16.1: South American Civilizations

16.1.1: The Moche

The Moche culture lasted from 100 to 800 CE in what is modern-day Peru.

Learning Objective

Identify key aspects of Moche life

Key Points

- The Moche were less of a state or empire and more of a society—they lived in a general geographic area and shared cultural values, but were not governed under a uniform political system.

- The Moche practiced a number of religious rituals, some of which involved human sacrifice.

- Moche art appears in a variety of mediums, such as ceramics, architecture, and textiles, and lends insight into their beliefs and culture.

Key Terms

- Decapitator

-

A Moche icon, usually depicted as a spider, and associated with ritual sacrifices and the elements of land, air, and water.

- Moche

-

A city in modern-day Peru, which is also where the Moche culture was centered.

- vicuña

-

A wild South American camelid that lives in the high alpine areas of the Andes. It is a relative of the llama, and is now believed to be the wild ancestor of domesticated alpacas, which are raised for their coats.

- Huaca

-

A large, pyramid-like structure made of adobe bricks and used as a palace, ritual site, temple, and administrative center.

The Moche (also known as the Early Chimú or Mochica) lived in what is modern-day Peru, near Moche and Trujillo. Their civilization lasted from approximately 100 to 800 CE. The Moche shared cultural values and social structures within a distinct geographical region. However, scholars suggest this civilization functioned as individual city-states, sharing similar cultural elite classes, rather than as an empire or a single political system.

The Moche cultural sphere centered around several valleys along the north coast of Peru, and occupied 250 miles of desert coastline that extended up to 50 miles inland. Moche society was agriculturally based, but because of the arid climate, they invested heavily in the construction of a network of irrigation canals. These ornate canals diverted river water to crops across the region. The Moche are also noted for their expansive ceremonial architecture (huacas), elaborately painted ceramics, and woven textiles.

Religion

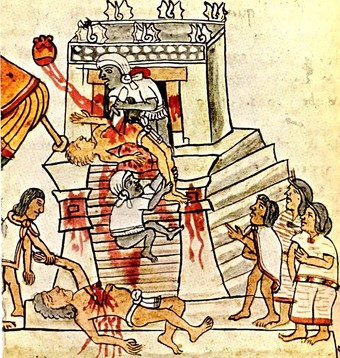

Both iconography and the discovery of human skeletons in ritual contexts seem to indicate that human sacrifice played a significant part in Moche religious practices. These rites appear to have involved the elite, both ruling men and women, as key actors in an elaborate spectacle. These rituals included:

- Costumed participants, including elite priests and priestesses, many of which also ruled the city-states;

- Monumental settings, including the pyramid-like structures called huacas; and

- Likely the consumption of human blood and possibly flesh as a part of a renewal ritual.

The Moche may have also held and tortured the victims for several weeks before sacrificing them, with the intent of deliberately drawing blood. The sacrifices may have been associated with rites of ancestral renewal and agricultural fertility.

Moche iconography features a figure, which scholars have nicknamed the “Decapitator” or Ai Apaec. It is frequently depicted as a spider, but sometimes as a winged creature or a sea monster. Together, all three features symbolize land, water, and air. When the body is included, the figure is usually shown with one arm holding a knife and another holding a severed head by the hair. It has also been depicted as “a human figure with a tiger’s mouth and snarling fangs.”

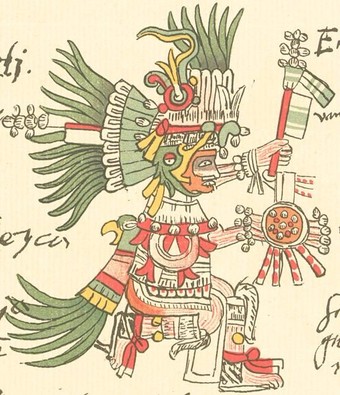

Moche Decapitator

A mural depicting the Decapitator, a central Moche icon of the land, water, and air as well as a figure of death and renewal.

Architecture

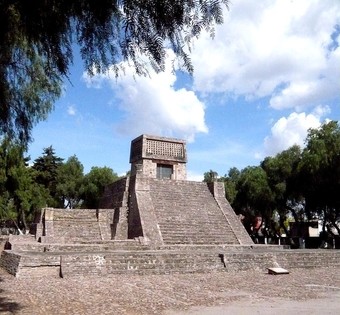

The Huaca del Sol, a pyramidal adobe structure on the Rio Moche, was the largest pre-Columbian structure in Peru. Huacas were the centerpieces for ritual sites and used as administrative centers and palaces for Moche culture. However, the Huaca del Sol was partly destroyed when Spanish Conquistadores mined its graves for gold in the 16th century. During the Spanish occupation of Peru in the early 17th century, colonists redirected the waters of the Moche River to run past the base of the Huaca del Sol in order to facilitate the looting of gold artifacts from the temple, which caused massive erosion. In total, approximately two-thirds of the structure has been lost to erosion and such looting. The remaining structure stands at a height of 41 meters (135 feet). Looting and erosion due to El Niño continue to be major concerns to this day

Huaca del Sol

Originally the largest pre-Columbian adobe structure in the Americas, this pyramid was constructed using around 130 million bricks.

The nearby Huaca de la Luna is better preserved. Its interior walls contain many colorful murals with complex iconography. The site has been under professional archaeological excavation since the early 1990s.

A view of the Huaca de la Luna, with Cerro Blanco in the background

When this structure was originally completed it would have been covered in brightly painted murals in yellows, blues, reds, and black.

Art

The Moche are well known for their art, especially their naturalistic and articulate ceramics, particularly in the form of stirrup-spout vessels. The ceramics incorporate a wide-ranging subject matter, both in shape and painted decorations, including representations of people, animals, and ritual scenes. They also feature gods hunting, scenes of war, music making, visiting rulers, burying the dead, curing the sick, and anthropomorphic iconography. Moche ceramics illustrate these recurring narrative themes, which help illuminate and define their ideologies in the present day.

Some of the ceramics have become known as “sex-pots”: vessels depicting sexual acts. It is thought that these vessels were used for didactic purposes, and also as articulations of Moche culture. Because irrigation was the source of wealth and foundation of the empire, the Moche culture emphasized the importance of circulation and flow. Sexual themes in the pottery are posited to reflect Moche views of bodily fluids as an essential life force.

The Moche also wove textiles, mostly using wool from vicuñas and alpacas. Although there are few surviving examples of this, descendants of the Moche people have strong weaving traditions.

Collapse

There are several theories as to what caused the demise of the Moche political structure. Some scholars have emphasized the role of environmental change. Studies of ice cores drilled from glaciers in the Andes reveal climatic events between 536 and 594 CE, possibly a super El Niño, that resulted in thirty years of intense rain and flooding followed by thirty years of drought, part of the aftermath of the climate changes of 535–536. These weather events could have disrupted the Moche way of life and shattered their faith in their religion, which had promised stable weather through sacrifices.

Other evidence demonstrates that these events did not cause the final Moche demise. Moche polities survived beyond 650 in the Jequetepeque Valley and the Moche Valleys. For instance, in the Jequetepeque Valley, later settlements are characterized by fortifications and defensive works. While there is no evidence of a foreign invasion, as many scholars have suggested in the past, the defensive works suggest social unrest, possibly the result of climate change, as factions fought for control over increasingly scarce resources.

16.1.2: The Nazca

The Nazca lived near the southern coast of Peru from 100 BCE to 800 CE.

Learning Objective

Explain the culture, religion, agriculture, and decline of the Nazca civilization

Key Points

- Early Nazca society was made up of local chiefdoms and regional centers of power centered around the ritual site of Cahuachi.

- The Nazca are known for their Nazca Lines—geometric shapes, lines, and animal figures carved into the desert floor.

- Like the Moche, the Nazca decline was likely due to environmental changes.

Key Terms

- Nazca Lines

-

A series of geometric shapes, miles of lines, and large drawings of animal figures created by the Nazca culture.

- shamans

-

Spiritual practitioners that reach altered states of consciousness in order to encounter and interact with the spirit world and channel these transcendental energies into this world for healing and divination purposes.

- Trephination

-

This primitive surgery removed a piece of bone from the skull, while the person was still alive, to allow drainage after a head injury.

The Nazca (or Nasca) lived near the arid southern coast of Peru from 100 BCE to 800 CE. Early Nazca society was made up of local chiefdoms and regional centers of power centered around Cahuachi, a non-urban ceremonial site of earthwork mounds and plazas. These pyramid-like structures and plazas, situated in the lower part of the Nazca Valley, served as important spaces for fertility and agricultural rituals. People from across the Nazca region most likely gathered in Cahuachi during specific times of the year to feast and make offerings.

The Nazca developed underground aqueducts, named puquios, to sustain cities and agriculture in this arid climate. Many of them still function today. They also created complex textiles and ceramics reflecting their agricultural and sacrificial traditions.

Society and Religion

Likely related to the arid and extreme nature of the environment, Nazca religious beliefs were based upon agriculture and fertility. Much of Nazca art depicts powerful nature gods, such as the mythical killer whale, the harvesters, the mythical spotted cat, the hummingbird, and the serpentine entity. As in the contemporary Moche culture based in northwest Peru, shamans apparently used hallucinogenic drugs, such as extractions from the San Pedro cactus, to induce visions during ceremonies.

Killer whale (Orca)

Powerful nature gods were an essential element of the Nazca religious culture, which centered around agriculture.

Nazca Lines

The geoglyphs of Nazca, or “Nazca Lines,” are a series of geometric shapes, extended lines that run for miles, and large drawings of animal figures (some as large as a football field) constructed on the desert floor in the Nazca region. A large number of people over an extended period of time could have constructed the lines.

Researchers have demonstrated techniques to explore how this was done. By extending a rope between two posts and removing the red pebbles on the desert surface along the rope, the lines could have been constructed. The contrast of the red desert pebbles and the lighter earth beneath would make the lines visible from a high altitude. Due to the simplistic construction of the geoglyphs, regular amounts of rainfall would have easily eroded the drawings, but the dry desert environment has preserved the lines for hundreds of years. Several theories have been posited as to why the Nazca Lines exist, but the true meaning of the geoglyphs remains a mystery.

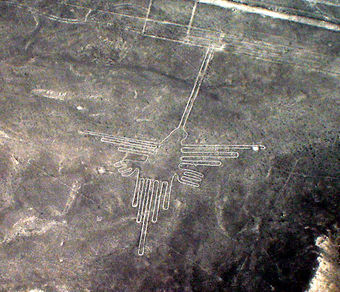

Nazca Lines

These Nazca lines, called The Hummingbird, are representative of the type of structures that remain.

Agriculture and Diet

Nazca subsistence was based largely on agriculture. Iconography on ceramics and excavated remains indicate that the Nazca people had a varied diet, including:

- Maize

- Squash

- Sweet potatoes

- Beans

- Manioc (also known as Yuca)

- Achira

- Small amounts of fish

- Peanuts

They also grew several non-food crops, such as cotton for textiles, coca, San Pedro cactus, and gourds. The latter were decorated to illustrate activities in daily life. The presence of coca is evident in pottery and artwork. The leaves of this plant were chewed and worked as a stimulant that suppressed hunger, pain, thirst, and fatigue. The hallucinogenic San Pedro cactus also appears on several polychrome pots and bowls showcasing its ceremonial significance.

In terms of animal resources, the Nazca made sacrifices of llamas and guinea pigs at Cahuachi. Llamas were also commonly exploited as pack animals, for their wool, and as a source of meat.

San Pedro cactus

This plant, Echinopsis pachanoi, has hallucinogenic properties, which shamans of the Nazca culture utilized in ceremonies.

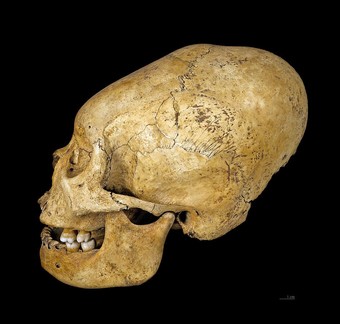

Trephination and Cranial Manipulation

Trephination was a primitive skull surgery used by the Nazca that relieved pressure on the brain from battle wounds or for ritual purposes. It entails the removal of one or more sections of bone from the skull, while the person is still alive. Evidence of trephination has been seen through the analysis of excavated skulls. Some of the skulls show signs of healing, evidence that some individuals who underwent the procedure survived.

Elongated skulls, as a result of skull manipulation, were also seen in the excavations from Cahuachi. This effect was achieved by binding a cushion to an infant’s forehead and a board to the back of the head. Archaeologists can only speculate as to why this was done to some of the skulls. Several theories suggest skull manipulation created an ethnic identity, formed the individual into a social being, or may have illustrated social status.

Decline of the Nazca

Like the Moche, who lived along the arid northern coast of Peru during the same time period, it is thought that the Nazca may have been forced into decline by environmental changes. This is thought to have occurred when an El Niño triggered widespread and destructive flooding, leaving the civilization unstable by 750 CE. Evidence also suggests that the Nazca people may have exacerbated the effects of these floods by gradually cutting down Prosopis pallida trees to make room for maize and cotton agriculture. These trees play an extremely important role as an ecological keystone of this landscape, in particular preventing river and wind erosion. Gradual removal of trees would have exposed the landscape to the effects of climate perturbations such as El Niño, leading to erosion and leaving irrigation systems high and dry.

16.1.3: The Sicán

The Sicán culture inhabited what is now the north coast of Peru between about 750 and 1375 CE.

Learning Objective

Explain the unique aspects of the Sicán and what led to their downfall

Key Points

- In the Early Sicán period (750–900 CE) the Sicán began to establish trade and commerce.

- The Middle Sicán period (900–1100 CE) saw an explosion of culture and art, along with the development of extensive trading routes.

- Environmental changes caused unrest in the Late Sicán period (1100–1375), but the ultimate end to the Sicán came when they were conquered by the Chimú.

Key Terms

- tumbaga

-

A thin sheet of low-karat gold alloy, which was used to decorate symbolic metal vessels for lower elites.

- Sicán Precinct

-

The religious and cultural center of the Sicán culture.

- Sicán Deity

-

The central religious figure of the Middle Sicán period. This entity represented water, the ocean, and natural resources. It was also the social underpinning of the theocratic state.

The Sicán culture inhabited what is now the north coast of Peru between about 750 CE and 1375 CE. They succeeded the Moche culture, but there is still controversy among archeologists and anthropologists over whether the two are separate cultures.

Early Sicán Period

The Early Sicán period began around 750 CE and lasted until 900 CE. The lack of artifacts has limited the development of knowledge about this early period. Based on common themes, the Sicán were probably direct descendants of the Moche and developed their new culture during an unstable time in the region.

From remains found in archaeological locations, researchers have determined that this culture maintained commercial exchange with people from present-day Ecuador, Colombia, and Chile, and the eastern basin of the Marañón River.

The Early Sicán culture is known for the highly polished, black-finish ceramics found in the La Leche Valley. This black-finish ceramic style began in the Moche culture prior to the Early Sicán, and demonstrates the sharing of cultures in the region. Many of the ceramics were examples of a single spout, loop-handle bottle, featuring an anthropomorphic-avian (bird) face at the spout base. The face consisted of bulging eyes, a hooked beak or triangular projection instead of a nose, stylized ears, and no mouth. It appeared to be a predecessor to the related faces of the Sicán Deity and the Sicán Lord of the Middle Sicán culture.

Ceremonial mask

Peru, north coast, La Leche Valley, 900–1100 CE.

Aside from the shared ceramic styles, much of the Early Sicán defines a distinguishable culture. While the ceramic styles and iconography show some continuity with previous cultures, the changing iconography, ceramic themes, and funerary practices reflect a change in religious ideology and cosmology that expressed the Sicán culture.

Most importantly, the late Early Sicán period saw a major organizational and religious shift, by which the Sicán constructed monumental adobe structures, developed large-scale copper alloy smelting and metalworking, and developed the elaborate funerary tradition that would come to characterize the Middle Sicán. Such changes have been noted by researchers at sites in Batan Grande, including the Huaca del Pueblo site, dated to around 850–900 CE.

Middle Sicán Period

The Middle Sicán period lasted from 900 to 1100 CE. This is the period of the Sicán’s “cultural florescence,” and was marked by the emergence of various cultural innovations, some of which were unprecedented in the local area. The Sicán culture had a highly productive economy, clear social differentiation, and an influential religious ideology. This religious ideology served as the underpinning of the social hierarchy of the theocratic state.

The precious metal objects found in Middle Sicán sites reveal the unprecedented scale of their production and use, as well as the class hierarchy inherent in Sicán culture. Metal objects permeated all levels of society. Tumbaga, a thin sheet of low-karat gold alloy, was used to wrap ceramic vessels for the lower elites, while the upper elites had high-karat gold alloys. Common laborers had only arsenical copper objects.

Gold beaker

A 9th—11th century gold beaker exemplary of Middle Sicán art and craftsmanship.

Funerary Practices of the Middle Sicán

Funerary practices at Huaca Loro reflected the social differentiation and hierarchy present in Sicán society. This social stratification is revealed in varying burial types and practices, along with accompanying grave goods. The most obvious difference in burial type based on social hierarchy was that commoners were buried in simple, shallow graves on the peripheries of the monumental mounds while the elite were buried in deep shaft tombs beneath monumental mounds. It was found that one’s social status was also a determinant of the burial position of the body—whether it was seated, extended, or flexed. Bodies of the high elite were always buried in the seated position, while commoners could be buried in a seated, extended, or flexed position.

Social stratification and hierarchy is also evidenced through the variation in quantity and quality of grave goods for different social classes. The elite East Tomb at Huaca Loro contained over a ton of diverse grave goods, over two-thirds of which were objects of arsenical bronze, tumbaga, silver and copper alloys, and high-karat gold alloys. Other grave goods of the elite included:

- Semi-precious stone objects

- Amber

- Feathers

- Textiles

- Imported shells (such as conus and spondylus)

- Shell beads

- Double spout bottles

All of these items required hours of labor and precious supplies, highlighting the power of the elite. On the other hand, commoners had significantly fewer grave goods of different types, made of less valuable materials. For example, commoner grave goods at Huaca Loro were usually restricted to single-spout bottles, utilitarian plain and/or paddle decorated pottery, and copper-arsenic objects, instead of the precious metal objects of the elite tombs.

Religious Cities and Elite Culture

The Sicán culture was characterized by the establishment of religious cities with monumental temples. The religious capital city and cultural center of the Middle Sicán is referenced as the Sicán Precinct, which is defined by a number of monumental rounds. The pyramidal monumental mounds were used as both burials sites for the elite and places of worship and ritual. The construction of these mounds required considerable material, manpower, and time, indicating the Sicán elite’s control and monopoly over the society’s resources.

None of the metalworking sites showed evidence of on-site mining of any materials. In addition, the spondylus shell, emeralds, feathers, and other minerals were imported to the area. Their materials came from mainly the Northern Andes, but could have also come from as far south as the Tiwanaku lands in the South Central Andes and as far east as the Marañón River, a major Amazon River tributary. The Sicán also could have controlled the transport methods in addition to the goods being traded. The breeding and herding of llamas on the north coast since the time of the Moche could have been utilized by the Sicán to provide caravans of llamas to transport the goods considerable distances.

Late Sicán Period

The Late Sicán period began around 1100 CE and ended with the Chimú conquest of the Lambayeque region around 1375 CE.

Around 1020 CE, a major drought lasting thirty years occurred at Sicán. At the time of the drought, the Sicán Deity, so closely tied to the ocean and water in general, was at the center of Sicán religion, and appeared in most major artistic motifs. The catastrophic changes in weather were thus linked to the Sicán Deity, mainly to the failure of the deity to mediate nature for the Sicán people. The Sicán ceremonies (and mounds on which they were performed) were supposed to ensure that there was an abundance of resources for the people. After thirty years of uncertainty in respect to nature, the temples that were the center of Middle Sicán religion and elite power were burned and abandoned, between 1050 and 1100 CE.

Perhaps the ancestor cult and aggrandizing of the elites caused too much resentment. Coupled with the drought that surely weakened agriculture in the area, the tolerance of the common population plummeted, forcing the removal of the political and religious leadership at Sicán.

Religious mounds at Túcume

The last capital of the Sicán culture was located just south of the La Leche River, where they built twenty-six new religious mounds.

The Sicán then built a new capital at Túcume, also known as Purgatorio by local people today, where they thrived for another 250 years. The Sicán were able to build twenty-six ceremonial mounds in this new capital in that time period. However, in 1375, the Chimú conquered the area, marking the end of the Sicán era.

16.1.4: Chimú

The Chimú lived in modern-day Peru from 900–1470 CE.

Learning Objective

Discuss distinguishing aspects of Chimú religion, craftsmanship, and agriculture

Key Points

- The Chimú expanded to cover a vast area and include many different ethnic groups along the northern coast of modern-day Peru.

- Chimú artisans made notable multi-colored textiles and monochromatic pottery and metalwork.

- In 1470, the Chimú were conquered by the Inca.

- The Chimú worshipped the Moon as the essential deity of fertility, good weather, and bountiful crops.

Key Terms

- Chan Chan

-

The capital of the Chimú culture. It is in modern-day Peru.

- Chimor

-

The long swath of land along the northern coast of Peru that was ruled by the Chimú elite.

- ciudadela

-

Any one of a number of walled cities in the Chimú capital of Chan Chan where elites consolidated power and artisans lived in organized groups to make prestige goods.

The Chimú were a culture that lasted from approximately 900 CE until 1470 CE along the northern coast of modern-day Peru, centered in the city of Chan Chan. This is not to be confused with the Early Chimú, a related group also known as the Moche that lived in the region until about 800 CE.

The Inca ruler Tupac Inca Yupanqui led a campaign that conquered the Chimú around 1470 CE. This was just fifty years before the arrival of the Spanish in the region. Consequently, Spanish chroniclers were able to record accounts of Chimú culture from individuals who had lived before the Inca conquest. Similarly, archaeological evidence suggests Chimor, the large coastal swath of land inhabited by Chimú culture, grew out of the remnants of Moche culture. Early Chimú ceramics in a high-sheen black, along with detailed and intricate precious metalworking, shared many of the same aspects as Moche craftsmanship.

The mature Chimú culture developed in roughly the same territory where the Moche had existed centuries before, which made the Chimú another coastal culture. It was developed in the Moche Valley south of present-day Lima, northeast of Huarmey, and grew to include central present-day Trujillo, where the bureaucratic and artisanal capital of Chan Chan developed.

The Chimú expansion also incorporated many different ethnic groups, including the Sicán culture, which lasted independently until 1375. At its peak, the Chimú advanced to the limits of the desert coast, to the Jequetepeque Valley in the north, and Carabayallo in the south. Their expansion southward was stopped by the military power of the great valley of Lima.

Agriculture and Bureaucracy

The Chimú expanded and gained power over their 500-year growth through intensive farming techniques and hydraulic works, which joined valleys to form complexes. A few of these landmark agricultural techniques included the following:

- Huachaques: These sunken farms included the removal of the top layer of earth and allowed farmers to work the moist, sandy soil underneath.

- Walk-in wells, similar to those of the Nazca, were developed to draw water.

- Large reservoirs were developed to retain water from river systems in this arid climate where water was an essential resource.

These systematic changes increased the productivity of the land, which multiplied Chimú wealth and likely contributed to the formation of a bureaucratic, hierarchical system.

The Chimú cultivated beans, sweet potatoes, papayas, and cotton with their reservoir and irrigation systems. This focus on large-scale irrigation persisted until the Late Intermediate period. At this point, there was a shift to a more specialized system that focused on importing and redistributing resources from satellite communities. There appears to have been a complex network of sites that provided goods and services for Chimú subsistence.

Many of these satellite areas produced commodities that the Chimú population based in the capital of Chan Chan could not. Some sites relied on marine resources, such as fish and precious shells. However, after the advent of agriculture, more sites developed further inland, where marine resources were harder to attain. These inland communities began raising llamas as a supplemental source of meat, but by the Late Intermediate period and Late Horizon, inland sites started to rely on llamas as an essential transportation and food resource.

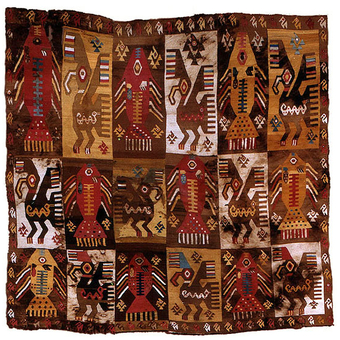

Chimú mantle

The Chimú are known for their artisanal works, such as this mantle spun of multiple colored fibers sometime from 1000 to 1476 CE.

Artisans

The capital of Chan Chan likely developed a complex bureaucracy due to the elite’s controlled access to information. This bureaucratic center imported raw materials from across Chimor, which were then processed into prestige goods by highly skilled artisans. The majority of the citizens in each ciudadela (walled cities in the capital of Chan Chan) were artisans. In the late Chimú, about 12,000 artisans lived and worked in Chan Chan alone. Artisans played an essential role in Chimú culture:

- They engaged in fishing, agriculture, craft work, and trade.

- Artisans were forbidden to change their profession, and were grouped in the ciudadela according to their area of specialization.

- Archeologists have noted a dramatic increase in Chimú craft production over time, and they believe that artisans may have been brought to Chan Chan from other areas taken as a result of Chimú conquest.

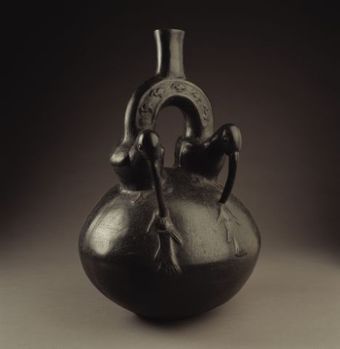

Chimú pottery

Chimú pottery is distinctly monochromatic and bears a striking resemblance to Moche pottery.

Pottery and Textiles

Though their textiles were multicolored, their pottery and metalwork are known for being monochromatic. The pottery is often in the shape of a creature, or has a human figure sitting or standing on a cuboid bottle. The shiny black finish of most Chimú pottery was achieved by firing the pottery at high temperatures in a closed kiln, which prevented oxygen from reacting with the clay.

Deities

The Chimú worshipped the Moon (Si) and considered it the greatest and most powerful of the deities. It was believed to be more powerful than the Sun, as it appeared by night and day, and was deeply linked with patterns in weather, fertility, and the growth of crops. Sacrifices of spondylus shells and other precious items were made to the Moon. Devotees sacrificed their own children on piles of colored cotton with offerings of fruit and chicha. They believed the sacrificed children, normally around the age of five, would become deified.

Spondylus

Spondylus shells were used as a currency and as offerings to the deities.

Animals and birds were also sacrificed to the Moon in order to appease this powerful entity. Two of the stars of Orion’s Belt were considered to be the emissaries of the Moon. The constellation Fur (the Pleiades) was also used to calculate the year and was believed to watch over the crops.

The Sun was associated with stones called alaec-pong (cacique stone). These stones were believed to be ancestors of the people in the areas they were found. They were also considered to be sons of the Sun deity. Along with the Sun, the Sea (Ni) was also a very important deity, and sacrifices of white maize flour, red ochre, and other precious items were made to it. Prayers for fish and protection against drowning were also offered. Shrines (called huacas) developed in each district across Chimor, dedicated to an associated legend, deity, or cult of belief, depending on the region.

The Fall of the Chimú

The end of the Chimú was brought about in the 1470s. They were conquered by the Inca ruler Tupac Inca Yupanqui, who led a fierce and well organized army northward. The Chimú were considered the last substantial rival culture standing in the way of the Inca conquest of the region.

16.2: The Inca

16.2.1: The Inca People

The Inca Empire was the largest of the pre-Columbian mesoamerican empires.

Learning Objective

Explain Inca agriculture, clothing, commodities, and architecture, and how these elements shaped their complex society.

Key Points

- Centered in Cusco, the Inca Empire extended from modern-day Chile to modern-day Colombia.

- Inca society was sophisticated, and boasted around seventy different crops across the empire’s various climates.

- The Inca considered finely woven textiles to be an essential commodity, and spun various grades of cloth from llama and vicuña wool.

Key Terms

- quinoa

-

This grain crop produces edible seeds that are high in protein and played an essential role in the Inca diet.

- Machu Picchu

-

This Inca citadel was probably built for the emperor Pachacutec around 1450 CE in the Andes at a height of around 8,000 feet above sea level using dry stone masonry.

- awaska

-

A lower-grade textile woven from llama wool and used for everyday household chores and cleaning.

The Inca Empire, or Inka Empire, was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The civilization emerged in the 13th century and lasted until it was conquered by the Spanish in 1572. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was located in Cusco (also spelled Cuzco) in modern-day Peru. From 1438 to 1533, the Incas used a variety of methods, from conquest to peaceful assimilation, to incorporate a large portion of western South America. Beginning with the rule of Pachacuti-Cusi Yupanqui, the Inca expanded their borders to include large parts of modern Ecuador, Peru, western and south-central Bolivia, northwest Argentina, north and north-central Chile, and southern Colombia. This vast territory was known in Quechua (the language of the Inca Empire) as Tawantin Suyu, or the Four Regions, which met in the capital of Cusco.

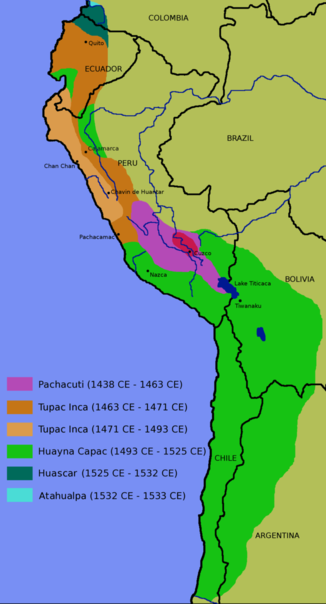

Inca Empire

From 1438 to 1533, the Inca Empire expanded significantly.

Architecture and Masonry

Architecture illustrates the sophistication and technical skill typical of the Inca Empire. The main example of this resilient art form was the capital city of Cusco, which drew together the Four Regions. The Inca used a mortarless construction technique, called dry stone wall, that fit stones together so well that a knife could not be fitted through the stonework. This was a process first used on a large scale by the Pucara (c. 300 BCE–300 CE) peoples to the south in Lake Titicaca, and later in the great city of Tiwanaku (c. 400–1100 CE) in present-day Bolivia. The rocks used in construction were sculpted to fit together exactly by repeatedly lowering one rock onto another and carving away any sections on the lower rock where there was compression or the pieces did not fit exactly. The tight fit and the concavity on the lower rocks made them extraordinarily stable.

Machu Picchu was built around 1450, at the height of the Inca Empire. It is a rare example of this architectural building technique and remains in remarkable condition after many centuries. The construction of Machu Picchu appears to date from the period of the two great Inca emperors, Pachacutec Inca Yupanqui (1438–1471) and Tupac Inca Yupanqui (1472–1493), and was probably built as a temple for the emperor Pachacutec. Machu Picchu was abandoned just over 100 years later, in 1572, as a belated result of the Spanish Conquest, possibly related to smallpox.

Machu Picchu

This impressive mountain-top temple was built around 1450 CE using dry stone wall.

Textiles, Ceramics, and Metalwork

Textiles were one of the most precious commodities of the Inca culture and denoted a person’s social status, and often their profession. The brightly colored patterns on a wool tunic represented various positions and achievements. For example, a black-and-white checkerboard pattern topped with a pink triangle denoted a soldier. Because textiles were so specific to a person’s class and employment, citizens could not change their wardrobe without the express permission of the government. Textiles were also manufactured that could only be used for certain tasks or social arenas. A rougher textile, spun from llama wool and called awaska, was used for everyday household chores. On the other hand, a fine-spun, very soft cloth made from vicuña wool could only be used in religious ceremonies.

Inca tunic

The complex patterns woven into most Inca textiles and made into tunics, like this one, denoted a person’s position in society.

Although textiles were considered the most precious commodity in Inca culture, Incas also considered ceramics and metalwork essential commodities of the economy and class system. Incan pottery was distinctive and normally had a spherical body with a cone-shaped base. The pottery would also include curved handles and often featured animal heads, such as jaguars or birds. These ceramics were painted in bright colors, such as orange, red, black, and yellow.

The Inca also required every province to mine for precious metals like tin, silver, gold, and copper. The intricate metalwork of the Inca was heavily influenced by the Chimú culture, which was conquered and absorbed into the Inca culture around 1470. This metalwork included detailed friezes and patterns inlaid into the metal. Fine silver and gold were made into intricate decorative pieces for the emperors and elites based on these Chimú metallurgy traditions, and often included animal motifs with butterflies, jaguars, and llamas etched into the metal. Skilled metallurgists also transformed bronze and copper into farming implements, blades, axes, and pins for everyday activities.

Agriculture and Diet

The Inca culture boasted a wide variety of crops, numbering around seventy different strains in total, making it one of the most diverse crop cultures in the world. Some of these flavorful vegetables and grains included:

- Potatoes

- Sweet potatoes

- Maize

- Chili peppers

- Cotton

- Tomatoes

- Peanuts

- Oca

- Quinoa

- Amaranth

Terraced farmland in Peru

Terraces allowed Inca farmers to utilize the mountainous terrain and grow around seventy different crops.

These crops were grown in the high-altitude Andes by building terraced farms that allowed farmers to utilize the mineral-rich mountain soil. The quick change in altitude on these mountain farms also utilized the micro-climates of each terrace to grow a wider range of crops. The Inca also produced bounties in the Amazon rainforest and along the more arid coastline of modern-day Peru.

Alongside vegetables, the Inca supplemented their diet with fish, guinea pigs, camelid meat, and wild fowl. They also fermented maize, or corn, to create the alcoholic beverage chicha.

16.2.2: Administration of the Inca Empire

The Inca Empire utilized complex road systems, recording tools, and a hierarchical rule of law to oversee the administration of its vast population.

Learning Objective

Understand the importance of the governing bodies, road system, recording tools, and social hierarchy of the Inca Empire

Key Points

- The Inca Empire utilized a complex road system with about 25,000 miles of roads that relayed messages and goods throughout the society.

- Inca administrators used brightly colored knotted strings called quipus to keep precise records of labor, taxes, and goods.

- The Inca had no written legal code, but relied on magistrates and inspectors to keep people in line with established social customs.

Key Terms

- quipus

-

Brightly colored knotted strings that recorded numerical information, such as taxes, goods, and labor, using the base number of 10 to record data in knots.

- suyus

-

Distinct districts of the Inca Empire that all reported back to the capital of Cusco. There were four major districts during the height of the empire.

- ayllu

-

A clan-like family unit based upon a common ancestor.

Hierarchy

The

Inca Empire was a hierarchical system with the emperor, or Inca Sapa,

ruling over the rest of society. A number of religious officials and magistrates oversaw the

administration of the empire directly below the emperor. Kurakas were magistrates that served as the head of an ayllu, or clan-like family unit based on a common ancestor.

These leaders mitigated between the spiritual and physical worlds.

They also collected taxes, oversaw the day-to-day administration of

the empire in their regions, and even chose brides for men in their

communities. Some of the privileges kurakas enjoyed included exemption from taxation, the right to ride in a litter, and the

freedom to practice polygamy.

Society

was broken into two distinct parts. One segment was comprised of the common people, including those

cultures that had been subsumed by the Inca Empire. The second group was made up of the elite of

the empire, including the emperor and the kurakas, along with various

other dignitaries and blood relations. Education was vocationally based for commoners, while

the elite received a formal spiritual education.

There

was no codified legal system for people that broke with the

cultural and social norms. Local inspectors called okoyrikoq, or

“he who sees all,” reported back to the capital and the emperor

and made immediate decisions regarding punishment in cases where customs were not honored. Many

times these local inspectors were blood relatives of the emperor.

Road System

The Inca civilization was able to keep populations in line,

collect taxes efficiently, and move goods, messages, and military

resources across such a varied landscape because of the complex road

system. Measuring about 24,800 miles long, this road system connected

the the regions of the empire and was the most complex

and lengthy road system in South America at the time. Two main routes

connected the north and the south of the empire, with many smaller

branches extending to outposts to the east and west. The roads varied

in width and style because often the Inca leaders utilized roads that

already existed to create this powerful network. Common people

could not use these official roads unless they were given permission

by the government.

These

roads were used for relaying messages by way of chasqui, or human runners, who could run up to 150 miles a day with messages for

officials. Llamas and alpacas were also used to

distribute goods throughout the empire and ease trade relations.

The roads also had a ritual purpose because they allowed the highest leaders of the Inca Empire to

ascend into the Andes to perform religious rituals in sacred spaces,

such as Machu Picchu.

Chasqui carrying a quipu on official state business

Chasquis were highly agile long-distance runners who used the complex road systems to relay messages and goods between cities.

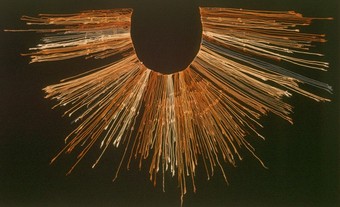

Record Keeping

The

Inca utilized a complex recording system to keep track of the administration of the empire. Quipus (also spelled khipus) were colorful bunches of knotted strings that recorded census data, taxes,

calendrical information, military organization, and accounting

information. These “talking knots” could contain anything from a

few threads to around 2,000, and used the base number of 10 to record

information in complex variations of knots and spaces.

Inca quipu

These complex recording devices allowed officials to keep track of taxes, labor, and goods in a precise fashion.

The

Spanish burned the vast majority of existing quipus when they arrived

in South America. However, there is some evidence to suggest that

these tools were also used to record stories and language for

posterity, and were not only numerical recording devices.

Trade

and Economics

Trade

and the movement of goods fed into what is called the vertical

archipelago. This system meant that all goods produced within the

empire were immediately property of the ruling elites. These elites,

such as the emperor and governors, then redistributed resources

across the empire as they saw fit.

Taxes

and goods were collected from four distinct suyus, or

districts, and sent directly to the ruling emperor in Cusco. This highly organized system was most likely

perfected under the emperor Pachacuti around 1460.

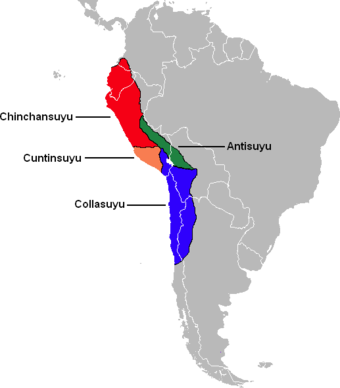

The Four suyus of the Inca Empire

The economic system linked together four large suyus, or districts, that all reported back to the capital of Cusco.

This

system also required a minimum quota of manual labor from the general

population. This form of labor taxation was called mita. The

populations of each district were expected to contribute to the

wealth of the empire by mining, farming, or doing other manual labor

that would benefit the entire empire. Precious metals, textiles, and

crops were collected and redistributed using the the road system that

snaked across the land, from the ocean to the Andes.

16.2.3: Religion in the Inca Empire

The Inca Empire worshipped the Sun god Inti, and expanded its hold on outlying areas by incorporating other deities into the religious system.

Learning Objective

Learn about the forms of worship of the Sun god Inti, the religious hierarchy, and the cultural assimilation of outlying clans in the Inca Empire

Key Points

- The Inca rulers worshipped the Sun god Inti and built the central temple, Qurikancha, in Cusco.

- The Inca elite incorporated the varied populations into the empire by allowing the worship of other deities.

- Various festivals celebrated the different aspects of the Sun. The most important of these festivals was Inti Raymi, which focused on abundance.

Key Terms

- Pachamama

-

The Earth goddess worshipped by many clans in outlying areas of the Inca Empire. Inca rulers enforced a religious system that favored Inti, but they incorporated the Earth goddess as a lesser deity.

- Inti

-

The central Sun god the Inca worshipped. He represented abundance, harvests, and fertility, and was considered more important than any other deity worshipped in the region.

- Inti Raymi

-

The most important religious festival of the Inca year. It means “Sun Festival” and occurred close to the winter solstice, which happens in June in South America.

The Inca religious system utilized oral traditions to pass down the mythology of their Sun god, Inti. This benevolent male deity was often represented as a gold disk with large rays and a human face. Golden disks were commonly displayed at temples across the Inca Empire and were also associated with the ruling emperor, who was supposed to be a direct descendent of Inti, and divinely powerful. Inti was also associated with the growth of crops and material abundance, especially in the high Andes, where the Inca centered their power.

Some myths state that this benevolent entity, along with Mama Killa, the Moon goddess, had children. Inti ordered these children, named Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo, to descend from the sky and onto Earth with a divine golden wedge. This wedge penetrated the earth, and they built the capital of Cusco and civilization on that very spot.

Inti Worship

Royalty were considered to be direct descendants of Inti and, therefore, able to

act as intermediaries between the physical and spiritual realms. The

high priest of Inti was called the Willaq

Umu.

He was often the brother or a direct blood relation of the Sapa Inca,

or emperor, and was the second most powerful person in the empire.

The royal family oversaw the collection of goods, spiritual

festivals, and the worship of Inti. Power consolidated around the

cult of the Sun, and scholars suggest that the emperor Pachacuti

expanded this Sun cult to garner greater power in the 15th

century.

An illustrated representation of the Sun god Inti

This image of Inti appears at the center of Argentina’s modern-day flag.

Conquered provinces

were expected to dedicate a third of their resources, such as herds and crops, directly to the

worship of Inti. Each province also had a temple with male and

female priests worshipping the Inti cult. Becoming a priest was

considered one of the most honorable positions in society. Female

priests were called mamakuna,

or “the chosen women,” and they wove special cloth and brewed

chicha for religious festivals.

The main temple in the

Inca Empire, called Qurikancha, was built in Cusco. The temple housed

the bodies of deceased emperors and also contained a vast array of

physical representations of Inti, many of which were removed or destroyed when the Spanish arrived. Qurikancha was also the main site

of the religious festival Inti Raymi, which means “Sun Festival.”

It was considered the most important festival of the year, and is

still celebrated on the winter solstice in Cusco. It represents

the mythical origin of the Inca and the hope for good crops in the

coming year as the winter sun returns from darkness.

The festival of Inti Raymi

This festival is celebrated in late June in the capital of Cusco every year. Thousands of visitors arrive to see the procession and rituals.

Religious Expansion

Religious life was

centered in the Andes near Cusco, but as the Inca Empire expanded

its sphere of influence, they had to incorporate a wide array of

religious customs and traditions to avoid outright revolt. Ayllus, or family clans, often

worshipped very localized entities and gods. The ruling Inca often

incorporated these deities into the Inti cosmos. For example,

Pachamama, the Earth goddess, was a long-worshipped deity before the

Inca Empire. She was incorporated into Inca culture as a lower divine entity.

Similarly, the Chimú along the northern coast of Peru worshipped the Moon, rather than the Sun, probably due to the hot, arid climate and

their proximity to the ocean. The Inca also incorporated the Moon

into their religious myths and practices in the form of Mama Killa.

Sacrifice and the

Afterlife

The

Inca believed in reincarnation. Death was a passage to the next world that was full of difficulties. The spirit of the

dead, camaquen, would

need to follow a long dark road. The trip required the assistance of a

black dog that was able to see in the dark. Most Incas

imagined the after world to be very similar to the Euro-American

notion of heaven, with flower-covered fields and snow-capped

mountains. It was important for the Inca to ensure they did not die

as a result of burning or that the body of the deceased did not

become incinerated. This is because of the underlying belief that a

vital force would disappear and this would threaten their passage to the after

world. Those who obeyed the Inca moral code (do not steal, do not

lie, do not be lazy) went to live in the “Sun’s warmth”

while others spent their eternal days “in the cold earth.”

Skull showing signs of artificial cranial deformation

Although this skull predates the Inca Empire, and is from the Nazca culture, Inca elites would reshape infants’ skulls in a similar manner to illustrate a higher class status.

Human

sacrifice has been exaggerated by myth, but it did play a role in Inca religious practices. As many as 4,000 servants, court officials,

favorites, and concubines were killed upon the death of the Inca

Huayna Capac in 1527, for example. The Incas also performed child

sacrifices during or after important events, such as the death of the

Sapa Inca or during a famine. These sacrifices were known

as capacocha.

The Inca also

practiced cranial deformation. They achieved this by wrapping tight

cloth straps around the heads of newborns in order to alter the shape

of their soft skulls into a more conical form; this cranial

deformation distinguished social classes of the

communities, with only the nobility having it.

16.2.4: The Spanish Conquest

The Inca Empire already faced instability due to the Inca Civil War, European diseases, and internal revolt when explorer Francisco Pizarro began the conquest of Inca territory.

Learning Objective

Learn about the contributing factors that allowed the Spanish explorers to overpower the Inca Empire and establish control of the region

Key Points

- The Inca War of Succession began after the emperor Huayna Capac died around 1528 and his two sons both wanted to seize power.

- Internal instability allowed Francisco Pizarro and his men to find allies within the Inca Empire.

- Spanish forces ousted the last Inca holdout of Vilcabamba in 1572 and enforced a harsh rule of law on the local population.

Key Terms

- mita

-

A form of labor tax that required one person from each family to work in the mines. The Spanish enforced this heavy labor tax once they gained control of the region.

- Viceroyalty of Peru

-

The Spanish forces gave the newly seized Inca region this title and started to collect taxes and labor from the local people.

- Inca Civil War

-

This internal dispute started around 1528 between two sons of the deceased emperor who both wanted control, causing instability in the Inca Empire.

Spanish Arrival

The Spanish explorer Francisco Pizarro,

along with a small military retinue, landed on

South American soil around 1526. The Spanish recognized the wealth and

abundance that could be had in this territory; at this point the Inca Empire

was at its largest, measuring around 690,000 square miles. In 1528 Pizarro went back to Spain to ask for the official blessing of the Spanish

crown to the conquer the area and become governor. He returned with

his blessings around 1529 and began the official takeover of the

region.

Inca Civil War

Although Pizarro had a small force

behind him, many problems within the Inca Empire worked to his

advantage between 1528 and 1533. Foremost

among these was the Inca Civil War, which is also known as the War

of Succession or the War of Two Brothers. It began to brew just

one year after Pizarro first landed in the region. Around 1528, the

ruling Inca emperor, Huayna

Capac, and his designated heir, Ninan Cuyochic, died of disease. It

was most likely smallpox, which had quickly traveled down to South

America after the arrival of Spanish explorers in Central America.

Brothers Huascar and Atahualpa, two sons of the emperor Huayna Capac, both wanted to rule after their father’s death.

Inca Emperor Atahualpa

Although Atahualpa successfully won the Inca Civil War and ruled as emperor, he was soon captured by the Spanish and killed in 1533.

Initially, Huascar captured the throne

in Cusco, claiming legitimacy. However, Atahualpa had a keen military

mind and close relations with the military generals at the time, and

proved to be the deadlier force. Between 1529 and 1532 the two

brothers’ armies waged warfare, with one or the other gaining a

stronger foothold for a time. Atahualpa initially garnered favor with

northern allies and built a new capital for his forces in Quito. By

1532, Atahualpa had overpowered his brother’s forces via intrigue

and merciless violence, scaring many local populations away from standing up to his

power. This civil war left the population in a precarious position by

the time it ended.

Spanish Colonization

Around the same time that Atahualpa seized

the throne in 1532, Pizarro returned to Peru with blessings from the

Spanish crown. The Spanish forces went to meet with Atahualpa and

demanded he take up the “true faith” (Catholicism) and the yoke of

Charles I of Spain. Because of the language barrier, the Inca rulers probably did not understand much

of these demands, and the meeting quickly escalated to the Battle of

Cajamarca. This clash left thousands of native people dead. The Spanish also captured Atahualpa and kept him hostage,

demanding ransoms of silver and gold. They also insisted that

Atahualpa agree to be baptized. Although the Inca ruler was mostly

cooperative in captivity, and was finally baptized, the Spanish killed him on August 29, 1533,

essentially ending the potential for larger Inca attacks on Spanish

forces.

An engraved representation of the Battle of Cajamarca

This battle began in 1532, leaving thousands of native people dead and ending with the capture of Atahualpa.

Even though the Inca Civl War made

it easier for the Spanish armies to gain control initially, many

other contributing factors brought about the demise of Inca rule and

the crumbling of local populations. As scholar Jared Diamond points

out, the Inca Empire was already facing threats:

- Local unrest in the provinces after

years of paying tribute to the Inca elite created immediate allies

for the Spanish against the Inca rulers. - Demanding terrain throughout the empire

made it even more difficult to keep a handle on populations and goods

as the empire expanded. - Diseases that the population had

never been exposed to, such as smallpox, diphtheria, typhus, measles,

and influenza, devastated large swaths of the population within fifty years. - Superior Spanish military gear, including

armor, horses, and weapons, overpowered the siege warfare more common

in the Inca Empire.

The Last Incas

After Atahualpa died and the

Spanish seized control, they placed Atahualpa’s brother Manco Inca

Yupanqui in charge of Cusco as a puppet ruler while they tried to

reign in the north. After a failed attempt to recapture the city from

greater Spanish rule during this time, Manco retreated to Vilcabamba

and built the last stronghold of the Inca. The Inca continued to

revolt against totalitarian Spanish rule until the year 1572. In that

year the Spanish conquered Vilcabamba and killed the last Inca

emperor, Tupac Amaru, after a summary trial.

An image of the Spanish executing Tupac Amaru

The last Inca ruler, Tupac Amaru, was killed by Spanish forces in 1572, effectively ending any potential for an Inca uprising.

Spanish Rule

The Spanish named this vast region the

Viceroyalty of Peru and set up a Spanish system of rule, which

effectively suppressed any type of uprising from local communities.

The Spanish system destroyed many of

the Inca traditions and ways of life in a matter of years. Their

finely honed agricultural system, which utilized tiered fields in the

mountains, was completely disbanded. The Spanish also enforced heavy

manual labor taxes, called mita, on the local populations. In

general, this meant that every family had to offer up one person to

work in the highly dangerous gold and silver mines. If that family

member died, which was common, the family had to replace the fallen

laborer. The Spanish also enforced heavy taxes on agriculture, metals, and

other fine goods. The population continued to suffer heavy

losses due to disease as Spanish rule settled into place.

16.3: Early Civilizations of Mexico and Mesoamerica

16.3.1: The Olmec

The Olmec were the first major civilization in Mexico, lasting from approximately 1500—400 BCE.

Learning Objective

Give an account of the society, trade, art, and religion of the Olmec

Key Points

- The Olmec lived in south-central Mexico, with their center in La Venta in Tabasco.

- Little is known about Olmec religion, though scholars believe there were eight main deities.

- People lived in small agricultural villages outside of urban centers, which were mainly for ceremonial use.

- The decline of the Olmec population from 400—350 BCE may have been due to environmental changes.

Key Terms

- La Venta

-

The main city of the Olmec civilization.

- Mesoamerican ballgame

-

An ancient ritual sport that involved keeping a rubber ball in play in designated courts. It most likely originated in the Olmec culture.

- Olmec colossal heads

-

Basalt sculptures of human faces wearing large helmeted headdresses that stand up to 3.4 meters high. These sculptures most likely represent important rulers.

The Olmec were the first major civilization in Mexico. They lived in the tropical lowlands of south-central Mexico, in the present-day states of Veracruz and Tabasco, and had their center in the city of La Venta.

The Olmec flourished during Mesoamerica’s formative period, dating roughly from as early as 1500 BCE to about 400 BCE. Pre-Olmec cultures had flourished in the area since about 2500 BCE, but by 1600–1500 BCE, Early Olmec culture had emerged. They were the first Mesoamerican civilization and laid many of the foundations for the civilizations that followed, such as the Maya. Judging from the available archeological evidence it is likely that they originated the Mesoamerican ballgame and possible that they practiced ritual bloodletting.

The Gulf of Mexico’s lowlands are generally considered the birthplace of the Olmec culture, and remained the heartland of this civilization during its existence. This area is characterized by swampy lowlands punctuated by low hills, ridges, and volcanoes. The Tuxtlas Mountains rise sharply in the north, along the Gulf of Mexico’s Bay of Campeche. Here the Olmec constructed permanent city-temple complexes at San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, La Venta, Tres Zapotes, and Laguna de los Cerros. San Lorenzo remained the Olmec capital up until about 900 BCE, when the central city became La Venta, which remained functional until the demise of the Olmec around 400 BCE. Possible river or weather changes caused this movement to occur.

Trade and Village Life

There are no written records of Olmec commerce, beliefs, or customs, but from the archeological evidence it appears they were not economically confined. In fact, Olmec artifacts have been found across Mesoamerica, indicating that there were extensive interregional trade routes. The Olmec period saw a significant increase in the length of trade routes, the variety of goods, and the sources of traded items.

Trading helped the Olmec build their urban centers of San Lorenzo and La Venta. However, these cities were used predominantly for ceremonial purposes and elite activity; most people lived in small villages. Individual homes had a lean-to and a storage pit nearby. They also likely had gardens, in which the Olmec would grow medicinal herbs and small crops, like sunflowers.

The Great Pyramid in La Venta, Tabasco

Remains of the last capital of the Olmec society, La Venta, include this religious site where elites most likely performed rituals.

Most agriculture took place outside of the villages in fields cleared using slash-and-burn techniques. The Olmec likely grew crops such as:

- Maize

- Beans

- Squash

- Manioc

- Sweet potatoes

- Cotton

Religion

Unfortunately, there is no surviving direct account of Olmec beliefs, but their notable artwork provide clues about their life and religion.

Olmec king

Surviving art, like this relief of a king or chief found in La Venta, help provide clues about how Olmec society functioned.

There were eight different androgynous Olmec deities, each with its own distinct characteristics. For example, the Bird Monster was depicted as a harpy eagle associated with rulership. The Olmec Dragon was shown with flame eyebrows, a bulbous nose, and bifurcated tongue. These gods were believed to provide the rulers a mandate to lead. Deities often represented a natural element and included:

- The Maize deity

- The Rain Spirit or Were-Jaguar

- The Fish or Shark Monster

Religious activities regarding these deities probably included the elite rulers, shamans, and possibly a priest class making offerings at religious sites in La Venta and San Lorenzo.

Art

The Olmec culture was defined and unified by a specific art style, and this continues to be the hallmark of the culture. Wrought in a large number of media—jade, clay, basalt, and greenstone, among others—much Olmec art, such as The Wrestler, is surprisingly naturalistic. Other art expresses fantastic anthropomorphic creatures, often highly stylized, using an iconography reflective of a religious meaning. Common motifs include downturned mouths and a cleft head, both of which are seen in representations of were-jaguars and the rain deity.

Olmec hollow baby figurine

Realistic ceramic objects, such as this portrayal of an infant, illustrate the highly skilled artistic style of the Olmec culture.

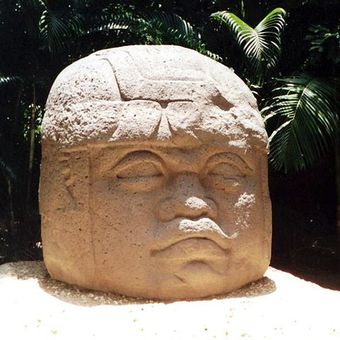

Olmec Colossal Heads

The most striking art left behind by this culture are the Olmec colossal heads. Seventeen monumental stone representations of human heads sculpted from large basalt boulders have been unearthed in the region to date. The heads date from at least before 900 BCE and are a distinctive feature of the Olmec civilization. All portray mature men with fleshy cheeks, flat noses, and slightly crossed eyes. However, none of the heads are alike, and each boasts a unique headdress, which suggests they represent specific individuals.

The boulders were brought from the Sierra de los Tuxtlas mountains of Veracruz. Given that the extremely large slabs of stone used in their production were transported over large distances, requiring a great deal of human effort and resources, it is thought that the monuments represent portraits of powerful individual Olmec rulers. The heads were variously arranged in lines or groups at major Olmec centers, but the method and logistics used to transport the stone to these sites remain uncertain.

The discovery of a colossal head at Tres Zapotes in the 19th century spurred the first archaeological investigations of Olmec culture by Matthew Stirling in 1938. Most colossal heads were sculpted from spherical boulders, but two from San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán were re-carved from massive stone thrones. An additional monument, at Takalik Abaj in Guatemala, is a throne that may have been carved from a colossal head. This is the only known example from outside the Olmec heartland.

Olmec head

This sculpture is typical of the colossal heads of the Olmec.

The End of the Olmecs

The Olmec population declined sharply between 400 and 350 BCE, though it is unclear why. Archaeologists speculate that the depopulation was caused by environmental changes, specifically riverine environment changes. These changes may have been triggered by the silting up of rivers due to agricultural practices.

Another theory for the considerable population drop relates to tectonic upheavals or subsidence, as suggested by Santley and colleagues who propose relocation of settlements due to volcanism, instead of extinction. Volcanic eruptions during the Early, Late, and Terminal Formative periods would have blanketed the lands and forced the Olmec to move their settlements.

16.3.2: The Mixtec

The Mixtec are a group who lived in modern-day Mexico before the Spanish conquest. People still identify as Mixtec today.

Learning Objective

Distinguish between the Mixtec people and the Mixtec language and identify when they were most prominent

Key Points

- The Mixtec survive today, but reached peak prominence in the 11th century CE.

- The Mixtec language is a set of up to fifty languages, and is not to be confused with the Mixtec people.

- The Mixtec are well known in the anthropological world for their codices, or phonetic pictures in which they wrote their history and genealogies.

Key Terms

- Mixtec

-

Indigenous Mesoamerican peoples inhabiting the region known as La Mixteca, which covers parts of the Mexican states of Oaxaca, Guerrero, and Puebla.

- Codices

-

Phonetic pictures painted on deerskin and folded into books, which recorded Mixtec history and genealogy.

- Tututepec

-

A prominent city center during the height of the Mixtec state, situated along the coast of modern-day Oaxaca.

The Mixtec are indigenous Mesoamerican peoples inhabiting the region known as La Mixteca, which covers parts of the Mexican states of Oaxaca, Guerrero, and Puebla. Though the Mixtec remain today, they were most prominent in the 11th century and the following years, until they were conquered by the Spanish and their allies in the 16th century.

Before the arrival of Spanish hostility, a number of Mixtecan city-states competed with each other and with the Zapotec kingdoms. The major Mixtec polity was Tututepec, which rose to prominence in the 11th century under the leadership of Eight Deer Jaguar Claw. This prominent leader was the only Mixtec king to ever unite the highland and lowland polities into a single Mixtec state. During this era there were approximately 1.5 million Mixtecs populating this varied region.

Modern Mixtec People

Today there are approximately 800,000 Mixtec people in Mexico, and there are also large populations in the United States. In recent years a large exodus of indigenous peoples from Oaxaca, such as the Zapotec and Triqui, have emerged as one of the most numerous groups of Amerindians in the United States. As of 2011, an estimated 150,000 Mixtec people were living in California, and 25,000 to 30,000 were living in New York City. Large Mixtec communities exist in the border cities of Tijuana; Baja California; San Diego, California; and Tucson, Arizona. Mixtec communities are generally described as trans-national or trans-border because of their ability to maintain and reaffirm social ties between their native homelands and diasporic communities.

Mixtec Language

The word “Mixtec” is often used to refer not to the group of people of Mixtec ancestry, but to the family of languages that have developed alongside the group. There is no longer one single Mixtec language; some estimate that there are fifty distinct languages in the Mixtec family, including Cuicatec and Triqui.

Mixtec’s area

The historical geographic area inhabited by the Mixtec, including the important polities, such as Tututepec.

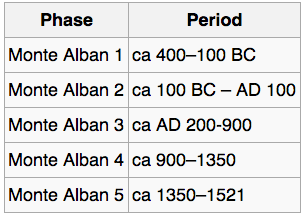

Mixtec History

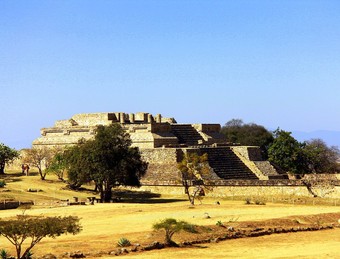

Important ancient centers of the Mixtec include the ancient capital of Tilantongo, as well as the sites of Achiutla, Cuilapan, and Yucuñudahui. The Mixtec also erected major constructions at the ancient city of Monte Albán, which had originated as a Zapotec city before the Mixtec gained control of it.

The west side platform at Monte Albán

This ancient city remained a religious site for centuries, and was more sparsely populated during the rise of smaller Mixtec polities. However, religious sites were often reused by Mixtec elites.

At the height of the Aztec Empire (between 1428 and 1521 CE) many Mixtec polities were forced to pay tribute. However, many Mixtec polities remained completely independent of the threatening empire, even as it expanded outward. The smaller Mixtec polities also put up resistance to Spanish forces led by Pedro de Alvarado until the invaders gained control of the region and destroyed any attempt at a revolt in 1521. Disease, weaponry, and local political fractures likely aided the Spanish takeover of the area.

Mixtex Art

The work of Mixtec artisans who produced work in stone, wood, and metal were well regarded throughout ancient Mesoamerica. Mixtec artists were known for their exceptional mastery of jewelry, in which gold and turquoise figured prominently. The intricate metalwork of Mixtec goldsmiths formed an important part of the tribute the Mixtecs had to pay to the Aztecs during parts of their history.

Mixtec funerary mask

Mixtec art included the use of turquoise, gold, and carved stones, and exemplified artistry before the arrival of the Spanish.

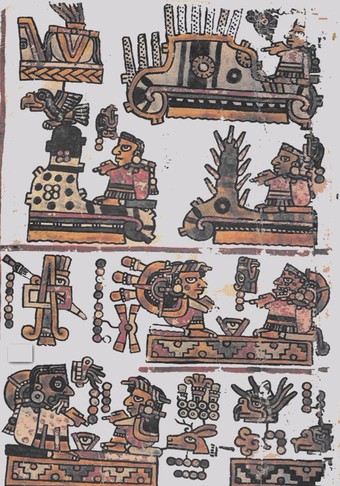

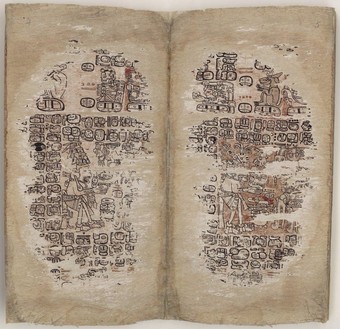

Codices

The Mixtec are well known in the anthropological world for their codices, or phonetic pictures, in which they wrote their history and genealogies in deerskin in the “fold-book” form. The best-known story of the Mixtec codices is that of Lord Eight Deer, named after the day on which he was born, whose personal name was Jaguar Claw, and whose epic history is related in several codices. He successfully conquered and united most of the Mixteca region.

A page from the Codex Bodley

This codex tells the story of the Tilantongo and Tiaxiaco dynasties.

Codices can be read from right to left and often measure many feet long. The Codex Bodley measures twenty-two feet long and contains complex explanations of important family lineages and creation stories, such as the War of Heaven, that directly refer back to elite dynasties. The preservation of these extremely rare Codices paints a distinct picture of Mesoamerica right before the arrival of Spanish forces.

16.3.3: Teotihuacan

Teotihuacan was a city founded outside of modern Mexico City in 100 BCE and was known for its pyramids.

Learning Objective

Discuss the diversity and notable archeological features of Teotihuacan

Key Points

- Teotihuacan was founded around 100 BCE and reached its peak population around 450 CE.

- Teotihuacan was a multi-ethnic city, with distinct quarters occupied by Otomi, Zapotec, Mixtec, Maya and Nahua peoples.

- The geographical layout of Teotihuacan is a good example of the Mesoamerican tradition of planning cities, settlements, and buildings as a reflections of their view of the Universe.

Key Terms

- Pyramid of the Sun

-

The largest building in Teotihuacan, which measures 246 feet high and 736 feet wide.

- Teotihuacan

-

A large precolumbian Mesoamerican city known for its archeological significance.

- The Great Goddess

-

This deity was one of the central icons of Teotihuacano religious culture. She appears in painted murals with images associated with the underworld, birth, death, and creation.

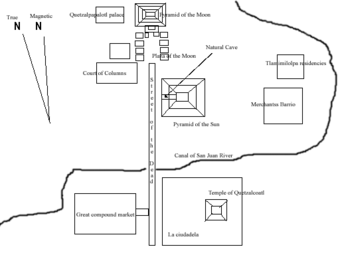

Just 30 miles from modern day Mexico City lies the precolumbian Mesoamerican city of Teotihuacan. It is famous for its pyramids and series of accompanying residential compounds, but was once much more than an archaeological and tourist site.

Archaeological evidence suggests that Teotihuacan was a multi-ethnic city, with distinct quarters occupied by Otomi, Totonac, Zapotec, Mixtec, Maya, and Nahua peoples. In 2001, Terrence Kaufman presented linguistic evidence suggesting that an important ethnic group in Teotihuacan was of Totonacan or Mixe–Zoquean linguistic affiliation. Other scholars maintain that the largest population group must have been of Otomi ethnicity, because the Otomi language is known to have been spoken in the area around Teotihuacan both before and after the classic period and not during the middle period.

Although it is a subject of debate whether Teotihuacan was the center of a state empire, its influence throughout Mesoamerica is well documented; evidence of Teotihuacano presence can be seen at numerous sites in Veracruz and the Maya region. Many Maya murals represent Teotihucuan and the leaders of the city during its zenith. The Aztecs were also heavily influenced by the architecture, culture, and lore of this ancient city, claiming common ancestry with the Teotihuacanos and adopting some of their artistic and architectural styles.

Founding of the City

The city and culture, which can be referred to as Teotihuacan or Teotihuacano, is thought to have been established around 100 BCE, with major monuments continuously under construction until about 250 CE. It began as a new religious center in the Mexican Highland and a large population was drawn to the city over a few centuries. It may have lasted until sometime between the 7th and 8th centuries CE, but its major monuments were sacked and systematically burned around 550 CE. At its zenith, around the first half of the first millennium CE, Teotihuacan was the largest city in the pre-Columbian Americas, with a population estimated at 125,000 or more. It’s varied population made it, at minimum, the sixth largest city in the world during its epoch. The city eventually included multi-floor apartment compounds built to accommodate this large population.

Mysterious Founders and Religion

The founders of this religious and populous city remain a mystery to scholars of the area. Some have speculated that the Xitle volcano, which is located southwest of modern-day Mexico City, may have prompted a mass emigration out of the central valley and into the Teotihuacan valley. These displaced settlers may have founded, or at least helped grow, the city.

An alternate explanation is that the Totonac people, who still remain today, founded Teotihuacan. There is also evidence that at least some of the people living in Teotihuacan immigrated from those areas influenced by the Teotihuacano civilization, including the Zapotec, Mixtec, and Maya peoples.

Mural of the Great Goddess of Teotihuacan

This powerful goddess was associated with darkness, mystery, death, and creation. She was often depicted with owls, jaguars, and spiders, all creatures of the earth, darkness and the underworld. This mural is from the Tetitla compound at Teotihuacan.

As a religious center, Teotihuacan displayed its most prominent gods and goddesses in murals and architecture. The Great Goddess of Teotihuacan appears to be the most prominent of these deities, and she likely represented the underworld, war, creation, water, and the earth. Evidence of human sacrifices to honor the completion of buildings or special times of year has also been uncovered by archeologists. Captives from wars were decapitated, had their hearts removed, were bludgeoned, or were buried alive to commemorate these momentous occasions.

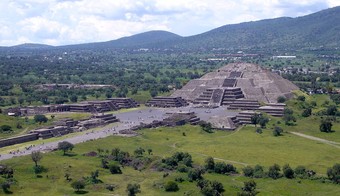

Pyramid of the Sun

This giant pyramid dwarfs the smaller platforms surrounding it and was the largest building at Teotihuacan.

Layout

The city’s broad central avenue, called “Avenue of the Dead” (a translation from its Nahuatl name Miccoatli), is flanked by impressive ceremonial architecture, including the immense Pyramid of the Sun (third largest in the World after the Great Pyramid of Cholula and the Great Pyramid of Giza) and the Pyramid of the Moon. Along the Avenue of the Dead are many smaller talud-tablero platforms. The Aztecs believed they were tombs, inspiring the Nahuatl name of the avenue.

Pyramid of the Moon

This pyramid is the second largest in Teotihuacan.

Further down the Avenue of the Dead is the area known as the Citadel, containing the ruined Temple of the Feathered Serpent. This area was a large plaza surrounded by temples that formed the religious and political center of the city. Most of the common people lived in large apartment buildings spread across the city. Many of the buildings contained workshops where artisans produced pottery and other goods.