the time of sale.

- The reserve, the remainder of the purchase price held until the payment by the account debtor is made.

- The discount fee, the cost associated with the transaction which is deducted from the reserve, along with other expenses, upon collection, before the reserve is disbursed to the factor’s client.

Parties Involved in the Factoring Process

The three parties directly involved are the one who sells the receivable, the debtor (the account debtor, or customer of the seller), and the factor. The receivable is essentially an asset associated with the debtor’s liability to pay money owed to the seller (usually for work performed or goods sold). The seller then sells one or more of its invoices (the receivables) at a discount to the third party, the specialized financial organization (aka the factor), often, in advance factoring, to obtain cash. The sale of the receivables essentially transfers ownership of the receivables to the factor, indicating the factor obtains all of the rights associated with the receivables. Accordingly, the factor obtains the right to receive the payments made by the debtor for the invoice amount and, in non-recourse factoring, must bear the loss if the account debtor does not pay the invoice amount due solely to his or its financial inability to pay.

Risks in Factoring

The most important risks of a factor are:

- Counter party credit risk: risk covered debtors can be re-insured, which limit the risks of a factor. Trade receivables are a fairly low risk asset due to their short duration.

- External fraud by clients: fake invoicing, mis-directed payments, pre-invoicing, unassigned credit notes, etc. A fraud insurance policy and subjecting the client to audit could limit the risks.

- Legal, compliance, and tax risks: a large number and variety of applicable laws and regulations depending on the country.

- Operational: operational risks such as contractual disputes.

19.4.3: Credit Cards

Credit cards allow users to pay for goods and services based on the promise to pay for them later and the immediate provision of cash by the card provider.

Learning Objective

Evaluate the costs and benefits of a credit card

Key Points

- The issuer of the card creates a revolving account and grants a line of credit to the consumer (or the user) from which the user can borrow money for payment to a merchant or as a cash advance to the user.

- The main benefit to each customer is convenience. Credit cards allow small short-term loans to be quickly made to a customer who need not calculate a balance remaining before every transaction, provided the total charges do not exceed the maximum credit line for the card.

- Costs to users include high interest rates and complex fee structures.

Key Term

- credit card

-

A plastic card with a magnetic strip or an embedded microchip connected to a credit account and used to buy goods or services. It’s like a debit card, but money comes not from your personal bank account, but the bank lends money for the purchase based on the credit limit. Credit limit is determined by the income and credit history. Bank charge APR (annual percentage rate) for using of money.

Example

- For example, if a user has a $1,000 transaction and repaid it in full within this grace period, there would be no interest charged. If, however, even $1 of the total amount remained unpaid, interest would be charged on the $1,000 from the date of purchase until the payment is received.

Credit Cards

A credit card is a payment card issued to users as a system of payment. It allows the cardholder to pay for goods and services based on the promise to pay for them later and the immediate provision of cash by the card provider. The issuer of the card creates a revolving account and grants a line of credit to the consumer (or the user) from which the user can borrow money for payment to a merchant or as a cash advance to the user. Credit cards allow the consumers a continuing balance of debt, subject to interest being charged. A credit card also differs from a cash card, which can be used like currency by the owner of the card .

Credit cards are issued by an issuer like a bank or credit union after an account has been approved by the credit provider, after which cardholders can use it to make purchases at merchants accepting that card.

Benefits to Users

The main benefit to each customer is convenience. Compared to debit cards and checks, a credit card allows small short-term loans to be quickly made to a customer who need not calculate a balance remaining before every transaction, provided the total charges do not exceed the maximum credit line for the card.

Many credit cards offer rewards and benefits packages like enhanced product warranties at no cost, free loss/damage coverage on new purchases and various insurance protections. Credit cards can also offer reward points which may be redeemed for cash, products or airline tickets.

Costs to Users

High interest rates: Low introductory credit card rates are limited to a fixed term, usually between six and 12 months, after which a higher rate is charged. As all credit cards charge fees and interest, some customers become so indebted to their credit card provider that they are driven to bankruptcy. Some credit cards often levy a rate of 20 to 30 percent after a payment is missed. In other cases a fixed charge is levied without change to the interest rate. In some cases universal default may apply – the high default rate is applied to a card in good standing by missing a payment on an unrelated account from the same provider. This can lead to a snowball effect in which the consumer is drowned by unexpectedly high interest rates.

Complex fee structures in the credit card industry limit customers’ ability to comparison shop, help ensure that the industry is not price-competitive and help maximize industry profits.

Benefits to Merchants

For merchants, a credit card transaction is often more secure than other forms of payment, because the issuing bank commits to pay the merchant the moment the transaction is authorized regardless of whether the consumer defaults on the credit card payment. In most cases, cards are even more secure than cash, because they discourage theft by the merchant’s employees and reduce the amount of cash on the premises. Finally, credit cards reduce the back office expense of processing checks/cash and transporting them to the bank.

Costs to Merchants

Merchants are charged several fees for accepting credit cards. The merchant is usually charged a commission of around one to three percent of the value of each transaction paid for by credit card. The merchant may also pay a variable charge, called an interchange rate, for each transaction. In some instances of very low-value transactions, use of credit cards will significantly reduce the profit margin or cause the merchant to lose money on the transaction. Merchants with very low average transaction prices or very high average transaction prices are more averse to accepting credit cards. Merchants may charge users a “credit card supplement,” either a fixed amount or a percentage, for payment by credit card. This practice is prohibited by the credit card contracts in the United States, although the contracts allow the merchants to give discounts for cash payment.

Merchants are also required to lease processing terminals, meaning merchants with low sales volumes may have to commit to long lease terms. For some terminals, merchants may need to subscribe to a separate telephone line. Merchants must also satisfy data security compliance standards which are highly technical and complicated. In many cases, there is a delay of several days before funds are deposited into a merchant’s bank account. As credit card fee structures are very complicated, smaller merchants are at a disadvantage to analyze and predict fees. Finally, merchants assume the risk of chargebacks by consumers.

19.4.4: Commercial Banks

A commercial bank lends money, accepts time deposits, and provides transactional, savings, and money market accounts.

Learning Objective

Sketch out the role of commercial banks in money lending

Key Points

- Commercial banks may provide a secured loan, which are monetary loans that have borrower collateral pledged against their repayment.

- Commercial banks may also provide unsecured loans, which are monetary loans that are not secured against the borrower’s assets (i.e., no collateral is involved).

- Accessing funds through a commercial bank is a very common way of accessing funds when in need, particularly in the case of small or entrepreneurial businesses.

Key Term

- collateral

-

A security or guarantee (usually an asset) pledged for the repayment of a loan if one cannot procure enough funds to repay. (Originally supplied as “accompanying” security. )

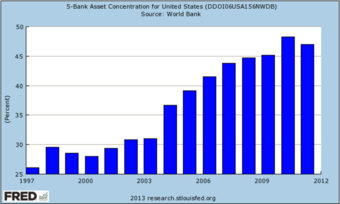

A commercial or business bank , is a type of financial institution and intermediary that lends money, accepts time deposits, and provides transactional, savings, and money market accounts.

Commercial banks engage in the following activities: the processing of payments; accepting money on term deposit; lending money by overdraft, installment loan, or other means; providing documentary and standby letters of credit guarantees, performance bonds, securities underwriting commitments and other forms of off- balance sheet exposures; and the safekeeping of documents and other items in safe deposit boxes.

Commercial banks provide a number of loans. A secured loan is when a borrower pledges some asset (e.g., a car or property) as collateral for it, which then becomes a secured debt owed to the creditor who gives the loan. The debt is thus secured against the collateral. In the event that the borrower defaults, the creditor takes possession of the asset used as collateral and may sell it to regain some or all of the amount originally lent to the borrower.

Commercial banks may also provide unsecured loans, which are monetary loans that are not secured against the borrower’s assets (i.e., no collateral is involved). Some examples of unsecured loans include credit cards and credit lines.

An overdraft is an example of an unsecured loan. An overdraft occurs when money is withdrawn from a bank account and the available balance goes below zero. In this situation, the account is said to be “overdrawn”. If there is a prior agreement with the account provider for an overdraft, and the amount overdrawn is within the authorized overdraft limit, then interest is normally charged at the agreed rate. If the positive balance exceeds the agreed terms, then additional fees may be charged and higher interest rates may apply.

Accessing funds through a commercial bank is very typical, and a common way of accessing funds when in need, particularly in the case of small or entrepreneurial businesses.

19.4.5: Trade Credit or Accounts Payable

Trade credit is the largest use of capital for a majority of B2B sellers; Accounts Payable is money owed by a firm to its suppliers.

Learning Objective

Explain the process of using and recording accounts payable

Key Points

- There are many forms of trade credit in common use; often industry-specific. They all benefit from their collaboration to make efficient use of capital to accomplish various business objectives.

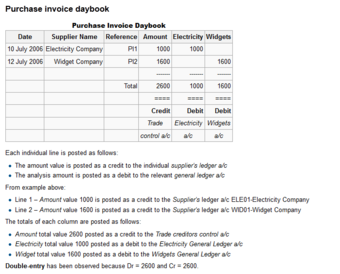

- An accounts payable is recorded in the Account Payable sub-ledger at the time an invoice is vouchered for payment.

- Commonly, a supplier will ship a product, issue an invoice, and collect payment later, which describes a cash conversion cycle, or a period of time during which the supplier has already paid for raw materials but hasn’t been paid in return by the final customer.

Key Term

- supplier

-

One who supplies; a provider.

Trade Credit

Trade credit is the largest use of capital for a majority of business to business (B2B) sellers in the United States and is a critical source of capital for a majority of all businesses. For example, Wal-Mart, the largest retailer in the world, has used trade credit as a larger source of capital than bank borrowings. Trade credit for Wal-Mart is eight times the amount of capital invested by shareholders.

For many borrowers in the developing world, trade credit serves as a valuable source of alternative data for personal and small business loans.

There are many forms of trade credit in common use; often industry-specific. They all benefit from their collaboration to make efficient use of capital to accomplish various business objectives.

Accounts Payable (A/P)

Accounts Payable (A/P and also known as creditors) is money owed by a business to its suppliers. An accounts payable is recorded in the A/P sub-ledger at the time an invoice is vouchered for payment. Payables are often categorized as Trade Payables, payables for the purchase of physical goods that are recorded in Inventory, and Expense Payables, payables for the purchase of goods or services that are expensed. Common examples of Expense Payables are advertising, travel, entertainment, office supplies, and utilities. A/P is a form of credit that suppliers offer to their customers by allowing them to pay for a product or service after it has already been received .

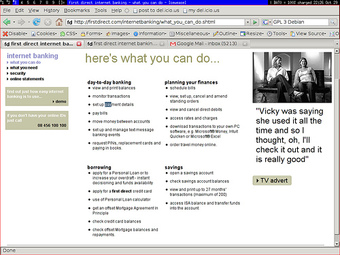

In households, these payables are ordinarily bills such as utility, rent, etc. Households usually track and pay on a monthly basis manually by using checks, credit cards, or online banking. In a business, there is usually a much broader range of suppliers to pay, and accountants or bookkeepers usually use accounting software to track the flow of money into this liability account when they receive invoices and out of it when they make payments. Increasingly, large firms often use specialized automation solutions (commonly called ePayables) to automate the paper and manual elements of processing an organization’s invoices.

Commonly, a supplier will ship a product, issue an invoice, and collect payment later, which describes a cash conversion cycle, a period of time during which the supplier has already paid for raw materials but hasn’t been paid in return by the final customer. When the invoice is received by the purchaser, it is matched to the packing slip and purchase order, and if all is in order, the invoice is paid. This is referred to as the three-way match. The three-way match can slow down the payment process, so the method may be modified. For example, three-way matching may be limited solely to large-value invoices, or the matching is automatically approved if the received quantity is within a certain percentage of the amount authorized in the purchase order.

19.4.6: Family and Friends

Asking friends and families to invest is one way that start-ups are funded.

Learning Objective

Analyze person to person (P2P) lending

Key Points

- Somewhat similar to raising money from family and friends is person-to-person lending. Person-to-person lending is a certain breed of financial transaction which occurs directly between individuals or “peers” without the intermediation of a traditional financial institution.

- Lending money and supplies to friends, family, and community members predates formalized financial institutions, but in its modern form, peer-to-peer lending is a by-product of Internet technologies, especially Web 2.0.

- In a particular model of P2P lending known as “family and friend lending”, the lender lends money to a borrower based on their pre-existing personal, family, or business relationship.

Key Term

- financial institution

-

In financial economics, a financial institution is an institution that provides financial services for its clients or members.

Investments from Family and Friends

Asking friends and families to invest is another common way that start-ups are funded. Often the potential entrepreneur is young, energetic, and has a good idea for a start-up, but does not have much in the way of personal savings. Friends and family may be older and have some money set aside. While your parents, or other family members should not risk all of their retirement savings on your start-up, they may be willing to risk a small percentage of it to help you out .

Sometimes friends your own age are willing to work for little or no wages until your cash flow turns positive. The term “sweat equity” is often used for this type of contribution as the owner will often reward such loyalty with a small percentage ownership of the organization in lieu of cash. A variation on this is barter or trade. This is a method by which you could provide a needed service such as consulting or management advice in return for the resources needed for your start up. This needs to be accounted for in your accounting records also.

Person-to-Person Lending

Somewhat similar to raising money from family and friends is person-to-person lending. Person-to-person lending (also known as peer-to-peer lending, peer-to-peer investing, and social lending; abbreviated frequently as P2P lending) is a certain breed of financial transaction (primarily lending and borrowing, though other more complicated transactions can be facilitated) which occurs directly between individuals or “peers” without the intermediation of a traditional financial institution. However, person-to-person lending is for the most part a for-profit activity, which distinguishes it from person-to-person charities, person-to-person philanthropy, and crowdfunding.

Lending money and supplies to friends, family, and community members predates formalized financial institutions, but in its modern form, peer-to-peer lending is a by-product of Internet technologies, especially Web 2.0. The development of the market niche was further boosted by the global economic crisis in 2007 to 2010 when person-to-person lending platforms promised to provide credit at the time when banks and other traditional financial institutions were having fiscal difficulties.

Many peer-to-peer lending companies leverage existing communities and pre-existing interpersonal relationships with the idea that borrowers are less likely to default to the members of their own communities. The risk associated with lending is minimized either through mutual (community) support of the borrower or, as occurs in some instances, through forms of social pressure. The peer-to-peer lending firms either act as middlemen between friends and family to assist with calculating repayment terms, or connect anonymous borrowers and lenders based on similarities in their geographic location, educational and professional background, and connectedness within a given social network.

In a particular model of P2P lending known as “family and friend lending”, the lender lends money to a borrower based on their pre-existing personal, family, or business relationship. The model forgoes an auction-like process and concentrates on formalizing and servicing a personal loan. Lenders can charge below market rates to assist the borrower and mitigate risk. Loans can be made to pay for homes, personal needs, school, travel, or any other needs.

Advantages and Criticisms

One of the main advantages of person-to-person lending for borrowers has been better rates than traditional bank rates can offer (often below 10%). The advantages for lenders are higher returns that would be unobtainable from a savings account or other investments.

As person-to-person lending companies and their customer base continue to grow, marketing expenses and administrative costs associated with customer service and arbitration, maintaining product information, and developing quality websites to service customers and stand out among competitors will rise. In addition, compliance to legal regulations becomes more complicated. This causes many of the original benefits from disintermediation to fade away and turns person-to-person companies into new intermediaries, much like the banks that they originally differentiated from. This process of reintroducing intermediaries is known as reintermediation.

Person-to-person lending also attracts borrowers who, because of their past credit status or the lack of thereof, are unqualified for traditional bank loans. The unfortunate situation of these borrowers is well-known for the people issuing the loans and results in very high interest rates that verge on predatory lending and loan sharking.

19.4.7: Secured vs. Unsecured Funding

A secured loan is a loan in which the borrower pledges an asset (e.g. a car or property) as collateral, while an unsecured loan is not secured by an asset.

Learning Objective

Differentiate between a secured loan vs. an unsecured loan

Key Points

- A loan constitutes temporarily lending money in exchange for future repayment with specific stipulations such as interest, finance charges, and fees.

- Secured loans are secured by assets such as real estate, an automobile, boat, or jewelry. The secured asset is known as collateral. In the event the borrower does not pay the loan as agreed, he/she may forfeit the asset used as collateral to the lender.

- Unsecured loans are monetary loans that are not secured against collateral. Interest rates for unsecured loans are often higher than for secured loans because the risk to the lender is greater.

Key Term

- Assets

-

An asset is something of economic value. Examples of assets include money, real estate, and automobiles.

Examples

- A mortgage loan is a secured loan in which the collateral is real estate. If the borrower does not pay back the mortgage within the agreed upon terms, the lender may seize the property. Seizure of real estate for non-payment is also known as foreclosure. A foreclosure is a legal process in which mortgaged property is sold to pay the debt of the defaulting borrower.

- A car loan is a secured loan in which the collateral is an automobile, If the borrower does not pay back the car loan within the agreed upon terns, the lender may seize the automobile. Seizure of an automobile for non-payment is also known as repossession. Repossession is a legal process in which property, such as a car, is taken back by the creditor.

Loans

Debt refers to an obligation. A loan is a monetary form of debt. A loan constitutes temporarily lending money in exchange for future repayment with specific stipulations such as interest, finance charges, and/or fees. A loan is considered a contract between the lender and the borrower. Loans may either be secured or unsecured.

Secured Loans

A secured loan is a loan in which the borrower pledges some asset (e.g., a car or property) as collateral. A mortgage loan is a very common type of debt instrument, used by many individuals to purchase housing. In this arrangement, the money is used to purchase the property. The financial institution, however, is given security — a lien on the title to the house — until the mortgage is paid off in full. If the borrower defaults on the loan, the bank has the legal right to repossess the house and sell it, to recover sums owed to it.

If the sale of the collateral does not raise enough money to pay off the debt, the creditor can often obtain a deficiency judgment against the borrower for the remaining amount. Generally speaking, secured debt may attract lower interest rates than unsecured debt due to the added security for the lender. However, credit history, ability to repay, and expected returns for the lender are also factors affecting rates.

There are two purposes for a loan secured by debt. By extending the loan through secured debt, the creditor is relieved of most of the financial risks involved because it allows the creditor to take the property in the event that the debt is not properly repaid. For the debtor, a secured debt may receive more favorable terms than that available for unsecured debt, or to be extended credit under circumstances when credit under terms of unsecured debt would not be extended at all. The creditor may offer a loan with attractive interest rates and repayment periods for the secured debt.

Unsecured Loans

Unsecured loans are monetary loans that are not secured against the borrower’s assets. The interest rates applicable to these different forms may vary depending on the lender and the borrower. These may or may not be regulated by law.

Interest rates on unsecured loans are nearly always higher than for secured loans, because an unsecured lender’s options for recourse against the borrower in the event of default are severely limited. An unsecured lender must sue the borrower, obtain a money judgment for breach of contract, and then pursue execution of the judgment against the borrower’s unencumbered assets (that is, the ones not already pledged to secured lenders). In insolvency proceedings, secured lenders traditionally have priority over unsecured lenders when a court divides up the borrower’s assets. Thus, a higher interest rate reflects the additional risk that in the event of insolvency, the debt may be difficult or impossible to collect.

Unsecured loans are often used by borrowers for small purchases such as computers, home improvements, vacations, or unexpected expenses. An unsecured loan means the lender relies on the borrower’s promise to pay it back. Due to the increased risk involved, interest rates for unsecured loans tend to be higher. Typically, the balance of the loan is distributed evenly across a fixed number of payments; penalties may be assessed if the loan is paid off early. Unsecured loans are often more expensive and less flexible than secured loans, but suitable if the lender wants a short-term loan (one to five years).

In the event of the bankruptcy of the borrower, the unsecured creditors will have a general claim on the assets of the borrower after the specific pledged assets have been assigned to the secured creditors, although the unsecured creditors will usually realize a smaller proportion of their claims than the secured creditors.

In some legal systems, unsecured creditors who are also indebted to the insolvent debtor are able (and in some jurisdictions, required) to set-off the debts, which actually puts the unsecured creditor with a matured liability to the debtor in a pre-preferential position.

19.4.8: Short-Term Loans

Short-term loans offer individuals and businesses borrowing options to meet financial obligations.

Learning Objective

Classify different types of short term loans

Key Points

- Longer term funding is supplied by bonds and equity.

- Convenience is main benefit of a credit card to a business or entrepreneur .

- Venture capitalists use bridge loans to “bridge” cash flow gaps between successive major private equity financing terms.

Key Terms

- London Interbank Offered Rate

-

the average interest rate estimated by leading financial instiutions in London that they would be charged if borrowing from others

- collateral

-

A security or guarantee (usually an asset) pledged for the repayment of a loan if one cannot procure enough funds to repay. (Originally supplied as “accompanying” security. )

- benchmark

-

A standard by which something is evaluated or measured.

- venture capital

-

money invested in an innovative enterprise in which both the potential for profit and the risk of loss are considerable.

Example

- In December 2010, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR) and partners marketed a bridge loan for its upcoming acquisition of Del Monte Foods. As is common in such cases, KKR planned for the newly private company to borrow money by issuing corporate bonds. To ensure the money would be available, KKR sought $1.6 billion in bridge loan guarantees, for which it promised to pay 8.75 percent interest for 60 days and 11.75 percent thereafter. At KKR’s option, these loans could then be replaced with eight-year corporate bonds (in effect, a put option) paying 11.75 percent. In return for the loans and guarantees, KKR was offering roughly 2 percent in fees.

Short Term Loans

Short term loans are borrowed funds used to meet obligations within a few days up to a year. The borrower receives cash from the lender more quickly than with medium- and long-term loans, and must repay it in a shorter time frame.

Examples of short-term loans include:

Overdraft

Overdraft protection is a financial service offered by banking institutions in the United States. An overdraft occurs when money is withdrawn from a bank account and the available balance goes below zero. In this situation, the account is said to be “overdrawn. ” If there is a prior agreement with the account provider for an overdraft, and the amount overdrawn is within the authorized overdraft limit, then interest is normally charged at the agreed rate.

Credit Card

A credit card is a payment card issued to users as a method of payment. It allows the cardholder to pay for goods and services based on the holder’s promise to pay for them. The issuer of the card creates a revolving account and grants a line of credit to the consumer (or the user) from which the user can borrow money for payment to a merchant or as a cash advance to the user. For smaller businesses, financing via credit card is an easy and viable option.

The main benefit to a business or entrepreneur is convenience. Compared to debit cards and checks, a credit card allows small short-term loans to be quickly made to a customer. The customer then need not calculate a balance remaining before every transaction, provided the total charges do not exceed the maximum credit line for the card.

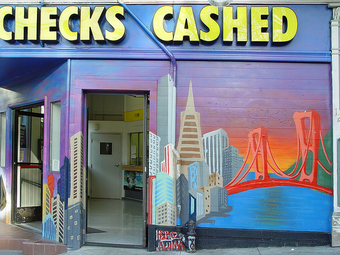

Payday Loans

A payday loan (also called a payday advance) is a small, short-term unsecured loan. These loans are also sometimes referred to as “cash advances,” though that term can also refer to cash provided against a credit card or other prearranged line of credit. The basic loan process involves a lender providing a short-term unsecured loan to be repaid at the borrower’s next pay day. Typically, some verification of employment or income is involved (via pay stubs and bank statements), but some lenders may omit this.

Money Market

The money market developed because parties had surplus funds, while others needed cash. The core of the money market consists of inter bank lending (banks borrowing and lending to each other using commercial paper), repurchase agreements, and similar short-term financial instruments. Because money market securities are typically denominated in high values, it is not common for individual investors to wholly own shares of money market securities; instead, investments are carried out by corporations or money market mutual funds. These instruments are often benchmarked to the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) for the appropriate term and currency.

Refund Anticipation Loan (RAL)

A refund anticipation loan (RAL) is a short-term consumer loan secured by a taxpayer’s expected tax refund designed to offer customers quicker access to funds than waiting for their tax refund. In the United States, taxpayers can apply for a refund anticipation loan through a paid professional tax preparation service.

Bridge Loans

A bridge loan is a type of short-term loan, typically taken out for a period of two weeks to three years pending the arrangement of larger or longer-term financing. It is interim financing for an individual or business until permanent or next-stage financing can be obtained. Money from the new financing is generally used to “take out” (i.e. to pay back) the bridge loan, as well as other capitalization needs.

Bridge loans are typically more expensive than conventional financing to compensate for the additional risk of the loan. Bridge loans typically have a higher interest rate, points and other costs that are amortized over a shorter period, as well as various fees and other “sweeteners” like equity participation by the lender. The lender also may require cross-collateralization and a lower loan-to-value ratio. On the other hand, they are typically arranged quickly with little documentation.

Bridge loans are used in venture capital and other corporate finance for several purposes:

- To inject small amounts of cash to carry a company so that it does not run out of cash between successive major private equity financing.

- To carry distressed companies while searching for an acquirer or larger investor (in which case the lender often obtains a substantial equity position in connection with the loan).

- As a final debt financing to carry the company through the immediate period before an initial public offering or acquisition.

19.5: Long-Term Financing

19.5.1: Financial Leverage

Financial leverage is a technique used to multiply gains and losses by obtaining funds through debt instead of equity.

Learning Objective

Explain the implications of leverage on a company’s risk

Key Points

- In terms of investments, there exists accounting leverage, notional leverage, and economic leverage.

- In corporate finance, financial leverage involves the use of debt instruments over equity instruments to acquire additional assets, therefore keeping stakeholders at a minium and per share profits at a maximum.

- It is possible to over-leverage, which is incurring a huge debt by borrowing funds at a lower rate of interest and using the excess funds in high risk investments in order to maximize returns.

- There is an important implicit assumption in evaluating the risk of leverage, which is that the underlying levered asset is the same as the unlevered one.

Key Terms

- notional

-

Speculative, theoretical, not the result of research.

- equity

-

Ownership interest in a company as determined by subtracting liabilities from assets.

- derivative

-

A financial instrument whose value depends on the valuation of an underlying asset; such as a warrant or an option.

Financial Leverage

Financial leverage is a general term for any technique to multiply gains and losses. Common ways to attain leverage are borrowing money or buying derivatives. Examples include:

- A public corporation may leverage its equity (stocks outstanding) by borrowing money. The more it borrows, the less equity capital it needs, so any profits or losses are shared among a smaller base and are proportionately larger as a result.

- A business entity can leverage its revenue by buying fixed assets. This will increase the proportion of fixed, as opposed to variable, costs, meaning that a change in revenue will result in a larger change in operating income .

Measuring Leverage

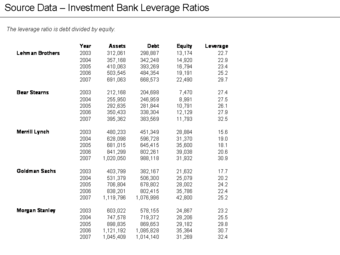

The term “leverage” is used differently in investments and corporate finance, and has multiple definitions in each field. In terms of investments, there exists accounting leverage, notional leverage, and economic leverage. Accounting leverage is total assets divided by the total assets minus total liabilities (or total equity). Notional leverage is total notional amount of assets plus total notional amount of liabilities divided by equity. Economic leverage is the volatility of an asset divided by volatility of an unlevered investment in the same assets.

Leverage In Corporate Finance

The concept of financial leverage is much more utilized and understood in the realm of corporate finance. Financial leverage tries to estimate the percentage change in net income for a one percent change in operating income. It involves the use of debt instruments over equity instruments to acquire additional assets, therefore keeping stakeholders at a minium and per share profits at a maximum. It is possible to over-leverage, which is incurring a huge debt by borrowing funds at a lower rate of interest and using the excess funds in high risk investments in order to maximize returns.

Leverage and Risk

The most obvious risk of leverage is that it multiplies losses. A corporation that borrows too much money might face bankruptcy during a business downturn, while a less-levered corporation might survive. There is an important implicit assumption, though, in evaluating the risk of leverage, which is that the underlying levered asset is the same as the unlevered one. If a company borrows money to modernize, or add to its product line, or expand internationally, the additional diversification might more than offset the additional risk from leverage.

From an investor’s point of view, if an individual uses a fraction of his or her portfolio to purchase derivatives and puts the rest in a money market fund, he or she might have the same volatility and expected return as an investor in an unlevered equity index fund, plus a limited downside. In short, while adding leverage to a given asset always adds risk, it is not the case that a levered company or investment is always riskier than an unlevered one. For example, many highly-levered hedge funds have less return volatility than unlevered bond funds, and public utilities with lots of debt are usually less risky stocks than unlevered technology companies.

There is a popular prejudice against leverage rooted in the observation that people who borrow a lot of money often end up in unfavorable situations. However, individuals who undertake such positions are not typically undertaking leverage. Instead, they are borrowing money for personal consumption. In finance, the general practice is to borrow money to buy an asset with a higher return than the cost of borrowing.

There also exists the risk of involuntary leverage. This is a situation in which a company or individual enters into financial distress and is forced to enter into a higher leveraged position. This multiplies losses as things continue to go downhill. This can lead to rapid ruin, even if the underlying asset value decline is mild or temporary.

19.5.2: Debt Finance

Debt is a way for firms to access capital for operations or investment with various terms and agreements for future repayment .

Learning Objective

Outline the characteristics of the different types of debt financing available

Key Points

- A debt obligation is considered secured, if creditors have recourse to the assets of the company on a proprietary basis or otherwise ahead of general claims against the company.

- Private debt comprises bank-loan type obligations, whether senior or mezzanine. Public debt is a general definition covering all financial instruments that are freely tradeable on a public exchange or over the counter, with few if any restrictions.

- A syndicated loan is a loan that is granted to companies that wish to borrow more money than any single lender is prepared to risk in a single loan, usually many millions of dollars.

Key Terms

- coupon

-

Any interest payment made or due on a bond, debenture or similar (no longer by a physical coupon).

- unsecured debt

-

Unsecured debt comprises financial obligations, where creditors do not have recourse to the assets of the borrower to satisfy their claims.

- Private debt

-

Private debt comprises bank-loan type obligations, whether senior or mezzanine.

Debt Finance

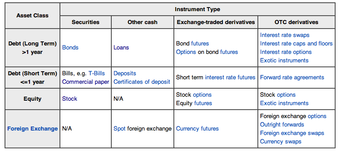

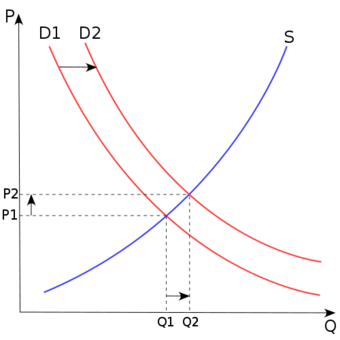

A company uses various kinds of debt to finance its operations . The various types of debt can generally be categorized into:

- Secured and unsecured debt.

- Private and public debt.

- Syndicated and bilateral debt.

- Other types of debt that display one or more of the characteristics noted above.

A debt obligation is considered secured, if creditors have recourse to the assets of the company on a proprietary basis or otherwise ahead of general claims against the company. Unsecured debt comprises financial obligations, where creditors do not have recourse to the assets of the borrower to satisfy their claims.

Private debt comprises bank loan sorts of obligations, whether senior or mezzanine. Public debt is a general definition covering all financial instruments that are freely trade-able on a public exchange or over the counter, with few if any restrictions. A basic loan or “term loan” is the simplest form of debt. It consists of an agreement to lend a fixed amount of money, called the principal sum, for a fixed period of time, with the amount to be repaid by a certain date. In commercial loans interest, calculated as a percentage of the principal sum per year, will also have to be paid by that date, or may be paid periodically in the interval, such as annually or monthly. Such loans are also colloquially called “bullet loans”, particularly if there is only a single payment at the end – the “bullet” – without a “stream” of interest payments during the “life” of the loan.

A syndicated loan is a loan that is granted to companies that wish to borrow more money than any single lender is prepared to risk in a single loan, usually many millions of dollars. In such a case, a syndicate of banks can each agree to put forward a portion of the principal sum. Loan syndication is a risk management tool that allows the lead banks underwriting the debt to reduce their risk and free up lending capacity. A bond is a debt security issued by certain institutions such as companies and governments. A bond entitles the holder to repayment of the principal sum, plus interest. Bonds are issued to investors in a marketplace when an institution wishes to borrow money. Bonds have a fixed lifetime, usually a number of years; with long-term bonds, lasting over thirty years, being less common. At the end of the bond’s life, the money should be repaid in full. Interest may be added to the end payment, or can be paid in regular installments (also known as coupons) during the life of the bond. Bonds may be traded in bond markets, and are widely used as relatively safe investments in comparison to equity.

Lending to stable financial entities such as large companies or governments are often termed “risk free” or “low risk” and made at a so-called “risk-free interest rate”. This is because the debt and interest are highly unlikely to be defaulted. A good example of such risk-free interest is a US Treasury security – it yields the minimum return available in economics, but investors have the comfort of the (almost) certain expectation that the US Treasury will not default on its debt. A risk-free rate is also commonly used in setting floating interest rates, which are usually calculated as the risk-free interest rate plus a bonus to the creditor based on the creditworthiness of the debtor (in other words, the risk of him or her defaulting and the creditor losing the debt). In reality, no lending is truly risk free, but borrowers at this rate are considered the least likely to default.

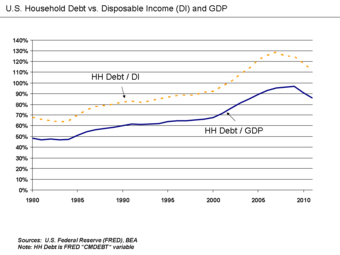

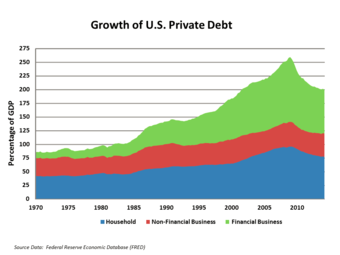

Debt allows people and organizations to do things that they would otherwise not be able, or allowed, to do. Commonly, people in industrialised nations use it to purchase houses, cars and many other things too expensive to buy with cash on hand. Companies also use debt in many ways to leverage the investment made in their assets, “leveraging” the return on their equity. This leverage, the proportion of debt to equity, is considered important in determining the riskiness of an investment; the more debt per equity, the riskier. For both companies and individuals, this increased risk can lead to poor results, as the cost of servicing the debt can grow beyond the ability to pay due to either external events (income loss) or internal difficulties (poor management of resources).

19.5.3: Equity Finance

Companies can use equity financing to raise money and/or increase shareholder liquidity (through an IPO).

Learning Objective

Explain the process of financing a firm through equity

Key Points

- The equity, or capital stock (or stock) of a business entity represents the original capital paid into or invested in the business by its founders.

- Shares represent a fraction of ownership in a business. A business may declare different types or classes of shares, each having distinctive ownership rules, privileges, or share values.

- In finance, the cost of equity is the return (often expressed as a rate of return) a firm theoretically pays to its equity investors, (i.e., shareholders), to compensate for the risk they undertake by investing their capital.

Key Terms

- Preferred Stock

-

Stock with a dividend, usually fixed, that is paid out of profits before any dividend can be paid on common stock and that has priority to common stock in liquidation.

- Common stock

-

Shares of an ownership interest in the equity of a corporation or other entity with limited liability entitled to dividends, with financial rights junior to preferred stock and liabilities.

- par value

-

The amount or value listed on a bill, note, stamp, etc.; the stated value or amount.

Equity

The equity, or capital stock (or stock) of a business entity represents the original capital paid into or invested in the business by its founders. It serves as a security for the creditors of a business since it cannot be withdrawn to the detriment of the creditors. Stock is different from the property and the assets of a business which may fluctuate in quantity and value.

The stock of a business is divided into multiple shares, the total of which must be stated at the time of business formation. Given the total amount of money invested in the business, a share has a certain declared face value, commonly known as the par value of a share. The par value is the minimum amount of money that a business may issue and sell shares for in many jurisdictions, and it is the value represented as capital in the accounting of the business.

Shares represent a fraction of ownership in a business. A business may declare different types or classes of shares, each having distinct ownership rules, privileges, or share values. Ownership of shares is documented by the issuance of a stock certificate. A stock certificate is a legal document that specifies the amount of shares owned by the shareholder, and other specifics of the shares, such as the par value, if any, or the class of the shares.

Stock typically takes the form of either common or preferred. As a unit of ownership, common stock typically carries voting rights that can be exercised in corporate decisions. Preferred stock differs from common stock in that it typically does not carry voting rights but is legally entitled to receive a certain level of dividend payments before any dividends can be issued to other shareholders.

Financing through Equity

The owners of a private company may want additional capital to invest in new projects within the company. They may also simply wish to reduce their holding, freeing up capital for their own private use. They can achieve these goals by selling shares in the company to the general public, through a sale on a stock exchange. This process is called an Initial Public Offering, or IPO.

By selling shares they can sell part or all of the company to many part-owners. The purchase of one share entitles the owner of that share to literally share in the ownership of the company, a fraction of the decision-making power, and potentially a fraction of the profits, which the company may issue as dividends.

Public companies may issue additional shares (thus diluting current equity holders) to raise money to fund operations or capital investments.

Financing a company through the sale of stock in a company is known as equity financing. Alternatively, debt financing (for example issuing bonds) can be done to avoid giving up shares of ownership of the company. Unofficial financing known as trade financing usually provides the major part of a company’s working capital (day-to-day operational needs).

Cost of Equity

In finance, the cost of equity is the return, often expressed as a rate of return, a firm theoretically pays to its equity investors, (i.e., shareholders) to compensate for the risk they undertake by investing their capital. Firms need to acquire capital from others to operate and grow. Individuals and organizations who are willing to provide their funds to others naturally desire to be rewarded. Just as landlords seek rents on their property, capital providers seek returns on their funds, which must be commensurate with the risk undertaken.

Firms obtain capital from two kinds of sources: lenders and equity investors. From the perspective of capital providers, lenders seek to be rewarded with interest and equity investors seek dividends and/or appreciation in the value of their investment (capital gain). From a firm’s perspective, they must pay for the capital it obtains from others, which is called its cost of capital. Such costs are separated into a firm’s cost of debt and cost of equity and attributed to these two kinds of capital sources.

While a firm’s present cost of debt is relatively easy to determine from observation of interest rates in the capital markets, its current cost of equity is unobservable and must be estimated. According to finance theory, as a firm’s risk increases/decreases, its cost of capital increases/decreases. This theory is linked to observation of human behavior and logic: capital providers expect reward for offering their funds to others. Such providers are usually rational and prudent preferring safety over risk. They naturally require an extra reward as an incentive to place their capital in a riskier investment instead of a safer one. If an investment’s risk increases, capital providers demand higher returns or they will place their capital elsewhere.

19.5.4: Long-Term Loans

Three common examples of long term loans are government debt, mortgages, and debentures (bonds).

Learning Objective

Outline the characteristics of three types of long term loans: debt, mortgages and bonds

Key Points

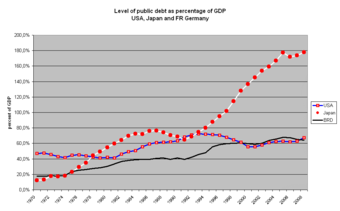

- Government debt (also known as public debt or national debt) is owed by a central government. Government debt is one of several methods of financing government operations.

- A mortgage is a loan secured by real property. It requires a mortgage note affirming the existence of the loan and the encumbrance of the realty through the granting of a mortgage securing the loan.

- A debenture is a document that either creates or acknowledges a debt, and the debt is one without collateral.

Key Term

- Long term loans

-

Loans that are generally understood to be over a year in duration – often much longer.

Long Term Loans

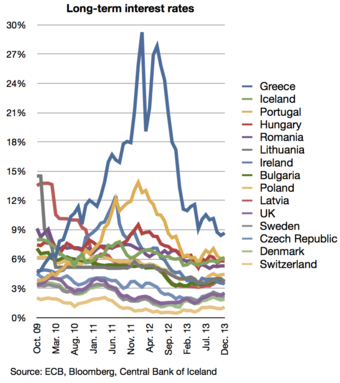

Long term loans are generally over a year in duration and sometimes much longer. Three common examples of long term loans are government debt, mortgages, and bonds or debentures .

Government Debt

Government debt (also known as public debt or national debt) is the debt owed by a central government. Government debt is one of numerous methods of financing government operations.

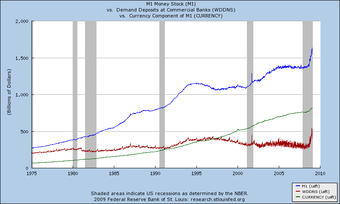

Governments may create money to monetize their debts, thereby removing the need to pay interest. This practice, also known as quantitative easing, reduces government interest costs but does not actually cancel government debt. Governments usually borrow by issuing securities, government bonds, and bills. Less creditworthy countries sometimes borrow directly from a supranational organization (e.g., the World Bank) or international financial institutions.

Government bonds are issued by a national government. Such bonds are often denominated in the country’s domestic currency, and they are sometimes regarded as risk-free bonds, as national governments can raise taxes or reduce spending up to a certain point. In many cases, governments print more money in order to redeem the bond at maturity. Most governments in developed countries are prohibited by law from printing money directly, as this function is generally assigned to their central banks. However, central banks may buy government bonds in order to finance government spending, thereby monetizing the debt.

Mortgage Loan

A mortgage is a loan secured by real property. It requires a mortgage note affirming the existence of the loan and the encumbrance of the realty through the granting of a mortgage securing the loan. In U.S. property law, a mortgage occurs when an owner (usually of a fee simple interest in realty) pledges his or her interest (right to the property) as security or collateral for a loan.

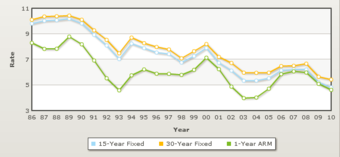

A home buyer or builder can obtain a loan to purchase or secure against the property from a financial institution, such as a bank, or either directly or indirectly through intermediaries. Features of mortgage loans such as the size of the loan, maturity of the loan, interest rate, method of paying off the loan, and other characteristics can vary considerably.

Mortgage loans are generally structured as long term loans, the periodic payments for which are similar to an annuity and calculated according to the time value of money formulae. The most basic arrangement requires a fixed monthly payment over a period of ten to thirty years, depending on local conditions. Over this period, the principal component of the loan (the original loan) is slowly paid down through amortization. However, many variants on this arrangement are possible within different countries.

Many types of mortgages are used worldwide, though several characteristics, subject to local regulations and legal requirements, define most mortgages:

- Interest: Interest may be fixed for the life of the loan or variable, and it may change at certain pre-defined periods; the interest rate may rise or fall.

- Term: Mortgage loans generally have a maximum term, or a number of years after which an amortizing loan will be repaid. Some mortgage loans may have no amortization or require full repayment of any remaining balance at a certain date; others may have negative amortization.

- Payment amount and frequency: The amount paid per period and the frequency of payments may change, or the borrower may have the option to increase or decrease the amount paid.

- Prepayment: Some types of mortgages may limit or restrict prepayment of all or a portion of the loan, or they may require payment of a penalty to the lender for prepayment.

Debenture

A debenture is a document that either creates or acknowledges a debt, and the debt is one without collateral. In corporate finance, debenture refers to a medium- to long-term debt instrument used by large companies to borrow money. In some countries, the term is used interchangeably with bond, loan stock, or note. A debenture thus resembles a certificate of loan or a loan bond, evidencing the fact that the company is liable to pay a specified amount with interest. Although the money raised by the debenture becomes part of the company’s capital structure, it does not become share capital.

In general, debentures are freely transferable by the debenture holder. Debenture holders have no right to vote in the company’s general meetings of shareholders, but they may hold separate meetings or votes (regarding, for instance, changes to the rights attached to the debentures). The interest paid to debenture holders is a charge against profit in the company’s financial statements.

19.5.5: Corporate Bonds

A corporate bond is issued by a corporation seeking to raise money in order to expand its business.

Learning Objective

Explain how an organization can finance their operations through bonds

Key Points

- The term corporate bond is typically applied to longer-term debt instruments with a maturity date falling at least a year after the issue date.

- Corporate bonds are often listed on major exchanges (and referred to as listed bonds) and ECNs, and the coupon (i.e., the interest payment) is usually taxable.

- Corporate debt falls into several broad categories: secured debt and unsecured debt; senior debt and subordinated debt.

Key Term

- default

-

The condition of failing to meet an obligation.

Corporate Bonds

A corporate bond is issued by a corporation seeking to raise money in order to expand the business. The term corporate bond is usually applied to longer-term debt instruments with a maturity date falling at least a year after the issue date. (The term commercial paper is sometimes used for instruments with a shorter maturity period. ) Sometimes, corporate bond is used in reference to all bonds with the exception of those issued by governments in their own currencies. Strictly speaking, however, the term only applies to bonds issued by corporations .

Corporate bonds are often listed on major exchanges (and known as listed bonds) and ECNs, and the coupon (i.e., the interest payment) is usually taxable. Sometimes, the coupon can be zero with a high redemption value. However, though many are listed on exchanges, the vast majority of corporate bonds in developed markets are traded in decentralized, dealer-based, over-the-counter markets.

Corporate bonds and corporate debt fall into several broad categories:

Secured loan/debt:

A secured loan is one in which the borrower pledges some asset (e.g., a car or property) as collateral for the loan, which in turn becomes a secured debt owed to the creditor of the loan. The debt is thus secured against the collateral, and in the event that the borrower defaults, the creditor takes possession of the collateral asset and may sell it in order to recover some or all of the amount loaned.

Unsecured loan/debt:

The opposite of secured debt is unsecured debt, which is not linked to any specific piece of property. In the case of unsecured debt, the absence of collateral means that the creditor may only satisfy the debt against the borrower. The comparative security of secured debt for the lender generally results in lower interest rates for secured than for unsecured debt. However, the borrower’s credit history and ability to repay, as well as the expected returns for the lender, are factors that also affect rates.

Senior debt:

Senior debt, frequently issued in the form of senior notes and sometimes referred to as senior loans, is debt that takes priority over unsecured or junior debt owed by the issuer. Senior debt has seniority over subordinated debt in the issuer’s capital structure. In the event of bankruptcy or liquidation, senior debt must be repaid before any other creditors receive payment. Senior debt is often secured by collateral on which the lender has placed a first lien, which typically covers all the assets of a corporation and is frequently used in the resolution of credit lines.

Subordinated debt:

Subordinated debt is repaid after other debts in the case of liquidation or bankruptcy. Such debt is referred to as subordinate, because the debt providers (the lenders) have subordinate status relative to the normal debt. Subordinated debt has a lower priority than the issuer’s other bonds and ranks below the liquidator, government tax authorities, and senior debt holders in the hierarchy of creditors. Because subordinated debt is repaid only after other debts have been paid, they are riskier for lenders. Subordinated debt is also unsecured and has a lower priority than any additional debt claim on the same asset.

In the event of a default, the higher one’s position in the company’s capital structure, the stronger one’s claims to the company’s assets.