14.1: The American Legal System

14.1.1: Cases and the Law

In the US judicial system, cases are decided based on principles established in previous cases; a practice called common law.

Learning Objective

Explain the relationship between legal precedent and common law

Key Points

- Common law is created when a court decides on a case and sets precedent.

- The principle of common law involves precedent, which is a practice that uses previous court cases as a basis for making judgments in current cases.

- Justice Brandeis established stare decisis as the method of making case law into good law. The principle of stare decisis refers to the practice of letting past decisions stand, and abiding by those decisions in current matters.

Key Terms

- stare decisis

-

The principle of following judicial precedent.

- common law

-

A legal system that gives great precedential weight to common law on the principle that it is unfair to treat similar facts differently on different occasions.

- precedent

-

a decided case which is cited or used as an example to justify a judgment in a subsequent case

Establishing Common Law

When a decision in a court case is made and is called law, it typically is referred to as “good law. ” Thus, subsequent decisions must abide by that previous decision. This is called “common law,” and it is based on the principle that it is unfair to treat similar facts differently in subsequent occasions. Essentially, the body of common law is based on the principles of case precedent and stare decisis.

Case Precedent

In the United States legal system, a precedent or authority is a principle or rule established in a previous legal case that is either binding on or persuasive for a court or other tribunal when deciding subsequent cases with similar issues or facts. The general principle in common law legal systems is that similar cases should be decided so as to give similar and predictable outcomes, and the principle of precedent is the mechanism by which this goal is attained. Black’s Law Dictionary defines “precedent” as a “rule of law established for the first time by a court for a particular type of case and thereafter referred to in deciding similar cases. “

Stare Decisis

Stare decisis is a legal principle by which judges are obliged to respect the precedent established by prior decisions. The words originated from the phrasing of the principle in the Latin maxim Stare decisis et non quieta movere: “to stand by decisions and not disturb the undisturbed. ” In a legal context, this is understood to mean that courts should generally abide by precedent and not disturb settled matters.

In other words, stare decisis applies to the holding of a case, or, the exact wording of the case. As the United States Supreme Court has put it: “dicta may be followed if sufficiently persuasive but are not binding. “

In the United States Supreme Court, the principle of stare decisis is most flexible in constitutional cases:

Stare decisis is usually the wise policy, because in most matters it is more important that the applicable rule of law be settled than that it be settled right. … But in cases involving the Federal Constitution, where correction through legislative action is practically impossible, this Court has often overruled its earlier decisions. … This is strikingly true of cases under the due process clause.—Burnet v. Coronado Oil & Gas Co., 285 U.S. 393, 406–407, 410 (1932)

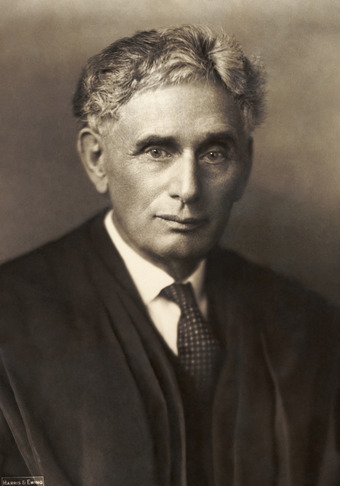

Louis Brandeis

Brandeis developed the idea of case law and the importance of stare decisis. His opinion in New Ice Co. set the stage for new federalism.

14.1.2: Types of Courts

The federal court system has three levels: district courts, courts of appeals, and the Supreme Court.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast the different types of courts that exist in the U.S. federal court system

Key Points

- District courts and administrative courts were created to hear lower level cases.

- The courts of appeals are required to hear all federal appeals.

- The Supreme Court is not required to hear appeals and is considered the final court of appeals.

- The Supreme Court may exercise original jurisdiction in cases affecting ambassadors and other diplomats, and in cases in which a state is a party.

Key Term

- appeal

-

(a) An application for the removal of a cause or suit from an inferior to a superior judge or court for re-examination or review. (b) The mode of proceeding by which such removal is effected. (c) The right of appeal. (d) An accusation; a process which formerly might be instituted by one private person against another for some heinous crime demanding punishment for the particular injury suffered, rather than for the offense against the public. (e) An accusation of a felon at common law by one of his accomplices, which accomplice was then called an approver.

The federal court system is divided into three levels: the first and lowest level is the United States district courts, the second, intermediate level is the court of appeals, and the Supreme Court is considered the highest court in the United States.

The United States district courts are the general federal trial courts, although in many cases Congress has passed statutes which divert original jurisdiction to these specialized courts or to administrative law judges (ALJs). In these cases, the district courts have jurisdiction to hear appeals from such lower bodies.

The United States courts of appeals are the federal intermediate appellate courts. They operate under a system of mandatory review which means they must hear all appeals of right from the lower courts. They can make a ruling of their own on the case, or choose to accept the decision of the lower court. In the latter case, many defendants appeal to the Supreme Court.

The highest court is the Supreme Court of the United States, which is considered the court of last resort . It generally is an appellate court that operates under discretionary review. This means that the Court, through granting of writs of certiorari, can choose which cases to hear. There is generally no right of appeal to the Supreme Court. In a few situations, like lawsuits between state governments or some cases between the federal government and a state, the Supreme Court becomes the court of original jurisdiction. In addition, the Constitution specifies that the Supreme Court may exercise original jurisdiction in cases affecting ambassadors and other diplomats, in cases in which a state is a party, and cases between the state and another country. In all other cases, however, the Court has only appellate jurisdiction. It considers cases based on its original jurisdiction very rarely; almost all cases are brought to the Supreme Court on appeal. In practice, the only original jurisdiction cases heard by the Court are disputes between two or more states. Such cases are generally referred to a designated individual, usually a sitting or retired judge, or a well-respected attorney, to sit as a special master and report to the Court with recommendations.

Supreme Court of the United States

The modern supreme court.

14.1.3: Federal Jurisdiction

The federal court system has limited, though important, jurisdiction.

Learning Objective

Discuss the different levels of jurisdiction by state and federal courts in the American legal system

Key Points

- In the justice system, state courts hear state law, and federal courts hear federal law and sometimes appeals.

- Federal courts only have the power granted to them by federal law and the Constitution.

- Courts render their decisions through opinions; the majority will write an opinion and the minority will write a dissent.

Key Terms

- federal system

-

a system of government based upon democratic rule in which sovereignty and the power to rule is constitutionally divided between a central governing authority and constituent political units (such as states or provinces)

- jurisdiction

-

the power, right, or authority to interpret and apply the law

Federal Jurisdiction

The American legal system includes both state courts and federal courts. Generally, state courts hear cases involving state law, although they may also hear cases involving federal law so long as the federal law in question does not grant exclusive jurisdiction to federal courts. Federal courts may only hear cases where federal jurisdiction can be established. Specifically, the court must have both subject-matter jurisdiction over the matter of the claim and personal jurisdiction over the parties . The Federal Courts are courts of limited jurisdiction, meaning that they can only exercise the powers that are granted to them by the Constitution and federal laws. For subject matter jurisdiction, the claims in the case must either: raise a federal question, such as a cause of action or defense arising under the Constitution; a federal statute, or the law of admiralty; or have diversity of parties. For example, all of the defendants are from a different state than the plaintiff, and have an amount in controversy that exceeds a monetary threshold (which changes from time to time, but is $75,000 as of 2011).

Federal district courts

The federal district courts represent one of the ways federal jurisdiction is split.

If a Federal Court has subject matter jurisdiction over one or more of the claims in a case, it has discretion to exercise ancillary jurisdiction over other state law claims.

The Supreme Court has “cautioned that … Court[s] must take great care to ‘resist the temptation’ to express preferences about [certain types of cases] in the form of jurisdictional rules. Judges must strain to remove the influence of the merits from their jurisdictional rules. The law of jurisdiction must remain apart from the world upon which it operates.”

Generally, when a case has successfully overcome the hurdles of standing, Case or Controversy, and State Action, it will be heard by a trial court. The non-governmental party may raise claims or defenses relating to alleged constitutional violation(s) by the government. If the non-governmental party loses, the constitutional issue may form part of the appeal. Eventually, a petition for certiorari may be sent to the Supreme Court. If the Supreme Court grants certiorari and accepts the case, it will receive written briefs from each side (and any amicae curi or friends of the court—usually interested third parties with some expertise to bear on the subject) and schedule oral arguments. The Justices will closely question both parties. When the Court renders its decision, it will generally do so in a single majority opinion and one or more dissenting opinions. Each opinion sets forth the facts, prior decisions, and legal reasoning behind the position taken. The majority opinion constitutes binding precedent on all lower courts; when faced with very similar facts, they are bound to apply the same reasoning or face reversal of their decision by a higher court.

14.2: Origins of American Law

14.2.1: Common Law

Law of the United States was mainly derived from the common law system of English law.

Learning Objective

Identify the principles and institutions that comprise the common law tradition

Key Points

- The United States and most Commonwealth countries are heirs to the common law legal tradition of English law. Certain practices traditionally allowed under English common law were specificilly outlawed by the Constitution, such as bills of attainder and general search warrants.

- All U.S. states except Louisiana have enacted “reception statutes” which generally state that the common law of England (particularly judge-made law) is the law of the state to the extent that it is not repugnant to domestic law or indigenous conditions.

- Unlike the states, there is no plenary reception statute at the federal level that continued the common law and thereby granted federal courts the power to formulate legal precedent like their English predecessors.

- The passage of time has led to state courts and legislatures expanding, overruling, or modifying the common law. As a result, the laws of any given state invariably differ from the laws of its sister states.

Key Terms

- stare decisis

-

The principle of following judicial precedent.

- heir

-

Someone who inherits, or is designated to inherit, the property of another.

Background

At both the federal and state levels, the law of the United States was mainly derived from the common law system of English law , which was in force at the time of the Revolutionary War. However, U.S. law has diverged greatly from its English ancestor both in terms of substance and procedure. It has incorporated a number of civil law innovations.

Royal Courts of Justice

The neo-medieval pile of the Royal Courts of Justice on G.E. Street, The Strand, London.

American Common Law

The United States and most Commonwealth countries are heirs to the common law legal tradition of English law. Certain practices traditionally allowed under English common law were specifically outlawed by the Constitution, such as bills of attainder and general search warrants.

As common law courts, U.S. courts have inherited the principle of stare decisis. American judges, like common law judges elsewhere, not only apply the law, they also make the law. Their decisions in the cases before them became the precedent for decisions in future cases.

The actual substance of English law was formally received into the United States in several ways. First, all U.S. states except Louisiana have enacted “reception statutes” which generally state that the common law of England (particularly judge-made law) is the law of the state to the extent that it is not repugnant to domestic law or indigenous conditions. Some reception statutes impose a specific cutoff date for reception, such as the date of a colony’s founding, while others are deliberately vague. Therefore, contemporary U.S. courts often cite pre-Revolution cases when discussing the evolution of an ancient judge-made common law principle into its modern form. An example is the heightened duty of care that was traditionally imposed upon common carriers.

Federal courts lack the plenary power possessed by state courts to simply make up law. State courts are able to do this in the absence of constitutional or statutory provisions replacing the common law. Only in a few limited areas, like maritime law, has the Constitution expressly authorized the continuation of English common law at the federal level (meaning that in those areas federal courts can continue to make law as they see fit, subject to the limitations of stare decisis).

Federal Precedent

Unlike the states, there is no plenary reception statute at the federal level that continued the common law and thereby granted federal courts the power to formulate legal precedent like their English predecessors. Federal courts are solely creatures of the federal Constitution and the federal Judiciary Acts. However, it is universally accepted that the Founding Fathers of the United States, by vesting judicial power into the Supreme Court and the inferior federal courts in Article Three of the United States Constitution, vested in them the implied judicial power of common law courts to formulate persuasive precedent. This power was widely accepted, understood, and recognized by the Founding Fathers at the time the Constitution was ratified. Several legal scholars have argued that the federal judicial power to decide “cases or controversies” necessarily includes the power to decide the precedential effect of those cases and controversies.

State Law

The passage of time has led to state courts and legislatures expanding, overruling, or modifying the common law. As a result, the laws of any given state invariably differ from the laws of its sister states. Therefore, with regard to the vast majority of areas of the law that are traditionally managed by the states, the United States cannot be classified as having one legal system. Instead, it must be regarded as 50 separate systems of tort law, family law, property law, contract law, criminal law, and so on. Naturally, the laws of different states frequently come into conflict with each other. In response, a very large body of law was developed to regulate the conflict of laws in the United States.

All states have a legislative branch which enacts state statutes, an executive branch that promulgates state regulations pursuant to statutory authorization, and a judicial branch that applies, interprets, and occasionally overturns state statutes, regulations, and local ordinances.

In some states, codification is often treated as a mere restatement of the common law. This occurs to the extent that the subject matter of the particular statute at issue was covered by some judge-made principle at common law. Judges are free to liberally interpret the codes unless and until their interpretations are specifically overridden by the legislature. In other states, there is a tradition of strict adherence to the plain text of the codes.

14.2.2: Primary Sources of American Law

The primary sources of American Law are: constitutional law, statutory law, treaties, administrative regulations, and the common law.

Learning Objective

Identify the sources of American federal and state law

Key Points

- Where Congress enacts a statute that conflicts with the Constitution, the Supreme Court may find that law unconstitutional and declare it invalid. A statute does not disappear automatically merely because it has been found unconstitutional; a subsequent statute must delete it.

- The United States and most Commonwealth countries are heirs to the common law legal tradition of English law. Certain practices traditionally allowed under English common law were expressly outlawed by the Constitution, such as bills of attainder and general search warrants.

- Early American courts, even after the Revolution, often did cite contemporary English cases. This was because appellate decisions from many American courts were not regularly reported until the mid-19th century; lawyers and judges used English legal materials to fill the gap.

- Foreign law has never been cited as binding precedent, but merely as a reflection of the shared values of Anglo-American civilization or even Western civilization in general.

- Most U.S. law consists primarily of state law, which can and does vary greatly from one state to the next.

Key Term

- commonwealth

-

A form of government, named for the concept that everything that is not owned by specific individuals or groups is owned collectively by everyone in the governmental unit, as opposed to a state, where the state itself owns such things.

Background

In the United States, the law is derived from various sources. These sources are constitutional law, statutory law, treaties, administrative regulations, and the common law. At both the federal and state levels, the law of the United States was originally largely derived from the common law system of English law, which was in force at the time of the Revolutionary War. However, U.S. law has diverged greatly from its English ancestor both in terms of substance and procedure, and has incorporated a number of civil law innovations. Thus, most U.S. law consists primarily of state law, which can and does vary greatly from one state to the next.

Constitutionality

Where Congress enacts a statute that conflicts with the Constitution , the Supreme Court may find that law unconstitutional and declare it invalid. A statute does not disappear automatically merely because it has been found unconstitutional; a subsequent statute must delete it. Many federal and state statutes have remained on the books for decades after they were ruled to be unconstitutional. However, under the principle of stare decisis, no sensible lower court will enforce an unconstitutional statute, and the Supreme Court will reverse any court that does so. Conversely, any court that refuses to enforce a constitutional statute (where such constitutionality has been expressly established in prior cases) will risk reversal by the Supreme Court.

American Common Law

As common law courts, U.S. courts have inherited the principle of stare decisis. American judges, like common law judges elsewhere, not only apply the law, they also make the law, to the extent that their decisions in the cases before them become precedent for decisions in future cases.

The actual substance of English law was formally “received” into the United States in several ways. First, all U.S. states except Louisiana have enacted “reception statutes” which generally state that the common law of England (particularly judge-made law) is the law of the state to the extent that it is not repugnant to domestic law or indigenous conditions. Some reception statutes impose a specific cutoff date for reception, such as the date of a colony’s founding, while others are deliberately vague. Thus, contemporary U.S. courts often cite pre-Revolution cases when discussing the evolution of an ancient judge-made common law principle into its modern form, such as the heightened duty of care traditionally imposed upon common carriers.

Second, a small number of important British statutes in effect at the time of the Revolution have been independently reenacted by U.S. states. Two examples that many lawyers will recognize are the Statute of Frauds (still widely known in the U.S. by that name) and the Statute of 13 Elizabeth (the ancestor of the Uniform Fraudulent Transfers Act). Such English statutes are still regularly cited in contemporary American cases interpreting their modern American descendants.

However, it is important to understand that despite the presence of reception statutes, much of contemporary American common law has diverged significantly from English common law. The reason is that although the courts of the various Commonwealth nations are often influenced by each other’s rulings, American courts rarely follow post-Revolution Commonwealth rulings unless there is no American ruling on point, the facts and law at issue are nearly identical, and the reasoning is strongly persuasive.

Early on, American courts, even after the Revolution, often did cite contemporary English cases. This was because appellate decisions from many American courts were not regularly reported until the mid-19th century; lawyers and judges, as creatures of habit, used English legal materials to fill the gap. But citations to English decisions gradually disappeared during the 19th century as American courts developed their own principles to resolve the legal problems of the American people. The number of published volumes of American reports soared from eighteen in 1810 to over 8,000 by 1910. By 1879, one of the delegates to the California constitutional convention was already complaining: “Now, when we require them to state the reasons for a decision, we do not mean they shall write a hundred pages of detail. We [do] not mean that they shall include the small cases, and impose on the country all this fine judicial literature, for the Lord knows we have got enough of that already. “

Today, in the words of Stanford law professor Lawrence Friedman: American cases rarely cite foreign materials. Courts occasionally cite a British classic or two, a famous old case, or a nod to Blackstone; but current British law almost never gets any mention. Foreign law has never been cited as binding precedent, but merely as a reflection of the shared values of Anglo-American civilization or even Western civilization in general.

14.2.3: Civil Law and Criminal Law

Criminal law is the body of law that relates to crime and civil law deals with disputes between organizations and individuals.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast civil law with common law

Key Points

- The objectives of civil law are different from other types of law. In civil law there is the attempt to right a wrong, honor an agreement, or settle a dispute.

- Criminal law is the body of law that relates to crime. It is the body of rules that defines conduct that is not allowed because it is held to threaten, harm or endanger the safety and welfare of people.

- In civil law there is the attempt to right a wrong, honor an agreement, or settle a dispute. If there is a victim, they get compensation, and the person who is the cause of the wrong pays, this being a civilized form of, or legal alternative to, revenge.

- For public welfare offenses where the state is punishing merely risky (as opposed to injurious) behavior, there is significant diversity across the various states.

Key Terms

- equity

-

A legal tradition that deals with remedies other than monetary relief, such as injunctions, divorces and similar actions.

- criminal law

-

the area of law that regulates social conduct, prohibits threatening, harming, or otherwise endangering the health, safety, and moral welfare of people, and punishes people who violate these laws

- incarceration

-

The act of confining, or the state of being confined; imprisonment.

Background

Criminal law is the body of law that relates to crime. It is the body of rules that defines conduct that is not allowed because it is held to threaten, harm or endanger the safety and welfare of people. Criminal law also sets out the punishment to be imposed on people who do not obey these laws. Criminal law differs from civil law, whose emphasis is more on dispute resolution than in punishment.

Civil law is the branch of law dealing with disputes between individuals or organizations, in which compensation may be awarded to the victim. For instance, if a car crash victim claims damages against the driver for loss or injury sustained in an accident, this will be a civil law case. Civil law differs from criminal law, which emphasizes punishment rather than dispute resolution. The law relating to civil wrongs and quasi-contract is part of civil law.

Civil Law Versus Criminal Law

The objectives of civil law are different from other types of law. In civil law there is the attempt to right a wrong, honor an agreement, or settle a dispute. If there is a victim, they get compensation, and the person who is the cause of the wrong pays, this being a civilized form of, or legal alternative to, revenge. If it is a matter of equity, there often exists a pie for division and a process of civil law which allocates it. In public law the objective is usually deterrence and retribution.

An action in criminal law does not necessarily preclude an action in civil law in common law countries, and may provide a mechanism for compensation to the victims of crime. Such a situation occurred when O.J. Simpson was ordered to pay damages for wrongful death after being acquitted of the criminal charge of murder.

Criminal law involves the prosecution by the state of wrongful acts, which are considered to be so serious that they are a breach of the sovereign’s peace (and cannot be deterred or remedied by mere lawsuits between private parties). Generally, crimes can result in incarceration, but torts (see below) cannot. The majority of the crimes committed in the United States are prosecuted and punished at the state level. Federal criminal law focuses on areas specifically relevant to the federal government like evading payment of federal income tax, mail theft, or physical attacks on federal officials, as well as interstate crimes like drug trafficking and wire fraud.

All states have somewhat similar laws in regard to “higher crimes” (or felonies), such as murder and rape, although penalties for these crimes may vary from state to state. Capital punishment is permitted in some states but not others. Three strikes laws in certain states impose harsh penalties on repeat offenders.

Some states distinguish between two levels: felonies and misdemeanors (minor crimes). Generally, most felony convictions result in lengthy prison sentences as well as subsequent probation, large fines, and orders to pay restitution directly to victims; while misdemeanors may lead to a year or less in jail and a substantial fine. To simplify the prosecution of traffic violations and other relatively minor crimes, some states have added a third level, infractions. These may result in fines and sometimes the loss of one’s driver’s license, but no jail time.

For public welfare offenses where the state is punishing merely risky (as opposed to injurious) behavior, there is significant diversity across the various states. For example, punishments for drunk driving varied greatly prior to 1990. State laws dealing with drug crimes still vary widely, with some states treating possession of small amounts of drugs as a misdemeanor offense or as a medical issue and others categorizing the same offense as a serious felony.

The law of most of the states is based on the common law of England; the notable exception is Louisiana. Much of Louisiana law is derived from French and Spanish civil law, which stems from its history as a colony of both France and Spain. Puerto Rico, a former Spanish colony, is also a civil law jurisdiction of the United States. However, the criminal law of both jurisdictions has been necessarily modified by common law influences and the supremacy of the federal Constitution. Many states in the southwest that were originally Mexican territory have inherited several unique features from the civil law that governed when they were part of Mexico. These states include Arizona, California , Nevada, New Mexico, and Texas.

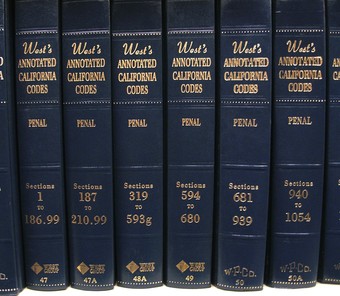

California Penal Code

The California Penal Code, the codification of criminal law and procedure in the U.S. state of California.

14.2.4: Basic Judicial Requirements

In the judiciary system each position within the federal, state and local government has different types of requirements.

Learning Objective

Identify the type and structure of courts that make up the U.S. federal court system

Key Points

- In federal legislation, regulations governing the “courts of the United States” only refer to the courts of the United States government, and not the courts of the individual states.

- State courts may have different names and organization; trial courts may be called courts of common plea and appellate courts “superior courts” or commonwealth courts.

- The U.S. federal court system hears cases involving litigants from two or more states, violations of federal laws, treaties, and the Constitution, admiralty, bankruptcy, and related issues. In practice, about 80% of the cases are civil and 20% are criminal.

- Federal courts may not decide every case that happens to come before them. In order for a district court to entertain a lawsuit, Congress must first grant the court subject matter jurisdiction over the type of dispute in question.

- In addition to their original jurisdiction, the district courts have appellate jurisdiction over a very limited class of judgments, orders, and decrees.

- A final ruling by a district court in either a civil or a criminal case can be appealed to the United States court of appeals in the federal judicial circuit in which the district court is located, except that some district court rulings involving patents and certain other specialized matters.

Key Terms

- appeal

-

(a) An application for the removal of a cause or suit from an inferior to a superior judge or court for re-examination or review. (b) The mode of proceeding by which such removal is effected. (c) The right of appeal. (d) An accusation; a process which formerly might be instituted by one private person against another for some heinous crime demanding punishment for the particular injury suffered, rather than for the offense against the public. (e) An accusation of a felon at common law by one of his accomplices, which accomplice was then called an approver.

- original jurisdiction

-

the power of a court to hear a case for the first time

Background

In federal legislation, regulations governing the “courts of the United States” only refer to the courts of the United States government, and not the courts of the individual states. Because of the federalist underpinnings of the division between federal and state governments, the various state court systems are free to operate in ways that vary widely from those of the federal government, and from one another. In practice, however, every state has adopted a division of its judiciary into at least two levels, and almost every state has three levels, with trial courts hearing cases which may be reviewed by appellate courts, and finally by a state supreme court. A few states have two separate supreme courts, with one having authority over civil matters and the other reviewing criminal cases. State courts may have different names and organization; trial courts may be called “courts of common plea” and appellate courts “superior courts” or “commonwealth courts. ” State courts hear about 98% of litigation; most states have special jurisdiction courts, which typically handle minor disputes such as traffic citations, and general jurisdiction courts, which handle more serious disputes.

The U.S. federal court system hears cases involving litigants from two or more states, violations of federal laws, treaties, and the Constitution, admiralty, bankruptcy, and related issues. In practice, about 80% of the cases are civil and 20% are criminal. The civil cases often involve civil rights, patents, and Social Security while the criminal cases involve tax fraud, robbery, counterfeiting, and drug crimes. The trial courts are U.S. district courts, followed by United States courts of appeals and then the Supreme Court of the United States. The judicial system, whether state or federal, begins with a court of first instance, whose work may be reviewed by an appellate court, and then ends at the court of last resort, which may review the work of the lower courts.

Jurisdiction

Unlike some state courts, the power of federal courts to hear cases and controversies is strictly limited. Federal courts may not decide every case that happens to come before them. In order for a district court to entertain a lawsuit, Congress must first grant the court subject matter jurisdiction over the type of dispute in question. Though Congress may theoretically extend the federal courts’ subject matter jurisdiction to the outer limits described in Article III of the Constitution, it has always chosen to give the courts a somewhat narrower power.

For most of these cases, the jurisdiction of the federal district courts is concurrent with that of the state courts. In other words, a plaintiff can choose to bring these cases in either a federal district court or a state court. Congress has established a procedure whereby a party, typically the defendant, can remove a case from state court to federal court, provided that the federal court also has original jurisdiction over the matter. Patent and copyright infringement disputes and prosecutions for federal crimes, the jurisdiction of the district courts is exclusive of that of the state courts.

US Court of Appeals and District Court Map

Courts of Appeals, with the exception of one, are divided into geographic regions known as circuits that hear appeals from district courts within the region..

Attorneys

In order to represent a party in a case in a district court, a person must be an Attorney At Law and generally must be admitted to the bar of that particular court. The United States usually does not have a separate bar examination for federal practice (except with respect to patent practice before the United States Patent and Trademark Office). Admission to the bar of a district court is generally granted as a matter of course to any attorney who is admitted to practice law in the state where the district court sits. Many district courts also allow an attorney who has been admitted and remains an active member in good standing of any state, territory or the District of Columbia bar to become a member. The attorney submits his application with a fee and takes the oath of admission. Local practice varies as to whether the oath is given in writing or in open court before a judge of the district.

Several district courts require attorneys seeking admission to their bars to take an additional bar examination on federal law, including the following: the Southern District of Ohio, the Northern District of Florida, and the District of Puerto Rico.

Appeals

Generally, a final ruling by a district court in either a civil or a criminal case can be appealed to the United States court of appeals in the federal judicial circuit in which the district court is located, except that some district court rulings involving patents and certain other specialized matters must be appealed instead to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, and in a very few cases the appeal may be taken directly to the United States Supreme Court.

14.3: The Federal Court System

14.3.1: U.S. District Courts

The 94 U.S. district courts oversee civil and criminal cases within certain geographic or subject areas.

Learning Objective

Identify the function and characteristics of U.S. district courts

Key Points

- The U.S. district courts are the trial courts within the U.S. federal system that primarily address civil and criminal cases.

- Each state and territory has at least one district court responsible for hearing cases that arise within a given geographic area.

- Civil cases are legal disputes between two or more parties while criminal cases involve prosecution by a U.S. attorney. Civil and criminal cases also differ in how they are conducted.

- Every district court is associated with a bankruptcy court that usually provides relief for honest debtors and ensures that creditors are paid back in a timely manner.

- Two special trial courts lie outside of the district court system: the Court of International Trade and the United States Court of Federal Claims.

Key Terms

- prosecutor

-

A lawyer who decides whether to charge a person with a crime and tries to prove in court that the person is guilty.

- plaintiff

-

A party bringing a suit in civil law against a defendant; accusers.

- defendant

-

In civil proceedings, the party responding to the complaint; one who is sued and called upon to make satisfaction for a wrong complained of by another.

Introduction

The United States district courts are the trial courts within the U.S. federal court system. There are a total of ninety-four district courts throughout the U.S. states and territories . Every state and territory has at least one district court that is responsible for hearing cases that arise within that geographic area. With the exception of the territorial courts in Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the Virgin Islands, federal district judges are appointed for life.

District Court of Rhode Island Seal

Each state has at least one district court that is responsible for overseeing civil and criminal cases in a given region.

Criminal and Civil Cases

The U.S. district courts are responsible for holding general trials for civil and criminal cases. Civil cases are legal disputes between two or more parties; they officially begin when a plaintiff files a complaint with the court. The complaint explains the plaintiff’s injury, how the defendant caused the injury, and requests the court’s assistance in addressing the injury. A copy of the complaint is “served” to the defendant who must, subsequently, appear for a trial. Plaintiffs may ask the court to order the defendant to stop the conduct that is causing the injury or may seek monetary compensation for the injury.

Meanwhile, criminal cases involve a U.S. attorney (the prosecutor), a grand jury, and a defendant. Defendants may also have their own private attorney to represent them or a court-appointed attorney if they are unable to afford counsel. The purpose of the grand jury is to review evidence presented by the prosecutor to decide whether a defendant should stand trial. Criminal cases involve an arraignment hearing in which defendants enter a plea to the charges brought against them by the U.S. attorney. Most defendants will plead guilty at this point instead of going to trial. A judge may issue a sentence at this time or will schedule a hearing at a later point to determine the sentence. Those defendants who plead not guilty will be scheduled to receive a later trial.

Bankruptcy Court

A bankruptcy court is associated with each U.S. district court. Bankruptcy cases primarily address two concerns. First, they may provide an honest debtor with a “fresh start” by relieving the debtor of most debts. Second, bankruptcy cases ensure that creditors are repaid in a timely manner commensurate with what property the debtor has available for payment.

Other Trial Courts

While district courts are the primary trial courts within the U.S., two special trial courts exist outside of the district court system. The Court of International Trade has jurisdiction over cases involving international trade and customs issues. Meanwhile, the United States Court of Federal Claims oversees claims against the United States. These claims include money damages against the U.S., unlawful takings of private property by the federal government, and disputes over federal contracts. Both courts exercise nationwide jurisdiction versus the geographic jurisdiction limited to the district courts.

14.3.2: U.S. Court of Appeals

The U.S. courts of appeals review the decisions made in trial courts and often serve as the final arbiter in federal cases.

Learning Objective

Discuss the role of the U.S. federal courts of appeals in the judiciary

Key Points

- The U.S. federal courts of appeals hear appeals from district courts as well as appeals from decisions of federal administrative agencies.

- Courts of appeals are divided into thirteen circuits, twelve of which serve specific geographic regions.The thirteenth circuit hears appeals from the Court of International Trade, the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, the Patent and Trademark Office, and others.

- In contrast to trial courts, appellate court decisions are made by a panel of three judges who do not consider any additional evidence beyond what was presented in trial court or any additional witness testimony.

- A litigant who files an appeal, known as an appellant, and a litigant defending against an appeal, known as an appellee, present their legal arguments in documents called briefs. Oral arguments may also be made to argue for or against an appeal.

- The U.S. courts of appeals are among the most powerful courts since they establish legal precedent and serve as the final arbiter in more cases than the Supreme Court.

Key Terms

- trial court

-

a tribunal established for the administration of justice, in which disputing parties come together to present information before a jury or judge that will decide the outcome of the case

- ruling

-

An order or a decision on a point of law from someone in authority.

- appeal

-

(a) An application for the removal of a cause or suit from an inferior to a superior judge or court for re-examination or review. (b) The mode of proceeding by which such removal is effected. (c) The right of appeal. (d) An accusation; a process which formerly might be instituted by one private person against another for some heinous crime demanding punishment for the particular injury suffered, rather than for the offense against the public. (e) An accusation of a felon at common law by one of his accomplices, which accomplice was then called an approver.

- litigant

-

A party suing or being sued in a lawsuit, or otherwise calling upon the judicial process to determine the outcome of a suit.

- brief

-

memorandum of points of fact or of law for use in conducting a case

The U.S. federal courts of appeals, also known as appellate courts or circuit courts, hear appeals from district courts as well as appeals from decisions of federal administrative agencies. There are thirteen courts of appeals, twelve of which are based on geographic districts called circuits. These twelve circuit courts decide whether or not the district courts within their geographic jurisdiction have made an error in conducting a trial . The thirteenth court of appeals hears appeals from the Court of International Trade, the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, the Patent and Trademark Office, and others.

US Court of Appeals and District Court Map

Courts of Appeals, with the exception of one, are divided into geographic regions known as circuits that hear appeals from district courts within the region..

Every federal court litigant has the right to appeal an unfavorable ruling from the district court by requesting a hearing in a circuit court. However, only about 17% of eligible litigants do so because of the expense of appealing. In addition, few appealed cases are heard in the higher courts. Those that are, are rarely reversed.

Procedure

The procedure within appellate courts diverges widely from that within district courts. First, a litigant who files an appeal, known as an appellant, must show that the trial court or an administrative agency made a legal error that affected the decision in the case. Appeals are then passed to a panel of three judges working together to make a decision. These judges base their decision on the record of the case established by the trial court or agency. The appellant presents a document called a brief, which lays out the legal arguments to persuade the judge that the trial court made an error. Meanwhile, the party defending against the appeal, known as the apellee, also presents a brief presenting reasons the trial court decision is correct or why an error made by the trial court is not significant enough to reverse the decision. The appellate judges do not receive any additional evidence or hear witnesses.

While some cases are decided on the basis of written briefs alone, other cases move on to an oral argument stage. Oral argument consists of a structured discussion between the appellate lawyers and the panel of judges on the legal principles in dispute. Each side is given a short time to present their arguments to the judges. The court of appeals decision is usually the final word in the case unless it sends the case back to the trial court for additional proceedings. A litigant who loses in the federal courts of appeals may also ask the Supreme Court to review the case.

Legal Precedent

The U.S. courts of appeals are among the most powerful and influential courts in the United States. Decisions made within courts of appeals, unlike those of the lower district courts, establish binding precedents. After a ruling has been made, other federal courts in the circuit must follow the appellate court’s guidance in similar cases, even if the trial judge thinks that the case should be handled differently. In addition, the courts of appeals often serve as the final arbiter in federal cases, since the Supreme Court hears less than 100 of the over 10,000 cases sent to it annually.

14.3.3: The Supreme Court

The U.S. Supreme Court is the highest tribunal within the U.S. and most often hears cases concerning the Constitution or federal law.

Learning Objective

Explain the composition and significance of the Supreme Court, as well as its methodology to decide which cases to hear.

Key Points

- The Supreme Court is currently composed of a Chief Justice and eight associate justices nominated the President and confirmed by the U.S. Senate.

- The justices are appointed for life and do not officially represent any political party although they are often informally categorized as being conservative, moderate, or liberal on their judicial outlook.

- Article III and the Eleventh Amendment of the Constitution establish the Supreme Court as the first court to hear certain kinds of cases.

- Most cases that reach the Supreme Court are appeals from lower courts that begin as a writ of certiorari.

- Some reasons cases are granted cert are that they present a conflict in the interpretation of federal law or the Constitution, they represent an extreme departure from the normal course of judicial proceedings, or if a decision conflicts with a previous decision of the Supreme Court.

- Cases are decided by majority rule in which at least five of the nine justices have to agree.

Key Terms

- appeal

-

(a) An application for the removal of a cause or suit from an inferior to a superior judge or court for re-examination or review. (b) The mode of proceeding by which such removal is effected. (c) The right of appeal. (d) An accusation; a process which formerly might be instituted by one private person against another for some heinous crime demanding punishment for the particular injury suffered, rather than for the offense against the public. (e) An accusation of a felon at common law by one of his accomplices, which accomplice was then called an approver.

- tribunal

-

An assembly including one or more judges to conduct judicial business; a court of law.

- amicus curiae

-

someone who is not a party to a case who offers information that bears on the case but that has not been solicited by any of the parties to assist a court

Definition and Composition

The U.S. Supreme Court is the highest tribunal within the U.S. and hears a limited number of cases per year associated with the Constitution or laws of the United States. It is currently composed of the Chief Justice of the United States and eight associate justices. The current Chief Justice is John Roberts; the eight associate justices are Anthony Kennedy, Clarence Thomas, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Samuel Alito, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan. Justice Antonin Scalia died on Feb. 13, 2016. President Obama nominated Merrick Garland as his replacement on March 16, 2016, but the U.S. Senate did not initiate the process for Garland’s approval. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell stated that the Senate would not approve a Scalia replacement until after a new president took office in January, 2017.

The U.S. Supreme Court

The United States Supreme Court, the highest court in the United States, in 2010. Top row (left to right): Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Stephen G. Breyer, Associate Justice Samuel A. Alito, and Associate Justice Elena Kagan. Bottom row (left to right): Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Associate Justice Antonin Scalia, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy, and Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

The Justices

The Supreme Court justices are nominated by the President and confirmed by the U.S. Senate. Justices have life tenure unless they resign, retire, or are removed after impeachment. Although the justices do not represent or receive official endorsements from political parties, they are usually informally labeled as judicial conservatives, moderates, or liberals in their legal outlook.

Article III of the United States Constitution leaves it to Congress to fix the number of justices. Initially, The Judiciary Act of 1789 called for the appointment of six justices. But in 1866, at the behest of Chief Justice Chase, Congress passed an act providing that the next three justices to retire would not be replaced, which would thin the bench to seven justices by attrition. Consequently, one seat was removed in 1866 and a second in 1867. In 1869, however, the Circuit Judges Act returned the number of justices to nine, where it has since remained.

How Cases Reach the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court is the first court to hear certain kinds of cases in accordance with both Article III and the Eleventh Amendment of the Constitution. These cases include those between the United States and one of the states, those between two or more states, those brought by one state against citizens of another state or foreign country, and those involving foreign ambassadors or other ministers. However, only about 1% of the Supreme Court’s cases consist of these cases. Most cases reach the Supreme Court as appeals from civil and criminal cases that have been decided by state and lower federal courts.

Cases that come to the Supreme Court as appeals begin as a writ of certiorari, which is a petition to the Supreme Court to review the case. The Supreme Court will review the case if four of the nine justices agree to “grant cert. ” This standard for acceptance is known as the Rule of Four. Cases that are granted cert must be chosen for “compelling reasons,” as outlined in the court’s Rule 10. These reasons could be that the cases present a conflict in the interpretation of federal law or the Constitution, that they raise an important question about federal law, or that they represent an extreme departure from the normal course of judicial proceedings. The Supreme Court can also grant cert if the decision made in a lower court conflicts with a previous decision of the Supreme Court. If the Supreme Court does not grant cert this simply means that it has decided not to review the case.

To manage the high volume of cert petitions received by the Court each year, the Court employs an internal case management tool known as the “cert pool. ” Each year, the Supreme Court receives thousands of petitions for certiorari; in 2001 the number stood at approximately 7,500, and had risen to 8,241 by October Term 2007. The Court will ultimately grant approximately 80 to 100 of these petitions, in accordance with the rule of four.

Procedure

Once a case is granted cert, lawyers on each side file a brief that presents their arguments. With the permission of the court, others with a stake in the outcome of the case may also file an amicus curiae brief for one of the parties to the case. After the briefs are reviewed, the justices hear oral arguments from both parties. During the oral argument the justices may ask questions, raise new issues, or probe arguments made in the briefs.

The justices meet in a conference some time after oral arguments to vote on a case decision. The justices vote in order of seniority, beginning with the Chief Justice. Cases are decided by majority rule in which at least five of the nine justices have to agree. Bargaining and compromise are often called for to create a majority coalition. Once a decision has been made, one of the justices will write the majority opinion of the Court. This justice is chosen by either the Chief Justice or by the justice in the majority who has served the longest in the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court cannot directly enforce its rulings. Instead, it relies on respect for the Constitution and the law for adherence to its decisions.

14.4: Judicial Review and Policy Making

14.4.1: The Impact of Court Decisions

Court decisions can have a very strong influence on current and future laws, policies, and practices.

Learning Objective

Identify the impacts of court decisions on current policies and practices.

Key Points

- Court decisions can have an important impact on policy, law, and legislative or executive action; different courts can also have an influence on each other.

- In the U.S. legal systems, a precedent is a principle or rule established in a previous legal court decision that is either binding on, or persuasive for, a court or other tribunal when deciding subsequent cases with similar issues or facts.

- Common law precedent is a third kind of law, on equal footing with statutory law (statutes and codes enacted by legislative bodies), and regulatory law (regulations promulgated by executive branch agencies).

- Stare decisis is a legal principle by which judges are obliged to respect the precedent established by prior court decisions.

- Vertical precedent is the application of the doctrine of stare decisis from a superior court to an inferior court; horizontal precedent, on the other hand, is the application of the doctrine across courts of similar or coordinate level.

Key Term

- privatization

-

the government outsourcing of services or functions to private firms

Privatization is government outsourcing of services or functions to private firms. These services often include, revenue collection, law enforcement and prison management.

In competitive industries with well-informed consumers, privatization consistently improves efficiency. The more competitive the industry, the greater the improvement in output, profitability and efficiency. Such efficiency gains mean a one-off increase in GDP, but improved incentives to innovate and reduce costs also tend to raise the rate of economic growth. Although typically there are many costs associated with these efficiency gains, many economists argue that these can be dealt with by appropriate government support through redistribution and perhaps retraining.

Capitol Hill

Capitol Hill, where bills become laws.

Studies show that private market factors can more efficiently deliver many goods or service than governments due to free market competition. Over time this tends to lead to lower prices, improved quality, more choices, less corruption, less red tape and/or quicker delivery. Many proponents do not argue that everything should be privatized. Market failures and natural monopolies could be problematic.

Opponents of certain privatizations believe that certain public goods and services should remain primarily in the hands of government in order to ensure that everyone in society has access to them. There is a positive externality when the government provides society at large with public goods and services such as defense and disease control. Some national constitutions in effect define their governments’ core businesses as being the provision of such things as justice, tranquility, defense and general welfare. These governments’ direct provision of security, stability and safety is intended to be done for the common good with a long-term perspective. As for natural monopolies, opponents of privatization claim that they aren’t subject to fair competition and are better administrated by the state. Likewise, private goods and services should remain in the hands of the private sector.

14.4.2: The Power of Judicial Review

Judicial review is the doctrine where legislative and executive actions are subject to review by the judiciary.

Learning Objective

Explain the significance of judicial review in the history of the Supreme Court

Key Points

- Judicial review is an example of the separation of powers in a modern governmental system.

- Common law judges are seen as sources of law, capable of creating new legal rules and rejecting legal rules that are no longer valid. In the civil law tradition, judges are seen as those who apply the law, with no power to create or destroy legal rules.

- In the United States, judicial review is considered a key check on the powers of the other two branches of government by the judiciary.

Key Term

- doctrine

-

A belief or tenet, especially about philosophical or theological matters.

Judicial review is the doctrine under which legislative and executive actions are subject to review by the judiciary. Specific courts with judicial review power must annul the acts of the state when it finds them incompatible with a higher authority. Judicial review is an example of the separation of powers in a modern governmental system. This principle is interpreted differently in different jurisdictions, so the procedure and scope of judicial review differs from state to state.

Judicial review can be understood in the context of two distinct—but parallel—legal systems, civil law and common law, and also by two distinct theories on democracy and how a government should be set up, legislative supremacy and separation of powers. Common law judges are seen as sources of law, capable of creating new legal rules and rejecting legal rules that are no longer valid. In the civil law tradition, judges are seen as those who apply the law, with no power to create or destroy legal rules.

The separation of powers is another theory about how a democratic society’s government should be organized. First introduced by French philosopher Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu , separation of powers was later institutionalized in the United States by the Supreme Court ruling in Marbury v. Madison. It is based on the idea that no branch of government should be more powerful than any other and that each branch of government should have a check on the powers of the other branches of government, thus creating a balance of power among all branches of government. The key to this idea is checks and balances. In the United States, judicial review is considered a key check on the powers of the other two branches of government by the judiciary.

14.4.3: Judicial Activism and Restraint

Judicial activism is based on personal/political considerations and judicial restraint encourages judges to limit their power.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast judicial activist and judicial-restrained judges

Key Points

- Judicial activism describes judicial rulings suspected of being based on personal or political considerations rather than on existing law.

- Judicial restraint encourages judges to limit the exercise of their own power. It asserts that judges should hesitate to strike down laws unless they are obviously unconstitutional, though what counts as obviously unconstitutional is itself a matter of some debate.

- Detractors of judicial activism argue that it usurps the power of elected branches of government or appointed agencies, damaging the rule of law and democracy. Defenders say that in many cases it is a legitimate form of judicial review and that interpretations of the law must change with the times.

Key Term

- statutory

-

Of, relating to, enacted or regulated by a statute.

Judicial activism describes judicial rulings suspected of being based on personal or political considerations rather than on existing law. The definition of judicial activism and which specific decisions are activist, is a controversial political issue. The phrase is generally traced back to a comment by Thomas Jefferson, referring to the despotic behavior of Federalist federal judges, in particular, John Marshall. The question of judicial activism is closely related to constitutional interpretation, statutory construction and separation of powers.

Detractors of judicial activism argue that it usurps the power of elected branches of government or appointed agencies, damaging the rule of law and democracy. Defenders say that in many cases it is a legitimate form of judicial review and that interpretations of the law must change with the times.

Judicial restraint is a theory of judicial interpretation that encourages judges to limit the exercise of their own power. It asserts that judges should hesitate to strike down laws unless they are obviously unconstitutional, though what counts as obviously unconstitutional is itself a matter of some debate.

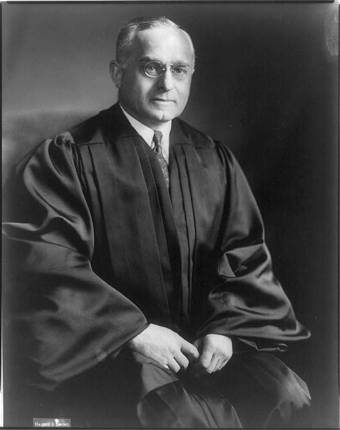

In deciding questions of constitutional law, judicially-restrained jurists go to great lengths to defer to the legislature. Former Associate Justice Oliver Holmes Jr. is considered to be one of the first major advocates of the philosophy. Former Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter , a Democrat appointed by Franklin Roosevelt, is generally seen as the model of judicial restraint.

Judicially-restrained judges respect stare decisis, the principle of upholding established precedent handed down by past judges. When Chief Justice Rehnquist overturned some of the precedents of the Warren Court, Time magazine said he was not following the theory of judicial restraint. However, Rehnquist was also acknowledged as a more conservative advocate of the philosophy.

Felix Frankfurter

Former Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter, one of the first major advocates to advocate deferring to the legislature.

14.4.4: The Supreme Court as Policy Makers

The Constitution does not grant the Supreme Court the power of judicial review but the power to overturn laws and executive actions.

Learning Objective

Discuss the constitutional powers and authority of the Supreme Court and its role in developing policies

Key Points

- The Supreme Court first established its power to declare laws unconstitutional in Marbury v. Madison (1803), consummating the system of checks and balances, allowing judges to have the last word on allocation of authority among the three branches of the federal government.

- The Supreme Court cannot directly enforce its rulings, but it relies on respect for the Constitution and for the law for adherence to its judgments.

- Through its power of judicial review, the Supreme Court has defined the scope and nature of the powers and separation between the legislative and executive branches of the federal government.

Key Term

- impeachment

-

the act of impeaching a public official, either elected or appointed, before a tribunal charged with determining the facts of the matter.

A policy is described as a principle or rule to guide decisions and achieve rational outcomes. The policy cycle is a tool used for the analyzing of the development of a policy item. A standardizes version includes agenda setting, policy formulation, adoption, implementation and evaluation.

The Constitution does not explicitly grant the Supreme Court the power of judicial review but the power of the Court to overturn laws and executive actions it deems unlawful or unconstitutional is well-established. Many of the Founding Fathers accepted the notion of judicial review. The Supreme Court first established its power to declare laws unconstitutional in Marbury v. Madison (1803), consummating the system of checks and balances. This power allows judges to have the last word on allocation of authority among the three branches of the federal government, which grants them the ability to set bounds to their own authority, as well as to their immunity from outside checks and balances.

Supreme Court

The Supreme Court holds the power to overturn laws and executive actions they deem unlawful or unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court cannot directly enforce its rulings, but it relies on respect for the Constitution and for the law for adherence to its judgments. One notable instance came in 1832, when the state of Georgia ignored the Supreme Court’s decision in Worcester v. Georgia. Some state governments in the south also resisted the desegregation of public schools after the 1954 judgment Brown v. Board of Education. More recently, many feared that President Nixon would refuse to comply with the Court’s order in United States v. Nixon (1974) to surrender the Watergate tapes. Nixon ultimately complied with the Supreme Court’s ruling.

Some argue that the Supreme Court is the most separated and least checked of all branches of government. Justices are not required to stand for election by virtue of their tenure during good behavior and their pay may not be diminished while they hold their position. Though subject to the process of impeachment, only one Justice has ever been impeached and no Supreme Court Justice has been removed from office. Supreme Court decisions have been purposefully overridden by constitutional amendment in only four instances: the Eleventh Amendment overturned Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), the13th and 14th Amendments in effect overturned Dred Scott v. Standford (1857), the 16th Amendment reversed Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan and Trust Co. (1895) and the 16th Amendment overturned some portions of Oregon v. Mitchell (1970). When the Court rules on matters involving the interpretation of laws rather than of the Constitution, simple legislative action can reverse the decisions. The Supreme Court is not immune from political and institutional restraints: lower federal courts and state courts sometimes resist doctrinal innovations, as do law enforcement officials.

On the other hand, through its power of judicial review, the Supreme Court has defined the scope and nature of the powers and separation between the legislative and executive branches of the federal government. The Court’s decisions can also impose limitations on the scope of Executive authority, as in Humphrey’s Executor v. United States (1935), the Steel Seizure Case (1952) and United States v. Nixon (1974).

14.4.5: Two Judicial Revolutions: The Rehnquist Court and the Roberts Court

The Rehnquist Court favored federalism and social liberalism, while the Roberts Court was considered more conservative.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast the Rehnquist Court and the Roberts Court

Key Points

- Rehnquist favored a conception of federalism that emphasized the Tenth Amendment’s reservation of powers to the states. Under this view of federalism, the Supreme Court, for the first time since the 1930s, struck down an Act of Congress as exceeding federal power under the Commerce Clause.

- In 1999, Rehnquist became the second Chief Justice to preside over a presidential impeachment trial, during the proceedings against President Bill Clinton.

- One of the Court’s major developments involved reinforcing and extending the doctrine of sovereign immunity, which limits the ability of Congress to subject non-consenting states to lawsuits by individual citizens seeking money damages.

- The Roberts Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States since 2005, under the leadership of Chief Justice John G. Roberts. It is generally considered more conservative than the preceding Rehnquist Court, as a result of the retirement of moderate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

- In its first five years, the Roberts court has issued major rulings on gun control. affirmative action, campaign finance regulation, abortion, capital punishment and criminal sentencing.

Key Term

- certiorari

-

A grant of the right of an appeal to be heard by an appellate court where that court has discretion to choose which appeals it will hear.

William Rehnquist served as an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States, and later as the 16th Chief Justice of the United States. When Chief Justice Warren Burger retired in 1986, President Ronald Reagan nominated Rehnquist to fill the position. The Senate confirmed his appointment by a 65-33 vote and he assumed office on September 26, 1986.

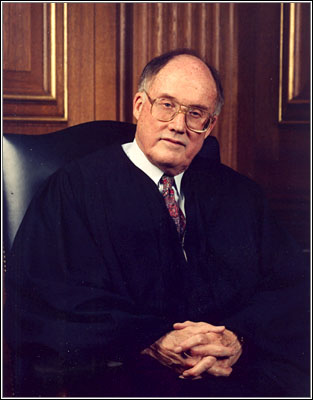

William Rehnquist

Former Chief Justice William Rehnquist

Considered a conservative, Rehnquist favored a conception of federalism that emphasized the Tenth Amendment’s reservation of powers to the states. Under this view of federalism, the Supreme Court, for the first time since the 1930s, struck down an Act of Congress as exceeding federal power under the Commerce Clause. He won over his fellow justices with his easygoing, humorous and unpretentious personality. Rehnquist also tightened up the justices’ conferences, keeping them from going too long or off track. He also successfully lobbied Congress in 1988 to give the Court control of its own docket, cutting back mandatory appeals an certiorari grants in general.

In 1999, Rehnquist became the second Chief Justice to preside over a presidential impeachment trial, during the proceedings against President Bill Clinton. In 2000, Rehnquist wrote a concurring opinion in Bush v. Gore, the case that effectively ended the presidential election controversy in Florida, that the Equal Protection Clause barred a standard-less manual recount of the votes as ordered by the Florida Supreme Court.

The Rehnquist Court’s congruence and proportionality standard made it easier to revive older precedents preventing Congress from going too far in enforcing equal protection of the laws. One of the Court’s major developments involved reinforcing and extending the doctrine of sovereign immunity, which limits the ability of Congress to subject non-consenting states to lawsuits by individual citizens seeking money damages.

Rehnquist presided as Chief Justice for nearly 19 years, making him the fourth-longest-serving Chief Justice after John Marshall, Roger Taney and Melville Fuller. He is the eighth longest-serving justice in Supreme Court history.

The Roberts Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States since 2005, under the leadership of Chief Justice John G. Roberts. It is generally considered more conservative than the preceding Rehnquist Court, as a result of the retirement of moderate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor and the subsequent confirmation of the more conservative Justice Samuel Alito in her place.

After the death of Chief Justice Rehnquist, Roberts was nominated by President George W. Bush, who had previously nominated him to replace Sandra Day O’Connor. The Senate confirmed his nomination by a vote of 78-22. Roberts took the Constitutional oath of office, administered by senior Associate Justice John Paul Stevens at the White House, on September 29, 2005, almost immediately after his confirmation. On October 3, he took the judicial oath provided for by the Judiciary Act of 1789, prior to the first oral arguments of the 2005 term.

In its first five years, the Roberts court issued major rulings on gun control. affirmative action, campaign finance regulation, abortion, capital punishment and criminal sentencing.

14.5: Federal Judicial Appointments

14.5.1: The Nomination Process

It is the president’s responsibility to nominate federal judges and the Senate’s responsibility to approve or reject the nomination.

Learning Objective

Explain how the nomination process represents the systems of checks and balances in the Constitution

Key Points

- The U.S. Constitution establishes “checks and balances” among the powers of the executive, legislative and judiciary branches. The nomination process of federal judges is an important part of this system.

- The Appointments Clause of the United States Constitution empowers the president to appoint certain public officials with the “advice and consent” of the U.S. Senate.

- .

- Certain factors influence who the president chooses to nominate for the Supreme Court: composition of the Senate, timing of the election cycle, public approval rate of the president, and the strength of interest groups.

- After the president makes a nomination, the Senate Judiciary Committee studies the nomination and makes a recommendation to the Senate.

Key Terms

- veto

-

A political right to disapprove of (and thereby stop) the process of a decision, a law, etc.

- judiciary

-

The court system and judges considered collectively, the judicial branch of government.

- Senate Judiciary Committee

-

A standing committee of the US Senate, the 18-member committee is charged with conducting hearings prior to the Senate votes on confirmation of federal judges (including Supreme Court justices) nominated by the President.

Checks and Balances

One of the theoretical pillars of the United States Constitution is the idea of checks and balances among the powers of the executive, legislative and judiciary branches. For example, while the legislative (Congress) has the power to create law, the executive (president) can veto any legislation; an act that can be overridden by Congress. The president nominates judges to the nation’s highest judiciary authority (Supreme Court), but Congress must approve those nominees. The Supreme Court, meanwhile, has the power to invalidate as unconstitutional any law passed by the Congress. Thus, the nomination and appointment process of federal judges serves as an important component of the checks and balances process.

The Appointment Clause of the Constitution

The president has the power to nominate candidates for Supreme Court and other federal judge positions based on the Appointments Clause of the United States Constitution. This clause empowers the president to appoint certain public officials with the “advice and consent” of the U.S. Senate. Acts of Congress have established 13 courts of appeals (also called “circuit courts”) with appellate jurisdiction over different regions of the country. Every judge appointed to the court may be categorized as a federal judge with approval from the Senate.

The Nomination Process

The president nominates all federal judges, who must then be approved by the Senate . The appointment of judges to lower federal courts is important because almost all federal cases end there. Through lower federal judicial appointments, a president “has the opportunity to influence the course of national affairs for a quarter of a century after he leaves office.” Once in office, federal judges can be removed only by impeachment and conviction. Judges may time their departures so that their replacements are appointed by a president who shares their views. For example, Supreme Court Justice Souter retired in 2009 and Justice Stevens in 2010, enabling President Obama to nominate – and the Democratic controlled Senate to confirm – their successors. A recess appointment is the appointment, by the President of the United States, of a senior federal official while the U.S. Senate is in recess. To remain in effect a recess appointment must be approved by the Senate by the end of the next session of Congress, or the position becomes vacant again; in current practice this means that a recess appointment must be approved by roughly the end of the next calendar year.

Chief Justice Roberts

John G. Roberts, Jr., Chief Justice of the United States of America. Federal judges, such as Supreme Court Justices, must be nominated.

Choosing Supreme Court Justices