16.1: Economic Systems

16.1.1: The Economy

In the most simple of terms, economies consist of producing goods and exchanging them; they are fundamentally social systems.

Key Points

- Economies can be formal or informal, and economic activity can occur in various economic systems.

- Adam Smith is credited with formalizing capitalism in his 1776 book, The Wealth of Nations.

- Capitalism results from the interaction of commodities, money, labor, means of production, and production by consumers, laborers, and investors. The government avoids significant interference in the economy— the economy relies upon the law of supply and demand.

- Socialism is another type of economic system that seriously reorients the social and political institutions associated with the economy. Socialism and communism emphasize the public ownership of the means of production and public reallocation of wealth.

- An informal economy is economic activity that is neither taxed nor monitored by a government; the terms “under the table” and “off the books” typically refer to this type of economy. Informal economic activity can be found in various economic systems.

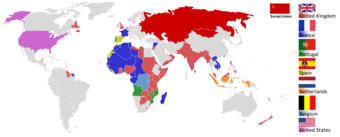

- Many European countries have robust socialist parties and policies.

Key Terms

- money

-

A generally accepted means of exchange and measure of value.

- production

-

Production is the act of creating output, a good or service which has value and contributes to the utility of individuals.

- economy

-

The system of production and distribution and consumption. The overall measure of a currency system; as the national economy.

Example

- The United States is an example of a capitalist economy. China and North Korea are examples of communist economies. France is an example of a largely socialist economy.

In the most simple of terms, economies consist of producing goods and exchanging them. Economies can be divided into formal economies and informal economies. A formal economy is the legal economy of a nation-state, as measured by a government’s gross national product (GNP), or the market value of all products and services produced by a country’s companies in a given year. Informal economies are frequently less institutionalized and include all economic practices that are neither taxed nor monitored by a government.

Economies are fundamentally social systems. They require exchanges or transactions; it is impossible for an individual to participate in an economy entirely independent of others. One cannot think of economies as discrete entities; economic systems necessarily interact with social and political systems.

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic and social system in which capital and non-labor factors of production, or the means of production, are privately controlled; labor, goods, and capital are traded in markets; profits are taken by owners or invested in technologies and industries; and wages are paid to laborers. Though capitalism has developed incrementally since the sixteenth century, Scottish philosopher and economist Adam Smith is largely credited with outlining the theory in its most fully-fledged form in his 1776 tome An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations .

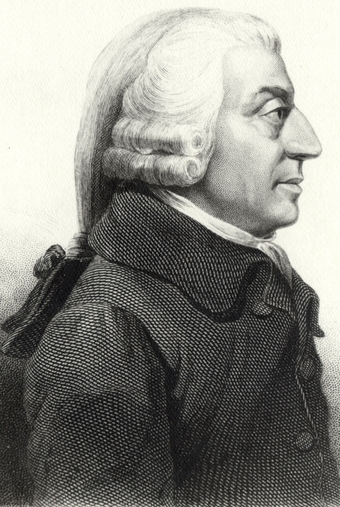

Profile of Adam Smith, by James Tassie, 1787

Author of the Wealth of Nations

The Market

A market is a central space of exchange through which people are able to buy and sell goods and services. In a capitalist economy, the prices of goods and services is mainly controlled through the principles of supply and demand and competition. “Supply and demand” refers to the balancing of the amount of a good or service produced and the amount available for sale . Prices rise when demand exceeds supply and fall when supply exceeds demand. The market coordinates itself through pricing until a new equilibrium price and quantity is reached. Competition arises when many producers are trying to sell the same or similar kinds of products to the same buyers.

The Government

Though the market is encouraged to act on its own, in any capitalist economy, the government is intimately involved in regulating the economy. This can be done through anti-trust laws or minimum wage laws. On a far more basic level, the government allows individuals to own private property and individuals to work where they please. The government generally allows businesses to set wages and prices for products without much interference. The government is responsible for issuing money, supervising public utilities, and enforcing private contracts. Laws protect competition and prohibit unfair business practices. Government agencies regulate the standards of service in many industries, such as airlines and broadcasting, and they finance a wide range of programs. Additionally, the government regulates the flow of capital and uses methods such as interest rates to control factors such as inflation and unemployment. Though the government in capitalist nations largely adheres to the basic principles of economic interference, it largely engages with the economy.

Socialism

Capitalism functions in distinction from socialism, or various theories of economic organization that advocate public or direct worker ownership and administration of the means of production. Socialism calls for public allocation of resources, creating a society characterized by equal access to resources for all individuals with a method of compensation based on the amount of labor expended. Many socialists criticize capitalism for unfairly concentrating power and wealth among a small segment of society that controls capital and derives its wealth through the exploitation of lower classes .

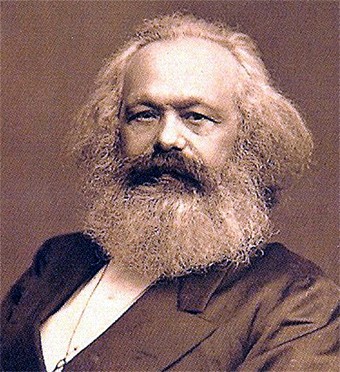

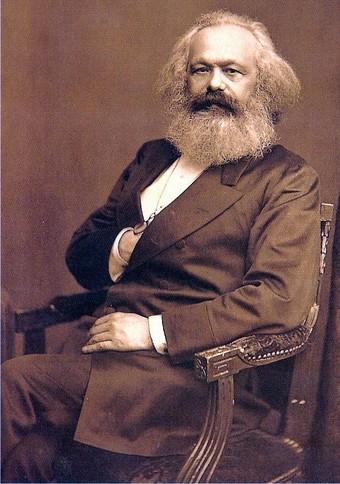

Karl Marx

Religion, Marx held, was a significant hindrance to reason, inherently masking the truth and misguiding followers.

The Informal Economy

An informal economy is economic activity that is neither taxed nor monitored by a government. Although the informal economy is often associated with developing countries, all economic systems contain an informal economy in some proportion. Informal economic activity is a dynamic process which includes many aspects of economic and social theory: exchange, regulation, and enforcement. By its nature, the informal economy is difficult to observe, study, define, and measure. The terms “under the table” and “off the books” typically refer to this type of economy, and there are various examples for this type of economic activity, including the sale and distribution of illegal drugs or unreported payments for house cleaning or baby sitting, among others.

16.1.2: Capitalism

Capitalism is a system that includes private ownership of the means of production, creation of goods for profit, competitive markets, etc.

Learning Objective

Examine the different views on capitalism (economical, political and historical) and the impact of capitalism on democracy

Key Points

- Economists usually focus on the degree that government does not have control over markets (laissez-faire), and on property rights.

- Most political economists emphasize private property, power relations, wage labor, and class and emphasize capitalism as a unique historical formation.

- Market failure occurs when an externality is present and a market will either under-produce a product with a positive externalization or overproduce a product that generates a negative externalization.

- The extension of universal adult male suffrage in 19th century Britain occurred with the development of industrial capitalism, and democracy became widespread at the same time as capitalism, leading many theorists to posit a causal relationship between them—claiming that one affects the other.

Key Terms

- voluntary exchange

-

Voluntary exchange is the act of buyers and sellers freely and willingly engaging in market transactions. Moreover, transactions are made in such a way that both the buyer and the seller are better off after the exchange than before it occurred.

- wage labor

-

The socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer, where the worker sells their labor under a formal or informal employment contract.

- externality

-

In economics, an externality, or transaction spillover, is a cost or benefit that is not transmitted through prices and is incurred by a party who was not involved as either a buyer or seller of the goods or services causing the cost or benefit.

Example

- An example of the state’s involvement in capitalist economies is the development of minimum wage laws.

Capitalism is generally considered by scholars to be an economic system that includes private ownership of the means of production, creation of goods or services for profit or income, the accumulation of capital, competitive markets, voluntary exchange, and wage labor. The designation is applied to a variety of historical cases, which vary in time, geography, politics, and culture.

Economists, political economists and historians have taken different perspectives on the analysis of capitalism. Economists usually focus on the degree that government does not have control over markets (laissez-faire economics), and on property rights. Most political economists emphasize private property, power relations, wage labor, class and capitalism’s as a unique historical formation. Capitalism is generally viewed as encouraging economic growth. The differing extents to which different markets are free, as well as the rules defining private property, are a matter of politics and policy, and many states have what are termed mixed economies. A number of political ideologies have emerged in support of various types of capitalism, the most prominent being economic liberalism.

The relationship between the state, its formal mechanisms, and capitalist societies has been debated in many fields of social and political theory, with active discussion since the 19th century. Hernando de Soto is a contemporary economist who has argued that an important characteristic of capitalism is the functioning state protection of property rights in a formal property system where ownership and transactions are clearly recorded.

The relationship between democracy and capitalism is a contentious area in theory and popular political movements. The extension of universal adult male suffrage in 19th century Britain occurred along with the development of industrial capitalism, and democracy became widespread at the same time as capitalism, leading many theorists to posit a causal relationship between them—claiming each affects the other. However, in the 20th century, capitalism also accompanied a variety of political formations quite distinct from liberal democracies, including fascist regimes, absolute monarchies, and single-party states.

16.1.3: The Marxist Critique of Capitalism

Karl Marx saw capitalism as a progressive historical stage that would eventually be followed by socialism.

Learning Objective

Examine Karl Marx’s view on capitalism and the criticisms of the capitalist system

Key Points

- Karl Marx saw capitalism as a progressive historical stage that would eventually stagnate due to internal contradictions and be followed by socialism.

- Marxists define capital as “a social, economic relation” between people (rather than between people and things). In this sense they seek to abolish capital.

- Revolutionary socialists believe that capitalism can only be overcome through revolution.

- Social democrats believe that structural change can come slowly through political reforms to capitalism.

- Marxists define capital as “a social, economic relation” between people (rather than between people and things).

- Normative Marxism advocates a revolutionary overthrow of capitalism that would lead to socialism, before eventually transforming into communism after class antagonisms and the state ceased to exist.

Key Terms

- revolution

-

A political upheaval in a government or nation-state characterized by great change.

- socialism

-

Any of various economic and political philosophies that support social equality, collective decision-making, distribution of income based on contribution and public ownership of productive capital and natural resources, as advocated by socialists.

- progressive

-

Favoring or promoting progress; advanced.

Example

- The Occupy Wall Street movement is an example of how many Americans are dissatisfied with the current capitalist system and seek more equal distribution of opportunity and goods.

Capitalism has been the subject of criticism from many perspectives during its history. Criticisms range from people who disagree with the principles of capitalism in its entirety, to those who disagree with particular outcomes of capitalism. Among those wishing to replace capitalism with a different method of production and social organization, a distinction can be made between those believing that capitalism can only be overcome with revolution (e.g., revolutionary socialism) and those believing that structural change can come slowly through political reforms to capitalism (e.g., classic social democracy).

Karl Marx saw capitalism as a progressive historical stage that would eventually stagnate due to internal contradictions and be followed by socialism. Marxists define capital as “a social, economic relation” between people (rather than between people and things). In this sense they seek to abolish capital. They believe that private ownership of the means of production enriches capitalists (owners of capital) at the expense of workers. In brief, they argue that the owners of the means of production exploit the workforce.

In Karl Marx’s view, the dynamic of capital would eventually impoverish the working class and thereby create the social conditions for a revolution. Private ownership over the means of production and distribution is seen as creating a dependence of non-owning classes on the ruling class, and ultimately as a source of restriction of human freedom.

Marxists have offered various related lines of argument claiming that capitalism is a contradiction-laden system characterized by recurring crises that have a tendency towards increasing severity. They have argued that this tendency of the system to unravel, combined with a socialization process that links workers in a worldwide market, create the objective conditions for revolutionary change. Capitalism is seen as just one stage in the evolution of the economic system.

Normative Marxism advocates for a revolutionary overthrow of capitalism that would lead to socialism, before eventually transforming into communism after class antagonisms and the state cease to exist. Marxism influenced social democratic and labor parties as well as some moderate democratic socialists, who seek change through existing democratic channels instead of revolution, and believe that capitalism should be regulated rather than abolished.

16.1.4: Socialism

Socialism is an economic system in which the means of production are socially owned and used to meet human needs, not to create profits.

Learning Objective

Discuss the various implementations of socialism, from reformism to revolutionary socialism

Key Points

- Socialists critique capitalism, arguing that it creates inequality and limits human potential. Socialists maintain that capitalism derives wealth from a system of labor exploitation and then concentrates wealth and power within a small segment of society that controls the means of production.

- As a political movement, socialism includes a diverse array of political philosophies, ranging from reformism to revolutionary socialism, from a planned economy to market socialism.

- A planned economy is a type of economy consisting of a mixture of public ownership of the means of production and the coordination of production and distribution through state planning.

- Market socialism consists of publicly owned or cooperatively owned enterprises operating in a market economy.

- Socialists argue that socialism would allow for wealth to be distributed based on how much one contributes to society, as opposed to how much capital one owns. A primary goal of socialism is social equality and a distribution of wealth based on one’s contribution to society.

Key Terms

- socialism

-

Any of various economic and political philosophies that support social equality, collective decision-making, distribution of income based on contribution and public ownership of productive capital and natural resources, as advocated by socialists.

- market socialism

-

Market socialism refers to various economic systems where the means of production are either publicly owned or cooperatively owned and operated for a profit in a market economy. The profit generated by the firms would be used to directly remunerate employees or would be the source of public finance or could be distributed among the population through a social dividend.

- planned economy

-

An economic system in which government directly manages supply and demand for goods and services by controlling production, prices, and distribution in accordance with a long-term design and schedule of objectives.

Example

- France is an example of a socialist democracy. In 2012, François Hollande democratically won the presidency on a Socialist Party ticket.

Socialism is an economic system in which the means of production are socially owned and used to meet human needs instead of to create profits. The means of production refers to the tools, technology, buildings, and other materials used to make the goods or services in an economy. Social ownership of the means of production can take many forms. It could refer to cooperative enterprises, common ownership, direct public ownership, or autonomous state enterprises. Social ownership contrasts with capitalist ownership, in which the means of production are used to create a profit. In a socialist economic system, the means of production would instead be used to directly satisfy economic demands and human needs. Accounting would be based on physical quantities or a direct measure of labor-time instead of on profits and expenses.

Although socialism is often associated with Karl Marx , it has evolved to take a variety of forms. As a political movement, socialism includes a diverse array of political philosophies, ranging from reformism to revolutionary socialism, from a planned economy to market socialism. In a planned economy, the means of production are publicly owned and the government is in charge of coordinating and distributing production. By contrast, in market socialism, the means of production may be publicly or cooperatively owned, but they operate in a market economy. That is, market socialism uses the market and monetary prices to allocate and account for the means of production and the products they create. Just like in capitalism, the means of production generate profit; however, that profit would be used to remunerate employees or finance public institutions, not to benefit private owners.

Socialists critique capitalism, arguing that it derives wealth from a system of labor exploitation and then concentrates wealth and power within a small segment of society that controls the means of production. As a result, society is stratified, split into classes according to who owns the means of production and who is forced to sell their labor; as a result, individuals do not all have the same opportunity to maximize their potential. A capitalist society, they argue, does not utilize available technology and resources to their maximum potential in the interests of the public. Instead, it focuses on satisfying market-induced wants as opposed to human needs. Socialists argue that socialism would allow for wealth to be distributed based on how much one contributes to society, as opposed to how much capital one owns. A primary goal of socialism is social equality and a distribution of wealth based on one’s contribution to society, and an economic arrangement that would serve the interests of society as a whole.

Socialism in Europe

Europe has far more socialist democracies than the United States. François Hollande won the French presidency on the Socialist Party ticket in 2012.

16.1.5: The Capitalist Critique of Socialism

Critiques of socialism generally refer to its lack of efficiency and feasibility, as well as the political/social effects of such a system.

Learning Objective

Analyze the various criticisms of socialism

Key Points

- Some critics consider socialism to be a purely theoretical concept that should be criticized on theoretical grounds; others hold that certain historical examples exist, making it possible to criticize on practical grounds.

- Some critics of socialism argue that income sharing reduces individual incentives to work; incomes should be individualized as much as possible.

- Milton Friedman, an economist, argued that socialism—which he defined as state ownership over the means of production—impedes technological progress due to stifled competition.

- The philosopher Friedrich Hayek argued that the road to socialism leads society to totalitarianism.

Key Terms

- libertarian

-

A believer in a political doctrine that emphasizes individual liberty and a lack of governmental regulation and oversight both in matters of the economy (‘free market’) and in personal behavior.

- economic liberals

-

Economic liberalism is the ideological belief in organizing the economy on individualist lines, such that the greatest possible number of economic decisions are made by private individuals and not by collective institutions.

- classical liberals

-

Classical liberals believe in classical liberalism, a political ideology developed in the 19th century that advocates limited government, constitutionalism, rule of law, due process, and individual liberties including freedom of religion, speech, press, assembly, and free markets.

Example

- Milton Friedman supported his assertion that socialism fails by taking a look at the American economy, contending that the weakest areas were those that were state-owned.

Criticism of socialism refers to a critique of socialist models of economic organization, efficiency, and feasibility, as well as the political and social implications of such a system. Some of these criticisms are not directed toward socialism as a system, but directed toward the socialist movement, socialist political parties, or existing socialist states. Some critics consider socialism to be a purely theoretical concept that should be criticized on theoretical grounds; others hold that certain historical examples exist, making it possible to criticize on practical grounds.

Economic liberals, pro-capitalist libertarians, and some classical liberals view private enterprise, private ownership of the means of production, and the market exchange as central to conceptions of freedom and liberty. Milton Friedman, an economist, argued that socialism—which he defined as state ownership over the means of production—impedes technological progress due to stifled competition . He pointed to the U.S. to see where socialism fails, observing that the most technologically backward areas are those where government owns the means of production. Some critics of socialism argue that income sharing reduces individual incentives to work; incomes should be individualized as much as possible. Critics of socialism have argued that in any society where everyone holds equal wealth there can be no material incentive to work because one does not receive rewards for a work well done.

Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman argued against the effects of socialism.

The philosopher Friedrich Hayek argued in his book The Road to Serfdom that the more even distribution of wealth through the nationalization of the means of production advocated by certain socialists cannot be achieved without a loss of political, economic, and human rights. According to Hayek, to achieve control over means of production and distribution of wealth, it is necessary for such socialists to acquire significant powers of coercion. He argued that the road to socialism leads society to totalitarianism, and that fascism and Nazism were the inevitable outcome of socialist trends in Italy and Germany during the preceding period.

Milton Friedman argued that the absence of voluntary economic activity makes it too easy for repressive political leaders to grant themselves coercive powers. Friedman’s view was shared by Friedrich Hayek and John Maynard Keynes, both of whom believed that capitalism is vital for freedom to survive and thrive.

16.1.6: Democratic Socialism

Democratic socialism combines the political philosophy of democracy with the economic philosophy of socialism.

Learning Objective

Discuss democratic socialism and how it differs from other ideas held by the government about the working class

Key Points

- Democratic socialism is contrasted with political movements that resort to authoritarian means to achieve a transition to socialism. It advocates the immediate creation of decentralized economic democracy from the grassroots level.

- Democratic socialists distinguish themselves from Leninists, who believe in an organized revolution instigated and directed by an overarching vanguard party that operates on the basis of democratic centralism.

- Eugene V. Debs, one of the most famous American socialists, led a movement centered around democratic socialism and made five bids for president.

- In Britain, the democratic socialist tradition was represented in particular by William Morris’ Socialist League and, in the 1880s, by the Fabian Society.

- In Britain, the democratic socialist tradition was represented in particular by William Morris’ Socialist League and, in the 1880s, by the Fabian Society.

Key Terms

- democratic socialism

-

A left-wing ideology that aims to introduce democracy into the workforce, i.e. worker cooperatives, and ensure public provision of basic human needs.

- Leninism

-

In Marxist philosophy, Leninism is the body of political theory for the democratic organisation of a revolutionary vanguard party, and the achievement of a direct-democracy dictatorship of the proletariat, as political prelude to the establishment of socialism.

- Fabian Society

-

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organization whose purpose is to advance the principles of democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist, rather than revolutionary, means.

Example

- France is an example of a democratic socialist state. France subscribes to a democratic structure of free elections and the country recently elected a socialist president.

Democratic socialism combines the political philosophy of democracy with the economic philosophy of socialism. The term can refer to a range of political and economic organizational schemes. On one end, democratic socialism may combine a democratic national political system with a national economy based on socialist principles. On the other end, democratic socialism may refer to a system that uses democratic principles to organize workers in a firm or community (for example, in worker cooperatives).

The term is used by socialist movements and organizations to emphasize the democratic character of their political orientation. Democratic socialism contrasts with political movements that resort to authoritarian means to achieve a transition to socialism. Rather than focus on central planning, democratic socialism advocates the immediate creation of decentralized economic democracy from the grassroots level—undertaken by and for the working class itself. Specifically, it is a term used to distinguish between socialists who favor a grassroots-level, spontaneous revolution (referred to as gradualism) from those socialists who favor Leninism (organized revolution instigated and directed by an overarching vanguard party that operates on the basis of democratic centralism).

Historical Examples

The term has also been used by various historians to describe the ideal of economic socialism in an established political democracy. Democratic socialism became a prominent movement at the end of the 19th century. In the United States, Eugene V. Debs, one of the most famous American socialists, led a movement centered around democratic socialism. Debs made five bids for president: once in 1900 as candidate of the Social Democratic Party and then four more times on the ticket of the Socialist Party of America. In Britain, the democratic socialist tradition was represented historically by William Morris’s Socialist League and, in the 1880s, by the Fabian Society.

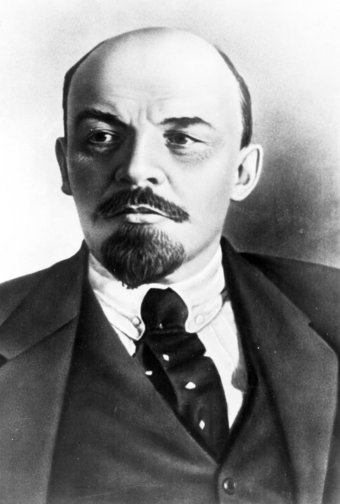

Vladimir Lenin

Leninism is based on the philosophy of Vladimir Lenin, who advocated organized revolution led by a vanguard party.

16.1.7: Informal Economy

The informal economy consists of economic activity that is neither taxed nor regulated by a government.

Learning Objective

Analyze the impact of the informal economy on formal economy, such as the black market or working “under the table”

Key Points

- Informal economies include economic practices that are not included in the calculation of GNP (the market value of all products and services produced by a country’s companies in a given year).

- Participation in the informal economy may result from lack of other options (e.g. people may buy goods on the black market because these goods are unavailable through conventional means). Participation may also be driven by a wish to avoid regulation or taxation.

- The growth of the informal economy is often attributed to changing social or economic environments. For example, with the adoption of more technologically intensive forms of production, many workers have been forced out of formal sector work and into informal employment.

- Growing regulation and taxation may also force people into the informal economy.

- The informal economy accounts for about 15 percent of employment in developed countries such as the United States.

Key Terms

- welfare capitalism

-

Welfare capitalism refers either to the combination of a capitalist economic system with a welfare state or, in the American context, to the practice of businesses providing welfare-like services to employees.

- industrial paternalism

-

Industrial paternalism is a form of welfare capitalism especially common in the United States. It refers to the practice of businesses providing welfare-like services to employees.

- Progressive Era

-

The Progressive Era in the United States was a period of social activism and political reform that flourished from the 1890s to the 1920s.

Example

- Drug dealing, babysitting, unpaid housework, and unreported self-employment are all examples of work in the informal economy.

The informal economy consists of economic activity that is neither taxed nor regulated by a government. This is in contrast to the formal economy; a formal economy includes economic activity that is legal according to national law. Formal economy goods may be taxed and are included in the calculation of a government’s gross national product (GNP), which is the market value of all products and services produced by a country’s companies in a given year. Informal economies are frequently less institutionalized and include all economic practices that are not included in the calculation of GNP. Informal economies therefore include such disparate practices as the drug trade and babysitting—anything that isn’t reported to the government or factored into the nation’s GNP . All economies have informal elements.

Drugs in the Informal Economy

Dealing drugs is an example of participation in the informal economy.

The original use of the term ‘informal sector’ is attributed to the economic development model put forward by W. Arthur Lewis, used to describe employment or livelihood creation and sustainability primarily within the developing world. It was used to describe a type of employment that was viewed as falling outside of the modern industrial sector. Participation in the informal economy may result from lack of other options (e.g. people may buy goods on the black market because these goods are unavailable through conventional means). Participation may also be driven by a wish to avoid regulation or taxation. This may manifest as unreported employment, hidden from the state for tax, social security or labor law purposes, but legal in all other aspects.

The growth of the informal economy is often attributed to changing social or economic environments. For example, with the adoption of more technologically intensive forms of production, many workers have been forced out of formal sector work and into informal employment. Arguably the most influential book on informal economy is Hernando de Soto’s The Other Path. De Soto and his team argue that excessive regulation in the Peruvian (and other Latin American) economies force a large part of the economy into informality and thus prevent economic development. In a widely cited experiment, his team tried to legally register a small garment factory in Lima. This took more than one hundred administrative steps and almost a year of full-time work. Whereas de Soto’s work is popular with policymakers and champions of free market policies, many scholars of the informal economy have criticized it both for methodological flaws and normative bias.

The informal economy accounts for about 15 percent of employment in developed countries such as the United States. By contrast, it makes up 48 percent of non-agricultural employment in North Africa, 51 percent in Latin America, 65 percent in Asia, and 72 percent in sub-Saharan Africa. If agricultural employment is included, the percentages rise—beyond 90 percent in places like India and many sub-Saharan African countries .

16.1.8: Welfare State Capitalism

Welfare capitalism refers to a welfare state in a capitalist economic system or to businesses providing welfare-like services to employees.

Learning Objective

Discuss how welfare capitalism impacts the worker and the business, in terms of costs and benefits for both

Key Points

- In the United States, the mid-twentieth century marked the height of business provisions for employees, including benefits such as more generous retirement packages and health care.

- Not all companies provided good benefits, so workers appealed to government, which imposed minimum labor standards (e.g., the minimum wage) to protect workers.

- Welfare capitalism still operates in the United States, where the government ensures minimum labor standards; some companies continue to offer benefits.

Key Terms

- welfare capitalism

-

Welfare capitalism refers either to the combination of a capitalist economic system with a welfare state or, in the American context, to the practice of businesses providing welfare-like services to employees.

- industrial paternalism

-

Industrial paternalism is a form of welfare capitalism especially common in the United States. It refers to the practice of businesses providing welfare-like services to employees.

- Progressive Era

-

The Progressive Era in the United States was a period of social activism and political reform that flourished from the 1890s to the 1920s.

Example

- Google is an example of a modern company acting under welfare capitalism in that it provides services to its employees.

Welfare capitalism refers either to the combination of a capitalist economic system with a welfare state or, in the American context, to the practice of private businesses providing welfare-like services to employees. In this second form of welfare capitalism, also known as industrial paternalism, companies have a two-fold interest in providing these services. First, the companies act in a paternalistic manner, giving employees what managers think is best for them. Second, the companies recognize that providing workers with some minor benefits can forestall complaints about larger structural issues, such as unsafe conditions and long hours.

Following this logic, in the nineteenth century, some manufacturing companies began offering new benefits for their employees. Companies sponsored sports teams, established social clubs, and provided educational and cultural activities for workers. Some companies even provided housing, such as the boarding houses provided for female employees of textile manufacturers in Lowell, Massachusetts. The mid-twentieth century marked the height of business provisions for employees, including benefits such as more generous retirement packages and health care.

However, even at the peak of this form of welfare capitalism, not all workers enjoyed the same benefits. Business-led welfare capitalism was only common in American industries that employed skilled labor. Not all companies freely choose to provide even minor benefits to workers. As workers became frustrated with meager or nonexistent benefits, they appealed to government for help, giving rise to the first form of welfare capitalism: welfare provisions provided by the state within the context of a capitalist economy. In the United States, workers formed labor unions to gain greater collective bargaining power. In addition to directly challenging businesses, they lobbied the government to enact basic standards of labor. In the United States, the first two decades of the twentieth century—the Progressive Era—saw an increase in the number of protections the government was able to extend to workers. Yet by mid-century, many of these protections had been pushed back through the court system.

Today, the government provides very basic standards by which employers must abide, such as minimum wage standards . Anything above the minimum required by the government is at the employer’s discretion. Recently, companies have begun to invest even more in the perks provided by the business in an effort to satisfy employees. Companies have found that employees make fewer demands and are more productive when they are happier, so companies such as Google have spent millions of dollars making their businesses enjoyable places to work .

16.2: The Transformation of Economic Systems

16.2.1: Preindustrial Societies: The Birth of Inequality

Pre-industrial typically have predominantly agricultural economies and limited production, division of labor, and class variation.

Learning Objective

Discuss the different types of societies and economies that existed during the pre-Industrial age

Key Points

- A hunter-gatherer society is one in which most or all food is obtained from wild plants and animals, in contrast to an agricultural society that relies mainly on domesticated species.

- Feudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the ninth and fifteenth centuries, and, broadly defined, was a system for structuring society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labor.

- Manorialism, an essential element of feudal society, was the organizing principle of rural economy that originated in the villa system of the Late Roman Empire.

Key Terms

- feudalism

-

A social system that is based on personal ownership of resources and personal fealty between a suzerain (lord) and a vassal (subject). Defining characteristics of feudalism are direct ownership of resources, personal loyalty, and a hierarchical social structure reinforced by religion.

- manorialism

-

A political, economic, and social system in medieval and early modern Europe; originally a form of serfdom but later a looser system in which land was administered via the local manor.

- pre-industrial society

-

Pre-industrial society refers to specific social attributes and forms of political and cultural organization that were prevalent before the advent of the Industrial Revolution. It is followed by the industrial society.

Example

- Medieval Europe was a pre-industrial feudal society. The economy was based mostly on agricultural production. Instead of producing crops for a market, workers exchanged the crops they grew for access to land, which was owned by a feudal lord. The economy was based on the exchange of labor for land instead of the exchange of wages for labor that is typical in industrial society.

Pre-industrial societies are societies that existed before the Industrial Revolution, which took place in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Some remote societies today may share characteristics with these historical societies, and may, therefore, also be referred to as pre-industrial. In general, pre-industrial societies share certain social attributes and forms of political and cultural organization, including limited production, a predominantly agricultural economy, limited division of labor, limited variation of social class, and parochialism at large. While pre-industrial societies share these characteristics in common, they may otherwise take on very different forms. Two specific forms of pre-industrial society are hunter-gatherer societies and feudal societies.

A hunter-gatherer society is one in which most or all food is obtained by gathering wild plants and hunting wild animals, in contrast to agricultural societies which rely mainly on domesticated species. Hunter-gatherer societies tend to be very mobile, following their food sources. They tend to have relatively non-hierarchical, egalitarian social structures, often including a high degree of gender equality. Full-time leaders, bureaucrats, or artisans are rarely supported by these societies. Hunter-gatherer group membership is often based on kinship and band (or tribe) membership. Following the invention of agriculture, hunter-gatherers in most parts of the world were displaced by farming or pastoral groups who staked out land and settled it, cultivating it or turning it into pasture for livestock. Only a few contemporary societies are classified as hunter-gatherers, and many supplement their foraging activity with farming or raising domesticated animals.

Feudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the nineteenth and fifteenth centuries. Broadly speaking, feudalism structured society around relationships based on land ownership. Feudal lords were landowners; in exchange for access to land for living and farming, serfs offered lords their service or labor. This arrangement (land access in exchange for labor) is sometimes called “manorialism,” an organizing principle of rural economy that originated in the villa system of the Late Roman Empire. Manorialism was widely practiced in medieval western and parts of central Europe, until it was slowly replaced by the advent of a money-based market economy and new forms of agrarian contract.

Feudal Manor

This painting from feudal time shows how fields surrounded the feudal manor where the noble who owned the farms lived–a good depiction of how society was oriented around the agricultural economy.

16.2.2: Industrial Societies: The Birth of the Machine

During the Industrial Revolution (roughly 1750 to 1850) changes in technology had a profound effect on social and economic conditions.

Learning Objective

Analyze the shift from manual to machine based labor during the First and Second Industrial Revolutions

Key Points

- The First Industrial Revolution, which began in the 18th century, merged into the Second Industrial Revolution around 1850.

- Great Britain provided the legal and cultural foundations that enabled entrepreneurs to pioneer the Industrial Revolution.

- Starting in the latter part of the 18th century, there began a transition in parts of Great Britain’s previously manual labor and draft-animal-based economy towards machine-based manufacturing.

- The introduction of steam power fuelled primarily by coal, wider utilization of water wheels, and powered machinery—mainly in textile manufacturing—underpinned the dramatic increases in production capacity.

- The effects spread throughout Western Europe and North America during the 19th century, eventually affecting most of the world, a process that continues as industrialization today.

Key Terms

- industrialization

-

A process of social and economic change whereby a human society is transformed from a pre-industrial to an industrial state

- Industrial Revolution

-

The major technological, socioeconomic, and cultural change in the late 18th and early 19th century, resulting from the replacement of an economy based on manual labor to one dominated by industry and machine manufacturing.

- steam power

-

Power derived from water heated into steam, usually converted to motive power by a reciprocating engine or turbine.

Example

- Examples of the technological innovation of the Industrial Revolution include the invention of steam and coal engines. These technologies enabled a reconfiguration of the economic system, as machines were now able to perform functions that previously had to be performed by people.

The Industrial Revolution was a period from 1750 to 1850 where changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times. It began in the United Kingdom, and then subsequently spread throughout Western Europe, North America, Japan, and eventually the rest of the world. The Industrial Revolution marks a major turning point in history; almost every aspect of daily life was influenced in some way. Most notably, average income and population began to exhibit unprecedented sustained growth. In the two centuries following 1800, the world’s average per capita income increased more than tenfold, while the world’s population increased over sixfold.

The First Industrial Revolution, which began in the 18th century, merged into the Second Industrial Revolution around 1850, when technological and economic progress gained momentum with the development of steam-powered ships, railways, and later in the 19th century with the internal combustion engine and electrical power generation. The period of time covered by the Industrial Revolution varies with different historians. Eric Hobsbawm held that it “broke out” in Britain in the 1780s and was not fully felt until the 1830s or 1840s, while T. S. Ashton held that it occurred roughly between 1760 and 1830.

Great Britain provided the legal and cultural foundations that enabled entrepreneurs to pioneer the Industrial Revolution. Starting in the later part of the 18th century, there began a transition in parts of Great Britain’s previously manual labor and draft-animal-based economy toward machine-based manufacturing. It started with the mechanization of the textile industries, the development of iron-making techniques and the increased use of refined coal. Trade expansion was enabled by the introduction of canals, improved roads and railways. With the transition away from an agricultural-based economy and toward machine-based manufacturing came a great influx of population from the countryside and into the towns and cities, which swelled in population.

The introduction of steam power fuelled primarily by coal, wider utilization of water wheels, and powered machinery—mainly in textile manufacturing —underpinned the dramatic increases in production capacity. The development of all-metal machine tools in the first two decades of the 19th century facilitated the manufacturing of more production machines for manufacturing in other industries. The effects spread throughout Western Europe and North America during the 19th century, eventually affecting most of the world, a process that continues as industrialization today. The impact of this change on society was enormous.

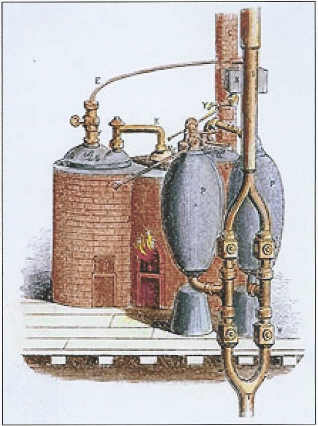

Savery Engine

The Savery Engine, invented in 1698, was one of the first steam engines available commercially. It dramatically changed how the economic system functioned.

16.2.3: Postindustrial Societies: The Birth of the Information Age

In the “Information Age,” individuals can transfer and have instant access to information, leading to a profound economic transformation.

Learning Objective

Examine the impact the Information Age has on the accessibility and breadth of information available to society

Key Points

- The Information Age formed by capitalizing on the computer microminiaturization advances, with a transition spanning from the advent of the personal computer in the late 1970s to the Internet reaching a critical mass in the early 1990s.

- Though the Internet itself has existed since 1969, it was the invention of the World Wide Web in 1989 by British scientist Tim Berners-Lee and its implementation in 1991 that allowed the Internet to truly became a global network.

- In the latter decades of the 20th century, the industrial world has been shifting into a service economy, where an increasing number of people hold jobs as clerks in stores, office workers, teachers, nurses, etc.

Key Terms

- Information Age

-

The current era, characterized by the increasing importance and availability of information (especially by means of computers), as opposed to previous eras (such as the Industrial Age) in which most endeavors related to some physical, man-made process or product.

- the internet

-

A global system of interconnected computer networks that use the standard internet protocol suite (often called TCP/IP, although not all applications use TCP) to serve billions of users worldwide. It is a network of networks that consists of millions of private, public, academic, business, and government networks, of local to global scope, that are linked by a broad array of electronic, wireless, and optical networking technologies.

- service economy

-

Service economy refers to the increased importance of the service sector compared to the manufacturing sector. The service economy in developing countries is mostly concentrated in financial services, hospitality, retail, health, human services, information technology, and education.

Example

- An example of the Information Age is how virtually every individual uses the Internet in some way at their place of work.

The Information Age is a concept that characterizes the current age by the ability of individuals to transfer information freely and have instant access to information that would have been difficult or impossible to access in the past. The idea is linked to the concept of a digital age or digital revolution, as most of this information is instantaneously available online. It carries with it the ramifications of a shift from an industrialized economy to an economy based on the manipulation of information, or an information society.

The Information Age formed by capitalizing on computer microminiaturization advances. The transition spans from the advent of the personal computer in the late 1970s to the Internet reaching a critical mass in the early 1990s, with the public’s adoption of the Internet in the two decades following 1990. The Information Age has allowed rapid global communications and networking to shape modern society due to the fast evolution of technology use in daily life.

Though the Internet itself has existed since 1969, it was the invention of the World Wide Web in 1989 by British scientist Tim Berners-Lee and its implementation in 1991 that allowed the Internet to truly became a global network. Today, the Internet has become the ultimate platform for accelerating the flow of information and is the fastest-growing form of media .

Internet Usage

This graph shows the drastic increase in Internet usage, indicative of the pervasiveness of the Information Age.

Concurrently, during the 1980s and 1990s in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Western Europe, there was a steady trend away from people holding Industrial Age manufacturing jobs. An increasing number of people held jobs as clerks in stores, office workers, teachers, nurses, etc. Many argue that jobs traditionally associated with the middle class (assembly line workers, data processors, foremen, and supervisors) are beginning to disappear, either through outsourcing or automation. Individuals who lose their jobs must either move up, joining a group of “mind workers” (engineers, attorneys, scientists, professors, executives, journalists, consultants, etc.), or settle for low-skill, low-wage service jobs.

16.2.4: Capitalism in a Global Economy

Some thinkers argue that in the last few decades trends associated with globalization have increased the mobility of people and capital.

Learning Objective

Analyze the shift in the job market and increase in international trade due to an increase in globalization

Key Points

- The world economy generally refers to the economy based on the national economies of all of the world’s countries.

- Although international trade has been associated with the development of capitalism for over five hundred years, some thinkers argue that a number of trends associated with globalization have acted to increase the mobility of people and capital since the last quarter of the 20th century.

- The global financial system is the financial system consisting of institutions and regulators that act on the international level, as opposed to those that act on a national or regional level.

- Globalization refers to the increasing global relationships of culture, people, and economic activity.

- The establishment of the WTO in 1995 led to an anti-globalization movement that was primarily concerned with the negative impact of globalization in developing countries.

- Critiques of economic globalization typically look at both the damage to the planet as well as the human costs.

Key Terms

- globalization

-

A common term for processes of international integration arising from increasing human connectivity and interchange of worldviews, products, ideas, and other cultural phenomena. In particular, advances in transportation and telecommunications infrastructure, including the rise of the Internet, represent major driving factors in globalization and precipitate the further interdependence of economic and cultural activities.

- WTO

-

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an organization that intends to supervise and liberalize international trade. It officially commenced on January 1, 1995 under the Marrakech Agreement, replacing the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which commenced in 1948. It deals with regulation of trade between participating countries and provides a framework for negotiating and formalizing trade agreements and for resolving disputes.

- global financial system

-

The global financial system is the financial system consisting of institutions and regulators that act on the international level, as opposed to those that act on a national or regional level. The main players are the global institutions, such as International Monetary Fund and Bank for International Settlements, national agencies and government departments, e.g., central banks and finance ministries, private institutions acting on the global scale, e.g., banks and hedge funds, and regional institutions, e.g., the Eurozone.

Example

- Information, goods, ideas, and cultural norms are able to spread more quickly around the world than ever before, largely due to innovations and price drops in the telecommunications industry. For example, these innovations have allowed Coca Cola to spread its goods around the world. This is an example of globalization.

The term “world economy” refers to the economic situation of all of the world’s countries. It is common to limit discussion of world economy exclusively to human economic activity. World economy is typically judged in monetary terms, even in cases in which there is no efficient market to help valuate certain goods or services, or in cases in which a lack of independent research or government cooperation makes establishing figures difficult.

The global financial system is the financial system consisting of institutions and regulators that act on the international level, as opposed to those that act on a national or regional level. The main players are global institutions, such as International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and the Bank for International Settlements; national agencies and government departments (e.g., central banks and finance ministries); private institutions acting on the global scale (e.g., banks, hedge funds), and regional institutions such as the Eurozone.

Although international trade has always existed, some thinkers argue that a number of trends associated with globalization have caused an increase in the mobility of people and capital since the last quarter of the 20th century. Today, these trends have bolstered the argument that capitalism should now be viewed as a true world system, given that all national economies trade with capitalist states and are therefore influenced by capitalist policies.

Globalization refers to the increasing global relationships of culture, people, and economic activity. It is generally used to refer to economic globalization: the global distribution of the production of goods and services, through reduction of barriers to international trade such as tariffs, export fees, and import quotas; and the reduction of restrictions on the movement of capital and on investment. Globalization may contribute to economic growth in developed and developing countries through increased specialization and the principle of comparative advantage.

Globalization

Singapore embraced globalization and became a highly developed country

16.2.5: Global Trade: Inequalities and Conflict

Global trade (exchange across international borders) has increased with better transportation and governments adopting free trade.

Learning Objective

Analyze the impact of global trade on society and industry, ranging from mercantilism to free trade orientation

Key Points

- While international trade has been present throughout much of history, its economic, social, and political importance has been on the rise in recent centuries as free trade has overtaken mercantilism and governments have reduced tariffs and other barriers to trade.

- Traditionally, trade was regulated through bilateral treaties between two nations, but it is increasingly regulated by multilateral agreements and international bodies, such as the World Trade Organization.

- Free trade is on the rise, but most countries maintain some level of protectionism in the form of subsidies or tariffs to protect industries considered essential to national security or national economies (e.g., food and steel production).

- Arguments against free trade criticize the assumptions of economic theories underlying it and its possible social and political effects, including inequality and cultural homogenization.

- In the last few decades, fair trade has been proposed as an alternative to free trade.

- Economic arguments against free trade criticize the assumptions or conclusions of economic theories.

- Sociopolitical arguments against free trade cite social and political effects that economic arguments do not capture.

- An alternative concept to free trade in the last decades has been become fair trade.

Key Terms

- free trade

-

international trade free from government interference, especially trade free from tariffs or duties on imports

- World Trade Organization

-

An international organization designed by its founders to supervise and liberalize international trade.

- protectionism

-

A policy of protecting the domestic producers of a product by imposing tariffs, quotas, or other barriers on imports.

Example

- The United States is party to many trade agreements, but one of the best known is the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Like other free trade agreements, NAFTA promotes free trade among members, which include the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

Global trade is the exchange of money, goods, and services across international borders. As transportation has improved, global trade has increased, and businesses have pressured governments to relax restrictions on trade. In most countries, global trade now accounts for many of the goods and services bought or sold, and many companies earn profits from global trade.

For centuries, governments restricted international trade based on the principles of mercantilism, which maintained that countries were all competing to maximize their stores of gold. Accordingly, governments imposed high tariffs to limit imports and promoted exports in order to sell their goods in exchange for more gold. But in the nineteenth century, especially in the United Kingdom, mercantilism gradually gave way to a belief in free trade.

Following a free trade orientation, governments do not discriminate against imports by imposing tariffs or promoting exports with subsides. Since the mid-twentieth century, nations have increasingly reduced tariff barriers and currency restrictions on international trade. But even though many countries have moved toward free trade, other trade barriers remain in place: import quotas, taxes, and diverse means of subsidizing domestic industries can all hinder trade.

As global trade has grown, governments have faced the problem of regulating trade that originates or ends outside their jurisdiction. Traditionally, governments regulated international trade through bilateral treaties that were negotiated between two nations. But as trade has become more global and more complex, trade negotiations have expanded to include more countries. Now, trade is regulated in part by worldwide agreements, such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), a multilateral agreement that went into effect in 1948. In 1995, GATT was replaced by the World Trade Organization (WTO), an international body that supervises global trade.

Most countries in the world are members of the WTO, which limits in certain ways but does not eliminate tariffs and other trade barriers. Most countries are also members of regional free trade areas that lower trade barriers among participating countries. Trade agreements are negotiated by independent nations with their own interests and values in mind, which often include values and interests other than maximum global output. As a consequence, some level of protectionism is used by almost every nation, in the form of subsidies or tariffs to protect industries a nation considers essential, such as food and steel production.

Economic arguments against free trade criticize the assumptions or conclusions of economic theories. Critics note that free trade may exacerbate inequality among countries and within them. Free trade may favor developing nations in certain areas, may benefit only the wealthy within countries, may increase offshoring, and may destabilize financial markets. Sociopolitical arguments against free trade cite social and political effects that economic arguments do not capture, such as political stability, national security, human rights, and environmental protection. Critics note that free trade undermines cultural diversity, causes dislocation and pain, and undermines national security. In response, fair trade, or an economic system that emphasizes living wages for the producers of goods, has developed as an alternative to free trade in the last several years.

Fair Trade

Fair trade products are slightly more expensive but certify that the excess cost is passed along to the workers to ensure better living and working conditions.

16.2.6: Microfinancing

Microfinance is usually understood as the provision of financial services to micro-entrepreneurs and small businesses.

Learning Objective

Examine the use of microfinance and microcredit for industry, including the benefits and criticisms

Key Points

- The modern use of the expression “microfinancing” has roots in the 1970s. At this time, organizations such as the Grameen Bank of Bangladesh, led by Muhammad Yunus, were starting to shape the modern microfinance industry.

- Microfinance is a broad category of services, one of which is microcredit. Microcredit is the provision of credit services to poor clients. Although microcredit is only one of the aspects of microfinance, conflation of the two terms is endemic in public discourse.

- An important source of detailed data on selected microfinance institutions is the MicroBanking Bulletin, which is published by Microfinance Information Exchange.

- Most criticisms of microfinance are actually just criticisms of microcredit. Other microfinance services, like savings, remittances, payments, and insurance, are rarely criticized. For example, many have criticized the high interest rates microfinance charges to borrowers.

Key Terms

- microfinance

-

finance that is provided to unemployed or low-income people or groups

- microcredit

-

the practice of making very small loans, especially to poor people to promote self-employment; microlending

- Grameen Bank

-

The Grameen Bank, a microfinance organization and community development bank started in Bangladesh, makes small loans (known as microcredit or “grameencredit) to the impoverished without requiring collateral.

Example

- The Grameen Bank is an example of a microfinance institution. Operating primarily in Bangladesh, Grameen Bank extends loans to groups of people looking to start a local service or manufacturing company.

Microfinance

In microfinance, financial services are provided to micro-entrepreneurs and small businesses, many of whom lack access to banking services because of the high transaction costs associated with serving these types of clients. There are two main mechanisms for delivering microfinance services. Relationship-based banking deals with individual entrepreneurs and individual businesses. In group-based models, several entrepreneurs unite to apply for loans and services as a group.

Microcredit

Microfinance is a broad category of services that includes microcredit. Microcredit is the provision of credit services to poor clients. Although microcredit is only one type of microfinance, conflation of the two terms is endemic in public discourse. Critics often attack microcredit while referring to it indiscriminately as either ‘microcredit’ or ‘microfinance’. Due to the broad range of microfinance services, some argue that it is difficult to objectively assess its impact. Very few studies have tried to assess its full impact, although there have been several studies that examined particular cases.

The History of Microfinance

The history of microfinance dates back to the middle of the 19th century, when Lysander Spooner, a theorist, argued that entrepreneurs and farmers could be raised out of poverty if they were given small credits. Independently of Spooner, around this time, Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen established the first cooperative lending banks to support rural German farmers.

The modern use of the term “microfinancing” dates back to 1970s. At this time, organizations such as the Grameen Bank of Bangladesh, led by Muhammad Yunus, were beginning to shape the modern microfinance industry.

An important source of detailed data on microfinance institutions is the MicroBanking Bulletin, which is published by the Microfinance Information Exchange. At the end of 2009, this organization was tracking 1,084 microfinance initiatives that were serving 74 million borrowers ($38 billion in outstanding loans) and 67 million savers ($23 billion in deposits).

Criticisms of Microfinance

Most criticisms of microfinance are actually just criticisms of microcredit. Other microfinance services, like savings, remittances, payments and insurance, are rarely criticized. For example, many people have criticized the high interest rates microfinance charges to borrowers. In 2006, in a sample of 704 microfinance institutions that voluntarily submitted reports to the MicroBanking Bulletin, the real average portfolio yield was 22.3% annually. That being said, the annual rates charged to clients were higher, because these rates included local inflation and the bad debt expenses of the microfinance institution. Recently, Muhammad Yunus has tried to react to this point. In his latest book, he argues that microfinance institutions should face penalties if they are found to be charging more than 15% above their long-term operating costs.

Community-based Savings Bank in Cambodia

This is a photograph of a community-based savings bank in Cambodia. There is a rich variety of financial institutions which serve micro-entrepreneurs and small businesses.

16.2.7: The Changing Face of the Workplace

Industry has become more information driven and less labor intensive, leading to a polarization between high- and low-skilled jobs.

Learning Objective

Examine the impact of the Information Age on the workforce, from automation to polarization

Key Points

- The Information Age has impacted the workforce in several ways. This poses problems for workers in industrial societies, which are still to be solved.

- Jobs traditionally associated with the middle class are beginning to disappear, either through outsourcing or automation.

- Individuals who lose their jobs due to automation or outsourcing must either move up, joining a group of “mind workers,” or settle for low-skill, low-wage service jobs.

- Another way the Information Age has impacted the workforce is that automation and computerization have resulted in higher productivity but that is coupled with net job loss.

- Industry is becoming more information-intensive and less labor and capital-intensive. This trend has important implications for the workforce; workers are becoming increasingly productive as the value of their labor decreases.

Key Terms

- Information Age

-

The current era, characterized by the increasing importance and availability of information (especially by means of computers), as opposed to previous eras (such as the Industrial Age) in which most endeavors related to some physical, man-made process or product.

- mind workers

-

A term for Information Age workers such as engineers, attorneys, scientists, professors, executives, journalists, and consultants.

- automation

-

The act or process of converting the controlling of a machine or device to a more automatic system, such as computer or electronic controls.

The Information Age has impacted the workforce in several ways. First, it has created a situation in which workers who perform easily automated tasks are being forced to find work that is less automated. Secondly, workers are being forced to compete in a global job market. Thirdly, workers are being replaced by computers that can do the job more effectively and faster. This poses problems for workers in industrial societies which are still to be solved. Solutions that involve having the workers work less hours are usually met with high resistance from the workers.

Jobs traditionally associated with the middle class (assembly line workers, data processors, foremen, and supervisors) are beginning to disappear, either through outsourcing or automation. Individuals who lose their jobs must either move up— joining a group of “mind workers” (engineers, attorneys, scientists, professors, executives, journalists, consultants)— or settle for low-skill, low-wage service jobs. The “mind workers” form about 20 percent of the workforce. They are able to compete successfully in the world market and command higher wages. Conversely, production workers and service workers in industrialized nations are unable to compete with workers in developing countries. They either lose their jobs through outsourcing or are forced to accept wage cuts.

There is another way in which the Information Age has impacted the workforce: automation and computerization have resulted in higher productivity . In the United States for example, from Jan 1972 to August 2010, the number of people employed in manufacturing jobs fell from 17,500,000 to 11,500,000 but manufacturing value rose 270 percent. It initially appeared that job loss in the industrial sector might be partially offset by the rapid growth of jobs in the IT sector. However, after the recession of March 2001, the number of jobs in the IT sector dropped sharply and continued to drop until 2003. Even the IT sector is not immune to this problem.

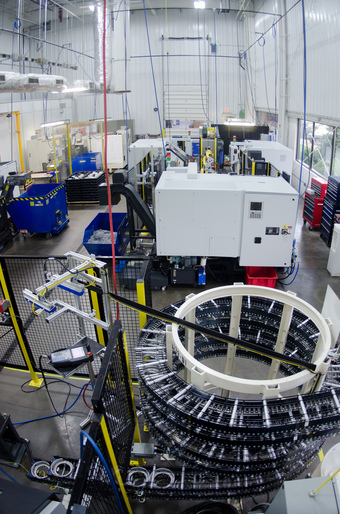

Automation

As industry has become increasingly automated, it has become more cost-effective for companies to use robot labor rather than manpower. Thus, many people lose their jobs to robots.

Industry is becoming more information-intensive and less labor and capital-intensive. This trend has important implications for the workforce; workers are becoming increasingly productive as the value of their labor decreases. However, there are also important implications for capitalism itself. Not only is the value of labor decreased, the value of capital is also diminished. In the classical model, investments in human capital and financial capital are important predictors of the performance of a new venture.

The polarization of jobs into relatively high-skill, high wage jobs and low-skill, low-wage jobs has led to a growing disparity between incomes of the rich and poor. The United States seems to have been more impacted than most countries with income inequality beginning to rise in the late 1970s, and the rate of disparity continuing to rise sharply in the twenty-first century.

16.2.8: Deindustrialization

Deindustrialization occurs when a country or region loses industrial capacity due to relocation or increased efficiency.

Learning Objective

Analyze the impact of deindustrialization on both a global and regional scale, as well as the role technology plays in deindustrialization

Key Points

- The term “deindustrialization crisis” has been used to describe the decline of manufacturing in a number of countries and the flight of jobs away from cities.

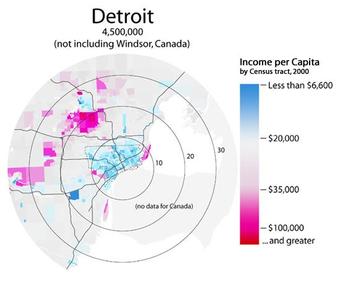

- Detroit and the American automobile industry are regarded as the prototypical examples of how deindustrialization can negatively impact an area and population. They are by no means the only examples of this phenomenon.

- In the U.S., the population of the great manufacturing cities of the Midwest and Northeast has declined significantly due to deindustrialization. Manufacturing jobs have been eliminated or relocated to the Southeast and Southwest, where labor is cheaper.

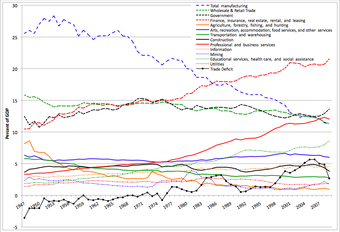

- Due to increasing efficiency and productivity, manufacturing today makes up a smaller share of the U.S. workforce than it has at any time in the past hundred years.

- The population of the great manufacturing cities of the northeast has declined significantly: Detroit, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Buffalo, NY, have all lost half their population or more in the past half-century.

- The widespread perception of deindustrialization in the United States is due to shifting patterns in the geography and political geography of production: from the heavily unionized Northeast and Midwest towards the right-to-work states of the Southeast and the high supply of workers willing to accept low wages in the Southwest.

Key Terms

- deindustrialization

-

The loss or deprivation of industrial capacity or strength.

- right-to-work states

-

Right-to-work states have passed laws that prohibit union security agreements, or agreements between labor unions and employers that govern the extent to which an established union can require employees’ membership, payment of union dues, or fees as a condition of employment, either before or after hiring. Right-to-work laws exist in twenty-three U.S. states, mostly in the southern and western United States.

- Detroit

-

the largest city and former capital of Michigan, a major port on the Detroit River, known as the traditional automotive center of the U.S.

Example

- Before the 1980s, Detroit was a center of industrial production and a hot spot of American culture. Residents enjoyed a high standard of living and the city boasted a healthy rate of population growth. But after free-trade agreements were instituted with less developed nations in the 1980s and 1990s, Detroit-based manufacturers relocated their production facilities to countries where wages were lower. At the same time, technological innovation continued to increase the efficiency of manufacturing, which required less and less manual labor. As manufacturing jobs were eliminated, people moved away from the city, and those who stayed behind found themselves with lower paying, harder to find work. Today, Detroit is associated with a high concentration of poverty, unemployment, and noticeable racial isolation.

Deindustrialization

Deindustrialization occurs when a country or region loses industrial capacity, especially heavy industry or manufacturing industry. This process is often attributed to off-shoring, which is itself a consequence of increased global free trade. Deindustrialization is, in a sense, the opposite of industrialization, and, like industrialization, deindustrialization may have far-reaching economic and social consequences. The term “deindustrialization crisis” has been used to describe the decline of manufacturing in a number of countries, including the U.S., which have lost large numbers of urban manufacturing jobs since the 1970s.

American Deindustrialization