5.1: The Mythical Period

5.1.1: The Mythical Period

Early prehistoric China is called the “Mythical Period.” It encompassed the legends of Pangu, and the rule of the Three Sovereigns, and the Five Emperors. The period ended when the last Emperor, Shun, left his throne to Yu the Great, and the Xia Dynasty began.

Learning Objective

Recall what innovations emerged under the legendary rulers of China’s Mythical Period

Key Points

- By 2000 BCE, cities developed in China, and the various cultures of the area began to merge into a larger, more unified Chinese culture.

- Most of what we know about the first part of prehistoric China is from Chinese mythology, which is why it’s now known as the Mythical Period.

- The Mythical Period includes the rule of the Three Sovereigns and the Five Emperors.

- The last of the Five Emperors was Emperor Shun. He left his throne to Yu the Great, who founded the Xia dynasty and instituted the practice of passing rulership to a son.

Key Terms

- urbanism

-

The change in a country or region when its population migrates from rural to urban areas.

- millet

-

Any of a group of various types of grass or its grains used as food, widely cultivated in the developing world.

- Go

-

An abstract strategy board game for two players, where the object is to surround more territory than the opponent.

- Yangtze

-

The longest river in Asia, the Yangtze flows from the highlands of Tibet through central China, and empties into the Pacific Ocean at Shanghai.

- Yellow River

-

Huang He in Chinese. A river of northern China which flows for 5,463 km (3,000 miles) to the Yellow Sea.

- Pangu

-

A mythical Chinese being who created the universe.

- Huai

-

A major river in China located about midway between the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers.

- Gilgamesh

-

The hero of a Babylonian epic, and the legendary king of the Sumerian city state of Uruk.

History as Told by Archaeological Evidence

As in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus River valley, civilization in China developed around a great river. The Yellow River and the Huai and Yangtze Rivers, created fertile land, ripe for experimentation with agriculture. By around 4000 BCE, villages began to appear in these areas. The Neolithic Chinese cultivated a number of crops; the most important was a grain called millet. They also domesticated animals, such as pigs, dogs, and chickens. Silk production, through the domestication of silkworms, also likely began in this early period.

These villages influenced each other more and more over time, and by 2000 BCE a unified Chinese culture began to develop. There is also evidence of urbanism and the use of early writing d this time. These phenomena took place in China about 1000 years later than in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus River valley.

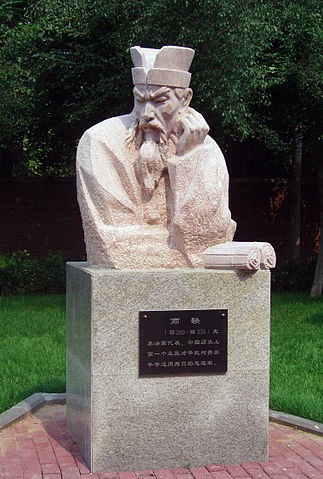

Pangu

Portrait of Pangu, the creator of the universe according to Chinese mythology. This portrait is from Sancai Tuhui, a Chinese encyclopedia published in 1609, during the Ming Dynasty.

History as Told by Chinese Legend

Chinese mythology tells a different story of the beginning of civilization. It holds that the universe was created by Pangu, the first living being. After his death, Pangu’s left eye became the sun and his right eye became the moon. The Three Sovereigns and the Five Emperors, a series of legendary sage emperors and heroes, helped create man. These legendary rulers taught the ancient Chinese to speak, use fire, build houses, farm, and make clothing. Fuxi and his wife, Nüwa, were credited with introducing domesticated animals and creating the basic social structure of family life. Shennong was a divine farmer who gave the people knowledge of agriculture.

The existence of these emperors occurred before written Chinese history, and so the dates of reign are uncertain. The Five Emperors began with Huangdi, or the Yellow Emperor, whose reign is believed to be from 2698-2599 BCE. He was considered the founding ancestor of the Han Chinese ethnic group, and is credited with the invention of Chinese characters, silk, and traditional Chinese medicine.

The Yellow Emperor, or Huangdi.

Portrait of the first of the Five Emperors, who was considered the original ancestor for Han Chinese.

Next came Zhuanxu, who was credited with the invention of the Chinese calendar and the introduction of religion and astrology. Little is known about Emperor Ku’s reign, believed to be from 2412-2343 BCE. Emperor Yao, whose reign was from 2317-2234 BCE, was credited with being a role model in dignity and diligence to future emperors, and was the inventor of the game “weiqi” (also known as “Go”). The last was Emperor Shun, whose reign was from 2233-2205 BCE, was known for his devotion. He left his throne to Yu the Great, who founded the Xia dynasty, and instituted the practice of passing rulership to a son. While these events are mythological, at their root there may be ancient memories of very early kings and rulers who emerged among the prehistoric Chinese, similar to the tales of Gilgamesh in Mesopotamia.

5.1.2: The Xia Dynasty

The final part of the Mythical Period was under the rule of the legendary Xia Dynasty, which may have been mythological. After the final ruler became corrupt, he was overthrown by Cheng Tang, who founded the Shang Dynasty.

Learning Objective

Recall characteristics of the Xia Dynasty

Key Points

- Sima Qian’s “Historical Records,” the first comprehensive history of China, said that the last of the Five Emperors, Emperor Shun, left his throne to Yu the Great, who founded the Xia Dynasty.

- The Xia Dynasty was the first Chinese dynasty; it is still not known whether this dynasty existed or is only mythological.

- According to mythology, when the last Xia king became corrupt and cruel, Cheng Tang overthrew him in c. 1760 BCE and founded the Shang Dynasty.

- Many argue that the Zhou Dynasty, which ruled China much later, invented the idea of the Xia Dynasty to support their claim that China could only be, and had always been, ruled by one ruler.

Key Terms

- Mandate of Heaven

-

The Chinese philosophical concept of the circumstances under which a ruler is allowed to rule. Good rulers were allowed to rule under the Mandate of heaven, while despotic, unjust rulers had the Mandate revoked.

- Sima Qian

-

A renowned Chinese historiographer of the 2nd century BCE who wrote about the Xia Dynasty.

- Shang Dynasty

-

Also called the Yin Dynasty, succeeded the Xia Dynasty and followed the Zhou Dynasty. It existed in the second millennium BCE.

Sima Qian’s Historical Records

The earliest comprehensive history of China is the Historical Records, written by Sima Qian, a renowned Chinese historiographer of the 2nd century BCE. This history begins around 3600 BCE, with an account of the Five Emperors. According to this history, the last of the great Five Emperors, Emperor Shun, left his throne to Yu the Great, who founded China’s First Dynasty, the Xia Dynasty. Yu supposedly began the practice of inherited rule (passing power from father to son), a model that was perpetuated in the later Shang and Zhou dynasties.

Depiction of Yu the Great

This hanging scroll shows Yu the Great, as imagined by Song Dynasty painter Ma Lin.

According to mythology, Yu’s descendants ruled China for nearly 500 years, until the last Xia king became corrupt and cruel. This led to his overthrow in c. 1760 BCE by Cheng Tang, who founded a new dynasty, the Shang Dynasty, in the Huang River Valley.

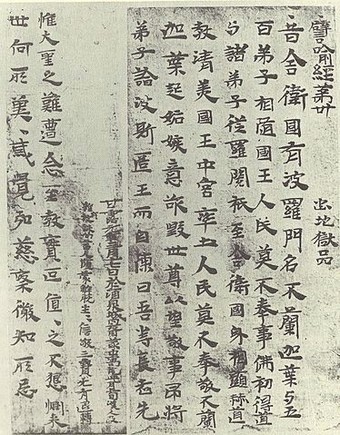

Sima Qian’s Historical Records

The first page of Sima Qian’s Historical Records.

Debate Over the Existence of the Xia Dynasty

There is much debate among scholars about how much of this mythology is true. Many argue that the Zhou Dynasty, which ruled China much later, invented the idea of the Xia Dynasty to support their claim that China could only be, and had always been, ruled by one ruler. The Zhou created the idea of the “Mandate of Heaven,” which stated that there could be only one legitimate ruler of China at any given time. If he was a good ruler, he would have the support of heaven; if he was despotic, he would be overthrown. The various small states that had comprised Neolithic and Bronze Age China contradicted this version of history. Some people argue, therefore, that the Zhou may have created the idea of an ancient Xia Dynasty to support the idea that China always had one ruler.

Nonetheless, the Xia Dynasty may not be a complete fabrication; recent archaeological evidence may support its existence. (For a long time it was believed that the later Shang Dynasty may also have been purely mythological, until archaeology proved that it was real.) Archaeologists have discovered an advanced Bronze Age culture in China. Its capital, Erlitou, was a huge city around 2000 BCE. This may in fact be the people referred to in Chinese mythology as the Xia. It is believed that the Xia may have created a primitive writing system, though no evidence of this has been found. However, evidence does suggest that the Xia developed agricultural methods and experienced considerable prosperity. However, lack of irrigation and flood protection made the region prone to frequent floods and other natural disasters.

5.2: The Shang Dynasty

5.2.1: Introduction to the Shang Dynasty

The Shang Dynasty existed in the Yellow River Valley during the second millennium BCE. It built huge cities, monopolized bronze, and developed writing, until it was overthrown by the Zhou.

Learning Objective

Compare the Shang Dynasty with the earlier Xia Dynasty

Key Points

- The Shang Dynasty (also called the Yin Dynasty) succeeded the Xia Dynasty, and was followed by the Zhou Dynasty. It was located in the Yellow River valley, during the second millennium BCE.

- The Shang Dynasty is the first period of prehistoric China that has been conclusively proven to have existed by archaeological evidence, such as excavated graves and oracle bones, the oldest substantial evidence of Chinese writing.

- Writing during the Shang Dynasty was already in an advanced form, suggesting that the written language had already existed for a long time.

- Under the Shang Dynasty, the Chinese built huge cities with strong social class divisions, expanded irrigation systems, and monopolized the use of bronze.

- The Shang Dynasty was overthrown in 1046 BCE by the Zhou, who established their own dynasty.

Key Terms

- Oracle bones

-

Inscriptions of divination records on the bones or shells of animals, dating to the Shang Dynasty of ancient China.

- Anyang

-

A city from the Shang Dynasty, the excavation of which yielded large numbers of oracle bones. This helped prove the existence of the Shang Dynasty.

- Zhengzhou

-

The modern-day area where the new capital of Shang was established during the Shang Dynasty.

- Xia Dynasty

-

The first dynasty in traditional Chinese history.

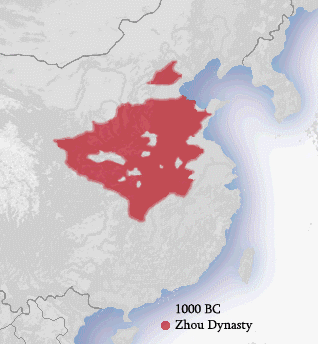

The Shang Dynasty (also

called the Yin Dynasty) succeeded the Xia Dynasty, and was followed by the Zhou

Dynasty. It was located in the Yellow River valley during the second millennium

BCE.

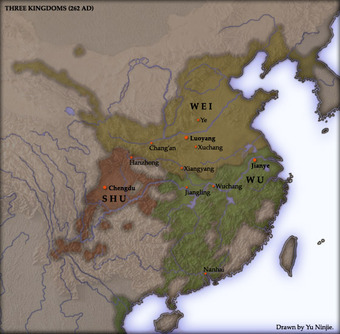

Map of Shang Dynasty

This map shows the location of the Shang Dynasty in the Yellow River valley.

Jie, the last king of the Xia Dynasty (the first Chinese dynasty), was overthrown c. 1760 BCE by Cheng Tang. It is estimated the Shang ruled from either 1766-1122 or 1556-1046

BCE.

While scholars still debate whether the Xia Dynasty actually existed, there is little doubt that the Shang Dynasty existed. The Shang Dynasty is, therefore, generally considered China’s first historical dynasty.

Under the Shang Dynasty, a unified sense of Chinese culture emerged. This culture would continue to thrive and evolve, and many modern Chinese still see the Shang culture as China’s dominant culture. Under the Shang Dynasty, the Chinese built huge cities with strong social class divisions, expanded irrigation systems, monopolized the use of bronze, and developed a system of writing. Shang kings were believed to fulfill sacred, not political, purposes. Instead, a council of chosen advisers administered various aspects of the government. The border territories of Shang rule were led by chieftains, who gained the right to govern through connections with royalty.

The Shang Dynasty was overthrown in 1046 BCE by the Zhou, a subject people living in the western part of the kingdom.

Archaeological Evidence

The Shang Dynasty is the oldest

Chinese dynasty supported by archaeological finds. These have included 11 major Yin royal tombs and building sites of palaces and rituals, as well as weapons

and remains of human and animal sacrifices, and artifacts, including bronze,

jade, stone, bone, and ceramic.

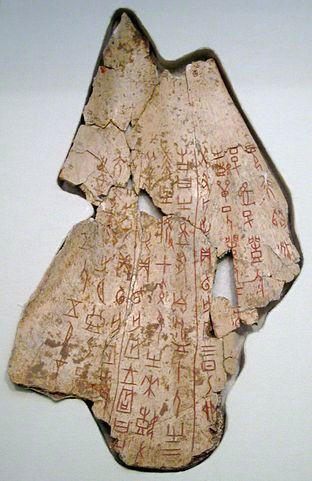

The oldest surviving form of Chinese writing is inscriptions of divination records on the bones or shells of animals—so-called oracle bones. However, the writing on the oracle bones shows evidence of complex development, indicating that written language had existed for a long time. In fact, modern scholars are able to read it because the language was very similar to the modern Chinese writing system.

Archaeologists have also found ancient cities that correspond with the Shang Dynasty. When Cheng Tang overthrew the last king of the Xia Dynasty, he supposedly founded a new capital for his dynasty at a town called Shang, near modern-day Zhengzhou. Archaeological remains of this town may have been found—it seems to have functioned as a sacred capital, where the most sacred temples and religious objects were housed. This city also had palaces, workshops, and city walls.

Anyang, in modern-day Henan, is another important (but slightly later) Shang city that has been excavated. This site yielded large numbers of oracle bones that describe the travels of eleven named kings. The names and timeframes of these kings match traditional lists of Shang kings. Anyang was a huge city, with an extensive cemetery of thousands of graves and 11 large tombs—evidence of the city’s labor force, which may have belonged to the 11 Shang kings.

5.2.2: Society Under the Shang Dynasty

The Shang Dynasty was located in the Yellow River valley in China during the second millennium BCE. It was a society that followed a class system of land-owners, soldiers, bronze workers, and peasants.

Learning Objective

Summarize the social class system during the Shang Dynasty

Key Points

- The Shang Dynasty (also called the Yin Dynasty) succeeded the Xia Dynasty, and was followed by the Zhou Dynasty. It was located in the Yellow River valley during the second millennium BCE. Citizens of the Shang Dynasty were classified into four social classes: the king and aristocracy, the military, artisans and craftsmen, and peasants.

- Members of the aristocracy were the most respected social class, and were responsible for governing smaller areas of the dynasty.

- Next in social status were the Shang military—both the infantry and the chariot warriors.

- The Shang “middle class” were artisans and craftsmen, who mainly worked with bronze.

- The poorest class in Shang society were the peasants, who were mostly farmers. Some scholars believe they functioned as slaves; others believe they were more like serfs.

Key Terms

- aristocracy

-

The nobility, or the hereditary ruling class.

- artisans

-

Skilled manual workers, who use tools and machinery in a particular craft.

- peasants

-

Members of the lowest social class, who toil on the land. This social class consisted of small farmers and tenants, sharecroppers, farmhands, and other laborers on the land, forming the main labor force in agriculture and horticulture.

The Shang Dynasty (also called the Yin Dynasty) succeeded the Xia Dynasty, and was followed by the Zhou Dynasty. It was located in the Yellow River valley during the second millennium BCE. It featured a stratified social system made up of aristocrats, soldiers, artisans and craftsmen, and peasants.

The Aristocracy and the Military

The aristocracy were centered around Anyang, the Shang capital, and conducted governmental affairs for the surrounding areas. Regional territories farther from the capital were also controlled by the wealthy.

The Shang military were next in social status, and who were respected and honored for their skill. There were two subdivisions of the military: the infantry (foot soldiers) and the chariot warriors. The latter were noted for their great skill in warfare and hunting. Archaeological evidence has supported the use of horses and other cavalry during the late Shang period, c. 1250 BCE.

Bronze battle-axe

A bronze battle-axe dated to the Shang Dynasty.

Artisans and Craftsmen

Artisans and craftsmen comprised the middle class of Shang society. Their largest contribution was their work with bronze, which the Chinese developed as early as 1500 BCE. Their work with bronze was a very important aspect of society. Bronze weapons and pottery were commonly made, but the most prominent creations included ritual vessels and treasures, many of which were discovered via archaeological findings in the 1920s and 1930s. Shang aristocrats and the royalty were likely buried with large numbers of bronze valuables, particularly wine vessels and other ornate structures.

Houmuwu Ding

The “Houmuwu Ding” is the heaviest piece of bronze work found in China so far.

Peasants

At the bottom of the social ladder were the peasants, the poorest of Chinese citizens. They comprised the majority of the population, and were limited to farming and selling crops for profit. Archaeological findings have shown that masses of peasants were buried with aristocrats, leading some scholars to believe that they were the equivalent of slaves. However, other scholars have countered that they may have been similar to serfs. Peasants were governed directly by local aristocrats.

5.2.3: Shang Religion

Shang religion was characterized by a combination of animism, shamanism, spiritual control of the world, divination, and respect and worship of dead ancestors, including through sacrifices.

Learning Objective

Explain the religious foundation of Shang Dynasty culture

Key Points

- The Shang believed in spiritual control of the world by various gods. They also practiced ancestor worship. They appealed to the gods, including the supreme god Shangdi, and consulted their ancestors through oracle bones.

- The Shang established a lunar calendar using 29-day months, and 12-month years.

- There appears to have been a belief in the afterlife during the Shang Dynasty, evidenced by human and animal bodies and artifacts found in tombs.

Key Terms

- shamanism

-

A shaman is a person who is seen to have access

to and influence in the world of spirits, and who typically enters a trance

state during rituals, and practices divination and healing. - animism

-

The belief that spirits inhabit some or all classes of natural objects or phenomena, and that an immaterial force animates the universe.

- oracle bones

-

Inscriptions of divination records on the bones or shells of animals, dating to the Shang Dynasty of ancient China.

- divination

-

The

practice of seeking knowledge of the future or the unknown by supernatural

means.

Shang Religion

Shang religion was characterized by a combination of animism, shamanism, spiritual control of the world, divination, and respect and worship of dead ancestors, including through sacrifice. Different gods represented natural and mythological symbols, such as the moon, sun, wind, rain, dragon, and phoenix. Peasants prayed to these gods for bountiful harvests. Festivals to celebrate gods were also common. In particular, the Shang kings, who considered themselves divine rulers, consulted the great god Shangdi (the “Supreme Being” who ruled over humanity and nature) for advice and wisdom. The Shang believed that the ancestors could also confer good fortune, so they would also consult ancestors through oracle bones in order to seek approval for any major decision, and to learn about future success in harvesting, hunting, or battle.

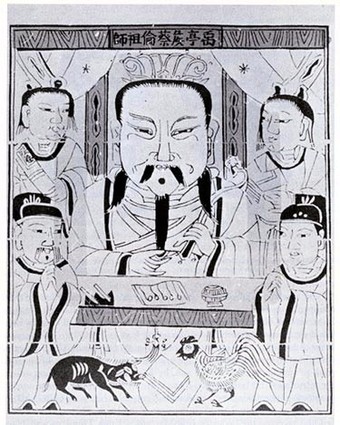

Shangdi

One depiction of Shangdi, the Supreme Being who ruled over humanity and nature.

Oracle Bones and Divination

The

oldest surviving form of Chinese writing is inscriptions of divination records

on the bones or shells of animals—so-called oracle bones. Oracle

bones were pieces of bone or turtle shell used by the ancient Chinese,

especially Chinese kings, in attempts to predict the future. The ancient kings

would inscribe their name and the date on the bone along with a question. They

would then heat the bone until it cracked, and then interpret the shape of the

crack, which was believed to provide an answer to their question.

Questions were carved into oracle bones, such as, “Will we win the upcoming

battle?”, or “How many soldiers should we commit to the battle?” The bones reveal a great deal about what was important to Shang

society. Many of the oracle bones ask questions about war, harvests, and

childbirth.

Oracle Bone

This oracle bone from the Shang Dynasty dates to the reign of King Wu Ding.

The Afterlife

It appears that there was belief in the afterlife during the Shang Dynasty. Archaeologists have found Shang tombs surrounded by the skulls and bodies of human sacrifices. Some of these contain jade, which was seen to protect against decay and give immortality. Archaeologists believed that Shang tombs were very similar to those found in the Egyptian pyramids, in that they buried servants with them. Chinese archaeologists theorize that the Shang, like the ancient Egyptians, believed their servants would continue to serve them in the afterlife, so aristocrats’ servants would be killed and buried with them when they died. Another interpretation is that these were enemy warriors captured in battle.

The Burial Pit at the Tomb of Lady Fu Hao

This tomb is located in the ruins of the ancient Shang Dynasty capital, Yin.

The Lunar Calendar

The Shang also established a lunar calendar that was used to predict and record events, such as harvests, births, and deaths (of rulers and peasants alike). The system assumed a 29-day month that began and ended with each new moon; twelve lunar months comprised one lunar year. Priests and astronomers were trained to recalculate the lunar year and add enough days so that each year lasted 365 days. Because the calendar was used to time both crop planting and the harvest, the king had to employ skilled astronomers to predict dates (and successes) of annual harvests; this would help him maintain support from the people.

5.2.4: Advancements Under the Shang

During the Shang Dynasty, bronze casting became more sophisticated. Military technology also advanced as horses were domesticated and chariots came into existence.

Learning Objective

Describe some of the technical advancements made under the Shang Dynasty

Key Points

- Bronze casting was perhaps

the most important technology during the Shang Dynasty. The Shang made

many objects out of bronze, including ceremonial tools, swords, and

spearheads for the military. - The Shang also domesticated horses and developed the chariot, which gave them a massive military advantage over their opponents.

- With these technologies, the Shang military expanded the kingdom’s borders significantly.

Key Terms

- chariot

-

A two-wheeled, horse-drawn vehicle used in ancient warfare and racing.

- Oracle bone

-

Pieces of ox scapula or turtle plastron, used for divination in ancient China.

Shang Bronze Technology

The Shang ruled China during its Bronze Age; perhaps the most important

technology at the time was bronze casting. The Shang cast bronze objects by

creating molds out of clay, carving a design into the clay, and then pouring

molten bronze into the mold. They allowed the bronze to cool and then broke the

clay off, revealing a completed bronze object.

Shang Dynasty Bronze

This bronze ding vessel dates to the Shang Dynasty.

The

upper classes had the most access to bronze, and they used it for ceremonial

objects, and to make offerings to ancestors. Bronze objects were also buried

in the tombs of Shang elite. The Shang government used bronze for military

weapons, such as swords and spearheads. These weapons gave them a distinct advantage

over their enemies.

Shang Military Technology

The chariot was military technology that allowed the Shang to excel at war. Under the Shang, the Chinese domesticated the horse. Horses of that

time were still too small to ride, but the Chinese gradually

developed the chariot, which harnessed the horse’s power. The chariot was a

devastating weapon in battle, and it also allowed Shang soldiers to move vast

distances at great speeds. A chariot burial site at Anyang (modern-day Henan) dates to the rule of King Wu Ding of the Shang Dynasty (c. 1200 BCE). Oracle bone inscriptions show that the Shang used chariots as mobile command vehicles and in royal hunts. Members of the royal household were often buried with a chariot, horses and a charioteer.

These

military technologies were important, because the Shang were

constantly at war. A significant number of Shang oracle bones were concerned

with battle. The Shang armies expanded the borders of the kingdom and captured

precious resources and prisoners of war, who could be enslaved or used as human sacrifice. The

oracle bones also show deep concern over the “barbarians” living

outside the empire, who were a constant threat to the safety and stability of

the kingdom; the military had to be constantly ready to fight them.

Shang Dynasty Bronze Battle Axe

This bronze axe is an example of Shang bronze work.

5.3: The Zhou Dynasty

5.3.1: The Mandate of Heaven

The Zhou Dynasty overthrew the Shang Dynasty, and used the Mandate of Heaven as justification.

Learning Objective

Describe the Zhou Dynasty’s justification for overthrowing the Shang Dynasty

Key Points

- In 1046 BCE, the Shang Dynasty was overthrown at the Battle of Muye, and the Zhou Dynasty was established.

- The Zhou created the Mandate of Heaven: the idea that there could be only one legitimate ruler of China at a time, and that this ruler had the blessing of the gods. They used this Mandate to justify their overthrow of the Shang, and their subsequent rule.

- Some scholars think the earlier Xia Dynasty never existed—that it was invented by the Zhou to support their claim under the Mandate that there had always been only one ruler of China.

Key Terms

- Battle of Muye

-

The battle that resulted with the Zhou, a subject people living in the western part of the kingdom, overthrew the Shang Dynasty.

- Mandate of Heaven

-

The Chinese philosophical concept of the circumstances under which a ruler is allowed to rule. Good rulers were allowed to rule under the Mandate of Heaven, while despotic, unjust rulers had the Mandate revoked.

The Fall of the Shang

In 1046 BCE, the Zhou, a subject people living in the western part of the kingdom, overthrew the Shang Dynasty at the Battle of Muye. This was a battle between Shang and Zhou clans, over the Shang’s expansion. They largely had the support of the Chinese people: Di Xin (the final king of the Shang Dynasty) had become cruel, spent state money on drinking and gambling, and ignored the state. The Zhou established authority by forging alliances with regional nobles, and founded their new dynasty with its capital at Fenghao (near present-day Xi’an, in western China).

Map of Zhou Dynasty

This map shows the location of the ancient Zhou Dynasty.

The Mandate of Heaven

Under the Zhou Dynasty, China moved away from worship of Shangdi (“Celestial Lord”) in favor of worship of Tian (“heaven”), and they created the Mandate of Heaven. According to this idea, there could be only one legitimate ruler of China at a time, and this ruler reigned as the “Son of Heaven” with the approval of the gods. If a king ruled unfairly he could lose this approval, which would result in his downfall. Overthrow, natural disasters, and famine were taken as a sign that the ruler had lost the Mandate of Heaven.

The Chinese Character for “Tian”

The Chinese character for “Tian,” meaning “heaven,” in (from left to right) Bronze script, Seal script, Oracle script, and modern simplified.

The Mandate of Heaven did not require a ruler to be of noble birth, and had no time limitations. Instead, rulers were expected to be good and just in order to keep the Mandate. The Zhou claimed that their rule was justified by the Mandate of Heaven. In other words, the Zhou believed that the Shang kings had become immoral with their excessive drinking, luxuriant living, and cruelty, and so had lost their mandate. The gods’ blessing was given instead to the new ruler under the Zhou Dynasty, which would rule China for the next 800 years.

The need for the Zhou to create a history of a unified China is also why some scholars think the Xia Dynasty may have been an invention of the Zhou. The Zhou needed to erase the various small states of prehistoric China from history, and replace them with the monocratic Xia Dynasty in order for their Mandate of Heaven to seem valid (i.e., to support the claim that there always would be, and always had been, only one ruler of China).

The Zhou ruled until 256 BCE, when the state of Qin captured Chengzhou. However, the Mandate of Heaven philosophy carried on throughout ancient China.

5.3.2: Society Under the Zhou Dynasty

Under the initial period of the Zhou Dynasty (called the Western Zhou period), a number of innovations were made, rulers were legitimized under the Mandate of Heaven, a feudal system developed, and new forms of irrigation allowed the population to expand.

Learning Objective

Describe the main accomplishments of the Western Zhou period

Key Points

- The first period of Zhou rule, during which the Zhou held undisputed power over China, is known as the Western Zhou period.

- During the Western Zhou period, the focus of religion changed from the supreme god, Shangdi, to “Tian,” or heaven; advances were made in farming technology; and the feudal system was established.

- Under the feudal system, the monarchy would reward loyal nobles with large pieces of land.

- Over time, the king grew weaker, and the lords of the feudal system grew stronger, until finally, in 711 BCE, one lord joined forces with an invading group of barbarians and killed the king.

Key Terms

- Duke of Zhou

-

A regent to the king who established the feudal system, and held a lot of power during the Western Zhou period.

- Western Zhou period

-

The first period of Zhou rule, during which the Zhou held undisputed power over China (1046-771 BCE).

- feudal system

-

A social system based on personal ownership of resources and personal fealty between a suzerain (lord) and a vassal (subject). Defining characteristics include direct ownership of resources, personal loyalty, and a hierarchical social structure reinforced by religion.

The first period of Zhou rule, during which the Zhou held undisputed power over China, is known as the Western Zhou period. This period ended when the capital was moved eastward. A number of important innovations took place during this period: the Zhou moved away from worship of Shangdi, the supreme god under the Shang, in favor of Tian (“heaven”); they legitimized rulers, through the Mandate of Heaven (divine right to rule); they moved to a feudal system; developed Chinese philosophy; and made new advances in irrigation that allowed more intensive farming and made it possible for the lands of China to sustain larger populations.

China created a substantial amount of literature during the Zhou Dynasty. These include The Book of History and The Book of Diviners, which was used by fortune tellers. Books dedicated to songs and ceremonial rites were also created. While many of these writings have been destroyed over time, their lasting impression on history is evidence of the strength of Zhou culture.

Like other river valley civilizations of the time, the people under the Zhou Dynasty followed patriarchal roles. Men chose which children would be educated and whom their daughters were married. The household usually consisted of the head male, his wife, his sons and unmarried daughters.

The feudal system in China was structurally similar to ones that followed, such as pre-imperial Macedon, Europe, and Japan. At the beginning of the Zhou Dynasty’s rule, the Duke of Zhou, a regent to the king, held a lot of power, and the king rewarded the loyalty of nobles and generals with large pieces of land. Delegating regional control in this way allowed the Zhou to maintain control over a massive land area. Under this feudal (fengjian) system, land could be passed down within families, or broken up further and granted to more people.

Most importantly, the peasants who farmed the land were controlled by the feudal system. Slavery had been common during the Shang Dynasty, but this decreased and finally disappeared under the Zhou Dynasty, as social status became more fluid and transitory.

The Duke of Zhou

Portrait of the Duke of Zhou in Sancai Tuhui, a Chinese encyclopedia published in 1609 during the Ming Dynasty.

When the Duke of Zhou stepped down, China was united and at peace, leading to years of prosperity. But this only lasted for about seventy-five years. Over time, the central power of the Zhou Dynasty slowly weakened, and the lords of the fiefs originally bestowed by the Zhou came to equal the kings in wealth and influence. They began to actively compete with them for power, and the fiefs gained independence as individual states.

Finally, in 711 BCE, one rebellious noble, the Marquess of Shen, joined forces with invading barbarians, the Quanrong, to defeat the King You. No one came to the king’s defense, and he was killed. The Zhou capital was sacked by the barbarians, and with this the Western Zhou period ended.

5.3.3: Art Under the Zhou Dynasty

Under the Zhou Dynasty, many art forms expanded and became more detailed, including bronze, bronze inscriptions, painting, and lacquerware.

Learning Objective

Identify some of the art forms prevelant under the Zhou Dynasty

Key Points

- Work in bronze, including inscriptions, continued and expanded in the Zhou Dynasty.

- Few paintings have survived from this period, but we know that they were representations of the real world.

- The production of lacquerware expanded during this period.

Key Term

- lacquer

-

A natural varnish, originating in China or Japan, and extracted from the sap of a sumac tree.

Bronze, Ceramics, and Jade

Chinese script cast onto bronzeware, such as bells and cauldrons, carried over from the Shang Dynasty into the Zhou; it showed continued changes in style over time, and by region. Under the Zhou, expansion of this form of writing continued, with the inclusion of patrons and ancestors.

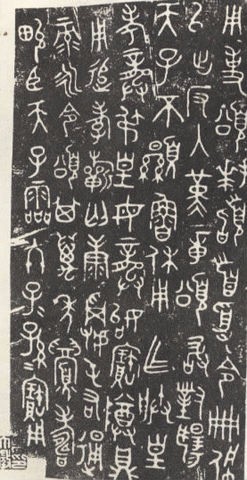

Example of Bronze Inscription

This example of bronze inscription was cast on the Song ding, ca. 800 BCE. The text records the appointment of a man named Song (颂) as supervisor of the storehouses in Chengzhou, and is repeated on at least 3 tripod pots (鼎 dǐng), 5 tureens (簋 guǐ) and their lids, and 2 vases (壺 hú) and their lids.

Other improvements to bronze objects under the Eastern Zhou included greater attention to detail and aesthetics. The casting process itself was improved by a new technique, called the lost wax method of production.

Example of Western Zhou Bronze

A Chinese bronze “gui” ritual vessel on a pedestal, used as a container for grain. From the Western Zhou Dynasty, dated c. 1000 BC. The written inscription of 11 ancient Chinese characters on the bronze vessel states its use and ownership by Zhou royalty.

Ceramic and Jade art continued from the Shang Dynasty, and was improved and refined, especially during the Warring States Period.

Paintings

Very few paintings from the Zhou have survived, however written descriptions of the works have remained. Representations of the real world, in the form of paintings of figures, portraits, and historical scenes, were common during the time. This was a new development. Painting was also done on pottery, tomb walls, and on silk.

Example of Silk Painting

This example of silk painting shows a man riding a dragon, and has been dated to the 5th-3rd century BCE.

Lacquerware

Lacquerware was a technique through which objects were decoratively covered by a wood finish and cured to a hard, durable finish. The lacquer itself might also be inlaid or carved. The Zhou continued and developed lacquer work done in the Shang Dynasty. During the Eastern Zhou period, a large quantity of lacquerware began to be produced.

Example of Lacquerware

These are Chinese Western Han (202 BC – 9 CE) era lacquerwares and lacquer tray unearthed from the 2nd-century-BCE Han Tomb No.1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, China in 1972.

5.3.4: The Eastern Zhou Period

The Eastern Zhou period was divided into two halves. In the Spring and Autumn period, power became decentralized as nobles vied for power. In the Warring States period, strong states fought each other in large-scale war. During the period, there were substantial intellectual and military developments.

Learning Objective

Explain the main political and military developments during the Eastern Zhou period

Key Points

- During the first part of the Eastern Zhou period, called the Spring and Autumn period, the king became less powerful and the regional feudal became lords more so, until only seven consolidated powerful feudal states were left.

- During the second part of the period, called the Warring States period, strong states vied for power until the Qin conquered them all and created a unified dynasty.

- Developments during the period included increasing use of infantry, a trend toward bureaucracy and large-scale projects, the use of iron over bronze, and intellectual and philosophical developments.

Key Terms

- Hegemony

-

Domination, influence, or authority over another, especially by one political group over a society or by one nation over others.

- feudalism

-

A social system in which nobility hold lands from the King in exchange for military service, and peasants lived on the nobles’ land and provided services.

- decentralized

-

Moving away from a single point of administration to multiple locations, and usually giving them a degree of autonomy.

- infantry

-

Soldiers marching or fighting on foot.

The End of the Western Zhou Period

The first period of Zhou rule, which lasted from 1046-771 BCE and was referred to as the Western Zhou period, was characterized mostly by unified, peaceful rule. The lords under feudalism gained increasing power, and ultimately the Zhou King You was assassinated, and the capital, Haojing, was sacked in 770 BCE. The capital was quickly moved east to Chengzhou, near modern-day Luoyang, and the Zhou abandoned the western regions. Thus, the assassination marked the end of the Western Zhou period and the beginning of the Eastern Zhou period.

The Spring and Autumn Period of Eastern Zhou

The first part of the Eastern Zhou period is known as the Spring and Autumn period, named after the Spring and Autumn Annals, a text that narrated events on a year-by-year basis, and marked the beginning of China’s deliberately recorded history. This period lasted from about 771-476 BCE. During this time, power became increasingly decentralized as regional feudal lords began to absorb smaller powers and vie for hegemony. The monarchy continued to lose power, and the people were nearly always at war.

The period from 685-591 BCE was called The Five Hegemons, and featured, in order, the Hegemony of Qi, Song, Jin, Qin, and Chu. By the end of 5th century BCE, the feudal system was consolidated into seven prominent and powerful states—Han, Wei, Zhao, Yue, Chu, Qi, and Qin—and China entered the Warring States period, when each state vied for complete control.

The Warring States Period

This period, in the second half of the Eastern Zhou, lasted from about 475-221 BCE, when China was united under the Qin Dynasty. The partition of the Jin state created seven major warring states. After a series of wars among these powerful states, King Zhao of Qin defeated King Nan of Zhou and conquered West Zhou in 256 BCE; his grandson, King Zhuangxiang of Qin, conquered East Zhou, bringing the Zhou Dynasty to an end.

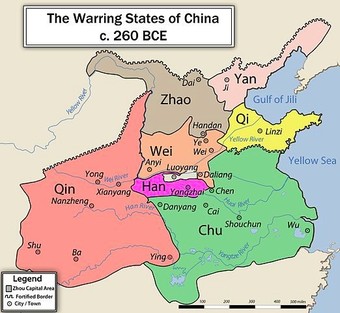

A Map of the Warring States of China

This map shows the Warring States late in the period. Qin has expanded southwest, Chu north and Zhao northwest.

Developments During the Eastern Zhou

While the chariot remained in use, there was a shift during the period to infantry, possibly because of the invention of the crossbow. This meant that war became larger scale, as peasants were drafted to take the place of nobility as soldiers and needed complex logistical support. The aristocracy’s importance dwindled as the king’s became stronger, and strong central bureaucracies took hold. The Art of War, attributed to Sun Tzu, was written during this time; it remains a very influential book about strategy.

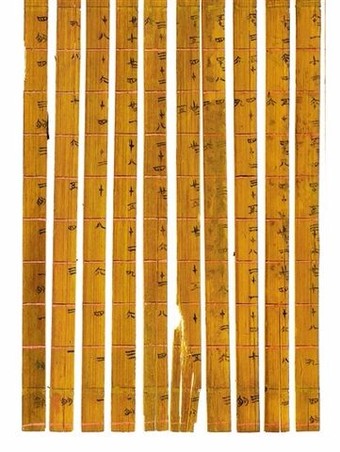

A sophisticated form of commercial arithmetic was in place during the period, as shown by a bundle of bamboo slips showing two digit decimal multiplication.

Bamboo Slips Showing Arithmetic

These bamboo slips show a sophisticated two digit decimal multiplication table.

A history of the Spring and Autumn Period, called the Zuo Commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals, was published during this time.

Developments in iron work replaced bronze as the dominant metal used in warfare. Trade became increasingly important among states within China. Large-scale works, including the Dujiangyan Irrigation System and the Zhengguo Canal, were completed and increased agricultural production.

Iron Sword from the Warring States Period

This iron sword is an example of the metal work done during this period.

5.3.5: The Warring States Period

The Warring States period saw technological and philosophical development, and the emergence of the Qin Dynasty.

Learning Objective

Demonstrate understanding of the main characteristics of the Warring States period

Key Points

- The second part of the Eastern Zhou period is known as the Warring States period. During this time, the seven states remaining from the Spring and Autumn period intensely and unrelentingly battled each other for total power.

- It was during this period that the Iron Age spread in China, leading to stronger tools and weapons made from iron instead of bronze.

- This period also saw the further development of Confucianism (by Mencius), Daoism, Legalism, and Mohism.

- By this time, two key Chinese social characteristics had solidified: l) the concept of the patrilineal family as the basic unit of society, and 2) the concept of natural social differentiation into classes.

- Iron replaced the use of bronze, sophisticated math came into use, and large-scale projects were undertaken.

- Ultimately, in 221 BCE, the Qin state emerged victorious and unified China once more under the Qin Dynasty.

Key Term

- crossbow

-

A mechanised weapon, based on the bow and arrow, that fires bolts; it was invented during the Warring States period of the Zhou Dynasty, when its low cost and ease of use made it a preferable weapon to the chariot.

Over the course of the Spring and Autumn period, regional feudal lords consolidated and absorbed smaller powers; by 476 BCE, seven prominent states were left, all led by individual kings. The second part of the Eastern Zhou period is known as the Warring States period; during this time these few remaining states battled each other for total power.

Conflict Among the Seven States

The king by now was powerless, and the rulers of the seven independent states began to refer to themselves as kings as well. These major Chinese states were in constant competition. Since none of the states wanted any one rival to become too powerful, if one state became too strong, the others would join forces against it, so no state achieved dominance. This led to nearly 250 years of inconclusive warfare that became larger and larger in scale. It was also at this point that there first emerged the concept of a Chinese emperor who would rule over all the various kings, though the first Chinese emperors did not rule until China was unified under the later Qin Dynasty. The crossbow was invented, and its low cost and easy use (as compared to the expensive chariot) resulted in the increased conscription of peasants as expandable infantry.

Technological and Philosophical Development

The Iron Age had reached China by 600 CE, but it was during this period that the age spread and took root in China: by the time of the Warring States Period, China saw a widespread adoption of iron tools and weapons that were significantly stronger than their bronze counterparts.

This period also saw the further development of the philosophical movements that originated in the Hundred Schools of Thought of the Spring and Autumn period. Mencius further developed Confucian philosophy, expanding upon its doctrines and asserting the innate goodness of the individual and the importance of destiny. Daoism, Legalism, and Mohism became more developed. Archaic writing also gave way to a far more recognizable form of Chinese script.

Cultural, Economic, and Social Development

Two fundamental Chinese social characteristics had become apparent by this time: l) the concept of the patrilineal family as the basic unit in society, with high importance placed on blood relations, and 2) the concept of natural social differentiation into classes, each regarded in terms of their contributions to society.

Large-scale projects, like the Dujiangyan Irrigation System and the Zhengguo Canal, were carried out. Sophisticated arithmetic was carried out, including two digit decimal multiplication.

The Zuo Commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals was a literary achievement. In other literary works, sayings of philosophers of the period were recorded in the Analects and the Art of War.

The Rise of the Qin State and Resolution of the Warring States Period

Though the military rivalries and alliances in the Warring States period were complex and constantly in flux, over time the Qin state, under the leadership of King Zheng, emerged as the most powerful. The Qin were particularly strongly rooted in Legalist philosophy, which advocated the importance of the state at the expense of the individual. They were also known for being ruthless and ignoring etiquette and protocol of war in order to win at all costs. In particular, Shang Yang, adviser to Zheng, enacted laws to force subjects of the kingdom to act in ways that helped the state; he forced them to marry early, have many children, and produce certain quotas of food. Ultimately, in 221 BCE, the Qin state conquered the others and established the Qin Dynasty.

5.3.6: Chinese Philosophy

Confucianism, Daoism, Legalism, and Mohism all began during the Zhou Dynasty in the 6th century BCE, and had very strong influences on Chinese civilization.

Learning Objective

Discuss Confucianism, Daoism, Legalism, and Mohism.

Key Points

- Confucius stressed tradition and believed that an individual should strive to be virtuous and respectful, and to fit into his or her place in society.

- Confucianism remained prevalent in China from the Han Dynasty in 202 BCE to the end of dynastic rule in 1911.

- Lao-tzu was the legendary founder of Daoism, recorded in the form of the book the Tao Te Ching.

- Daoism advocated that the individual should follow a mysterious force, called The Way (dao), of the universe, and that all things were one.

- Legalism held that humans were inherently bad and needed to be kept in line by a strong state. According to Legalism, the state was far more important than the individual.

- Legalists could be divided into three types: those concerned with the position of ruler, those concerned with laws, and those concerned with tactics to keep the state safe.

- Mohism emerged under the philosopher Mozi, and its most well-known concept was “impartial care.” Mohism also stated that all people should be equal in their material benefit, and in their protection from harm.

Key Terms

- Five Classics

-

The basis of civil examinations in imperial China and the Confucian canon. They consist of the Book of Odes, the Book of Documents, the Book of Changes, the Book of Rites, and the Spring and Autumn Annals.

- chi

-

Life force or body energy, which supposedly circulates through the body along meridians.

- Tao Te Ching

-

The book which forms the basis of Daoist philosophy.

- Analects

-

The document in which the students of Confucius recorded his teachings.

- jen

-

Human virtue, under Confucianism.

Confucianism

Confucius, who lived during the 6th century BCE, was one of the foremost Chinese philosophers. He looked back on the Western

Zhou period, with its strong centralized state, as an ideal. He was pragmatic

and sought to reform the existing government, encouraging a system of mutual

duty between superiors and inferiors. Confucius stressed tradition and believed

that an individual should strive to be virtuous and respectful, and to fit into

his or her place in society. After his death in 479 BCE, his students wrote down his ethical and moral teachings in the Lun-yü, or Analects.

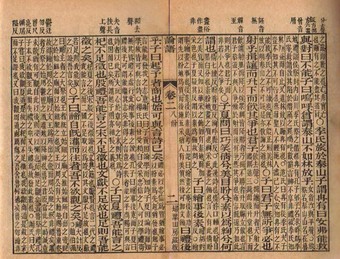

The Analects of Confucius

The ethical and moral teachings of Confucius were written down by his students in this document.

Being a good and virtuous human in every ordinary situation was the goal of Confucianism. This virtue was called “jen,” and humans were seen as perfectible and basically good creatures. Ceremonies and rituals based on the Five Classics, especially the I Ching, were strongly instituted. Some ethical concepts included Yì (the moral disposition to do good), Lǐ (ritual norms for everyday life) and Zhì (the ability to see what is right in the behavior of others).

Confucianism remained prevalent in China from the Han Dynasty in 202 BCE to the end of dynastic rule in 1911. It was reformulated during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) as Neo-Confucianism, and became the basis of imperial exams.

Daoism

Another important

philosopher in this period was Lao-tzu (also called Laozi), who founded Daoism (also called Taoism) during the same period as Confucianism. Lao-tzu is a legendary figure—it is uncertain if he actually existed. According to myth, Lao-tzu was born around 604 BCE as an old man. As he left his home to live a life of solitude, he was asked by the city gatekeeper to write down his thoughts. He did so in a book called Tao Te Ching, and was never seen again.

Lao-Tzu

A depiction of Lao-Tzu, the founder of Daoism.

Daoism advocated that the individual

should follow a mysterious force, called The Way (dao), of the universe and act in accordance with nature.

Daoism stressed the oneness of all things, and was strictly individualistic, as opposed to

Confucianism, which advocated acting as society expected.

Daoism as a religion arose over time, and involved the worship of gods and ancestors, the cultivation of “chi” energy, a system of morals, and the use of alchemy to achieve immortality. It is still practice today.

Legalism

Although Confucianism and Daoism are

the Chinese philosophies that have endured most to this day, even more

important to this early period was a lesser-known philosophy called Legalism. This held that humans are inherently bad and need to be kept in line by a

strong state. According to Legalism, the state was far more important than the

individual. While Legalism held that laws should be clear and public and that

everyone should be subject to them, it also contended that rulers had supreme

power and must use stealth and secrecy to remain in power. Legalists also believed that society must strive to dominate other societies.

Legalists could be divided into three types. The first was concerned with shi, or the investment of the position of ruler with power (rather than the person) and the necessity of obtaining facts to rule well. The second was concerned with fa, or laws, regulations, and standards. This meant all were equal under the ruler, and the state was run by law, not a ruler. The third was the concept of shu, or tactics to keep the state safe. Legalism was

generally in competition with Confucianism, which advocated a just and

reciprocal relationship between the state and its subjects.

Depiction of Shang Yang

Shang Yang was a Legalist reformer under the Qin.

Mohism

Mohism emerged around the same time as the other philosophies discussed here, under the philosopher Mozi (c. 470-391 BCE). The most well-known concept under Mohism was “impartial care,” also known as “universal love.” This meant that people should care equally about other people, regardless of their true relationship to that person. This opposed the ideas of Confucianism, which said that love should be greater for close relationships. Mohism also stressed the ideas of self-restraint, reflection and authenticity.

Depiction of Mozi

The Chinese philosopher who began Mohism is shown here.

Mohism also stated that all people should be equal in their material benefit and in their protection from harm. Society could be improved by having it function like an organism, with a uniform moral compass. Those who were qualified should receive jobs, and thus the ruler would be surrounded by people of talent and skill. An unrighteous ruler would result in seven disasters for the state, including neglect of military defense, repression, illusions about strength, distrust, famine, and more.

5.4: The Qin Dynasty

5.4.1: The Qin Dynasty

The Qin Dynasty saw rich cultural and technological innovation, but brutal rule, and gave way to the Han Dynasty after only 15 years.

Learning Objective

Support the argument that the Qin Dynasty, though short-lived, was one of the most important periods of China’s Classical Age

Key Points

- The leader of the victorious Qin state established the Qin Dynasty and recast himself as Shi Huangdi, the First Emperor of China.

- The Qin Dynasty was one of the shortest in all of Chinese history, lasting only about 15 years, but was also one of the most important. It was marked by a strong sense of unification and crucial technological and cultural innovation.

- Shi Huangdi standardized writing throughout the empire, built expansive infrastructure, such as highways and canals, standardized currency and measurement, conducted a census, and established a postal system.

- Legalism was the official philosophy, and other philosophies, such as Confucianism, were suppressed. Shi Huangdi also built the Great Wall of China, roughly 1,500 miles long and guarded by a massive army, to protect the nation against northern invaders.

- The Qin Dynasty collapsed after only 15 years. There was a brief period of chaos until the Han Dynasty was established.

Key Terms

- Legalism

-

A Chinese philosophy claiming that a strong state is necessary to curtail human self-interest.

- Mandate of Heaven

-

The belief, dating from ancient China, that heaven gives a ruler the right to rule fairly.

- Great Wall of China

-

An ancient Chinese fortification, almost 4,000 miles long, originally designed to protect China from the Mongols. Construction began during the Qin Dynasty, under Shi Huangdi.

When the Qin state emerged victorious from the Warring States period in 221 BCE, the state’s leader, King Zheng, claimed the Mandate of Heaven and established the Qin Dynasty. He renamed himself Shi Huangdi (First Emperor), a far grander title than King, establishing the way in which China would be ruled for the next two millennia. Today he is known as Qin Shi Huang, meaning First Qin Emperor. He relied on brutal techniques and Legalist doctrine to consolidate and expand his power. The nobility were stripped of control and authority so that the independent and disloyal nobility that had plagued the Zhou would not pose a problem.

The Qin Dynasty was one of the shortest in all of Chinese history, lasting only about 15 years, but it was also one of the most important. With Qin Shi Huang’s standardization of society and unification of the states, for the first time in centuries, into the first Chinese empire, he enabled the Chinese to think of themselves as members of a single kingdom. This laid the foundation for the consolidation of the Chinese territories that we know today, and resulted in a very bureaucratic state with a large economy, capable of supporting an expanded military.

Innovations of Emperor Shi Huangdi

The First Emperor divided China into provinces, with civil and military officials in a hierarchy of ranks. He built the Lingqu Canal, which joined the Yangtze River basin to the Canton area via the Li River. This canal helped send half a million Chinese troops to conquer the lands to the south.

Qin Shi Huang standardized writing, a crucial factor in the overcoming of cultural barriers between provinces, and unifying the empire. He also standardized systems of currency, weights, and measures, and conducted a census of his people. He established elaborate postal and irrigation systems, and built great highways.

In contrast, in line with his attempt to impose Legalism, Qin Shi Huang strongly discouraged philosophy (particularly Confucianism) and history—he buried 460 Confucian scholars alive and burned many of their philosophical texts, as well as many historical texts that were not about the Qin state. This burning of books and execution of philosophers marked the end of the Hundred Schools of Thought. The philosophy of Mohism in particular was completely wiped out.

Finally, Qin Shi Huang began the building of the Great Wall of China, one of the greatest construction feats of all time, to protect the nation against barbarians. Seven hundred thousand forced laborers were used in building the wall, and thousands of them were crushed beneath the massive gray rocks. The wall was roughly 1,500 miles long, and wide enough for six horses to gallop abreast along the top. The nation’s first standing army, possibly consisting of millions, guarded the wall from northern invaders.

The Great Wall of China

Sections of the Great Wall of China, from the part known as Jinshanling.

The Terracotta Army

Another of Qin Shi Huang’s most impressive building projects was the preparation he made for his own death. He had a massive tomb created for him on Mount Li, near modern-day Xi’an, and was buried there when he died. The tomb was filled with thousands and thousands of life-sized (or larger) terracotta soldiers meant to guard the emperor in his afterlife. This terracotta army was rediscovered in the twentieth century. Each soldier was carved with a different face, and those that were armed had real weapons.

The Terracotta Army

A close-up of two soldiers in the terracotta army. Note how their faces differ from each other—each soldier was constructed to be unique.

Collapse of the Qin Dynasty

Qin Shi Huang was paranoid about his death, and because of this he was able to survive numerous assassination attempts. He became increasingly obsessed with immortality and employed many alchemists and sorcerers. Ironically, he ultimately died by poisoning in 210 BCE, when he drank an “immortality potion.”

The First Emperor’s brutal techniques and tyranny produced resistance among the people, especially the conscripted peasants and farmers whose labors built the empire. Upon the First Emperor’s death, China plunged into civil war, exacerbated by floods and droughts. In 207 BCE, Qin Shi Huang’s son was killed, and the dynasty collapsed entirely. Chaos reigned until 202 BCE, when Gaozu, a petty official, became a general and reunited China under the Han Dynasty.

5.5: The Han Dynasty

5.5.1: The Rise of the Han Dynasty

The strong but benevolent Han Dynasty began a golden age of reform and expansion. The first period, called the Western Han, lasted until 9 CE.

Learning Objective

Compare the Han Dynasty with the earlier Qin Dynasty, and explain the Western Han period

Key Points

- The Han Dynasty put an end to civil war and reunified China in 202 BCE, ushering in a golden age of peace and prosperity during which progress and cultural development took place.

- The Western Han period continued a lot of the Qin’s policies, but modified them with Confucian ideals. Because of this, the Han lasted far longer than the harsher Qin Dynasty—

the Western Han period in particular lasted until 9 CE, when there was a brief rebellion.

- One of the most exalted Han emperors was Emperor Wu. He made Confucianism the official philosophy, encouraged reciprocity between the state and its people, reformed the economy and agriculture, made contact with India, defended China from the Huns, and doubled the size of the empire.

- Rebellions and external threats posed challenges to the Western Han, but it was able to survive.

Key Terms

- four occupations

-

A hierarchy in which aristocratic scholars had the highest social status, followed by farmers, then craftsmen and artisans, and finally merchants.

- patrilineal

-

Descent through the male line in a family.

- golden age

-

A happy age of peace and prosperity; a time of great progress or achievement.

- xian

-

Mythical afterlife paradise during the Han Dynasty.

- Chu-Han Contention

-

A four-year (206-202 BCE) civil war between the Chu and Han states.

- socialism

-

A political philosophy based on principles of community decision making, social equality, and the avoidance of economic and social exclusion, with preference to community goals over individual ones.

- laissez-faire

-

A policy of governmental non-interference in economic affairs.

Formation of the Han Dynasty

By the time the Qin Dynasty collapsed in 207 BCE, eighteen separate kingdoms had declared their independence. The Han and Chu states emerged as the most powerful, but the Han state was the victor of the Chu-Han Contention, a four-year civil war. Gaozu, who had been born a peasant, founded the Han Dynasty in 202 BCE, reunifying China.

Emperor Gaozu of the Han Dynasty

Emperor Gaozu, formerly known as Liu Bang, founded the Han Dynasty.

The Han Dynasty would become one of the most important and long-lasting dynasties in all of Chinese history. It would rule China for over four hundred years, from 206 BCE-220 CE, and ushered in a golden age of peace, prosperity, and development. Today, both the majority ethnic group in China and Chinese script are called Han.

Comparison of Han to Qin

In many ways, the Han carried on policies that began in the Qin. Provincial rule occurred in both, and the Han continued Legalist rule, although in much less stricter fashion. Confucianism was banned during the Qin, but resurrected during the Han. The Qin, with its focus on the power of the state, was not shaped by religion in the same way the Han was. The Han were considered with the afterlife, and worshipped their ancestors. Both had defined social classes, but in the Han, peasants were treated with greater respect and classes were based on occupations.

The Western Han Period and Political Reform

At first the Han Dynasty established its capital at Chang’an, in western China. This Western Han period would last from 206 BCE to 9 CE, when the dynasty’s rule would be briefly interrupted by rebellion and the short-lived Xin Dynasty.

Throughout the Western Han period, the Han largely continued the governing policies of the Qin, continuing to expand the bureaucracy and encouraging a centralized state. There were, however, differences between the two dynasties, and it was perhaps these differences that allowed the Han to rule for so much longer than the Qin. The Han were more interested in the lives and well-being of their subjects, and they modified some of the harsher aspects of the earlier dynasty’s rule with Confucian ideals of government. Freedom of speech and writing was restored, and the more laissez-faire style of governing allowed harmony, prosperity, and population growth.

This period also saw the further development of the four-class hierarchy, called the “four occupations,” which gave aristocratic scholars the highest social status, followed by farmers, then craftsmen and artisans, and finally merchants.

The family during this time was patrilineal and featured a small number of nuclear family members. Arranged, monogamous marriages were the norm for most. Sons received equal shares of family property and were often sent away when married.

Ritual sacrifices of animals and food were made to deities, spirits, and ancestors at temples and shrines. Each person was seen as having a two-part soul. The spirit-soul, which went to the afterlife paradise of immortals, called xian, and the body-soul, which remained in its earthly tomb.

Other innovations included the first use of negative numbers in mathematics, the recording of stars and comets, the armillary sphere, which represented star movements in three dimensions, the waterwheel, and other engineering feats.

Emperor Wu

One of the most exalted Han emperors was Emperor Wu, who ruled from 141-87 BCE. He was responsible for a great number of innovations and political and military feats.

Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty

A portrait of Emperor Wu, one of the most influential rulers of the Han Dynasty.

Emperor Wu experimented with socialism, and made Confucianism the single official philosophy. The Confucian classics were reassembled and transcribed. The Confucian ideal of each person accepting his social position helped legitimize the state and made people more willing to accept its power. At the same time, these ideals encouraged the state to act justly toward its people. There was reciprocity too in the fact that the state was funded partly by land taxes (a portion of the harvest); this meant that the prosperity of the agricultural estates determined the prosperity of the Han government.

Emperor Wu also founded great government industries and transportation and delivery services, developed governmental control of profit, and imposed a 5% income tax. He created civil-service examinations to test potential government officials on their knowledge of the Confucian classics, so that bureaucrats would be chosen for their intelligence instead of their social connections. Emperor Wu also reformed the Chinese economy and nationalized the salt and iron industries, and he initiated reforms that made farming more efficient.

Through Emperor Wu’s southern and western conquests, the Han Dynasty made contact with the Indian cultural sphere. Emperor Wu repelled the invading barbarians (the Xiongnu, or Huns, a nomadic-pastoralist warrior people from the Eurasian steppe), and roughly doubled the size of the empire, claiming lands that included Korea, Manchuria, and even part of Turkistan. As China pushed its borders further, trade contacts were established with lands to the west, most notably via the Silk Road.

Challenges During the Western Han Period

Nonetheless, the Han faced many challenges. Emperor Gaozu rewarded his supporters with grants of land, which started again the same problems that had brought down the Zhou Dynasty. Several rebellions broke out, the most serious of which was the Rebellion of the Seven States. Nonetheless, the Han emperors stamped out the rebellions and gradually reduced the power of the small kingdoms (though never abolished them completely).

Another major danger to the Han was the external threat of the barbarians, the most dangerous of whom were the Huns. However, the Han Dynasty was able to face these internal and external threats and survive because of the strong centralized state they had established.

5.5.2: The Silk Road

The Silk Road was established by China’s Han Dynasty, and led to cultural integration across a vast area of Asia. It persisted until the fall of the Mongolian Empire in 1360 CE.

Learning Objective

Describe the importance of the Silk Road

Key Points

- The Silk Road was established by China’s Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) through territorial expansion.

- The Silk Road was a series of trade and cultural transmission routes that were central to cultural interaction between the West and East.

- A great deal of protection and stability was provided on the Silk Road by the Han.

- A second Pax Sinica in 737 CE helped the Silk Road reach its golden age of cultural integration.

- The Mongol Empire, and Pax Mongolica, strengthened and re-established the Silk Road between 1207 and 1360 CE. However, as the Mongol Empire disintegrated, so did the Silk Road.

Key Terms

- Pax Sinica

-

Latin term for “Chinese peace” maintained by Chinese hegemony.

- nomadic-pastoralist

-

A lifestyle in which livestock are herded to find fresh grazing pastures in an irregular pattern of movement.

- Pax Mongolica

-

Latin term for “Mongolian peace” during their Empire.

- Tang Dynasty

-

An imperial dynasty of China, from 618-907 CE.

Establishment of the Silk Road

Through southern and western

conquests, the Han Dynasty of China (206 BCE-220 CE) made contact with the Indian cultural sphere.

Emperor Wu repelled the invading barbarians (the Xiongnu, or Huns, a

nomadic-pastoralist warrior people from the Eurasian steppe) and roughly doubled

the size of the empire, claiming lands that included Korea, Manchuria, and even

part of Turkistan. As China pushed its borders further, trade contacts were

established with lands to the west, most notably via the Silk Road.

Map of Silk Road

In this map of the Silk Road, red shows the land route and blue shows the maritime route.

The Silk Road was a series

of trade and cultural transmission routes that were central to cultural

interaction between the West and East. Silk was certainly the major trade item

from China, but many other goods were traded as well. These routes enabled strong

trade relationships to develop with Persia, India, and the Roman Empire.

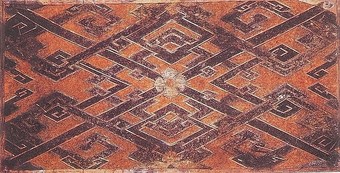

Example of Woven Silk Textile

This woven silk textile from the Western Han era was found at Tomb No. 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province.

Chinese Control of the Silk Road

This expanded western territory became

particularly important because of the silk routes. By this century, the Chinese had become very active in the silk trade, though

until the Hans provided sufficient protection, the Silk Road had not functioned

well because of nomad pirates. Expansion by the Han took place around 114 BCE, led mainly by imperial envoy Zhang Qian. The Great Wall of China was expanded to provide extra protection.

The Tang Dynasty reopened the route in 639 CE, but then lost it to the Tibetans in 678 CE. Control of the Silk Road would shuttle between China and Tibet until 737 CE. This second Pax Sinica helped the Silk Road reach its golden age. China was open to foreign cultures, and its urban areas could be quite cosmopolitan. The Silk Road helped to integrate cultures, but also exposed tribal and pastoral societies to new developments, sometimes causing them to become skilled warriors.

The Mongolian Empire and the Disintegration of the Silk Road

The Mongol Empire, and Pax Mongolica, strengthened and re-established the Silk Road between 1207 and 1360 CE. However, as the Mongol Empire disintegrated, so did the Silk Road. Gunpowder hastened the failing integration, and the Silk Road stopped being a shipping route for silk around 1453 CE. A lasting effect of this was to inspire Europeans to find alternate routes to Asia for trade, including Christopher Columbus’ famous overseas voyage in 1492.

5.5.3: The Eastern Han Period

The Eastern Han period was a time of reunification and prosperity that also saw the perfection of paper and porcelain.

Learning Objective

Describe the Eastern Han period

Key Points

- The 400-year Han Dynasty was briefly interrupted by the rebellious Xin Dynasty. The first part of the Han Dynasty is known as the Western Han period; the Eastern Han period began when the Han overthrew the rebellion and reestablished the dynasty in 25 CE.

- Emperor Guangwu, the first emperor of the Eastern Han period, regained lost land and pacified the people.

- The Rule of Ming and Zhang was an era of prosperity; taxes were reduced, Confucian ideals were encouraged, the government was capable and strong, and the processes of creating paper and porcelain were perfected.

- A series of rebellions led to powerful generals who attempted to control the young emperor. Eventually, three states gained control and the Han Dynasty was ended.

Key Terms

- Chimei

-

A rebel army that ended the Xin dynasty after unrest.

- regent

-

A relative in a royal family who looks after the throne for an underaged king until he is mature enough to receive power.

- porcelain

-

A Chinese innovation perfected during the Eastern Han Period; durable, high-quality, and attractive ceramic ware.

Interruption by the Xin Dynasty

When the Western Han period ended in 9 CE, the regent to the prior emperor, Wang Mang, proclaimed his own new dynasty, the Xin Dynasty. He attempted a number of radical reforms, such as new forms of currency, a ban on slavery, and a return to old models of land distribution. A series of major floods on the Yellow River, however, displaced thousands of peasants, and caused massive unrest. A rebel army called the Chimei (“Red Eyebrows”) developed out of the peasantry, and they defeated Wang Mang’s armies and stormed the capital of Chang’an. They killed Wang Mang and put their own puppet ruler on the throne.

The Eastern Han Period

A new Han emperor, Emperor Guangwu, took control and ruled from Luoyang, in eastern China; thus began the Eastern Han period, which lasted from 25-220 CE. He defeated the Chimei rebels, as well as rival warlords, to reunify China again under the Han Dynasty.

Under Emperor Guangwu, the empire was strengthened considerably. Areas that had fallen away from Chinese control, such as Korea and Vietnam, were reconquered. The Hun Confederation, which had grown strong during China’s period of instability, was pacified.

Emperor Guangwu

Emperor Guangwu ruled during the Eastern Han Dynasty.

Emperor Guangwu was succeeded by Emperor Ming, followed by Emperor Zhang. The Rule of Ming and Zhang, as it is called, is remembered for being an era of prosperity. Taxes were reduced, Confucian ideals were encouraged, and the emperors appointed able administrators. It was also in this period that paper, one of China’s most important inventions, emerged. Though early forms of paper had existed for centuries, the process was now perfected. With paper, Chinese texts could circulate on a durable and relatively inexpensive medium, instead of on clay, silk, or bamboo. This allowed Chinese texts to become more readily available and encouraged learning. Another important innovation of this time was porcelain. Porcelain existed in previous forms for centuries, but was perfected in the Eastern Han period. The improvement of porcelain allowed for durable, high-quality, and attractive ceramic ware.

Ceramic Candle Holder from the Eastern Han Dynasty

A ceramic candle holder from the Eastern Han Dynasty, with prancing animal figures.

The Fall of the Eastern Han

A series of rebellions, including the Yellow Turban and Five Pecks of Rice, began in 184 CE. Military generals appointed during these crises kept their militia forces intact even after defeating the rebels. General-in-Chief He Jin plotted to overthrow palace eunuchs. He was discovered and killed, however, in the end 2,000 eunuchs were also killed. A series of generals attempted to control the young emperor, culminating in three spheres of influence. Cao Cao ruled the north, Sun Quan ruled the south, and Liu Bei controlled the west. After Cao Cao’s death, his son Cao Pi forced Emperor Xian to give up his throne to him. This ended the Han Dynasty, and started a period of conflict between these three states, called Cao Wei, Eastern Wu and Shu Han.

5.5.4: Invention of Paper

Paper was invented by Cai Lun during the Han Dynasty of ancient China. It was used for a variety of purposes, including wrapping and writing, and eventually spread throughout the world.

Learning Objective

Analyze the importance of paper and its invention

Key Points

- Cai Lun (202 BCE-220 CE), a Chinese official working in the Imperial court during the Han Dynasty, is attributed with the invention of paper.

- A basic process is still followed today that consists of creating felted sheets of fiber suspended in water, then draining the water and allowing the fibers to dry in a thin matted sheet.

- Early paper was used for wrapping and writing, as well as for toilet paper, tea bags, and napkins.