4.1: Culture

4.1.1: Defining Organizational Culture

Organizational culture can be defined as the collective behavior of people within an organization and the meanings behind their actions.

Learning Objective

Define culture and it’s conceptual development within the context of organizations and innovation

Key Points

- Culture is inherently intangible, and a static definition of culture struggles to encapsulate the meaning and implications of its role in an organization.

- One way to define culture is simply as the overarching mentality and expectation of behavior within the context of a given group (e.g., an organization, business, country, etc.).

- Corporate culture is usually derived from the top down (i.e., upper management sets the tone) and comes in the form of expectation and consistency throughout the organization.

- Culture can be manipulated and altered depending on leadership and members. Instilling positive culture that promotes effective employee behavior is a manager’s primary task.

- While there are many models for and perspectives on defining culture within an organization, models such as Geert Hofstede’s, Edgar Schein’s and Gerry Johnson’s are useful in properly framing a comprehensive definition.

Key Term

- culture

-

The beliefs, values, behavior, and material objects that constitute a people’s way of life.

Culture is inherently intangible, and a static definition of culture struggles to encapsulate the meaning and implications of its role in an organization. One way to define culture is simply as the overarching mentality and expectation of behavior within the context of a given group (e.g., an organization, business, country, etc.). Culture provides a guiding perspective on how individuals within that group should act, and what meaning can be derived from those actions. Expectation, traditions, value, ethics, vision, and mission can all both communicate and reinforce a given group culture. Above all else, culture must be shared internally; otherwise it loses its form.

Culture in Business

Corporate culture is usually derived from the top down (i.e., upper management sets the tone) and comes in the form of expectation and consistency throughout the organization. All employees and managers must uphold these cultural expectations to generate a working environment that correlates to cultural expectations. The shared assumptions should be implicit in behavior and explicit in the mission, vision and ethics statements of the organization. Consistency between expectation and action is key here.

People working at Wikimedia

Even small things, such as the way an office space is set up, can set the tone for organizational culture.

Culture and Adaptability

Culture can be manipulated and altered, depending on leadership and members. Let’s take the simple example of a car dealership. Selling cars is usually a commission business, where the salesperson is a central success factor. Many car dealerships find that competition is an effective cultural component and embed that into the organization. This is easily accomplished with the right tools. A car dealership owner may hire specifically for competitiveness, making it clear that this is the type of individual they want to hire. The owner can create high variable salary and low fixed salary so that high performers are much more highly prized and rewarded than ineffective salespeople. The owner could give out awards at the end of each quarter to the most successful salesperson. The list could go on and on, but the important consideration here is how strategy and culture can be intertwined to evolve together.

Perspectives on Culture

Culture is a deeply important element of organizations and societies that is studied extensively in a variety of disciplines. This has generated more definitions of culture and how to go about empirically measuring it than could be touched upon in one overview. However, a few important perspectives for a business manager include:

- Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory – Postulates that cultural differences to be aware of include different perspectives on power distance, masculinity (vs. femininity), individualism (vs. collectivism), avoidance of uncertainty, long-term orientation, and indulgence.

- Schein’s Cognitive Levels of Organizational Culture – Edgar Schein believes that culture can be viewed most simply via artifacts (e.g., facilities, dress code, etc.), more acutely through values (e.g., focus on quality, loyalty or other central values) and most complexly through tacit assumptions (i.e., unspoken rules of behavior and other intangible expectations that are very difficult to observe and measure).

- Gerry Johnson’s Cultural Web – This includes the elements of culture, which is an important aspect of how we define it. Johnson underlines the paradigm, control system, organizational structure, power structure, symbols, stories, and myths as central determinants of what a given organizational culture stands for.

While each of these theories is complex, all together they help create a clearer picture of what exactly culture is and how it applies to managers and organizations.

4.1.2: The Impact of Culture on an Organization

Culture is a malleable component of an organization that can adapt and evolve through influences to create value.

Learning Objective

Identify the central components of an organization or company that result from the influence cultural dispositions

Key Points

- Culture, particularly in large organizations that have a great deal of momentum, can be difficult to influence or change.

- Understanding how to change an organizational culture requires some insight into what creates culture in the first place and how altering those components may impact meaningful cultural development.

- Some examples of organizational facets that influence culture are mission and vision statements, control systems, organizational structures, power hierarchies, symbols, routines, and internal stories and myths.

- When integrating culture change, it is important to update mission and vision statements, ensure buy-in from upper management, update control systems and power hierarchies, hire people representative of the desired culture (and remove those who are not), and update the corporate ethos.

Key Terms

- paradigm

-

A system of assumptions, concepts, values, and practices that constitutes a way of viewing reality.

- joint venture

-

A cooperative partnership between two individuals or businesses in which profits and risks are shared.

- inertia

-

The property of a body that resists any change to its uniform motion; equivalent to its mass. Figuratively, in a person, unwillingness to change.

Culture, particularly in large organizations that have a great deal of internal momentum, can be difficult to influence or change. The size of an organization and the strength of its culture are the biggest contributors to cultural inertia. Big and strong organizational cultures will have a powerful tendency to continue moving in the direction they are already moving (momentum). Therefore, managers must understand not only how to create culture, but also how to change it when necessary to ensure a positive, efficient and ethical culture.

Cultural Factors

Understanding how to change an organizational culture requires some insight into what creates culture in the first place and how altering those components may impact meaningful cultural development. Gerry Johnson’s cultural web offers great clarity about how an organizational culture responds to and reflects influencing factors. These include:

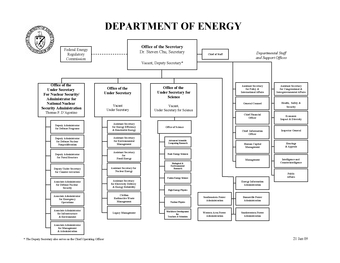

- The paradigm: The mission statement, vision, ethics statement, and other overt definitions of culture.

- Control systems: The processes in place to monitor what is going on, such as an employee handbook.

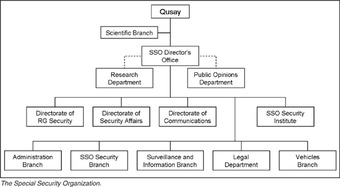

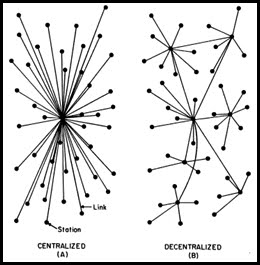

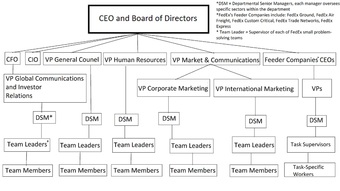

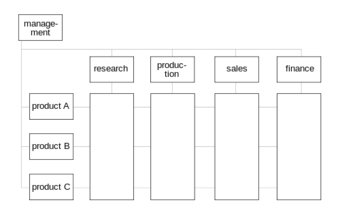

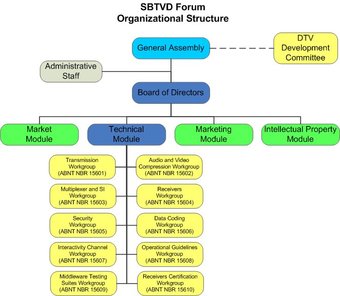

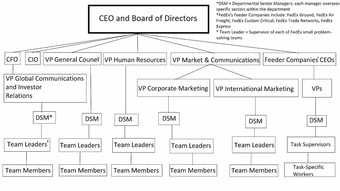

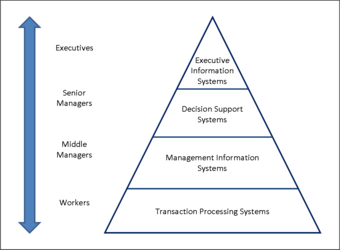

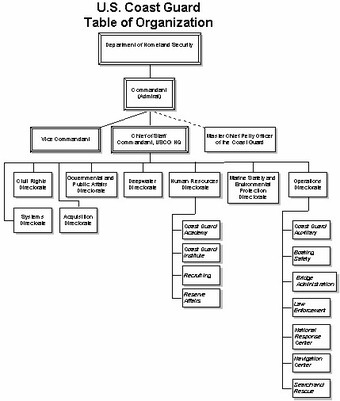

- Organizational structures: This comes down to the hierarchy, or who reports to whom and why.

- Power structures: Similar to the organizational structure above, this pertains to who has the power to make decisions.

- Symbols: Most organizations have brand images and other symbols which represent what the culture stands for (logos, etc.).

- Rituals and routines: In the business setting this is simply the way in which group interactions are organized. One example is the weekly staff meeting.

- Stories and myths: CEOs and other figureheads often have stories or legends associated with them; this generates culture through idolatry.

While these are only a few of the elements of culture, they capture a wide variety of components that managers can use to influence and change the general cultural predisposition.

Implementing Culture Change

Cummings and Worley identify a useful way to frame the stages or steps in integrating broad organizational change through cultural reform in six stages, which correlates well with the factors identified above. These stages include:

- Ensure clarity in the strategic vision. This means making sure that the mission statement, vision statement and overall strategy work together to create one strong culture statement. The vision in particular must describe the new culture forcefully and persuasively.

- Ensure buy-in from the top down. This means communicating (and often determining) specific aspects of needed culture change at the upper managerial level.

- Lead by example. Top management needs to exhibit the kinds of values and behaviors that they want to see in the rest of the company.

- Identify areas in the organizational structure and control systems which require updates to conform with the new or adapted culture. This includes altering employee handbooks, compensation strategies, hierarchy, decision-making authority and other central components of structure.

- Follow through on the mandate. Terminating employees who do not conform to the desired culture is difficult. But it allows you to bring in new talent that aligns better with your desired culture. Ensuring proper emphasis on the new culture in training materials is useful in this process.

- Finally, ensure that the ethical and legal implications of the adapted culture are understood, planned for and in line with corporate ethics.

Joint ventures and mergers and acquisitions usually require large cultural changes. When different cultures come together it is wise to expect some degree of culture-clash and differences of opinion. Managers, particularly upper management, must be aware of the implications of cultural change, the facets of organizational culture and the steps involved in altering it. While this model describes a long process that is generally more applicable to large cultural overhauls, the general strategy is useful for managers leading meaningful cultural change at all levels.

4.1.3: Types of Organizational Culture

While there is no single “type” of organizational culture, some common models provide a useful framework for managers.

Learning Objective

Differentiate between varying organizational culture tendencies, specifically within the context of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory

Key Points

- While there are many ways to divide and define culture into “types,” Geert Hofstede, Edgar Schein, and Charles Handy provide three basic theoretical frameworks.

- Hofstede postulates six dimensions of culture based on a study conducted at IBM offices in 50 different countries. These include power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism (vs. collectivism), masculinity (v.s femininity), long-term orientation, and restraint.

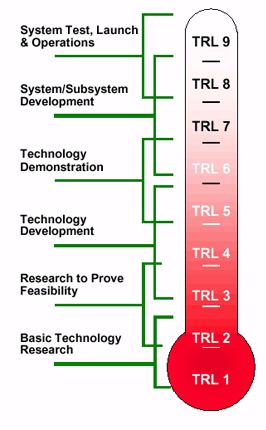

- Edgar Schein organizes culture into three types: artifacts (tangible cultural displays), values, and assumptions.

- Charles Handy identifies four types of organizational culture: power, role, task, and person. Each type of culture has strong implications on types of organizational structure.

Key Terms

- normative

-

Of, pertaining to, or using a norm or standard.

- cultural

-

Of or pertaining to culture.

Several methods have been used to classify organizational culture. While there is no single “type” of organizational culture, and cultures can vary widely from one organization to the next, commonalities do exist, and some researchers have developed models to describe different indicators of organizational cultures. We will briefly discuss the details of three influential models on organizational cultures.

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions

While there are several types of cultural and organizational theory models, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory is one of the most cited and referenced. Hofstede looked for global differences in culture across 100,000 IBM employees in 50 countries in an effort to determine the defining characteristics of global cultures in the workplace. With the rise of globalization, this is particularly relevant to organizational culture.

Through this process, he underlined observations that relate to six different cultural dimensions (originally there were five, but they have been updated in response to further research):

- Power distance: Power distance is simply the degree to which an authority figure can exert power and how difficult it is for a subordinate to contradict them.

- Uncertainty avoidance: Uncertainty avoidance describes an organization’s comfort level with risk-taking. As risk and return are largely correlative in the business environment, it is particularly important for organizations to instill a consistent level of comfort with taking risks.

- Individualism vs. collectivism: This could best be described as the degree to which an organization integrates a group mentality and promotes a strong sense of community (as opposed to independence) within the organization.

- Masculinity vs. femininity: This refers to the ways that behavior is characterized as “masculine” or “feminine” within an organization. For example, an aggressive and hyper-competitive culture is likely to be defined as masculine.

- Long-Term Orientation: This is the degree to which an organization or culture plans pragmatically for the future or attempts to create short-term gains. How far out is strategy considered, and to what degree are longer-term goal incorporated into company strategy?

- Indulgence vs. Restraint: This pertains to the amount (and ease) of spending and fulfillment of needs. For example, a restrained culture may have strict rules and regulations for tapping company resources.

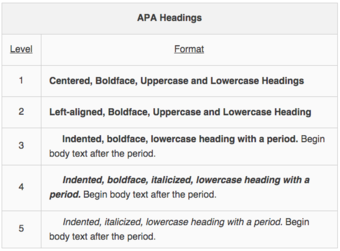

Edgar Schein’s Cultural Model

Edgar Schein’s model underlines three types of culture within an organization, which, as a simpler model than Hofstede’s, is somewhat more generalized. Schein focuses on artifacts, values, and assumptions:

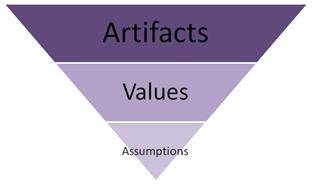

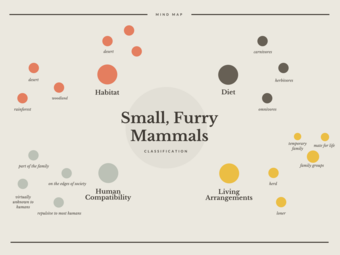

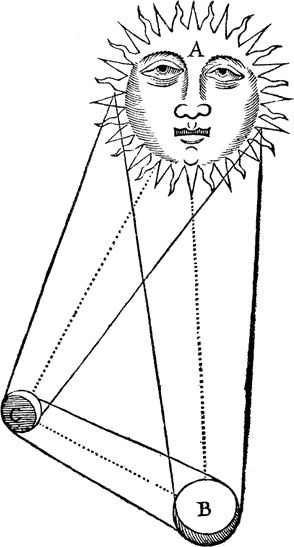

Schein’s model

Diagram of Schein’s organizational behavior model, which depicts the three central components of an organization’s culture: artifacts (visual symbols such as office dress code), values (company goals and standards), and assumptions (implicit, unacknowledged standards or biases).

- Artifacts: The simplest perspective on culture is provided by the tangible artifacts that reveal specific cultural predispositions. How desks are situated, how people dress, how offices are decorated, etc., are examples of organizational artifacts.

- Values: Values pertain largely to the ethics embedded in an organization. What does the organization stand for? This is usually openly communicated with the public and demonstrated internally by employees. An example might be a non-profit organization trying to mitigate poverty. The values of charity, understanding, empowerment, and empathy would be deeply ingrained within the organization.

- Assumptions: The final type of culture, according to Schein, is much more difficult to deduce through observation alone. These are tacit assumptions that infect the way in which communication occurs and individuals behave. They are often unconscious, yet hugely important. In many ways, this correlates with Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. For example, a culture of avoiding risk wherever possible may be an assumption which employees act upon without realizing it, and without receiving any directives to do so. High power distance could be another, where employees intuit that they should show a high degree of deference to their superiors without being specifically told to do so.

Charles Handy’s Four Types of Culture

Charles Handy put forward a framework of four different types of culture that remains relevant today. His four types include:

- Power culture: In this type of culture, there is usually a head honcho who makes rapid decisions and controls the organizational direction. This is most appropriate in smaller organizations, and require a strong sense of deference to the leader.

- Role culture: Structure is defined and operations are predictable. Usually this creates a functional structure, where individuals know their job, report to their superiors (who have a similar skill set), and value efficiency and accuracy above all.

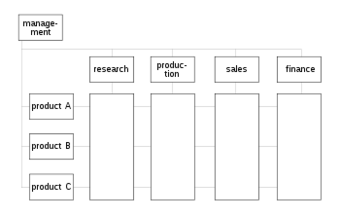

- Task culture: Teams are formed to solve particular problems. Power is derived from membership in teams that have the expertise to execute a task. Due to the importance of given tasks, and the number of small teams in play, a matrix structure is common.

- Person culture: In this type of culture, horizontal structures are most applicable. Each individual is seen as valuable and more important than the organization itself. This can be difficult to sustain, as the organization may suffer due to competing people and priorities.

While there are many other ways to divide and define culture, these three offer a good window into the literature surrounding cultural types.

4.1.4: Core Culture

Core culture is the underlying value that defines organizational identity through observable culture.

Learning Objective

Identify the general definition and characteristics of a healthy core culture, alongside how this translates into observable culture.

Key Points

- Core and observable culture are two facets of the same organizational culture, with core culture being inward-facing and intrinsic and observable culture being more external and tangible (outward-facing).

- In essence, core culture defines the values and assumptions of an organization, as described by Edgar Schein’s Model of Organizational Culture.

- Core culture is made up of the intangible values and ethos that define an organization’s cultural framework. Observable culture is the external reflection of this cultural perspective.

- Management is tasked with both the creation and consistent application of core culture at the organizational level.

Key Term

- Core Culture

-

The underlying value that defines the organization’s identity through observable culture.

Core Culture and Observable Culture

Core and observable culture are two facets of the same organizational culture, with core culture being inward-facing and intrinsic and observable culture being more external and tangible (outward-facing). Core culture, as the name denotes, is the root of what observable culture will communicate to stakeholders. Core culture is more ideological and strategic, representing concepts such as vision (long-term agenda and values), while observable culture is more of a communications channel (i.e., stories, logos, symbols, branding, mission statement, and office environment).

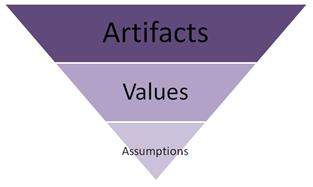

Edgar Schein and Core Culture

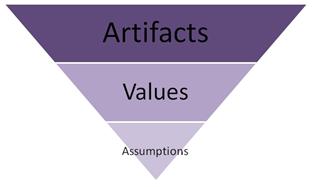

One useful theoretical framework to consider when differentiating between core and observable culture is Edgar Schein’s Organizational Culture Model. This mode simply and efficiently illustrates the cultural facets of a given organization as an upside-down triangle.

Schein’s model of organizational culture

Diagram of Schein’s organizational behavior model, which depicts the three central components of an organization’s culture: artifacts (visual symbols such as office dress code), values (company goals and standards), and assumptions (implicit, unacknowledged standards or biases).

The broader base at the top of the inverted pyramid represents artifacts, the simplest and most physical (i.e., observable) elements of a given culture. This includes the way desks are situated in an office (collaborative or individualistic?), the colors and shapes used in the logo, the general dress code, etc.

The next level is values, which bridges the gap between observable and core culture. Values are explicitly and observably stated in organizational literature (i.e., the employee handbook and mission statement), but also implicitly executed in individual behaviors. While it is observable when the CEO makes a public statement for shareholders or when the promotional team writes a press release, it is also derived directly from discussions of what the core culture is. This is where observable culture begins to transform into core culture.

The final component identified by Schein is parallel with the concept of core culture: assumptions. The assumptions made by the individuals within an organization are so intimately tied to the core organizational culture that they are virtually unrecognizable. In many ways, one could equate core culture with an individual’s subconscious. While our subconscious so often drives our conscious behavior, we rarely realize it. Core culture has the same relationship with observable culture: core culture is created first, and ultimately drives the visible cultural aspects of the organization.

Creating Core Culture

Organizational culture, both observable and core, is created first at the managerial level. Leaders must define not only what it is they are working towards, but also how the organization will come to define itself during the process. The core culture created by leadership sets the tone for employee behavior and assumptions in the future.

Upper management must decide which values and ethos will constitute the core of the organizational culture, and then instill this internally, in their employees, and communicate it externally, to stakeholders (via observable culture). Management is tasked with both the creation and consistent application of core culture at the organizational level.

4.2: Shaping Organizational Culture

4.2.1: Building Organizational Culture

Managers are tasked with both creating and communicating a consistent organizational culture.

Learning Objective

Describe strategies used by managers to create and maintain a consistent organizational culture.

Key Points

- The process of instilling culture into an organization involves communicating and integrating a broad cultural framework throughout the organizational process.

- A strong culture is integral to long-term organizational sustainability and success; a primary responsibility of management is to both define and communicate this sense of shared organizational culture.

- Organizational culture is often defined by the work environment that management creates (i.e., mission statement, organizational structure, rules, symbols, etc.).

- Managers must be careful to instill the culture that is most conducive to both the strategy and objectives of the organization over the long term.

Key Terms

- organizational culture

-

The collective behavior of the people who make up an organization, including values, visions, norms, working language, systems, symbols, beliefs, and habits.

- culture

-

The beliefs, values, behavior, and material objects that constitute a people’s way of life.

Organizational culture refers to the collective behavior of the people who make up an organization; this includes their values, visions, norms, working language, systems, symbols, beliefs, and habits. Organizational culture affects the way people and groups interact with each other, with clients, and with stakeholders. A strong culture is integral to long-term organizational sustainability and success, and one of management’s primary responsibilities is to both define and communicate this sense of shared culture.

The process of ingraining culture into an organization is simply one of communicating and integrating a broad cultural framework throughout the organizational process. Central to this process is ensuring that each and every employee both understands and aligns with the values and direction of the broader organization. This creates a sense of community among employees and ensures that the broader objectives and mission of the organization are clear.

While there are a variety of cultural perspectives and many organizational elements within a culture, the initial process of instilling culture is relatively consistent from a managerial perspective. The creation of a given culture is often defined by management’s strategy for addressing the following issues:

- The paradigm: Management determines both the mission and vision of the organization and sets a groundwork for the values that employees are expected to align with. Determining these factors and communicating them effectively are absolutely critical to successfully instilling organizational culture.

- Control systems: An example of this may be an employee handbook where behavioral expectations are laid out explicitly (where possible) for employees to read and understand.

- Organizational structures: The choice of an organizational structure has enormous cultural implications for openness of communication, organization of resources, and flow of information.

- Power structures: Power and culture are often intertwined: the degree to which specific individuals are free (or not) to make decisions is indicative of the openness and fluidity of the organization.

- Symbols: All strong brands associate with symbols (think logos). These are not randomly selected: symbols show which specific facets of an organizational culture management considers most important.

- Rituals and routines: Routines are strong behavior modifiers that significantly impact the culture of a given organization. A looser and more open work environment (limited routines, high individual freedom) may create more innovation while heavily structured routines may create more efficiency and predictability.

- Stories and myths: Finally, stories are powerful communicators of culture. Walmart uses Sam Walton’s founding as a powerful myth to promote efficiency and the desire to try new things and integrate various products and services. This is organizationally defining.

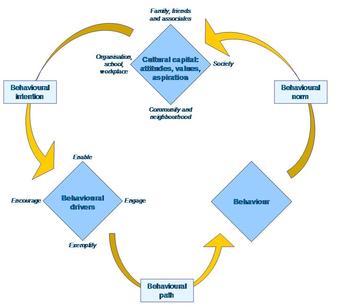

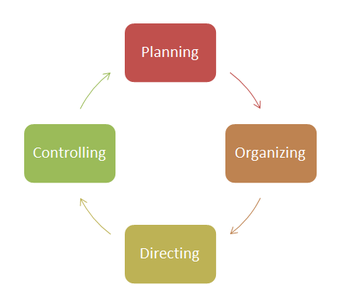

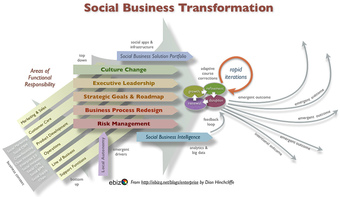

Cultural change in an organization

The feedback loop of cultural change in an organization involve people’s intentions to enable, engage, encourage, and exemplify the new desired behaviors; this in turn influences the frequency of behaviors. After enough reinforcement, those behaviors become the norm, which self-reinforces through increasing people’s exemplification of those behaviors.

Overall, managers must be aware of their role as cultural ambassadors and their responsibility in creating a context for successfully instilling organizational culture. For example, promoting a strong authoritarian hierarchy and strong innovation would be an oversight in the field of organizational culture from a management professional. Managers must be careful to instill the culture that is most conducive to both the strategy and objectives of the organization over the long term.

4.2.2: Communicating Organizational Culture

Management is tasked with both creating culture and accurately communicating it across the organization.

Learning Objective

Recognize the role of management in communicating and teaching organizational culture to employees and subordinates.

Key Points

- Corporate culture is used to control, coordinate, and integrate company subsidiaries.

- The role of the manager is essential to the successful communication of a given organizational culture because managers are figureheads and role models for how individuals in the organization should behave.

- Organizations should strive for what is considered a “healthy” organizational culture to increase productivity, growth, efficiency, and to reduce counterproductive behavior and turnover of employees.

Key Term

- organization

-

A group of people or other legal entities with an explicit purpose and written rules.

Corporate culture is used to control, coordinate, and integrate company subsidiaries. Culture runs deeper than this definition, however, because culture also represents the embedded values, traditions, beliefs, and behaviors of a given group. Culture is indicative not only of what individuals pursue and believe in, but also their behaviors, assumptions, and communications. As a result, culture is both complex to create and challenging to communicate and imbue within the organization.

Communicating Culture

The role of the manager is essential to the successful communication of a given organizational culture because managers are figureheads and role models for how individuals in the organization should behave. While it is too simplistic to say that culture is a top-down communicative process, there is relevance to the idea that culture generally begins with the founders of the organization and the values they emphasize in the organizational growth and hiring process.

Leaders have a number of tools and strategies at their disposal to communicate culture. Some of the most critical of these are structure, hierarchy, mission and vision statements, employee handbooks, hiring processes, and employee training and initiation. With many diverse tools for communicating culture comes the challenge of aligning each perspective for consistency of message: for instance, the employee training program must emphasize the same values as the mission statement and must match the executive mandate for organizational structure and design.

Communication is the core tool for managing this cultural integration, enabling executives to remind employees what the organization stands for and why it’s important. Holding company-wide quarterly meetings to emphasize objectives and strategy and sending out emails with key successes and developmental challenges are great ways to keep the conversation going.

The Role of HR

It is also critical to make the hiring process match and promote the culture by hiring talent that is consistent with cultural expectations and implementing training programs that effectively emphasize what the organization stands for and why. Human resource professionals are tasked with identifying candidates with culturally consistent perspectives and with underlining the importance of cultural considerations in interviews and on-boarding processes.

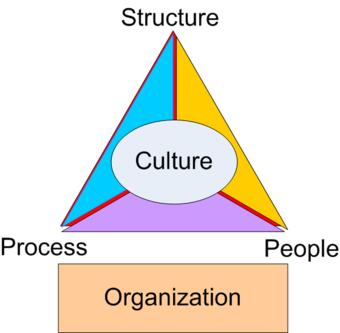

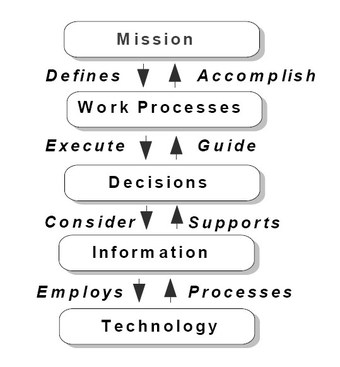

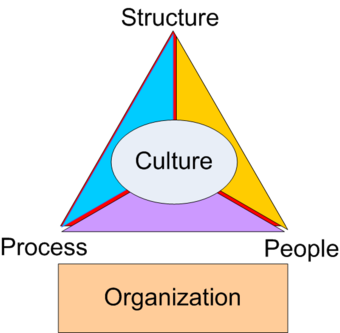

Organization triangle

This organization triangle illustrates the idea that structure, process, and the people involved all contribute to the culture of an organization.

4.2.3: Building a Culture of High Performance

A high-performing culture is a results-driven business culture focused on generating efficiency and completing objectives.

Learning Objective

Analyze the primary drivers and positive characteristics of a high-performing culture.

Key Points

- Every business has its own culture. High-performance cultures are specifically focused on setting and accomplishing objectives with a high degree of efficiency and efficacy.

- High-performing teams are an integral component of high-performance cultures.

- A high-performing team is a group of people with complementary talents and skills. They are given clear roles and are committed to a common purpose. This enables synergy.

- Culture is a combination of individual perspectives and the environment in which they operate. Business looking to create a high-performance culture must create an interdependent environment which empowers employee responsibility and decision-making.

Key Terms

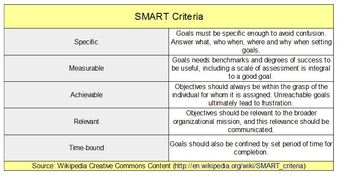

- SMART

-

Goal-setting criteria: Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, and Timely.

- performing

-

The stage of group development when the the team is able to function as a unit, finding ways to get the job done smoothly and effectively without inappropriate conflict or supervision.

- high-performing team

-

groups that are highly focused on their goals and that achieve superior business results.

Organizations need to be productive in order to achieve their goals. Over time, productivity can become a part of organizational culture, eventually becoming integrated into the company’s operations and processes. The business becomes known for its productivity, and high performance becomes second-nature for its employees. A high-performing culture is defined by a focus on generating and accomplishing objectives. There is a strong sense of both results-orientation and employee interdependence.

A High-Performing team

An effective way to achieve high-performing culture is to create high-performing teams. A high-performing team is best defined as a group of interdependent employees whose skills and personalities complement one another and lead to above-average operational results. High-performance teams are a central building block of high-performance culture, and they thrive in innovative and empowering environments.

Leadership in any team environment is critical to success, but leadership within a high-performance culture is often complex. While leadership is normally static in a hierarchical environment, high-performance teams benefit from shared leadership by utilizing the different talents and perspectives of each team member in the decision-making process. This creates a strong culture of shared leadership which in turn can generate above-average results and highly motivated employees who trust one another.

Culture is defined by creating its own consciousness in an organization, indicating shared norms and values. These shared values are central elements of the organization, as they generate buy-in and dedication from employees. These shared values create an expectation of success, both professional and personal, that can create high levels of trust and shared accountability. In short, shared values are key to creating strong team dynamics.

There are ten elements in particular that are important to successfully integrating high-performance teams within an organizational culture:

- Participative leadership – Involve the entire team when making decisions, and rely on specialists only when applicable.

- Effective decision making – Ensure that decision-making is both strategic and efficient. Group decision-making is often slowed when team dynamics are weak, which requires team-building to fix.

- Open and clear communication – As always with group dynamics, communication is key to success. Ensure everyone is speaking and listening.

- Valued diversity – Team synergy is lost when groupthink dominates the discussion. Instill open-mindedness and dispel social fears of disagreeing.

- Mutual trust – Reliance upon one another, and trust in each other’s skills and capabilities, allows for less duplication of work and more overall synergy.

- Managing conflict – Conflict is inevitable and not necessarily a bad thing. Deal with it calmly and without personal biases or emotions. Let the best ideas win.

- Clear goals – SMART objectives are essential to high performance, just as understanding where one is going is essential to finding the best route.

- Defined roles and responsibilities – Everyone should have a clear understanding of why they are on the team and what they are responsible for.

- Coordinated relationships – Building strong team dynamics requires team members to understand each other and build strong relationships. Utilize ice-breaking activities and promote casual discussion to get this started.

- Positive atmosphere – Wherever possible, make sure the general perspective is one of constructive commentary. Maintaining a positive outlook empowers communication and improves team spirit.

New York Yankees

A Great Team

4.3: Adapting and Innovating

4.3.1: Benefits of Innovation

Innovation may be linked to positive changes in efficiency, productivity, quality, competitiveness, and market share, among other factors.

Learning Objective

Identify the organizational benefits derived through enabling internal innovation

Key Points

- Innovation is the development of customer value through solutions that meet new needs, unarticulated needs, or existing market needs in unique ways.

- Innovative employees increase productivity by creating and executing new processes which in turn may increase competitive advantage and provide meaningful differentiation.

- Managers who promote an innovative environment can see value through increased employee motivation, creativity, and autonomy; stronger teams; and strategic recommendations from the bottom up.

- Clarity about and understanding of roles, increased responsibilities, strategic partnerships, senior management support, organizational restructuring, and investment in human resources can all enrich organizational culture and innovation.

Key Terms

- innovation

-

A change in customs; something new and contrary to established customs, manners, or rites.

- productivity

-

The rate at which goods or services are produced by a standard population of workers.

- efficiency

-

The extent to which a resource, such as electricity, is used for the intended purpose; the ratio of useful work to energy expended.

Defining Innovation

Innovation is the development of customer value through solutions that meet new, undefined, or existing market needs in unique ways. Solutions may include new or more effective products, processes, services, technologies, or ideas that are more readily available to markets, governments, and society.

Innovation is easily confused with words like invention or improvement. They are, however, different terms. Innovation refers to coming up with a better idea or method, or integrating a new approach within a contextual model, while invention is more statically about creating something new. Innovation refers to to finding new ways to do things, while improvement is about doing the same thing more effectively.

Organizational Benefits of Innovation

From an organizational perspective, managers encourage innovation because of the value it can capture. Innovative employees increase productivity through by creating and executing new processes, which in turn may increase competitive advantage and provide meaningful differentiation. Innovative organizations are inherently more adaptable to the external environment; this allows them to react faster and more effectively to avoid risk and capture opportunities.

From a managerial perspective, innovative employees tend to be more motivated and involved in the organization. Empowering employees to innovate and improve their work processes provides a sense of autonomy that boosts job satisfaction. From a broader perspective, empowering employees to engage in broader organization-wide innovation creates a strong sense of teamwork and community and ensures that employees are actively aware of and invested in organizational objectives and strategy. Managers who promote an innovative environment can see value through increased employee motivation, creativity, and autonomy; stronger teams; and strategic recommendations from the bottom up.

Managers can accomplish this through providing top-down support to employees, providing clear roles and responsibilities while allowing individuals the freedom to pursue these as they see fit. Supporting the HR and IT departments so that they can provide training and tools for higher employee efficiency can contribute substantially to a culture of internal innovation. This requires open-minded and motivational leaders in managerial positions who are capable of steering employee efforts without diminishing employee creativity.

4.3.2: Characteristics of Innovative Organizations

According to recent research, companies that make a commitment to innovation are exceptional performers in their respective industries.

Learning Objective

Outline the critical success factors and characteristics of an adaptable and innovative organizational culture

Key Points

- Being receptive to new business ideas means being receptive to the idea that mistakes are a necessary part of the process.

- Everyone in the business needs to keep an open mind and develop the capacity to look at things with fresh eyes.

- It is likely that some successful innovations will result from chance discoveries.

- Managers must understand that employees too mired in routine work and too criticized for trying new methods will inherently fail to create innovations that may drive organizational growth.

Key Term

- innovation

-

A change in customs; something new and contrary to established customs, manners, or rites.

Many business experts argue that companies that make a substantial commitment to innovation and entrench it deeply throughout their culture will perform exceptionally well. But how can innovation be facilitated within the organizational framework? The following are some examples of characteristics that lead to successful innovation.

Accept Mistakes as Part of the Process

A Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing researcher was looking for ways to improve the adhesives used in 3M tapes that he discovered an adhesive that formed itself into tiny spheres. At first, it seemed as though his work was a failure. However, the new adhesive was later used on Post-it notes—a great innovation and business success for the company. Being receptive to new business ideas means being receptive to mistakes as a necessary, and sometimes even crucial, part of the process.

Keep an Open Mind and Think Laterally

Possibilities for innovation exist everywhere. To realize them, everyone in the business needs to keep an open mind and develop the capacity to look at things with fresh eyes.

The classic example of a company that completely transformed itself as a result of lateral thinking is the Finnish company Nokia, whose original core business was wood pulp and logging. When the collapse of communism opened the Russian market to the west, Nokia’s core business was seriously threatened by cheaper imports from Russia’s seemingly limitless forests. In the deep recession of the early 1990s, Nokia’s management concluded that the only real competitive advantage they retained was a very efficient communications system developed in the 1970s that helped them keep in touch with their remote logging operations. That single realization transformed the company into one of the world’s most successful vendors of communications equipment.

Nokia cell phone

Nokia successfully transformed itself from a logging company to an electronic-communications company through innovation.

Managerial Implications

As is usually the case, these principles are easier said than done. Managers must carefully consider what type of work environment they project for their subordinates. Managers must understand that employees too mired in routine work and who are criticized for trying new methods will inherently fail to create innovations that may drive organizational growth. There is therefore a balancing act between enabling employees to try new things and take risks vs. ensuring that tasks are completed on time with reasonable success.

4.3.3: Types of Innovation

There are three main modes of innovation: entrepreneurial value-based, technology-based, and strategic-reflexive.

Learning Objective

Outline a categorical overview of the potential ways in which innovation can be pursued and identified.

Key Points

- The entrepreneurial method of innovation is one in which change is initiated by an individual’s actions and drive to create a business venture of adaptation.

- Technology-based functional innovation occurs when the development of new technology drives innovation.

- The strategic-reflexive mode describes innovation that springs from individuals’ interactions with their organization’s common values and goals.

- Other types of innovation include: incremental, architectural, generational, manufacturing, financial, and cumulative.

Key Term

- innovation

-

A change in customs; something new and contrary to established customs, manners, or rites.

In business and economics, innovation is the catalyst to growth. Fuglsang and Sundbo (2005) suggest that there are three modes of innovation. The first is an entrepreneurial value-based method where change is initiated by an individual’s actions. The second is a technology-based functional mode in which the development of new technology drives innovation. The third is a strategic-reflexive mode in which innovation results from individual’s interactions with their organization’s set of common values and goals. The following graphic provides an example of the innovation process.

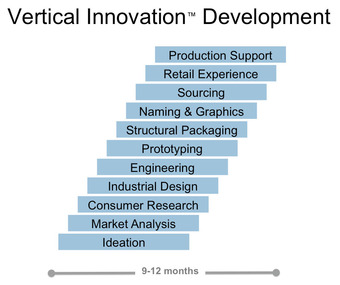

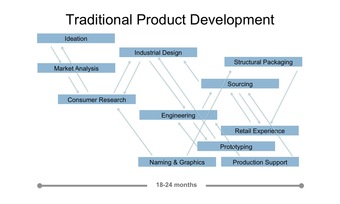

Innovation process

Innovation involves continuous improvement throughout phases of a development program. Phases can be iterative and recursive (meaning that they do not proceed linearly from one to the next; rather, earlier phases can be returned to for further improvement as needed). Such phases include market analysis and consumer research, which progress to design and prototyping, after which follow naming and packaging design and ultimately retail and production support.

Entrepreneurial Innovation

The innovation dimension of entrepreneurship refers to the pursuit of creative or novel solutions to challenges confronting a firm. These challenges can include developing new products and services or new administrative techniques and technologies for performing organizational functions (e.g., production, marketing, and sales and distribution).

Technological Innovation

Technological innovation takes place when companies try to gain a competitive advantage either by reducing costs or by introducing a new technology. Technological innovation has been a hot topic in recent years, particularly when coupled with the concept of disruptive innovation. Disruptive innovation is usually a technological advancement that renders previous products/services (or even entire industries) irrelevant. For example, the smartphone disrupted landlines, Netflix made Blockbuster obsolete, and mp3s have marginalized CD players.

Strategic Innovation

The strategic-reflexive mode of innovation is the most effective mode for change and innovation. While technological innovation is clear and easy to define, strategic innovation is inherently intangible and organizational in nature. Strategic innovation pertains to processes: how things are done as opposed to what the end product is. Strategic changes can be disruptive but are more often incremental. Incremental innovation is the idea that small changes, when effected in large volume, can rapidly transform the broader organization.

Walmart’s “Hub and Spoke” distribution model is a classic example of strategic innovation. Walmart succeeded thanks to process efficiency enabled via innovative operational paradigms and distribution strategies. By utilizing a maximum efficiency warehousing and distribution model, refined over and over again incrementally for improvement, Walmart has sustained a competitive advantage for decades.

Other Applications of Innovation

- Generational innovation involves changes in subsystems linked together with existing linking mechanisms.

- Architectural innovation involves changes in linkages between existing subsystems.

- Incremental innovations improve price/performance advancement at a rate consistent with the existing technical trajectory. Radical innovations advance the price/performance frontier by much more than the existing rate of progress.

- Manufacturing process innovation refers to all the activities required to invent and implement a new manufacturing process.

- Cumulative innovation is any instance of something new being created from more than one source. Remixing music is a direct example of cumulative innovation.

- Financial innovation has brought many new financial instruments with pay-offs or values depending on the prices of stocks. Examples include exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and equity swaps.

4.3.4: Speed of Innovation

Companies compete to adapt their products and services to incorporate new innovations first.

Learning Objective

Recognize the challenge inherent in adopting new ideas and the subsequent considerations pertaining to the speed of pursuing them.

Key Points

- Speed of innovation can pose a major challenge for organizations responding to external change.

- Profits depend on speed of innovation and the ability to attract customers. Big corporations used to dominate, but now industry leaders are often small, highly flexible groups that come up with great ideas, build trustworthy branding for themselves and their products, and market them effectively.

- A first-mover in a given innovation captures the obvious advantage of tapping into a new market before the competition. This can also allow the first-mover to capture the new technology for its own brand.

- First-movers encounter high fiscal risks in integrating a new product or services into their distribution, and failure often means sunk costs. Late-comers to the game can simply observe the success or failure of other competitors and make a more informed (and less risky) decision.

Key Terms

- Cannibalization

-

The reduction of sales or market share for one of your own products by introducing another.

- innovation

-

A change in customs; something new and contrary to established customs, manners, or rites.

The best ideas should implemented as quickly as possible—not just by the idea generator but also by others who have a different viewpoint. It is imperative that the idea is honed and refined while it is still fresh. For example, an idea for a new product might start out as a crude model built from polystyrene, foam, or cardboard that will evolve quickly into a more professional prototype.

Product Innovation Approach

Innovation involves continuous improvement throughout phases of a development program. Phases can be iterative and recursive (meaning that they do not proceed linearly from one to the next; rather, earlier phases can be returned to for further improvement as needed). Such phases include market analysis and consumer research, which progress to design and prototyping, after which follow naming and packaging design and ultimately retail and production support.

Robert Reich observes that profits in the old economy came from economies of scale, i.e., long runs of almost identical products. Thus we had factories, assembly lines, and industries. Today, profits come from speed of innovation and the ability to attract and keep customers. Therefore, while the big winners in the old economy were big corporations, today’s big winners are often small, highly flexible groups that devise great ideas, develop trustworthy branding for themselves and their products, and market these effectively. The winning competitors are those who are first at providing lower prices and higher value through intermediaries of trustworthy brands. To keep the lead, however, these companies have to keep innovating lest they fall behind the competition.

The Benefit of Moving First

Speed of innovation poses a major challenge for organizations responding to external change. A high rate of change can be seen in the shortening of product life cycles, increased technological change, increased speed of innovation, and increased speed of diffusion of innovations. These are key challenges for organizations, as the profit generation of new ideas must fit into a slimmer chronological window—thus underlining the great value of being a first-mover.

A first-mover in a given innovation captures the obvious advantage of tapping into a new market before its competitors. This also sometimes allows the first-mover to identify its brand with the new technology (i.e., saying “Google it” as shorthand for online search or calling any and all mp3 players an iPod). These branding hurdles must be tackled by any competitor following in the footsteps of the first-mover.

However, speed is not everything. First-movers encounter serious disadvantages, the most notable of which are freeloaders. First-movers also encounter high fiscal risks in integrating a new product or services into their distribution, and failure often means sunk costs. Latecomers to the game can simply observe the success or failure of other competitors and make more informed (and less risky) decisions about entering the market segment. Similarly, first movers must carefully consider cannibalization—where their new innovative products steal sales from their older products still on store shelves. Speedy innovation and moving first requires great foresight, planning, and managerial skill to execute effectively to minimize risks.

4.3.5: Sustainability Innovation

Sustainability innovation combines sustainability (endurance through renewal, maintenance, and sustenance) with innovation.

Learning Objective

Describe how organizational culture adds value by generating an innovative approach to sustainability issues

Key Points

- Sustainopreneurship describes using creative organizing to solve problems related to sustainability to in turn create social and environmental sustainability as a strategic objective and purpose.

- Solving sustainability-related problems is the be-all and end-all of sustainability entrepreneurship.

- Passively heated houses, solar cells, organic food, fair trade products, hybrid cars, and car sharing are all examples of sustainability innovations.

Key Terms

- sustainability

-

Configuring human activity so that societies are able to meet current needs while preserving biodiversity and natural ecosystems for future generations.

- innovation

-

A change in customs; something new and contrary to established customs, manners, or rites.

Sustainability is the capacity to endure through renewal, maintenance, and sustenance (or nourishment), which is different than durability (the capacity to endure through resistance to change). Innovation is the creation of new value through the use of solutions that meet new, previously unknown, or existing needs in new ways. Innovation should be pursued with sustainability in mind as a critical strategic objective, as the integration of new business ideas with the broader community and environment is central to long-term success.

Sustainability Entrepreneurship

“Sustainopreneurship” describes using creative business organizing to solve problems related to sustainability to create social and environmental sustainability as a strategic objective and purpose, while at the same time respecting the boundaries set in order to maintain the life support systems of the process. In other words, it is “business with a cause,” where the world’s problems are turned into business opportunities for deploying sustainability innovations. Sustainopreneurship is entrepreneurship and innovation for sustainability.

This definition is highlighted by three distinguishing dimensions. The first is oriented towards “why” – a company’s purpose and motive in adopting sustainable entrepreneurship. The second and third reflect two dimensions of “how” the process is carried out.

- Entrepreneurship consciously sets out to find or create innovations to solve sustainability-related problems.

- Entrepreneurship moves solutions to market through creative organizing.

- Entrepreneurship adds sustainability value while respecting life support systems.

Solving sustainability-related problems from the organizational frame is the be-all and end-all of sustainability entrepreneurship. This means that all three dimensions are simultaneously present in the process.

An example to provide context: Interface Global produces modular carpeting. Sustainability is the core operating mission and vision of the broader organization. Through greening their supply chain, minimizing water use, cutting electric costs, reducing fuel costs through better distribution, and a number of other innovative process improvements, Interface Global produces high quality carpets at a lower cost and smaller environmental footprint. The company created a sustainable business strategy through innovative thinking.

4.3.6: Social Innovation

Social innovation refers to new strategies, concepts, ideas, and organizations that meet societal needs of all kinds.

Learning Objective

Define social innovation and the potential positive outcomes of employing it within an organizational culture

Key Points

- Social innovation can refer to social processes of innovation, such as open source methods and techniques.

- Social innovation can also refer to innovations that have a social purpose, like microcredit or distance learning, and can be related to social entrepreneurship.

- Social innovation can take place within the government sector, the for-profit sector, the nonprofit sector (also known as the third sector), or in the spaces between them.

Key Terms

- social capital

-

The value created by interpersonal relationships with expected returns in the marketplace.

- innovation

-

A change in customs; something new and contrary to established customs, manners, or rites.

- social

-

Of or relating to society.

Example

- Prominent social innovators include Bangladeshi Muhammad Yunus, the founder of Grameen Bank, which pioneered the concept of microcredit for supporting innovators in multiple developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Social innovation refers to new strategies, concepts, ideas, and organizations that extend and strengthen civil society or meet societal needs of all kinds—from working conditions and education to community development and health.

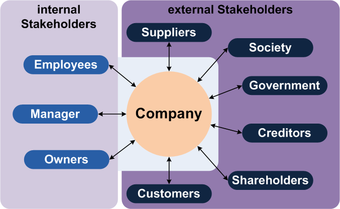

Organizations, both for for-profit and nonprofit, benefit enormously from incorporating social innovation into their operations. Giving back to to the community and empowering the individuals you work with and sell to (i.e., stakeholders) improves employee morale, grows wealth for potential customers, builds a strong brand, and underlines social responsibility and high ethical standards as central to the organizational character.

Example of a social innovation program

A health camp conducted for villagers as part of the Social Innovation Program at SOIL, in partnership with the Max India Foundation.

The term “social innovation” has overlapping meanings. Sometimes it refers to social processes of innovation like open-source methods and techniques. Other times it refers to innovations that have a social purpose, like microcredit or distance learning. The concept can also be related to social entrepreneurship (entrepreneurship is not necessarily innovative, but it can be a means of innovation). On occasion, it also overlaps with innovation in public policy and governance. Social innovation can take place within the government sector, the for-profit sector, the nonprofit sector (also known as the third sector), or in the spaces between them. Research has focused on the types of platforms needed to facilitate such cross-sector collaborative social innovation.

The Process of Social Innovation

Social innovation is often an effort of mental creativity that involves fluency and flexibility across a wide range of disciplines. The act of social innovation in a sector encompasses diverse disciplines within society. The social innovation theory of “connected difference” emphasizes three key dimensions of social innovation:

- First, it usually produces new combinations or hybrids of existing elements, rather than wholly new.

- Second, it cuts across organizational or disciplinary boundaries.

- Last, it creates compelling new relationships between previously separate individuals and groups. Social innovation is currently gaining visibility within academia.

Examples of Social Innovation

There are many examples of social innovation making a meaningful difference across the globe—from huge organizations like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funding multinational initiatives to small groups of community leaders collecting money to help buy new high school textbooks. Some specific examples include:

- The University of Chicago sought to develop social innovations that would address and ameliorate the immense problems caused by poverty in a largely immigrant city around the turn of the 20th century.

- Prominent social innovators include Bangladeshi Muhammad Yunus, the founder of Grameen Bank, who pioneered the concept of microcredit for supporting innovators in multiple developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

- Stephen Goldsmith, former Indianapolis mayor, engaged the private sector in providing many city services.

4.3.7: Commercializing Innovative Products

Commercialization is the process or cycle of introducing a new product or production method into the market.

Learning Objective

Examine the three key aspects of the commercialization process and outline the four key questions that must be answered prior to the commercialization of a new and innovative product

Key Points

- The actual launch of a new product is the final stage of new product development. This is when the most money is spent for advertising, sales promotion, and other marketing efforts.

- It is important to emphasize that the commercialization strategy and feasibility should have been considered and approved long before the actual execution of commercialization – as the time, efforts and development costs have already largely been incurred.

- Organizations must consider who they are selling to and where they are selling when determining the most effective process for commercialization.

- The primary target consumer group includes innovators, early adopters, heavy users, and opinion leaders. Their buy-in will ensure adoption by other consumers in the marketplace during the product growth period.

Key Terms

- early adopter

-

A person who begins using a product or service at or around the time it becomes available.

- commercialization

-

The act of positioning a product to make a profit.

Commercialization is often confused with sales, marketing, or business development. In the context of innovation, commercialization is the process of introducing a new product or service to the public market. Innovations are defined as new products or services that improve upon their predecessors, and the process of integrating them into the current market is a critical component of successfully bringing them to market. Great innovations are not always brought to market due to a lack of feasibility or poor planning. Long-term planning is crucial in the commercialization process because this is when the most money will be spent—on advertising, sales promotions, and other marketing efforts after the launch of a new product.

Product innovation approach

Innovation involves continuous improvement throughout phases of a development program. Phases can be iterative and recursive (meaning that they do not proceed linearly from one to the next; rather, earlier phases can be returned to for further improvement as needed). Such phases include market analysis and consumer research, which progress to design and prototyping, after which follow naming and packaging design and ultimately retail and production support.

The Commercialization Process

The commercialization process has three key aspects:

- Carefully select, based upon comprehensive market research, which products can be sustained financially in which markets for long-term success.

- Planning for various phases and/or stages in the commercialization process is key. Consider geographic distribution, different demographics, etc.

- Finally, identify and involve key stakeholders early, including consumers.

Key Strategic Questions

When bringing a product to market, a number of key strategic questions need to be answered satisfactorily long before substantial costs are incurred for commercialization. These questions are simple to ask but complex to answer, and business analysts and market researchers will spend a considerable amount of time approaching them via research models and careful financial consideration.

- When: The company has to time introducing the product perfectly. If there is a risk of cannibalizing the sales of the company’s other products, if the product could benefit from further development, or if the economy is forecasted to improve in the near future, the product’s launch should be delayed. Similarly, many items are seasonal (e.g., fashion) and so should be timed appropriately to maximize revenue.

- Where: The company has to decide where to launch its products. This can be in a single location, in one or several larger regions, or in a national or international market. This decision will be strongly influenced by the company’s resources; larger companies can reach broader geographic audiences. It is important to keep in mind where the early adopters will be and where competitive gaps may exist. In the global marketplace, this question is increasingly complex.

- To whom: The primary target consumer group will have been identified earlier through research and test marketing. This primary consumer group will include innovators, early adopters, heavy users, and opinion leaders. Their buy-in will ensure adoption by other consumers in the marketplace during the product growth period.

- How: The company has to decide on an action plan for introducing the product by implementing these decisions. It has to develop a viable marketing mix and create a respective marketing budget.

While these questions are key considerations in the commercialization process, remember that they should have been answered long before the commercialization stage. After all, if the need is not sufficiently widespread or the market not sufficiently developed, there is little reason to have pursued a given innovation in the first place.

4.3.8: Fostering Innovation

Offering employees challenges, freedom, resources, encouragement, and support can help them to innovate.

Learning Objective

Outline how to encourage creativity, participation and innovation through effective management

Key Points

- People perform best when they are driven by inspiration and are encouraged to push their boundaries and think outside the box.

- Teamwork enhances people’s strengths and lessens their individual weaknesses.

- One of the most powerful tools for promoting employee creativity and innovation is recognition.

- Ultimately, in developing a culture of innovation you want employees to feel comfortable experimenting and offering suggestions without fear of criticism or punishment for mistakes.

Key Terms

- creativity

-

The quality or ability to create or invent something.

- innovation

-

A change in customs; something new and contrary to established customs, manners, or rites.

Strategies capable of producing innovation require resources and energy; it is therefore necessary to discuss in your business plan the organizational structures and practices you will put in place to encourage and support innovation. Amabile (1998) points to six general categories of effective management practices that create a learning culture within an organization:

- Providing employees with a challenge

- Providing freedom to innovate

- Providing the resources needed to create new ideas/products

- Providing diversity of perspectives and backgrounds within groups

- Providing supervisor encouragement

- Providing organizational support

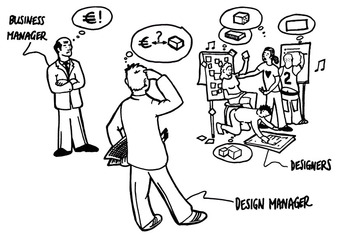

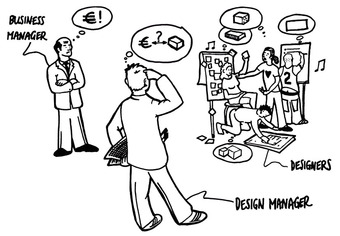

Innovation

Cartoon shows the challenge of translating innovation (designers) to economic success.

Create a Culture of Innovation

You will likely find that you need to generate hundreds of ideas to find ten good ones that will create value for your organization. This is part of the creative brainstorming process, and it should be encouraged. It should be the responsibility of every individual in the organization to come up with ideas, not just the founder or key staff. Here are some suggestions to encourage the flow of ideas.

Encourage Creativity

Encouraging creativity helps keep staff happy. If they think something is important and has the potential to create a financial payoff for the company, let them follow their idea. People perform best when they are driven by inspiration and encouraged to push their boundaries and think outside the box. But employees cannot do this when they are being micromanaged. Employees need to feel independent enough to own their innovative thinking and to pursue the ideas they are passionate about. In fact, if management effectively fosters a creative and open environment, innovation will happen naturally.

Encourage Participation

Teamwork enhances people’s strengths and mitigates their individual weaknesses. Effective teamwork also promotes the awareness that it is in everyone’s best interests to keep the business growing and improving. Creating a participation-based environment means creating smart teams, encouraging open dialogue, and minimizing authority. Criticism is productive and should be encouraged, but it must be used constructively.

Provide Recognition and Rewards

One of the most powerful tools for promoting employee creativity and innovation is recognition. People want to be recognized and rewarded for their ideas and initiatives, and it is a practice that can have tremendous payoff for the organization. Sometimes the recognition required may be as simple as mentioning a person’s effort in a newsletter. If a staff member comes up with a really creative idea, mention them in the company newsletter or on the news board even if their idea can’t be implemented immediately. Make it clear that compensation and promotions are tied to innovative thinking.

Enable Employee Innovation

You may have an innovative culture in your organization, but you also need to familiarize staff with some of the hallmarks of continuing innovation. For example, you could educate employees at regular training sessions on topics such as creativity, entrepreneurship, and teamwork. Each session might conclude with the assignment of an exercise to be performed over the next few working weeks that will consolidate lessons learned. Your aim here is to give employees a taste of innovation so they will embrace the process.

Other Motivators

- Profit-sharing and bonuses

- Days off

- Extra vacation time

Encourage employees to take advantage of coffee breaks, lunch breaks, and taxi rides. Often great ideas that can lead to innovation will happen outside the places where we expect them to happen. If it’s hard to get staff together for common informal breaks, consider taking them out for an informal meal where you can encourage creative discussion about work. Also be sure to encourage laughter at meetings because laughter is an effective measure of how comfortable people feel about expressing themselves.

4.4: Technology and Innovation

4.4.1: Technology as a Driver and Enabler of Innovation

Technology is a powerful driver of both the evolution and proliferation of innovation.

Learning Objective

Examine the role of technology as a driver of competitive advantage and innovation in the business framework

Key Points

- Innovation is a primary source of competitive advantage for companies in essentially all industries and environments and drives efficiency, productivity, and differentiation to fill a higher variety of needs.

- Technology builds upon itself, enabling innovative approaches within the evolution of technology.

- Technological hubs such as California’s Silicon Valley provide powerful resources that entrepreneurs and businesses can leverage in pursuing innovation.

- Technological advances, particularly in communication and transportation, further innovation.

- India, China, and the United States are all strong representations of how embracing technology leads to innovation, which in turn leads to economic growth.

Key Terms

- Scalable

-

Able to change in size or to scale up.

- innovation

-

The introduction of something new; the development of an original idea.

- proliferate

-

To increase in number or spread rapidly.

Innovation is a primary source of competitive advantage for companies in essentially all industries and environments, and drives forward efficiency, higher productivity, and differentiation to fill a wide variety of needs. One particular perspective on economics isolates innovation as a core driving force, alongside knowledge, technology, and entrepreneurship. This theory of innovation economics notes that the neoclassical approach (monetary accumulation driving growth) overlooks the critical aspect of the appropriate knowledge and technological capabilities.

Scaling Technology

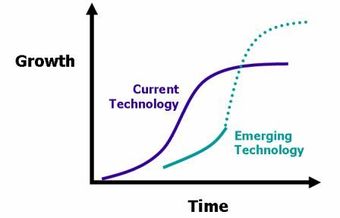

Technology in particular is a powerful driving force in innovative capacity, particularly as it pertains to both the evolution of innovations and the way they proliferate. Technology is innately scalable, demonstrating a consistent trend toward new innovations as a result of improving upon current ones. Product life cycles shows how economic returns go through a steep exponential growth phase and an eventual evening out, which motivates businesses to leverage technology to produce new innovations.

Technology Hubs

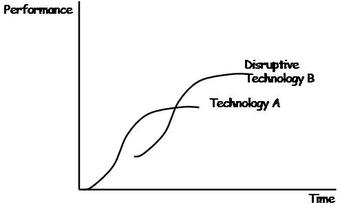

Technological Innovation Chart

This chart demonstrates the pattern of innovation over time. Note the overlapping trajectories of technologies: one product may dominate the market and grow at a high rate; the next (“emerging”) product may start low while the other product is dominant but in turn grow to dominate the market even more thoroughly than the first, as technology and production are refined and improved.

The proliferation of innovation pertains to two important factors of technology driving innovation: the creation of geographic hubs for technology and empowerment of knowledge exchange through communication and transportation. Places like California’s Silicon Valleya and Baden-Wurttenberg, Germany are strong examples of the value of technological hubs. The close proximity of various resources and collaborators in each hub stimulates a higher degree of innovative capacity.

Communication and cumulative knowledge in these technology hubs allows for these innovations to spread via technology to be implemented across the globe with relative immediacy. This spread of ideas can be built upon quickly and universally, creating the ability for innovation to be further expanded upon by different parties across the globe. Collaboration on a global scale as a result of technological progress has allowed for exponential levels of innovation.

Correlations Between Technology, Innovation, and Growth

Empirical evidence generates a positive correlation between technological innovation and economic performance. Between 1981 and 2004, India and China, developed a National Innovation System designed to invest heavily in R&D with a particular focus on patents and high-tech and service exports. During this timeframe, both countries experienced extremely high levels of GDP growth by linking the science sector with the business sector, importing technology, and creating incentives for innovation.

Additionally, the Council of Foreign Relations asserted that the U.S.’ s large share of the global market in the 1970s was likely a result of its aggressive investment in new technologies. These technological innovations generated are hypothesized to be a central driving force in the steady economic expansion of the U.S., allowing it to maintain it’s place as the world’s largest economy.

4.4.2: The Technology Life Cycle

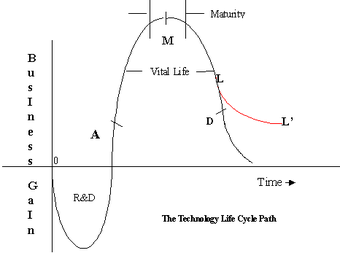

The technology life cycle describes the costs and profits of a product from technological development to market maturity to decline.

Learning Objective

Categorize the four distinct stages in the technology life cycle and apply the five demographic consumer groups in the context of these stages

Key Points

- The technology life cycle seeks to predict the adoption, acceptance, and eventual decline of new technological innovations.

- Understanding and effectively estimating technology life cycle allows for a more accurate reading of whether and when research and development costs will be offset by profits.

- The technology life cycle has four distinct stages: research and development, ascent, maturity, and decline.

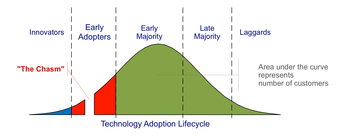

- The adoption of these technologies also has a life cycle with five chronological demographics: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards.

- By leveraging these models, businesses and institutions can exercise some foresight in ascertaining return on investment as their technologies mature.

Key Terms

- demographic

-

A characteristic used to identify people within a statistical framework.

- competitive advantage

-

Something that places a company or a person above the competition.

- Foresight

-

The ability to accurately estimate future outcomes.

The technology life cycle (TLC) describes the costs and profits of a product from technological development phase to market maturity to eventual decline. Research and development (R&D) costs must be offset by profits once a product comes to market. Varying product lifespans mean that businesses must understand and accurately project returns on their R&D investments based on potential product longevity in the market.