26.1: The South American Revolutions

26.1.1: The Spread of Revolution

The Latin American Wars of Independence, which took place during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, were deeply influenced by the American and French Revolutions and resulted in the creation of a number of independent countries in Latin America.

Learning Objective

Relate the South American Revolutions to the American and French Revolutions

Key Points

- The revolutionary fervor of the 18th century, influenced by Enlightenment ideals of liberty and equality, resulted in massive political upheaval across the world, starting with the American Revolution in 1776 and the French Revolution in 1789.

- The principles expounded by the revolutionaries in Europe and their political success in overthrowing the autocratic rule of the monarchy inspired similar movements in Latin America, first in Haiti (then the French colony of Saint Domingue), whose revolution began just two years after the start of the French Revolution.

- At first, the white settler-colonists were inspired by the French Revolution to gain independent control over their colonies, but soon the revolution became centered on a slave-led rebellion against slavery and colonization, a trend that would continue throughout the America with varying degrees of success.

- Soon after the French Revolution and its resulting political instability, Napoleon Bonaparte took power, further destabilizing the Latin American colonies and leading to more revolution.

- The Peninsular War, which resulted from the Napoleonic occupation of Spain, caused Spanish Creoles in Spanish America to question their allegiance to Spain, stoking independence movements that culminated in the wars of independence, which lasted almost two decades.

- At the time of the wars of independence, there was discussion of creating a regional state or confederation of Latin American nations to protect the area’s new autonomy, but after several projects failed, the issue was not taken up again until the late 19th century.

Key Terms

- Haitian Revolution

-

A successful anti-slavery and anti-colonial insurrection that took place in the former French colony of Saint Domingue from 1791 until 1804. It affected the institution of slavery throughout the Americas. Self-liberated slaves destroyed slavery at home, fought to preserve their freedom, and with the collaboration of mulattoes, founded the sovereign state of Haiti.

- Napoleonic wars

-

A series of major conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European powers formed into various coalitions, primarily led and financed by the United Kingdom. The wars resulted from the unresolved disputes associated with the French Revolution and the Revolutionary Wars, which raged for years before concluding with the Treaty of Amiens in 1802. The resumption of hostilities the following year paved the way for more than a decade of constant warfare. These wars had profound consequences for global and European history, leading to the spread of nationalism and liberalism, the rise of the British Empire as the world’s premier power, the independence movements in Latin America and the collapse of the Spanish Empire, the fundamental reorganization of German and Italian territories into larger states, and the establishment of radically new methods in warfare.

- Libertadores

-

Refers to the principal leaders of the Latin American wars of independence from Spain and Portugal. They are named in contrast with the Conquistadors, who were so far the only Spanish/Portuguese peoples recorded in the South American history. They were largely bourgeois criollos (local-born people of European, mostly of Spanish or Portuguese, ancestry) influenced by liberalism and in most cases with military training in the metropole (mother country).

The Latin American Wars of Independence were the revolutions that took place during the late 18th and early 19th centuries and resulted in the creation of a number of independent countries in Latin America. These revolutions followed the American and French Revolutions, which had profound effects on the Spanish, Portuguese, and French colonies in the Americas. Haiti, a French slave colony, was the first to follow the United States to independence during the Haitian Revolution, which lasted from 1791 to 1804. From this Napoleon Bonaparte emerged as French ruler, whose armies set out to conquer Europe, including Spain and Portugal, in 1808.

The Peninsular War, which resulted from the Napoleonic occupation of Spain, caused Spanish Creoles in Spanish America to question their allegiance to Spain, stoking independence movements that culminated in the wars of independence, lasting almost two decades. The crisis of political legitimacy in Spain with the Napoleonic invasion sparked reaction in Spain’s overseas empire. The outcome in Spanish America was that most of the region achieved political independence and instigated the creation of sovereign nations. The areas that were most recently formed as viceroyalties were the first to achieve independence, while the old centers of Spanish power in Mexico and Peru with strong and entrenched institutions and the elites were the last to achieve independence. The two exceptions were the islands of Cuba and Puerto Rico, which along with the Philippines remained Spanish colonies until the 1898 Spanish-America War. At the same time, the Portuguese monarchy relocated to Brazil during Portugal’s French occupation. After the royal court returned to Lisbon, the prince regent, Pedro, remained in Brazil and in 1822 successfully declared himself emperor of a newly independent Brazil.

Spanish America: Hope for a Unified Latin America

The chaos of the Napoleonic wars in Europe cut the direct links between Spain and its American colonies, allowing decolonization to begin.

During the Peninsula War, Napoleon installed his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the Spanish Throne and captured King Fernando VII. Several assemblies were established after 1810 by the Criollos to recover the sovereignty and self-government based in Seven-Part Code and restore the laws of Castilian succession to rule the lands in the name of Ferdinand VII of Spain.

This experience of self-government, along with the influence of Liberalism and the ideas of the French and American Revolutions, brought about a struggle for independence led by the Libertadores. The territories freed themselves, often with help from foreign mercenaries and privateers. United States, Europe and the British Empire were neutral, aiming to achieve political influence and trade without the Spanish monopoly.

In South America, Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín led the final phase of the independence struggle. Although Bolívar attempted to keep the Spanish-speaking parts of the continent politically unified, they rapidly became independent of one another as well, and several further wars were fought, such as the Paraguayan War and the War of the Pacific. At the time, there was discussion of creating a regional state or confederation of Latin American nations to protect the area’s newly won autonomy. After several projects failed, the issue was not taken up again until the late 19th century.

A related process took place in Spain’s North and Central American colonies with the Mexican War of Independence and related struggles. Independence was achieved in 1821 by a coalition uniting under Agustín de Iturbide and the Army of the Three Guarantees. Unity was maintained for a short period under the First Mexican Empire, but within a decade the region had also split into various nations.

In 1898, in the Greater Antilles, the United States won the Spanish-American War and occupied Cuba and Puerto Rico, ending Spanish territorial control in the Americas.

Impact of the French Revolution: Haiti

The Haitian Revolution was a successful anti-slavery and anti-colonial insurrection that took place in the former French colony of Saint Domingue from 1791 until 1804. It affected the institution of slavery throughout the Americas. Self-liberated slaves destroyed slavery at home, fought to preserve their freedom, and with the collaboration of mulattoes, founded the sovereign state of Haiti.

From the beginning of colonization, white colonists and black slaves frequently came into violent conflict. The French Revolution, which began in 1789, shaped the course of the ongoing conflict in Saint-Domingue and was at first welcomed in the island. In France, the National Assembly made radical changes in French laws, and on August 26, 1789, published the Declaration of the Rights of Man, declaring all men free and equal. Wealthy whites saw it as an opportunity to gain independence from France, which would allow elite plantation-owners to take control of the island and create trade regulations that would further their own wealth and power. There were so many twists and turns in the leadership in France and so many complex events in Saint-Domingue that various classes and parties changed their alignments many times. However, the Haitian Revolution quickly became a test of the ideology of the French Revolution, as it radicalized the slavery question and forced French leaders to recognize the full meaning of their revolution.

The African population on the island began to hear of the agitation for independence by the rich European planters, the grands blancs, who resented France’s limitations on the island’s foreign trade. The Africans mostly allied with the royalists and the British, as they understood that if Saint-Domingue’s independence were to be led by white slave masters, it would probably mean even harsher treatment and increased injustice for the African population. The plantation owners would be free to operate slavery as they pleased without the existing minimal accountability to their French peers.

Saint-Domingue’s free people of color, most notably Julien Raimond, had been actively appealing to France for full civil equality with whites since the 1780s. Raimond used the French Revolution to make this the major colonial issue before the National Assembly of France. In October 1790, Vincent Ogé, another wealthy free man of color from the colony, returned home from Paris, where he had been working with Raimond. Convinced that a law passed by the French Constituent Assembly gave full civil rights to wealthy men of color, Ogé demanded the right to vote. When the colonial governor refused, Ogé led a brief insurgency in the area around Cap Français. He and an army of around 300 free blacks fought to end racial discrimination in the area. He was captured in early 1791, and brutally executed by being “broken on the wheel” before being beheaded. Ogé was not fighting against slavery, but his treatment was cited by later slave rebels as one of the factors in their decision to rise up in August 1791 and resist treaties with the colonists. The conflict up to this point was between factions of whites and between whites and free blacks. Enslaved blacks watched from the sidelines.

The Revolution in Haiti did not wait on the Revolution in France. The individuals in Haiti relied on no resolution but their own. The call for modification of society was influenced by the revolution in France, but once the hope for change found a place in the hearts of the Haitian people, there was no stopping the radical reformation that was occurring. The Enlightenment ideals and the initiation of the French Revolution were enough to inspire the Haitian Revolution, which evolved into the most successful and comprehensive slave rebellion. Just as the French were successful in transforming their society, so were the Haitians. On April 4, 1792, The French National Assembly granted freedom to slaves in Haiti and the revolution culminated in 1804; Haiti was an independent nation comprised solely of free people. The activities of the revolutions sparked change across the world. France’s transformation was most influential in Europe, and Haiti’s influence spanned across every location that continued to practice slavery. John E. Baur honors Haiti as home of the most influential revolution in history.

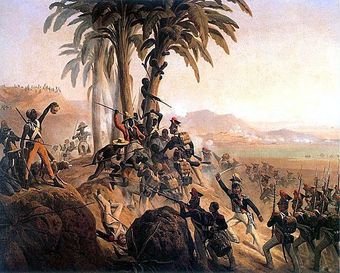

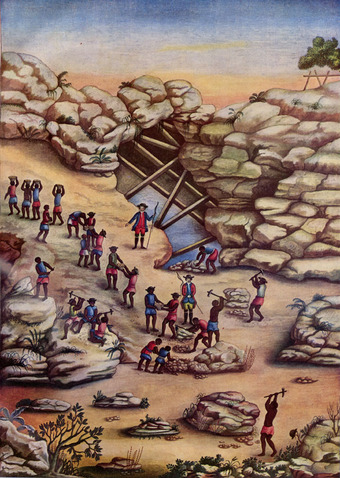

Haitian Revolution

Battle at San Domingo, a painting by January Suchodolski, depicting a struggle between Polish troops in French service and the slave rebels and freed revolutionary soldiers.

26.1.2: Simón Bolívar

Simón Bolívar was a Venezuelan military and political leader who played a leading role in the Latin American wars of independence and was a major proponent of a unified Latin America.

Learning Objective

Recall Simón Bolívar and his contributions to South American independence movements

Key Points

- The military and political career of Simón Bolívar, which included both formal service in the armies of various revolutionary regimes and actions organized by himself or in collaboration with other exiled patriot leaders from 1811 to 1830, was important in the success of the independence wars in South America.

- These wars, often under the leadership of Bolívar, resulted in the creation of several South American states out of the former Spanish colonies: the currently existing Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, and the now-defunct Gran Colombia.

- Bolívar first found success in his native Venezuela, taking advantage of the instability caused by Napoleon’s Peninsular War and leading the revolutionary forces to a victory in 1821, which resulted in the creation of an independent Venezuela.

- Throughout his military career, he also lead efforts to oust Spanish rulers from Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia.

- Bolívar was passionate about the creation of a unified Latin America, through military and economic alliances and various confederations to protect the area’s newly won autonomy, but in the end, nationalistic enterprises won out.

Key Terms

- Gran Colombia

-

A name used today for the state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 1831. It included the territories of present-day Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama, northern Peru, western Guyana, and northwest Brazil.

- caudillismo

-

A cultural and political phenomenon first appearing during the early 19th century in revolutionary Spanish America, characterized by a military land owners who possessed political power, charismatic personalities, and populist politics and created authoritarian regimes in Latin American nations.

- Creole

-

A social class in the hierarchy of the overseas colonies established by Spain in the 16th century, especially in Hispanic America, comprising the locally born people of confirmed European (primarily Spanish) ancestry. Although they were legally Spaniards, in practice, they ranked below the Iberian-born Peninsulares. Nevertheless, they had preeminence over all the other populations: Amerindians, enslaved Africans, and people of mixed descent.

- Peninsular War

-

A military conflict between Napoleon’s empire and the allied powers of Spain, Britain, and Portugal for control of the Iberian Peninsula during the Napoleonic Wars. The war started when French and Spanish armies invaded and occupied Portugal in 1807, and escalated in 1808 when France turned on Spain, its previous ally. The war on the peninsula lasted until the Sixth Coalition defeated Napoleon in 1814, and is regarded as one of the first wars of national liberation, significant for the emergence of large-scale guerrilla warfare.

El Libertador: Simón Bolívar

Simón Bolívar (July 24, 1783 – December 17, 1830) was a Venezuelan military and political leader who played a key role in the establishment of Venezuela, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Panama as sovereign states independent of Spanish rule.

Bolívar was born into a wealthy, aristocratic Creole family and like others of his day was educated abroad at a young age, arriving in Spain when he was 16 and later moving to France. While in Europe, he was introduced to the ideas of Enlightenment philosophers, which gave him the ambition to replace the Spanish as rulers. Taking advantage of the disorder in Spain prompted by the Peninsular War, Bolívar began his campaign for Venezuelan independence in 1808, appealing to the wealthy Creole population through a conservative process, and established an organized national congress within three years. Despite a number of hindrances, including the arrival of an unprecedentedly large Spanish expeditionary force, the revolutionaries eventually prevailed, culminating in a patriot victory at the Battle of Carabobo in 1821 that effectively made Venezuela an independent country.

Following this triumph over the Spanish monarchy, Bolívar participated in the foundation of the first union of independent nations in Latin America, Gran Colombia, of which he was president from 1819 to 1830. Through further military campaigns, he ousted Spanish rulers from Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia (which was named after him). He was simultaneously president of Gran Colombia (current Venezuela, Colombia, Panamá, and Ecuador) and Peru, while his second in command Antonio José de Sucre was appointed president of Bolivia. He aimed at a strong and united Spanish America able to cope not only with the threats emanating from Spain and the European Holy Alliance but also with the emerging power of the United States. At the peak of his power, Bolívar ruled over a vast territory from the Argentine border to the Caribbean Sea.

In his 21-year career, Bolívar faced two main challenges. First was gaining acceptance as undisputed leader of the republican cause. Despite claiming such a role since 1813, he began to achieve acceptance only in 1817, and consolidated his hold on power after his dramatic and unexpected victory in New Granada in 1819. His second challenge was implementing a vision to unify the region into one large state, which he believed (and most would agree, correctly) would be the only guarantee of maintaining American independence from the Spanish in northern South America. His early experiences under the First Venezuelan Republic and in New Granada convinced him that divisions among republicans, augmented by federal forms of government, only allowed Spanish American royalists to eventually gain the upper hand. Once again, it was his victory in 1819 that gave him the leverage to bring about the creation of a unified state, Gran Colombia, with which to oppose the Spanish Monarchy on the continent.

Bolívar is, along with Argentine General José de San Martín, considered one of the great heroes of the Hispanic independence movements of the early 19th century.

Simón Bolívar

A portait of Simón Bolívar by Arturo Michelena. Bolívar is considered one of the leading figures in the Latin American wars of independence.

Failed Dream of a Unified Latin America

At the end of the wars of independence (1808–1825), many new sovereign states emerged in the Americas from the former Spanish colonies. Throughout this revolutionary era, Bolívar envisioned various unions that would ensure the independence of Spanish America vis-à-vis the European powers—in particular Britain—and the expanding United States. Already in his 1815 Cartagena Manifesto, Bolívar advocated that the Spanish American provinces should present a united front to the Spanish in order to prevent being re-conquered piecemeal, though he did not yet propose a political union of any kind. During the wars of independence, the fight against Spain was marked by an incipient sense of nationalism. It was unclear what the new states that replaced the Spanish Monarchy should be. Most of those who fought for independence identified with both their birth provinces and Spanish America as a whole, both of which they referred to as their patria, a term roughly translated as “fatherland” and “homeland.”

For Bolivar, Hispanic America was the fatherland. He dreamed of a united Spanish America and in the pursuit of that purpose not only created Gran Colombia but also the Confederation of the Andes, which was to gather the latter together with Peru and Bolivia. Moreover, he envisaged and promoted a network of treaties that would hold together the newly liberated Hispanic American countries. Nonetheless, he was unable to control the centrifugal process that pushed in all directions. On January 20, 1830, as his dream fell apart, Bolívar delivered his last address to the nation, announcing that he would be stepping down from the presidency of Gran Colombia. In his speech, a distraught Bolívar urged the people to maintain the union and to be wary of the intentions of those who advocated for separation. At the time, “Colombians” referred to the people of Gran Colombia (Venezuela, New Granada, and Ecuador), not modern-day Colombia:

Colombians! Today I cease to govern you. I have served you for twenty years as soldier and leader. During this long period we have taken back our country, liberated three republics, fomented many civil wars, and four times I have returned to the people their omnipotence, convening personally four constitutional congresses. These services were inspired by your virtues, your courage, and your patriotism; mine is the great privilege of having governed you…

Colombians! Gather around the constitutional congress. It represents the wisdom of the nation, the legitimate hope of the people, and the final point of reunion of the patriots. Its sovereign decrees will determine our lives, the happiness of the Republic, and the glory of Colombia. If dire circumstances should cause you to abandon it, there will be no health for the country, and you will drown in the ocean of anarchy, leaving as your children’s legacy nothing but crime, blood, and death.

Fellow Countrymen! Hear my final plea as I end my political career; in the name of Colombia I ask you, beg you, to remain united, lest you become the assassins of the country and your own executioners.

Bolívar ultimately failed in his attempt to prevent the collapse of the union. Gran Colombia was dissolved later that year and replaced by the republics of Venezuela, New Granada, and Ecuador. Ironically, these countries were established as centralist nations and would be governed for decades this way by leaders who, during Bolívar’s last years, accused him of betraying republican principles and wanting to establish a permanent dictatorship. These separatists, among them José Antonio Páez and Francisco de Paula Santander, justified their opposition to Bolívar for this reason and publicly denounced him as a monarch.

For the rest of the 19th century and into the early 20th century, the political environment of Latin America was fraught with civil wars and characterized by a sociopolitical phenomenon known as caudillismo. This was characterized by the arrival of an authoritarian but charismatic political figure who would typically rise to power in an unconventional way, often legitimizing his right to govern through undemocratic processes. These caudillos would maintain their control primarily on the basis of a cult of personality, populist politics, and military might. On his deathbed, Bolívar envisaged the emergence of countless “caudillos” competing for the pieces of the great nation he once dreamed about.

26.1.3: Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia, a state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America, was created in 1819 by Simón Bolívar as part of his vision for a unified Latin America, but was fraught with political instability and collapsed in 1831.

Learning Objective

Identify Gran Colombia and the modern states it later became

Key Points

- As the wars of independence in Latin America were being fought, Simón Bolívar developed a vision for a unified Latin America to protect the new independence from European interests.

- Out of this vision, Gran Colombia was formed in 1819 following Bolívar’s victory against the Spanish at the Battle of Carabobo; he was elected the president.

- In its first years, Gran Colombia helped other provinces still at war with Spain become independent, adding more territories to its federation; by 1824 it had 12 administrative departments.

- The history of Gran Colombia was marked by a struggle between those who supported a centralized government with a strong presidency and those who supported a decentralized, federal form of government.

- After years of struggle between the centralists and federalists, in 1828 delegates met to create a new constitution which Bolívar proposed to base on Bolivia’s, but it was unpopular and the constitutional convention fell apart.

- In two years, Bolívar resigned as president and within a year, Gran Colombia dissolved, forming the independent states of Venezuela, Ecuador, and New Granada.

- Gran Colombia included the territories of present-day Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama, northern Peru, western Guyana, and northwest Brazil.

Key Terms

- Battle of Carabobo

-

A battle fought between independence fighters led by Venezuelan General Simón Bolívar and the Royalist forces led by Spanish Field Marshal Miguel de la Torre. Bolívar’s decisive victory at Carabobo led to the independence of Venezuela and establishment of the Republic of Gran Colombia.

- federation

-

A political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing states or regions under a central government. Typically, the self-governing status of the component states, as well as the division of power between them and the central government, is constitutionally entrenched and may not be altered by a unilateral decision of either party.

- New Granada

-

The name given on May 27, 1717, to the jurisdiction of the Spanish Empire in northern South America, corresponding to modern Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela.

Gran Colombia is a name used today for the state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 1831. It included the territories of present-day Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama, northern Peru, western Guyana, and northwest Brazil.

The first three were the successor states to Gran Colombia at its dissolution. Panama was separated from Colombia in 1903. Since Gran Colombia’s territory corresponded more or less to the original jurisdiction of the former Viceroyalty of New Granada, it also claimed the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua, the Mosquito Coast.

Its existence was marked by a struggle between those who supported a centralized government with a strong presidency and those who supported a decentralized, federal form of government.

At the same time, another political division emerged between those who supported the Constitution of Cúcuta and two groups who sought to do away with the Constitution, either in favor of breaking up the nation into smaller republics or maintaining the union but creating an even stronger presidency. The faction that favored constitutional rule coalesced around Vice-President Francisco de Paula Santander, while those who supported the creation of a stronger presidency were led by President Simón Bolívar. The two men had been allies in the war against Spanish rule, but by 1825, their differences became public and contributed to the political instability from that year onward. Gran Columbia broke apart in 1831.

History of Gran Colombia

As Bolívar made advances against the royalist forces during the Venezuelan war of independence, he began to propose the creation of various large states and confederations, inspired by Francisco de Miranda’s idea of an independent state consisting of all of Spanish America, called “Colombia,” the “American Empire,” or the “American Federation.” The aim was to ensure the independence of Spanish America and protect the area’s newly won autonomy. In 1819 Bolívar was able to successfully create a nation called “Colombia” (today referred to as Gran Colombia) out of several Spanish American provinces.

Since the new nation was quickly proclaimed after Bolívar’s unexpected victory in New Granada, its government was temporarily set up as a federal republic, made up of three departments headed by a vice-president and with capitals in the cities of cities of Bogotá (Cundinamarca Department), Caracas (Venezuela Department), and Quito (Quito Department).

The Constitution of Cúcuta was drafted in 1821 at the Congress of Cúcuta, establishing the republic’s capital in Bogotá. Bolívar and Santander were elected as the nation’s president and vice-president. A great degree of centralization was established by the assembly at Cúcuta, since several New Granadan and Venezuelan deputies of the Congress who were formerly ardent federalists now came to believe that centralism was necessary to successfully manage the war against the royalists. The departments created in 1819 were split into 12 smaller departments, each governed by an intendant appointed by the central government. Since not all of the provinces were represented at Cúcuta because many areas of the nation remained in royalist hands, the congress called for a new constitutional convention to meet in ten years.

In its first years, Gran Colombia helped other provinces still at war with Spain to become independent: all of Venezuela except Puerto Cabello was liberated at the Battle of Carabobo, Panama joined the federation in November 1821, and the provinces of Pasto, Guayaquil, and Quito in 1822. The Gran Colombian army later consolidated the independence of Peru in 1824. Bolívar and Santander were re-elected in 1826.

As the war against Spain came to an end in the mid-1820s, federalist and regionalist sentiments that were suppressed for the sake of the war arose once again. There were calls for a modification of the political division, and related economic and commercial disputes between regions reappeared. Ecuador had important economic and political grievances. Since the end of the 18th century, its textile industry suffered because cheaper textiles were being imported. After independence, Gran Colombia adopted a low-tariff policy, which benefited agricultural regions such as Venezuela. Moreover, from 1820 to 1825, the area was ruled directly by Bolívar because of the extraordinary powers granted to him. His top priority was the war in Peru against the royalists, not solving Ecuador’s economic problems.

The strongest calls for a federal arrangement came from Venezuela, where there was strong federalist sentiment among the region’s liberals, many of whom had not fought in the war of independence but supported Spanish liberalism in the previous decade and now allied themselves with the conservative Commandant General of the Department of Venezuela, José Antonio Páez, against the central government.

In 1826, Venezuela came close to seceding from Gran Colombia. That year, Congress began impeachment proceedings against Páez, who resigned his post on April 28 but reassumed it two days later in defiance of the central government.

In November, two assemblies met in Venezuela to discuss the future of the region, but no formal independence was declared at either. That same month, skirmishes broke out between the supporters of Páez and Bolívar in the east and south of Venezuela. By the end of the year, Bolívar was in Maracaibo preparing to march into Venezuela with an army, if necessary. Ultimately, political compromises prevented this. In January, Bolívar offered the rebellious Venezuelans a general amnesty and the promise to convene a new constitutional assembly before the ten-year period established by the Constitution of Cúcuta, and Páez backed down and recognized Bolívar’s authority. The reforms, however, never fully satisfied the different political factions in Gran Colombia, and no permanent consolidation was achieved. The instability of the state’s structure was now apparent to all.

In 1828, the new constitutional assembly, the Convention of Ocaña, began its sessions. At its opening, Bolívar again proposed a new constitution based on the Bolivian one, but this suggestion continued to be unpopular. The convention fell apart when pro-Bolívar delegates walked out rather than sign a federalist constitution. After this failure, Bolívar believed that by centralizing his constitutional powers he could prevent the separatists from bringing down the union. He ultimately failed to do so. As the collapse of the nation became evident in 1830, Bolívar resigned from the presidency. Internal political strife between the different regions intensified even as General Rafael Urdaneta temporarily took power in Bogotá, attempting to use his authority to ostensibly restore order but actually hoping to convince Bolívar to return to the presidency and the nation to accept him. The federation finally dissolved in the closing months of 1830 and was formally abolished in 1831. Venezuela, Ecuador, and New Granada came to exist as independent states.

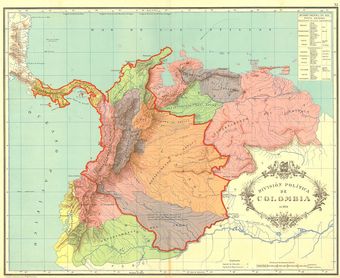

Gran Colombia

A map of Gran Colombia showing the 12 departments created in 1824 and territories disputed with neighboring countries.

26.1.4: José de San Martín

José de San Martín was one of the prime leaders of Latin America’s successful struggle for freedom from the Spanish Empire, commanding crucial military campaigns that led to independence for Argentina, Chile, and Peru.

Learning Objective

Compare José de San Martín’s efforts to Bolívar’s

Key Points

- José de San Martín, along with Simón Bolívar, was one of the most important leaders of the Latin American independence movements.

- His military leadership was crucial in the wars of independence in Argentina, Chile, and Peru.

- Born in what became Argentina, San Martín mostly grew up in Spain, taking part in the Peninsular War against Napoleon.

- He left Spain and joined the Argentine War of Independence in 1811, a choice debated by historians.

- He provided a much-needed boost to the revolution, mustering the Army of the Andes, whose crossing of the Andes was instrumental in freeing Argentina and Chile from Spanish rule.

- From there he went to Peru, where he fought for several years in collaboration and conflict with Simón Bolívar. He left suddenly in 1822 for France, leaving the remainder of the war for independence to be led by Bolívar, who succeeded against the Spanish forces in 1824.

Key Terms

- Crossing of the Andes

-

One of the most important feats in the Argentine and Chilean wars of independence, in which a combined army of Argentine soldiers and Chilean exiles invaded Chile, leading to Chile’s liberation from Spanish rule. The crossing of the Andes was a major step in the strategy devised by José de San Martín to defeat the royalist forces at their stronghold of Lima, Viceroyalty of Perú, and secure the Spanish American independence movements.

- Army of the Andes

-

A military force created by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (Argentina) and mustered by general José de San Martín in his campaign to free Chile from the Spanish Empire. In 1817, it crossed the Andes Mountains from the Argentine province of Cuyo (at the current-day province of Mendoza, Argentina), and succeeded in dislodging the Spanish from the country.

José de San Martín was an Argentine general and the prime leader of the southern part of South America’s successful struggle for independence from the Spanish Empire. Born in Yapeyú, Corrientes, in modern-day Argentina, he left his mother country at the early age of seven to study in Málaga, Spain.

In 1808, after taking part in the Peninsular War against Napoleon’s France, San Martín contacted South American supporters of independence from Spain. In 1812, he set sail for Buenos Aires and offered his services to the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, present-day Argentina. After the Battle of San Lorenzo and time commanding the Army of the North during 1814, he organized a plan to defeat the Spanish forces that menaced the United Provinces from the north, using an alternative path to the Viceroyalty of Peru. This objective first involved the establishment of a new army, the Army of the Andes, in Cuyo Province, Argentina. From there, he led the Crossing of the Andes to Chile and triumphed at the Battle of Chacabuco and the Battle of Maipú (1818), thus liberating Chile from royalist rule. Then he sailed to attack the Spanish stronghold of Lima, Peru.

On July 12, 1821, after seizing partial control of Lima, San Martín was appointed Protector of Peru, and Peruvian independence was officially declared on July 28. On July 22, after a closed-door meeting with fellow libertador Simón Bolívar at Guayaquil, Ecuador, Bolívar took over the task of fully liberating Peru. San Martín unexpectedly left the country and resigned the command of his army, excluding himself from politics and the military, and moved to France in 1824. The details of the July 22 meeting would be a subject of debate by later historians.

San Martín is regarded as a national hero of Argentina and Peru, and together with Bolívar, one of the Liberators of Spanish South America. The Order of the Liberator General San Martín (Orden del Libertador General San Martín), created in his honor, is the highest decoration conferred by the Argentine government.

Wars of Independence: Argentina, Chile, Peru

San Martín entered the Argentine War of Independence about a year after it started. The reasons that he left Spain in 1811 to join the Spanish American wars of independence as a patriot remain contentious among historians. The action would seem contradictory and out of character, because if the patriots were waging an independentist and anti-Hispanic war, then he would be a traitor or deserter. There are a variety of explanations by different historians. Some argue that he returned because he missed South America, and the war of independence justified changing sides to support it. Other contend that the wars in the Americas were not initially separatist but between supporters of absolutism and liberalism, which thus maintains a continuity between San Martín’s actions in Spain and in Latin America.

The Argentine War of Independence started with the May Revolution and other military campaigns with mixed success. The undesired outcomes of the Paraguay and Upper Peru campaigns led the Junta (the provisional government after the May Revolution) to be replaced by an executive Triumvirate in September 1811.

A few days after his arrival in Buenos Aires, San Martín was interviewed by the First Triumvirate. They appointed him a lieutenant colonel of cavalry and asked him to create a cavalry unit, as Buenos Aires did not have good cavalry. He began to organize the Regiment of Mounted Grenadiers with Alvear and Zapiola. As Buenos Aires lacked professional military leaders, San Martín was entrusted with the protection of the whole city, but kept focused in the task of building the military unit. A year later the Triumvirate was renewed and San Martín was promoted to colonel.

San Martín came up with a plan: organize an army in Mendoza, cross the Andes to Chile, and move to Peru by sea, all while another general defended the north frontier. This would place him in Peru without crossing the harsh terrain of Upper Peru, where two campaigns had already been defeated. To advance this plan, he requested the governorship of the Cuyo province, which was accepted.

San Martín began immediately to organize the Army of the Andes. He drafted all citizens who could bear arms and all slaves from ages 16 to 30, requested reinforcements to Buenos Aires, and reorganized the economy for war production. San Martín proposed that the country declare independence immediately, before the crossing. That way, they would be acting as a sovereign nation and not as a mere rebellion, but the proposal never was accepted. Needing even more soldiers, San Martín extended the emancipation of slaves to ages 14 to 55, and even allowed them to be promoted to higher military ranks. He proposed a similar measure at the national level, but Pueyrredón encountered severe resistance. He included the Chileans who escaped Chile after the disaster of Rancagua, and organized them in four units: infantry, cavalry, artillery, and dragoons. At the end of 1816, the Army of the Andes had 5,000 men, 10,000 mules, and 1,500 horses. San Martin organized military intelligence, propaganda, and disinformation to confuse the royalist armies (such as the specific routes taken in the Andes), boost the national fervor of his army, and promote desertion among the royalists.

In early 1817, San Martín led the Crossing of the Andes into Chile, obtaining a decisive victory at the battle of Chacabuco on February 17, which allowed the exiled Chilean leader Bernardo O’Higgins to enter Santiago de Chile unopposed and install a new independent government. In December 1817, a popular referendum was set up to decide about the Independence of Chile. On February 18, 1818, the first anniversary of the battle of Chacabuco, Chile declared its independence from the Spanish Crown.

From there, San Martín took the Army of the Andes to fight in Peru. To begin the liberation of Peru, Argentina and Chile signed a treaty on February 5, 1819, to prepare for the invasion. General José de San Martín believed that the liberation of Argentina wouldn’t be secure until the royalist stronghold in Peru was defeated. Peru had armed forces nearly four times the strength of those of San Martín. With this disparity, San Martín tried to avoid battles. He tried instead to divide the enemy forces in several locations, as during the Crossing of the Andes, and trap the royalists with a pincer movement with either reinforcements of the Army of the North from the South or the army of Simón Bolívar from the North. He also tried to promote rebellions and insurrection within the royalist ranks, and promised the emancipation of any slaves that deserted their Peruvian masters and joined the army of San Martín. When he reached Lima, San Martín invited all of the populace of Lima to swear oath to the Independence cause. The signing of the Act of Independence of Peru was held on July 15, 1821. San Martín became the leader of the government, even though he did not want to lead. He was appointed Protector of Peru. After several years of fighting, San Martín abandoned Peru in September 1822 and left the whole command of the Independence movement to Simon Bolivar. The Peruvian War culminated in 1824 with the defeat of the Spanish Empire in the battles of Junin and Ayacucho.

Guayaquil Conference

The Guayaquil Conference was a meeting that took place on July 26, 1822, in Guayaquil, Ecuador, between José de San Martín and Simón Bolívar, to discuss the future of Perú (and South America in general). San Martín arrived in Guayaquil on July 25, where he was enthusiastically greeted by Bolívar. However, the two men could not come to an agreement, despite their common goals and mutual respect, even when San Martín offered to serve under Bolívar. Both men had very different ideas about how to organize the governments of the countries that they had liberated. Bolívar was in favor of forming a series of republics in the newly independent nations, whereas San Martín preferred the European system of rule and wanted to put monarchies in place. San Martín was also in favor of placing a European prince in power as King of Peru when it was liberated. The conference, consequently, was a failure, at least for San Martín.

San Martín, after meeting with Bolívar for several hours on July 26, stayed for a banquet and ball given in his honor. Bolívar proposed a toast to “the two greatest men in South America: the general San Martín and myself,” whereas San Martín drank to “the prompt conclusion of the war, the organization of the different Republics of the continent and the health of the Liberator of Colombia.” After the conference, San Martín abdicated his powers in Peru and returned to Argentina. Soon afterward, he left South America entirely and retired in France.

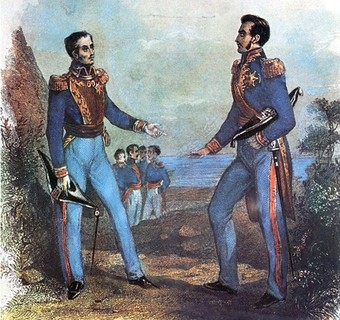

Guayaquil Conference

The conference between Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín. The real conference took place inside an office, and not in the countryside as the portrait suggests.

26.2: Brazilian Independence

26.2.1: Portugese Colonization of Brazil

Colonial Brazil comprises the period from 1500 with the arrival of the Portuguese until 1815 when Brazil was elevated to a kingdom. It was characterized by the development of sugar and gold production, slave labor, and conflicts with the French and Dutch.

Learning Objective

Assess the Portuguese colonization of Brazil

Key Points

- In 1494, the two kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula (Portugal and Spain) divided the New World between them in the Treaty of Tordesillas

- In 1500, navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral landed in what is now Brazil and claimed it in the name of King Manuel I of Portugal.

- The Portuguese identified brazilwood as a valuable red dye and an exploitable product and attempted to force indigenous groups in Brazil to cut the trees, but at first gave little attention to the area.

- Over time, the Portuguese realized that some European countries, especially France, were also sending excursions to Brazil to extract brazilwood, and the Portuguese crown decided to send large missions to take possession of the land by setting up hereditary captaincies, which were largely a failure.

- Starting in the 16th century, sugarcane production became the base of Brazilian economy and society, with the use of slaves on large plantations to make sugar for export to Europe.

- Throughout most of the colonial period, the Portuguese settlers fought conflicts with the French and the Dutch for control over the territory.

- The discovery of gold in the early 18th century ushered in a gold rush, bringing in many new European settlers.

Key Terms

- Dutch West India Company

-

A chartered company of Dutch merchants. On June 3, 1621, it was granted a charter for a trade monopoly in the West Indies (meaning the Caribbean) by the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands and given jurisdiction over the Atlantic slave trade, Brazil, the Caribbean, and North America. The intended purpose of the charter was to eliminate competition, particularly Spanish or Portuguese, between the various trading posts established by the merchants. The company became instrumental in the Dutch colonization of the Americas.

- Treaty of Tordesillas

-

A treaty signed on June 7, 1494, that divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between Portugal and the Crown of Castile (Spain) along a meridian 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands off the west coast of Africa. This line of demarcation was about halfway between the Cape Verde islands (already Portuguese) and the islands entered by Christopher Columbus on his first voyage (claimed for Castile and León), named in the treaty as Cipangu and Antilia (Cuba and Hispaniola). It created the Tordesillas Meridian, dividing the world between those two kingdoms. All land discovered or to be discovered east of that meridian was to be the property of Portugal, and everything to the west of it went to Spain.

- engenhos

-

A colonial-era Portuguese term for a sugar cane mill and the associated facilities.

European Discovery and Early Colonization of Brazil

The Portuguese “discovery” of Brazil was preceded by a series of treaties between the kings of Portugal and Castile, following Portuguese sailings down the coast of Africa to India and the voyages to the Caribbean of the Genoese mariner sailing for Castile, Christopher Columbus. The most decisive of these treaties was the Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in 1494, that created the Tordesillas Meridian, dividing the world between those two kingdoms. All land discovered or to be discovered east of that meridian was to be the property of Portugal, and everything to the west of it went to Spain.

The Tordesillas Meridian divided South America into two parts, leaving a large chunk of land to be exploited by the Spaniards. The Treaty of Tordesillas was one of the most decisive events in all Brazilian history, since it alone determined that a portion of South America would be settled by Portugal instead of Spain. The present extent of Brazil’s coastline is almost exactly that defined by the Treaty of Madrid, which was approved in 1750.

On April 22, 1500, during the reign of King Manuel I, a fleet led by navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral landed in Brazil and took possession of the land in the name of the king. Although it is debated whether previous Portuguese explorers had already been in Brazil, this date is widely and politically accepted as the day of the discovery of Brazil by Europeans. Álvares Cabral was leading a large fleet of 13 ships and more than 1,000 men following Vasco da Gama’s way to India, around Africa. The place where Álvares Cabral arrived is now known as Porto Seguro (“safe harbor”) in Northeastern Brazil.

After the voyage of Álvares Cabral, the Portuguese concentrated their efforts on the lucrative possessions in Africa and India and showed little interest in Brazil. Between 1500 and 1530, relatively few Portuguese expeditions came to the new land to chart the coast and obtain brazilwood, which the Portuguese had identified as a valuable commodity upon arrival and from where Brazil gets its name. In Europe, this wood was used to produce a valuable dye to give color to luxury textiles. To extract brazilwood from the tropical rainforest, the Portuguese and other Europeans relied on the work of the natives, who initially labored in exchange for European goods like mirrors, scissors, knives, and axes.

In this early stage of the colonization of Brazil and also later, the Portuguese frequently relied on the help of Europeans who lived together with the indigenous peoples and knew their languages and culture. The most famous of these were João Ramalho, who lived among the Guaianaz tribe near today’s São Paulo, and Diogo Álvares Correia, nicknamed Caramuru, who lived among the Tupinambá natives near today’s Salvador da Bahia.

Colonial Brazil

Portuguese map by Lopo Homem (c. 1519) showing the coast of Brazil and natives extracting brazilwood, as well as Portuguese ships.

Colonial Brazil

Portugal’s relative lack of interest allowed traders, pirates, and privateers of several countries to poach profitable brazilwood in lands claimed by Portugal. Over time, the Portuguese realized that some European countries, especially France, were also sending excursions to the land to extract brazilwood. Worried about foreign incursions and hoping to find mineral riches, the Portuguese crown decided to send large missions to take possession of the land and combat the French.

In 1530, an expedition led by Martim Afonso de Sousa arrived in Brazil to patrol the entire coast, ban the French, and create the first colonial villages like São Vicente on the coast. The Portuguese crown devised a system to effectively occupy Brazil without paying the costs. Through the hereditary Captaincies system, Brazil was divided into strips of land that were donated to Portuguese noblemen, who were in turn responsible for the occupation and administration of the land and answered to the king. The system was a failure with only four lots successfully occupied: Pernambuco, São Vicente (later called São Paulo), Captaincy of Ilhéus, and Captaincy of Porto Seguro. The captaincies gradually reverted to the Crown and became provinces and eventually states of the country.

Starting in the 16th century, sugarcane grown on plantations called engenhos along the northeast coast became the base of Brazilian economy and society, with the use of slaves on large plantations to make sugar for export to Europe. At first, settlers tried to enslave the natives as labor to work the fields. The initial exploration of Brazil’s interior was largely due to paramilitary adventurers, the bandeirantes, who entered the jungle in search of gold and Native slaves. However, colonists were unable to sustainably enslave Natives, and Portuguese land owners soon imported millions of slaves from Africa. Mortality rates for slaves in sugar and gold enterprises were very high, and there were often not enough females or proper conditions to replenish the slave population. Still, Africans became a substantial section of Brazilian population, and long before the end of slavery in 1888, they began to merge with the European Brazilian population through interracial marriage.

During the first 150 years of the colonial period, attracted by the vast natural resources and untapped land, other European powers tried to establish colonies in several parts of Brazilian territory in defiance of the Treaty of Tordesillas. French colonists tried to settle in present-day Rio de Janeiro from 1555 to 1567 (the so-called France Antarctique episode), and in present-day São Luís from 1612 to 1614 (the so-called France Équinoxiale). Jesuits arrived early and established Sao Paulo, evangelizing the natives. These native allies of the Jesuits assisted the Portuguese in driving out the French.

The unsuccessful Dutch intrusion into Brazil was longer-lasting and more troublesome to Portugal. Dutch privateers began by plundering the coast; they sacked Bahia in 1604, and even temporarily captured the capital Salvador. From 1630 to 1654, the Dutch set up more permanently in the northwest and controlled a long stretch of the coast most accessible to Europe, without penetrating the interior. But the colonists of the Dutch West India Company in Brazil were in a constant state of siege. After several years of open warfare, the Dutch withdrew by 1654. Little French and Dutch cultural and ethnic influence remained of these failed attempts.

The discovery of gold in the early 18th century was met with great enthusiasm by Portugal, which had an economy in disarray following years of wars against Spain and the Netherlands. A gold rush quickly ensued, with people from other parts of the colony and Portugal flooding the region in the first half of the 18th century.

The Napoleonic Wars in Europe, especially the Peninsular War and its resulting treaties, would reshape the political structure of Brazil in the early 19th century from a colony of Portugal to the Kingdom of Brazil.

26.2.2: Brazil’s Exports

During the first 300 years of Brazilian colonial history, the economic exploitation of the territory was based on brazilwood extraction (16th century), sugar production (16th-18th centuries), and finally on gold and diamond mining (18th century).

Learning Objective

List Brazil’s economic power and role in the Portuguese Empire

Key Points

- The Portuguese colony of Brazil was centered upon a series of commodity productions: first brazilwood extraction, then sugar production, and finally gold and diamond mining.

- Initially, colonists were heavily dependent on indigenous labor, often through capture and coercion, during the early phases of settlement, subsistence farming, and brazilwood production.

- The importation of African slaves began midway through the 16th century, but the enslavement of indigenous peoples continued well into the 17th and 18th centuries.

- During the Atlantic slave trade era, Brazil imported more African slaves than any other country, with an estimated 4.9 million slaves from Africa coming to Brazil from 1501 to 1866.

- Slave labor was the driving force behind the growth of the sugar economy in Brazil, and sugar was the primary export of the colony from 1600–1650.

- Gold and diamond deposits were discovered in Brazil in 1690, which sparked an increase in the importation of African slaves to power this newly profitable market.

- Gold production declined towards the end of the 18th century, beginning a period of relative stagnation of the Brazilian hinterland.

Key Terms

- Triangular trade

-

A historical term indicating trade among three ports or regions, especially the transatlantic slave trade. This operated from the late 16th to early 19th centuries, carrying slaves, cash crops, and manufactured goods between West Africa, Caribbean or American colonies, and the European colonial powers, with the northern colonies of British North America, especially New England, sometimes taking over the role of Europe.

- Xica da Silva

-

A Brazilian woman who became famous for becoming rich and powerful despite being born into slavery. Her life has been a source of inspiration for many works in television, film, theater, and literature. She is popularly known as the slave who became a queen.

- brazilwood

-

A genus of flowering plants in the legume family, Fabaceae. This plant has a dense, orange-red heartwood that takes a high shine, and it is the premier wood used to make bows for stringed instruments. The wood also yields a red dye called brazilin, which oxidizes to brazilein. Starting in the 16th centuries, this tree became highly valued in Europe and quite difficult to get.

During the first 300 years of Brazilian colonial history, the economic exploitation of the territory was based on brazilwood extraction (16th century), sugar production (16th–18th centuries), and finally gold and diamond mining (18th century). Slaves, especially those brought from Africa, provided most of the working force of the Brazilian export economy after a brief period of Indian slavery. The boom and bust economic cycles were linked to export products. Brazil’s sugar age, with the development of plantation slavery (merchants serving as middle men between production sites, Brazilian ports, and Europe) was undermined by the growth of the sugar industry in the Caribbean on islands that European powers had seized from Spain. Gold and diamonds were discovered and mined in southern Brazil through the end of the colonial era. Brazilian cities were largely port cities and the colonial administrative capital was moved several times in response to the rise and fall of export products’ importance.

Brazilwood Production

After European arrival, the land’s major export was a type of tree the traders and colonists called pau-Brasil (Latin for wood red like an ember) or brazilwood from whence the country got its name. This large tree (Caesalpinia echinata) has a trunk that yields a prized red dye, and was nearly wiped out as a result of exploitation. Starting in the 16th centuries, brazilwood became highly valued in Europe and quite difficult to get. A related wood from Asia, sappanwood, was traded in powder form and used as a red dye in the manufacture of luxury textiles, such as velvet, in high demand during the Renaissance.

When Portuguese navigators discovered present-day Brazil on April 22, 1500, they immediately saw that brazilwood was extremely abundant along the coast and in its hinterland along the rivers. In a few years, a hectic and very profitable operation for felling and shipping all the brazilwood logs they could get was established as a crown-granted Portuguese monopoly. The rich commerce that soon followed stimulated other nations to try to harvest and smuggle brazilwood contraband out of Brazil and corsairs to attack loaded Portuguese ships in order to steal their cargo. For example, the unsuccessful attempt in 1555 of a French expedition led by Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon, vice-admiral of Brittany and corsair under the King, to establish a colony in present-day Rio de Janeiro (France Antarctique) was motivated in part by the bounty generated by economic exploitation of brazilwood.

The Sugar Age (1530–1700)

Since the initial attempts to find gold and silver failed, the Portuguese colonists adopted an economy based on the production of agricultural goods to be exported to Europe. Tobacco, cotton and other crops were produced, but sugar became by far the most important Brazilian colonial product until the early 18th century. The first sugarcane farms were established in the mid-16th century and were the key for the success of the captaincies of São Vicente and Pernambuco, leading sugarcane plantations to quickly spread to other coastal areas in colonial Brazil. Initially, the Portuguese attempted to utilize Indian slaves for sugar cultivation, but shifted to the use of black African slave labor.

The period of sugar-based economy (1530 – c. 1700) is known as the sugar age in Brazil. The development of the sugar complex occurred over time with a variety of models. The dependencies of the farm included a casa-grande (big house) where the owner of the farm lived with his family, and the senzala, where the slaves were kept.

Portugal owned several commercial facilities in Western Africa, where slaves were bought from African merchants. These slaves were then sent by ship to Brazil, chained and in crowded conditions. The idea of using African slaves in colonial farms was also adopted by other European colonial powers in tropical regions of America (Spain in Cuba, France in Haiti, the Netherlands in the Dutch Antilles, and England in Jamaica).

The Portuguese attempted to severely restrict colonial trade, meaning that Brazil was only allowed to export and import goods from Portugal and other Portuguese colonies. Brazil exported sugar, tobacco, cotton, and native products and imported from Portugal wine, olive oil, textiles, and luxury goods – the latter imported by Portugal from other European countries. Africa played an essential role as the supplier of slaves, and Brazilian slave traders in Africa frequently exchanged cachaça, a distilled spirit derived from sugarcane, and shells for slaves. This comprised what is now known as the triangular trade between Europe, Africa and the Americas during the colonial period.

Merchants during the sugar age were crucial to the economic development of the colony as the link between the sugar production areas, coastal Portuguese cities, and Europe. Merchants initially came from many nations, including Germany, Italy, and modern-day Belgium, but Portuguese merchants came to dominate the trade in Brazil.

Even though Brazilian sugar had a reputation for quality, the industry faced a crisis during the 17th and 18th centuries when the Dutch and the French started producing sugar in the Antilles, located much closer to Europe, causing sugar prices to fall.

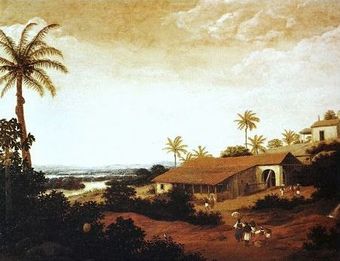

The Sugar Age

View of a sugar-producing farm (engenho) in colonial Pernambuco by Dutch painter Frans Post (17th century).

Gold Rush

The discovery of gold was met with great enthusiasm by Portugal, which had an economy in disarray following years of wars against Spain and the Netherlands. A gold rush quickly ensued, with people from other parts of the colony and Portugal flooding the region in the first half of the 18th century. The large portion of the Brazilian inland where gold was extracted became known as the Minas Gerais (General Mines). Gold mining in this area became the main economic activity of colonial Brazil during the 18th century. In Portugal, the gold was mainly used to pay for industrialized goods (textiles, weapons) obtained from countries like England and especially during the reign of King John V, to build magnificent Baroque monuments like the Convent of Mafra. Apart from gold, diamond deposits were also found in 1729 around the village of Tijuco, now Diamantina. A famous figure in Brazilian history of this era was Xica da Silva, a slave woman who had a long term relationship in Diamantina with a Portuguese official; the couple had 13 children and she died a rich woman.

Minas Gerais was the gold mining center of Brazil during the 18th century. Slave labor was generally used for the workforce. The discovery of gold in the area caused a huge influx of European immigrants and the government decided to bring in bureaucrats from Portugal to control operations. They set up numerous bureaucracies, often with conflicting duties and jurisdictions. The officials generally proved unequal to the task of controlling this highly lucrative industry. In 1830, the Saint John d’El Rey Mining Company, controlled by the British, opened the largest gold mine in Latin America. The British brought in modern management techniques and engineering expertise. Located in Nova Lima, the mine produced ore for 125 years.

Gold production declined towards the end of the 18th century, beginning a period of relative stagnation of the Brazilian hinterland.

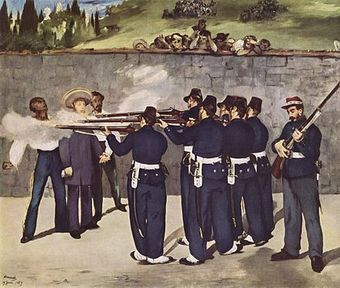

Diamond Mining

Slaves mine for diamonds in Minas Gerais (ca. 1770s). Gold and diamond deposits were discovered in Brazil in 1690, which sparked an increase in the importation of African slaves to power this newly profitable market.

26.2.3: Constitutionalist Movement in Portugal

In 1820, 13 years after the Portuguese king fled to Brazil during the Napoleonic Wars, the Constitutionalist Revolution erupted in the city of Porto and quickly and peacefully spread to the rest of the country, resulting in the return of the Portuguese crown to Europe and the declaration of Brazil’s independence from Portugal in 1822.

Learning Objective

Describe the ties between the Constitutionalist Movement and Brazilian Independence

Key Points

- In 1807, at the time of the first invasion of Portugal by Napoleon’s forces, the King of Portugal, João VI, fled to Brazil.

- When French forces were finally defeated in Europe in 1815, King João decided to continue ruling from Brazil, founding the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves, leaving a strong British presence in Portugal.

- Many people resented British influence and began a movement to reestablish the monarchy in Portugal, specifically a liberal, constitutional monarchy.

- In 1820, the constitutionalists rose up in revolution, created a constitution, and forced the return of the Portuguese King.

- King João returned to Portugal in April 1821, leaving behind his son and heir, Prince Dom Pedro, to rule Brazil as his regent.

- On September 7, 1822, Prince Dom Pedro declared Brazil’s independence from Portugal, founding the Empire of Brazil, which led to a two-year war of independence.

- Formal recognition came with a treaty signed by both Brazil and Portugal in late 1825.

Key Terms

- Brazilian war of independence

-

A war waged between the newly independent Empire of Brazil and United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves which had just undergone the Liberal Revolution of 1820. It lasted from February 1822, when the first skirmishes took place, to March 1824, when the last Portuguese garrison of Montevideo surrendered to Commander Sinian Kersey.

- United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil, and the Algarves

-

A monarchy formed by the elevation of the Portuguese colony of Brazil to the status of a kingdom and by the simultaneous union of that Kingdom of Brazil with the Kingdom of Portugal and the Kingdom of the Algarves, constituting a single state consisting of three kingdoms. It was formed in 1815 after the transfer of the Portuguese Court to Brazil during the Napoleonic invasions of Portugal and continued to exist for about one year after the return of the Court to Europe. It was de facto dissolved in 1822 when Brazil proclaimed its independence.

- Constitutionalist Revolution

-

A Portuguese political revolution that erupted in 1820. It began with a military insurrection in the city of Porto, in northern Portugal, that quickly and peacefully spread to the rest of the country. The Revolution resulted in the return in 1821 of the Portuguese Court to Portugal from Brazil, where it had fled during the Peninsular War, and initiated a constitutional period in which the 1822 Constitution was ratified and implemented.

Napoleonic Wars and Constitutionalist Revolution

From 1807 to 1811, Napoleonic French forces invaded Portugal three times. During the invasion of Portugal (1807), the Portuguese royal family fled to Brazil, establishing Rio de Janeiro as the de facto capital of Portugal. From Brazil, the Portuguese king João VI ruled his trans-Atlantic empire for 13 years.

The capital’s move to Rio de Janeiro accentuated the economic, institutional, and social crises in mainland Portugal, which was administered by English commercial and military interests under William Beresford’s rule in the absence of the monarch. The influence of liberal ideals was strengthened by the aftermath of the war, the continuing impact of the American and French revolutions, discontent under absolutist government, and the general indifference shown by the Portuguese regency for the plight of its people.

This also had the side effect of creating within Brazil many of the institutions required to exist as an independent state; most importantly, it freed the country to trade with other nations at will. After Napoleon’s army was finally defeated in 1815, to maintain the capital in Brazil and allay Brazilian fears of being returned to colonial status, King João VI of Portugal raised the de jure status of Brazil to an equal, integral part of a United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil, and the Algarves, rather than a mere colony. It enjoyed this status for the next seven years.

Following the defeat of the French forces, Portugal experienced a prolonged period of political turmoil in which many sought greater self-rule for the Portuguese people. Eventually this unrest put an end to the king’s long stay in Brazil, when his return to Portugal was demanded by the revolutionaries.

Even though the Portuguese participated in the defeat of the French, the country found itself virtually a British protectorate. The officers of the Portuguese Army resented British control of the Portuguese armed forces. After Napoleon’s definite defeat in 1815, a clandestine Supreme Regenerative Council of Portugal and the Algarve was formed in Lisbon by army officers and freemasons, headed by General Gomes Freire de Andrade—Grand Master of the Grande Oriente Lusitano and former general under Napoleon until his defeat in 1814—with the objective to end British control of the country and promote “salvation and independence.”

In 1820 the Constitutionalist Revolution erupted in Portugal. The movement initiated by the liberal constitutionalists resulted in the meeting of the Cortes (or Constituent Assembly) that would create the kingdom’s first constitution. The Cortes demanded the return of King João VI, who had been living in Brazil since 1808. The revolution began with a military insurrection in the city of Porto, in northern Portugal, that quickly and peacefully spread to the rest of the country. The Revolution resulted in the return in 1821 of the Portuguese Court to Portugal from Brazil, where it had fled during the Peninsular War, and initiated a constitutional period in which the 1822 Constitution was ratified and implemented. The revolutionaries also sought to restore Portuguese exclusivity in the trade with Brazil, reverting Brazil to the status of a colony. It was officialy reduced to a “Principality of Brazil,” instead of the Kingdom of Brazil, which it had been for the past five years. The movement’s liberal ideas had an important influence on Portuguese society and political organization in the 19th century.

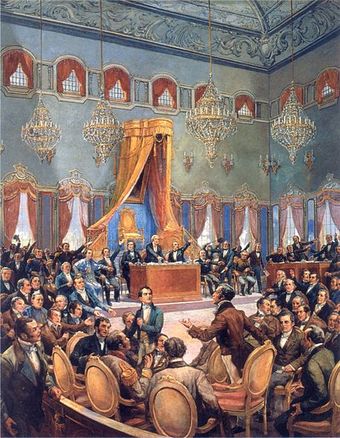

The Constitutionalists

The General and Extraordinary Cortes of the Portuguese Nation that wrote and approved the first Constitution. This constitutional assembly was composed of diplomatic functionaries, merchants, agrarian burghers, and university-educated representatives who were usually lawyers.

Brazilian Independence

King João returned to Portugal in April 1821, leaving behind his son and heir, Prince Dom Pedro, to rule Brazil as his regent. The Portuguese government immediately moved to revoke the political autonomy that Brazil had been granted since 1808. The threat of losing their limited control over local affairs ignited widespread opposition among Brazilians. José Bonifácio de Andrada, along with other Brazilian leaders, convinced Pedro to declare Brazil’s independence from Portugal on September 7, 1822. On October 12, the prince was acclaimed Pedro I, first Emperor of the newly created Empire of Brazil, a constitutional monarchy. The declaration of independence was opposed throughout Brazil by armed military units loyal to Portugal. The ensuing Brazilian war of independence was fought across the country, with battles in the northern, northeastern, and southern regions. The war lasted from February 1822, when the first skirmishes took place, to March 1824, when the last Portuguese garrison of Montevideo surrendered to Commander Sinian Kersey. It was fought on land and sea and involved both regular forces and civilian militia. Independence was recognized by Portugal in August 1825.

26.2.4: The Brazilian Empire

The Empire of Brazil, founded in 1822 when the prince regent of Portugal, Pedro I, declared its independence from Portugal, was a relatively stable and democratic constitutional monarchy that saw several wars and the abolition of slavery in 1888.

Learning Objective

Summarize the breadth and structure of the Brazilian Empire

Key Points

- Brazil was one of only three modern states in the Americas to have its own indigenous monarchy (the other two were Mexico and Haiti) for a period of almost 90 years.

- In 1808, the Portuguese court, fleeing from Napoleon’s invasion of Portugal during the Peninsular War, moved the government apparatus to its then-colony, Brazil, establishing themselves in the city of Rio de Janeiro from where the Portuguese king ruled his huge empire for 15 years.

- When the king left Brazil to return to Portugal in 1821, his elder son, Pedro I, stayed in his stead as regent of Brazil.

- One year later, Pedro stated the reasons for the secession of Brazil from Portugal and led the Independence War. He instituted a constitutional monarchy in Brazil, assuming its head as Emperor Pedro I.

- Also known as “Dom Pedro I” after his abdication in 1831 for political incompatibilities (disliked both by the landed elites who thought him too liberal and the intellectuals who felt he was not liberal enough), he left for Portugal, leaving behind his five-year-old son as Emperor Pedro II. This left the country ruled by regents between 1831 and 1840.

- This period was beset by rebellions of various motivations and political instability.

- After this period, Pedro II was declared of age and assumed his full prerogatives, leading Brazil into a period of peace and stability.

- Although there was no desire for a change in the form of government among most Brazilians, the Emperor was overthrown in a sudden coup d’état that had almost no support outside a clique of military leaders who desired a republic headed by a dictator.

- The reign of Pedro II and the Brazilian Empire came to an unusual end—he was overthrown while highly regarded by the people and at the pinnacle of his popularity. Some of his accomplishments were soon brought to naught as Brazil slipped into a long period of weak governments, dictatorships, and constitutional and economic crises.

Key Terms

- bicameral parliament

-

A legislature in which the legislators are divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses. Often, the members of the two chambers are elected or selected using different methods that vary from country to country.

- Pedro II

-

The second and last ruler of the Empire of Brazil, reigning for over 58 years. Inheriting an empire on the verge of disintegration, he turned Portuguese-speaking Brazil into an emerging power in the international arena. The nation grew distinguished from its Hispanic neighbors on account of its political stability, zealously guarded freedom of speech, respect for civil rights, vibrant economic growth, and especially its government: a functional, representative parliamentary monarchy.

- Pedro I

-

Nicknamed “the Liberator,” he was the founder and first ruler of the Empire of Brazil. He reigned briefly over Portugal.

- First Brazilian Republic

-

The period of Brazilian history from 1889 to 1930. It ended with a military coup, also known as the Brazilian Revolution of 1930, that installed Getúlio Vargas as a dictator.

Early Years

The Empire of Brazil was a 19th-century state that broadly comprised the territories of modern Brazil and Uruguay. Its government was a representative parliamentary constitutional monarchy under the rule of Emperors Dom Pedro I and his son Dom Pedro II. A colony of the Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil became the seat of the Portuguese colonial Empire in 1808 when the Portuguese prince regent, later King Dom João VI, fled from Napoleon’s invasion of Portugal and established himself and his government in the Brazilian city of Rio de Janeiro. João VI later returned to Portugal, leaving his eldest son and heir, Pedro, to rule the Kingdom of Brazil as regent. On September 7, 1822, Pedro declared the independence of Brazil and after waging a successful war against his father’s kingdom, was acclaimed on October 12 as Pedro I, the first Emperor of Brazil. The new country was huge but sparsely populated and ethnically diverse.

Unlike most of the neighboring Hispanic American republics, Brazil had political stability, vibrant economic growth, constitutionally guaranteed freedom of speech, and respect for civil rights of its subjects, albeit with legal restrictions on women and slaves, the latter regarded as property and not citizens. The empire’s bicameral parliament was elected under comparatively democratic methods for the era, as were the provincial and local legislatures. This led to a long ideological conflict between Pedro I and a sizable parliamentary faction over the role of the monarch in the government.

He also faced other obstacles. The unsuccessful Cisplatine War against the neighboring United Provinces of the Río de la Plata in 1828 led to the secession of the province of Cisplatina (later Uruguay). In 1826, despite his role in Brazilian independence, Pedro I became the king of Portugal; he immediately abdicated the Portuguese throne in favor of his eldest daughter. Two years later, she was usurped by Pedro I’s younger brother Miguel. Unable to deal with both Brazilian and Portuguese affairs, Pedro I abdicated his Brazilian throne on April 7, 1831, and immediately departed for Europe to restore his daughter to the Portuguese throne.

Pedro II