4.1: Introduction to Ancient Egypt

4.1.1: The Rise of Egyptian Civilization

In prehistoric times (pre-3200 BCE), many different cultures lived in Egypt along the Nile River, and became progressively more sedentary and reliant on agriculture. By the time of the Early Dynastic Period, these cultures had solidified into a single state.

Learning Objective

Describe the rise of civilization along the Nile River

Key Points

- The prehistory of Egypt spans from early human settlements to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt (c. 3100 BCE), and is equivalent to the Neolithic period.

- The Late Paleolithic in Egypt began around 30,000 BCE, and featured mobile buildings and tool-making industry.

- The Mesolithic saw the rise of various cultures, including Halfan, Qadan, Sebilian, and Harifian.

- The Neolithic saw the rise of cultures, including Merimde, El Omari, Maadi, Tasian, and Badarian.

- Three phases of Naqada culture included: the rise of new types of pottery (including blacktop-ware and white cross-line-ware), the use of mud-bricks, and increasingly sedentary lifestyles.

- During the Protodynastic period (3200-3000 BCE) powerful kings were in place, and unification of the state occurred, which led to the Early Dynastic Period.

Key Terms

- Neolithic

-

The later part of the Stone Age, during which ground or polished stone weapons and implements were used.

- nomadic pastoralism

-

The herding of livestock to find fresh pasture to graze.

- Fertile Crescent

-

Also known as the Cradle of Civilization, the Fertile Crescent is a crescent-shaped region containing the comparatively moist and fertile land of Western Asia, the Nile Valley, and the Nile Delta.

- serekhs

-

An ornamental vignette combining a view of a palace facade and a top view of the royal courtyard. It was used as a royal crest.

The prehistory of Egypt spans from early human settlements to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt (c. 3100 BCE), which started with the first Pharoah Narmer (also known as Menes). It is equivalent to the Neolithic period, and is divided into cultural periods, named after locations where Egyptian settlements were found.

The Late Paleolithic

This period began around 30,000 BCE. Ancient, mobile buildings, capable of being disassembled and reassembled were found along the southern border near Wadi Halfa. Aterian tool-making industry reached Egypt around 40,000 BCE, and Khormusan industry began between 40,000 and 30,000 BCE.

The Mesolithic

Halfan culture arose along the Nile Valley of Egypt and in Nubia between 18,000 and 15,000 BCE. They appeared to be settled people, descended from the Khormusan people, and spawned the Ibero-Marusian industry. Material remains from these people include stone tools, flakes, and rock paintings.

The Qadan culture practiced wild-grain harvesting along the Nile, and developed sickles and grinding stones to collect and process these plants. These people were likely residents of Libya who were pushed into the Nile Valley due to desiccation in the Sahara. The Sebilian culture (also known as Esna) gathered wheat and barley.

The Harifian culture migrated out of the Fayyum and the Eastern deserts of Egypt to merge with the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B; this created the Circum-Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex, who invented nomadic pastoralism, and may have spread Proto-Semitic language throughout Mesopotamia.

The Neolithic

Expansion of the Sahara desert forced more people to settle around the Nile in a sedentary, agriculture-based lifestyle. Around 6000 BCE, Neolithic settlements began to appear in great number in this area, likely as migrants from the Fertile Crescent returned to the area. Weaving occurred for the first time in this period, and people buried their dead close to or within their settlements.

The Merimde culture (5000-4200 BCE) was located in Lower Egypt. People lived in small huts, created simple pottery, and had stone tools. They had cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs, and planted wheat, sorghum, and barley. The first Egyptian life-size clay head comes from this culture.

The El Omari culture (4000-3100 BCE) lived near modern-day Cairo. People lived in huts, and had undecorated pottery and stone tools. Metal was unknown.

The Maadi culture (also known as Buto Maadi) is the most important Lower Egyptian prehistoric culture. Copper was used, pottery was simple and undecorated, and people lived in huts. The dead were buried in cemeteries.

The Tasian culture (4500-3100 BCE) produced a kind of red, brown, and black pottery, called blacktop-ware. From this period on, Upper Egypt was strongly influenced by the culture of Lower Egypt.

The Badarian culture (4400-4000 BCE) was similar to the Tasian, except they improved blacktop-ware and used copper in addition to stone.

The Amratian culture (Naqada I) (4000-3500 BCE) continued making blacktop-ware, and added white cross-line-ware, which featured pottery with close, parallel, white, crossed lines. Mud-brick buildings were first seen in this period in small numbers.

Amratian (Naqada I) Terracotta Figure

This terracotta female figure, c. 3500-3400 BCE, is housed at the Brooklyn Museum.

The Gerzean culture (Naqada II, 3500-3200 BCE) saw the laying of the foundation for Dynastic Egypt. It developed out of Amratian culture, moving south through Upper Egypt. Its pottery was painted dark red with pictures of animals, people and ships. Life was increasingly sedentary and focused on agriculture, as cities began to grow. Mud bricks were mass-produced, copper was used for tools and weapons, and silver, gold, lapis, and faience were used as decorations. The first Egyptian-style tombs were built.

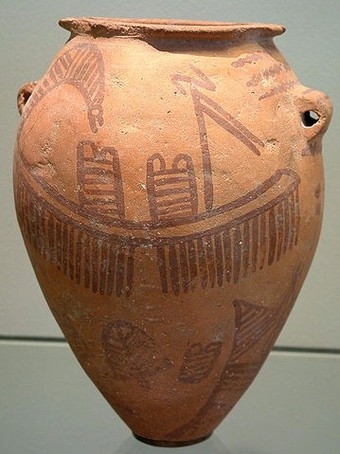

Naqada II Pottery

This pottery has a ship theme, and is done in the style of Naqada II.

Protodynastic Period (Naqada III) (3200 – 3000 BCE)

During this period, the process of state formation, begun in Naqada II, became clearer. Kings headed up powerful polities, but they were unrelated. Political unification was underway, which culminated in the formation of a single state in the Early Dynastic Period. Hieroglyphs may have first been used in this period, along with irrigation. Additionally, royal cemeteries and serekhs (royal crests) came into use.

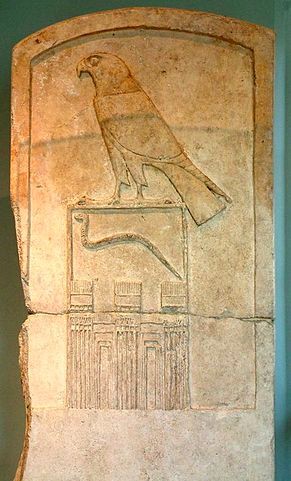

Serekh of King Djet

This serekh (royal crest) shows the Horus falcon.

4.2: The Old Kingdom

4.2.1: The Old Kingdom

The Old Kingdom, spanning the Third to Sixth Dynasties of Egypt (2686-2181 BCE), saw the prolific construction of pyramids, but declined due to civil instability, resource shortages, and a drop in precipitation.

Learning Objective

Explain the reasons for the rise and fall of the Old Kingdom

Key Points

- The Old Kingdom is the name commonly given to the period when Egypt gained in complexity and achievement, spanning from the Third Dynasty through the Sixth Dynasty (2686-2181 BCE).

- The royal capital of Egypt during the Old Kingdom was located at Memphis, where the first notable king of the Old Kingdom, Djoser, established his court.

- In the Third Dynasty, formerly independent ancient Egyptian states became known as Nomes, which were ruled solely by the pharaoh. The former rulers of these states were subsequently forced to assume the role of governors, or otherwise work in tax collection.

- Egyptians during this Dynasty worshipped their pharaoh as a god, and believed that he ensured the stability of the cycles that were responsible for the annual flooding of the Nile. This flooding was necessary for their crops.

- The Fourth Dynasty saw multiple large-scale construction projects under pharaohs Sneferu, Khufu, and Khufu’s sons Djedefra and Khafra, including the famous pyramid and Sphinx at Giza.

- The Fifth Dynasty saw changes in religious beliefs, including the rise of the cult of the sun god Ra, and the deity Osiris.

- The Sixth Dynasty saw civil war and the loss of centralized power to nomarchs.

Key Terms

- Ra

-

The sun god, or the supreme Egyptian deity, worshipped as the creator of all life, and usually portrayed with a falcon’s head bearing a solar disc.

- Osiris

-

The Egyptian god of the underworld, and husband and brother of Isis.

- Nomes

-

Subnational, administrative division of Ancient Egypt.

- nomarchs

-

Semi-feudal rulers of Ancient Egyptian provinces.

- Old Kingdom

-

Encompassing the Third to Eighth Dynasties, the name commonly given to the period in the 3rd millennium BCE, when Egypt attained its first continuous peak of complexity and achievement.

- Djoser

-

An ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the Third Dynasty, and the founder of the Old Kingdom.

- necropolis

-

A cemetery, especially a large one belonging to an ancient city.

- Sneferu

-

A king of the Fourth Dynasty, who used the greatest mass of stones in building pyramids.

The Old Kingdom is the name commonly given to the period from the Third Dynasty through the Sixth Dynasty (2686-2181 BCE), when Egypt gained in complexity and achievement. The Old Kingdom is the first of three so-called “Kingdom” periods that mark the high points of civilization in the Nile Valley. During this time, a new type of pyramid (the step) was created, as well as many other massive building projects, including the Sphinx. Additionally, trade became more widespread, new religious ideas were born, and the strong centralized government was subtly weakened and finally collapsed.

The king (not yet called Pharaoh) of Egypt during this period resided in the new royal capital, Memphis. He was considered a living god, and was believed to ensure the annual flooding of the Nile. This flooding was necessary for crop growth. The Old Kingdom is perhaps best known for a large number of pyramids, which were constructed as royal burial places. Thus, the period of the Old Kingdom is often called “The Age of the Pyramids.”

Egypt’s Old Kingdom was also a dynamic period in the development of Egyptian art. Sculptors created early portraits, the first life-size statues, and perfected the art of carving intricate relief decoration. These had two principal functions: to ensure an ordered existence, and to defeat death by preserving life in the next world.

The Beginning: Third Dynasty (c. 2650-2613 BCE)

The first notable king of the Old Kingdom was Djoser (reigned from 2691-2625 BCE) of the Third Dynasty, who ordered the construction of the step pyramid in Memphis’ necropolis, Saqqara. It was in this era that formerly independent ancient Egyptian states became known as nomes, and were ruled solely by the king. The former rulers of these states were forced to assume the role of governors or tax collectors.

Golden Age: Fourth Dynasty (2613-2494 BCE)

The Old Kingdom and its royal power reached a zenith under the Fourth Dynasty, which began with Sneferu (2613-2589 BCE). Using a greater mass of stones than any other king, he built three pyramids: Meidum, the Bent Pyramid, and the Red Pyramid. He also sent his military into Sinai, Nubia and Libya, and began to trade with Lebanon for cedar.

Sneferu was succeeded by his (in)famous son, Khufu (2589-2566 BCE), who built the Great Pyramid of Giza. After Khufu’s death, one of his sons built the second pyramid, and the Sphinx in Giza. Creating these massive projects required a centralized government with strong powers, sophistication and prosperity. Builders of the pyramids were not slaves but peasants, working in the farming off-season, along with specialists like stone cutters, mathematicians, and priests. Each household needed to provide a worker for these projects, although the wealthy could have a substitute.

The Pyramid of Khufu at Giza

The Great Pyramid of Giza was built c. 2560 BCE, by Khufu during the Fourth Dynasty. It was built as a tomb for Khufu and constructed over a 20-year period. Modern estimates place construction efforts to require an average workforce of 14,567 people and a peak workforce of 40,000.

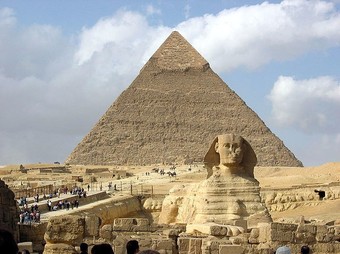

Great Sphinx of Giza and the pyramid of Khafre

The Sphinx is a limestone statue of a reclining mythical creature with a lion’s body and a human head that stands on the Giza Plateau on the west bank of the Nile in Giza, Egypt. The face is generally believed to represent the face of King Khafra.

The later kings of the Fourth Dynasty were king Menkaura (2532-2504 BCE), who built the smallest pyramid in Giza, Shepseskaf (2504-2498 BCE), and perhaps Djedefptah (2498-2496 BCE). During this period, there were military expeditions into Canaan and Nubia, spreading Egyptian influence along the Nile into modern-day Sudan.

Religious Changes: Fifth Dynasty (2494-2345 BCE)

The Fifth Dynasty began with Userkaf (2494-2487 BCE), and with several religious changes. The cult of the sun god Ra, and temples built for him, began to grow in importance during the Fifth Dynasty. This lessened efforts to build pyramids. Funerary prayers on royal tombs (called Pyramid Texts) appeared, and the cult of the deity Osiris ascended in importance.

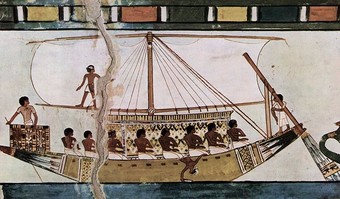

Egyptians began to build ships to trade across maritime routes. Goods included ebony, incense, gold, and copper. They traded with Lebanon for cedar, and perhaps with modern-day Somalia for other goods. Ships were held together by tightly tied ropes.

Decline and Collapse: The Sixth Dynasty (2345-2181 BCE)

The power of the king and central government declined during this period, while that of nomarchs (regional governors) increased. These nomarchs were not part of the royal family. They passed down the title through their lineage, thus creating local dynasties that were not under the control of the king. Internal disorder resulted during and after the long reign of Pepi II (2278-2184 BCE), due to succession struggles, and eventually led to civil war. The final blow was a severe drought between 2200-2150 BCE, which prevented Nile flooding. Famine, conflict, and collapse beset the Old Kingdom for decades.

4.2.2: The First Intermediate Period

The First Intermediate Period, the Seventh to Eleventh dynasties, spanned approximately one hundred years (2181-2055 BCE), and was characterized by political instability and conflict between the Heracleopolitan and Theban Kings.

Learning Objective

Describe the processes by which the First Intermediate Period occurred, and then transitioned into the Middle Kingdom

Key Points

- The First Intermediate Period was a dynamic time in history, when rule of Egypt was roughly divided between two competing power bases. One of those bases resided at Heracleopolis in Lower Egypt, a city just south of the Faiyum region. The other resided at Thebes in Upper Egypt.

- The Old Kingdom fell due to problems with succession from the Sixth Dynasty, the rising power of provincial monarchs, and a drier climate that resulted in widespread famine.

- Little is known about the Seventh and Eighth Dynasties due to a lack of evidence, but the Seventh Dynasty was most likely an oligarchy, while Eighth Dynasty rulers claimed to be the descendants of the Sixth Dynasty kings. Both ruled from Memphis.

- The Heracleopolitan Kings saw periods of both violence and peace under their rule, and eventually brought peace and order to the Nile Delta region.

- Siut princes to the south of the Heracleopolitan Kingdom became wealthy from a variety of agricultural and economic activities, and acted as a buffer during times of conflict between the northern and southern parts of Egypt.

- The Theban Kings enjoyed a string of military successes, the last of which was a victory against the Heracleopolitan Kings that unified Egypt under the Twelfth Dynasty.

Key Terms

- First Intermediate Period

-

A period of political conflict and instability lasting approximately 100 years and spanning the Seventh to Eleventh Dynasties.

- Mentuhotep II

-

A pharaoh of the Eleventh Dynasty, who defeated the Heracleopolitan Kings and unified Egypt. Often considered the first pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom.

- nomarchs

-

Ancient Egyptian administration officials responsible for governing the provinces.

- oligarchy

-

A form of power structure in which power effectively rests with a small number of people who are distinguished by royalty, wealth, family ties, education, corporate, or military control.

The First Intermediate Period (c. 2181-2055 BCE), often described as a “dark period” in ancient Egyptian history after the end of the Old Kingdom, spanned approximately 100 years. It included the Seventh, Eighth, Ninth, Tenth, and part of the Eleventh dynasties.

The First Intermediate Period was a dynamic time in history when rule of Egypt was roughly divided between two competing power bases: Heracleopolis in Lower Egypt, and Thebes in Upper Egypt. It is believed that political chaos during this time resulted in temples being pillaged, artwork vandalized, and statues of kings destroyed. These two kingdoms eventually came into military conflict. The Theban kings conquered the north, which resulted in the reunification of Egypt under a single ruler during the second part of the Eleventh dynasty.

Events Leading to the First Intermediate Period

The Old Kingdom, which preceded this period, fell for numerous reasons. One was the extremely long reign of Pepi II (the last major king of the Sixth Dynasty), and the resulting succession issues. Another major problem was the rise in power of the provincial nomarchs. Toward the end of the Old Kingdom, the positions of the nomarchs had become hereditary, creating family legacies independent from the king. They erected tombs in their own domains and often raised armies, and engaged in local rivalries. A third reason for the dissolution of centralized kingship was the low level of the Nile inundation, which may have resulted in a drier climate, lower crop yields, and famine.

The Seventh and Eighth Dynasties at Memphis

The Seventh and Eighth dynasties are often overlooked because very little is known about the rulers of these two periods. The Seventh Dynasty was most likely an oligarchy based in Memphis that attempted to retain control of the country. The Eighth Dynasty rulers, claiming to be the descendants of the Sixth Dynasty kings, also ruled from Memphis.

The Heracleopolitan Kings

After the obscure reign of the Seventh and Eighth dynasty kings, a group of rulers rose out of Heracleopolis in Lower Egypt, and ruled for approximately 94 years. These kings comprise the Ninth and Tenth Dynasties, each with 19 rulers.

The founder of the Ninth Dynasty, Wahkare Khety I, is often described as an evil and violent ruler who caused much harm to the inhabitants of Egypt. He was seized with madness, and, as legend would have it, was eventually killed by a crocodile. Kheti I was succeeded by Kheti II, also known as Meryibre, whose reign was essentially peaceful but experienced problems in the Nile Delta. His successor, Kheti III, brought some degree of order to the Delta, although the power and influence of these Ninth Dynasty kings were still insignificant compared to that of the Old Kingdom kings.

A distinguished line of nomarchs rose out of Siut (or Asyut), which was a powerful and wealthy province in the south of the Heracleopolitan kingdom. These warrior princes maintained a close relationship with the kings of the Heracleopolitan royal household, as is evidenced by the inscriptions in their tombs. These inscriptions provide a glimpse at the political situation that was present during their reigns, and describe the Siut nomarchs digging canals, reducing taxation, reaping rich harvests, raising cattle herds, and maintaining an army and fleet. The Siut province acted as a buffer state between the northern and southern rulers and bore the brunt of the attacks from the Theban kings.

The Theban Kings

The Theban kings are believed to have been descendants of Intef or Inyotef, the nomarch of Thebes, often called the “Keeper of the Door of the South. ” He is credited with organizing Upper Egypt into an independent ruling body in the south, although he himself did not appear to have tried to claim the title of king. Intef II began the Theban assault on northern Egypt, and his successor, Intef III, completed the attack and moved into Middle Egypt against the Heracleopolitan kings. The first three kings of the Eleventh Dynasty (all named Intef) were, therefore, also the last three kings of the First Intermediate Period. They were succeeded by a line of kings who were all called Mentuhotep. Mentuhotep II, also known as Nebhepetra, would eventually defeat the Heracleopolitan kings around 2033 BCE, and unify the country to continue the Eleventh Dynasty and bring Egypt into the Middle Kingdom.

Mentuhotep II

Painted sandstone seated statue of Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II, Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

4.3: The Middle Kingdom

4.3.1: The Middle Kingdom

The Middle Kingdom was a period of Egyptian history spanning the Eleventh through Twelfth Dynasty (2000-1700 BCE), when centralized power consolidated a unified Egypt.

Learning Objective

Describe the various characteristics of Sensuret III’s rule during the height of the Middle Kingdom

Key Points

- The Middle Kingdom had two phases: the end of the Eleventh Dynasty, which ruled from Thebes, and the Twelfth Dynasty onwards, which was centred around el-Lisht.

- During the First Intermediate Period, the governors of the nomes of Egypt—

called nomarchs—

gained considerable power. Amenemhet I also instituted a system of co-regency, which ensured a smooth transition from monarch to monarch and contributed to the stability of the Twelfth Dynasty.

- The height of the Middle Kingdom came under the rules of Sensuret III and Amenemhat III, the former of whom established clear boundaries for Egypt, and the latter of whom efficiently exploited Egyptian resources to bring about a period of economic prosperity.

- The Middle Kingdom declined into the Second Intermediate Period during the Thirteenth Dynasty, after a gradual loss of dynastic power and the disintegration of Egypt.

Key Terms

- Amenemhat III

-

Egyptian king who saw a great period of economic prosperity through efficient exploitation of natural resources.

- nomes

-

Subnational administrative divisions within ancient Egypt.

- Middle Kingdom

-

Period of unification in Ancient Egyptian history, stretching from the end of the Eleventh Dynasty to the Thirteenth Dynasty, roughly between 2030-1640 BCE.

- Senusret III

-

Warrior-king during the Twelfth Dynasty, who centralized power within Egypt through various military successes.

- Sobekneferu,

-

The first known female ruler of Egypt.

- waret

-

Administrative divisions in Egypt.

- genut

The Middle Kingdom, also known as the Period of Reunification, is a period in the history of Ancient Egypt stretching from the end of the Eleventh Dynasty to the end of the Twelfth Dynasty, roughly between 2000-1700 BCE. There were two phases: the end of the Eleventh Dynasty, which ruled from Thebes, and the Twelfth Dynasty onwards, which was centred around el-Lisht.

The End of the Eleventh Dynasty and the Rise of the Twelfth Dynasty

Toward the end of the First Intermediate Period, Mentuhotep II and his successors unified Egypt under a single rule, and commanded such faraway locations as Nubia and the Sinai. He reigned for 51 years and restored the cult of the ruler, considering himself a god and wearing the headdresses of Amun and Min. His descendants ruled Egypt, until a vizier, Amenemhet I, came to power and initiated the Twelfth Dynasty.

From the Twelfth dynasty onward, pharaohs often kept well-trained standing armies, which formed the basis of larger forces raised for defense against invasion, or for expeditions up the Nile or across the Sinai. However, the Middle Kingdom remained defensive in its military strategy, with fortifications built at the First Cataract of the Nile, in the Delta and across the Sinai Isthmus.

Amenemhet I never held the absolute power commanded, in theory, by the Old Kingdom pharaohs. During the First Intermediate Period, the governors of the nomes of Egypt—

nomarchs—gained considerable power. To strengthen his position, Amenemhet required registration of land, modified nome borders, and appointed nomarchs directly when offices became vacant. Generally, however, he acquiesced to the nomarch system, creating a strongly feudal organization.

In his 20th regnal year, Amenemhat established his son, Senusret I, as his co-regent. This instituted a practice that would be used throughout the Middle and New Kingdoms. The reign of Amenemhat II, successor to Senusret I, has been characterized as largely peaceful. It appears Amenemhet allowed nomarchs to become hereditary again. In his 33rd regnal year, he appointed his son, Senusret II, co-regent.

There is no evidence of military activity during the reign of Senusret II. Senusret instead appears to have focused on domestic issues, particularly the irrigation of the Faiyum. He reigned only fifteen years, and was succeeded by his son, Senusret III.

Height of the Middle Kingdom

Senusret III was a warrior-king, and launched a series of brutal campaigns in Nubia. After his victories, Senusret built a series of massive forts throughout the country as boundary markers; the locals were closely watched.

Statue head of Sensuret III

Statue head of Sensuret III, one of the kings in the Twelfth Dynasty.

Domestically, Senusret has been given credit for an administrative reform that put more power in the hands of appointees of the central government. Egypt was divided into three warets, or administrative divisions: North, South, and Head of the South (perhaps Lower Egypt, most of Upper Egypt, and the nomes of the original Theban kingdom during the war with Herakleopolis, respectively). The power of the nomarchs seems to drop off permanently during Sensuret’s reign, which has been taken to indicate that the central government had finally suppressed them, though there is no record that Senusret took direct action against them.

The reign of Amenemhat III was the height of Middle Kingdom economic prosperity, and is remarkable for the degree to which Egypt exploited its resources. Mining camps in the Sinai, that had previously been used only by intermittent expeditions, were operated on a semi-permanent basis. After a reign of 45 years, Amenemhet III was succeeded by Amenemhet IV, under whom dynastic power began to weaken. Contemporary records of the Nile flood levels indicate that the end of the reign of Amenemhet III was dry, and crop failures may have helped to destabilize the dynasty. Furthermore, Amenemhet III had an inordinately long reign, which led to succession problems. Amenemhet IV was succeeded by Sobekneferu, the first historically attested female king of Egypt, who ruled for no more than four years. She apparently had no heirs, and when she died the Twelfth Dynasty came to a sudden end.

Decline into the Second Intermediate Period

After the death of Sobeknefru, Egypt was ruled by a series of ephemeral kings for about 10-15 years. Ancient Egyptian sources regard these as the first kings of the Thirteenth Dynasty.

After the initial dynastic chaos, a series of longer reigning, better attested kings ruled for about 50-80 years. The strongest king of this period, Neferhotep I, ruled for 11 years, maintained effective control of Upper Egypt, Nubia, and the Delta, and was even recognized as the suzerain of the ruler of Byblos. At some point during the Thirteenth Dynasty, the provinces of Xois and Avaris began governing themselves. Thus began the final portion of the Thirteenth Dynasty, when southern kings continued to reign over Upper Egypt; when the unity of Egypt fully disintegrated, however, the Middle Kingdom gave way to the Second Intermediate Period.

4.3.2: The Second Intermediate Period

The Second Intermediate Period (c. 1650-1550 BCE) spanned the Fourteenth to Seventeenth Dynasties, and was a period in which decentralized rule split Egypt between the Theban-based Seventeenth Dynasty in Upper Egypt and the Sixteenth Dynasty under the Hyksos in the north.

Learning Objective

Explain the dynamics between the various groups of people vying for power during the Second Intermediate Period

Key Points

- The brilliant Twelfth Dynasty was succeeded by a weaker Thirteenth Dynasty, which experienced a splintering of power.

- The Hyksos made their first appearance during the reign of Sobekhotep IV, and overran Egypt at the end of the Fourteenth Dynasty. They ruled through the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Dynasties.

- The Abydos Dynasty was a short-lived Dynasty that ruled over part of Upper Egypt, and was contemporaneous with the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Dynasties.

- The Seventeeth Dynasty established itself in Thebes around the time that the Hyksos took power in Egypt, and co-existed with the Hyksos through trade for a period of time. However, rulers from the Seventeenth Dynasty undertook several wars of liberation that eventually once again unified Egypt in the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Key Terms

- Hyksos

-

An Asiatic people from West Asia who took over the eastern Nile Delta, ending the Thirteenth dynasty of Egypt and initiating the Second Intermediate Period.

- Abydos Dynasty

-

A short-lived local dynasty ruling over parts of Upper Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period in Ancient Egypt.

- Baal

-

The native storm god of the Hyksos.

- Second Intermediate Period

-

Spanning the Fourteenth to Seventeenth Dynasties, a period of Egyptian history where power was split between the Hyksos and a Theban-based dynasty in Upper Egypt.

The Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782-1550 BCE) marks a time when Ancient Egypt once again fell into disarray between the end of the Middle Kingdom, and the start of the New Kingdom. It is best known as the period when the Hyksos, who reigned during the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Dynasties, made their appearance in Egypt.

The Thirteenth Dynasty (1803 – 1649 BCE)

The brilliant Egyptian Twelfth Dynasty—

and the Golden Age of the Middle Kingdom— came to an end around 1800 BCE with the death of Queen Sobekneferu (1806-1802 BCE), and was succeeded by the much weaker Thirteenth Dynasty (1803-1649 BCE). Pharoahs ruled from Memphis until the Hyksos conquered the capital in 1650 BCE.

The Fourteenth Dynasty (c. 1725-1650 BCE)

The Thirteenth Dynasty proved unable to hold onto the long land of Egypt, and the provincial ruling family in Xois, located in the marshes of the western Delta, broke away from the central authority to form the Fourteenth Dynasty. The capital of this dynasty was likely Avaris. It existed concurrently with the Thirteenth Dynasty, and its rulers seemed to be of Canaanite or West Semitic descent.

Fourteenth Dynasty Territory

The area in orange is the territory possibly under control of the Fourteenth Dynasty.

The Fifteenth Dynasty (c. 1650-1550 BCE)

The Hyksos made their first appearance in 1650 BCE and took control of the town of Avaris. They would also conquer the Sixteenth Dynasty in Thebes and a local dynasty in Abydos (see below). The Hyksos were of mixed Asiatic origin with mainly Semitic components, and their native storm god, Baal, became associated with the Egyptian storm god Seth. They brought technological innovation to Egypt, including bronze and pottery techniques, new breeds of animals and new crops, the horse and chariot, composite bow, battle-axes, and fortification techniques for warfare. These advances helped Egypt later rise to prominence.

Luxor Temple

Thebes was the capital of many of the Sixteenth Dynasty pharaohs.

The Sixteenth Dynasty

This dynasty ruled the Theban region in Upper Egypt for 70 years, while the armies of the Fifteenth Dynasty advanced against southern enemies and encroached on Sixteenth territory. Famine was an issue during this period, most notably during the reign of Neferhotep III.

The Abydos Dynasty

The Abydos Dynasty was a short-lived local dynasty that ruled over part of Upper Egypt and was contemporaneous with the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Dynasties c. 1650-1600 BCE. The royal necropolis of the Abydos Dynasty was found in the southern part of Abydos, in an area called Anubis Mountain in ancient times, adjacent to the tombs of the Middle Kingdom rulers.

The Abydos Dynasty

This map shows the possible extent of power of the Abydos Dynasty (in red).

The Seventeenth Dynasty (c. 1580-1550 BCE)

Around the time Memphis and Itj-tawy fell to the Hyksos, the native Egyptian ruling house in Thebes declared its independence from Itj-tawy and became the Seventeenth Dynasty. This dynasty would eventually lead the war of liberation that drove the Hyksos back into Asia. The Theban-based Seventeenth Dynasty restored numerous temples throughout Upper Egypt while maintaining peaceful trading relations with the Hyksos kingdom in the north. Indeed, Senakhtenre Ahmose, the first king in the line of Ahmoside kings, even imported white limestone from the Hyksos-controlled region of Tura to make a granary door at the Temple of Karnak. However, his successors—the final two kings of this dynasty—,Seqenenre Tao and Kamose, defeated the Hyksos through several wars of liberation. With the creation of the Eighteenth Dynasty around 1550 BCE, the New Kingdom period of Egyptian history began with Ahmose I, its first pharaoh, who completed the expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt and placed the country, once again, under centralized administrative control.

4.4: The New Kingdom

4.4.1: The New Kingdom

The New Kingdom of Egypt spanned the Eighteenth to Twentieth Dynasties (c. 1550-1077 BCE), and was Egypt’s most prosperous time. It was ruled by pharaohs Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Akhenaten, Tutankhamun and Ramesses II.

Learning Objective

Explain the reasons for the collapse of the New Kingdom

Key Points

- The New Kingdom saw Egypt attempt to create a buffer against the Levant and by attaining its greatest territorial by extending into Nubia and the Near East. This was possibly a result of the foreign rule of the Hyksos during the Second Intermediate Period,

- The Eighteenth Dynasty contained some of Egypt’s most famous pharaohs, including Hatshepsut, Akhenaten, Thutmose III, and Tutankhamun. Hatshepsut concentrated on expanding Egyptian trade, while Thutmose III consolidated power.

- Akhenaten’s devotion to Aten defined his reign with religious fervor, while art flourished under his rule and attained an unprecedented level of realism.

- Due to Akenaten’s lack of interest in international affairs, the Hittites gradually extended their influence into Phoenicia and Canaan.

- Ramesses II attempted war against the Hittites, but eventually agreed to a peace treaty after an indecisive result.

- The heavy cost of military efforts in addition to climatic changes resulted in a loss of centralized power at the end of the Twentieth Dynasty, leading to the Third Intermediate Period.

Key Terms

- New Kingdom

-

The period in ancient Egyptian history between the 16th century BCE and the 11th century BCE that covers the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties of Egypt. Considered to be the peak of Egyptian power.

- Thutmose III

-

The sixth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty, who greatly consolidated political power through a series of military conquests.

- Akhenaten

-

Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty known for his religious fervor to the god Aten.

- Hatshepsut

-

The fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty, who expanded Egyptian trade.

- Tutankhamun

-

An Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th dynasty (ruled c. 1332 BC-1323 BC in the conventional chronology), during the period of Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom. He is popularly referred to as King Tut.

- Aten

-

The disk of the sun in ancient Egyptian mythology, and originally an aspect of Ra.

- Ramesses II

-

The third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, who made peace with the Hittites. Often regarded as the greatest, most celebrated, and most powerful pharaoh of the Egyptian Empire.

The New Kingdom of Egypt, also referred to as the Egyptian Empire, is the period in ancient Egyptian history between 1550-1070 BCE, covering the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties of Egypt. The New Kingdom followed the Second Intermediate Period, and was succeeded by the Third Intermediate Period. It was Egypt’s most prosperous time and marked the peak of its power.

The Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties (1292-1069 BCE) are also known as the Ramesside period, after the eleven pharaohs that took the name of Ramesses. The New Kingdom saw Egypt attempt to create a buffer against the Levant and attain its greatest territorial extent. This was possibly a result of the foreign rule of the Hyksos during the Second Intermediate Period

The Eighteenth Dynasty (c. 1543-1292 BCE)

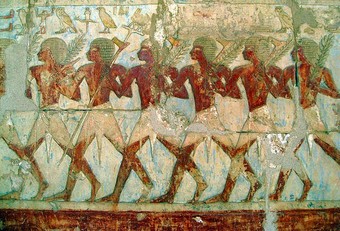

The Eighteenth Dynasty, also known as the Thutmosid Dynasty, contained some of Egypt’s most famous pharaohs, including Ahmose I, Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, Akhenaten (c. 1353-1336 BCE) and his queen Nefertiti, and Tutankhamun. Queen Hatshepsut (c. 1479 – 1458 BCE) concentrated on expanding Egypt’s external trade by sending a commercial expedition to the land of Punt, and was the longest-reigning woman pharaoh of an indigenous dynasty. Thutmose III, who would become known as the greatest military pharoah, expanded Egypt’s army and wielded it with great success to consolidate the empire created by his predecessors. These victories maximized Egyptian power and wealth during the reign of Amenhotep III. It was also during the reign of Thutmose III that the term “pharaoh,” originally referring to the king’s palace, became a form of address for the king.

One of the best-known Eighteenth Dynasty pharaohs is Amenhotep IV (c. 1353-1336 BCE), who changed his name to Akhenaten in honor of Aten and whose exclusive worship of the deity is often interpreted as the first instance of monotheism. Under his reign Egyptian art flourished and attained an unprecedented level of realism. Toward the end of this dynasty, the Hittites had expanded their influence into Phoenicia and Canaan, the outcome of which would be inherited by the rulers of the Nineteenth Dynasty.

Bust of Akhenaten

Akhenaten, born Amenhotep IV, was the son of Queen Tiye. He rejected the old Egyptian religion and promoted the Aten as a supreme deity.

The Nineteenth Dynasty (c. 1292-1187 BCE)

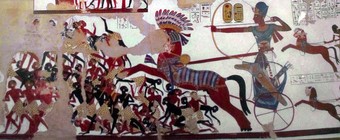

New Kingdom Egypt would reach the height of its power under Seti I and Ramesses II, who fought against the Libyans and Hittites. The city of Kadesh was a flashpoint, captured first by Seti I and then used as a peace bargain with the Hatti, and later attacked again by Ramesses II. Eventually, the Egyptians and Hittites signed a lasting peace treaty.

Egyptian and Hittite Empires

This map shows the Egyptian (green) and Hittite (red) Empires around 1274 BCE.

Ramesses II had a large number of children, and he built a massive funerary complex for his sons in the Valley of the Kings. The Nineteenth Dynasty ended in a revolt led by Setnakhte, the founder of the Twentieth Dynasty.

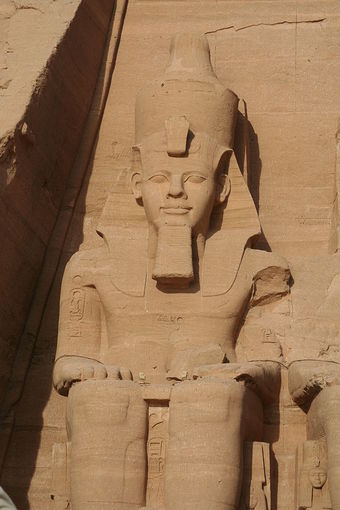

Temple of Ramesses II

Detail of the Temple of Ramesses II.

The Twentieth Dynasty (c. 1187-1064 BCE)

The last “great” pharaoh from the New Kingdom is widely regarded to be Ramesses III. In the eighth year of his reign, the Sea Peoples invaded Egypt by land and sea, but were defeated by Ramesses III.

The heavy cost of warfare slowly drained Egypt’s treasury and contributed to the gradual decline of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. The severity of the difficulties is indicated by the fact that the first known labor strike in recorded history occurred during the 29th year of Ramesses III’s reign, over food rations. Despite a palace conspiracy which may have killed Ramesses III, three of his sons ascended the throne successively as Ramesses IV, Ramesses VI and Ramesses VIII. Egypt was increasingly beset by droughts, below-normal flooding of the Nile, famine, civil unrest, and official corruption. The power of the last pharaoh of the dynasty, Ramesses XI, grew so weak that, in the south, the High Priests of Amun at Thebes became the de facto rulers of Upper Egypt. The Smendes controlled Lower Egypt even before Ramesses XI’s death. Menes eventually founded the Twenty-first Dynasty at Tanis.

4.4.2: Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut ruled Egypt in the Eighteenth Dynasty (1478-1458 BCE), and brought wealth and a focus on large building projects. She was one of just a handful of female rulers.

Learning Objective

Describe the achievements of Hatshepsut in Ancient Egypt

Key Points

- Hatshepsut reigned Egypt from 1478-1458 BCE, during the Eighteenth Dynasty. She ruled longer than any other woman of an indigenous Egyptian dynasty.

- Hatshepsut established trade networks that helped build the wealth of the Eighteenth Dynasty.

- Hundreds of construction projects and statuary were commissioned by Hatshepsut, including obelisks and monuments at the Temple of Karnak.

- While not the first female ruler of Egypt, Hatshepsut’s reign was longer and more prosperous; she oversaw a peaceful, wealthy era.

- The average woman in Egypt was quite liberated for the time, and had a variety of property and other rights.

- Hatshepsut died in 1458 BCE in middle age, possibly of diabetes and bone cancer. Her mummy was discovered in 1903 and identified in 2007.

Key Terms

- kohl

-

A black powder used as eye makeup.

- obelisks

-

Stone pillars, typically having a square or rectangular cross section and a pyramidal tip, used as a monument.

- co-regent

-

The situation wherein a monarchical position, normally held by one person, is held by two.

Hatshepsut reigned in Egypt from 1478-1458 BCE, during the Eighteenth Dynasty, longer than any other woman of an indigenous Egyptian dynasty. According to Egyptologist James Henry Breasted, she was “the first great woman in history of whom we are informed.” She was the daughter of Thutmose I and his wife Ahmes. Hatshepsut’s husband, Thutmose II, was also a child of Thutmose I, but was conceived with a different wife. Hatshepsut had a daughter named Neferure with her husband, Thutmose II. Thutmose II also fathered Thutmose III with Iset, a secondary wife. Hatshepsut ascended to the throne as co-regent with Thutmose III, who came to the throne as a two-year old child.

Statue of Hatshepsut

This statue of Hatshepsut is housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Trade Networks

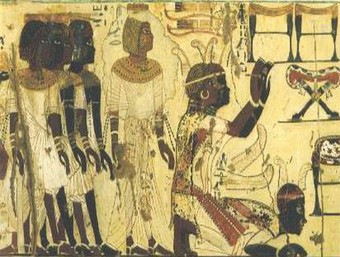

Hatshepsut established trade networks that helped build the wealth of the Eighteenth Dynasty. This included a successful mission to the Land of Punt in the ninth year of her reign, which brought live myrrh trees and frankincense (which Hatshepsut used as kohl eyeliner) to Egypt. She also sent raiding expeditions to Byblos and Sinai, and may have led military campaigns against Nubia and Canaan.

Building Projects

Hatshepsut was a prolific builder, commissioning hundreds of construction projects and statuary. She had monuments constructed at the Temple of Karnak, and restored the original Precinct of Mut at Karnak, which had been ravaged during the Hyksos occupation of Egypt. She installed twin obelisks (the tallest in the world at that time) at the entrance to this temple, one of which still stands. Karnak’s Red Chapel was intended as a shrine to her life, and may have stood with these obelisks.

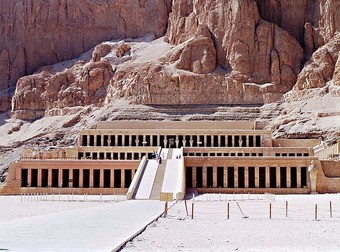

The Temple of Pakhet was a monument to Bast and Sekhmet, lioness war goddesses. Later in the Nineteenth Dynasty, King Seti I attempted to take credit for this monument. However, Hatshepsut’s masterpiece was a mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri; the focal point was the Djeser-Djeseru (“the Sublime of Sublimes”), a colonnaded structure built 1,000 years before the Greek Parthenon. The Hatshepsut needle, a granite obelisk, is considered another great accomplishment.

Hatshepsut Temple

The colonnaded design is evident in this temple.

Female Rule

Hatshepsut was not the first female ruler of Egypt. She had been preceded by Merneith of the First Dynasty, Nimaathap of the Third Dynasty, Nitocris of the Sixth Dynasty, Sobekneferu of the Twelfth Dynasty, Ahhotep I of the Seventeenth Dynasty, Ahmose-Nefertari, and others. However, Hatshepsut’s reign was longer and more prosperous; she oversaw a peaceful, wealthy era. She was also proficient at self-promotion, which was enabled by her wealth.

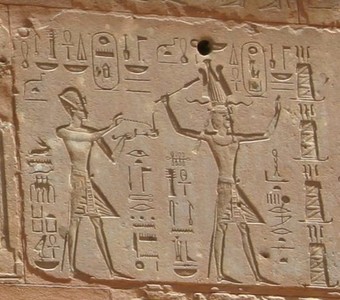

Hieroglyphs of Thutmose III and Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut, on the right, is shown having the trappings of a greater role.

The word “king” was considered gender-neutral, and women could take the title. During her father’s reign, she held the powerful office of God’s Wife, and as wife to her husband, Thutmose II, she took an active role in administration of the kingdom. As pharaoh, she faced few challenges, even from her co-regent, who headed up the powerful Egyptian army and could have unseated her, had he chosen to do so.

Women’s Status in Egypt

The average woman in Egypt was quite liberated for the time period. While her foremost role was as mother and wife, an average woman might have worked in weaving, perfume making, or entertainment. Women could own their own businesses, own and sell property, serve as witnesses in court cases, be in the company of men, divorce and remarry, and have access to one-third of their husband’s property.

Hatshepsut’s Death

Hatshepsut died in 1458 BCE in middle age; no cause of death is known, although she may have had diabetes and bone cancer, likely from a carcinogenic skin lotion. Her mummy was discovered in the Valley of the Kings by Howard Carer in 1903, although at the time, the mummy’s identity was not known. In 2007, the mummy was found to be a match to a missing tooth known to have belonged to Hatshepsut.

Osirian Statues of Hatshepsut

These statues of Hatshepsut at her tomb show her holding the crook and flail associated with Osiris.

After her death, mostly during Thutmose III’s reign, haphazard attempts were made to remove Hatshepsut from certain historical and pharaonic records. Amenhotep II, the son of Thutmose III, may have been responsible. The Tyldesley hypothesis states that Thutmose III may have decided to attempt to scale back Hatshepsut’s role to that of regent rather than king.

4.4.3: The Third Intermediate Period

The Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069-664 BCE) spanned the Twenty-first to Twenty-sixth Dynasties, and was marked by internal divisions within Egypt, as well as conquest and rule by foreigners.

Learning Objective

Describe the general landscape of the political chaos during Third Intermediate Period

Key Points

- The period of the Twenty-first Dynasty was characterized by the country’s fracturing kingship, as power became split more and more between the pharaoh and the High Priests of Amun at Thebes.

- Egypt was temporarily reunified during the Twenty-second Dynasty, and experienced a period of stability, but shattered into two states after the reign of Osorkon II.

- Civil war raged in Thebes and was eventually quelled by Osorkon B, who founded the Upper Egyptian Libyan Dynasty. This dynasty collapsed, however, with the rise of local city-states.

- The Twenty-fourth Dynasty saw the conquest of the Nubians over native Egyptian rulers, and the Nubians ruled through the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty, when they expanded Egyptian power to the extent of the New Kingdom and restored many temples. Due to lacking military power, however, the Egyptians were conquered by the Assyrians toward the end of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty.

- The end of the Third Intermediate Period and the Twenty-sixth Dynasty saw Assyrian rule over Egypt. Although some measure of independence was regained, Egypt faced pressure and eventual defeat at the hands of the Persians.

Key Terms

- Nubia

-

A region along the Nile river, located in northern Sudan and southern Egypt.

- Third Intermediate Period

-

Spanning the Twenty-first to Twenty-sixth Dynasties. A period of Egyptian decline and political instability.

- Assyrians

-

A major Mesopotamian East Semitic-speaking people.

- High Priests of Amun

-

The highest-ranking priest in the priesthood of the Ancient Egyptian god, Amun. Assumed significant power along with the pharaoh in the Twenty-First Dynasty.

The Third Intermediate Period of Ancient Egypt began with the death of the last pharaoh of the New Kingdom, Ramesses XI in 1070 BCE, and ended with the start of the Postdynastic Period. The Third Intermediate Period was one of decline and political instability. It was marked by a division of the state for much of the period, as well as conquest and rule by foreigners. However, many aspects of life for ordinary Egyptians changed relatively little.

The Twenty-First Dynasty (c. 1077-943 BCE)

The period of the Twenty-first Dynasty was characterized by the country’s fracturing kingship. Even in Ramesses XI’s day, the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt was losing its grip on power in the city of Thebes, where priests were becoming increasingly powerful. The Amun priests of Thebes owned 2/3 of all the temple lands in Egypt, 90% of ships, and many other resources. Consequently, the Amun priests were as powerful as the Pharaoh, if not more so. After the death of Ramesses XI, his successor, Smendes I, ruled from the city of Tanis, but was mainly active only in Lower Egypt. Meanwhile, the High Priests of Amun at Thebes effectively ruled Middle and Upper Egypt in all but name. During this time, however, this division was relatively insignificant, due to the fact that both priests and pharaohs came from the same family.

The Twenty-Second (c. 943-716 BCE) and Twenty-Third (c. 880-720 BCE) Dynasties

The country was firmly reunited by the Twenty-second Dynasty, founded by Shoshenq I in approximately 943 BCE. Shoshenq I descended from Meshwesh immigrants originally from Ancient Libya. This unification brought stability to the country for well over a century, but after the reign of Osorkon II, the country had shattered in two states. Shoshenq III of the Twenty-Second Dynasty controlled Lower Egypt by 818 BCE, while Takelot II and his son Osorkon (the future Osorkon III) ruled Middle and Upper Egypt. In Thebes, a civil war engulfed the city between the forces of Pedubast I, a self-proclaimed pharaoh. Eventually Osorkon B defeated his enemies, and proceeded to found the Upper Egyptian Libyan Dynasty of Osorkon III, Takelot III, and Rudamun. This kingdom quickly fragmented after Rudamun’s death with the rise of local city-states.

The Twenty-Fourth Dynasty (c. 732-720 BCE)

The Nubian kingdom to the south took full advantage of the division of the country. Nubia had already extended its influence into the Egyptian city of Thebes around 752 BCE, when the Nubian ruler Kashta coerced Shepenupet into adopting his own daughter Amenirdis as her successor. Twenty years later, around 732 BCE, these machinations bore fruit for Nubia when Kashta’s successor Piye marched north in his Year 20 campaign into Egypt, and defeated the combined might of the native Egyptian rulers.

The Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (c. 760-656 BCE)

Following his military conquests, Piye established the Twenty-fifth Dynasty and appointed the defeated rulers as his provincial governors. Rulers under this dynasty originated in the Nubian Kingdom of Kush. Their reunification of Lower Egypt, Upper Egypt, and Kish created the largest Egyptian empire since the New Kingdom. They assimilated into Egyptian culture but also brought some aspects of Kushite culture. During this dynasty, the first widespread building of pyramids since the Middle Kingdom resumed. The Nubians were driven out of Egypt in 670 BCE by the Assyrians, who installed an initial puppet dynasty loyal to the Assyrians.

Nubian Pharaohs

Statues of the Nubian Pharaohs of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty.

End of the Third Intermediate Period

Upper Egypt remained under the rule of Tantamani for a time, while Lower Egypt was ruled by the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, starting in 664 BCE. Although originally established as clients of the Assyrians, the Twenty-sixth Dynasty managed to take advantage of the time of troubles facing the Assyrian empire to successfully bring about Egypt’s political independence. In 656 BCE, Psamtik I (last of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty kings) occupied Thebes and became pharaoh, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt. He proceeded to reign over a united Egypt for 54 years from his capital at Sais. Four successive Saite kings continued guiding Egypt through a period of peace and prosperity from 610-525 BCE. Unfortunately for this dynasty, however, a new power was growing in the Near East: Persia. Pharaoh Psamtik III succeeded his father, Ahmose II, only six months before he had to face the Persian Empire at Pelusium. The new king was no match for the Persians, who had already taken Babylon. Psamtik III was defeated and briefly escaped to Memphis. He was ultimately imprisoned, and later executed at Susa, the capital of the Persian king Cambyses. With the Saite kings exterminated, Camybes assumed the formal title of Pharaoh.

4.4.4: The Decline of Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt went through a series of occupations and suffered a slow decline over a long period of time. First occupied by the Assyrians, then the Persians, and later the Macedonians and Romans, Egyptians would never again reach the glorious heights of self-rule they achieved during previous periods.

Learning Objective

Explain why Ancient Egypt declined as an economic and political force

Key Points

- After a renaissance in the 25th Dynasty, ancient Egypt was occupied by Assyrians, initiating the Late Period.

- In 525 BCE, Egypt was conquered by Persia, and incorporated into the Achaemenid Persian Empire.

- In 332 BCE, Egypt was given to Macedonia and Alexander the Great. During this period, the new capital of Alexandria flourished.

- Egypt became a Roman province after the defeat of Marc Antony and Queen Cleopatra VII in 30 BCE. During this period, religious and other traditions slowly declined.

Key Terms

- Hellenistic

-

Relating to Greek history, language, and culture, during the time between the death of Alexander the Great and the defeat of Mark Antony and Cleopatra in 31 BCE.

- hieroglyphics

-

A formal writing system used by ancient Egyptians, consisting of pictograms.

- pagan

-

A person holding religious beliefs other than those of the main world religions, Christianity, Judaism, and Islam.

Ancient Egypt went through a series of occupations and suffered a slow decline over a long period of time. First occupied by the Assyrians, then the Persians, and later the Macedonians and Romans, Egyptians would never again reach the glorious heights of self-rule they achieved during previous periods.

Third Intermediate Period (1069-653 BCE)

After a renaissance in the Twenty-fifth dynasty, when religion, arts, and architecture (including pyramids) were restored, struggles against the Assyrians led to eventual conquest of Egypt by Esarhaddon in 671 BCE. Native Egyptian rulers were installed but could not retain control of the area, and former Pharaoh Taharqa seized control of southern Egypt for a time, until he was defeated again by the Assyrians. Taharqa’s successor, Tanutamun, also made a failed attempt to regain Egypt, but was defeated.

Late Period (672-332 BCE)

Having been victorious in Egypt, the Assyrians installed a series of vassals known as the Saite kings of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty. In 653 BCE, one of these kings, Psamtik I, was able to achieve a peaceful separation from the Assyrians with the help of Lydian and Greek mercenaries. In 609 BCE, the Egyptians attempted to save the Assyrians, who were losing their war with the Babylonians, Chaldeans, Medians, and Scythians. However, they were unsuccessful.

In 525 BCE, the Persians, led by Cambyses II, invaded Egypt, capturing the Pharaoh Psamtik III. Egypt was joined with Cyprus and Phoenicia in the sixth satrapy of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, also called the Twenty-seventh Dynasty. This ended in 402 BCE, and the last native royal house of dynastic Egypt, known as the Thirtieth Dynasty, was ruled by Nectanebo II. Persian rule was restored briefly in 343 BCE, known as the Thirty-first Dynasty, but in 332 BCE, Egypt was handed over peacefully to the Macedonian ruler, Alexander the Great.

Macedonian and Ptolemaic Period (332-30 BCE)

Alexander the Great was welcomed into Egypt as a deliverer, and the new capital city of Alexandria was a showcase of Hellenistic rule, capped by the famous Library of Alexandria. Native Egyptian traditions were honored, but eventually local revolts, plus interest in Egyptian goods by the Romans, caused the Romans to wrest Egypt from the Macedonians.

Roman Period (30 BCE-641CE)

Egypt became a Roman province after the defeat of Marc Antony and Queen Cleopatra VII in 30 BCE. Some Egyptian traditions, including mummification and worship of local gods, continued, but local administration was handled exclusively by Romans. The spread of Christianity proved to be too powerful, and pagan rites were banned and temples closed. Egyptians continued to speak their language, but the ability to read hieroglyphics disappeared as temple priests diminished.

4.5: Ancient Egyptian Society

4.5.1: Ancient Egyptian Religion

Ancient Egyptian religion lasted for more than 3,000 years, and consisted of a complex polytheism. The pharaoh’s role was to sustain the gods in order to maintain order in the universe.

Learning Objective

Describe the religious beliefs and practices of Ancient Egypt

Key Points

- The religion of Ancient Egypt lasted for more than 3,000 years, and was polytheistic, meaning there were a multitude of deities, who were believed to reside within and control the forces of nature.

- Formal religious practice centered on the pharaoh, or ruler, of Egypt, who was believed to be divine, and acted as intermediary between the people and the gods. His role was to sustain the gods so that they could maintain order in the universe.

- The Egyptian universe centered on Ma’at, which has several meanings in English, including truth, justice and order. It was fixed and eternal; without it the world would fall apart.

- The most important myth was of Osiris and Isis. The divine ruler Osiris was murdered by Set (god of chaos), then resurrected by his sister and wife Isis to conceive an heir, Horus. Osiris then became the ruler of the dead, while Horus eventually avenged his father and became king.

- Egyptians were very concerned about the fate of their souls after death. They believed ka (life-force) left the body upon death and needed to be fed. Ba, or personal spirituality, remained in the body. The goal was to unite ka and ba to create akh.

- Artistic depictions of gods were not literal representations, as their true nature was considered mysterious. However, symbolic imagery was used to indicate this nature.

- Temples were the state’s method of sustaining the gods, since their physical images were housed and cared for; temples were not a place for the average person to worship.

- Certain animals were worshipped and mummified as representatives of gods.

- Oracles were used by all classes.

Key Terms

- Ma’at,

-

The Egyptian universe.

- heka

-

The ability to use natural forces to create “magic.”

- pantheon

-

The core actors of a religion.

- polytheistic

-

A religion with more than one worshipped god.

- ka

-

The spiritual part of an individual human being or god that survived after death.

- Duat

-

The realm of the dead; residence of Osiris.

- ba

-

The spiritual characteristics of an individual person that remained in the body after death. Ba could unite with the ka.

- akh

-

The combination of the ka and ba living in the afterlife.

The religion of Ancient Egypt lasted for more than 3,000 years, and was polytheistic, meaning there were a multitude of deities, who were believed to reside within and control the forces of nature. Religious practices were deeply embedded in the lives of Egyptians, as they attempted to provide for their gods and win their favor. The complexity of the religion was evident as some deities existed in different manifestations and had multiple mythological roles. The pantheon included gods with major roles in the universe, minor deities (or “demons”), foreign gods, and sometimes humans, including deceased Pharaohs.

Formal religious practice centered on the pharaoh, or ruler, of Egypt, who was believed to be divine, and acted as intermediary between the people and the gods. His role was to sustain the gods so that they could maintain order in the universe, and the state spent its resources generously to build temples and provide for rituals. The pharaoh was associated with Horus (and later Amun) and seen as the son of Ra. Upon death, the pharaoh was fully deified, directly identified with Ra and associated with Osiris, the god of death and rebirth. However, individuals could appeal directly to the gods for personal purposes through prayer or requests for magic; as the pharaoh’s power declined, this personal form of practice became stronger. Popular religious practice also involved ceremonies around birth and naming. The people also invoked “magic” (called heka) to make things happen using natural forces.

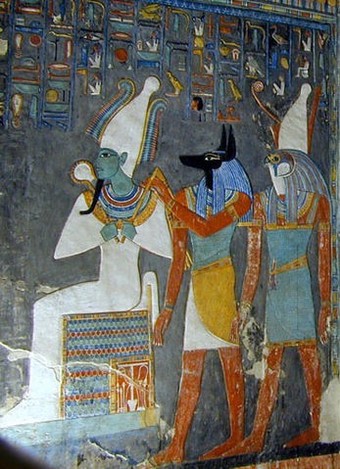

Gods of the Pantheon

This wall painting shows, from left to right, the gods Osiris, Anubis and Horus.

Cosmology

The Egyptian universe centered on Ma’at, which has several meanings in English, including truth, justice and order. It was fixed and eternal (without it the world would fall apart), and there were constant threats of disorder requiring society to work to maintain it. Inhabitants of the cosmos included the gods, the spirits of deceased humans, and living humans, the most important of which was the pharaoh. Humans should cooperate to achieve this, and gods should function in balance. Ma’at was renewed by periodic events, such as the annual Nile flood, which echoed the original creation. Most important of these was the daily journey of the sun god Ra.

Egyptians saw the earth as flat land (the god Geb), over which arched the sky (goddess Nut); they were separated by Shu, the god of air. Underneath the earth was a parallel underworld and undersky, and beyond the skies lay Nu, the chaos before creation. Duat was a mysterious area associated with death and rebirth, and each day Ra passed through Duat after traveling over the earth during the day.

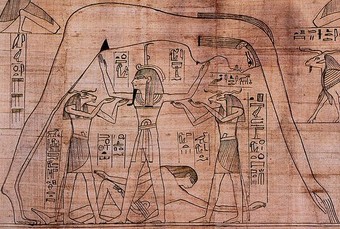

Egyptian Cosmology

In this artwork, the air god Shu is assisted by other gods in holding up Nut, the sky, as Geb, the earth, lies beneath.

Myths

Egyptian myths are mainly known from hymns, ritual and magical texts, funerary texts, and the writings of Greeks and Romans. The creation myth saw the world as emerging as a dry space in the primordial ocean of chaos, marked by the first rising of Ra. Other forms of the myth saw the primordial god Atum transforming into the elements of the world, and the creative speech of the intellectual god Ptah.

The most important myth was of Osiris and Isis. The divine ruler Osiris was murdered by Set (god of chaos), then resurrected by his sister and wife Isis to conceive an heir, Horus. Osiris then became the ruler of the dead, while Horus eventually avenged his father and became king. This myth set the Pharaohs, and their succession, as orderliness against chaos.

The Afterlife

Egyptians were very concerned about the fate of their souls after death, and built tombs, created grave goods and gave offerings to preserve the bodies and spirits of the dead. They believed humans possessed ka, or life-force, which left the body at death. To endure after death, the ka must continue to receive offerings of food; it could consume the spiritual essence of it. Humans also possessed a ba, a set of spiritual characteristics unique to each person, which remained in the body after death. Funeral rites were meant to release the ba so it could move, rejoin with the ka, and live on as an akh. However, the ba returned to the body at night, so the body must be preserved.

Mummification involved elaborate embalming practices, and wrapping in cloth, along with various rites, including the Opening of the Mouth ceremony. Tombs were originally mastabas (rectangular brick structures), and then pyramids.

However, this originally did not apply to the common person: they passed into a dark, bleak realm that was the opposite of life. Nobles did receive tombs and grave gifts from the pharaoh. Eventually, by about 2181 BCE, Egyptians began to believe every person had a ba and could access the afterlife. By the New Kingdom, the soul had to face dangers in the Duat before having a final judgment, called the Weighing of the Heart, where the gods compared the actions of the deceased while alive to Ma’at, to see if they were worthy. If so, the ka and ba were united into an akh, which then either traveled to the lush underworld, or traveled with Ra on his daily journey, or even returned to the world of the living to carry out magic.

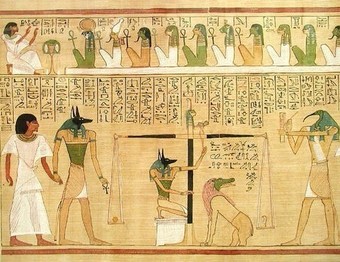

Funerary Text

In this section from the Book of the Dead for the scribe Hunefer, the Weighing of the Heart is shown.

Rise and Fall of Gods

Certain gods gained a primary status over time, and then fell as other gods overtook them. These included the sun god Ra, the creator god Amun, and the mother goddess Isis. There was even a period of time where Egypt was monotheistic, under Pharaoh Akhenaten, and his patron god Aten.

The Relationships of Deities

Just as the forces of nature had complex interrelationships, so did Egyptian deities. Minor deities might be linked, or deities might come together based on the meaning of numbers in Egyptian mythology (i.e., pairs represented duality). Deities might also be linked through syncretism, creating a composite deity.

Artistic Depictions of Gods

Artistic depictions of gods were not literal representations, since their true nature was considered mysterious. However, symbolic imagery was used to indicate this nature. An example was Anubis, a funerary god, who was shown as a jackal to counter its traditional meaning as a scavenger, and create protection for the mummy.

Temples

Temples were the state’s method of sustaining the gods, as their physical images were housed and cared for; they were not a place for the average person to worship. They were both mortuary temples to serve deceased pharaohs and temples for patron gods. Starting as simple structures, they grew more elaborate, and were increasingly built from stone, with a common plan. Ritual duties were normally carried out by priests, or government officials serving in the role. In the New Kingdom, professional priesthood became common, and their wealth rivaled that of the pharaoh.

Rituals and Festivals

Aside from numerous temple rituals, including the morning offering ceremony and re-enactments of myths, there were coronation ceremonies and the sed festival, a renewal of the pharaoh’s strength during his reign. The Opet Festival at Karnak involved a procession carrying the god’s image to visit other significant sites.

Animal Worship

At many sites, Egyptians worshipped specific animals that they believed to be manifestations of deities. Examples include the Apis bull (of the god Ptah), and mummified cats and other animals.

Use of Oracles

Commoners and pharaohs asked questions of oracles, and answers could even be used during the New Kingdom to settle legal disputes. This might involve asking a question while a divine image was being carried, and interpreting movement, or drawing lots.

4.5.2: Ancient Egyptian Art

Ancient Egyptian art included painting, sculpture, pottery, glass work, and architecture. Many surviving art is related to tombs and monuments. Aside from the brief Amarna period, Egyptian art remained relatively unchanged for thousands of years.

Learning Objective

Examine the development of Egyptian Art under the Old Kingdom

Key Points

- Ancient Egyptian art includes painting, sculpture, architecture, and other forms of art, such as drawings on papyrus, created between 3000 BCE and 100 CE.

- Most of this art was highly stylized and symbolic. Much of the surviving forms come from tombs and monuments, and thus have a focus on life after death and preservation of knowledge.

- Symbolism meant order, shown through the pharaoh’s regalia, or through the use of certain colors.

- In Egyptian art, the size of a figure indicates its relative importance.

- Paintings were often done on stone, and portrayed pleasant scenes of the afterlife in tombs.

- Ancient Egyptians created both monumental and smaller sculptures, using the technique of sunk relief.

- Ka statues, which were meant to provide a resting place for the ka part of the soul, were often made of wood and placed in tombs.

- Faience was sintered-quartz ceramic with surface vitrification, used to create relatively cheap small objects in many colors. Glass was originally a luxury item but became more common, and was used to make small jars, for perfume and other liquids, to be placed in tombs. Carvings of vases, amulets, and images of deities and animals were made of steatite. Pottery was sometimes covered with enamel, particularly in the color blue.

- Papyrus was used for writing and painting, and and was used to record every aspect of Egyptian life.

- Architects carefully planned buildings, aligning them with astronomically significant events, such as solstices and equinoxes. They used mainly sun-baked mud brick, limestone, sandstone, and granite.

- The Amarna period (1353-1336 BCE) represents an interruption in ancient Egyptian art style, subjects were represented more realistically, and scenes included portrayals of affection among the royal family.

Key Terms

- scarabs

-

Ancient Egyptian gem cut in the form of a scarab beetle.

- Faience

-

Glazed ceramic ware.

- ushabti

-

Ancient Egyptian funerary figure.

- Ka

-

The supposed spiritual part of an individual human being or god that survived after death, and could reside in a statue of the person.

- sunk relief

-

Sculptural technique in which the outlines of modeled forms are incised in a plane surface beyond which the forms do not project.

- regalia

-

The emblems or insignia of royalty.

- papyrus

-

A material prepared in ancient Egypt from the stem of a water plant, used in sheets for writing or painting on.

Ancient Egyptian art includes painting, sculpture, architecture, and other forms of art, such as drawings on papyrus, created between 3000 BCE and 100 AD. Most of this art was highly stylized and symbolic. Many of the surviving forms come from tombs and monuments, and thus have a focus on life after death and preservation of knowledge.

Symbolism

Symbolism in ancient Egyptian art conveyed a sense of order and the influence of natural elements. The regalia of the pharaoh symbolized his or her power to rule and maintain the order of the universe. Blue and gold indicated divinity because they were rare and were associated with precious materials, while black expressed the fertility of the Nile River.

Hierarchical Scale

In Egyptian art, the size of a figure indicates its relative importance. This meant gods or the pharaoh were usually bigger than other figures, followed by figures of high officials or the tomb owner; the smallest figures were servants, entertainers, animals, trees and architectural details.

Painting

Before painting a stone surface, it was whitewashed and sometimes covered with mud plaster. Pigments were made of mineral and able to stand up to strong sunlight with minimal fade. The binding medium is unknown; the paint was applied to dried plaster in the “fresco a secco” style. A varnish or resin was then applied as a protective coating, which, along with the dry climate of Egypt, protected the painting very well. The purpose of tomb paintings was to create a pleasant afterlife for the dead person, with themes such as journeying through the afterworld, or deities providing protection. The side view of the person or animal was generally shown, and paintings were often done in red, blue, green, gold, black and yellow.

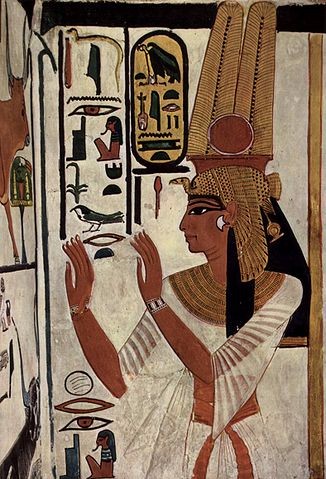

Wall Painting of Nefertari

In this wall painting of Nefertari, the side view is apparent.

Sculpture

Ancient Egyptians created both monumental and smaller sculptures, using the technique of sunk relief. In this technique, the image is made by cutting the relief sculpture into a flat surface, set within a sunken area shaped around the image. In strong sunlight, this technique is very visible, emphasizing the outlines and forms by shadow. Figures are shown with the torso facing front, the head in side view, and the legs parted, with males sometimes darker than females. Large statues of deities (other than the pharaoh) were not common, although deities were often shown in paintings and reliefs.

Colossal sculpture on the scale of the Great Sphinx of Giza was not repeated, but smaller sphinxes and animals were found in temple complexes. The most sacred cult image of a temple’s god was supposedly held in the naos in small boats, carved out of precious metal, but none have survived.

Ka statues, which were meant to provide a resting place for the ka part of the soul, were present in tombs as of Dynasty IV (2680-2565 BCE). These were often made of wood, and were called reserve heads, which were plain, hairless and naturalistic. Early tombs had small models of slaves, animals, buildings, and objects to provide life for the deceased in the afterworld. Later, ushabti figures were present as funerary figures to act as servants for the deceased, should he or she be called upon to do manual labor in the afterlife.

Ka Statue

The ka statue was placed in the tomb to provide a physical place for the ka to manifest. This statue is found at the Egyptian Museum of Cairo.

Many small carved objects have been discovered, from toys to utensils, and alabaster was used for the more expensive objects. In creating any statuary, strict conventions, accompanied by a rating system, were followed. This resulted in a rather timeless quality, as few changes were instituted over thousands of years.

Faience, Pottery, and Glass

Faience was sintered-quartz ceramic with surface vitrification used to create relatively cheap, small objects in many colors, but most commonly blue-green. It was often used for jewelry, scarabs, and figurines. Glass was originally a luxury item, but became more common, and was to used to make small jars, of perfume and other liquids, to be placed in tombs. Carvings of vases, amulets, and images of deities and animals were made of steatite. Pottery was sometimes covered with enamel, particularly in the color blue. In tombs, pottery was used to represent organs of the body removed during embalming, or to create cones, about ten inches tall, engraved with legends of the deceased.

Papyrus

Papyrus is very delicate and was used for writing and painting; it has only survived for long periods when buried in tombs. Every aspect of Egyptian life is found recorded on papyrus, from literary to administrative documents.

Architecture

Architects carefully planned buildings, aligning them with astronomically significant events, such as solstices and equinoxes, and used mainly sun-baked mud brick, limestone, sandstone, and granite. Stone was reserved for tombs and temples, while other buildings, such as palaces and fortresses, were made of bricks. Houses were made of mud from the Nile River that hardened in the sun. Many of these houses were destroyed in flooding or dismantled; examples of preserved structures include the village Deir al-Madinah and the fortress at Buhen.

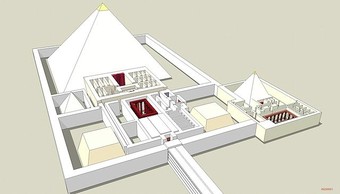

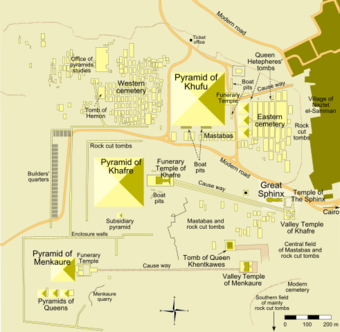

The Giza Necropolis, built in the Fourth Dynasty, includes the Pyramid of Khufu (also known as the Great Pyramid or the Pyramid of Cheops), the Pyramid of Khafre, and the Pyramid of Menkaure, along with smaller “queen” pyramids and the Great Sphinx.

The Pyramids of Giza

The Pyramid of Khufu (Great Pyramid) is the largest of the pyramids pictured here.

The Temple of Karnak was first built in the 16th century BCE. About 30 pharaohs contributed to the buildings, creating an extremely large and diverse complex. It includes the Precincts of Amon-Re, Montu and Mut, and the Temple of Amehotep IV (dismantled).

The Temple of Karnak

Shown here is the hypostyle hall of the Temple of Karnak.

The Luxor Temple was constructed in the 14th century BCE by Amenhotep III in the ancient city of Thebes, now Luxor, with a major expansion by Ramesses II in the 13th century BCE. It includes the 79-foot high First Pylon, friezes, statues, and columns.

The Amarna Period (1353-1336 BCE)

During this period, which represents an interruption in ancient Egyptian art style, subjects were represented more realistically, and scenes included portrayals of affection among the royal family. There was a sense of movement in the images, with overlapping figures and large crowds. The style reflects Akhenaten’s move to monotheism, but it disappeared after his death.

4.5.3: Ancient Egyptian Monuments

Ancient Egyptian monuments included pyramids, sphinxes, and temples. These buildings and statues required careful planning and resources, and showed the influence Egyptian religion had on the state and its people.

Learning Objective

Describe the impressive attributes of the monuments erected by Egyptians in the Old Kingdom

Key Points