12.1: The Princes of Rus

12.1.1: Rurik and the Foundation of Rus’

Rurik was a Varangian chieftain who established the first ruling dynasty in Russian history called the Rurik Dynasty in 862 near Novgorod. This dynasty went on to to establish Kievan Rus’.

Learning Objective

Understand the key aspects of Rurik’s rise to power and the establishment of Kievan Rus’

Key Points

- Rurik and his followers likely originated in Scandinavia and were related to Norse Vikings.

- The Primary Chronicle is one of the few written documents available that tells us how Rurik came to power.

- Local leaders most likely invited Rurik to establish order in the Ladoga region around 862, beginning a powerful legacy of Varangian leaders.

- The capital of Kievan Rus’ moved from Novgorod to Kiev after Rurik’s successor, Oleg, captured this southern city.

Key Terms

- Primary Chronicle

-

A text written in the 12th century that relates a detailed history of Rurik’s rise to power.

- Varangians

-

Norse Vikings who established trade routes throughout Eurasia and eventually established a powerful dynasty in Russia.

- Rurik Dynasty

-

The founders of Kievan Rus’ who stayed in power until 1598 and established the first incarnation of a unified Russia.

Rurik

Rurik

(also spelled Riurik) was a Varangian chieftain who arrived in the

Ladoga region in modern-day Russia in 862. He built the Holmgard

settlement near Novgorod in the 860s and founded the first

significant dynasty in Russian history called the Rurik Dynasty.

Rurik and his heirs also established a significant geographical and

political formation known as Kievan Rus’, the first incarnation of

modern Russia. The Rurik rulers continued to rule Russia into the

16th century and the mythology surrounding the man Rurik is often

referred to as the official beginning of Russian history.

Primary

Chronicle

The

identity of the mythic leader Rurik remains obscure and unknown. His

original birthplace, family history, and titles are shrouded in

mystery with very few historical clues. Some 19th-century scholars

attempted to identify him as Rorik of Dorestad (a Viking-Age trading

outpost situated in the northern part of modern-day Germany).

However, no concrete evidence exists to confirm this particular

origin story.

A page from the Primary Chronicle or The Tale of Bygone Years

This rare written document was created in the 12th century and provides the most promising clues as to the arrival of Rurik in Ladoga.

The

debate also continues as to how Rurik came to control the Novgorod

region. However, some clues are available from the Primary Chronicle. This document is also known as The

Tale of Bygone Years

and was compiled in Kiev around 1113 by the monk Nestor. It relates

the history of Kievan Rus’ from 850 to 1110 with various updates and

edits made throughout the 12th century by scholarly monks. It is

difficult to untangle legend from fact, but this document provides the most promising clues regarding Rurik. The Primary Chronicle contends

the Varangians were a Viking group, most likely from Sweden or

northern Germany, who controlled trade routes across northern Russia

and tied together various cultures across Eurasia.

A monument celebrating the millennial anniversary of the arrival of Rurik in Russia

This modern interpretation of Rurik illustrates his powerful place in Russian history and lore.

The

various tribal groups, including Chuds, Eastern Slavs, Merias, Veses,

and Krivichs, along the northern trade routes near Novgorod often

cooperated with the Varangian Rus’ leaders. But in the late 850s they rose up in

rebellion, according to the Primary Chronicle.

However, soon after this rebellion, the local tribes near the

Novgorod region began to experience internal disorder and conflict. These

events prompted local tribal leaders to invite Rurik and his

Varangian leaders back to the region in 862 to reinstate peace and

order. This moment in history is known as the Invitation

of the Varangians

and is commonly regarded as the starting point of official Russian

history.

Development

of Kievan Rus’

According

to legend, at the call of the local tribal leaders Rurik, along with his

brothers Truvor and Sineus, founded the Holmgard settlement in Ladoga. This

settlement is supposed to be at the site of modern-day Novgorod. However, newer

archeological evidence suggests that Novgorod was not regularly

settled until the 10th century, leading some to speculate that

Holmgard refers to a smaller settlement just southeast of the city.

The founding of Holmgard signaled a new era in Russian history and

the three brothers became the famous founders of the first Rus’

ruling dynasty.

Kievan Rus’ in 1015

The expansion and shifting borders of Kievan Rus’ become apparent when looking at this map, which includes the two centers of power in Novgorod and Kiev.

Rurik

died in 879 and his successor, Oleg, continued the Varangian Rus’

expansion in 882 by taking the southern city of Kiev from the Khasars

and establishing the medieval state of Kievan Rus’. The capital

officially moved to Kiev at this point. With this shift in power,

there were two distinct capitals in Kievan Rus’, the northern seat of

Novgorod and the southern center in Kiev. In Kievan Rus’ tradition,

the heir apparent would oversee the northern site of Novgorod while

the ruling Rus’ king stayed in Kiev. Over the next 100 years local

tribes consolidated and unified under the Rurik Dynasty, although

local fractures and cultural differences continued to play a

significant role in the attempt to maintain order under Varangian rule.

12.1.2: Vladimir I and Christianization

Vladimir I ruled from 980 to 1015 and was the first Kievan Rus’ ruler to officially establish Orthodox Christianity as the new religion of the region.

Learning Objective

Outline the shift from pagan culture to Orthodox Christianity under the rule of Vladimir I

Key Points

- Vladimir I became the ruler of Kievan Rus’ after overthrowing his brother Yaropolk in 978.

- Vladimir I formed an alliance with Basil II of the Byzantine Empire and married his sister Anna in 988.

- After his marriage Vladimir I officially changed the state religion to Orthodox Christianity and destroyed pagan temples and icons.

- He built the first stone church in Kiev in 989, called the Church of the Tithes.

Key Terms

- Constantinople

-

The capital of the Byzantine Empire.

- Perun

-

The pagan thunder god that many locals, and possibly Vladimir I, worshipped before Christianization.

- Basil II

-

The Byzantine emperor who encouraged Vladimir to convert to Christianity and offered a political marriage alliance with his sister, Anna.

Vladimir I

Vladimir

I, also known as Vladimir the Great or Vladimir Sviatoslavich the

Great, ruled Kievan Rus’ from 980 to 1015 and is famous for

Christianizing this territory during his reign. Before he gained the

throne in 980, he had been the Prince of Novgorod while his father,

Sviatoslav of the Rurik Dynasty, ruled over Kiev. During his rule as

the Prince of Novgorod in the 970s, and by the time Vladimir claimed

power after his father’s death, he had consolidated power between

modern-day Ukraine and the Baltic Sea. He also successfully bolstered

his frontiers against incursions from Bulgarian, Baltic, and Eastern

nomads during his reign.

Early

Myths of Christianization

The

original Rus’ territory was comprised of hundreds of small towns and

regions, each with its own beliefs and religious practices. Many of

these practices were based on pagan and localized traditions. The

first mention of any attempts to bring Christianity to Rus’ appears

around 860. The Byzantine Patriarch Photius penned a letter in the year 867 that described the Rus’ region right after the Rus’-Byzantine War

of 860. According to Photius, the people of the region appeared

enthusiastic about the new religion and he claims to have sent a

bishop to convert the population. However, this low-ranking official

did not successfully convert the population of Rus’ and it would take

another twenty years before a significant change in religious

practices would come about.

The

stories regarding these first Byzantine missions to Rus’ during the

860s vary greatly and there is no official record to substantiate the

claims of the Byzantine patriarchs. Any local people in small

villages who embraced Christian practices would have had to contend with

fears of change from their neighbors.

Vladimir

I and His Rise to Power

The

major player in the Christianization of the Rus’ world is

traditionally considered Vladimir I. He was born in 958, the youngest

of three sons, to the Rus’ king Sviatoslav. He ascended to the

position of Prince of Novgorod around 969 while his oldest brother,

Yaropolk, became the designated heir to the throne in Kiev. Sviatoslav

died in 972, leaving behind a fragile political scene among his three

sons. Vladimir was forced to flee to Scandinavia in 976 after

Yaropolk murdered their brother Oleg and violently took control of

Rus’.

Vladimir I

A Christian representation of Vladimir I, who was the first Rus’ leader to officially bring Christianity to the region.

Vladimir

fled to his kinsman Haakon Sigurdsson, who ruled Norway at the time.

Together they gathered an army with the intent to regain control of

Rus’ and establish Vladimir as the ruler. In 978, Vladimir returned

to Kievan Rus’ and successfully recaptured the territory. He also

slew his brother Yaropolk in Kiev in the name of treason and, in

turn, became the ruler of all of Kievan Rus’.

Constantinople

and Conversion

Vladimir

spent the next decade expanding his holdings, bolstering his military

might, and establishing stronger borders against outside invasions.

He also remained a practicing pagan during these first years of his

rule. He continued to build shrines to pagan gods, traveled with

multiple wives and concubines, and most likely continued to promote the worship of the thunder god Perun. However, the Primary Chronicle (one

of the few written documents about this time) states that in 987

Vladimir decided to send envoys to investigate the various religions

neighboring Kievan Rus’.

According

to the limited documentation from the time, the envoys that came back

from Constantinople reported that the festivities and the presence of

God in the Christian Orthodox faith were more beautiful than anything

they had ever seen, convincing Vladimir of his future religion.

Another

version of events claims that Basil II of Byzantine needed a military

and political ally in the face of a local uprising near

Constantinople. In this version of the story, Vladimir demanded a

royal marriage in return for his military help. He also announced he

would Christianize Kievan Rus’ if he was offered a desirable marriage

tie. In either version of events, Vladimir vied for the hand of Anna,

the sister of the ruling Byzantine emperor, Basil II. In order to

marry her he was baptized in the Orthodox faith with the name Basil,

a nod to his future brother-in-law.

17th-century Church of the Tithes

The original stone Church of the Tithes collapsed from fire and sacking in the 12th century. However, two later versions were erected and destroyed in the 17th and 19th centuries.

He

returned to Kiev with his bride in 988 and proceeded to destroy all

pagan temples and monuments. He also built the first stone church in

Kiev named the Church of the Tithes starting in 989. These moves confirmed a

deep political alliance between the Byzantine Empire and Rus’ for years to come.

Baptism

of Kiev

On

his return in 988, Vladimir baptized his twelve sons and many boyars

in official recognition of the new faith. He also sent out a message

to all residents of Kiev, both rich and poor, to appear at the

Dnieper River the following day. The next day the residents

of Kiev who appeared were baptized in the river while Orthodox

priests prayed. This event became known as the Baptism of Kiev.

Monument of Saint Vladimir in Kiev

This statue sits close to the site of the original Baptism of Kiev.

Pagan

uprisings continued throughout Kievan Rus’ for at least another

century. Many local populations violently rejected the new religion

and a particularly brutal uprising occurred in Novgorod in 1071.

However, Vladimir became a symbol of the Russian Orthodox religion, and when he died in 1015 his body parts were distributed throughout

the country to serve as holy relics.

12.1.3: Yaroslav the Wise

Yaroslav I, also known as Yaroslav the Wise, developed the first legal codes, beautified Kievan Rus’, and formed major political alliances with the West during his nearly 40-year reign.

Learning Objective

Outline the key elements of Yaroslav the Wise’s reign and cultural influence

Key Points

- Yaroslav I came to power after a bloody civil war between brothers.

- He captured the Kievan throne because of the devotion of the Novgorodian and Varangian troops to his cause.

- Grand Prince Yaroslav was the first Kievan ruler to codify legal customs into the Pravda Yaroslava.

- He bolstered borders and encouraged political alliances with other major European powers during his reign.

Key Terms

- primogeniture

-

A policy that designates the oldest son as the heir to the throne upon the death of the father.

- Novgorod Republic

-

The northern stronghold of Kievan Rus’ where Yaroslav gained early support for his cause.

Yaroslav the Wise

Yaroslav

the Wise was the Grand Prince of Kiev from 1016 until his death in

1954. He was also vice-regent of Novgorod from 1010 to 1015 before

his father, Vladimir the Great, died. During his reign he was known

for spreading Christianity to the people of Rus’, founding the first

monasteries in the country, encouraging foreign alliances, and translating Greek texts in Church Slavonic. He also created some of the

first legal codes in Kievan Rus’. These accomplishments during his

lengthy rule granted him the title of Yaroslav the Wise in early

chronicles of his life, and his legacy endures in both political and

religious Russian history.

Youth

and Rise to Power

Yaroslav

was the son of the Varangian Grand Prince Vladimir the Great and most

likely his second son with Rogneda of Polotsk. His youth remains

shrouded in mystery. Evidence from the Primary Chronicle and

examination of his skeleton suggests he is one of the youngest sons

of Vladimir, and possibly a son from a different mother. He was most

likely born around the year 978.

Facial reconstruction of Yaroslav I by Mikhail Gerasimov

He

was set as vice-regent of Novgorod in 1010, as befitted a senior heir

to the throne. In this same time period Vladimir the Great granted

the Kievan throne to his younger son, Boris. Relations were strained

in this family. Yaroslav refused to pay Novgorodian tribute to Kiev

in 1014, and only Vladimir’s death in 1015 prevented a severe war

between these two regions. However, the

next few years were spent in a bitter civil war between the brothers.

Yarsolav was vying for the seat in Kiev against his brother

Sviatopolk I, who was supported by Duke Boleslaw I of Chrobry. In the

ensuing years of carnage, three of his brothers were murdered (Boris,

Gleb, and Svyatoslav). Yaroslav won the first battle at Kiev against

Sviatopolk in 1016 and Sviatopolk was forced to flee to

Poland.

After

this significant triumph Yaroslav’s ascent to greatness began, and he

granted freedoms and privileges to the Novgorod Republic, who had

helped him gain the Kievan throne. These first steps also most likely

led to the first legal code in Kievan Rus’ under Yaroslav. He was

chronicled as Yaroslav the Wise in retellings of these events because

of his even-handed dealing with the wars, but it is highly possible

he was involved in the murder of his brothers and other gruesome acts of war.

Wise

Reign

The

civil war did not completely end in 1016. Sviatopolk returned in 1018

and retook Kiev. However, Varangian and Novgorodian troops recaptured

the capital and Sviatopolk fled to the West never to return. Another

fraternal conflict arose in 1024 when another brother of Yaroslav’s,

Mstislav of Chernigov, attempted to capture Kiev. After this conflict, the brothers split the Kievan Rus’ holdings, with Mstislav ruling

over the region left of the Dnieper River.

Yaroslav

the Wise was instrumental in defending borders and expanding the

holdings of Kievan Rus’. He protected the southern borders from

nomadic tribes, such as the Pechenegs, by constructing a line of

military forts. He also successfully laid claim to Chersonesus in the

Crimea and came to a peaceful agreement with the Byzantine Empire

after many years of conflict and disagreements over land holdings.

Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kiev

This iconic cathedral fell into disrepair and was almost destroyed during the Soviet era, but it was saved and restored to its former glory.

Yaroslav

the Wise garnered his thoughtful reputation due to his prolific years

in power. He was a ruler that loved literature, religion, and the

written language. His many accomplishments included:

-

Building the Saint Sophia Cathedral and the first monasteries in Russia, named

Saint George and Saint Irene. -

Founding a library and a school at the Saint Sophia Cathedral and

encouraging the translation of Greek texts into Church Slavonic. -

Developing a more established hierarchy within the Russian Orthodox

Church, including a statute outlining the rights of the clergy and

establishing the sobor of bishops. - Beautifying Kiev with elements of design taken from the Byzantine

Empire, including the Golden Gate of Kiev. - Compiling the first book of laws in Kievan Rus’, called the Pravda

Yaroslava. This first compilation set down clear laws that reflected

the feudal landscape of the 11th century. This initial legal code

would live on and be refined into the Russkaya Pravda in the 12th

century. -

Establishing primogeniture, which meant that his eldest son would

succeed him as Grand Prince over Novgorod and Kiev, hoping that

future conflict between his children would be avoided.

Golden Gate of Kiev in 2016

This important monument was one of the great architectural accomplishments created under Yaroslav the Wise, and now features a monument to the ruler, seen in the foreground.

Family

and Death

Yaroslav

married Ingegerd Olofsdotter, the daughter of the king of Sweden, in

1019. He had many sons and encouraged them to remain on good terms,

after all the years of warfare and bloodshed with his own brothers.

He also married three of his daughters to European royalty.

Elizabeth, Anna, and Anastasia married Harald III of

Norway, Henry I of France, and Andrew I of Hungary respectively. These marriages

forged powerful alliances with European states.

Daughters of Yaroslav the Wise

This 11th-century fresco in Saint Sophia’s Cathedral shows four of Yaroslav’s daughter, probably Anne, Anastasia, Elizabeth, and Agatha.

The

Grand Prince Yaroslav I died in 1054 and was buried in Saint Sophia’s

Cathedral. His expansion of culture and military might, along with

his unification of Kievan Rus’, left a powerful impression on Russian

history. Many towns and monuments remain dedicated to this leader.

12.1.4: The Mongol Threat

The Mongol Empire expanded its holdings in the 13th century and established its rule over most of the major Kievan Rus’ principalities after brutal military invasions over the course of many years.

Learning Objective

Describe the attacks by th Mongols on the Russian principality

Key Points

- The major principalities of Kievan Rus’ became increasingly fractured and independent after the death of Yaroslav the Wise in 1054.

- The first Mongol attempt to capture Kievan territories occurred in 1223 at the Battle of the Kalka River.

- The Mongol forces began a heavy military campaign on Kievan Rus’ in 1237 under the rule of Batu Khan.

- Kiev was sacked and taken in 1240, starting a long era of Mongol rule in the region.

Key Terms

- Tatar yoke

-

The name given to the years of Mongol rule in Kievan Rus’, which meant heavy taxation and the possibility of local invasions at any time.

- Golden Horde

-

The western section of the Mongol Empire that included Kievan Rus’ and parts of Eastern Europe.

- Sarai

-

The new capital of the Mongol Empire in the southern part of Kievan Rus’.

Mongol Invasion

The Mongol invasion of the Kievan Rus’

principalities began in 1223 at the Battle of the Kalka River.

However, the Mongol armies ended up focusing their military might on

other regions after this bloody meeting, only to return in 1237. For

the next three years the Mongol forces took over the major princely

cities of Kievan Rus’ and finally forced most principalities to

submit to foreign rule and taxation. Rus’ became part of what is

known as the Golden Horde, the western extension of the Mongol

Empire located in the eastern Slavic region. Some of the new taxes and rules of law lasted until 1480 and

had a lasting impact on the shape and character of modern Russia.

Fragmented Kievan Rus’

After the end of the unifying reign of

Yaroslav the Wise, Kievan Rus’ became fragmented and power was focused

on smaller polities. The great ruler’s death in 1054 brought about

major power struggles between his sons and princes in outlying

provinces. By the 12th century, after years of fighting amongst the princes,

power was centered around smaller principalities. This unsettled

trend left Kievan Rus’ much more fragmented. Power was

passed down to the eldest in the local ruling dynasty and cities were

responsible for their own defenses. The Byzantine Empire was also

facing major upheaval, which meant a central Russian ally and trading

partner was weakened, which, in turn, weakened the strength and wealth of Kievan

Rus’.

The principalities of Kievan Rus’ at its height, 1054-1132

The princely regions were relatively unified into the 12th century but slowly separated and became more localized as fights over regions and power among the nobility continued.

Mongol Invasion

The already fragile alliances between

the smaller Rus’ principalities faced further tension when the

nomadic invaders, the Mongols, arrived on the scene during this

fractured era. These invaders originated on the steppes of central

Asia and were unified under the infamous warrior and leader Genghis

Khan. The Mongols began to expand their power across the continent.

The Battle of the Kalka River in 1223 initiated the first attempt of

the Mongol forces to capture Kievan Rus’. It was a bloody battle

that ended with the execution of Mstislav of Kiev executed the Kievan forces

greatly weakened. The Mongols were superior in their military tactics

and stretched the Rus’ forces considerably, however after executing

the Kievan prince, the forces went back to Asia to rejoin Genghis

Khan. However, the Mongol threat was far from over, and they returned

in 1237.

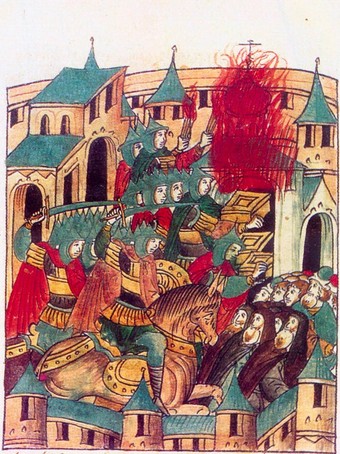

The Sacking of Suzdal in 1238 by Batu Khan

This 16th-century depiction of the Mongol invasion highlights the bloodshed and military might of the invaders.

Over the course of the years 1237 and

1238, the Mongol leader, Batu Khan, led his 35,000 mounted archers to

burn down Moscow and Kolomna. Then he split his army into smaller

units that tackled the princely polities one at a time. Only Novgorod

and Pskov were spared major destruction during this time. Refugees

from the southern principalities, where destruction was widespread

and devastating, were forced to flee to the harsh northern forests,

where good soil and resources were scarce. The final victory for Batu

Khan came in December 1240 when he stormed the great capital of Kiev

and prevailed.

Tatar Rule and the Golden Horde

The Mongols, also known as the Tatars,

built their new capital, Sarai, in the south along the Volga River.

All the major principalities, such as Novgorod, Smolensk, and Pskov,

submitted to Mongol rule. The age of this economic and cultural rule

is often called the Tatar yoke, but over the course of 200 years, it

was a relatively peaceful rule. The Tatars followed in the footsteps

of Genghis Khan and refrained from settling the entire region or

forcing local populations to adopt specific religious or cultural

traditions. However, Rus’ principalities paid tribute and taxes to

the Mongol rulers regularly, under the umbrella of the Golden Horde (the western portion of the Mongol Empire).

Around 1259 this tribute was organized into a census that was

enforced by the locals Rus’ princes on a regular schedule, collected,

and taken to the capital of Sarai for the Mongol leaders.

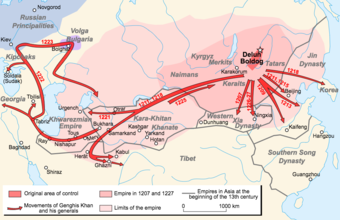

A map of the Mongol Empire as it expanded

This illustration shows the rapid expansion of the Mongol Empire as it traveled west into what became known as the Golden Horde.

Effects of Mongol Rule

Despite the fact that the established

Tatar rule was relatively peaceful, demanding taxation and the

devastation from years of invasion left many major cities in

disrepair for decades. It took years to rebuild Kiev and Pskov.

However, Novgorod continued to flourish and the relatively new city

centers of the Moscow and Tver began to prosper. Another downside to the Tatar presence was the continued threat of invasion and destruction, which happened sporadically during their presence. Each new military invasion meant heavy tolls on the local population and years of reconstruction.

Culturally, the Mongol rule brought

about major shifts during the first century of their presence.

Extensive postal road systems, military organization, and powerful

dynasties were established by Tatar alliances. Capital punishment and

torture also became more widespread during the years of Tatar rule.

Some noblemen also changed their names and adopted the Tatar

language, bringing about a shift in the aesthetic, linguistic, and

cultural ties of Russia life. Many scholars also note that the Mongol

rule was a major cause of the division of East Slavic people in Rus’

into three distinctive modern-day nations, Russia, Ukraine, and

Belarus.

12.1.5: Ivan I and the Rise of Moscow

The small trading outpost of Moscow in the north of Rus’ transformed into a wealthy cultural center in the 14th century under the leadership of Ivan I.

Learning Objective

Outline the key points that helped Moscow become so powerful and how Ivan I accomplished these major victories

Key Points

- Moscow was considered a small trading outpost under the principality of Vladimir-Suzdal into the 13th century.

- Power struggles and constant raids under the Mongol Empire’s Golden Horde caused once powerful cities, such as Kiev, to struggle financially and culturally.

- Ivan I utilized the relative calm and safety of the northern city of Moscow to entice a larger population and wealth to move there.

- Alliances between Golden Horde leaders and Ivan I saved Moscow from many of the raids and destruction of other centers, like Tver.

Key Terms

- Tver

-

A rival city to Moscow that eventually lost favor under the Golden Horde.

- Grand Prince of Vladimir

-

The title given to the ruler of this northern province, where Moscow was situated.

The Rise of Moscow

Moscow was only a small trading outpost

in the principality of Vladimir-Suzdal in Kievan Rus’ before the

invasion of Mongol forces during the 13th century. However, due to

the unstable environment of the Golden Horde, and the deft leadership

of Ivan I at a critical time during the 13th century, Moscow became a

safe haven of prosperity during his reign. It also became the new

seat of power of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Ivan I

Ivan I (also known as Ivan Kalita) was born around 1288 to the

Prince of Moscow, Daniil Aleksandrovich. He was born during a time of

devastation and upheaval in Rus’. Kiev had been overtaken by the

invading Mongol forces in 1240, and most of the Rus’ principalities

had been absorbed into the Golden Horde of the Mongol Empire by the

time Ivan was born. He ascended to the seat of Prince of Moscow after

the death of his father, and then the death of his older brother

Yury.

Ivan I

He was born around 1288 and died in either 1340 or 1341, still holding the title of Grand Prince of Vladimir.

Ivan I stepped into a role that had

already been expanded by his predecessors. Both his older brother and

his father had captured nearby lands, including Kolomna and Mozhaisk.

Yury had also made a successful alliance with the Mongol leader Uzbeg

Khan and married his sister, securing more power and advantages

within the hierarchy of the Golden Horde.

Ivan I continued the family tradition

and petitioned the leaders of the Golden Horde to gain the seat of

Grand Prince of Vladimir. His other three rivals, all princes of

Tver, had previously been granted the title in prior years. However they were all subsequently deprived of

the title and all three aspiring princes also eventually ended up murdered. Ivan

I, on the other hand, garnered the title from Khan Muhammad Ozbeg in 1328. This new title, which he kept until his death around 1340, meant he could collect taxes from the Russian lands as a ruling prince and position his tiny city as a major player in the Vladimir region.

Moscow’s Rise

During this time of upheaval, the tiny

outpost of Moscow had multiple advantages that repositioned this town

and set it up for future prosperity under Ivan I. Three major

contributing factors helped Ivan I relocate power to this area:

- It was situated in between other major

principalities on the east and west so it was often protected from the more devastating invasions. - This relative safety, compared to Tver

and Ryazan, for example, started to bring in tax-paying citizens who

wanted a safe place to build a home and earn a livelihood. - Finally, Moscow was set up perfectly

along the trade route from Novgorod to the Volga River, giving it an

economic advantage from the start.

Ivan I also spurred on the growth of

Moscow by actively recruiting people to move to the region. In

addition, he bought the freedom of people who had been captured by

the extensive Mongol raids. These recruits further bolstered the

population of Moscow. Finally, he focused his attention on

establishing peace and routing out thieves and raiding parties in the

region, making for a safe and calm metaphorical island in a storm of

unsettled political and military upsets.

Kievan Rus’ 1220-1240

This map illustrates the power dynamics at play during the 13th century shortly before Ivan I was born. Sarai, the capital of the Golden Horde, sat to the southeast, while Moscow (not visible on this map) was tucked up in the northern forests of Vladimir-Suzdal.

Ivan I knew that the peace of his

region depended upon keeping up an alliance with the Golden Horde,

which he did faithfully. Moscow’s increased wealth during this era

also allowed him to loan money to neighboring principalities. These

regions then became indebted to Moscow, bolstering its political and financial position.

In addition, a few neighboring cities

and villages were subsumed into Moscow during the 1320s and 1330s,

including Uglich, Belozero, and Galich. These shifts slowly

transformed the tiny trading outpost into a bustling city center in

the northern forests of what was once Kievan Rus’.

Russian Orthodox Church and The Center

of Moscow

Ivan I committed some of Moscow’s new

wealth to building a splendid city center and creating an iconic

religious setting. He built stone churches in the center of Moscow

with his newly gained wealth. Ivan I also tempted one of the most important religious leaders in Rus’, the Orthodox

Metropolitan Peter, to the city of Moscow. Before the rule of the Golden Horde the original Russian Orthodox Church was based

in Kiev. After years of devastation, Metropolitan Peter transferred

the seat of power to Moscow where a new Renaissance of culture was blossoming.

This perfectly timed transformation of Moscow coincided with the

decades of devastation in Kiev, effectively transferring power to the

north once again.

Peter of Moscow and scenes from his life as depicted in a 15th-century icon

This religious leader helped bring cultural power to Moscow by moving the seat of the Russian Orthodox Church there during Ivan I’s reign.

One of the most lasting accomplishments of Ivan I was to petition the Khan based in Sarai to designate his son, who would become Simeon the Proud, as the heir to the title of Grand Prince of Vladimir. This agreement a line of succession that meant the ruling head of Moscow would almost always hold power over the principality of Vladimir, ensuring Moscow held a powerful position for decades to come.

12.2: The Grand Duchy of Moscow

12.2.1: The Formation of Russia

Ivan III became Grand Prince of Moscow in 1462 and proceeded to refuse the Tatar yoke, collect surrounding lands, and consolidate political power around Moscow. His son, Vasili III, continued in his footsteps marking an era known as the “Gathering of the Russian Lands.”

Learning Objective

Outline the key points that led to a consolidated northern region under Ivan III and Vasili III in Moscow

Key Points

- Moscow had risen to a powerful position in the north due to its location and relative wealth and stability during the height of the Golden Horde.

- Ivan III overtook Novgorod, along with his four brothers’ landholdings, which began a process consolidating power under the Grand Prince of Moscow.

- Ivan III was the first prince of Rus’ to style himself as the Tsar in the grand tradition of the Orthodox Byzantine Empire.

- Vasili III followed in his father’s footsteps and continued a regime of consolidating land and practicing domestic intolerance that suppressed any attempts to disobey the seat of Moscow.

Key Terms

- Muscovite Sudebnik

-

The legal code crafted by Ivan III that further consolidated his power and outlined harsh punishments for disobedience.

- Novgorod

-

Moscow’s most prominent rival in the northern region.

- boyars

-

Members of the highest ruling class in feudal Rus’, second only to the princes.

Gathering of the Russian Lands

Ivan III was the first Muscovite prince

to consolidate Moscow’s position of power and successfully

incorporate the rival cities of Tver and Novgorod under the umbrella

of Moscow’s rule. These shifts in power in the Northern provinces

created the first semblance of a “Russian” state (though that name would not be utilized for another century). Ivan the Great

was also the first Rus’ prince to style himself a Tsar, thereby

setting up a strong start for his successor son, Vasili III. Between

the two leaders, what would become known as the “Gathering of the

Russian Lands” would occur and begin a new era of Russian history

after the Mongol Empire’s Golden Horde.

Ivan III and the End of the Golden

Horde

Ivan III Vasilyevich, also known as

Ivan the Great, was born in Moscow in 1440 and became Grand Prince of

Moscow in 1462. He ruled from this seat of power until his death in

1505. He came into power when Moscow had many economic and

cultural advantages in the norther provinces. His predecessors had

expanded Moscow’s holdings from a mere 600 miles to 15,000. The

seat of the Russian Orthodox Church was also centered in Moscow

starting in the 14th century. In addition, Moscow had long

been a loyal ally to the ruling Mongol Empire and had an optimal

position along major trade routes between Novgorod and the Volga River.

Ivan III

He held the title of Grand Prince of Moscow between 1462 and 1505.

However, one of Ivan the Great’s most

substantial accomplishments was refusing the Tatar yoke (as the

Mongol Empire’s stranglehold on Rus’ lands has been called) in

1476. Moscow refused to pay its normal Golden Horde taxes starting in

that year, which spurred Khan Ahmed to wage war against the city in

1480. It took a number of months before the Khan retreated back to

the steppe. During the following year, internal fractures within the

Mongol Empire greatly weakened the hold of Mongol rulers on the

northeastern Rus’ lands , which effectively freed Moscow from its

old duties.

Moscow’s Land Grab

The other major political change that

Ivan III instigated was a major consolidation of power in the

northern principalities, often called the “Gathering of the Russian

Lands.” Moscow’s primary rival, Novgorod, became Ivan the Great’s

first order of business. The two grand cities had been locked in

dispute for over a century, but Ivan III waged a harsh war that

forced Novgorod to cede its land to Moscow after many uprisings and

attempted alliances between Novgorod and Lithuania. The official

state document accepting Moscow’s rule was signed by Archbishop

Feofil of Novgorod in 1478. Any revolts that arose out of Novgorod

over the next decade were swiftly put down and any disobedient

Novgorodian royal family members were removed to Moscow or other

outposts to discourage further outbursts.

In addition to capturing his greatest

rival city, Ivan III also collected his four brothers’ local lands

over the course of his rule, further expanding and consolidating the

land under the power of the Grand Prince of Moscow. Ivan III also levied his political, economic, and military might over the course

of his reign to gain control of Yaroslavl, Rostov, Tver, and Vyatka,

forming one of the most unified political formations in the region

since Vladimir the Great. This new political formation was in contrast to centuries of local princes ruling over their regions relatively autonomously.

Palace of Facets pillar

This decadent pillar resides in the Palace of Facets built by Italian architects in stone in the mostly wooden Moscow Kremlin. This banquet hall was only one of many major architectural feats Ivan III built during his reign in Moscow.

Ivan the Great also greatly shaped the

future of the Rus’ lands. These major shifts included:

- Styling himself the “Tsar and

Autocrat” in Byzantine style, essentially stepping into the new leadership position in Orthodoxy after the fall of the Byzantine Empire. These changes

also occurred after he married Sophia Paleologue of Constantinople,

who had brought court and religious rituals from the Byzantine

Empire. -

He stripped the boyars of their

localized and state power and essentially created a sovereign state

that paid homage to Moscow. -

He oversaw the creation of a new legal

code, called Muscovite Sudebnik in 1497, which further consolidated

his place as the highest ruler of the northern Rus’ lands and instated

harsh penalties for disobedience, sacrilege, or attempts to undermine

the crown. -

The princes of formerly powerful

principalities now under Moscow’s rule were placed in the role of

service nobility, rather than sovereign rulers as they once were. -

Ivan III’s power was partly due to

his alliance with Russian Orthodoxy, which created an atmosphere of

anti-Catholicism and stifled the chance to build more powerful

western alliances.

Vasili III

Vasili III was the son of Sophia

Paleologue and Ivan the Great and the Grand Prince of Moscow from

1505 to 1533. He followed in his father’s footsteps and continued

to expand Moscow’s landholdings and political clout. He annexed,

Pskov, Volokolamsk, Ryazan, and Novgorod-Seversky during his reign.

His most spectacular grab for power was his capture of Smolensk, the

great stronghold of Lithuania. He utilized a rebellious ally in the

form of the Lithuanian prince Mikhail Glinski to gain this major

victory.

Vasili III

This piece was created by a contemporary artist and depicts Vasili III as a scholar and leader.

Vasili III also followed in his

father’s oppressive footsteps. He utilized alliances with the Orthodox Church to put down any rebellions or feudal disputes. He limited the

power of the boyars and the once-powerful Rurikid dynasties in newly

conquered provinces. He also increased the gentry’s landholdings,

once more consolidating power around Moscow. In general, Vasili III’s

reign was marked by an oppressive atmosphere; he carried out harsh

penalties for speaking out against the power structure or showing the slightest disobedience to the

crown.

12.2.2: Ivan the Terrible

Ivan IV, or Ivan the Terrible, reigned from 1547 to 1584 and became the first tsar of Russia. His reign was punctuated with severe oppression and cultural and political expansion, leaving behind a complex legacy.

Learning Objective

Outline the key points of Ivan IV’s policies and examine the positive and negative aspects of his rule

Key Points

- Ivan IV is often known as Ivan the Terrible, even though the more correct translation is akin to Ivan the Fearsome or Ivan the Awesome.

- Ivan IV was the first Rus’ prince to title himself “Tsar of All the Russias” beginning the long tradition of rule under the tsars.

- Lands in the Crimea, Siberia, and modern-day Tatarstan were all subsumed into Russian lands under Ivan IV.

- The persecution of the boyars during Ivan IV’s reign began under the harsh regulations of the oprichnina.

Key Terms

- oprichnina

-

A state policy enacted by Ivan IV that made him absolute monarch of much of the north and hailed in an era of boyar persecution. Ivan IV successfully grabbed large chunks of land from the nobility and created his own personal guard, the oprichniki, during this era.

- Moscow Print Yard

-

The first publishing house in Russia, which was opened in 1553.

- boyar

-

A member of the feudal ruling elite who was second only to the princes in Russian territories.

Ivan IV

Ivan

IV Vasileyevich is widely known as Ivan the Terrible or Ivan the

Fearsome. He was the Grand Prince of Moscow from 1533 to 1547 and

reigned as the “Tsar of all the Russias” from 1547 until he

died in 1584. His complex years in power precipitated military

conquests, including Kazan and Astrakhan, that changed the shape and

demographic character of Russia forever. He also reshaped the

political formation of the Russian state, oversaw a cultural

Renaissance in Russia, and shifted power to the head of state, the

tsar, a title that had never before been given to a prince in the Rus’ lands.

Rise

to Power

Ivan

IV was born in 1530 to Vasili III and Elena Glinskaya. He

was three when he was named the Grand Prince of Moscow after his father’s

death. Some say his years as the child vice-regent of Moscow under manipulative boyar

powers shaped his views for life. In 1547, at the age of sixteen, he

was crowned “Tsar of All the Russias” and was the first

person to be coronated with that title. This title claimed the

heritage of Kievan Rus’ while firmly establishing a new unified

Russian state. He also married Anastasia Romanovna, which tied him to

the powerful Romanov family.

18th-century portrait of Ivan IV

Images of Ivan IV often display a prominent brow and a frowning mouth.

Domestic

Innovations and Changes

Despite

Ivan IV’s reputation as a paranoid and moody ruler, he also

contributed to the cultural and political shifts that would shape

Russia for centuries. Among these initial changes in relatively

peaceful times he:

- Revised

the law code, the Sudebnik of 1550, which initiated a standing army,

known as the streltsy. This army would help him in future military

conquests. -

Developed

the Zemsky Sobor, a Russian parliament, along with the council of the

nobles, known as the Chosen Council. -

Regulated

the Church more effectively with the Council of the Hundred Chapters,

which regulated Church traditions and the hierarchy. -

Established

the Moscow Print Yard in 1553 and brought the first printing press to

Russia. - Oversaw

the construction of St. Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow.

St. Basil’s Cathedral

This iconic structure was one cultural accomplishment created under Ivan IV’s rule.

Oprichnina

and Absolute Monarchy

The 1560s were difficult with Russia

facing drought and famine, along with a number of Tatar invasions, and

a sea-trading blockade from the Swedes and Poles.

Ivan IV’s wife, Anastasia, was also likely poisoned and died in 1560,

leaving Ivan shaken and, some sources say, mentally unstable. Ivan IV

threatened to abdicate and fled from Moscow in 1564. However, a group

of boyars went to beg Ivan to return in order to keep the peace. Ivan agreed to return with the understanding he would be

granted absolute power and then instituted what is known as the

oprichnina.

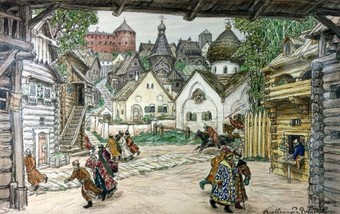

1911 painting by Apollinary Vasnetsov

This painting represents people fleeing from the Oprichniki, the secret service and military oppressors of Ivan IV’s reign.

This

agreement changed the way the Russian state worked and began an era of oppression, executions, and state surveillance. It split the

Russian lands into two distinct spheres, with the northern region

around the former Novgorod Republic placed under the

absolute power of Ivan IV. The boyar council oversaw the rest of the

Russian lands. This new proclamation also started a wave of

persecution and against the boyars. Ivan IV executed, exiled, or

forcibly removed hundreds of boyars from power, solidifying his

legacy as a paranoid and unstable ruler.

Military

Conquests and Foreign Relations

Ivan

IV established a powerful trade agreement with England and even asked

for asylum, should he need it in his fights with the boyars, from

Elizabeth I. However, Ivan IV’s greatest legacy remains his

conquests, which reshaped Russia and pushed back Tatar powers who had been dominating and invading the region for centuries.

His

first conquest was the Kazan Khanate, which had been raiding the

northeast region of Russia for decades. This territory sits in

modern-day Tatarstan. A faction of Russian supporters were already

rising up in the region but Ivan IV led his army of 150,000 to battle

in June of 1552. After months of siege and blocking Kazan’s water

supply, the city fell in October. The conquest of the entire Kazan

Khanate reshaped relations between the nomadic people and the Russian

state. It also created a more diverse population under the fold of

the Russian state and the Church.

Ivan

IV also embarked on the Livonian War, which lasted 24 years. The war

pitted Russia against the Swedish Empire, the Polish-Lithuanian

Commonwealth, and Poland. The Polish leader, Stefan Batory, was an

ally of the Ottoman Empire in the south, which was also in a

tug-of-war with Russia over territory. These two powerful entities on

each edge of Russian lands, and the prolonged wars, left the economy

in Moscow strained and Russian resources scarce in the 1570s.

Ivan

IV also oversaw two decisive territorial victories during his reign.

The first was the defeat of the Crimean horde, which meant the

southern lands were once again under Russian leadership. The second

expansion of Russian territory was headed by Cossack leader Yermak

Timofeyevich. He led expeditions into Siberian territories that had

never been under Russian rule. Between 1577 and 1580 many new

Siberian regions had reached agreements with Russian leaders,

allowing Ivan IV to style himself “Tsar of Siberia” in his last

years.

Ivan IV’s throne

This decadent throne mirrors Ivan the Terrible’s love of power and opulence.

Madness

and Legacy

Ivan

IV left behind a compelling and contradictory legacy. Even his

nickname “terrible” is a source for confusion. In Russian the

word grozny means “awesome,” “powerful” or “thundering,”

rather than “terrible” or “mad.” However, Ivan IV often

behaved in ruthless and paranoid ways that favors the less flattering interpretation. He persecuted the long-ruling

boyars and often accused people of attempting to murder him (which

makes some sense when you look at his family’s history). His often

reckless foreign policies, such as the drawn out Livonian War, left

the economy unstable and fertile lands a wreck. Legend also suggests he murdered his son Ivan Ivanovich, whom he had groomed for the

throne, in 1581, leaving the throne to his childless son Feodor

Ivanovich. However, his dedication to culture and innovation reshaped

Russia and solidified its place in the East.

12.2.3: The Time of Troubles

The Time of Troubles occurred between 1598 and 1613 and was caused by severe famine, prolonged dynastic disputes, and outside invasions from Poland and Sweden. The worst of it ended with the coronation of Michael I in 1613.

Learning Objective

Outline the distinctive features of the Time of Troubles and how they eventually ended

Key Points

- The Time of Troubles started with the death of the childless Tsar Feodor Ivanovich, which spurred an ongoing dynastic dispute.

- Famine between 1601 and 1603 caused massive starvation and further strained Russia.

- Two false heirs to the throne, known as False Dmitris, were backed by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth that wanted to grab power in Moscow.

- Rurikid Prince Dmitry Pozharsky and Novgorod merchant Kuzma Minin led the final resistance against Polish invasion that ended the dynastic dispute and reclaimed Moscow in 1613.

Key Terms

- Feodor Ivanovich

-

The last tsar of the Rurik Dynasty, whose death spurred on a major dynastic dispute.

- Dmitry Pozharsky

-

The Rurikid prince that successfully ousted Polish forces from Moscow.

- Zemsky Sobor

-

A form of Russian parliament that met to vote on major state decisions, and was comprised of nobility, Orthodox clergy, and merchant representatives.

The Time of Troubles was an era of

Russian history dominated by a dynastic crisis and exacerbated

by ongoing wars with Poland and Sweden, as well as a devastating famine. It began with the death of the childless

last Russian Tsar of the Rurik Dynasty, Feodor Ivanovich, in 1598 and

continued until the establishment of the Romanov Dynasty in 1613. It

took another six years to end two of the wars that had started during

the Time of Troubles, including the Dymitriads against the

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Famine and Unrest

At the death of

Feodor Ivanovich, the last Rurikid Tsar, in 1598, his brother-in-law and trusted advisor,

Boris Godunov, was elected his successor by the Zemsky Sobor (Great

National Assembly). Godunov was a leading boyar and had accomplished

a great deal under the reign of the mentally-challenged and childless

Feodor. However, his position as a boyar caused unrest among the Romanov clan who saw it as an affront to follow a lowly boyar. Due

to the political unrest, strained resources, and factions against his

rule, he was not able to accomplish much during his short reign,

which only lasted until 1605.

Tsar Boris Godunov

His short-lived reign was beset by famine and resistance from the boyars.

While Godunov was attempting to keep

the country stitched together, a devastating famine swept across

Russian from 1601 to 1603. Most likely caused by a volcanic eruption

in Peru in 1600, the temperatures stayed well below normal during the

summer months and often went below freezing at night. Crops failed

and about two million Russians, a third of the population, perished

during this famine. This famine also caused people to flock to Moscow

for food supplies, straining the capital both socially and

financially.

Dynastic Uncertainty and False Dmitris

The troubles did not cease after the

famine subsided. In fact, 1603 brought about new political and

dynastic struggles. Feodor Ivanovich’s younger brother was

reportedly stabbed to death before the Tsar’s death, but some

people still believed he had fled and was alive. The first of the

nicknamed False Dmitris appeared in the Polish-Lithuanian

Commonwealth in 1603 claiming he was the lost young brother of Ivan the Terrible.

Polish forces saw this pretender’s appearance as an opportunity to regain land and

influence in Russia and the some 4,000 troops comprised of Russian

exiles, Lithuanians, and Cossacks crossed the border and began what

is known as the Dymitriad wars.

Vasili IV of Russia

He was the last member of the Rurikid Dynasty to rule in Moscow between 1606 and 1610.

False Dmitri was supported by enough

Polish and Russian rebels hoping for a rich reward that he was

married to Marina Mniszech and ascended to the throne in Moscow at

Boris Godunov’s death in 1605. Within a year Vasily Shuisky (a

Rurikid prince) staged an uprising against False Dmitri, murdered

him, and seized control of power in Moscow for himself. He ruled between 1606 and 1610 and was known as Vasili IV. However, the

boyars and mercenaries were still displeased with this new ruler. At

the same time as Shuisky’s ascent, a new False Dmitri appeared on the

scene with the backing of the Polish-Lithuanian magnates.

An Empty Throne and Wars

Shuisky retained power long enough to

make a treaty with Sweden, which spurred a worried Poland into

officially beginning the Polish-Muscovite War that lasted from 1605

to 1618. The struggle over who would gain control of Moscow became

entangled and complex once Poland became an acting participant.

Shuisky was still on the throne, both the second False Dmitri and the

son of the Polish king, Władysław, were attempting to take control.

None of the three pretenders succeeded,

however, when the Polish king himself, Sigismund III, decided he would take

the seat in Moscow.

Russia was stretched to its limit by

1611. Within the five years after Boris Godunov’s death powers had

shifted considerably:

- The boyars quarreled amongst themselves

over who should rule Moscow while the throne remained empty. - Russian Orthodoxy was imperiled and

many Orthodox religious leaders were imprisoned. - Catholic Polish forces occupied the

Kremlin in Moscow and Smolensk. - Swedish forces had taken over Novgorod

in retaliation to Polish forces attempting to ally with Russia. - Tatar raids continued in the south

leaving many people dead and stretched for resources.

The End of Troubles

Two strong leaders arose out of the

chaos of the first decade of the 17th century to combat the Polish

invasion and settle the dynastic dispute. The powerful Novgordian

merchant Kuzma Minin along with the Rurikid Prince Dmitry Pozharsky

rallied enough forces to push back the Polish forces in Russia. The

new Russian rebellion first pushed Polish forces back to the Kremlin,

and between November 3rd and 6th (New Style) Prince Pozharsky had

forced the garrison to surrender in Moscow. November 4 is known as National

Unity Day, however it fell out of favor during Communism, only to be

reinstated in 2005.

The dynastic wars finally came to an

end when the Grand National Assembly elected Michael Romanov, the son

of the metropolitan Philaret, to the throne in 1613. The new Romanov Tsar, Michael I, quickly had the second False Dmitri’s son

and wife killed, to stifle further uprisings.

Michael I

The first Romanov Tsar to be crowned in 1613.

Despite the end to internal unrest, the

wars with Sweden and Poland would last until 1618 and 1619

respectively, when peace treaties were finally enacted. These

treaties forced Russia to cede some lands, but the dynastic

resolution and the ousting of foreign powers unified most people in

Russia behind the new Romanov Tsar and started a new era.

12.2.4: The Romanovs

The Romanov Dynasty was officially founded at the coronation of Michael I in 1613. It was the second royal dynasty in Russia after the Rurikid princes of the Middle Ages. The Romanov name stayed in power until the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in 1917.

Learning Objective

Explain the rise of power of the House of Romanov and the first major Russian Tsars of this dynasty

Key Points

- The Romanovs were exiled during the Time of Troubles but brought back when Romanovs Patriarch Philaret and his son Michael were politically advantageous.

- Michael I was the first Romanov Tsar and began a long line of powerful rulers.

- Alexis I successfully navigated Russia through multiple uprisings and wars and created long-lasting political bureaus.

- After a long dynastic dispute, Peter the Great rose to power and changed Russia with the new capital of St. Petersburg and western influences.

Key Terms

- Old Believers

-

Followers of the Orthodox faith the way it was practiced before Alexis I convened the Great Moscow Synod and changed the traditions.

- Duma chancellory

-

The first provincial administrative bureau created under Alexis I. In Russian it is called Razryadny Prikaz.

- Rurikid

-

A descendent of the Rurik Dynasty, which dominated seats of power throughout Russian lands for over six centuries before the Romanov Dynasty began.

The House of Romanov

The

House of Romanov was the second major royal dynasty in Russia, and

arose after the Rurikid Dynasty. It was founded in 1613 with the

coronation of Michael I and ended in 1917 with the abdication of Tsar

Nicholas II. However, the direct male blood line of the Romanov

Dynasty ended when Elizabeth of Russia died in 1762, and Peter III, followed by Catherine the Great, were placed in power, both

German-born royalty.

Roots

of the Romanovs

The

earliest common ancestor for the Romanov clan goes back to Andrei

Kobyla. Sources say he was a boyar under the leadership of the

Rurikid prince Semyon I of Moscow in 1347. This figure remains

somewhat mysterious with some sources claiming he was the high-born

son of a Rus’ prince. Others point to the name Kobyla, which means

horse, suggesting he was descended from the Master of Horse

in the royal household.

Whatever

the real origins of this patriarch-like figure, his descendants split

into about a dozen different branches over the next couple of

centuries. One such descendent, Roman Yurievich Zakharyin-Yuriev, gave

the Romanov Dynasty its name. Grandchildren of this patriarch changed

their name to Romanov and it remained there until they rose to power.

Michael

I

The

Romanov Dynasty proper was founded after the Time of Troubles, an era

between 1598 and 1613, which included a dynastic struggle, wars with

Sweden and Poland, and severe famine. Tsar Boris Godunov’s rule,

which lasted until 1605, saw the Romanov families exiled to the Urals and

other remote areas. Michael I’s father was forced to take monastic

vows and adopt the name Philaret. Two impostors attempting to gain the

throne in Moscow attempted to leverage Romanov power after Godunov died in

1605. And by 1613, the Romanov family had again become a popular name in the running for

power.

Patriarch Philaret’s son, Michael I, was voted into power by the zemsky sober in

July 1613, ending a long dynastic dispute. He unified the boyars and

satisfied the Moscow royalty as the son of Feodor Nikitich Romanov (now Patriarch Philaret) and the nephew of the Rurikid Tsar Feodor I. He was only sixteen at

his coronation, and both he and his mother were afraid of his future

in such a difficult political position.

Representation of a young Michael I

He rose to power in Moscow when he was just sixteen and went on to become an influential leader in Russian history.

Michael

I reinstated order in Moscow over his first years in power and also

developed two major government offices, the Posolsky Prikaz (Foreign

Office) and the Razryadny Prikaz (Duma chancellory, or provincial

administration office). These two offices remained essential to

Russian order for a many decades.

Alexis

I

Michael

I ruled until his death in 1645 and his son, Alexis, took over the

throne at the age of sixteen, just like his father. His reign would

last over 30 years and ended at his death in 1676. His reign was

marked by riots in cities such Pskov and Novgorod, as well as continued wars

with Sweden and Poland.

Alexis I of Russian in the 1670s

His policies toward the Church and peasant uprisings created new legal codes and traditions that lasted well into the 19th century.

However,

Alexis I established a new legal code called Subornoye Ulozheniye,

which created a serf class, made hereditary class unchangeable, and

required official state documentation to travel between towns. These

codes stayed in effect well into the 19th century. Under Alexis I’s

rule, the Orthodox Church also convened the Great Moscow Synod, which

created new customs and traditions. This historic moment created a

schism between what are termed Old Believers (those attached to the

previous hierarchy and traditions of the Church) and the new Church

traditions. Alexis I’s legacy paints him as a peaceful and

reflective ruler, with a propensity for progressive ideas.

Dynastic

Dispute and Peter the Great

At

the death of Alexis I in 1676, a dynastic dispute erupted between the

children of his first wife, namely Fyodor

III, Sofia

Alexeyevna, Ivan

V, and the son of his second wife, Peter Alexeyevich (later Peter the Great).

The crown was quickly passed down through the children of his first

wife. Fyodor III died from illness after ruling for only six years.

Between 1682 and 1689 power was contested between Sofia Alexeyevna,

Ivan V, and Peter. Sofia served as regent from 1682 to 1689. She

actively opposed Peter’s claim to the throne in favor of her own

brother, Ivan. However, Ivan V and Peter shared the throne until

Ivan’s death in 1696.

Peter the Great as a young ruler in 1698

This portrait was a gift to the King of England and displays a western style that was rarely scene in royal portraits before this time. He is not wearing a beard or the traditional caps and robes that marked Russian nobility before his rule.

Peter went on to

rule over Russia, and even style himself Emperor of all Russia in

1721, and ruled until his death in 1725. He built a new capital in

St. Petersburg, where he built a navy and attempted to wrest control

of the Baltic Sea. He is also remembered for bringing western culture

and Enlightenment ideas to Russia, as well as limiting the control of the Church.