8.1: Elections

8.1.1: Types of Elections

From the broad and general to the small and local, elections are designed to serve different purposes for various political voting systems.

Learning Objective

Identify the different types of elections in American democracy

Key Points

- In a parliamentary system, a general election is an election in which all or most members of a given political body are chosen.

- A by-election is an election held to fill a political office that has become vacant between regularly scheduled elections.

- A primary election is an election that narrows the field of candidates before the general election. Primary elections are one means by which a political party nominates candidates for the next general election.

- In the case of closed primaries, only party members can vote. By contrast, in an open primary all voters may cast votes on a ballot of any party.

- A referendum is a direct vote in which an entire electorate is asked to either accept or reject a particular proposal, usually a piece of legislation which has been passed into law by the local legislative body and signed by the pertinent executive official(s).

- A recall election is a procedure by which voters can remove an elected official from office through a direct vote before his or her term has ended.

Key Terms

- general election

-

An election, usually held at regular intervals, in which candidates are elected in all or most constituencies or electoral districts of a nation.

- referendum

-

A direct popular vote on a proposed law or constitutional amendment.

- primary election

-

A preliminary election to select a political candidate of a political party.

Example

- Political careers are often made at the local level: Boris Yeltsin, for instance, as the top official in Moscow, was able to prove his effectiveness and eventually become President of Russia after the collapse of the USSR. When he fought his first contested local election, he demonstrated a willingness to put his policies to the ballot.

Types of Elections

In a parliamentary system, a general election is an election in which all or most members of a given political body are chosen . The term is usually used to refer to elections held for a nation’s primary legislative body, as distinguished from by-elections and local elections. In this system, members of parliament are also elected to the executive branch. The party in government usually designates the leaders of the executive branch.

Afghan Elections, 2005

An Afghan man casts his ballot at a polling station in Lash Kar Gah, Helmand Province, September 18, 2005. Polling stations were busy, but orderly, across the city.

A by-election is an election held to fill a political office that has become vacant between regularly scheduled elections. Usually, a by-election occurs when the incumbent has resigned or died. Local elections vary widely across jurisdictions. In an electoral system that roughly follows the Westminster model, a terminology has evolved with roles such as mayor or warden to describe the executive of a city, town, or region, although the actual means of elections may vary. Political careers are often made at the local level: Boris Yeltsin, for instance, as the top official in Moscow, was able to prove his effectiveness and eventually become President of Russia after the collapse of the USSR. When he fought his first contested local election, he demonstrated a willingness to put his policies to the ballot.

Primary Elections

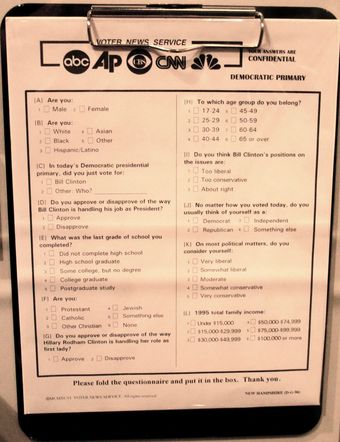

A primary election is an election that narrows the field of candidates before the general election. Primary elections are one means by which a political party nominates candidates for the next general election. Primaries are common in the United States, where their origins are traced to the progressive movement to take the power of candidate nomination away from party leaders and give it to the people. In the case of closed primaries, only party members can vote. By contrast, in an open primary all voters may cast votes on a ballot of any party. The party may require them to express their support to the party’s values and pay a small contribution to the costs of the primary.

Referendum and Recall

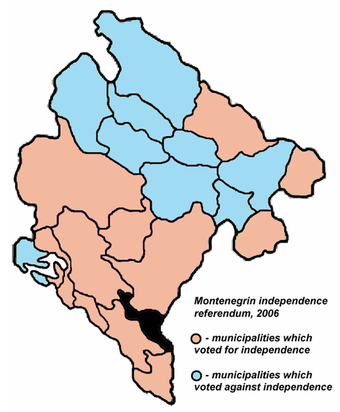

A referendum is a direct vote in which an entire electorate is asked to either accept or reject a particular proposal, usually a piece of legislation which has been passed into law by the local legislative body and signed by the pertinent executive official(s) . A referendum may result in the adoption of a new constitution, a constitutional amendment, a law, the recall of an elected official, or simply a specific government policy. Similarly, a recall election is a procedure by which voters can remove an elected official from office through a direct vote before his or her term has ended. Recalls, which are initiated when sufficient voters sign a petition, have a history dating back to the ancient Athenian democracy and are a feature of several contemporary constitutions.

Montenegro Referendum

In 2006, a referendum in the Republic of Montenegro took place.

8.1.2: The Purpose of Elections

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated since the 17th century.

Learning Objective

Discuss the nature of elections in democratic forms of government

Key Points

- An election is a formal decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual to hold public office.

- The universal use of elections as a tool for selecting representatives in modern democracies is in contrast with the practice in the democratic archetype, ancient Athens.

- Where universal suffrage exists, the right to vote is not restricted by gender, race, social status, or wealth.

- Citizens become eligible to vote after reaching the voting age, which is typically eighteen years old as of 2012 in the United States. Most democracies no longer extend different rights to vote on the basis of sex or race.

- Compulsory voting is a system in which electors are obliged to vote in elections or attend a polling place on voting day.

Key Terms

- suffrage

-

The right or chance to vote, express an opinion, or participate in a decision.

- election

-

A process of choosing a leader, members of parliament, councillors or other representatives by popular vote.

- compulsory voting

-

Compulsory voting is a system in which electors are obliged to vote in elections or attend a polling place on voting day. If an eligible voter does not attend a polling place, he or she may be subject to punitive measures, such as fines, community service, or perhaps imprisonment if fines are unpaid or community service not performed.

Example

- Suffrage is typically only for citizens of the country, though further limits may be imposed. However, in the European Union, one can vote in municipal elections if one lives in the municipality and is an EU citizen; the nationality of the country of residence is not required.

Purposes of Elections

Definition

An election is a formal decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual to hold public office. Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated since the 17th century. Elections fill offices in the legislature, sometimes in the executive and judiciary, and for regional and local government. This process is also used in many other private and business organizations, from clubs to voluntary associations and corporations.

Presidential Elections in Poland

Presidential Election 2005 in Poland (second round of voting, Oct.23rd).

History of Elections

The universal use of elections as a tool for selecting representatives in modern democracies is in contrast with the practice in the democratic archetype, ancient Athens. As the elections were considered an oligarchic institution and most political offices were filled using sortition, also known as allotment, by which officeholders were chosen by lot.

Elections were used as early in history as ancient Greece and ancient Rome, and throughout the Medieval period to select rulers such as the Holy Roman Emperor and the Pope. In ancient India, around 920 AD, in Tamil Nadu, Palm leaves were used for village assembly elections. The palm leaves with candidate names, will be put inside a mud pot, for counting. Ancient Arabs also used election to choose their caliphs, Uthman and Ali, in the early medieval Rashidun Caliphate; and to select the Pala king Gopala in early medieval Bengal.

Suffrage

The question of who may vote is a central issue in elections. The electorate does not generally include the entire population; for example, many countries prohibit those judged mentally incompetent from voting, and all jurisdictions require a minimum voting age. Suffrage is the right to vote gained through the democratic process. Citizens become eligible to vote after reaching the voting age, which is typically eighteen years old as of 2012 in the United States. Most democracies no longer extend different rights to vote on the basis of sex or race.

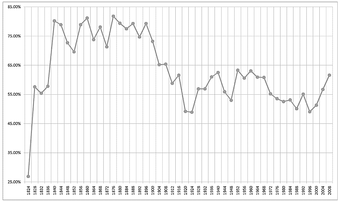

Graph of Voter Turnout in U.S. Presidential Elections, 1824-Present

Between 1824 and 1840, voter turnout when from about 26% to 80%. This extremely sharp rise was caused by the removal of property qualifications from the right to vote.

Where universal suffrage exists, the right to vote is not restricted by gender, race, social status, or wealth. It typically does not extend a right to vote to all residents of a region. Distinctions are frequently made in regard to citizenship, age, and occasionally mental capacity or criminal convictions. Suffrage is typically only for citizens of the country, though further limits may be imposed. However, in the European Union, one can vote in municipal elections if one lives in the municipality and is an EU citizen; the nationality of the country of residence is not required. In some countries, voting is required by law. If an eligible voter does not cast a vote, he or she may be subject to punitive measures such as a small fine. Compulsory voting is a system in which electors are obliged to vote in elections or attend a polling place on voting day. If an eligible voter does not attend a polling place, he or she may be subject to punitive measures such as fines, community service, or perhaps imprisonment if fines are unpaid or community service not performed.

Universal Suffrage

Suffrage universel dédié à Ledru-Rollin, painted by Frédéric Sorrieu in 1850. This lithography pays tribute to French statesman Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin for establishing universal male suffrage in France in 1848, following the French Revolution of 1848.

8.1.3: Types of Ballots

A ballot is a device used to cast votes in an election; types of ballots include secret ballots and ranked ballots.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast the different types of ballots used for elections

Key Points

- A ballot box is a temporarily sealed container with a narrow slot in the top sufficient to accept a ballot paper in an election. The ballot box is also designed to prevent anyone from accessing the votes cast until the close of the voting period.

- Ranked ballots allow voters to rank candidates in order of preference, while ballots for first-past-the-post systems only allow voters to select one candidate for each position. In party-list systems, lists may be open or closed.

- The secret ballot is a voting method in which a voter’s choices in an election or a referendum are anonymous.

- In the United States today, the term ballot reform generally refers to efforts to reduce the number of elected offices.

Key Terms

- secret ballot

-

The voting system involving ballots available only at official polling places, prepared at public expense, containing the names of all candidates, and marked in secret at the polling places.

- ballot

-

A paper or card used to cast a vote.

- ballot box

-

A sealed box with a slit, into which a voter puts his completed voting slip.

Example

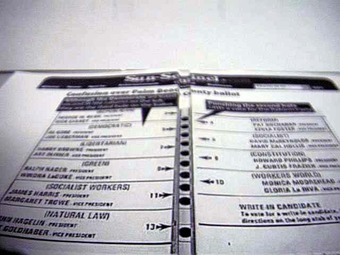

- Ballot design can aid or inhibit clarity in an election. Poor designs lead to confusion and potentially chaos if large numbers of voters spoil or mismark a ballot. The butterfly ballot used in Florida in the 2000 U.S. Presidential Election is a good example. This was a ballot paper that has names down both sides, with a single column of punch holes in the center, which has been likened to a maze. The use of a butterfly ballot led to widespread allegations of mismarked ballots.

Introduction

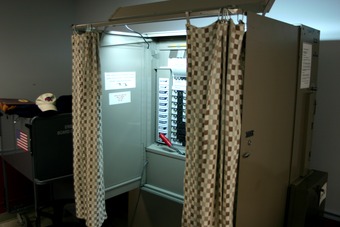

A ballot is a device used to cast votes in an election, and may be a piece of paper or a small ball used in secret voting. Each voter uses one ballot, and ballots are not shared. In the simplest elections, a ballot may be a simple scrap of paper on which each voter writes in the name of a candidate, but governmental elections use pre-printed ballots to protect the secrecy of the votes. The voter casts his or her ballot in a box at a polling station. A ballot box is a temporarily sealed container, usually square box though sometimes a tamper resistant bag, with a narrow slot in the top sufficient to accept a ballot paper in an election. The ballot box is also designed to prevent anyone from accessing the votes cast until the close of the voting period .

Haitians voting in the 2006 elections.

Clear sided ballot boxes used in the Haitian general election in 2006.

Types of Voting Systems

Depending on the type of voting system used in the election, different ballots may be used. Ranked ballots allow voters to rank candidates in order of preference, while ballots for first-past-the-post systems only allow voters to select one candidate for each position. In party-list systems, lists may be open or closed.

The secret ballot is a voting method in which a voter’s choices in an election or a referendum are anonymous. The key aim is to ensure that the voter records a sincere choice by forestalling attempts to influence the voter by intimidation or bribery. This system is one means of achieving the goal of political privacy. However, the secret ballot may increase the amount of vote buying where it is still legal. A political party or its affiliates could pay lukewarm supporters to turn out and pay lukewarm opponents to stay home, therefore reducing the costs of buying an election.

The United States uses a long and short ballot . Before the Civil War, a larger number of elected offices required longer ballots, and at times the long ballot undoubtedly resulted in confusion and blind voting, though the seriousness of either problem can be disputed. Progressivists attacked the long ballot during the Progressive Era. In the United States today, the term ballot reform generally refers to efforts to reduce the number of elected offices .

Butterfly Voters View

Perspective view of the infamous Florida butterfly ballot, reconstructed in 3-D from a reproduction in a Florida newspaper, to show how hard it is to identify which hole links to which name in “real life”, rather than the flat way it is usually displayed.

The Polling (Painting)

The Polling by William Hogarth (1755). Before the secret ballot was introduced, voter intimidation was commonplace.

8.1.4: Winning an Election: Majority, Plurality, and Proportional Representation

Common voting systems are majority rule, proportional representation, or plurality voting with a number of criteria for the winner.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast the voting systems of majority rule, proportional representation and plurality voting

Key Points

- A voting system is a method by which voters make a choice between options, often in an election or on a policy referendum.

- Majority rule is a decision rule that selections the option which has a majority, that is, more than half the votes. It is the binary decision rule used most often in influential decision-making bodies, including the legislatures of democratic nations.

- Proportional representation (PR) is a concept in voting systems used to elect an assembly or council. Proportional representation means that the number of seats won by a party or group of candidates is proportionate to the number of votes received.

- The plurality voting system is a single-winner voting system often used to elect executive officers or to elect members of a legislative assembly that is based on single-member constituencies.

Key Terms

- majority rule

-

A decision rule whereby the decisions of the numerical majority of a group will bind on the whole group.

- plurality

-

A number of votes for a single candidate or position which is greater than the number of votes gained by any other single candidate or position voted for, but which is less than a majority of valid votes cast.

- voting systems

-

A voting system is a method by which voters make a choice between options, often in an election or on a policy referendum.

Example

- The most common system, used in Canada, the lower house (Lok Sabha) in India, the United Kingdom, and most elections in the United States, is simple plurality, first-past-the-post or winner-takes-all.

Introduction

A voting system is a method by which voters make a choice between options, often in an election or on a policy referendum. A voting system contains rules for valid voting, and how votes are counted and aggregated to yield a final result. Common voting systems are majority rule, proportional representation, or plurality voting with a number of variations and methods such as first-past-the-post or preferential voting. The study of formally defined voting systems is called social choice theory, a subfield of political science, economics, and mathematics.

Majority Rule

Majority rule is a decision rule that selects the option which has a majority, that is, more than half the votes. It is the binary decision rule used most often in influential decision-making bodies, including the legislatures of democratic nations. Some scholars have recommended against the use of majority rule, at least under certain circumstances, due to an ostensible trade-off between the benefits of majority rule and other values important to a democratic society. Being a binary decision rule, majority rule has little use in public elections, with many referendums being an exception. However, it is frequently used in legislatures and other bodies in which alternatives can be considered and amended in a process of deliberation until the final version of a proposal is adopted or rejected by majority rule.

Proportional Representation

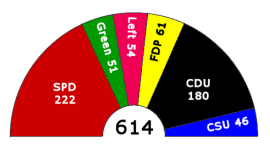

Proportional representation (PR) is a concept in voting systems used to elect an assembly or council. Proportional representation means that the number of seats won by a party or group of candidates is proportionate to the number of votes received . For example, under a PR voting system if 30% of voters support a particular party then roughly 30% of seats will be won by that party. Proportional representation is an alternative to voting systems based on single member districts or on bloc voting; these non-PR systems tend to produce disproportionate outcomes and to have a bias in favor of larger political groups. PR systems tend to produce a proliferation of political parties, while single member districts encourage a two-party system.

German federal election, 2005

Seats won by each party in the 2005 German federal election, an example of a proportional voting system.

Plurality Voting System

The plurality voting system is a single-winner voting system often used to elect executive officers or to elect members of a legislative assembly that is based on single-member constituencies . This voting method is also used in multi-member constituencies in what is referred to as an exhaustive counting system where one member is elected at a time and the process repeated until the number of vacancies is filled. In political science, the use of the plurality voting system alongside multiple, single-winner constituencies to elect a multi-member body is often referred to as single-member district plurality (SMDP).

Plurality ballot

An example of a plurality ballot.

8.1.5: Electoral Districts

An electoral district is a territorial subdivision whose members (constituents) elect one or more representatives to a legislative body.

Learning Objective

Analyze how apportionment, malapportionment and gerrymandering affect the political process

Key Points

- In an electoral district, the constituents are the voters who reside within the geographical bounds of an electoral district.

- District magnitude is the number of representatives elected from a given district to the same legislative body.

- Apportionment is the process of allocating a number of representatives to different regions, such as states or provinces, and is generally done on the basis of population. Malapportionment occurs when voters are under or over-represented due to variation in district population.

- Gerrymandering is the manipulation of electoral district boundaries for political gain.

Key Terms

- apportionment

-

The act of apportioning or the state of being apportioned

- gerrymandering

-

The practice of redrawing electoral districts to gain an electoral advantage for a political party.

- electoral district

-

A district represented by one or more elected officials.

Example

- Apportionment is generally done on the basis of population. Seats in the United States House of Representatives, for instance, are reapportioned to individual states every 10 years following a census, with some states that have grown in population gaining seats. The United States Senate, by contrast, is apportioned without regard to population; every state gets exactly two senators.

Definition

An electoral district is a distinct territorial subdivision for holding an election for one or more seats in a legislative body. Generally, only voters who reside within the geographical bounds of an electoral district, the constituents, are permitted to vote in an election held there. The term “constituency” can be used to refer to an electoral district or to the body of eligible voters within the represented area. In Australia and New Zealand, electoral districts are called “electorates,” but elsewhere the term generally refers to the body of voters.

In the United States, there are several types of districts:

- Congressional districts

- states

- state representative districts

- city council districts

An election commission is a body charged with overseeing the implementation of election procedures. The exact name used varies from country to country, including such terms as “electoral commission”, “central election commission”, “electoral branch” or “electoral court”. Election commissions can be independent, mixed, judicial or governmental. They may also be responsible for electoral boundary delimitation. In federations there may be a separate body for each subnational government. In the executive model the election commission is directed by a cabinet minister as part of the executive branch of government, and may include local government authorities acting as agents of the central body. Countries with this model include Denmark, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland, Tunisia and the United States.

District Magnitude

District magnitude is the number of representatives elected from a given district to the same legislative body. A single-member district has one representative, whereas a multi-member district has more than one. Proportional representation voting systems inherently require multi-member districts, and the larger the district magnitude the more proportional a system tends to be. Under proportional representation systems, district magnitude is an important determinant of the makeup of the elected body.

The geographic distribution of minorities also affects their representation — an unpopular nationwide minority can still secure a seat if they are concentrated in a particular district. District magnitude can vary within the same system during an election. In the Republic of Ireland, for instance, national elections to Dáil Éireann are held using a combination of 3, 4, and 5 member districts. In Hong Kong, the magnitude ranged from 3 to 5 in the 1998 election, but from 5 to 9 in the 2012.

Apportionment and Redistricting

Apportionment is the process of allocating a number of representatives to different regions, such as states or provinces. Apportionment changes are often accompanied by redistricting, the redrawing of electoral district boundaries to accommodate the new number of representatives. This redrawing is necessary under single-member district systems, as each new representative requires his or her own district.

Apportionment is generally done on the basis of population. Seats in the United States House of Representatives, for instance, are reapportioned to individual states every 10 years following a census, with some states that have grown in population gaining seats. The United States Senate, by contrast, is apportioned without regard to population; every state gets exactly two senators. Malapportionment occurs when voters are under or over-represented due to variation in district population.

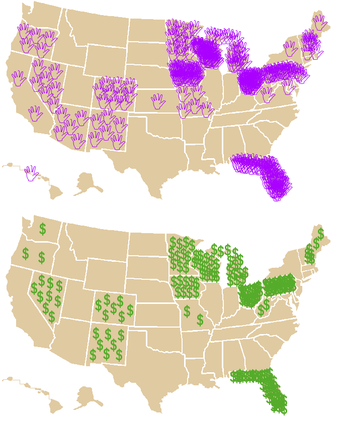

Gerrymandering is the manipulation of electoral district boundaries for political gain. By creating a few “forfeit” districts where voters vote overwhelmingly for rival candidates, gerrymandering politicians can manufacture more narrow wins among the districts they seek to win . Gerrymandering effectively concentrates wasted votes among opponents while minimizing wasted votes among supporters. Gerrymandering is typically done under voting systems with single-member districts .

Gerrymandering in Illinois

Another example of Illinois gerrymandering is the 17th congressional district in the western portion of the state. Notice how the major urban centers are anchored and how Decatur is nearly isolated from the primary district.

Gerrymandering in Ohio

An example of “cracking” style of gerrymandering. The urban (and mostly liberal) concentration of Columbus, Ohio, located at the center of the map in Franklin County, is split into thirds, with each segment attached to—and outnumbered by—largely conservative suburbs.

Swing Seats and Safe Seats

Sometimes, particularly under non-proportional winner-take-all voting systems, electoral districts can be prone to landslide victories. A safe seat is one that is very unlikely to be won by a rival politician due to the makeup of its constituency. Conversely, a swing seat is one that could easily swing either way. In United Kingdom general elections, the voting in a relatively small number of swing seats usually determines the outcome of the entire election. Many politicians aspire to have safe seats.

8.2: The Modern Political Campaign

8.2.1: Assembling a Campaign Staff

It is essential to gather a specialized and politically driven staff that helps run political campaigns in elections.

Learning Objective

Describe the organizational structure of a major modern political campaign

Key Points

- Successful campaigns usually require a campaign manager to coordinate the campaign’s operations.

- Activists are the ‘foot soldiers’ who are loyal to the cause. They are the true believers who will carry the run by volunteer activists.

- Political consultants advise campaigns on virtually all of their activities from research to field strategy.

- There are different departments created while assembling the staff in order to structure all of the campaign roles.

Key Terms

- pollster

-

A professional whose primary job is conducting pre-election polls.

- consultant

-

A person whose occupation is to be consulted for their expertise, advice, or help in an area or specialty. Alternatively, a party whose business is to be similarly consulted.

- quadrennial

-

Happening every four years.

- activist

-

A person who is politically active in the role of a citizen; especially, one who campaigns for change

Example

- In the United States larger campaigns hire consultants to serve as strategists. The campaign manager focuses mostly on coordinating the campaign staff. Campaign managers will often have deputies who oversee various aspects of the campaign at a closer level.

Organization

In a modern political campaign, the campaign organization will have a coherent structure and staff like any other large business. Political campaign staff is the people who formulate and implement the strategy needed to win an election. Many people have made careers out of working full-time for campaigns and groups that support them. However, in other campaigns much of the staff might be unpaid volunteers.

Campaign Manager

Successful campaigns usually require a campaign manager to coordinate the campaign’s operations. Apart from a candidate, the campaign manger is often a campaign’s most visible leader. Modern campaign managers may be concerned with executing strategy rather than setting it, particularly if the senior strategists are typically outside political consultants such as primarily pollsters and media consultants.

Activists

Activists are the ‘foot soldiers’ loyal to the cause. They are the true believers who will carry the run by volunteer activists. These volunteers and interns may take part in activities such as canvassing door-to-door and making phone calls on behalf of the campaign.

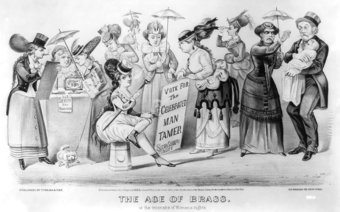

Caricature of Woman Suffrage 1869

This is a satirical caricature of the possible consequences of giving women the vote. The two candidates “Susan Sharp-tongue the Celebrated Man-Tamer” (dressed in circus-performer costume) and “Miss Hangman for Sheriff” canvass for women’s votes (in 1869 women could not vote anywhere in the United States, except as a newly-established experimental innovation in the remote territory of Wyoming). At the right, a sharp-featured woman brandishes a fist threateningly at her husband, who holds the baby. In the 1860’s chignons were a fashionable hairstyle worn by most women and often supplemented with a roll of artificial hair. The artist has caricatured this hairstyle.

Political Consultants

Political campaigns in the United States are not merely a civic ritual and an occasion for political debate. Campaigns are a multi-billion dollar industry, dominated by professional political consultants using sophisticated campaign management tools. Though the quadrennial presidential election attracts the most attention, the United States has a huge number of elected offices. There are wide variations between different states, counties, and municipalities on which offices are elected and under what procedures. Moreover, unlike democratic politics in much of the rest of the world, the U.S. has relatively weak parties. While parties play a significant role in fundraising and occasionally in drafting people to run, the individual candidates themselves ultimately control campaigns

Campaign Departments and Their Respective Purposes

The field department focuses on the “on-the-ground” organizing that is required in order to personally contact voters through canvassing, phone calls, and building local events. Voter contact helps construct and clean the campaign’s voter file in order to help better target voter persuasion and identify which voters a campaign most wants to bring out on Election Day. The field department is generally also tasked with running local “storefront” campaign offices as well as organizing phone banks and staging locations for canvasses and other campaign events.

The communications department oversees both the press relations and advertising involved in promoting the campaign in the media. They are responsible for the campaign’s message and image among the electorate. This department must approve press releases, advertisements, phone scripts, and other forms of communication before they can be released to the public.

The finance department coordinates the campaign’s fundraising operation and ensures that the campaign always has the money it needs to operate effectively. The techniques employed by this department vary based on the campaign’s needs and size. Small campaigns often involve casual fundraising events and phone calls from the candidate to donors asking for money. Larger campaigns will include everything from high-priced sit-down dinners to e-mail messages to donors asking for money.

The legal department makes sure that the campaign is in compliance with the law and files the appropriate forms with government authorities. In Britain and other Commonwealth countries, such as Canada and India, each campaign must have an official agent who is legally responsible for the campaign. The official agent is obligated to make sure the campaign follows all rules and regulations. This department will also be responsible for all financial tracking including bank reconciliations, loans, and backup for in-kind donations.

The technology department designs and maintains campaign technology such as voter file, websites, and social media. While local (county, city, town, or village) campaigns might have volunteers who know how to use computers, state and national campaigns will have information technology professionals across the state or country handling everything from websites to blogs to databases.

The scheduling and advance department makes sure that the candidate and campaign surrogates are effectively scheduled in order to maximize their impact on the voters. This department also oversees the people who arrive at events before the candidate to make sure everything is in order. Often, this department will be a part of the field department.

On small campaigns the scheduling coordinator may be responsible for developing and executing events. The scheduling coordinator typically: a) manages the candidate’s personal and campaign schedule, b) manages the field and advance team schedules, and c) gathers important information about all events the campaign and candidate will attend.

Candidates and other members of the campaign must bear in mind that only one person should oversee the details of scheduling. Fluid scheduling is one of the main components to making a profound impact on voters.

8.2.2: The Modern Political Campaign

A modern political campaign informs citizens about a political candidate running for the elected office.

Learning Objective

Identify key moments in the history of mass campaigns in the United States

Key Points

- A political campaign is an organized effort which seeks to influence the decision making process within a specific group.

- Major campaigns in the United States are often much longer than those in other democracies. Campaigns start anywhere from several months to several years before election day.

- Campaigns often dispatch volunteers into local communities to meet with voters and persuade people to support the candidate. The volunteers are also responsible for identifying supporters, recruiting them as volunteers or registering them to vote if they are not already registered.

- Campaign finance in the United States is the financing of electoral campaigns at the federal, state, and local levels. At the federal level, campaign finance law is enacted by Congress and enforced by the Federal Election Commission (FEC), an independent federal agency.

- The internet is now a core element of modern political campaigns. Communication technologies such as e-mail, web sites, and podcasts for various forms of activism to enable faster communications by citizen movements and deliver a message to a large audience.

Key Terms

- lobby groups

-

The act of attempting to persuade a group of people that influence decisions made by officials in the government, most often legislators or members of regulatory agencies.

- referendum

-

A direct popular vote on a proposed law or constitutional amendment.

- political campaign

-

It is an organized effort which seeks to influence the decision making process within a specific group.

- political action committee

-

A political action committee (PAC) is any organization in the United States that campaigns for or against political candidates, ballot initiatives, or legislation.

Example

- Signifying the importance of internet political campaigning, Barack Obama’s presidential campaign relied heavily on social media, and new media channels to engage voters, recruit campaign volunteers, and raise campaign funds. The campaign brought the spotlight on the importance of using internet in new-age political campaigning by utilizing various forms of social media and new media (including Facebook, YouTube and a custom generated social engine) to reach new target populations. The campaign’s social website, my.BarackObama.com, utilized a low cost and efficient method of mobilizing voters and increasing participation among various voter populations. This new media was incredibly successful at reaching the younger population while helping all populations organize and promote action.

Introduction

A political campaign is an organized effort which seeks to influence the decision making process within a specific group. In democracies, political campaigns often refer to electoral campaigns, where representatives are chosen or referendums are decided . In modern politics, the most high profile political campaigns are focused on candidates for head of state or head of government, often a President or Prime Minister.

Candidate for Congress

Walter Faulkner, candidate for U.S. Congress, campaigning with a Tennessee farmer. Crossville, Tennessee.

Background History

Political campaigns have existed as long as there have been informed citizens. The phenomenon of political campaigns are tightly tied to lobby groups and political parties. The first modern campaign is thought to be William Ewart Gladstone’s Midlothian campaign in the 1880’s, although there may have been earlier modern examples from the 19th century. American election campaigns in the 19th century created the first mass-base political parties and invented many of the techniques of mass campaigning.

Process of Campaigning

Major campaigns in the United States are often much longer than those in other democracies. Campaigns start anywhere from several months to several years before election day. Once a person decides to run, they will make a public announcement. This announcement could consist of anything from a simple press release to concerned media outlets to a major media event followed by a speaking tour. It is often well-known to many people that a candidate will run prior to an announcement being made .

John Edwards Pittsburgh 2007

2008 United States Presidential candidate John Edwards campaigning in Pittsburgh on Labor day in 2007, accepting the endorsement of the United Steelworkers and the United Mine Workers of America.

Campaigns often dispatch volunteers into local communities to meet with voters and persuade people to support the candidate. The volunteers are also responsible for identifying supporters, recruiting them as volunteers or registering them to vote if they are not already registered. The identification of supporters will be useful later as campaigns remind voters to cast their votes . Late in the campaign, campaigns will launch expensive television, radio, and direct mail campaigns aimed at persuading voters to support the candidate. Campaigns will also intensify their grassroots campaigns, coordinating their volunteers in a full court effort to win votes.

Nixon Meets Crowds at Robins Air Force Base in Georgia

President Nixon “works the crowd” at Robins Air Force Base, Georgia in the initial stages of his campaign.

Campaign Finance in the United States

Campaign finance in the United States is the financing of electoral campaigns at the federal, state, and local levels. At the federal level, campaign finance law is enacted by Congress and enforced by the Federal Election Commission (FEC), an independent federal agency. Although most campaign spending is privately financed, public financing is available for qualifying candidates for President of the United States during both the primaries and the general election. Eligibility requirements must be fulfilled to qualify for a government subsidy, and those that do accept government funding are usually subject to spending limits.

In 2008—the last presidential election year—candidates for office, political parties, and independent groups spent a total of $5.3 billion on federal elections. The amount spent on the presidential race alone was $2.4 billion, and over $1 billion of that was spent by the campaigns of the two major candidates: Barack Obama spent $730 million in his election campaign, and John McCain spent $333 million. The total spent on federal elections in 2012 was approximately $7 billion. The figures for the 2016 election will not be available until 2017.

Techniques

A campaign team must consider how to communicate the message of the campaign, recruit volunteers, and raise money. Campaign advertising draws on techniques from commercial advertising and propaganda. The avenues available to political campaigns when distributing their messages is limited by the law, available resources, and the imagination of the campaigns’ participants. These techniques are often combined into a formal strategy known as the campaign plan. The plan takes account of a campaign’s goal, message, target audience, and resources available. The campaign will typically seek to identify supporters at the same time as getting its message across.

Modern Technology and the Internet

The internet is now a core element of modern political campaigns. Communication technologies such as e-mail, web sites, and podcasts for various forms of activism to enable faster communications by citizen movements and deliver a message to a large audience. These Internet technologies are used for cause-related fundraising, lobbying, volunteering, community building, and organizing. Individual political candidates are also using the internet to promote their election campaign.

Signifying the importance of internet political campaigning, Barack Obama’s presidential campaign relied heavily on social media, and new media channels to engage voters, recruit campaign volunteers, and raise campaign funds. The campaign brought the spotlight on the importance of using internet in new-age political campaigning by utilizing various forms of social media and new media (including Facebook, YouTube and a custom generated social engine) to reach new target populations. The campaign’s social website, my.BarackObama.com, utilized a low cost and efficient method of mobilizing voters and increasing participation among various voter populations. This new media was incredibly successful at reaching the younger population while helping all populations organize and promote action.

8.2.3: The Nomination Campaign

In the nomination campaign, Presidential candidates are selected based on the primaries to run in the main election.

Learning Objective

Describe the procedure by which the Electoral College indirectly elects the President

Key Points

- The modern Presidential campaign begins before the primary elections.

- Nominees campaign across the country to explain their views, convince voters and solicit contributions.

- Much of the modern electoral process is concerned with winning swing states through frequent visits and mass media advertising drives.

Key Terms

- Twentieth Amendment

-

This amendment establishes the beginning and ending of the terms of the elected federal offices.

- vice president

-

A deputy to a president, often empowered to assume the position of president on his death or absence

- electoral college

-

A body of electors empowered to elect someone to a particular office

Example

- A United States presidential nominating convention is a political convention held every four years in the United States by most of the political parties who will be fielding nominees in the upcoming U.S. presidential election.

Modern Presidential Campaign and Nomination

The modern presidential campaign begins before the primary elections. The two major political parties try to clear the field of candidates before their national nominating conventions, where the most successful candidate is made the party’s nominee for president. Typically, the party’s presidential candidate chooses a vice presidential nominee, and this choice is then rubber-stamped by the convention.

Nominees participate in nationally televised debates. While the debates are usually restricted to the Democratic and Republican nominees, third party candidates may be invited, such as Ross Perot in the 1992 debates. Nominees also campaign across the country to explain their views, convince voters and solicit contributions. Much of the modern electoral process is concerned with winning “swing states” through frequent visits and mass media advertising drives.

Election and oath

Presidents are elected indirectly in the United States. A number of electors, collectively known as the Electoral College, officially select the president. On Election Day, voters in each of the states and the District of Columbia cast ballots for these electors. Each state is allocated a number of electors, equal to the size of its delegation in both Houses of Congress combined. Generally, the ticket that wins the most votes in a state wins all of that state’s electoral votes, and thus has its slate of electors chosen to vote in the Electoral College.

The winning slate of electors meet at its state’s capital on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December, about six weeks after the election, to vote. They then send a record of that vote to Congress. The vote of the electors is opened by the sitting vice president, acting in his capacity as President of the Senate, and is read aloud to a joint session of the incoming Congress, which is elected at the same time as the President.

Electoral College

Electoral college map for the 2012, 2016 and 2020 United States presidential elections, using apportionment data released by the US Census Bureau.

Pursuant to the Twentieth Amendment, the President’s term of office begins at noon on January 20 of the year following the election. This date, known as Inauguration Day, marks the beginning of the four-year term of both the President and the vice president. Before executing the powers of the office, a President is constitutionally required to take the presidential oath.

8.2.4: The General Election Campaign

In the U.S., general election campaigns promote presidential candidates running for different parties.

Learning Objective

Identify the features that distinguish American elections from those in other democracies

Key Points

- In U.S. politics, general elections occur every four years and include the presidential election.

- One of the most important aspects of the major American political campaign is the ability to raise large sums of money, especially early on in the race.

- Campaigns often dispatch volunteers into local communities to meet with voters and persuade people to support the candidate.

Key Terms

- general elections

-

In the United States, these regulation elections of candidates occur every four years and include the presidential election.

- campaign

-

An organized effort to influence the decision making process within a specific group when seeking election to political office.

- partisan

-

An adherent to a party or faction.

Example

- In general elections citizens can actively participate in campaigning for their preferred political party. Citizens can act as volunteers who are also responsible for identifying supporters, recruiting them as volunteers, or registering them to vote if they are not already registered. The identification of supporters is useful later on during campaigns when voters are reminded to cast their votes.

General Elections in the United States

In presidential systems, a general election refers to a regularly scheduled election, where both the president, and either “a class” of or all members of the national legislature are elected at the same time. A general election day may also include elections for local officials.

In U.S. politics, general elections occur every four years and include the presidential election. Some parallels can be drawn between the general election in parliamentary systems and the biennial elections determining all House seats. There is no analogue to “calling early elections” in the U.S., however, and the members of the elected U.S. Senate face elections of only one-third at a time at two year intervals including during a general election.

Types of Elections

The United States is unusual in that dozens of different offices are filled by election, from drain commissioner to the President of the United States. Elections happen every year, on many different dates, and in many different areas of the country.

All federal elections including elections for the President and the Vice President, as well as elections to the House of Representatives and Senate, are partisan. Elections to most but not all statewide offices are partisan-oriented, and all state legislatures except for Nebraska are partisan-oriented.

Some state and local offices are non-partisan, these often include judicial elections, special district elections (the most common of which are elections to the school board, and elections to municipal (town council, city commission, mayor) and county (county commission, district attorney, sheriff) office. In some cases, candidates of the same political party challenge each other. Additionally, in many cases there are no campaign references to political parties, but sometimes even non-partisan races take on partisan overtones.

Process of Campaigning

Major campaigns in the United States are often much longer than those in other democracies. The first part of any campaign is for a candidate to decide to run in elections. Prospective candidates will often speak with family, friends, professional associates, elected officials, community leaders, and the leaders of political parties before deciding to run. Candidates are often recruited by political parties and lobby groups interested in electing like-minded politicians. During this period, people considering running for office will consider their ability to put together the money, organization, and public image needed to get elected. Many campaigns for major office do not progress past this point, as people often do not feel confident in their ability to win. However, some candidates lacking the resources needed for a competitive campaign proceed with an inexpensive paper campaign or informational campaign designed to raise public awareness and support for their positions.

Nixon Meets Crowds at Robins Air Force Base in Georgia

President Nixon “works the crowd” at Robins Air Force Base, Georgia in the initial stages of his campaign.

Once a person decides to run, they make a public announcement. This announcement consists of anything from a simple press release, to concerned media outlets, or a major media event followed by a speaking tour.

Funding for Campaigns

One of the most important aspects of the major American political campaign is the ability to raise large sums of money, especially early on in the race. Political insiders and donors often judge candidates based on their ability to raise money. Not raising enough money early on can lead to problems later as donors are not willing to give funds to candidates they perceive to be losing, a perception based on their poor fundraising performance.

Also during this period, candidates travel around the area they are running in and meet with voters; speaking to them in large crowds, small groups, or even one-on-one. This allows voters to get a better sense of who a candidate is, rather than just relying on what they read about in the paper or see on television.

Campaigns often dispatch volunteers into local communities to meet with voters and persuade people to support the candidate. The volunteers are also responsible for identifying supporters, recruiting them as volunteers or registering them to vote if they are not already registered. The identification of supporters is useful later, as campaigns remind voters to cast their votes.

Late in the campaign, campaigns will launch expensive television, radio, and direct mail campaigns aimed at persuading voters to support their candidate. Campaigns will also intensify their grassroots campaigns, coordinating their volunteers in a full court effort to win votes.

8.3: Political Candidates

8.3.1: Eligibility

Eligibility requirements restrict who can run for a given public office.

Learning Objective

Give examples of eligibility requirements for various offices

Key Points

- Virtually all electoral systems have some eligibility requirements, such as a minimum age to run for office.

- Even within a single jurisdiction, eligibility requirements may vary by office; there are more stringent restrictions on who can run for president than on who can run for Senate in the U.S.

- The natural born citizen clause places a Constitutional limitation on who can run for president in the U.S., limiting the office to natural born citizens.

Key Terms

- eligibility requirement

-

Statutory restrictions on who is entitled to hold a given public office.

- natural born citizen

-

Any person who is entitled to American citizenship by birth.

Example

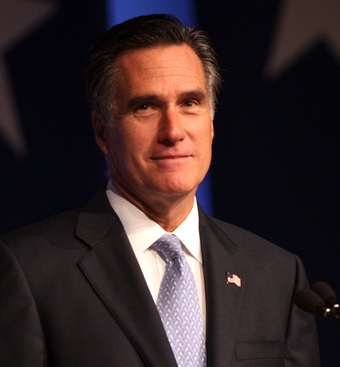

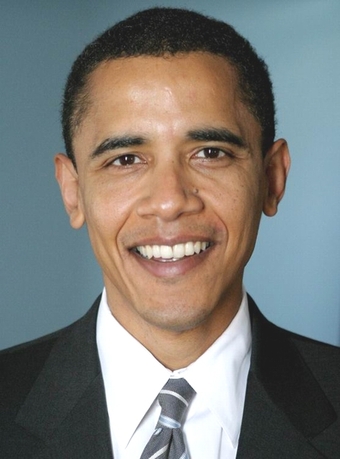

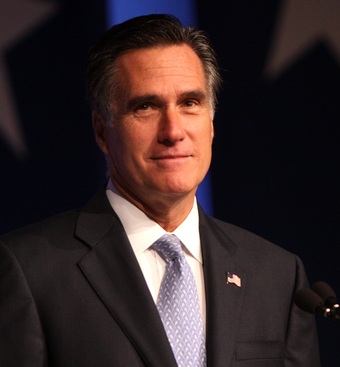

- The controversial “birther” movement that has questioned the validity of President Obama’s American birth certificate is an example of debate involving the natural born citizenship clause. Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney was born in Mexico to American parents, illustrating that natural born citizenship does not depend on place of birth, but rather whether one is entitled to citizenship at birth.

Different voting jurisdictions set different eligibility requirements for candidates to run for office. In partisan election systems, such as those in place for U.S. Presidential and Congressional elections, the only people eligible to run in a general election are those nominated by a political party or who have successfully petitioned to be on the ballot. In non-partisan elections, there may be fewer restrictions on those who can be listed on a ballot, with no requirements for party or popular support.

Virtually all electoral systems, whether partisan or non-partisan, have some minimum eligibility requirements to run for office. For example, candidates are generally required to be a certain age. In some jurisdictions, individuals may be eligible to campaign when they reach the age of legal majority, which is often 18. Elsewhere, candidates may need to be older; for example, in U.S. Presidential campaigns, candidates must be at least 35 years old.

Eligibility requirements may also vary by political office within a given jurisdiction. The President of the U.S. must be a natural-born citizen, due to the natural-born citizenship clause of the U.S. Constitution . There has been some legal debate over what constitutes natural born citizenship, particularly regarding cases where an individual is born outside the U.S. to American citizens or in cases of adoption. Generally, however, natural born citizenship is understood to include anyone who is entitled to U.S. citizenship at birth, even if they are born outside of the U.S. Over the years, multiple presidential candidates have been born in foreign countries or U.S. territories, but have met the natural born citizenship eligibility requirement because they were born to American citizens.

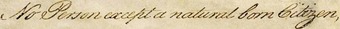

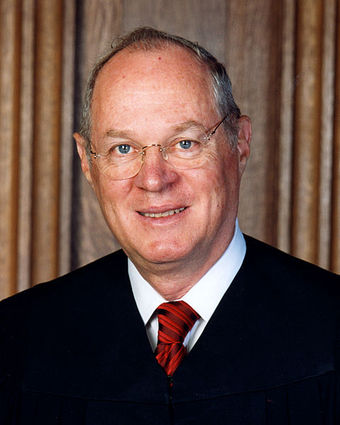

Natural Born Citizen Clause

The U.S. Constitution limits eligibility for the office of president to individuals who are natural born citizens of the U.S.

In offices other than that of the President, eligibility requirements tend to be less stringent. For example, according to the Constitution, members of the U.S. House of Representatives must be over the age of 25 and an American citizen for at least seven years. The Senate’s minimum age requirement is 30 and nine years an American citizen. Both chambers of Congress require members to be residents of the state they seek to represent. House members are not required to live in their districts. For local offices, the requirements are often even less strict — in certain jurisdictions, local officials simply need to be current citizens over the age of 18 who have established local residency.

8.3.2: Nominating Candidates

Nomination is the process through which political candidates are chose to campaign for election to office.

Learning Objective

Describe the steps by which a candidate appears on the ballot in a general election

Key Points

- In representative democracies, candidates are nominated to run for office and then are placed on a ballot to seek election.

- In the United States, political parties are largely responsible for nominating candidates.

- In contested elections, candidates participate in primary elections to become their party’s nominee in the general election.

Key Terms

- political party

-

A political organization that subscribes to a certain ideology and seeks to attain political power through representation in government.

- primary election

-

A preliminary election to select a political candidate of a political party.

- nominating convention

-

A meeting of the major figures in a political party to outline a party platform, set party rules, select a nominee for president as well as rally supporters.

Example

- In the 2012 U.S. presidential election, Mitt Romney was the Republican Party’s presumptive nominee before the party’s national convention; he was not officially nominated by the party, but because he had won the party’s primary election, the official nomination at the convention was a mere formality.

Nomination is part of the process of selecting a candidate for election to office. In a representative democracy, such as the United States, citizens vote to elect individuals to public offices. Examples of elected officials include at the federal level, the president; at the state level, a state representative; and at the local level, a city council member. In order to have their names listed on election ballots, individuals seeking these offices must first be nominated.

In the United States, nominees are often chosen by political parties. Political parties are organizations that subscribe to a certain ideology, articulated in the party’s platform, and that seek to attain political power through representation in government. The two largest political parties in the United States are the Democratic Party and the Republican Party, but there also are smaller parties, such as the Libertarian Party and the Green Party. To nominate candidates, political parties hold primary elections. Primary elections are used to narrow the field of candidates for the general election. In a primary, several members of the same political party campaign to become their party’s nominee in the general election. In the general election, nominees from each party compete against each other to be elected to office.

In order to formally select candidates for a presidential election, American political parties hold nominating conventions . The official purpose of these conventions is to select the party’s nominee for president, as well as to adopt a statement of party principles and goals, known as the platform. In modern presidential campaigns, however, nominating conventions are largely ceremonial. Due to changes in election laws, the primary and caucus calendar, and the manner in which political campaigns are run, parties enter their conventions with presumptive nominees. During primary campaigns, state delegates are assigned to a primary candidate based on the outcome of a statewide vote. Whichever primary candidate emerges from the primary election with the most delegates becomes the party’s presumptive nominee. The presumptive nominee is not formally nominated until the national convention, but he or she is all but assured of a place on the ballot in the general election by the conclusion of the primary season.

2008 Democratic National Convention

Modern nominating conventions are largely ceremonial affairs, intended to strengthen party support of its presumptive nominee.

When candidates for national, state, or local office are not affiliated with a political party, they may be nominated as candidates if they receive a sufficient number of signatures from eligible voters (though the specific requirements vary by voting jurisdiction). In a case where an independent, or unaffiliated, candidate receives sufficient signatures, his or her name will appear on the ballot in the general election. These candidates do not need to participate in primary elections, since they are not seeking the nomination of a political party.

8.3.3: Electing Candidates

An election is a decision-making process used in a democracy to choose public office holders based on a vote.

Learning Objective

Define the electorate

Key Points

- Modern representative democracies use elections to determine a range of national, state, and local officials.

- Voting jurisdictions use different electoral systems to determine the outcome of elections, which may result in political parties receiving either a proportion of open seats or total control of a governmental body.

- The electorate is the group of eligible voters in an election, and may be limited by restrictions such as citizenship or residency requirements, age requirements, or property-owning requirements.

Key Terms

- electorate

-

The collective people of a country, state, or electoral district who are entitled to vote.

- election

-

A process of choosing a leader, members of parliament, councillors or other representatives by popular vote.

- electoral system

-

The detailed constitutional arrangements and voting laws that convert the vote into a political decision.

An election is a formal decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual to hold public office. Generally, elections consist of voters casting ballots at polling places on a scheduled election day . Elections have been the usual mechanism by which representative democracies have operated since the 17th century. Elections may fill offices in the legislature, the executive and judiciary, and regional and local government.

Casting a Ballot

Many electoral systems require voters to cast ballots at official, regulated polling places.

Electoral systems are the detailed constitutional arrangements and voting laws that convert the vote into a political decision. The first step in determining the results of an election is to tally the votes, for which various vote counting systems and ballot types are used. Electoral systems then determine the result of the election on the basis of the tally. Most electoral systems can be categorized as either proportional or majoritarian. In a proportional electoral system, a political party receives a percentage of seats in a governmental body in proportion to the number of votes it receives. In a majoritarian system, one party receives all of the seats in question if it receives the majority of votes. Strictly majoritarian systems are rare in modern democracies due to their tendency for suppressing minority views. For example, in the United States presidential elections are dependent upon the allocation of delegates from the electoral college. The number of delegates that each state has is proportional to the state’s population, but all of a state’s delegates are assigned to the presidential candidate who wins the majority of votes in the state. This electoral system is neither strictly majoritarian nor proportional; state delegates are not allocated to candidates in proportion to the votes they receive, but neither is winning the popular vote sufficient to ensure a candidate’s election. This system is intended to provide smaller states and less densely populated regions with influence in national elections.

The question of who may vote is a central issue in elections. The electorate, or the group of people who are eligible to vote, does not generally include the entire population. For example, many countries prohibit those judged mentally incompetent from voting, and all jurisdictions require a minimum age for voting. Historically, jurisdictions have excluded groups such as women, blacks, immigrants, and non-property owners from the electorate. Most national elections require that voters are citizens, and many local elections require proof of local residency to vote.

8.3.4: Likeability of Political Candidates

Candidates run for office by orchestrating expensive campaigns designed to increase their appeal to the electorate.

Learning Objective

Identify the reasons the electorate might be drawn to a particular candidate

Key Points

- The primary trait by which voters evaluate candidates is political ideology, referring to how liberal or conservative the candidate’s views are.

- Political ideology tends to be inferred from political party membership, with the Republican and Democratic parties being seen as conservative and liberal respectively in the U.S.

- Apart from ideology, traits such as likeability and access to funds may determine a campaign’s success or lack thereof.

Key Terms

- campaign

-

An organized effort to influence the decision making process within a specific group when seeking election to political office.

- campaign message

-

The ideas that the candidate wants to share with the voters, often consisting of several talking points about policy issues.

- likeability

-

The property that makes a person likeable, that allows them to be liked.

Candidates running for election to public office need to appeal to the electorate in order to acquire votes. Accordingly, candidates run campaigns aimed at establishing a popular campaign message and convincing voters of the candidate’s likeability.

In many elections, candidates are primarily differentiated by being either liberal or conservative. A candidate’s liberal or conservative ideology is usually expressed by affiliation with a political party — in the U.S. the Republican Party is understood to be conservative and the Democratic Party is understood to be liberal. A candidate’s stated political ideology may be treated as a proxy for their position on a range of policy issues. One’s stance on economic regulation, immigration, and abortion, for example, may be inferred from political party membership. In large part, this association is supported by political parties’ platforms in the U.S. At the same national convention where parties nominate candidates for president, they formalize a platform enumerating party beliefs and objectives. When a candidate for state or national office affiliates with a party, they are therefore associated with that party’s written platform.

Apart from ideology, less explicit factors such as likeability and access to resources impact candidates’ campaigns. Likeability refers to whether or not the electorate generally likes a candidate, as measured by opinion polls . Likeability is thought to play a significant role in electoral politics but is difficult to access in campaigns. Politicians may consciously attempt to augment their likeability by donating to charities, telling jokes during speeches, or posing for photos with voters. However, likeability can be difficult for politicians and political strategists to control.

Voter Opinion Poll

Polling agencies conduct surveys of potential voters during election seasons to measure how the electorate ranks the traits of candidates.

A major critique of large scale electoral politics in the U.S. and other democracies is that a candidate’s wealth has too much influence in the election’s outcome. Modern campaigns usually include television and radio ads, extensive travel, and large organizations of strategists and organizers. Thus, campaigns have become extremely expensive. Major candidates generally need to have immense personal wealth or successful fundraising networks to compete in national campaigns. Therefore, access to monetary resources is an important trait for candidates to possess.

8.4: Presidential Elections

8.4.1: Primaries and Caucuses

Primary elections and caucuses are used to narrow the field of candidates in each major political party before a general election.

Learning Objective

Summarize the primary system and how a primary differs from a caucus

Key Points

- In American politics, the two major political parties provide networks of voters and advocates and financial resources to candidates, therefore, candidates seek their nomination before entering general elections.

- Primaries and caucuses occur at the state level and allow candidates to campaign on a smaller scale to seek nomination before entering the national campaign.

- The structure of primaries and caucuses varies by state, with some contests requiring official affiliation with a party in order to cast a vote in the nominating election.

Key Terms

- general election campaign

-

an organized effort which seeks to influence who is voted into the office of presidency and other federal and state legislative offices

- closed primary

-

an election in which only party members are allowed to vote, and during which they choose their party’s candidates for an upcoming general election

- delegate

-

A person authorized to act as representative for another; in politics, a party representative allocated to nominate a party candidate.

- caucus

-

A meeting, especially a preliminary meeting, of persons belonging to a party, to nominate candidates for public office, or to select delegates to a nominating convention, or to confer regarding measures of party policy; a political primary meeting.

- primary election

-

A preliminary election to select a political candidate of a political party.

Example

- The Iowa caucuses are the first nominating election to occur in the presidential primary season and, therefore, they often have a significant impact on later primaries. In 2008, a win in the Iowa caucuses gave candidate Barack Obama a major boost; a win in 2000 had the same result for George W. Bush.

In America’s two-party political system, political parties rely on primary elections and caucuses to nominate candidates for general elections. Political parties provide resources to the candidates they nominate, including endorsements, social contacts, and financial support. Consequently, attaining a party nomination by winning a primary election or caucus is a necessary step to becoming a major election candidate. Primaries are held on different dates in different states and give national candidates an opportunity to campaign to smaller audiences than during the general election. The candidate who wins each state vote is granted a certain number of delegates,depending on the state’s size, and the candidate with the most party delegates becomes the party’s general election nominee. Not every election is preceded by a primary season, but most major races, such as presidential and congressional races, use primaries to narrow the field of candidates.

Primary Elections

Primaries began to be widely used in the United States during the Progressive Era in the early 1900s. The impetus behind establishing them was to give more power to voters, rather than allowing behind the scenes political maneuverers to choose major candidates. In modern elections, primaries are seen as beneficial to both voters and parties in many ways – voters are able to choose between a range of candidates who fit within a broader liberal or conservative ideology, and parties are able to withhold support of a candidate until they have demonstrated an ability to gain public support.

Primary rules vary by state, as does the importance of their outcomes. Primaries may be classified as closed, semi-closed, semi-open, or open. In a closed primary, only voters who are registered with the party holding the primary are allowed to vote. In other words, registered Republicans can only vote to choose a candidate from the Republican field, and Democrats can only vote in the Democratic primary. In a semi-closed system, voters need not register with a party before the election, therefore independent voters may choose to vote in either the Democratic or Republican primary. In an open primary system, voters can vote in either primary regardless of affiliation. Open primaries are the most controversial form in American politics. Supporters argue that open primaries give more power to the voter and less to the party, since voters are not tied to voting for a party that does not produce a good candidate. Critics, however, argue that open primaries will lead to vote raiding, a practice in which party members vote in the opposing party’s primary in an attempt to nominate a weak candidate.

Caucuses

Whereas primaries follow the same polling practices as general elections, caucuses are structured quite differently. In nominating caucuses, small groups of voters and state party representatives meet to nominate a candidate. Caucuses vary between the states in which they are held, however, generally they include speeches from party representatives, voter debate, and then voting by either a show of hands or a secret ballot . Like primaries, caucuses result in state delegates being allocated to a particular candidate, to nominate that candidate to the general election. The vast majority of states use primaries to nominate a candidate, but caucuses are notably used in Iowa, which is traditionally the first state to vote in the primary/caucus season. Since Iowa is first, it has a large impact on the primary season, as it gives one candidate from each party an advantage as they move into other state votes. Due to its small population and the small-scale, intimate structure of its caucuses, Iowa is notorious for allowing lesser- known candidates to do unexpectedly well.

Washington State Caucus

Caucuses occur in small settings and often include lively debate by party members.

8.4.2: The National Convention

Political parties hold national conventions to nominate candidates for the presidency and to decide on a platform.

Learning Objective

Compare contemporary political conventions with those in middle 19th-century

Key Points

- National party conventions are designed to officially nominate the party’s candidate and develop a statement of purpose and principles called the party platform. Informally, political parties use the conventions to build support for their candidates.

- From the point of view of the parties, the convention cycle begins with the Call to Convention. Usually issued about 18 months in advance, the Call is an invitation from the national party to the state and territory parties to convene to select a presidential nominee.

- Each party sets its own rules for the participation and format of the convention. Broadly speaking, each U.S. state and territory party is apportioned a select number of voting representatives, individually known as delegates and collectively as the delegation.

- The convention is typically held in a major city selected by the national party organization 18–24 months before the election is to be held.

- Each convention produces a statement of principles known as its platform, containing goals and proposals known as planks. Relatively little of a party platform is even proposed as public policy.

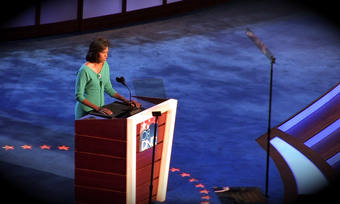

- The evening’s speeches – designed for broadcast to a large national audience—are reserved for major speeches by notable, respected public figures.

Key Terms

- party platform

-

A statement of principles and purpose issued by a political party.

- national convention

-

a political convention held in the United States every four years by political parties fielding candidates in the upcoming presidential election.

- planks

-

Planks refer to the goals and proposals in the platform of a political party.

Example

- The selection of individual delegates and their alternates, too, is governed by the bylaws of each state party, or in some cases by state law. The 2004 Democratic National Convention counted 4,353 delegates and 611 alternates.

Introduction

A national convention is a political convention held in the United States every four years by political parties fielding candidates in the upcoming presidential election. National party conventions are designed to officially nominate the party’s candidate and develop a statement of purpose and principles called the party platform. Informally, political parties use the conventions to build support for their candidates.

Major political parties in the early 1830s were the first to use the political convention. These were often heated affairs, with delegates from each state playing a major role in determining the party’s national nominee . The term “dark horse candidate” was coined at the 1844 Democratic National Convention when little-known Tennessee politician James K. Polk emerged as the candidate after the leading candidates failed to secure the necessary two-thirds majority vote.

Democratic National Convention (1876)

An image from a newspaper article about the 1876 Democratic National Convention in St. Louis, MO.