5.1: Slavery and Civil Rights

5.1.1: Slavery and the Abolitionist Movement

Slavery continued until 1865, when abolitionists argued against its conditions as violating Christian principals and rights to equality.

Learning Objective

Describe the history of slavery in the United States and early efforts at abolition

Key Points

- By 1860, four million people lived in slavery in the US. Most were people who had been brought from Africa and their descendants.

- Most people living as slaves worked in agriculture, including in the cotton industry, which was a key industry in the southern states. Enslaved people had few rights and were often subjected to harsh and violent living conditions.

- Abolitionists argued against slavery because of its harsh conditions, and through claims that slavery violated Christian principals and the natural rights of all people for equality.

- Most Northern states moved to end slavery by 1804.

- Freed slaves often continued to face racial segregation and discrimination.

- The conflict over slavery became a key catalyst for the Civil War.

Key Terms

- manumission

-

release from slavery, freedom, the act of manumitting

- Underground Railway

-

a network of secret routes and safe houses used by 19th-century black slaves in the United States to escape to free states and Canada with the aid of abolitionists and allies who were sympathetic to their cause

- chattel slavery

-

people are treated as the personal property, chattels, of an owner and are bought and sold as commodities

Slavery in the US

While the US was founded on principles of representation, due process and universal rights, slavery remained one of the most persistent and visible exceptions to these ideals.

Slavery, including chattel slavery, was a legal institution in the US from the colonial period until the Emancipation Proclamation (1863) and Thirteenth Amendment of the Constitution (1865). Most slaves in the US were people brought from Africa and their descendants, and this racial dimension of US slavery continues to impact US civil rights debates. By 1860, four million people lived as slaves in the US, and most worked in the agriculture sector. The rise in the southern cotton industry after 1800 also led to a steady increase in slavery, which then became a major catalyst for the Civil War.

Conditions of Slavery

The conditions of slavery were harsh, starting with the “middle passage” where Africans were stuffed into the hulls of ships like cargo. Some fifteen percent of enslaved people are estimated to have died during travel from Africa. In the US the conditions of slavery acted to dehumanize enslaved people denying them even basic rights. The use of native languages was banned, and it was illegal to learn or teach reading and writing. Marriages were banned, and children were often taken away from parents to be sold. It was also common for slave owners to sexually assault enslaved women. Finally, working conditions were long and hard, especially for field workers, and violence was an ever present part of life.

Abolition

Throughout this period many people worked to end slavery. Early abolitionist legislation included Congress prohibiting slavery in the Northwest Territory (1787), and a ban on the import or export of slaves (1808) in the US and Britain. Resistance to slavery also took other forms including institutions such as the Underground Railway that helped escaping slaves make their way to freedom.

Abolitionists came from various communities including religious groups such as the Quakers, white anti-slavery activists such as Harriet Beecher Stowe, and former slaves and free people of color such as Frederick Douglass, Robert Purvis and James Forten. While some abolitionists called for an immediate end to slavery, others favored more gradual approaches. These included the banning of slavery in the territories, and manumission campaigns encouraging individual owners to free slaves.

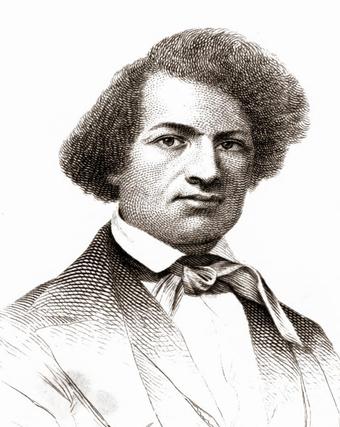

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass was a freed slave prominent abolitionist and rights advocate.

Arguments against Slavery

Abolitionists used several arguments against slavery. As early as 1688, Quakers in Germantown, Pennsylvania presented a petition to end slavery based on religious obligation and natural rights to equality. In 1774, a group of enslaved people in Massachusetts petitioned the governor against slavery used similar arguments including the natural rights of all people, the demands of Christian brotherhood, and the harsh conditions of slavery. By the 1830s, evangelical groups became quite active in the abolitionist movement including the formation of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. These groups often also supported other reform movements such as temperance movements and supports for public schools.

Early politicians and constitutional authors including Thomas Paine, Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson also had reservations about slavery because of their commitment to equal rights. However, many of these same politicians also owned slaves.

Gradual Abolition and Conflict

By 1804, most of the northern states had moved towards the abolition of slavery. although this process was quite gradual, and freed slaves were often subject to racial segregation and discrimination. Manumission campaigns in the Upper South were also successful in increasing the number of free people of color in Virginia, Maryland and Delaware where, by 1810, three-quarters of Black people in Delaware were free.

Support for slavery remained the strongest in the southern states where slavery was an important economic institution for cotton and other agricultural industries strongest in the South. The conflict over slavery became a key catalyst for the Civil War that divided northern and southern states.

5.1.2: Abolitionism and the Women’s Rights Movement

Many women involved in the early abolitionist movement went on to be important leaders in the early women’s rights and suffrage movements.

Learning Objective

Describe the relationship between the women’s rights and anti-slavery movements

Key Points

- There were many progressive movements active in the pre-civil war era. The abolition and women’s rights movement were two of the most important.

- The two movements tied together as many women involved in early abolition became leaders in the women’s rights and suffrage movements.

- The women’s rights movement applied the arguments for human rights and equality used in the abolition movement to their own lives and demanded equal consideration for women.

- There were divisions within the abolition movement over the role of women, and whether they should be subordinate, or if it was appropriate for women to take more public or leadership roles in the movement.

- While the pre-civil war women’s rights movement had few major victories it set the ground work for the suffrage campaigns that would occur in the early 20th century, along with women’s rights, feminist and women of color movements that continue today.

Key Terms

- women’s rights movement

-

the political and social actions of individuals and organizations focused on the empowerment and equal treatment of women

- suffrage

-

The right or chance to vote, express an opinion, or participate in a decision.

Progressive Pre-War Period

A wide variety of progressive movements grew up during the decades leading up to the US Civil War. The activists involved hoped to make significant changes in society, including expanding rights and freedoms to a larger group of people living in the US.

Two of the most influential were the anti-slavery or abolitionist movement, and the women’s rights movement. These were also closely related as many of the women who would go on to be leaders in the women’s rights movement got their political start in the abolitionist movement.

While many women were active in the abolitionist movement they were often kept out of public, leadership and decision making positions. For example only two women attended the Agents’ Convention of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1836. Women began to form their own abolition groups, organizing events such as the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women held in 1837. This convention brought 200 women to New York City, where they called for the immediate abolition of slavery in the US. The delegates argued for an end to slavery based on the often brutal conditions of slavery, as well as the ways in which slavery violated christian principals and basic human right to equality.

Women’s Rights Movement

Women involved in the early abolitionists movement also began to connect demands for equal right to their own lives and experiences, advocating for expanded education, employment and political rights including suffrage.

The 1848 Seneca Falls convention is one of the key early moments in the suffrage and women’s rights movement in the US. The convention was organized primarily by a group of Quaker women during a visit by Lucretia Mott, a Quaker woman well known for her role in the abolition movement and advocacy for women’s rights. The convention brought together 300 people, men and women, and produced a strong Declaration of Sentiments advocating for women’s equality including the right to vote.

The Intersection of Race and Gender

As progressive movements grew, several divisions developed often over questions of identity and especially over the role women and people of color in the movements. In terms of Abolition more incremental groups preferred advocating against the expansion of slavery, but would often stop short of calling for full or immediate abolition. Supporters of this strategy often also advocated for colonization for freed slaves, a strategy that would see emancipated people sent to colonies established in Africa, such as Liberia.

Many advocates of incremental abolition and colonization also held more traditional views on the role of women, claiming that women should play a supporting role in both the abolitionist movement and in society more generally.

A more progressive and radical strain of abolition maintained that rights and moral standing were universal, and that whether people were of African or European decent, men or women they were all due to equal treatment and rights.

A well-known exchange between Catherine Beecher and Angelina Grimké two prominent women activists and writers highlighted these two perspectives. Beecher argued women should remain subordinate by divine law in her Essay on Slavery and Abolitionism with Reference to the Duty of American Females. While Grimké asserts the rights of women to engage in all political institutions that impact their lives.

The role of Black women in the suffrage movement was also sometimes problematic. For example, both emancipated women who had been slaves and free women of color were active in the abolitionist movement, but as the women’s movement grew there was often resistance on the part of the increasingly middle class, educated, white leadership to include Black women. For example while Sojourner Truth spoke to the Women’s Convention in Akron Ohio in 1851 there were conflicting reports over how the speech was received. Some claimed delegates welcomed both the speaker and message, and others claimed that delegates were hostile to having a Black speaker address them.

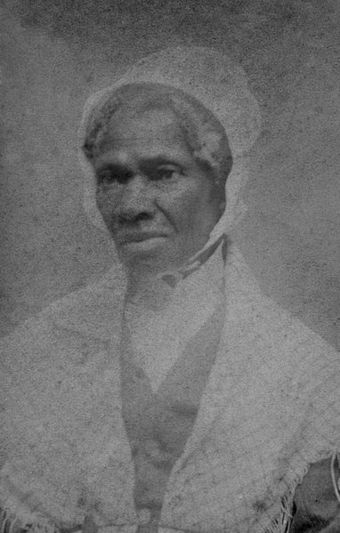

Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth who had been bom into slavery won her own freedom and became a prominent abolitionist and women’s rights advocate.

Outcomes and Legacy

While women did not gain the right to vote in all sates until 1920, there were still some victories won for women’s rights in the period leading up to the Civil War. One of the most notable was New York State granting property rights to married women. This period of activism also set the foundation for the suffrage campaigns that would occur in the early 20th century, along with women’s rights, feminist and women of color movements that continue today.

5.1.3: The Civil War Amendments

The Civil War Amendments protected equality for emancipated slaves by banning slavery, defining citizenship, and ensuring voting rights.

Learning Objective

Identify the key provisions of the three Civil War amendments

Key Points

- The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, known collectively as the Civil War Amendments, were designed to ensure equality for recently emancipated slaves.

- The 13th Amendment banned slavery and all involuntary servitude, except in the case of punishment for a crime.

- The 14th Amendment defined a citizen as any person born in or naturalized in the United States, overturning the Dred Scott V. Sandford (1857) Supreme Court ruling stating that Black people were not eligible for citizenship.

- The 15th Amendment prohibited governments from denying U.S. citizens the right to vote based on race, color, or past servitude.

Key Terms

- Emancipation Proclamation

-

An executive order issued by Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. It proclaimed the freedom of slaves in 10 states that were still in rebellion.

- Jim Crow

-

Southern United States racist and segregationist policies in the late 1800’s and early to mid 1900’s, taken collectively.

- Civil War Amendments

-

The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution.

The Civil War Amendments

The 13th (1865), 14th (1868), and 15th Amendments (1870) were the first amendments made to the U.S. constitution in 60 years. Known collectively as the Civil War Amendments, they were designed to ensure the equality for recently emancipated slaves.

While the Emancipation Proclamation ended slavery in the 10 states that were still in rebellion, many citizens were concerned that the rights granted by war-time legislation would be overturned. The Republican Party controlled congress and pushed for constitutional amendments that would be more permanent and binding. The three amendments prohibited slavery, granted citizenship rights to all people born or naturalized in the United States regardless of race, and prohibited governments from infringing on voting rights based on race or past servitude.

The 13th Amendment

This amendment explicitly banned slavery and involuntary servitude in the United States. An exception was made for punishment of a crime. This amendment also gave Congress the power to enforce the article through legislation.

The 14th Amendment

This amendment set out the definitions and rights of citizenship in the United States. The first clause asserted that anyone born or naturalized in the United States is a citizen of the United States and of the state in which they live. It also confirmed the right to due process, life, liberty, and property. This overturned the Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) Supreme Court ruling that stated that black people were not eligible for citizenship.

The amendment also defined the formula for determining political representation by apportioning representatives among states based on a count of all residents as whole persons. This contrasted with the pre-Civil War compromise that counted enslaved people as three-fifth in representation enumeration. Southern slave owners wanted slaves counted as whole people to increase the representation of southern states in Congress. Even after the 14th Amendment, native people not paying taxes were not counted for representation.

Finally, the amendment dealt with the Union officers, politicians, and debt. It banned any person who had engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the United States from holding civil or military office. Finally, it declared that no debt undertaken by the Confederacy would be assumed by the United States.

The 15th Amendment

This amendment prohibited governments from denying U.S. citizens the right to vote based on race, color, or past servitude.

While the amendment provided legal protection for voting rights based on race, there were other means that could be used to block black citizens from voting. These included poll taxes and literacy tests. These methods were employed around the country to undermine the Civil War Amendments and set the stage for Jim Crow conditions and for the Civil Rights Movement.

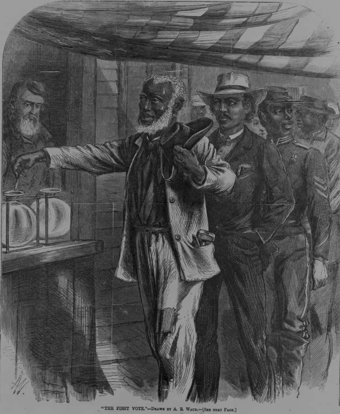

The First Vote

This image depicts the first black voters going the polls.

5.1.4: The NAACP

The NAACP, which was founded in 1909, advocates for full civil liberties and an end to racial discrimination and violence.

Learning Objective

Identify the key figures and groups working for racial equality in early twentieth-century America

Key Points

- Discrimination and violence against people of color and especially Black people continued into the 1900s, and led several groups to organize against discrimination.

- The NAACP was founded in 1909, and organized around full civil liberties and and end to racial discrimination and violence including lynching.

- The NAACP focused on local organizing with 300 branches by 1919.

- The NAACP’s worked continued to evolve and they organized campaigns around voting rights, education and employment.

Key Term

- lynching

-

Execution of a person by mob action without due process of law, especially hanging.

Organizing for Equality: The NAACP

At the beginning of the 1900s the conditions for people of color, and particularly Black people in the US were incredibly unequal. Most Black people in the US were descendants of people who had lived in slavery in the US, and particularly in the South they experienced legal segregation, limitations on civil rights and liberties, and high rates of violence including lynching. During this period several groups began organizing, particularly around defending rights won under the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth amendments. The NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) was one of these groups.

W.E.B. Du Bois and the Niagara Movement

W.E.B. Du Bois was a scholar and activist committed to full civil rights for all people. His worked extended beyond the US, and he was also a Pan-Africanist and supported anti-colonial actions in Africa and Asia.

In 1905 Du Bois along with William Monroe Trotter convened the first meeting of the Niagara Movement in Niagara Falls in Ontario. This group of Black activists and scholars called for full civil liberties and an end to racial discrimination. Their approach contrasted with other groups at the time calling for more gradual reform.

The NAACP

In 1909 the NAACP formed, the fist call for a meeting was send out by a group of white liberals appalled by the continued violence committed against Black people in the US . W.E.B. Du Bois was one of a small group of Black participants in the first meeting, and his focus on defending the rights granted in the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth amendments and eliminate race prejudice were adopted by the group.

The NAACP

W.E.B. Du Bois and Mary White Ovington were two of the founding officers of the NAACP.

The NAACP focused on recruiting members and local organizing. Branch offices were established in cities such as Washington DC, Kansas City MO, Detroit MI, and Boston MA. by 1919 they had tens of thousands of members and hundreds of local chapters.

In the early years the NAACP campaigned vigorously against lynching, voter suppression laws, for education rights, and blocked the nomination of a segregationist Supreme Court Judge. During the great depression the NAACP moved to organizing around the disproportionate impact of the depression on Black workers, and worked with willing unions to help secure jobs.

5.1.5: Litigating for Equality After World War II

Post-WWI civil rights were expanded through court rulings such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which helped integrate public schools.

Learning Objective

Describe the decision in Brown v. Board of Education

Key Points

- The period after World War II saw a great expansion in Civil Rights. This was achieved through a diversity of tactics including ongoing litigation.

- The best know case from this period is Brown v. Board of Education (1954), a Supreme Court case in which justices unanimously decided to reverse the principle of separate but equal. The decision led to the legal integration of public schools.

- While Brown v. Board of Education paved the way for integration in schools and other spheres of life, not everyone supported this decision. Many white people in southern states protested against integration and legislators thought up creative ways to get around the ruling.

Key Terms

- “Separate but Equal”

-

A legal doctrine in United States constitutional law that justified systems of segregation. Under this doctrine, services, facilities and public accommodations were allowed to be separated by race, on the condition that the quality of each group’s public facilities was to remain equal.

- Brown v. Board of Education

Litigating for Equality after World War II

The period after World War II saw a great expansion in civil rights. This was achieved through a diversity of tactics including ongoing litigation.

The best know case from this period is Brown v. Board of Education (1954), a Supreme Court case in which justices unanimously decided to reverse the principle of separate but equal. The decision led to the legal integration of public schools.

Brown v. Board of Education was a collection of cases that had been filed on the issue of school segregation from Delaware, Kansas, South Carolina and Washington DC. Each case was brought forward through NAACP local chapters. In each case except for Delaware, local courts had upheld the legality of segregation. The states represented a diversity of situations ranging from required school segregation to optional school segregation.

Segregation as Unconstitutional

Rather than focusing on whether or not segregated schools were equal, the Supreme Court ruling focused on the question of whether a doctrine of separate could ever be said to be equal. The judges’ ruling hinged on an interpretation that took separate as unconstitutional particularly because “Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law, for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. “

School Integration and Resistance

Brown v. Board of Education paved the way for integration in schools and other spheres of life, but not everyone supported this decision. Many white people in southern states protested integration, and legislators thought up creative ways to get around the ruling. This case was just one step on the road to providing full civil liberties for all people living in the United States.

Anti-Integration Protest

A 1959 rally in Little Rock AK protests the integration of the high school.

5.2: The Civil Rights Movement

5.2.1: Separate But Equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in American constitutional law that justified systems of segregation.

Learning Objective

Discuss the reasoning behind the separate of “Separate but Equal” before the Civil Rights Movement

Key Points

- Under this doctrine, services, facilities and public accommodations were allowed to be separated by race, on the condition that the quality of each group’s public facilities was to remain equal.

- Although the Constitutional doctrine required equality, the facilities and social services offered to African-Americans were almost always of lower quality than those offered to white Americans.

- The doctrine of “separate but equal” was legitimized in the 1896 Supreme Court case, Plessy v. Ferguson.

Key Term

- Reconstruction

-

A period in U.S. history from 1865 to 1877, during which the nation tried to resolve the status of the ex-Confederate states, the ex-Confederate leaders, and the Freedmen (ex-slaves) after the American Civil War.

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in American constitutional law that justified systems of segregation. Under this doctrine, services, facilities and public accommodations were allowed to be separated by race on the condition that the quality of each group’s public facilities was to remain equal.

Segregation

A store catering to “whites only” under the separate but equal doctrine.

After the end of Reconstruction in 1877, former slave-holding states enacted various laws to undermine the equal treatment of African Americans, although the 14th Amendment, as well as federal Civil Rights laws enacted after the Civil War, were meant to guarantee such treatment. Southern states contended that the requirement of equality could be met in a manner that kept the races separate. Furthermore, the state and federal courts tended to reject the pleas by African Americans that their 14th Amendment rights had been violated, arguing that the 14th amendment applied only to federal, not state, citizenship.

The doctrine of “separate but equal” was legitimized in the 1896 Supreme Court case, Plessy v. Ferguson. Homer Plessy, who was of mixed ancestry, claimed that his constitutional rights had been violated when he was forced to move to a “colored’s only car” while riding a train. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court ruling “[required] railway companies carrying passengers in their coaches in that State to provide equal, but separate, accommodations for the white and colored races…,” establishing the actual term “separate but equal” in the process. After this ruling, not only was “separate but equal” applied to railroad cars, but also schools, voting rights and drinking fountains. Segregated schools were created for students, as long as they followed “separate but equal”.

Although the Constitutional doctrine required equality, the facilities and social services offered to African-Americans were almost always of lower quality than those offered to white Americans. For example, many African-American schools received less public funding per student than nearby white schools. In Texas, the state established a state-funded law school for white students without any law school for black students.

The repeal of such laws establishing racial segregation, generally known as Jim Crow laws, was a key focus of the Civil Rights Movement prior to 1954. The doctrine of “separate but equal” was eventually overturned by the Linda Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court Case in 1954.

5.2.2: Brown v. Board of Education and School Integration

Brown v. Board of Education was a Supreme Court case which declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional.

Learning Objective

Summarize the phenomena of de jure and de facto segregation in the United States during the mid-1900s and the significance of the Brown v. Board of Education decision for the Civil Rights Movement

Key Points

- Brown v. Board of Education overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 which allowed state-sponsored segregation.

- The plaintiffs argued that systematic racial segregation, while masquerading as providing separate but equal treatment of both white and black Americans, instead perpetuated inferior accommodations, services, and treatment for black Americans.

- The key holding of the Court was that, even if segregated black and white schools were of equal quality in facilities and teachers, segregation by itself was socially and psychologically harmful to black students and therefore unconstitutional.

Key Term

- de jure

-

By right, in accordance with the law, legally.

Brown v. Board of Education was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case in which the Court declared that state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students were unconstitutional. The decision overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 that allowed state-sponsored segregation. Handed down on May 17, 1954, the Court’s unanimous (9–0) decision stated that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. ” As a result, de jure racial segregation was ruled a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. This ruling paved the way for further racial integration and was a major victory of the civil rights movement.

In 1951, a class action suit was filed against the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas in the U.S. District Court for the District of Kansas. The plaintiffs were 13 Topeka parents who, on behalf of their 20 children, called for the school district to reverse its policy of racial segregation. The plaintiffs argued that systematic racial segregation, while seeming to provide separate but equal treatment of both white and black Americans, instead perpetuated inferior accommodations, services, and treatment for black Americans. The lead plaintiff was Oliver L. Brown, whose daughter Linda had to walk six blocks to her school bus stop to ride to Monroe Elementary, her segregated black school one mile away, while Sumner Elementary, a white school, was only seven blocks from her house.

The District Court ruled in favor of the Board of Education, citing the U.S. Supreme Court precedent set in Plessy v. Ferguson, and the case moved to the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Earl Warren convened a meeting of the justices and presented to them with the argument that the only reason to sustain segregation was an honest belief in the inferiority of African-American citizens. Warren further submitted that the Court must overrule Plessy to maintain its legitimacy as an institution of liberty, and it must do so unanimously to avoid massive southern resistance. Warren drafted the basic opinion and kept circulating and revising it until the opinion was endorsed by all the members of the Court.

Eventually, the key decision of the Court was that even if segregated black and white schools were of equal quality in facilities and teachers, segregation by itself was socially and psychologically harmful to black students and, therefore, unconstitutional. This aspect was vital because the question was not whether the schools were “equal,” which under Plessy they nominally should have been, but whether the doctrine of separate was constitutional.

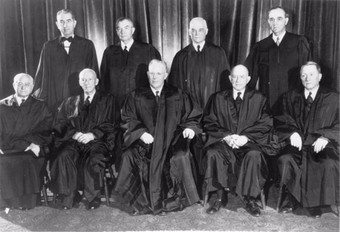

The Warren Court

The members of the Warren Court that unanimously agreed on Brown v. Board of Education.

5.2.3: Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Movement

The Civil Rights Movement aimed to outlaw racial discrimination against black Americans, particularly in the South.

Learning Objective

Differentiate between the legal strategies and “direct action” approaches used to challenge racial discrimination

Key Points

- Characteristics of the Jim Crow system included racial segregation, voter disenfranchisement, economic exploitation, and organized violence against the black community.

- After the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, civil rights organization broadened their strategy to emphasize “direct action”—primarily boycotts, sit-ins, Freedom Rides, marches and similar tactics that relied on mass mobilization, nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience.

- Key events in the Civil Rights Movement included: the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School, student sit-ins, Freedom Rides, voter registration drives, and the March on Washington.

Key Terms

- desegregation

-

the act or process of ending the separation of two groups, usually referring to race

- disenfranchisement

-

Explicit or implicit revocation of, or failure to grant the right to vote, to a person or group of people.

The African American Civil Rights Movement refers to the social movements in the United States aimed at outlawing racial discrimination against black Americans and restoring voting rights to them. The Civil Rights Movement generally lasted from 1955 to 1968 and was particularly focused in the American South.

After the period of Reconstruction, the American South maintained an entrenched system of overt, state-sanctioned racial discrimination and oppression. Characteristics of this system, also known as “Jim Crow,” included racial segregation, voter disenfranchisement, economic exploitation, and organized violence against the black community. African Americans and other racial minorities resisted this regime in numerous ways and sought better opportunities through lawsuits, new organizations (such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), political redress, and labor organizing.

After the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, civil rights organization broadened their strategy to emphasize “direct action”—primarily boycotts, sit-ins, Freedom Rides, marches and similar tactics that relied on mass mobilization, nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience. This mass action approach typified the movement from 1960 to 1968. Churches, local grassroots organizations, fraternal societies, and black-owned businesses mobilized volunteers to participate in broad-based actions. This was a more direct and potentially more rapid means of orchestrating change than the traditional approach of mounting court challenges.

Key events in the Civil Rights Movement included: the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-1956), which began when Rosa Parks, a NAACP secretary, was arrested when she refused to cede her public bus seat to a white passenger; the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School (1957); the Selma to Montgomery marches, also known as Bloody Sunday and the two marches that followed, were marches and protests held in 1965 that marked the political and emotional peak of the American civil rights movement which sought to secure voting rights for African-Americans. All three were attempts to march from Selma to Montgomery where the Alabama capitol is located. The student sit-ins protesting segregated lunch counters (1960); the Freedom Rides (1961) in which activists attempted to integrate bus terminals, restrooms, and water fountains; voter registration drives; and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (1963), in which civil rights leader, Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

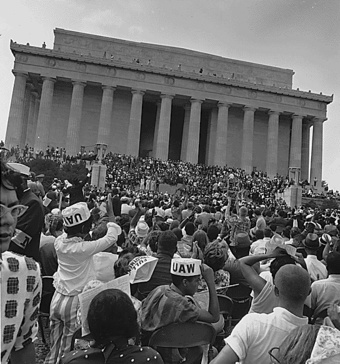

The March on Washington

The March on Washington, a key event in the U.S. Civil Rights Movement.

5.2.4: The Civil Rights Acts

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed forms of discrimination against women and minorities.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act

Key Points

- President John F. Kennedy called for the passage of the bill, though it was President Lyndon Johnson who would sign the bill into law after Kennedy’s assassination.

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964 emulated the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which established equal treatment in public accommodations.

- The Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawed discriminatory voting practices responsible for the widespread disenfranchisement of African-Americans.

Key Terms

- civil rights

-

legal or moral entitlements which are expressly enumerated in the U.S. Constitution and are considered to be unquestionable, deserved by all people under all circumstances, especially without regard to race, creed, religion, sexual orientation, gender and disabilities

- Civil Rights Act of 1964

-

a landmark piece of legislation outlawing major forms of discrimination against women as well as minorities.

- Attorney General

-

the head of the United States Department of Justice; concerned with legal affairs as the chief law enforcement officer of the United States government.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a landmark piece of United States legislation outlawing major forms of discrimination against women as well as racial, ethnic, national and religious minorities. It ended unequal application of voter registration requirements and racial discrimination in schools, at the workplace, and by facilities that served the general public.

In a civil rights speech on June 11, 1963, President John F. Kennedy called for passage of the bill, which he said would “give all Americans the right to be served in facilities which are open to the public – hotels, restaurants, theaters, retail stores, and similar establishments,” as well as “greater protection for the right to vote. ” Emulating the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which established equal treatment in public accommodations, Kennedy’s civil rights bill included provisions to ban discrimination in public accommodations. It also enabled the U.S. Attorney General to join in lawsuits against state governments which operated segregated school systems. After Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963, President Lyndon Johnson utilized his experience in legislative politics to garner support for the bill, which was passed in July 1964.

President John F. Kennedy

President John F. Kennedy, who called for the passage of a civil rights bill.

The Civil Rights Act was followed by the Voting Rights Act, signed into law by President Johnson in 1965. The Voting Rights Act outlawed discriminatory voting practices that had been responsible for the widespread disenfranchisement of African-Americans. Specifically, the Act outlawed the practice of requiring otherwise qualified voters to pass literary tests to register to vote. This was a principal means by which Southern states had prevented African-Americans from exercising the franchise.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of national legislation in the United States that prohibits discrimination in voting. Echoing the language of the 15th Amendment, the Act prohibits states and local governments from imposing any “voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure … to deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color. ” Specifically, Congress intended the Act to outlaw the practice of requiring otherwise qualified voters to pass literacy tests in order to register to vote, a principal means by which Southern states had prevented African Americans from exercising the franchise. The Act was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had earlier signed the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law.

The Act established extensive federal oversight of elections administration, providing that states and local governments with a history of discriminatory voting practices could not implement any change affecting voting without first obtaining the approval of the Department of Justice, a process known as preclearance. The Act allowed “poll watchers” to ensure state compliance with federal legislation. It also eliminated literacy tests as a precondition for voting, effectively removing barriers to African American voter registration. These enforcement provisions applied to states and political subdivisions (mostly in the South) that had used a “device” to limit voting and in which less than 50 percent of the population was registered to vote in 1964. The Act has been renewed and amended by Congress four times, the most recent being a 25-year extension signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2006.

5.2.5: Continuing Challenges in Race Relations in the U.S.

The Civil Rights Movement influenced racial integration, but tensions with affirmative action and racism still affect racial relations.

Learning Objective

Explain why racial profiling remains controversial

Key Points

- Affirmative action refers to policies that take factors including race, color, religion, gender, sexual orientation, or national origin into consideration in order to benefit underrepresented groups in areas of employment, education, and business.

- Opponents emphasize that affirmative action is counterproductive, as choosing people based on their social group instead of solely their qualifications has the effect of devaluing their accomplishments.

- Racial profiling refers to the use of an individual’s race or ethnicity by law enforcement personnel as a key factor in deciding whether to engage in enforcement.

- After Richard Nixon’s inauguration in 1969, he appointed Vice President Agnew to lead a task force, which worked with local leaders—both white and black—to determine how to integrate local schools.

- Supporters of affirmative action often cite their goals as bridging inequalities in employment and pay; increasing access to education; enriching state, institutional, and professional leadership with the full spectrum of society; and redressing apparent past wrongs, harms, or hindrances.

Key Term

- reverse discrimination

-

The policy or practice of discriminating against members of a designated group which has in the past unfairly received preferential treatment in social, legal, educational, or employment situations, with the intention of benefiting one or more other groups (such as racial, disabled, or gender groups) that have previously been discriminated against.

Continuing Challenges

Background

Though much progress has been made in establishing racial equality since the time of the Civil Rights Movement, there still exist numerous challenges in this area. Two issues relating to race that remain controversial are the debates surrounding affirmative action and racial profiling.

Affirmative action refers to policies that take factors including race, color, religion, gender, sexual orientation, or national origin into consideration in order to benefit underrepresented groups in areas of employment, education, and business. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed Executive order 11246, affirming the Federal Government’s commitment “to promote the full realization of equal employment opportunity through a positive, continuing program in each executive department and agency. “

President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon B. Johnson, who successfully utilized negative political advertising in the famous “Daisy ad” during the 1964 election

After Richard Nixon’s inauguration in 1969, he appointed Vice President Agnew to lead a task force, which worked with local leaders—both white and black—to determine how to integrate local schools. Agnew had little interest in the work, and Labor Secretary George Shultz did most of it. Federal aid was available, and a meeting with President Nixon was a possible reward for compliant committees. By September 1970, fewer than ten percent of black children were attending segregated schools. By 1971, however, tensions over desegregation surfaced in Northern cities, with angry protests over the busing of children to schools outside their neighborhood to achieve racial balance. Nixon opposed busing personally but enforced court orders requiring its use.

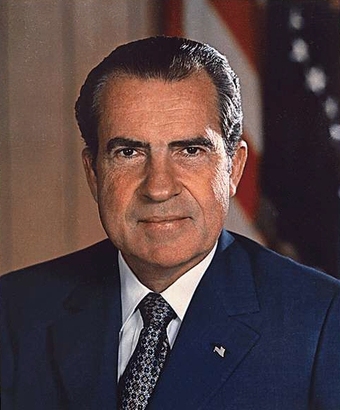

Richard Nixon, 37th President of the United States

Richard Nixon was elected president in 1968, and resigned in 1974 amidst the Watergate scandal. His presidency included foreign policy achievements, most notably improved relations with China.

In addition to desegregating public schools, Nixon implemented the Philadelphia Plan in 1970—the first significant federal affirmative action program. He also endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment after it passed both houses of Congress in 1972 and went to the states for ratification. Nixon had campaigned as an ERA supporter in 1968. However, feminists criticized him for doing little to help the ERA or their cause after his election even though he appointed more women to administration positions than Lyndon Johnson had.

Racial Profiling

Racial profiling refers to the use of an individual’s race or ethnicity by law enforcement personnel as a key factor in deciding whether to engage in enforcement (e.g. make a traffic stop or arrest). The practice is controversial and illegal in many jurisdictions. Racial profiling is challenged at a federal level by both the 4th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which guarantees the right to be safe from search and seizure without a warrant (which is to be issued “upon probable cause”); and the 14th Amendment, which requires that all citizens be treated equally under the law. Nonetheless, racial profiling is sometimes practiced in African-American, Hispanic, and Muslim communities within the U.S.

Today’s Controversy of Affirmative Action

The controversy surrounding affirmative action’s effectiveness is based on the idea of class inequality. Opponents of racial affirmative action argues that the program actually benefits middle and upper class African Americans and Hispanic Americans at the expense of lower-income European Americans and Asian Americans. This argument supports the idea of solely class-based affirmative action. America’s poor is disproportionately made up of people of color, so class-based affirmative action would disproportionately help people of color. This would eliminate the need for race-based affirmative action as well as reducing any disproportionate benefits for middle and upper class people of color.

Supporters of affirmative action often cite their goals as

- bridging inequalities in employment and pay;

- increasing access to education;

- enriching state, institutional, and professional leadership with the full spectrum of society;

- redressing apparent past wrongs, harms, or hindrances.

Opponents emphasize that affirmative action is counterproductive. They believe that choosing people based on their social group instead of solely their qualifications has the effect of devaluing their accomplishments; opponents also claim that affirmative action is a form of “reverse discrimination” and may increase racial tension.

5.3: Women’s Rights

5.3.1: The Women’s Rights Movement

The women’s rights movement refers to political struggles to achieve rights claimed for women and girls of many societies worldwide.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast the first and second waves of feminism in the United States

Key Points

- Second-wave feminism is a period of feminist activity that broadened the debate to a wide range of issues: sexuality, family, the workplace, reproductive rights, de facto inequalities, and official legal inequalities.

- The second wave of feminism in North America came as a delayed reaction against the renewed domesticity of women after World War II: the late 1940s post-war boom, which was an era characterized by unprecedented economic growth, a baby boom, and the move to family-oriented suburbs.

- In 1963, Betty Friedan wrote the bestselling book “The Feminine Mystique” in which she explicitly objected to the mainstream media image of women, stating that placing women at home limited their possibilities, and wasted talent and potential.

- The changing of social attitudes towards women is usually considered the greatest success of the women’s movement.

Key Terms

- Roe v. Wade

-

Roe v. Wade (1973) is a landmark decision by the United States Supreme Court on the issue of abortion; the Court ruled 7-2 that a right to privacy under the due process clause of the 14th Amendment extended to a woman’s decision to have an abortion, but that right must be balanced against the state’s two legitimate interests in regulating abortions: protecting prenatal life and protecting women’s health. Arguing that these state interests became stronger over the course of a pregnancy, the Court resolved this balancing test by tying state regulation of abortion to the trimesters of pregnancy.

- Betty Friedan

-

In 1963, Betty Friedan wrote the bestselling book “The Feminine Mystique” in which she explicitly objected to the mainstream media image of women, stating that placing women at home limited their possibilities, and wasted talent and potential.

- Second-Wave Feminism

-

Second-wave feminism is a period in the history of feminism in America that broadened the debate to a wide range of issues: sexuality, family, the workplace, reproductive rights, de facto inequalities, and official legal inequalities.

Example

- By the early 1980s, it was largely perceived that women had met their goals and succeeded in changing social attitudes towards gender roles, repealing oppressive laws that were based on sex, integrating “boys’ clubs” such as military academies, the United States Armed Forces, NASA, single-sex colleges, men’s clubs, and the Supreme Court, and by accomplishing the goal of making gender discrimination illegal.

Introduction

Second-wave feminism is a period of feminist activity. In the United States, second-wave feminism, initially called the Women’s Liberation Movement , began during the early 1960s and lasted through the late 1990s. It was a worldwide movement that was strong in Europe and parts of Asia, such as Turkey and Israel, where it began in the 1980s, and it began at other times in other countries.

Women’s Liberation March

Women’s Liberation march from Farrugut Square to Layfette park

Whereas first-wave feminism focused mainly on suffrage and overturning legal obstacles to gender equality (i.e. voting rights, property rights), second-wave feminism broadened the debate to a wide range of issues: sexuality, family, the workplace, reproductive rights, de facto inequalities, and official legal inequalities. At a time when mainstream women were making job gains in professions, the military, the media, and sports in large part because of second-wave feminist advocacy, second-wave feminism also focused on a battle against violence with proposals for marital rape laws, establishment of rape crisis and battered women’s shelters, and changes in custody and divorce law. Its major effort was trying to get the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) added to the United States Constitution, an effort in which they were defeated by anti-feminists led by Phyllis Schlafly, who argued against the ERA, saying women would be drafted into the military.

Historical Precedents

Starting in the late 18th century, and throughout the 19th century, rights, as a concept and claim, gained increasing political, social and philosophical importance in Europe. Movements emerged which demanded freedom of religion, the abolition of slavery, rights for women, rights for those who did not own property and universal suffrage. In the late 18th century the question of women’s rights became central to political debates in both France and Britain. At the time some of the greatest thinkers of the Enlightenment, who defended democratic principles of equality and challenged notions that a privileged few should rule over the vast majority of the population, believed that these principles should be applied only to their own gender and their own race.

Overview

The second wave of feminism in North America came as a delayed reaction against the renewed domesticity of women after World War II: the late 1940s post-war boom, which was an era characterized by an unprecedented economic growth, a baby boom, a move to family-oriented suburbs, and the ideal of companionate marriages. This life was clearly illustrated by the media of the time; for example, television shows such as “Father Knows Best” and “Leave It to Beaver” idealized domesticity.

In 1960, the Food and Drug Administration approved the combined oral contraceptive pill, which was made available in 1961. This made it easier for women to have careers without having to leave due to unexpectedly becoming pregnant. The administration of President Kennedy made women’s rights a key issue of the New Frontier, and named women (such as Esther Peterson) to many high-ranking posts in his administration.

In 1963 Betty Friedan (), influenced by Simone De Beauvoir’s book “The Second Sex,” wrote the bestselling book “The Feminine Mystique” in which she explicitly objected to the mainstream media image of women, stating that placing women at home limited their possibilities, and wasted talent and potential. The perfect nuclear family image depicted and strongly marketed at the time, she wrote, did not reflect happiness and was rather degrading for women. This book is widely credited with having begun second-wave feminism.

Betty Friedan (1960)

Betty Friedan, American feminist and writer, wrote the best selling book “The Feminist Mystique. ” This book is widely credited with having begun second-wave feminism in the United States.

Achievements

Among the most significant legal victories of the movement after the formation of the National Organization of Women (NOW) were: a 1967 Executive Order extending full Affirmative Action rights to women, Title IX and the Women’s Educational Equity Act (1972 and 1974, respectively, educational equality), Title X (1970, health and family planning), the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (1974), the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978, the outlaw of marital rape, the legalization of no-fault divorce, a 1975 law requiring U.S. Military Academies to admit women, and many Supreme Court cases, perhaps most notably Reed v. Reed of 1971 and Roe v. Wade of 1973 . However, the changing of social attitudes towards women is usually considered the greatest success of the women’s movement.

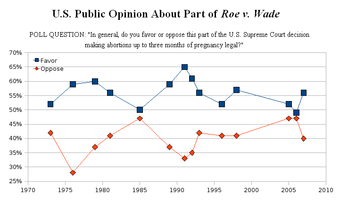

U.S. Public Opinion about Roe v. Wade

Graph showing public support for Roe v. Wade over the years

By the early 1980s, it was largely perceived that women had met their goals and succeeded in changing social attitudes towards gender roles, repealing oppressive laws that were based on sex, integrating “boys’ clubs” such as military academies, the United States Armed Forces, NASA, single-sex colleges, men’s clubs, and the Supreme Court, and by accomplishing the goal of making gender discrimination illegal. However, the movement did fail, in 1982, in adding the Equal Rights Amendment to the United States Constitution, coming up three states short of ratification.

5.3.2: Gender Discrimination

Gender discrimination refers to prejudice or discrimination based on gender, as well as conditions that foster stereotypes of gender roles.

Learning Objective

Illustrate cases of gender discrimination and stereotypes

Key Points

- Sexist attitudes are frequently based on beliefs in traditional stereotypes of gender roles, and is thus built into many societal institutions.

- Many of the stereotypes that result in gender discrimination are not only descriptive, but also prescriptive beliefs about how men and women “should” behave.

- Occupational sexism refers to discriminatory practices, statements, or actions based on a person’s gender which occur in a place of employment.

- Violence against women, including sexual assault, domestic violence, and sexual slavery, remains a serious problem around the world.

Key Terms

- objectification

-

The process or manifestation of objectifying (something).

- Gender Role

-

a set of social and behavioral norms that are generally considered appropriate for either a man or a woman in a social or interpersonal relationship.

- stereotype threat

-

the experience of anxiety or concern in a situation where a person has the potential to confirm a negative stereotype about their social group.

Gender discrimination, also known as sexism, refers to prejudice or discrimination based on sex and/or gender, as well as conditions or attitudes that foster stereotypes of social roles based on gender. Sexist mindsets are frequently based on beliefs in traditional stereotypes of gender roles, and is thus built into many societal institutions.

Gender Stereotypes

Gender stereotypes are widely held beliefs about the characteristics and behavior of women and men. Many of the stereotypes that result in gender discrimination are not only descriptive, but also prescriptive beliefs about how men and women “should” behave. For example, women who are considered to be too assertive or men who lack physical strength are often criticized and historically faced societal backlash. They can also facilitate or impede intellectual performance, such as the stereotype threat that lower women’s performance on mathematics tests, due to the stereotype that women have inferior quantitative skills compared to men’s, or when the same stereotype leads men to assess their own task ability higher than women performing at the same level.

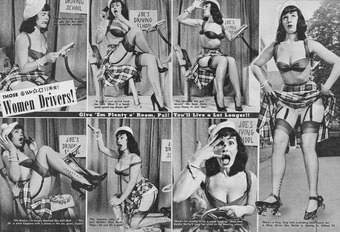

Gender stereotypes

A poster depicting gender stereotypes about women drivers from the 1950s

Examples of Gender Discrimination

There are several prominent ways in which gender discrimination continues to play a role in modern society. Occupational sexism refers to discriminatory practices, statements, and/or actions based on a person’s gender which occur in a place of employment. Wage discrimination, the “glass ceiling” (in which gender is perceived to be a barrier to professional advancement), and sexual harassment in the workplace are all examples of occupational sexism. Violence against women, including sexual assault, domestic violence, and sexual slavery, remains a serious problem around the world. Many also argue that the objectification of women, such as in pornography, also constitutes a form of gender discrimination.

5.3.3: The Women’s Suffrage Movement

The Women’s Suffrage Movement refers to social movements around the world dedicated to achieving voting rights for women.

Learning Objective

Discuss the historical events that culminated with women’s suffrage in America

Key Points

- Within the United States, the first major call for women’s suffrage took place in 1848 at the Seneca Falls Convention.

- World War I provided the final push for women’s suffrage in America, as President Wilson’s stance that the war was being fought for democracy was countered by those who felt women’s disenfranchisement prevented America from being a true democracy.

- In 1919, the Senate passed the Nineteenth Amendment, giving women the right to vote, though the amendment would not be fully ratified until 1920.

- Through a constitutional amendment, reformers pursued state-by-state campaigns to build support for, or to win, residence-based state suffrage. Towns, counties, states, and territories granted suffrage, in full or in part, throughout the 19th and early 20th century.

Key Terms

- Progressive Era

-

a period of social activism and political reform in the United States that flourished from the 1890s to the 1920s.

- suffrage

-

To have the right to vote by citizens of a particular state.

- Prohibition

-

A law prohibiting the manufacture or sale of alcohol.

Background

The Women’s Suffrage Movement refers to social movements around the world dedicated to achieving voting rights for women. Within the United States, the first major call for women’s suffrage took place in 1848 at the Seneca Falls Convention. After the Civil War agitation for the cause resumed. In 1869, the Fifteenth Amendment of the Constitution which gave black men the right to vote, split the movement. Campaigners such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton refused to endorse the amendment, as it did not give women the right to vote. Others, such as Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe, argued that if black men were enfranchised, it would help women achieve their goal.

The conflict caused two organizations to emerge, the National Woman Suffrage Association, which campaigned for women’s suffrage at a federal level and for married women to be given property rights. As well as the American Woman Suffrage Organization, which aimed to secure women’s suffrage through state legislation. After 1900, the groups made a new argument to the effect that women’s superior characteristics, especially purity, made their votes essential to promoting the reforms of the Progressive Era, particularly Prohibition, and exposing political corruption .

Women’s Suffrage

Supporters of women’s suffrage at a political rally

Women’s Suffrage in America

World War I provided the final push for women’s suffrage in America. When President Woodrow Wilson announced that the war was being fought for democracy, supporters of women’s suffrage protested that disenfranchising women prevented the United States from being a true democracy. In 1918, after years of opposition, Wilson changed his position to advocate for women’s suffrage as a war measure.

In June 1919, the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, giving women the right to vote, was brought before the Senate, and after a long discussion it was passed, with 56 ayes and 25 nays. It would take until August 1920 for enough state legislatures to ratify the amendment, thus making it the law throughout the United States.

In addition to their strategy to obtain full suffrage through a constitutional amendment, reformers pursued state-by-state campaigns to build support for, or to win, residence-based state suffrage. Towns, counties, states, and territories granted suffrage, in full or in part, throughout the 19th and early 20th century. As women received the right to vote, they began running for, and being elected to, public office. They gained positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and eventually as Members of Congress.

5.3.4: The Feminist Movement

The feminist movement refers to a series of campaigns for cultural, political, economic, and social equality for women.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast the three waves of feminism in the United States and their historical achievements

Key Points

- The history of feminist movements has been divided into three “waves” by feminist scholars.

- The first wave focused on women’s suffrage; the second wave (early 1960s to the late 1980s) was concerned with cultural and political inequalities. The third wave, (starting in the 1990s) criticizes definitions of femininity that generalize the experiences of upper-middle-class white women.

- As a whole, the feminist movement affected change in Western society, including women’s suffrage, the right to initiate divorce proceedings and “no fault” divorce, the right of women to make individual decisions regarding pregnancy, and the right to own property.

- Other important advances in the women’s movement include the founding of the National Organization for Women, as well as the development of legislation prohibiting sexual harassment or discrimination based on gender.

- While women have made strides, they still fall behind men in important measures. They are still underrepresented in Congress, and overrepresented in what have traditionally been considered “women’s” professions (such as teachers or secretaries).

- In recent times, many American women have accomplished “firsts” in the 2000s. For instance, Nancy Pelosi became the first woman to serve as Speaker of the House.

Key Terms

- feminist movement

-

The feminist movement refers to a series of campaigns for reforms on issues. such as reproductive rights, domestic violence, maternity leave, equal pay, women’s suffrage, sexual harassment, and sexual violence.

- National Organization for Women

-

The largest feminist organization in the United States. It was founded in 1966 and has 500,000 contributing members. The six core issues that NOW addresses are abortion rights/reproductive issues, violence against women, constitutional equality, promoting diversity/ending racism, lesbian rights, and economic justice.

- Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

-

A federal law enforcement agency that enforces laws against workplace discrimination. The EEOC investigates discrimination complaints based on an individual’s race, color, national origin, religion, sex, age, disability, genetic information, and retaliation for opposing a discriminatory practice.

The Feminist Movement

The feminist movement (also known as the women’s movement or women’s liberation) refers to a series of campaigns for reforms on issues, such as women’s suffrage, reproductive rights, domestic violence, maternity leave, equal pay in the workplace, maternity leave, sexual harassment, and sexual violence. The movement’s priorities vary among nations and communities.

Women constitute a majority of the population and of the electorate in the United States, but they have never spoken with a unified voice for civil rights, nor have they received the same degree of protection as racial and ethnic minorities.

History of the Movement

The history of feminist movements has been divided into three “waves” by feminist scholars. The first wave refers to the feminist movement of the nineteenth through early twentieth centuries, which focused mainly on women’s suffrage .

Feminist Suffrage Parade in New York City, May 6, 1912.

First-wave feminists marching for women’s suffrage. The first wave of women’s feminism focused on suffrage, while subsequent feminist efforts have expanded to focus on equal pay, reproductive rights, sexual harassment, and others.

The second wave, generally taking place from the early 1960s to the late 1980s, was concerned with cultural and political inequalities, which feminists perceived as being inextricably linked. The movement encouraged women to understand aspects of their own personal lives as deeply politicized and reflective of a sexist structure of power.

The third wave, starting in the 1990s, rose in response to the perceived failures of the second wave feminism. It seeks to challenge or avoid what it deems the second wave’s “essentialist” definitions of femininity, which often assumed a universal female identity and over-emphasized the experiences of upper-middle-class white women.

One of the most important organizations that formed out of the women’s rights movement is the National Organization for Women (NOW). Established in 1966 and currently the largest feminist organization in the United States, NOW works to secure political, professional, and educational equality for women. In 1972, NOW and other women activist groups fought to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the Constitution, which affirmed that women and men have equal rights under the law. Although passage failed, the women’s rights movement has made significant inroads in reproductive rights, sexual harassment law, pay discrimination, and equality of women’s sports programs in schools.

In 1980, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission defined sexual harassment as unwelcome sexual advances or sexual conduct, verbal or physical, that interferes with a person’s performance or creates a hostile working environment. Such discrimination on the basis of sex is barred in the workplace by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and in colleges and universities that receive federal funds by Title IX. In a series of decisions, the Supreme Court has ruled that employers are responsible for maintaining a harassment-free workplace. Legislation such as this has helped to protect the rights of women in the workplace and at schools. The proposed ERA did have unintended consequences. For example, stay-at-home women did not agreed necessarily with women who worked steady schedules.

The Status of Women in the United States

As a whole, the feminist movement has brought changes to U.S. society, including women’s suffrage, the right to initiate divorce proceedings and “no fault” divorce, the right of women to make individual decisions regarding pregnancy (including access to contraceptives and abortion), and the right to own property. It has also led to increased employment opportunities for women at more equitable wages, as well as broad access to university educations. The feminist movement also helped to transform family structures as a result of these increased rights, in that gender roles and the division of labor within households have gradually become more flexible.

Marxist Feminism

Rosemary Hennessy and Chrys Ingraham say that materialist feminisms grew out of Western Marxist thought and have inspired a number of different (but overlapping) movements, all of which are involved in a critique of capitalism and are focussed on ideology’s relationship to women. Marxist feminism argues that capitalism is the root cause of women’s oppression, and that discrimination against women in domestic life and employment is an effect of capitalist ideologies. Socialist feminism distinguishes itself from Marxist feminism by arguing that women’s liberation can only be achieved by working to end both the economic and cultural sources of women’s oppression. Anarcha-feminists believe that class struggle and anarchy against the state.

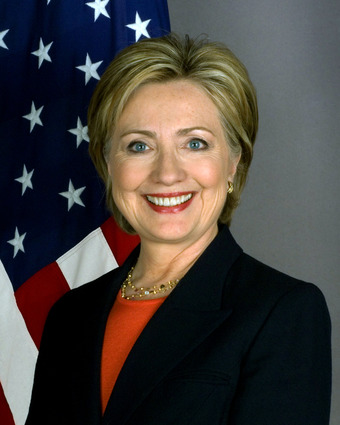

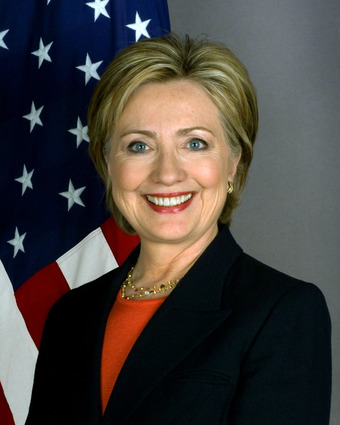

Despite this, many American women achieved many political firsts in the 2000s. In 2007, Nancy Pelosi became the first female Speaker of the House of Representatives. In 2008, Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton became the first woman to win a presidential primary, winning the New Hampshire Democratic primary . In 2008, Alaska governor Sarah Palin became the first woman nominated for Vice President by the Republican Party. In 2009 and 2010, respectively, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan were confirmed as Supreme Court Associate Justices, making them the third and fourth female justices.

Hillary Rodham Clinton

While women still fall behind men in many important measures, important exceptions exist. For example, Hillary Clinton became the first woman to become the presumptive nominee of a major political party.

5.3.5: Women in the Workplace

Women’s participation in the workforce has been a relatively recent phenomenon and is still associated with many continuing challenges.

Learning Objective

Identify the barriers for equal participation of women in the workplace

Key Points

- Particular barriers to equal participation in the workplace included a lack of access to educational opportunities; restrictions women entering or studying a field; discrimination within a field; and the expectation that mothers should be the primary childcare providers.

- Beginning in the 1970s, women began attending colleges and graduate schools in large numbers and entering professions like law, medicine, and business.

- Challenges that remain for women in the workplace include the gender pay gap, the “glass ceiling”, sexual harassment, and network discrimination.

Key Terms

- sexual harassment

-

intimidation, bullying or coercion of a sexual nature, or the unwelcome or inappropriate promise of rewards in exchange for sexual favors.

- sexism

-

or gender discrimination is prejudice or discrimination based on a person’s sex or gender. Extreme sexism may foster sexual harassment, rape and other forms of violence.

Women’s participation in the workforce has been a relatively recent phenomenon. Until modern times, legal and cultural practices, combined with the inertia of longstanding religious and educational conventions, restricted women’s entry and participation in the workforce.

Particular barriers to equal participation in the workplace included a lack of access to educational opportunities; prohibitions or restrictions on members of a particular gender entering a field or studying a field; discrimination within fields, including wage, management, and prestige hierarchies; and the expectation that mothers, rather than fathers, should be the primary childcare providers.

Within the United States, World War I and World War II provided many new opportunities for women to participate in the workplace, including jobs as secretaries, salespeople, factory workers. Beginning in the 1970s, women began attending colleges and graduate schools in large numbers and entering professions like law, medicine, and business. Many scholars attribute this trend to the advent of the birth control pill, which allowed women to postpone pregnancy and marriage and focus instead on their education and careers. This transformation of women’s expectations had a profound effect on their conception of their own identity and still continues on today.

Challenges that remain for women in the workplace include the gender pay gap, the difference between women’s and men’s earnings due to lifestyle choices and explicit discrimination; the “glass ceiling”, which prevents women from reaching the upper echelons within their companies; sexism and sexual harassment; and network discrimination, wherein recruiters for high-status jobs are generally men who hire other men.

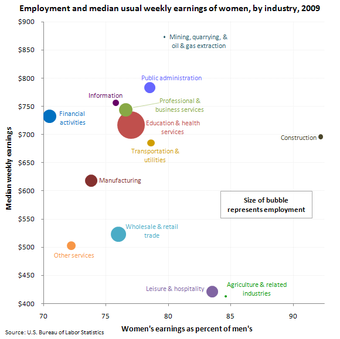

Gender pay gap

A chart depicting women’s earnings in different industries as a percentage of men’s earnings

5.3.6: Women in American Politics

In recent decades, women have served in more political posts and organizations, but they remain underrepresented in comparison to men.

Learning Objective

Analyze the role that women play in American politics, especially the involvement of African-American women in grassroots activism and institutional politics

Key Points

- As of January 2011, 35 women have served as governors of U.S. states, with six women currently serving.

- There are currently 17 female members of the Senate, 12 Democrats and 5 Republicans.

- The first woman to serve as a justice in the U.S. Supreme Court was Sandra Day O’Connor, who was appointed by President Ronald Reagan in 1981.

- African-American women have been involved in American political issues and advocating for the community since the American Civil War era through organizations, clubs, community-based social services, and advocacy.

- African-American women have been underrepresented in politics within the United States, but numbers still increase. The Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University states currently 13 African-American women serve in the 112th Congress, with 239 state legislators serving nationwide.

Key Terms

- misogyny

-

Hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against women.

- U.S. Cabinet

-

The most senior appointed officers of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States, who are generally the heads of the federal executive departments.

Background

As women campaigned for and eventually received the right to vote, they began running for, and being elected to, public office. They gained positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges and, eventually, shortly before ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, as members of Congress. In recent decades, women have been increasingly involved in American politics, serving as mayors, governors, state legislators, members of Congress, members of the U.S. Cabinet, and Supreme Court justices.

As of January 2011, 35 women have served as governors of U.S. states, with six women currently serving. The first elected female governor was Nellie Tayloe Ross of Wyoming, who was sworn in on November 4, 1925. The first female governor elected without being the wife or widow of a past state governor was Ella T. Grasso of Connecticut, sworn in on January 8, 1975.

Women in the Government Posts

The first woman elected to Congress was Jeannette Rankin, a Republican from Montana who took office in 1917. Women have been elected to the House of Representatives from 44 of the 50 states. Thirty-nine women have served altogether in the Senate, with Hattie Caraway of Arkansas became the first woman to win election to that legislative body in 1932. There are currently 17 female members of the Senate, 12 Democrats and 5 Republicans.

Twenty-five women have served as U.S. Cabinet officials. The first woman to hold a Cabinet position was Frances Perkins, who was appointed Secretary of Labor by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933. Other prominent female Cabinet members include: Janet Reno, who served as the first female attorney general under President Bill Clinton; Madeline Albright, who served as the first female secretary of state under President Clinton; Condoleezza Rice, Secretary of State under President George W. Bush; and Hillary Rodham Clinton, former First Lady, Senator from New York, Secretary of State under Barack Obama, and the first woman to be nominated for president by a major American political party.

Hillary Rodham Clinton

While women still fall behind men in many important measures, important exceptions exist. For example, Hillary Clinton became the first woman to be nominated for president by a major American political party

The first woman to serve as a justice in the U.S. Supreme Court was Sandra Day O’Connor, who was appointed by President Ronald Reagan in 1981. Three women serve in the current Supreme Court: Ruth Bader Ginsburg, appointed by President Clinton; Sonia Sotomayor, appointed by President Obama; and Elena Kagan, also appointed by President Obama.

African American women in politics

African-American women have been involved in American political issues and advocating for the community since the American Civil War era through organizations, clubs, community-based social services, and advocacy. Issues that deal with identity, racism, and sexism have been important to African-American women in the political dialogue.

Though women obtained the right to vote in the United States in 1920, many women of color still ran into obstacles. Some faced tests that required them to interpret the Constitution in order to vote. Others were threatened with physical violence, false charges, and other extreme danger to prevent voting. Due to these tactics and others that marginalized people of color, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was put into place. It outlawed any discriminatory acts to prevent people from voting.

Women and Black Power