31.1: Axis Powers

31.1.1: Hitler’s Germany

Hitler and his Nazi Party ruled Germany from 1933-1945 as a fascist totalitarian state which controlled nearly all aspects of life.

Learning Objective

Characterize Germany under the Nazi regime

Key Points

- The German economy suffered severe setbacks after the end of World War I, partly because of reparations payments required under the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. These reparations created social unrest and provided an opportunity for the Nazi Party to attract popularity.

- Racism, especially antisemitism, was a central feature of the Nazi Party.

- After the Nazi Party won a majority of seats in the German parliament, Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany by the President of the Weimar Republic Paul von Hindenburg on January, 30 1933, and soon eliminated all political opposition and consolidated his power.

- In March 1933, the Enabling Act, an amendment to the Weimar Constitution, passed in the Reichstag. This allowed Hitler and his cabinet to pass laws—even laws that violated the constitution—without the consent of the president or the Reichstag.

- President Hindenburg died on August 2, 1934, and Hitler became dictator of Germany by merging the powers and offices of the Chancellery and Presidency.

- Germany was now a totalitarian state with Hitler at its head.

Key Terms

- Adolf Hitler

-

A German politician who was the leader of the Nazi Party, Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and Führer of Nazi Germany from 1934 to 1945; he initiated World War II in Europe with the invasion of Poland in September 1939 and was a central figure of the Holocaust.

- antisemitism

-

Hostility, prejudice, or discrimination against Jews.

- Nazi Party

-

A political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that practiced the ideology of Nazism, a form of fascism that incorporates scientific racism and antisemitism.

- fascist

-

A form of radical authoritarian nationalism that came to prominence in early 20th-century Europe, whose proponents believe that liberal democracy is obsolete and regard the complete mobilization of society under a totalitarian one-party state as necessary to prepare a nation for armed conflict and respond effectively to economic difficulties.

Nazi Germany is the common English name for the period in German history from 1933 to 1945 when the country was governed by a dictatorship under the control of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. Under Hitler’s rule, Germany was transformed into a fascist totalitarian state that controlled nearly all aspects of life. The official name of the state was Deutsches Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Großdeutsches Reich (“Greater German Reich”) from 1943 to 1945. The period is also known under the names the Third Reich and the National Socialist Period. The Nazi regime came to an end after the Allied Forces defeated Germany in May 1945, ending World War II in Europe.

Hitler’s Rise to Power

Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany by the President of the Weimar Republic Paul von Hindenburg on January 30, 1933. The Nazi Party then began to eliminate all political opposition and consolidate its power. Hindenburg died on August 2, 1934, and Hitler became dictator of Germany by merging the powers and offices of the Chancellery and Presidency. A national referendum held August 19, 1934 confirmed Hitler as sole Führer (leader) of Germany. All power was centralized in Hitler’s person, and his word became above all laws. The government was not a coordinated, co-operating body, but a collection of factions struggling for power and Hitler’s favor. In the midst of the Great Depression, the Nazis restored economic stability and ended mass unemployment using heavy military spending and a mixed economy. Extensive public works were undertaken, including the construction of Autobahnen (motorways). The return to economic stability boosted the regime’s popularity.

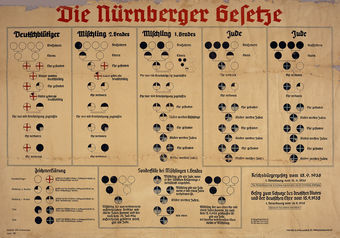

Racism, especially antisemitism, was a central feature of the regime. The Germanic people (the Nordic race) were considered by the Nazis to be the purest branch of the Aryan race, and therefore were viewed as the master race. Millions of Jews and other peoples deemed undesirable by the state were murdered in the Holocaust. Opposition to Hitler’s rule was ruthlessly suppressed. Members of the liberal, socialist, and communist opposition were killed, imprisoned, or exiled. The Christian churches were also oppressed, with many leaders imprisoned. Education focused on racial biology, population policy, and fitness for military service. Career and educational opportunities for women were curtailed. Recreation and tourism were organised via the Strength Through Joy program, and the 1936 Summer Olympics showcased the Third Reich on the international stage. Propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels made effective use of film, mass rallies, and Hitler’s hypnotizing oratory to control public opinion. The government controlled artistic expression, promoting specific art forms and banning or discouraging others.

Beginning in the late 1930s, Nazi Germany made increasingly aggressive territorial demands, threatening war if they were not met. It seized Austria and Czechoslovakia in 1938 and 1939. Hitler made a pact with Joseph Stalin and invaded Poland in September 1939, launching World War II in Europe.

Nazi Flag

National flag of Germany, 1935–45

The Rise of the Nazi Party

The German economy suffered severe setbacks after the end of World War I, partly because of reparations payments required under the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. The government printed money to make the payments and repay the country’s war debt; the resulting hyperinflation led to higher prices for consumer goods, economic chaos, and food riots. When the government failed to make the reparations payments in January 1923, French troops occupied German industrial areas along the Ruhr. Widespread civil unrest followed.

The National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazi Party) was the renamed successor of the German Workers’ Party founded in 1919, one of several far-right political parties active in Germany at the time. The party platform included removal of the Weimar Republic, rejection of the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, radical antisemitism, and anti-Bolshevism. They promised a strong central government, increased Lebensraum (living space) for Germanic peoples, formation of a national community based on race, and racial cleansing via the active suppression of Jews, who would be stripped of their citizenship and civil rights. The Nazis proposed national and cultural renewal based upon the Völkisch (German populist) movement.

When the stock market in the United States crashed on October 24, 1929, the effect on Germany was dire. Millions were thrown out of work, and several major banks collapsed. Hitler and the Nazi Party prepared to take advantage of the emergency to gain support for their party. They promised to strengthen the economy and provide jobs. Many voters decided the Nazi Party was capable of restoring order, quelling civil unrest, and improving Germany’s international reputation. After the federal election of 1932, the Nazis were the largest party in the Reichstag (elected parliament), holding 230 seats with 37.4 percent of the popular vote.

Hitler Seizes Power

Although the Nazis won the greatest share of the popular vote in the two Reichstag general elections of 1932, they did not have a majority, so Hitler led a short-lived coalition government formed by the Nazi Party and the German National People’s Party. Under pressure from politicians, industrialists, and the business community, President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Hitler as Chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933. This event is known as the Machtergreifung (seizure of power). In the following months, the Nazi Party used a process termed Gleichschaltung (co-ordination) to rapidly bring all aspects of life under control of the party. All civilian organizations, including agricultural groups, volunteer organizations, and sports clubs, had their leadership replaced with Nazi sympathizers or party members. By June 1933, virtually the only organisations not under control of the Nazi Party were the army and the churches.

On the night of February 27, 1933, the Reichstag building was set afire; Marinus van der Lubbe, a Dutch communist, was found guilty of starting the blaze. Hitler proclaimed that the arson marked the start of a communist uprising. Violent suppression of communists by the Sturmabteilung (SA) was undertaken all over the country, and 4,000 members of the Communist Party of Germany were arrested. The Reichstag Fire Decree, imposed on February 28, 1933, rescinded most German civil liberties, including rights of assembly and freedom of the press. The decree also allowed the police to detain people indefinitely without charges or a court order. The legislation was accompanied by a propaganda blitz that led to public support for the measure.

In March 1933, the Enabling Act, an amendment to the Weimar Constitution, passed in the Reichstag by a vote of 444 to 94. This amendment allowed Hitler and his cabinet to pass laws—even laws that violated the constitution—without the consent of the president or the Reichstag. As the bill required a two-thirds majority to pass, the Nazis used the provisions of the Reichstag Fire Decree to keep several Social Democratic deputies from attending; the Communists had already been banned. On May 10 the government seized the assets of the Social Democrats; they were banned in June. The remaining political parties were dissolved, and on July 14, 1933, Germany became a de facto one-party state when the founding of new parties was made illegal. Further elections in November 1933, 1936, and 1938 were entirely Nazi-controlled and saw only the Nazis and a small number of independents elected. The regional state parliaments and the Reichsrat (federal upper house) were abolished in January 1934.

On 2 August 1934, President von Hindenburg died. The previous day, the cabinet had enacted the “Law Concerning the Highest State Office of the Reich,” which stated that upon Hindenburg’s death, the office of president would be abolished and its powers merged with those of the chancellor. Hitler thus became head of state as well as head of government. He was formally named as Führer und Reichskanzler (leader and chancellor). Germany was now a totalitarian state with Hitler at its head. As head of state, Hitler became Supreme Commander of the armed forces. The new law altered the traditional loyalty oath of servicemen so that they affirmed loyalty to Hitler personally rather than the office of supreme commander or the state. On August 19, the merger of the presidency with the chancellorship was approved by 90 percent of the electorate in a plebiscite.

Adolf Hitler

Hitler became Germany’s head of state, with the title of Führer und Reichskanzler, in 1934.

31.1.2: Italy Under Mussolini

Italian Fascism under Benito Mussolini was rooted in Italian nationalism and the desire to restore and expand Italian territories.

Learning Objective

Describe Mussolini’s Italy

Key Points

- Social unrest after World War I, led mainly by communists, led to counter-revolution and repression throughout Italy.

- The liberal establishment, fearing a Soviet-style revolution, started to endorse the small National Fascist Party led by Benito Mussolini.

- In the night between October 27-28, 1922, about 30,000 Fascist blackshirts (paramilitary of the Fascist party) gathered in Rome to demand the resignation of liberal Prime Minister Luigi Facta and the appointment of a new Fascist government. This event is called the “March on Rome.”

- Between 1925 and 1927, Mussolini progressively dismantled virtually all constitutional and conventional restraints on his power, building a police state.

- A law passed on Christmas Eve 1925 changed Mussolini’s formal title from “president of the Council of Ministers” to “head of the government” and thereafter he began styling himself as Il Duce (the leader).

- On October 25, 1936, Mussolini agreed to form a Rome-Berlin Axis, sanctioned by a cooperation agreement with Nazi Germany and signed in Berlin, forming the so-called Axis Powers of World War II.

Key Terms

- March on Rome

-

A march by which Italian dictator Benito Mussolini’s National Fascist Party came to power in the Kingdom of Italy.

- Benito Mussolini

-

An Italian politician, journalist, and leader of the National Fascist Party, ruling the country as Prime Minister from 1922 to 1943; he ruled constitutionally until 1925, when he dropped all pretense of democracy and set up a legal dictatorship.

- Blackshirts

-

The paramilitary wing of the National Fascist Party in Italy and after 1923, an all-volunteer militia of the Kingdom of Italy.

The socialist agitations that followed the devastation of World War I, inspired by the Russian Revolution, led to counter-revolution and repression throughout Italy. The liberal establishment, fearing a Soviet-style revolution, started to endorse the small National Fascist Party led by Benito Mussolini. In October 1922 the Blackshirts of the National Fascist Party attempted a coup (the “March on Rome”) which failed, but at the last minute, King Victor Emmanuel III refused to proclaim a state of siege and appointed Mussolini prime minister. Over the next few years, Mussolini banned all political parties and curtailed personal liberties, thus forming a dictatorship. These actions attracted international attention and eventually inspired similar dictatorships such as Nazi Germany and Francoist Spain.

In 1935, Mussolini invaded Ethiopia, resulting in international alienation and leading to Italy’s withdrawal from the League of Nations; Italy allied with Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan and strongly supported Francisco Franco in the Spanish civil war. In 1939, Italy annexed Albania, a de facto protectorate for decades. Italy entered World War II on June 10, 1940. After initially advancing in British Somaliland and Egypt, the Italians were defeated in East Africa, Greece, Russia and North Africa.

Mussolini’s Rise to Power

The Fascisti, led by one of Mussolini’s close confidants, Dino Grandi, formed armed squads of war veterans called Blackshirts (or squadristi) with the goal of restoring order to the streets of Italy with a strong hand. The blackshirts clashed with communists, socialists, and anarchists at parades and demonstrations; all of these factions were also involved in clashes against each other. The Italian government rarely interfered with the blackshirts’ actions, owing in part to a looming threat and widespread fear of a communist revolution. The Fascisti grew rapidly, within two years transforming themselves into the National Fascist Party at a congress in Rome. In 1921 Mussolini won election to the Chamber of Deputies for the first time.

In the night between October 27-28, 1922, about 30,000 Fascist blackshirts gathered in Rome to demand the resignation of liberal Prime Minister Luigi Facta and the appointment of a new Fascist government. This event is known as the “March on Rome.” On the morning of October 28, King Victor Emmanuel III, who according to the Albertine Statute held the supreme military power, refused the government request to declare martial law, leading to Facta’s resignation. The King then handed over power to Mussolini (who stayed in his headquarters in Milan during the talks) by asking him to form a new government. The King’s controversial decision has been explained by historians as a combination of delusions and fears; Mussolini enjoyed a wide support in the military and among the industrial and agrarian elites, while the King and the conservative establishment were afraid of a possible civil war and ultimately thought they could use Mussolini to restore law and order in the country, but failed to foresee the danger of a totalitarian evolution.

March on Rome

Mussolini and the Quadrumviri during the March on Rome in 1922. From left to right: Michele Bianchi, Emilio De Bono, Italo Balbo, and Cesare Maria De Vecchi.

As Prime Minister, the first years of Mussolini’s rule were characterized by a right-wing coalition government composed of Fascists, nationalists, liberals, and two Catholic clerics from the Popular Party. The Fascists made up a small minority in his original governments. Mussolini’s domestic goal was the eventual establishment of a totalitarian state with himself as supreme leader (Il Duce) a message that was articulated by the Fascist newspaper Il Popolo, now edited by Mussolini’s brother, Arnaldo. To that end, Mussolini obtained from the legislature dictatorial powers for one year (legal under the Italian constitution of the time). He favored the complete restoration of state authority with the integration of the Fasci di Combattimento into the armed forces (the foundation in January 1923 of the Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale) and the progressive identification of the party with the state. In political and social economy, he passed legislation that favored the wealthy industrial and agrarian classes (privatizations, liberalizations of rent laws, and dismantlement of the unions).

Between 1925 and 1927, Mussolini progressively dismantled virtually all constitutional and conventional restraints on his power, thereby building a police state. A law passed on Christmas Eve 1925 changed Mussolini’s formal title from “president of the Council of Ministers” to “head of the government” (though he was still called “Prime Minister” by most non-Italian outlets). Thereafter he began styling himself as Il Duce (the leader). He was no longer responsible to Parliament and could be removed only by the king. While the Italian constitution stated that ministers were responsible only to the sovereign, in practice it had become all but impossible to govern against the express will of Parliament. The Christmas Eve law ended this practice, and also made Mussolini the only person competent to determine the body’s agenda. This law transformed Mussolini’s government into a de facto legal dictatorship. Local autonomy was abolished, and podestàs appointed by the Italian Senate replaced elected mayors and councils.

Fascist Italy

Mussolini’s foremost priority was the subjugation of the minds of the Italian people and the use of propaganda to do so. A lavish cult of personality centered on the figure of Mussolini was promoted by the regime.

Mussolini pretended to incarnate the new fascist Übermensch, promoting an aesthetics of exasperated Machism and a cult of personality that attributed to him quasi-divine capacities. At various times after 1922, Mussolini personally took over the ministries of the interior, foreign affairs, colonies, corporations, defense, and public works. Sometimes he held as many as seven departments simultaneously as well as the premiership. He was also head of the all-powerful Fascist Party and the armed local fascist militia, the MVSN or “Blackshirts,” who terrorized incipient resistances in the cities and provinces. He would later form the OVRA, an institutionalized secret police that carried official state support. He thus succeeded in keeping power in his own hands and preventing the emergence of any rival.

All teachers in schools and universities had to swear an oath to defend the fascist regime. Newspaper editors were all personally chosen by Mussolini and no one without a certificate of approval from the fascist party could practice journalism. These certificates were issued in secret; Mussolini thus skillfully created the illusion of a “free press.” The trade unions were also deprived of independence and integrated into what was called the “corporative” system. The aim (never completely achieved), inspired by medieval guilds, was to place all Italians in various professional organizations or corporations under clandestine governmental control.

In his early years in power, Mussolini operated as a pragmatic statesman, trying to achieve advantages but never at the risk of war with Britain and France. An exception was the bombardment and occupation of Corfu in 1923, following an incident in which Italian military personnel charged by the League of Nations to settle a boundary dispute between Greece and Albania were assassinated by Greek bandits. At the time of the Corfu incident, Mussolini was prepared to go to war with Britain, and only desperate pleading by Italian Navy leadership, who argued that Italian Navy was no match for the British Royal Navy, persuaded him to accept a diplomatic solution. In a secret speech to the Italian military leadership in January 1925, Mussolini argued that Italy needed to win spazio vitale (vital space), and as such his ultimate goal was to join “the two shores of the Mediterranean and of the Indian Ocean into a single Italian territory.”

Path to War

By the late 1930s, Mussolini’s obsession with demography led him to conclude that Britain and France were finished as powers, and that Germany and Italy were destined to rule Europe if for no other reason than their demographic strength. Mussolini stated his belief that declining birth rates in France were “absolutely horrifying” and that the British Empire was doomed because a quarter of the British population was older than 50. As such, Mussolini believed that an alliance with Germany was preferable to an alignment with Britain and France as it was better to be allied with the strong instead of the weak. Mussolini saw international relations as a Social Darwinian struggle between “virile” nations with high birth rates that were destined to destroy “effete” nations with low birth rates. Such was the extent of Mussolini’s belief that it was Italy’s destiny to rule the Mediterranean because of the country’s high birth rate that he neglected much of the serious planning and preparations necessary for a war with the Western powers.

On October 25, 1936, Mussolini agreed to form a Rome-Berlin Axis, sanctioned by a cooperation agreement with Nazi Germany and signed in Berlin. At the Munich Conference in September 1938, Mussolini continued to pose as a moderate working for European peace while helping Nazi Germany annex the Sudetenland. The 1936 Axis agreement with Germany was strengthened by the Pact of Steel signed on May 22, 1939, which bound Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany in a full military alliance.

Hitler and Mussolini

On 25 October 1936, an Axis was declared between Italy and Germany.

31.1.3: Japanese Expansion

Pre-WWII Japan was characterized by political totalitarianism, ultranationalism, expansionism, and fascism culminating in Japan’s invasion of China in 1937.

Learning Objective

Identify Japanese actions taken in the interest of territorial expansion

Key Points

- During the early Shōwa period, Japan moved into political totalitarianism, ultranationalism, and fascism, as well as a series of expansionist wars culminating in Japan’s invasion of China in 1937.

- The rise of Japanese nationalism paralleled the growth of nationalism within the West.

- During the Manchurian Incident of 1931, radical army officers bombed a small portion of the South Manchuria Railroad and, falsely attributing the attack to the Chinese, invaded Manchuria.

- Japan’s expansionist ambitions led to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937.

- After their victory in the Chinese capital, the Japanese military committed the infamous Nanking Massacre, also known as the Rape of Nanking, which involved a massive number of civilian deaths including infants and elderly and the large-scale rape of Chinese women.

- In response to American economic sanctions, Japan forged an alliance with Germany and Italy in 1940 known as the Tripartite Pact.

Key Terms

- Tripartite Pact

-

An agreement between Germany, Japan, and Italy signed in Berlin on September 27, 1940 that created the alliance known as the Axis Powers of WWII.

- Manchurian Incident

-

A staged event engineered by Japanese military personnel as a pretext for the Japanese invasion in 1931 of northeastern China, known as Manchuria.

- Nanking Massacre

-

An episode of mass murder and rape committed by Japanese troops against the residents of Nanking.

The Shōwa period is the era of Japanese history corresponding to the reign of the Shōwa Emperor, Hirohito, from December 25, 1926, through January 7, 1989. The Shōwa period was longer than the reign of any previous Japanese emperor. During the pre-1945 period, Japan moved into political totalitarianism, ultranationalism, and fascism, as well as a series of expansionist wars culminating in Japan’s invasion of China in 1937. This was part of an overall global period of social upheavals and conflicts such as the Great Depression and the Second World War.

Rise of Nationalism

Prior to 1868, most Japanese more readily identified with their feudal domain rather than the idea of “Japan” as a whole. But with the introduction of mass education, conscription, industrialization, centralization, and successful foreign wars, Japanese nationalism became a powerful force in society. Mass education and conscription served as a means to indoctrinate the coming generation with “the idea of Japan” as a nation instead of a series of Daimyo (domains), supplanting loyalty to feudal domains with loyalty to the state. Industrialization and centralization gave the Japanese a strong sense that their country could rival Western powers technologically and socially. Moreover, successful foreign wars gave the populace a sense of martial pride in their nation.

The rise of Japanese nationalism paralleled the growth of nationalism within the West. Certain conservatives such as Gondō Seikei and Asahi Heigo saw the rapid industrialization of Japan as something that had to be tempered. It seemed, for a time, that Japan was becoming too “Westernized” and that if left unimpeded, something intrinsically Japanese would be lost. During the Meiji period, such nationalists railed against the unequal treaties, but in the years following the First World War, Western criticism of Japanese imperial ambitions and restrictions on Japanese immigration changed the focus of the nationalist movement in Japan.

During the first part of the Shōwa era, racial discrimination against other Asians was habitual in Imperial Japan, starting with Japanese colonialism. The Shōwa regime preached racial superiority and racialist theories based on the sacred nature of the Yamato-damashii.

Invasion of China

Left-wing groups were subject to violent suppression by the end of the Taishō period, and radical right-wing groups, inspired by fascism and Japanese nationalism, rapidly grew in popularity. The extreme right became influential throughout the Japanese government and society, notably within the Kwantung Army, a Japanese army stationed in China along the Japanese-owned South Manchuria Railroad. During the Manchurian Incident of 1931, radical army officers bombed a small portion of the South Manchuria Railroad and, falsely attributing the attack to the Chinese, invaded Manchuria. The Kwantung Army conquered Manchuria and set up the puppet government of Manchukuo there without permission from the Japanese government. International criticism of Japan following the invasion led to Japan withdrawing from the League of Nations.

Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai of the Seiyūkai Party attempted to restrain the Kwantung Army and was assassinated in 1932 by right-wing extremists. Because of growing opposition within the Japanese military and the extreme right to party politicians, who they saw as corrupt and self-serving, Inukai was the last party politician to govern Japan in the pre-World War II era. In February 1936 young radical officers of the Japanese Army attempted a coup d’état, assassinating many moderate politicians before the coup was suppressed. In its wake, the Japanese military consolidated its control over the political system and most political parties were abolished when the Imperial Rule Assistance Association was founded in 1940.

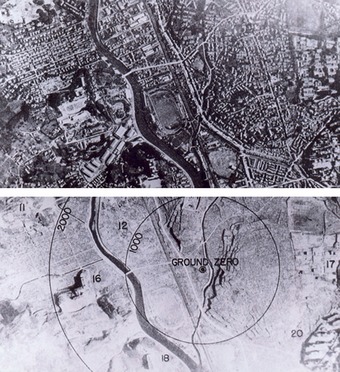

Japan’s expansionist vision grew increasingly bold. Many of Japan’s political elite aspired to have the country acquire new territory for resource extraction and settlement of surplus population. These ambitions led to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937. After their victory in the Chinese capital, the Japanese military committed the infamous Nanking Massacre, also known as the Rape of Nanking, which involved a massive number of civilian deaths including infants and elderly and the large-scale rape of Chinese women. The exact number of casualties is an issue of fierce debate between Chinese and Japanese historians; estimates range from 40,000 to 300,000 people.

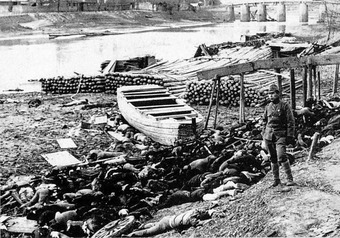

Rape of Nanking

The corpses of massacred victims from the Nanking Massacre on the shore of the Qinhuai River with a Japanese soldier standing nearby.

The Japanese military failed to defeat the Chinese government led by Chiang Kai-shek and the war descended into a bloody stalemate that lasted until 1945. Japan’s stated war aim was to establish the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a vast pan-Asian union under Japanese domination. Hirohito’s role in Japan’s foreign wars remains a subject of controversy, with various historians portraying him as either a powerless figurehead or an enabler and supporter of Japanese militarism.

The United States opposed Japan’s invasion of China and responded with increasingly stringent economic sanctions intended to deprive Japan of the resources to continue its war in China. Japan reacted by forging an alliance with Germany and Italy in 1940, known as the Tripartite Pact, which worsened its relations with the U.S. In July 1941, the U.S., Great Britain, and the Netherlands froze all Japanese assets when Japan completed its invasion of French Indochina by occupying the southern half of the country, further increasing tension in the Pacific.

31.2: The Allied Powers

31.2.1: The USSR

During Stalin’s totalitarian rule of the Soviet Union, he transformed the state through aggressive economic planning, the development of a cult of personality around himself, and the violent repression of so-called “enemies of the working class,” overseeing the murder of millions of Soviet citizens.

Learning Objective

Analyze the political atmosphere of the Soviet Union

Key Points

- After being appointed General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1922, Joseph Stalin sought to destroy his enemies while transforming Soviet society with aggressive economic planning, in particular a sweeping collectivization of agriculture and rapid development of heavy industry.

- Stalin consolidated his power within the party and the state to degree of a cult of personality.

- Soviet secret-police and the mass-mobilization Communist party served as Stalin’s major tools in molding Soviet society.

- Stalin’s brutal methods to achieve his goals, which included party purges, political repression of the general population, and forced collectivization, led to millions of deaths in Gulag labor camps and during man-made famine.

- In August 1939, after failed attempts to conclude anti-Hitler pacts with other major European powers, Stalin entered into a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. This agreement divided their influence and territory within Eastern Europe, resulting in their invasion of Poland in September of that year.

Key Terms

- Bolsheviks

-

The founding and ruling political party of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, a communist party organized on the basis of democratic centralism.

- Joseph Stalin

-

The leader and effective dictator of the Soviet Union from the mid-1920s until his death in 1953.

- First Five-Year Plan

-

A list of economic goals created by General Secretary Joseph Stalin and based on his policy of Socialism in One Country, implemented between 1928 and 1932, that focused on the forced collectivization of agriculture.

The Rise of Stalin

From its creation, the government in the Soviet Union was based on the one-party rule of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks). The stated purpose of the one-party state was to ensure that capitalist exploitation would not return to the Soviet Union and that the principles of democratic centralism would be effective in representing the people’s will in a practical manner. Debate over the future of the economy provided the background for a power struggle in the years after Lenin’s death in 1924. Initially, Lenin was to be replaced by a “troika” (“collective leadership”) consisting of Grigory Zinoviev of the Ukrainian SSR, Lev Kamenev of the Russian SFSR, and Joseph Stalin of the Transcaucasian SFSR.

On April 3, 1922, Stalin was named the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Lenin had appointed Stalin the head of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate, which gave Stalin considerable power. By gradually consolidating his influence and isolating and outmaneuvering his rivals within the party, Stalin became the undisputed leader of the Soviet Union and by the end of the 1920s had established totalitarian rule. In October 1927, Grigory Zinoviev and Leon Trotsky were expelled from the Central Committee and forced into exile.

In 1928, Stalin introduced the First Five-Year Plan for building a socialist economy. In place of the internationalism expressed by Lenin throughout the Revolution, it aimed to build Socialism in One Country. In industry, the state assumed control over all existing enterprises and undertook an intensive program of industrialization. In agriculture, rather than adhering to the “lead by example” policy advocated by Lenin, forced collectivization of farms was implemented all over the country. This was intended to increase agricultural output from large-scale mechanized farms, bring the peasantry under more direct political control, and make tax collection more efficient. Collectivization brought social change on a scale not seen since the abolition of serfdom in 1861 and alienation from control of the land and its produce. Collectivization also meant a drastic drop in living standards for many peasants, leading to violent reactions.

Purges and Executions

From collectivization, famines ensued, causing millions of deaths; surviving kulaks were persecuted and many sent to Gulags to do forced labour. Social upheaval continued in the mid-1930s. Stalin’s Great Purge resulted in the execution or detainment of many “Old Bolsheviks” who had participated in the October Revolution with Lenin. During the Great Purge, Lenin undertook a massive campaign of repression of the party, government, armed forces, and intelligentsia, in which millions of so-called “enemies of the working class” were imprisoned, exiled, or executed, often without due process. Major figures in the Communist Party and government, and many Red Army high commanders, were killed after being convicted of treason in show trials. According to declassified Soviet archives, in 1937 and 1938, the NKVD arrested more than 1.5 million people, of whom 681,692 were shot. Over those two years, that averages to over 1,000 executions a day. According to historian Geoffrey Hosking, “…excess deaths during the 1930s as a whole were in the range of 10–11 million.”

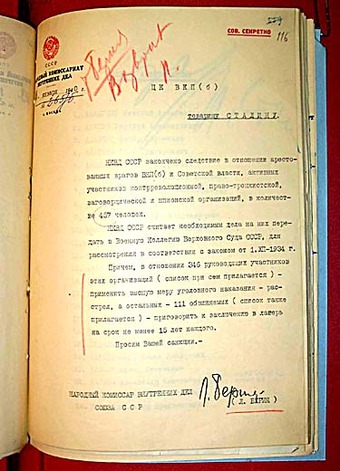

Letter to Stalin

Lavrentiy Beria’s January 1940 letter to Stalin asking permission to execute 346 “enemies of the CPSU and of the Soviet authorities” who conducted “counter-revolutionary, right-Trotskyite plotting and spying activities.”

Cult of Personality

Cults of personality developed in the Soviet Union around both Stalin and Lenin. Numerous towns, villages and cities were renamed after the Soviet leader and the Stalin Prize and Stalin Peace Prize were named in his honor. He accepted grandiloquent titles (e.g., “Coryphaeus of Science,” “Father of Nations,” “Brilliant Genius of Humanity,” “Great Architect of Communism,” “Gardener of Human Happiness,” and others), and helped rewrite Soviet history to provide himself a more significant role in the revolution of 1917. At the same time, according to Nikita Khrushchev, he insisted that he be remembered for “the extraordinary modesty characteristic of truly great people.” Although statues of Stalin depict him at a height and build approximating the very tall Tsar Alexander III, sources suggest he was approximately 5 feet 4 inches.

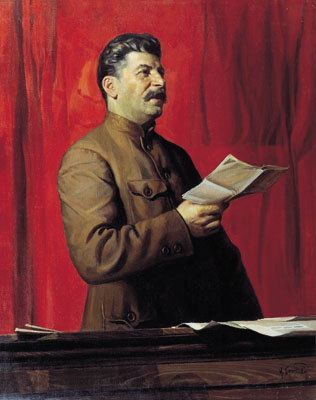

Portrait of Stalin

Stalin depicted in the style of Socialist Realism. Painting by Isaak Brodsky.

International Relations Pre-WWII

The early 1930s saw closer cooperation between the West and the USSR. From 1932 to 1934, the Soviet Union participated in the World Disarmament Conference. In 1933, diplomatic relations between the United States and the USSR were established when in November, newly elected President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt chose to formally recognize Stalin’s Communist government and negotiated a new trade agreement between the two nations. In September 1934, the Soviet Union joined the League of Nations. After the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, the USSR actively supported the Republican forces against the Nationalists, who were supported by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany.

In December 1936, Stalin unveiled a new Soviet Constitution. This document was seen as a personal triumph for Stalin, who on this occasion was described by Pravda as a “genius of the new world, the wisest man of the epoch, the great leader of communism.” By contrast, Western historians and historians from former Soviet occupied countries have viewed the constitution as a meaningless propaganda document.

The late 1930s saw a shift towards the Axis powers. In 1939, almost a year after the United Kingdom and France concluded the Munich Agreement with Germany, the USSR dealt with the Nazis both militarily and economically during extensive talks. The two countries concluded the German–Soviet Nonaggression Pact and the German–Soviet Commercial Agreement in August 1939. The nonaggression pact made possible Soviet occupation of Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Bessarabia, northern Bukovina, and eastern Poland. In late November of the same year, unable to coerce the Republic of Finland by diplomatic means into moving its border 16 miles back from Leningrad, Joseph Stalin ordered the invasion of Finland.

In the east, the Soviet military won several decisive victories during border clashes with the Empire of Japan in 1938 and 1939. However, in April 1941 USSR signed the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact with the Empire of Japan, recognizing the territorial integrity of Manchukuo, a Japanese puppet state.

31.2.2: France at the End of the Interwar Period

During the interwar period, war-torn France collected reparations from Germany, in some cases through occupation, suffered social upheaval and the consequent rise of socialism, and promoted defensive foreign policies.

Learning Objective

Describe the state of France prior to 1939

Key Points

- Foreign policy was of central interest to France during the interwar period.

- Because of the horrible devastation of the war, including the death of 1.5 million French soldiers, the destruction of much of the steel and coal regions, and the long-term costs for veterans, France demanded that Germany assume many of the costs incurred from the war through annual reparation payments.

- As a response to the failure of the Weimar Republic to pay reparations in the aftermath of World War I, France occupied the industrial region of the Ruhr as a means of ensuring repayments from Germany.

- In the 1920s, France established an elaborate system of border defenses called the Maginot Line, designed to fight off any German attack.

- France experienced a mild financial depression during the time of the Great Depression, but saw a more potent social reaction to financial strain culminating in a riot in 1934.

- Socialist Leon Blum, leading the Popular Front, brought together Socialists and Radicals to become Prime Minister from 1936 to 1937.

Key Terms

- Maginot Line

-

A line of concrete fortifications, obstacles, and weapon installations that France constructed on the French side of its borders with Switzerland, Germany, and Luxembourg during the 1930s.

- Treaty of Versailles

-

One of the peace treaties at the end of World War I, which required “Germany [to] accept the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage” during the war.

- Weimar Republic

-

An unofficial designation for the German state between 1919 and 1933.

- Popular Front

-

An alliance of left-wing movements during the interwar period, including the French Communist Party (PCF), the French Section of the Workers’ International (SFIO), and the Radical and Socialist Party.

Losses from WWI, Gains from the Treaty of Versailles

The war brought great losses of manpower and resources. Fought in large part on French soil, it led to approximately 1.4 million French dead including civilians, and four times as many wounded. Peace terms were imposed by the Big Four, meeting in Paris in 1919: David Lloyd George of Britain, Vittorio Orlando of Italy, Georges Clemenceau of France, and Woodrow Wilson of the United States. Clemenceau demanded the harshest terms and won most of them in the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. Germany was forced to admit its guilt for starting the war, and its military was permanently weakened. Germany also had to pay huge sums in war reparations to the Allies (who in turn had large loans from the U.S. to pay off).

France regained Alsace-Lorraine and occupied the German industrial Saar Basin, a coal and steel region. The German African colonies were put under League of Nations mandates to be administered by France and other victors. From the remains of the Ottoman Empire, France acquired the Mandate of Syria and the Mandate of Lebanon.

Interwar Period

France was part of the Allied force that occupied the Rhineland following the Armistice. Foch supported Poland in the Greater Poland Uprising and in the Polish–Soviet War, and France also joined Spain during the Rif War. From 1925 until his death in 1932, Aristide Briand, as prime minister during five short intervals, directed French foreign policy, using his diplomatic skills and sense of timing to forge friendly relations with Weimar Germany as the basis of a genuine peace within the framework of the League of Nations. He realized France could neither contain the much larger Germany by itself nor secure effective support from Britain or the League.

As a response to the failure of the Weimar Republic to pay reparations in the aftermath of World War I, France occupied the industrial region of the Ruhr to ensure repayments from Germany. The intervention was a failure, and France accepted the American solution to the reparations issues expressed in the Dawes Plan and the Young Plan.

French Enter Essen

French cavalry entering Essen during the Occupation of the Ruhr.

In the 1920s, France established an elaborate system of border defenses called the Maginot Line, designed to fight off any German attack. (Unfortunately, the Maginot Line did not extend into Belgium, where Germany attacked in 1940.) Military alliances were signed with weak powers in 1920–21, called the “Little Entente.”

Great Depression and Social Upheaval

The worldwide financial crisis affected France a bit later than other countries, hitting around 1931. While the GDP in the 1920s grew at the very strong rate of 4.43% per year, the 1930s rate fell to only 0.63%. The depression was relatively mild: unemployment peaked under 5% and the fall in production was at most 20% below the 1929 output; there was no banking crisis.

In contrast to the mild economic upheaval, though, the political upheaval was enormous. After 1931, rising unemployment and political unrest led to the February 6, 1934, riots. Socialist Leon Blum, leading the Popular Front, brought together Socialists and Radicals to become Prime Minister from 1936 to 1937; he was the first Jew and the first Socialist to lead France. The Communists in the Chamber of Deputies (parliament) voted to keep the government in power and generally supported its economic policies, but rejected its foreign policies. The Popular Front passed numerous labor reforms, which increased wages, cut working hours to 40 hours with overtime illegal, and provided many lesser benefits to the working class, such as mandatory two-week paid vacations. However, renewed inflation canceled the gains in wage rates, unemployment did not fall, and economic recovery was very slow. Historians agree that the Popular Front was a failure in terms of economics, foreign policy, and long-term stability. At first the Popular Front created enormous excitement and expectations on the left—including large-scale sitdown strikes—but in the end it failed to live up to its promise. In the long run, however, later Socialists took inspiration from the attempts of the Popular Front to set up a welfare state.

Foreign Relations

The government joined Britain in establishing an arms embargo during the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). Blum rejected support for the Spanish Republicans because of his fear that civil war might spread to deeply divided France. Financial support in military cooperation with Poland was also a policy. The government nationalized arms suppliers and dramatically increased its program of rearming the French military in a last-minute catch up with the Germans.

Appeasement of Germany in cooperation with Britain was the policy after 1936, as France sought peace even in the face of Hitler’s escalating demands. Édouard Daladier refused to go to war against Germany and Italy without British support as Neville Chamberlain wanted to save peace at Munich in 1938.

31.2.3: The United Kingdom and Appeasement

Vivid memories of the horrors and deaths of the World War made Britain and its leaders strongly inclined to pacifism in the interwar era, exemplified by their policy of appeasement toward Nazi Germany, which led to the German annexation of Austria and parts of Czechoslovakia.

Learning Objective

Explain why Prime Minister Chamberlain followed the policy of appeasement

Key Points

- World War I was won by Britain and its allies at a terrible human and financial cost, creating a sentiment to avoid war at all costs.

- The theory that dictatorships arose where peoples had grievances and that by removing the source of these grievances the dictatorship would become less aggressive led to Britain’s policy of appeasement.

- One major example of appeasement was when Britain learned of Hitler’s intention to annex Austria, which Chamberlain’s government decided it was unable to stop and thus acquiesced to what later became known as the Anschluss of March 1938.

- When Germany intended to annex parts of Czechoslovakia, Britain and other European powers came together without consulting Czechoslovakia and created the Munich Agreement, allowing Hitler to take over portions of Czechoslovakia named the Sudetenland.

Key Terms

- Munich Agreement

-

A settlement permitting Nazi Germany’s annexation of portions of Czechoslovakia along the country’s borders mainly inhabited by German speakers, for which a new territorial designation “Sudetenland” was coined.

- appeasement

-

A diplomatic policy of making political or material concessions to an enemy power in order to avoid conflict.

- Anschluss

-

The Nazi propaganda term for the annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany in March 1938.

The Policy of Appeasement

World War I was won by Britain and its allies at a terrible human and financial cost, creating a sentiment that wars should be avoided at all costs. The League of Nations was founded with the idea that nations could resolve their differences peacefully. As with many in Europe who had witnessed the horrors of the First World War and its aftermath, United Kingdom Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was committed to peace. The theory was that dictatorships arose where peoples had grievances, and that by removing the source of these grievances, the dictatorship would become less aggressive. His attempts to deal with Nazi Germany through diplomatic channels and quell any sign of dissent from within, particularly from Churchill, were called by Chamberlain “the general policy of appeasement.”

Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement emerged from the failures of the League of Nations and of collective security. The League of Nations was set up in the aftermath of World War I in the hope that international cooperation and collective resistance to aggression might prevent another war. Members of the League were entitled to assist other members if they came under attack. The policy of collective security ran in parallel with measures to achieve international disarmament and where possible was based on economic sanctions against an aggressor. It appeared ineffectual when confronted by the aggression of dictators, notably Germany’s Remilitarization of the Rhineland and Italian leader Benito Mussolini’s invasion of Abyssinia.

Anschluss

The first European crisis of Chamberlain’s premiership was over the German annexation of Austria. The Nazi regime was already behind the assassination of Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss in 1934 and was now pressuring Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg. Informed of Germany’s objectives, Chamberlain’s government decided it was unable to stop these events and acquiesced to what later became known as the Anschluss of March 1938. Although the victorious Allies of World War I had prohibited the union of Austria and Germany, their reaction to the Anschluss was mild. Even the strongest voices against annexation, those of Fascist Italy, France, and Britain, were not backed by force. In the House of Commons Chamberlain said that “The hard fact is that nothing could have arrested what has actually happened [in Austria] unless this country and other countries had been prepared to use force.” The American reaction was similar. The international reaction to the events of March 12, 1938 led Hitler to conclude that he could use even more aggressive tactics in his plan to expand the Third Reich. The Anschluss paved the way for Munich in September 1938 because it indicated the likely non-response of Britain and France to future German aggression.

Anschluss

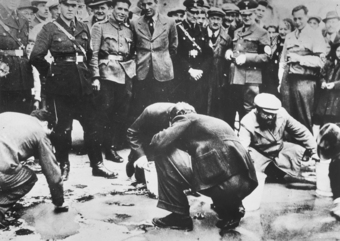

Immediately after the Anschluss, Vienna’s Jews were forced to wash pro-independence slogans from the city’s pavements.

The Sudetenland Crisis and the Munich Agreement

The second crisis came over the Sudetenland area of Czechoslovakia, home to a large ethnic German minority. Under the guise of seeking self-determination for the Sudeten Germans, Hitler planned to launch a war of aggression on October 1, 1938. In an effort to defuse the looming crisis, Chamberlain followed a strategy of pressuring Prague to make concessions to the ethnic Germans while warning Berlin about the dangers of war. The problems of the tight wire act were well-summarized by the Chancellor the Exchequer Sir John Simon in a diary entry during the May Crisis of 1938:

We are endeavoring at one & the same time, to restrain Germany by warning her that she must not assume we could remain neutral if she crossed the frontier; to stimulate Prague to make concessions; and to make sure that France will not take some rash action such as mobilization (when has mobilization been anything but a prelude to war?), under the delusion that we would join her in defense of Czechoslovakia. We won’t and can’t-but an open declaration to this effect would only give encouragement to Germany’s intransigence.

In a letter to his sister, Chamberlain wrote that he would contact Hitler to tell him “The best thing you [Hitler] can do is tell us exactly what you want for your Sudeten Germans. If it is reasonable we will urge the Czechs to accept and if they do, you must give assurances that you will let them alone in the future.”

Out of these attitudes grew what is known as the Munich Agreement, signed on September 30, 1938, a settlement permitting Nazi Germany’s annexation of portions of Czechoslovakia along the country’s borders mainly inhabited by German speakers. The purpose of the conference was to discuss the future of the Sudetenland in the face of ethnic demands made by Adolf Hitler. The agreement was signed by Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and Italy. Sudetenland was of immense strategic importance to Czechoslovakia, as most of its border defenses and banks were situated there along with heavy industrial districts. Because the state of Czechoslovakia was not invited to the conference, it considered itself betrayed and refers to this agreement as the “Munich Betrayal.”

Czechoslovakia was informed by Britain and France that it could either resist Nazi Germany alone or submit to the prescribed annexations. The Czechoslovak government, realizing the hopelessness of fighting the Nazis alone, reluctantly capitulated and agreed to abide by the agreement. The settlement gave Germany the Sudetenland starting October 10 and de facto control over the rest of Czechoslovakia as long as Hitler promised to go no further. On September 30 after some rest, Chamberlain went to Hitler and asked him to sign a peace treaty between the United Kingdom and Germany. After Hitler’s interpreter translated it for him, he happily agreed.

Munich Agreement

From left to right: Chamberlain, Daladier, Hitler, Mussolini, and Ciano pictured before signing the Munich Agreement, which gave the Sudetenland to Germany.

31.2.4: American Isolationism

As Europe moved closer to war in the late 1930s, the United States Congress continued to demand American neutrality, but President Roosevelt and the American public began to support war with Nazi Germany by 1941.

Learning Objective

Describe why the United States initially stayed out of the war

Key Points

- In the wake of the First World War, non-interventionist tendencies of U.S. foreign policy and resistance to the League of Nations gained ascendancy, led by Republicans in the Senate such as William Borah and Henry Cabot Lodge.

- Although the U.S. was unwilling to commit to the League of Nations, they continued to engage in international negotiations and treaties that sought international peace.

- The economic depression that ensued after the Crash of 1929 further committed the United States to doctrine of isolationism, the nation focusing instead on economic recovery.

- Between 1936 and 1937, much to the dismay of President Roosevelt, Congress passed the Neutrality Acts, which included an act forbidding Americans from sailing on ships flying the flag of a belligerent nation or trading arms with warring nations.

- When the war broke out in Europe after Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, the American people split into two camps: non-interventionists and interventionists.

- As 1940 became 1941, the actions of the Roosevelt administration made it more and more clear that the U.S. was on a course to war.

- By late 1941, 72% of Americans agreed that “the biggest job facing this country today is to help defeat the Nazi Government,” and 70% thought that defeating Germany was more important than staying out of the war.

Key Terms

- Lend-Lease Act

-

A program under which the United States supplied Free France, the United Kingdom, the Republic of China, and later the USSR and other Allied nations with food, oil, and materiel between 1941 and August 1945.

- Kellogg–Briand Pact

-

A 1928 international agreement in which signatory states promised not to use war to resolve “disputes or conflicts of whatever nature or of whatever origin they may be, which may arise among them.”

Interwar Period

In the wake of the First World War, non-interventionist tendencies of U.S. foreign policy gained ascendancy. The Treaty of Versailles and thus U.S. participation in the League of Nations, even with reservations, was rejected by the Republican-dominated Senate in the final months of Wilson’s presidency. A group of senators known as the Irreconcilables, identifying with both William Borah and Henry Cabot Lodge, had great objections regarding the clauses of the treaty which compelled America to come to the defense of other nations. Lodge, echoing Wilson, issued 14 Reservations regarding the treaty; among them, the second argued that America would sign only with the understanding that:

Nothing compels the United States to ensure border contiguity or political independence of any nation, to interfere in foreign domestic disputes regardless of their status in the League, or to command troops or ships without Congressional declaration of war.

While some of the sentiment was grounded in adherence to Constitutional principles, some bore a reassertion of nativist and inward-looking policy.

Although the U.S. was unwilling to commit to the League of Nations, they continued to engage in international negotiations and treaties. In August 1928, 15 nations signed the Kellogg-Briand Pact, brainchild of American Secretary of State Frank Kellogg and French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand. This pact, said to outlaw war and show the U.S. commitment to international peace, had its semantic flaws. For example, it did not hold the U.S. to the conditions of any existing treaties, still allowed European nations the right to self-defense, and stated that if one nation broke the Pact, it would be up to the other signatories to enforce it. The Kellogg–Briand Pact was more of a sign of good intentions on the part of the U.S. than a legitimate step towards the sustenance of world peace.

The economic depression that ensued after the Crash of 1929 also encouraged non-intervention. The country focused mostly on addressing the problems of the national economy while the rise of aggressive expansionism policies by Fascist Italy and the Empire of Japan led to conflicts such as the Italian conquest of Ethiopia and the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. These events led to ineffectual condemnations by the League of Nations, while official American response was muted. America also did not take sides in the brutal Spanish Civil War.

Non-Intervention Before Entering WWII

As Europe moved closer to war in the late 1930s, the U.S. Congress continued to demand American neutrality. Between 1936 and 1937, much to the dismay of President Roosevelt, Congress passed the Neutrality Acts. For example, in the final Neutrality Act, Americans could not sail on ships flying the flag of a belligerent nation or trade arms with warring nations. Such activities played a role in American entrance into World War I.

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland and Britain and France subsequently declared war on Germany, marking the start of World War II. In an address to the American people two days later, President Roosevelt assured the nation that he would do all he could to keep them out of war. However, his words showed his true goals. “When peace has been broken anywhere, the peace of all countries everywhere is in danger,” Roosevelt said. Even though he was intent on neutrality as the official policy of the U.S., he still echoed the dangers of staying out of the war. He also cautioned the American people to not let their wish to avoid war at all costs supersede the security of the nation.

The war in Europe split the American people into two camps: non-interventionists and interventionists. The sides argued over America’s involvement in this Second World War. The basic principle of the interventionist argument was fear of German invasion. By the summer of 1940, France suffered a stunning defeat by Germans, and Britain was the only democratic enemy of Germany. In a 1940 speech, Roosevelt argued, “Some, indeed, still hold to the now somewhat obvious delusion that we … can safely permit the United States to become a lone island … in a world dominated by the philosophy of force.” A national survey found that in the summer of 1940, 67% of Americans believed that a German-Italian victory would endanger the United States, that if such an event occurred 88% supported “arm[ing] to the teeth at any expense to be prepared for any trouble”, and that 71% favored “the immediate adoption of compulsory military training for all young men.”

Ultimately, the ideological rift between the ideals of the U.S. and the goals of the fascist powers empowered the interventionist argument. Writer Archibald MacLeish asked, “How could we sit back as spectators of a war against ourselves?” In an address to the American people on December 29, 1940, President Roosevelt said, “the Axis not merely admits but proclaims that there can be no ultimate peace between their philosophy of government and our philosophy of government.”

However, there were many who held on to non-interventionism. Although a minority, they were well-organized and had a powerful presence in Congress. Non-interventionists rooted a significant portion of their arguments in historical precedent, citing events such as Washington’s farewell address and the failure of World War I. “If we have strong defenses and understand and believe in what we are defending, we need fear nobody in this world,” Robert Maynard Hutchins, President of the University of Chicago, wrote in a 1940 essay. Isolationists believed that the safety of the nation was more important than any foreign war.

“No Foreign Entanglements”

Protest march to prevent American involvement in World War II before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

As 1940 became 1941, the actions of the Roosevelt administration made it more and more clear that the U.S. was on a course to war. This policy shift, driven by the President, came in two phases. The first came in 1939 with the passage of the Fourth Neutrality Act, which permitted the U.S. to trade arms with belligerent nations as long as these nations came to America to retrieve the arms and paid for them in cash. This policy was quickly dubbed “Cash and Carry. The second phase was the Lend-Lease Act of early 1941, which allowed the President “to lend, lease, sell, or barter arms, ammunition, food, or any ‘defense article’ or any ‘defense information’ to ‘the government of any country whose defense the President deems vital to the defense of the United States.'” American public opinion supported Roosevelt’s actions. As U.S. involvement in the Battle of the Atlantic grew with incidents such as the sinking of the USS Reuben James (DD-245), by late 1941 72% of Americans agreed that “the biggest job facing this country today is to help defeat the Nazi Government,” and 70% thought that defeating Germany was more important than staying out of the war.

31.3: Hostilities Commence

31.3.1: September 1, 1939

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland under the false pretext that the Poles had carried out a series of sabotage operations against German targets near the border, an event that caused Britain and France to declare war on Germany.

Learning Objective

Summarize the events of September 1, 1939

Key Points

- Following several staged incidents that German propaganda used as a pretext to claim that German forces were acting in self-defense, the first regular act of war took place on September 1, 1939, when the Luftwaffe attacked the Polish town of Wieluń, destroying 75% of the city and killing close to 1,200 people, most of them civilians.

- As the Wehrmacht advanced, Polish forces withdrew from their forward bases of operation close to the Polish-German border to more established lines of defense to the east. After the mid-September Polish defeat in the Battle of the Bzura, the Germans gained an undisputed advantage.

- On September 3 after a British ultimatum to Germany to cease military operations was ignored, Britain and France declared war on Germany.

- On October 8, after an initial period of military administration, Germany directly annexed western Poland and the former Free City of Danzig and placed the remaining block of territory under the administration of the newly established General Government.

Key Terms

- Gleiwitz incident

-

A false flag operation by Nazi forces posing as Poles on August 31, 1939, against the German radio station Sender Gleiwitz in Gleiwitz, Upper Silesia, Germany on the eve of World War II in Europe. The goal was to use the staged attack as a pretext for invading Poland.

- Battle of the Border

-

Refers to the battles that occurred in the first days of the German invasion of Poland in September, 1939; the series of battles ended in a German victory as Polish forces were either destroyed or forced to retreat.

The Invasion of Poland

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, was a joint invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Free City of Danzig, the Soviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the beginning of World War II in Europe. The German invasion began on September 1, 1939, one week after the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, while the Soviet invasion commenced on September 17 following the Molotov-Tōgō agreement that terminated the Russian and Japanese hostilities in the east on September 16. The campaign ended on October 6 with Germany and the Soviet Union dividing and annexing the whole of Poland under the terms of the German-Soviet Frontier Treaty.

German forces invaded Poland from the north, south, and west the morning after the Gleiwitz incident. As the Wehrmacht advanced, Polish forces withdrew from their forward bases of operation close to the Polish-German border to more established lines of defense to the east. After the mid-September Polish defeat in the Battle of the Bzura, the Germans gained an undisputed advantage. Polish forces then withdrew to the southeast where they prepared for a long defense of the Romanian Bridgehead and awaited expected support and relief from France and the United Kingdom. While those two countries had pacts with Poland and declared war on Germany on September 3, in the end their aid to Poland was limited.

The Soviet Red Army’s invasion of Eastern Poland on September 17, in accordance with a secret protocol of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, rendered the Polish plan of defense obsolete. Facing a second front, the Polish government concluded that defense of the Romanian Bridgehead was no longer feasible and ordered an emergency evacuation of all troops to neutral Romania. On October 6, following the Polish defeat at the Battle of Kock, German and Soviet forces gained full control over Poland. The success of the invasion marked the end of the Second Polish Republic, though Poland never formally surrendered.

On October 8, after an initial period of military administration, Germany directly annexed western Poland and the former Free City of Danzig and placed the remaining block of territory under the administration of the newly established General Government. The Soviet Union incorporated its newly acquired areas into its constituent Belarusian and Ukrainian republics and immediately started a campaign of sovietization. In the aftermath of the invasion, a collective of underground resistance organizations formed the Polish Underground State within the territory of the former Polish state. Many military exiles who managed to escape Poland subsequently joined the Polish Armed Forces in the West, an armed force loyal to the Polish government in exile.

The Invasion of Poland

This map shows the beginning of World War II in September 1939 in a European context. The Second Polish Republic, one of the three original allies of World War II, was invaded and divided between the Third Reich and Soviet Union, acting together in line with the secret protocol of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, dividing Central and Eastern Europe between the two countries. The Polish allies of that time were France and Great Britain.

Details of September 1 Invasion

Following several staged incidents (like the Gleiwitz incident, part of Operation Himmler), in which German propaganda was used as a pretext to claim that German forces were acting in self-defense, the first regular act of war took place on September 1, 1939, when the Luftwaffe attacked the Polish town of Wieluń, destroying 75% of the city and killing close to 1,200 people, mostly civilians. This invasion subsequently began World War II. Five minutes later, the old German pre-dreadnought battleship Schleswig-Holstein opened fire on the Polish military transit depot at Westerplatte in the Free City of Danzig on the Baltic Sea. Four hours later, German troops—still without a formal declaration of war issued—attacked near the Polish town of Mokra. The Battle of the Border had begun. Later that day, Germans attacked on Poland’s western, southern and northern borders while German aircraft began raids on Polish cities. The main axis of attack led eastwards from Germany proper through the western Polish border. Supporting attacks came from East Prussia in the north and a co-operative German-Slovak tertiary attack by units from German-allied Slovakia in the south. All three assaults converged on the Polish capital of Warsaw.

Invasion of Poland

Soldiers of the German Wehrmacht tearing down the border crossing between Poland and the Free City of Danzig, September 1, 1939.

War Erupts

On September 3 after a British ultimatum to Germany to cease military operations was ignored, Britain and France, followed by the fully independent Dominions of the British Commonwealth—Australia (3 September), Canada (10 September), New Zealand (3 September), and South Africa (6 September)—declared war on Germany. However, initially the alliance provided limited direct military support to Poland, consisting of a cautious, half-hearted French probe into the Saarland.

The German-French border saw only a few minor skirmishes, although the majority of German forces, including 85% of their armored forces, were engaged in Poland. Despite some Polish successes in minor border battles, German technical, operational, and numerical superiority forced the Polish armies to retreat from the borders towards Warsaw and Lwów. The Luftwaffe gained air superiority early in the campaign. By destroying communications, the Luftwaffe increased the pace of the advance, overrunning Polish airstrips and early warning sites and causing logistical problems for the Poles. Many Polish Air Force units ran low on supplies, and 98 withdrew into then-neutral Romania. The Polish initial strength of 400 was reduced to just 54 by September 14, and air opposition virtually ceased.

The Western Allies also began a naval blockade of Germany, which aimed to damage the country’s economy and war effort. Germany responded by ordering U-boat warfare against Allied merchant and warships, which later escalated into the Battle of the Atlantic.

31.3.2: German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship

The German-Soviet Treaty of Friendship was a secret supplementary protocol of the 1939 Hitler-Stalin Pact, signed on September 28, 1939, by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union after their joint invasion and occupation of sovereign Poland that delineated the spheres of interest between the two powers.

Learning Objective

Argue for and against the Soviet Union’s decision to sign the Treaty of Friendship with the Third Reich

Key Points

- The German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Demarcation was a secret supplementary protocol of the 1939 Hitler-Stalin Pact, amended on September 28, 1939, by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union after their joint invasion and occupation of sovereign Poland.

- These amendments allowed for the exchange of Soviet and German nationals between the two occupied zones of Poland, redrew parts of the central European spheres of interest dictated by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, and stated that neither party to the treaty would allow on its territory any “Polish agitation” directed at the other party.

- The existence of this secret protocol was denied by the Soviet government until 1989, when it was finally acknowledged and denounced.

- The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, also known as the Nazi-Soviet Pact, was a neutrality pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed in Moscow on August 23, 1939, that delineated the spheres of interest between the two powers.

Key Terms

- Wehrmacht

-

The unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1946, including army (Heer), navy (Kriegsmarine), and air force (Luftwaffe).

- German-Soviet Frontier Treaty

-

Also known as the The German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Demarcation, this treaty was a secret clause amended on the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact on September 28, 1939, by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union after their joint invasion and occupation of sovereign Poland.

- Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

-

A neutrality pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed in Moscow on August 23, 1939.

The German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Demarcation (later known as the German-Soviet Frontier Treaty) was a second supplementary protocol of the 1939 Hitler-Stalin Pact. It was a secret clause as amended on September 28, 1939, by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union after their joint invasion and occupation of sovereign Poland and thus after the beginning of World War II. It was signed by Joachim von Ribbentrop and Vyacheslav Molotov, the foreign ministers of Germany and the Soviet Union respectively, in the presence of Joseph Stalin. The treaty was a follow-up to the first secret protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact signed on August 23, 1939, between the two countries prior to their invasion of Poland and the start of World War II in Europe. Only a small portion of the protocol which superseded the first treaty was publicly announced, while the spheres of influence of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union remained classified. The third secret protocol of the Pact was signed on January 10, 1941 by Friedrich Werner von Schulenberg and Molotov, in which Germany renounced its claims to portions of Lithuania only a few months before its anti-Soviet Operation Barbarossa.

Secret Articles

Several secret articles were attached to the treaty. These allowed for the exchange of Soviet and German nationals between the two occupied zones of Poland, redrew parts of the central European spheres of interest dictated by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, and stated that neither party would allow on its territory any “Polish agitation” directed at the other party.

During the western invasion of Poland, the German Wehrmacht had taken control of the Lublin Voivodeship and eastern Warsaw Voivodeship, territories that according to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact were in the Soviet sphere of influence. To compensate the Soviet Union for this “loss,” the treaty’s secret attachment transferred Lithuania to the Soviet sphere of influence, with the exception of a small territory in the Suwałki Region sometimes known as the Suwałki Triangle. After this transfer, the Soviet Union issued an ultimatum to Lithuania, occupied it on June 15, 1940, and established the Lithuanian SSR.

The existence of this secret protocol was denied by the Soviet government until 1989, when it was finally acknowledged and denounced. Some time later, the new Russian revisionists, including historians Alexander Dyukov and Nataliya Narotchnitskaya, described the pact as a necessary measure because of the British and French failure to enter into an anti-fascist pact. Vladimir Putin has also defended the pact.

German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship

Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov signs the German–Soviet Pact in Moscow, September 28, 1939; behind him are Richard Schulze-Kossens (Ribbentrop’s adjutant), Boris Shaposhnikov (Red Army Chief of Staff), Joachim von Ribbentrop, Joseph Stalin, Vladimir Pavlov (Soviet translator). Alexey Shkvarzev (Soviet ambassador in Berlin), stands next to Molotov.

Background: Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, also known as the Nazi-Soviet Pact, was a neutrality pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed in Moscow on August 23, 1939 by foreign ministers Joachim von Ribbentrop and Vyacheslav Molotov, respectively.

The pact delineated the spheres of interest between the two powers, confirmed by the supplementary protocol of the German-Soviet Frontier Treaty amended after the joint invasion of Poland. The pact remained in force for nearly two years until the German government of Adolf Hitler launched an attack on the Soviet positions in Eastern Poland during Operation Barbarossa on June 22, 1941.

The clauses of the Nazi-Soviet Pact provided a written guarantee of non-belligerence by each party towards the other and a declared commitment that neither government would ally itself to or aid an enemy of the other party. In addition to stipulations of non-aggression, the treaty included a secret protocol that divided territories of Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, and Romania into German and Soviet “spheres of influence,” anticipating “territorial and political rearrangements” of these countries. Thereafter, Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. Soviet Union leader Joseph Stalin ordered the Soviet invasion of Poland on September 17, a day after the Soviet–Japanese ceasefire agreement came into effect. In November, parts of southeastern Finland were annexed by the Soviet Union after the Winter War. This was followed by Soviet annexations of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and parts of Romania. Advertised concern about ethnic Ukrainians and Belarusians had been proffered as justification for the Soviet invasion of Poland. Stalin’s invasion of Bukovina in 1940 violated the pact as it went beyond the Soviet sphere of influence agreed with the Axis.

31.3.3: Dunkirk and Vichy France

The Dunkirk evacuation was the removal of Allied soldiers from the beaches and harbor of Dunkirk by the attack of German soldiers, which started as a disaster but soon became a miraculous triumph.

Learning Objective

Evaluate the success or failure of the evacuation at Dunkirk

Key Points

- During the 1930s, the French constructed the Maginot Line, a series of fortifications along their border with Germany.