29.1: The Century of Peace

29.1.1: The European Continent After Vienna

Post-Napoleonic Europe was characterized by a general lack of major conflict between the great powers, with Great Britain as the major hegemonic power bringing relative balance to European politics.

Learning Objective

Compare post-Napoleonic Europe to the pre-French Revolution continent

Key Points

- At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the European powers came together at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to reorganize the political map of Europe and develop a system of conflict resolution aiming at preserving peace and balance of power, termed the Concert of Europe.

- From this point until the outbreak of World War I, there was relative peace and a lack of major conflict between the major powers, with wars generally localized and short-lived.

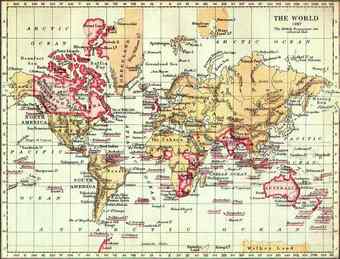

- The British and Russian empires expanded significantly and became the world’s leading powers. Britain’s navy had supremacy for most of the century, leading to the period often called the Pax Britannica (British Peace).

- From the 1870s onward, many nations experienced a sort of “golden age,” known as the Belle Époque, which coincided with the Gilded Age in the U.S.

- European politics saw very few regime changes during this period; however, tensions between working-class socialist parties, bourgeois liberal parties, and landed or aristocratic conservative parties increased in many countries. Some historians claim that profound political instability belied the calm surface of European politics in the era.

Key Terms

- hegemonic

-

The political, economic, or military predominance or control of one state over others.

- Concert of Europe

-

Also known as the Congress System or the Vienna System after the Congress of Vienna, a system of dispute resolution adopted by the major conservative powers of Europe to maintain their power, oppose revolutionary movements, weaken the forces of nationalism, and uphold the balance of power. It is suggested that it operated in Europe from the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1815) to the early 1820s, while some see it as lasting until the outbreak of the Crimean War, 1853-1856.

- Belle Époque

-

A period of Western European history conventionally dated from the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 to the outbreak of World War I around 1914. Occurring during the era of the French Third Republic (beginning 1870), it was characterized by optimism, regional peace, economic prosperity and technological, scientific and cultural innovations. In the climate of the period, especially in Paris, the arts flourished.

- Pax Britannica

-

The period of relative peace in Europe (1815–1914) during which the British Empire became the global hegemonic power and adopted the role of a global police force.

The 19th century was the century marked by the collapse of the Spanish, Napoleonic, Holy Roman, and Mughal empires. This paved the way for the growing influence of the British Empire, the Russian Empire, the United States, the German Empire, the French colonial empire, and Meiji Japan, with the British boasting unchallenged dominance after 1815. After the defeat of the French Empire and its allies in the Napoleonic Wars, the European powers came together at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to reorganize the political map of Europe to preserve peace and balance of power, termed the Concert of Europe.

The British and Russian empires expanded significantly and became the world’s leading powers. The Russian Empire expanded in central and far eastern Asia. The British Empire grew rapidly in the first half of the century, especially with the expansion of vast territories in Canada, Australia, South Africa, and heavily populated India, and in the last two decades of the century in Africa. By the end of the century, the British Empire controlled a fifth of the world’s land and one-quarter of the world’s population. During the post-Napoleonic era, it enforced what became known as the Pax Britannica, which had ushered in unprecedented globalization, industrialization, and economic integration on a massive scale.

At the beginning of this period, there was an informal convention recognizing five Great Powers in Europe: the French Empire, the British Empire, the Russian Empire, the Austrian Empire (later Austria-Hungary), and the Kingdom of Prussia (later the German Empire). In the late 19th century, the newly united Italy was added to this group. By the early 20th century, two non-European states, Japan and the United States, would come to be respected as fellow Great Powers.

The entire era lacked major conflict between these powers, with most skirmishes taking place between belligerents within the borders of individual countries. In Europe, wars were much smaller, shorter, and less frequent than ever before. The quiet century was shattered by World War I (1914–18), which was unexpected in its timing, duration, casualties, and long-term impact.

Pax Britannica

Pax Britannica (Latin for “British Peace,” modeled after Pax Romana) was the period of relative peace in Europe (1815–1914) during which the British Empire became the global hegemonic power and adopted the role of a global police force.

Between 1815 and 1914, a period referred to as Britain’s “imperial century,” around 10 million square miles of territory and roughly 400 million people were added to the British Empire. Victory over Napoleonic France left the British without any serious international rival, other than perhaps Russia in central Asia. When Russia tried expanding its influence in the Balkans, the British and French defeated it in the Crimean War (1854–56), thereby protecting the by-then feeble Ottoman Empire.

Britain’s Royal Navy controlled most of the key maritime trade routes and enjoyed unchallenged sea power. Alongside the formal control it exerted over its own colonies, Britain’s dominant position in world trade meant that it effectively controlled access to many regions, such as Asia and Latin America. British merchants, shippers, and bankers had such an overwhelming advantage over everyone else that in addition to its colonies it had an informal empire.

The global superiority of British military and commerce was aided by a divided and relatively weak continental Europe and the presence of the Royal Navy on all of the world’s oceans and seas. Even outside its formal empire, Britain controlled trade with countries such as China, Siam, and Argentina. Following the Congress of Vienna, the British Empire’s economic strength continued to develop through naval dominance and diplomatic efforts to maintain a balance of power in continental Europe.

In this era, the Royal Navy provided services around the world that benefited other nations, such as the suppression of piracy and blocking the slave trade. The Slave Trade Act 1807 banned the trade across the British Empire, after which the Royal Navy established the West Africa Squadron and the government negotiated international treaties under which they could enforce the ban. Sea power, however, did not project on land. Land wars fought between the major powers include the Crimean War, the Franco-Austrian War, the Austro-Prussian War, and the Franco-Prussian War, as well as numerous conflicts between lesser powers. The Royal Navy prosecuted the First Opium War (1839–1842) and Second Opium War (1856–1860) against Imperial China. The Royal Navy was superior to any other two navies in the world, combined. Between 1815 and the passage of the German naval laws of 1890 and 1898, only France was a potential naval threat.

The Pax Britannica was weakened by the breakdown of the continental order established by the Congress of Vienna. Relations between the Great Powers of Europe were strained to breaking by issues such as the decline of the Ottoman Empire, which led to the Crimean War, and later the emergence of new nation states of Italy and Germany after the Franco-Prussian War. Both wars involved Europe’s largest states and armies. The industrialization of Germany, the Empire of Japan, and the United States contributed to the relative decline of British industrial supremacy in the early 20th century.

Pax Britannica

Map of the world from 1897. The British Empire (marked in pink) was the superpower of the 19th century.

Belle Époque

The Belle Époque (French for “Beautiful Era”) was a period of Western European history conventionally dated from the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 to the outbreak of World War I in around 1914. Occurring during the era of the French Third Republic (beginning 1870), it was a period characterized by optimism, regional peace, economic prosperity, and technological, scientific and cultural innovations. In the climate of the period, especially in Paris, the arts flourished. Many masterpieces of literature, music, theater, and visual art gained recognition. The Belle Époque was named, in retrospect, when it began to be considered a “Golden Age” in contrast to the horrors of World War I.

In the United Kingdom, the Belle Époque overlapped with the late Victorian era and the Edwardian era. In Germany, the Belle Époque coincided with the Wilhelminism; in Russia with the reigns of Alexander III and Nicholas II. In the newly rich United States emerging from the Panic of 1873, the comparable epoch was dubbed the Gilded Age. In Brazil it started with the end of the Paraguayan War, and in Mexico the period was known as the Porfiriato.

The years between the Franco-Prussian War and World War I were characterized by unusual political stability in western and central Europe. Although tensions between the French and German governments persisted as a result of the French loss of Alsace-Lorraine to Germany in 1871, diplomatic conferences, including the Congress of Berlin in 1878, the Berlin Congo Conference in 1884, and the Algeciras Conference in 1906, mediated disputes that threatened the general European peace. For many Europeans in the Belle Époque period, transnational, class-based affiliations were as important as national identities, particularly among aristocrats. An upper-class gentleman could travel through much of Western Europe without a passport and even reside abroad with minimal bureaucratic regulation. World War I, mass transportation, the spread of literacy, and various citizenship concerns changed this.

European politics saw very few regime changes, the major exception being Portugal, which experienced a republican revolution in 1910. However, tensions between working-class socialist parties, bourgeois liberal parties, and landed or aristocratic conservative parties increased in many countries, and some historians claim that profound political instability belied the calm surface of European politics in the era. In fact, militarism and international tensions grew considerably between 1897 and 1914, and the immediate prewar years were marked by a general armaments competition in Europe. Additionally, this era was one of massive overseas colonialism known as the New Imperialism. The most famous portion of this imperial expansion was the Scramble for Africa.

29.1.2: Diplomacy in the 19th Century

The Congress of Vienna established many of the diplomatic norms of the 19th century and created an informal system of diplomatic conflict resolution aimed at maintaining a balance of power among nations, which contributed to the relative peace of the century.

Learning Objective

Describe the role diplomacy played on the European continent after Napoleon

Key Points

- Although the notion of diplomacy has existed since ancient times, the forms and practices of modern diplomacy were established at the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

- The Congress of Vienna was a meeting of the major powers of Europe aimed at providing a long-term peace plan for Europe by settling critical issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars.

- The goal was not simply to restore old boundaries but to resize the main powers so they could balance each other and remain at peace. Another goal was to develop a system of diplomatic conflict resolution called the Concert of Europe, whereby at times of crisis any of the member countries could propose a conference.

- Meetings of the Great Powers during this period included: Aix-la-Chapelle (1818), Carlsbad (1819), Troppau (1820), Laibach (1821), Verona (1822), London (1832), and Berlin (1878).

- The Concert’s effectiveness ended with the rise of nationalism, the 1848 Revolutions, the Crimean War, the unification of Germany, and the Eastern Question, among other factors.

- Later in the century, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, through juggling a complex interlocking series of conferences, negotiations, and alliances, used his diplomatic skills to maintain the balance of power in Europe to keep it at peace in the 1870s and 1880s.

Key Terms

- Concert of Europe

-

A system of dispute resolution adopted by the major conservative powers of Europe to maintain their power, oppose revolutionary movements, weaken the forces of nationalism, and uphold the balance of power. It is suggested that it operated in Europe from the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1815) to the early 1820s, while some see it as lasting until the outbreak of the Crimean War, 1853-1856.

- Congress of Vienna

-

A conference of ambassadors of European states chaired by Austrian statesman Klemens von Metternich and held in Vienna from November 1814 to June 1815, though the delegates had arrived and were already negotiating by late September 1814. The objective was to provide a long-term peace plan for Europe by settling critical issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. The goal was not simply to restore old boundaries but to resize the main powers so they could balance each other and remain at peace.

- Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord

-

A French bishop, politician, and diplomat. He worked at the highest levels of successive French governments, most commonly as foreign minister or in some other diplomatic capacity. His career spanned the regimes of Louis XVI, the years of the French Revolution, Napoleon, Louis XVIII, and Louis-Philippe.

Development of Modern Diplomacy

In Europe, early modern diplomacy’s origins are often traced to the states of Northern Italy in the early Renaissance, where the first embassies were established in the 13th century. Milan played a leading role especially under Francesco Sforza, who established permanent embassies to the other city states of Northern Italy. Tuscany and Venice were also flourishing centers of diplomacy from the 14th century onward. It was in the Italian Peninsula that many of the traditions of modern diplomacy began, such as the presentation of an ambassador’s credentials to the head of state. From Italy, the practice spread across Europe.

The elements of modern diplomacy arrived in Eastern Europe and Russia by the early 18th century. The entire edifice would be greatly disrupted by the French Revolution and the subsequent years of warfare. The revolution would see commoners take over the diplomacy of the French state and of those conquered by revolutionary armies. Ranks of precedence were abolished. Napoleon also refused to acknowledge diplomatic immunity, imprisoning several British diplomats accused of scheming against France.

After the fall of Napoleon, the Congress of Vienna of 1815 established an international system of diplomatic rank with ambassadors at the top, as they were considered personal representatives of their sovereign. Disputes on precedence among nations (and therefore the appropriate diplomatic ranks used) were first addressed at the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1818, but persisted for over a century until after World War II, when the rank of ambassador became the norm. In between, figures such as the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck were renowned for international diplomacy.

Congress of Vienna and the Concert of Europe

The Congress of Vienna of 1815 established many of the diplomatic norms for the 19th century. The objective of the Congress was to provide a long-term peace plan for Europe by settling critical issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. The goal was not simply to restore old boundaries but to resize the main powers so they could balance each other and remain at peace. The Concert of Europe, also known as the Congress System or the Vienna System after the Congress of Vienna, was a system of dispute resolution adopted by the major conservative powers of Europe to maintain their power, oppose revolutionary movements, weaken the forces of nationalism, and uphold the balance of power. It is suggested that it operated in Europe from the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1815) to the early 1820s, while some see it as lasting until the outbreak of the Crimean War, 1853-1856.

At first, the leading personalities of the system were British foreign secretary Lord Castlereagh, Austrian Chancellor Klemens von Metternich, and Tsar Alexander I of Russia. Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord played a major role at the Congress of Vienna in 1814–1815, where he negotiated a favorable settlement for France while undoing Napoleon’s conquests. Talleyrand polarizes scholarly opinion. Some regard him as one of the most versatile, skilled, and influential diplomats in European history, and some believe that he was a traitor, betraying in turn the Ancien Régime, the French Revolution, Napoleon, and the Restoration. Talleyrand worked at the highest levels of successive French governments, most commonly as foreign minister or in some other diplomatic capacity. His career spanned the regimes of Louis XVI, the years of the French Revolution, Napoleon, Louis XVIII, and Louis-Philippe. Those he served often distrusted Talleyrand but like Napoleon, found him extremely useful. The name “Talleyrand” has become a byword for crafty, cynical diplomacy.

Talleyrand

French diplomat Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord is considered one of the most skilled diplomats of all time.

The Concert of Europe had no written rules or permanent institutions, but at times of crisis any of the member countries could propose a conference. Diplomatic meetings of the Great Powers during this period included: Aix-la-Chapelle (1818), Carlsbad (1819), Troppau (1820), Laibach (1821), Verona (1822), London (1832), and Berlin (1878).

The Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle (1818) resolved the issues of Allied occupation of France and restored that country to equal status with Britain, Prussia, Austria, and Russia. The congress, which broke up at the end of November, is of historical importance mainly as marking the highest point reached during the 19th century in the attempt to govern Europe by an international committee of the powers. The detailed study of its proceedings is highly instructive in revealing the almost insurmountable obstacles to any truly effective international diplomatic system prior to the creation of the League of Nations after the First World War.

The territorial boundaries laid down at the Congress of Vienna were maintained; even more importantly, there was an acceptance of the theme of balance with no major aggression. Otherwise, the Congress system, says historian Roy Bridge, “failed” by 1823. In 1818, the British decided not to become involved in continental issues that did not directly affect them. They rejected the plan of Alexander I to suppress future revolutions. The Concert system fell apart as the common goals of the Great Powers were replaced by growing political and economic rivalries. There was no Congress called to restore the old system during the great revolutionary upheavals of 1848 with their demands for revision of the Congress of Vienna’s frontiers along national lines.

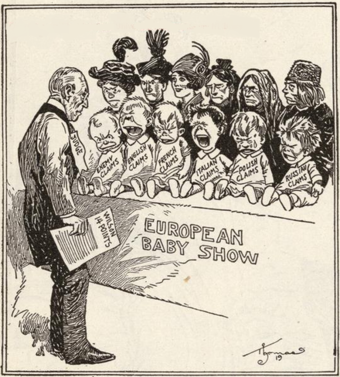

The Congress of Vienna was frequently criticized by 19th-century and more recent historians for ignoring national and liberal impulses and imposing a stifling reaction on the Continent. It was an integral part of what became known as the Conservative Order, in which the liberties and civil rights associated with the American and French Revolutions were de-emphasized so that a fair balance of power, peace and stability might be achieved.

In the 20th century, however, many historians came to admire the statesmen at the Congress, whose work prevented another widespread European war for nearly a hundred years (1815–1914). Historian Mark Jarrett argues that the Congress of Vienna and the Congress System marked “the true beginning of our modern era.” He says the Congress System was deliberate conflict management and the first genuine attempt to create an international order based upon consensus rather than conflict. “Europe was ready,” Jarrett states, “to accept an unprecedented degree of international cooperation in response to the French Revolution.” It served as a model for later organizations such as the League of Nations in 1919 and the United Nations in 1945. Prior to the opening of the Paris peace conference of 1918, the British Foreign Office commissioned a history of the Congress of Vienna to serve as an example to its own delegates of how to achieve an equally successful peace.

Otto von Bismarck: Balance of Power Diplomacy

Otto von Bismarck was a conservative Prussian statesman and diplomat who dominated German and European affairs from the 1860s until 1890. He skillfully used balance of power diplomacy to maintain Germany’s position in a Europe which, despite many disputes and war scares, remained at peace. For historian Eric Hobsbawm, it was Bismarck who “remained undisputed world champion at the game of multilateral diplomatic chess for almost twenty years after 1871, [and] devoted himself exclusively, and successfully, to maintaining peace between the powers.”

In 1862, King Wilhelm I appointed Bismarck as Minister President of Prussia, a position he would hold until 1890 (except for a short break in 1873). He provoked three short, decisive wars against Denmark, Austria, and France, aligning the smaller German states behind Prussia in its defeat of France. In 1871, he formed the German Empire with himself as Chancellor while retaining control of Prussia. His diplomacy of pragmatic realpolitik and powerful rule at home gained him the nickname the “Iron Chancellor.” German unification and its rapid economic growth was the foundation to his foreign policy. He disliked colonialism but reluctantly built an overseas empire when demanded by both elite and mass opinion. Juggling a very complex interlocking series of conferences, negotiations and alliances, he used his diplomatic skills to maintain Germany’s position and used the balance of power to keep Europe at peace in the 1870s and 1880s.

29.1.3: The World Fairs

World fairs during the late 19th century and early 20th centuries showcased the technological, industrial, and cultural achievements of nations around the world, sometimes displaying cultural superiority over colonized nations through human exhibits.

Learning Objective

Assess the World Fairs and their purpose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries

Key Points

- World fairs are international exhibits displaying the achievements of nations, largely focused on technological and industrial developments.

- World fairs originated in the French tradition of national exhibitions that culminated with the French Industrial Exposition of 1844 held in Paris.

- The Great Exhibition held in London in 1851 established many of the familiar components of world fairs and is usually considered to be the first international exhibition of manufactured products.

- Since their inception, the character of world expositions has evolved and is sometimes categorized into three eras: industrialization, cultural exchange, and nation branding.

- Also present in many world fairs at the time as well as in smaller local fairs were exhibits of people from the colonized world in their native environments, often with an explicit narrative of European superiority.

Key Terms

- The Great Exhibition

-

An international exhibition that took place in Hyde Park, London, from May 1 to October 11, 1851. It was the first in a series of world fairs, exhibitions of culture and industry that became popular in the 19th century, and was a much anticipated event. It was organized by Henry Cole and Prince Albert, husband of the reigning monarch Queen Victoria. It was attended by numerous notable figures of the time, including Charles Darwin, Samuel Colt, members of the Orléanist Royal Family, and the writers Charlotte Brontë, Charles Dickens, Lewis Carroll, George Eliot, and Alfred Tennyson.

- human zoos

-

Public exhibitions of humans, usually in a so-called natural or primitive state. The displays often emphasized the cultural differences between Europeans of Western civilization and non-European peoples or other Europeans with a lifestyle deemed primitive. Some placed indigenous Africans in a continuum somewhere between the great apes and the white man.

A world’s fair, world fair, world exposition, or universal exposition (sometimes expo for short), is a large international exhibition designed to showcase achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in various parts of the world.

World fairs originated in the French tradition of national exhibitions that culminated with the French Industrial Exposition of 1844 held in Paris. This fair was followed by other national exhibitions in continental Europe and the United Kingdom.

The best-known “first World Expo” was held in The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, United Kingdom, in 1851, under the title “Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations.” The Great Exhibition, as it is often called, was an idea of Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, and is usually considered to be the first international exhibition of manufactured products. It was arguably a response to the highly successful French Industrial Exposition of 1844; indeed, its prime motive was for Britain to display itself as an industrial leader. It influenced the development of several aspects of society, including art-and-design education, international trade and relations, and tourism. This expo was the most obvious precedent for the many international exhibitions considered world fairs.

Since their inception in 1851, the character of world expositions has evolved. Three eras can be distinguished: industrialization, cultural exchange, and nation branding.

The first era could be called the era of “industrialization” and covered roughly the period from 1800 to 1938. In these days, world expositions were especially focused on trade and were famous for the display of technological inventions and advancements. World expositions were the platforms where the state-of-the-art in science and technology from around the world were brought together. The world expositions of 1851 London, 1853 New York, 1862 London, 1876 Philadelphia, 1889 Paris, 1893 Chicago, 1897 Brussels, 1900 Paris, 1901 Buffalo, 1904 St. Louis, 1915 San Francisco, and 1933–34 Chicago were landmarks in this respect. Inventions such as the telephone were first presented during this era.

The 1939–40 New York World’s Fair diverged from the original focus of the world fair expositions. From then on, world fairs adopted specific cultural themes forecasting a better future for society. Technological innovations were no longer the primary exhibits at fairs.

From Expo ’88 in Brisbane onward, countries such as Finland, Japan, Canada, France, and Spain started to use world expositions as platforms to improve their national images.

World Fairs

A poster advertising the Brussels International Exposition.

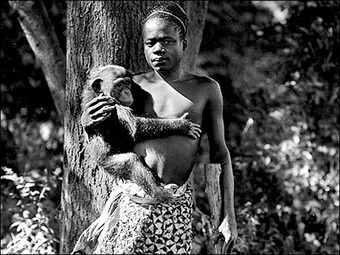

Colonialism on Display

Human zoos, also called ethnological expositions, were 19th-, 20th-, and 21st-century public exhibitions of humans, usually in a so-called natural or primitive state. The displays often emphasized the cultural differences between Europeans of Western civilization and non-European peoples or other Europeans with a lifestyle deemed primitive. Some of them placed indigenous Africans in a continuum somewhere between the great apes and the white man. Ethnological expositions have since been criticized as highly degrading and racist.

The notion of human curiosity and exhibition has a history at least as long as colonialism. In the 1870s, exhibitions of exotic populations became popular in various countries. Human zoos could be found in Paris, Hamburg, Antwerp, Barcelona, London, Milan, and New York City. Carl Hagenbeck, a merchant in wild animals and future entrepreneur of many European zoos, decided in 1874 to exhibit Samoan and Sami people as “purely natural” populations. In 1876, he sent a collaborator to the Egyptian Sudan to bring back some wild beasts and Nubians. The Nubian exhibit was very successful in Europe and toured Paris, London, and Berlin.

Both the 1878 and the 1889 Parisian World’s Fair presented a Negro Village (village nègre). Visited by 28 million people, the 1889 World’s Fair displayed 400 indigenous people as the major attraction. The 1900 World’s Fair presented the famous diorama living in Madagascar, while the Colonial Exhibitions in Marseilles (1906 and 1922) and in Paris (1907 and 1931) also displayed humans in cages, often nude or semi-nude. The 1931 exhibition in Paris was so successful that 34 million people attended it in six months, while a smaller counter-exhibition entitled The Truth on the Colonies, organized by the Communist Party, attracted very few visitors—in the first room, it recalled Albert Londres and André Gide’s critiques of forced labor in the colonies. Nomadic Senegalese Villages were also presented.

In 1904, Apaches and Igorots (from the Philippines) were displayed at the Saint Louis World Fair in association with the 1904 Summer Olympics. The U.S. had just acquired, following the Spanish–American War, new territories such as Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico, allowing them to “display” some of the native inhabitants. According to the Rev. Sequoyah Ade:

To further illustrate the indignities heaped upon the Philippine people following their eventual loss to the Americans, the United States made the Philippine campaign the centrepoint of the 1904 World’s Fair held that year in St. Louis, MI [sic]. In what was enthusiastically termed a “parade of evolutionary progress,” visitors could inspect the “primitives” that represented the counterbalance to “Civilisation” justifying Kipling’s poem “The White Man’s Burden.” Pygmies from New Guinea and Africa, who were later displayed in the Primate section of the Bronx Zoo, were paraded next to American Indians such as Apache warrior Geronimo, who sold his autograph. But the main draw was the Philippine exhibition complete with full size replicas of Indigenous living quarters erected to exhibit the inherent backwardness of the Philippine people. The purpose was to highlight both the “civilising” influence of American rule and the economic potential of the island chains’ natural resources on the heels of the Philippine–American War. It was, reportedly, the largest specific Aboriginal exhibition displayed in the exposition. As one pleased visitor commented, the human zoo exhibition displayed “the race narrative of odd peoples who mark time while the world advances, and of savages made, by American methods, into civilized workers.”

Ota Benga at the Bronx Zoo

From a sign outside the primate house at the Bronx Zoo, September 1906: “Ota Benga, a human exhibit, in 1906. Age, 23 years. Height, 4 feet 11 inches (150 cm). Weight, 103 pounds (47 kg). Brought from the Kasai River, Congo Free State, South Central Africa, by Dr. Samuel P. Verner. Exhibited each afternoon during September.”

29.2: The Coming of War

29.2.1: The Sick Man of Europe

The “Eastern Question” refers to the strategic competition and political considerations of the European Great Powers in light of the political and economic instability of the Ottoman Empire, named the “Sick Man of Europe.”

Learning Objective

Evaluate the claim that the Ottoman Empire was the “Sick Man of Europe”

Key Points

- Throughout the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire underwent major changes, first through a series of modernizing efforts that strengthened its power, but ultimately to its decline in terms of military prestige, territory, and wealth.

- The Ottoman state, which took on debt with the Crimean War, was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1875.

- By 1881, the Ottoman Empire agreed to have its debt controlled by an institution known as the Ottoman Public Debt Administration, a council of European men with presidency alternating between France and Britain.

- In response to these changes and crises in the Ottoman Empire, the Major Powers of Europe, especially Russia and Britain, began referring to the Empire as the “Sick Man of Europe,” with various ideas as to how best serve their own interests as this major empire began to collapse.

- In diplomatic history, this issue is referred to as the “Eastern Question” and encompasses the strategic competition and political considerations of the European Great Powers in light of the political and economic instability in the Ottoman Empire, which in part led to outbreak of World War I.

Key Terms

- Concert of Europe

-

Also known as the Congress System or the Vienna System after the Congress of Vienna, a system of dispute resolution adopted by the major conservative powers of Europe to maintain their power, oppose revolutionary movements, weaken the forces of nationalism, and uphold the balance of power. It is suggested that it operated in Europe from the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1815) to the early 1820s, while some see it as lasting until the outbreak of the Crimean War, 1853-1856.

- sick man of Europe

-

A label given to a European country experiencing a time of economic difficulty or impoverishment. The term was first used in the mid-19th century to describe the Ottoman Empire, but has since been applied at one time or another to nearly every other major country in Europe.

- Eastern Question

-

In diplomatic history, this refers to the strategic competition and political considerations of the European Great Powers in light of the political and economic instability in the Ottoman Empire from the late 18th to early 20th centuries.

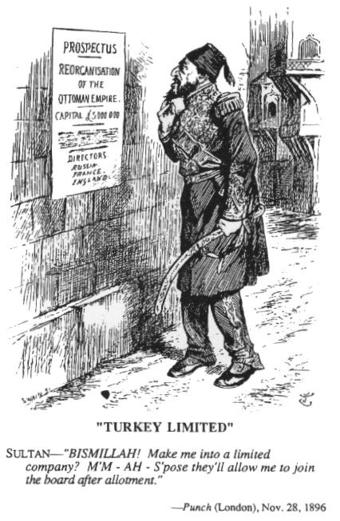

The Eastern Question

In diplomatic history, the “Eastern Question” refers to the strategic competition and political considerations of the European Great Powers in light of the political and economic instability in the Ottoman Empire from the late 18th to early 20th centuries. Characterized as the “sick man of Europe,” the relative weakening of the empire’s military strength in the second half of the 18th century threatened to undermine the fragile balance of power system largely shaped by the Concert of Europe. The Eastern Question encompassed myriad interrelated elements: Ottoman military defeats, Ottoman institutional insolvency, the ongoing Ottoman political and economic modernization programs, the rise of ethno-religious nationalism in its provinces, and Great Power rivalries.

The Eastern Question is normally dated to 1774, when the Russo-Turkish War (1768–74) ended in defeat for the Ottomans. As the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire was believed to be imminent, the European powers engaged in a power struggle to safeguard their military, strategic, and commercial interests in the Ottoman domains. Imperial Russia stood to benefit from the decline of the Ottoman Empire; on the other hand, Austria-Hungary and Great Britain deemed the preservation of the Empire to be in their best interests. The Eastern Question was put to rest after World War I, one of the outcomes of which was the collapse and division of the Ottoman holdings.

A book by Harold Temperley quotes Nicholas I of Russia as saying in 1853, “Turkey seems to be falling to pieces, the fall will be a great misfortune. It is very important that England and Russia should come to a perfectly good understanding… and that neither should take any decisive step of which the other is not apprized…We have a sick man on our hands, a man gravely ill, it will be a great misfortune if one of these days he slips through our hands, especially before the necessary arrangements are made.”

In the 1870s the “Eastern Question” focused on the mistreatment of Christians in the Balkans by the Ottoman Empire and what the European great powers ought to do about it.

In 1876 Serbia and Montenegro declared war on Turkey and were badly defeated, notably at the battle of Alexinatz (Sept. 1, 1876). Gladstone published an angry pamphlet on “The Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East,” which aroused enormous agitation in Britain against Turkish misrule and complicated the Disraeli government’s policy of supporting Turkey against Russia. Russia, which supported Serbia, threatened war against Turkey. In August 1877, Russia declared war on Turkey and steadily defeated its armies. In early January 1878 Turkey asked for an armistice, but the British fleet arrived at Constantinople too late. Russia and Turkey on March 3 signed the Treaty of San Stefano, which was highly advantageous to Russia, Serbia, and Montenegro as well as Romania and Bulgaria.

Britain, France, and Austria opposed the Treaty of San Stefano because it gave Russia too much influence in the Balkans, where insurrections were frequent. War threatened. After numerous attempts, a grand diplomatic settlement was reached at the Congress of Berlin (June–July 1878). The new Treaty of Berlin revised the earlier treaty. Germany’s Otto von Bismarck (1815–98) presided over the congress and brokered the compromises. One result was that Austria took control of the provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina, intending to eventually merge them into the Austro-Hungarian Empire. When they finally tried to do that in 1914, local Serbs assassinated Austria’s Archduke and the result was the First World War.

“Sick Man of Europe”

Caricature from Punch magazine dated November 28, 1896. It shows Sultan Abdul Hamid II in front of a poster that announces the reorganization of the Ottoman Empire. The empire’s value is estimated at 5 million pounds. Russia, France, and England are listed as the directors of the reorganization. The caricature refers to the Ottoman Empire, which was increasingly falling under the financial control of the European powers and had lost territory.

Ottoman Decline Up to World War I

Beginning from the late 18th century, the Ottoman Empire faced challenges defending itself against foreign invasion and occupation. In response to foreign threats, the empire initiated a period of tremendous internal reform that came to be known as the Tanzimat, which succeeded in significantly strengthening the Ottoman central state despite the empire’s precarious international position. Over the course of the 19th century, the Ottoman state became increasingly powerful and rationalized, exercising a greater degree of influence over its population than in any previous era.

As the Ottoman state attempted to modernize its infrastructure and army in response to threats from the outside, it also opened itself up to a different kind of threat: that of creditors. Indeed, as the historian Eugene Rogan has written, “the single greatest threat to the independence of the Middle East” in the 19th century “was not the armies of Europe but its banks.” The Ottoman state, which had begun taking on debt with the Crimean War, was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1875. By 1881, the Ottoman Empire agreed to have its debt controlled by an institution known as the Ottoman Public Debt Administration, a council of European men with presidency alternating between France and Britain. The body controlled swaths of the Ottoman economy and used its position to insure that European capital continued to penetrate the empire, often to the detriment of local Ottoman interests.

The defeat and dissolution of the Ottoman Empire (1908–1922) began with the Second Constitutional Era, a moment of hope and promise established with the Young Turk Revolution. It restored the Ottoman constitution of 1876 and brought in multi-party politics with a two-stage electoral system (electoral law) under the Ottoman parliament. The constitution offered hope by freeing the empire’s citizens to modernize the state’s institutions, rejuvenate its strength, and enable it to hold its own against outside powers. Its guarantee of liberties promised to dissolve inter-communal tensions and transform the empire into a more harmonious place.

Instead, this period became the story of the twilight struggle of the Empire. A proliferation of conflicting political parties created discord and confusion. Profiting from the civil strife, Austria-Hungary officially annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908. Ottoman military reforms resulted in a modern army which engaged in the Italo-Turkish War (1911) that ended in the loss of the North African territories and the Dodecanese, the Balkan Wars (1912–1913) that ended in the loss of almost all of the Empire’s European territories. In addition, the Empire faced continuous civil and political unrest with several military coups leading up to World War I.

29.2.2: Militarism and Jingoism

During the 1870s and 1880s, all major powers were preparing for a large-scale war by increasing the sizes of their armies and navies. This led to increased political tensions that many historians consider a major factor in the outbreak of World War I.

Learning Objective

Assess the rise of militarism in the years preceding WWI

Key Points

- During the second half of the 19th century, all major world powers began increasing the sizes and scopes of their military forces, although a conflict on the scale of WWI was not expected by anyone.

- Germany, France, Austria, Italy, Russia, and some smaller countries set up conscription systems whereby young men served from one to three years in the army, then spent the next 20 years in the reserves with annual summer training.

- Germany struggled to achieve parity with the British navy in a tense arms race, but in the end fell short with Britain remaining the dominant naval power.

- Many historians point to this increased military preparedness as the major factor that led to the outbreak of WWI, contending that had the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand happened a decade before, war would probably have been avoided.

- Jingoism is nationalism in the form of aggressive foreign policy, whereby a nation advocates for the use of threats or actual force as opposed to peaceful relations to safeguard what it perceives as its national interests.

Key Terms

- militarism

-

The belief or the desire of a government or people that a country should maintain a strong military capability and be prepared to use it aggressively to defend or promote national interests. It may also imply the glorification of the military, the ideals of a professional military class, and the “predominance of the armed forces in the administration or policy of the state.”

- conscription

-

The compulsory enlistment of people in a national service, most often military service. The practice dates back to antiquity and continues in some countries to the present day under various names. The modern system dates to the French Revolution in the 1790s, where it became the basis of a very large and powerful military. Most European nations later copied the system in peacetime so that men at a certain age would serve one to eight years on active duty and then transfer to the reserve force.

- jingoism

-

A form of nationalism characterized by aggressive foreign policy. It refers to a country’s advocacy for the use of threats or actual force as opposed to peaceful relations to safeguard what it perceives as its national interests.

Rise of Militarism Prior to World War I

The main causes of World War I, which broke out unexpectedly in central Europe in summer 1914, comprised all the conflicts and hostility of the four decades leading up to the war. Militarism, alliances, imperialism, and ethnic nationalism played major roles.

During the 1870s and 1880s, all major world powers were preparing for a large-scale war, although none expected one. Britain focused on building up its Royal Navy, already stronger than the next two navies combined. Germany, France, Austria, Italy, Russia, and some smaller countries set up conscription systems whereby young men would serve from one to three years in the army, then spend the next 20 years or so in the reserves with annual summer training. Men from higher social classes became officers. Each country devised a mobilization system so the reserves could be called up quickly and sent to key points by rail. Every year the plans were updated and expanded in terms of complexity. Each country stockpiled arms and supplies for an army that ran into the millions.

Germany in 1874 had a regular professional army of 420,000 with an additional 1.3 million reserves. By 1897 the regular army was 545,000 strong and the reserves 3.4 million. The French in 1897 had 3.4 million reservists, Austria 2.6 million, and Russia 4.0 million. The various national war plans had been perfected by 1914, albeit with Russia and Austria trailing in effectiveness. Recent wars (since 1865) had typically been short—a matter of months. All the war plans called for a decisive opening and assumed victory would come after a short war; no one planned for or was ready for the food and munitions needs of a long stalemate as actually happened in 1914–18.

As David Stevenson has put it, “A self-reinforcing cycle of heightened military preparedness … was an essential element in the conjuncture that led to disaster … The armaments race … was a necessary precondition for the outbreak of hostilities.” If Archduke Franz Ferdinand had been assassinated in 1904 or even in 1911, Herrmann speculates, there might have been no war. It was “… the armaments race … and the speculation about imminent or preventive wars” that made his death in 1914 the trigger for war.

This increase in militarism coincided with the rise of jingoism, a term for nationalism in the form of aggressive foreign policy. Jingoism also refers to a country’s advocacy for the use of threats or actual force, as opposed to peaceful relations, to safeguard what it perceives as its national interests. Colloquially, it refers to excessive bias in judging one’s own country as superior to others—an extreme type of nationalism. The term originated in reference to the United Kingdom’s pugnacious attitude toward Russia in the 1870s, and appeared in the American press by 1893.

Probably the first uses of the term in the U.S. press occurred in connection with the proposed annexation of Hawaii in 1893. A coup led by foreign residents, mostly Americans, and assisted by the U.S. Minister in Hawaii, overthrew the Hawaiian constitutional monarchy and declared a Republic. Republican president Benjamin Harrison and Republicans in the Senate were frequently accused of jingoism in the Democratic press for supporting annexation.

The term was also used in connection with the foreign policy of Theodore Roosevelt. In an October 1895 New York Times article, Roosevelt stated, “There is much talk about ‘jingoism’. If by ‘jingoism’ they mean a policy in pursuance of which Americans will with resolution and common sense insist upon our rights being respected by foreign powers, then we are ‘jingoes’.”

One of the aims of the First Hague Conference of 1899, held at the suggestion of Emperor Nicholas II, was to discuss disarmament. The Second Hague Conference was held in 1907. All signatories except for Germany supported disarmament. Germany also did not want to agree to binding arbitration and mediation. The Kaiser was concerned that the United States would propose disarmament measures, which he opposed. All parties tried to revise international law to their own advantage.

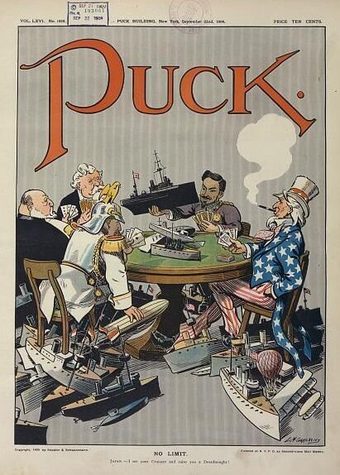

Anglo-German Naval Race

Historians have debated the role of the German naval build-up as the principal cause of deteriorating Anglo-German relations. In any case, Germany never came close to catching up with Britain.

Supported by Wilhelm II’s enthusiasm for an expanded German navy, Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz championed four Fleet Acts from 1898 to 1912, and from 1902 to 1910, the Royal Navy embarked on its own massive expansion to keep ahead of the Germans. This competition came to focus on the revolutionary new ships based on the Dreadnought, launched in 1906, awhich gave Britain a battleship that far outclassed any other in Europe.

The overwhelming British response proved to Germany that its efforts were unlikely to equal those of the Royal Navy. In 1900, the British had a 3.7:1 tonnage advantage over Germany; in 1910 the ratio was 2.3:1 and in 1914, 2.1:1. Ferguson argues that, “So decisive was the British victory in the naval arms race that it is hard to regard it as in any meaningful sense a cause of the First World War.” This ignores the fact that the Kaiserliche Marine had narrowed the gap by nearly half, and that the Royal Navy had long intended to be stronger than any two potential opponents; the United States Navy was in a period of growth, making the German gains very ominous.

In Britain in 1913, there was intense internal debate about new ships due to the growing influence of John Fisher’s ideas and increasing financial constraints. In early to mid-1914 Germany adopted a policy of building submarines instead of new dreadnoughts and destroyers, effectively abandoning the race, but kept this new policy secret to delay other powers following suit.

The Germans abandoned the naval race before the war broke out. The extent to which the naval race was one of the chief factors in Britain’s decision to join the Triple Entente remains a key controversy. Historians such as Christopher Clark believe it was not significant, with Margaret Moran taking the opposite view.

Naval Arms Race

1909 cartoon in Puck shows the United States, Germany, Britain, France, and Japan engaged in naval race in a “no limit” game.

29.2.3: The Balkan Powder Keg

The continuing collapse of the Ottoman Empire coincided with the rise of nationalism in the Balkans, which led to increased tensions and conflicts in the region. This “powder keg” was thus a major catalyst for the outbreak of World War I.

Learning Objective

Define the Balkan Powder Keg

Key Points

- By the early 20th century, Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro, and Serbia had achieved independence from the Ottoman Empire, but large elements of their ethnic populations remained under Ottoman rule. In 1912 these countries formed the Balkan League and declared war on the Ottomans to reclaim territory.

- Four Balkan states defeated the Ottoman Empire in the first war; one of the four, Bulgaria, suffered defeat in the second war.

- The tensions and conflicts in this are often referred to as the “Balkan powder keg” and had implications beyond the region.

- There were a number of overlapping claims to territories and spheres of influence between the major European powers, such as the Russian Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the German Empire and, to a lesser degree, the Ottoman Empire, the United Kingdom, and Kingdom of Italy.

- Relations between Austria and Serbia became increasingly bitter and Russia felt humiliated after Austria and Germany prevented it from helping Serbia.

- The powder keg eventually “exploded” causing the First World War, which began with a conflict between imperial Austria-Hungary and Pan-Slavic Serbia.

Key Terms

- irredentism

-

Any political or popular movement intended to reclaim and reoccupy a “lost” or “unredeemed” area; territorial claims are justified on the basis of real or imagined national and historic (an area formerly part of that state) or ethnic (an area inhabited by that nation or ethnic group) affiliations. It is often advocated by nationalist and pan-nationalist movements and has been a feature of identity politics and cultural and political geography.

- Balkans

-

A peninsula and a cultural area in Southeastern Europe with various and disputed borders. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch from the Serbia-Bulgaria border to the Black Sea. Conflicts here were a major contributing factor to the outbreak of WWI.

- Pan-Slavism

-

A movement which crystallized in the mid-19th century concerned with the advancement of integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires—the Byzantine Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Venice—had ruled the South Slavs for centuries.

The “Balkan powder keg,” also termed the “powder keg of Europe,” refers to the Balkans in the early part of the 20th century preceding World War I. There were a number of overlapping claims to territories and spheres of influence between the major European powers, such as the Russian Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the German Empire and, to a lesser degree, the Ottoman Empire, the United Kingdom, and Kingdom of Italy.

In addition to the imperialistic ambitions and interests in this region, there was a growth in nationalism among the indigenous peoples, leading to the formation of the independent states of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, Romania, and Albania.

Within these nations, there were movements to create “greater” nations: to enlarge the boundaries of the state beyond those areas where the national ethnic group was in the majority (termed irredentism). This led to conflict between the newly independent nations and the empire from which they split, the Ottoman Empire. Additionally, it led to differences between the Balkan nations who wished to gain territory at the expense of their neighbors. Both the conflict with the Ottoman Empire and between the Balkan nations led to the Balkan Wars, discussed below.

In a different vein, the ideology of Pan-Slavism in Balkans gained popularity; the movement built around it in the region sought to unite all of the Slavs of the Balkans into one nation, Yugoslavia. This, however, would require the union of several Balkan states and territory that was part of Austria-Hungary. For this reason, Pan-Slavism was strongly opposed by Austria-Hungary, while it was supported by Russia which viewed itself as leader of all Slavic nations.

To complicate matters, in the years preceding World War I, there existed a tangle of Great Power alliances, both formal and informal, public and secret. Following the Napoleonic Wars, there existed a “balance of power” to prevent major wars. This theory held that opposing combinations of powers in Europe would be evenly matched, entailing that any general war would be far too costly to risk entering. This system began to fall apart as the Ottoman Empire, seen as a check on Russian power, began to crumble, and as Germany, a loose confederation of minor states, was united into a major power. Not only did these changes lead to a realignment of power, but of interests as well.

All these factors and many others conspired to bring about the First World War. As is insinuated by the name “the powder keg of Europe,” the Balkans were not the major issue at stake in the war, but were the catalyst that led to the conflagration. The Chancellor of Germany in the late 19th century, Otto von Bismarck, correctly predicted it would be the source of major conflict in Europe.

The powder keg “exploded” causing the First World War, which began with a conflict between imperial Austria-Hungary and Pan-Slavic Serbia.

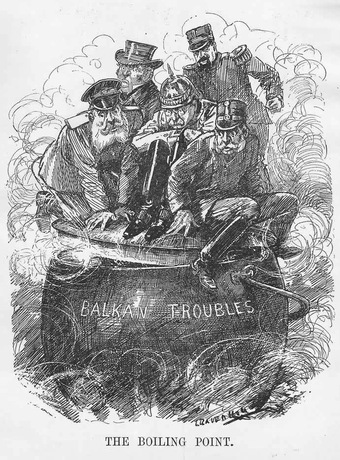

Balkan Troubles

Germany, France, Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Britain attempting to keep the lid on the simmering cauldron of imperialist and nationalist tensions in the Balkans to prevent a general European war. They were successful in 1912 and 1913 but did not succeed in 1914, resulting in the outbreak of World War I.

Balkan Wars

The continuing collapse of the Ottoman Empire led to two wars in the Balkans, in 1912 and 1913, which was a prelude to world war. By 1900 nation states had formed in Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro and Serbia. Nevertheless, many of their ethnic compatriots lived under the control of the Ottoman Empire. In 1912, these countries formed the Balkan League. There were three main causes of the First Balkan War. The Ottoman Empire was unable to reform itself, govern satisfactorily, or deal with the rising ethnic nationalism of its diverse peoples. Secondly, the Great Powers quarreled among themselves and failed to ensure that the Ottomans would carry out the needed reforms. This led the Balkan states to impose their own solution. Most importantly, the members of the Balkan League were confident that it could defeat the Turks, which would prove to be the case.

The First Balkan War broke out when the League attacked the Ottoman Empire on October 8, 1912, and was ended seven months later by the Treaty of London. After five centuries, the Ottoman Empire lost virtually all of its possessions in the Balkans. The Treaty had been imposed by the Great Powers, dissatisfying the victorious Balkan states. Bulgaria was dissatisfied over the division of the spoils in Macedonia, made in secret by its former allies, Serbia and Greece, and attacked to force them out of Macedonia, starting the Second Balkan War. The Serbian and Greek armies repulsed the Bulgarian offensive and counter-attacked into Bulgaria, while Romania and the Ottoman Empire also attacked Bulgaria and gained (or regained) territory. In the resulting Treaty of Bucharest, Bulgaria lost most of the territories it had gained in the First Balkan War.

The long-term result was heightened tension in the Balkans. Relations between Austria and Serbia became increasingly bitter. Russia felt humiliated after Austria and Germany prevented it from helping Serbia. Bulgaria and Turkey were also dissatisfied, and eventually joined Austria and Germany in the First World War.

29.2.4: Archduke Franz Ferdinand

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was shot dead in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip, one of a group of six assassins coordinated by Danilo Ilić, a Bosnian Serb and a member of the Black Hand secret society. This event led to a diplomatic crisis and the outbreak of World War I.

Learning Objective

Discuss Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Key Points

- Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, a member of the Austrian royal family and heir presumptive to the Austrian throne, was assassinated by Gavrilo Princip, a member of the Young Bosnia movement connected to the Blank Hand secret society.

- The political objective of the assassination was to break off Austria-Hungary’s South Slav provinces so they could be combined into Yugoslavia.

- The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand sent deep shock waves through Austrian elites. The murder was described by Christopher Clark as “a terrorist event charged with historic meaning, transforming the political chemistry in Vienna.”

- The assassination triggered the July Crisis, a series of tense diplomatic maneuverings that led to an ultimatum from Austria-Hungary to the Kingdom of Serbia, who rejected some of these conditions as a violation of their sovereignty. This led to Austria-Hungary invading Serbia.

- The system of European alliances led to a series of escalating Austrian and Russian mobilizations. Eventually, Britain and France were also obliged to mobilize and declare war, beginning World War I.

Key Terms

- Black Hand

-

A secret military society formed on May 9, 1911, by officers in the Army of the Kingdom of Serbia, originating in the conspiracy group that assassinated the Serbian royal couple (1903) led by captain Dragutin Dimitrijević “Apis.”

- irredentism

-

Any political or popular movement intended to reclaim and reoccupy a “lost” or “unredeemed” area; territorial claims are justified on the basis of real or imagined national and historic (an area formerly part of that state) or ethnic (an area inhabited by that nation or ethnic group) affiliations. It is often advocated by nationalist and pan-nationalist movements and has been a feature of identity politics and cultural and political geography.

- July Crisis

-

A diplomatic crisis among the major powers of Europe in the summer of 1914 that led to World War I. Immediately after Gavrilo Princip, a Yugoslav nationalist, assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, in Sarajevo, a series of diplomatic maneuverings led to an ultimatum from Austria-Hungary to the Kingdom of Serbia and eventually to war.

- Young Bosnia

-

A revolutionary movement active in the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina before World War I. The members were predominantly school students, primarily Serbs but also Bosniaks and Croats. There were two key ideologies promoted among the members of the group: the Yugoslavist (unification into a Yugoslavia) and the Pan-Serb (unification into Serbia).

Franz Ferdinand was an Archduke of Austria-Este, Austro-Hungarian and Royal Prince of Hungary and of Bohemia and, from 1896 until his death, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne. His assassination in Sarajevo precipitated Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war against Serbia. This caused the Central Powers (including Germany and Austria-Hungary) and Serbia’s allies to declare war on each other, starting World War I.

Franz Ferdinand was born in Graz, Austria, the eldest son of Archduke Karl Ludwig of Austria (younger brother of Franz Joseph and Maximilian) and his second wife, Princess Maria Annunciata of Bourbon-Two Sicilies. In 1875, when he was only 11 years old, his cousin Duke Francis V of Modena died, naming Franz Ferdinand his heir on condition that he add the name Este to his own. Franz Ferdinand thus became one of the wealthiest men in Austria.

In 1889, Franz Ferdinand’s life changed dramatically. His cousin Crown Prince Rudolf committed suicide at his hunting lodge in Mayerling. This left Franz Ferdinand’s father, Karl Ludwig, first in line to the throne. Ludwig died of typhoid fever in 1896. Henceforth, Franz Ferdinand was groomed to succeed him.

Assassination of Archduke Ferdinand

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, occurred on June 28, 1914, in Sarajevo when they were shot dead by Gavrilo Princip. Princip was one of a group of six assassins (five Serbs and one Bosniak) coordinated by Danilo Ilić, a Bosnian Serb and a member of the Black Hand secret society. The political objective of the assassination was to break off Austria-Hungary’s South Slav provinces so they could be combined into Yugoslavia. The Black Hand, formally Unification or Death, was a secret military society formed on May 9, 1911, by officers in the Army of the Kingdom of Serbia. with the aim of uniting all of the territories with a South Slavic majority not ruled by either Serbia or Montenegro. Its inspiration was primarily the unification of Italy in 1859–70, but also that of Germany in 1871.

The assassins’ motives were consistent with Young Bosnia, a revolutionary movement active in the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ruled by Austria-Hungary) before World War I. The members were predominantly school students, primarily Serbs but also Bosniaks and Croats. There were two key ideologies promoted among the members of the group: the Yugoslavist (unification into a Yugoslavia), and the Pan-Serb (unification into Serbia). Young Bosnia was inspired from a variety of ideas, movements, and events, such as German romanticism, anarchism, Russian revolutionary socialism, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Friedrich Nietzsche, and the Battle of Kosovo.

In 1913, Emperor Franz Joseph commanded Archduke Franz Ferdinand to observe the military maneuvers in Bosnia scheduled for June 1914. Following the maneuvers, Ferdinand and his wife planned to visit Sarajevo to open the state museum in its new premises there. Duchess Sophie, according to their oldest son, Duke Maximilian, accompanied her husband out of fear for his safety.

Franz Ferdinand was an advocate of increased federalism and widely believed to favor trialism, under which Austria-Hungary would be reorganized by combining the Slavic lands within the Austro-Hungarian empire into a third crown. A Slavic kingdom could have been a bulwark against Serb irredentism, and Ferdinand was therefore perceived as a threat by those same irredentists. Princip later stated to the court that preventing Ferdinand’s planned reforms was one of his motivations.

The day of the assassination, June 28, is the feast of St. Vitus. In Serbia, it is called Vidovdan and commemorates the 1389 Battle of Kosovo against the Ottomans, at which the Sultan was assassinated in his tent by a Serb.

The assassination of Ferdinand led directly to the First World War when Austria-Hungary subsequently issued an ultimatum to the Kingdom of Serbia, which was partially rejected. Austria-Hungary then declared war.

The assassins, the key members of the clandestine network, and the key Serbian military conspirators who were still alive were arrested, tried, convicted, and punished. Those who were arrested in Bosnia were tried in Sarajevo in October 1914. The other conspirators were arrested and tried before a Serbian court on the French-controlled Salonika Front in 1916–1917 on unrelated false charges; Serbia executed three of the top military conspirators. Much of what is known about the assassinations comes from these two trials and related records.

Assassination of Archduke Ferdinand

The first page of the edition of the Domenica del Corriere, an Italian paper, with a drawing by Achille Beltrame depicting Gavrilo Princip killing Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in Sarajevo.

Consequences

The murder of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire and his wife produced widespread shock across Europe, and there was initially much sympathy for the Austrian position. Within two days of the assassination, Austria-Hungary and Germany advised Serbia that it should open an investigation, but Secretary General to the Serbian Ministry of Foreign Affairs Slavko Gruic, replied “Nothing had been done so far and the matter did not concern the Serbian Government.” An angry exchange followed between the Austrian Chargé d’Affaires at Belgrade and Gruic.

After conducting a criminal investigation, verifying that Germany would honor its military alliance, and persuading the skeptical Hungarian Count Tisza, Austria-Hungary issued a formal letter to the government of Serbia. The letter reminded Serbia of its commitment to respect the Great Powers’ decision regarding Bosnia-Herzegovina and maintain good relations with Austria-Hungary. The letter contained specific demands aimed at preventing the publication of propaganda advocating the violent destruction of Austria-Hungary, removing the people behind this propaganda from the Serbian Military, arresting the people on Serbian soil who were involved in the assassination plot, and preventing the clandestine shipment of arms and explosives from Serbia to Austria-Hungary.

This letter became known as the July Ultimatum, and Austria-Hungary stated that if Serbia did not accept all of the demands in total within 48 hours, it would recall its ambassador from Serbia. After receiving a telegram of support from Russia, Serbia mobilized its army and responded to the letter by completely accepting point #8 demanding an end to the smuggling of weapons and punishment of the frontier officers who had assisted the assassins, and completely accepting point #10 which demanded Serbia report the execution of the required measures as they were completed. Serbia partially accepted, finessed, disingenuously answered, or politely rejected elements of the preamble and enumerated demands #1–7 and #9. The shortcomings of Serbia’s response were published by Austria-Hungary. Austria-Hungary responded by breaking diplomatic relations. This diplomatic crisis is known as the July Crisis.

The next day, Serbian reservists transported on tramp steamers on the Danube crossed onto the Austro-Hungarian side of the river at Temes-Kubin and Austro-Hungarian soldiers fired into the air to warn them off. The report of this incident was initially sketchy and reported to Emperor Franz-Joseph as “a considerable skirmish.” Austria-Hungary then declared war and mobilized the portion of its army that would face the (already mobilized) Serbian Army on July 28, 1914. Under the Secret Treaty of 1892 Russia and France were obliged to mobilize their armies if any of the Triple Alliance mobilized. Russia’s mobilization set off full Austro-Hungarian and German mobilizations. Soon all the Great Powers except Italy had chosen sides and gone to war.

Serbia Must Die!

Serbien muss sterbien! (“Serbia must die!”) This political cartoon shows an Austrian hand crushing a Serb.

29.3: Events of World War I

29.3.1: The Alliances

During the 19th century, the major European powers went to great lengths to maintain a balance of power throughout Europe, resulting in the existence of a complex network of political and military alliances throughout the continent leading up to World War I. According to some historians, this caused a localized conflict to escalate into a global war.

Learning Objective

Name the members of the two alliances that clashed in WWI

Key Points

- Starting directly after the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the Great Powers of Europe began to forge complex alliances to maintain a balance of power and peace.

- This process began with the Holy Alliance between Prussia, Russia, and Austria and the Quadruple Alliance signed by United Kingdom, Austria, Prussia, and Russia, both formed in 1815 and aimed at maintaining a stable and conservative vision for Europe.

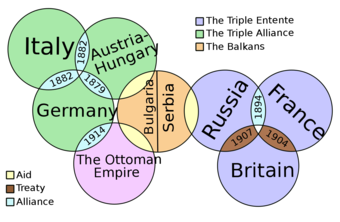

- Throughout the rest of the 19th century, various treaties and alliances were formed, including the German-Austrian treaty (1879) or Dual Alliance; the addition of Italy to the Germany and Austrian alliance in 1882, forming the “Triple Alliance”; the Franco-Russian Alliance (1894); and the “Entente Cordiale” between Britain and France (1904), which eventually included Russia and formed the Triple Entente.

- The Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente, which were renewed several times leading up to World War I, formed the two opposing sides of the war, with Italy moving over to ally with the Triple Entente after the start of the war and other nations pulled in over time.

- Historians debate how much these complex alliances contributed to the outbreak of the World War I, as the crisis between Austria-Hungary and Serbia could have been localized but quickly escalated into a global conflict despite the fact that some of the alliances, notably the Triple Entente, did not stipulate mutual defense in the case of an attack.

Key Terms

- Central Powers

-

Consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria, this was one of the two main factions during World War I (1914–18). It faced and was defeated by the Allied Powers that formed around the Triple Entente, after which it was dissolved.

- Triple Entente

-

The informal understanding linking the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland after the signing of the Anglo-Russian Entente on August 31, 1907. The understanding between the three powers, supplemented by agreements with Japan and Portugal, constituted a powerful counterweight to the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Kingdom of Italy.

- Triple Alliance

-

A secret agreement between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy formed on May 20, 1882, and renewed periodically until World War I. Germany and Austria-Hungary had been closely allied since 1879. Italy sought support against France shortly after it lost North African ambitions to the French. Each member promised mutual support in the event of an attack by any other great power.

During the 19th century, the major European powers went to great lengths to maintain a balance of power throughout Europe, resulting in the existence of a complex network of political and military alliances throughout the continent by 1900. These began in 1815 with the Holy Alliance between Prussia, Russia, and Austria. When Germany was united in 1871, Prussia became part of the new German nation. In October 1873, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck negotiated the League of the Three Emperors between the monarchs of Austria-Hungary, Russia, and Germany. This agreement failed because Austria-Hungary and Russia could not agree over Balkan policy, leaving Germany and Austria-Hungary in an alliance formed in 1879 called the Dual Alliance. This was a method of countering Russian influence in the Balkans as the Ottoman Empire continued to weaken. This alliance expanded in 1882 to include Italy, in what became the Triple Alliance.

Bismarck held Russia at Germany’s side to avoid a two-front war with France and Russia. When Wilhelm II ascended to the throne as German Emperor (Kaiser), Bismarck was compelled to retire and his system of alliances was gradually de-emphasized. For example, the Kaiser refused in 1890 to renew the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia. Two years later, the Franco-Russian Alliance was signed to counteract the force of the Triple Alliance. In 1904, Britain signed a series of agreements with France, the Entente Cordiale, and in 1907, Britain and Russia signed the Anglo-Russian Convention. While these agreements did not formally ally Britain with France or Russia, they made British entry into any future conflict involving France or Russia a possibility, and the system of interlocking bilateral agreements became known as the Triple Entente.

Interestingly, family connections pervaded these alliances, some crossing the boundaries of opposition. Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, King George V of England, and Tsar Nicholas II of Russia were cousins.

Central Powers

The Central Powers, consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria – hence also known as the Quadruple Alliance – was one of the two main factions during World War I (1914–18). It faced and was defeated by the Allied Powers that formed around the Triple Entente, after which it was dissolved.

The Central Powers consisted of the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the beginning of the war. The Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers later in 1914. In 1915, the Kingdom of Bulgaria joined the alliance. The name “Central Powers” is derived from the location of these countries; all four (including the other groups that supported them except for Finland and Lithuania) were located between the Russian Empire in the east and France and the United Kingdom in the west. Finland, Azerbaijan, and Lithuania joined them in 1918 before the war ended and after the Russian Empire collapsed.

The Central Powers’ origin was the Triple Alliance. Also known as the Triplice, this was a secret agreement between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy formed on May 20, 1882, and renewed periodically until World War I. Germany and Austria-Hungary had been closely allied since 1879. Italy sought support against France shortly after it lost North African ambitions to the French. Each member promised mutual support in the event of an attack by any other great power. The treaty provided that Germany and Austria-Hungary would assist Italy if it was attacked by France without provocation. In turn, Italy would assist Germany if attacked by France. In the event of a war between Austria-Hungary and Russia, Italy promised to remain neutral.

Shortly after renewing the Alliance in June 1902, Italy secretly extended a similar guarantee to France. By a particular agreement, neither Austria-Hungary nor Italy would change the status quo in the Balkans without previous consultation. On November 1, 1902, five months after the Triple Alliance was renewed, Italy reached an understanding with France that each would remain neutral in the event of an attack on the other.

When Austria-Hungary found itself at war in August 1914 with the rival Triple Entente, Italy proclaimed its neutrality, considering Austria-Hungary the aggressor and defaulting on the obligation to consult and agree compensations before changing the status quo in the Balkans as agreed in 1912 renewal of the Triple Alliance. Following parallel negotiation with both Triple Alliance, aimed to keep Italy neutral, and the Triple Entente, aimed to make Italy enter the conflict, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary. Carol I of Romania, through his Prime Minister Ion I. C. Brătianu, also secretly pledged to support the Triple Alliance, but he remained neutral since Austria-Hungary started the war.

Allies of WWI

The Allies of World War I were the countries that opposed the Central Powers in the First World War.

The members of the original Entente Alliance of 1907 were the French Republic, the British Empire, and the Russian Empire. Italy ended its alliance with the Central Powers, arguing that Germany and Austria-Hungary started the war and that the alliance was only defensive in nature; it entered the war on the side of the Entente in 1915. Japan was another important member. Belgium, Serbia, Greece, Montenegro, and Romania were affiliated members of the Entente.

The 1920 Treaty of Sèvres defines the Principal Allied Powers as the British Empire, French Republic, Italy, and Japan. The Allied Powers comprised, together with the Principal Allied Powers, Armenia, Belgium, Greece, Hejaz, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serb-Croat-Slovene state, and Czechoslovakia.

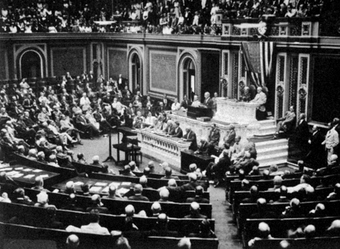

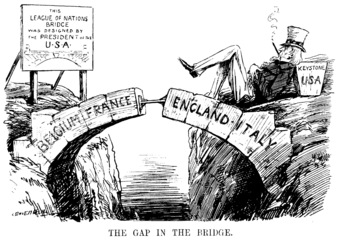

The U.S. declaration of war on Germany in April 1917 was on the grounds that Germany had violated its neutrality by attacking international shipping and the Zimmermann Telegram sent to Mexico. It declared war on Austria-Hungary in December 1917. The U.S. entered the war as an “associated power,” rather than as a formal ally of France and the United Kingdom to avoid “foreign entanglements.” Although the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria severed relations with the United States, neither declared war.

Web of Alliances

European diplomatic alignments shortly before the outbreak of WWI.

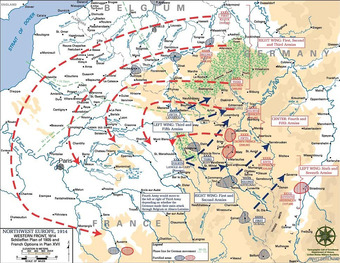

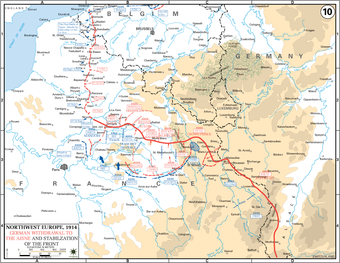

29.3.2: The Schlieffen Plan