2.1: The First American Government

2.1.1: Government in the English Colonies

The way the British government was run in the colonies inspired what the Americans would write in their Constitution.

Learning Objective

Explain the reasons for the tension between the British empire and its American colonies

Key Points

- The British government in the Americas had a locally-elected legislator with a British-appointed governor.

- The British monarchy believed it could tax the colonists without direct representation in government. The colonists believed it shouldn’t have to pay these taxes because they only had virtual representation.

- After colonial protests including the Boston Tea Party, England placed many acts restricting civil and political freedoms on the colonial governments.

Key Terms

- direct representation

-

Direct representation is a proposed form of representative democracy where each representative’s vote is weighted in proportion to the number of citizens who have chosen that candidate to represent them.

- virtual representation

-

Virtual representation stated that the members of Parliament spoke for the interests of all British subjects rather than for the interests of only the district that elected them.

Under the Kingdom of Great Britain, the American colonies experienced a number of situations which would guide them in creating a constitution. The British Parliament believed that it had the right to impose taxes on the colonists. While it did have virtual representation over the entire empire, the colonists believed Parliament had no such right as the colonists had no direct representation in Parliament . By the 1720s, all but two of the colonies had a locally elected legislature and a British appointed governor. These two branches of government would often clash, with the legislatures imposing “power of the purse” to control the British governor. Thus, Americans viewed their legislative branch as a guardian of liberty, while the executive branches was deemed tyrannical.There were several examples of royal actions that upset the Americans. For example, taxes on the importation of products including lead, paint, tea and spirits were imposed. In addition Parliament required a duty to be paid on court documents and other legal documents, along with playing cards, pamphlets and books. The variety of taxes imposed led to American disdain for the British system of government.

After the Boston Tea Party, Great Britain’s leadership passed acts that outlawed the Massachusetts legislature. The Parliament also provided for special courts in which British judges, rather than American juries, would try colonists. The Quartering Act and the Intolerable Acts required Americans provide room and board for British soldiers. Americans especially feared British actions in Canada, where civil law was once suspended in favor of British military rule.

American distaste for British government would lead to revolution. Americans formed their own institutions with political ideas gleaned from the British radicals of the early 18th century. England had passed beyond those ideas by 1776, with the resulting conflict leading to the first American attempts at a national government.

Parliament

Lionel Nathan de Rothschild (1808–1879) being introduced in the House of Commons, the lower house of Parliament, on 26 July 1858.

2.1.2: British Taxes and Colonial Grievances

The expenses from the French and Indian War caused the British to impose taxes on the American colonies.

Learning Objective

Discuss the nature of the grievances over the British empire’s taxes on the colonies

Key Points

- Parliament’s first idea repay to war debts was to charge smugglers who were violating various shipping acts.

- The Stamp Act and Sugar Act caused much protest in the colonies. The Stamp Act was repealed due to this protest.

- When Parliament refused to repeal the Tea Tax and made the colonists buy tea from the East India company, the Sons and Daughters of Liberty staged the Boston Tea Party.

Key Term

- Boston Tea Party

-

The Boston Tea Party (referred to in its time simply as “the destruction of the tea” or other informal names) was a political protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, a city in the British colony of Massachusetts. The Tea Party was held to protest the tax policy of the British government and the East India Company that controlled all the tea imported into the colonies.

After the French and Indian War, the British needed to find a way to repay war debt. They imposed new taxes and penalties to increase revenue for the kingdom. In 1764, George Grenville became the British Chancellor of the Exchequer. He allowed customs officers to obtain general writs of assistance, which allowed officers to search random houses for smuggled goods. Grenville thought that if profits from smuggled goods could be directed towards Britain, the money could help pay off debts. Colonists were horrified that they could be searched without warrant at any given moment. With persuasion from Grenville, Parliament also began to impose several new taxes on the colonists in 1764.

The Sugar Act of 1764 reduced the taxes imposed by the Molasses Act, but at the same time strengthened the collection of the tax. It also stipulated that British judges—not juries—would try Sugar Act cases. In 1765, Parliament passed the Quartering Act, which required the colonies to provide room and board for British soldiers stationed in North America. The soldiers’ main purpose was to enforce the previous acts passed by Parliament. Following the Quartering Act, Parliament passed one of the most infamous pieces of legislation: the Stamp Act.

Prior to the Stamp Act, Parliament imposed only external taxes on imports. The Stamp Act provided the first internal tax on the colonists, requiring that a tax stamp be applied to books, newspapers, pamphlets, legal documents, playing cards, and dice. The legislature of Massachusetts requested to hold a conference concerning the Stamp Act. The Stamp Act Congress met in October 1765, petitioning the King and Parliament to repeal the act before it went into effect at the end of the month. The act faced vehement opposition throughout the colonies. Merchants threatened to boycott British products. Thousands of New Yorkers rioted near the location where the stamps were stored. In Boston, the Sons of Liberty, a group led by radical statesman Samuel Adams, destroyed the home of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson. Parliament repealed the Stamp Act but passed the Declaratory Act in its wake. The Declaratory Act stated that Great Britain retained the power to tax the colonists without substantive representation.

Believing that the colonists only objected to internal taxes, Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend proposed bills that would later become the Townshend Acts. The Townshend Acts, passed in 1767, taxed imports of tea, glass, paint, lead, and even paper. Again, colonial merchants threatened to boycott taxed products. Boycotts reduced the profits of British merchants, who, in turn, petitioned Parliament to repeal the Townshend Acts. Parliament eventually agreed to repeal much of the Townshend legislation, but they refused to remove the tax on tea, maintaining that the British government retained the authority to tax the colonies.

In 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act, which exempted the British East India Company from the Townshend taxes. Thus, the East India Company gained a great advantage over other companies when selling tea in the colonies. The colonists who resented the advantages given to British companies dumped British tea overboard in the Boston Tea Party in December of 1773 .

Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was orchestrated by the Sons and Daughters of Liberty, who fiercely protested the British-imposed taxes.

2.1.3: Taxation Without Representation

“No Taxation without Representation” was the rallying cry of the colonists who were forced to pay the stamp, sugar, and tea taxes.

Learning Objective

Explain the meaning of the slogan “No Taxation without Representation”

Key Points

- “No Taxation without Representation” is an expression that revealed the colonists’ anger at paying taxes without direct representation in the British Parliament.

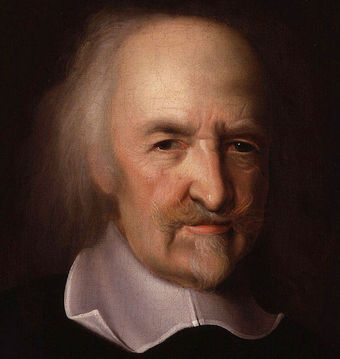

- The phrase was inspired by John Hampden during the English Civil War in response to the taxes of King Charles II.

- In modern day, the expression is used by United States citizens responding to the government’s taxes.

Key Term

- representation

-

The ability to elect a representative to speak on one’s behalf in government; the role of this representative in government.

Taxation without Representation

“No taxation without representation,” a slogan originating during the 1750s and 1760s that summarized a primary grievance of the British Colonists in the 13 colonies, was one of the major causes of the American Revolution . In short, many of these colonists believed that as they were not directly represented in the British Parliament, any laws it passed taxing the colonists (such as the Sugar Act and the Stamp Act) were illegal under the English Bill of Rights of 1689, and were a denial of their rights as Englishmen.

Sons of Liberty Propaganda

The colonists released much propaganda during this time in protest of what they said were unconstitutional policies. Here, Sons of Liberty are tarring and feathering a tax collector.

However, during the time of the American Revolution, only 1 in 20 British citizens had representation in parliament, none of whom resided in the colonies. In recent times, it has been used by several other groups in several different countries over similar disputes, including currently in some parts of the United States (see below). The phrase captures a sentiment central to the cause of the English Civil War, as articulated by John Hampden, who said, “What an English King has no right to demand, an English subject has a right to refuse.” This tax, which was only applied to coastal towns during a time of war, was intended to offset the cost of defending that part of the coast and could be paid in actual ships or the equivalent value. It was one of the causes of the English Civil War, and many British colonists in the 1750s, 1760s, and 1770s felt that it was related to their current situation.

2.1.4: The First Continental Congress

The first Continental Congress was held between 1774 and 1775 to discuss the future of the American colonies.

Learning Objective

Identify the historical role played by the Correspondence Committees during the American Revolutionary War

Key Points

- The first Continental Congress was brought together by the Virginia and Massachusetts assemblies. It was inspired by the popular Committees of Correspondence movement.

- The Congress’ first goal was neither war nor independence. It convened to to restore the union between Great Britain and the American colonies.

- In 1794, the first Congress issued a Declaration of Rights and Grievances, a precursor to the Declaration of Independence.

Key Term

- correspondence committee

-

The Committees of Correspondence were shadow governments organized by the Patriot leaders of the Thirteen Colonies on the eve of the American Revolution.

The first Continental Congress was influenced by Correspondence Committees. These served an important role in the Revolution by disseminating the colonial interpretation of British actions to the colonies and foreign governments. The Committees of Correspondence rallied opposition on common causes and established plans for collective action. The group of committees was the beginning of what later became a formal political union among the colonies. About seven to eight thousand patriots served on these committees at the colonial and local levels. These patriots comprised most of the leadership in colonial communities while the loyalists were excluded. Committee members became the leaders of the American resistance to the British. When Congress decided to boycott British products, the colonial and local Committees took charge by examining merchant records and publishing the names of merchants who attempted to defy the boycott. The Committees promoted patriotism and home manufacturing by advising Americans to avoid luxuries. The committees gradually extended their influence to many aspects of American public life.

In June 1774, the Virginia and Massachusetts assemblies independently proposed an intercolonial meeting of delegates from the several colonies to restore the union between Great Britain and the American colonies. In September, the first Continental Congress, composed of delegates from twelve of the thirteen colonies—all except Georgia—met in Philadelphia The assembly adopted what has become to be known as the Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress. The document, addressed to his Majesty and to the people of Great Britain, included a statement of rights and principles, many of which were later incorporated into the Declaration of Independence and Federal Constitution. When the first Congress adjourned, it stipulated another Congress would meet if King George III did not acquiesce to the demands set forth in the Declaration of Resolves.

Carpenter’s Hall

The first Continental Congress met in Carpenter’s Hall in Philadelphia, PA.

By the time the second Congress met, the Revolutionary War had already begun, and the issue of independence, rather than a redress of grievances, dominated the debates.

2.1.5: The Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was ushered in at the beginning of the Revolution and eventually decided American independence.

Learning Objective

Discuss the role of the Second Continental Congress during the American Revolutionary war

Key Points

- The American Revolution had already begun before the Second Continental Congress met. The Second Continental Congress was a continuation of the first, with the discussion focusing on how the colonies should respond to the king.

- By the summer of 1775, the Continental Congress began raising an army for war against Britain.

- While the Congress was not an official governing body, it took similar functions as one, such as establishing diplomats and issuing money.

Key Term

- continental congress

-

The Second Continental Congress was a convention of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that started meeting on May 10, 1775, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, soon after warfare in the American Revolutionary War had begun.

When the Second Continental Congress came together on May 10, 1775 it was, in effect, a reconvening of the First Continental Congress . Many of the same 56 delegates who attended the first meeting were in attendance at the second, and the delegates appointed the same president, Peyton Randolph, and secretary, Charles Thomson. Notable new arrivals included Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania and John Hancock of Massachusetts. Within two weeks, Randolph was summoned back to Virginia to preside over the House of Burgesses; he was replaced in the Virginia delegation by Thomas Jefferson , who arrived several weeks later. Henry Middleton was elected as president to replace Randolph, but he declined, and Hancock was elected president on May 24.

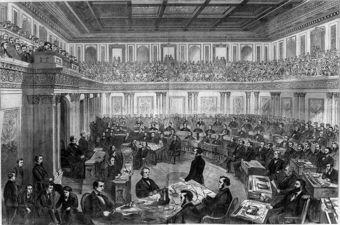

Second Continental Congress

The Congress signing the Declaration of Independence.

By the time the Second Continental Congress met, the American Revolutionary War had already started with the battles of Lexington and Concord. The Congress was to take charge of the war effort. For the first few months of the struggle, the Patriots had carried on their struggle in an ad hoc and uncoordinated manner. They had seized arsenals, driven out royal officials, and besieged the British army in the city of Boston. On June 14, 1775, the Congress voted to create the Continental Army out of the militia units around Boston and quickly appointed Congressman George Washington of Virginia as commanding general of the Continental Army. On July 6, 1775, Congress approved a Declaration of Causes outlining the rationale and necessity for taking up arms in the thirteen colonies. On July 8, Congress extended the Olive Branch Petition to the British Crown as a final attempt at reconciliation. However, it was received too late to do any good. Silas Deane was sent to France as a minister (ambassador) of the Congress. American ports were reopened in defiance of the British Navigation Acts. Although it had no explicit legal authority to govern, it assumed all the functions of a national government, such as appointing ambassadors, signing treaties, raising armies, appointing generals, obtaining loans from Europe, issuing paper money (called “Continentals”), and disbursing funds. The Congress had no authority to levy taxes, and was required to request money, supplies, and troops from the states to support the war effort. Individual states frequently ignored these requests.

2.1.6: Political Strife and American Independence

The new congress faced many roadblocks in establishing the new nation.

Learning Objective

Describe the steps taken by the Continental Congress after declaring independence from the British Empire

Key Points

- The Declaration of Independence officially cut American ties with Britain in 1776.

- The new congress initially struggled with obtaining support from the individual colonies.

- In 1776 the government went from Philadelphia to Lancaster, Pa., because of British invasion.

Key Term

- resolution

-

A statement of intent, a vow

The new Congress faced many issues during the American Revolution, including tensions with home governments, establishing legitimacy overseas, and funding a revolution without the ability to create money or tax citizens . War was also in the backdrop of the new government, and it had to move in the autumn of 1777 because the British invaded Philadelphia.

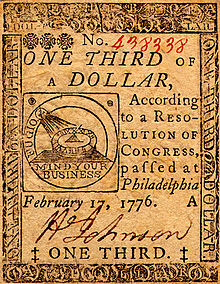

The Continental Currency

The Continental was a bill issued by Congress to fund the Revolutionary War. Over a very short period of time, the Continental became worthless.

Congress was moving towards declaring independence from the British Empire in 1776, but many delegates lacked the authority from their home governments to take such an action. Advocates of independence in Congress moved to have reluctant colonial governments revise instructions to their delegations, or even replace those governments which would not authorize independence. On May 10, 1776, Congress passed a resolution recommending that any colony lacking a proper (i.e. a revolutionary) government should form such. On May 15, Congress adopted a more radical preamble to this resolution, drafted by John Adams, in which it advised throwing off oaths of allegiance and suppressing the authority of the Crown in any colonial government that still derived its authority from the Crown. That same day the Virginia Convention instructed its delegation in Philadelphia to propose a resolution that called for a declaration of independence, the formation of foreign alliances, and a confederation of the states. The resolution of independence was delayed for several weeks as revolutionaries consolidated support for independence in their home governments.

The records of the Continental Congress confirm that the need for a declaration of independence was intimately linked with the demands of international relations. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee tabled a resolution before the Continental Congress declaring the colonies independent. He also urged Congress to resolve “to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances” and to prepare a plan of confederation for the newly independent states. Lee argued that independence was the only way to ensure a foreign alliance, since no European monarchs would deal with America if they remained Britain’s colonists. American leaders had rejected the divine right of kings in the New World, but recognized the necessity of proving their credibility in the Old World. Congress would formally adopt the resolution of independence, but only after creating three overlapping committees to draft the Declaration, a Model Treaty, and the Articles of Confederation. The Declaration announced the states’ entry into the international system; the model treaty was designed to establish amity and commerce with other states; and the Articles of Confederation established “a firm league” among the thirteen free and independent states. Together these constituted an international agreement to set up central institutions for the conduct of vital domestic and foreign affairs. Congress finally approved the resolution of independence on July 2, 1776. Congress next turned its attention to a formal explanation of this decision, the United States Declaration of Independence, which was approved on July 4 and published soon thereafter. The Continental Congress was forced to flee Philadelphia at the end of September 1777, as British troops occupied the city. The Congress moved to York, Pennsylvania, and continued their work.

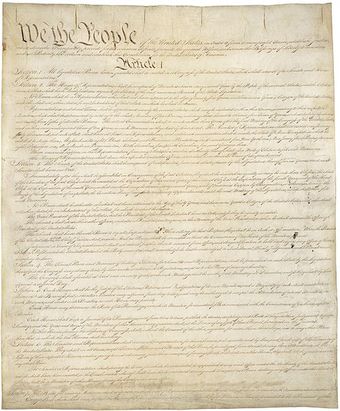

2.1.7: The Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence was a letter to the king explaining why the colonies were separating from Britain.

Learning Objective

Explain the major themes and ideas espoused by Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence

Key Points

- After the hostilities had begun, the colonies no longer believed they were a part of Britain.

- John Adams convinced the committee that Thomas Jefferson should write the final draft of the declaration.

- After the states ratified the declaration, it was widely publicized.

Key Terms

- Declaration of Independence

-

The Declaration of Independence was a statement adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, which announced that the thirteen American colonies, then at war with Great Britain, regarded themselves as independent states, and no longer a part of the British Empire.

- state

-

A political division of a federation retaining a degree of autonomy, for example one of the fifty United States. See also Province.

One of the first essential acts of the second Continental Congress, once it determined it would seek independence, was to issue a declaration to King George III confirming its separation. Each state in the congress had drafted some form of a declaration of independence, but ultimately, Thomas Jefferson was asked to write a final one which would represent all the American colonies.

The Declaration of Independence was a statement adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, which announced that the thirteen American colonies, then at war with Great Britain, regarded themselves as independent states, and no longer a part of the British Empire . John Adams had put forth a resolution earlier in the year, making a subsequent formal declaration inevitable. A committee was assembled to draft the formal declaration, to be ready when congress voted on independence. Adams persuaded the committee to select Thomas Jefferson to compose the original draft of the document, which congress would edit to produce the final version. The Declaration was ultimately a formal explanation of why Congress had voted on July 2 to declare independence from Great Britain, more than a year after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. The Independence Day of the United States of America is celebrated on July 4, the day Congress approved the wording of the Declaration.

After ratifying the text on July 4, Congress issued the Declaration of Independence in several forms. It was initially published as a printed broadside that was widely distributed and read to the public. The most famous version of the Declaration, a signed copy that is usually regarded as the Declaration of Independence, is displayed at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Although the wording of the Declaration was approved on July 4, the date of its signing was August 2. The original July 4 United States Declaration of Independence manuscript was lost while all other copies have been derived from this original document.

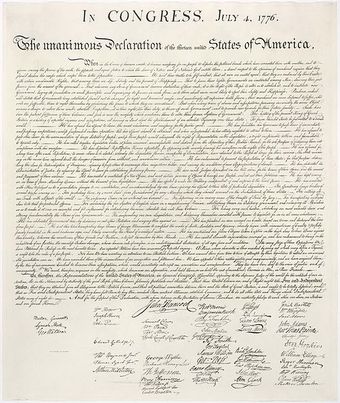

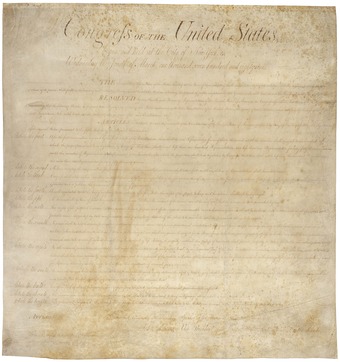

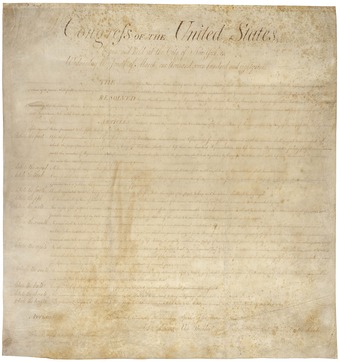

Declaration of Independence

The final declaration was drafted by Thomas Jefferson.

2.1.8: The Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation established a confederacy-type government among the new American states.

Learning Objective

Explain the historical origins and purpose of The Articles of Confederation

Key Points

- The Articles of Confederation gave little power to the central government, essentially leaving it ineffective.

- The states feared a near-tyrannical government such as the one they suffered when they were under British rule, so the head of state had only administrative power, and congress could not get money to fund the Revolutionary War from the states.

- The articles also suffered from not being able to change the articles without a unanimous vote from the states. This often was a time-consuming process during which very little was changed.

Key Term

- confederation

-

A union or alliance of states or political organizations.

The Articles of Confederation were established in 1777 by the Second Continental Congress . The Articles accomplished certain things, but without a good leader, they were bad. First, they expressly provided that the states were sovereign. (A sovereign state is a state that is both self-governing and independent. ) The United States as a Confederation was much like the present-day European Union. Each member was able to make its own laws; the entire Union was merely for the purposes of common defense.The reason for the independence of the colonies is clear–the colonies were afraid of the power of a central government such as the one in the State of Great Britain. The Articles provided that a Congress, consisting of two to seven members per state, would hold legislative power. The states, regardless of the number of Congress members representing them, each had one total vote. The Congress was empowered to settle boundary and other disputes between states. It could also establish courts with jurisdiction overseas. Also, it could tax the states, even though it did not possess the power to require the collection of these taxes by law.

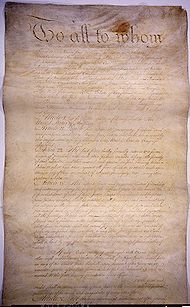

Articles of Confederation

These articles outlined the new government of the United States.

The Congress, overall, was absolutely ineffectual. The Congress had to rely on the states for its funding. Since it could not forcibly collect taxes, the states could grant or withhold money and force Congress to accept their demands. Because it could not collect taxes, Congress printed paper dollars. This policy, however, absolutely wrecked the economy because of an overabundance of paper dollars, which had lost almost all value. Several states also printed their own currency. This led to much confusion relating to exchange rates and trade; some states accepted the currency of others, while other states refused to honor bills issued by their counterparts. Furthermore, the Articles included certain fallacies. For instance, it suggested that the approval of nine states was required to make certain laws. However, it made no provision for additional states. Thus, it would appear that the number nine would be in effect even if that number would actually be a minority of states. Also, the Articles required the approval of all states for certain important decisions such as making Amendments. As the number of States would grow, securing this approval would become more and more difficult.

2.1.9: Powers of the American Government Under the Articles of Confederation

The Articles of confederation gave few but important powers of diplomacy to the American government.

Learning Objective

Discuss how power was distributed and enforced under the Articles of Confederation

Key Points

- War-making and diplomacy were the key functions of the new government.

- The Northwest Ordinance was an important agreement the government used to establish territory in the west.

- The articles allotted for a small peacetime force. Generally, however, the states had the stronger, better coordinated militias.

Key Terms

- taxation

-

The act of imposing taxes and the fact of being taxed

- ordinance

-

a local law or regulation.

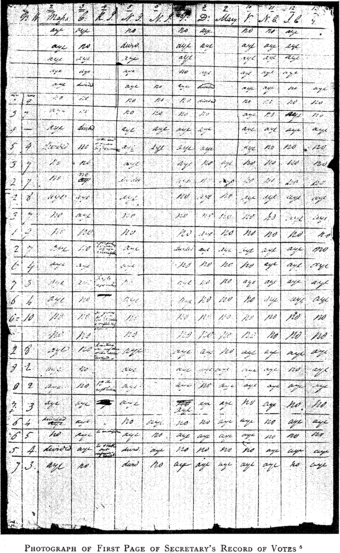

Powers of the American Government under the Articles of Confederation

The Articles supported the Congressional direction of the Continental Army, and allowed the 13 states to present a unified front when dealing with the European powers. As a tool to build a centralized war-making government, they were largely a failure, but since guerrilla warfare was a correct strategy in a war against the British Empire’s army, this failure succeeded in winning independence.

Congress could make decisions under the articles but had no power to enforce them. There was a requirement for unanimous approval before any modifications could be made to the Articles. Because the majority of lawmaking rested with the states, the central government was also kept limited. Congress was denied the power of taxation: it could only request money from the states. The states did not generally comply with the requests in full, leaving the confederation chronically short of funds.

Congress was also denied the power to regulate commerce, and as a result, the states fought over trade as well. The states and the national congress had both incurred debts during the war, and how to pay the debts became a major issue. Some states paid off their debts; however, the centralizers favored federal assumption of states’ debts. Nevertheless, the Congress of the Confederation did take two actions with lasting impact. The Land Ordinance of 1785 established the general land survey and ownership provisions used throughout later American expansion. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 noted the agreement of the original states to give up western land claims and cleared the way for the entry of new states .

Love Canal

This 1978 protest at Love Canal was one of the early events in the environmental justice movement.

Once the war was won, the Continental Army was largely disbanded. A very small national force was maintained to man frontier forts and protect against Indian attacks. Meanwhile, each of the states had an army (or militia), and 11 of them had navies. The wartime promises of bounties and land grants to be paid for service were not being met. In 1783, Washington defused the Newburgh conspiracy, but riots by unpaid Pennsylvania veterans forced the Congress to temporarily leave Philadelphia.

Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance was one of the few accomplishments under the Articles of Confederation.

2.1.10: Impact of the Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation, while riddled with problems, did have lasting effects.

Learning Objective

Identify the strengths and weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation

Key Points

- The Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance were land-planning orders, and they helped expand the Untied States westward.

- The government under the articles were ineffective diplomatically: It took months before the government could plan the Paris peace talks to end the Revolutionary War.

- The government also could not tax the states or make the states pay their war debts. It also could not regulate inter-state commerce.

Key Term

- imperial colonization

-

The policy of forcefully extending a nation’s authority by territorial gain or by the establishment of economic and political dominance over other nations.

The Confederation Congress did take two actions with long-lasting impact. The Land Ordinance of 1785 and Northwest Ordinance created a territorial government, set up protocols for the admission of new states and the division of land into useful units and set aside land in each township for public use. This system represented a sharp break from imperial colonization, as in Europe, and provided the basis for the rest of American continental expansion throughout the nineteenth century.

The Land Ordinance of 1785 established both the general practices of land surveying in the west and northwest and the land ownership provisions used throughout the later westward expansion beyond the Mississippi River. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 noted the agreement of the original states to give up northwestern land claims and organized the Northwest Territory, thereby clearing the way for the entry of five new states and part of a sixth to the Union. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 also made great advances in the abolition of slavery. New states admitted to the Union in said territory would never be slave states.To be specific, these states gave up all of their claims to land north of the Ohio River and west of the (present) western border of Pennsylvania: Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. From this land, over several decades, new states were formed: Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and the part of Minnesota east of the Mississippi River. By the Land Ordinance of 1785, these were surveyed into the now familiar squares of land called the “township” (36 square miles), the “section” (one square mile), and the “quarter section” (160 acres) . This system was carried forward to most of the states west of the Mississippi (excluding areas of Texas and California that had already been surveyed and divided up by the Spanish Empire). Then, when the Homestead Act was enacted in 1867, the quarter section became the basic unit of land that was granted to new settler farmers.

Public interest groups

Public interest groups advocate for issues that impact the general public, such as education.

The Treaty of Paris (1783), which ended hostilities with Great Britain, languished in Congress for months because state representatives failed to attend sessions of the national legislature. Yet, Congress had no power to enforce attendance. Also, the Confederation faced several difficulties in its early years. Firstly, Congress became extremely dependent on the states for income. Also, states refused to require its citizens to pay debts to British merchants, straining relations with Great Britain. France prohibited Americans from using the important port of New Orleans, crippling American trade down the Mississippi river.

Under the Articles of Confederation, the central government’s power was kept quite limited. The Confederation Congress could make decisions but lacked enforcement powers. Implementation of most decisions, including modifications to the articles, required unanimous approval of all 13 state legislatures. Congress was denied any powers of taxation. It only could request money from the states. The states often failed to meet these requests in full, leaving both Congress and the Continental Army chronically short of money. As more money was printed by Congress, the continental dollars depreciated. In 1779, George Washington wrote to John Jay, who was serving as the president of the Continental Congress, “that a wagon load of money will scarcely purchase a wagon load of provisions. ” Mr. Jay and the Congress responded in May by requesting $45 million from the states. In an appeal to the states to comply, Jay wrote that the taxes were “the price of liberty, the peace, and the safety of yourselves and posterity. ” He argued that Americans should avoid having it said “that America had no sooner become independent than she became insolvent” or that “her infant glories and growing fame were obscured and tarnished by broken contracts and violated faith. ” The states did not respond with any of the money requested from them. Congress also had been denied the power to regulate either foreign trade or interstate commerce and, as a result, all of the states maintained control over their own trade policies. The states and the Confederation Congress both incurred large debts during the Revolutionary War, and how to repay those debts became a major issue of debate following the war. Some states paid off their war debts and others did not.

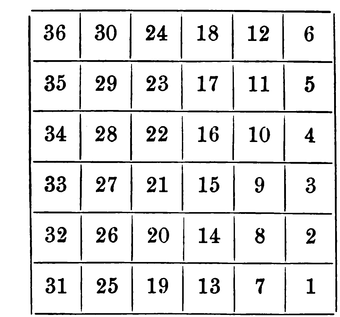

Land Ordinance, 1785

These units were the basis for separating land. By the Land Ordinance of 1785, these were surveyed into the now familiar squares of land called the “township” (36 square miles), the “section” (one square mile), and the “quarter section” (160 acres).

2.1.11: Shay’s Rebellion and the Revision of the Articles of Confederation

Shays’ rebellion prompted the Boston elite and members of the central government to question the strength of the American government.

Learning Objective

Discuss the historical conditions that prompted Shay’s Rebellion and its impact on the Articles of Confederation

Key Points

- Shay was a farmer who led a rebellion after he was put in jail because he could not pay state taxes. He and a group of supporters protested. The federal government could not stop these mass protests and had to beg the Massachusetts militia to do so.

- Many figuredheads of the time debated the revolution. Thomas Jefferson supported it, while Henry Knox and George Washington were appalled by Shays’ actions.

- Elites began to think that a convention discussing the Articles should be held, though others worried such conventions would undermine the government.

Key Term

- inflation

-

An increase in the general level of prices or in the cost of living.

Shays’ Rebellion and the Revision of the Articles

Due to the post-revolution economic woes and agitated by inflation, many worried about social instability. This was especially true for those in Massachusetts. The legislature’s response to the shaky economy was to put emphasis on maintaining a sound currency by paying off the state debt through levying massive taxes. The tax burden hit those with moderate incomes dramatically. The average farmer paid a third of their annual income to these taxes from 1780 to 1786. Those who couldn’t pay had their property foreclosed and they were thrown into crowded prisons filled with other debtors.

In the summer of 1786, a Revolutionary War veteran named Daniel Shays began to organize western communities in Massachusetts to forcibly stop foreclosures by prohibiting the courts from holding their proceedings. Later that fall, Shays marched the newly formed “rebellion” into Springfield to stop the state supreme court from gathering . The state responded with troops sent to suppress the rebellion. After a failed attempt by the rebels to attack the Springfield arsenal, and the failure of other small skirmishes, the rebels retreated and then uprising collapsed.

Daniel Shays

Shays and colleague Job Shattuck

Shays retreated to Vermont by 1787. While Daniel Shays was in hiding, the government condemned him to death on the charge of treason. Shays pleaded for his life in a petition that was finally granted by John Hancock on June 17, 1788. Thomas Jefferson, who was serving as ambassador to France at the time, refused to be alarmed by Shays’ Rebellion. In a letter to a friend, he argued that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing. “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure. “

In contrast to Jefferson’s sentiments George Washington, who had been calling for constitutional reform for many years, wrote in a letter to Henry Lee, “You talk, my good sir, of employing influence to appease the present tumults in Massachusetts. I know not where that influence is to be found, or, if attainable, that it would be a proper remedy for the disorders. Influence is not government. Let us have a government by which our lives, liberties, and properties will be secured, or let us know the worst at once. “

At the time of the rebellion, the weaknesses of the federal government as constituted under the Articles of Confederation were apparent to many. A vigorous debate was going on throughout the states on the need for a stronger central government with Federalists arguing for the idea, and anti-Federalists opposing them. Historical opinion is divided on what sort of role the rebellion played in the formation and later ratification of the United States Constitution, although most scholars agree it played some role, at least temporarily drawing some anti-Federalists to the strong government side. By early 1785, many influential merchants and political leaders were already agreed that a stronger central government was needed.

Delegates from five states held a convention in Annapolis, Maryland in September 1786. They concluded that vigorous steps needed to be taken to reform the federal government, but it disbanded because of a lack of full representation. The delegates called for a convention consisting of all the states to be held in Philadelphia in May 1787. Historian Robert Feer notes that several prominent figures had hoped the convention would fail, requiring a larger-scale convention. French diplomat Louis-Guillaume Otto thought the convention was intentionally broken off early to achieve this end.

In early 1787 John Jay wrote that the rural disturbances and the inability of the central government to fund troops in response made “the inefficiency of the Federal government [become] more and more manifest. ” Henry Knox observed that the uprising in Massachusetts clearly influenced local leaders who had previously opposed a strong federal government.

Historian David Szatmary writes that the timing of the rebellion “convinced the elites of sovereign states that the proposed gathering at Philadelphia must take place. ” Some states, Massachusetts among them, delayed choosing delegates to the proposed convention partly because in some ways it resembled the “extra-legal” conventions organized by the protestors before the rebellion became violent.

2.1.12: The Annapolis Convention

The Annapolis Convention, led by Alexander Hamilton, was one of two conventions that met to amend the Articles of Confederation.

Learning Objective

Discuss the impact of the Annapolis Convention on the U.S. Constitution

Key Points

- Alexander Hamilton called delegates to Annapolis, Maryland to discuss ways to amend the Articles of Confederation so the government would run more effectively.

- Of the thirteen states, only five send representatives. The representatives met in September of 1786 but did not proceed because of the low representation. Instead, they suggested that a group of delegates meet in Philadelphia that following May.

- At the Philadelphia Convention in May 1787, the delegates created the United States Constitution.

Key Term

- Annapolis Convention

-

The Annapolis Convention was a meeting in 1786 in Annapolis, Maryland, where twelve delegates from five states (New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Virginia) met and unanimously called for a constitutional convention.

Long dissatisfied with the weak Articles of Confederation, Alexander Hamilton of New York played a major leadership role in drafting a resolution for a constitutional convention, which was later to be called the Annapolis Convention. Hamilton’s efforts brought his desire to have a more powerful, more financially independent federal government one step closer to reality .

Alexander Hamilton

Hamilton called the Annapolis Convention together and played a prominent role in the Philadelphia Convention the following year.

The defects that the convention was to remedy were those barriers that limited trade or commerce between the largely independent states under the Articles of Confederation. The convention, named A Meeting of Commissioners to Remedy Defects of the Federal Government, met from September 11 to September 14, 1786. “New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and North Carolina had appointed commissioners who failed to arrive in Annapolis in time to attend the meeting, while Connecticut, Maryland, South Carolina and Georgia had taken no action at all. Because of the small representation, the Annapolis Convention did not deem “it advisable to proceed on the business of their mission. ” After an exchange of views, the Annapolis delegates unanimously submitted a report to their respective States in which they suggested that a convention of representatives from all the States meet at Philadelphia on the second Monday in May, 1787. The report expressed the hope that more states would be represented and that their delegates or deputies would be authorized to examine areas broader than simply commercial trade. At the resulting Philadelphia Convention of 1787, delegates produced the United States Constitution.

2.2: The Constitutional Convention

2.2.1: The Constitutional Convention

The Constitutional Convention was established in 1787 to replace the Articles of Confederation with a national constitution for all states.

Learning Objective

Discuss the circumstances leading to the Constitutional Convention and the replacement of the Articles of Confederation

Key Points

- The Constitutional Convention took place from May 14 to September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to address problems in governing the United States of America, which had been operating under the Articles of Confederation following independence from Great Britain.

- The Articles of Confederation was an agreement among the 13 founding states that established the United States of America as a confederation of sovereign states. It soon become evident to nearly all that it was inadequate for managing the various conflicts that arose among the states.

- Several plans were introduced at the Constitutional Convention. The Virginia Plan, inspired by James Madison, proposed that both houses of the legislature would be determined proportionately. The lower house would be elected by the people, and the upper house would be elected by the lower house.

- In contrast to the Virginia Plan, the New Jersey Plan proposed a unicameral legislature with one vote per state. Inherited from the Articles of Confederation, this position reflected the belief that the states were independent entities.

- To resolve this stalemate, the Connecticut Compromise blended the Virginia and New Jersey proposals. Ultimately, its main contribution was in determining the apportionment of the Senate. What was ultimately included in the Constitution was a modified form of this plan.

- Among the most controversial issues confronting the delegates was that of slavery. The Three-Fifths Compromise established that three-fifths of the population of slaves would be counted in relation to the distribution of taxes and the apportionment of the members of the House of Representatives.

Key Terms

- new jersey plan

-

Under the New Jersey Plan, the unicameral legislature with one vote per state was inherited from the Articles of Confederation. This position reflected the belief that the states were independent entities and as they entered the United States of America freely and individually, so they remained.

- virginia plan

-

Virginia Plan was a proposal by Virginia delegates for a bicameral legislative branch. Prior to the start of the Convention, the Virginian delegates met and, drawing largely from Madison’s suggestions, drafted a plan.

- constitutional convention

-

The Constitutional Convention took place from May 14 to September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to address problems in governing the United States of America, which had been operating under the Articles of Confederation following independence from Great Britain.

Introduction

The Constitutional Convention took place from May 14 to September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The convention was held to address problems in governing the United States, which had been operating under the Articles of Confederation following independence from Great Britain. Although the convention was intended to revise the Articles of Confederation, the intention from the outset of many of its proponents, chief among them James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, was to create a new government rather than fix the existing one. The delegates elected George Washington to preside over the convention. The result of the convention was the United States Constitution, placing the convention among the most significant events in the history of the United States .

Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia

“Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States,” by Howard Chandler Christy (1940).

The Convention

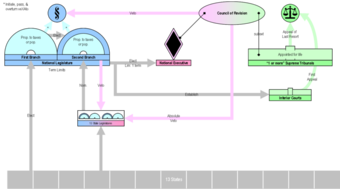

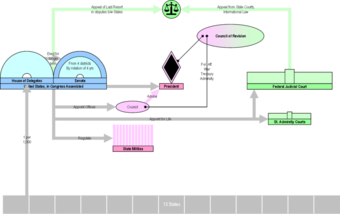

At the Convention, several plans were introduced. James Madison’s plan, known as the Virginia Plan, was the most important plan. The Virginia Plan was a proposal by Virginia delegates for a bicameral legislative branch. Prior to the start of the Convention, the Virginian delegates met and, drawing largely from Madison’s suggestions, drafted a plan . In its proposal, both houses of the legislature would be determined proportionately. The lower house would be elected by the people, and the upper house would be elected by the lower house. The executive branch would exist solely to ensure that the will of the legislature was carried out and, therefore, would be selected by the legislature.

Virginia Plan

Visual representation of the structure of James Madison’s Virginia Plan.

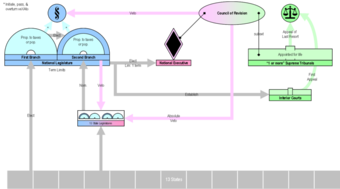

After the Virginia Plan was introduced, New Jersey delegate William Paterson asked for an adjournment to contemplate the plan. Under the Articles of Confederation, each state had equal representation in Congress, exercising one vote each. Paterson’s New Jersey Plan was ultimately a rebuttal to the Virginia Plan. Under the New Jersey Plan, the unicameral legislature with one vote per state was inherited from the Articles of Confederation . This position reflected the belief that the states were independent entities and as they entered the United States of America freely and individually, so they remained.

New Jersey Plan

Visual representation of the structure of the New Jersey Plan.

To resolve this stalemate, the Connecticut Compromise, forged by Roger Sherman from Connecticut, was proposed on June 11. In a sense, it blended the Virginia (large-state) and New Jersey (small-state) proposals. Ultimately, however, its main contribution was in determining the apportionment of the Senate and, thus, retaining a federal character in the constitution. What was ultimately included in the constitution was a modified form of this plan.

Slavery

Among the most controversial issues confronting the delegates was that of slavery. Slavery was widespread in the states at the time of the Convention. Twenty-five of the Convention’s 55 delegates owned slaves, including all of the delegates from Virginia and South Carolina. Whether slavery was to be regulated under the new Constitution was a matter of such intense conflict between the North and South that several Southern states refused to join the Union if slavery were not to be allowed.

Whether slavery was to be regulated under the new Constitution was a matter of such intense conflict between the North and South that several Southern states refused to join the Union if slavery were not to be allowed. Delegates opposed to slavery were forced to yield in their demands that slavery practiced within the confines of the new nation be completely outlawed. However, they continued to argue that the Constitution should prohibit the states from participating in the international slave trade, including in the importation of new slaves from Africa and the export of slaves to other countries. The Convention postponed making a final decision on the international slave trade until late in the deliberations because of the contentious nature of the issue. Once the Convention had finished amending the first draft from the Committee of Detail, a new set of unresolved questions were sent to several different committees for resolution.

During the Convention’s late July recess, the Committee of Detail had inserted language that would prohibit the federal government from attempting to ban international slave trading, and from imposing taxes on the purchase or sale of slaves. This committee helped work out a compromise: In exchange for this concession, the federal government’s power to regulate foreign commerce would be strengthened by provisions that allowed for taxation of slave trades in the international market and that reduced the requirement for passage of navigation acts from two-thirds majorities of both houses of Congress to simple majority.

The Three-Fifths Compromise was a compromise between Southern and Northern states reached during the Philadelphia Convention of 1787 in which three-fifths of the enumerated population of slaves would be counted for representation purposes regarding both the distribution of taxes and the apportionment of the members of the United States House of Representatives. It was proposed by delegates James Wilson and Roger Sherman. This was eventually adopted by the Convention.

2.2.2: The Framers of the Constitution

The Framers of the Constitution were delegates to the Constitutional Convention who took part in drafting the proposed U.S. Constitution.

Learning Objective

Describe the composition of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention

Key Points

- The Founding Fathers of the United States of America were political leaders and statesmen who participated in the American Revolution by signing the United States Declaration of Independence, taking part in the American Revolutionary War, and establishing the United States Constitution.

- In 1973, historian Richard B. Morris identified seven key Founding Fathers: John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and George Washington.

- In the winter and spring of 1786–1787, twelve of the thirteen states chose a total of seventy-four delegates to attend what is now known as the Constitutional Convention. Of these seventy-four delegates, only fifty-five helped to draft what would become the Constitution of the United States.

- More than half of the delegates had trained as lawyers, although only about a quarter practiced law as their principal means of business. Other professions included merchants, manufacturers, shippers, land speculators, bankers or financiers, three physicians, a minister, and several small farmers.

- Several notable founders did not participate in the Constitutional Convention. Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Patrick Henry, John Hancock and Samuel Adams did not attend the Convention.

Key Terms

- founding fathers

-

The Founding Fathers of the United States of America were political leaders and statesmen who participated in the American Revolution by signing the United States Declaration of Independence, taking part in the American Revolutionary War, and establishing the United States Constitution.

- constitutional convention

-

The Constitutional Convention took place from May 14 to September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to address problems in governing the United States of America, which had been operating under the Articles of Confederation following independence from Great Britain.

- last of the romans

-

Term used to refer to the last remaining founders who lived well into the nineteenth century.

Introduction

The Founding Fathers of the United States of America were political leaders who participated in the American Revolution. They signed the Declaration of Independence, took part in the Revolutionary War, and established the Constitution. The “Founding Fathers” included two major groups. The Signers of the Declaration of Independence signed the United States Declaration of Independence in 1776. The Framers of the Constitution were delegates to the Constitutional Convention and helped draft the Constitution of the United States .

Framers of the Constitution Stamp (1937)

US Postage Stamp depicting delegates at the signing of the US Constitution.

Some historians consider the “Founding Fathers” to be a larger group, which includes not only the Signers and the Framers but also ordinary citizens who took part in winning American independence and creating the United States of America. In 1973, historian Richard B. Morris identified seven figures as the main Founding Fathers: John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and George Washington.

Delegates to the Constitutional Convention

In 1786–1787, twelve of the thirteen states—all but Rhode Island—chose seventy-four delegates to attend what is now known as the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia (). Nineteen of these delegates chose not to accept election or attend the debates. The states had originally appointed seventy representatives to the Convention, but a number of the appointees did not accept or could not attend, leaving fifty-five delegates to draft the Constitution. Almost all of these delegates had taken part in the Revolution. At least twenty-nine of the delegates served in the Continental forces. Most of the delegates had been members of the Confederation Congress, and many had been members of the Continental Congress.

Occupations and Experience

The framers of the Constitution had extensive political experience. By 1787, four-fifths of the delegates had been in the Continental Congress. Nearly all of the fifty-five delegates had experience in colonial and state government. Furthermore, the delegates practiced a wide range of high- and middle-status occupations. Many delegates pursued more than one career simultaneously. They did not differ dramatically from the Loyalists, except the delegates were generally younger in their professions.

More than half of the delegates had trained as lawyers, although only about a quarter had practiced law as their principal career. Other professions included merchants, manufacturers, shippers, land speculators, bankers or financiers, three physicians, a minister, and several small farmers. Of the twenty-five who owned slaves, sixteen depended on slave labor to run the plantations or other businesses that formed the mainstay of their income. Most of the delegates were landowners with substantial holdings, and most were comfortably wealthy. George Washington and Governor Morris were among the wealthiest men in the entire country.

The Founding Fathers had strong educational backgrounds at some of the colonial colleges or abroad. Some, like Franklin and Washington, were largely self-taught or learned through apprenticeship. Others had obtained instruction from private tutors or at academies. About half of the men had attended or graduated from college. Some men held medical degrees or advanced training in theology. Most delegates were educated in the colonies, but several were lawyers who had been trained at the Inns of Court in London.

Notable Absences and Post-Convention Careers

Several notable Founders did not participate in the Constitutional Convention. Thomas Jefferson was abroad, serving as the minister to France. John Adams was in Britain, serving as minister to that country, but he wrote home to encourage the delegates. Patrick Henry refused to participate because he “smelt a rat in Philadelphia, tending toward the monarchy. ” John Hancock and Samuel Adams were also absent. Many of the states’ older and more experienced leaders may have simply been too busy to attend the Convention.

Most were successful in subsequent careers, although seven suffered serious financial reverses that left them in or near bankruptcy. Most of the group continued to render public service, particularly to the new government they had helped to create. The last remaining founders, also called the “Last of the Romans”, lived well into the nineteenth century.

2.2.3: Constitutional Issues and Compromises

At the Constitutional Convention, the Virginia, Pinckney, New Jersey, and Hamilton plans gave way to the Connecticut Compromise.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast the U.S. Constitution with the Articles of Confederation.

Key Points

- Inspired by proposals at the Constitutional Convention, The Virginia Plan proposed a legislative branch consisting of two chambers. Rotation in office and recall were two principles applied to the lower house of the national legislature.

- Under the Pinckney Plan, the House would have one member for every one thousand inhabitants. The House would also elect Senators who would serve by rotation for four years. Congress would meet in a joint session to elect a President, and it would also appoint members of the cabinet.

- Under the New Jersey Plan, the unicameral legislature with one vote per state was inherited from the Articles of Confederation. Unlike the Virginia Plan, this plan favored small states by giving one vote per state.

- Alexander Hamilton’s plan advocated doing away with much state sovereignty and consolidating the states into a single nation. The plan was perceived as a well-thought-out plan, but it was not considered because it resembled the British system too closely.

- The Connecticut Compromise blended the Virginia (large-state) and New Jersey (small-state) proposals. Its main contribution was in determining the method for apportionment of the Senate and retaining a federal character in the constitution.

Key Terms

- hamilton’s plan

-

Proposed by Alexander Hamilton to the Constitutional Convention, this plan advocated doing away with much state sovereignty and consolidating the states into a single nation. The plan was perceived as a well-thought-out plan, but it was not considered because it resembled the British system too closely.

- pinckney plan

-

The Pinckney Plan refers to the proposal by Charles Pinckney of South Carolina to the Constitutional Convention. It advanced a bicameral legislature made up of a Senate and a House of Delegates. The House would have one member for every one thousand inhabitants. The House would elect Senators who would serve by rotation for four years and represent one of four regions.

- virginia plan

-

Virginia Plan was a proposal by Virginia delegates for a bicameral legislative branch. Prior to the start of the Convention, the Virginian delegates met and, drawing largely from Madison’s suggestions, drafted a plan.

Introduction

At the Constitutional Convention, several plans were introduced. Debate topics included the composition of the Senate, how “proportional representation” was to be defined, whether the executive branch would be composed of one person or three, presidential term lengths and method of election, impeachable offenses, a fugitive slave clause, whether to abolish slave trade, and whether judges should be chosen by the legislature or executive.

The Virginia Plan

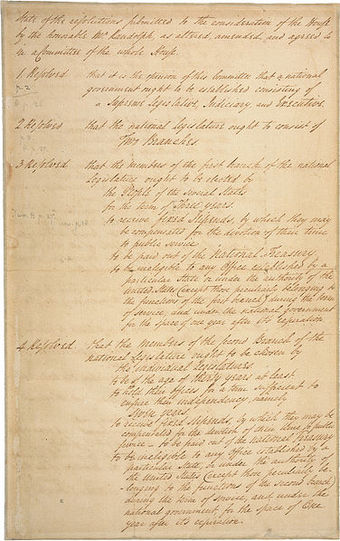

While waiting for the Convention to formally begin, James Madison sketched out his initial draft, which became known as the Virginia Plan. It also reflected his views as a strong nationalist . The Virginia Plan was a proposal by Virginia delegates for a bicameral legislative branch . Prior to the start of the Convention, the Virginian delegates met and, drawing largely from Madison’s suggestions, drafted a plan. The Virginia Plan proposed a legislative branch consisting of two chambers. Rotation in office and recall were two principles applied to the lower house of the national legislature. Each of the states would be represented in proportion to their “Quotas of contribution, or to the number of free inhabitants.” States with a large population, like Virginia, would thus have more representatives than smaller states.

The Virginia Plan

The front page of the Virginia Plan document.

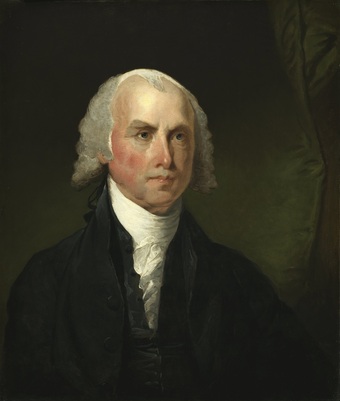

Portrait of James Madison

Stippling engraving of James Madison, President of the United States, done between 1809 and 1817.

The Plan of Charles Pinckney

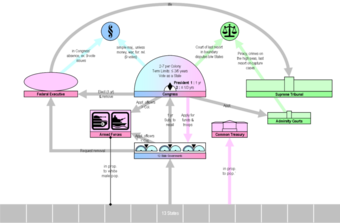

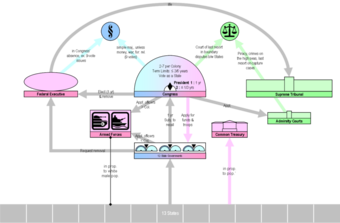

Immediately after Randolph finished laying out the Virginia Plan, Charles Pinckney of South Carolina presented his own plan to the Convention . As Pinckney did not reduce it to writing, the only evidence we have are Madison’s notes, so the details are somewhat scarce. It was a confederation, or treaty, among the thirteen states. There was to be a bicameral legislature made up of a Senate and a House of Delegates. The House would have one member for every one thousand inhabitants. The House would elect Senators who would serve by rotation for four years and represent one of four regions. Congress would meet in a joint session to elect a President, and it would also appoint members of the cabinet. Congress, in joint session, would serve as the court of appeal of last resort in disputes between states. Pinckney did also provide for a supreme Federal Judicial Court. The Pinckney plan was not debated, but it may have been referred to by the Committee of Detail for early draft.

Pinckney Plan

The Pinckney Plan proposed a bicameral legislature made up of a Senate and a House of Delegates. The House would have one member for every one thousand inhabitants. The House would elect Senators who would serve by rotation for four years and represent one of four regions. Congress would meet in a joint session to elect a President, and would also appoint members of the cabinet. Congress, in joint session, would serve as the court of appeal of last resort in disputes between states.

New Jersey Plan

After the Virginia Plan was introduced, New Jersey delegate William Paterson asked for an adjournment to contemplate the plan. Under the Articles of Confederation, each state had equal representation in Congress—one vote per state. Paterson’s New Jersey Plan was ultimately a rebuttal to the Virginia Plan. Under the New Jersey Plan, the unicameral legislature with one vote per state was inherited from the Articles of Confederation. This position reflected the belief that the states were independent entities that could enter and leave the United States on their own volition.

Hamilton’s Plan

Unsatisfied with the New Jersey Plan and the Virginia Plan, Alexander Hamilton proposed his own plan. It also was known as the British Plan, because of its resemblance to the British system of strong centralized government. Hamilton’s plan advocated doing away with much state sovereignty and consolidating the states into a single nation. The plan featured a bicameral legislature, the lower house elected by the people for three years. The upper house would be elected by electors chosen by the people and would serve for life. The plan also gave the Governor, an executive elected by electors for a life-term of service, an absolute veto over bills. State governors would be appointed by the national legislature, and the national legislature had veto power over any state legislation.

Hamilton presented his plan to the Convention on June 18, 1787. The plan was perceived as a well-thought-out plan, but it was not considered because it resembled the British system too closely.

Connecticut Compromise

To resolve this stalemate, Roger Sherman, a delegate from Connecticut, forged the Connecticut Compromise. In a sense it blended the Virginia (large-state) and New Jersey (small-state) proposals. Ultimately, its main contribution was determining the method for apportionment of the Senate and retaining a federal character in the constitution.

What was ultimately included in the Constitution was a modified form of this plan. In the Committee of Detail, Benjamin Franklin added the requirement that revenue bills originate in the House. As such, the Senate would bring a federal character to the government, not because senators were elected by state legislatures, but because each state was equally represented.

2.2.4: The Virginia and New Jersey Plans

In the Constitutional Convention, the Virginia Plan favored large states while the New Jersey Plan favored small states.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast the Virginia Plan, the New Jersey Plan, and the Connecticut Compromise regarding the revision of the Articles of Confederation.

Key Points

- The Virginia delegation took the initiative to frame the debate by immediately drawing up and presenting a proposal, for which delegate James Madison was given chief credit.

- The Virginia Plan proposed a bicameral legislature, a legislative branch with two chambers. This legislature would contain the dual principles of rotation in office and recall, applied to the lower house of the national legislature.

- According to the Virginia Plan, states with a large population would have more representatives than smaller states. Large states supported this plan, while smaller states generally opposed it.

- Under the New Jersey Plan, the unicameral legislature with one vote per state was inherited from the Articles of Confederation. This position reflected the belief that the states were independent entities.

- Ultimately, the New Jersey Plan was rejected as a basis for a new constitution. The Virginia Plan was used, but some ideas from the New Jersey Plan were added.

- The Connecticut Compromise established a bicameral legislature with the U.S. House of Representatives apportioned by population as desired by the Virginia Plan and the Senate granted equal votes per state as desired by the New Jersey Plan.

Key Terms

- recall

-

a procedure by which voters can remove an elected official from office through a direct vote before his or her term has ended

- Connecticut Compromise

-

The Connecticut Compromise was an agreement that both large and small states reached during the Constitutional Convention of 1787. The compromise defined, in part, the legislative structure and representation that each state would have under the United States Constitution. It retained the bicameral legislature as proposed by James Madison, along with proportional representation in the lower house, but required the upper house to be weighted equally between the states.

- new jersey plan

-

Under the New Jersey Plan, the unicameral legislature with one vote per state was inherited from the Articles of Confederation. This position reflected the belief that the states were independent entities and as they entered the United States of America freely and individually, so they remained.

- virginia plan

-

Virginia Plan was a proposal by Virginia delegates for a bicameral legislative branch. Prior to the start of the Convention, the Virginian delegates met and, drawing largely from Madison’s suggestions, drafted a plan.

Introduction

The Constitutional Convention gathered in Philadelphia to revise the Articles of Confederation. The Virginia delegation took the initiative to frame the debate by immediately drawing up and presenting a proposal, for which delegate James Madison is given chief credit. It was, however, Edmund Randolph, the Virginia governor at the time, who officially put it before the convention on May 29, 1787 in the form of 15 resolutions.

The scope of the resolutions, going well beyond tinkering with the Articles of Confederation, succeeded in broadening the debate to encompass fundamental revisions to the structure and powers of the national government. The resolutions proposed, for example, a new form of national government having three branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. One contentious issue facing the convention was the manner in which large and small states would be represented in the legislature. The contention was whether there would be equal representation for each state regardless of its size and population, or proportionate to population giving larger states more votes than less-populous states.

Virginia Plan

The Virginia Plan proposed a bicameral legislature, a legislative branch with two chambers. This legislature would contain the dual principles of rotation in office and recall, applied to the lower house of the national legislature . Each of the states would be represented in proportion to their “quotas of contribution, or to the number of free inhabitants.” States with a large population would thus have more representatives than smaller states. Large states supported this plan, while smaller states generally opposed it.

Virginia Plan

Visual representation of the structure of James Madison’s Virginia Plan.

In addition to dealing with legislative representation, the Virginia Plan addressed other issues as well, with many provisions that did not make it into the Constitution that emerged. It called for a national government of three branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. The people would elect members for one of the two legislative chambers. Members of that chamber would then elect the second chamber from nominations submitted by state legislatures. The legislative branch would then choose the executive branch.

The terms of office were unspecified, but the executive and members of the popularly elected legislative chamber could not be elected for an undetermined time afterward. The legislative branch would have the power to negate state laws if they were deemed incompatible with the articles of union. The concept of checks and balances was embodied in a provision that a council composed of the executive and selected members of the judicial branch could veto legislative acts. An unspecified legislative majority could override their veto.

New Jersey Plan

New Jersey Plan

Visual representation of the structure of the New Jersey Plan.

After the Virginia Plan was introduced, New Jersey delegate William Paterson asked for an adjournment to contemplate the Plan. Paterson’s New Jersey Plan was ultimately a rebuttal to the Virginia Plan . The less populous states were adamantly opposed to giving most of the control of the national government to the more populous states, and so proposed an alternative plan that would have kept the one-vote-per-state representation under one legislative body from the Articles of Confederation.

William Paterson

Portrait of William Paterson (1745–1806) when he was a Supreme Court Justice (1793–1806). Paterson was also known as the primary author of the New Jersey Plan during the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.

Under the New Jersey Plan, the unicameral legislature with one vote per state was inherited from the Articles of Confederation. This position reflected the belief that the states were independent entities, and as they entered the United States of America freely and individually, so they remained. The plan proposed that the Articles of Confederation should be amended as follows:

- Congress would gain authority to raise funds using tariffs and other measures;

- Congress would elect a federal executive who cannot be re-elected and subject to recall by Congress;

- The Articles of Confederation and treaties would be proclaimed as the supreme law of the land.

Connecticut Compromise

Ultimately, the New Jersey Plan was rejected as a basis for a new constitution. The Virginia Plan was used, but some ideas from the New Jersey Plan were added.

2.2.5: Debate over the Presidency and the Judiciary

During the Constitutional Convention, the most contentious disputes revolved around the composition of the Presidency and the Judiciary.

Learning Objective

Discuss the key debates of the Constitutional Convention

Key Points

- While waiting for the convention to formally begin, James Madison sketched out his initial draft, which became known as the “Virginia Plan” and which reflected his views as a strong nationalist.

- At the convention, some sided with Madison that the legislature should choose judges, while others believed the president should choose judges. A compromise was eventually reached that the president should choose judges and the Senate confirm them.

- The convention agreed that the house would elect the president if no candidate had an Electoral College majority, but that each state delegation would vote as a block, rather than individually.

- The Committee on Detail shortened the president’s term from seven years to four years, freed the president to seek re-election after an initial term, and moved impeachment trials from the courts to the Senate. They also created the office of the vice president.

Key Terms

- electoral college

-

A body of electors empowered to elect someone to a particular office

- presidency

-

The bureaucratic organization and governmental initiatives devolving directly from the president.

- James Madison

-

James Madison was an American statesman and political theorist, the fourth President of the United States (1809–1817). He is hailed as the “Father of the Constitution” for being instrumental in the drafting of the United States Constitution and as the key champion and author of the United States Bill of Rights.

Debate Over the Presidency and Judiciary

During the Constitutional Convention, the most contentious disputes revolved around the composition and election of the Senate, how “proportional representation” was to be defined, whether to divide the executive power between three people or invest the power into a single president, how to elect the president, how long his term was to be and whether he could stand for reelection, what offenses should be impeachable, the nature of a fugitive slave clause, whether to allow the abolition of the slave trade, and whether judges should be chosen by the legislature or executive. Most of the convention was spent deciding these issues, while the powers of legislature, executive, and judiciary were not heavily disputed .

Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia

During the Constitutional Convention, some the most contentious disputes revolved around the composition of the Presidency and the Judiciary.

James Madison’s Influence