24.1: The Congress of Vienna

24.1.1: The Balance of Power

The Concert of Europe was a system of dispute resolution adopted by the major conservative powers of Europe to maintain their power, oppose revolutionary movements, weaken the forces of nationalism, and uphold the balance of power.

Learning Objective

Define the Balance of Power

Key Points

- As the Napoleonic Wars came to close in the second decade of the 19th century, the Great Powers of Europe (Britain, Prussia, Russia and Austria) started planning for the postwar world.

- To bring about a balance of power in Europe and prevent further conflict, they developed what became known as the Concert of Europe, beginning with the Congress of Vienna.

- The Congress of Vienna dissolved the Napoleonic world and attempted to restore the monarchies Napoleon had overthrown.

- The Congress was the first occasion in history where on a continental scale, national representatives came together to formulate treaties instead of relying mostly on messages between the several capitals.

- The Concert of Europe, despite later changes and diplomatic breakdowns a few decades later, formed the basic framework for European international politics until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

Key Terms

- Concert of Europe

-

Also known as the Congress System or the Vienna System after the Congress of Vienna, a system of dispute resolution adopted by the major conservative powers of Europe to maintain their power, oppose revolutionary movements, weaken the forces of nationalism, and uphold the balance of power.

- Great Powers

-

A sovereign state recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. They characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power influence, which may cause middle or small powers to consider the Great Powers’ opinions before taking actions of their own.

- balance of power

-

A theory in international relations that suggests that national security is enhanced when military capability is distributed so that no one state is strong enough to dominate all others. If one state becomes much stronger than others, the theory predicts it will take advantage of its strength and attack weaker neighbors, thereby providing an incentive for those threatened to unite in a defensive coalition.

Congress of Vienna

As the four major European powers (Britain, Prussia, Russia, and Austria) opposing the French Empire in the Napoleonic Wars saw Napoleon’s power collapsing in 1814, they started planning for the postwar world. The Treaty of Chaumont of March 1814 reaffirmed decisions that would be ratified by the more important Congress of Vienna of 1814–15. The Congress of Vienna was the first of a series of international meetings that came to be known as the Concert of Europe, an attempt to forge a peaceful balance of power in Europe. It served as a model for later organizations such as the League of Nations in 1919 and the United Nations in 1945. They included the establishment of a confederated Germany, the division of French protectorates and annexations into independent states, the restoration of the Bourbon kings of Spain, the enlargement of the Netherlands to include what in 1830 became modern Belgium, and the continuation of British subsidies to its allies. The Treaty of Chaumont united the powers to defeat Napoleon and became the cornerstone of the Concert of Europe, which formed the balance of power for the next two decades. The basic tenet of the European balance of power is that no single European power should be allowed to achieve hegemony over a substantial part of the continent and that this is best curtailed by having a small number of ever-changing alliances contend for power.

The Congress of Vienna dissolved the Napoleonic world and attempted to restore the monarchies Napoleon had overthrown, ushering in an era of reaction. Under the leadership of Metternich, the prime minister of Austria (1809–48) and Lord Castlereagh, the foreign minister of Great Britain (1812–22), the Congress set up a system to preserve the peace. Under the Concert of Europe, the major European powers—Britain, Russia, Prussia, Austria, and (after 1818) France—pledged to meet regularly to resolve differences. The goal was not simply to restore old boundaries but to resize the main powers so they could balance each other and remain at peace. The leaders were conservatives with little use for republicanism or revolution, both of which threatened to upset the status quo in Europe. This plan was the first of its kind in European history and seemed to promise a way to collectively manage European affairs and promote peace.

The Congress resolved the Polish–Saxon crisis at Vienna and the question of Greek independence at Laibach. Three major European congresses took place. The Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle (1818) ended the occupation of France. The others were meaningless as each nation realized the Congresses were not to their advantage, as disputes were resolved with a diminishing degree of effectiveness.

The Congress was the first occasion in history where, on a continental scale, national representatives came together to formulate treaties instead of relying mostly on messages between the several capitals. The Congress of Vienna settlement, despite later changes, formed the framework for European international politics until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

Conservative Order

The Conservative Order is a term applied to European political history after the defeat of Napoleon in 1815. From 1815 to 1830 a conscious program by conservative statesmen, including Metternich and Castlereagh, was put in place to contain revolution and revolutionary forces by restoring old orders, particularly previous ruling aristocracies.

Britain, Prussia, Russia, and Austria renewed their commitment to prevent any restoration of Bonapartist power and agreed to meet regularly in conferences to discuss their common interests. This period contains the time of the Holy Alliance, a military agreement. The Concert of Europe was the political framework that grew out of the Quadruple Alliance in November 1815.

The goal of the conservatives at the Congress, led by Prince Klemens von Metternich of Austria, was to reestablish peace and stability in Europe. To accomplish this, a new balance of power had to be established. Metternich and the other four represented states sought to do this by restoring old ruling families and creating buffer zones between major powers. To contain the still powerful French, the House of Orange-Nassau was put on the throne in the Netherlands, which formerly comprised the Dutch Republic and the Austrian Netherlands (Belgium). To the southeast of France, Piedmont (officially part of the kingdom of Sardinia) was enlarged. The Bourbon dynasty was restored to France and Spain as well as a return of other legitimate rulers to the Italian states. And to contain the Russian empire, Poland was divided up between Austria, Prussia, and Russia.

Concert of Europe

The Concert of Europe, also known as the Congress System or the Vienna System after the Congress of Vienna, was a System of dispute resolution adopted by the major conservative powers of Europe to maintain their power, oppose revolutionary movements, weaken the forces of nationalism, and uphold the balance of power. It grew out of Congress of Vienna. It operated in Europe from the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1815) to the early 1820s.

The Concert of Europe was founded by the powers of Austria, Prussia, the Russian Empire, and the United Kingdom, who were the members of the Quadruple Alliance that defeated Napoleon and his First French Empire. In time, France was established as a fifth member of the Concert. At first, the leading personalities of the system were British foreign secretary Lord Castlereagh, Austrian Chancellor Klemens von Metternich, and Tsar Alexander I of Russia. Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord of France was largely responsible for quickly returning that country to its place alongside the other major powers in international diplomacy.

The Concert of Europe had no written rules or permanent institutions, but at times of crisis any of the member countries could propose a conference. Meetings of the Great Powers during this period included: Aix-la-Chapelle (1818), Carlsbad (1819), Troppau (1820), Laibach (1821), Verona (1822), London (1832), and Berlin (1878).

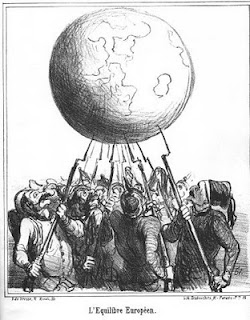

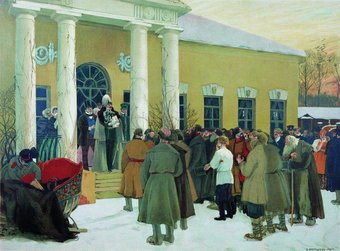

Honore Daumier, L’Equilibre Europea (1866)

The basic tenet of the European balance of power that reigned from 1814 to WWI is that no single European power should be allowed to achieve hegemony over a substantial part of the continent and that this is best curtailed by having a small number of ever-changing alliances contend for power.

24.1.2: Participants of the Congress

The leading participants of the Congress of Vienna were British foreign secretary Lord Castlereagh, Austrian Chancellor Klemens von Metternich, and Tsar Alexander I of Russia, all of whom had a reactionary, conservative vision for Europe after the Napoleonic Wars, favoring stability and the status quo over liberal progress.

Learning Objective

Identify the participants in the Congress of Vienna and their representatives

Key Points

- The objective of the Congress of Vienna was to provide a long-term peace plan for Europe by settling critical issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars.

- The leading personalities of the Congress were British foreign secretary Lord Castlereagh, Austrian Chancellor Klemens von Metternich, and Tsar Alexander I of Russia.

- These three leaders in the Congress are known for their conservatism, aimed at creating lasting peace and maintaining the status quo and opposed to liberal progress and nationalism.

- This conservative agenda has been heavily criticized by many historians who argue that it stood in the way of progress and created the conditions for World War I.

- Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord of France was largely responsible for quickly returning France to its place alongside the other major powers in international diplomacy after their defeat in the Napoleonic Wars.

- Virtually every state in Europe had a delegation in Vienna – more than 200 states and princely houses were represented at the Congress.

Key Terms

- Napoleonic Wars

-

A series of major conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European powers formed into various coalitions, primarily led and financed by the United Kingdom. War broke out as a continuation of the French Revolution, which had plunged the European continent into war since 1792.

- reactionary

-

A person who holds political views that favor a return to the status quo ante, the previous political state of society, which they believe possessed characteristics (discipline, respect for authority, etc.) that are negatively absent from the contemporary status quo of a society.

- Klemens von Metternich

-

A politician and statesman of Rhenish extraction and one of the most important diplomats of his era, serving as the Austrian Empire’s Foreign Minister from 1809 and Chancellor from 1821 until the liberal revolutions of 1848 forced his resignation. He led the Austrian delegation at the Congress of Vienna that divided post-Napoleonic Europe amongst the major powers.

The Congress of Vienna was a conference of ambassadors of European states chaired by Austrian statesman Klemens Wenzel von Metternich and held in Vienna from November 1814 to June 1815, though the delegates had arrived and were already negotiating by late September 1814. The objective of the Congress was to provide a long-term peace plan for Europe by settling critical issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. In a technical sense, the “Congress of Vienna” was not properly a Congress: it never met in plenary session, and most of the discussions occurred in informal, face-to-face sessions among the Great Powers of Austria, Britain, France, Russia, and sometimes Prussia, with limited or no participation by other delegates.

Major Participants of the Congress

The Congress functioned through formal meetings such as working groups and official diplomatic functions; however, a large portion was conducted informally at salons, banquets, and balls.

Austria was represented by Prince Klemens von Metternich, the Foreign Minister, and by his deputy, Baron Johann von Wessenberg. As the Congress’s sessions were in Vienna, Emperor Francis was kept closely informed. Metternich was one of main architects of the balance of power in Europe and approached the matter from a perspective of conservatism. He was a staunch opponent of liberalism and nationalism, favoring instead the preservation of the status quo in the face of the revolutionary challenge. He was also wary of Russian dominance. Critics of his diplomatic agenda paint him as the man who prevented Austria and the rest of central Europe from “developing along normal liberal and constitutional lines.” Had Metternich not stood in the way of “progress,” some argue, Austria might have reformed and dealt better with its problems of nationality, and the First World War might never have happened.

Great Britain was represented first by its Foreign Secretary, Viscount Castlereagh, then by the Duke of Wellington, after Castlereagh’s return to England in February 1815. In the last weeks it was headed by the Earl of Clancarty after Wellington left to face Napoleon during the Hundred Days. Castlereagh, a conservative like Metternich, had a vision of long-term peace in Europe that united efforts of the great powers. At the same time he was watchful of Britain’s mercantile and imperial interests. He saw that a harsh treaty based on vengeance and retaliation against France would fail, and anyway the conservative Bourbons were back in power. He employed his diplomatic skills to block harsh terms. Bringing France back into diplomatic balance was important to his vision of peace.

Tsar Alexander I controlled the Russian delegation formally led by the foreign minister, Count Karl Robert Nesselrode. The tsar had three main goals: to gain control of Poland, to form a league that could intervene and stop revolutions against monarchies and traditionalism, and to promote the peaceful coexistence of European nations. He succeeded in forming the Holy Alliance (1815), based on monarchism and anti-secularism, and formed to combat any threat of revolution or republicanism.

Prussia was represented by Prince Karl August von Hardenberg, the Chancellor, and the diplomat and scholar Wilhelm von Humboldt. King Frederick William III of Prussia was also in Vienna, playing his role behind the scenes. Hardenberg was more liberal than the other main participants, and earlier in his career implemented a variety of liberal reforms. To him and Baron von Stein, Prussia was indebted for improvements in its army system, the abolition of serfdom and feudal burdens, the opening of civil service to all classes, and the complete reform of the educational system. However, by the time of the Congress of Vienna, the zenith of his influence, if not of his fame, was passed. In diplomacy he was no match for Metternich, whose influence soon overshadowed his own. During his late career he acquiesced to reactionary policies along the lines of the rest of the Congress.

France, the “fifth” power, was represented by its foreign minister, Talleyrand, as well as the Minister Plenipotentiary the Duke of Dalberg. Talleyrand had already negotiated the Treaty of Paris (1814) for Louis XVIII of France; the king, however, distrusted him and was also secretly negotiating with Metternich by mail. Talleyrand played a major role at the Congress, where he negotiated a favorable settlement for France while undoing Napoleon’s conquests. He sought a negotiated secure peace so as to perpetuate the gains of the French revolution.

Initially, the representatives of the four victorious powers hoped to exclude the French from serious participation in the negotiations, but Talleyrand skillfully managed to insert himself into “her inner councils” in the first weeks of negotiations. He allied himself to a Committee of Eight lesser powers (including Spain, Sweden, and Portugal) to control the negotiations. Once Talleyrand was able to use this committee to make himself a part of the inner negotiations, he then left it, once again abandoning his allies.

Congress Secretary Friedrich von Gentz reported, “The intervention of Talleyrand and Labrador has hopelessly upset all our plans. Talleyrand protested against the procedure we have adopted and soundly [be]rated us for two hours. It was a scene I shall never forget.”

Other Participants

- Spain – Marquis Pedro Gómez de Labrador

- Kingdom of Portugal and the Algarves – Plenipotentiaries: Pedro de Sousa Holstein, Count of Palmela; António de Saldanha da Gama, Count of Porto Santo; Joaquim Lobo da Silveira.

- Sweden – Count Carl Löwenhielm

- Denmark – Count Niels Rosenkrantz, foreign minister. King Frederick VI was also present in Vienna.

- The Netherlands – Earl of Clancarty, the British Ambassador at the Dutch court, and Baron Hans von Gagern

- Switzerland – Every canton had its own delegation. Charles Pictet de Rochemont from Geneva played a prominent role.

- The Papal States – Cardinal Ercole Consalvi

- Republic of Genoa – Marquise Agostino Pareto, Senator of the Republic

- Bavaria – Maximilian Graf von Montgelas

- Württemberg – Georg Ernst Levin von Wintzingerode

- Hanover, then in a personal union with the British crown – Georg Graf zu Münster.

- Mecklenburg-Schwerin – Leopold von Plessen

Virtually every state in Europe had a delegation in Vienna – more than 200 states and princely houses were represented at the Congress. In addition, there were representatives of cities, corporations, religious organizations (for instance, abbeys), and special interest groups (e.g. a delegation representing German publishers, demanding a copyright law and freedom of the press). The Congress was noted for its lavish entertainment: according to a famous joke it did not move, but danced.

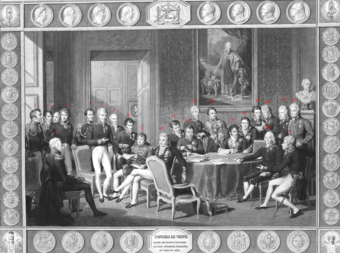

Participants of the Congress of Vienna

1. Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington 2. Joaquim Lobo Silveira, 7th Count of Oriola 3. António de Saldanha da Gama, Count of Porto Santo 4. Count Carl Löwenhielm 5. Jean-Louis-Paul-François, 5th Duke of Noailles 6. Klemens Wenzel, Prince von Metternich 7. André Dupin 8. Count Karl Robert Nesselrode 9. Pedro de Sousa Holstein, 1st Count of Palmela 10. Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh 11. Emmerich Joseph, Duke of Dalberg 12. Baron Johann von Wessenberg 13. Prince Andrey Kirillovich Razumovsky 14. Charles Stewart, 1st Baron Stewart 15. Pedro Gómez Labrador, Marquis of Labrador 16. Richard Le Poer Trench, 2nd Earl of Clancarty 17. Wacken (Recorder) 18. Friedrich von Gentz (Congress Secretary) 19. Baron Wilhelm von Humboldt 20. William Cathcart, 1st Earl Cathcart 21. Prince Karl August von Hardenberg 22. Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord 23. Count Gustav Ernst von Stackelberg

24.1.3: Territorial Changes in Europe

The goal of the Congress of Vienna was not simply to restore old boundaries but to resize the main powers so they could balance each other and remain at peace.

Learning Objective

Outline the borders that changed in Europe after the Congress of Vienna

Key Points

- The Final Act, embodying all the separate treaties created at and around the Congress of Vienna, was signed on June 9, 1815, ushering in major territorial changes to Europe to create a balance of power between nations.

- France lost all of its territorial conquests from the Napoleonic Wars.

- Russia gained much of Poland, while Prussia added smaller German states in the west, Swedish Pomerania, and 40% of the Kingdom of Saxony.

- The Congress created a Confederated Germany, a consolidation of the nearly 300 states of the Holy Roman Empire (dissolved in 1806) into a much less complex system of 39 states.

- The Italian peninsula became a mere “geographical expression” divided into seven parts: Lombardy-Venetia, Modena, Naples-Sicily, Parma, Piedmont-Sardinia, Tuscany, and the Papal States under the control of different powers.

Key Terms

- Holy Roman Empire

-

A multi-ethnic complex of territories in central Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806. The largest territory of the empire after 962 was the Kingdom of Germany, though it also came to include the Kingdom of Bohemia, the Kingdom of Burgundy, the Kingdom of Italy, and numerous other territories.

- Hundred Days

-

The period between Napoleon’s return from exile on the island of Elba to Paris on March 20, 1815, and the second restoration of King Louis XVIII on July 8, 1815, (a period of 111 days). Napoleon returned during the Congress of Vienna. On March 13, seven days before Napoleon reached Paris, the powers at the Congress of Vienna declared him an outlaw. On March 25, Austria, Prussia, Russia, and the United Kingdom, members of the Seventh Coalition, bound themselves to put 150,000 men each into the field to end his rule. This set the stage for the last conflict in the Napoleonic Wars, the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo, the restoration of the French monarchy for the second time, and the permanent exile of Napoleon to the distant island of Saint Helena, where he died in May 1821.

- Duchy

-

A country, territory, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess. The term is used almost exclusively in Europe, where in the present day there is no sovereign duchy (i.e. with the status of a nation state) left.

The Congress of Vienna (1814–1815) dissolved the Napoleonic world and attempted to restore the monarchies Napoleon had overthrown, ushering in an era of conservatism. Under the leadership of Metternich, the prime minister of Austria (1809–48) and Lord Castlereagh, the foreign minister of Great Britain (1812–22), the Congress set up a system to preserve the peace. The goal was not simply to restore old boundaries but to resize the main powers so they could balance each other.

France lost all its recent conquests, while Prussia, Austria, and Russia made major territorial gains. Prussia added smaller German states in the west, Swedish Pomerania, and 40% of the Kingdom of Saxony; Austria gained Venice and much of northern Italy. Russia gained parts of Poland. The new Kingdom of the Netherlands had been created just months before and included formerly Austrian territory that in 1830 became Belgium.

Territorial Changes

The Final Act, embodying all the separate treaties, was signed on June 9, 1815, (a few days before the Battle of Waterloo).

The Congress’s principal results were the enlargements of Russia, which gained most of the Duchy of Warsaw (Poland), and Prussia, which acquired the district of Poznań, Swedish Pomerania, Westphalia, and the northern Rhineland. The consolidation of Germany from the nearly 300 states of the Holy Roman Empire (dissolved in 1806) into a much less complex system of 39 states (four of which were free cities) was confirmed. These states formed a loose German Confederation under the leadership of Austria and Prussia.

The Congress also confirmed France’s loss of the territories annexed between 1795–1810, which had already been settled by the Treaty of Paris.

Representatives at the Congress agreed to numerous other territorial changes. By the Treaty of Kiel, Norway was ceded by the king of Denmark-Norway to the king of Sweden. This sparked the nationalist movement which led to the establishment of the Kingdom of Norway on May 17, 1814, and the subsequent personal union with Sweden. Austria gained Lombardy-Venetia in Northern Italy, while much of the rest of North-Central Italy went to Habsburg dynasties (the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Duchy of Modena, and the Duchy of Parma).

The Papal States were restored to the Pope. The Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia was restored to its mainland possessions and gained control of the Republic of Genoa. In Southern Italy, Napoleon’s brother-in-law, Joachim Murat, was originally allowed to retain his Kingdom of Naples, but his support of Napoleon in the Hundred Days led to the restoration of the Bourbon Ferdinand IV to the throne.

A large United Kingdom of the Netherlands was formed for the Prince of Orange, including both the old United Provinces and the formerly Austrian-ruled territories in the Southern Netherlands. Other, less important territorial adjustments included significant gains for the German Kingdoms of Hanover (which gained East Frisia from Prussia and various other territories in Northwest Germany) and Bavaria (which gained the Rhenish Palatinate and territories in Franconia). The Duchy of Lauenburg was transferred from Hanover to Denmark, and Prussia annexed Swedish Pomerania. Switzerland was enlarged and Swiss neutrality was established. Swiss mercenaries had played a significant role in European wars for several hundred years; the Congress intended to put a stop to these activities permanently.

During the wars, Portugal lost its town of Olivença to Spain and moved to have it restored. Portugal is historically Britain’s oldest ally and with British support succeeded in having the reincorporation of Olivença decreed in Article 105 of the Final Act, which stated that the Congress “understood the occupation of Olivença to be illegal and recognized Portugal’s rights.” Portugal ratified the Final Act in 1815 but Spain would not sign, and this became the most important hold-out against the Congress of Vienna. Deciding in the end that it was better to become part of Europe than to stand alone, Spain finally accepted the Treaty on May 7, 1817; however, Olivença and its surroundings were never returned to Portuguese control and this question remains unresolved.

Great Britain received parts of the West Indies at the expense of the Netherlands and Spain and kept the former Dutch colonies of Ceylon and the Cape Colony as well as Malta and Heligoland. Under the Treaty of Paris, Britain obtained a protectorate over the United States of the Ionian Islands and the Seychelles.

Congress of Vienna

The national boundaries within Europe set by the Congress of Vienna, 1815

24.1.4: Diplomatic Consequences of the Congress of Vienna

Despite the efforts of the Great Powers of Europe to prevent conflict and war with the Congress of Vienna, in many ways the Congress system failed by 1823. The rest of the 19th century was marked by more revolutionary fervor, more war, and the rise of nationalism.

Learning Objective

Describe the diplomatic consequences of the Congress of Vienna

Key Points

- The Congress of Vienna and the resulting Concert of Europe, aimed at creating a stable and peaceful Europe after the Napoleonic Wars, succeeded in creating a balance of power and peaceful diplomacy for almost a decade.

- The Great Powers, the main participants of the Congress, also formed the Holy Alliance and the Quadruple Alliance, treaties to further the conservative vision of the Congress.

- However, by 1823 the diplomatic system developed by the Congress by which the main powers could propose a conference to solve a crisis had failed.

- In 1818, the British decided not to become involved in continental issues that did not directly affect them and did not support the Tsar in his vision to prevent revolution.

- No Congress was called to restore the old system during the great revolutionary upheavals of 1848; thus, nationalism and liberalism began to triumph over the conservatism of the Congress system.

- The diplomatic alliances that formed out of the Congress were shattered during the Crimean War, in which Russia was defeated by the other Powers.

Key Terms

- Quadruple Alliance

-

A treaty signed in Paris on November 20, 1815, by the great powers of United Kingdom, Austria, Prussia, and Russia. It renewed the use of the Congress System, which advanced European international relations.

- Holy Alliance

-

A coalition created by the monarchist great powers of Russia, Austria, and Prussia. It was created with the intention to restrain republicanism and secularism in Europe in the wake of the devastating French Revolutionary Wars.

- Crimean War

-

A military conflict fought from October 1853 to March 1856 in which the Russian Empire lost to an alliance of France, Britain, the Ottoman Empire, and Sardinia. The immediate cause involved the rights of Christian minorities in the Holy Land, part of the Ottoman Empire.

International Relations and Diplomacy

With the Concert of Europe, the territorial boundaries laid down at the Congress of Vienna were maintained, and even more importantly there was an acceptance of the theme of balance with no major aggression. Otherwise, the Congress system failed by 1823. In 1818 the British decided not to become involved in continental issues that did not directly affect them. They rejected the plan of Tsar Alexander I to suppress future revolutions. The Concert system fell apart as the common goals of the Great Powers were replaced by growing political and economic rivalries. Artz says the Congress of Verona in 1822 “marked the end.” There was no Congress called to restore the old system during the great revolutionary upheavals of 1848, which called for revision of the Congress of Vienna’s frontiers along national lines.

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Spring of Nations, People’s Spring, Springtime of the Peoples, or the Year of Revolution, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in European history. These diverse revolutionary movements were in opposition to the conservative agenda of the Congress of Vienna and marked a major challenge to its vision for a stable Europe.

The revolutions were essentially democratic in nature, with the aim of removing the old feudal structures and creating independent national states. The revolutionary wave began in France in February and immediately spread to most of Europe and parts of Latin America. Over 50 countries were affected, but with no coordination or cooperation between their respective revolutionaries. According to Evans and von Strandmann (2000), some of the major contributing factors were widespread dissatisfaction with political leadership, demands for more participation in government and democracy, demands for freedom of press, demands made by the working class, the upsurge of nationalism, and the regrouping of established governmental forces.

The uprisings were led by shaky ad hoc coalitions of reformers, the middle classes, and workers, which did not hold together for long. Tens of thousands of people were killed and many more forced into exile. Significant lasting reforms included the abolition of serfdom in Austria and Hungary, the end of absolute monarchy in Denmark, and the introduction of parliamentary democracy in the Netherlands. The revolutions were most important in France, the Netherlands, the states that would make up the German Empire in the late 19th and early 20th century, Italy, and the Austrian Empire.

Before 1850 Britain and France dominated Europe, but by the 1850s they had become deeply concerned by the growing power of Russia and Prussia. The Crimean War of 1854–55 and the Italian War of 1859 shattered the relations among the Great Powers in Europe. Victory over Napoleonic France left the British without any serious international rival, other than perhaps Russia in central Asia.

The Crimean War (1853–56) was fought between Russia, who tried expanding its influence in the Balkans, against an alliance of Great Britain, France, Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire. Russia was defeated.

In 1851, France under Napoleon III compelled the Ottoman government to recognize it as the protector of Christian sites in the Holy Land. Russia denounced this claim, since it claimed to be the protector of all Eastern Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire. France sent its fleet to the Black Sea; Russia responded with its own show of force. In 1851, Russia sent troops into the Ottoman provinces of Moldavia and Wallachia. Britain, now fearing for the security of the Ottoman Empire, sent a fleet to join with the French, expecting the Russians would back down.

Diplomatic efforts failed. The Sultan declared war against Russia in October 1851. Following an Ottoman naval disaster in November, Britain and France declared war against Russia. Most of the battles took place in the Crimean peninsula, which the Allies finally seized. London, shocked to discover that France was secretly negotiating with Russia to form a postwar alliance to dominate Europe, dropped its plans to attack St. Petersburg and instead signed a one-sided armistice with Russia that achieved almost none of its war aims.

The Treaty of Paris, signed March 30, 1856, ended the war. It admitted the Ottoman Empire to the Concert of Europe, and the Powers promised to respect its independence and territorial integrity. Russia gave up a little land and relinquished its claim to a protectorate over the Christians in the Ottoman domains. The Black Sea was demilitarized and an international commission was set up to guarantee freedom of commerce and navigation on the Danube River.

After 1870 the creation and rise of the German Empire as a dominant nation restructured the European balance of power. For the next twenty years, Otto von Bismarck managed to maintain this balance by proposing treaties and creating many complex alliances between the European nations, such as the Triple Alliance.

Congress of Paris

Diplomats at the Congress of Paris, 1856, settling the Crimean War; painting by Edouard Louis Dubufe.

The Holy Alliance and the Quadruple Alliance

As an extension of the vision of the Congress of Vienna, the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian and Russian Empires formed the Holy Alliance (September 26, 1815) to preserve Christian social values and traditional monarchism. The intention of the alliance was to restrain republicanism and secularism in Europe in the wake of the devastating French Revolutionary Wars, and the alliance nominally succeeded in this until the Crimean War (1853–1856). Every member of the coalition promptly joined the Alliance, except for the United Kingdom, a constitutional monarchy with a more liberal political philosophy.

Britain did however ratify the Quadruple Alliance, signed on the same day as the Second Peace Treaty of Paris (November 20, 1815) by the same three powers that signed the Holy Alliance on September 26, 1815. It renewed the use of the Congress System, which advanced European international relations. The alliance first formed in 1813 to counter France and promised aid to each other. It became the Quintuple Alliance when France joined in 1818.

Much debate has occurred among historians as to which treaty was more influential in the development of international relations in Europe in the two decades following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. In the opinion of historian Tim Chapman, the differences are somewhat academic as the powers were not bound by the terms of the treaties and many of them intentionally broke the terms if it suited them.

The Holy Alliance was the brainchild of Tsar Alexander I. It gained support because most European monarchs did not wish to offend the Tsar by refusing to sign it, and as it bound monarchs personally rather than their governments, it was easy to ignore once signed. Although it did not fit comfortably within the complex, sophisticated, and cynical web of power politics that epitomized diplomacy of the post Napoleonic era, its influence was more lasting than contemporary critics expected and was revived in the 1820s as a tool of repression when the terms of the Quintuple Alliance were not seen to fit the purposes of some of the Great Powers of Europe.

The Quadruple Alliance, by contrast, was a standard treaty and the four Great Powers did not invite any of their allies to sign it. The primary objective was to bind the signatures to support the terms of the Second Treaty of Paris for 20 years. It included a provision for the High Contracting Parties to “renew their meeting at fixed periods…for the purpose of consulting on their common interests” which were the “prosperity of the Nations, and the maintenance of peace in Europe.” A problem with the wording of Article VI of the treaty is that it did not specify what these “fixed periods” would be, and there were no provisions in the treaty for a permanent commission to arrange and organize the conferences. This meant that the first conference in 1818 dealt with remaining issues of the French wars, but after that, meetings were arranged on an ad hoc basis to address specific threats such as those posed by revolutions.

24.2: France after 1815

24.2.1: Louis XVIII and the Bourbon Restoration

The Bourbon Restoration, which restored the pre-Napoleonic monarchy to the throne, was marked by conflicts between reactionary Ultra-royalists, who wanted to restore the pre-1789 system of absolute monarchy, and liberals, who wanted to strengthen constitutional monarchy.

Learning Objective

Define the Bourbon Restoration and its goals

Key Points

- The Bourbon Restoration was the period of French history following the fall of Napoleon in 1814 until the July Revolution of 1830.

- After Napoleon abdicated as emperor in March 1814, Louis XVIII, the brother of Louis XVI, was installed as king and France was granted a quite generous peace settlement, restored to its 1792 boundaries and not required to pay war indemnity.

- On becoming king, Louis issued a constitution known as the Charter which preserved many of the liberties won during the French Revolution and provided for a parliament composed of an elected Chamber of Deputies and a Chamber of Peers that was nominated by the king.

- A constitution, the Charter of 1814, was drafted; it presented all Frenchmen as equal before the law, but retained substantial prerogative for the king and nobility and limited voting to those paying at least 300 francs a year in direct taxes.

- After the Hundred Days, when Napoleon briefly returned to power, Louis XVIII was restored a second time by the allies in 1815, ending more than two decades of war.

- At this time, a more harsh peace treaty was imposed on France, returning it to its 1789 boundaries and requiring a war indemnity.

- There were large-scale purges of Bonapartists from the government and military, and a brief “White Terror” in the south of France claimed 300 victims.

- Despite the return of the House of Bourbon to power, France was much changed; the egalitarianism and liberalism of the revolutionaries remained an important force and the autocracy and hierarchy of the earlier era could not be fully restored.

Key Terms

- Napoleonic Code

-

The French civil code established under Napoléon I in 1804. It marked the end of feudalism and the liberation of serfs where it took effect. It recognized the principles of civil liberty, equality before the law, and the secular character of the state. It discarded the old right of primogeniture (where only the eldest son inherited) and required that inheritances be divided equally among all children. The court system was standardized; all judges were appointed by the national government in Paris.

- White Terror

-

Following the return of Louis XVIII to power in 1815, people suspected of having ties with the governments of the French Revolution or of Napoleon suffered arrest and execution.

- House of Bourbon

-

A European royal house of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, who first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century and by the 18th century, also held thrones in Spain, Naples, Sicily, and Parma.

- biens nationaux

-

Properties confiscated during the French Revolution from the Catholic Church, the monarchy, émigrés, and suspected counter-revolutionaries for “the good of the nation.”

The Bourbon Restoration was the period of French history following the fall of Napoleon in 1814 until the July Revolution of 1830. The brothers of executed Louis XVI of France reigned in highly conservative fashion, and the exiles returned. They were nonetheless unable to reverse most of the changes made by the French Revolution and Napoleon. At the Congress of Vienna they were treated respectfully, but had to give up all the territorial gains made since 1789.

King Louis XVI of the House of Bourbon had been overthrown and executed during the French Revolution (1789–1799), which in turn was followed by Napoleon as ruler of France. A coalition of European powers defeated Napoleon in the War of the Sixth Coalition, ended the First Empire in 1814, and restored the monarchy to the brothers of Louis XVI. The Bourbon Restoration lasted from (about) April 6, 1814, until the popular uprisings of the July Revolution of 1830. There was an interlude in spring 1815—the “Hundred Days”—when the return of Napoleon forced the Bourbons to flee France. When Napoleon was again defeated they returned to power in July.

During the Restoration, the new Bourbon regime was a constitutional monarchy, unlike the absolutist Ancien Régime, so it had limits on its power. The period was characterized by a sharp conservative reaction and consequent minor but consistent civil unrest and disturbances. It also saw the reestablishment of the Catholic Church as a major power in French politics.

First Restoration

Louis XVIII’s restoration to the throne in 1814 was effected largely through the support of Napoleon’s former foreign minister, Talleyrand, who convinced the victorious Allied Powers of the desirability of a Bourbon Restoration. The Allies had initially split on the best candidate for the throne: Britain favored the Bourbons, the Austrians considered a regency for Napoleon’s son, François Bonaparte, and the Russians were open to either the duc d’Orléans, Louis Philippe, or Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, Napoleon’s former Marshal, who was in line for the Swedish throne. Napoleon was offered to keep the throne in February 1814 on the condition that France return to its 1792 frontiers, but he refused.

The Great Powers occupying Paris demanded that Louis XVIII implement a constitution. Louis responded with the Charter of 1814, which included many progressive provisions: freedom of religion, a legislature composed of the Chamber of Deputies, and the Chamber of Peers, a press that would enjoy a degree of freedom, and a provision that the Biens nationaux would remain in the hands of their current owners. The two Chambers’ role was consultative (except on taxation), as only the King had the power to propose or sanction laws and appoint or recall ministers. Voting was limited to men with considerable property holdings, and just 1% of people could vote.

Louis XVIII signed the Treaty of Paris on May 30, 1814. The treaty gave France its 1792 borders, which extended east of the Rhine. The country had to pay no war indemnity, and the occupying armies of the Sixth Coalition withdrew instantly from French soil.

Despite the return of the House of Bourbon to power, France was much changed from the era of the Ancien Régime. The egalitarianism and liberalism of the revolutionaries remained an important force and the autocracy and hierarchy of the earlier era could not be fully restored. The economic changes, which were underway long before the revolution, had been further enhanced during the years of turmoil and were firmly entrenched by 1815. These changes saw power shift from the noble landowners to the urban merchants.

Many of the legal, administrative, and economic reforms of the revolutionary period were left intact; the Napoleonic Code, which guaranteed legal equality and civil liberties, the peasants’ biens nationaux, and the new system of dividing the country into départments were not undone by the new king. Relations between church and state remained regulated by the Concordat of 1801. However, in spite of the fact that the Charter was a condition of the Restoration, the preamble declared it to be a “concession and grant,” given “by the free exercise of our royal authority.”

After a first sentimental flush of popularity, Louis’ gestures towards reversing the results of the French Revolution quickly lost him support among the disenfranchised majority. Symbolic acts such as the replacement of the tricolore flag with the white flag, the titling of Louis as the “XVIII” (as successor to Louis XVII, who never ruled) and as “King of France” rather than “King of the French”, and the monarchy’s recognition of the anniversaries of the deaths of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were significant. A more tangible source of antagonism was the pressure applied to possessors of biens nationaux by the Catholic Church and returning émigrés attempting to repossess their former lands.

Hundred Days

On February 26, 1815, Napoleon Bonaparte escaped his island prison of Elba and embarked for France. He arrived with about 1,000 troops near Cannes on March 1. Louis XVIII was not particularly worried by Bonaparte’s excursion, as such a small number of troops could be easily overcome. There was, however, a major underlying problem for the Bourbons: Louis XVIII failed to purge the military of its Bonapartist troops. This led to mass desertions from the Bourbon armies to Bonaparte’s. Furthermore, Louis XVIII could not join the campaign against Napoleon in the south of France because he was suffering from gout.

Louis XVIII’s underestimation of Bonaparte proved disastrous. On March 19, the army stationed outside Paris defected to Bonaparte, leaving the city vulnerable to attack. That same day, Louis XVIII quit the capital with a small escort at midnight. Louis decided to go first to Lille, then crossed the border into the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, staying in Ghent.

However, Napoleon did not rule France again for very long, suffering a decisive defeat at the hands of the armies of the Duke of Wellington and Field Marshal Blücher at the Battle of Waterloo on June 18. The Allies came to the consensus that Louis XVIII should be restored to the throne of France.

Second Restoration

Talleyrand was again influential in seeing that the Bourbons reigned, as was Fouché, Napoleon’s minister of police during the Hundred Days. After the Hundred Days, a harsher peace treaty was imposed on France, returning it to its 1789 boundaries and requiring a war indemnity. Allied troops were to remain in the country until it was paid.

Louis XVIII’s role in politics from the Hundred Days onward was voluntarily diminished; he resigned most of his duties to his council. He and his ministry embarked on a series of reforms through the summer of 1815. The king’s council, an informal group of ministers that advised Louis XVIII, was dissolved and replaced by a tighter knit privy council, the “Ministère de Roi.” Talleyrand was appointed as the first Président du Conseil, i.e. Prime Minister of France. On July 14, the ministry dissolved the units of the army deemed “rebellious.” Hereditary peerage was reestablished to Louis’s behest by the ministry.

In August, elections for the Chamber of Deputies returned unfavorable results for Talleyrand. The ministry wished for moderate deputies, but the electorate voted almost exclusively for ultra-royalists. Talleyrand tendered his resignation on September 20. Louis XVIII chose the Duke of Richelieu to be his new Prime Minister. Richelieu was chosen because he was accepted by Louis’s family and the reactionary Chamber of Deputies.

Anti-Napoleonic sentiment was high in Southern France, and this was prominently displayed in the White Terror, the purge of all important Napoleonic officials from government and the execution of others. The people of France committed barbarous acts against some of these officials. Guillaume Marie Anne Brune (a Napoleonic marshal) was savagely assassinated and his remains thrown into the Rhône River. Louis XVIII deplored such illegal acts, but vehemently supported the prosecution of marshals that helped Napoleon in the Hundred Days. The White Terror claimed 300 victims.

The king was reluctant to shed blood, which greatly irritated the ultra-reactionary Chamber of Deputies, who felt that Louis XVIII was not executing enough people. The government issued a proclamation of amnesty to the “traitors” in January 1816, but the trials in progress were finished in due course. That same declaration banned any member of the House of Bonaparte from owning property in or entering France.

In 1823, France intervened in Spain where a civil war had deposed King Ferdinand VII. The British objected as this brought back memories of the still recent Peninsular War. However, the French troops marched into Spain, retook Madrid from the rebels, and left almost as quickly as they came. Despite worries to the contrary, France showed no sign of returning to an aggressive foreign policy and was admitted to the Concert of Europe in 1818.

Louis XVIII died on September 16, 1824, and was succeeded by his brother, the comte d’Artois, who took the title of Charles X.

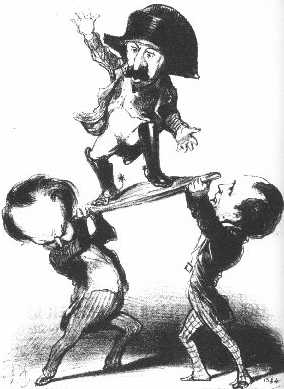

Allegory of the Return of the Bourbons on 24 April 1814 : Louis XVIII Lifting France from Its Ruins

A painting by Louis-Philippe symbolizing the Bourbon Restoration as “lifting France from its ruins.” It shows the newly appointed king, Louis XVIII, lifting up a falling women, who symbolized France after the Napoleonic Wars.

24.2.2: Charles X and the July Revolution

In 1830 the discontent caused by Charles X’s conservative policies and his nomination of the Ultra prince de Polignac as minister culminated in an uprising in the streets of Paris, known as the July Revolution, which brought about an end to the Bourbon Restoration.

Learning Objective

Evaluate why the July Revolution occurred

Key Points

- Charles X of France took a far more conservative line than his brother Louis XVIII.

- He attempted to rule as an absolute monarch in the style of Ancien Régime and reassert the power of the Catholic Church in France.

- His coronation in 1824 also coincided with the height of the power of the Ultra-royalist party, who also wanted a return of the aristocracy and absolutist politics.

- A few years into his rule, unrest among the people of France began to develop, caused by an economic downturn, resistance to the return to conservative politics, and the rise of a liberal press.

- In 1830 the discontent caused by these changes and Charles X’s authoritarian nomination of the Ultra prince de Polignac as minister culminated in an uprising in the streets of Paris known as the 1830 July Revolution.

- Charles was forced to flee and Louis-Philippe d’Orléans, a member of the Orléans branch of the family and son of Philippe Égalité who had voted the death of his cousin Louis XVI, ascended the throne, beginning the more liberal July Monarchy.

Key Terms

- ultra-royalist

-

A political part in 19th century France who wished for a return to the Ancien Régime of before 1789, with a view toward absolutism: domination by the nobility and “other devoted Christians.” They were anti-republican, anti-democratic, and preached Government on High by a marked noble elite. They tolerated vote censitaire, a form of democracy limited to those paying taxes above a high threshold.

- Ancien Régime

-

The monarchic, aristocratic, social, and political system established in the Kingdom of France from approximately the 15th century until the latter part of the 18th century (“early modern France”) under the late Valois and Bourbon dynasties.

- July Revolution

-

This uprising of 1830 saw the overthrow of King Charles X, the French Bourbon monarch, and the ascent of his cousin Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans, who after 18 precarious years on the throne would be overthrown in 1848. It marked the shift from one constitutional monarchy, the Bourbon Restoration, to another, the July Monarchy.

Compared to his brother Louis XVIII, who ruled from 1814-1824, Charles X of France took a far more conservative line. He attempted to rule as an absolute monarch and reassert the power of the Catholic Church in France. Acts of sacrilege in churches became punishable by death, and freedom of the press was severely restricted. Finally, he tried to compensate the families of the nobles who had had their property destroyed during the Revolution.

In 1830 the discontent caused by these changes and Charles X’s authoritarian nomination of the Ultra prince de Polignac as minister culminated in an uprising in the streets of Paris, known as the 1830 July Revolution (or, in French, “Les trois Glorieuses,” the three glorious days of July 27-29). Charles was forced to flee and Louis-Philippe d’Orléans, a member of the Orléans branch of the family and son of Philippe Égalité who had voted the death of his cousin Louis XVI, ascended the throne. Louis-Philippe ruled not as “King of France” but as “King of the French” (an evocative difference for contemporaries). It was made clear that his right to rule came from the people and was not divinely granted. He also revived the tricolore as the flag of France in place of the white Bourbon flag that had been used since 1815, an important distinction because the tricolore was the symbol of the revolution.

Charles X (1824–1830)

The ascension to the throne of Charles X, the leader of the Ultra-royalist faction, coincided with the Ultras’ control of power in the Chamber of Deputies; thus, the ministry of the comte de Villèle was able to continue, and the last “restraint” (i.e., Louis) on the Ultra-royalists was removed. As the country underwent a Christian revival in the post-Revolutionary years, the Ultras saw fit to raise the status of the Roman Catholic Church once more.

On May 29, 1825, Charles was crowned in Reims in an opulent and spectacular ceremony that was reminiscent of the royal pomp of the coronations of the Ancien Régime. Some innovations were included upon request by Villèle; although Charles was hostile towards the 1814 Charter, commitment to the “constitutional charter” was affirmed with four of Napoleon’s generals in attendance.

While his brother had been sober enough to realize that France would never accept an attempt to resurrect the Ancien Régime, Charles had never been willing to accept the changes of the past four decades. He gave his Prime Minister, Jean-Baptiste de Villèle, lists of laws that he wanted ratified every time he opened parliament. In April 1825, the government approved legislation proposed by Louis XVIII but implemented only after his death, that paid an indemnity to nobles whose estates had been confiscated during the Revolution (the biens nationaux).

The law gave government bonds to those who had lost their lands in exchange for their renunciation of their ownership. This cost the state approximately 988 million francs. In the same month, the Anti-Sacrilege Act was passed. Charles’s government attempted to re-establish male-only primogeniture for families paying over 300 francs in tax, but the measure was voted down in the Chamber of Deputies.

On May 29, 1825, King Charles was anointed at the cathedral of Reims, the traditional site of consecration of French kings; it had been unused since 1775, as Louis XVIII had forgone the ceremony to avoid controversy. It was in the venerable cathedral of Notre-Dame at Paris that Napoleon consecrated his revolutionary empire, but in ascending the throne of his ancestors, Charles reverted to the old place of coronation used by the kings of France from the early ages of the monarchy.

That Charles was not a popular ruler became apparent in April 1827, when chaos ensued during the king’s review of the National Guard in Paris. In retaliation, the National Guard was disbanded but as its members were not disarmed, it remained a potential threat.

Downfall of the Bourbons

There is still considerable debate among historians as to the actual cause of the downfall of Charles X. What is generally conceded, though, is that between 1820 and 1830, a series of economic downturns combined with the rise of a liberal opposition within the Chamber of Deputies ultimately felled the conservative Bourbons.

Between 1827 and 1830, France faced an economic downturn, industrial and agricultural, that was possibly worse than the one that sparked the Revolution of 1789. A series of progressively worsening grain harvests in the late 1820s pushed up the prices on various staple foods and cash crops. In response, the rural peasantry throughout France lobbied for the relaxation of protective tariffs on grain to lower prices and ease their economic situation. However, Charles X, bowing to pressure from wealthier landowners, kept the tariffs in place.

While the French economy faltered, a series of elections brought a relatively powerful liberal bloc into the Chamber of Deputies. The 17-strong liberal bloc of 1824 grew to 180 in 1827 and 274 in 1830. This liberal majority grew increasingly dissatisfied with the policies of the centrist Martignac and the Ultra-royalist Polignac, seeking to protect the limited protections of the Charter of 1814.

Also, the growth of the liberal bloc within the Chamber of Deputies corresponded roughly with the rise of a liberal press within France. Generally centered around Paris, this press provided a counterpoint to the government’s journalistic services and to the newspapers of the right. It grew increasingly important in conveying political opinions and the political situation to the Parisian public and can thus be seen as a crucial link between the rise of the liberals and the increasingly agitated and economically suffering French masses.

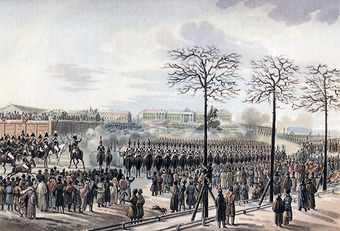

July Revolution

Protest against the absolute monarchy was in the air. The elections of deputies on May 16, 1830, had gone very badly for King Charles X. In response, he tried repression but that only aggravated the crisis as suppressed deputies, gagged journalists, students from the University, and many working men of Paris poured into the streets and erected barricades during the “three glorious days” (French Les Trois Glorieuses) of July 26-29 1830. Charles X was deposed and replaced by King Louis-Philippe in the July Revolution. It is traditionally regarded as a rising of the bourgeoisie against the absolute monarchy of the Bourbons. Participants in the July Revolution included Marie Joseph Paul Ives Roch Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette. Working behind the scenes on behalf of the bourgeois-propertied interests was Louis Adolphe Thiers.

The July Revolution marked the shift from one constitutional monarchy, the Bourbon Restoration, to another, the July Monarchy; the transition of power from the House of Bourbon to its cadet branch, the House of Orléans; and the replacement of the principle of hereditary right by popular sovereignty. Supporters of the Bourbon were called Legitimists, and supporters of Louis Philippe Orléanists.

The Revolution broke out on July 27, 1830. Throughout the day, Paris grew quiet as the milling crowds grew larger. At 4:30 pm, commanders of the troops of the First Military division of Paris and the Garde Royale were ordered to concentrate their troops, and guns, on the Place du Carrousel facing the Tuileries, the Place Vendôme, and the Place de la Bastille. To maintain order and protect gun shops from looters, military patrols throughout the city were established, strengthened, and expanded. However, no special measures were taken to protect either the arm depots or gunpowder factories. For a time, those precautions seemed premature, but with the coming of twilight, the fighting began. According to historian Phil Mansel, “Parisians, rather than soldiers, were the aggressor. Paving stones, roof tiles, and flowerpots from the upper windows… began to rain down on the soldiers in the streets.” At first, soldiers fired warning shots into the air. But before the night was over, 21 civilians were killed. Fighting in Paris continued throughout the night.

On day two, Charles X ordered Maréchal Auguste Marmont, Duke of Ragusa, the on-duty Major-General of the Garde Royale, to repress the disturbances. Marmont’s plan was to have the Garde Royale and available line units of the city garrison guard the vital thoroughfares and bridges of the city and protect important buildings such as the Palais Royal, Palais de Justice, and the Hôtel de Ville. This plan was both ill-considered and wildly ambitious; not only were there not enough troops, but there were also nowhere near enough provisions. At 4 p.m., Charles X received Colonel Komierowski, one of Marmont’s chief aides. The colonel was carrying a note from Marmont to his Majesty:

Sire, it is no longer a riot, it is a revolution. It is urgent for Your Majesty to take measures for pacification. The honour of the crown can still be saved. Tomorrow, perhaps, there will be no more time… I await with impatience Your Majesty’s orders.

On day three, the revolutionaries were well-organized and very well-armed. In only a day and a night, over 4,000 barricades had been thrown up throughout the city. The tricolore flag of the revolutionaries – the “people’s flag” – flew over buildings, an increasing number of them important buildings. By 1:30 pm, the Tuileries Palace had been sacked. By mid-afternoon the greatest prize, the Hôtel de Ville, had been captured. A few hours later, politicians entered the battered complex and set about establishing a provisional government. Though there would be spots of fighting throughout the city for the next few days, the revolution, for all intents and purposes, was over.

The revolution of July 1830 created a constitutional monarchy. On August 2, Charles X and his son the Dauphin abdicated their rights to the throne and departed for Great Britain. Although Charles had intended that his grandson, the Duke of Bordeaux, would take the throne as Henry V, the politicians who composed the provisional government instead placed on the throne a distant cousin, Louis Philippe of the House of Orléans, who agreed to rule as a constitutional monarch. This period became known as the July Monarchy.

Liberty Leading the People

A painting by Eugène Delacroix commemorating the July Revolution of 1830, which toppled King Charles X of France. A woman personifying the concept and the Goddess of Liberty leads the people forward over the bodies of the fallen, holding the flag of the French Revolution – the tricolore flag, which remains France’s national flag – in one hand and brandishing a bayonetted musket with the other. The figure of Liberty is also viewed as a symbol of France and the French Republic known as Marianne.

24.2.3: The July Monarchy

The July Monarchy (1830–1848) is generally seen as a period during which the upper-middle class (haute bourgeoisie) was dominant. It marked the shift from the counter-revolutionary Legitimists to the Orleanists, who were willing to make some compromises with the changes of the 1789 Revolution, but maintained a conservative regime marked by constant civil unrest.

Learning Objective

Contrast the July monarchy with the reign of Charles X

Key Points

- In 1830, the discontent caused by Charles X’s authoritarian policies culminated in an uprising in the streets of Paris known as the 1830 July Revolution.

- Charles was forced to flee and Louis-Philippe d’Orléans, a member of the Orléans branch of the family and son of Philippe Égalité who had voted the death of his cousin Louis XVI, ascended the throne, marking the beginning of the July Monarchy, so named for the Revolution.

- Louis-Philippe ruled not as “King of France” but as “King of the French,” which made clear that his right to rule came from the people and was not divinely granted.

- Despite this and other such gestures (for example, reviving the tricolore as the flag of France in place of the white Bourbon flag that had been used since 1815), Louis-Philippe remained conservative, and reforms mainly benefited the upper-class citizens.

- Because of the conservative character of Louis-Philippe’s regime, civil unrest remained a permanent feature of the July Monarchy, with riots and uprising continuing throughout his rule.

- In February 1848, the French government banned the holding of the Campagne des banquets, fundraising dinners by activists where critics of the regime would meet (as public demonstrations and strikes were forbidden).

- As a result, protests and riots broke out in the streets of Paris. An angry mob converged on the royal palace, after which the hapless king abdicated and fled to England; the Second Republic was then proclaimed, ending the July Monarchy.

Key Terms

- campagne des banquets

-

Political meetings during the July Monarchy in France that destabilized the King of the French Louis-Philippe. The campaign officially took place from July 9, 1847, to December, 25 1847, but in fact continued until the February 1848 Revolution during which the Second Republic was proclaimed.

- Louis Philippe I

-

King of the French from 1830 to 1848 as the leader of the Orléanist party. His government, known as the July Monarchy, was dominated by members of a wealthy French elite and numerous former Napoleonic officials. He followed conservative policies, especially under the influence of the French statesman François Guizot from 1840–48.

- haute bourgeoisie

-

A social rank in the bourgeoisie that can only be acquired through time. In France, it is composed of bourgeois families that have existed since the French Revolution. They hold only honorable professions and have experienced many illustrious marriages in their family’s history. They have rich cultural and historical heritages, and their financial means are more than secure. These families exude an aura of nobility that prevents them from certain marriages or occupations. They only differ from nobility in that due to circumstances, lack of opportunity, and/or political regime, they have not been ennobled.

The French Kingdom, commonly known as the July Monarchy, was a liberal constitutional monarchy in France under Louis Philippe I, starting with the July Revolution of 1830 (also known as the Three Glorious Days) and ending with the Revolution of 1848. It began with the overthrow of the conservative government of Charles X and the House of Bourbon. Louis Philippe, a member of the traditionally more liberal Orléans branch of the House of Bourbon, proclaimed himself Roi des Français (“King of the French”) rather than “King of France,” emphasizing the popular origins of his reign. The king promised to follow the “juste milieu”, or the middle-of-the-road, avoiding the extremes of the conservative supporters of Charles X and radicals on the left. The July Monarchy was dominated by wealthy bourgeoisie and numerous former Napoleonic officials. It followed conservative policies, especially under the influence (1840–48) of François Guizot. The king promoted friendship with Great Britain and sponsored colonial expansion, notably the conquest of Algeria. By 1848, a year in which many European states had a revolution, the king’s popularity had collapsed, and he was overthrown.

Louis Philippe I

The July Monarchy (1830–1848) is generally seen as a period during which the haute bourgeoisie was dominant. It marked the shift from the counter-revolutionary Legitimists to the Orleanists, who were willing to make compromises with the changes brought by the 1789 Revolution. Louis-Philippe’s taking of the title “King of the French” marked his acceptance of popular sovereignty, which replaced the Ancien Régime’s divine right. Louis-Philippe clearly understood his base of power: the wealthy bourgeoisie carried him aloft during the July Revolution through their work in the Parliament, and throughout his reign, he kept their interests in mind.

During the first several years of his regime, Louis-Philippe appeared to move his government toward legitimate, broad-based reform. The government found its source of legitimacy within the Charter of 1830, written by reform-minded members of Chamber of Deputies upon a platform of religious equality, the empowerment of the citizenry through the reestablishment of the National Guard, electoral reform, the reformation of the peerage system, and the lessening of royal authority. Indeed, Louis-Phillippe and his ministers adhered to policies that seemed to promote the central tenets of the constitution. However, the majority of these were veiled attempts to shore up the power and influence of the government and the bourgeoisie, rather than legitimate attempts to promote equality and empowerment for a broad constituency of the French population. Thus, though the July Monarchy seemed to move toward reform, this movement was largely illusory.

During the years of the July Monarchy, enfranchisement roughly doubled, from 94,000 under Charles X to more than 200,000 by 1848. However, this represented less than one percent of population, and as the requirements for voting were tax-based, only the wealthiest gained the privilege. By implication, the enlarged enfranchisement tended to favor the wealthy merchant bourgeoisie more than any other group.

The reformed Charter of 1830 limited the power of the King – stripping him of his ability to propose and decree legislation, as well as limiting his executive authority. However, the King of the French still believed in a version of monarchy that held the king as much more than a figurehead for an elected Parliament, and as such, he was quite active in politics. One of the first acts of Louis-Philippe in constructing his cabinet was to appoint the rather conservative Casimir Perier as the premier. Perier, a banker, was instrumental in shutting down many of the Republican secret societies and labor unions that had formed during the early years of the regime. In addition, he oversaw the dismemberment of the National Guard after it proved too supportive of radical ideologies.

The regime acknowledged early on that radicalism and republicanism threatened it by undermining its laissez-faire policies. Thus, the Monarchy declared the very term republican illegal in 1834. Guizot shut down republican clubs and disbanded republican publications. Republicans within the cabinet, like the banker Dupont, were all but excluded by Perier and his conservative clique. Distrusting the sole National Guard, Louis-Philippe increased the size of the army and reformed it in order to ensure its loyalty to the government.

Louis-Philippe, 1842

King Louis-Philippe I, the liberal and constitutional King of the French, brought to power by the July Revolution.

Unrest in the July Monarchy: Revolution of 1848

Louis-Philippe, who had flirted with liberalism in his youth, rejected much of the pomp and circumstance of the Bourbons and surrounded himself with merchants and bankers. The July Monarchy, however, remained a time of turmoil. A large group of Legitimists on the right demanded the restoration of the Bourbons to the throne. On the left, Republicanism and later Socialism, remained a powerful force.

Civil unrest continued after the July Revolution, supported by the left-wing press. Louis-Philippe’s government was not able to end it, mostly because the National Guard was headed by one of the Republican leaders, the marquis de La Fayette, who requested a “popular throne surrounded by Republican institutions.” The Republicans then gathered themselves in popular clubs in the tradition established by the 1789 Revolution. Some of those were fronts for secret societies, which requested political and social reforms or the execution of Charles X’s ministers. Strikes and demonstrations were permanent.

Despite the reforms made by Louis-Philippe’s regime, which targeted the bourgeoisie rather than the people, Paris was once again rocked by riots on February 14-15, 1831. Riots and protests continued throughout his reign, including the Canuts Revolt, started on November 21, 1831, during which parts of the National Guard took the demonstrators’ side.

Late in his reign, Louis-Philippe became increasingly rigid and dogmatic. For example, his President of the Council, François Guizot, had become deeply unpopular, but Louis-Philippe refused to remove him.

Around this same time, there was another economic downturn, which especially affected the lower classes. There was an increase in workers’ demonstrations, with riots in the Buzançais in 1847. In Roubaix, a city in the industrial north, 60% of the workers were unemployed. At the same time, the regime was marred by several political scandals (Teste–Cubières corruption scandal, revealed in May 1847, and Charles de Choiseul-Praslin’s suicide after murdering his wife, daughter of Horace Sébastiani).

Since the right of association was strictly restricted and public meetings prohibited after 1835, the opposition was paralyzed. To sidestep this law, political dissidents used civil funerals of their comrades as occasions for public demonstrations. Family celebrations and banquets also served as pretexts for gatherings. This campaign of banquets (Campagne des banquets), was intended to circumvent the governmental restriction on political meetings and provide a legal outlet for popular criticism of the regime. The campaign began in July 1847. Friedrich Engels was in Paris from October 1847 and was able to observe and attend some of these banquets.

The banquet campaign lasted until all political banquets were outlawed by the French government in February 1848. As a result, the people revolted, helping to unite the efforts of the popular Republicans and the liberal Orleanists, who turned their backs on Louis-Philippe.

Anger over the outlawing of the political banquets brought crowds of Parisians flooding into the streets at noon on February 22, 1848. The crowds directed their anger against the Citizen King Louis Philippe and his chief minister for foreign and domestic policy, François Pierre Guillaume Guizot. At 2 p.m. the next day, Prime Minister Guizot resigned. Upon hearing the news of Guizot’s resignation, a large crowd gathered outside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. An officer ordered the crowd not to pass, but people in the front of the crowd were being pushed by the rear. The officer ordered his men to fix bayonets, probably wishing to avoid shooting. However, in what is widely regarded as an accident, a soldier discharged his musket, which resulted in the rest of the soldiers firing into the crowd. Fifty-two people were killed.

Paris was soon a barricaded city. Omnibuses were turned into barricades, and thousands of trees were felled. Fires were set, and angry citizens began converging to the royal palace. King Louis Philippe abdicated and fled to the UK.

24.2.4: The Second French Republic

On February 26, 1848, the liberal opposition from the 1848 Revolution came together to organize a provisional government, called the Second Republic, which was marked by disorganization and political ambiguity.

Learning Objective

Break down some of the challenges faced by the Second French Republic

Key Points

- The 1848 Revolution in France ended the Orleans monarchy (1830–48) and led to the creation of the French Second Republic.

- Following the overthrow of King Louis Philippe in February, a provisional government (Constituent Assembly) was created, which was disorganized as it attempted to deal with France’s economic problems created by the political upheaval.

- Frustration among the laboring classes arose when the Constituent Assembly did not address the concerns of the workers, leading to strikes and worker demonstrations.

- Louis Napoleon Bonaparte was elected president on December 10, 1848, by a landslide; his support came from a wide section of the French public.

- Because of the ambiguity surrounding Louis Napoleon’s political positions, his agenda as president was very much in doubt.

- The 1850 elections resulted in a conservative body, which renewed the power of the Church, especially in education.

- As 1851 opened, Louis-Napoleon was not allowed by the Constitution of 1848 to seek re-election as President of France; instead he proclaimed himself President for Life following a coup in December that was confirmed and accepted in a dubious referendum.

Key Terms

- National Workshops

-

Areas of work provided for the unemployed by the French Second Republic after the Revolution of 1848. The political issues that resulted in the abdication of Louis Philippe caused an acute industrial crisis adding to the general agricultural and commercial distress which had prevailed throughout 1847. It greatly exacerbated the problem of unemployment in Paris. The provisional government under the influence of one of its members, Louis Blanc, passed a decree (February 25, 1848) guaranteeing government-funded jobs.

- French Second Republic

-

The republican government of France between the 1848 Revolution and the 1851 coup by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte that initiated the Second Empire.

- French Revolution of 1848

-

Sometimes known as the February Revolution, one of a wave of revolutions in 1848 in Europe. In France the revolutionary events ended the Orleans monarchy (1830–48) and led to the creation of the French Second Republic.

The French Revolution of 1848 had major consequences for all of Europe; popular democratic revolts against authoritarian regimes broke out in Austria and Hungary, in the German Confederation and Prussia, and in the Italian States of Milan, Venice, Turin and Rome. Economic downturns and bad harvests during the 1840s contributed to growing discontent.

In February 1848, the French government banned the holding of the Campagne des banquets, fundraising dinners by activists where critics of the regime would meet (as public demonstrations and strikes were forbidden). As a result, protests and riots broke out in the streets of Paris. An angry mob converged on the royal palace, after which the hapless king abdicated and fled to England. The Second Republic was then proclaimed.