7.1: Interest Groups

7.1.1: The Constitutional Right to Petition the Government

The Supreme Court has ruled that petitioning the government by way of lobbying is protected by the Constitution as free speech.

Learning Objective

Describe the constitutional warrant for lobbying the government

Key Points

- The ability of individuals, groups, and corporations to lobby the government is protected by the right to petition in the First Amendment.

- The legality of lobbying took “strong and early root” in the new republic.

- Lobbying, properly defined, is subject to control by Congress.

Key Terms

- First Amendment

-

The first of ten amendments to the constitution of the United States, which protects freedom of religion, speech, assembly, and the press.

- direct lobbying

-

Direct lobbying refers to methods used by lobbyists to influence legislative bodies through direct communication with members of the legislative body, or with a government official who formulates legislation.

- Supreme Court

-

The highest court in the United States.

The ability of individuals, groups, and corporations to lobby the government is protected by the right to petition in the First Amendment. It is protected by the Constitution as free speech; one accounting was that there were three Constitutional provisions which protect the freedom of interest groups to “present their causes to government”, and various decisions by the Supreme Court have upheld these freedoms over the course of two centuries . Corporations have been considered in some court decisions to have many of the same rights as citizens, including their right to lobby officials for what they want. As a result, the legality of lobbying took “strong and early root” in the new republic.

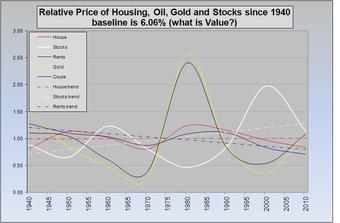

Value or Price

In 1953, after a lawsuit involving a congressional resolution authorizing a committee to investigate “all lobbying activities intended to influence, encourage, promote, or retard legislation,” the Supreme Court narrowly construed “lobbying activities” to mean only “direct” lobbying–which the Court described as “representations made directly to the Congress, its members, or its committees”. It contrasted it with indirect lobbying: efforts to influence Congress indirectly by trying to change public opinion. The Court rejected a broader interpretation of “lobbying” out of First Amendment concerns, and thereby affirmed the earlier decision of the appeals court. The Supreme Court ruling was:

In support of the power of Congress it is argued that lobbying is within the regulatory power of Congress, that influence upon public opinion is indirect lobbying, since public opinion affects legislation; and that therefore attempts to influence public opinion are subject to regulation by the Congress. Lobbying, properly defined, is subject to control by Congress, . . . But the term cannot be expanded by mere definition so as to include forbidden subjects. Neither semantics nor syllogisms can break down the barrier which protects the freedom of people to attempt to influence other people by books and other public writings. . . . It is said that lobbying itself is an evil and a danger. We agree that lobbying by personal contact may be an evil and a potential danger to the best in legislative processes. It is said that indirect lobbying by the pressure of public opinion on the Congress is an evil and a danger. That is not an evil; it is a good, the healthy essence of the democratic process. . . .—Supreme Court decision in Rumely v. United States

Using the Courts

Drawing on the First Amendment, the U.S. Supreme Court has protected lobbying as free speech in numerous rulings since the early republic.

7.1.2: Interest Groups

The term interest group refers to virtually any voluntary association that seeks to publicly promote and create advantages for its cause.

Learning Objective

Discuss the main actors who work for interest groups and seek to influence policy

Key Points

- Interest groups include corporations, charitable organizations, civil rights groups, neighborhood associations, professional, and trade associations.

- Advocacy groups use various forms of advocacy to influence public opinion and/or policy; they have played and continue to play an important part in the development of political and social systems.

- Groups use varied methods to try to achieve their aims including lobbying, media campaigns, publicity stunts, polls, research, and policy briefings. Some groups are supported by powerful business or political interests and exert considerable influence on the political process.

- Some powerful Lobby groups have been accused of manipulating the democratic system for narrow commercial gain. and in some instances have been found guilty of corruption, fraud, bribery, and other serious crimes; lobbying has become increasingly regulated as a result.

Key Terms

- interest groups

-

The term interest group refers to virtually any voluntary association that seeks to publicly promote and create advantages for its cause. It applies to a vast array of diverse organizations. This includes corporations, charitable organizations, civil rights groups, neighborhood associations, and professional and trade associations.

- advocacy groups

-

Advocacy groups use various forms of advocacy to influence public opinion and/or policy; they have played and continue to play an important part in the development of political and social systems.

Example

- There are many significant advocacy groups through history, some of which operate with different dynamics and could better be described as social movements. For example, Greenpeace is a non-governmental environmental organization with offices in over forty countries and with an international coordinating body in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Greenpeace states its goal is to “ensure the ability of the Earth to nurture life in all its diversity” and focuses its campaigning on worldwide issues such as global warming, deforestation, overfishing, commercial whaling, and anti-nuclear issues.

Interest Groups

Introduction

The term interest group refers to virtually any voluntary association that seeks to publicly promote and create advantages for its cause. It applies to a vast array of diverse organizations. This includes corporations, charitable organizations, civil rights groups, neighborhood associations, professional, and trade associations. Advocacy groups use various forms of advocacy to influence public opinion and/or policy; they have played and continue to play an important part in the development of political and social systems.

Groups vary considerably in size, influence, and motive; some have wide ranging long term social purposes, others are focused and are a response to an immediate issue or concern. Motives for action may be based on a shared political, faith, moral, or commercial position. Groups use varied methods to try to achieve their aims including lobbying, media campaigns, publicity stunts, polls, research, and policy briefings. Some groups are supported by powerful business or political interests and exert considerable influence on the political process, while others have few such resources.

Some interest groups have developed into important social, political institutions or social movements. Some powerful Lobby groups have been accused of manipulating the democratic system for narrow commercial gain. In some instances, they have been found guilty of corruption, fraud, bribery, and other serious crimes; lobbying has become increasingly regulated as a result. Some groups, generally ones with less financial resources, may use direct action and civil disobedience, and in some cases are accused of being domestic extremists or a threat to the social order. Research is beginning to explore how advocacy groups use social media to facilitate civic engagement and collective action.

There are many significant advocacy groups throughout history, some of which operate with different dynamics and could better be described as social movements. There are some notable groups operating in different parts of the world. For example, Greenpeace is a non-governmental environmental organization with offices in over forty countries and with an international coordinating body in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Greenpeace states its goal is to “ensure the ability of the Earth to nurture life in all its diversity” and focuses its campaigning on worldwide issues such as global warming, deforestation, overfishing, commercial whaling, and anti-nuclear issues.

Greenpeace

Greenpeace is a non-governmental environmental organization with offices in over forty countries and with an international coordinating body in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Greenpeace states its goal is to “ensure the ability of the Earth to nurture life in all its diversity” and focuses its campaigning on world wide issues such as global warming, deforestation, overfishing, commercial whaling, and anti-nuclear issues. Greenpeace uses direct action, lobbying, and research to achieve its goals.

In some instances, advocacy groups have been convicted of illegal activity. Major examples include: 1) Jack Abramoff Indian lobbying scandal Corrupt and fraudulent lobbying in relation to Native American gambling enterprises; 2) Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement between the Attorneys General of 46 states and the four largest US tobacco companies who agreed to pay $206 billion over the first twenty-five years of the agreement

7.1.3: Organization of Interest Groups

Interest groups can come in varied forms and organize under different methods.

Learning Objective

Discuss the theories behind interest groups and their effects on government

Key Points

- An employers’ organization is an association of employers. The role and position of an employers’ organization differs from country to country, depending on the economic system of a country.

- Occupational organizations promote the professional and economic interests of workers in a particular occupation, industry, or trade, through interaction with the government, and by preparing advertising and other promotional campaigns to the public.

- Interest groups can be technical or non technical. Some are dedicated to unions while others to specific interests.

- Their organization and operations can be based on any of three theories: pluralism, neo-pluralism, and corporatism.

Key Terms

- occupational organizations

-

Occupational organizations promote the professional and economic interests of workers in a particular occupation, industry, or trade, through interaction with the government, and by preparing advertising and other promotional campaigns to the public.

- employers’ organization

-

An employers’ organization is an association of employers.

Introduction

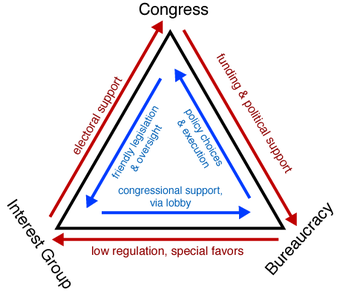

A Special Interest Group (SIG) is a community with particular interest in advancing a specific area of knowledge, learning or technology.Members cooperate to affect or to produce solutions within their particular field, and may communicate, meet, and organize conferences. They may, in some cases, also advocate or lobby on a particular issue or on a range of issues but they are generally distinct from advocacy and pressure groups which are normally set up for the specific political aim; this distinction is not firm however and some organizations can adapt and change their focus over time. Public policy, in general, is a dynamic interplay of decisions between the President, Congress and interest groups.

Organizations may also have Special Interest Groups which are normally focused on a mutual interest or shared characteristic of a subset of members of the organization. An important example for this are trade unions, educational unions, and labor unions .

National Educators Association

The NEA is a prominent and powerful interest group

Much work has been undertaken by academics in trying to categorize how pressure groups operate, particularly in relation to governmental policy creation.

The field is dominated by several differing schools of thought:

- Pluralism: This is based upon the understanding that pressure groups operate in competition with one another and play a key role in the political system. They do this by acting as a counterweight to undue concentrations of power. However, this pluralist theory (formed primarily by American academics) reflects a more open and fragmented political system similar to that in countries like the United States. Under neo-pluralism, a concept of political communities developed that is more similar to the British form of government

- Neo-Pluralism: This is based on the concept of political communities in that pressure groups and other similar bodies are organised around a government department and its network of client groups. The members of this network co-operate during the policy making process.

- Corporatism: Some pressure groups are backed by private businesses that have heavy influence on the legislature.

7.1.4: The Characteristics of Members

Membership interests represent individuals for social, business, labor, or charitable purposes to achieve political goals.

Learning Objective

Explain the benefits and incentives of joining interest groups

Key Points

- An interest group is a group of individuals who share common objectives, and whose aim is to influence policymakers.

- Membership includes a group of people that join an interest group and unite under one cause. They may or may not have an opinion on some of the issues the staff pursues.

- Similarly, staff are the leaders of this group that heads up the membership. With the membership united under one cause, the staff has the ability to pursue other issues that the membership may disagree on, but will remain members united by the primary cause.

- Mancur Lloyd Olson sought to understand the logical basis of interest group membership and participation. In his first book, he theorized that “only a separate and ‘selective’ incentive will stimulate a rational individual in a latent group to act in a group-oriented way.

Key Terms

- interest group

-

Collections of members with shared knowledge, status, or goals. In many cases, these groups advocate for particular political or social issues.

- mancur lloyd olson

-

Mancur Lloyd Olson, a leading American economist, sought to understand the logical basis of interest group membership and participation. In his first book, The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (1965), he theorized that “only a separate and ‘selective’ incentive will stimulate a rational individual in a latent group to act in a group-oriented way”; that is, members of a large group will not act in the group’s common interest unless motivated by personal gains.

Example

- Membership interests are organizations that represent individuals for social, business, labor, or charitable purposes, in order to achieve civil or political goals. This includes the NAACP (represents African-American interests), the Sierra Club (represents environmental interests), the NRA (represents Second Amendment interests), and Common Cause (represents interests in an increase in voter turnout and knowledge).

Introduction

An interest group is a group of individuals who share common objectives, and whose aim is to influence policymakers. Institutional interests are organizations that represent other organizations, whose rules and policies are custom-fit to the needs and wants of the organizations they serve. This includes the American Cotton Manufacturers (which represents the generally congruous southern textile mills) and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce (which represents the multitude of wants of American businesses).

Membership interests are organizations that represent individuals for social, business, labor, or charitable purposes, in order to achieve civil or political goals. This includes the NAACP(represents African-American interests), the Sierra Club (represents environmental interests), the NRA (represents Second Amendment interests, ), and Common Cause (represents interests in an increase in voter turnout and knowledge). Membership includes a group of people that join an interest group and unite under one cause. They may or may not have an opinion on some of the issues the staff pursues. Similarly, staff are the leaders of this group that heads up the membership. With the membership united under one cause, the staff has the ability to pursue other issues that the membership may disagree on, but will remain members united by the primary cause.

NRA Headquarters

The headquarters of the NRA, an interest group, located in Fairfax Virginia, USA. The NRA represents an interest group advocating for the rights to own weapons under the Second Amendment of the United States.

Benefits and Incentives

The general theory is that individuals must be enticed with some type of benefit to join an interest group. Known as the free rider problem, it refers to the difficulty of obtaining members of a particular interest group when the benefits are already reaped without membership. For instance, an interest group dedicated to improving farming standards will fight for the general goal of improving farming for every farmer, even those who are not members of that particular interest group. Thus, there is no real incentive to join an interest group and pay dues if the farmer will receive that benefit anyway. Interest groups must receive dues and contributions from its members in order to accomplish its agenda. While every individual in the world would benefit from a cleaner environment, an Environmental protection interest group does not, in turn, receive monetary help from every individual in the world.

Selective material benefits are benefits that are usually given in monetary benefits. For instance, if an interest group gives a material benefit to their member, they could give them travel discounts, free meals at certain restaurants, or free subscriptions to magazines, newspapers, or journals. Many trade and professional interest groups tend to give these types of benefits to their members. A selective solidary benefit is another type of benefit offered to members or prospective members of an interest group. These incentives involve benefits like “socializing congeniality, the sense of group membership and identification, the status resulting from membership, fun and conviviality, the maintenance of social distinctions, and so on. A solidary incentive is one in which the rewards for participation are socially derived and created out of the act of association.

An expressive incentive is another basic type of incentive or benefit offered to being a member of an interest group. People who join an interest group because of expressive benefits likely joined to express an ideological or moral value that they believe in. Some include free speech, civil rights, economic justice, or political equality. To obtain these types of benefits, members would simply pay dues, donating their time or money to get a feeling of satisfaction from expressing a political value. Also, it would not matter if the interest group achieved their goal; these members would merely be able to say they helped out in the process of trying to obtain these goals, which is the expressive incentive that they got in the first place. The types of interest groups that rely on expressive benefits or incentives would be environmental groups and groups who claim to be lobbying for the public interest.

Collective Action

Mancur Lloyd Olson, a leading American economist, sought to understand the logical basis of interest group membership and participation. The reigning political theories of his day granted groups an almost primordial status. Some appealed to a natural human instinct for herding, others ascribed the formation of groups that are rooted in kinship to the process of modernization. Olson offered a radically different account of the logical basis of organized collective action. In his first book, The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (1965), he theorized that “only a separate and ‘selective’ incentive will stimulate a rational individual in a latent group to act in a group-oriented way”; that is, members of a large group will not act in the group’s common interest unless motivated by personal gains.

7.1.5: Motivations Behind the Formation of Interest Groups

Members comprising interest groups join for solidarity, material, or purposive incentives.

Learning Objective

Identify the benefits and incentives for individuals to join interest groups

Key Points

- The free rider problem refers to the difficulty of obtaining members of a particular interest group when the benefits are already reaped without membership.

- A collective good refers to something of value that cannot be withheld from a nonmember of a group.

- Selective material benefits are benefits that are usually given in monetary benefits. For instance, if an interest group gives a material benefit to their members, they could give them rewards for their efforts.

- A selective solidary benefit refers to the benefits of belonging to a community of shared principles and interests. Members join for the benefits of group distinction and the status resulting from membership.

- An expressive incentive is another basic type of incentive or benefit offered to being a member of an interest group. People who join an interest group because of expressive benefits likely joined to express an ideological or moral value that they believe in.

- A purposive incentive refers to a benefit that comes from serving a cause or principle; people who join because of these are usually passionate about the cause or principle.

Key Terms

- expressive incentive

-

An expressive incentive is another basic type of incentive or benefit offered to being a member of an interest group. People who join an interest group because of expressive benefits likely joined to express an ideological or moral value that they believe in. Some include free speech, civil rights, economic justice, or political equality.

- solidary benefit

-

A selective solidary benefit is another type of benefit offered to members or prospective members of an interest group. These incentives involve benefits like “socializing congeniality, the sense of group membership and identification, the status resulting from membership, fun and conviviality, the maintenance of social distinctions, and so on.

- selective material benefits

-

Selective material benefits are benefits that are usually given in monetary benefits. For instance, if an interest group gives a material benefit to their member, they could give them travel discounts, free meals at certain restaurants, or free subscriptions to magazines, newspapers, or journals.

- free rider

-

In economics, collective bargaining, psychology and political science, “free riders” are those who consume more than their fair share of a resource, or shoulder less than a fair share of the costs of its production. Free riding is usually considered to be an economic “problem” only when it leads to the non-production or under-production of a public good (and thus to Pareto inefficiency), or when it leads to the excessive use of a common property resource. The free rider problem is the question of how to prevent free riding from taking place (or at least limit its negative effects) in these situations.

- purposive incentive

-

A purposive incentive refers to a benefit that comes from serving a cause or principle; people who join because of these are usually passionate about the cause or principle.

- collective goods

-

items and resourcses that benefit everyone, and from which people cannot be excluded

Example

- To illustrate the free rider problem and collective goods, take for instance a tax write-off for a better environment. While every individual in the world would benefit from a cleaner environment, an environmental protection interest group does not, in turn, receive monetary help from every individual in the world.

Why Interest Groups Form

Introduction

The general theory is that individuals must be enticed with some type of benefit to join an interest group. Known as the free rider problem, it refers to the difficulty of obtaining members of a particular interest group when the benefits are already reaped without membership. For instance, an interest group dedicated to improving farming standards will fight for the general goal of improving farming for every farmer, even those who are not members of that particular interest group. Thus, there is no real incentive to join an interest group and pay dues if the farmer will receive that benefit anyway. Interest groups must receive dues and contributions from its members in order to accomplish its agenda. A collective good refers to something of value that cannot be withheld from a nonmember of a group. To illustrate the free rider problem and collective goods, take environmental groups who advocate for a cleaner environment. While every individual in the world would benefit from a cleaner environment, an environmental protection interest group does not, in turn, receive monetary help from every individual in the world.

Types of Benefits and Incentives

Selective material benefits are benefits that are usually given in monetary benefits. For instance, if an interest group gives a material benefit to their member, they could give them travel discounts, free meals at certain restaurants, or free subscriptions to magazines, newspapers, or journals. Many trade and professional interest groups tend to give these types of benefits to their members. A selective solidary benefit is another type of benefit offered to members or prospective members of an interest group. These incentives involve benefits like socializing congeniality, the sense of group membership and identification, the status resulting from membership, fun and conviviality, the maintenance of social distinctions, and so on. A solidary incentive is one in which the rewards for participation are socially derived and created out of the act of association.

An expressive incentive is another basic type of incentive or benefit offered to being a member of an interest group. People who join an interest group because of expressive benefits likely joined to express an ideological or moral value that they believe in. Some include free speech, civil rights, economic justice, or political equality . To obtain these types of benefits, members would simply pay dues, donating their time or money to get a feeling of satisfaction from expressing a political value. Also, it would not matter if the interest group achieved their goal. These members would merely be able to say they helped out in the process of trying to obtain these goals, which is the expressive incentive that they got in the first place. The types of interest groups that rely on expressive benefits or incentives would be environmental groups and groups who claim to be lobbying for the public interest. A purposive incentive refers to a benefit that comes from serving a cause or principle; people who join because of these are usually passionate about the cause or principle .

Protests at the 2008 Republican National Convention

A purposive incentive refers to a benefit that comes from serving a cause or principle; people who join because of these are usually passionate about the cause or principle.

Demonstration against Ahmadinejad in Rio

An expressive incentive is another basic type of incentive or benefit offered to being a member of an interest group. People who join an interest group because of expressive benefits likely joined to express an ideological or moral value that they believe in.

7.1.6: The Function of Interest Groups

An advocacy group is a group or an organization that tries to influence the government but does not hold power in the government.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast the function of interest groups

Key Points

- A single-issue group may form in response to a particular issue area sometimes in response to a single event or threat. In some cases initiatives initially championed by advocacy groups later become institutionalized as important elements of civic life.

- Anti-defamation organizations issue responses or criticisms to real or supposed slights of any sort by an individual or group against a specific segment of the population that the organization exists to represent.

- Watchdog groups exist to provide oversight and rating of actions or media by various outlets, both government and corporate. They may also index personalities, organizations, products and activities in databases to provide coverage and rating of the value of such entities.

- Lobby groups work for a change to the law or the maintenance of a particular law and big businesses fund very considerable lobbying influence on legislators, for example in the U.S. and in the U.K. where lobbying first developed.

- Legal defense funds provide funding for the legal defense for, or legal action against, individuals or groups related to their specific interests or target demographic by filing Amicus Curiae in court.

Key Terms

- legal defense funds

-

Legal defense funds provide funding for the legal defense for, or legal action against, individuals or groups related to their specific interests or target demographic.

- lobby groups

-

The act of attempting to persuade a group of people that influence decisions made by officials in the government, most often legislators or members of regulatory agencies.

- anti-defamation organizations

-

Anti-defamation organizations issue responses or criticisms to real or supposed slights of any sort by an individual or group against a specific segment of the population that the organization exists to represent.

- advocacy group

-

An advocacy group is a group or an organization that tries to influence the government but does not hold power in the government.

- watchdog groups

-

Watchdog groups exist to provide oversight and rating of actions or media by various outlets, both government and corporate.

Example

- Groups representing broad interests of a group may be formed with the purpose of benefiting the group over an expended period of time and in many ways; examples include Consumer organizations, Professional associations, Trade associations and Trade unions.

Introduction

An advocacy group is a group or an organization that tries to influence the government but does not hold power in the government . A single-issue group may form in response to a particular issue area sometimes in response to a single event or threat. In some cases initiatives initially championed by advocacy groups later become institutionalized as important elements of civic life (for example universal education or regulation of doctors). Groups representing broad interests of a group may be formed with the purpose of benefiting the group over an extended period of time and in many ways; examples include Consumer organizations, Professional associations, Trade associations and Trade unions.

Health News Watchdog

Media watchdogs ensure that media coverage is factually accurate and as objective as possible.

Activities

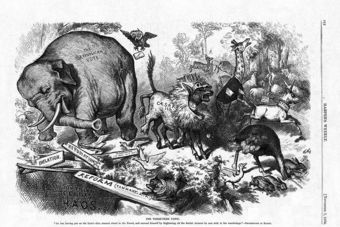

Advocacy groups exist in a wide variety of genres based upon their most pronounced activities . Anti-defamation organizations issue responses or criticisms to real or supposed slights of any sort by an individual or group against a specific segment of the population that the organization exists to represent. Watchdog groups exist to provide oversight and rating of actions or media by various outlets, both government and corporate. They may also index personalities, organizations, products and activities in databases to provide coverage and rating of the value or viability of such entities to target demographics.

Support Public Libraries Advocacy

Advocacy groups seek to influence government policy. In cases such as public libraries, advocacy groups have been critical in lobbying for continued funding across the nation.

Lobby groups work for a change to the law or the maintenance of a particular law and big businesses fund very considerable lobbying influence on legislators, for example in the U.S. and in the U.K. where lobbying first developed. Legal defense funds provide funding for the legal defense for, or legal action against, individuals or groups related to their specific interests or target demographic. This is often accompanied by one of the above types of advocacy groups filing Amicus curiae if the cause at stake serves the interests of both the legal defense fund and the other advocacy groups.

7.1.7: Interest Groups vs. Political Parties

Advocacy groups exert influence on political parties, mostly through campaign finance.

Learning Objective

Explain how competing business interests lobby to influence legislation in Congress

Key Points

- A party or its leading members may be offered money or gifts-in-kind. These donations are the traditional source of funding for all right-of-center cadre parties.

- Advocacy groups exert influence on political parties, mostly through campaign finance.

- Left-wing parties are often funded by organized labor. When the Labor Party was first formed, it was largely funded by trade unions.

Key Term

- advocacy groups

-

Advocacy groups use various forms of advocacy to influence public opinion and/or policy; they have played and continue to play an important part in the development of political and social systems.

Example

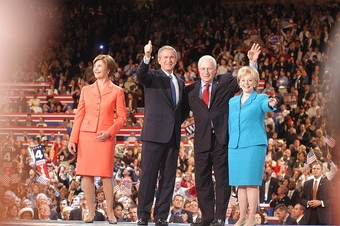

- George W. Bush’s re-election campaign in 2004 was the most expensive in American history. It was financed mainly by large corporations and industrial interests.

Political Parties

Political parties are lobbied vigorously by organizations, businesses, and special interest groups such as trades unions. A party or its leading members may be offered money or gifts-in-kind. These donations are the traditional source of funding for all right-of-center cadre parties. Starting in the late 19th century, these parties were opposed by the new founded left-of-center workers’ parties. They started a new party type, the mass membership party, and a new source of political fundraising, membership dues.

Social Movements

Social movements are a type of group action. They are large informal groupings of individuals or organizations which focus on specific political or social issues. In other words, they carry out, resist or undo a social change. Political science and sociology have developed a variety of theories and empirical research on social movements. For example, some research in political science highlights the relation between popular movements and the formation of new political parties as well as discussing the function of social movements in relation to agenda setting and influence on politics.

Advocacy Groups

In most liberal democracies, advocacy groups tend to use the bureaucracy as the main channel of influence. In liberal democracies, bureaucracy is where the decision-making power lies. Advocacy groups can also exert influence on political parties, and have often done so. The main way groups exert their influence is through campaign finance. In the UK, the conservative party’s campaigns are often funded by large corporations, as many of the conservative party’s campaigns reflect the interests of businesses. In the US, George W. Bush’s re-election campaign in 2004 was the most expensive campaign in American history. It was financed mainly by large corporations and industrial interests . In contrast to the conservative right, left-wing parties are often funded by organized labor. When the Labor Party was first formed, it was largely funded by trade unions. Similarly, political parties are often formed as a result of group pressure. For example, the Labour Party in the UK was formed out of the new trade-union movement, which lobbied for the rights of workers.

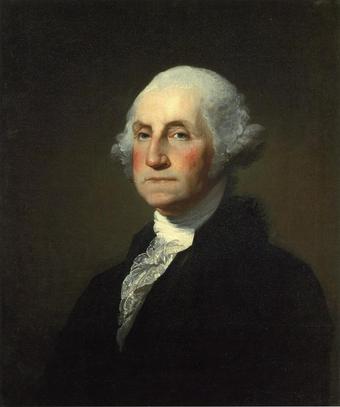

George W. Bush

George W. Bush’s re-election campaign in 2004 was largely funded by special interest groups such as financial banks and large industrial corporations.

More often than not, lobbying coalitions enter into conflict with each other. For example, in the issue of free trade, some corporate lobbyists seek to eliminate or dismantle tariffs, promoting free trade and the free movement of goods and services. By contrast, lobbyists representing farmers and rural interests seek to maintain or reinforce existing tariffs. It is in their best interest to preserve the status quo. If tariffs are reduced or eliminated, then American farmers are forced to compete with farmers from other trading countries. As these coalitions enter into conflict, congressmen must choose how to vote in the face of different pressures from different constituencies.

7.2: Interest Group Strategies

7.2.1: Direct Lobbying

Direct lobbying is used to influence legislative bodies directly via communication with members of the legislative body.

Learning Objective

Describe direct lobbying

Key Points

- During the direct lobbying process, the lobbyist introduces to the legislator information that may supply favors, may otherwise be missed or makes political threats.

- Direct lobbying is different from grassroots lobbying, a process that uses direct communication with the general public.

- Direct lobbying is often used alongside grassroots lobbying.

Key Terms

- grassroots lobbying

-

A process that uses direct communication with the general public, which, in turn, contacts and influences the government.

- legislative bodies

-

Legislative bodies are a kind of deliberative assembly with the power to pass, amend and repeal laws.

- direct lobbying

-

Direct lobbying refers to methods used by lobbyists to influence legislative bodies through direct communication with members of the legislative body, or with a government official who formulates legislation.

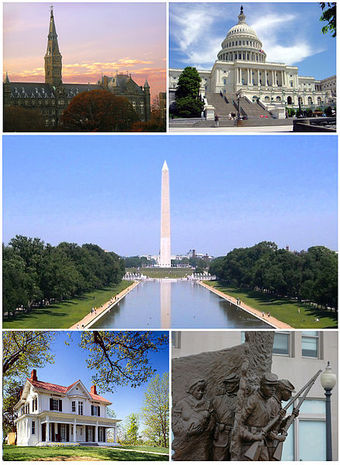

Direct lobbying refers to methods used by lobbyists to influence legislative bodies through direct communication with members of the legislative body, or with a government official who participates in formulating legislation .

Direct Lobbying

Both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives are subject to direct lobbying tactics by lobbyists.

During the direct lobbying process, the lobbyist introduces to the legislator information that may supply favors, may otherwise be missed or makes political threats. A common use of direct lobbying is to persuade the general public about a ballot proposal. In this case, the public is considered to be the legislator. This aspect of direct lobbying attempts to alter the legislature before it is placed on the ballot. Communications regarding a ballot measure are also considered direct lobbying. Direct lobbying is different from grassroots lobbying, a process that uses direct communication with the general public, which, in turn, contacts and influences the government.

Washington, D.C. is the home to many firms that employ these strategies. Lobbyists often attempt to facilitate market entry through the adoption of new rules, or the revision of old ones. They also remove regulatory obstacles for a company looking to grow, while also stopping others from attaining regulatory changes that would harm a company’s cause.

Meta-analysis reveals that direct lobbying is often used alongside grassroots lobbying. There is evidence that groups are much more likely to directly lobby previous allies rather than opponents. Allies are also directly lobbied if a counter lobby is brought to light. When groups have strong ties to a legislator’s district, they will use a combination of grassroots and direct lobbying, even if the legislator’s original position does not support theirs. When strong district ties are not present, groups will rely on direct lobbying with committee allies.

7.2.2: Direct Techniques

Lobbyists employ direct lobbying in the United States to influence United States legislative bodies through direct interaction with legislators.

Learning Objective

Identify the direct techniques used by interest groups to influence policy and what groups would use them

Key Points

- Revolving door is a term used to describe the cycling of former federal employees into jobs as lobbyists while former lobbyists are pulled into government positions.

- There have been several efforts to regulate the lobbying sector including the Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995 and the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act.

- Direct lobbying is different from grassroots lobbying, a process that uses direct communication with the general public, who in turn, contacts and influences the government.

Key Terms

- Lobbying Disclosure Act

-

The Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995 signed into law by President Bill Clinton was revised in 2006 to require the registration of all lobbying entities to occur shortly after the individual lobbyist makes a first plan to lobby any highly ranked federal official.

- Honest Leadership and Open Government Act

-

The Honest Leadership and Open Government Act, signed September 15, 2007 by President Bush, requires a quarterly report on lobby spending, places restrictions on gifts to Congress members, provides for mandatory disclosure of earmarks in expenditure bills, and places restrictions on the revolving door in direct lobbying.

- direct lobbying

-

Direct lobbying in the United States consists of methods used by lobbyists to influence U.S. legislative bodies through direct interaction with those who have influence on the legislature.

Direct lobbying in the United States consists of methods used by lobbyists to influence the United States legislative bodies . Interest groups from many sectors spend billions of dollars on lobbying. There are three lobbying laws in the U.S. that require a lobbying entity to be registered, allow nonprofit organizations to lobby without losing their nonprofit status, require lobbying organizations to present quarterly reports, places restrictions on gifts to U.S. Congress members, and makes it mandatory for earmarks to be disclosed in expenditure bills. Revolving door, when a former federal employee becomes a lobbyist and vice-versa, occurs in the direct lobbying sector.

Washington D.C., Lobbyist Central

As Washington D.C. is the seat of the United States Federal Government, it attracts a high concentration of lobbyists.

Theory

Lobbying is a common practice at all levels of legislature. Direct lobbying is done either through direct communication with members or employees of the legislative body, or with a government official who participates in formulating legislation. During the direct lobbying process, the lobbyist introduces statistics that will inform the legislator of any recent information that might otherwise be missed, and may make political threats or promises, and/or grant favors. Communications regarding a ballot measure are also considered direct lobbying. Direct lobbying is different from grassroots lobbying, a process that uses direct communication with the general public, who in turn contact and influence the government.

The most common goals of lobbyists are:

- to facilitate market entry through the adoption of new rules, or the repeal or revision of old ones.

- to remove regulatory obstacles that prevent the growth of a company.

- to stop others from attaining regulatory changes that would harm the business of one’s company’s or one’s cause.

Direct lobbying is often used alongside grassroots lobbying. When groups have strong ties to a legislator’s district, those groups will use a combination of grassroots and direct lobbying, even if the legislator’s original position does not support theirs, which may help groups expand their coalitions. When strong district ties are not present, groups tend to rely on direct lobbying with committee allies.

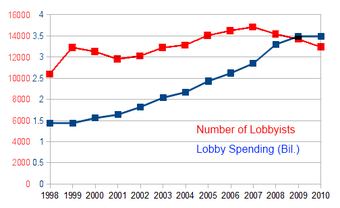

Spending

In 2010, the total amount spent on lobbying in the U.S. was $3.5 billion . The top sectors for lobbying as of 2010 are financial, insurance, and real estate, with $4,405,909,610 spent on lobbying. Health is the second largest sector by spending, with $4,369,979,173 recorded in 2010.

Spending on Lobbying

This graph compares the number of lobbyists with the amount of lobby spending.

The oil and gas sector companies are among the biggest spenders on lobbying. During the 2008 elections, oil companies spent a total of $132.2 million into lobbying for law reform. The three biggest spenders from the oil and gas sector are Koch Industries (1,931,562), Exxon ( ), and the Mobil Corporation (1,192,361).

Lobbying Laws

Lobbying Disclosure Act

The Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995 was signed into law by President Bill Clinton . Under a January 1, 2006 revision, the act requires the registration of all lobbying entities with the Secretary of the Senate and the Clerk of the House of Representatives. The registration must occur within 45 days after the individual lobbyist makes a first plan to lobby. Penalizations include fines of over $50,000 and being reported to the United States Attorney.

Public Charity Lobbying Law

The Public Charity Lobbying Law gives nonprofit organizations the opportunity to spend about 5% of their revenue on lobbying without losing their nonprofit status with the Internal Revenue Service. Organizations must elect to use the Public Charity Law, and so increase the allowable spending on lobbying to increase to 20% for the first $500,000 of their annual expenditures. Another aspect to the law is the spending restrictions between direct lobbying and grassroots lobbying—no more than 20% can be spent on grassroots lobbying at any given time, while 100% of the lobbying expenditures can be on direct lobbying.

Honest Leadership and Open Government Act

The Honest Leadership and Open Government Act was signed on September 15, 2007 by President Bush, amending the Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995. The bill includes provisions that require a quarterly report on lobby spending by organizations, places restrictions on gifts to Congress members, provides for mandatory disclosure of earmarks in expenditure bills, and places restrictions on the revolving door in direct lobbying.

Revolving Door

Revolving door is a term used to describe the cycling of former federal employees into jobs as lobbyists, while former lobbyists are pulled into government positions. Government officials with term limits form valuable connections that could help influence future law-making even when they are out of office. The other form of the revolving door is pushing lobbyists into government positions, developing connections, and returning into the lobbying world to use said connections. A total of 326 lobbyists are part of the Barack Obama Administration . In the past, 527 lobbyists were part of the Bush Administration, compared to 358 during the Clinton Administration.

7.2.3: Indirect Techniques

Grassroots lobbying asks the public to contact legislators concerning the issue at hand, as opposed to going to the legislators directly.

Learning Objective

Identify the indirect techniques used by interest groups to influence legislation

Key Points

- A grassroots lobby puts pressure on the legislature to address the concerns of a particular group by mobilizing that group, usually through raising public awareness and running advocacy campaigns.

- A group or individual classified as a lobbyist must submit regular disclosure reports; however, reporting requirements vary from state to state.

- The unique characteristic of grassroots lobbying, in contrast to other forms of lobbying, is that it involves stimulating the politics of specific communities.

Key Term

- indirect lobbying

-

Grassroots lobbying, or indirect lobbying, is a form of lobbying that focuses on raising awareness in the general population of a particular cause at the local level, with the intention of influencing the legislative process.

Grassroots lobbying

Grassroots lobbying, or indirect lobbying, is a form of lobbying that focuses on raising awareness for a particular cause at the local level, with the intention of influencing the legislative process. Grassroots lobbying is an approach that separates itself from direct lobbying through the act of asking the general public to contact legislators and government officials concerning the issue at hand, as opposed to conveying the message to the legislators directly.

The unique characteristic of grassroots lobbying, in contrast to other forms of lobbying, is that it involves stimulating the politics of specific communities. Interest groups, however, do not recruit candidates to run for office. Rather, they choose to influence candidates and public officials using indirect tactics of advocacy.

Tactics

The main two tactics used in indirect advocacy are contacting the press (by either a press conference or press release), and mobilizing the mass membership to create a movement.

Media Lobbying

Grassroots lobbying oftentimes implement the use of media, ranging from television to print, in order to expand their outreach. Other forms of free media that make a large impact are things like boycotting, protesting, and demonstrations.

Social Media

The trend of the past decade has been the use of social media outlets to reach people across the globe. Using social media is, by nature, a grassroots strategy.

Mass movements

Mobilizing a specific group identified by the lobby puts pressure on the legislature to address the concerns of this group. These tactics are used after the lobbying group gains the public’s trust and support through public speaking, passing out flyers, and even campaigning through mass media.

Trends

Trends from the past decade in grassroots lobbying include an increase in the aggressive recruitment of volunteers, as well as starting campaigns early on, before the legislature has made a decision. Also, lobbying groups have been able to create interactive websites and utilize social media (including Facebook and Twitter) to email, recruit volunteers, assign them tasks, and keep the goal of the lobbying group on track.

Regulations

Lobbying is protected by the First Amendment rights of speech, association, and petition . Federal law does not mandate grassroots lobbying disclosure, yet 36 states regulate grassroots lobbying. There are 22 states that define lobbying as direct or indirect communication to public officials, and 14 additional states that define it as any attempt to influence public officials. A group or individual classified as a lobbyist must submit regular disclosure reports; however, reporting requirements vary from state to state. Some states’ disclosure requirements are minimal and require only registration, while other states’ requirements are extensive, including the filing of monthly to quarterly expense reports, which include all legislative activity relevant to the individual or groups activities, amounts of contributions and donations, and the names and addresses of contributors and specified expenses. Penalties range from civil fines to criminal penalties if regulations are not complied with.

Bill of Rights

The First Amendment rights of free speech, freedom of association, and freedom of petition protect lobbying, including grassroots lobbying.

7.2.4: Cultivating Access

Access is important and often means a one-on-one meeting with a legislator.

Learning Objective

Describe how lobbying and campaign finance intersect

Key Points

- Getting access can sometimes be difficult, but there are various avenues: email, personal letters, phone calls, face-to-face meetings, meals, get-togethers, and even chasing after congresspersons in the Capitol building.

- When getting access is difficult, there are ways to wear down the walls surrounding a legislator.

- One of the ways in which lobbyists gain access is through assisting congresspersons with campaign finance by arranging fundraisers, assembling PACs, and seeking donations from other clients.

Key Terms

- PACs

-

A political action committee (PAC) is any organization in the United States that campaigns for or against political candidates, ballot initiatives or legislation.

- access

-

A way or means of approaching or entering; an entrance; a passage.

Access is important and often means a one-on-one meeting with a legislator . Getting access can sometimes be difficult, but there are various means one can try: email, personal letters, phone calls, face-to-face meetings, meals, get-togethers, and even chasing after congresspersons in the Capitol building. One lobbyist described his style of getting access as “not to have big formal meetings, but to catch members on the fly as they’re walking between the House and the office buildings. “

Cultivating Access

Connections count: Congressperson Tom Perriello with lobbyist Heather Podesta at an inauguration party for Barack Obama.

When getting access is difficult, there are ways to wear down the walls surrounding a legislator. Lobbyist Jack Abramoff explains:

Access is vital in lobbying. If you can’t get in your door, you can’t make your case. Here we had a hostile senator, whose staff was hostile, and we had to get in. So that’s the lobbyist safe-cracker method: throw fundraisers, raise money, and become a big donor. —Abramoff in 2011

One of the ways in which lobbyists gain access is through assisting congresspersons with campaign finance by arranging fundraisers, assembling PACs, and seeking donations from other clients. Many lobbyists become campaign treasurers and fundraisers for congresspersons. This helps incumbent members cope with the substantial amounts of time required to raise money for reelection bids; one estimate was that Congresspersons had to spend a third of their working hours on fundraising activity. PACs are fairly easy to set up; all they require is a lawyer and about $300.

An even steeper possible reward which can be used in exchange for favors is the lure of a high-paying job as a lobbyist. According to Abramoff, one of the best ways to “get what he wanted” was to offer a high-ranking congressional aide a high-paying job after they decided to leave public office. When such a promise of future employment was accepted, according to Abramoff, “we owned them”. This helped the lobbying firm exert influence on that particular congressperson by going through the staff member or aide. At the same time, it is hard for outside observers to argue that a particular decision, such as hiring a former staffer into a lobbying position, was purely as a reward for some past political decision, since staffers often have valuable connections and policy experience needed by lobbying firms. Research economist Mirko Draca suggested that hiring a staffer was an ideal way for a lobbying firm to try to sway their old bosses—a congressperson—in the future.

7.2.5: Mobilizing Public Opinion

Increasingly, lobbyists seek to influence politics by putting together large coalitions and using outside lobbying to sway public opinion.

Learning Objective

Differentiate between direct and indirect lobbying efforts

Key Points

- Efforts to influence Congress indirectly, by trying to change public opinion, are often referred to as indirect lobbying.

- Larger, more diverse, and more wealthy coalitions tend to be the most effective at outside lobbying (the “strength in numbers” principle applies).

- Increasingly, in order to influence elections, lobbyists have put together large coalitions and mobilized outside lobbying efforts aimed at swaying and controlling public opinion.

Key Terms

- indirect lobbying

-

Efforts to influence Congress indirectly by trying to change public opinion. These efforts depend on the fact that politicians must frequently appeal to the public during regular election cycles.

- direct lobbying

-

Direct lobbying refers to methods used by lobbyists to influence legislative bodies through direct communication with members of the legislative body, or with a government official who formulates legislation.

- public opinion

-

The opinion of the public, the popular view.

In 1953, following a lawsuit that included a congressional resolution that authorized a governmental committee to investigate “all lobbying activities intended to influence, encourage, promote, or retard legislation,” the Supreme Court narrowly construed “lobbying activities” to mean only “direct” lobbying. The Court defined this “direct” method of lobbying as “representations made directly to the Congress, its members, or its committees”. It contrasted this with indirect lobbying, which it defined as efforts to influence Congress indirectly by trying to change public opinion.

Mobilizing Public Opinion

Large health notices on tobacco products is one way in which the anti-smoking lobby and the government have tried to mobilize public opinion against smoking.

Increasingly, lobbyists seek to influence politics by putting together coalitions and by utilizing outside lobbying to mobilize public opinion on issues. Larger, more diverse, and more wealthy coalitions tend to be more effective at outside lobbying (the “strength in numbers” principle often applies). These groups have been defined as “sustainable coalitions of similarly situated individual organizations in pursuit of like-minded goals. ” According to one study, it is often difficult for a lobbyist to influence a staff member in Congress directly, because staffers tend to be well-informed, and because they frequently hear views from competing interests. As an indirect tactic, lobbyists often try to manipulate public opinion which, in turn, can sometimes exert pressure on congresspersons, who must frequently appeal to that public during electoral campaigns. One method for exerting this indirect pressure is the use of mass media. Interest groups often cultivate contacts with reporters and editors and encourage these individuals to write editorials and cover stories that will influence public opinion regarding a particular issue. Because of the important connection between public opinion and voting, this may have the secondary effect of influencing Congress. According to analyst Ken Kollman, it is easier to sway public opinion than a congressional staff member, because it is possible to bombard the public with “half-truths, distortion, scare tactics, and misinformation. ” Kollman suggests there should be two goals in these types of efforts. First, communicate to policy makers that there is public support behind a particular issue, and secondly, increase public support for that issue among constituents. Kollman asserted that this type of outside lobbying is a “powerful tool” for interest group leaders. In a sense, using these criteria, one could consider James Madison as having engaged in outside lobbying. After the Constitution was proposed, Madison wrote many of the 85 newspaper editorials that argued for people to support the Constitution. These writings later came to be known as the Federalist Papers. As a result of Madison’s “lobbying” effort, the Constitution was ratified, although there were narrow margins of victory in four of the states.

Lobbying today generally requires mounting a coordinated campaign, which can include targeted blitzes of telephone calls, letters, and emails to congressional lawmakers. It can also involve more public demonstrations, such as marches down the Washington Mall, or topical bus caravans. These are often put together by lobbyists who coordinate a variety of interest group leaders to unite behind a hopefully simple, easy-to-grasp, and persuasive message.

7.2.6: Using Electoral Politics

A number of interest groups have sought out electoral politics as a means of gaining access and influence on broader American policies.

Learning Objective

Give an example of an interest group making determined use of electoral politics

Key Points

- One example of an interest group using electoral politics is the National Caucus of Labor Committees.

- in 1972, the NCLC launched the U.S. Labor Party (USLP), a registered political party, as its electoral arm. They later nominated LaRouche for President of the United States.

- The National Caucus of Labor Committees (NCLC) is a political cadre organization in the United States founded and controlled by political activist Lyndon LaRouche, who has sometimes described it as a “philosophical association”.

Key Terms

- electoral politics

-

An election is a formal decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual to hold public office.

- interest group

-

Collections of members with shared knowledge, status, or goals. In many cases, these groups advocate for particular political or social issues.

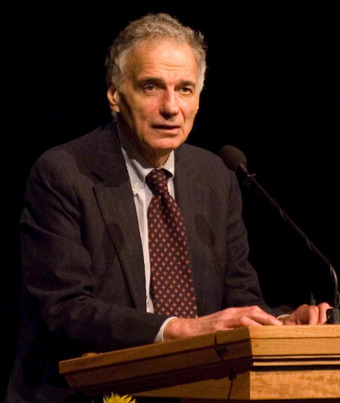

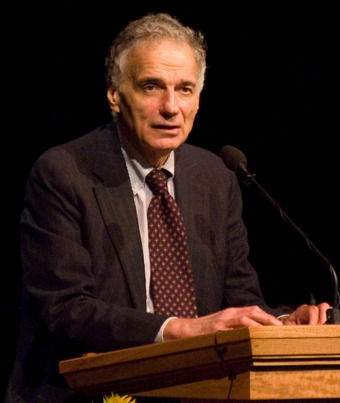

All electoral politics are interest politics in some sense. Over the course of American history, a number of interest groups have sought out electoral politics as a means of gaining access and influence on broader American policies. One example of an interest group using electoral politics is the National Caucus of Labor Committees (NCLC).

The NCLC is a political cadre organization in the United States, founded and controlled by political activist Lyndon LaRouche, who has sometimes described it as a “philosophical association. “

Lyndon LaRouche

LaRouche was the leader of the National Caucus of Labor Committees, an interest group that later developed a distinct political party that nominated LaRouche for president of the U.S.

LaRouche is the NCLC’s founder and the inspiration for its political views. (For more information on these views see the article “Political Views of Lyndon LaRouche,” as well as the main article titled “Lyndon LaRouche. ” An overview of LaRouche’s organizations is in “LaRouche movement. “) The highest group within the NCLC is the “National Executive Committee” (NEC), described as the “inner leadership circle” or “an elite circle of insiders” that “oversees policy. ” The next most senior group is the “National Committee” (NC), which is reportedly “one step beneath the NEC. “

In 1972, the NCLC launched the U.S. Labor Party (USLP), a registered political party, as its electoral arm. In 1976, they nominated LaRouche for President of the United States on the Labor Party ticket, along with numerous candidates for lower office. In 1979, LaRouche changed his political strategy to allow him to run in the Democratic primaries, rather than as a third party candidate. This resulted in the USLP being replaced by the National Democratic Policy Committee (NDPC) a political action committee unassociated with the Democratic National Committee.

7.3: Types of Interest Groups

7.3.1: Business and Economic Interest Groups

Economic interest groups advocate for the economic benefit of their members, and business interests groups are a prominent type of economic interest group.

Learning Objective

Identify the organization and purpose of business and economic interest groups

Key Points

- Economic interest groups are one of the five broad categories of interest groups in the US.

- These groups advocate for the economic interest and benefits of their members.

- Economic interest groups are varied and for and given issue there will be large number of competing interest groups. These category includes groups representing representing business, labor, professional and agricultural interests.

- Business interest groups generally promote corporate or employer interests.

Key Terms

- business group

-

a collection of parent and subsidiary companies that function as a single economic entity through a common source of control

- partisan

-

An adherent to a party or faction.

Business and Economic Interest Groups

Interest groups represent people or organizations with common concerns and interests. These groups work to gain or retain benefits for their members, through advocacy, public campaigns and even by lobbying governments to make changes in public policy. There are a wide variety of interest groups representing a variety of constituencies.

Economic Interest Groups

Economic interest groups are one of the five broad categories of interest groups in the US. These groups advocate for the economic interest and benefits of their members. Economic interest groups are varied, and for any given issue there will be a large number of competing interest groups. Categories of economic interest groups include those representing business, labor, professional and agricultural interests.

Business Interest Groups

Business interest groups generally promote corporate or employer interests. Larger corporations often maintain their own lobbyists to work on behalf of their specific interests. Companies and organizations will also come together in larger groups to work together on general business interests.

Umbrella organizations such as the US Chambers of Commerce (USCC) work around general business interests. While the name might suggest that this is a government agency, the USCC represents various business and trade organizations, and was formed as a counterbalance to the growing power of the labor movement in 1912. The USCC uses a wide variety of strategies and tactics in its work including lobbying or representation, and monitoring various laws and programs. USCC’s work is at times more partisan; for example, it might endorse a specific candidates.

US Chamber of Commerce

This banner celebrating both jobs and free enterprise hung outside of the US Chamber of Commerce to commemorate the groups hundredth year.

Another example of an umbrella business interest group is the US Women’s Chamber of Congress (USWCC). The USWCC’s work could be described as agenda setting, as their work representing women in business attempts to bring attention to an issue that had been neglected. Like other business interest groups, USWCC will work though legal and lobbying to gain benefits for its constituency.

Because of how numerous and well funded business interest groups tend to be, there is always a concern that they are interfering with, rather than enhancing, the democratic process.

7.3.2: Labor Interest Groups

Labor interest groups advocate for the economic interests of workers and trade organizations.

Learning Objective

Explain the decline of labor interest groups and new kinds of organization

Key Points

- Labor interest groups are a type of economic interest group. Economic interest groups advocate for the economic benefit of their members and constituents.

- Labor interest groups advocate for the economic interests of workers and trade organizations.

- In addition to representing their members unions also often organized opportunities for direct citizen participation, along with public education and lobbying.

- Membership in private unions has steadily declines. In 2011 on 7% of workers were union members. Public workers are still unionized at much higher rates.

- New kinds of labor interest groups are developing to represent workers outside of the mainstream workforce, such as low-wage or freelance workers.

Key Terms

- Industrial Unionism

-

Industrial unionism is a labor union organizing method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union—regardless of skill or trade—thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in bargaining and in strike situations.

- craft unionism

-

Craft unionism refers to organizing a union in a manner that seeks to unify workers in a particular industry along the lines of the particular craft or trade that they work in by class or skill level.

Labor Interest Groups

Labor interest groups are a type of economic interest group. Economic interest groups advocate for the economic benefit of their members and constituents. There are a wide variety of types of economic interest groups, including labor groups which advocate on behalf of individual workers and trade organizations. In addition to representing their members, unions also often organize opportunities for direct citizen participation , along with public education and lobbying.

May Day Marches

May 1st is traditionally a day for protests and celebration for labor interest groups. In the US there is now also a focus on immigration and labor rights.

History of Labor Interest Groups

Some of the earliest unions in the US were formed by women in the textile industry in cities such as Lowell, Massachusetts. The National Labor Union (NLU) was the first American federation of unions formed in 1866. In these early days, unions lobbied against dangerous work conditions and for regulations around the work conditions of women and children. They also pushed for an eight hour work day and the right to strike.

The strength of labor interest groups continued in the 19th century. One example was the American Federation of Labor, a large umbrella group made up primarily of locals involved in craft unionism. While labor was more disorganized during the 1920s, the period during and right after WWII saw a continued growth of unions including the formation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). The CIO was built around an industrial unionism model. These two major unions merged in 1955 to form the AFL-CIO.

Unions have had an uneven history with women and people of color. Some early unions, for example, specifically banned members who were Chinese or of Chinese decent. The Pullman’s union and the United Farm Workers unions are examples of unions that came together to advocate for the economic interests of African-American and latino workers.

Decline of Private Labor Interest Groups

With the reduction of manufacturing jobs in the US, the number of people represented by unions has fallen. Also, legislation such as the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act made it harder to organize by allowing individual states to ban “closed-shops. ” These are workplaces in which all new employees are required to join a union. Twenty-three states have such laws in place; these are the so-called “right-to-work” states.

While private union membership has declined, public unions are still quite strong. While only 7% of workers in the private sectors belong to unions, 31% of federal workers, 35% of state workers, and 46% of local government employees belong to unions.

New Kinds of Organizing

Even as traditional labor interest groups are seeing their numbers fall, there are new groups developing around new constituencies of workers who are outside of the mainstream workforce. Some examples include the National Domestic Workers Alliance, Domestic Workers United and the Restaurant Opportunities Center (ROC), which represent low-wage workers. These groups focus on member education as well as advocacy and public education, ensuring their members are aware of the rights that they are already entitled to as well as organizing around new economic benefits.

Another example is the Freelancers Union which provides health care for members who are independent workers. Many of these workers are high-skilled or creative workers who are not eligible for workplace related benefits. This union also works as an agenda building organization, bringing attention to the challenges of freelance workers including the high tax burden for independent workers.

7.3.3: Professional Interest Groups

Professional interest groups represent the economic interests for members of various professions including doctors, engineers, and lawyers.

Learning Objective

Classify professional interest groups that influence policy

Key Points

- Professional interest groups are another type of economic interest group. Economic interest groups advocate for the economic benefit of their members and constituents.

- While labor groups focused on trades and industrial labor, professional interest groups represent members of various professions including doctors and engineers.

- These groups also often set rule for their members, including rules about certification and conduct including professional codes of ethics.

- Professional organizations also provide direct economic benefits to their members. These benefits include personal or professional insurance as well as professional development opportunities.

Key Term

- professions

-

A job, especially one requiring a high level of skill or training.

Professional Interest Groups

Professional interest groups are another type of economic interest group. Economic interest groups advocate for the economic benefit of their members and constituents. There are many types of economic interest groups, including professional interest groups which organize and represent professional workers. While trade unions represent skilled and industrial labor, professional organizations represent skilled workers such as doctors, engineers, and lawyers.

These groups advocate for the economic interests of their members. They groups often set the rules for membership in their organizations. This includes rules about certification and conduct including professional codes of ethics. Professional organizations also provide direct economic benefits to their members. These benefits include access to personal or professional insurance as well as professional development opportunities.

One critique of professional organizations is that they serve to increase the income of their membership without any added value or service.

An example of a professional interest group is the American Medical Association (AMA), which represents doctors and medical students throughout the United States. The AMA conducts significant amounts of member and public education work, including publishing the Journal of the America Medical Association . It also carries out a substantial amount of charity work. Its broad mission is to promote the art and science of medicine for the betterment of the public health. However, it is also committed to advancing the interest of physicals, including economic interests. The AMA often lobbies on behalf of its members. For example, the AMA lobbied in campaigns against Medicare during the 1950’s and 1960’s. While the AMA now supports Medicare it did opposed attempts to create a national health care system. Another campaign that is directly related to economic interests is one to limit the damages awarded in medical malpractice suits.

Journal of the America Medical Association

The first edition of the Journal of the American Medical Association. Today it is the most widely read medical journal in the world.

7.3.4: Agricultural Interest Groups

Agricultural interest groups are a type of economic interest group that represent farmers.

Learning Objective

Analyze the organization and purpose of agricultural interest groups

Key Points

- Agricultural interest groups are a type of economic interest group.

- Agricultural interest groups represent the economic interests of farmers, including issues such as crop prices, land use zoning, government subsidies, and international trade agreements.

- There is a long history of agricultural interest groups in the United States. An example is the American Farm Bureau Federation which started in 1911.

- Today, agricultural interest groups are often divided among themselves. There are various types of farms and farmers in the U.S. with conflicting interests.

Key Term

- yeoman farmer

-

Yeoman refers chiefly to a free man owning his own farm. Work requiring a great deal of effort or labor, such as would be done by a yeoman farmer, came to be described as yeoman’s work. Thus, yeoman became associated with hard toil.

Agricultural Interest Groups

Economic interest groups are varied. For any given issue, there will be large number of competing interest groups. Categories of economic interest groups include those representing business, labor, professional, and agricultural interests.

Agricultural interest groups represent the economic interests of farmers. These interests include business and agricultural extension concerns, as well as matters of local, national, and even international policy. These include crop prices, land use zoning, government subsidies, and international trade agreements.

There is a long history of agricultural interest groups in the United States. An example is the American Farm Bureau Federation which was founded in 1911. As a result of the majority of the country’s rural history, agricultural concerns have long been of great importance. Specifically, the vision of the yeoman farmer was one of the important American archetypes moving into the progressive era.

Today, agricultural interest groups are often divided among themselves. There are various types of farms and farmers in the U.S. that often have conflicting interests. For example, a policy that is beneficial to large scale agribusiness might be highly damaging for small, family farms.

Agricultural interest groups range from large agribusiness, to groups such as the Farm Bureau representing mid-sized and commodity crop farmers, to the Farmers Market Coalition which advocates for policies that would benefit local farm production.