21.1: The Age of Enlightenment

21.1.1: Enlightenment Ideals

Centered on the idea that reason is the primary source of authority and legitimacy, the Enlightenment was a philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe in the 18th century.

Learning Objective

Identify the core ideas that drove the Age of Enlightenment

Key Points

-

The

Age of Enlightenment was a philosophical

movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe in the 18th century.

Centered on the idea that reason is the primary source of authority and

legitimacy, this movement advocated such ideals as liberty, progress, tolerance,

fraternity, constitutional government, and separation of church and state. -

There

is little consensus on the precise beginning of the Age of Enlightenment, but the beginning of the 18th century (1701) or the

middle of the 17th century (1650) are commonly identified as starting points. French historians usually place the period

between 1715 and 1789. Most scholars use the last years of the century, often choosing the

French Revolution of 1789 or the beginning of the Napoleonic

Wars (1804–15) to date the end of

the Enlightenment. -

The

Enlightenment took hold in most European countries, often with a specific local

emphasis.

The

cultural exchange during the Age of Enlightenment ran between particular European countries and also in both directions across

the Atlantic. -

There were two distinct

lines of Enlightenment thought. The radical Enlightenment advocated democracy, individual liberty, freedom of

expression, and eradication of religious authority. A second, more moderate

variety sought accommodation between reform and the traditional systems of

power and faith. -

Science

came to play a leading role in Enlightenment discourse and thought. The Enlightenment has long been hailed as the foundation of modern Western

political and intellectual culture. It brought political modernization to the

West. In

religion, Enlightenment era commentary was a response to the preceding century

of religious conflict in Europe. -

Historians

of race, gender, and class note that Enlightenment ideals were not originally

envisioned as universal in the today’s sense of the word. Although they did

eventually inspire the struggles for rights of people of color, women, or the

working masses, most Enlightenment thinkers did not advocate equality for all,

regardless of race, gender, or class, but rather insisted that rights and

freedoms were not hereditary.

Key Terms

- reductionism

-

Several related but distinct philosophical positions regarding the connections between theories, “reducing” one idea to another, more basic one. In the sciences, its methodologies attempt to explain entire systems in terms of their individual, constituent parts and interactions.

- scientific method

-

A body of techniques for investigating phenomena,

acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge that

apply empirical or measurable evidence subject to specific principles

of reasoning. It has characterized natural science since the 17th

century, consisting of systematic observation, measurement, and experimentation, and

the formulation, testing, and modification of hypotheses. - cogito ergo sum

-

A Latin philosophical proposition by René Descartes usually translated into English as “I think, therefore I am.” The phrase originally appeared in his Discourse on the Method. This proposition became a fundamental element of Western philosophy, as it purported to form a secure foundation for knowledge in the face of radical doubt.

While other knowledge could be a figment of imagination, deception, or mistake, Descartes asserted that the very act of doubting one’s own existence served—at minimum—as proof of the reality of one’s own mind. - empiricism

-

The theory that knowledge comes primarily from

sensory experience. It emphasizes evidence, especially data gathered through experimentation and use of the scientific method.

The Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment, also known as the Enlightenment, was a philosophical

movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe in the 18th century. Centered on the idea that reason is the primary source of authority

and legitimacy, this movement advocated such ideals as liberty, progress, tolerance,

fraternity, constitutional government, and separation of church and state. The

Enlightenment was marked by an emphasis on the scientific method and

reductionism along with increased questioning of religious orthodoxy. The core ideas advocated by modern democracies, including the civil society, human and civil rights, and separation of powers, are the product of the Enlightenment. Furthermore, the sciences and academic disciplines (including social sciences and the humanities) as we know them today, based on empirical methods, are also rooted in the Age of Enlightenment. All these developments, which followed and partly overlapped with the European exploration and colonization of the Americas and the intensification of the European presence in Asia and Africa, make the Enlightenment a starting point of what some historians define as the European Moment in World History: the long period of often tragic European domination over the rest of the world.

There is little consensus on the precise beginning of the Age of Enlightenment, with the beginning of the 18th century (1701) or the middle of the 17th century (1650) often considered starting points. French historians usually place the period between 1715 and 1789, from the beginning of the reign of Louis XV until the French Revolution. In the mid-17th century, the Enlightenment traces its origins to Descartes’ Discourse on Method, published in 1637. In France, many cite the publication of Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica in 1687. Some historians and philosophers have argued that the beginning of the Enlightenment is when Descartes shifted the epistemological basis from external authority to internal certainty by his cogito ergo sum (1637).

As to its end, most scholars use the last years of the century, often choosing the French Revolution of 1789 or the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars (1804–15) to date the end of the Enlightenment.

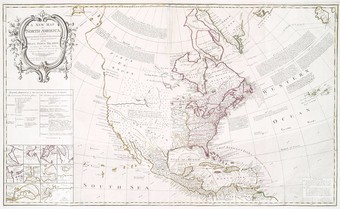

National Varieties

The Enlightenment took hold in most European countries, often with a specific local emphasis. For example, in France it became associated with anti-government and anti-Church radicalism, while in Germany it reached deep into the middle classes and took a spiritualistic and nationalistic tone without threatening governments or established churches. Government responses varied widely. In France, the government was hostile and Enlightenment thinkers fought against its censorship, sometimes being imprisoned or hounded into exile. The British government largely ignored the Enlightenment’s leaders in England and Scotland. The Scottish Enlightenment, with its mostly liberal Calvinist and Newtonian focus, played a major role in the further development of the transatlantic Enlightenment. In Italy, the significant reduction in the Church’s power led to a period of great thought and invention, including scientific discoveries. In Russia, the government began to actively encourage the proliferation of arts and sciences in the mid-18th century. This era produced the first Russian university, library, theater, public museum, and independent press. Several Americans, especially Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, played a major role in bringing Enlightenment ideas to the New World and in influencing British and French thinkers. The cultural exchange during the Age of Enlightenment ran in both directions across the Atlantic. In their development of the ideas of natural freedom, Europeans and American thinkers drew from American Indian cultural practices and beliefs.

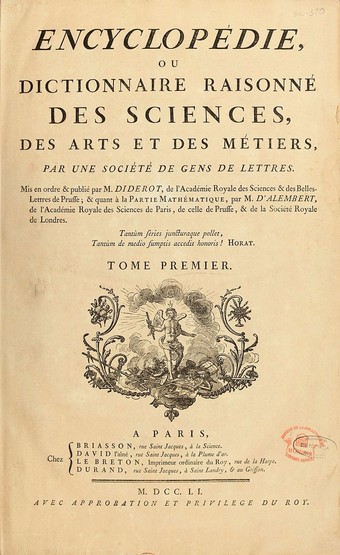

First page of the Encyclopedie published between 1751 and 1766.

The prime example of reference works that systematized scientific knowledge in the Age of Enlightenment were universal encyclopedias rather than technical dictionaries. It was the goal of universal encyclopedias to record all human knowledge in a comprehensive reference work. The most well-known of these works is Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. The work, which began publication in 1751, was composed of thirty-five volumes and over 71,000 separate entries. A great number of the entries were dedicated to describing the sciences and crafts in detail, and provided intellectuals across Europe with a high-quality survey of human knowledge.

Major Enlightenment Ideas

In

the mid-18th century, Europe witnessed an explosion of philosophic and

scientific activity that challenged traditional doctrines and dogmas. The

philosophic movement was led by Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who argued

for a society based upon reason rather than faith and Catholic doctrine, for a

new civil order based on natural law, and for science based on experiments and

observation. The political philosopher Montesquieu introduced the idea of a

separation of powers in a government, a concept which was enthusiastically

adopted by the authors of the United States Constitution.

There

were two distinct lines of Enlightenment thought. The radical enlightenment,

inspired by the philosophy of Spinoza, advocated democracy, individual

liberty, freedom of expression, and eradication of religious authority. A second,

more moderate variety, supported by René Descartes, John Locke, Christian

Wolff, Isaac Newton and others, sought accommodation between reform and the

traditional systems of power and faith.

Science came to play a leading role in Enlightenment discourse and

thought. Many Enlightenment writers and thinkers had backgrounds in the

sciences and associated scientific advancement with the overthrow of religion

and traditional authority in favor of the development of free speech and

thought. Broadly speaking, Enlightenment science greatly valued empiricism and

rational thought and was embedded with the Enlightenment ideal of advancement

and progress. However, as with most Enlightenment views, the benefits of science were

not seen universally.

The

Enlightenment has also long been hailed as the foundation of modern Western

political and intellectual culture. It brought political modernization to the

West in terms of focusing on democratic values and institutions and the

creation of modern, liberal democracies. The fundamentals of European liberal thought, including the

right of the individual, the natural equality of all men, the separation of powers, the artificial

character of the political order (which led to the later distinction between

civil society and the state), the view that all legitimate political power must

be “representative” and based on the consent of the people, and liberal interpretation of law that leaves people free to do whatever is not explicitly forbidden, were all developed by Enlightenment thinkers.

In religion, Enlightenment-era commentary was a response to the preceding century of religious

conflict in Europe. Enlightenment thinkers sought to curtail the political

power of organized religion and thereby prevent another age of intolerant

religious war. A number of novel ideas developed, including deism (belief in

God the Creator, with no reference to the Bible or any other source) and

atheism. The latter was much discussed but had few proponents. Many,

like Voltaire, held that without belief in a God who punishes evil, the moral

order of society was undermined.

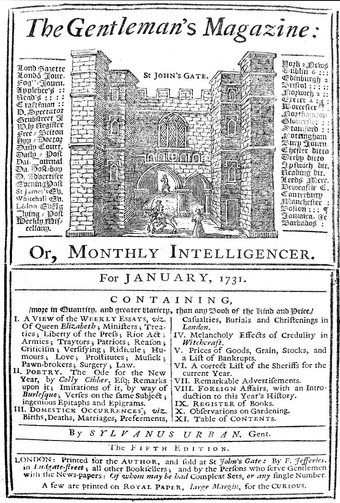

Front page of The Gentleman’s Magazine, founded by Edward Cave in London in January 1731.

The increased consumption of reading materials of all sorts was one of the key features of the “social” Enlightenment. The Industrial Revolution allowed consumer goods to be produced in greater quantities at lower prices, encouraging the spread of books, pamphlets, newspapers, and journals. Cave’s innovation was to create a monthly digest of news and commentary on any topic the educated public might be interested in, from commodity prices to Latin poetry.

Impact

The

ideas of the Enlightenment played a major role in inspiring the French

Revolution, which began in 1789 and emphasized the rights of common men as

opposed to the exclusive rights of the elites. As such, they laid the foundation for modern, rational, democratic societies. However, historians of race,

gender, and class note that Enlightenment ideals were not originally envisioned

as universal in the today’s sense of the word. Although they did eventually

inspire the struggles for rights of people of color, women, or the working

masses, most Enlightenment thinkers did not advocate equality for all, regardless of

race, gender, or class, but rather insisted that rights and freedoms were not

hereditary (the heredity of power and rights was a common pre-Enlightenment assumption). This perspective directly attacked the traditionally exclusive

position of the European aristocracy but was still largely focused on expanding

the rights of white males of a particular social standing.

21.1.2: Scientific Exploration

Science, based on empiricism and rational thought and embedded with the Enlightenment ideal of advancement and progress, came to play a leading role in the movement’s discourse and thought.

Learning Objective

Describe advancements made in science and social sciences during the 18th century

Key Points

-

Science came to play a leading role in Enlightenment discourse and ideas. The movement greatly valued empiricism and rational thought

and was embedded with the Enlightenment ideal of advancement and progress.

Similar rules were applied to social sciences. -

Building on the body of work forwarded by Copernicus, Kepler and

Newton, 18th-century astronomers refined telescopes, produced star catalogs,

and worked towards explaining the motions of heavenly bodies and the

consequences of universal gravitation. In 1781, amateur astronomer William

Herschel was responsible for arguably the most important discovery in

18th-century astronomy: a new planet later named Uranus. -

The 18th century witnessed the early modern reformulation of

chemistry that culminated in the law of conservation of mass and the

oxygen theory of combustion. -

David Hume and other Scottish Enlightenment thinkers developed a “science of man.” Against philosophical rationalists, Hume held that passion

rather than reason governs human behavior and argued against the existence of

innate ideas, positing that all human knowledge is ultimately founded solely in

experience. Modern sociology largely originated from these ideas. -

Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations, often

considered the first work on modern economics, in 1776. It had an immediate

impact on British economic policy that continues into the 21st century.

Enlightenment-era changes in law also continue to shape legal systems today. -

The Age of Enlightenment was also when the first scientific and

literary journals were established. As a source of knowledge derived from

science and reason, these journals were an implicit critique of existing notions

of universal truth monopolized by monarchies, parliaments, and religious

authorities.

Key Terms

- chemical revolution

-

The 18th-century reformulation of chemistry that culminated in the law of conservation of mass and the oxygen theory of combustion. During the 19th and 20th century, this transformation was credited to the work of the French chemist Antoine Lavoisier (the “father of modern chemistry”). However, recent research notes that gradual changes in chemical theory and practice emerged over two centuries.

- science of man

-

A topic in David Hume’s 18th century experimental philosophy A Treatise of Human Nature (1739). It expanded the understanding of facets of human nature, including senses, impressions, ideas, imagination, passions, morality, justice, and society.

- empiricism

-

The theory that

knowledge comes primarily from sensory experience. It emphasizes

evidence gathered through

experimentation and by use of the scientific method.

While

the Enlightenment cannot be pigeonholed into a specific doctrine or set of

dogmas, science is a key part of the ideals of this movement. Many Enlightenment writers and thinkers had backgrounds in the

sciences and associated scientific advancement with the overthrow of religion

and traditional authority in favor of the development of free speech and

thought. Broadly speaking, Enlightenment science greatly valued empiricism and

rational thought, embedded with the ideals of advancement

and progress. Similar rules were applied to social sciences.

Astronomy

Building on the body of work forwarded by Copernicus, Kepler and Newton, 18th-century astronomers refined telescopes, produced star catalogs, and worked towards explaining the motions of heavenly bodies and the consequences of universal gravitation. In 1705, astronomer Edward Halley correctly linked historical descriptions of particularly bright comets to the reappearance of just one (later named Halley’s Comet), based on his computation of the orbits of comets. James Bradley realized that the unexplained motion of stars he had early observed with Samuel Molyneux was caused by the aberration of light. He also came fairly close to the estimation of the speed of light. Observations of Venus in the 18th century became an important step in describing atmospheres, including the work of Mikhail Lomonosov, Johann Hieronymus Schröter, and Alexis Claude de Clairaut. In 1781, amateur astronomer William Herschel was responsible for arguably the most important discovery in 18th-century astronomy. He spotted a new planet that he named Georgium Sidus. The name Uranus, proposed by Johann Bode, came into widespread usage after Herschel’s death. On the theoretical side of astronomy, the English natural philosopher John Michell first proposed the existence of dark stars in 1783.

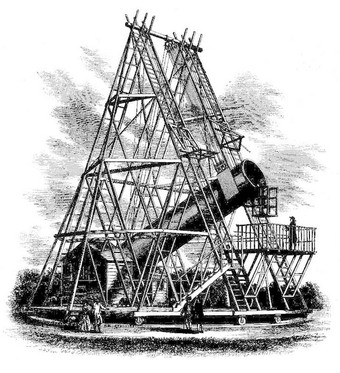

William Herschel’s 40 foot (12 m) telescope. Scanned from Leisure Hour, Nov 2,1867, page 729.

Much astronomical work of the period becomes shadowed by one of the most dramatic scientific discoveries of the 18th century. On March 13, 1781, amateur astronomer William Herschel spotted a new planet with his powerful reflecting telescope. Initially identified as a comet, the celestial body later came to be accepted as a planet. Soon after, the planet was named Georgium Sidus by Herschel and was called Herschelium in France. The name Uranus, as proposed by Johann Bode, came into widespread usage after Herschel’s death.

Chemistry

The 18th century witnessed the early modern reformulation of chemistry that culminated in the law of conservation of mass and the oxygen theory of combustion. This period was eventually called the chemical revolution. According to an earlier theory, a substance called phlogiston was released from inflammable materials through burning. The resulting product was termed calx, which was considered a dephlogisticated substance in its true form. The first strong evidence against phlogiston theory came from Joseph Black, Joseph Priestley, and Henry Cavendish, who all identified different gases that composed air. However, it was not until Antoine Lavoisier discovered in 1772 that sulphur and phosphorus grew heavier when burned that the phlogiston theory began to unravel. Lavoisier subsequently discovered and named oxygen, as well as described its roles in animal respiration and the calcination of metals exposed to air (1774–1778). In 1783, he found that water was a compound of oxygen and hydrogen. Transition to and acceptance of Lavoisier’s findings varied in pace across Europe. Eventually, however, the oxygen-based theory of combustion drowned out the phlogiston theory and in the process created the basis of modern chemistry.

Social Sciences

David Hume and other Scottish Enlightenment thinkers developed a “science of man” that was expressed historically in works by authors including James Burnett, Adam Ferguson, John Millar, and William Robertson, all of whom merged a scientific study of how humans behaved in prehistoric and ancient cultures with a strong awareness of the determining forces of modernity. Against philosophical rationalists, Hume held that passion rather than reason governs human behavior and argued against the existence of innate ideas, positing that all human knowledge is ultimately founded solely in experience. According to Hume, genuine knowledge must either be directly traceable to objects perceived in experience or result from abstract reasoning about relations between ideas derived from experience.

Modern sociology largely originated from the science of ma’ movement.

Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations, often considered the first work on modern economics, in 1776. It had an immediate impact on British economic policy that continues into the 21st century. The book was immediately preceded and influenced by Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot and Baron de Laune drafts of Reflections on the Formation and Distribution of Wealth (Paris, 1766). Smith acknowledged indebtedness to this work and may have been its original English translator.

Enlightenment-era changes in law also continue to shape legal systems today. Cesare Beccaria, a jurist and one of the great Enlightenment writers, published his masterpiece Of Crimes and Punishments in 1764. Beccaria is recognized as one of the fathers of classical criminal theory. His treatise condemned torture and the death penalty and was a founding work in the field of penology (the study of the punishment of crime and prison management). It also promoted criminal justice.

Another prominent intellectual was Francesco Mario Pagano, whose work Saggi Politici (Political Essays, 1783)

argued against torture and capital punishment and advocated more benign penal codes.

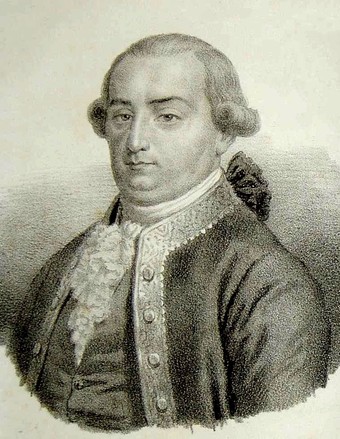

Portrait of

Cesare Bonesana-Beccaria

Although less widely known to the general public than his fellow English, Scottish, or French philosophers of the era, Beccaria remains one of the greatest thinkers of the Enlightenment era.

His theories have continued to play a great role in recent times. Some of the current policies impacted by his theories are truth in sentencing, swift punishment and the abolition of death penalty. While many of his theories are popular, some are still a source of heated controversy, more than two centuries after Beccaria’s death.

Scientific Publications

The Age of Enlightenment was also when the first scientific and literary journals were established. The first journal, the Parisian Journal des Sçavans, appeared in 1665. However, it was not until 1682 that periodicals began to be more widely produced. French and Latin were the dominant languages of publication, but there was also a steady demand for material in German and Dutch. There was generally low demand for English publications on the Continent, which was echoed by England’s similar lack of desire for French works. Languages commanding less of an international market such as Danish, Spanish, and Portuguese found journal success more difficult and often used an international language instead. French slowly took over Latin’s status as the lingua franca of learned circles. This in turn gave precedence to the publishing industry in Holland, where the vast majority of these French language periodicals were produced. As a source of knowledge derived from science and reason, the journals were an implicit critique of existing notions of universal truth monopolized by monarchies, parliaments, and religious authorities.

21.1.3: The Popularization of Science

Scientific societies and academies and the unprecedented popularization of science among an increasingly literate population dominated the Age of Enlightenment.

Learning Objective

Describe advancements made in the popularization of science during the 18th century

Key Points

-

Science during the Enlightenment was dominated

by scientific societies and academies, which largely replaced universities

as centers of scientific research and development. Scientific academies and

societies grew out of the Scientific Revolution as the creators of scientific

knowledge in contrast to the scholasticism of the university. -

National scientific societies were founded

throughout the Enlightenment era in the urban hotbeds of scientific development

across Europe. Many regional and provincial

societies followed along with some smaller private counterparts. Activities included research, experimentation, sponsoring

essay contests, and collaborative projects between societies. -

Academies and societies disseminated Enlightenment science by publishing the works of their members. The publication schedules were typically irregular, with periods between volumes sometimes lasting years. While the journals of the academies primarily published scientific

papers, the independent periodicals that followed were a mix of reviews, abstracts, translations

of foreign texts, and sometimes derivative, reprinted materials. -

Although dictionaries and

encyclopedias have existed since ancient times, during the Enlightenment they evolved from a simple list of definitions to far more detailed discussions of those words. The most well-known of the 18th century encyclopedic dictionaries is Encyclopaedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of

the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts. -

During the Enlightenment, science began to appeal to an increasingly larger audience. A more literate population seeking

knowledge and education in both the arts and the sciences drove the expansion

of print culture and the dissemination of scientific learning in coffeehouses, at public lectures, and through popular publications. -

During

the Enlightenment era, women were excluded from scientific societies,

universities, and learned professions. Despite

these limitations, many women made valuable contributions to science during the

18th century.

Key Terms

- Encyclopaedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts

-

A general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised editions, and translations. It had many writers, known as the Encyclopédistes, and was edited by Denis Diderot and until 1759 co-edited by Jean le Rond d’Alembert. It is most famous for representing the thought of the Enlightenment.

- Scientific Revolution

-

The emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transformed society’s views about nature. It began in Europe towards the end of the Renaissance period and continued through the late 18th century, influencing the intellectual social movement known as the Enlightenment. While its dates are disputed, the publication of Nicolaus Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) in 1543 is often cited as its beginning.

- Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds

-

A popular science book by French author Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle published in 1686. It offered an explanation of the heliocentric model of the Universe, suggested by Nicolaus Copernicus in his 1543 work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium. The book, written in French and not in Latin as most scientific works of the era, was one of the first attempts to explain scientific theories in a popular language understandable to the wide audience.

Societies and Academies

Science during the Enlightenment was dominated by scientific societies and academies, which largely replaced universities as centers of scientific research and development.

These organizations grew out of the Scientific Revolution as the creators of scientific knowledge in contrast to the scholasticism of the university. During the Enlightenment, some societies created or retained links to universities. However, contemporary sources distinguished universities from scientific societies by claiming that the university’s utility was in the transmission of knowledge, while societies functioned to create knowledge. As the role of universities in institutionalized science began to diminish, learned societies became the cornerstone of organized science. After 1700, many official academies and societies were founded in Europe, with more than seventy official scientific societies in existence by 1789. In reference to this growth, Bernard de Fontenelle coined the term “the Age of Academies” to describe the 18th century.

National scientific societies were founded in the urban hotbeds of scientific development across Europe. In the 17th century, the Royal Society of London (1662), the Paris Académie Royale des Sciences (1666), and the Berlin Akademie der Wissenschaften (1700) came into existence. In the first half of the 18th century, the Academia Scientiarum Imperialis (1724) in St. Petersburg, and the Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien (Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences) (1739) were created. Many regional and provincial societies followed along with some smaller private counterparts. Official scientific societies were chartered by the state to provide technical expertise, which resulted in direct, close contact between the scientific community and government bodies. State sponsorship was beneficial to the societies as it brought finance and recognition along with a measure of freedom in management. Most societies were granted permission to oversee their own publications, control the election of new members, and otherwise provide administration. Membership in academies and societies was highly selective. Activities included research, experimentation, sponsoring essay contests, and collaborative projects between societies.

Scientific and Popular Publications

Academies and societies served to disseminate Enlightenment science by publishing the scientific works of their members as well as their proceedings. With the exception of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society by the Royal Society of London, which was published on a regular, quarterly basis, publication schedules were typically irregular, with periods between volumes sometimes lasting years. These and other limitations of academic journals left considerable space for the rise of independent periodicals, which excited scientific interest in the general public. While the journals of the academies primarily published scientific papers, independent periodicals were a mix of reviews, abstracts, translations of foreign texts, and sometimes derivative, reprinted materials. Most of these texts were published in the local vernacular, so their continental spread depended on the language of the readers. For example, in 1761, Russian scientist Mikhail Lomonosov correctly attributed the ring of light around Venus, visible during the planet’s transit, as the planet’s atmosphere. However, because few scientists understood Russian outside of Russia, his discovery was not widely credited until 1910. With a wider audience and ever-increasing publication material, specialized journals emerged, reflecting the growing division between scientific disciplines in the Enlightenment era.

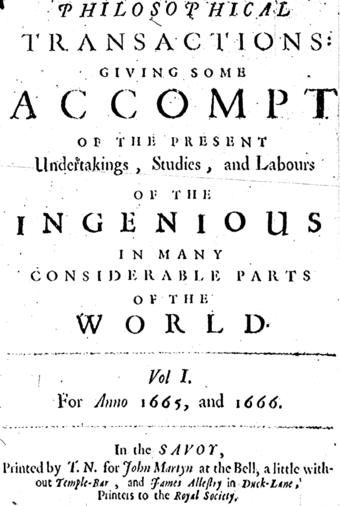

Cover of the first volume of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 1665-1666, the Royal Society of London.

The Philosophical Transactions was established in 1665 as the first journal in the world exclusively devoted to science. It is still published by the Royal Society, which also makes it the world’s longest-running scientific journal. The use of the word “Philosophical” in the title refers to “natural philosophy,” which was the equivalent of what would now be generally called science.

Although dictionaries and encyclopedias have existed since ancient times, they evolved from simply a long list of definitions to detailed discussions of those words in 18th-century encyclopedic dictionaries. The works were part of an Enlightenment movement to systematize knowledge and provide education to a wider audience than the educated elite. As the 18th century progressed, the content of encyclopedias also changed according to readers’ tastes. Volumes tended to focus more strongly on secular affairs, particularly science and technology, rather than on matters of theology. The most well-known of these works is Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert’s

Encyclopaedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts. The work, which began publication in 1751, was composed of thirty-five volumes and more than 71,000 separate entries. Many entries describe the sciences and crafts in detail. The massive work was arranged according to a “tree of knowledge.” The tree reflected the marked division between the arts and sciences, largely a result of the rise of empiricism. Both areas of knowledge were united by philosophy, the trunk of the tree of knowledge.

Science and the Public

During Enlightenment, the discipline of science began to appeal to a consistently growing audience. An increasingly literate population seeking knowledge and education in both the arts and the sciences drove the expansion of print culture and the dissemination of scientific learning.

The British coffeehouse is an early example of this phenomenon, as their establishment created a new public forum for political, philosophical, and scientific discourse. In the mid-16th century, coffeehouses cropped up around Oxford, where the academic community began to capitalize on the unregulated conversation the coffeehouse allowed. The new social space was used by some scholars as a place to discuss science and experiments outside the laboratory of the official institution. Education was a central theme, and some patrons began offering lessons to others. As coffeehouses developed in London, customers heard lectures on scientific subjects such as astronomy and mathematics for an exceedingly low price.

Public lecture courses offered scientists unaffiliated with official organizations a forum to transmit scientific knowledge and their own ideas, leading to the opportunity to carve out a reputation and even make a living. The public, on the other hand, gained both knowledge and entertainment from demonstration lectures. Courses varied in duration from one to four weeks to a few months or even the entire academic year and were offered at virtually any time of day. The importance of the lectures was not in teaching complex scientific subjects, but rather in demonstrating the principles of scientific disciplines and encouraging discussion and debate.

Barred from the universities and other institutions, women were often in attendance at demonstration lectures and constituted a significant number of auditors.

Increasing literacy rates in Europe during the Enlightenment enabled science to enter popular culture through print. More formal works included explanations of scientific theories for individuals lacking the educational background to comprehend the original scientific text. The publication of Bernard de Fontenelle’s Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds (1686) marked the first significant work that expressed scientific theory and knowledge expressly for the laity, in the vernacular and with the entertainment of readers in mind. The book specifically addressed women with an interest in scientific writing and inspired a variety of similar works written in a discursive style. These were more accessible to the reader than complicated articles, treatises, and books published by the academies and scientists.

Science and Gender

During the Enlightenment, women were excluded from scientific societies, universities, and learned professions. They were educated, if at all, through self-study, tutors, and by the teachings of more open-minded family members and relatives. With the exception of daughters of craftsmen, who sometimes learned their fathers’ professions by assisting in the workshop, learned women were primarily part of elite society. In addition, women’s inability to access scientific instruments (e.g., microscope) made it difficult for them to conduct independent research.

Despite these limitations, many women made valuable contributions to science during the 18th century. Two notable women who managed to participate in formal institutions were Laura Bassi and the Russian Princess Yekaterina Dashkova. Bassi was an Italian physicist who received a PhD from the University of Bologna and began teaching there in 1732. Dashkova became the director of the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences of St. Petersburg in 1783. Her personal relationship with Empress Catherine the Great allowed her to obtain the position, which marked in history the first appointment of a woman to the directorship of a scientific academy. More commonly, however, women participated in the sciences as collaborators of their male relative or spouse.

Others became illustrators or translators of scientific texts.

Portrait of M. and Mme Lavoisier, by Jacques-Louis David, 1788, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Women usually participated in the sciences through an association with a male relative or spouse. For example, Marie-Anne Pierette Paulze worked collaboratively with her husband, Antoine Lavoisier. Aside from assisting in Lavoisier’s laboratory research, she was responsible for translating a number of English texts into French for her husband’s work on the new chemistry. Paulze also illustrated many of her husband’s publications, such as his Treatise on Chemistry (1789).

21.1.4: Enlightened Despotism

Enlightened despots, inspired by the ideals of the Age of Enlightenment, held that royal power

emanated not from divine right but from a social contract whereby a despot was

entrusted with the power to govern in lieu of any other

governments.

Learning Objective

Define enlightened despotism and provide examples

Key Points

-

Enlightened despots held that royal power

emanated not from divine right but from a social contract whereby a despot was

entrusted with the power to govern in lieu of any other

governments. In effect, the monarchs of enlightened absolutism strengthened

their authority by improving the lives of their subjects. - An essay defending the system of enlightened despotism was penned by Frederick the Great, who ruled Prussia from 1740 to 1786. Frederick modernized

the Prussian bureaucracy and civil service and pursued religious policies

throughout his realm that ranged from tolerance to segregation. Following the common interest among enlightened despots,

he supported arts, philosophers that he favored, and complete freedom of

the press and literature. - Catherine II of Russia continued to modernize Russia along

Western European lines, but her enlightened despotism manifested itself mostly

with her commitment to arts, sciences, and the modernization of Russian

education. While she introduced some administrative and economic reforms, military conscription and economy

continued to depend on serfdom. -

Maria Theresa implemented

significant reforms to strengthen Austria’s military and bureaucratic

efficiency. She improved the economy of the state, introduced a national education system, and contributed to important reforms in medicine. However, unlike other enlightened despots, Maria Theresa found it hard to

fit into the intellectual sphere of the Enlightenment and did not share fascination with Enlightenment ideals. - Joseph

was a proponent of enlightened despotism but his commitment to modernizing

reforms subsequently engendered significant opposition, which eventually

culminated in a failure to fully implement his programs. Among other accomplishments, he inspired a complete reform of the legal system, ended censorship of the press and

theater, and continued his mother’s reforms in education and medicine.

Key Terms

- serfdom

-

The status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism. It was a condition of bondage that developed primarily during the High Middle Ages in Europe and lasted in some countries until the mid-19th century.

- enlightened despotism

-

Also known as enlightened absolutism or benevolent absolutism, a form of absolute monarchy or despotism inspired by the Enlightenment. The monarchs who embraced it followed the participles of rationality. Some of them fostered education and allowed religious tolerance, freedom of speech, and the right to hold private property.

They held that royal power emanated not from divine right but from a social contract whereby a despot was entrusted with the power to govern in lieu of any other governments. - Encyclopédie

-

A general encyclopedia

published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised

editions, and translations. It had many writers, known as the Encyclopédistes.It is most famous for representing the thought of the Enlightenment.

Enlightened Despotism

Major thinkers of the Age of Enlightenment are credited for the development of government theories critical to the creation and evolution of the modern civil-society-driven democratic state. Enlightened despotism, also called enlightened absolutism, was among the first ideas resulting from the political ideals of the Enlightenment.

The concept was formally described by the German historian Wilhelm Roscher in 1847 and remains controversial among scholars.

Enlightened despots held that royal power emanated not from divine right but from a social contract whereby a despot was entrusted with the power to govern in lieu of any other governments. In effect, the monarchs of enlightened absolutism strengthened their authority by improving the lives of their subjects. This philosophy implied that the sovereign knew the interests of his or her subjects better than they themselves did. The monarch taking responsibility for the subjects precluded their political participation. The difference between a despot and an enlightened despot is based on a broad analysis of the degree to which they embraced the Age of Enlightenment. However, historians debate the actual implementation of enlightened despotism. They distinguish between the “enlightenment” of the ruler personally versus that of his or her regime.

Frederick the Great

Enlightened despotism was defended in an essay by Frederick the Great, who ruled Prussia from 1740 to 1786.

He was an enthusiast of French ideas and invited the prominent French Enlightenment philosopher Voltaire to live at his palace.

With the help of French experts, Frederick organized a system of indirect taxation, which provided the state with more revenue than direct taxation.

One of Frederick’s greatest achievements included the control of grain prices, whereby government storehouses would enable the civilian population to survive in needy regions, where the harvest was poor. Frederick modernized the Prussian bureaucracy and civil service and pursued religious policies throughout his realm that ranged from tolerance to segregation.

He was largely non-practicing and tolerated all faiths in his realm, although Protestantism became the favored religion and Catholics were not chosen for higher state positions. While he protected and encouraged trade by Jewish citizens of the Empire, he repeatedly expressed strong anti-Semitic sentiments. He also encouraged immigrants of various nationalities and faiths to come to Prussia. Some critics, however, point out his oppressive measures against conquered Polish subjects after some Polish land fell under the control of the Prussian Empire. Following the common interest among enlightened despots, Frederick supported arts, philosophers that he favored, and complete freedom of the press and literature.

Catherine the Great

Catherine II of Russia was the most renowned and the longest-ruling female leader of Russia, reigning from 1762 until her death in 1796. An admirer of Peter the Great, she continued to modernize Russia along Western European lines but her enlightened despotism manifested itself mostly with her commitment to arts, sciences, and the modernization of Russian education. The Hermitage Museum, which now occupies the whole Winter Palace, began as Catherine’s personal collection. She wrote comedies, fiction, and memoirs, while cultivating Voltaire, Diderot, and d’Alembert—all French encyclopedists who later cemented her reputation in their writings. The leading European economists of her day became foreign members of the Free Economic Society, established on her suggestion in Saint Petersburg in 1765. She also recruited Western European scientists. Within a few months of her accession in 1762, having heard the French government threatened to stop the publication of the famous French Encyclopédie on account of its irreligious spirit, Catherine proposed to Diderot that he should complete his great work in Russia under her protection. She believed a ‘new kind of person’ could be created by instilling Russian children with Western European education. She continued to investigate educational theory and practice of other countries and while she introduced some educational reforms, she failed to establish a national school system.

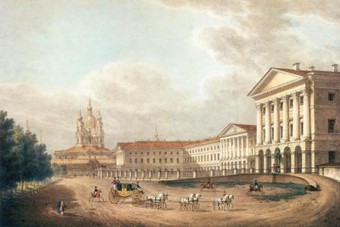

The Smolny Institute, the first Russian institute for “Noble Maidens” and the first European state higher education institution for women, painting by S.F. Galaktionov, 1823.

Catherine established the Smolny Institute for Noble Girls to educate females. At first, the Institute only admitted young girls of the noble elite, but eventually it began to admit girls of the petit-bourgeoisie, as well. The girls who attended the Smolny Institute, Smolyanki, were often accused of being ignorant of anything that went on in the world outside the walls of the Smolny buildings. Within the walls of the Institute, they were taught impeccable French, musicianship, dancing, and complete awe of the Monarch.

Although Catherine refrained from putting most democratic principles into practice, she issued codes addressing some modernization trends, including dividing the country into provinces and districts, limiting the power of nobles, creating a middle estate, and a number of economic reforms. However, military conscription and economy continued to depend on serfdom, and the increasing demands of the state and private landowners led to increased levels of reliance on serfs.

Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa was the only female ruler of the Habsburg dominions and the last of the House of Habsburg.

She implemented significant reforms to strengthen Austria’s military and bureaucratic efficiency. She doubled the state revenue between 1754 and 1764, though her attempt to tax clergy and nobility was only partially successful. Nevertheless, her financial reforms greatly improved the economy. In 1760, Maria Theresa created the council of state, which served as a committee of expert advisors. It lacked executive or legislative authority but nevertheless showed the difference between the autocratic form of government. In medicine, her decision to have her children inoculated after the smallpox epidemic of 1767 was responsible for changing Austrian physicians’ negative view of vaccination. Austria outlawed witch burning and torture in 1776. It was later reintroduced, but the progressive nature of these reforms remains noted. Education was one of the most notable reforms of Maria Theresa’s rule. In a new school system based on that of Prussia, all children of both genders from the ages were required to attend school from the ages of 6 to 12, although the law turned out to be very difficult to execute.

However, Maria Theresa found it hard to fit into the intellectual sphere of the Enlightenment. For example, she believed that religious unity was necessary for a peaceful public life and explicitly rejected the idea of religious tolerance.

She regarded both the Jews and Protestants as dangerous to the state and actively tried to suppress them. As a young monarch who fought two dynastic wars, she believed that her cause should be the cause of her subjects, but in her later years she would believe that their cause must be hers.

Joseph II of Austria

Maria Theresa’s oldest son, Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor from 1765 to 1790 and ruler of the Habsburg lands from 1780 to 1790, was at ease with Enlightenment ideas. Joseph was a proponent of enlightened despotism, but his commitment to modernizing reforms engendered significant opposition, which eventually culminated in a failure to fully implement his programs.

Joseph inspired a complete reform of the legal system, abolished brutal punishments and the death penalty in most instances, and imposed the principle of complete equality of treatment for all offenders. He ended censorship of the press and theater. In 1781–82, he extended full legal freedom to serfs. The landlords, however, found their economic position threatened and eventually reversed the policy. To equalize the incidence of taxation, Joseph ordered an appraisal of all the lands of the empire to impose a single egalitarian tax on land. However, most of his financial reforms were repealed shortly before or after Joseph’s death in 1790.

To produce a literate citizenry, elementary education was made compulsory for all boys and girls and higher education on practical lines was offered for a select few. Joseph created scholarships for talented poor students and allowed the establishment of schools for Jews and other religious minorities. In 1784, he ordered that the country change its language of instruction from Latin to German, a highly controversial step in a multilingual empire. Joseph also attempted to centralize medical care in Vienna through the construction of a single, large hospital, the famous Allgemeines Krankenhaus, which opened in 1784. Centralization, however, worsened sanitation problems, causing epidemics and a 20% death rate in the new hospital, but the city became preeminent in the medical field in the next century.

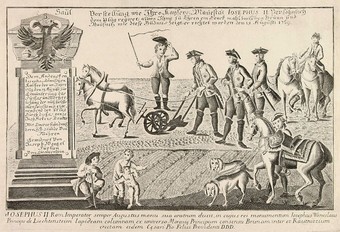

Joseph II is plowing the field near Slawikowitz in rural southern Moravia on 19 August 1769.

Joseph II was one of the first rulers in Central Europe. He attempted to abolish serfdom but his plans met with resistance from the landholders. His Imperial Patent of 1785 abolished serfdom on some territories of the Empire, but under the pressure of the landlords did not give the peasants ownership of the land or freedom from dues owed to the landowning nobles. It did give them personal freedom. The final emancipation reforms in the Habsburg Empire were introduced in 1848.

Probably the most unpopular of all his reforms was his attempted modernization of the highly traditional Catholic Church. Calling himself the guardian of Catholicism, Joseph II struck vigorously at papal power. He tried to make the Catholic Church in his empire the tool of the state, independent of Rome.

Joseph was very friendly to Freemasonry, as he found it highly compatible with his own Enlightenment philosophy, although he apparently never joined the Lodge himself. In 1789, he issued a charter of religious toleration for the Jews of Galicia, a region with a large Yiddish-speaking traditional Jewish population. The charter abolished communal autonomy whereby the Jews controlled their internal affairs. It promoted Germanization and the wearing of non-Jewish clothing.

21.2: Frederick the Great and Prussia

21.2.1: The Hohenzollerns

The Hohenzollern family split into two branches, the Catholic Swabian branch and the Protestant Franconian branch. The latter

transformed from a minor German princely

family into one of the most important dynasties in Europe.

Learning Objective

Explain who the Hohenzollerns were and the progression of their relationship with and status within the Holy Roman Empire.

Key Points

-

The House of Hohenzollern is a dynasty of

Hohenzollern, Brandenburg, Prussia, the German Empire, and Romania. The family

arose in the area around the town of Hechingen in Swabia during the 11th

century. The family split into two branches,

the Catholic Swabian branch and the Protestant Franconian branch, which later

became the Brandenburg-Prussian branch. -

The

Margraviate of Brandenburg was a major principality of the Holy Roman Empire

from 1157 to 1806. It played a pivotal

role in the history of Germany and Central Europe.

The House of Hohenzollern came to the throne of Brandenburg in 1415. Frederick

VI of Nuremberg was officially recognized as Margrave and Prince-elector

Frederick I of Brandenburg at the Council of Constance in 1415. -

When

Duke of Prussia

Albert Frederick died in 1618 without having had a son, his son-in-law John

Sigismund, at the time the prince-elector of the Margraviate of

Brandenburg, inherited the Duchy of Prussia. He then ruled both territories in

a personal union that came to be known as Brandenburg-Prussia. Prussia lay

outside the Holy Roman Empire and the electors of Brandenburg held it as a fief

of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to which the electors paid homage. -

The

electors of Brandenburg spent the next two centuries attempting to gain lands

to unite their separate territories and form one geographically

contiguous domain. In the second half of the 17th century, Frederick William, the

“Great Elector,” developed Brandenburg-Prussia into a major power.

The electors succeeded in acquiring full sovereignty over Prussia in

1657. -

In return for aiding Emperor Leopold I during

the War of the Spanish Succession, Frederick William’s son, Frederick III, was

allowed to elevate Prussia to the status of a kingdom. In 1701, Frederick

crowned himself Frederick I, King of Prussia. Prussia, unlike Brandenburg, lay

outside the Holy Roman Empire. Legally,

Brandenburg was still part of the Holy Roman Empire so the Hohenzollerns continued to use the additional

title of Elector of Brandenburg for the remainder of the empire’s run. -

The feudal designation of the Margraviate of

Brandenburg ended with the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, which

made the Hohenzollerns de jure as well as de facto sovereigns

over it. It became part of

the German Empire in 1871 during the Prussian-led unification of Germany.

Key Terms

- personal union

-

The combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. It differs from a federation in that each constituent state has an independent government, whereas a unitary state is united by a central government. Its ruler does not need to be a hereditary monarch.

- fief

-

The central element of feudalism, consisting of heritable property or rights granted by an overlord to a vassal who held it in fealty (or “in fee”) in return for a form of feudal allegiance and service, usually given by the personal ceremonies of homage and fealty. The fees were often lands or revenue-producing real property held in feudal land tenure.

- The House of Hohenzollern

-

A dynasty of Hohenzollern, Brandenburg, Prussia, the German Empire, and Romania. The family arose in the area around the town of Hechingen in Swabia during the 11th century and took their name from the Hohenzollern Castle. The family split into two branches, the Catholic Swabian branch and the Protestant Franconian branch, which later became the Brandenburg-Prussian branch.

- The Margraviate of Brandenburg

-

A major principality of the Holy Roman Empire from 1157 to 1806. Also known as the March of Brandenburg, it played a pivotal role in the history of Germany and Central Europe. Its ruling margraves were established as prestigious prince-electors in the Golden Bull of 1356, allowing them to vote in the election of the Holy Roman Emperor.

- the Golden Bull of 1356

-

A decree issued by the Imperial Diet at Nuremberg and Metz headed by the Emperor Charles IV, which fixed, for a period of more than four hundred years, important aspects of the constitutional structure of the Holy Roman Empire.

House of Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern is a dynasty of Hohenzollern, Brandenburg, Prussia, the German Empire, and Romania. The family arose in the area around the town of Hechingen in Swabia during the 11th century and took their name from the Hohenzollern Castle. The first ancestor of the Hohenzollerns was mentioned in 1061, but the family split into two branches, the Catholic Swabian branch and the Protestant Franconian branch, which later became the Brandenburg-Prussian branch. The Swabian branch ruled the principalities of Hohenzollern-Hechingen and Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen (both fiefs of the Holy Roman Empire) until 1849 and ruled Romania from 1866 to 1947. The cadet Franconian branch of the House of Hohenzollern was founded by Conrad I, Burgrave of Nuremberg (1186-1261). Beginning in the 16th century, this branch of the family became Protestant and decided on expansion through marriage and the purchase of surrounding lands. The family supported the Hohenstaufen and Habsburg rulers of the Holy Roman Empire during the 12th to 15th centuries and was rewarded with several territorial grants. In the first phase, the family gradually added to their lands, at first with many small acquisitions in the Franconian region of Germany (Ansbach in 1331 and Kulmbach in 1340). In the second phase, the family expanded further with large acquisitions in the Brandenburg and Prussian regions of Germany and current Poland (Margraviate of Brandenburg in 1417 and Duchy of Prussia in 1618). These acquisitions eventually transformed the Hohenzollerns from a minor German princely family into one of the most important dynasties in Europe.

Margraviate of Brandenburg

The Margraviate of Brandenburg was a major principality of the Holy Roman Empire from 1157 to 1806. Also known as the March of Brandenburg, it played a pivotal role in the history of Germany and Central Europe. Its ruling margraves were established as prestigious prince-electors in the Golden Bull of 1356, allowing them to vote in the election of the Holy Roman Emperor. The state thus became additionally known as Electoral Brandenburg or the Electorate of Brandenburg. The House of Hohenzollern came to the throne of Brandenburg in 1415. Frederick VI of Nuremberg was officially recognized as Margrave and Prince-elector Frederick I of Brandenburg at the Council of Constance in 1415.

Portrait of Frederick I, Elector of Brandenburg, also called Frederick VI of Nuremberg

In 1411 Frederick VI, Burgrave of Nuremberg was appointed governor of Brandenburg in order to restore order and stability. At the Council of Constance in 1415, King Sigismund elevated Frederick to the rank of Elector and Margrave of Brandenburg as Frederick I.

Frederick made Berlin his residence, although he retired to his Franconian possessions in 1425. He granted governance of Brandenburg to his eldest son John the Alchemist while retaining the electoral dignity for himself. The next elector, Frederick II, forced the submission of Berlin and Cölln, setting an example for the other towns of Brandenburg. He reacquired the Neumark from the Teutonic Knights and began its rebuilding. Brandenburg accepted the Protestant Reformation in 1539. The population has remained largely Lutheran since, although some later electors converted to Calvinism. At the end of the Thirty Years’ War in 1648, Brandenburg was recognized as the possessor of territories, which were more than 100 kilometers from the borders of Brandenburg and formed the nucleus of the later Prussian Rhineland.

Brandenburg-Prussia

When Duke of Prussia Albert Frederick died in 1618 without having had a son, his son-in-law John Sigismund, at the time the prince-elector of the Margraviate of Brandenburg, inherited the Duchy of Prussia. He then ruled both territories in a personal union that came to be known as Brandenburg-Prussia. Prussia lay outside the Holy Roman Empire and the electors of Brandenburg held it as a fief of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to which the electors paid homage.

The electors of Brandenburg spent the next two centuries attempting to gain lands to unite their separate territories (the Mark Brandenburg, the territories in the Rhineland and Westphalia, and Ducal Prussia) and form one geographically contiguous domain. In the Peace of Westphalia ending the Thirty Years’ War in 1648, Brandenburg-Prussia acquired Farther Pomerania and made it the Province of Pomerania. In the second half of the 17th century, Frederick William, the “Great Elector,” developed Brandenburg-Prussia into a major power. The electors succeeded in acquiring full sovereignty over Prussia in 1657.

Kingdom of Prussia

In return for aiding Emperor Leopold I during the War of the Spanish Succession, Frederick William’s son, Frederick III, was allowed to elevate Prussia to the status of a kingdom. In 1701, Frederick crowned himself Frederick I, King of Prussia. Prussia, unlike Brandenburg, lay outside the Holy Roman Empire, within which only the emperor and the ruler of Bohemia could call themselves king. As king was a more prestigious title than prince-elector, the territories of the Hohenzollerns became known as the Kingdom of Prussia, although their power base remained in Brandenburg. Legally, Brandenburg was still part of the Holy Roman Empire, ruled by the Hohenzollerns in personal union with the Prussian kingdom over which they were fully sovereign. For this reason, the Hohenzollerns continued to use the additional title of Elector of Brandenburg for the remainder of the empire’s run. However, by this time the emperor’s authority over the empire had become merely nominal. The various territories of the empire acted more or less as de facto sovereign states and only acknowledged the emperor’s overlordship over them in a formal way. For this reason, Brandenburg soon came to be treated as de facto part of the Prussian kingdom rather than a separate entity.

From 1701 to 1946, Brandenburg’s history was largely that of the state of Prussia, which established itself as a major power in Europe during the 18th century. King Frederick William I of Prussia, the “Soldier-King,” modernized the Prussian Army, while his son Frederick the Great achieved glory and infamy with the Silesian Wars and Partitions of Poland. The feudal designation of the Margraviate of Brandenburg ended with the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, which made the Hohenzollerns de jure as well as de facto sovereigns over it. It was replaced with the Province of Brandenburg in 1815 following the Napoleonic Wars. Brandenburg, along with the rest of Prussia, became part of the German Empire in 1871 during the Prussian-led unification of Germany.

21.2.2: Frederick the Great

In his youth, Frederick the Great was a sensitive man with great appreciation for intellectual development, arts, and education. Despite his father’s fears, this did not prevent him from becoming a brilliant military strategist during his later reign as King of Prussia.

Learning Objective

Describe elements of Frederick II’s upbringing and his transformation into a Prussian leader

Key Points

-

Frederick,

the son of Frederick William I and his wife Sophia Dorothea of Hanover, was

born in Berlin in 1712. He was brought up by Huguenot governesses and tutors and learned French

and German simultaneously. In spite of his father’s desire that his education

be entirely religious and pragmatic, the young Frederick preferred music, literature, and

French culture, which clashed with his father’s militarism. -

Frederick found an ally in his sister,

Wilhelmine, with whom he remained close for life. At age 16, he formed an

attachment to the king’s 13-year-old page, Peter Karl Christoph Keith. Margaret

Goldsmith, a biographer of Frederick’s, suggests the attachment was of a sexual

nature and as a result Keith was sent away and Frederick temporarily relocated. -

When

he was 18, Frederick plotted to flee to England with his close friend Hans Hermann von Katte and other junior

army officers. Frederick and Katte were subsequently arrested and imprisoned in

Küstrin. Because they were army officers who had tried to flee Prussia for

Great Britain, Frederick William leveled an accusation of treason against the

pair. The king forced

Frederick to watch the decapitation of Katte. -

Frederick married

Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Bevern, a Protestant relative of the Austrian

Habsburgs, in 1733. He had little in common with his bride and resented the

political marriage. Once Frederick secured the throne in 1740 after his

father’s death, he immediately separated from his wife. -

Prince Frederick was 28 years old when he acceded to the throne of Prussia. His goal was to modernize and unite

his vulnerably disconnected lands, which he largely succeeded at through

aggressive military and foreign policies. Contrary to his father’s fears, Frederick proved himself a courageous soldier and an extremely skillful

strategist.

Key Terms

- The Prince

-

A 16th-century political treatise by the Italian diplomat and political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli. Machiavelli’s ideas on how to accrue honor and power as a leader had a profound impact on political leaders throughout the modern West.

Although the work advises princes how to tyrannize, Machiavelli is generally thought to have preferred some form of free republic. - Anti-Machiavel

-

A 1740 essay by Frederick the Great consisting of a chapter-by-chapter rebuttal of The Prince, the 16th-century book by Niccolò Machiavelli, and Machiavellianism in general.

Frederick’s argument is essentially moral in nature. His own views reflect a largely Enlightenment ideal of rational and benevolent statesmanship: the king, Frederick contends, is charged with maintaining the health and prosperity of his subjects. - enlightened absolutism

-

Also known as enlightened

despotism or benevolent absolutism, a form of absolute monarchy or

despotism inspired by the Enlightenment. The monarchs who embraced it

followed the participles of rationality. Some of them fostered education and allowed religious tolerance, freedom of speech, and the right to hold private

property. They held that royal power emanated not from divine right but from a

social contract whereby a despot was entrusted with the power to govern in lieu of any other governments.

Frederick the Great: Early Childhood

Frederick, the son of Frederick William I and his wife, Sophia Dorothea of Hanover, was born in Berlin in 1712. His birth was particularly welcomed by his grandfather, Frederick I, as his two previous grandsons both died in infancy. With the death of Frederick I in 1713, Frederick William became King of Prussia, thus making young Frederick the crown prince.

The new king wished for his sons and daughters to be educated not as royalty but as simple folk. He had been educated by a Frenchwoman, Madame de Montbail, who later became Madame de Rocoulle, and wanted her to educate his children. Frederick was brought up by Huguenot governesses and tutors and learned French and German simultaneously. In spite of his father’s desire that his education be entirely religious and pragmatic, the young Frederick, with the help of his tutor Jacques Duhan, secretly procured a 3,000-volume library of poetry, Greek and Roman classics, and French philosophy to supplement his official lessons.

Frederick William I, popularly dubbed the Soldier-King, possessed a violent temper and ruled Brandenburg-Prussia with absolute authority. As Frederick grew, his preference for music, literature, and French culture clashed with his father’s militarism, resulting in frequent beatings and humiliation from his father.

Crown Prince

Frederick found an ally in his sister Wilhelmine, with whom he remained close for life. At age 16, he formed an attachment to the king’s 13-year-old page, Peter Karl Christoph Keith. Margaret Goldsmith, a biographer of Frederick’s, suggests the attachment was of a sexual nature. As a result, Keith was sent away to an unpopular regiment near the Dutch frontier, while Frederick was temporarily sent to his father’s hunting lodge in order “to repent of his sin.” Around the same time, he became close friends with Hans Hermann von Katte.

When he was 18, Frederick plotted to flee to England with Katte and other junior army officers. Frederick and Katte were subsequently arrested and imprisoned in Küstrin. Because they were army officers who had tried to flee Prussia for Great Britain, Frederick William leveled an accusation of treason against the pair. The king briefly threatened the crown prince with the death penalty, then considered forcing Frederick to renounce the succession in favor of his brother, Augustus William, although either option would have been difficult to justify to the Imperial Diet (general assembly) of the Holy Roman Empire. The king forced Frederick to watch the decapitation of Katte at Küstrin, leaving the crown prince to faint right before the fatal blow was struck.

Frederick was granted a royal pardon and released from his cell, although he remained stripped of his military rank. Instead of returning to Berlin, he was forced to remain in Küstrin and began rigorous schooling in statecraft and administration. Tensions eased slightly when Frederick William visited Küstrin a year later and Frederick was allowed to visit Berlin on the occasion of his sister Wilhelmine’s marriage to Margrave Frederick of Bayreuth in 1731. The crown prince returned to Berlin after finally being released from his tutelage at Küstrin a year later.

A number of royal family members were considered candidates for marriage, but Frederick eventually married Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Bevern, a Protestant relative of the Austrian Habsburgs, in 1733. He had little in common with his bride and resented the political marriage as an example of the Austrian interference that had plagued Prussia since 1701. Once Frederick secured the throne in 1740 after his father’s death,

he immediately separated from his wife and prevented Elisabeth from visiting his court in Potsdam, granting her instead Schönhausen Palace and apartments at the Berliner Stadtschloss.

In later years, Frederick would pay his wife formal visits only once a year.

Recent major biographers are unequivocal that Frederick was homosexual and that his sexuality was central to his life and character.

Frederick as Crown Prince by Antoine Pesne, 1739.

Frederick would come to the throne with an exceptional inheritance: an army of 80,000 men. By 1770, after two decades of punishing war alternating with intervals of peace, Frederick doubled the size of the huge army, which during his reign would consume 86% of the state budget.

Becoming the Leader

Frederick was restored to the Prussian Army as colonel. When Prussia provided a contingent of troops to aid Austria during the War of the Polish Succession, Frederick studied under Prince Eugene of Savoy during the campaign against France on the Rhine. Frederick William, weakened by gout brought about by the campaign and seeking to reconcile with his heir, granted Frederick Schloss Rheinsberg in Rheinsberg, north of Neuruppin. In Rheinsberg, Frederick assembled a small number of musicians, actors, and other artists. He spent his time reading, watching dramatic plays, and making and listening to music, and regarded this time as one of the happiest of his life.

The works of Niccolò Machiavelli, such as The Prince, were considered a guideline for the behavior of a king in Frederick’s age. In 1739, Frederick finished his Anti-Machiavel, an idealistic refutation of Machiavelli. Instead of promoting more democratic principles of the Enlightenment, Frederick was a proponent of enlightened absolutism. It was written in French and published anonymously in 1740, but Voltaire distributed it in Amsterdam to great popularity.

Frederick’s years dedicated to the arts instead of politics ended upon the 1740 death of Frederick William and his inheritance of the Kingdom of Prussia.

Prince Frederick was 28 years old when he acceded to the throne of Prussia.

His goal was to modernize and unite his vulnerably disconnected lands, and he largely succeeded through aggressive military and foreign policies. Contrary to his father’s fears, Frederick proved himself a courageous soldier and an extremely skillful strategist. In fact, Napoleon Bonaparte viewed the Prussian king as the greatest tactical genius of all time. After the Seven Years’ War, the Prussian military acquired a formidable reputation across Europe. Esteemed for their efficiency and success in battle, Frederick’s army became a model emulated by other European powers, most notably Russia and France. Frederick was also an influential military theorist whose analysis emerged from his extensive personal battlefield experience and covered issues of strategy, tactics, mobility and logistics. Even the later military reputation of Prussia under Bismarck and Moltke rested on the weight of mid-eighteenth century military developments and the territorial expansion of Frederick the Great. Despite his dazzling success as a military commander, however, Frederick was not a fan of protracted warfare.

21.2.3: Prussia Under Frederick the Great

Frederick the Great significantly modernized Prussian economy, administration, judicial system, education, finance, and agriculture, but never attempted to change the social order based on the dominance of the landed nobility.

Learning Objective

Analyze Frederick the Great’s domestic reforms and his relationship with the Junker class

Key Points

-

Frederick the Great helped transform

Prussia from a European backwater to an economically strong and politically

reformed state. During his reign, the effects of the Seven Years’ War and the

gaining of Silesia greatly changed the economy. -

Frederick organized a

system of indirect taxation, which provided the state with more revenue than

direct taxation. He also followed Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky’s recommendations in the field

of toll levies and import restrictions and protected Prussian industries

with high tariffs and minimal restrictions on domestic trade. -

Frederick gave his state a modern

bureaucracy, reformed the judicial

system, and made it possible for men not of noble stock to become judges and

senior bureaucrats. He also allowed freedom of speech, the press, and

literature, and abolished most uses of judicial torture. He also reformed the currency system and thus stabilized prices. However, he did not reform the existing social order. -

At the time, Prussia’s education system was seen

as one of the best in Europe. Frederick laid the basic foundations of what

would eventually became a Prussian primary education system. In 1763, he issued

a decree for the first Prussian general school law based on the

principles developed by Johann Julius Hecker. -

Frederick was keenly interested in land use, especially

draining swamps and opening new farmland for colonizers who would increase the

kingdom’s food supply. The resulting program created

60,000 hectares (150,000 acres) of new

farmland, but also eliminated vast swaths of natural habitat. -

While Frederick was largely non-practicing and tolerated all faiths in his

realm, Protestantism became the favored religion and Catholics were not chosen

for higher state positions. His attitudes towards Catholics and Jews were very selective and thus in some cases oppressive, while in others relatively tolerant.

Key Terms

- Freemason

-

A member of fraternal organizations that trace their origins to the local fraternities of stonemasons, which from the end of the 14th century regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interactions with authorities and clients. There is no clear mechanism by which these local trade organizations became the fraternal organizations gathering members of similar ideological and intellectual interests, but the rituals and passwords known from operative lodges around the turn of the 17th–18th centuries show continuity with the rituals developed in the later 18th century by members who did not practice the physical craft.

- Seven Years’ War

-

A world war fought between 1754 and 1763, the main conflict occurring in the seven-year period from 1756 to 1763. It involved every European great power of the time except the Ottoman Empire, spanning five continents, and affected Europe, the Americas, West Africa, India, and the Philippines. The conflict split Europe into two coalitions, led by Great Britain on one side and France on the other. For the first time, aiming to curtail Britain and Prussia’s ever-growing might, France formed a grand coalition of its own, which ended with failure as Britain rose as the world’s predominant power, altering the European balance of power.

- Junkers

-

The members of the landed nobility in Prussia. They owned great estates that were maintained and worked by peasants with few rights. They were an important factor in Prussian and, after 1871, German military, political, and diplomatic leadership.

Frederick the Great and the Modernization of Prussia