6.1: The Indus River Valley Civilizations

6.1.1: The Indus River Valley Civilization

The Indus River Valley Civilization, located in modern Pakistan,

was one of the world’s three earliest widespread societies.

Learning Objective

Identify the importance of the discovery of the Indus River Valley Civilization

Key Points

-

The Indus Valley Civilization

(also known as the Harappan Civilization) was a Bronze Age society extending

from modern northeast Afghanistan to Pakistan and northwest India. - The civilization developed in

three phases: Early Harappan Phase (3300 BCE-2600 BCE), Mature Harappan Phase

(2600 BCE-1900 BCE), and Late Harappan Phase (1900 BCE-1300 BCE). - Inhabitants of the ancient Indus

River valley developed new techniques in handicraft, including Carnelian

products and seal

carving, and metallurgy with

copper, bronze, lead, and tin. -

Sir John Hubert Marshall led an

excavation campaign in 1921-1922, during which he discovered the ruins of the

city of Harappa. By 1931, the Mohenjo-daro site had been mostly excavated by

Marshall and Sir Mortimer Wheeler. By 1999, over 1,056 cities and settlements of

the Indus Civilization were located.

Key Terms

- seal

-

An emblem used as

a means of authentication. Seal can refer to an impression in paper, wax, clay, or other medium. It can also refer to the device used. - metallurgy

-

The scientific and mechanical technique of working with bronze. copper, and tin.

The Indus Valley Civilization existed through its

early years of 3300-1300 BCE, and its mature period of

2600-1900 BCE. The area of this civilization extended along the Indus River

from what today is northeast Afghanistan, into Pakistan and northwest India. The

Indus Civilization was the most widespread of the three early civilizations of

the ancient world, along with Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Harappa and Mohenjo-daro were thought to be the two great

cities of the Indus Valley Civilization, emerging around 2600 BCE along the

Indus River Valley in the Sindh and Punjab provinces of Pakistan. Their discovery

and excavation in the 19th and 20th centuries provided important archaeological

data about ancient cultures.

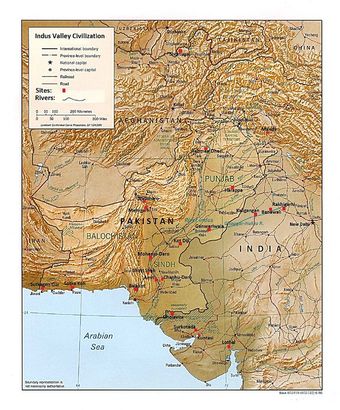

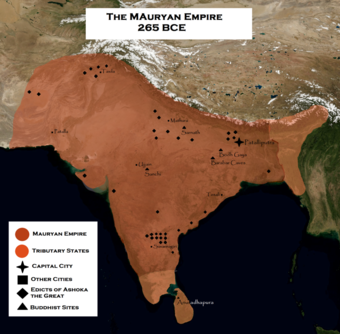

Map of the Indus Valley Civilization

The major sites of the Indus Valley Civilization.

Indus Valley Civilization

The

Indus Valley Civilization was one

of the three “Ancient East” societies that are considered to be the cradles of civilization

of the old world of man, and are among the most widespread; the other two “Ancient East” societies are Mesopotamia and Pharonic Egypt. The lifespan of

the Indus Valley Civilization is often separated into three phases: Early Harappan Phase

(3300-2600 BCE), Mature Harappan Phase (2600-1900 BCE) and Late Harappan Phase

(1900-1300 BCE).

At its peak, the Indus Valley

Civilization may had a population of over five million people. It is considered a Bronze

Age society, and inhabitants of the ancient Indus River Valley developed new

techniques in metallurgy—the science of working with copper, bronze, lead, and

tin. They also performed intricate handicraft, especially using products made

of the semi-precious gemstone Carnelian, as well as seal carving—

the cutting

of patterns into the bottom face of a seal used for stamping. The Indus cities

are noted for their urban planning, baked brick houses, elaborate

drainage systems, water supply systems, and clusters of large, non-residential

buildings.

The

Indus Valley Civilization is also known as the Harappan Civilization, after

Harappa, the first of its sites to be excavated in the 1920s, in what was then

the Punjab province of British India and is now in Pakistan. The discoveries of

Harappa, and the site of its fellow Indus city Mohenjo-daro, were the

culmination of work beginning in 1861 with the founding of the Archaeological

Survey of India in the British Raj, the common name for British imperial rule

over the Indian subcontinent from 1858 through 1947.

Harappa

and Mohenjo-daro

Harappa

was a fortified city in modern-day Pakistan that is believed to have been home

to as many as 23,500 residents living in sculpted houses with flat roofs made

of red sand and clay. The city spread over 150 hectares (370 acres) and had

fortified administrative and religious centers of the same type used in Mohenjo-daro.

The modern village of Harappa, used as a railway station during the Raj, is six

kilometers (3.7 miles) from the ancient city site, which suffered heavy damage

during the British period of rule.

Mohenjo-daro

is thought to have been built in the 26th century BCE and became not only the

largest city of the Indus Valley Civilization but one of the world’s earliest,

major urban centers. Located west of the Indus River in the Larkana District,

Mohenjo-daro was one of the most sophisticated cities of the period, with

sophisticated engineering and urban planning. Cock-fighting was thought to have

religious and ritual significance, with domesticated chickens bred for religion

rather than food (although the city may have been a point of origin for the

worldwide domestication of chickens). Mohenjo-daro was abandoned around 1900 BCE

when the Indus Civilization went into sudden decline.

The

ruins of Harappa were first described in 1842 by Charles Masson in his book, Narrative of Various Journeys in Balochistan,

Afghanistan, the Panjab, & Kalât. In 1856, British engineers John and

William Brunton were laying the East Indian Railway Company line connecting the

cities of Karachi and Lahore, when their crew discovered hard, well-burnt bricks

in the area and used them for ballast for the railroad track,

unwittingly dismantling the ruins of the ancient city of Brahminabad.

Excavations

In 1912, John Faithfull Fleet, an English civil servant working with the

Indian Civil Services, discovered several Harappan seals.

This prompted an excavation campaign from 1921-1922 by Sir John Hubert Marshall, Director-General

of the Archaeological Survey of India, which resulted in the

discovery of Harappa. By 1931, much of

Mohenjo-Daro had been excavated, while the next director of the Archaeological

Survey of India, Sir Mortimer Wheeler, led additional excavations.

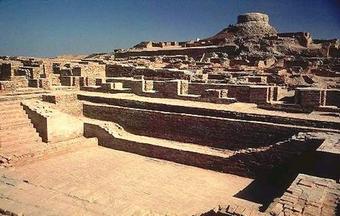

Excavated Ruins of Mohenjo-daro

The Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro, a city in the Indus River Valley Civilization.

The Partition of India, in 1947, divided the country to create the new nation

of Pakistan. The bulk of the archaeological finds that followed were inherited by Pakistan.

By 1999, over 1,056 cities and settlements had been found, of which 96 have

been excavated.

6.1.2: Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus River Valley Civilization (IVC) contained urban centers with

well-conceived and organized infrastructure, architecture, and systems of governance.

Learning Objective

Explain the significance of the urban centers in the IVC

Key Points

-

The Indus Valley Civilization

contained more than 1,000 cities and settlements. -

These cities contained

well-organized wastewater drainage systems, trash collection systems, and

possibly even public granaries and

baths. -

Although there were large walls

and citadels,

there is no evidence of monuments, palaces, or temples. -

The uniformity of Harappan

artifacts suggests some form of authority and governance to regulate seals,

weights, and bricks.

Key Terms

- urban planning

-

A technical and

political process concerned with the use of land and design of the urban

environment that guides and ensures the orderly development of settlements and

communities. - granaries

-

A storehouse or room in a barn for threshed grain or animal feed.

- citadels

-

A central area in a city that is heavily fortified.

- Harappa and Mohenjo-daro

-

Two of the major cities of the Indus Valley Civilization during the Bronze Age.

By

2600 BCE, the small Early Harappan communities had become

large urban centers. These cities include Harappa, Ganeriwala, and Mohenjo-daro

in modern-day Pakistan, and Dholavira, Kalibangan, Rakhigarhi, Rupar, and Lothal

in modern-day India. In total, more than 1,052 cities and settlements have been

found, mainly in the general region of the Indus River and its tributaries. The

population of the Indus Valley Civilization may have once been as large as five million.

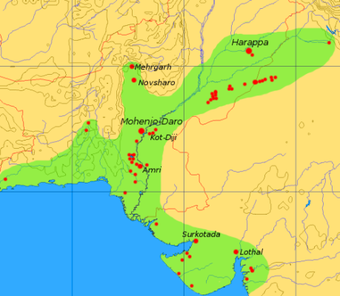

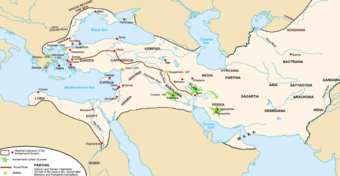

Indus Valley Civilization Sites

This map shows a cluster of Indus Valley Civilization cities and excavation sites along the course of the Indus River in Pakistan.

The

remains of the Indus Valley Civilization cities indicate remarkable organization; there were well-ordered wastewater drainage and trash collection systems, and

possibly even public granaries and baths. Most city-dwellers were artisans and merchants grouped together in

distinct neighborhoods. The quality of urban planning suggests efficient municipal

governments that placed a high priority on hygiene or religious ritual.

Infrastructure

Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and the recently, partially-excavated Rakhigarhi demonstrate the

world’s first known urban sanitation systems. The ancient Indus systems of

sewerage and drainage developed and used in cities throughout the Indus region

were far more advanced than any found in contemporary urban sites in the Middle

East, and even more efficient than those in many areas of Pakistan and India

today. Individual homes drew water from wells, while waste water was directed

to covered drains on the main streets. Houses opened only to inner courtyards

and smaller lanes, and even the smallest homes on the city outskirts were

believed to have been connected to the system, further supporting the

conclusion that cleanliness was a matter of great importance.

Architecture

Harappans

demonstrated advanced architecture with dockyards, granaries, warehouses, brick

platforms, and protective walls. These massive walls likely protected the

Harappans from floods and may have dissuaded military conflicts. Unlike

Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, the inhabitants of the Indus Valley Civilization

did not build large, monumental structures. There is no conclusive evidence of

palaces or temples (or even of kings, armies, or priests), and the largest

structures may be granaries. The city of Mohenjo-daro contains the “Great

Bath,” which may have been a large, public bathing and social area.

Sokhta Koh

Sokhta Koh, a Harappan

coastal settlement near Pasni, Pakistan, is depicted in a computer

reconstruction. Sokhta Koh means “burnt hill,” and corresponds to the browned-out

earth due to extensive firing of pottery in open pit ovens.

Authority

and Governance

Archaeological

records provide no immediate answers regarding a center of authority, or depictions

of people in power in Harappan society. The extraordinary uniformity of

Harappan artifacts is evident in pottery, seals, weights, and bricks with

standardized sizes and weights, suggesting some form of authority and

governance.

Over time, three major theories have developed concerning Harappan governance

or system of rule. The first is that there was a single state encompassing all

the communities of the civilization, given the similarity in artifacts, the

evidence of planned settlements, the standardized ratio of brick size, and the apparent

establishment of settlements near sources of raw material. The second theory posits

that there was no single ruler, but a number of them representing each of the urban

centers, including Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, and other communities. Finally, experts

have theorized that the Indus Valley Civilization had no rulers as we understand

them, with everyone enjoying equal status.

6.1.3: Harappan Culture

The Indus River Valley Civilization, also known as Harappan, included

its own advanced technology, economy, and culture.

Learning Objective

Identify how artifacts and ruins provided insight into the IRV’s technology, economy, and culture

Key Points

- The Indus River Valley Civilization,

also known as Harappan civilization, developed the first accurate system of

standardized weights and measures, some as accurate as to 1.6 mm. -

Harappans created sculpture, seals,

pottery, and jewelry from materials, such as terracotta, metal, and stone. - Evidence shows Harappans participated

in a vast maritime trade network extending from Central Asia to modern-day

Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, and Syria. - The Indus

Script remains indecipherable without any comparable

symbols, and is thought to have evolved independently of the writing in

Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt.

Key Terms

- steatite

-

Also known as Soapstone, steatite is a talc-schist, which is a type of metamorphic rock. It is very soft and has been a medium for carving for thousands of years.

- Indus Script

-

Symbols produced by the ancient Indus Valley Civilization.

- chalcolithic period

-

A period also

known as the Copper Age, which lasted from 4300-3200 BCE.

The Indus

Valley Civilization is the earliest known culture of the Indian subcontinent of

the kind now called “urban” (or centered on large municipalities), and the largest

of the four ancient civilizations, which also included Egypt, Mesopotamia, and

China. The society of the Indus River Valley has been dated from the Bronze Age,

the time period from approximately 3300-1300 BCE. It was located in modern-day India and Pakistan, and covered an area as large as Western

Europe.

Harappa and Mohenjo-daro were the two great cities of the Indus Valley

Civilization, emerging around 2600 BCE along the Indus River Valley in the

Sindh and Punjab provinces of Pakistan. Their discovery and excavation in the

19th and 20th centuries provided important archaeological data regarding the

civilization’s technology, art, trade, transportation, writing, and

religion.

Technology

The

people of the Indus Valley, also known as Harappan (Harappa was the first

city in the region found by archaeologists), achieved many notable advances in technology,

including great accuracy in their systems and tools for measuring length and

mass.

Harappans

were among the first to develop a system of uniform weights and measures that conformed

to a successive scale. The smallest division, approximately 1.6 mm, was marked

on an ivory scale found in Lothal, a prominent Indus Valley city in the modern Indian

state of Gujarat. It stands as the smallest division ever recorded on a Bronze

Age scale. Another indication of an advanced measurement system is the fact that

the bricks used to build Indus cities were uniform in size.

Harappans

demonstrated advanced architecture with dockyards, granaries, warehouses, brick

platforms, and protective walls. The ancient Indus systems of sewerage and

drainage developed and used in cities throughout the region were far more

advanced than any found in contemporary urban sites in the Middle East, and even

more efficient than those in many areas of Pakistan and India today.

Harappans

were thought to have been proficient in seal carving, the cutting of patterns

into the bottom face of a seal, and used distinctive seals for the

identification of property and to stamp clay on trade goods. Seals have been

one of the most commonly discovered artifacts in Indus Valley cities, decorated

with animal figures, such as elephants, tigers, and water buffalos.

Harappans also

developed new techniques in metallurgy—the science of working with copper, bronze,

lead, and tin—and performed intricate handicraft using products made of the

semi-precious gemstone, Carnelian.

Art

Indus

Valley excavation sites have revealed a number of distinct examples of the

culture’s art, including sculptures, seals, pottery, gold jewelry, and

anatomically detailed figurines in terracotta, bronze, and steatite—more commonly known as Soapstone.

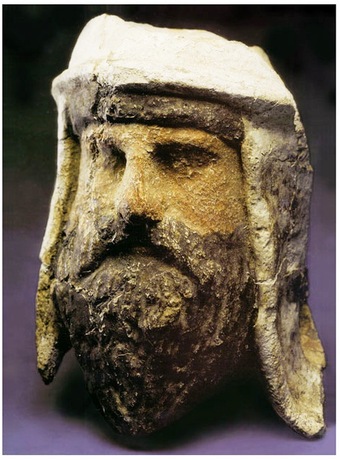

Among

the various gold, terracotta, and stone figurines found, a figure of a “Priest-King” displayed

a beard and patterned robe. Another figurine in bronze, known as the “Dancing

Girl,” is only 11 cm. high and shows a female figure in a pose that suggests the

presence of some choreographed dance form enjoyed by members of the

civilization. Terracotta works also included cows, bears, monkeys, and dogs. In

addition to figurines, the Indus River Valley people are believed to have created

necklaces, bangles, and other ornaments.

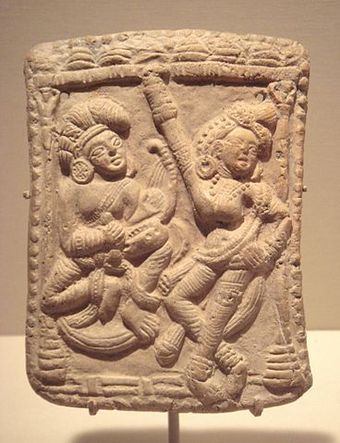

Miniature Votive Images or Toy Models from Harappa, c. 2500 BCE

The Indus River Valley Civilization created figurines from terracotta, as well as bronze and steatite. It is still unknown whether these figurines have religious significance.

Trade and

Transportation

The

civilization’s economy appears to have depended significantly on trade, which

was facilitated by major advances in transport technology. The Harappan

Civilization may have been the first to use wheeled transport, in the form of

bullock carts that are identical to those seen throughout South Asia today. It

also appears they built boats and watercraft—a claim supported by

archaeological discoveries of a massive, dredged canal, and what is regarded as

a docking facility at the coastal city of Lothal.

The docks and canal in the ancient city of Lothal, located in modern India

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Indus River Valley Civilization constructed boats and may have participated in an extensive maritime trade network.

Trade

focused on importing raw materials to be used in Harappan city workshops, including minerals from Iran and Afghanistan, lead and copper from other parts

of India, jade from China, and cedar wood floated down rivers from the

Himalayas and Kashmir. Other trade goods included terracotta pots, gold,

silver, metals, beads, flints for making tools, seashells, pearls, and colored gem

stones, such as lapis lazuli and turquoise.

There

was an extensive maritime trade network operating between the Harappan and Mesopotamian

civilizations. Harappan seals and jewelry have been found at archaeological sites

in regions of Mesopotamia, which includes most of modern-day Iraq, Kuwait, and

parts of Syria. Long-distance sea trade over bodies of water, such as the

Arabian Sea, Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, may have become feasible with the

development of plank watercraft that was equipped with a single central mast supporting

a sail of woven rushes or cloth.

During

4300-3200 BCE of the Chalcolithic period,

also known as the Copper

Age, the Indus Valley Civilization area shows ceramic similarities with

southern Turkmenistan and northern Iran. During the Early Harappan period

(about 3200-2600 BCE), cultural similarities in pottery, seals, figurines, and

ornaments document caravan trade with Central Asia and the Iranian plateau.

Writing

Harappans

are believed to have used Indus Script, a language consisting of symbols. A

collection of written texts on clay and stone tablets unearthed at Harappa,

which have been carbon dated 3300-3200 BCE, contain trident-shaped, plant-like markings. This Indus Script suggests that writing developed

independently in the Indus River Valley Civilization from the script employed

in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt.

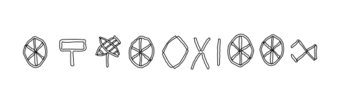

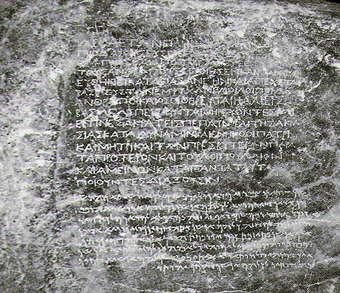

Indus Script

These ten Indus Script symbols were found on a “sign board” in the ancient city of Dholavira.

As

many as 600 distinct Indus symbols have been found on seals, small tablets,

ceramic pots, and more than a dozen other materials. Typical Indus inscriptions

are no more than four or five characters in length, most of which are very

small. The longest on a single surface, which is less than 1 inch (or 2.54 cm.) square, is 17 signs long. The characters are largely pictorial, but include

many abstract signs that do not appear to have changed over time.

The inscriptions are thought to have been primarily written from right

to left, but it is unclear whether this script constitutes a complete language.

Without a “Rosetta Stone” to use as a comparison with other writing systems, the

symbols have remained indecipherable to linguists and archaeologists.

Religion

The

Harappan religion remains a topic of speculation. It has been widely suggested

that the Harappans worshipped a mother goddess who symbolized fertility. In

contrast to Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations, the Indus Valley

Civilization seems to have lacked any temples or palaces that would give clear

evidence of religious rites or specific deities. Some Indus Valley seals show a

swastika symbol, which was included in later Indian religions including

Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.

Many

Indus Valley seals also include the forms of animals, with some depicting them

being carried in processions, while others showing chimeric creations, leading

scholars to speculate about the role of animals in Indus Valley religions. One

seal from Mohenjo-daro shows a half-human, half-buffalo monster attacking a

tiger. This may be a reference to the Sumerian myth of a monster created by Aruru,

the Sumerian earth and fertility goddess, to fight Gilgamesh, the hero of an ancient Mesopotamian

epic poem. This is a further suggestion of international trade in

Harappan culture.

The “Shiva Pashupati” seal

This seal was excavated in Mohenjo-daro and depicts a seated and possibly ithyphallic figure, surrounded by animals.

6.1.4: Disappearance of the Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilization declined around 1800 BCE due to climate

change and migration.

Learning Objective

Discuss the causes for the disappearance of the Indus Valley Civilization

Key Points

- One theory suggested that a nomadic, Indo-European tribe, called the Aryans, invaded and conquered the Indus Valley Civilization.

- Many scholars now believe the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilization was caused by climate change.

- The eastward shift of monsoons may have reduced the water supply, forcing the Harappans of the Indus River Valley to migrate and establish smaller villages and isolated farms.

- These small communities could not produce the agricultural surpluses needed to support cities, which where then abandoned.

Key Terms

- Indo-Aryan Migration theory

-

A theory suggesting the Harappan culture of the Indus River Valley was assimilated during a migration of the Aryan people into northwest India.

- monsoon

-

Seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation; usually winds that bring heavy rain once a year.

- Aryans

-

A nomadic, Indo-European tribe called the Aryans suddenly overwhelmed and conquered the Indus Valley Civilization.

The great

Indus Valley Civilization, located in modern-day India and Pakistan, began to

decline around 1800 BCE. The civilization eventually disappeared

along with its two great cities, Mohenjo-daro and Harappa. Harappa lends its name

to the Indus Valley people because it was the civilization’s first city to be

discovered by modern archaeologists.

Archaeological

evidence indicates that trade with Mesopotamia, located largely in modern Iraq, seemed

to have ended. The advanced drainage system and baths of the great cities were

built over or blocked. Writing began to disappear and the standardized weights

and measures used for trade and taxation fell out of use.

Scholars

have put forth differing theories to explain the disappearance of the Harappans,

including an Aryan Invasion and climate change marked by overwhelming monsoons.

The Aryan

Invasion Theory (c. 1800-1500 BC)

The Indus

Valley Civilization may have met its demise due to invasion. According to one

theory by British archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler, a nomadic, Indo-European

tribe, called the Aryans, suddenly overwhelmed and conquered the Indus River

Valley.

Wheeler,

who was Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India from 1944 to

1948, posited that many unburied corpses found in the top levels of the Mohenjo-daro

archaeological site were victims of war. The theory suggested that by using

horses and more advanced weapons against the peaceful Harappan people, the

Aryans may have easily defeated them.

Yet shortly

after Wheeler proposed his theory, other scholars dismissed it by explaining

that the skeletons were not victims of invasion massacres, but rather the

remains of hasty burials. Wheeler himself eventually admitted that the theory

could not be proven and the skeletons indicated only a final phase of human

occupation, with the decay of the city structures likely a result of it becoming

uninhabited.

Later

opponents of the invasion theory went so far as to state that adherents to the idea

put forth in the 1940s were subtly justifying the British government’s policy

of intrusion into, and subsequent colonial rule over, India.

Various

elements of the Indus Civilization are found in later cultures, suggesting the

civilization did not disappear suddenly due to an invasion. Many scholars came

to believe in an Indo-Aryan Migration theory stating that the Harappan culture

was assimilated during a migration of the Aryan people into northwest India.

Aryans in India

An early 20th-century depiction of Aryan people settling in agricultural villages in India.

The Climate

Change Theory (c. 1800-1500 BC)

Other

scholarship suggests the collapse of Harappan society resulted from climate

change. Some experts believe the drying of the Saraswati River, which began

around 1900 BCE, was the main cause for climate change, while others conclude

that a great flood struck the area.

Any

major environmental change, such as deforestation, flooding or droughts due to

a river changing course, could have had disastrous effects on Harappan society, such

as crop failures, starvation, and disease. Skeletal evidence suggests many

people died from malaria, which is most often spread by mosquitoes. This also

would have caused a breakdown in the economy and civic order within the urban

areas.

Another disastrous change in the Harappan climate might have been

eastward-moving monsoons, or winds that bring heavy rains. Monsoons can be both

helpful and detrimental to a climate, depending on whether they support or

destroy vegetation and agriculture. The monsoons that came to the Indus River

Valley aided the growth of agricultural surpluses, which supported the

development of cities, such as Harappa. The population came to rely on seasonal

monsoons rather than irrigation, and as the monsoons

shifted eastward, the water supply would have dried up.

Ruins of the city of Lothal

Archaeological evidence

shows that the site, which had been a major city before the downfall of the

Indus Valley Civilization, continued to be inhabited by a much smaller

population after the collapse. The few people who remained in Lothal did not repair

the city, but lived in poorly-built houses and reed huts instead.

By

1800 BCE, the Indus Valley climate grew cooler and drier, and a tectonic event

may have diverted the Ghaggar Hakra river system toward the Ganges Plain. The Harappans may have migrated

toward the Ganges basin in the east, where they established villages

and isolated farms.

These small communities could not produce the same agricultural

surpluses to support large cities. With the reduced production of goods, there

was a decline in trade with Egypt and Mesopotamia. By around 1700 BCE, most of

the Indus Valley Civilization cities had been abandoned.

6.2: Indo-European Civilizations

6.2.1: The Indo-Aryan Migration and the Vedic Period

Different theories explain the Vedic Period, c. 1200 BCE, when Indo-Aryan

people on the Indian subcontinent migrated to the Ganges Plain.

Learning Objective

Describe the defining characteristics of the Vedic Period and the cultural consequenes of the Indo-Aryan Migration

Key Points

-

The Indo-Aryans were

part of an expansion into the Indus Valley and Ganges

Plain from

1800-1500 BCE. This is explained through Indo-Aryan Migration and Kurgan theories. - The Indo-Aryans continued to

settle the Ganges Plain, bringing their distinct religious beliefs and

practices. - The Vedic Period (c. 1750-500 BCE)

is named for the

Vedas, the oldest scriptures in Hinduism, which were composed during this period. The period can be divided into the Early Vedic (1750-1000 BCE) and Later Vedic

(1000-500 BCE) periods.

Key Terms

- Rig-Veda

-

A sacred

Indo-Aryan collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns. It is counted among the four canonical

sacred texts of Hinduism, known as the Vedas. - the Vedas

-

The oldest

scriptures of Hinduism composed in Vedic Sanskrit, and originating in ancient

India during the Vedic Period (c. 1750-500 BCE). - Ganges Plain

-

A large, fertile

plain encompassing most of northern and eastern India, where the Indo-Aryans

migrated.

Scholars

debate the origin of Indo-Aryan peoples in northern India. Many have rejected

the claim of Indo-Aryan origin outside of India entirely, claiming the

Indo-Aryan people and languages originated in India. Other origin hypotheses include

an Indo-Aryan Migration in the period 1800-1500 BCE, and a fusion

of the nomadic people known as Kurgans. Most history of this period is derived

from the Vedas, the oldest scriptures in Hinduism, which help chart the

timeline of an era from 1750-500 BCE, known as the Vedic Period.

The

Indo-Aryan Migration (1800-1500 BCE)

Foreigners

from the north are believed to have migrated to India and settled in the Indus

Valley and Ganges Plain from 1800-1500 BCE. The most prominent of these groups

spoke Indo-European languages and were called Aryans, or “noble

people” in the Sanskrit language. These Indo-Aryans were a branch of the

Indo-Iranians, who originated in present-day northern Afghanistan. By 1500 BCE,

the Indo-Aryans had created small herding and agricultural communities across

northern India.

These

migrations took place over several centuries and likely did not involve an

invasion, as hypothesized by British archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler in the

mid-1940s. Wheeler, who was Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of

India from 1944 to 1948, suggested that a nomadic, Indo-European tribe, called

the Aryans, suddenly overwhelmed and conquered the Indus River Valley. He based

his conclusions on the remains of unburied corpses found in the top levels of

the archaeological site of Mohenjo-daro, one of the great cities of the Indus

Valley Civilization, whom he said were victims of war. Yet shortly after

Wheeler proposed his theory, other scholars dismissed it by explaining that the

skeletons were not those of victims of invasion massacres, but rather the remains of

hasty burials. Wheeler himself eventually admitted that the theory could not be

proven.

The Kurgan

Hypothesis

The

Kurgan Hypothesis is the most widely accepted scenario of Indo-European

origins. It postulates that people of a so-called Kurgan Culture, a grouping of

the Yamna or Pit Grave culture and its predecessors, of the Pontic Steppe were the speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language. According to this theory, these

nomadic pastoralists expanded throughout

the Pontic-Caspian steppe and into Eastern Europe by early 3000 BCE. The Kurgan

people may have been mobile because of their domestication of horses and later use

of the chariot.

The Vedic

Period (c. 1750-500 BCE)

The

Vedic Period refers to the time in history from approximately 1750-500 BCE, during

which Indo-Aryans settled into northern India, bringing with them specific religious

traditions. Most history of this period is derived from the Vedas, the oldest

scriptures in the Hindu religion, which were composed by the Aryans in Sanskrit.

Vedic

Civilization is believed to have been centered in the northwestern parts of the

Indian subcontinent and spread around 1200 to the Ganges Plain, a 255-million

hectare area (630 million acres) of flat, fertile land named after the Ganges

River and covering most of what is now northern and eastern India, eastern

parts of Pakistan, and most of Bangladesh. Many scholars believe Vedic

Civilization was a composite of the Indo-Aryan and Harappan, or Indus Valley,

cultures.

The Ganges Plain (Indo-Gangetic Plain)

The Ganges Plain is supported by the Indus and Ganges river systems. The Indo-Aryans settled various parts of the plain during their migration and the Vedic Period.

Early

Vedic Period (c. 1750-1000 BCE)

The

Indo-Aryans in the Early Vedic Period, approximately 1750-1000 BCE, relied

heavily on a pastoral, semi-nomadic economy with limited agriculture. They

raised sheep, goats, and cattle, which became symbols of wealth.

The

Indo-Aryans also preserved collections of religious and literary works by memorizing

and reciting them, and handing them down from one generation to the next in their

sacred language, Sanskrit. The Rigveda, which was likely composed during

this time, contains several mythological and poetical accounts of the origins

of the world, hymns praising the gods, and ancient prayers for life and

prosperity.

Organized

into tribes, the Vedic Aryans regularly clashed over land and resources. The Rigveda describes the most notable of

these conflicts, the Battle of the Ten Kings, between the Bharatas tribe and a

confederation of ten competing tribes on the banks of what is now the Ravi River

in northwestern India and eastern Pakistan. Led by their king, Sudas, the

Bharatas claimed victory and merged with the defeated Purus tribe to form the

Kuru, a Vedic tribal union in northern India.

Later

Vedic Period (c. 1000-500 BCE)

After

the 12th century BCE, Vedic society transitioned from semi-nomadic to settled

agriculture. From approximately 1000-500 BCE, the development of iron axes and

ploughs enabled the Indo-Aryans to settle the thick forests on the western

Ganges Plain.

This agricultural expansion led to an increase in trade and competition

for resources, and many of the old tribes coalesced to form larger political

units. The Indo-Aryans cultivated wheat, rice and barley and implemented new

crafts, such as carpentry, leather work, tanning, pottery, jewelry crafting, textile

dying, and wine making.

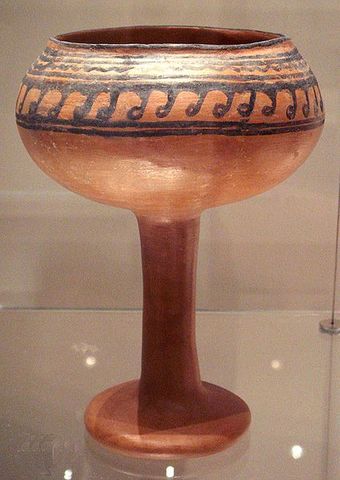

Ceramic goblet from Navdatoli, Malwa, c. 1300 BCE

As the Indo-Aryans developed an agricultural society during the Later Vedic Period (c. 1000-500), they further developed crafts, such as pottery.

Economic

exchanges were conducted through gift giving, particularly between kings and

priests, and barter using cattle as a unit of currency. While gold, silver,

bronze, copper, tin, and lead are mentioned in some hymns as trade items,

there is no indication of the use of coins.

The

invasion of Darius I (a Persian ruler of the vast Achaemenid Empire that stretched

into the Indus Valley) in the early 6th century BCE marked the beginning of

outside influence in Vedic society. This continued into what became the Indo-Greek

Kingdom, which covered various parts of South Asia and was centered mainly in modern

Afghanistan and Pakistan.

6.2.2: The Caste System

A caste system developed among Indo-Aryans of the Vedic Period,

splitting society into four major groups.

Learning Objective

Explain the history of the caste system

Key Points

-

The institution of the caste system,

influenced by stories of the gods in the Rig-Veda epic,

assumed and reinforced the idea that lifestyles, occupations, ritual statuses,

and social statuses were inherited. - Aryan society

was patriarchal in the Vedic Period, with men in positions of authority and

power handed down only through the male line. - There were four classes in the

caste system: Brahmins (priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (kings, governors, and

warriors), Vaishyas (cattle herders, agriculturists, artisans,

and merchants), and Shudras (laborers and service providers). A fifth group, Untouchables,

was excluded from the caste system and historically performed the undesirable

work. -

The caste system may have been

more fluid in Aryan India than it is in modern-day India.

Key Terms

- jatis

-

The term used to

denote the thousands of clans, tribes, religions, communities and sub-communities

in India. - varnas

-

The four broad

ranks of the caste system in the Indo-Aryan culture, which included Brahmins

(priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (kings, governors and warriors), Vaishyas

(cattle herders, agriculturists, artisans, and merchants), and Shudras

(laborers and service providers).

Caste

systems through which social status was inherited developed independently in ancient

societies all over the world, including the Middle East, Asia, and Africa. The

caste system in ancient India was used to establish separate classes of inhabitants

based upon their social positions and employment functions in the community.

These roles and their importance, including the levels of power and significance

based on patriarchy, were influenced by stories of the gods in the Rig-Veda

epic.

Origins

The

caste system in India may have several origins, possibly starting with the

well-defined social orders of the Indo-Aryans in the Vedic Period, c. 1750-500

BCE. The Vedas were ancient scriptures, written

in the Sanskrit language, which contained hymns, philosophies, and rituals handed

down to the priests of the Vedic religion. One of these four sacred canonical

texts, the Rig-Veda, described the origins of the world and points to the gods

for the origin of the caste system.

The castes were a form of social stratification in Aryan India characterized

by the hereditary transmission of lifestyle, occupation, ritual status, and

social status. These social distinctions may have been more fluid in ancient

Aryan civilizations than in modern India, where castes still exist but sociologists

are observing inter-caste marriages and interactions becoming more fluid and

less rigid.

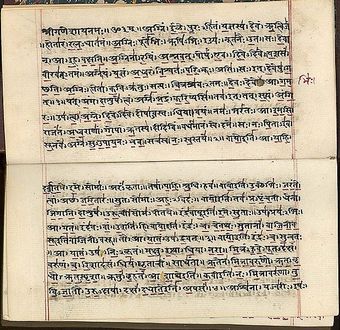

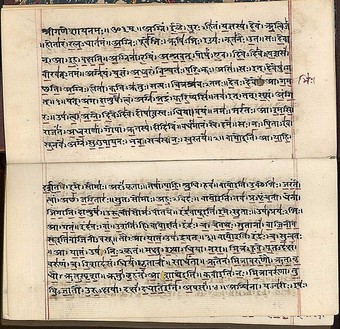

The Rig-Veda

A page of the Rig-Veda,

one of the four sacred Veda texts, which described the origins of the world and

the stories of the gods. The Rig-Veda influenced the development of the

patriarchal society and the caste systems in Aryan India.

Structure

The

classes, known as varnas, enforced

divisions in the populations that still affect this area of the world today. By

around 1000 BCE, the Indo-Aryans developed four main caste distinctions:

Brahamin, consisting of priests, scholars, and teachers; Kshatriyas, the kings,

governors, and warriors; Vaishyas, comprising agriculturists, artisans, and

merchants; and Sudras, the service providers and artisans who were originally

non-Aryans but were admitted to Vedic society.

Each

varna was divided into jatis, or sub-castes, which identified the

individual’s occupation and imposed marriage restrictions. Marriage was only

possible between members of the same jati or two that were very close. Both

varnas and jatis determined a person’s purity level. Members of higher varnas

or jatis had higher purity levels, and if contaminated by members of lower

social groups, even by touch, they would have to undergo extensive cleansing

rites.

Castes in India

A page from the manuscript Seventy-two Specimens of Castes in India, which consists of 72 full-color hand-painted images of men and women of the various castes and religious and ethnic groups found in Madura, India at that time. Each drawing was made on mica, a transparent, flaky mineral that splits into thin, transparent sheets. As indicated on the presentation page, the album was compiled by the Indian writing master at an English school established by American missionaries in Madura, and given to the Reverend William Twining. The manuscript shows Indian dress and jewelry adornment in the Madura region as they appeared before the onset of Western influences on South Asian dress and style. Each illustrated portrait is captioned in English and in Tamil, and the title page of the work includes English, Tamil, and Telugu.

As

the Aryans expanded their influence, newly conquered groups were assimilated

into society by forming a new group below the Sudras, outside the caste system.

These outcasts were called Untouchables, as they performed the least desirable

activities and jobs, such as dealing with dead bodies, cleaning toilets and

washrooms, and tanning and dyeing leather.

Development

of Patriarchy

Society

during the Vedic Period (c.1750-500 BCE) was patriarchal and patrilineal, meaning to trace ancestral

heritage through the male line. Marriage and childbearing were especially

important to maintain male lineage. The institution of marriage was important, and different types of marriages—monogamy, polygyny and polyandry—are

mentioned in the Rig Veda. All priests, warriors, and tribal chiefs were men, and

descent was always through the male line.

In

other parts of society, women had no public authority; they only were able to

influence affairs within their own homes. Women were to remain subject to the

guidance of males in their lives, beginning with their father, then husband, and

lastly their sons. Male gods were considered more important than female gods.

These distinct gender roles may have contributed to the social stratification

of the caste system.

Enduring

Influence

The

caste system that influenced the social structure of Aryan India has been

maintained to some degree into modern-day India. The caste system survived for

over two millennia, becoming one of the basic features of traditional Hindu

society. Although the Constitution of India, the supreme law document of the Republic

of India, formally abolished the caste system in 1950, some people maintain prejudices

against members of lower social classes.

Gandhi at Madras, 1933

Mahatma Gandhi visits Madras, now Chennai, during a tour of India in 1933. As leader of the Indian independence movement, Gandhi frequently spoke out against discrimination created by the caste system.

6.2.3: Sanskrit

Vedic Sanskrit evolved to Classical Sanskrit, which has

influenced modern Indian languages and is used in religious rites.

Learning Objective

Explain the importance of Sanskrit

Key Points

-

Sanskrit is originated as Vedic

Sanskrit as early as 1700-1200 BCE, and was orally preserved as a part of the

Vedic chanting tradition. - The scholar Panini standardized

Vedic Sanskrit into Classical Sanskrit when he defined the grammar, around 500

BCE. - Vedic Sanskrit is the language of the

Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism. - Knowledge of Sanskrit became a

marker of high social class during and after the Vedic Period.

Key Terms

- Hinduism

-

The dominant

religion of the modern Indian subcontinent, which makes use of Sanskrit in its

texts and practices. - Panini

-

The scholar who standardized the grammar of Vedic Sanskrit to create Classical Sanskrit.

Sanskrit

is the primary sacred language of Hinduism, and has been used as a

philosophical language in the religions of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. Sanskrit is a standardized

dialect of Old Indo-Aryan, originating as Vedic Sanskrit as early as 170001200

BCE.

One

of the oldest Indo-European languages for which substantial documentation

exists, Sanskrit is believed to have been the general language of the greater

Indian Subcontinent in ancient times. It is still used today in Hindu religious

rituals, Buddhist hymns and chants, and Jain texts.

Origins

Sanskrit

traces its linguistic ancestry to Proto-Indo-Iranian and ultimately to

Proto-Indo-European languages, meaning that it can be traced historically back

to the people who spoke Indo-Iranian, also called the Aryan languages, as well as the

Indo-European languages, a family of several hundred related languages and

dialects. Today, an estimated 46% of humans speak some form of Indo-European

language. The most widely-spoken Indo-European languages are English, Hindi, Bengali,

Punjabi, Spanish, Portuguese, and Russian, each with over 100 million speakers.

Sanskrit manuscript on palm-leaf, in Bihar or Nepal, 11th century

Sanskrit evolved from Proto-Indo-European languages and was used to write the Vedas, the Hindu religious texts compiled between 1500-500 BCE.

Vedic

Sanskrit is the language of the Vedas, the most ancient Hindu scripts, compiled c. 1500-500 BCE. The Vedas contain hymns, incantations called Samhitas, and

theological and philosophical guidance for priests of the Vedic religion. Believed

to be direct revelations to seers among the early Aryan people of India, the

four chief collections are the Rig Veda, Sam Veda, Yajur Vedia, and Atharva

Veda. (Depending on the source consulted, these are spelled, for example,

either Rig Veda or Rigveda.)

Vedic

Sanskrit was orally preserved as a part of the Vedic chanting tradition,

predating alphabetic writing in India by several centuries. Modern linguists

consider the metrical hymns of the Rigveda Samhita, the

most ancient layer

of text in the Vedas, to have been composed by many authors over several

centuries of oral tradition.

Sanskrit Literature

Sanskrit

Literature began with the spoken or sung literature of the Vedas from c. 1500

BCE, and continued with the oral tradition of the Sanskrit Epics of Iron Age

India, the period after the Bronze Age began, around 1200 BCE. At approximately

1000 BCE, Vedic Sanskrit began the transition from a first language to a second

language of religion and learning.

Around 500 BCE, the ancient scholar Panini standardized the grammar of

Vedic Sanskrit, including 3,959 rules of syntax, semantics, and morphology (the study of words and how they are formed and relate to each other). Panini’s Astadhyayi is the most important of the surviving

texts of Vyakarana, the linguistic

analysis of Sanskrit, consisting of eight chapters laying out his rules and their

sources. Through this standardization, Panini helped create what is now known

as Classical Sanskrit.

A 2004 Indian stamp honoring Panini, the great Sanskrit grammarian

The scholar Panini standardized the grammar of Vedic Sanskrit to create Classical Sanskrit. With this standardization, Sanskrit became a language of religion and learning.

The

classical period of Sanskrit literature dates to the Gupta period and the

successive pre-Islamic middle kingdoms of India, spanning approximately the 3rd

to 8th centuries CE. Hindu Puranas, a genre of Indian

literature that includes myths and legends, fall into the period of Classical Sanskrit.

Drama

as a distinct genre of Sanskrit literature emerged in the final centuries BCE, influenced

partly by Vedic mythology. Famous Sanskrit dramatists include Shudraka, Bhasa,

Asvaghosa, and Kalidasa; their numerous plays are still available, although

little is known about the authors themselves. Kalidasa’s play, Abhijnanasakuntalam, is generally

regarded as a masterpiece and was among the first Sanskrit works to be

translated into English, as well as numerous other languages.

Works

of Sanskrit literature, such as the Yoga-Sutras of Patanjali, which are still consulted

by practitioners of yoga today, and the Upanishads,

a series of sacred Hindu treatises, were translated into Arabic and Persian. Sanskrit

fairy tales and fables were characterized by ethical reflections and proverbial

philosophy, with a particular style making its way into Persian and Arabic

literature and exerting influence over such famed tales as One Thousand and One Nights, better known in English as Arabian Nights.

Poetry

was also a key feature of this period of the language. Kalidasa was the

foremost Classical Sanskrit poet, with a simple but beautiful style, while

later poetry shifted toward more intricate techniques including stanzas that

read the same backwards and forwards, words that could be split to produce

different meanings, and sophisticated metaphors.

Importance

Sanskrit

is vital to Indian culture because of its extensive use in religious

literature, primarily in Hinduism, and because most modern Indian languages

have been directly derived from, or strongly influenced by, Sanskrit.

Knowledge

of Sanskrit was a marker of social class and educational attainment in ancient

India, and it was taught mainly to members of the higher castes (social groups based on birth

and employment status). In the medieval era, Sanskrit continued to be spoken and

written, particularly by Brahmins (the name for Hindu priests of the highest

caste) for scholarly communication.

Today,

Sanskrit is still used on the Indian Subcontinent. More than 3,000 Sanskrit

works have been composed since India became independent in 1947, while more

than 90 weekly, biweekly, and quarterly publications are published in Sanskrit. Sudharma, a daily newspaper written in

Sanskrit, has been published in India since 1970. Sanskrit is used extensively

in the Carnatic and Hindustani branches of classical music, and it continues to

be used during worship in Hindu temples as well as in Buddhist and Jain

religious practices.

Sanskrit is a major feature of the academic linguistic field of

Indo-European studies, which focuses on both extinct and current Indo-European

languages, and can be studied in major universities around the world.

6.2.4: The Vedas

The Vedas are the oldest texts of the Hindu religion and contain

hymns, myths and rituals that still resonate in India today.

Key Points

-

The Vedas, meaning “knowledge,”

are the oldest texts of Hinduism. - They are derived from the ancient

Indo-Aryan culture of the Indian Subcontinent and began as an oral tradition

that was passed down through generations before finally being written in Vedic

Sanskrit between 1500 and 500 BCE (Before Common Era). - The Vedas are structured in four

different collections containing hymns, poems, prayers, and religious

instruction. - The Indian caste system is based

on a fable from the Vedas about the sacrifice of the deity Purusha.

Key Terms

- Rig Veda

-

The oldest and most important of the four Vedas.

- Caste System

-

An ancient social structure based upon one of the fables in the Vedas, castes persist in modern India.

- Vedas

-

The oldest scriptures of Hinduism, originally passed down orally but then written in Vedic Sanskrit between 1500 and 500 BCE.

- Hinduism

-

A major world religion that began on the Indian Subcontinent.

The

Indo-Aryan Vedas remain the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, which is considered

one of the oldest religions in the world. Vedic ritualism, a composite of ancient

Indo-Aryan and Harappan culture, contributed to the deities and traditions of

Hinduism over time. The Vedas are split into four major texts and contain

hymns, mythological accounts, poems, prayers, and formulas considered sacred to

the Vedic religion.

Structure

of the Vedas

Vedas,

meaning “knowledge,” were written in Vedic Sanskrit between 1500 and

500 BCE in the northwestern region the Indian Subcontinent. The Vedas were

transmitted orally during the course of numerous subsequent generations before

finally being archived in written form. Not much is known about the authors of

the Vedas, as the focus is placed on the ideas found in Vedic tradition rather

than those who originated the ideas. The oldest of the texts is the Rig Veda,

and while it is not possible to establish precise dates for each of the ancient

texts, it is believed the collection was completed by the end of the 2nd millennium

BCE (Before Common Era).

There

are four Indo-Aryan Vedas: the Rig Veda contains hymns about their mythology;

the Sama Veda consists mainly of hymns about religious rituals; the Yajur Veda

contains instructions for religious rituals; and the Atharva Veda consists of

spells against enemies, sorcerers, and diseases. (Depending on the source

consulted, these are spelled, for example, either Rig Veda or Rigveda.)

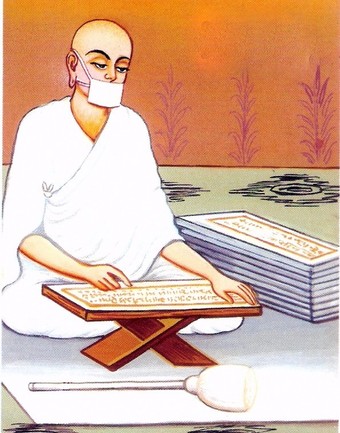

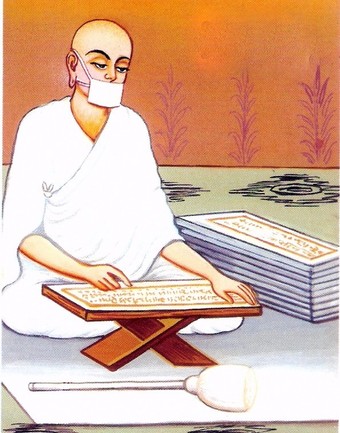

Rigveda Manuscript

A manuscript copy of the Rigveda, the oldest and most important of the four Vedas of the Vedic religion, from the early 19th century.

The

Rig Veda is the largest and considered the most important of the collection,

containing 1,028 hymns divided into 10 books called mandalas. The verses of the

Sam Veda are taken almost completely from the Rig Veda, but arranged

differently so they may be chanted. The Yajur Veda is divided into the White

and Black halves and contains prose commentaries on how religious and

sacrifices should be performed. The Atharva Veda includes charms and magic

incantations written in the style of folklore.

Each

Veda was further divided in two sections: the Brahmanas, instructions for

religious rituals, and the Samhitas, mantras or hymns in praise of various

deities. Modern linguists consider the metrical hymns of the Rigveda Samhita, the

most ancient layer

of text in the Vedas, to have been composed by many authors over several

centuries of oral tradition.

Although

the focus of the Vedas is on the message rather than the messengers, such as

Buddha or Jesus Christ in their respective religions, the Vedic religion still

held gods in high regard.

Vedic

Religion

The

Aryan pantheon of gods is described in great detail in the Rig Veda. However,

the religious practices and deities are not uniformly consistent in these

sacred texts, probably because the Aryans themselves were not a homogenous

group. While spreading through the Indian Subcontinent, it is probable that

their initial religious beliefs and practices were shaped by the absorption of

local religious traditions.

According

to the hymns of the Rig Veda, the most important deities were Agni, the god of

Fire, intermediary between the gods and humans; Indra, the god of Heavens and

War, protector of the Aryans against their enemies; Surya, the Sun god; Vayu,

the god of Wind; and Prthivi, the goddess of Earth.

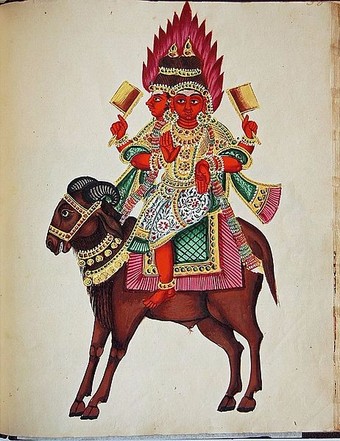

Agni, God of Fire

Agni, the Indian God of Fire from the ancient Vedic religion, shown riding a ram.

Vedas and

Castes

The Caste System, or groups based on birth or employment status, has been part of the

social fabric of the Indian Subcontinent since ancient times. The castes are

thought to have derived from a hymn found in the Vedas to the deity Purusha,

who is believed to have been sacrificed by the other gods. Afterward Purusha’s

mind became the Moon, his eyes became the Sun, his head the Sky, and his feet

the Earth.

The

passage describing the classes of people derived from the sacrifice of Purusha

is the first indication of a caste system. The Brahmins, or priests, came from

Purusha’s mouth; the Kshatriyas, or warrior rulers, came from Purusha’s arms;

the Vaishyas, or commoners such as landowners and merchants, came from Purusha’s

thighs; and the Shudras, or laborers and servants, came from Purusha’s feet.

Today

the castes still exist in the form of varna, or class system, based on the

original four castes described in the Vedas. A fifth group known as Dalits,

historically excluded from the varna system, are ostracized and called

untouchables. The caste system as it exists today is thought to be a product of

developments following the collapse of British colonial rule in India. The system

is frowned upon by many people in Indian society and was a focus of social justice

campaigns during the 20th century by prominent progressive activists such as B.

R. Ambedkar, an architect of the Indian Constitution, and Mahatma Gandhi, the revered

leader of the nonviolent Indian independence movement.

Gandhi at Madras, 1933

Indian independence leader Mahatma Gandhi visits Madras, now Chennai, on a tour of India in 1933. During his appearances Gandhi frequently spoke out against the discrimination of the Indian caste system.

6.3: Religion in the Indian Subcontinent

6.3.1: The Rise of Hinduism

Hinduism evolved as a synthesis of cultures and traditions,

including the Indo-Aryan Vedic religion.

Learning Objective

Explain the evolution of hinduism

Key Points

- The Vedic religion was influenced

by local cultures and traditions adopted by Indo-Aryans as

they spread throughout India. Vedic ritualism heavily influenced the rise of

Hinduism, which rose to prominence after c. 400 BCE. - The Vedas—

the oldest texts of

the Hindu religion—describe deities,

mythology, and instructions for religious rituals. -

The Upanishads are

a collection of Vedic texts particularly important to Hinduism that

contain revealed truths concerning the nature of ultimate reality, and

describing the character and form of human salvation. -

During the 14th and 15th centuries, the Hindu Vijayanagar Empire served as a barrier against Muslim invasion, fostering a reconstruction of Hindu life and administration.

The Hindu Maratha Confederacy rose to power in the 18th century and eventually overthrew Muslim rule in India.

Key Terms

- moksha

-

The character and

form of human salvation, as described in the Upanishads. - Sramana

-

Meaning “seeker,” Sramana refers to several Indian religious movements that existed alongside the Vedic religion, the historical predecessor of modern Hinduism.

- brahman

-

The nature of ultimate reality, as described in the Upanishads.

- Upanishads

-

A collection of Vedic texts that contain the earliest emergence of some of the central religious concepts of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.

Hinduism

is considered one of the oldest religions in the world. Western scholars regard

Hinduism as a synthesis, or fusion, of various Indian cultures and traditions,

with diverse roots and no stated founder. This synthesis is believed to

have developed after Vedic times, between 500 BCE and 300 CE. However, Vedic ritualism, a composite of Indo-Aryan and Harappan culture,

contributed to the deities and traditions of Hinduism. The Indo-Aryan Vedas

remain the oldest scriptures of the Hindu religion, which has grown culturally

and geographically through modern times to become one of the world’s four major

religions.

The Vedas

Vedas,

meaning “knowledge,” were written in Vedic Sanskrit between 1500 and

500 BCE in the northwestern region of the Indian Subcontinent. There are four

Indo-Aryan Vedas: the Rig Veda contains hymns about mythology; the Sama Veda

consists mainly of hymns about religious rituals; the Yajur Veda contains

instructions for religious rituals; and the Atharva Veda consists of spells

against enemies, sorcerers and diseases. (Depending on the source consulted,

these are spelled, for example, either Sama Veda or Samaveda.) The Rig Veda is

the largest and considered the most important of the collection, containing

1,028 hymns divided into ten books, called mandalas.

The

Aryan pantheon of gods is described in great detail in the Rig Veda. However,

the religious practices and deities are not uniformly consistent in these

sacred texts, probably because the Aryans themselves were not a homogenous

group. While spreading through the Indian subcontinent, it is probable their

initial religious beliefs and practices were shaped by the absorption of local

religious traditions.

According

to the hymns of the Rig Veda, the most important deities were Agni, the god of

Fire, and the intermediary between the gods and humans; Indra, the god of Heavens and

War, protector of the Aryans against their enemies; Surya, the Sun god; Vayu,

the god of Wind; and Prthivi, the goddess of Earth.

Modern Hindu representation of Agni, god of fire

The Rig Veda describes the varied deities of Vedic religion. These gods persisted as Vedic religion was assimilated into Hinduism.

The

Upanishads

The

Upanishads are a collection of Vedic texts that contain the earliest emergence

of some of the central religious concepts of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. Also known as Vedanta,

“the end of the Veda,” the collection is one of the sacred texts of

Hinduism thought to contain revealed truths concerning the nature of ultimate

reality, or brahman, and describing the character and form of human salvation, called

moksha. The Upanishads are found in the conclusion of the commentaries on the Vedas, and have been passed down by oral

tradition.

Hindu Synthesis

Sramana,

meaning “seeker,” refers to several Indian religious movements, including Buddhism

and Jainism, that existed alongside the Vedic religion—the historical

predecessor of modern Hinduism. The Sramana traditions drove the so-called Hindu

synthesis after the Vedic period that spread to southern Indian and parts of

Southeast Asia. As it spread, this new Hinduism assimilated popular non-Vedic

gods and other traditions from local cultures, and integrated societal

divisions, called the caste system. It is also thought to

have included both Buddhist and Sramana influences.

Splinter and Rise of Hinduism

During

the reign of the Gupta Empire (between 320-550 CE), which included the period

known as the Golden Age of India, the first known stone and cave temples

dedicated to Hindu deities were built. After the Gupta period, central power disintegrated

and religion became regionalized to an extent, with variants arising within Hinduism

and competing with each other, as well as sects of Buddhism and Jainism. Over

time, Buddhism declined but some of its practices were integrated into

Hinduism, with large Hindu temples being built in South and Southeast Asia.

The Swaminarayan Akshardham Temple in Delhi, the world’s largest Hindu temple

Hinduism evolved as a combination of various cultures and traditions, including Vedic religion and the Upanishads.

The

Hindu religion maintained its presence and continued to grow despite a long period

of Muslim rule in India, from 1200-1750 CE, during which Hindus endured violence

as Islam grew to become what is now the second largest religion in India,

behind Hinduism. Akbar I, emperor of the ruling Mughal Dynasty in India from

1556-1605 CE, ended official persecution of non-Muslims and recognized Hinduism,

protected Hindu temples, and abolished discriminatory taxes against Hindus.

Hindu Prominence

During

the 14th and 15th centuries, the Hindu Vijayanagar Empire had arisen and served

as a barrier against invasion by Muslim rulers to the north, fostering a

reconstruction of Hindu life and administration. Vidyaranya, a minister and

mentor to three generations of kings in the Vijayanagar Empire beginning around

1336, helped spread the historical and cultural influence of Shankara—an Indian

philosopher of the 8th century CE credited with unifying and establishing the

main currents of thought in Hinduism.

The

Hindu Maratha Confederacy rose to power in the 18th century and eventually

overthrew Muslim rule in India. In the 19th century, the Indian subcontinent became

a western colony during the period of the British Raj (the name of the British

ruling government) beginning in 1858.

Through

the period of the Raj, until its end in 1947, there was a Hindu resurgence, known

as the Bengali Renaissance, in the Bengal region of India. It included a

cultural, social, intellectual, and artistic movement. Indology, an academic study

of Indian culture, was also established in the 19th century, and spread

knowledge of Vedic philosophy and literature and promoted western interest in

Hinduism.

In

the 20th century, Hinduism gained prominence as a political force and source of

national identity in India. According to the 2011 census, Hindus account for

almost 80% of India’s population of 1.21 billion people, with 960

million practitioners. Other nations with large Hindu populations include Nepal, with 23 million followers, and Bangladesh, with 15 million. Hinduism counts over

1 billion adherents across the globe, or approximately 15% of the world’s

population.

Singapore Diwali Decorations

Diwali decorations in Little India are part of an annual Hindu celebration in Singapore, where there are over 260,000 Hindus.

6.3.2: The Sramana Movement

Sramana broke with Vedic Hinduism over the

authority of the Brahmins and the need to follow ascetic lives.

Learning Objective

Understand the Sramana movement

Key Points

-

Sramana was an ancient Indian

religious movement with origins in the Vedic religion. However, it took a divergent

path, rejecting Vedic Hindu ritualism and the authority of the Brahmins—the

traditional priests of the Hindu religion. - Sramanas were those who practiced an ascetic, or

strict and self-denying, lifestyle in pursuit of spiritual liberation. They are commonly known as monks. - The Sramana movement gave rise to Jainism and Buddhism.

Key Terms

- Sramana

-

An ancient Indian religious movement that began as an offshoot of the Vedic religion and focused on ascetic lifestyle and principles.

- Brahmin

-

A member of a caste in Vedic Hinduism, consisting of priests and teachers who are held as intermediaries between deities and followers, and who are considered the protectors of the sacred learning found in the Vedas.

- Sramanas

-

Sramana followers who renounced married and domestic life, and adopted an ascetic path. The Sramanas rejected the authority of the Brahmins.

- Vedic Religion

-

The historical predecessor of modern Hinduism. The Vedas are the oldest scriptures in the Hindu religion.

- ascetic

-

A person who practices severe self-discipline and abstention from worldly pleasures as a way of seeking spiritual enlightenment and freedom.

Sramana

was an ancient Indian religious movement that began as an offshoot of the Vedic

religion and gave rise to other similar but varying movements, including

Buddhism and Jainism. Sramana, meaning “seeker,” was a tradition that began around

800-600 BCE when new philosophical groups, who believed in a more austere path to spiritual

freedom, rejected the authority of the Brahmins (the priests of Vedic Hinduism). Modern Hinduism can be regarded as a

combination of Vedic and Sramana traditions; it is substantially influenced

by both.

Vedic Roots

The

Vedic Religion was the historical predecessor of modern Hinduism. The

Vedic Period refers to the time period from approximately 1750-500 BCE, during

which Indo-Aryans settled into northern India, bringing with them specific

religious traditions. Most history of this period is derived from the Vedas, the

oldest scriptures in the Hindu religion. Vedas, meaning “knowledge,”

were composed by the Aryans in Vedic Sanskrit between 1500 and 500 BCE, in the northwestern

region the Indian subcontinent.

There

are four Indo-Aryan Vedas: the Rig Veda contains hymns about their mythology;

the Sama Veda consists mainly of hymns about religious rituals; the Yajur Veda

contains instructions for religious rituals; and the Atharva Veda consists of

spells against enemies, sorcerers, and diseases. (Depending on the source

consulted, these are spelled, for example, either Rig Veda or Rigveda.)

Sramana Origins

Several

Sramana movements are known to have existed in India before the 6th century

BCE. Sramana existed in parallel to,

but separate from, Vedic Hinduism. The dominant Vedic ritualism contrasted with

the beliefs of the Sramanas followers who renounced married and domestic life

and adopted an ascetic path, one of severe self-discipline and abstention from

all indulgence, in order to achieve spiritual liberation. The Sramanas rejected the

authority of the Brahmins, who were considered the protectors of the sacred

learning found in the Vedas.

Emaciated Fasting Buddha

Buddha practiced severe asceticism before his enlightenment and recommended a non-ascetic middle way.

Brahmin

is a caste, or social group, in Vedic Hinduism consisting of priests and

teachers who are held as intermediaries between deities and followers. Brahmins

are traditionally responsible for religious rituals in temples, and for reciting

hymns and prayers during rite of passage rituals, such as weddings.

In

India, Sramana originally referred to any ascetic, recluse, or religious

practitioner who renounced secular life and society in order to focus solely on finding religious

truth. Sramana evolved in India over two phases: the Paccekabuddha, the tradition of the individual ascetic, the “lone

Buddha” who leaves the world behind; and the Savaka, the phase of disciples, or

those who gather together as a community, such as a sect of monks.

Sramana Traditions

A “tradition” is a belief or behavior passed down within a group or society, with symbolic

meaning or special significance. Sramana traditions drew upon established Brahmin concepts to

formulate their own doctrines.

The

Sramana traditions subscribe to diverse philosophies, and at times significantly disagree

with each other, as well as with orthodox Hinduism and its six schools of Hindu philosophy.

The differences range from a belief that every individual has a soul, to the

assertion that there is no soul. In terms of lifestyle, Sramana traditions include

a wide range of beliefs that can vary, from vegetarianism to meat eating, and from family

life to extreme asceticism denying all worldly pleasures.

The

varied Sramana movements arose in the same circles of ancient India that led to

the development of Yogic practices, which include the Hindu philosophy of

following a course of physical and mental discipline in order to attain liberation from

the material world, and a union between the self and a supreme being or principle.

The

Sramana traditions drove the so-called Hindu synthesis after the Vedic period, which spread to southern Indian and parts of Southeast Asia. As it spread, this

new Hinduism assimilated popular non-Vedic gods and other traditions from local

cultures, as well as the integrated societal divisions, called the caste system.

Sramaṇa traditions later gave rise to Yoga, Jainism, Buddhism, and

some schools of Hinduism. They also led to popular concepts in all major Indian religions, such as saṃsāra, the cycle of birth and death, and moksha, liberation from that cycle.

Jain Monk in Meditation

An image of a Jain monk, one of the practitioners of the varied Sramana traditions.

6.3.3: Buddhism

After attaining Enlightenment, Siddhartha Gautama became known

as the Buddha, and taught a Middle Way that became a major world religion, known as Buddhism.

Learning Objective

Understand the development of Buddhism as a major world religion

Key Points

-

Sramanas were those who practiced an

ascetic, or strict and self-denying, lifestyle in pursuit of spiritual liberation. They are commonly known as monks. - The Sramana movement gave rise to Buddhism,

a non-theistic religion that encompasses a variety of traditions, beliefs, and

practices, and arose when Siddhartha Gautama began following Sramana traditions

in the 5th century BCE. - Following his “Enlightenment,” Siddhartha became known as Buddha, or “Awakened One.” He began teaching a

Middle Way to spiritual Nirvana, a release from all earthly burdens. - Buddhism has spread to become one

of the world’s great religions, with an estimated 488 million followers.

Key Terms

- Noble Eightfold Path

-

The eight concepts taught by Buddha as the means to achieving Nirvana.

- Siddhartha Gautama

-

An aristocratic young man who gave up worldly comforts to follow Sramana, then attained Enlightenment and became known as the Buddha, teaching a Middle Way toward spiritual Nirvana.

- Nirvana

-

A sublime state

that marks the release from the cycle of rebirths, known in the Sramana tradition as samsara. - Sramana

-

An offshoot of the Vedic religion that promoted an ascetic lifestyle; Sramana gave rise to Buddhism and other similar traditions.

Buddhism

arose between 500-300 BCE, when Siddhartha Gautama, a young man from an

aristocratic family, left behind his worldly comforts to

seek spiritual enlightenment. He became a teacher commonly known as the Buddha,

meaning “the awakened one,” and Buddhism spread to become a non-theistic

religion that encompasses a variety of traditions, beliefs, and practices

largely based on his teachings.

Sramana Origins

Buddhism

is based on an ancient Indian religious philosophy called Sramana, which began

as an offshoot of the Vedic religion. Several Sramana movements are known to

have existed in India before the 6th century BCE. Sramana existed in parallel to, but separate

from, Vedic Hinduism, which followed the teachings and rituals found in the

Vedas, the most ancient texts of the Vedic religion. Sramana, meaning “seeker,” was a tradition that began when new philosophical groups who believed in a more

austere path to spiritual freedom rejected the authority of the Vedas and the Brahmins,

the priests of Vedic Hinduism, around 800-600 BCE.

Sramana

promoted spiritual concepts that became popular in all major Indian religions,

such as saṃsāra, the cycle of

birth and death, and moksha, liberation from that cycle. The

Sramanas renounced married and domestic life, and adopted an ascetic path—

one

of severe self-discipline and abstention from all indulgence—in order to achieve

spiritual liberation. Sramaṇa traditions (or its religious and moral practices) later gave rise to varying schools of

Hinduism, as well as Yoga, Jainism, and Buddhism.

Origins of

Buddhism

Early

texts suggest Siddhartha Gautama was born into the Shakya Clan, a community on

the eastern edge of the Indian subcontinent in the 5th century BCE. His father

was an elected chieftain, or oligarch, of the small republic. Gautama is thought

to have been born in modern-day Nepal, and raised in the Shakya capital of

Kapilvastu, which may have been in Nepal or India. Most scholars agree that he

taught and founded a monastic order during the reign of the Magadha Empire. In

addition to the Vedic Brahmins, the Buddha’s lifetime coincided with the flourishing

of influential Sramana schools of thought, including Jainism.

Buddhist