33.1: Independence in the Maghreb

33.1.1: French West Africa’s Move Toward Independence

French West Africa was a federation of eight French colonial territories in Africa that existed from 1895 until 1960, when the colonies established independence from France.

Learning Objective

Describe the move towards independence in French West Africa

Key Points

- As the French pursued their part in the “scramble for Africa” in the 1880s and 1890s, they conquered large inland areas and soon dubbed them “Military Territories.”

- In the late 1890s, the French government began to rein in the territorial expansion of the military officers in charge of these territories and transferred all the territories west of Gabon to a single governor based in Senegal.

- These territories were formally named French West Africa.

- Until after the Second World War, almost no Africans living in the colonies of France were citizens of France; rather, they were “French Subjects,” lacking rights before the law, property ownership rights, and the rights to travel, dissent, or vote.

- Following World War II, the French government began extending limited political rights in its colonies, such as including some African subjects in the governing bodies of the colonies and giving limited citizenship rights to natives.

- In 1960, a further revision of the French constitution, compelled by the failure of the French Indochina War and the tensions in Algeria, allowed members of the French Community (the successor to the French colonial empire) to unilaterally change their own constitutions, resulting in the end of French West Africa.

Key Terms

- French Subjects

-

Residents of French colonies who unlike French citizens, lacked rights before the law, property ownership rights, and the rights to travel, dissent, or vote.

- Protectorate

-

A dependent territory that has been granted local autonomy and some independence while still retaining the suzerainty of a greater sovereign state.

- scramble for Africa

-

The invasion, occupation, division, colonization, and annexation of African territory by European powers during the period of New Imperialism, between 1881 and 1914.

French West Africa was a federation of eight French colonial territories in Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guinea (now Guinea), Côte d’Ivoire, Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso), Dahomey (now Benin), and Niger. The capital of the federation was Dakar. The federation existed from 1895 until 1960.

Background: French Colonial Empire

The French colonial empire constituted the overseas colonies, protectorates, and mandate territories under French rule from the 16th century onward. A distinction is made between the “first colonial empire,” which was mostly lost by 1814, and the “second colonial empire,” which began with the conquest of Algiers in 1830. The second empire came to an end after the loss of bitter wars in Vietnam (1955) and Algeria (1962), and peaceful decolonization elsewhere after 1960.

The French colonial empire began to fall during the Second World War, when various parts were occupied by foreign powers (Japan in Indochina, Britain in Syria, Lebanon, and Madagascar, the USA and Britain in Morocco and Algeria, and Germany and Italy in Tunisia). However, control was gradually reestablished by Charles de Gaulle. The French Union, included in the Constitution of 1946, nominally replaced the former colonial empire, but officials in Paris remained in full control. The colonies were given local assemblies with only limited local power and budgets. A group of elites known as evolués emerged: natives of the overseas territories who lived in metropolitan France.

The French Union was replaced in the new Constitution of 1958 by the French Community. Only Guinea refused by referendum to take part in the new colonial organization. However, the French Community dissolved itself in the midst of the Algerian War; almost all of the other African colonies were granted independence in 1960 with local referendums. A few colonies chose instead to remain part of France under the status of overseas territories. Robert Aldrich argues that with Algerian independence in 1962, the Empire had practically come to an end, as the remaining colonies were quite small and lacked active nationalist movements.

Rights and Representation in French Territories

As the French pursued their part in the “scramble for Africa” in the 1880s and 1890s, they conquered large inland areas, at first ruling them as either a part of the Senegal colony or as independent entities. These conquered areas were usually governed by French Army officers and dubbed “Military Territories.” In the late 1890s, the French government began to rein in the territorial expansion of its “officers on the ground” and transferred all the territories west of Gabon to a single Governor based in Senegal reporting directly to the Minister of Overseas Affairs. The first Governor General of Senegal was named in 1895, and in 1904, the territories he oversaw were formally named French West Africa (AOF). Gabon would later become the seat of its own federation French Equatorial Africa (AEF), to border its western neighbor on the modern boundary between Niger and Chad.

Until after the Second World War, almost all Africans living in the colonies of France were not citizens of France. Rather, they were “French Subjects,” lacking rights before the law, property ownership rights, and the rights to travel, dissent, or vote. The exception were the Four Communes of Senegal; those areas had been towns of the tiny Senegal Colony in 1848 when, at the abolition of slavery by the French Second Republic, all residents of France were granted equal political rights. Anyone able to prove they were born in these towns was legally French. They could vote in parliamentary elections, previously dominated by white and Métis residents of Senegal.

The Four Communes of Senegal were entitled to elect a Deputy to represent them in the French Parliament in the years 1848–1852, 1871–1876, and 1879–1940. In 1914, the first African, Blaise Diagne, was elected as the Deputy for Senegal in the French Parliament. In 1916, Diagne pushed through the National Assembly a law (Loi Blaise Diagne) granting full citizenship to all residents of the so-called Four Communes. In return, he promised to help recruit millions of Africans to fight in World War I. Thereafter, all black Africans of Dakar, Gorée, Saint-Louis, and Rufisque could vote to send a representative to the French National Assembly.

After the Fall of France during World War II in June 1940 and the two battles of Dakar against the Free French Forces in July and September 1940, authorities in West Africa declared allegiance to the Vichy regime, as did the colony of French Gabon in AEF. While the latter fell to Free France already after the Battle of Gabon in November 1940, West Africa remained under Vichy control until the Allied landings in North Africa (operation Torch) in November 1942.

French West Africa

A “Section Chief” in the building of the Dakar–Niger Railway, pushed by African workers, Kayes, Mali, 1904

Toward Independence

Following World War II, the French government began extending limited political rights in its colonies. In 1945 the French Provisional Government allocated ten seats to French West Africa in the new Constituent Assembly, called to write a new French Constitution. Of these, five would be elected by citizens (which only in the Four Communes could an African hope to win) and five by African subjects. The elections brought to prominence a new generation of French-educated Africans. On October 21, 1945 six Africans were elected: the Four Communes citizens chose Lamine Guèye, Senegal/Mauritania Léopold Sédar Senghor, Côte d’Ivoire/Upper Volta Félix Houphouët-Boigny, Dahomey/Togo Sourou-Migan Apithy, Soudan-Niger Fily Dabo Sissoko, and Guinea Yacine Diallo. They were all re-elected to the 2nd Constituent Assembly on June 2, 1946.

In 1946, the Loi Lamine Guèye granted limited citizenship rights to natives of the African colonies. The French Empire was renamed the French Union on October 27, 1946, when the new constitution of the French Fourth Republic was established. In late 1946 under this new constitution, each territory was for the first time (excepting the Four Communes) able to elect local representatives, albeit on a limited franchise, to newly established General Councils. These elected bodies had limited consultative powers, although they did approve local budgets. The Loi Cadre of June 23, 1956 brought universal suffrage to elections held after that date in all French African colonies. The first elections under universal suffrage in French West Africa were the municipal elections of late 1956. On March 31, 1957, under universal suffrage, territorial Assembly elections were held in each of the eight colonies (Togo as a UN trust Territory was by this stage on a different trajectory). The leaders of the winning parties were appointed to the newly instituted positions of Vice-Presidents of the respective Governing Councils — French Colonial Governors remained as Presidents.

The Constitution of the French Fifth Republic of 1958 again changed the structure of the colonies from the French Union to the French Community. Each territory was to become a “Protectorate,” with the consultative assembly named a National Assembly. The Governor appointed by the French was renamed the “High Commissioner” and made head of state of each territory. The Assembly would name an African as Head of Government with advisory powers to the Head of State. Legally, the federation ceased to exist after the September 1958 referendum to approve this French Community. All the colonies except Guinea voted to remain in the new structure. Guineans voted overwhelmingly for independence. In 1960, a further revision of the French constitution, compelled by the failure of the French Indochina War and the tensions in Algeria, allowed members of the French Community to unilaterally change their own constitutions. Senegal and former French Sudan became the Mali Federation (1960–61), while Côte d’Ivoire, Niger, Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso) and Dahomey (now Benin) subsequently formed the short-lived Sahel-Benin Union, later the Conseil de l’Entente.

33.1.2: The Algerian War of Independence

The Algerian War of Independence was a war between France and the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) from 1954 to 1962, which led to Algeria’s independence from France and was infamous for the extensive use of torture by both sides.

Learning Objective

Argue for and against the tactics used by the FLN in order to gain independence

Key Points

- In 1834, Algeria became a French military colony and, in 1848, was declared by the constitution of 1848 to be an integral part of France.

- The Algerian War was fought between France and the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) between 1954 and 1962 and was characterized by complex guerrilla warfare and the extensive use of torture by both sides.

- The conflict started in the early morning hours of November 1, 1954, when FLN guerrillas attacked military and civilian targets throughout Algeria in what became known as the Toussaint Rouge (Red All-Saints’ Day).

- The FLN turned to killing civilians during the Philippeville Massacre, which brought on harsh retaliation by the French army.

- After major demonstrations in favor of independence from the end of 1960 and a United Nations resolution recognizing the right to independence, De Gaulle decided to open a series of negotiations with the FLN, which concluded with the signing of the Évian Accords on March 1962.

Key Terms

- “scorched earth”

-

A military strategy that targets anything that might be useful to the enemy while advancing through or withdrawing from an area. Specifically, all of the assets that are used or can be used by the enemy are targeted, such as food sources, transportation, communications, industrial resources, and even the people in the area.

- Pieds-Noirs

-

A term referring to Christian and Jewish people whose families migrated from all parts of the Mediterranean to French Algeria, the French protectorate in Morocco, or the French protectorate of Tunisia, where many lived for several generations before being expelled at the end of French rule in North Africa between 1956 and 1962.

- guerrilla warfare

-

A form of irregular warfare in which a small group of combatants such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactics, and mobility to fight a larger and less-mobile traditional military.

Overview

The Algerian War, also known as the Algerian War of Independence or the Algerian Revolution, was a war between France and the Algerian National Liberation Front (French: Front de Libération Nationale – FLN) from 1954 to 1962 and led to Algerian independence from France. An important decolonization war, this complex conflict was characterized by guerrilla warfare, maquis fighting, and the use of torture by both sides. The conflict also became a civil war between loyalist Algerians supporting a French Algeria and their Algerian nationalist counterparts.

Effectively started by members of the National Liberation Front on November 1, 1954, during the Toussaint Rouge (“Red All Saints’ Day”), the conflict shook the foundations of the weak and unstable Fourth French Republic (1946–58) and led to its replacement by the Fifth Republic with Charles de Gaulle as President. Although the French military campaigns greatly weakened the FLN’s military, with most prominent FLN leaders killed or arrested and terror attacks effectively stopped, the brutality of the methods employed by the French forces failed to win hearts and minds in Algeria, alienated support in metropolitan France, and discredited French prestige abroad.

After major demonstrations in favor of independence from the end of 1960 and a United Nations resolution recognizing the right to independence, De Gaulle decided to open a series of negotiations with the FLN, concluding with the signing of the Évian Accords on March 1962. A referendum took place on April 8, 1962 and the French electorate approved the Évian Accords. The final result was 91% in favor of the ratification of this agreement and on July 1, the Accords were subject to a second referendum in Algeria, where 99.72% voted for independence and just 0.28% against.

The planned French withdrawal led to a state crisis, various assassination attempts on de Gaulle, and attempts at military coups. Most of the former were carried out by the Organisation de l’armée secrète (OAS), an underground organization formed mainly from French military personnel supporting a French Algeria, which committed a large number of bombings and murders both in Algeria and in the homeland to stop the planned independence.

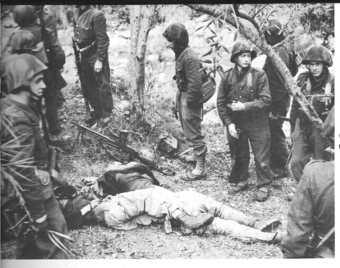

Algerian War

French forces killed Algerian rebels, December 1954

Philippeville Massacre

The FLN adopted tactics similar to those of nationalist groups in Asia, and the French did not realize the seriousness of the challenge they faced until 1955 when the FLN moved into urbanized areas. An important watershed in the War of Independence was the massacre of Pieds-Noirs civilians by the FLN near the town of Philippeville (now known as Skikda) in August 1955. Before this operation, FLN policy was to attack only military and government-related targets. The commander of the Constantine region, however, decided a drastic escalation was needed. The killing by the FLN and its supporters of 123 civilians, elderly women, and babies, including 71 French, shocked Governor General Jacques Soustelle into calling for more repressive measures against the rebels. The government claimed it killed 1,273 guerrillas in retaliation; according to the FLN and to The Times, 12,000 Algerians were massacred by the armed forces and police as well as Pieds-Noirs gangs. Soustelle’s repression was an early cause of the Algerian population’s rallying to the FLN. After Philippeville, Soustelle declared sterner measures and an all-out war began. In 1956, demonstrations by French Algerians caused the French government to not make reforms.

Guerrilla Warfare

During 1956 and 1957, the FLN successfully applied hit-and-run tactics in accordance with guerrilla warfare theory. Whilst some was aimed at military targets, a significant amount was invested in a terror campaign against those deemed to support or encourage French authority. This resulted in acts of sadistic torture and brutal violence against all, including women and children. Specializing in ambushes and night raids and avoiding direct contact with superior French firepower, the internal forces targeted army patrols, military encampments, police posts, and colonial farms, mines, and factories, as well as transportation and communications facilities. Once an engagement was broken off, the guerrillas merged with the population in the countryside, in accordance with Mao’s theories. Kidnapping was commonplace, as were the ritual murder and mutilation of civilians. At first, the FLN targeted only Muslim officials of the colonial regime; later, they coerced, maimed, or killed village elders, government employees, and even simple peasants who refused to support them. Throat slitting and decapitation were commonly used by the FLN as mechanisms of terror. During the first two-and-a-half years of the conflict, the guerrillas killed an estimated 6,352 Muslim and 1,035 non-Muslim civilians.

Although successfully provoking fear and uncertainty within both communities in Algeria, the revolutionaries’ coercive tactics suggested they had not yet inspired the bulk of the Muslim people to revolt against French colonial rule. Gradually, however, the FLN gained control in certain sectors of the Aurès, the Kabylie, and other mountainous areas around Constantine and south of Algiers and Oran. In these places, the FLN established a simple but effective—although frequently temporary—military administration that was able to collect taxes and food and recruit manpower, but was unable to hold large, fixed positions.

Guerilla Warfare

Muslim civilians killed by the FLN, March 22, 1956

French Use of Torture

Torture was used since the beginning of the colonization of Algeria, initiated by the July Monarchy in 1830. Directed by Marshall Bugeaud, who became the first Governor-General of Algeria, the conquest of Algeria was marked by a “scorched earth” policy and the use of torture, e legitimized by a racist ideology. The armed struggle of the FLN and of its armed wing, the Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN) was for self-determination. The French state itself refused to see the colonial conflict as a war, as that would recognize the other party as a legitimate entity. Thus, until August 10, 1999, the French Republic persisted in calling the Algerian War a simple “operation of public order” against the FLN “terrorism.” Thus, the military did not consider themselves tied by the Geneva Conventions, ratified by France in 1951.

Violence increased on both sides from 1954 to 1956. In 1957, the Minister of Interior declared a state of emergency in Algeria, and the government granted extraordinary powers to General Massu. The Battle of Algiers from January to October 1957 remains to this day a textbook example of counter-insurgency operations. General Massu’s 10th Paratroop Division made widespread use of methods used during the Indochina War (1947–54), including systematic use of torture against civilians, a block warden system (quadrillage), illegal executions, and forced disappearances, in particular through what would later become known as “death flights,” in which victims are dropped to their death from airplanes or helicopters into large bodies of water. Although the use of torture quickly became well-known and was opposed by the left-wing opposition, the French state repeatedly denied its employment, censoring more than 250 books, newspapers and films (in metropolitan France alone) which dealt with the subject and 586 in Algeria.

33.1.3: Moroccan Independence

France’s exile of Sultan Mohammed V in 1953 to Madagascar and his replacement by the unpopular Mohammed Ben Aarafa sparked active opposition to French and Spanish rule and led to Moroccan independence in 1956.

Learning Objective

Order the events that led to Moroccan independence

Key Points

- The French Protectorate in Morocco was established by the Treaty of Fez in 1912.

- Between 1921 and 1926, a Berber uprising in the Rif Mountains led by Abd el-Krim led to the establishment of the Republic of the Rif; the rebellion was eventually suppressed by French and Spanish troops.

- In 1943, the Istiqlal Party (Independence Party) was founded to press for independence with discreet US support; that party subsequently provided most of the leadership for the nationalist movement.

- France’s exile of Sultan Mohammed V in 1953 to Madagascar and his replacement by the unpopular Mohammed Ben Aarafa sparked active opposition to the French and Spanish protectorates.

- France allowed Mohammed V to return in 1955, and the negotiations that led to Moroccan independence began the following year.

- In March 1956 the French protectorate was ended and Morocco regained its independence from France as the “Kingdom of Morocco.”

Key Terms

- protectorate

-

A dependent territory that has been granted local autonomy and some independence while retaining the suzerainty of a greater sovereign state. Unlike colonies, they have local rulers and experience rare cases of immigration of settlers from the country it has suzerainty of.

- Atlantic Charter

-

A pivotal policy statement issued on August 14, 1941, that defined the Allied goals for the post-WWII world, including no territorial aggrandizement; no territorial changes made against the wishes of the people; self-determination; restoration of self-government to those deprived of it; reduction of trade restrictions; global cooperation to secure better economic and social conditions for all; freedom from fear and want; freedom of the seas; and abandonment of the use of force, as well as disarmament of aggressor nations.

- Rif War

-

Also called the Second Moroccan War, this war was fought in the early 1920s between the colonial power Spain (later joined by France) and the Berbers of the Rif mountainous region.

French and Spanish Rule in Morocco

As Europe industrialized, North Africa was increasingly prized for its potential for colonization. France showed a strong interest in Morocco as early as 1830, not only to protect the border of its Algerian territory but also because of the strategic position of Morocco on two oceans. In 1860, a dispute over Spain’s Ceuta enclave led Spain to declare war. Victorious Spain won a further enclave and an enlarged Ceuta in the settlement. In 1884, Spain created a protectorate in the coastal areas of Morocco.

In 1904, France and Spain carved out zones of influence in Morocco. Recognition by the United Kingdom of France’s sphere of influence provoked a strong reaction from the German Empire, and a crisis loomed in 1905. The matter was resolved at the Algeciras Conference in 1906. The Agadir Crisis of 1911 increased tensions between European powers. The 1912 Treaty of Fez made Morocco a protectorate of France, triggering the 1912 Fez riots. From a legal point of view, the treaty did not deprive Morocco of its status as a sovereign state as the Sultan reigned but did not rule. Spain continued to operate its coastal protectorate. By the same treaty, Spain assumed the role of protecting power over the northern and southern Saharan zones.

Tens of thousands of colonists entered Morocco. Some bought large amounts of the rich agricultural land, while others organized the exploitation and modernization of mines and harbors. Interest groups that formed among these elements continually pressured France to increase its control over Morocco – a control which was also made necessary by the continuous wars among Moroccan tribes, part of which had taken sides with the French since the beginning of the conquest. Governor General Marshall Hubert Lyautey sincerely admired Moroccan culture and succeeded in imposing a joint Moroccan-French administration while creating a modern school system. Several divisions of Moroccan soldiers served in the French army in both World War I and World War II, and in the Spanish Nationalist Army in the Spanish Civil War and after. The institution of slavery was abolished in 1925.

Moroccan Resistance

Sultan Yusef’s reign from 1912 to 1927 was turbulent and marked with frequent uprisings against Spain and France. The most serious of these was a Berber uprising in the Rif Mountains called the Rif War, led by Abd al-Karim who at first inflicted several defeats on the Spanish forces by using guerrilla tactics and captured European weapons and managed to establish a republic in the Rif. Though this rebellion originally began in the Spanish-controlled area in the north of the country, it reached the French-controlled area until a coalition of France and Spain finally defeated the rebels in 1925. To ensure their own safety, the French moved the court from Fez to Rabat, which has served as the capital of the country ever since.

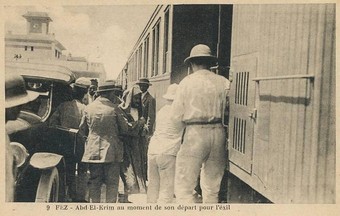

Rif Rebellion

Abd al-Karim boarding a train in Fez on his way to exile after the Rif Rebellion was defeated in 1925.

In December 1934, a small group of nationalists, members of the newly formed Moroccan Action Committee, proposed a Plan of Reforms that called for a return to indirect rule as envisaged by the Treaty of Fez, admission of Moroccans to government positions, and establishment of representative councils. The Action Committee used moderate tactics to suggest reforms including petitions, newspaper editorials, and personal appeals to French. Nationalist political parties, which subsequently arose under the French protectorate, based their arguments for Moroccan independence on World War II declarations such as the Atlantic Charter.

Toward Independence

During World War II, the badly divided nationalist movement became more cohesive, and informed Moroccans dared to consider the real possibility of political change in the post-war era. However, the nationalists were disappointed in their belief that the Allied victory in Morocco would pave the way for independence. In January 1944, the Istiqlal Party, which subsequently provided most of the leadership for the nationalist movement, released a manifesto demanding full independence, national reunification, and a democratic constitution. The sultan approved the manifesto before its submission to the French resident general, who answered that no basic change in the protectorate status was being considered.

The general sympathy of the sultan for the nationalists was evident by the end of the war, although he still hoped to see complete independence achieved gradually. By contrast, the residency, supported by French economic interests and vigorously backed by most of the colonists, adamantly refused to consider even reforms short of independence. Official intransigence contributed to increased animosity between the nationalists and the colonists and gradually widened the split between the sultan and the resident general.

Mohammed V and his family were transferred to Madagascar in January 1954. His replacement by the unpopular Mohammed Ben Aarafa, whose reign was perceived as illegitimate, sparked active opposition to the French protectorate both from nationalists and those who saw the sultan as a religious leader. By 1955, Ben Arafa was pressured to abdicate; consequently, he fled to Tangier where he formally abdicated. The most notable violence occurred in Oujda where Moroccans attacked French and other European residents in the streets. France allowed Mohammed V to return in 1955, and the negotiations that led to Moroccan independence began the following year. In March 1956 the French protectorate was ended and Morocco regained its independence from France as the “Kingdom of Morocco.”

A month later, Spain ceded most of its protectorate in Northern Morocco to the new state but kept its two coastal enclaves (Ceuta and Melilla) on the Mediterranean coast. In the months that followed independence, Mohammed V proceeded to build a modern government structure under a constitutional monarchy in which the sultan would exercise an active political role. He acted cautiously, with no intention of permitting more radical elements in the nationalist movement to overthrow the established order. He was also intent on preventing the Istiqlal from consolidating its control and establishing a one-party state. In August 1957, Mohammed V assumed the title of king.

Flag of Morocco

Morocco gained independence from France and Spain in 1956 and became the Kingdom of Morocco, a constitutional monarchy led by King Mohammed V.

33.1.4: The Libyan Arab Republic

A military coup in 1969 overthrew King Idris I, beginning a period of sweeping social reform led by Muammar Gaddafi, who was ultimately able to fully concentrate power in his own hands during the Libyan Cultural Revolution, remaining in power until the Libyan Civil War of 2011.

Learning Objective

Explain Libya’s transition to authoritarian rule under Gaddafi

Key Points

- From 1911-1943, Italy colonized and ruled over the territory of modern-day Libya, first as known as Italian North Africa and then as Italian Libya.

- Toward the end of WWII, the allied forces took Libya from Italy and occupied it until 1951, when it became an independent kingdom ruled by King Idris I.

- On September 1, 1969, a small group of military officers led by Muammar Gaddafi staged a coup d’état against King Idris, giving rise to a period of social reform under the authoritarian rule of Gaddafi.

- Gaddafi’s rule was highly controversial, both praised for his anti-imperialism and criticized for his repressive treatment of citizens; his regime was known for executing dissidents publicly, often rebroadcast on state television channels.

- Gaddafi ruled until 2011, when he was deposed during the Libyan Civil War.

Key Terms

- 2011 Libyan Civil War

-

An armed conflict in 2011 in the North African country of Libya, fought between forces loyal to Colonel Muammar Gaddafi and those seeking to oust his government.

- Muammar Gaddafi

-

A Libyan revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He governed Libya as Revolutionary Chairman of the Libyan Arab Republic from 1969 to 1977 and then as the “Brotherly Leader” of the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya from 1977 to 2011. A controversial and highly divisive world figure, he was decorated with various awards and lauded for both his anti-imperialist stance and his support for Pan-Africanism and Pan-Arabism. Conversely, he was internationally condemned as a dictator and autocrat whose authoritarian administration violated the human rights of Libyan citizens and supported irredentist movements, tribal warfare, and terrorism in many other nations.

- Nasserism

-

A socialist Arab nationalist political ideology based on the thinking of Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s second president and one of the two principal leaders of the Egyptian Revolution of 1952. Spanning the domestic and international spheres, it combines elements of Arab socialism, republicanism, nationalism, anti-imperialism, developing-world solidarity, and international non-alignment.

- Bedouin

-

A recent term in the Arabic language that is used commonly to refer to the people (Arabs and non-Arabs) who live or have descended from tribes who lived stationary or nomadic lifestyles outside cities and towns.

Italian Libya

The Italo-Turkish War was fought between the Ottoman Empire (Turkey) and the Kingdom of Italy from September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. As a result of this conflict, Italy captured the Ottoman Tripolitania Vilayet province and turned it into a colony. From 1912 to 1927, the territory of Libya was known as Italian North Africa. From 1927 to 1934, the territory was split into two colonies, Italian Cyrenaica and Italian Tripolitania, run by Italian governors. Some 150,000 Italians settled in Libya, constituting roughly 20% of the total population.

In 1934, Italy adopted the name “Libya” (used by the Ancient Greeks for all of North Africa, except Egypt) as the official name of the colony (made up of the three provinces of Cyrenaica, Tripolitania, and Fezzan). Omar Mukhtar was the resistance leader against the Italian colonization and became a national hero despite his capture and execution on September 16, 1931. His face is currently printed on the Libyan ten dinar note in recognition of his patriotism. Idris al-Mahdi as-Senussi (later King Idris I), Emir of Cyrenaica, led the Libyan resistance to Italian occupation between the two world wars. Ilan Pappé estimates that between 1928 and 1932, the Italian military “killed half the Bedouin population (directly or through disease and starvation in camps).” Italian historian Emilio Gentile estimates 50,000 deaths resulting from the suppression of resistance.

In June 1940, Italy entered World War II. Libya became the setting for the hard-fought North African Campaign that ultimately ended in defeat for Italy and its German ally in 1943.

From 1943 to 1951, Libya was under Allied occupation. The British military administered the two former Italian Libyan provinces of Tripolitana and Cyrenaïca, while the French administered the province of Fezzan. In 1944, Idris returned from exile in Cairo but declined to resume permanent residence in Cyrenaica until the removal of some aspects of foreign control in 1947. Under the terms of the 1947 peace treaty with the Allies, Italy relinquished all claims to Libya.

Kingdom of Libya

On November 21, 1949, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution stating that Libya should become independent before January 1, 1952. Idris represented Libya in the subsequent UN negotiations. On December 24, 1951, Libya declared its independence as the United Kingdom of Libya, a constitutional and hereditary monarchy under King Idris, Libya’s only monarch.

The discovery of significant oil reserves in 1959 and the subsequent income from petroleum sales enabled one of the world’s poorest nations to establish an extremely wealthy state. Although oil drastically improved the Libyan government’s finances, resentment among some factions began to build over the increased concentration of the nation’s wealth in the hands of King Idris. This discontent mounted with the rise of Nasserism and Arab nationalism throughout North Africa and the Middle East, so while the continued presence of Americans, Italians, and British in Libya aided in the increased levels of wealth and tourism following WWII, it was seen by some as a threat.

Libyan Revolution: Gaddafi

On September 1, 1969, a small group of military officers led by 27-year-old army officer Muammar Gaddafi staged a coup d’état against King Idris, launching the Libyan Revolution. Gaddafi was referred to as the “Brother Leader and Guide of the Revolution” in government statements and the official Libyan press.

On the birthday of Muhammad in 1973, Gaddafi delivered a “Five-Point Address.” He announced the suspension of all existing laws and the implementation of Sharia. He said that the country would be purged of the “politically sick.” A “people’s militia” would “protect the revolution.” There would be an administrative revolution and a cultural revolution. Gaddafi set up an extensive surveillance system: 10 to 20 percent of Libyans worked in surveillance for the Revolutionary committees, which monitored place in government, factories, and the education sector. Gaddafi executed dissidents publicly and the executions were often rebroadcast on state television channels. He employed his network of diplomats and recruits to assassinate dozens of critical refugees around the world.

In 1977, Libya officially became the “Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya.” Gaddafi officially passed power to the General People’s Committees and henceforth claimed to be no more than a symbolic figurehead, but domestic and international critics claimed the reforms gave him virtually unlimited power. Dissidents against the new system were not tolerated, with punitive actions including capital punishment authorized by Gaddafi himself. The new “jamahiriya” governance structure he established was officially referred to as a form of direct democracy, though the government refused to publish election results. Gaddafi was ruler of Libya until the 2011 Libyan Civil War, when he was deposed with the backing of NATO. Since then, Libya has experienced instability.

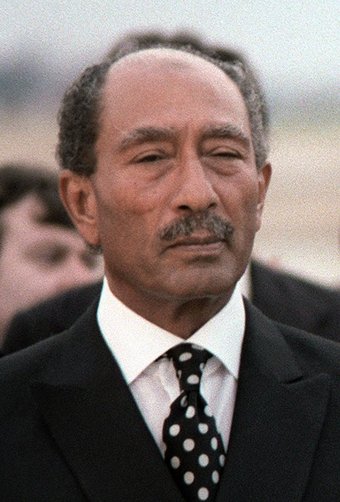

Libyan Revolution of 1969

Muammar Gaddafi at an Arab summit in Libya in 1969, shortly after the September Revolution that toppled King Idris I. Gaddafi sits in military uniform in the middle, surrounded by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser (left) and Syrian President Nureddin al-Atassi (right).

33.2: The Democratic Republic of the Congo

33.2.1: Independence from Belgium

In May 1960, a growing nationalist movement, the Mouvement National Congolais led by Patrice Lumumba, won the parliamentary elections. On June 30, 1960, the Congo gained independence from Belgium.

Learning Objective

Contrast Congo’s transition to independence with those of other African states

Key Points

- Colonial rule in the Congo began in the late 19th century under King Leopold II, who annexed the territory as his personal possession, naming it the “Congo Free State” and violently exploiting the native population for the extraction and production of rubber and other natural resources.

- By the turn of the century, however, the violence of Free State officials against indigenous Congolese and the ruthless system of economic extraction led to intense diplomatic pressure on Belgium to take official control of the country, which it did in 1908, creating the Belgian Congo.

- An African nationalist movement developed in the Belgian Congo during the 1950s, primarily among the educated class.

- One of the major forces in the nationalist movement was the Mouvement National Congolais or MNC Party led by Patrice Lumumba, who pressured Belgium to relinquish the Congo as colonial territory.

- The proclamation of the independent Republic of the Congo, and the end of colonial rule, occurred as planned on June 30, 1960 when Lumumba gave an unplanned and controversial speech attacking colonialism.

Key Terms

- évolués

-

A French term used during the colonial era to refer to a native African or Asian who had “evolved” by becoming Europeanised through education or assimilation and accepted European values and patterns of behavior.

- Mouvement National Congolais (MNC)

-

A political party in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, founded in 1958 as a nationalist, pro-independence, united front organization dedicated to achieving independence “within a reasonable” time and bringing together members from various political backgrounds to achieve independence.

- King Leopold II

-

The second King of the Belgians, known for the founding and exploitation of the Congo Free State as a private venture.

Belgian Rule

Colonial rule in the Congo began in the late 19th century. King Leopold II of Belgium, frustrated by Belgium’s lack of international power and prestige, attempted to persuade his government to support colonial expansion around the then-largely unexplored Congo Basin. The Belgian government’s ambivalence eventually led Leopold to create the colony on his own account. With support from a number of Western countries who viewed Leopold as a useful buffer between rival colonial powers, Leopold achieved international recognition for a personal colony, the Congo Free State, in 1885.

By the turn of the century, however, the violence of Free State officials against indigenous Congolese and the ruthless system of economic extraction led to intense diplomatic pressure on Belgium to take official control of the country, which it did in 1908, creating the Belgian Congo.

During the 1940s and 1950s, the Congo experienced an unprecedented level of urbanization and the colonial administration began development programs aimed at making the territory into a “model colony.” One of the results of these measures was the development of a new middle class of Europeanised African “évolués” in the cities. By the 1950s the Congo had a wage labor force twice as large as that of any other African colony. The Congo’s rich natural resources, including uranium—much of the uranium used by the U.S. nuclear program during World War II was Congolese—led to substantial interest in the region from both the Soviet Union and the United States as the Cold War developed.

Force Publique

Force Publique soldiers in the Belgian Congo in 1918. At its peak, the Force Publique had around 19,000 African soldiers, led by 420 white officers.

Nationalist Politics

An African nationalist movement developed in the Belgian Congo during the 1950s, primarily among the évolués. The movement consisted of a number of parties and groups which were broadly divided on ethnic and geographical lines and opposed to one another. The largest, the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC), was a united front organisation dedicated to achieving independence “within a reasonable” time. It was created around a charter which was signed by, among others, Patrice Lumumba, Cyrille Adoula and Joseph Iléo, but was often accused of being too moderate. Lumumba became a leading figure within the MNC, and by the end of 1959, the party claimed 58,000 members.

Although it was the largest of the African nationalist parties, the MNC had many different factions that took differing stances on many issues. It was increasingly polarized between moderate évolués and the more radical mass membership. A radical faction headed by Iléo and Albert Kalonji split away in July 1959, but failed to induce mass defections by other MNC members.

Major riots broke out in Léopoldville, the Congolese capital, on January 4, 1959, after a political demonstration turned violent. The colonial army, the Force Publique, used force against the rioters—at least 49 people were killed, and total casualties may have been as high as 500. The nationalist parties’ influence expanded outside the major cities for the first time, and nationalist demonstrations and riots became a regular occurrence over the next year, bringing large numbers of black people from outside the évolué class into the independence movement. Many blacks began to test the boundaries of the colonial system by refusing to pay taxes or abide by minor colonial regulations.

Independence from Belgium

In the fallout from the Léopoldville riots, the report of a Belgian parliamentary working group on the future of the Congo was published in which a strong demand for “internal autonomy” was noted. August de Schryver, the Minister of the Colonies, launched a high-profile Round Table Conference in Brussels in January 1960 with the leaders of all the major Congolese parties in attendance. Lumumba, who had been arrested following riots in Stanleyville, was released in the run-up to the conference and headed the MNC delegation. The Belgian government had hoped for at least 30 years before independence, but Congolese pressure at the conference led to a target date of June 30, 1960. Issues including federalism, ethnicity, and the future role of Belgium in Congolese affairs were left unresolved after the delegates failed to reach agreement.

Belgians began campaigning against Lumumba, whom they wanted to marginalize; they accused him of being a communist and hoping to fragment the nationalist movement, supported rival, ethnic-based parties like CONAKAT. Many Belgians hoped that an independent Congo would form part of a federation, like the French Community or British Commonwealth of Nations, and that close economic and political association with Belgium would continue. As independence approached, the Belgian government organised Congolese elections in May 1960. These resulted in a broad MNC majority.

The proclamation of the independent Republic of the Congo and the end of colonial rule occurred as planned on June 30, 1960. In a ceremony at the Palais de la Nation in Léopoldville, King Baudouin gave a speech in which he presented the end of colonial rule in the Congo as the culmination of the Belgian “civilising mission” begun by Leopold II. After the King’s address, Lumumba gave an unscheduled speech in which he angrily attacked colonialism and described independence as the crowning success of the nationalist movement. Although Lumumba’s address was acclaimed by figures such as Malcolm X, it nearly provoked a diplomatic incident with Belgium; even some Congolese politicians perceived it as unnecessarily provocative. Nevertheless, independence was celebrated across the Congo.

Independence from Belgium

Patrice Lumumba, leader of the MNC and first Prime Minister, pictured in Brussels at the Round Table Conference of 1960.

33.2.2: Lumumba and the Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis was a period of political upheaval and conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo between 1960 and 1965, initially caused by a mutiny by the white leadership in the Congolese army and resulting in the execution of Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba.

Learning Objective

Describe the political atmosphere surrounding Lumumba’s time in office

Key Points

- Shortly after Congolese independence in 1960, a mutiny broke out in the army led by the white military leadership, marking the beginning of the Congo Crisis.

- Lumumba appealed to the United States and the United Nations for assistance in suppressing the Belgian-supported Katangan secessionists.

- Both parties refused, so Lumumba turned to the Soviet Union for support.

- This led to growing differences with President Joseph Kasa-Vubu and chief-of-staff Joseph-Désiré Mobutu as well as foreign opposition from the U.S. and Belgium.

- Lumumba was subsequently imprisoned by state authorities under Mobutu and executed by a firing squad under the command of Katangan authorities.

- The United Nations, which he had asked to come to the Congo, did not intervene to save him.

Key Terms

- Émile Janssens

-

A Belgian military officer and colonial official, best known for his command of the Force Publique at the start of the Congo Crisis.

- Patrice Lumumba

-

Congolese independence leader and the first democratically elected leader of the Congo as prime minister. As founder and leader of the mainstream Mouvement National Congolais (MNC) party, he played an important role in campaigning for independence from Belgium.

- Force Publique

-

A gendarmerie and military force in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1885 (when the territory was known as the Congo Free State), through the period of direct Belgian colonial rule and for a short time after independence.

The Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis was a period of political upheaval and conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo between 1960 and 1965. It began almost immediately after the Congo became independent from Belgium and ended unofficially with the entire country under the rule of Joseph-Désiré Mobutu. Constituting a series of civil wars, the Congo Crisis was also a proxy conflict in the Cold War in which the Soviet Union and United States supported opposing factions. Around 100,000 people were killed during the crisis.

A nationalist movement in the Belgian Congo demanding the end of colonial rule led to the country’s independence on June 30, 1960. Minimal preparations had been made and many issues, such as the questions of federalism and ethnicity, remained unresolved. In the first week of July, a mutiny broke out in the army and violence erupted between black and white civilians. Belgium sent troops to protect fleeing whites and two areas of the country, Katanga and South Kasai, seceded with Belgian support. Amid continuing unrest and violence, the United Nations deployed peacekeepers, but the UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld refused to use these troops to help the central government in Léopoldville fight the secessionists. Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, the charismatic leader of the largest nationalist faction, reacted by calling for assistance from the Soviet Union, which promptly sent military advisors and other support.

The involvement of the Soviets split the Congolese government and led to an impasse between Lumumba and President Joseph Kasa-Vubu. Mobutu, in command of the army, broke this deadlock with a coup d’état, expelled the Soviet advisors, and established a new government effectively under his control. Lumumba was placed in captivity and subsequently executed in 1961. A rival government, founded by Antoine Gizenga and Lumumba supporters in the eastern city of Stanleyville, gained Soviet support but was crushed in 1962. Meanwhile, the UN took a more aggressive stance towards the secessionists after Hammarskjöld was killed in a plane crash in late 1961. Supported by UN troops, Léopoldville defeated the secessionist movements in Katanga and South Kasai by early 1963.

With Katanga and South Kasai back under the government’s control, a reconciliatory compromise constitution was adopted and the exiled Katangese leader, Moise Tshombe, was recalled to head an interim administration while fresh elections were organized. Before these could be held, however, Maoist-inspired militants calling themselves the “Simbas” rose up in the east of the country. The Simbas took control of a significant amount of territory and proclaimed a communist “People’s Republic of the Congo” in Stanleyville. Government forces gradually retook territory and in November 1964, Belgium and the United States intervened in Stanleyville to recover hostages from Simba captivity. The Simbas were defeated and collapsed soon after. Following the elections in March 1965, a new political stalemate developed between Tshombe and Kasa-Vubu, forcing the government into near-paralysis. Mobutu mounted a second coup d’état in November 1965, now taking personal control. Under Mobutu’s rule, the Congo (renamed Zaire in 1971) was transformed into a dictatorship which would endure until his deposition in 1997.

The Death of Lumumba

Pro-Lumumba demonstrators in Maribor, Yugoslavia in February 1961.

Force Publique Mutiny

Despite the proclamation of independence, neither the Belgian nor the Congolese government intended the colonial social order to end immediately. The Belgian government hoped that whites might keep their position indefinitely. The Republic of the Congo was still reliant on colonial institutions like the Force Publique to function from day to day, and white technical experts installed by the Belgians were retained in the broad absence of suitably qualified black Congolese replacements (partly the result of colonial restrictions regarding higher education). Many Congolese assumed that independence would produce tangible and immediate social change, so the retention of whites in positions of importance was widely resented.

Lieutenant-General Émile Janssens, the Belgian commander of the Force Publique, refused to see Congolese independence as a change in the nature of command. The day after the independence festivities, he gathered the black non-commissioned officers of his Léopoldville garrison and told them that things under his command would stay the same, summarizing the point by writing “Before Independence = After Independence” on a blackboard. This message was hugely unpopular among the rank and file—many of the men had expected rapid promotions and increases in pay to accompany independence. On July 5, several units mutinied against their white officers at Camp Hardy near Thysville. The insurrection spread to Léopoldville the next day and later to garrisons across the country.

Rather than deploying Belgian troops against the mutineers as Janssens wished, Lumumba dismissed him and renamed the Force Publique the Armée Nationale Congolaise (ANC). All black soldiers were promoted by at least one rank. Victor Lundula was promoted directly from sergeant-major to major-general and head of the army, replacing Janssens. At the same time, Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, an ex-sergeant-major and close personal aide of Lumumba, became Lundula’s deputy as army chief of staff. The government attempted to stop the revolt—Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu intervened personally at Léopoldville and Thysville and persuaded the mutineers to lay down their arms—but in most of the country the mutiny intensified. White officers and civilians were attacked, white-owned properties were looted, and white women were raped. The Belgian government became deeply concerned by the situation, particularly when white civilians began entering neighboring countries as refugees.

Lumumba’s stance appeared to many Belgians to justify their prior concerns about his radicalism. On July 9, Belgium deployed paratroopers, without the Congolese state’s permission, in Kabalo and elsewhere to protect fleeing white civilians. The Belgian intervention divided Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu; while Kasa-Vubu accepted the Belgian operation, Lumumba denounced it and called for “all Congolese to defend our republic against those who menace it.” At Lumumba’s request, white civilians from the port city of Matadi were evacuated by the Belgian Navy on July 11. Belgian ships then bombarded the city; at least 19 civilians were killed. This action prompted renewed attacks on whites across the country, while Belgian forces entered other towns and cities, including Léopoldville, and clashed with Congolese troops.

33.2.3: Mobutu and Zaire

During the Congo Crisis, military leader Joseph-Desiré Mobutu ousted the nationalist government of Patrice Lumumba and eventually took authoritarian control of the Congo, renaming it Zaire in 1971, and attempted to purge the country of all colonial cultural influence.

Learning Objective

Discuss how Mobutu was able to seize power in the Congo

Key Points

- Mobutu Sese Seko was the military dictator and President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1965 to 1997, which he renamed the Republic of Zaire in 1971.

- Patrice Lumumba previously appointed Joseph Mobutu chief of staff of the new Congo army and by taking advantage of the leadership crisis between Kasavubu and Lumumba, Mobutu garnered enough support within the army to create mutiny, eventually allowing him to stage a bloodless coup and take control of the Congo’s government.

- A one-party system was established, and Mobutu declared himself head of state.

- Although relative peace and stability were achieved, Mobutu’s government was guilty of severe human rights violations, political repression, a cult of personality, and corruption.

- Mobutu had the support of the United States because of his staunch opposition to Communism; they believed his administration would serve as an effective counter to communist movements in Africa.

- Embarking on a campaign of pro-Africa cultural awareness, or authenticité, Mobutu began renaming the cities of the Congo starting on June 1, 1966, as well as mandating that Zairians were to abandon their Christian names for more “authentic” ones and adopt traditional attire such as the abacost.

Key Terms

- Joseph-Désiré Mobutu

-

The military dictator and President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (which was renamed Zaire in 1971) from 1965 to 1997, who formed an authoritarian regime, amassed vast personal wealth, and attempted to purge the country of all colonial cultural influence while enjoying considerable support from the United States due to its anti-communist stance.

- Authenticité

-

An official state ideology of the Mobutu regime that originated in the late 1960s and early 1970s, aimed at ridding the country of the lingering vestiges of colonialism and the continuing influence of Western culture and create a more centralized and singular national identity.

Rise to Power

Following Congo’s independence on June 30, 1960, a coalition government was formed, led by Prime Minister Lumumba and President Joseph Kasa-Vubu. The new nation quickly lurched into the Congo Crisis as the army mutinied against the remaining Belgian officers. Lumumba appointed Joseph-Désiré Mobutu as Chief of Staff of the Armée Nationale Congolaise, the Congolese National Army, under army chief Victor Lundula.

Encouraged by a Belgian government intent on maintaining its access to rich Congolese mines, secessionist violence erupted in the south. Concerned that the United Nations force sent to help restore order was not helping to crush the secessionists, Lumumba turned to the Soviet Union for assistance, receiving massive military aid and about a thousand Soviet technical advisers in six weeks. Kasa-Vubu was encouraged by the U.S. and Belgium to stage a coup and thus dismissed Lumumba. An outraged Lumumba declared Kasa-Vubu deposed. Both Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu ordered Mobutu to arrest the other. As Army Chief of Staff, Mobutu came under great pressure from multiple sources. The embassies of Western nations, which helped pay the soldiers’ salaries, as well as Kasa-Vubu and Mobutu’s subordinates, all favored getting rid of the Soviet presence.

Mobutu accused Lumumba of pro-communist sympathies, thereby hoping to gain the support of the United States, but Lumumba fled to Stanleyville where he set up his own government. The USSR again supplied him with weapons and he was able to defend his position. In November 1960, he was captured and sent to Katanga. Mobutu still considered him a threat and on January 17, 1961, ordered him arrested and publicly beaten. Lumumba then disappeared from the public view. It was later discovered that he was murdered the same day by the secessionist forces of Moise Tshombe after Mobutu’s government turned him over to them at the urging of Belgium. On January 23, 1961, Kasa-Vubu promoted Mobutu to major-general.

Mobutu’s Coup

Prime Minister Moise Tshombe’s Congolese National Convention won a large majority in the March 1965 elections, but Kasa-Vubu appointed an anti-Tshombe leader, Évariste Kimba, as prime minister-designate. However, Parliament twice refused to confirm him. With the government in near-paralysis, Mobutu seized power in a bloodless coup on November 25, a month after his 35th birthday.

Under the auspices of a regime d’exception (the equivalent of a state of emergency), Mobutu assumed sweeping—almost absolute—powers for five years. In his first speech upon taking power, Mobutu told a large crowd at Léopoldville’s main stadium that since politicians had brought the country to ruin in five years, “for five years, there will be no more political party activity in the country.” Parliament was reduced to a rubber-stamp before being abolished altogether, though it was later revived. The number of provinces was reduced and their autonomy curtailed, resulting in a highly centralized state.

A constitutional referendum after Mobutu’s coup of 1965 resulted in the country’s official name being changed to the “Democratic Republic of the Congo.” In 1971 Mobutu changed the name again, this time to “Republic of Zaire.”

Zaire and the Authenticité Movement

Facing many challenges early in his rule, Mobutu was able to turn most opposition into submission through patronage; those he could not co-opt, he dealt with forcefully. In 1966 four cabinet members were arrested on charges of complicity in an attempted coup, tried by a military tribunal, and publicly executed in an open-air spectacle witnessed by over 50,000 people. Uprisings by former Katangan gendarmeries were crushed, as was an aborted revolt led by white mercenaries in 1967. By 1970, nearly all potential threats to his authority had been smashed, and for the most part, law and order was brought to most of the country. That year marked the pinnacle of Mobutu’s legitimacy and power.

The new president had the support of the United States because of his staunch opposition to Communism; the U.S. believed his administration would be an effective counter to communist movements in Africa. A one-party system was established and Mobutu declared himself head of state. He periodically held elections in which he was the only candidate. Although relative peace and stability were achieved, Mobutu’s government was guilty of severe human rights violations, political repression, a cult of personality, and corruption.

Corruption became so prevalent the term “le mal Zairois” or “Zairean Sickness,” meaning gross corruption, theft, and mismanagement, was coined, reportedly by Mobutu himself. International aid, most often in the form of loans, enriched Mobutu while he allowed national infrastructure such as roads to deteriorate to as little as one-quarter of what had existed in 1960. Zaire became a “kleptocracy” as Mobutu and his associates embezzled government funds.

Authenticité, sometimes Zairianisation in English, was an official state ideology of the Mobutu regime that originated in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The authenticity campaign was an effort to rid the country of the lingering vestiges of colonialism and the continuing influence of Western culture and create a more centralized and singular national identity. The policy, as implemented, included numerous changes to the state and to private life, including the renaming of the Congo (to Zaire) and its cities (Leopoldville became Kinshasa, Elisabethville became Lubumbashi, and Stanleyville became Kisangani), as well as an eventual mandate that Zairians were to abandon their Christian names for more “authentic” ones. In addition, Western-style attire was banned and replaced with the Mao-style tunic labeled the “abacost” and its female equivalent. In 1972, Mobutu renamed himself Mobutu Sese Seko Nkuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga (“The all-powerful warrior who, because of his endurance and inflexible will to win, goes from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake”), Mobutu Sese Seko for short. Mobutu ruled until 1997, when rebel forces led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila expelled him from the country. Already suffering from advanced prostate cancer, he died three months later in Morocco.

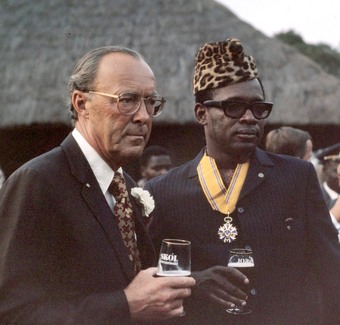

Prince Bernhard and Mobutu Sese Seko

Mobutu Sese Seko with the Dutch Prince Bernhard in 1973. It was also around this time that he assumed his classic image—abacost, thick-framed glasses, walking stick and leopard-skin toque.

33.2.4: Cold War Politics in Zaire

For the most part, Zaire enjoyed warm relations with the United States because of its anti-communist stance, receiving substantial financial aid throughout the Cold War.

Learning Objective

Evaluate the role the United States played in propogating Mobutu’s regime

Key Points

- During the Cold War, the United States and Soviet Union started placing immense pressure on post-colonial developing nations to align with one of the superpower factions.

- The Congo Crisis was a proxy conflict in the Cold War in which the Soviet Union and United States supported opposing factions.

- The CIA backed military chief of staff Mobutu to oust Prime Minister Lumumba, eventually leading to Mobutu forming an authoritarian regime in the Congo, which he renamed Zaire in 1971.

- The United States was the third largest donor of aid to Zaire (after Belgium and France), and Mobutu befriended several US presidents, including Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush.

- Because of Mobutu’s poor human rights record, the Carter administration put some distance between itself and Zaire; even so, Zaire received nearly half the foreign aid Carter allocated to sub-Saharan Africa.

- Mobutu’s relationship with the U.S. radically changed shortly afterward with the end of the Cold War, and the U.S. began pressuring Mobutu to democratize his regime.

- Mobutu’s relationship with the Soviet Union was generally negative, although he did allow some relations to maintain a non-aligned image.

Key Terms

- proxy conflict

-

A conflict between two states or non-state actors where neither entity directly engages the other. While this can encompass a breadth of armed confrontation, its core definition hinges on two separate powers utilizing external strife to somehow attack the interests or territorial holdings of the other.

- non-aligned

-

A group of states that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc, especially during the Cold War.

Decolonization in the Cold War

The combined effects of two great European wars weakened the political and economic domination of Latin America, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East by European powers. This led to a series of waves of African and Asian decolonization following the Second World War; a world that had been dominated for over a century by Western imperialist colonial powers was transformed into a world of emerging African, Middle Eastern, and Asian nations. The Cold War started placing immense pressure on developing nations to align with one of the superpower factions. Both promised substantial financial, military, and diplomatic aid in exchange for an alliance in which issues like corruption and human rights abuses were overlooked or ignored. When an allied government was threatened, the superpowers were often prepared to intervene.

The Congo Crisis can be seen in this context as a proxy conflict in the Cold War with the Soviet Union and United States supporting opposing factions, Patrice Lumumba and Mobutu, respectively. The CIA backed Mobutu’s initial coup against Lumumba and the Soviet Union provided Lumumba weapons and support while in exile. When Lumumba was killed and Mobutu took total control of the Congo’s government, he enjoyed considerable support from the United States due to his anti-communist stance.

Relations with the United States

For the most part, Zaire enjoyed warm relations with the United States. The U.S. was the third largest donor of aid to Zaire (after Belgium and France), and Mobutu befriended several U.S. presidents, including Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush. Relations did cool significantly in 1974–1975 over Mobutu’s increasingly radical rhetoric (which included his scathing denunciations of American foreign policy) and plummeted to an all-time low in the summer of 1975, when Mobutu accused the Central Intelligence Agency of plotting his overthrow, arrested eleven senior Zairian generals and several civilians, and condemned a former head of the Central Bank (Albert N’dele). However, many people viewed these charges with skepticism; in fact, one of Mobutu’s staunchest critics, Nzongola-Ntalaja, speculated that Mobutu invented the plot as an excuse to purge the military of talented officers who might otherwise pose a threat to his rule. In spite of these hindrances, the chilly relationship quickly thawed when both countries found each other supporting the same side during the Angolan Civil War.

Because of Mobutu’s poor human rights record, the Carter administration put some distance between itself and the Kinshasa government; even so, Zaire received nearly half the foreign aid Carter allocated to sub-Saharan Africa. During the first Shaba invasion, the United States played a relatively inconsequential role; its belated intervention consisted of little more than the delivery of non-lethal supplies. But during the second Shaba invasion, the U.S. provided transportation and logistical support to the French and Belgian paratroopers that were deployed to aid Mobutu against the rebels. Carter echoed Mobutu’s (unsubstantiated) charges of Soviet and Cuban aid to the rebels, until it was apparent that no hard evidence existed to verify his claims. In 1980, the U.S. House of Representatives voted to terminate military aid to Zaire, but the Senate reinstated the funds in response to pressure from Carter and American business interests in Zaire.

Mobutu enjoyed a very warm relationship with the Reagan Administration through financial donations. During Reagan’s presidency, Mobutu visited the White House three times, and criticism of Zaire’s human rights record by the U.S. was effectively muted. During a state visit by Mobutu in 1983, Reagan praised the Zairian strongman as “a voice of good sense and goodwill.”

Mobutu also had a cordial relationship with Reagan’s successor, George H. W. Bush; he was the first African head of state to visit Bush at the White House. Even so, Mobutu’s relationship with the U.S. radically changed shortly afterward with the end of the Cold War. With the Soviet Union gone, there was no longer any reason to support Mobutu as a bulwark against communism. Accordingly, the U.S. and other Western powers began pressuring Mobutu to democratize the regime. Regarding the change in U.S. attitude to his regime, Mobutu bitterly remarked: “I am the latest victim of the cold war, no longer needed by the US. The lesson is that my support for American policy counts for nothing.” In 1993, Mobutu was denied a visa by the U.S. State Department after he sought to visit Washington, DC.

Mobutu and Nixon

Mobutu Sese Seko and Richard Nixon in Washington, D.C., October 1973. Mobutu enjoyed warm relations with the United States during the Cold War, receiving substantial financial aid despite criticism of his human rights abuses.

Relations with the Soviet Union

Mobutu’s relationship with the Soviet Union was frosty and tense. Mobutu, a staunch anticommunist, was not anxious to recognize the Soviets; he remembered well their support, albeit mostly vocal, of Lumumba and the Simba rebels before he took power. However, to project a non-aligned image, he did renew ties in 1967; the first Soviet ambassador arrived and presented his credentials in 1968. Mobutu did, however, join the U.S. in condemning the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia that same year. Mobutu viewed the Soviet presence as advantageous for two reasons: it allowed him to maintain an image of non-alignment, and it provided a convenient scapegoat for problems at home. For example, in 1970, he expelled four Soviet diplomats for carrying out “subversive activities,” and in 1971, 20 Soviet officials were declared persona non grata for allegedly instigating student demonstrations at Lovanium University.

Relations cooled further in 1975, when the two countries found themselves opposing different sides in the Angolan Civil War. This had a dramatic effect on Zairian foreign policy for the next decade; bereft of his claim to African leadership (Mobutu was one of the few leaders who denied the Marxist government of Angola recognition), Mobutu turned increasingly to the U.S. and its allies, adopting pro-American stances on such issues as the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Israel’s position in international organizations.

Mobutu condemned the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, and in 1980, his was the first African nation to join the United States in boycotting the Summer Olympics in Moscow. Throughout the 1980s, he remained consistently anti-Soviet, and found himself opposing pro-Soviet countries such as Libya and Angola; in the mid-1980s, he described Zaire as being surrounded by a “red belt” of radical states allied to the Soviet Union and Libya.

The collapse of the Soviet Union had disastrous repercussions for Mobutu. His anti-Soviet stance was the main catalyst for Western aid; without it, there was no longer any reason to support him. Western countries began calling for him to introduce democracy and improve human rights.

33.3: Zimbabwe

33.3.1: The Unilateral Declaration of Independence

In 1965, the conservative white minority government in Rhodesia unilaterally declared independence from the United Kingdom, but did not achieve internationally recognized sovereignty until 1980 as Zimbabwe.

Learning Objective

Describe the events that followed the Unilateral Declaration of Independence

Key Points

- The British South Africa Company of Cecil Rhodes first demarcated the present territory during the 1890s; it became the self-governing British colony of Southern Rhodesia in 1923.

- In 1965, the conservative white minority government unilaterally declared independence as Rhodesia.

- After the cabinet released the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI), the British government petitioned the United Nations for sanctions against Rhodesia and in December 1966, the UN complied, imposing the first mandatory trade embargo on an autonomous state.

- The United Kingdom deemed the Rhodesian declaration an act of rebellion, but did not re-establish control by force.

- The state endured international isolation and a 15-year guerrilla war with black nationalist forces; this culminated in a peace agreement that established universal enfranchisement and de jure sovereignty in April 1980 as Zimbabwe.

Key Terms

- Wind of Change

-

A historically significant address made by British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan to the Parliament of South Africa on February 3, 1960, in Cape Town. He spent a month in Africa visiting a number of what were then British colonies. The speech signaled clearly that the Conservative-led British Government intended to grant independence to many of these territories, which happened subsequently in the 1960s.

- Rhodesia

-

An unrecognised state in southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territorial terms to modern Zimbabwe.

Background

The Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) was a statement adopted by the Cabinet of Rhodesia on 11 November 1965, announcing that Rhodesia, a British territory in southern Africa that had governed itself since 1923, now regarded itself as an independent sovereign state. The culmination of a protracted dispute between the British and Rhodesian governments regarding the terms under which the latter could become fully independent, it was the first unilateral break from the United Kingdom by one of its colonies since the United States Declaration of Independence nearly two centuries before. Britain, the Commonwealth, and the United Nations all deemed Rhodesia’s UDI illegal, and economic sanctions, the first in the UN’s history, were imposed on the breakaway colony. Amid near-complete international isolation, Rhodesia continued as an unrecognized state with the assistance of South Africa and Portugal.

The Rhodesian government, comprised mostly of members of the country’s white minority of about 5%, was indignant when amid decolonization and the Wind of Change, less developed African colonies to the north without comparable experience of self-rule quickly advanced to independence during the early 1960s while Rhodesia was refused sovereignty under the newly ascendant principle of “no independence before majority rule.” Most white Rhodesians felt that they were due independence following four decades’ self-government and that Britain was betraying them by withholding it. This combined with the colonial government’s acute reluctance to hand over power to black nationalists—the manifestation of racial tensions, Cold War anti-communism, and the fear that a dystopian Congo-style situation might result—to create the impression that if Britain did not grant independence, Rhodesia might be justified in taking it unilaterally.

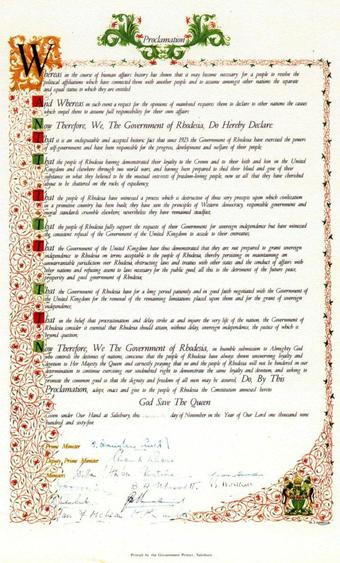

Unilateral Declaration of Independence

A photograph of the proclamation document announcing the Rhodesian government’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence (“UDI”) from the United Kingdom, created during early November 1965 and signed on 11 November 1965.

The Road to Recognition

A stalemate developed between the British and Rhodesian Prime Ministers, Harold Wilson and Ian Smith respectively, between 1964 and 1965. Dispute largely surrounded the British condition that the terms for independence had to be acceptable “to the people of the country as a whole.” Smith contended that this was met, while Britain and black nationalist leaders in Rhodesia held that it was not. After Wilson proposed in late October 1965 that Britain might safeguard future black representation in the Rhodesian parliament by withdrawing some of the colonial government’s devolved powers, then presented terms for an investigatory Royal Commission that the Rhodesians found unacceptable, Smith and his Cabinet declared independence. Calling this treasonous, the British colonial Governor Sir Humphrey Gibbs formally dismissed Smith and his government, but they ignored him and appointed an “Officer Administering the Government” to take his place.

While no country recognized the UDI, the Rhodesian High Court deemed the post-UDI government legal and de jure in 1968. The Smith administration initially professed continued loyalty to Queen Elizabeth II, but abandoned this in 1970 when it declared a republic in an unsuccessful attempt to win foreign recognition. The Rhodesian Bush War, a guerrilla conflict between the government and two rival communist-backed black nationalist groups, began in earnest two years later, and after several attempts to end the war Smith agreed the Internal Settlement with non-militant nationalists in 1978. Under these terms, the country was reconstituted under black rule as Zimbabwe Rhodesia in June 1979, but this new order was rejected by the guerrillas and the international community. The Bush War continued until Zimbabwe Rhodesia revoked the UDI as part of the Lancaster House Agreement in December 1979. Following a brief period of direct British rule, the country was granted internationally recognized independence under the name Zimbabwe in 1980.

33.3.2: The Bush War

The Bush War was a civil war that took place from July 1964 to December 1979 in Rhodesia, in which three forces were pitted against one another: the mostly white Rhodesian government and two black nationalist parties.

Learning Objective

Describe the Bush War

Key Points

- In 1965, the conservative white minority government led by Ian Smith unilaterally declared independence from the United Kingdom as Rhodesia, which led to sanctions from the UN.

- The United Kingdom deemed the Rhodesian declaration an act of rebellion, but did not re-establish control by force.