38.1: Europe in the 21st Century

38.1.1: Move to the Euro

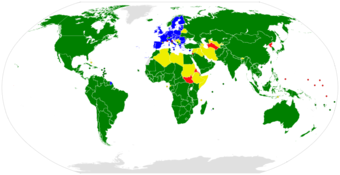

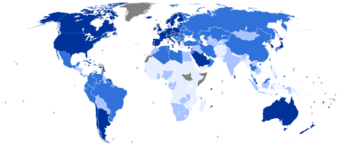

The eurozone is a monetary union of 19 of the 28 European Union member states that have adopted the euro as their common currency and sole legal tender to coordinate their economic policies and cooperation.

Learning Objective

Explain why the euro was established and which countries currently use it

Key Points

-

A first attempt to create

an economic and monetary union between the members of the European Economic

Community (EEC) goes back to the 1960s, when the need for “greater co-ordination of economic

policies and monetary cooperation” was defined. However, following the Bretton Woods system collapse, the aspirations for

European monetary union were set back. Then in 1979, the European Monetary System (EMS)

was created, fixing exchange rates onto the European Currency Unit (ECU), an

accounting currency introduced to stabilize exchange rates and counter

inflation. - In 1989, European leaders reached agreement on a currency union with

the 1992 Maastricht Treaty. The treaty included the goal of creating a single

currency by 1999, although without the participation of the United Kingdom.

In 1995, the name euro was

adopted for the new currency and it was agreed that it would be launched on

January 1, 1999. In 1998, 11 initial countries were selected to participate in the launch. To adopt the new currency, member states had

to meet strict criteria. -

Greece

failed to meet the criteria and was excluded from joining the monetary union in

1999. The UK and Denmark received the opt-outs while Sweden joined the EU in

1995 after the Maastricht Treaty, which was too late to join the initial group

of member-states. In 1998, the European Central Bank succeeded the European

Monetary Institute. The conversion rates between the 11 participating national

currencies and the euro were then established. -

The currency was

introduced in non-physical form on January 1, 1999. The notes and coins for

the old currencies continued to be used as legal tender until new notes and

coins were introduced on January 1, 2002.

The

enlargement of the eurozone is an ongoing process. All

member states, except Denmark and the United Kingdom, are obliged to adopt the euro. Currently 19 states are members of the eurozone and seven additional states are on the enlargement agenda. Several non-EU European states and some overseas territories also use the euro, but each case is regulated differently. -

Following the U.S.

financial crisis in 2008, fears of a sovereign debt crisis developed in 2009

among fiscally conservative investors. Several

eurozone member states (Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Cyprus) were

unable to repay or refinance their government debt or bail out over-indebted

banks under their national supervision without the assistance of third parties

like other eurozone countries, the European Central Bank (ECB), or the

International Monetary Fund (IMF). -

The

detailed causes of the debt crisis varied. In several countries, private debts

arising from a property bubble were transferred to sovereign debt as a result

of banking system bailouts and government responses to slowing economies

post-bubble. The structure of the eurozone as a currency union (i.e., one

currency) without fiscal union (e.g., different tax and public pension rules)

contributed to the crisis and limited the ability of European leaders to

respond. As concerns intensified, leading European

nations implemented a series of financial support measures, but the crisis had far-reaching effects across the EU.

Key Terms

- European Economic Community

-

A regional organization that aimed to bring about economic integration among its member states. It was created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957. Upon the formation of the European Union (EU) in 1993, it was incorporated and renamed as the European Community (EC). In 2009, the EC’s institutions were absorbed into the EU’s wider framework and the community ceased to exist.

- European Council

-

The institution of the European Union (EU) that comprises the heads of state or government of the member states, along with the President of the European Council and the President of the European Commission,

charged with defining the EU’s overall political direction and priorities. - Maastricht Treaty

-

A treaty undertaken to integrate Europe and signed in 1992 by the members of the European Community. Upon its entry into force in 1993, it created the European Union and led to the creation of the single European currency, the euro. The treaty has been amended by the treaties of Amsterdam, Nice, and Lisbon.

- European Central Bank

-

The central bank for the euro that administers monetary policy of the eurozone. Consisting of 19 EU member states, it is one of the largest currency areas in the world, one of the world’s most important central banks, and one of the seven institutions of the European Union (EU) listed in the Treaty on European Union (TEU). The capital stock of the bank is owned by the central banks of all 28 EU member states.

- Bretton Woods system

-

A monetary management system that established the rules for commercial and financial relations among the United States, Canada, Western Europe, Australia, and Japan in the mid-20th century. It was the first example of a fully negotiated monetary order intended to govern monetary relations among independent nation-states. Its chief features were an obligation for each country to adopt a monetary policy that maintained the exchange rate (± 1 percent) by tying its currency to gold and the ability of the IMF to bridge temporary payment imbalances.

- European Commission

-

An institution of the European Union responsible for proposing legislation, implementing decisions, upholding the EU treaties, and managing the day-to-day business of the EU. Commissioners swear an oath at the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg, pledging to respect the treaties and be completely independent in carrying out their duties during their mandate.

Origin of Common Currency in Europe

A first attempt to create an economic and monetary union between the members of the European Economic Community (EEC) goes back to an initiative by the European Commission in 1969. The initiative proclaimed the need for “greater coordination of economic policies and monetary cooperation” and was introduced at a meeting of the European Council. The European Council tasked Pierre Werner, Prime Minister of Luxembourg, with finding a way to reduce currency exchange rate volatility. His report was published in 1970 and recommended centralization of the national macroeconomic policies, but he did not propose a single currency or central bank.

In 1971, U.S. President Richard Nixon removed the gold backing from the U.S. dollar, causing a collapse in the Bretton Woods system that affected all the world’s major currencies. The widespread currency floats and devaluations set back aspirations for European monetary union. However, in 1979, the European Monetary System (EMS) was created, fixing exchange rates onto the European Currency Unit (ECU), an accounting currency introduced to stabilize exchange rates and counter inflation. In 1989, European leaders reached agreement on a currency union with the 1992 Maastricht Treaty. The treaty included the goal of creating a single currency by 1999, although without the participation of the United Kingdom. However, gaining approval for the treaty was a challenge. Germany was cautious about giving up its stable currency, France approved the treaty by a narrow margin, and Denmark refused to ratify until they got an opt-out from the planned monetary union (similar to that of the United Kingdom’s).

In 1994, the European Monetary Institute, the forerunner to the European Central Bank, was created. After much disagreement, in 1995 the name euro was adopted for the new currency (replacing the name ecu used for the previous accounting currency) and it was agreed that it would be launched on January 1, 1999. In 1998, 11 initial countries were selected to participate in the initial launch. To adopt the new currency, member states had to meet strict criteria, including a budget deficit of less than 3% of their GDP, a debt ratio of less than 60% of GDP, low inflation, and interest rates close to the EU average. Greece failed to meet the criteria and was excluded from joining the monetary union in 1999. The UK and Denmark received the opt-outs while

Sweden joined the EU in 1995 after the Maastricht Treaty, which was too late to join the initial group of member-states. In 1998, the European Central Bank succeeded the European Monetary Institute. The conversion rates between the 11 participating national currencies and the euro were then established.

Launch of Eurozone

The currency was introduced in non-physical form (traveler’s checks, electronic transfers, banking, etc.) at midnight on January 1, 1999, when the national currencies of participating countries (the eurozone) ceased to exist independently in that their exchange rates were locked at fixed rates against each other, effectively making them mere non-decimal subdivisions of the euro. The notes and coins for the old currencies continued to be used as legal tender until new notes and coins were introduced on January 1, 2002. Beginning January 1, 1999, all bonds and other forms of government debt by eurozone states were denominated in euros.

Euro coins and banknotes

The designs for the new coins and notes were announced between 1996 and 1998 and production began at the various mints and printers in 1998. The task was large: 7.4 billion notes and 38.2 billion coins would be available for issuance to consumers and businesses in 2002. Despite the fears of chaos,

the eventual switch to the euro was smooth, with very few problems.

In 2000, Denmark held a referendum on whether to abandon their opt-out from the euro. The referendum resulted in a decision to retain the Danish krone and also set back plans for a referendum in the UK as a result.

Greece joined the eurozone on January 1, 2001, one year before the physical euro coins and notes replaced the old national currencies in the eurozone.

Eurozone Today

The enlargement of the eurozone is an ongoing process within the EU. All member states, except Denmark and the United Kingdom which negotiated opt-outs from the provisions, are obliged to adopt the euro as their sole currency once they meet the criteria. Following the EU enlargement by 10 new members in 2004, seven countries joined the eurozone: Slovenia (2007), Cyprus (2008), Malta (2008), Slovakia (2009), Estonia (2011), Latvia (2014), and Lithuania (2015). Seven remaining states, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden, are on the enlargement agenda.

Sweden, which joined the EU in 1995, turned down euro adoption in a 2003 referendum. Since then, the country has intentionally avoided fulfilling the adoption requirements.

Several European microstates outside the EU have adopted the euro as their currency. For the EU to sanction this adoption, a monetary agreement must be concluded. Prior to the launch of the euro, agreements were reached with Monaco, San Marino, and Vatican City by EU member states (Italy in the case of San Marino and Vatican City and France in the case of Monaco) allowing them to use the euro and mint a limited amount of euro coins (but not banknotes). All these states previously had monetary agreements to use yielded eurozone currencies. A similar agreement was negotiated with Andorra and came into force in 2012. Outside the EU, there are currently three French territories and a British territory that have agreements to use the euro as their currency. All other dependent territories of eurozone member states that have opted not to be a part of EU, usually with Overseas Country and Territory (OCT) status, use local currencies, often pegged to the euro or U.S. dollar.

Montenegro and Kosovo (non-EU members) have also used the euro since its launch, as they previously used the German mark rather than the Yugoslav dinar. Unlike the states above, however, they do not have a formal agreement with the EU to use the euro as their currency (unilateral use) and have never minted marks or euros. Instead, they depend on bills and coins already in circulation.

Euro Banknotes

The euro banknotes have common designs on both sides created by the Austrian designer Robert Kalina. Each banknote has its own color and is dedicated to an artistic period of European architecture. The front of the note features windows or gateways while the back has bridges, symbolizing links between countries and with the future.

Eurozone Crisis

Following the U.S. financial crisis in 2008, fears of a sovereign debt crisis developed in 2009 among fiscally conservative investors concerning some European states. Several eurozone member states (Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Cyprus) were unable to repay or refinance their government debt or bail out over-indebted banks under their national supervision without the assistance of third parties like other eurozone countries, the European Central Bank (ECB), or the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The detailed causes of the debt crisis varied. In several countries, private debts arising from a property bubble were transferred to sovereign debt as a result of banking system bailouts and government responses to slowing economies post-bubble. The structure of the eurozone as a currency union (i.e., one currency) without fiscal union (e.g., different tax and public pension rules) contributed to the crisis and limited the ability of European leaders to respond. As concerns intensified in 2010 and thereafter, leading European nations implemented a series of financial support measures such as the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and European Stability Mechanism (ESM). The ECB also contributed to solve the crisis by lowering interest rates and providing cheap loans of more than one trillion euro to maintain money flow between European banks. In 2012, the ECB calmed financial markets by announcing free unlimited support for all eurozone countries involved in a sovereign state bailout/precautionary program from EFSF/ESM through yield-lowering Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT).

Return to economic growth and improved structural deficits enabled Ireland and Portugal to exit their bailout programs in 2014. Greece and Cyprus both managed to partly regain market access in 2014. Spain never officially received a bailout program. Nonetheless, the crisis had significant adverse economic effects, with unemployment rates in Greece and Spain reaching 27%. It was also blamed for subdued economic growth, not only for the entire eurozone, but for the entire European Union. As such, it is thought to have had a major political impact on the ruling governments in 10 out of 19 eurozone countries, contributing to power shifts in Greece, Ireland, France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Slovenia, Slovakia, Belgium, and the Netherlands, as well as outside of the eurozone in the United Kingdom.

38.1.2: Russian Aggression in Georgia and Ukraine

The 2008 Russo-Georgian War and the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea, which violated the territorial integrity of Georgia and Ukraine respectively, demonstrated Russia’s

willingness to wage a full-scale military campaign to attain its political objectives and revealed the weaknesses of the Western defense system.

Learning Objective

Describe the events surrounding Russia’s actions against Georgia and Ukraine

Key Points

-

The tensions between

Georgia and Russia heightened during the secessionist conflicts in South Ossetia and

Abkhazia, which led to the

1991-92 South Ossetia War and the 1992-1993 War

in Abkhazia.

The

strategic importance of the Transcaucasia region has made it a security concern for Russia. Support for the

Abkhaz from various groups within Russia including regular military units, and support for

South Ossetia by their ethnic brethren who lived in Russia’s federal subject of

North Ossetia, proved critical in the de

facto secession

of Abkhazia and South Ossetia from Georgia. -

The

conflict between Russia and Georgia began to escalate in 2000, when Russia imposed visa regime on Georgia. In 2001, Eduard Kokoity,

endorsed by Russia, became de

facto president

of South Ossetia. The Russian government also began

massive distribution of Russian passports to the residents of Abkhazia and

South Ossetia in 2002. After Georgia deported four suspected Russian spies in 2006, Russia

began a full-scale diplomatic and economic war against Georgia. In 2008, Abkhazia and

South Ossetia submitted formal requests for their recognition to Russia’s

parliament. -

By August 1, 2008,

Ossetian separatists began shelling Georgian villages. To put an end to these attacks, the Georgian Army was sent to the South Ossetian conflict zone.

Russian and Ossetian forces battled Georgian

forces in and around South Ossetia and Russian and Abkhaz forces opened a second front.

On August 17, Russian

President Dmitry Medvedev announced

that Russian forces would begin to pull out of Georgia the following day but several days later he recognized Abkhazia and South

Ossetia as independent states. In accordance with the Georgian stand, many international actors recognize Abkhazia and South Ossetia as occupied Georgian

territories. -

The 2008 war was the first

time since the fall of the Soviet Union that the Russian military was used

against an independent state, demonstrating Russia’s willingness to wage a full-scale

military campaign to attain its political objectives. The failure of the

Western security system to respond swiftly to Russia’s attempt to forcibly

revise the existing borders revealed its weaknesses. Shortly after the war,

Russian president Medvedev unveiled a five-point Russian foreign policy, which implied that the presence of Russian citizens in

foreign countries would form a doctrinal foundation for invasion if needed. -

Despite being an

independent country since 1991, Russia has perceived Ukraine as part of its

sphere of interests. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, both states

retained close ties, but political, military, and economic tensions began almost immediately. Ukraine’s democratization in the aftermath of the 2004 Orange Revolution and increasingly close ties with NATO and the EU halted with the election of pro-Russian Yanukovich in 2010. When Yanukovich refused to sign an agreement with the EU, protests known as the Euromaidan movement broke out, eventually overthrowing Yanukovich’s government. - In the aftermath of the events, the Ukrainian territory of Crimea was annexed by Russia in March 2014. Since then, the peninsula has been administered as two de facto Russian federal subjects—the Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol. The annexation was preceded by a military intervention by Russia in Crimea and followed by the War in Donbass. Many members of the international community condemned the annexation, with some imposing sanctions on Russia.

Key Terms

- Russo-Georgian War

-

A war between Georgia, Russia and the Russian-backed self-proclaimed republics of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. The war took place in August 2008 following a period of worsening relations between Russia and Georgia, both formerly constituent republics of the Soviet Union. The fighting took place in the strategically important Transcaucasia region, which borders the Middle East. It was regarded as the first European war of the 21st century.

- War in Donbass

-

An armed conflict in the Donbass region of Ukraine. In March 2014, protests by pro-Russian and anti-government groups began in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Ukraine, together commonly called the Donbass, in the aftermath of the 2014 Ukrainian revolution and the Euromaidan movement. These demonstrations escalated into an armed conflict between the separatist forces of the self-declared Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics and the Ukrainian government.

- Orange Revolution

-

A series of protests and political events that took place in Ukraine from late November 2004 to January 2005, in the immediate aftermath of the run-off vote of the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election, which was claimed to be marred by massive corruption, voter intimidation, and direct electoral fraud. Kiev, the Ukrainian capital, was the focal point of the movement’s campaign of civil resistance, with thousands of protesters demonstrating daily. Nationwide, the democratic revolution was highlighted by a series of acts of civil disobedience, sit-ins, and general strikes organized by the opposition movement.

- 1991–92 South Ossetia War

-

A war fought as part of the Georgian-Ossetian conflict between Georgian government forces and ethnic Georgian militia on one side and the forces of South Ossetia and ethnic Ossetian militia who wanted South Ossetia to secede from Georgia on the other. The war ended with a Russian-brokered ceasefire, which established a joint peacekeeping force and left South Ossetia divided between the rival authorities.

- Commonwealth of Independent States

-

A regional organization formed during the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Nine out of the 15 former Soviet Republics are member states and two are associate members (Ukraine and Turkmenistan). Georgia withdrew its membership in 2008, while the Baltic states (Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia) chose not to participate. The organization has few supranational powers but aims to be more than a purely symbolic organization, nominally possessing coordinating powers in the realms of trade, finance, lawmaking, and security.

- 1992-1993 War in Abkhazia

-

A war fought between Georgian government forces and Abkhaz separatist forces, Russian armed forces, and North Caucasian militants. Ethnic Georgians who lived in Abkhazia fought largely on the side of Georgian government forces. The separatists fighting for the autonomy of Abkhasia received support from thousands of North Caucasus and Cossack militants and from the Russian Federation forces stationed in and near Abkhazia.

- Euromaidan

-

A wave of demonstrations and civil unrest in Ukraine that began on the night of November 21, 2013, with public protests in Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) in Kiev, demanding closer European integration. The scope of the protests expanded, with many calls for the resignation of President Viktor Yanukovich and his government. The protests led to the overthrow of Yanukovich’s government.

Background of Russo-Georgian Conflict

The tensions between Georgia and Russia, heightened even before the collapse of the Soviet Union, climaxed during the secessionist conflicts in South Ossetia and Abkhazia.

From 1922 to 1990, the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast was an autonomous oblast

(administrative unit)

of the Soviet Union created within the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic. Its autonomy, however, was revoked in 1990 by the Georgian Supreme Council. In response, South Ossetia declared independence from Georgia in 1991.

The crisis escalation led to the 1991-92 South Ossetia War.

The separatists were aided by former Soviet military units, now under Russian command. In the aftermath of the war, some parts of the former South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast remained under the Georgian control while the Tskhinvali separatist authorities (the self-proclaimed Republic of South Ossetia) were in control of one-third of the territory of the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast.

Abkhasia, on the other hand, enjoyed autonomy within Soviet Georgia e when the Soviet Union began to disintegrate in the late 1980s. Simmering ethnic tensions between the Abkhaz, the region’s “titular ethnicity,” and Georgians, the largest single ethnic group at that time, culminated in the 1992-1993 War in Abkhazia, which resulted in Georgia’s loss of control of most of Abkhazia, the de facto independence of Abkhazia, and the mass exodus and ethnic cleansing of Georgians from Abkhazia. Despite the 1994 ceasefire agreement and years of negotiations, the dispute remained unresolved.

Russian Involvement

The region of Transcaucasia lies between the Russian region of the North Caucasus and the Middle East, forming a buffer zone between Russia and the Middle East and bordering Turkey and Iran. The strategic importance of the region has made it a security concern for Russia. Significant economic reasons, such as presence or transportation of oil, also affect Russian interest in Transcaucasia. Furthermore, Russia saw the Black Sea coast and the border with Turkey as invaluable strategic attributes of Georgia. Russia had more vested interests in Abkhazia than in South Ossetia, since the Russian military presence on the Black Sea coast was seen as vital to Russian influence in the Black Sea. Before the early 2000s, South Ossetia was originally intended as a tool to retain a grip on Georgia. Support for the Abkhaz from various groups within Russia such as the Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus, Cossacks, and regular military units, and support for South Ossetia by their ethnic brethren who lived in Russia’s federal subject of North Ossetia, proved critical in the de facto secession of Abkhazia and South Ossetia from Georgia.

Vladimir Putin became president of the Russian Federation in 2000, which had a profound impact on Russo-Georgian relations. The conflict between Russia and Georgia began to escalate in 2000, when Georgia became the first and only member of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) on which the Russian visa regime was imposed. In 2001, Eduard Kokoity, an alleged member of organized crime, became de facto president of South Ossetia. He was endorsed by Russia since he would subvert the peaceful reintegration of South Ossetia into Georgia. The Russian government also began massive distribution of Russian passports to the residents of Abkhazia and South Ossetia in 2002. This “passportization” policy laid the foundation for Russia’s future claim to these territories. In 2003, Putin began to consider the possibility of a military solution to the conflict with Georgia. After Georgia deported four suspected Russian spies in 2006, Russia began a full-scale diplomatic and economic war against Georgia, accompanied by the persecution of ethnic Georgians living in Russia.

In 2008, Abkhazia and South Ossetia submitted formal requests for their recognition to Russia’s parliament. Dmitry Rogozin, Russian ambassador to NATO, warned that Georgia’s NATO membership aspirations would cause Russia to support the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The Russian State Duma adopted a resolution in which it called on the President of Russia and the government to consider the recognition.

Russo-Georgian War

By August 1, 2008, Ossetian separatists began shelling Georgian villages, with a sporadic response from Georgian peacekeepers in the region. To put an end to these attacks and restore order, the Georgian Army was sent to the South Ossetian conflict zone. Georgians took control of most of Tskhinvali, a separatist stronghold, within hours. Georgia later stated it was also responding to Russia moving non-peacekeeping units into the country. In response, Russia accused Georgia of “aggression against South Ossetia” and launched a large-scale land, air, and sea invasion of Georgia on August 8 with the stated aim of “peace enforcement” operation. Russian and Ossetian forces battled Georgian forces in and around South Ossetia for several days until they retreated. Russian and Abkhaz forces opened a second front by attacking the Kodori Gorge held by Georgia. Russian naval forces blockaded part of the Georgian coast. This was the first war in history in which cyber warfare coincided with military action. An active information war was waged during and after the conflict.

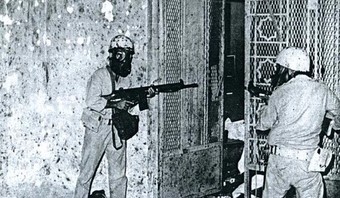

Russo-Georgian War, 2008

The war displaced 192,000 people and while many returned to their homes after the war, 20,272 people remained displaced as of 2014. Russia has, since the war, occupied Abkhazia and South Ossetia in violation of the ceasefire agreement of August 2008.

Impact

On August 17, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev (who took office in May) announced that Russian forces would begin to pull out of Georgia the following day. The two countries exchanged prisoners of war. Russian forces withdrew from the buffer zones adjacent to Abkhazia and South Ossetia in October and authority over them was transferred to the European Union monitoring mission in Georgia. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said that a military presence in Abkhazia and South Ossetia was essential to prevent Georgia from regaining control. Georgia considers Abkhazia and South Ossetia Russian-occupied territories. On August 25, 2008, the Russian parliament unanimously voted in favor of a motion urging President Medvedev to recognize Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states, and a day later Medvedev signed decrees recognizing the two states. In 2011, the European Parliament passed a resolution recognizing Abkhazia and South Ossetia as occupied Georgian territories.

The recognition by Russia was condemned by many international actors, including the United States, France, the secretary-general of the Council of Europe, NATO, and the G7 on the grounds that it violated Georgia’s territorial integrity, United Nations Security Council resolutions, and the ceasefire agreement.

Although Georgia has no significant oil or gas reserves, its territory hosts part of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline supplying Europe. The pipeline circumvents both Russia and Iran. Because it has decreased Western dependence on Middle Eastern oil, the pipeline has been a major factor in the United States’ support for Georgia.

The 2008 war was the first time since the fall of the Soviet Union that the Russian military had been used against an independent state, demonstrating Russia’s willingness to wage a full-scale military campaign to attain its political objectives. The failure of the Western security system to respond swiftly to Russia’s attempt to forcibly revise the existing borders revealed its weaknesses. Ukraine and other post-Soviet states received a clear message from the Russian leadership that the possible accession to NATO would cause a foreign invasion and the break-up of the country. The construction of the EU-sponsored Nabucco pipeline (connecting Central Asian reserves to Europe) in Transcaucasia was averted.

The war eliminated Georgia’s prospects for joining NATO.

The Georgian government severed diplomatic relations with Russia.

The war in Georgia showed Russia’s assertiveness in revising international relations and undermining the hegemony of the United States. Shortly after the war, Russian president Medvedev unveiled a five-point Russian foreign policy. The Medvedev Doctrine implied that the presence of Russian citizens in foreign countries would form a doctrinal foundation for invasion if needed. Medvedev’s statement that there were areas in which Russia had “privileged interests” underlined Russia’s particular interest in the former Soviet Union and the fact that Russia would feel endangered by subversion of local pro-Russian regimes.

Post-Soviet Russo-Ukrainian Relations

Despite being an independent country since 1991, Russia has perceived Ukraine as part of its sphere of interests. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, both states retained close ties, but tensions began almost immediately. There were several conflict points, most importantly Ukraine’s significant nuclear arsenal, which Ukraine agreed to abandon on the condition that Russia would issue an assurance against threats or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of Ukraine. A second point was the division of the Black Sea Fleet. Ukraine agreed to lease the Sevastopol port so that the Russian Black Sea fleet could continue to occupy it together with Ukraine. Furthermore, throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Ukraine and Russia engaged in several gas disputes. Russia was also further aggravated by the Orange Revolution of 2004, which saw pro-Western Viktor Yushchenko rise to power instead of pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovich. Ukraine also continued to increase its cooperation with NATO.

Pro-Russian Yanukovich was eventually elected in 2010 and Russia felt that many ties with Ukraine could be repaired. Prior to the election, Ukraine had not renewed the lease of Black Sea Naval base at Sevastopol, which meant that Russian troops would have to leave Crimea by 2017. However, Yanukovich signed a new lease allowing also troops to train in the Kerch peninsula. Many in Ukraine viewed the extension as unconstitutional because Ukraine’s constitution states that no permanent foreign troops would station in Ukraine after the Sevastopol treaty expired. Moreover, Yulia Tymoshenko, the main opposition figure of Yanukovich, was jailed on what many considered trumped-up charges, leading to further dissatisfaction with the government.

Another important factor in the tensions between Russian and Ukraine was Ukraine’s gradually closer ties with the European Union. For years, the EU promoted tight relations with Ukraine to encourage the country to take a more pro-European and less pro-Russian direction.

In 2013, Russia warned Ukraine that if it went ahead with a long-planned agreement on free trade with the EU, it would face financial catastrophe and possibly the collapse of the state. Sergey Glazyev, adviser to President Vladimir Putin, suggested that, contrary to international law, if Ukraine signed the agreement, Russia would consider the bilateral treaty that delineates the countries’ borders to be void. Russia would no longer guarantee Ukraine’s status as a state and could possibly intervene if pro-Russian regions of the country appealed directly to Russia. In 2013, Viktor Yanukovich declined to sign the agreement with the European Union, choosing closer ties with Russia.

Political Turmoil and Annexation of Crimea

After Yanukovich’s decision, months of protests as part of what would be called the Euromaidan movement followed. In February 2014, protesters ousted the government of Viktor Yanukovich, who had been democratically elected in 2010. The protesters took control of government buildings in the capital city of Kiev, along with the city itself. Yanukovich fled Kiev for Kharkiv in the east of Ukraine, where he traditionally had more support. After this incident, the Ukrainian parliament voted to restore the 2004 Constitution of Ukraine and remove Yanukovich from power. However, politicians from the traditionally pro-Russian eastern and southern regions of Ukraine, including Crimea, declared continuing loyalty to Yanukovich.

Days after Yanukovich fled Kiev, armed men opposed to the Euromaidan movement began to take control of the Crimean Peninsula. Checkpoints were established by unmarked soldiers with green military-grade uniforms and equipment in the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Simferopol, and the independently-administered port-city of Sevastopol, home to a Russian naval base. After the occupation of the Crimean parliament by these unmarked troops, with evidence suggesting that they were Russian special forces, the Crimean leadership announced it would hold a referendum on secession from Ukraine. This heavily disputed referendum was followed by the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation in mid-March. Ukraine and most of the international community refused to recognize the referendum or the annexation. On April 15, the Ukrainian parliament declared Crimea a territory temporarily occupied by Russia.

Since annexing Crimea, the Russian government increased its military presence in the region, with Russian president Vladimir Putin saying a Russian military task force would be established there. In 2014, Ukrainian Border Guard Service announced Russian troops began withdrawing from the areas of Kherson Oblast. They occupied parts of the Arabat Spit and the islands around the Syvash, which are geographically part of Crimea but administratively part of Kherson Oblast. One such village occupied by Russian troops was Strilkove, located on the Arabat Spit, which housed an important gas distribution center. Russian forces stated they took over the gas distribution center to prevent terrorist attacks. Consequently, they withdrew from southern Kherson but continued to occupy the gas distribution center outside Strilkove. In August 2016, Ukraine reported that Russia had increased its military presence along the demarcation line. Border crossings were then closed. Both sides accused each other of killings and provoking skirmishes but it remains unclear which accusations were true, with both Russia and Ukraine denying the opponent’s claims.

Unidentified gunmen on patrol at Simferopol International Airport

In September 2015 the United Nations Human Rights Office estimated that 8000 casualties had resulted from the conflict over the annexation of Crimea, noting that the violence has been “fueled by the presence and continuing influx of foreign fighters and sophisticated weapons and ammunition from the Russian Federation.”

In addition to the annexation of Crimea, an armed conflict in the Donbass region of Ukraine, known as the War in Donbass, began in March 2014. Protests by pro-Russian and anti-government groups took place in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Ukraine, together commonly called the Donbass, in the aftermath of the Euromaidan movement. These demonstrations, which followed the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation and which were part of a wider group of concurrent pro-Russian protests across southern and eastern Ukraine, escalated into an armed conflict between the separatist forces of the self-declared Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, with the support of Russian military forces and the Ukrainian government.

Since the start of the conflict, there have been 11 ceasefires, each intended to be indefinite. As of March 2017, the fighting continues.

International Response

There have been a range of international reactions to the Russian annexation of Crimea. The UN General Assembly passed a non-binding resolution 100 in favor, 11 against, and 58 abstentions in the 193-nation assembly that declared Crimea’s Moscow-backed referendum invalid.

Many countries implemented economic sanctions against Russia, Russian individuals, or companies, to which Russia responded in kind.

The United States government imposed sanctions against persons they deem to have violated or assisted in the violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty. The European Union suspended talks with Russia on economic and visa-related matters and eventually added more stringent sanctions against Russia, including asset freezes. Japan announced sanctions, which include suspension of talks relating to military, space, investment, and visa requirements. NATO condemned Russia’s military escalation in Crimea and stated that it was breach of international law, while the Council of Europe expressed its full support for the territorial integrity and national unity of Ukraine. China announced that it respected “the independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine.” A spokesman restated China’s belief of non-interference in the internal affairs of other nations and urged dialogue.

38.1.3: The Financial Crisis of 2008

In Europe, the global financial crisis of 2008 contributed to the European debt crisis and the Great Recession, which affected all the EU member-states and other European countries, resulting in the growing crisis of confidence in the idea of European integration.

Learning Objective

Recall the series of events that led to the financial crisis in 2008.

Key Points

- The financial crisis of

2008 is considered by many

economists to be the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression

of the 1930s. It began in 2007 with a crisis in the subprime mortgage market in

the United States and developed into a full-blown international banking crisis with the

collapse of the investment bank Lehman Brothers in 2008. In Europe, the global crisis contributed to the

European debt crisis and fueled a crisis in the banking system of countries using the euro. -

The European debt crisis resulted from a combination of many complex

factors. In the early 2000s, some EU

member states failed to stay within the confines of the Maastricht Treaty criteria, but some governments

managed to mask their deficit and debt levels. The

under-reporting was exposed through a revision of the forecast for the 2009

budget deficit in Greece.

The

panic escalated when Portugal, Ireland, Greece, Spain, and Cyprus were unable to repay

or refinance their government debt or bail out over-indebted banks under

their national supervision without the assistance of third parties. - The detailed causes of the

debt crisis varied. In several countries, private debts arising from a property

bubble were transferred to sovereign debt as a result of banking system bailouts

and government responses to slowing economies post-bubble. The structure of the

eurozone as a currency union without fiscal union contributed to the crisis. Also, European banks own a

significant amount of sovereign debt, so concerns regarding the solvency of

banking systems or sovereigns were negatively reinforced. -

As concerns intensified, leading European nations implemented a series of

financial support measures such as the European Financial Stability Facility

(EFSF) and European Stability Mechanism (ESM). The ECB

also contributed to solve the crisis by lowering interest rates and providing

cheap loans of more than one trillion euro to maintain money flows

between European banks. In 2012, the ECB calmed financial markets by announcing

free unlimited support for all eurozone countries involved in a sovereign state

bailout/precautionary program from EFSF/ESM. -

Many European countries embarked on austerity programs, reducing

their budget deficits relative to GDP from 2010 to 2011. However, with the exception of Germany, each

of these countries had public-debt-to-GDP ratios that increased (i.e.,

worsened) from 2010 to 2011. The crisis had significant

adverse effects on labor market, with the unemployment rates rising in

Spain, Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal, and the UK. The crisis was also blamed for subdued economic growth of the entire European Union. To fight the

crisis, some governments have also raised taxes and lowered expenditures, which

contributed to social unrest. - Despite the substantial

rise of sovereign debt in only a few eurozone countries, effectiveness of the applied measures, and relatively stable return to economic growth, the

debt crisis revealed serious weaknesses in the process of economic integration

within the EU, which in turn resulted in the general crisis of confidence

that the idea of European integration continues to witness today.

Key Terms

- European Financial Stability Facility

-

A special-purpose vehicle financed by members of the eurozone to address the European sovereign-debt crisis. It was established in 2010 with the objective of preserving financial stability in Europe by providing assistance to eurozone states in economic difficulty. Since the establishment of the European Stability Mechanism, its activities are carried out by the ESM.

- European debt crisis

-

A multi-year debt crisis that has been taking place in the European Union since the end of 2009. Several eurozone member states (Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Cyprus) were unable to repay or refinance their government debt or bail out over-indebted banks under their national supervision without the assistance of third parties like other eurozone countries, the European Central Bank (ECB), or the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

- European Stability Mechanism

-

An intergovernmental organization located in Luxembourg City, which operates under public international law for all eurozone member states that ratified a special intergovernmental treaty. It was established in 2012 as a permanent firewall for the eurozone to safeguard and provide instant access to financial assistance programs for member states of the eurozone in financial difficulty, with a maximum lending capacity of €500 billion.

- PIGS

-

An acronym used in economics and finance that originally refers, often derogatorily, to the economies of the Southern European countries of Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain. During the European debt crisis, these four EU member states were unable to refinance their government debt or bail out over-indebted banks on their own during the crisis.

- Great Recession

-

A period of general economic decline observed in world markets during the late 2000s and early 2010s. Its scale and timing varied from country to country. In terms of overall impact, the International Monetary Fund concluded that it was the worst global recession since World War II.

- Maastricht Treaty

-

A treaty undertaken to integrate Europe, signed in

1992 by the members of the European Community. Upon its entry into force in

1993, it created the European Union and led to the creation of the

single European currency, the euro. The treaty has been amended by the treaties

of Amsterdam, Nice, and Lisbon. - eurozone

-

A monetary union of 19 of the 28 European Union (EU) member states that have adopted the euro (€) as their common currency and sole legal tender.

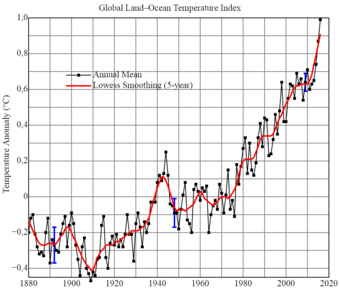

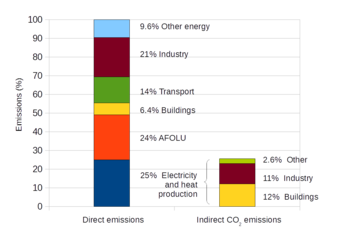

The financial crisis of 2008, also known as the global financial crisis, is considered by many economists to be the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s. It began in 2007 with a crisis in the subprime mortgage market in the United States and developed into a full-blown international banking crisis with the collapse of the investment bank Lehman Brothers in 2008. Excessive risk-taking by banks such as Lehman Brothers helped to globally magnify the financial impact. Massive bail-outs of financial institutions and other palliative monetary and fiscal policies were employed to prevent a possible collapse of the world’s financial system. The crisis was nonetheless followed by a global economic downturn, the Great Recession. In Europe, it contributed to the European debt crisis and fueled a crisis in the banking system of countries using the euro.

European Debt Crisis

The European debt crisis, known also as the eurozone crisis, resulted from a combination of complex factors, including the globalization of finance, easy credit conditions from 2002-2008 that encouraged high-risk lending and borrowing practices, the financial crisis of 2008, international trade imbalances, real estate bubbles that have since burst, the Great Recession of 2008–2012, fiscal policy choices related to government revenues and expenses, and approaches used by states to bail out troubled banking industries and private bondholders, assuming private debt burdens or socializing losses.

In 1992, members of the European Union signed the Maastricht Treaty, under which they pledged to limit their deficit spending and debt levels. However, in the early 2000s, some EU member states failed to stay within the confines of the Maastricht criteria and sidestepped best practices and international standards. Some governments managed to mask their deficit and debt levels through a combination of techniques, including inconsistent accounting, off-balance-sheet transactions, and the use of complex currency and credit derivatives structures. The under-reporting was exposed through a revision of the forecast for the 2009 budget deficit in Greece from 6-8% of GDP (according to the Maastricht Treaty, the deficit should be no greater than 3% of GDP) to 12.7%, almost immediately after the social-democratic PASOC party won the 2009 Greek national elections. Large upwards revision of budget deficit forecasts due to the international financial crisis were not limited to Greece, but in Greece the low forecast was not reported until very late in the year. The fact that the Greek debt exceeded 12% of GDP and France owned 10% of that debt struck terror among investors. The panic escalated when several eurozone member states were unable to repay or refinance their government debt or bail out over-indebted banks under their national supervision without the assistance of third parties like other eurozone countries, the European Central Bank (ECB), or the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The countries involved, most notably Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain, were collectively referred to by the derogatory acronym PIGS. During the debt crisis, Ireland replaced Italy as “I” as the acronym was originally coined to refer to the economies of Southern European countries.

The detailed causes of the debt crisis varied. In several countries, private debts arising from a property bubble were transferred to sovereign debt as a result of banking system bailouts and government responses to slowing economies post-bubble. The structure of the eurozone as a currency union (i.e., one currency) without fiscal union (e.g., different tax and public pension rules) contributed to the crisis and limited the ability of European leaders to respond. Also, European banks own a significant amount of sovereign debt, so concerns regarding the solvency of banking systems or sovereigns were negatively reinforced.

As concerns intensified in early 2010 and thereafter, leading European nations implemented a series of financial support measures such as the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and European Stability Mechanism (ESM).

The mandate of the EFSF was to “safeguard financial stability in Europe by providing financial assistance” to eurozone states. It could issue bonds or other debt instruments on the market to raise the funds needed to provide loans to eurozone countries in financial troubles, recapitalize banks, or buy sovereign debt.

The ESM was established in 2012 (taking over the functions of the EFSF) as a permanent firewall for the eurozone, to safeguard and provide instant access to financial assistance programs for member states of the eurozone in financial difficulty, with a maximum lending capacity of €500 billion.

The ECB also contributed to solve the crisis by lowering interest rates and providing cheap loans of more than one trillion euro to maintain money flows between European banks. In 2012, the ECB calmed financial markets by announcing free unlimited support for all eurozone countries involved in a sovereign state bailout/precautionary program from EFSF/ESM.

Great Recession in Europe

Many European countries, including non-EU members like Iceland, embarked on austerity programs, reducing their budget deficits relative to GDP from 2010 to 2011. For example, Greece improved its budget deficit from 10.4% GDP in 2010 to 9.6% in 2011. Iceland, Italy, Ireland, Portugal, France, and Spain also improved their budget deficits from 2010 to 2011 relative to GDP. However, with the exception of Germany, each of these countries had public-debt-to-GDP ratios that increased (i.e., worsened) from 2010 to 2011. Greece’s public-debt-to-GDP ratio increased from 143% in 2010 to 165% in 2011 to 185% in 2014. This indicates that despite improving budget deficits, GDP growth was not sufficient to support a decline (improvement) in the debt-to-GDP ratio. Eurostat reported that the debt to GDP ratio for the 17 Euro-area countries together was 70.1% in 2008, 79.9% in 2009, 85.3% in 2010, and 87.2% in 2011.

The crisis had significant adverse effects on labor market. From 2010 to 2011, the unemployment rates in Spain, Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal, and the UK increased, reaching particularly high rates (over 20%) in Spain and Greece. France had no significant changes, while in Germany and Iceland the unemployment rate declined. Eurostat reported that eurozone unemployment reached record levels in September 2012 at 11.6%, up from 10.3% the prior year, but unemployment varied significantly by country. The crisis was also blamed for subdued economic growth, not only for the entire eurozone but for the entire European Union. As such, it is thought to have had a major political impact on the ruling governments in 10 out of 19 eurozone countries, contributing to power shifts in Greece, Ireland, France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Slovenia, Slovakia, Belgium, and the Netherlands, as well as outside of the eurozone in the United Kingdom.

Poland and Slovakia are the only two members of the European Union that avoided a GDP recession during the years affected by the Great Recession.

To fight the crisis, some governments have also raised taxes and lowered expenditures. This contributed to social unrest and debates among economists, many of whom advocate greater deficits (thus no austerity measures) when economies are struggling. Especially in countries where budget deficits and sovereign debts have increased sharply, a crisis of confidence has emerged with more stable national economies attracting more investors. By the end of 2011, Germany was estimated to have made more than €9 billion out of the crisis as investors flocked to safer but near zero interest rate German federal government bonds (bunds). By mid-2012, the Netherlands, Austria, and Finland benefited from zero or negative interest rates, with Belgium and France also on the list of eventual beneficiaries.

100,000 people protest against the austerity measures in front of parliament building in Athens, May 29, 2011

On May 1, 2010, the Greek government announced a series of austerity measures (the third austerity package within months) to secure a three-year €110 billion loan. This was met with great anger by some Greeks, leading to massive protests, riots, and social unrest.

Despite the substantial rise of sovereign debt in only a few eurozone countries, with Greece, Ireland, and Portugal collectively accounting for only 6% of the eurozone’s gross domestic product (GDP), it has become a perceived problem for the area as a whole, leading to speculation of further contagion of other European countries and a possible break-up of the eurozone. In total, the debt crisis forced five out of 17 eurozone countries to seek help from other nations by the end of 2012. Due to successful fiscal consolidation and implementation of structural reforms in the countries most at risk and various policy measures taken by EU leaders and the ECB, financial stability in the eurozone has improved significantly and interest rates have steadily fallen. This has also greatly diminished contagion risk for other eurozone countries. As of October 2012, only three out of 17 eurozone countries, Greece, Portugal, and Cyprus, still battled with long-term interest rates above 6%. By early 2013, successful sovereign debt auctions across the eurozone, most importantly in Ireland, Spain, and Portugal, showed that investors believed the ECB-backstop has worked.

Return to economic growth and improved structural deficits enabled Ireland and Portugal to exit their bailout programs in mid-2014. Greece and Cyprus both managed to partly regain market access in 2014. Spain never officially received a bailout program. Its rescue package from the ESM was earmarked for a bank recapitalization fund and did not provide financial support for the government itself. Despite this progress, the debt crisis revealed serious weaknesses in the process of economic integration within the EU, which in turn resulted in the general crisis of confidence that the idea of European integration continues to witness today.

38.1.4: Austerity Measures

The austerity measures introduced as a response to the European debt crisis under the pressure of EU leadership had mixed results in terms of stabilizing European economies and a largely negative impact on ordinary Europeans, many of whom faced unemployment, lower wages, and higher taxes.

Learning Objective

Evaluate the effectiveness of the austerity measures advocated by the European Union’s leadership

Key Points

-

Austerity

is a set of economic policies that aim to demonstrate the government’s fiscal

discipline by bringing

revenues closer to expenditures. Policies grouped under the term austerity

measures generally

include cutting state spending and increasing taxes to stabilize

public finances, restore competitiveness, and create a better investment

environment. Under the pressure of European Union leadership, many European countries embarked on austerity

programs in response to their debt crisis. -

In 2010 and 2011, the Greek

government announced a series of austerity measures to secure loans from the Troika. All the implemented measures have helped Greece bring down its

primary deficit, but also worsened its recession. The Greek GDP had its

worst decline in 2011. Greeks lost much of their purchasing power, spent less on goods and services, and saw a record high seasonal adjusted unemployment rate of 27.9% in 2013. - The Irish sovereign debt

crisis arose not from government over-spending, but from the state guaranteeing

the six main Irish-based banks who financed a property bubble. Ireland initially benefited from austerity measures but subsequent

research demonstrated that its economy suffered from austerity.

Unemployment rose from 4% in 2006 to 14% by 2010, while the national budget

went from a surplus in 2007 to a deficit of 32% GDP in 2010, the highest in the

history of the eurozone. -

In 2010, the Portuguese

government announced a fresh austerity package through a series of tax hikes

and salary cuts for public servants. Also in 2010, the country reached a record

high unemployment rate of nearly 11%. In the first half of

2011, Portugal requested a €78 billion IMF-EU bailout package in a bid to

stabilize its public finances, affected greatly by decades-long government

overspending and bureaucratized civil service. After the bailout was

announced, the state’s

finances improved but unemployment

increased to over 15% in 2012. The bail-out conditions of austerity also

created a political crisis. - Spain initiated an austerity program consisting primarily of tax

increases. Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy announced on in 2012 €65 billion of

austerity, including cuts in wages and benefits and a VAT increase from 18% to

21%. The government eventually reduced its budget deficit from

11.2% of GDP in 2009 to 8.5% in 2011. Due to reforms already instituted by Spain’s

conservative government, less stringent austerity requirements were included. -

There

has been substantial criticism of the austerity measures implemented by most

European nations to counter the debt crisis, with economists predicting that the timing and level of austerity would only worsen the recession. As ordinary citizens paid the highest cost for the measures, including high unemployment, lower wages, and higher taxes, protests against austerity broke out across Europe.

Key Terms

- European debt crisis

-

A multi-year debt crisis in the European Union since the end of 2009. Several

eurozone member states (Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Cyprus)

were unable to repay or refinance their government debt or bail out

over-indebted banks under their national supervision without the assistance of

third parties like other eurozone countries, the European Central

Bank (ECB), or the International Monetary Fund (IMF). - Troika

-

The designation of the triumvirate representing the European Union in its foreign relations, in particular concerning its common foreign and security policy (CFSP). Currently, the term is used to refer to a decision group formed by the European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

- austerity

-

A set of economic policies that aim to demonstrate the government’s fiscal discipline, usually to creditors and credit rating agencies, by bringing revenues closer to expenditures. Policies grouped under the term generally include cutting the state’s spending and increasing taxes to stabilize public finances, restore competitiveness, and create better investment expectation.

Austerity is a set of economic policies that aim to

demonstrate the government’s fiscal discipline, usually to creditors and credit rating agencies, by bringing revenues closer to expenditures.

Policies considered austerity measures generally include cutting the state’s spending and increasing taxes to stabilize public finances, restore competitiveness, and create a better investment environment.

A typical goal of austerity is to reduce the annual budget deficit without sacrificing growth. Over time, this may reduce the overall debt burden, often measured as the ratio of public debt to GDP.

Under the pressure of the European Union leadership, many European countries embarked on austerity programs in response to the European debt crisis, despite evidence that overspending was only to a certain extent in some cases responsible for the unfolding economic disaster. However, austerity measures became the main condition under which the eurozone countries in the most dramatic economic situation, most notably Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain, would receive financial support from the Troika,

a tripartite committee formed by the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (EC, ECB and IMF).

Response to European Debt Crisis

On May 1, 2010, the Greek government announced a series of austerity measures to secure a three-year €110 billion loan. The Troika offered Greece a second bailout loan worth €130 billion in October 2011, but with activation conditional on implementation of further austerity measures and a debt restructuring agreement. All the implemented measures have helped Greece bring down its primary deficit but contributed to a worsening of its recession. The Greek GDP had its worst decline in 2011, when 111,000 Greek companies went bankrupt (27% higher than in 2010). As a result, Greeks lost about 40% of their purchasing power since the start of the crisis, spent 40% less on goods and services, and experienced a record high seasonal adjusted unemployment rate that grew from 7.5% in September 2008 to a record high of 27.9% in June 2013. The youth unemployment rate rose from 22% to as high as 62%.

In February 2012, an IMF official negotiating Greek austerity measures admitted that excessive spending cuts were harming Greece. The IMF predicted the Greek economy to contract by 5.5 % by 2014. Harsh austerity measures led to an actual contraction after six years of recession of 17%.

The Irish sovereign debt crisis arose not from government over-spending, but from the state guaranteeing the six main Irish-based banks who had financed a property bubble. Irish banks had lost an estimated 100 billion euros, much of it related to defaulted loans to property developers and homeowners made in the midst of the bubble, which burst around 2007. The economy subsequently collapsed in 2008.

Ireland was one country that initially benefited from austerity measures but subsequent research demonstrated that its economy suffered from austerity. Unemployment rose from 4% in 2006 to 14% by 2010, while the national budget went from a surplus in 2007 to a deficit of 32% GDP in 2010, the highest in the history of the eurozone.

In 2009, the Portuguese deficit was 9.4%, one of the highest in the eurozone.

In 2010, the Portuguese government announced a fresh austerity package through a series of tax hikes and salary cuts for public servants. Also in 2010, the country reached a record high unemployment rate of nearly 11%, a figure not seen for over two decades, while the number of public servants remained very high. In the first half of 2011, Portugal requested a €78 billion IMF-EU bailout package in a bid to stabilize its public finances, affected greatly by decades-long governmental overspending and an over-bureaucratized civil service. After the bailout was announced, the government managed to implement measures to improve the state’s financial situation and seemed to be on the right track. This, however, led to a strong increase of the unemployment rate to over 15% in 2012. The bail-out conditions of austerity also created a political crisis in the country, resolved in 2015 with the anti-austerity left-wing coalition leading the country.

Spain entered the crisis period with a relatively modest public debt of 36.2% of GDP. This was largely due to ballooning tax revenue from the housing bubble, which helped accommodate a decade of increased government spending without debt accumulation. In response to the crisis, Spain initiated an austerity program consisting primarily of tax increases. Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy announced in 2012 €65 billion of austerity, including cuts in wages and benefits and a VAT increase from 18% to 21%. The government eventually reduced its budget deficit from 11.2% of GDP in 2009 to 8.5% in 2011.

A larger economy than other countries that received bailout packages, Spain had considerable bargaining power regarding the terms of a bailout. Due to reforms already instituted by Spain’s conservative government, less stringent austerity requirements were included than in earlier bailout packages for Ireland, Portugal, and Greece.

“Education not Emigration” – a poster for the national student march in 2010 in Ireland.

A student demonstration took place in Dublin on November 3, 2010, in opposition to a proposed increase in university registration fees, further cuts to the student maintenance grant, and increasing graduate unemployment and emigration levels. Organized by the Union of Students in Ireland (USI) and student unions nationwide, it saw between 25,000 and 40,000 protesters on the streets of central Dublin during what “the largest student protest for a generation.”

Economic Debates on Austerity

There has been substantial criticism over the austerity measures implemented by most European nations to counter this debt crisis. U.S. economist and Nobel laureate Paul Krugman argued that the deflationary policies imposed on countries such as Greece and Spain would prolong and deepen their recessions. Together with over 9,000 signatories of A Manifesto for Economic Sense, Krugman also dismissed the belief of austerity-focusing policy makers that “budget consolidation” revives confidence in financial markets over the longer haul.

According to some economists, “growth-friendly austerity” relies on the false argument that public cuts would be compensated for by more spending from consumers and businesses, a theoretical claim that has not materialized. The case of Greece shows that excessive levels of private indebtedness and a collapse of public confidence (over 90% of Greeks fear unemployment, poverty, and the closure of businesses) led the private sector to decrease spending in an attempt to save up for rainy days ahead. This led to even lower demand for both products and labor, which further deepened the recession and made it even more difficult to generate tax revenues and fight public indebtedness.

Some economists also criticized the timing and amount of austerity measures in the bailout programs, arguing that such extensive measures should not be implemented during the crisis years with an ongoing recession, but delayed until after some positive real GDP growth returns. In 2012, a report published by the IMF also found that tax hikes and spending cuts during the most recent decade indeed damaged the GDP growth more severely compared to forecasts.

Social Impact of Austerity Measures

Opponents of austerity measures argue that they depress economic growth and ultimately cause reduced tax revenues that outweigh the benefits of reduced public spending. Moreover, in countries with already anemic economic growth, austerity can engender deflation, which inflates existing debt. Such austerity packages can also cause the country to fall into a liquidity trap, causing credit markets to freeze up and unemployment to increase.

Supporting the conclusions of these macroeconomic models, austerity measures applied during the European debt crisis negatively affected ordinary citizens. The outcomes of introducing harsh austerity measures included the rapid increase of unemployment as government spending fell, reducing jobs in the public and/or private sector; the reduction of household disposable income through tax increases, which in turn reduced spending and consumption; and the bankruptcy of many small businesses, which contributed to even more unemployment and lowered already low productivity.

Apart from arguments over whether or not austerity, rather than increased or frozen spending, is a macroeconomic solution, union leaders argued that the working population was unjustly held responsible for the economic mismanagement errors of economists, investors, and bankers. Over 23 million EU workers became unemployed as a consequence of the global economic crisis of 2007-2010, leading many to call for additional regulation of the banking sector across not only Europe, but the entire world.

The anti-austerity protests in Greece in 2010 and 2011

Anti-austerity activists demonstrated in major cities across Greece. Some of the events later turned violent, particularly in the capital city of Athens. Inspired by the anti-austerity protests in Spain, these demonstrations were organized entirely using social networking sites, which earned it the nickname “May of Facebook.”

Following the announcement of plans to introduce austerity measures in Greece, massive demonstrations occurred throughout the country aimed at pressing parliamentarians to vote against the austerity package. In Athens alone, 19 arrests were made, while 46 civilians and 38 policemen were injured by the end of June 2011. The third round of austerity was approved by the Greek parliament in 2012 and met strong opposition, especially in Athens and Thessaloniki, where police clashed with demonstrators. Similar protests took place in Spain and Ireland, led by student communities.

The ethics of austerity have been questioned in recent years outside of the European states hit by the harshest measures as a result of the bail-out conditions. For example, the Royal Society of Medicine revealed that the United Kingdom’s austerity measures in healthcare may have resulted in 30,000 deaths in England and Wales in 2015.

38.1.5: The Refugee Crisis

As millions of refugees escape wars and persecution in their home countries and flee to Europe, both the European Union and the larger European community have been testing the limits of integration and solidarity as some countries accept— and others refuse— the responsibility to deal with the crisis.

Learning Objective

Discuss the origins and scope of the current refugee crisis

Key Points

-

Movement across Europe is

largely regulated by the Schengen Agreement, by which 26 countries formed an area where border checks between

the member states are abolished and checks are

restricted to the external Schengen borders. Carriers that transport people into the Schengen area

are, if they transport people who are refused entry, responsible to pay for the return of the refused people and additional penalties. Many migrants attempt to travel illegally. Those who have basis to seek asylum in the EU face

the rules of the Dublin Regulation, which determines the EU member state

responsible for examining an asylum application. -

According to the United

Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the number of forcibly

displaced people worldwide reached 59.5 million in 2014, which includes 19.5 million

refugees and 1.8 million asylum seekers. Among

them, Syrian refugees became the largest group in 2014. Developing nations, not Western countries, hosted the largest share of refugees (86% by the end of 2014). Most of the people arriving in Europe in 2015 were leeing war and

persecution in countries such as Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Eritrea. Wars fueling the crisis are the

Syrian Civil War, the Iraq War, the War in Afghanistan, the War in Somalia, and

the War in Darfur. -

Amid an upsurge in the

number of sea arrivals in Italy from Libya in 2014, several European Union

governments refused to fund the Italian-run rescue option Operation Mare

Nostrum, which was replaced by Frontex’s Operation Triton. The latter involves

voluntary contributions from 15 other European nations. The Italian government requested additional funds from the other EU member states, but they did not

offer the requested support. In 2015, Greece

overtook Italy as the first EU country of arrival, becoming the starting point of a flow of refugees and migrants moving to northern European countries, mainly Germany and Sweden. -

Since April 2015, the

European Union has struggled to cope with the crisis, increasing funding for

border patrol operations in the Mediterranean, devising plans to fight migrant

smuggling, launching Operation Sophia with the aim of neutralizing established

refugee smuggling routes in the Mediterranean, and proposing a new quota system

to relocate asylum seekers among EU states. - Individual

countries have at times reintroduced border controls within the Schengen area

and rifts have emerged between countries willing to allow entry of asylum

seekers for processing of refugee claims and those trying to

discourage their entry for processing. Germany, Hungary, Sweden, and

Austria received around two-thirds of the EU’s asylum applications in 2015,

with Hungary, Sweden, and Austria the top recipients per capita. Germany has been the most sought-after final

destination in the EU migrant and refugee crisis. -

The escalation of

shipwrecks of migrant boats in the Mediterranean in 2015 led European Union

leaders to reconsider their policies on border control and processing of

migrants. The European

Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker proposed to distribute 160,000 asylum

seekers among EU states under a new migrant quota system. By September 2016, the quota system

proposed by EU was abandoned after resistance by Visegrad Group

countries. The refugee crisis also fueled nationalist sentiments across Europe

and the appeal of politicians who oppose the idea of European integration.

Key Terms

- refugee

-

Legally, a person who has left his or her country of origin because of well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, and is unable to return or avail themselves of that country’s protection.

- Operation Triton

-

A border security operation conducted by Frontex, the European Union’s border security agency. The operation, under Italian control, began in 2014 and involves voluntary contributions from 15 other European nations (both EU member states and non-members). It was undertaken after Italy ended Operation Mare Nostrum, which had become too costly for a single country to fund. The Italian government requested additional funds from the other EU member states but they refused.

- asylum seeker

-

A person who flees his or her home country and “spontaneously” enters another country and applies for asylum, i.e. the right to international protection. A person attains this status by making a formal application for the right to remain in another country and keeps that status until the application has been concluded.

- Schengen Agreement

-

A treaty which led to the creation of an area of Europe where internal border checks have largely been abolished. It was signed in 1985 by five of the ten member states of the European Economic Community. It proposed measures intended to gradually abolish border checks at the signatories’ common borders, including reduced speed vehicle checks that allowed vehicles to cross borders without stopping, freedom for residents in border areas to cross borders away from fixed checkpoints, and the harmonization of visa policies.

- Dublin Regulation

-

A European Union (EU) law that determines the EU member state responsible to examine an application for asylum seekers of international protection under the Geneva Convention and the EU Qualification Directive within the European Union.

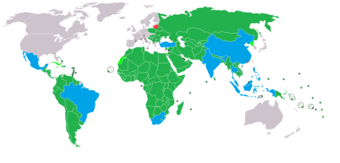

Background: EU and Migration

Movement across Europe is largely regulated by the Schengen Agreement, by which 26 European countries (22 of the 28 European Union member states, plus

Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland) joined to form an area where border checks between the 26 member states (internal Schengen borders) are abolished and checks are restricted to the external Schengen borders. Countries with external borders are obligated to enforce border control regulations. Countries may reinstate internal border controls for a maximum of two months for “public policy or national security” reasons.