6.1: Types of Social Groups

6.1.1: The Nature of Groups

A social group is two or more humans who interact with one another, share similar characteristics, and collectively have a sense of unity.

Learning Objective

Contrast the social cohesion-based concept of a social group with the social identity concept

Key Points

- A social group exhibits some degree of social cohesion and is more than a simple collection or aggregate of individuals.

- Social cohesion can be formed through shared interests, values, representations, ethnic or social background, and kinship ties, among other factors.

- The social identity approach posits that the necessary and sufficient conditions for the formation of social groups is the awareness that an individual belongs and is recognized as a member of a group.

- The social identity approach posits that the necessary and sufficient conditions for the formation of social groups is the awareness that the individual belongs and is recognized as a member of a group.

Key Terms

- The social cohesion approach

-

More than a simple collection or aggregate of individuals, such as people waiting at a bus stop, or people waiting in a line.

- The social identity approach

-

Posits that the necessary and sufficient condition for the formation of social groups is awareness of a common category membership.

- social group

-

A collection of humans or animals that share certain characteristics, interact with one another, accept expectations and obligations as members of the group, and share a common identity.

Example

- Examples of groups include families, companies, circles of friends, clubs, local chapters of fraternities and sororities, and local religious congregations.

In the social sciences, a social group is two or more humans who interact with one another, share similar characteristics, and have a collective sense of unity. This is a very broad definition, as it includes groups of all sizes, from dyads to whole societies. A society can be viewed as a large group, though most social groups are considerably smaller. Society can also be viewed as people who interact with one another, sharing similarities pertaining to culture and territorial boundaries.

A social group exhibits some degree of social cohesion and is more than a simple collection or aggregate of individuals, such as people waiting at a bus stop or people waiting in a line. Characteristics shared by members of a group may include interests, values, representations, ethnic or social background, and kinship ties. One way of determining if a collection of people can be considered a group is if individuals who belong to that collection use the self-referent pronoun “we;” using “we” to refer to a collection of people often implies that the collection thinks of itself as a group. Examples of groups include: families, companies, circles of friends, clubs, local chapters of fraternities and sororities, and local religious congregations.

Renowned social psychologist Muzafer Sherif formulated a technical definition of a social group. It is a social unit consisting of a number of individuals interacting with each other with respect to:

- common motives and goals;

- an accepted division of labor;

- established status relationships;

- accepted norms and values with reference to matters relevant to the group; and

- the development of accepted sanctions, such as raise and punishment, when norms were respected or violated.

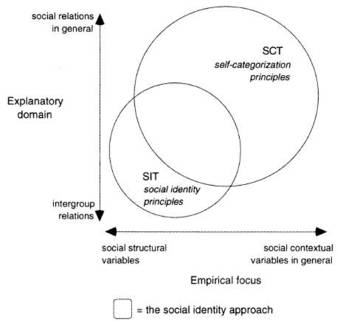

Explicitly contrasted with a social cohesion-based definition for social groups is the social identity perspective, which draws on insights made in social identity theory. The social identity approach posits that the necessary and sufficient conditions for the formation of social groups is “awareness of a common category membership” and that a social group can be “usefully conceptualized as a number of individuals who have internalized the same social category membership as a component of their self concept. ” Stated otherwise, while the social cohesion approach expects group members to ask “who am I attracted to? ” the social identity perspective expects group members to simply ask “who am I? “

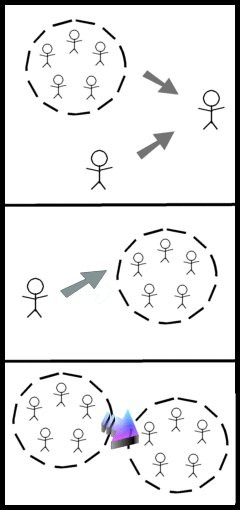

Social Identity Approach

The explanatory profiles of social identity and self-categorization theories.

Law Enforcement Officials

A law enforcement official is a social category, not a group. However, law enforcement officials who all work in the same station and regularly meet to plan their day and work together would be considered part of a group.

6.1.2: Primary Groups

A primary group is typically a small social group whose members share close, personal, enduring relationships.

Learning Objective

List at least three defining characteristics of a primary group

Key Points

- Primary groups are marked by concern for one another, shared activities and culture, and long periods of time spent together. They are psychologically comforting and quite influential in developing personal identity.

- Families and close friends are examples of primary groups.

- The goal of primary groups is actually the relationships themselves rather than achieving some other purpose.

- The concept of the primary group was introduced by Charles Cooley in his book, Social Organization: A Study of the Larger Mind.

Key Terms

- Close friends

-

They are examples of primary groups.

- group

-

A number of things or persons being in some relation to one another.

- relationship

-

Connection or association; the condition of being related.

Example

- A primary group is a group in which one exchanges implicit items, such as love, caring, concern, support, etc. Examples of these would be family groups, love relationships, crisis support groups, and church groups.

Sociologists distinguish between two types of groups based upon their characteristics. A primary group is typically a small social group whose members share close, personal, enduring relationships. These groups are marked by concern for one another, shared activities and culture, and long periods of time spent together. The goal of primary groups is actually the relationships themselves rather than achieving some other purpose. Families and close friends are examples of primary groups.

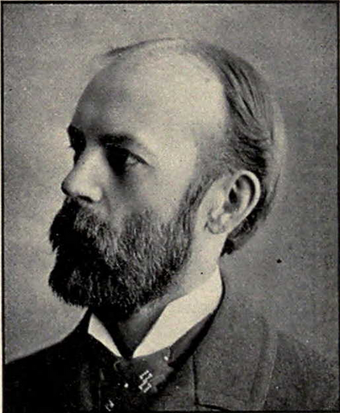

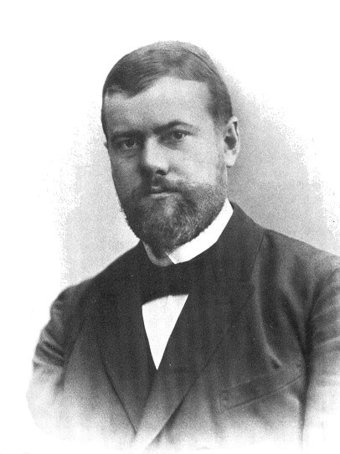

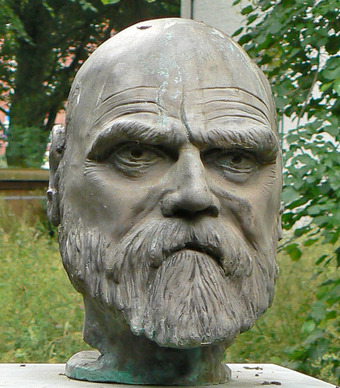

Charles Cooley

The concept of the primary group was introduced by Charles Cooley, a sociologist from the Chicago School of sociology, in his book Social Organization: A Study of the Larger Mind (1909). Primary groups play an important role in the development of personal identity. Cooley argued that the impact of the primary group is so great that individuals cling to primary ideals in more complex associations and even create new primary groupings within formal organizations. To that extent, he viewed society as a constant experiment in enlarging social experience and in coordinating variety. He, therefore, analyzed the operation of such complex social forms as formal institutions and social class systems and the subtle controls of public opinion.

Functions of Primary Groups

A primary group is a group in which one exchanges implicit items, such as love, caring, concern, support, etc. Examples of these would be family groups, love relationships, crisis support groups, and church groups. Relationships formed in primary groups are often long lasting and goals in themselves. They also are often psychologically comforting to the individuals involved and provide a source of support and encouragement.

Charles Cooley

The concept of the primary group was introduced by Charles Cooley, a sociologist from the Chicago School of sociology, in his book, “Social Organization: A Study of the Larger Mind” (1909).

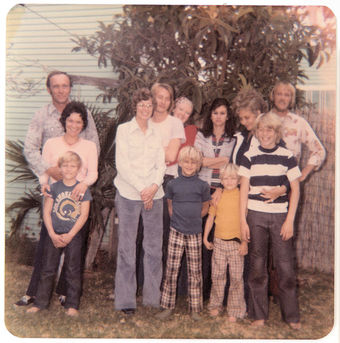

Families as Social Groups

This family from the 1970s would be an example of a primary group.

6.1.3: Secondary Groups

Secondary groups are large groups whose relationships are impersonal and goal oriented; their relationships are temporary.

Learning Objective

Outline the main distinctions between primary and secondary groups

Key Points

- The distinction between primary and secondary groups was originally proposed by Charles Cooley. He termed them “secondary” because they generally develop later in life and are much less likely to be influential on one’s identity than primary groups.

- Secondary relationships involve weak emotional ties and little personal knowledge of one another. In contrast to primary groups, secondary groups don’t have the goal of maintaining and developing the relationships themselves.

- Secondary groups include groups in which one exchanges explicit commodities, such as labor for wages, services for payments, and such. They also include university classes, athletic teams, and groups of co-workers.

Key Terms

- group

-

A number of things or persons being in some relation to one another.

- primary group

-

It is typically a small social group whose members share close, personal, enduring relationships. These groups are marked by concern for one another, shared activities and culture, and long periods of time spent together.

- Secondary groups

-

They are large groups whose relationships are impersonal and goal-oriented.

Example

- Examples of secondary groups include vendor-to-client relationships, a doctor-to-patient relationship, a mechanic, an accountant, and such.

Unlike first groups, secondary groups are large groups whose relationships are impersonal and goal oriented. People in a secondary group interact on a less personal level than in a primary group, and their relationships are generally temporary rather than long lasting. Some secondary groups may last for many years, though most are short term. Such groups also begin and end with very little significance in the lives of the people involved.

Secondary relationships involve weak emotional ties and little personal knowledge of one another. In contrast to primary groups, secondary groups don’t have the goal of maintaining and developing the relationships themselves.

Charles Cooley

The distinction between primary and secondary groups was originally proposed by Charles Cooley. He labeled groups as “primary” because people often experience such groups early in their life and such groups play an important role in the development of personal identity. Secondary groups generally develop later in life and are much less likely to be influential on one’s identity.

Functions

Since secondary groups are established to perform functions, people’s roles are more interchangeable. A secondary group is one you have chosen to be a part of. They are based on interests and activities. They are where many people can meet close friends or people they would just call acquaintances. Secondary groups are also groups in which one exchanges explicit commodities, such as labor for wages, services for payments, etc. Examples of these would be employment, vendor-to-client relationships, a doctor, a mechanic, an accountant, and such. A university class, an athletic team, and workers in an office all likely form secondary groups. Primary groups can form within secondary groups as relationships become more personal and close.

Classmates as Secondary Groups

A class of students is generally considered a secondary group.

Doctors as Secondary Groups

The doctor-patient relationship is another example of secondary groups.

6.1.4: In-Groups and Out-Groups

In-groups are social groups to which an individual feels he or she belongs, while an individual doesn’t identify with the out-group.

Learning Objective

Recall two of the key features of in-group biases toward out-groups

Key Points

- In-group favoritism refers to a preference and affinity for one’s in-group over the out-group, or anyone viewed as outside the in-group.

- One of the key determinants of group biases is the need to improve self-esteem. That is individuals will find a reason, no matter how insignificant, to prove to themselves why their group is superior.

- Intergroup aggression is any behavior intended to harm another person, because he or she is a member of an out-group, the behavior being viewed by its targets as undesirable.

- The out-group homogeneity effect is one’s perception of out-group members as more similar to one another than are in-group members (e.g., “they are alike; we are diverse”).

- Prejudice is a hostile or negative attitude toward people in a distinct group, based solely on their membership within that group.

- A stereotype is a generalization about a group of people in which identical characteristics are assigned to virtually all members of the group, regardless of actual variation among the members.

Key Terms

- In-group favoritism

-

It refers to a preference and affinity for one’s in-group over the out-group, or anyone viewed as outside the in-group. This can be expressed in evaluation of others, linking, allocation of resources and many other ways.

- Intergroup aggression

-

It is any behavior intended to harm another person because he or she is a member of an out-group, the behavior being viewed by its targets as undesirable.

- in-group bias

-

It refers to a preference and affinity for one’s in-group over the out-group, or anyone viewed as outside the in-group.

Example

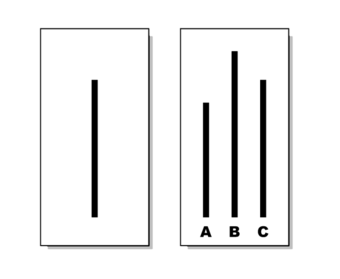

- In an experiment testing out-group homogeneity, researchers revealed that people of other races do seem to look more alike than members of one’s own race. When white students were shown faces of a few white and a few black individuals, they later more accurately recognized white faces they had seen and often falsely recognized black faces not seen before. The opposite results were found when subjects consisted of black individuals.

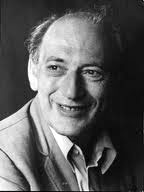

In sociology and social psychology, in-groups and out-groups are social groups to which an individual feels as though he or she belongs as a member, or towards which they feel contempt, opposition, or a desire to compete, respectively. People tend to hold positive attitudes towards members of their own groups, a phenomenon known as in-group bias. The term originates from social identity theory which grew out of the work of social psychologists Henri Tajfel and John Turner .

Henri Tajfel

The in-group and out-group concepts originate from social identity theory, which grew out of the work of social psychologists Henri Tajfel and John Turner.

In-group favoritism refers to a preference and affinity for one’s in-group over the out-group or anyone viewed as outside the in-group. This can be expressed in evaluation of others, linking, allocation of resources, and many other ways. A key notion in understanding in-group/out-group biases is determining the psychological mechanism that drives the bias. One of the key determinants of group biases is the need to improve self-esteem. That is individuals will find a reason, no matter how insignificant, to prove to themselves why their group is superior.

Intergroup aggression is any behavior intended to harm another person because he or she is a member of an out group. Intergroup aggression is a by product of in-group bias, in that if the beliefs of the in-group are challenged or if the in-group feels threatened, then they will express aggression toward the out-group. The major motive for intergroup aggression is the perception of a conflict of interest between in-group and out-group. The way the aggression is justified is through dehumanizing the out-group, because the more the out-group is dehumanized the “less they deserve the humane treatment enjoined by universal norms. “

The out-group homogeneity effect is one’s perception of out-group members as more similar to one another than are in-group members, e.g. “they are alike; we are diverse. ” The out-group homogeneity effect has been found using a wide variety of different social groups, from political and racial groups to age and gender groups. Perceivers tend to have impressions about the diversity or variability of group members around those central tendencies or typical attributes of those group members. Thus, out-group stereotypicality judgments are overestimated, supporting the view that out-group stereotypes are over-generalizations In an experiment testing out-group homogeneity, researchers revealed that people of other races are perceived to look more alike than members of one’s own race. When white students were shown faces of a few white and a few black individuals, they later more accurately recognized white faces they had seen and often falsely recognized black faces not seen before. The opposite results were found when subjects consisted of black individuals.

Prejudice is a hostile or negative attitude toward people in a distinct group, based solely on their membership within that group. There are three components. The first is the affective component, representing both the type of emotion linked with the attitude and the severity of the attitude. The second is a cognitive component, involving beliefs and thoughts that make up the attitude. The third is a behavioral component, relating to one’s actions – people do not just hold attitudes, they act on them as well. Prejudice primarily refers to a negative attitude about others, although one can also have a positive prejudice in favor of something. Prejudice is similar to stereotype in that a stereotype is a generalization about a group of people in which identical characteristics are assigned to virtually all members of the group, regardless of actual variation among the members.

French Stereotypes

Prejudice is similar to stereotype in that a stereotype is a generalization about a group of people in which identical characteristics are assigned to virtually all members of the group, regardless of actual variation among the members.

6.1.5: Reference Groups

Sociologists call any group that individuals use as a standard for evaluating themselves and their own behavior a reference group.

Learning Objective

Explain the purpose of a reference group

Key Points

- Social comparison theory argues that individuals use comparisons with others to gain accurate self-evaluations and learn how to define the self. A reference group is a concept referring to a group to which an individual or another group is compared.

- Reference groups provide the benchmarks and contrast needed for comparison and evaluation of group and personal characteristics.

- Robert K. Merton hypothesized that individuals compare themselves with reference groups of people who occupy the social role to which the individual aspires.

Key Terms

- social role

-

it is a set of connected behaviors, rights, and obligations as conceptualized by actors in a social situation.

- self-identity

-

a multi-dimensional construct that refers to an individual’s perception of “self” in relation to any number of characteristics, such as academics and non academics, gender roles and sexuality, racial identity,and many others.

- reference group

-

it is a concept referring to a group to which an individual or another group is compared.

Example

- For example, an individual in the U.S. with an annual income of $80,000, may consider himself affluent if he compares himself to those in the middle of the income strata, who earn roughly $32,000 a year. If, however, the same person considers the relevant reference group to be those in the top 0.1% of households in the U.S., those making $1.6 million or more, then the individual’s income of $80,000 would make him or her seem rather poor.

Social comparison theory is centered on the belief that there is a drive within individuals to gain accurate self-evaluations. Individuals evaluate their own opinions and define the self by comparing themselves to others. One important concept in this theory is the reference group. A reference group refers to a group to which an individual or another group is compared. Sociologists call any group that individuals use as a standard for evaluating themselves and their own behavior a reference group.

Reference groups are used in order to evaluate and determine the nature of a given individual or other group’s characteristics and sociological attributes. It is the group to which the individual relates or aspires to relate himself or herself psychologically. Reference groups become the individual’s frame of reference and source for ordering his or her experiences, perceptions, cognition, and ideas of self. It is important for determining a person’s self-identity, attitudes, and social ties. These groups become the basis of reference in making comparisons or contrasts and in evaluating one’s appearance and performance.

Robert K. Merton hypothesized that individuals compare themselves with reference groups of people who occupy the social role to which the individual aspires. Reference groups act as a frame of reference to which people always refer to evaluate their achievements, their role performance, aspirations and ambitions. A reference group can either be from a membership group or non-membership group.

An example of a reference group is a group of people who have a certain level of affluence. For example, an individual in the U.S. with an annual income of $80,000, may consider himself affluent if he compares himself to those in the middle of the income strata, who earn roughly $32,000 a year. If, however, the same person considers the relevant reference group to be those in the top 0.1% of households in the U.S., those making $1.6 million or more, then the individual’s income of $80,000 would make him or her seem rather poor.

Reference group

Reference groups provide the benchmarks and contrast needed for comparison and evaluation of group and personal characteristics.

Reference group

Reference groups become the individual’s frame of reference and source for ordering his or her experiences, perceptions, cognition, and ideas of self.

6.1.6: Social Networks

A social network is a social structure between actors, connecting them through various social familiarities.

Learning Objective

Diagram, in miniature, your social networks using nodes and ties

Key Points

- The study of social networks is called both “social network analysis” and “social network theory”.

- Social network theory views social relationships in terms of nodes and ties. Nodes are the individual actors within the networks, and ties are the relationships between the actors.

- In sociology, social capital is the expected collective or economic benefits derived from the preferential treatment and cooperation between individuals and groups.

- The rule of 150 states that the size of a genuine social network is limited to about 150 members.

- The small world phenomenon is the hypothesis that the chain of social acquaintances required to connect one arbitrary person to another arbitrary person anywhere in the world is generally short.

- Milgram also identified the concept of the familiar stranger, or an individual who is recognized from regular activities, but with whom one does not interact.

- Milgram also identified the concept of the familiar stranger, or an individual who is recognized from regular activities, but with whom one does not interact.

Key Terms

- node

-

They are the individual actors within the networks, and ties are the relationships between the actors.

- social capital

-

The good will, sympathy, and connections created by social interaction within and between social networks.

Examples

- Recent research suggests that the social networks of Americans are shrinking, and more and more people have no close confidants or people with whom they can share their most intimate thoughts. In 1985, the mean network size of individuals in the United States was 2.94 people. Networks declined by almost an entire confidant by 2004, to 2.08 people. Almost half, 46.3% of Americans, say they have only one or no confidants with whom they can discuss important matters. The most frequently occurring response to the question of how many confidants one has was zero in 2004.

- Somebody who is seen daily on the train or at the gym, but with whom one does not otherwise communicate, is an example of a familiar stranger.

A social network is a social structure between actors, either individuals or organizations. It indicates the ways in which they are connected through various social familiarities, ranging from casual acquaintance to close familial bonds. The study of social networks is called both “social network analysis” and “social network theory. ” Research in a number of academic fields has demonstrated that social networks operate on many levels, from families up to the level of nations, and play a critical role in determining the way problems are solved, organizations are run, and the degree to which individuals succeed in achieving their goals. Sociologists are interested in social networks because of their influence on and importance for the individual. Social networks are the basic tools used by individuals to meet other people, recreate, and to find social support.

Social Network Illustration

An example of a social network diagram

Social network theory views social relationships in terms of nodes and ties. Nodes are the individual actors within the networks, and ties are the relationships between the actors. There can be many kinds of ties between the nodes. In its most simple form, a social network is a map of all of the relevant ties between the nodes being studied. The network can also be used to determine the social capital of individual actors. In sociology, social capital is the expected collective or economic benefits derived from the preferential treatment and cooperation between individuals and groups.

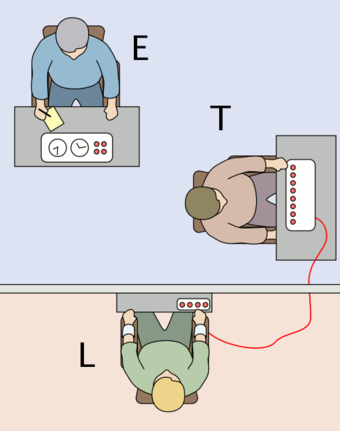

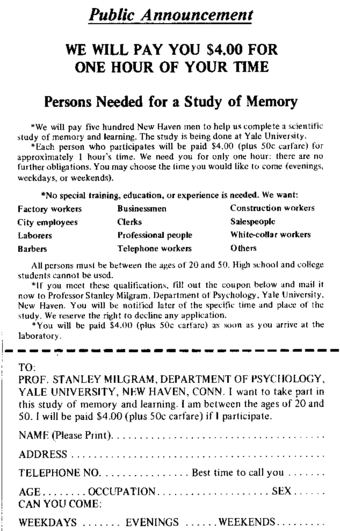

The rule of 150 states that the size of a genuine social network is limited to about 150 members. The rule arises from cross-cultural studies in sociology and especially anthropology of the maximum size of a village. The small world phenomenon is the hypothesis that the chain of social acquaintances required to connect one arbitrary person to another arbitrary person anywhere in the world is generally short. The concept gave rise to the famous phrase “six degrees of separation” after a 1967 small world experiment by psychologist Stanley Milgram that found that two random U.S. citizens were connected by an average of six acquaintances. Milgram also identified the concept of the familiar stranger, or an individual who is recognized from regular activities, but with whom one does not interact. Somebody who is seen daily on the train or at the gym, but with whom one does not otherwise communicate, is an example of a familiar stranger. If such individuals meet in an unfamiliar setting, for example, while travelling, they are more likely to introduce themselves than would perfect strangers, since they have a background of shared experiences.

Studies

Recent research suggests that the social networks of Americans are shrinking, and more and more people have no close confidants or people with whom they can share their most intimate thoughts. In 1985, the mean network size of individuals in the United States was 2.94 people. Networks declined by almost an entire confidant by 2004, to 2.08 people. Almost half, 46.3% of Americans, say they have only one or no confidants with whom they can discuss important matters. The most frequently occurring response to the question of how many confidants one has was zero in 2004.

6.1.7: Online Communities

On the Internet, social interactions can occur in online communities that preclude the need to be face-to-face.

Learning Objective

Discuss at least three central features of online communities

Key Points

- An online community is a virtual community that exists online and whose members enable its existence through taking part in membership rituals.

- An online community can take the form of an information system where anyone can post content, such as a bulletin board system or one where only a restricted number of people can initiate posts, such as Weblogs.

- Cost plays a role in all aspects and stages for online communities. Fairly cheap and easily attainable technologies and programs have also influenced the increase in establishment of online communities.

Key Terms

- Online communities

-

It is a virtual community that exists online and whose members enable its existence through taking part in membership ritual.

- information system

-

Any data processing system, either manual or computerized

- weblog

-

A website in the form of an ongoing journal; a blog.

Example

- In 2001, consultants at McKinsey & Company did a study where they found that only 2% of transaction site customers returned after their first purchase. In contrast, 60% of new online communities users began using and visiting the sites regularly after their first experiences. Online communities have changed the game for retail firms, as they have forced them to change their business strategies.

An online community is a virtual community that exists online and whose members enable its existence through taking part in membership rituals. An online community can take the form of an information system where anyone can post content, such as a bulletin board system or one where only a restricted number of people can initiate posts, such as Weblogs. Online communities have also become a supplemental form of communication between people who know each other primarily in real life. Many means are used in social software separately or in combination, including text-based chat rooms and forums that use voice, video text, or avatars.

The Development of Online Communities

The idea of a community is not a new concept. What is new, however, is transferring it over into the online world. A community was previously defined as a group from a single location. If you lived in the designated area, you became a part of that community. Interaction between community members was done primarily face-to-face and in a social setting. This definition for community no longer applies. In the online world, social interactions no longer have to be face-to-face or based on proximity. Instead, they can be with literally anyone, anywhere. There is a set of values to consider when developing an online community. Some of these values include: opportunity, education, culture, democracy, human services, equality within the economy, information, sustainability, and communication.

Cost plays a role in all aspects and stages for online communities. Fairly cheap and easily attainable technologies and programs have also influenced the increase in establishment of online communities. While payment is necessary to participate in some online communities, such as certain dating websites or for monthly game subscriptions, many other sites are free to users such as the social networks Facebook and Twitter. Because of deregulation and increased Internet access, the popularity of online communities has escalated. Online communities provide instant gratification, entertainment, and learning.

Building Online Communities

Every online community has a distinct set of members who participate differently. A lurker observes the community and viewing content, but does not add to the community content or discussion. A novice engages the community, starts to provide content, and tentatively interacts in a few discussions. A regular consistently adds to the community discussion and content and interacts with other users. A leader is recognized as a veteran participant, connecting with regulars to make higher concepts and ideas. Finally, an elder leaves the community for a variety of reasons. For instance, the elder might experience a change in interests or lack the time to stay connected.

Studies

In 2001, consultants at McKinsey & Company did a study where they found that only 2% of transaction site customers returned after their first purchase. In contrast, 60% of new online communities users began using and visiting the sites regularly after their first experiences. Online communities have changed the game for retail firms, as they have forced them to change their business strategies.

While payment is necessary to participate in some online communities, such as certain dating websites or for monthly game subscriptions, many other sites are free to users such as social networks Facebook and Twitter.

6.2: Functions of Social Groups

6.2.1: Defining Boundaries

Social groups are defined and separated by boundaries.

Learning Objective

Explain what tends to happen to individuals when their group boundaries are impermeable, and also when they are permeable

Key Points

- Cultural sociologists define symbolic boundaries as “conceptual distinctions made by social actors…that separate people into groups and generate feelings of similarity and group membership. ” These boundaries are necessary for the existence of in-groups and out-groups.

- Where group boundaries are considered permeable (e.g., a group member may pass from a low status group into a high status group), individuals are more likely to engage in individual mobility strategies.

- Where group boundaries are considered impermeable, and where status relations are considered reasonably stable, individuals are predicted to engage in social creativity behaviors.

- One important factor in how symbolic boundaries function is how widely they are accepted as valid. Symbolic boundaries are a “necessary but insufficient” condition for social change.

- According to sociologists, it is “only when symbolic boundaries are widely agreed upon can they take on a constraining character… and become social boundaries. ” Thus, rituals and traditions to define boundaries are extremely influential in determining how groups interact.

- In the social sciences, the word “clique” is used to describe a group of 2 to 12 “persons who interact with each other more regularly and intensely than others in the same setting. “

Key Terms

- individual mobility

-

The ability of an individual to move from one social group to another.

- symbolic boundary

-

Conceptual distinctions made by social actors that separate people into groups and generate feelings of similarity and group membership.

Social groups are defined by boundaries. Cultural sociologists define symbolic boundaries as “conceptual distinctions made by social actors…that separate people into groups and generate feelings of similarity and group membership. ” In-groups, or social groups to which an individual feels he or she belongs as a member, and out-groups, or groups with which an individual does not identify, would be impossible without symbolic boundaries.

Permeability of Group Boundaries

The perceived permeability of group boundaries is important in determining how members define their identity . Where group boundaries are considered permeable (e.g., a group member may pass from a low status group into a high status group), individuals are more likely to engage in individual mobility strategies. That is, individuals “disassociate from the group and pursue individual goals designed to improve their personal lot rather than that of their in-group. “

Children and Marbles

Early childhood peers engaged in parallel play.

Where group boundaries are considered impermeable, and where status relations are considered reasonably stable, individuals are predicted to engage in social creativity behaviors. Here, without changing necessarily the objective resources of in the in-group or the out-group, low status in-group members are still able to increase their positive distinctiveness. This may be achieved by comparing the in-group to the out-group on some new dimension, changing the values assigned to the attributes of the group, and choosing an alternative out-group by which to compare the in-group.

Defining Boundaries

One important factor in how symbolic boundaries function is how widely they are accepted as valid. Symbolic boundaries are a “necessary but insufficient” condition for social change. According to sociologists, it is “only when symbolic boundaries are widely agreed upon can they take on a constraining character… and become social boundaries. ” Thus, rituals and traditions to define boundaries are extremely influential in determining how groups interact.

Emile Durkheim was interested in this idea. He saw the symbolic boundary between the sacred and the profane as the most profound of all social facts, and the one from which lesser symbolic boundaries were derived. Rituals, whether secular or religious, were for Durkheim the means by which groups maintained their symbolic and moral boundaries. Mary Douglas has subsequently emphasized the role of symbolic boundaries in organizing experience, private and public, even in a secular society.

6.2.2: Choosing Leaders

Leadership is the ability to organize a group of people to achieve a common purpose.

Learning Objective

Evaluate the seven types of leadership (functional, autocratic, democratic, laissez-faire, expressive, authoritarian, and toxic) arguing which one is best

Key Points

- Situational theory states that the times produce the person and not the other way around.

- Functional leadership theory argues that the leader’s main job is to see that whatever is necessary to group needs is taken care of.

- Under the autocratic leadership style, all decision-making powers are centralized in the leader.

- The democratic leadership style consists of the leader sharing the decision-making abilities with group members.

- In the laissez-faire leadership style, a person may be in a leadership position without providing leadership, leaving the group to fend for itself.

- A toxic leader is someone who leaves the group in a worse-off condition than when he or she first found them.

- A toxic leader is someone who leaves the group in a worse-off condition than when he or she first found them.

Key Terms

- leader

-

one who organizes or directs a group of people

- Toxic leadership

-

A toxic leader is someone who has responsibility over a group of people or an organization, and who abuses the leader-follower relationship by leaving the group or organization in a worse-off condition than when he/she first found them.

- Autocratic leadership

-

All decision-making powers are centralized in the leader, as with dictators.

- Trait theory of leadership

-

It is defined as integrated patterns of personal characteristics that reflect a range of individual differences and foster consistent leader effectiveness across a variety of group and organizational situations

Example

- Dictators are an example of autocratic leadership style, where all decision-making powers are centralized in the leader

Leadership is the ability to organize a group of people to achieve a common purpose. Although the leader may or may not have any formal authority, students of leadership have produced theories involving traits, situational interaction, function, behavior, power, vision and values, charisma, and intelligence, among others. A leader is somebody who people follow, somebody who guides or directs others.

Theories of Leadership

The trait theory of leadership seeks to find attributes that all leaders possess. According to researchers of leadership, all individuals can and do emerge as leaders across a variety of situations and tasks. Significant relationships exist between leadership and such individual traits as: intelligence, adjustment, extraversion, consciousness, openness to experience, and general self-efficacy.

Considering the criticisms of the trait theory outlined above, several researchers have begun to adopt a different perspective of leader individual differences–the leader attribute pattern approach. In contrast to the traditional approach, the leader attribute pattern approach is based on theorists’ arguments that the influence of individual characteristics on outcomes is best understood by considering the person as an integrated totality rather than a summation of individual variables.

Situational theory also appeared as a reaction to the trait theory of leadership. Social scientists argued that history was more than the result of intervention of great men. Herbert Spencer (1884) said that the times produce the person and not the other way around. This theory assumes that different situations call for different characteristics; according to this group of theories, no single optimal psychographic profile of a leader exists. By contrast, functional leadership theory is a particularly useful theory for addressing specific leader behaviors expected to contribute to organizational or unit effectiveness. This theory argues that the leader’s main job is to see that whatever is necessary to group needs is taken care of; thus, a leader can be said to have done their job well when they have contributed to group effectiveness and cohesion.

Styles of Leaderships

Leadership style refers to a leader’s behavior. It is the result of the philosophy, personality, and experience of the leader. Under the autocratic leadership style, all decision-making powers are centralized in the leader, as with dictators. The democratic leadership style consists of the leader sharing the decision-making abilities with group members by promoting the interests of the group members and by practicing social equality. This style of leadership works well because people feel their voice is being heard, but it can result in fighting and animosity if opinions clash and decisions can not be reached. In the laissez-faire leadership style, a person may be in a leadership position without providing leadership, leaving the group to fend for itself. Subordinates are given a free hand in deciding their own policies and methods. Expressive leaders are concerned about the emotional well-being of the group and want the group to function harmoniously. Authoritarian leaders are dictator-like; they make all the decisions for the group and have the final say, regardless of other’s feelings or opinions. Finally, someone with a toxic leadership style is a person who has responsibility over a group of people or an organization, and who abuses the leader-follower relationship by leaving the group or organization in a condition that’s worse than when he/she originally found it.

Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela, the President of South Africa from 1994 to 1999, is an example of democratic leadership.

Autocratic leadership

Benito Mussolini, a fascist dictator who ruled Italy from 1922 to 1943, is an example of autocratic leadership, where all decision-making powers were centralized on him.

6.2.3: Making Decisions

Decision-making is the mental processes resulting in the selection of a course of action among several alternative scenarios.

Learning Objective

Describe three examples of voting which can be used to come to a decision

Key Points

- Groups face unique challenges in decision-making, and as a result there are various decision-making strategies used by groups.

- Consensus decision-making requires that a majority approve a given course of action, but that the minority agrees to go along with the course of action.

- When a consensus is impossible or impractical, voting can be used to come to a decision. Range voting, majority voting, and plurality voting are three examples of this type of decision-making.

- Group polarization refers to the tendency for groups to make decisions that are more extreme than the initial inclination of its members.

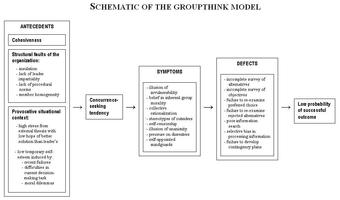

- Groupthink is the mode of thinking that happens when the desire for harmony in a decision-making group overrides a realistic appraisal of alternatives. Group members try to minimize conflict and reach a consensus decision without critical evaluation of alternative ideas or viewpoints.

- Groupthinking is the mode of thinking that happens when the desire for harmony in a decision-making group overrides a realistic appraisal of alternatives.

- Group polarization refers to the tendency for groups to make decisions that are more extreme than the initial inclination of its members.

Key Terms

- groupthink

-

A process of reasoning or decision making by a group, especially one characterized by uncritical acceptance or conformity to a perceived majority view.

- Consensus decision-making

-

It is a group decision making process that seeks the consent, not necessarily the agreement of participants and the resolution of objections.

- Group polarization

-

It refers to the tendency for groups to make decisions that are more extreme than the initial inclination of its members.

Example

- In 2009, an interesting occurrence of group polarization was found in a study conducted by Luhan, Kocher, and Sutter, in which subjects played a ‘dictator game’. In this game, both individual and group decision making was observed to see how individual preferences with respect to the allocation of money between a dictator and a recipient are transformed into a team decision. Their main finding was that team decisions were more selfish and competitive, less trusting and less altruistic than individual decisions. This study therefore offers evidence of group polarization in that the actions of individuals when in a group were more extreme than when the individual acted individually.

Decision-making is the mental process resulting in the selection of a course of action among several alternative scenarios. Every decision-making process produces a final choice. Group decision-making is the process used when individuals are brought together in a group to solve problems. According to the idea of synergy, decisions made collectively tend to be more effective than decisions made by a single individual. However, there are situations in which the decisions made by a collection of individuals are riddled with error, or poor judgment. For example, groups high in cohesion have been noted to have a negative effect on group decision making and hence on group effectiveness.

Formal Systems for Making Decisions

Consensus decision-making tries to avoid “winners” and “losers”. Consensus requires that a majority approve a given course of action, but that the minority agrees to go along with the course of action. In other words, if the minority opposes the course of action, consensus requires that the course of action be modified to remove objectionable features.

When a consensus is impossible, impractical, or undesirable, different voting systems can be used for a group to decide on an outcome. Three examples are range voting, majority voting, and plurality voting. Range voting lets each member score one or more of the available options. The option with the highest average is chosen. Majority voting requires support from more than 50% of the members of the group. Plurality voting is where the largest block in a group decides, even if it falls short of a majority.

Social Settings

Decision making in groups is sometimes examined separately as process and outcome. Groupthink is a psychological phenomenon that occurs within groups of people. It is the mode of thinking that happens when the desire for harmony in a decision-making group overrides a realistic appraisal of alternatives. Group members try to minimize conflict and reach a consensus decision without critical evaluation of alternative ideas or viewpoints.

Similarly, group polarization refers to the tendency for groups to make decisions that are more extreme than the initial inclination of its members. These more extreme decisions are towards greater risk if the individual’s initial tendency is to be risky and towards greater caution if individual’s initial tendency is to be cautious. In 2009, an interesting occurrence of group polarization was found in a study conducted by Luhan, Kocher, and Sutter, in which subjects played a ‘dictator game’. In this game, both individual and group decision-making was observed to see how individual preferences with respect to the allocation of money between a dictator and a recipient are transformed into a team decision. Their main finding was that team decisions were more selfish and competitive, less trusting and less altruistic than individual decisions. This study therefore offers evidence of group polarization, where the actions of individuals when in a group were more extreme than when the individual acted individually.

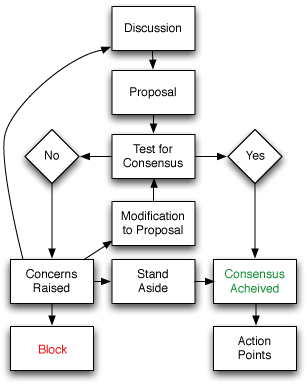

Consensus Decision-Making

This diagram shows how decisions are made by consensus. Consensus requires that a majority approve a given course of action, but that the minority agree to go along with the course of action.

6.2.4: Setting Goals

Goal setting involves establishing specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-targeted (S.M.A.R.T. ) goals.

Learning Objective

Give examples of the ways in which improving choice, effort, persistence, and cognition affect outcomes in goal-setting

Key Points

- Setting goals affects outcomes in four ways: choice, effort, persistence, and cognition. Individuals tend to exhibit more of these positive qualities when they are working toward a goal.

- The enhancement of performance through goals requires feedback. Without feedback, goal setting is unlikely to work.

- Edwin A Locke concluded that 90% of laboratory and field studies involving specific and challenging goals led to higher performance than did easy goals or no goals at all.

Key Terms

- feedback

-

Critical assessment on information produced.

- goal

-

A desired result that one works to achieve.

Examples

- Goals can increase our effort. For example, if a person typically produces four widgets an hour, and sets the goal of producing six, he may work more intensely toward the goal.

- The first empirical studies were performed by Cecil Alec Mace in 1935. Edwin A. Locke began to examine goal setting in the mid-1960s and continued researching goal setting for thirty years. Locke derived the idea for goal-setting from Aristotle’s form of final causality. Aristotle speculated that purpose can cause action; thus, Locke began researching the impact goals have on individual activity of its time performance.

Setting goals involves establishing specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-targeted (S.M.A.R.T. ) benchmarks for results. Work on the theory of goal-setting suggests that it’s an effective tool for making progress because participants in a group with a common goal are clearly aware of what is expected from them. On a personal level, setting goals helps people work toward their own objectives, which are most commonly financial or career-based goals .

Elements of Goal-Setting

Setting goals affects outcomes in four ways: by improving choice, effort, persistence, and cognition . By choice, we mean that goals narrow attention and direct efforts to goal-relevant activities, and away from perceived undesirable and goal-irrelevant actions. Secondly, goals can lead to more effort. For example, if a person typically produces four widgets an hour, and sets the goal of producing six, he may work more intensely toward the goal . Third, through improved persistence, someone becomes more prone to work through setbacks when pursuing a goal. Finally, by cognition, we mean that goals can lead individuals to develop and change their behavior.

Goal setting and achievement

Athletes set goals during the training process. Through choice, effort, persistence, and cognition, they can prepare to compete.

The enhancement of performance through goals requires feedback. Goal setting and feedback go hand in hand, for without feedback, goal setting is unlikely to work. Providing feedback on short-term objectives helps to sustain motivation and commitment to a goal. Feedback should also be provided on the strategies followed to achieve the goals and the final outcomes achieved as well. Goal-setting may have little effect if individuals can’t see the results of their performance in relation to the goal.

Studies in Goal-Setting

The first empirical studies were performed by Cecil Alec Mace in 1935. Later in the mid-1960s, Edwin A. Locke began to examine goal setting, a topic he continued to explore for thirty years. He concluded that 90% of laboratory and field studies involving specific and challenging goals led to higher performance than did easy goals or no goals at all.

6.2.5: Controlling the Behaviors of Group Members

The behavior of group members can be controlled indirectly through group polarization, groupthink, and herd behavior.

Learning Objective

Give examples of group polarization, groupthink and herd behavior in real life

Key Points

- Group polarization is the phenomenon that when placed in group situations, people will make decisions and form opinions that are more extreme than when they are in individual situations.

- Groupthink is a psychological phenomenon that occurs within groups of people. It is the mode of thinking that happens when the desire for harmony in a decision-making group overrides a realistic appraisal of alternatives.

- Herd behavior describes how individuals in a group can act together without planned direction.

- All of these phenomena show how membership in a group can overcome individual behavior.

Key Terms

- Group polarization

-

It refers to the tendency for groups to make decisions that are more extreme than the initial inclination of its members.

- herd behavior

-

The behavior exhibited by individuals in a group who act together without planned direction.

- groupthink

-

A process of reasoning or decision making by a group, especially one characterized by uncritical acceptance or conformity to a perceived majority view.

Example

- Irving Janis led the initial research on the groupthink theory. The United States Bay of Pigs Invasion was one of the primary political case studies that Janis used in explaining the theory of groupthink. The invasion plan was initiated by the Eisenhower administration, but when the Kennedy White House took over, it “uncritically accepted” the CIA’s plan. When some people attempted to present their objections to the plan, the Kennedy team as a whole ignored these objections and kept believing in the morality of their plan. Janis claimed the fiasco that ensued could have been prevented if the Kennedy administration had followed the same methods of preventing groupthink that it later followed during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Group polarization is the phenomenon that when placed in group situations, people will make decisions and form opinions that are more extreme than when they are in individual situations. The phenomenon has shown that after participating in a discussion group, members tend to advocate more extreme positions and call for riskier courses of action than individuals who did not participate in any such discussion.

The importance of group polarization is significant as it helps explain group behavior in a variety of real-life situations. Examples of these situations include public policy, terrorism, college life, and violence. For instance, group polarization can largely be seen at political conventions that are broadcasted nation wide before a large election. Generally, a political party holds the same ideals and fundamentals. At times, however, individual members of the party may waver on where they stand on smaller subjects. During a political convention, the political party as a group is strongly united in one location and is exposed to many persuasive speakers. As a result, each individual in the political party leaves more energized and steadfast on where the party as a whole stands with regards to all subjects and behind all candidates, even if they were wavering on where they stood before hand.

Groupthink

Groupthink is a psychological phenomenon that occurs within groups of people. It is the mode of thinking that happens when the desire for harmony in a decision-making group overrides a realistic appraisal of alternatives. Group members try to minimize conflict and reach a consensus decision without critical evaluation of alternative ideas or viewpoints. Irving Janis led the initial research on the groupthink theory. The United States Bay of Pigs Invasion was one of the primary political case studies that Janis used in explaining the theory of groupthink. The invasion plan was initiated by the Eisenhower administration, but when the Kennedy White House took over, it “uncritically accepted” the CIA’s plan. When some people attempted to present their objections to the plan, the Kennedy team as a whole ignored these objections and kept believing in the morality of their plan. Janis claimed the fiasco that ensued could have been prevented if the Kennedy administration had followed the same methods of preventing groupthink that it later followed during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Herd Behavior

Herd behavior describes how individuals in a group can act together without planned direction. The term pertains to the behavior of animals in herds, flocks and schools, and to human conduct during activities such as stock market bubbles and crashes, street demonstrations, sporting events, religious gatherings, episodes of mob violence and everyday decision-making, judgment and opinion-forming.

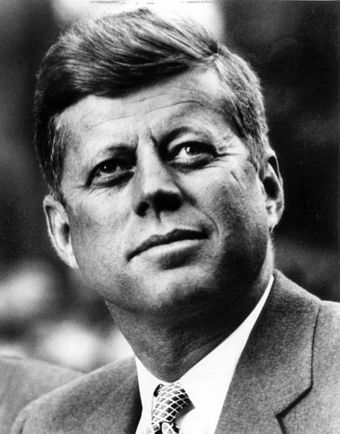

Groupthink in the Kennedy Administration

The United States Bay of Pigs Invasion, implemented by President John F. Kennedy, was one of the primary political case studies that Irving Janis used in explaining the theory of groupthink.

6.3: Large Social Groups

6.3.1: Formal Structure

Formal structure of an organization or group includes a fixed set of rules for intra-organization procedures and structures.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast formal with informal organizations

Key Points

- A formal organization has its own set of distinct characteristics, including well-defined rules and regulations, an organizational structure, and determined objectives and policies, among other characteristics.

- Formal rules are often adapted to subjective interests, giving the practical everyday life of an organization more informality.

- The deviation from rulemaking on a higher level was documented for the first time in the Hawthorne studies in 1924. This deviation was referred to as informal organization.

Key Terms

- procedure

-

A particular method for performing a task.

- Formal organization

-

It is a fixed set of rules of intra-organization procedures and structures.

Example

- The 1924 Hawthorne studies led to the Human Relations Movement—the researchers of organizational development who study the behavior of people in groups, in particular workplace groups.

What are Formal Organizations?

The formal structure of a group or organization includes a fixed set of rules of procedures and structures, usually set out in writing, with a language of rules that ostensibly leave little discretion for interpretation. In some societies and organizations, such rules may be strictly followed; in others, they may be little more than an empty formalism.

Characteristics of Formal Organization

A formal organization has its own set of distinct characteristics. These include well-defined rules and regulation, an organizational structure, and determined objectives and policies, among other characteristics.

Distinction from Informal Organization

Formal rules are often adapted to subjective interests giving the practical everyday life of an organization more informality. Practical experience shows no organization is ever completely rule-bound: all real organizations represent some mix of formal and informal characteristics. When attempting to create a formal structure for an organization, it is necessary to recognize informal organization in order to create workable structures. Tended effectively, the informal organization complements the more explicit structures, plans, and processes of the formal organization. Informal organization can accelerate and enhance responses to unanticipated events, foster innovation, enable people to solve problems that require collaboration across boundaries, and create paths where the formal organization may someday need to pave a way.

The Hawthorne Studies

The deviation from rulemaking on a higher level was documented for the first time in the Hawthorne studies in 1924. This deviation was referred to as informal organization. At first this discovery was ignored and dismissed as the product of avoidable errors, until these unwritten laws of were recognized to have more influence on the fate of the enterprise than those conceived on organizational charts of the executive level. Numerous empirical studies in sociological organization research followed, particularly during the Human Relations Movement—the researchers of organizational development who study the behavior of people in groups, in particular workplace groups.

Formal Organization

A formal organization is a fixed set of rules of intra-organization procedures and structures. As such, it is usually set out in writing, with a language of rules that ostensibly leave little discretion for interpretation.

6.3.2: Informal Structure

The informal organization is the aggregate of behaviors, interactions, norms, and personal/professional connections.

Learning Objective

Explain the function of informal groups within a formal organizational structure

Key Points

- Keith Davis suggests that informal groups serve at least four major functions within the formal organizational structure.

- Informal groups perpetuate the cultural and social values that the group holds dear.

- Informal groups provide social status and satisfaction that may not be obtained from the formal organization.

- Informal groups develop a communication channel to keep its members informed about what management actions will affect them in various ways.

- Informal groups provide social control by influencing and regulating behavior inside and outside the group.

Key Term

- Informal organizations

-

It consists of a dynamic set of personal relationships, social networks, communities of common interest, and emotional sources of motivation. The informal organization evolves organically and spontaneously in response to changes in the work environment, the flux of people through its porous boundaries, and the complex social dynamics of its members.

Examples

- Certain values are usually already held in common among informal group members. Day-to-day interaction reinforces these values that perpetuate a particular lifestyle and preserve group unity and integrity. For example, a college management class of 50 students may contain several informal groups that constitute the informal organization within the formal structure of the class.

- Certain values are usually already held in common among informal group members. Day-to-day interaction reinforces these values that perpetuate a particular lifestyle and preserve group unity and integrity. For example, a college management class of 50 students may contain several informal groups that constitute the informal organization within the formal structure of the class.

What is Informal Organization?

The informal organization is the interlocking social structure that governs how people work together in practice. It is the aggregate of behaviors, interactions, norms, and personal/professional connections through which work gets done and relationships are built among people. It consists of a dynamic set of personal relationships, social networks, communities of common interest, and emotional sources of motivation. The informal organization evolves organically in response to changes in the work environment, the flux of people through its porous boundaries, and the complex social dynamics of its members.

Key Characteristics of Informal Organizations

The nature of the informal organization becomes more distinct when its key characteristics are juxtaposed with those of the formal organization. The informal organization is characterized by constant evolution; grass roots; being dynamic and responsive; requiring insider knowledge to be seen; treating people as individuals; being flat and fluid; being cohered by trust and reciprocity; and being difficult to pin down.

Functions of Informal Organizations

Keith Davis suggests that informal groups serve at least four major functions within the formal organizational structure.

First, they perpetuate the cultural and social values that the group holds dear. Certain values are usually already commonly held among informal group members. Day-to-day interaction reinforces these values that perpetuate a particular lifestyle and preserve group unity and integrity. For example, a college management class of 50 students may contain several informal groups that constitute the informal organization within the formal structure of the class.

Second, they provide social status and satisfaction that may not be obtained from the formal organization. In a large organization, a worker may feel like an anonymous number rather than a unique individual. Members of informal groups share jokes and gripes, eat together, play and work together, and are friends—contributing to personal esteem, satisfaction, and a feeling of worth.

Third, the informal group develops a communication channel to keep its members informed about what management actions will affect them in various ways. Many astute managers use the grapevine to “informally” convey certain information about company actions and rumors.

Finally, they provide social control by influencing and regulating behavior inside and outside the group. Internal control persuades members of the group to conform to its lifestyle. For example, if a student starts to wear a coat and tie to class, informal group members may convince the student that such attire is not acceptable and therefore to return to sandals, jeans, and T-shirts.

Business Approaches

Under rapid growth business approach, Starbucks, which grew from 100 employees to over 100,000 in just over a decade, provides structures to support improvisation. Under the Learning Organization model, following a four-year study of the Toyota Production System, Steven J. Spear and H. Kent Bowen concluded in Harvard Business Review that the legendary flexibility of Toyota’s operations is due to the way the scientific method is ingrained in its workers—not through formal training or manuals but through unwritten principles that govern how workers work, interact, construct, and learn.

6.3.3: Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft

“Gemeinschaft” (community) and “Gesellschaft” (society) are concepts referring to two different forms of social organization.

Learning Objective

Explain the differences between Ferdinand Tönnies’s notions Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft

Key Points

- Gemeinschaft, often translated as “community”, is a concept referring to individuals bound together by common norms, often because of shared physical space and shared beliefs.

- Gesellschaft, often translated as “society”, refers to associations in which self-interest is the primary justification for membership.

- The equilibrium in Gemeinschaft is achieved through morals, conformism, and exclusion (social control) while Gesellschaft keeps its equilibrium through police, laws, tribunals and prisons. Rules in Gemeinschaft are implicit, while Gesellschaft has explicit rules (written laws).

- Eric Hobsbawm has argued that as globalization turns the entire planet into an increasingly remote kind of Gesellschaft,

- Fredric Jameson highlights the ambivalent envy felt by those constructed by Gessellschaft for remaining enclaves of Gemeinschaft, even as they inevitably corrode their existence.

Key Terms

- institution

-

An established organization, especially one dedicated to education, public service, culture, or the care of the destitute, poor etc.

- norm

-

A rule that is enforced by members of a community.

Example

- Familial ties represent the purest form of Gemeinschaft, although religious institutions are also a classic example of this type of group classification.

In Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft (1887), Ferdinand Tönnies set out to develop concepts that could be used as analytic tools for understanding why and how the social world is organized.

Gemeinschaft, frequently translated as “community,” refers to individuals bound together by common norms, often because of shared physical space and shared beliefs. Familial ties represent the purest form of gemeinschaft, although religious institutions are also a classic example of this type of relationship. Such groupings based on feelings of togetherness and mutual bonds are maintained by members of the group who see the existence of the group as their key goal. Characteristics of these groups include slight specialization and division of labor, strong personal relationships, and relatively simple social institutions.

Gesellschaft, frequently translated as “society,” refers to associations in which self-interest is the primary justification for membership. A modern business is a good example of an association in which individuals seek to maximize their own self-interest, and in order to do so, an association to coordinate efforts is formed. The specialization of professional roles holds them together, and often formal authority is necessary to maintain structures. Characteristics of these groups include highly calculated divisions of labor, impersonal secondary relationships, and strong social institutions. Such groups are sustained by their members’ individual aims and goals.

The equilibrium in Gemeinschaft is achieved through morals, conformism, and exclusion (social control), while Gesellschaft keeps its equilibrium through police, laws, tribunals and prisons. Amish and Hassidic communities are examples of Gemeinschaft, while state municipalities are types of Gesellschaft. Rules in Gemeinschaft are implicit, while Gesellschaft has explicit rules (written laws).

Tönnies’ distinction between Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft, like others between tradition and modernity, has been criticized for over-generalizing differences between societies, and implying that all societies were following a similar evolutionary path, which he has never proclaimed.

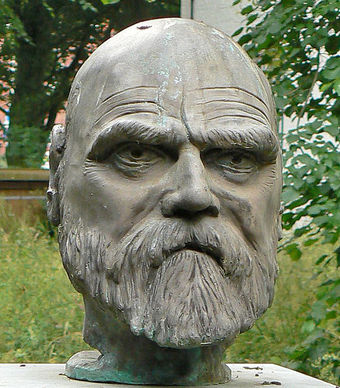

Ferdinand Toennies

In Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft (1887), Ferdinand Tönnies set out to develop the concepts Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft that could be used as analytic tools for understanding why and how the social world is organized.

6.3.4: Mechanical and Organic Solidarity

Mechanical and organic solidarity are concepts referring to different modes of establishing and maintaining social order and cohesion.

Learning Objective

Apply Durkheim’s concepts of mechanical and organic solidarity to groups in the real world

Key Points

- Social scientists have long sought to understand how and why individuals live together—especially in dense settings such as those found in urban environments.

- In The Division of Labour in Society, Emile Durkheim outlined two theories to explain how social order and solidarity are established and maintained.

- Solidarity describes connections between individuals that allows them to form a cohesive social unit. Durkheim argued solidarity is significant because it is a necessary component of a functioning civilization and a necessary component of a fulfilling human life.

- Durkheim described two forms of solidarity: mechanical and organic, roughly corresponding to smaller and larger societies.

- Mechanical solidarity refers to connection, cohesion, and integration born from homogeneity, or similar work, education, religiosity, and lifestyle. Organic solidarity is born from the interdependence of individuals in more advanced societies, particularly professional dependence.

Key Terms

- Emile Durkheim

-

David Émile Durkheim (April 15, 1858 – November 15, 1917) was a French sociologist. He formally established the academic discipline and, with Karl Marx and Max Weber, is commonly cited as the principal architect of modern social science and father of sociology.

- Collective Conscious

-

A conscience for Durkheim is preeminently the organ of sentiments and representations; it is not the rational organ that the term consciousness would imply.

- Solidarity

-

It is the integration—and degree and type of integration—shown by a society or group with people and their neighbors.

Example

- Although individuals perform very different roles in an organization, and often have different values and interests, there is a cohesion that arises from the compartmentalization and specialization woven into “modern” life. For example, farmers produce the food to feed the factory workers who produce the tractors that allow the farmer to produce the food.

Social scientists have long sought to understand how and why individuals live together—especially in dense settings such as those found in urban environments. In The Division of Labor in Society, Emile Durkheim outlined two theories that attempt to explain how social order and solidarity is established and maintained. Solidarity describes connections between individuals that allow them to form a cohesive social network. Durkheim argued solidarity is significant because it is a necessary component of a functioning civilization and a necessary component of a fulfilling human life.

Durkheim described two forms of solidarity: mechanical and organic, roughly corresponding to smaller and larger societies.

Mechanical Solidarity

Mechanical solidarity refers to connection, cohesion, and integration born from homogeneity, or similar work, education, religiosity, and lifestyle. Normally operating in small-scale “traditional” societies, mechanical solidarity often describes familial networks; it is often seen as a function of individuals being submerged in a collective consciousness. Collective consciousness is achieved when individuals begin to think and act in relatively similar ways. Though traditional small towns, familial networks, and religious congregations are often cited examples of mechanical solidarity, dispersed religious communities would also qualify if they can be said to share a collective conscience.

Organic Solidarity

Organic solidarity is born from the interdependence of individuals in more advanced societies, particularly professional dependence. Although individuals perform very different roles in an organization, and they often have different values and interests, there is a cohesion that arises from the compartmentalization and specialization woven into “modern” life. For example, farmers produce the food to feed the factory workers who produce the tractors that allow the farmer to produce the food.

6.4: Bureaucracy

6.4.1: Bureaucracies and Formal Groups

A bureaucracy is an organization of non-elected officials who implements the rules, laws, and functions of their institution.

Learning Objective

Explain the function of bureaucrats

Key Points

- A bureaucrat is a member of a bureaucracy and can comprise the administration of any organization of any size, though the term usually connotes someone within an institution of government.

- Public administration houses the implementation of government policy and an academic discipline that studies this implementation and that prepares civil servants for this work.

- Red tape is excessive regulation or rigid conformity to formal rules that is considered redundant and hinders or prevents action or decision-making. Examples include filling out paperwork, obtaining licenses, having multiple people or committees approve a decision and various low-level rules.

- Street-level bureaucracy is the subset of a public agency or government institution containing the individuals who carry out and enforce the actions required by laws and public policies.

- Street-level bureaucrats include police officers, firefighters, and other individuals, who on a daily basis interact with regular citizens and provide the force behind the given rules and laws in their areas of expertise.

Key Terms

- Public administration

-

It houses the implementation of government policy and an academic discipline that studies this implementation and that prepares civil servants for this work.

- Street-level bureaucracy

-

It is the subset of a public agency or government institution containing the individuals who carry out and enforce the actions required by laws and public policies

- red tape

-

A derisive term for regulations or bureaucratic procedures that are considered excessive or excessively time- and effort-consuming.

Example

- The European Commission has a competition that offers an award for the “Best Idea for Red Tape Reduction”. The competition is “aimed at identifying innovative suggestions for reducing unnecessary bureaucracy stemming from European law”. In 2008, the European Commission held a conference entitled ‘Cutting Red Tape for Europe’. The goal of the conference was “reducing red tape and overbearing bureaucracy” to help “business people and entrepreneurs improve competitiveness. “