30.1: Rebuilding Europe

30.1.1: Reparations

The victorious Allies of WWI imposed harsh reparations on Germany, which were both economically and psychologically damaging. Historians have long argued over the extent to which the reparations led to Germany’s severe economic depression in the interwar period.

Learning Objective

Defend and critique the decision to demand high reparations from Germany after the war

Key Points

- One of the most contentious decisions at the Paris Peace Conference was the question of war reparations, payments intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war.

- Most of the war’s major battles occurred in France, and the French countryside was heavily damaged in the fighting, leading French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau to push for harsh reparations from Germany to rebuild France.

- Both the British and American representatives at the Conference (David Lloyd George and Woodrow Wilson) opposed these harsh reparations, believing they would create economic instability in Europe overall, but in the end the Conference decided that Germany was to pay 132 billion gold marks (USD $33 billion) in reparations, a decision that angered the Germans and was a source of resentment for decades to come.

- Because of the lack of reparation payments by Germany, France occupied the Ruhr in 1923 to enforce payments, causing an international crisis that resulted in the implementation of the Dawes Plan in 1924. This raised money from other nations to help Germany pay and shifted the payment plan.

- Again, Germany was unable to pay and the plan was revised again with a reduced sum and more lenient plan.

- With the collapse of the German economy in 1931, reparations were suspended for a year and in 1932 during the Lausanne Conference they were cancelled altogether.

- Between 1919 and 1932, Germany paid fewer than 21 billion marks in reparations.

Key Terms

- Young Plan

-

A program for settling German reparations debts after World War I, written in 1929 and formally adopted in 1930. After the Dawes Plan was put into operation in 1924, it became apparent that Germany would not willingly meet the annual payments over an indefinite period of time. This new plan reduced further payments by about 20 percent.

- indemnities

-

An obligation by a person to provide compensation for a particular loss suffered by another person.

- reparations

-

Payments intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war. Generally, the term refers to money or goods changing hands, but not to the annexation of land.

World War I reparations were imposed upon the Central Powers during the Paris Peace Conference following their defeat in the First World War by the Allied and Associate Powers. Each defeated power was required to make payments in either cash or kind. Because of the financial situation Austria, Hungary, and Turkey found themselves in after the war, few to no reparations were paid and the requirements were cancelled. Bulgaria paid only a fraction of what was required before its reparations were reduced and then cancelled. Historian Ruth Henig argues that the German requirement to pay reparations was the “chief battleground of the post-war era” and “the focus of the power struggle between France and Germany over whether the Versailles Treaty was to be enforced or revised.”

The Treaty of Versailles and the 1921 London Schedule of Payments required Germany to pay 132 billion gold marks (USD $33 billion) in reparations to cover civilian damage caused during the war. This figure was divided into three categories of bonds: A, B, and C. Of these, Germany was only required to pay towards ‘A’ and ‘B’ bonds totaling 50 billion marks (USD $12.5 billion). The remaining ‘C’ bonds, which Germany did not have to pay, were designed to deceive the Anglo-French public into believing Germany was being heavily fined and punished for the war.

Because of the lack of reparation payments by Germany, France occupied the Ruhr in 1923 to enforce payments, causing an international crisis that resulted in the implementation of the Dawes Plan in 1924. This plan outlined a new payment method and raised international loans to help Germany to meet her reparation commitments. In the first year following the implementation of the plan, Germany would have to pay 1 billion marks. This would rise to 2.5 billion marks per year by the fifth year of the plan. A Reparations Agency was established with Allied representatives to organize the payment of reparations. Despite this, by 1928 Germany called for a new payment plan, resulting in the Young Plan that established the German reparation requirements at 112 billion marks (USD $26.3 billion) and created a schedule of payments that would see Germany complete payments by 1988. With the collapse of the German economy in 1931, reparations were suspended for a year and in 1932 during the Lausanne Conference they were cancelled altogether. Between 1919 and 1932, Germany paid fewer than 21 billion marks in reparations.

The German people saw reparations as a national humiliation; the German Government worked to undermine the validity of the Treaty of Versailles and the requirement to pay. British economist John Maynard Keynes called the treaty a Carthaginian peace that would economically destroy Germany. His arguments had a profound effect on historians, politicians, and the public. Despite Keynes’ arguments and those by later historians supporting or reinforcing Keynes’ views, the consensus of contemporary historians is that reparations were not as intolerable as the Germans or Keynes had suggested and were within Germany’s capacity to pay had there been the political will to do so.

Background

Most of the war’s major battles occurred in France, substantially damaging the French countryside. Furthermore, in 1918 during the German retreat, German troops devastated France’s most industrialized region in the north-east (Nord-Pas de Calais Mining Basin). Extensive looting took place as German forces removed whatever material they could use and destroyed the rest. Hundreds of mines were destroyed along with railways, bridges, and entire villages. Prime Minister of France Georges Clemenceau was determined, for these reasons, that any just peace required Germany to pay reparations for the damage it had caused. Clemenceau viewed reparations as a way of weakening Germany to ensure it could never threaten France again. Reparations would also go towards the reconstruction costs in other countries, including Belgium, which was also directly affected by the war.

Reparations

Avocourt, 1918, one of the many destroyed French villages where reconstruction would be funded by reparations.

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George opposed harsh reparations, arguing for a smaller sum that was less damaging to the German economy so that Germany could remain a viable economic power and trading partner. He also argued that reparations should include war pensions for disabled veterans and allowances for war widows, which would reserve a larger share of the reparations for the British Empire. Woodrow Wilson opposed these positions and was adamant that no indemnity should be imposed upon Germany.

The Paris Peace Conference opened on January 18, 1919, aiming to establish a lasting peace between the Allied and Central Powers. Demanding compensation from the defeated party was a common feature of peace treaties. However, the financial terms of treaties signed during the peace conference were labelled reparations to distinguish them from punitive settlements usually known as indemnities, intended for reconstruction and compensating families bereaved by the war. The opening article of the reparation section of the Treaty of Versailles, Article 231, served as a legal basis for the following articles, which obliged Germany to pay compensation and limited German responsibility to civilian damages. The same article, with the signatory’s name changed, was also included in the treaties signed by Germany’s allies.

Did Reparations Ruin the German Economy?

Erik Goldstein wrote that in 1921, the payment of reparations caused a crisis and that the occupation of the Ruhr had a disastrous effect on the German economy, resulting in the German Government printing more money as the currency collapsed. Hyperinflation began and printing presses worked overtime to print Reichsbank notes; by November 1923 one U.S. dollar was worth 4.2 trillion marks. Geoff Harcourt writes that Keynes’ arguments that reparations would lead to German economic collapse have been adopted “by historians of almost all political persuasions” and have influenced the way historians and the public “see the unfolding events in Germany and the decades between Versailles and the outbreak of the Second World War.”

But not all historians agree. According to Detlev Peukert, the financial problems that arose in the early 1920s were a result of post-war loans and the way Germany funded its war effort, not reparations. During World War I, Germany did not raise taxes or create new ones to pay for wartime expenses. Rather, loans were taken out, placing Germany in an economically precarious position as more money entered circulation, destroying the link between paper money and the gold reserve maintained before the war. With its defeat, Germany could not impose reparations and pay off war debts, which were now colossal.

Niall Ferguson partially supports this analysis. He says that had reparations not been imposed, Germany would still have had significant problems caused by the need to pay war debts and the demands of voters for more social services. Ferguson also says that these problems were aggravated by a trade deficit and a weak exchange rate for the mark during 1920. Afterwards, as the value of the mark rose, inflation became a problem. None of these effects, he says, were the result of reparations.

Several historians take the middle ground between condemning reparations and supporting the argument that they were not a complete burden upon Germany. Detlev Peukert states, “Reparations did not, in fact, bleed the German economy” as had been feared; however, the “psychological effects of reparations were extremely serious, as was the strain that the vicious circle of credits and reparations placed the international financial system.”

30.1.2: The Weimar Republic

In its 14 years in existence, the Weimar Republic faced numerous problems, including hyperinflation, political extremism, and contentious relationships with the victors of the First World War, leading to its collapse during the rise of Adolf Hitler.

Learning Objective

Describe the Weimar Republic and the challenges it faced

Key Points

- The Weimar Republic came into existence during the final stages of World War I, during the German Revolution of 1918–19.

- From its beginnings and throughout its 14 years of existence, the Weimar Republic experienced numerous problems, most notably hyperinflation and unemployment.

- In 1919, one loaf of bread cost 1 mark; by 1923, the same loaf of bread cost 100 billion marks.

- With its currency and economy in ruin, Germany failed to pay its heavy war reparations, which were resented by Germans to begin with.

- Many people in Germany blamed the Weimar Republic rather than their wartime leaders for the country’s defeat and for the humiliating terms of the Treaty of Versailles, a belief that came to be known as the “stab-in-the-back myth,” which was heavily propagated during the rise of the Nazi party.

- The passage of the Enabling Act of 1933 is widely considered to mark the end of the Weimar Republic and the beginning of the Nazi era.

Key Terms

- Stab-in-the-back myth

-

The notion, widely believed in right-wing circles in Germany after 1918, that the German Army did not lose World War I on the battlefield but was instead betrayed by the civilians on the home front, especially the republicans who overthrew the monarchy in the German Revolution of 1918–19. Advocates denounced the German government leaders who signed the Armistice on November 11, 1918, as the “November Criminals.” When the Nazis came to power in 1933, they made the legend an integral part of their official history of the 1920s, portraying the Weimar Republic as the work of the “November Criminals” who seized power while betraying the nation.

- Enabling Act of 1933

-

A 1933 Weimar Constitution amendment that gave the German Cabinet – in effect, Chancellor Adolf Hitler – the power to enact laws without the involvement of the Reichstag.

- hyperinflation

-

This occurs when a country experiences very high and usually accelerating rates of inflation, rapidly eroding the real value of the local currency and causing the population to minimize their holdings of local money by switching to relatively stable foreign currencies. Under such conditions, the general price level within an economy increases rapidly as the official currency loses real value.

Weimar Republic is an unofficial historical designation for the German state between 1919 and 1933. The name derives from the city of Weimar, where its constitutional assembly first took place. The official name of the state was still Deutsches Reich; it had remained unchanged since 1871. In English the country was usually known simply as Germany. A national assembly was convened in Weimar, where a new constitution for the Deutsches Reich was written and adopted on August 11, 1919. In its 14 years, the Weimar Republic faced numerous problems, including hyperinflation, political extremism (with paramilitaries – both left- and right-wing); and contentious relationships with the victors of the First World War. The people of Germany blamed the Weimar Republic rather than their wartime leaders for the country’s defeat and for the humiliating terms of the Treaty of Versailles. However, the Weimar Republic government successfully reformed the currency, unified tax policies, and organized the railway system. Weimar Germany eliminated most of the requirements of the Treaty of Versailles; it never completely met its disarmament requirements and eventually paid only a small portion of the war reparations (by twice restructuring its debt through the Dawes Plan and the Young Plan). Under the Locarno Treaties, Germany accepted the western borders of the republic, but continued to dispute the Eastern border.

From 1930 onward, President Hindenburg used emergency powers to back Chancellors Heinrich Brüning, Franz von Papen, and General Kurt von Schleicher. The Great Depression, exacerbated by Brüning’s policy of deflation, led to a surge in unemployment. In 1933, Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor with the Nazi Party as part of a coalition government. The Nazis held two out of the remaining 10 cabinet seats. Von Papen as Vice Chancellor was intended to work behind the scenes to keep Hitler under control, using his close personal connection to Hindenburg. Within months the Reichstag Fire Decree and the Enabling Act of 1933 brought about a state of emergency: it wiped out constitutional governance and civil liberties. Hitler’s seizure of power (Machtergreifung) brought the republic to an end. As democracy collapsed, a single-party state founded the Nazi era.

Challenges and Reasons for Failure

The reasons for the Weimar Republic’s collapse are the subject of continuing debate. It may have been doomed from the beginning since even moderates disliked it and extremists on both the left and right loathed it, a situation referred to by some historians, such as Igor Primoratz, as a “democracy without democrats.” Germany had limited democratic traditions, and Weimar democracy was widely seen as chaotic. Weimar politicians had been blamed for Germany’s defeat in World War I through a widely believed theory called the “Stab-in-the-back myth,” which contended that Germany’s surrender in World War I had been the unnecessary act of traitors, and thus the popular legitimacy of the government was on shaky ground. As normal parliamentary lawmaking broke down and was replaced around 1930 by a series of emergency decrees, the decreasing popular legitimacy of the government further drove voters to extremist parties.

The Republic in its early years was already under attack from both left- and right-wing sources. The radical left accused the ruling Social Democrats of betraying the ideals of the workers’ movement by preventing a communist revolution, and sought to overthrow the Republic and do so themselves. Various right-wing sources opposed any democratic system, preferring an authoritarian, autocratic state like the 1871 Empire. To further undermine the Republic’s credibility, some right-wingers (especially certain members of the former officer corps) also blamed an alleged conspiracy of Socialists and Jews for Germany’s defeat in World War I.

The Weimar Republic had some of the most serious economic problems ever experienced by any Western democracy in history. Rampant hyperinflation, massive unemployment, and a large drop in living standards were primary factors.

In the first half of 1922, the mark stabilized at about 320 marks per dollar. By fall 1922, Germany found itself unable to make reparations payments since the price of gold was now well beyond what it could afford. Also, the mark was by now practically worthless, making it impossible for Germany to buy foreign exchange or gold using paper marks. Instead, reparations were to be paid in goods such as coal. In January 1923, French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr, the industrial region of Germany in the Ruhr valley, to ensure reparations payments. Inflation was exacerbated when workers in the Ruhr went on a general strike and the German government printed more money to continue paying for their passive resistance. By November 1923, the US dollar was worth 4,2 trillion German marks. In 1919, one loaf of bread cost 1 mark; by 1923, the same loaf of bread cost 100 billion marks.

Hyperinflation in Weimar Republic

One-million mark notes used as notepaper, October 1923. In 1919, one loaf of bread cost 1 mark; by 1923, the same loaf of bread cost 100 billion marks.

From 1923 to 1929, there was a short period of economic recovery, but the Great Depression of the 1930s led to a worldwide recession. Germany was particularly affected because it depended heavily on American loans. In 1926, about 2 million Germans were unemployed, which rose to around 6 million in 1932. Many blamed the Weimar Republic. That was made apparent when political parties on both right and left wanting to disband the Republic altogether made any democratic majority in Parliament impossible.

The reparations damaged Germany’s economy by discouraging market loans, which forced the Weimar government to finance its deficit by printing more currency, causing rampant hyperinflation. In addition, the rapid disintegration of Germany in 1919 by the return of a disillusioned army, the rapid change from possible victory in 1918 to defeat in 1919, and the political chaos may have caused a psychological imprint on Germans that could lead to extreme nationalism, later epitomised and exploited by Hitler.

It is also widely believed that the 1919 constitution had several weaknesses, making the eventual establishment of a dictatorship likely, but it is unknown whether a different constitution could have prevented the rise of the Nazi party.

30.1.3: Self-Determination and New States

The dissolution of the German, Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman empires created a number of new countries in eastern Europe and the Middle East, often with large ethnic minorities. This caused numerous conflicts and hostilities.

Learning Objective

Give examples of self-determination in the interwar period

Key Points

- The self-determination of states, the principle that peoples, based on respect for the principle of equal rights and fair equality of opportunity, have the right to freely choose their sovereignty and international political status with no interference, developed throughout the modern period alongside nationalism.

- During and especially after World War I, there was a renewed commitment to self-determination and a major influx of new states formed out of the collapsed empires of Europe: the German Empire, Austro-Hungarian Empire, Russian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire.

- Many new states formed in Eastern Europe, some out of the 1918 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, where Russia renounced claims on Poland, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Belarus, Ukraine, and Lithuania, and some from the various treaties that came out of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919.

- These new countries tended to have substantial ethnic minorities who wished to unite with neighboring states where their ethnicity dominated (for example, example, Czechoslovakia had Germans, Poles, Ruthenians and Ukrainians, Slovaks, and Hungarians), which led to political instability and conflict.

- The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire became a pivotal milestone in the creation of the modern Middle East, the result of which bore witness to the creation of new conflicts and hostilities in the region.

Key Terms

- Nansen passport

-

Internationally recognized refugee travel documents, first issued by the League of Nations to stateless refugees.

- self-determination

-

A principle of international law that states that peoples, based on respect for the principle of equal rights and fair equality of opportunity, have the right to freely choose their sovereignty and international political status with no interference.

- Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

-

A peace treaty signed on March 3, 1918, between the new Bolshevik government of Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russia’s participation in World War I. Part of its terms was the renouncement of Russia’s claims on Poland, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Belarus, Ukraine, and Lithuania.

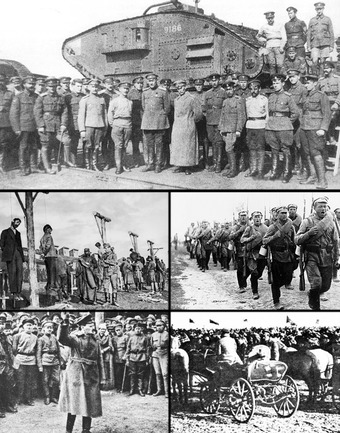

Geopolitical Consequences of World War I

The years 1919-24 were marked by turmoil as Europe struggled to recover from the devastation of the First World War and the destabilizing effects of the loss of four large historic empires: the German Empire, Austro-Hungarian Empire, Russian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire. There were numerous new nations in Eastern Europe, most of them small.

Internally these new countries tended to have substantial ethnic minorities who wished to unite with neighboring states where their ethnicity dominated. For example, Czechoslovakia had Germans, Poles, Ruthenians and Ukrainians, Slovaks, and Hungarians. Millions of Germans found themselves in the newly created countries as minorities. More than two million ethnic Hungarians found themselves living outside of Hungary in Slovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia. Many of these national minorities found themselves in bad situations because the modern governments were intent on defining the national character of the countries, often at the expense of the minorities. The League of Nations sponsored various Minority Treaties in an attempt to deal with the problem, but with the decline of the League in the 1930s, these treaties became increasingly unenforceable. One consequence of the massive redrawing of borders and the political changes in the aftermath of World War I was the large number of European refugees. These and the refugees of the Russian Civil War led to the creation of the Nansen passport.

Ethnic minorities made the location of the frontiers generally unstable. Where the frontiers have remained unchanged since 1918, there has often been the expulsion of an ethnic group, such as the Sudeten Germans. Economic and military cooperation among these small states was minimal, ensuring that the defeated powers of Germany and the Soviet Union retained a latent capacity to dominate the region. In the immediate aftermath of the war, defeat drove cooperation between Germany and the Soviet Union but ultimately these two powers would compete to dominate eastern Europe.

At the end of the war, the Allies occupied Constantinople (Istanbul) and the Ottoman government collapsed. The Treaty of Sèvres, a plan designed by the Allies to dismember the remaining Ottoman territories, was signed on August 10, 1920, although it was never ratified by the Sultan.

The occupation of Smyrna by Greece on May 18, 1919, triggered a nationalist movement to rescind the terms of the treaty. Turkish revolutionaries led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, a successful Ottoman commander, rejected the terms enforced at Sèvres and under the guise of General Inspector of the Ottoman Army, left Istanbul for Samsun to organize the remaining Ottoman forces to resist the terms of the treaty.

After Turkish resistance gained control over Anatolia and Istanbul, the Sèvres treaty was superseded by the Treaty of Lausanne, which formally ended all hostilities and led to the creation of the modern Turkish Republic. As a result, Turkey became the only power of World War I to overturn the terms of its defeat and negotiate with the Allies as an equal.

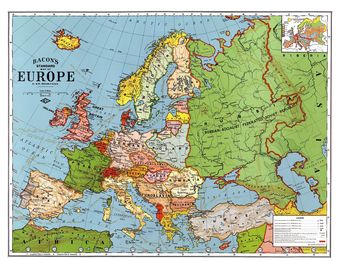

Europe in 1923

The dissolution of the German, Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman empires created a number of new countries in eastern Europe, such as Poland, Finland, Yugoslavia, and Turkey.

Self-Determination

The right of peoples to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law. It states that peoples, based on respect for the principle of equal rights and fair equality of opportunity, have the right to freely choose their sovereignty and international political status with no interference. The explicit terms of this principle can be traced to the Atlantic Charter, signed on August 14, 1941, by Franklin D. Roosevelt, President of the United States of America, and Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. It also is derived from principles espoused by United States President Woodrow Wilson following World War I, after which some new nation states were formed or previous states revived after the dissolution of empires. The principle does not state how the decision is to be made nor what the outcome should be, whether it be independence, federation, protection, some form of autonomy, or full assimilation. Neither does it state what the delimitation between peoples should be—nor what constitutes a people. There are conflicting definitions and legal criteria for determining which groups may legitimately claim the right to self-determination.

The employment of imperialism through the expansion of empires and the concept of political sovereignty, as developed after the Treaty of Westphalia, also explain the emergence of self-determination during the modern era. During and after the Industrial Revolution, many groups of people recognized their shared history, geography, language, and customs. Nationalism emerged as a uniting ideology not only between competing powers, but also for groups that felt subordinated or disenfranchised inside larger states; in this situation, self-determination can be seen as a reaction to imperialism. Such groups often pursued independence and sovereignty over territory, but sometimes a different sense of autonomy has been pursued or achieved.

The revolt of New World British colonists in North America during the mid-1770s has been seen as the first assertion of the right of national and democratic self-determination because of the explicit invocation of natural law, the natural rights of man, and the consent of and sovereignty by, the people governed; these ideas were inspired particularly by John Locke’s enlightened writings of the previous century. Thomas Jefferson further promoted the notion that the will of the people was supreme, especially through authorship of the United States Declaration of Independence which inspired Europeans throughout the 19th century. Leading up to World War I, in Europe there was a rise of nationalism, with nations such as Greece, Hungary, Poland, and Bulgaria seeking or winning their independence.

Woodrow Wilson revived America’s commitment to self-determination, at least for European states, during World War I. When the Bolsheviks came to power in Russia in November 1917, they called for Russia’s immediate withdrawal as a member of the Allies of World War I. They also supported the right of all nations, including colonies, to self-determination. The 1918 Constitution of the Soviet Union acknowledged the right of secession for its constituent republics.

This presented a challenge to Wilson’s more limited demands. In January 1918 Wilson issued his Fourteen Points that among other things, called for adjustment of colonial claims insofar as the interests of colonial powers had equal weight with the claims of subject peoples. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918 led to Russia’s exit from the war and the independence of Armenia, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Ukraine, Lithuania, Georgia, and Poland.

The end of the war led to the dissolution of the defeated Austro-Hungarian Empire and the creation by the Allies of Czechoslovakia and the union of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs and the Kingdom of Serbia as new states. However, this imposition of states where some nationalities (especially Poles, Czechs, and Serbs and Romanians) were given power over nationalities who disliked and distrusted them eventually helped lead to World War II. Also Germany lost land after WWI: Northern Slesvig voted to return to Denmark after a referendum. The defeated Ottoman empire was dissolved into the Republic of Turkey and several smaller nations, including Yemen, plus the new Middle East Allied “mandates” of Syria and Lebanon (future Syria, Lebanon and Hatay State), Palestine (future Transjordan and Israel), Mesopotamia (future Iraq). The League of Nations was proposed as much as a means of consolidating these new states, as a path to peace.

During the 1920s and 1930s there were some successful movements for self-determination in the beginnings of the process of decolonization. In the Statute of Westminster the United Kingdom granted independence to Canada, New Zealand, Newfoundland, the Irish Free State, the Commonwealth of Australia, and the Union of South Africa after the British parliament declared itself as incapable of passing laws over them without their consent. Egypt, Afghanistan, and Iraq also achieved independence from Britain and Lebanon from France. Other efforts were unsuccessful, like the Indian independence movement. Italy, Japan, and Germany all initiated new efforts to bring certain territories under their control, leading to World War II.

30.1.4: The Kellogg-Briand Pact

The Kellogg-Briand Pact intended to establish “the renunciation of war as an instrument of national policy,” but was largely ineffective in preventing conflict or war.

Learning Objective

Identify why the Kellogg-Briand Pact was concieved and signed

Key Points

- After World War I, seeing the devastating consequences of total war, many politicians and diplomats strove to created measures that would prevent further armed conflict.

- This effort resulted in numerous international institutions and treaties, such as the creation of the League of Nations and in 1928, the Kellogg-Briand Pact.

- The Kellogg-Briand Pact was written by United States Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg and French foreign minister Aristide Briand.

- It went into effect on July 24, 1929, and before long had a total of 62 signatories.

- Practically, the Kellogg-Briand Pact did not live up to its aim of ending war or stopping the rise of militarism, and in this sense it made no immediate contribution to international peace and proved to be ineffective in the years to come.

- Nevertheless, the pact has served as one of the legal bases establishing the international norms that the threat or use of military force in contravention of international law, as well as the territorial acquisitions resulting from it, are unlawful.

- It inspired and influenced future international agreements, including the United Nations Charter.

Key Terms

- annexation

-

The political transition of land from the control of one entity to another. It is also the incorporation of unclaimed land into a state’s sovereignty, which is in most cases legitimate. In international law it is the forcible transition of one state’s territory by another state or the legal process by which a city acquires land. Usually, it is implied that the territory and population being annexed is the smaller, more peripheral, and weaker of the two merging entities, barring physical size.

- multilateral treaty

-

A treaty to which three or more sovereign states are parties. Each party owes the same obligations to all other parties, except to the extent that they have stated reservations.

- Kellogg–Briand Pact

-

A 1928 international agreement in which signatory states promised not to use war to resolve “disputes or conflicts of whatever nature or of whatever origin they may be, which may arise among them.”

The Kellogg–Briand Pact (or Pact of Paris, officially General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy) is a 1928 international agreement in which signatory states promised not to use war to resolve “disputes or conflicts of whatever nature or of whatever origin they may be, which may arise among them.” Parties failing to abide by this promise “should be denied of the benefits furnished by this treaty.” It was signed by Germany, France, and the United States on August 27, 1928, and by most other nations soon after. Sponsored by France and the U.S., the Pact renounces the use of war and calls for the peaceful settlement of disputes. Similar provisions were incorporated into the Charter of the United Nations and other treaties and it became a stepping-stone to a more activist American policy. It is named after its authors, United States Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg and French foreign minister Aristide Briand.

The texts of the treaty reads:

Persuaded that the time has come when a frank renunciation of war as an instrument of national

policy should be made to the end that the peaceful and friendly relations now existing betweentheir peoples may be perpetuated; Convinced that all changes in their relations with one another should be sought only by

pacific means and be the result of a peaceful and orderly process, and that any signatory Power which shall hereafter seek to promote its national interests by resort to war should be denied the

benefits furnished by this Treaty;Hopeful that, encouraged by their example, all the other nations of the world will join in this

humane endeavour and by adhering to the present Treaty as soon as it comes into force bring their

peoples within the scope of its beneficient provisions, thus uniting the civilized nations of the

world in a common renunciation of war as an instrument of their national policy;Have decided to conclude a Treaty…

After negotiations, the pact was signed in Paris at the French Foreign Ministry by the representatives from Australia, Belgium, Canada, Czechoslovakia, France, Germany, British India, the Irish Free State, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Poland, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It was provided that it would come into effect on July 24, 1929. By that date, the following nations had deposited instruments of definitive adherence to the pact: Afghanistan, Albania, Austria, Bulgaria, China, Cuba, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Egypt, Estonia, Ethiopia, Finland, Guatemala, Hungary, Iceland, Latvia, Liberia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Nicaragua, Norway, Panama, Peru, Portugal, Romania, the Soviet Union, the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, Siam, Spain, Sweden, and Turkey. Eight further states joined after that date (Persia, Greece, Honduras, Chile, Luxembourg, Danzig, Costa Rica and Venezuela) for a total of 62 signatories.

In the United States, the Senate approved the treaty overwhelmingly, 85–1, with only Wisconsin Republican John J. Blaine voting against. While the U.S. Senate did not add any reservation to the treaty, it did pass a measure which interpreted the treaty as not infringing upon the United States’ right of self-defense and not obliging the nation to enforce it by taking action against those who violated it.

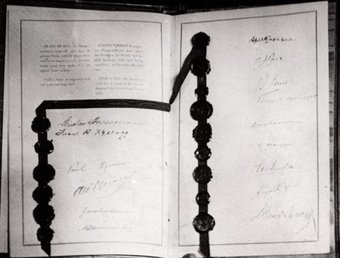

Kellogg–Briand Pact

Effect and Legacy

As a practical matter, the Kellogg–Briand Pact did not live up to its aim of ending war or stopping the rise of militarism, and in this sense it made no immediate contribution to international peace and proved to be ineffective in the years to come. Moreover, the pact erased the legal distinction between war and peace because the signatories, having renounced the use of war, began to wage wars without declaring them as in the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, the Italian invasion of Abyssinia in 1935, the Spanish Civil War in 1936, the Soviet invasion of Finland in 1939, and the German and Soviet Union invasions of Poland. Nevertheless, the pact is an important multilateral treaty because, in addition to binding the particular nations that signed it, it has also served as one of the legal bases establishing the international norms that the threat or use of military force in contravention of international law, as well as the territorial acquisitions resulting from it, are unlawful.

Notably, the pact served as the legal basis for the creation of the notion of crime against peace. It was for committing this crime that the Nuremberg Tribunal and Tokyo Tribunal tried and sentenced a number of people responsible for starting World War II.

The interdiction of aggressive war was confirmed and broadened by the United Nations Charter, which provides in article 2, paragraph 4, that “All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.” One legal consequence of this is that it is clearly unlawful to annex territory by force. However, neither this nor the original treaty has prevented the subsequent use of annexation. More broadly, there is a strong presumption against the legality of using or threatening military force against another country. Nations that have resorted to the use of force since the Charter came into effect have typically invoked self-defense or the right of collective defense.

30.2: The Russian Revolution

30.2.1: The Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905 was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire, which included worker strikes, peasant unrest, and military mutinies.

Learning Objective

Outline the events of the 1905 Revolution, along with its successes and failures

Key Points

- In January 1905, an incident known as “Bloody Sunday” occurred when Father Gapon led an enormous crowd to the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg to present a petition to the tsar.

- When the procession reached the palace, Cossacks opened fire on the crowd, killing hundreds.

- The Russian masses were so aroused over the massacre that a general strike was declared demanding a democratic republic, which marked the beginning of the Russian Revolution of 1905.

- Soviets (councils of workers) appeared in most cities to direct revolutionary activity.

- In October 1905, Tsar Nicholas reluctantly issued the famous October Manifesto, which conceded the creation of a national Duma (legislature), as well as the right to vote, and affirmed that no law was to go into force without confirmation by the Duma.

- The moderate groups were satisfied, but the socialists rejected the concessions as insufficient and tried to organize new strikes.

- By the end of 1905, there was disunity among the reformers, and the tsar’s position was strengthened for the time being.

Key Terms

- Russification

-

A form of cultural assimilation during which non-Russian communities, voluntarily or not, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian one. In a historical sense, the term refers to both official and unofficial policies of Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union with respect to their national constituents and to national minorities in Russia, aimed at Russian domination.

- State Duma

-

The Lower House of the legislative assembly in the late Russian Empire, which held its meetings in the Taurida Palace in St. Petersburg. It convened four times between April 1906 and the collapse of the Empire in February 1917. It was founded during the Russian Revolution of 1905 as the Tsar’s response to rebellion.

- Russian Constitution of 1906

-

A major revision of the 1832 Fundamental Laws of the Russian Empire, which transformed the formerly absolutist state into one in which the emperor agreed for the first time to share his autocratic power with a parliament. It was enacted on May 6, 1906, on the eve of the opening of the first State Duma.

The Russian Revolution of 1905 was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire, some of which was directed at the government. It included worker strikes, peasant unrest, and military mutinies and led to constitutional reform, including the establishment of the State Duma, the multi-party system, and the Russian Constitution of 1906.

Causes of Unrest

According to Sidney Harcave, author of The Russian Revolution of 1905, four problems in Russian society contributed to the revolution. First, newly emancipated peasants earned too little and were not allowed to sell or mortgage their allotted land. Second, ethnic minorities resented the government because of its “Russification,” discrimination, and repression, both social and formal, such as banning them from voting and serving in the Guard or Navy and limiting attendance in schools. Third, a nascent industrial working class resented the government for doing too little to protect them, by banning strikes and labor unions. Finally, the educated class fomented and spread radical ideas after a relaxing of discipline in universities allowed a new consciousness to grow among students.

Taken individually, these issues might not have affected the course of Russian history, but together they created the conditions for a potential revolution. Historian James Defronzo writes, “At the turn of the century, discontent with the Tsar’s dictatorship was manifested not only through the growth of political parties dedicated to the overthrow of the monarchy but also through industrial strikes for better wages and working conditions, protests and riots among peasants, university demonstrations, and the assassination of government officials, often done by Socialist Revolutionaries.”

Start of the Revolution

In December 1904, a strike occurred at the Putilov plant (a railway and artillery supplier) in St. Petersburg. Sympathy strikes in other parts of the city raised the number of strikers to 150,000 workers in 382 factories. By January 21, 1905, the city had no electricity and newspaper distribution was halted. All public areas were declared closed.

Controversial Orthodox priest Georgy Gapon, who headed a police-sponsored workers’ association, led a huge workers’ procession to the Winter Palace to deliver a petition to the Tsar on Sunday, January 22, 1905. The troops guarding the palace were ordered to tell the demonstrators not to pass a certain point, according to Sergei Witte, and at some point, troops opened fire on the demonstrators, causing between 200 and 1,000 deaths. The event became known as Bloody Sunday and is considered by many scholars as the start of the active phase of the revolution.

The events in St. Petersburg provoked public indignation and a series of massive strikes that spread quickly throughout the industrial centers of the Russian Empire. Polish socialists called for a general strike. By the end of January 1905, over 400,000 workers in Russian Poland were on strike. Half of European Russia’s industrial workers went on strike in 1905, and 93.2% in Poland. There were also strikes in Finland and the Baltic coast.

Nationalist groups were angered by the Russification undertaken since Alexander II. The Poles, Finns, and Baltic provinces all sought autonomy and freedom to use their national languages and promote their own cultures. Muslim groups were also active — the First Congress of the Muslim Union took place in August 1905. Certain groups took the opportunity to settle differences with each other rather than the government. Some nationalists undertook anti-Jewish pogroms, possibly with government aid, and in total over 3,000 Jews were killed.

Height of the Revolution

Tsar Nicholas II agreed on February 18 to the creation of a State Duma of the Russian Empire with consultative powers only. When its slight powers and limits on the electorate were revealed, unrest redoubled. The Saint Petersburg Soviet was formed and called for a general strike in October, refusal to pay taxes, and the withdrawal of bank deposits.

In June and July 1905, there were many peasant uprisings in which peasants seized land and tools. Disturbances in the Russian-controlled Congress Poland culminated in June 1905 in the Łódź insurrection. Surprisingly, only one landlord was recorded as killed. Far more violence was inflicted on peasants outside the commune with 50 deaths recorded.

The October Manifesto, written by Sergei Witte and Alexis Obolenskii, was presented to the Tsar on October 14. It closely followed the demands of the Zemstvo Congress in September, granting basic civil rights, allowing the formation of political parties, extending the franchise towards universal suffrage, and establishing the Duma as the central legislative body. The Tsar waited and argued for three days, but finally signed the manifesto on October 30, 1905, citing his desire to avoid a massacre and his realization that insufficient military force was available to pursue alternate options. He regretted signing the document, saying that he felt “sick with shame at this betrayal of the dynasty … the betrayal was complete.”

When the manifesto was proclaimed, there were spontaneous demonstrations of support in all the major cities. The strikes in St. Petersburg and elsewhere officially ended or quickly collapsed. A political amnesty was also offered. The concessions came hand-in-hand with renewed, brutal action against the unrest. There was also a backlash from the conservative elements of society, with right-wing attacks on strikers, left-wingers, and Jews.

While the Russian liberals were satisfied by the October Manifesto and prepared for upcoming Duma elections, radical socialists and revolutionaries denounced the elections and called for an armed uprising to destroy the Empire.

Some of the November uprising of 1905 in Sevastopol, headed by retired naval Lieutenant Pyotr Schmidt, was directed against the government, while some was undirected. It included terrorism, worker strikes, peasant unrest, and military mutinies, and was only suppressed after a fierce battle. The Trans-Baikal railroad fell into the hands of striker committees and demobilized soldiers returning from Manchuria after the Russo–Japanese War. The Tsar had to send a special detachment of loyal troops along the Trans-Siberian Railway to restore order.

Between December 5 and 7, there was another general strike by Russian workers. The government sent troops on December 7, and a bitter street-by-street fight began. A week later, the Semyonovsky Regiment was deployed and used artillery to break up demonstrations and shell workers’ districts. On December 18, with around a thousand people dead and parts of the city in ruins, the workers surrendered. After a final spasm in Moscow, the uprisings ended.

Russian Revolution of 1905

A locomotive overturned by striking workers at the main railway depot in Tiflis in 1905.

Results

According to figures presented in the Duma by Professor Maksim Kovalevsky, by April 1906, more than 14,000 people had been executed and 75,000 imprisoned.

Following the Revolution of 1905, the Tsar made last attempts to save his regime and offered reforms similar to those of most rulers pressured by a revolutionary movement. The military remained loyal throughout the Revolution of 1905, as shown by their shooting of revolutionaries when ordered by the Tsar, making overthrow difficult. These reforms were outlined in a precursor to the Constitution of 1906 known as the October Manifesto which created the Imperial Duma. The Russian Constitution of 1906, also known as the Fundamental Laws, set up a multiparty system and a limited constitutional monarchy. The revolutionaries were quelled and satisfied with the reforms, but it was not enough to prevent the 1917 revolution that would later topple the Tsar’s regime.

30.2.2: Rising Discontent in Russia

Under Tsar Nicholas II (reigned 1894–1917), the Russian Empire slowly industrialized amidst increased discontent and dissent among the lower classes. This only increased during World War I, leading to the utter collapse of the Tsarist régime in 1917 and an era of civil war.

Learning Objective

Name a few reasons the Russian populace was discontented with its leadership

Key Points

- During the 1890s, Russia’s industrial development led to a large increase in the size of the urban middle-class and working class, which gave rise to a more dynamic political atmosphere and the development of radical parties.

- During the 1890s and early 1900s, bad living and working conditions, high taxes, and land hunger gave rise to more frequent strikes and agrarian disorders.

- Russia’s backwards systems for agricultural production, the worst in Europe at the time, influenced the attitudes of peasants and other social groups to reform against the government and promote social changes.

- The Russian Revolution of 1905 was a major factor of the February Revolutions of 1917, unleashing a steady current of worker unrest and increased political agitation.

- The onset of World War I exposed the weakness of Nicholas II’s government.

- A show of national unity had accompanied Russia’s entrance into the war, with defense of the Slavic Serbs the main battle cry, but by 1915, the strain of the war began to cause popular unrest, with high food prices and fuel shortages causing strikes in some cities.

Key Terms

- Tsar Nicholas II

-

The last Emperor of Russia, ruling from November 1894 until his forced abdication on March 15, 1917. His reign saw the fall of the Russian Empire from one of the foremost great powers of the world to economic and military collapse. Due to the Khodynka Tragedy, anti-Semitic pogroms, Bloody Sunday, the violent suppression of the 1905 Revolution, the execution of political opponents, and his perceived responsibility for the Russo-Japanese War, he was given the nickname Nicholas the Bloody by his political adversaries.

- St. Petersburg Soviet

-

A workers’ council or soviet circa 1905. The idea of a soviet as an organ to coordinate workers’ strike activities arose during the January–February 1905 meetings of workers at the apartment of Voline (later a famous anarchist) during the abortive revolution of 1905. However, its activities were quickly repressed by the government. The model would later become central to the communists during the Revolution of 1917.

- Bolshevik party

-

Literally meaning “one of the majority,” this party was a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split from the Menshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. They ultimately became the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Under Tsar Nicholas II (reigned 1894–1917), the Russian Empire slowly industrialized while repressing political opposition in the center and on the far left. It recklessly entered wars with Japan (1904) and with Germany and Austria (1914) for which it was very poorly prepared, leading to the utter collapse of the old régime in 1917 and an era of civil war.

During the 1890s, Russia’s industrial development led to a large increase in the size of the urban middle-class and orking class, which gave rise to a more dynamic political atmosphere and the development of radical parties. Because the state and foreigners owned much of Russia’s industry, the Russian working class was comparatively stronger and the Russian bourgeoisie comparatively weaker than in the West. The working class and peasants became the first to establish political parties in Russia because the nobility and the wealthy bourgeoisie were politically timid. During the 1890s and early 1900s, bad living and working conditions, high taxes, and land hunger gave rise to more frequent strikes and agrarian disorders. These activities prompted the bourgeoisie of various nationalities in the Russian Empire to develop a host of parties, both liberal and conservative.

The Russian Revolution of 1905 was a major factor in the February Revolutions of 1917. The events of Bloody Sunday triggered a line of protests. A council of workers called the St. Petersburg Soviet was created in all this chaos, beginning the era of communist political protest.

Agrarian Backwardness

Russia’s systems for agricultural production influenced peasants and other social groups to reform against the government and promote social changes. Historians George Jackson and Robert Devlin write, “At the beginning of the twentieth century, agriculture constituted the single largest sector of the Russian economy, producing approximately one-half of the national income and employing two-thirds of Russia’s population.” This illustrates the tremendous role peasants played economically, making them detrimental to the revolutionary ideology of the populist and social democrats. At the end of the 19th century, Russian agriculture as a whole was the worst in Europe. The Russian system of agriculture lacked capital investment and technological advancement. Livestock productivity was notoriously backwards and the lack of grazing land such as meadows forced livestock to graze in fallow uncultivated land. Both the crop and livestock system failed to withstand the Russian winters. During the Tsarist rule, the agricultural economy diverged from subsistence production to production directly for the market. Along with the agricultural failures, Russia had rapid population growth, railroads expanded across farmland, and inflation attacked the price of commodities. Restrictions were placed on the distribution of food and ultimately led to famines. Agricultural difficulties in Russia limited the economy, influencing social reforms and assisting the rise of the Bolshevik party.

Worker Discontent

The social causes of the Russian Revolution mainly came from centuries of oppression of the lower classes by the Tsarist regime and Nicholas’s failures in World War I. While rural agrarian peasants had been emancipated from serfdom in 1861, they still resented paying redemption payments to the state, and demanded communal tender of the land they worked. The problem was further compounded by the failure of Sergei Witte’s land reforms of the early 20th century. Increasing peasant disturbances and sometimes actual revolts occurred, with the goal of securing ownership of the land they worked. Russia consisted mainly of poor farming peasants, with 1.5% of the population owning 25% of the land.

Workers had good reasons for discontent: overcrowded housing with often deplorable sanitary conditions; long hours at work (on the eve of the war, a 10-hour workday six days a week was the average and many were working 11–12 hours a day by 1916); constant risk of injury and death from poor safety and sanitary conditions; harsh discipline (not only rules and fines, but foremen’s fists); and inadequate wages (made worse after 1914 by steep wartime increases in the cost of living). At the same time, urban industrial life was full of benefits, though these could be just as dangerous, from the point of view of social and political stability, as the hardships. There were many encouragements to expect more from life. Acquiring new skills gave many workers a sense of self-respect and confidence, heightening expectations and desires. Living in cities, workers encountered material goods they had never seen in villages. Most importantly, they were exposed to new ideas about the social and political order.

The rapid industrialization of Russia also resulted in urban overcrowding. Between 1890 and 1910, the population of the capital, Saint Petersburg, swelled from 1,033,600 to 1,905,600, with Moscow experiencing similar growth. This created a new proletariat that due to being crowded together in the cities was much more likely to protest and go on strike than the peasantry had been in previous eras. In one 1904 survey, it was found that an average of sixteen people shared each apartment in Saint Petersburg with six people per room. There was no running water, and piles of human waste were a threat to the health of the workers. The poor conditions only aggravated the situation, with the number of strikes and incidents of public disorder rapidly increasing in the years shortly before World War I. Because of late industrialization, Russia’s workers were highly concentrated.

World War I

Tsar Nicholas II and his subjects entered World War I with enthusiasm and patriotism, with the defense of Russia’s fellow Orthodox Slavs, the Serbs, as the main battle cry. In August 1914, the Russian army invaded Germany’s province of East Prussia and occupied a significant portion of Austrian-controlled Galicia in support of the Serbs and their allies – the French and British. Military reversals and shortages among the civilian population, however, soon soured much of the population. German control of the Baltic Sea and German-Ottoman control of the Black Sea severed Russia from most of its foreign supplies and potential markets.

By the middle of 1915, the impact of the war was demoralizing. Food and fuel were in short supply, casualties were increasing, and inflation was mounting. Strikes rose among low-paid factory workers, and there were reports that peasants, who wanted reforms of land ownership, were restless. The tsar eventually decided to take personal command of the army and moved to the front, leaving Alexandra in charge in the capital.

By its end, World War I prompted a Russian outcry directed at Tsar Nicholas II. It was another major factor contributing to the retaliation of the Russian Communists against their royal opponents. After the entry of the Ottoman Empire on the side of the Central Powers in October 1914, Russia was deprived of a major trade route through Ottoman Empire, which followed with a minor economic crisis in which Russia became incapable of providing munitions to its army in the years leading to 1917. However, the problems were merely administrative and not industrial, as Germany was producing great amounts of munitions whilst constantly fighting on two major battlefronts.

The war also developed a weariness in the city, owing to a lack of food in response to the disruption of agriculture. Food scarcity had become a considerable problem in Russia, but the cause did not lie in any failure of the harvests, which had not been significantly altered during wartime. The indirect reason was that the government, in order to finance the war, had been printing millions of ruble notes, and by 1917 inflation increased prices up to four times what they had been in 1914. The peasantry were consequently faced with the higher cost of purchases, but made no corresponding gain in the sale of their own produce, since this was largely taken by the middlemen on whom they depended. As a result, they tended to hoard their grain and to revert to subsistence farming, so the cities were constantly short of food. At the same time rising prices led to demands for higher wages in the factories, and in January and February 1916 revolutionary propaganda aided by German funds led to widespread strikes. Heavy losses during the war also strengthened thoughts that Tsar Nicholas II was unfit to rule.

Discontent Leading up the Russian Revolution

Russian soldiers marching in Petrograd in February 1917.

30.2.3: The Provisional Government

The Russian Empire collapsed with the abdication of Emperor Nicholas II during the February Revolution. The old regime was replaced by a politically moderate provisional government that struggled for power with the socialist-led worker councils (soviets).

Learning Objective

Detail the workings of Russia’s provisional government

Key Points

- The February Revolution of 1917 was focused around Petrograd (now Saint Petersburg), then capital of Russia.

- The army leadership felt they did not have the means to suppress the revolution, resulting in Tsar Nicholas’s abdication and soon after, the end of the Tsarist regime altogether.

- To fill the vacuum of authority, the Duma (legislature) declared a provisional government headed by Prince Lvov, collectively known as the Russian Republic.

- Meanwhile, the socialists in Petrograd organized elections among workers and soldiers to form a soviet (council) of workers’ and soldiers’ deputies as an organ of popular power that could pressure the “bourgeois” provisional government.

- The Soviets initially permitted the provisional government to rule, but insisted on a prerogative to influence decisions and control various militias.

- A period of dual power ensued during which the provisional government held state power while the national network of soviets, led by socialists, had the allegiance of the lower classes and the political left.

- During this chaotic period there were frequent mutinies, protests, and strikes, such as the July Days.

- The period of competition for authority ended in late October 1917 when Bolsheviks routed the ministers of the Provisional Government in the events known as the October Revolution and placed power in the hands of the soviets, which had given their support to the Bolsheviks.

Key Terms

- July Days

-

Events in 1917 that took place in Petrograd, Russia, between July 3 and 7 when soldiers and industrial workers engaged in spontaneous armed demonstrations against the Russian Provisional Government. The Bolsheviks initially attempted to prevent the demonstrations and then decided to support them.

- Soviet

-

Political organizations and governmental bodies, essentially workers’ councils, primarily associated with the Russian Revolutions and the history of the Soviet Union, that gave the name to the latter state.

- February Revolution

-

The first of two Russian revolutions in 1917. It involved mass demonstrations and armed clashes with police and gendarmes, the last loyal forces of the Russian monarchy. On March 12, mutinous Russian Army forces sided with the revolutionaries. Three days later, the result was the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, the end of the Romanov dynasty, and the end of the Russian Empire.

- Russian Provisional Government

-

A provisional government of the Russian Republic established immediately following the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II of the Russian Empire on 2 March.

Background: February Revolution

At the beginning of February 1917, Petrograd (Saint Petersburg) workers began several strikes and demonstrations. On March 7, workers at Putilov, Petrograd’s largest industrial plant, announced a strike.

The next day, a series of meetings and rallies were held for International Women’s Day, which gradually turned into economic and political gatherings. Demonstrations were organized to demand bread, supported by the industrial working force who considered them a reason to continue the strikes. The women workers marched to nearby factories, bringing out over 50,000 workers on strike. By March 10, virtually every industrial enterprise in Petrograd had been shut down along with many commercial and service enterprises. Students, white-collar workers, and teachers joined the workers in the streets and at public meetings.

To quell the riots, the Tsar looked to the army. At least 180,000 troops were available in the capital, but most were either untrained or injured. Historian Ian Beckett suggests around 12,000 could be regarded as reliable, but even these proved reluctant to move in on the crowd since it included so many women. For this reason, on March 11 when the Tsar ordered the army to suppress the rioting by force, troops began to mutiny. Although few actively joined the rioting, many officers were either shot or went into hiding; the ability of the garrison to hold back the protests was all but nullified, symbols of the Tsarist regime were rapidly torn down, and governmental authority in the capital collapsed – not helped by the fact that Nicholas had suspended the Duma (legislature) that morning, leaving it with no legal authority to act. The response of the Duma, urged on by the liberal bloc, was to establish a temporary committee to restore law and order; meanwhile, the socialist parties established the Petrograd Soviet to represent workers and soldiers. The remaining loyal units switched allegiance the next day.

The Tsar directed the royal train, stopped on March 14 by a group of revolutionaries at Malaya Vishera, back to Petrograd. When the Tsar finally arrived at in Pskov, the Army Chief Ruzsky and the Duma deputees Guchkov and Shulgin suggested in unison that he abdicate the throne. He did so on March on behalf of both himself and his son, the Tsarevich. Nicholas nominated his brother, the Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich, to succeed him, but the Grand Duke realized that he would have little support as ruler. He declined the crown on March 16, stating that he would take it only as the consensus of democratic action.

The immediate effect of the February Revolution was a widespread atmosphere of elation and excitement in Petrograd. On March 16, the provisional government was announced. The center-left was well represented, and the government was initially chaired by a liberal aristocrat, Prince Georgy Yevgenievich Lvov, a member of the Constitutional Democratic party (KD). The socialists had formed their rival body, the Petrograd Soviet (or workers’ council) four days earlier. The Petrograd Soviet and the provisional government competed for power over Russia.

Reign of the Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government was a provisional government of the Russian Republic established immediately following the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II of the Russian Empire on March 2, 1917. It was intended to organize elections to the Russian Constituent Assembly and its convention.

Despite its short reign of power and implementation shortcomings, the provisional government passed very progressive legislation. The policies enacted by this moderate government (by 1917 Russian standards) represented arguably the most liberal legislation in Europe at the time. It abolished capital punishment, declared the independence of Poland, redistributed wealth in the countryside, restored the constitution of Finland, established local government on a universal suffrage basis, separated church and state, conceded language rights to all the nationalities, and confirmed liberty of speech, liberty of the Press, and liberty of assembly.

The provisional government lasted approximately eight months, ceasing when the Bolsheviks seized power after the October Revolution in October 1917. According to Harold Whitmore Williams, the eight months during which Russia was ruled by the provisional government was characterized by the steady and systematic disorganization of the army.

The provisional government was unable to make decisive policy decisions due to political factionalism and a breakdown of state structures. This weakness left the government open to strong challenges from both the right and the left. Its chief adversary on the left was the Petrograd Soviet, which tentatively cooperated with the government at first but then gradually gained control of the army, factories, and railways. While the Provisional Government retained the formal authority to rule over Russia, the Petrograd Soviet maintained actual power. With its control over the army and the railroads, the Petrograd Soviet had the means to enforce policies. The provisional government lacked the ability to administer its policies. In fact, local soviets, political organizations mostly of socialists, often maintained discretion when deciding whether or not to implement the provisional government’s laws.

A period of dual power ensued during which the provisional government held state power while the national network of soviets, led by socialists, had the allegiance of the lower classes and the political left. During this chaotic period there were frequent mutinies, protests, and strikes. When the provisional government chose to continue fighting the war with Germany, the Bolsheviks and other socialist factions campaigned for stopping the conflict. The Bolsheviks turned workers’ militias under their control into the Red Guards (later the Red Army), over which they exerted substantial control.

In July, following a series of crises known as the July Days (strikes by soldiers and industrial workers) that undermined its authority with the public, the head of the provisional government resigned and was succeeded by Alexander Kerensky. Kerensky was more progressive than his predecessor but not radical enough for the Bolsheviks or many Russians discontented with the deepening economic crisis and the continuation of the war. While Kerensky’s government marked time, the socialist-led soviet in Petrograd joined with soviets (workers’ councils) that formed throughout the country to create a national movement.

The period of competition for authority ended in late October 1917 when Bolsheviks routed the ministers of the provisional government in the events known as the October Revolution and placed power in the hands of the soviets, which had given their support to the Bolsheviks.

July Days

Street demonstration on Nevsky Prospekt in Petrograd just after troops of the Provisional Government opened fire in the July Days.

30.2.4: The October Revolution

On October 25, 1917, Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin led his leftist revolutionaries in a successful revolt against the ineffective provisional government, an event known as the October Revolution.

Learning Objective

Explain the events of the October Revolution

Key Points

- In the October Revolution (November in the Gregorian calendar), the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, and the workers’ soviets overthrew the Russian Provisional Government in Petrograd.

- The Bolsheviks appointed themselves as leaders of various government ministries and seized control of the countryside, establishing the Cheka to quash dissent.

- The October Revolution ended the phase of the revolution instigated in February, replacing Russia’s short-lived provisional parliamentary government with government by soviets, local councils elected by bodies of workers and peasants.

- To end Russia’s participation in the First World War, the Bolshevik leaders signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany in March 1918.

- Soviet membership was initially freely elected, but many members of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, anarchists, and other leftists created opposition to the Bolsheviks through the soviets themselves.

- When it became clear that the Bolsheviks had little support outside of the industrialized areas of Saint Petersburg and Moscow, they simply barred non-Bolsheviks from membership in the soviets.

- The new government soon passed the Decree on Peace and the Decree on Land, the latter of which redistributed land and wealth to peasants throughout Russia.

- A coalition of anti-Bolshevik groups attempted to unseat the new government in the Russian Civil War from 1918 to 1922.

Key Terms

- Decree on Land

-

Written by Vladimir Lenin, this law was passed by the Second Congress of Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’, and Peasants’ Deputies on October 26, 1917, following the success of the October Revolution. It decreed an abolition of private property and the redistribution of the landed estates among the peasantry.

- Marxism–Leninism

-

A political philosophy or worldview founded on ideas of Classical Marxism and Leninism that seeks to establish socialist states and develop them further. They espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of Marxism and Leninism, but generally support the idea of a vanguard party, one-party state, proletarian state-dominance over the economy, internationalism, opposition to bourgeois democracy, and opposition to capitalism. It remains the official ideology of the ruling parties of China, Cuba, Laos, Vietnam, a number of Indian states, and certain governed Russian oblasts such as Irkutsk. It was the official ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and the other ruling parties that made up the Eastern Bloc.

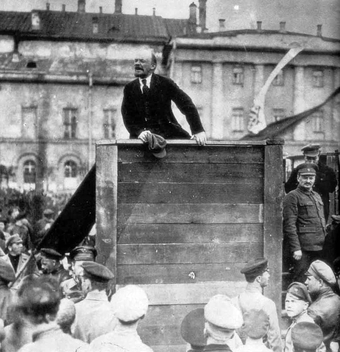

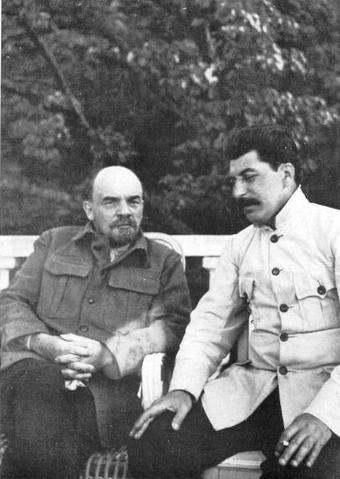

- Vladimir Lenin

-

A Russian communist revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as head of government of the Russian Republic from 1917 to 1918, of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic from 1918 to 1924, and of the Soviet Union from 1922 to 1924. Under his administration, Russia and then the wider Soviet Union became a one-party socialist state governed by the Russian Communist Party. Ideologically a Marxist, he developed political theories known as Leninism.

- October Revolution

-

A seizure of state power by the Bolshevik Party instrumental in the larger Russian Revolution of 1917. It took place with an armed insurrection in Petrograd on October 25, 1917. It followed and capitalized on the February Revolution of the same year.

The October Revolution, commonly referred to as Red October, the October Uprising, or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a seizure of state power instrumental in the larger Russian Revolution of 1917. It took place with an armed insurrection in Petrograd on October 25, 1917.

It followed and capitalized on the February Revolution of the same year, which overthrew the Tsarist autocracy and resulted in a provisional government after a transfer of power proclaimed by Grand Duke Michael, brother of Tsar Nicolas II, who declined to take power after the Tsar stepped down. During this time, urban workers began to organize into councils (Russian: Soviet) wherein revolutionaries criticized the provisional government and its actions. The October Revolution in Petrograd overthrew the provisional government and gave the power to the local soviets. The Bolshevik party was heavily supported by the soviets. After the Congress of Soviets, now the governing body, had its second session, it elected members of the Bolsheviks and other leftist groups such as the Left Socialist Revolutionaries to key positions within the new state of affairs. This immediately initiated the establishment of the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, the world’s first self-proclaimed socialist state.

The revolution was led by the Bolsheviks, who used their influence in the Petrograd Soviet to organize the armed forces. Bolshevik Red Guards forces under the Military Revolutionary Committee began the takeover of government buildings on October 24, 1917. The following day, the Winter Palace (the seat of the Provisional government located in Petrograd, then capital of Russia), was captured.

The long-awaited Constituent Assembly elections were held on November 12, 1917. The Bolsheviks only won 175 seats in the 715-seat legislative body, coming in second behind the Socialist Revolutionary party, which won 370 seats. The Constituent Assembly was to first meet on November 28, 1917, but its convocation was delayed until January 5, 1918, by the Bolsheviks. On its first and only day in session, the body rejected Soviet decrees on peace and land, and was dissolved the next day by order of the Congress of Soviets.

As the revolution was not universally recognized, there followed the struggles of the Russian Civil War (1917–22) and the creation of the Soviet Union in 1922.

Leadership and Ideology

The October Revolution was led by Vladimir Lenin and was based upon Lenin’s writing on the ideas of Karl Marx, a political ideology often known as Marxism-Leninism. Marxist-Leninists espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of Marxism and Leninism, but generally support the idea of a vanguard party, one-party state, proletarian state-dominance over the economy, internationalism, opposition to bourgeois democracy, and opposition to capitalism. The October Revolution marked the beginning of the spread of communism in the 20th century. It was far less sporadic than the revolution of February and came about as the result of deliberate planning and coordinated activity to that end.

Though Lenin was the leader of the Bolshevik Party, it has been argued that since Lenin was not present during the actual takeover of the Winter Palace, it was really Trotsky’s organization and direction that led the revolution, merely spurred by the motivation Lenin instigated within his party. Critics on the right have long argued that the financial and logistical assistance of German intelligence via agent Alexander Parvus was a key component as well, though historians are divided since there is little evidence supporting that claim.

Results

The Second Congress of Soviets consisted of 670 elected delegates; 300 were Bolshevik and nearly a hundred were Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, who also supported the overthrow of the Alexander Kerensky Government. When the fall of the Winter Palace was announced, the Congress adopted a decree transferring power to the Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies, thus ratifying the Revolution.