2.1: The First Urban Civilizations

2.1.1: The Sumerians

The Sumerian people lived in Mesopotamia from the 27th-20th century BCE. They were inventive and industrious, creating large city-states, trading goods, mass-producing pottery, and perfecting many forms of technology.

Learning Objective

To understand the history and accomplishments of the Sumerian people

Key Points

- The Sumerians were a people living in Mesopotamia from the 27th-20th century BCE.

- The major periods in Sumerian history were the Ubaid period (6500-4100 BCE), the Uruk period (4100-2900 BCE), the Early Dynastic period (2900-2334 BCE), the Akkadian Empire period (2334 – 2218 BCE), the Gutian period (2218-2047 BCE), Sumerian Renaissance/Third Dynasty of Ur (2047-1940 BCE), and then decline.

- Many Sumerian clay tablets have been found with writing. Initially, pictograms were used, followed by cuneiform and then ideograms.

- Sumerians believed in anthropomorphic polytheism, or of many gods in human form that were specific to each city-state.

- Sumerians invented or perfected many forms of technology, including the wheel, mathematics, and cuneiform script.

Key Terms

- City-states

-

A city that with its surrounding territory forms an independent state.

- cuneiform script

-

Wedge-shaped characters used in the ancient writing systems of Mesopotamia, surviving mainly on clay tablets.

- ideograms

-

Written characters symbolizing an idea or entity without indicating the sounds used to say it.

- pictograms

-

A pictorial symbol for a word or phrase. They are the earliest known forms of writing.

- pantheon

-

The collective gods of a people or religion.

- Epic of Gilgamesh

-

An epic poem from the Third Dynasty of Ur (circa 2100 BCE), which is seen as the earliest surviving great work of literature.

- anthropomorphic

-

Having human characteristics.

“Sumerian” is the name given by the Semitic-speaking Akkadians to non-Semitic speaking people living in Mespotamia. City-states in the region, which were organized by canals and boundary stones and dedicated to a patron god or goddess, first rose to power during the prehistoric Ubaid and Uruk periods. Sumerian written history began in the 27th century BCE, but the first intelligible writing began in the 23rd century BCE. Classical Sumer ends with the rise of the Akkadian Empire in the 23rd century BCE, and only enjoys a brief renaissance in the 21st century BCE. The Sumerians were eventually absorbed into the Akkadian/Babylonian population.

Periods in Sumerian History

The Ubaid period (6500-4100 BCE) saw the first settlement in southern Mesopotamia by farmers who brought irrigation agriculture. Distinctive, finely painted pottery was evident during this time.

The Uruk period (4100-2900 BCE) saw several transitions. First, pottery began to be mass-produced. Second, trade goods began to flow down waterways in southern Mespotamia, and large, temple-centered cities (most likely theocratic and run by priests-kings) rose up to facilitate this trade. Slave labor was also utilized.

The Early Dynastic period (2900-2334 BCE) saw writing, in contrast to pictograms, become commonplace and decipherable. The Epic of Gilgamesh mentions several leaders, including Gilgamesh himself, who were likely historical kings. The first dynastic king was Etana, the 13th king of the first dynasty of Kish. War was on the increase, and cities erected walls for self-preservation. Sumerian culture began to spread from southern Mesopotamia into surrounding areas.

Sumerian Necklaces and Headgear

Sumerian necklaces and headgear discovered in the royal (and individual) graves, showing the way they may have been worn.

During the Akkadian Empire period (2334-2218 BCE), many in the region became bilingual in both Sumerian and Akkadian. Toward the end of the empire, though, Sumerian became increasingly a literary language.

The Gutian period (2218-2047 BCE) was marked by a period of chaos and decline, as Guti barbarians defeated the Akkadian military but were unable to support the civilizations in place.

The Sumerian Renaissance/Third Dynasty of Ur (2047-1940 BCE) saw the rulers Ur-Nammu and Shulgi, whose power extended into southern Assyria. However, the region was becoming more Semitic, and the Sumerian language became a religious language.

The Sumerian Renaissance ended with invasion by the Amorites, whose dynasty of Isin continued until 1700 BCE, at which point Mespotamia came under Babylonian rule.

Language and Writing

Many Sumerian clay tablets written in cuneiform script have been discovered. They are not the oldest example of writing, but nevertheless represent a great advance in the human ability to write down history and create literature. Initially, pictograms were used, followed by cuneiform, and then ideograms. Letters, receipts, hymns, prayers, and stories have all been found on clay tablets.

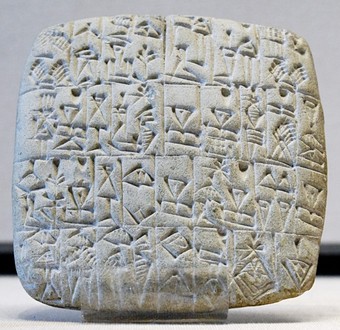

Bill of Sale on a Clay Tablet

This clay tablet shows a bill of sale for a male slave and building, circa 2600 BCE.

Religion

Sumerians believed in anthropomorphic polytheism, or of many gods in human form, which were specific to each city-state. The core pantheon consisted of An (heaven), Enki (a healer and friend to humans), Enlil (gave spells spirits must obey), Inanna (love and war), Utu (sun-god), and Sin (moon-god).

Technology

Sumerians invented or improved a wide range of technology, including the wheel, cuneiform script, arithmetic, geometry, irrigation, saws and other tools, sandals, chariots, harpoons, and beer.

2.1.2: The Assyrians

The Assyrians were a major Semitic empire of the Ancient Near East, who existed as an independent state for approximately nineteen centuries between c. 2500-605 BCE, enjoying widespread military success in its heyday.

Learning Objective

Describe key characteristics and notable events of the Assyrian Empire

Key Points

- Centered on the Upper Tigris river in northern Mesopotamia, the Assyrians came to rule powerful empires at several times, the last of which grew to be the largest and most powerful empire the world had yet seen.

- At its peak, the Assyrian empire stretched from Cyprus in the Mediterranean Sea to Persia, and from the Caucasus Mountains (Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan) to the Arabian Peninsula and Egypt. It was at the height of technological, scientific, and cultural achievements for its time.

- In the Old Assyrian period, Assyria established colonies in Asia Minor and the Levant, and asserted itself over southern Mesopotamia under king Ilushuma.

- Assyria experienced fluctuating fortunes in the Middle Assyrian period, with some of its kings finding themselves under the influence of foreign rulers while others eclipsed neighboring empires.

- Assyria became a great military power during the Neo-Assyrian period, and saw the conquests of large empires, such as Egyptians, the Phoenicians, the Hittites, and the Persians, among others.

- After its fall in the late 600s BCE, Assyria remained a province and geo-political entity under various empires until the mid-7th century CE.

Key Terms

- Aššur

-

The original capital of the Assyrian Empire, which dates back to 2600 BCE.

- Assyrian Empire

-

A major Semitic kingdom of the Ancient Near East, which existed as an independent state for a period of approximately nineteen centuries from c. 2500-605 BCE.

The Assyrian Empire was a major Semitic kingdom, and often empire, of the Ancient Near East. It existed as an independent state for a period of approximately 19 centuries from c. 2500 BCE to 605 BCE, which spans the Early Bronze Age through to the late Iron Age. For a further 13 centuries, from the end of the 7th century BCE to the mid-7th century CE, it survived as a geo-political entity ruled, for the most part, by foreign powers (although a number of small Neo-Assyrian states arose at different times throughout this period).

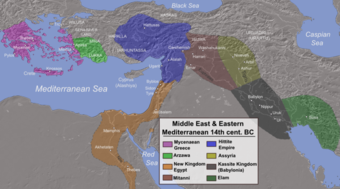

Map of the Ancient Near East during the 14th century BCE, showing the great powers of the day

This map shows the extent of the empires of Egypt (orange), Hatti (blue), the Kassite kingdom of Babylon (black), Assyria (yellow), and Mitanni (brown). The extent of the Achaean/Mycenaean civilization is shown in purple.

Centered on the Upper Tigris river, in northern Mesopotamia (northern Iraq, northeast Syria, and southeastern Turkey), the Assyrians came to rule powerful empires at several times, the last of which grew to be the largest and most powerful empire the world had yet seen.

As a substantial part of the greater Mesopotamian “Cradle of Civilization,” Assyria was at the height of technological, scientific, and cultural achievements for its time. At its peak, the Assyrian empire stretched from Cyprus in the Mediterranean Sea to Persia (Iran), and from the Caucasus Mountains (Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan) to the Arabian Peninsula and Egypt. Assyria is named for its original capital, the ancient city of Ašur (a.k.a., Ashur) which dates to c. 2600 BCE and was located in what is now the Saladin Province of northern Iraq. Ashur was originally one of a number of Akkadian city states in Mesopotamia. In the late 24th century BCE, Assyrian kings were regional leaders under Sargon of Akkad, who united all the Akkadian Semites and Sumerian-speaking peoples of Mesopotamia under the Akkadian Empire (c. 2334 BC-2154 BCE). Following the fall of the Akkadian Empire, c. 2154 BCE, and the short-lived succeeding Sumerian Third Dynasty of Ur, which ruled southern Assyria, Assyria regained full independence.

The history of Assyria proper is roughly divided into three periods, known as Old Assyrian (late 21st-18th century BCE), Middle Assyrian (1365-1056 BCE), and Neo-Assyrian (911- 612BCE). These periods roughly correspond to the Middle Bronze Age, Late Bronze Age, and Early Iron Age, respectively. In the Old Assyrian period, Assyria established colonies in Asia Minor and the Levant. Under king Ilushuma, it asserted itself over southern Mesopotamia. From the late 19th century BCE, Assyria came into conflict with the newly created state of Babylonia, which eventually eclipsed the older Sumero-Akkadian states in the south, such as Ur, Isin, Larsa and Kish. Assyria experienced fluctuating fortunes in the Middle Assyrian period. Assyria had a period of empire under Shamshi-Adad I and Ishme-Dagan in the 19th and 18th centuries BCE. Following the reigns of these two kings, it found itself under Babylonian and Mitanni-Hurrian domination for short periods in the 18th and 15th centuries BCE, respectively.

However, a shift in the Assyrian’s dominance occurred with the rise of the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365 BCE-1056 BCE). This period saw the reigns of great kings, such as Ashur-uballit I, Arik-den-ili, Tukulti-Ninurta I, and Tiglath-Pileser I. Additionally, during this period, Assyria overthrew Mitanni and eclipsed both the Hittite Empire and Egyptian Empire in the Near East. Long wars helped build Assyria into a warrior society, supported by landed nobility, which supplied horses to the military. All free male citizens were required to serve in the military, and women had very low status.

Beginning with the campaigns of Adad-nirari II from 911 BCE, Assyria again showed itself to be a great power over the next three centuries during the Neo-Assyrian period. It overthrew the Twenty-Fifth dynasty of Egypt, and conquered a number of other notable civilizations, including Babylonia, Elam, Media, Persia, Phoenicia/Canaan, Aramea (Syria), Arabia, Israel, and the Neo-Hittites. They drove the Ethiopians and Nubians from Egypt, defeated the Cimmerians and Scythians, and exacted tribute from Phrygia, Magan, and Punt, among others.

After its fall (between 612-605 BCE), Assyria remained a province and geo-political entity under the Babylonian, Median, Achaemenid, Seleucid, Parthian, Roman, and Sassanid Empires, until the Arab Islamic invasion and conquest of Mesopotamia in the mid-7th century CE when it was finally dissolved.

Assyria is mainly remembered for its military victories, technological advancements (such as using iron for weapons and building roads), use of torture to inspire fear, and a written history of conquests. Its military had not only general troops, but charioteers, cavalry, bowmen, and lancers.

2.2: Akkadian Empire

2.2.1: River Valley Civilizations

The first civilizations formed in river valleys, and were characterized by a caste system and a strong government that controlled water access and resources.

Learning Objective

Explain why early civilizations arose on the banks of rivers

Key Points

- Rivers were attractive locations for the first civilizations because they provided a steady supply of drinking water and game, made the land fertile for growing crops, and allowed for easy transportation.

- Early river civilizations were all hydraulic empires that maintained power and control through exclusive control over access to water. This system of government arose through the need for flood control and irrigation, which requires central coordination and a specialized bureaucracy.

- Hydraulic hierarchies gave rise to the established permanent institution of impersonal government, since changes in ruling were usually in personnel, but not in the structure of government.

Key Terms

- Fertile Crescent

-

A crescent-shaped region containing the comparatively moist and fertile land of otherwise arid and semi-arid Western Asia, and the Nile Valley and Nile Delta of northeast Africa. Often called the cradle of civilization.

- hydraulic empire

-

A social or governmental structure that maintains power through exclusive control of water access.

- caste

-

A form of social stratification characterized by endogamy (hereditary transmission of a lifestyle). This lifestyle often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultural notions of purity and pollution.

- Water crisis

-

There is not enough fresh, clean water to meet local demand.

- Water shortage

-

Water is less available due to climate change, pollution, or overuse.

- Neolithic Revolution

-

Also called the Agricultural Revolution, this was the wide-scale transition of human cultures from being hunter-gatherers to being settled agriculturalists.

- Water stress

-

Difficulty in finding fresh water, or the depletion of available water sources.

The First Civilizations

The first civilizations formed on the banks of rivers. The most notable examples are the Ancient Egyptians, who were based on the Nile, the Mesopotamians in the Fertile Crescent on the Tigris/Euphrates rivers, the Ancient Chinese on the Yellow River, and the Ancient India on the Indus. These early civilizations began to form around the time of the Neolithic Revolution (12000 BCE).

Rivers were attractive locations for the first civilizations because they provided a steady supply of drinking water and made the land fertile for growing crops. Moreover, goods and people could be transported easily, and the people in these civilizations could fish and hunt the animals that came to drink water. Additionally, those lost in the wilderness could return to civilization by traveling downstream, where the major centers of human population tend to concentrate.

The Nile River and Delta

Most of the Ancient Egyptian settlements occurred along the northern part of the Nile, pictured in this satellite image taken from orbit by NASA.

Hydraulic Empires

Though each civilization was uniquely different, we can see common patterns amongst these first civilizations since they were all based around rivers. Most notably, these early civilizations were all hydraulic empires. A hydraulic empire (also known as hydraulic despotism, or water monopoly empire) is a social or governmental structure which maintains power through exclusive control over water access. This system of government arises through the need for flood control and irrigation, which requires central coordination and a specialized bureaucracy. This political structure is commonly characterized by a system of hierarchy and control based around class or caste. Power, both over resources (food, water, energy) and a means of enforcement, such as the military, are vital for the maintenance of control. Most hydraulic empires exist in desert regions, but imperial China also had some such characteristics, due to the exacting needs of rice cultivation. The only hydraulic empire to exist in Africa was under the Ajuran State near the Jubba and Shebelle Rivers in the 15th century CE.

Karl August Wittfogel, the German scholar who first developed the notion of the hydraulic empire, argued in his book, Oriental Despotism (1957), that strong government control characterized these civilizations because a particular resource (in this case, river water) was both a central part of economic processes and environmentally limited. This fact made controlling supply and demand easier and allowed the establishment of a more complete monopoly, and also prevented the use of alternative resources to compensate. However, it is also important to note that complex irrigation projects predated states in Madagascar, Mexico, China and Mesopotamia, and thus it cannot be said that a key, limited economic resource necessarily mandates a strong centralized bureaucracy.

According to Wittfogel, the typical hydraulic empire government has no trace of an independent aristocracy—

in contrast to the decentralized feudalism of medieval Europe. Though tribal societies had structures that were usually personal in nature, exercised by a patriarch over a tribal group related by various degrees of kinship, hydraulic hierarchies gave rise to the established permanent institution of impersonal government. Popular revolution in such a state was very difficult; a dynasty might die out or be overthrown by force, but the new regime would differ very little from the old one. Hydraulic empires were usually destroyed by foreign conquerors.

Water Scarcity Today

Access to water is still crucial to modern civilizations; water scarcity affects more than 2.8 billion people globally. Water stress is the term used to describe difficulty in finding fresh water or the depletion of available water sources. Water shortage is the term used when water is less available due to climate change, pollution, or overuse. Water crisis is the term used when there is not enough fresh, clean water to meet local demand. Water scarcity may be physical, meaning there are inadequate water resources available in a region, or economic, meaning governments are not managing available resources properly. The United Nations Development Programme has found that water scarcity generally results from the latter issue.

2.2.2: The Akkadian Empire

The Akkadian Empire flourished in the 24th and 22nd centuries BCE, ruled by Sargon and Naram-Sin. It eventually collapsed in 2154 BCE, due to the invasion of barbarian peoples and large-scale climatic changes.

Learning Objective

Describe the key political characteristics of the Akkadian Empire

Key Points

- The Akkadian Empire was an ancient Semitic empire centered in the city of Akkad and its surrounding region in ancient Mesopotamia, which united all the indigenous Akkadian speaking Semites and the Sumerian speakers under one rule within a multilingual empire.

- King Sargon, the founder of the empire, conquered several regions in Mesopotamia and consolidated his power by instating Akaddian officials in new territories. He extended trade across Mesopotamia and strengthened the economy through rain-fed agriculture in northern Mesopotamia.

- The Akkadian Empire experienced a period of successful conquest under Naram-Sin due to benign climatic conditions, huge agricultural surpluses, and the confiscation of wealth.

- The empire collapsed after the invasion of the Gutians. Changing climatic conditions also contributed to internal rivalries and fragmentation, and the empire eventually split into the Assyrian Empire in the north and the Babylonian empire in the south.

Key Terms

- Gutians

-

A group of barbarians from the Zagros Mountains who invaded the Akkadian Empire and contributed to its collapse.

- Sargon

-

The first king of the Akkadians. He conquered many of the surrounding regions to establish the massive multilingual empire.

- Akkadian Empire

-

An ancient Semitic empire centered in the city of Akkad and its surrounding region in ancient Mesopotamia.

- Cuneiform

-

One of the earliest known systems of writing, distinguished by its wedge-shaped marks on clay tablets, and made by means of a blunt reed for a stylus.

- Semites

-

Today, the word “Semite” may be used to refer to any member of any of a number of peoples of ancient Southwest Asian descent, including the Akkadians, Phoenicians, Hebrews (Jews), Arabs, and their descendants.

- Naram-Sin

-

An Akkadian king who conquered Ebla, Armum, and Magan, and built a royal residence at Tell Brak.

The Akkadian Empire was an ancient Semitic empire centered in the city of Akkad, which united all the indigenous Akkadian speaking Semites and Sumerian speakers under one rule. The Empire controlled Mesopotamia, the Levant, and parts of Iran.

Map of the Akkadian Empire

The Akkadian Empire is pictured in brown. The directions of the military campaigns are shown as yellow arrows.

Its founder was Sargon of Akkad (2334–2279 BCE). Under Sargon and his successors, the Akkadian Empire reached its political peak between the 24th and 22nd centuries BCE. Akkad is sometimes regarded as the first empire in history.

Sargon and His Dynasty

Sargon claimed to be the son of La’ibum or Itti-Bel, a humble gardener, and possibly a hierodule, or priestess to Ishtar or Inanna. Some later claimed that his mother was an “entu” priestess (high priestess). Originally a cupbearer to king Ur-Zababa of Kish, Sargon became a gardener, which gave him access to a disciplined corps of workers who also may have served as his first soldiers. Displacing Ur-Zababa, Sargon was crowned king and began a career of foreign conquest. He invaded Syria and Canaan on four different campaigns, and spent three years subduing the countries of “the west” to unite them with Mesopotamia “into a single empire.”

Sargon’s empire reached westward as far as the Mediterranean Sea and perhaps Cyprus (Kaptara); northward as far as the mountains; eastward over Elam; and as far south as Magan (Oman)—a region over which he purportedly reigned for 56 years, though only four “year-names” survive. He replaced rulers with noble citizens of Akkad. Trade extended from the silver mines of Anatolia to the lapis lazuli mines in Afghanistan, and from the cedars of Lebanon to the copper of Magan. The empire’s breadbasket was the rain-fed agricultural system of northern Mesopotamia (Assyria), and a chain of fortresses was built to control the imperial wheat production.

Sargon, throughout his long life, showed special deference to the Sumerian deities, particularly Inanna (Ishtar), his patroness, and Zababa, the warrior god of Kish. He called himself “the anointed priest of Anu” and “the great ensi of Enlil. ”

Sargon managed to crush his opposition even in old age. Difficulties also broke out in the reign of his sons, Rimush (2278–2270 BCE), who was assassinated by his own courtiers, and Manishtushu (2269–2255 BCE), who reigned for 15 years. He, too, was likely assassinated in a palace conspiracy.

Bronze head of a king

Bronze head of a king, most likely Sargon of Akkad but possibly Naram-Sin. Unearthed in Nineveh (now in Iraq).

Naram-Sin

Manishtushu’s son and successor, Naram-Sin (called, Beloved of Sin) (2254–2218 BCE), assumed the imperial title “King Naram-Sin, King of the Four Quarters.” He was also, for the first time in Sumerian culture, addressed as “the god of Agade (Akkad).” This represents a marked shift away from the previous religious belief that kings were only representatives of the people toward the gods.

Naram-Sin conquered Ebla and Armum, and built a royal residence at Tell Brak, a crossroads at the heart of the Khabur River basin of the Jezirah. Naram-Sin also conquered Magan and created garrisons to protect the main roads. This productive period of Akkadian conquest may have been based upon benign climatic conditions, huge agricultural surpluses, and the confiscation of the wealth of other peoples.

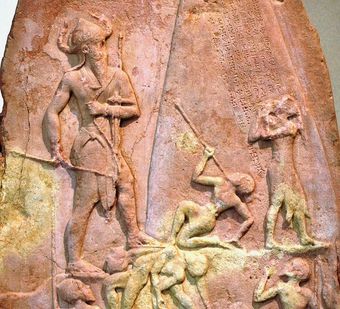

Stele of Naram-Sin

This stele commemorates Naram-Sin’s victory against the Lullubi from Zagros in 2260 BCE. Naram-Sin is depicted to be wearing a horned helmet, a symbol of divinity, and is also portrayed in a larger scale in comparison to others to emphasize his superiority.

Living in the Akkadian Empire

Future Mesopotamian states compared themselves to the Akkadian Empire, which they saw as a classical standard in governance. The economy was dependent on irrigated farmlands of southern Iraq, and rain-fed agriculture of Northern Iraq. There was often a surplus of agriculture but shortages of other goods, like metal ore, timber, and building stone. Art of the period often focused on kings, and depicted somber and grim conflict and subjugation to divinities. Sumerians and Akkadians were bilingual in each other’s languages, but Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian. The empire had a postal service, and a library featuring astronomical observations.

Collapse of the Akkadian Empire

The Empire of Akkad collapsed in 2154 BCE, within 180 years of its founding. The collapse ushered in a Dark Age period of regional decline that lasted until the rise of the Third Dynasty of Ur in 2112 BCE. By the end of the reign of Naram-Sin’s son, Shar-kali-sharri (2217-2193 BCE), the empire had weakened significantly. There was a period of anarchy between 2192 BC and 2168 BCE. Some centralized authority may have been restored under Shu-Durul (2168-2154 BCE), but he was unable to prevent the empire collapsing outright from the invasion of barbarian peoples, known as the Gutians, from the Zagros Mountains.

Little is known about the Gutian period or for how long it lasted. Cuneiform sources suggest that the Gutians’ administration showed little concern for maintaining agriculture, written records, or public safety; they reputedly released all farm animals to roam about Mesopotamia freely, and soon brought about famine and rocketing grain prices. The Sumerian king Ur-Nammu (2112-2095 BCE) later cleared the Gutians from Mesopotamia during his reign.

The collapse of rain-fed agriculture in the Upper Country due to drought meant the loss of the agrarian subsidies which had kept the Akkadian Empire solvent in southern Mesopotamia. Rivalries between pastoralists and farmers increased. Attempts to control access to water led to increased political instability; meanwhile, severe depopulation occurred.

After the fall of the Akkadian Empire, the Akkadian people coalesced into two major Akkadian speaking nations: Assyria in the north, and, a few centuries later, Babylonia in the south.

2.2.3: Ur

The city-state of Ur in Mesopotamia was important and wealthy, and featured highly centralized bureaucracy. It is famous for the Ziggurat of Ur, a temple whose ruins were discovered in modern day.

Learning Objective

To understand the significance of the city-state of Ur

Key Points

- Ur was a major Sumerian city-state located in Mesopotamia, founded circa 3800 BCE.

- Cuneiform tablets show that Ur was a highly centralized, wealthy, bureaucratic state during the third millennium BCE.

- The Ziggurat of Ur was built in the 21st century BCE, during the reign of Ur-Nammu, and was reconstructed in the 6th century BCE by Nabonidus, the last king of Babylon.

- Control of Ur passed among various peoples until the Third Dynasty of Ur, which featured the strong kings Ur-Nammu and Shulgi.

- Ur was uninhabited by 500 BCE.

Key Terms

- Sargon the Great

-

A Semitic emperor of the Akkadian Empire, known for conquering Sumerian city-states in the 24th and 23rd centuries BCE.

- Ziggurat

-

A rectangular stepped tower, sometimes surmounted by a temple.

- Sumerian

-

A group of non-Semitic people living in ancient Mesopotamia.

- Cuneiform

-

Wedge-shaped characters imprinted onto clay tablets, used in ancient writing systems of Mesopotamia.

A Major Mesopotamian City

Ur was a major Sumerian city-state located in Mesopotamia, marked today by Tell el-Muqayyar in southern Iraq. It was founded circa 3800 BCE, and was recorded in written history from the 26th century BCE. Its patron god was Nanna, the moon god, and the city’s name literally means “the abode of Nanna.”

Cuneiform tablets show that Ur was, during the third millennium BCE, a highly centralized, wealthy, bureaucratic state. The discovery of the Royal Tombs, dating from about the 25th century BCE, showed that the area had luxury items made out of precious metals and semi-precious stones, which would have required importation. Some estimate that Ur was the largest city in the world from 2030-1980 BCE, with approximately 65,000 people.

The City of Ur

This map shows Mesopotamia in the third millennium BCE, with Ur in the south.

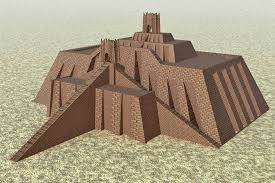

The Ziggurat of Ur

This temple was built in the 21st century BCE, during the reign of Ur-Nammu, and was reconstructed in the 6th century BCE by Nabonidus, the last king of Babylon. The ruins, which cover an area of 3,900 feet by 2,600 feet, were uncovered in the 1930s. It was part of a temple complex that served as an administrative center for the city of Ur, and was dedicated to Nanna, the moon god.

The Ziggurat of Ur

This is a reconstruction of Ur-Nammu’s ziggurat.

Control of Ur

Between the 24th and 22nd century BCE, Ur was controlled by Sargon the Great, of the Akkadian Empire. After the fall of this empire, Ur was ruled by the barbarian Gutians, until King Ur-Nammu came to power, circa 2047 – 2030 BCE (the Third Dynasty of Ur). Advances during this time included the building of temples, like the Ziggurat, better agricultural irrigation, and a code of laws, called the Code of Ur-Nammu, which preceded the Code of Hammurabi by 300 years.

Shulgi succeeded Ur-Nammu, and was able to increase Ur’s power by creating a highly centralized bureaucratic state. Shulgi, who eventually declared himself a god, ruled from 2029-1982 BCE, and was well-known for at least two thousand years after.

Three more kings, Amar-Sin, Shu0Sin and Ibbi-Sin, ruled Ur before it fell to the Elamites in 1940 BCE. Although Ur lost its political power, it remained economically important. It was ruled by the first dynasty of Babylonia, then part of the Sealand Dynasty, then by the Kassites before falling to the Assyrian Empire from the 10th-7th century BE. After the 7th century BCE, it was ruled by the Chaldean Dynasty of Babylon. It began its final decline around 550 BCE, and was uninhabited by 500 BE. The final decline was likely due to drought, changing river patterns and the silting of the Persian Gulf.

2.3: Babylonia

2.3.1: Babylon

Following the collapse of the Akkadians, the Babylonian Empire flourished under Hammurabi, who conquered many surrounding peoples and empires, in addition to developing an extensive code of law and establishing Babylon as a “holy city” of southern Mesopotamia.

Learning Objective

Describe key characteristics of the Babylonian Empire under Hammurabi

Key Points

- A series of conflicts between the Amorites and the Assyrians followed the collapse of the Akkadian Empire, out of which Babylon arose as a powerful city-state c. 1894 BCE.

- Babylon remained a minor territory for a century after it was founded, until the reign of its sixth Amorite ruler, Hammurabi (1792-1750 BCE), an extremely efficient ruler who established a bureaucracy with taxation and centralized government.

- Hammurabi also enjoyed various military successes over the whole of southern Mesopotamia, modern-day Iran and Syria, and the old Assyrian Empire in Asian Minor.

- After the death of Hammurabi, the First Babylonian Dynasty eventually fell due to attacks from outside its borders.

Key Terms

- Marduk

-

The south Mesopotamian god that rose to supremacy in the pantheon over the previous god, Enlil.

- Hammurabi

-

The sixth king of Babylon, who, under his rule, saw Babylonian advancements, both militarily and bureaucratically.

- Code of Hammurabi

-

A code of law that echoed and improved upon earlier written laws of Sumer, Akkad, and Assyria.

- Amorites

-

An ancient Semitic-speaking people from ancient Syria who also occupied large parts of Mesopotamia in the 21st Century BCE.

The Rise of the First Babylonian Dynasty

Following the disintegration of the Akkadian Empire, the Sumerians rose up with the Third Dynasty of Ur in the late 22nd century BCE, and ejected the barbarian Gutians from southern Mesopotamia. The Sumerian “Ur-III” dynasty eventually collapsed at the hands of the Elamites, another Semitic people, in 2002 BCE. Conflicts between the Amorites (Western Semitic nomads) and the Assyrians continued until Sargon I (1920-1881 BCE) succeeded as king in Assyria and withdrew Assyria from the region, leaving the Amorites in control (the Amorite period).

One of these Amorite dynasties founded the city-state of Babylon circa 1894 BCE, which would ultimately take over the others and form the short-lived first Babylonian empire, also called the Old Babylonian Period.

A chieftain named Sumuabum appropriated the then relatively small city of Babylon from the neighboring Mesopotamian city state of Kazallu, turning it into a state in its own right. Sumuabum appears never to have been given the title of King, however.

The Babylonians Under Hammurabi

Babylon remained a minor territory for a century after it was founded, until the reign of its sixth Amorite ruler, Hammurabi (1792-1750 BCE). He was an efficient ruler, establishing a centralized bureaucracy with taxation. Hammurabi freed Babylon from Elamite dominance, and then conquered the whole of southern Mesopotamia, bringing stability and the name of Babylonia to the region.

The armies of Babylonia under Hammurabi were well-disciplined, and he was able to invade modern-day Iran to the east and conquer the pre-Iranic Elamites, Gutians and Kassites. To the west, Hammurabi enjoyed military success against the Semitic states of the Levant (modern Syria), including the powerful kingdom of Mari. Hammurabi also entered into a protracted war with the Old Assyrian Empire for control of Mesopotamia and the Near East. Assyria had extended control over parts of Asia Minor from the 21st century BCE, and from the latter part of the 19th century BCE had asserted itself over northeast Syria and central Mesopotamia as well. After a protracted, unresolved struggle over decades with the Assyrian king Ishme-Dagan, Hammurabi forced his successor, Mut-Ashkur, to pay tribute to Babylon c. 1751 BCE, thus giving Babylonia control over Assyria’s centuries-old Hattian and Hurrian colonies in Asia Minor.

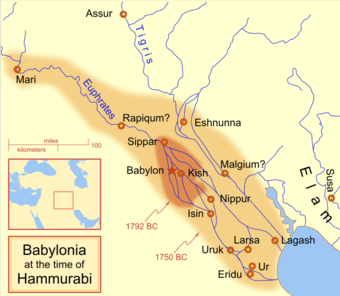

Babylonia under Hammurabi

The extent of the Babylonian Empire at the start and end of Hammurabi’s reign.

One of the most important works of this First Dynasty of Babylon was the compilation in about 1754 BCE of a code of laws, called the Code of Hammurabi, which echoed and improved upon the earlier written laws of Sumer, Akkad, and Assyria. It is one of the oldest deciphered writings of significant length in the world. The Code consists of 282 laws, with scaled punishments depending on social status, adjusting “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” Nearly one-half of the Code deals with matters of contract. A third of the code addresses issues concerning household and family relationships.

From before 3000 BC until the reign of Hammurabi, the major cultural and religious center of southern Mesopotamia had been the ancient city of Nippur, where the god Enlil reigned supreme. However, with the rise of Hammurabi, this honor was transferred to Babylon, and the god Marduk rose to supremacy (with the god Ashur remaining the dominant deity in Assyria). The city of Babylon became known as a “holy city,” where any legitimate ruler of southern Mesopotamia had to be crowned. Hammurabi turned what had previously been a minor administrative town into a major city, increasing its size and population dramatically, and conducting a number of impressive architectural works.

The Decline of the First Babylonian Dynasty

Despite Hammurabi’s various military successes, southern Mesopotamia had no natural, defensible boundaries, which made it vulnerable to attack. After the death of Hammurabi, his empire began to disintegrate rapidly. Under his successor Samsu-iluna (1749-1712 BCE), the far south of Mesopotamia was lost to a native Akkadian king, called Ilum-ma-ili, and became the Sealand Dynasty; it remained free of Babylon for the next 272 years.

Both the Babylonians and their Amorite rulers were driven from Assyria to the north by an Assyrian-Akkadian governor named Puzur-Sin, c. 1740 BCE. Amorite rule survived in a much-reduced Babylon, Samshu-iluna’s successor, Abi-Eshuh, made a vain attempt to recapture the Sealand Dynasty for Babylon, but met defeat at the hands of king Damqi-ilishu II. By the end of his reign, Babylonia had shrunk to the small and relatively weak nation it had been upon its foundation.

2.3.2: Hammurabi’s Code

The Code of Hammurabi was a collection of 282 laws, written in c. 1754 BCE in Babylon, which focused on contracts and family relationships, featuring a presumption of innocence and the presentation of evidence.

Learning Objective

Describe the significance of Hammurabi’s code

Key Points

- The Code of Hammurabi is one of the oldest deciphered writings of length in the world (written c. 1754 BCE), and features a code of law from ancient Babylon in Mesopotamia.

- The Code consisted of 282 laws, with punishments that varied based on social status (slaves, free men, and property owners).

- Some have seen the Code as an early form of constitutional government, as an early form of the presumption of innocence, and as the ability to present evidence in one’s case.

- Major laws covered in the Code include slander, trade, slavery, the duties of workers, theft, liability, and divorce. Nearly half of the code focused on contracts, and a third on household relationships.

- There were three social classes: the amelu (the elite), the mushkenu (free men) and ardu (slave).

- Women had limited rights, and were mostly based around marriage contracts and divorce rights.

- A stone stele featuring the Code was discovered in 1901, and is currently housed in the Louvre.

Key Terms

- cuneiform

-

Wedge-shaped characters used in the ancient writing systems of Mesopotamia, impressed on clay tablets.

- ardu

-

In Babylon, a slave.

- mushkenu

-

In Babylon, a free man who was probably landless.

- amelu

-

In Babylon, an elite social class of people.

- stele

-

A stone or wooden slab, generally taller than it is wide, erected as a monument.

The Code of Hammurabi is one of the oldest deciphered writings of length in the world, and features a code of law from ancient Babylon in Mesopotamia. Written in about 1754 BCE by the sixth king of Babylon, Hammurabi, the Code was written on stone stele and clay tablets. It consisted of 282 laws, with punishments that varied based on social status (slaves, free men, and property owners). It is most famous for the “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth” (lex talionis) form of punishment. Other forms of codes of law had been in existence in the region around this time, including the Code of Ur-Nammu, king of Ur (c. 2050 BCE), the Laws of Eshnunna (c. 1930 BCE) and the codex of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin (c. 1870 BCE).

The laws were arranged in groups, so that citizens could easily read what was required of them. Some have seen the Code as an early form of constitutional government, and as an early form of the presumption of innocence, and the ability to present evidence in one’s case. Intent was often recognized and affected punishment, with neglect severely punished. Some of the provisions may have been codification of Hammurabi’s decisions, for the purpose of self-glorification. Nevertheless, the Code was studied, copied, and used as a model for legal reasoning for at least 1500 years after.

The prologue of the Code features Hammurabi stating that he wants “to make justice visible in the land, to destroy the wicked person and the evil-doer, that the strong might not injure the weak.” Major laws covered in the Code include slander, trade, slavery, the duties of workers, theft, liability, and divorce. Nearly half of the code focused on contracts, such as wages to be paid, terms of transactions, and liability in case of property damage. A third of the code focused on household and family issues, including inheritance, divorce, paternity and sexual behavior. One section establishes that a judge who incorrectly decides an issue may be removed from his position permanently. A few sections address military service.

One of the most well-known sections of the Code was law #196: “If a man destroy the eye of another man, they shall destroy his eye. If one break a man’s bone, they shall break his bone. If one destroy the eye of a freeman or break the bone of a freeman he shall pay one gold mina. If one destroy the eye of a man’s slave or break a bone of a man’s slave he shall pay one-half his price.”

The Social Classes

Under Hammurabi’s reign, there were three social classes. The amelu was originally an elite person with full civil rights, whose birth, marriage and death were recorded. Although he had certain privileges, he also was liable for harsher punishment and higher fines. The king and his court, high officials, professionals and craftsmen belonged to this group. The mushkenu was a free man who may have been landless. He was required to accept monetary compensation, paid smaller fines and lived in a separate section of the city. The ardu was a slave whose master paid for his upkeep, but also took his compensation. Ardu could own property and other slaves, and could purchase his own freedom.

Women’s Rights

Women entered into marriage through a contract arranged by her family. She came with a dowry, and the gifts given by the groom to the bride also came with her. Divorce was up to the husband, but after divorce he then had to restore the dowry and provide her with an income, and any children came under the woman’s custody. However, if the woman was considered a “bad wife” she might be sent away, or made a slave in the husband’s house. If a wife brought action against her husband for cruelty and neglect, she could have a legal separation if the case was proved. Otherwise, she might be drowned as punishment. Adultery was punished with drowning of both parties, unless a husband was willing to pardon his wife.

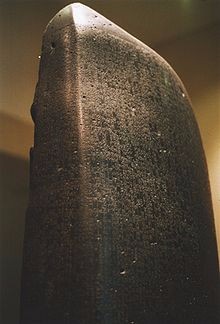

Discovery of the Code

Archaeologists, including Egyptologist Gustave Jequier, discovered the code in 1901 at the ancient site of Susa in Khuzestan; a translation was published in 1902 by Jean-Vincent Scheil. A basalt stele containing the code in cuneiform script inscribed in the Akkadian language is currently on display in the Louvre, in Paris, France. Replicas are located at other museums throughout the world.

The Code of Hammurabi

This basalt stele has the Code of Hammurabi inscribed in cuneiform script in the Akkadian language.

2.3.3: Babylonian Culture

Hallmarks of Babylonian culture include mudbrick architecture, extensive astronomical records and logs, diagnostic medical handbooks, and translations of Sumerian literature.

Learning Objective

Evaluate the extent and influence of Babylonian culture

Key Points

- Babylonian temples were massive structures of crude brick, supported by buttresses. Such uses of brick led to the early development of the pilaster and column, and of frescoes and enameled tiles.

- Certain pieces of Babylonian art featured crude three-dimensional statues, and gem-cutting was considered a high-perfection art.

- The Babylonians produced extensive compendiums of astronomical records containing catalogues of stars and constellations, as well as schemes for calculating various astronomical coordinates and phenomena.

- Medicinally, the Babylonians introduced basic medical processes, such as diagnosis and prognosis, and also catalogued a variety of illnesses with their symptoms.

- Both Babylonian men and women learned to read and write, and much of Babylonian literature is translated from ancient Sumerian texts, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Key Terms

- Epic of Gilgamesh

-

One of the most famous Babylonian works, a twelve-book saga translated from the original Sumerian.

- pilaster

-

An architectural element in classical architecture used to give the appearance of a supporting column and to articulate an extent of wall, with only an ornamental function.

- etiology

-

Causation. In medicine, cause or origin of disease or condition.

- mudbrick

-

A brick mixture of loam, mud, sand, and water mixed with a binding material, such as rice husks or straw.

- Enūma Anu Enlil

-

A series of cuneiform tablets containing centuries of Babylonian observations of celestial phenomena.

- Diagnostic Handbook

-

The most extensive Babylonian medical text, written by Esagil-kin-apli of Borsippa.

Art and Architecture

In Babylonia, an abundance of clay and lack of stone led to greater use of mudbrick. Babylonian temples were thus massive structures of crude brick, supported by buttresses. The use of brick led to the early development of the pilaster and column, and of frescoes and enameled tiles. The walls were brilliantly colored, and sometimes plated with zinc or gold, as well as with tiles. Painted terracotta cones for torches were also embedded in the plaster. In Babylonia, in place of the bas-relief, there was a preponderance of three-dimensional figures—the earliest examples being the Statues of Gudea—that were realistic, if also somewhat clumsy. The paucity of stone in Babylonia made every pebble a commodity and led to a high perfection in the art of gem-cutting.

Astronomy

During the 8th and 7th centuries BCE, Babylonian astronomers developed a new empirical approach to astronomy. They began studying philosophy dealing with the ideal nature of the universe and began employing an internal logic within their predictive planetary systems. This was an important contribution to astronomy and the philosophy of science, and some scholars have thus referred to this new approach as the first scientific revolution. Tablets dating back to the Old Babylonian period document the application of mathematics to variations in the length of daylight over a solar year. Centuries of Babylonian observations of celestial phenomena are recorded in a series of cuneiform tablets known as the “Enūma Anu Enlil.” In fact, the oldest significant astronomical text known to mankind is Tablet 63 of the Enūma Anu Enlil, the Venus tablet of Ammi-saduqa, which lists the first and last visible risings of Venus over a period of about 21 years. This record is the earliest evidence that planets were recognized as periodic phenomena. The oldest rectangular astrolabe dates back to Babylonia c. 1100 BCE. The MUL.APIN contains catalogues of stars and constellations as well as schemes for predicting heliacal risings and the settings of the planets, as well as lengths of daylight measured by a water-clock, gnomon, shadows, and intercalations. The Babylonian GU text arranges stars in “strings” that lie along declination circles (thus measuring right-ascensions or time-intervals), and also employs the stars of the zenith, which are also separated by given right-ascensional differences.

Medicine

The oldest Babylonian texts on medicine date back to the First Babylonian Dynasty in the first half of the 2nd millennium BCE. The most extensive Babylonian medical text, however, is the Diagnostic Handbook written by the ummânū, or chief scholar, Esagil-kin-apli of Borsippa.

The Babylonians introduced the concepts of diagnosis, prognosis, physical examination, and prescriptions. The Diagnostic Handbook additionally introduced the methods of therapy and etiology outlining the use of empiricism, logic, and rationality in diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. For example, the text contains a list of medical symptoms and often detailed empirical observations along with logical rules used in combining observed symptoms on the body of a patient with its diagnosis and prognosis. In particular, Esagil-kin-apli discovered a variety of illnesses and diseases and described their symptoms in his Diagnostic Handbook, including those of many varieties of epilepsy and related ailments.

Literature

Libraries existed in most towns and temples. Women as well as men learned to read and write, and had knowledge of the extinct Sumerian language, along with a complicated and extensive syllabary.

A considerable amount of Babylonian literature was translated from Sumerian originals, and the language of religion and law long continued to be written in the old agglutinative language of Sumer. Vocabularies, grammars, and interlinear translations were compiled for the use of students, as well as commentaries on the older texts and explanations of obscure words and phrases. The characters of the syllabary were organized and named, and elaborate lists of them were drawn up.

There are many Babylonian literary works whose titles have come down to us. One of the most famous of these was the Epic of Gilgamesh, in twelve books, translated from the original Sumerian by a certain Sin-liqi-unninni, and arranged upon an astronomical principle. Each division contains the story of a single adventure in the career of King Gilgamesh. The whole story is a composite product, and it is probable that some of the stories are artificially attached to the central figure.

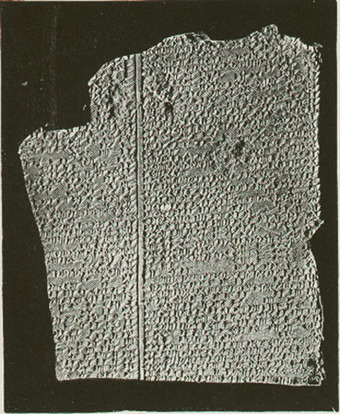

A Tablet from the Epic of Gilgamesh

The Deluge tablet of the Gilgamesh epic in Akkadian.

Philosophy

The origins of Babylonian philosophy can be traced back to early Mesopotamian wisdom literature, which embodied certain philosophies of life, particularly ethics, in the forms of dialectic, dialogs, epic poetry, folklore, hymns, lyrics, prose, and proverbs. Babylonian reasoning and rationality developed beyond empirical observation. It is possible that Babylonian philosophy had an influence on Greek philosophy, particularly Hellenistic philosophy. The Babylonian text Dialogue of Pessimism contains similarities to the agonistic thought of the sophists, the Heraclitean doctrine of contrasts, and the dialogs of Plato, as well as a precursor to the maieutic Socratic method of Socrates.

Neo-Babylonian Culture

The resurgence of Babylonian culture in the 7th and 6th century BCE resulted in a number of developments. In astronomy, a new approach was developed, based on the philosophy of the ideal nature of the early universe, and an internal logic within their predictive planetary systems. Some scholars have called this the first scientific revolution, and it was later adopted by Greek astronomers. The Babylonian astronomer Seleucus of Seleucia (b. 190 BCE) supported a heliocentric model of planetary motion. In mathematics, the Babylonians devised the base 60 numeral system, determined the square root of two correctly to seven places, and demonstrated knowledge of the Pythagorean theorem before Pythagoras.

2.3.4: Nebuchadnezzar and the Fall of Babylon

The Kassite Dynasty ruled Babylonia following the fall of Hammurabi and was succeeded by the Second Dynasty of Isin, during which time the Babylonians experienced military success and cultural upheavals under Nebuchadnezzar.

Learning Objective

Describe the key characteristics of the Second Dynasty of Isin

Key Points

- Following the collapse of the First Babylonian Dynasty under Hammurabi, the Babylonian Empire entered a period of relatively weakened rule under the Kassites for 576 years. The Kassite Dynasty eventually fell itself due to the loss of territory and military weakness.

- The Kassites were succeeded by the Elamites, who themselves were conquered by Marduk-kabit-ahheshu, the founder of the Second Dynasty of Isin.

- Nebuchadnezzar I was the most famous ruler of the Second Dynasty of Isin. He enjoyed military successes for the first part of his career, then turned to peaceful building projects in his later years.

- The Babylonian Empire suffered major blows to its power when Nebuchadnezzar’s sons lost a series of wars with Assyria, and their successors effectively became vassals of the Assyrian king. Babylonia descended into a period of chaos in 1026 BCE.

Key Terms

- Assyrian Empire

-

A major Semitic empire of the Ancient Near East which existed as an independent state for a period of approximately nineteen centuries.

- Nebuchadnezzar I

-

The most famous ruler of the Second Dynasty of Isin, who sacked the Elamite capital of Susa and devoted himself to peaceful building projects after securing Babylonia’s borders.

- Elamites

-

An ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran.

- Kassite Dynasty

-

An ancient Near Eastern people who controlled Babylonia for nearly 600 years after the fall of the First Babylonian Dynasty.

- Marduk-kabit-ahheshu

-

Overthrower of the Elamites and the founder of the Second Dynasty of Isin.

- Kudurru

-

A type of stone document used as boundary stones and as records of land grants to vassals by the Kassites in ancient Babylonia.

The Fall of the Kassite Dynasty and the Rise of the Second Dynasty of Isin

Following the collapse of the First Babylonian Dynasty under Hammurabi, the Babylonian Empire entered a period of relatively weakened rule under the Kassites for 576 years—

the longest dynasty in Babylonian history. The Kassite Dynasty eventually fell due to the loss of territory and military weakness, which resulted in the evident reduction in literacy and culture. In 1157 BCE, Babylon was conquered by Shutruk-Nahhunte of Elam.

The Elamites did not remain in control of Babylonia long, and Marduk-kabit-ahheshu (1155-1139 BCE) established the Second Dynasty of Isin. This dynasty was the very first native Akkadian-speaking south Mesopotamian dynasty to rule Babylon, and was to remain in power for some 125 years. The new king successfully drove out the Elamites and prevented any possible Kassite revival. Later in his reign, he went to war with Assyria and had some initial success before suffering defeat at the hands of the Assyrian king Ashur-Dan I. He was succeeded by his son Itti-Marduk-balatu in 1138 BCE, who was followed a year later by Ninurta-nadin-shumi in 1137 BCE.

The Reign of Nebuchadnezzar I and His Sons

Nebuchadnezzar I (1124-1103 BCE) was the most famous ruler of the Second Dynasty of Isin. He not only fought and defeated the Elamites and drove them from Babylonian territory but invaded Elam itself, sacked the Elamite capital Susa, and recovered the sacred statue of Marduk that had been carried off from Babylon. In the later years of his reign, he devoted himself to peaceful building projects and securing Babylonia’s borders. His construction activities are memorialized in building inscriptions of the Ekituš-ḫegal-tila, the temple of Adad in Babylon, and on bricks from the temple of Enlil in Nippur. A late Babylonian inventory lists his donations of gold vessels in Ur. The earliest of three extant economic texts is dated to Nebuchadnezzar’s eighth year; in addition to two kudurrus and a stone memorial tablet, they form the only existing commercial records. These artifacts evidence the dynasty’s power as builders, craftsmen, and managers of the business of the empire.

The Kudurru of Nebuchadnezzar

This detail depicts Nebuchadnezzar granting Marduk freedom from taxation.

Nebuchadnezzar was succeeded by his two sons, firstly Enlil-nadin-apli (1103-1100 BCE), who lost territory to Assyria, and then Marduk-nadin-ahhe (1098-1081 BCE), who also went to war with Assyria. Some initial success in these conflicts gave way to catastrophic defeat at the hands of Tiglath-pileser I, who annexed huge swathes of Babylonian territory, thereby further expanding the Assyrian Empire. Following this military defeat, a terrible famine gripped Babylon, which invited attacks from Semitic Aramean tribes from the west.

In 1072 BCE, King Marduk-shapik-zeri signed a peace treaty with Ashur-bel-kala of Assyria. His successor, Kadašman-Buriaš, however, did not maintain his predecessor’s peaceful intentions, and his actions prompted the Assyrian king to invade Babylonia and place his own man on the throne. Assyrian domination continued until c. 1050 BCE, with the two reigning Babylonian kings regarded as vassals of Assyria. Assyria descended into a period of civil war after 1050 BCE, which allowed Babylonia to once more largely free itself from the Assyrian yoke for a few decades.

However, Babylonia soon began to suffer repeated incursions from Semitic nomadic peoples migrating from the west, and large swathes of Babylonia were appropriated and occupied by these newly arrived Arameans, Chaldeans, and Suteans. Starting in 1026 and lasting till 911 BCE, Babylonia descended into a period of chaos.