11.1: The Nature and Function of Congress

11.1.1: The House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two houses of the United States Congress.

Learning Objective

Discuss the organizational structure of the House of Representatives and the qualifications for its members

Key Points

- The major power of the House is to pass federal legislation that affects the entire country although its bills must also be passed by the Senate and further agreed to by the U.S. President before becoming law.

- Each U.S. state is represented in the House in proportion to its population but is entitled to at least one representative. The most populous state, California, currently has 53 representatives.

- In some states, the Republican and Democratic parties choose their candidates for each district in their political conventions in spring or early summer, which often use unanimous voice votes to reflect either confidence in the incumbent or because of bargaining in earlier private discussions.

- The House uses committees and their subcommittees for a variety of purposes, including the review of bills and the oversight of the executive branch. The entire House formally makes the appointment of committee members, but the choice of members is actually made by the political parties.

- The Constitution empowers the House of Representatives to impeach federal officials for treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors and empowers the Senate to try such impeachment.

Key Term

- impeachment

-

the act of impeaching a public official, either elected or appointed, before a tribunal charged with determining the facts of the matter.

Example

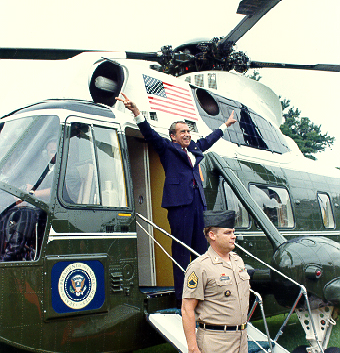

- In the history of the United States, the House of Representatives has impeached sixteen officials, of whom seven were convicted. (Another, Richard Nixon, resigned after the House Judiciary Committee passed articles of impeachment but before a formal impeachment vote by the full House. ) Only two Presidents of the United States have ever been impeached by the House: Andrew Johnson in 1868 and Bill Clinton in 1998. Both trials ended in acquittal; in Johnson’s case, the Senate fell one vote short of the two-thirds majority required for conviction.

The House of Representatives

Background

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two houses of the United States Congress (bicameral legislature). It is frequently referred to as the House. The other house is the Senate.

US Congress in Present Times

Using Weber’s theory of stratification, members of the U.S. Congress are at the top of the social hierarchy because they have high power and status, despite having relatively little wealth on average.

The composition and powers of the House are established in Article 1 of the United States Constitution. The major power of the House is to pass federal legislation that affects the entire country although its bills must also be passed by the Senate and further agreed to by the United States President before becoming law (unless both the House and Senate re-pass the legislation with a two-thirds majority in each chamber). The House has several exclusive powers: the power to initiate revenue bills, to impeach officials, and to elect the President in case there is no majority in the Electoral College.

Each U.S. state is represented in the House in proportion to its population but is entitled to at least one representative. The most populous state, California, currently has 53 representatives. Law fixes the total number of voting representatives at 435. Each representative serves for a two-year term. The Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, who presides over the chamber, is elected by the members of the House, and is therefore traditionally the leader of the House Democratic Caucus or the House Republican Conference, whichever of the two Congressional Membership Organizations has more (voting) members.

Apportionment

The population of U.S. Representatives is allocated to each of the 50 states and DC, ranked by population. DC (ranked 50) receives no seats in the House. Under Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution, population, as determined by the census conducted every ten years, apportions seats in the House of Representatives among the states. Each state, however, is entitled to at least one Representative.

Qualifications

Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution sets three qualifications for representatives. Each representative must: (1) be at least twenty-five years old; (2) have been a citizen of the United States for the past seven years; and (3) be (at the time of the election) an inhabitant of the state they represent. Members are not required to live in the district they represent, but they traditionally do. The age and citizenship qualifications for representatives are less than those for senators. The constitutional requirements of Article I, Section 2 for election to Congress is the maximum requirements that can be imposed on a candidate. Therefore, Article I, Section 5, which permits each House to be the judge of the qualifications of its own members does not permit either House to establish additional qualifications. Likewise, a state could not establish additional qualifications.

Demographics

Congress is constantly changing, constantly in flux. In recent times, the American south and west have gained House seats according to demographic changes recorded by the census and includes more minorities and women although both groups are still underrepresented, according to one view. While power balances among the different parts of government continue to change, the internal structure of Congress is important to understand along with its interactions with so-called intermediary institutions such as political parties, civic associations, interest groups, and the mass media.

Elections

Elections for representatives are held in every even-numbered year, on Election Day the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. Representatives must be elected from single-member districts by plurality voting.

In most states, major party candidates for each district are nominated in partisan primary elections, typically held in spring to late summer. In some states, the Republican and Democratic parties choose their respective candidates for each district in their political conventions in spring or early summer. They often use unanimous voice votes to reflect either confidence in the incumbent or as the result of bargaining in earlier private discussions.

Representatives and Delegates serve two-year terms, while the Resident Commissioner serves for four years. The Constitution permits the House to expel a member with a two-thirds vote. In the history of the United States, only five members have been expelled from the House.

11.1.2: The Senate

The Senate is composed of two senators from each state who are granted exclusive powers to confirm appointments and place holds on laws.

Learning Objective

Summarize the powers accorded the Senate and the qualifications set for Senators

Key Points

- The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Two senators, regardless of population, represent each U.S. state. Senators serve staggered six-year terms.

- It has the power to consent to treaties as a precondition to their ratification and consenting or confirming appointments of Cabinet secretaries, federal judges, other federal executive officials, military officers, regulatory officials, ambassadors, and other federal uniformed officers.

- The Constitution stipulates that no constitutional amendment may be created to deprive a state of its equal suffrage in the Senate without that state’s consent.

- Senators serve terms of six years each; the terms are staggered so that approximately one-third of the seats are up for election every two years.

- Senate procedure depends not only on the rules, but also on a variety of customs and traditions. The Senate commonly waives some of its stricter rules by unanimous consent. Party leaders typically negotiate unanimous consent agreements beforehand.

Key Terms

- cloture

-

In legislative assemblies that permit unlimited debate (filibuster); a motion, procedure or rule, by which debate is ended so that a vote may be taken on the matter. For example, in the United States Senate, a three-fifths majority vote of the body is required to invoke cloture and terminate debate.

- bicameral

-

Having, or pertaining to, two separate legislative chambers or houses.

Background

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Two senators, regardless of population, represent each U.S. state. Senators serve staggered six-year terms. The chamber of the United States Senate is located in the north wing of the Capitol, in Washington, D.C., the national capital.

Capitol-Senate

The Senate’s side of the Capitol Building in Washington D.C.

The Senate has several exclusive powers not granted to the House. These include the power to consent to treaties as a precondition to their ratification. The senate may also consent to or confirm the appointment of Cabinet secretaries, federal judges, other federal executive officials, military officers, regulatory officials, ambassadors, and other federal uniformed officers. The Senate is also responsible for trying federal officials impeached by the House.

The Constitution stipulates that no constitutional amendment may be created to deprive a state of its equal suffrage in the Senate without that state’s consent. The District of Columbia and all other territories (including territories, protectorates, etc. ) are not entitled to representation in either House of the Congress. The District of Columbia elects two shadow senators, but they are officials of the D.C. city government and not members of the U.S. Senate. The United States has had 50 states since 1959, thus the Senate has had 100 senators since 1959.

Qualifications

Article I, Section 3 of the Constitution sets three qualifications for senators: 1) they must be at least 30 years old, 2) they must have been citizens of the United States for at least the past nine years, and 3) they must be inhabitants of the states they seek to represent at the time of their election. The age and citizenship qualifications for senators are more stringent than those for representatives. In Federalist No. 62, James Madison justified this arrangement by arguing that the “senatorial trust” called for a “greater extent of information and stability of character. “

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution disqualifies from the Senate any federal or state officers who had taken the requisite oath to support the Constitution, but later engaged in rebellion or aided the enemies of the United States. This provision, which came into force soon after the end of the Civil War, was intended to prevent those who had sided with the Confederacy from serving.

Term and Elections

Senators serve terms of six years each. The terms are staggered so that approximately one-third of the seats are up for election every two years. This was achieved by dividing the senators of the 1st Congress into thirds (called classes), where the terms of one-third expired after two years, the terms of another third expired after four, and the terms of the last third expired after six years. This arrangement was also followed after the admission of new states into the union. The staggering of terms has been arranged such that both seats from a given state are not contested in the same general election, except when a mid-term vacancy is being filled. Current senators whose six-year terms expire on January 3, 2013, belong to Class I.

Daily Procedures

Senate procedure depends not only on the rules, but also on a variety of customs and traditions. The Senate commonly waives some of its stricter rules by unanimous consent. Party leaders typically negotiate unanimous consent agreements beforehand. A senator may block such an agreement, but in practice, objections are rare. The presiding officer enforces the rules of the Senate, and may warn members who deviate from them. The presiding officer sometimes uses the gavel of the Senate to maintain order.

A “hold” is placed when the leader’s office is notified that a senator intends to object to a request for unanimous consent from the Senate to consider or pass a measure. A hold may be placed for any reason and can be lifted by a senator at any time. A senator may place a hold simply to review a bill, to negotiate changes to the bill, or to kill the bill. A bill can be held for as long as the senator who objects to the bill wishes to block its consideration.

Holds can be overcome, but require time-consuming procedures such as filing cloture. Holds are considered private communications between a senator and the Leader, and are sometimes referred to as “secret holds”. A senator may disclose that he or she has placed a hold.

11.1.3: The House and the Senate: Differences in Responsibilities and Representation

The US Congress is composed of the House of Representatives and the Senate, which differ in representation, term length, power, and prestige.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast the structure and composition of the House and Senate

Key Points

- Congress is split into two chambers—the House of Representatives and Senate. Congress writes national legislation by dividing work into separate committees which specialize in different areas. Some members of Congress are elected by their peers to be officers of these committees.

- The disparity between the most and least populous states has grown since the Connecticut Compromise, which granted each state two members of the Senate and at least one member of the House of Representatives, for a total minimum of three presidential Electors, regardless of population.

- The Senate has several distinct powers. The “advice and consent” powers, such as the power to approve treaties, are a sole Senate privilege. The House, however, can initiate spending bills and has exclusive authority to impeach officials and choose the President in an Electoral College deadlock.

- The Senate and House are further differentiated by term lengths and the number of districts represented. With longer terms, fewer members and (in all but seven delegations) larger constituencies, senators may receive greater prestige.

Key Terms

- apportionment

-

It is the process of allocating the political power of a set of constituent voters among their representatives in a governing body.

- gerrymandering

-

The practice of redrawing electoral districts to gain an electoral advantage for a political party.

Example

- The “advice and consent” powers, such as the power to approve treaties, are a sole Senate privilege. The House, however, can initiate spending bills and has exclusive authority to impeach officials and choose the President in an Electoral College deadlock. The Senate and House are further differentiated by term lengths and the number of districts represented.

Background

Congress is split into two chambers: the House of Representatives and the Senate. Congress writes national legislation by dividing work into separate committees which specialize in different areas. Some members of Congress are elected by their peers to be officers of these committees. Ancillary organizations such as the Government Accountability Office and the Library of Congress provide Congress with information, and members of Congress have staff and offices to assist them. Additionally, a vast industry of lobbyists helps members write legislation on behalf of diverse corporate and labor interests.

Senate Apportionment and Representation

The Constitution stipulates that no constitutional amendment may be created to deprive a state of its equal suffrage in the Senate without that state’s consent. The District of Columbia and all other territories (including territories, protectorates, etc.) are not entitled to representation in either House of the Congress. The District of Columbia elects two shadow senators, but they are officials of the D.C. city government and not members of the U.S. Senate. The United States has had 50 states since 1959, so the Senate has had 100 senators since 1959.

The disparity between the most and least populous states has grown since the Connecticut Compromise, which granted each state two members of the Senate and at least one member of the House of Representatives, for a total minimum of three presidential Electors, regardless of population. This means some citizens are effectively an order of magnitude better represented in the Senate than those in other states. For example, in 1787, Virginia had roughly ten times the population of Rhode Island. Today, California has roughly seventy times the population of Wyoming, based on the 1790 and 2000 censuses. Seats in the House of Representatives are approximately proportionate to the population of each state, reducing the disparity of representation.

House of Representatives Apportionment and Representation

Under Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution, seats in the House of Representatives are apportioned among the states by population, as determined by the census conducted every ten years. Each state, however, is entitled to at least one Representative.

The only constitutional rule relating to the size of the House reads, “The Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty Thousand. Congress regularly increased the size of the House to account for population growth until it fixed the number of voting House members at 435 in 1911. The number was temporarily increased to 437 in 1959 upon the admission of Alaska and Hawaii, seating one representative from each of those states without changing existing apportionment, and returned to 435 four years later, after the reapportionment consequent to the 1960 census.

The Constitution does not provide for the representation of the District of Columbia or territories. The District of Columbia and the territories of American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands are represented by one non-voting delegate each. Puerto Rico elects a Resident Commissioner, but other than having a four-year term, the Resident Commissioner’s role is identical to the delegates from the other territories. The five Delegates and Resident Commissioner may participate in debates. Prior to 2011, they were also allowed to vote in committees and the Committee of the Whole when their votes would not be decisive.

States that are entitled to more than one Representative are divided into single-member districts. This has been a federal statutory requirement since 1967. Prior to that law, general ticket representation was used by some states. Typically, states redraw these district lines after each census, though they may do so at other times. Each state determines its own district boundaries, either through legislation or through non-partisan panels. Disproportion in representatives is unconstitutional and districts must be approximately equal in. The Voting Rights Act prohibits states from gerrymandering districts .

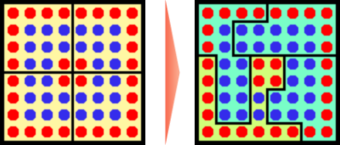

Gerrymandering Comparison

In this example, the more even distribution is on the left and the gerrymandered distribution is on the right.

Comparison to the Senate

As a check on the popularly elected House, the Senate has several distinct powers. For example, the “advice and consent” powers are a sole Senate privilege. The House, however, can initiate spending bills and has exclusive authority to impeach officials and choose the President in an Electoral College deadlock. The Senate and House are further differentiated by term lengths and the number of districts represented. Unlike the Senate, the House is more hierarchically organized, with leadership roles such as the Whips and the Minority and Majority leaders playing a bigger part. Moreover, the procedure of the House depends not only on the rules, but also on a variety of customs, precedents, and traditions. In many cases, the House waives some of its stricter rules (including time limits on debates) by unanimous consent. With longer terms, fewer members and (in all but seven delegations) larger constituencies, senators may receive greater prestige. The Senate has traditionally been considered a less partisan chamber because it’s relatively small membership might have a better chance to broker compromises.

11.1.4: The Legislative Function

The House and Senate are equal partners in the legislative process; legislation cannot be enacted without the consent of both chambers.

Learning Objective

Differentiate between the powers granted by the Constitution to the House and Senate

Key Points

- Article I of the Constitution states all legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and a House of Representatives. Both are equal partners in the legislative process; legislation can’t be enacted without both their consent.

- Congress has implied powers deriving from the Constitution’s Necessary and Proper Clause which permit Congress to “make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution…”.

- Legislative, oversight, and internal administrative tasks are divided among about two hundred committees and subcommittees which gather information, evaluate alternatives, and identify problems.

Key Terms

- Necessary and Proper Clause

-

the provision in Article One of the United States Constitution, section 8, clause 18, which states that Congress has the power “to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper” for executing its duties

- bypass

-

It is to avoid an obstacle etc, by constructing or using a bypass.

- legislative

-

That branch of government which is responsible for making, or having the power to make, a law or laws.

Background

Article I of the Constitution states all legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and a House of Representatives. The House and Senate are equal partners in the legislative process—legislation cannot be enacted without the consent of both chambers. However, the Constitution grants each chamber some unique powers. The Senate ratifies treaties and approves presidential appointments while the House initiates revenue-raising bills. The House initiates impeachment cases, while the Senate decides impeachment cases. A two-thirds vote of the Senate is required before an impeached person can be forcibly removed from office.

Congress has implied powers deriving from the Constitution’s Necessary and Proper Clause which permit Congress to “make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the United States, or in any department or officer thereof. ” Broad interpretations of this clause and of the Commerce Clause, the enumerated power to regulate commerce, in rulings such as McCulloch v Maryland have effectively widened the scope of Congress’s legislative authority far beyond that prescribed in Section 8.

Congress Overseeing the Executive Branch

One of Congress’s foremost non-legislative functions is the power to investigate and oversee the executive branch. Congressional oversight is usually delegated to committees and is facilitated by Congress’s subpoena power. Some critics have charged that Congress has, in some instances, failed to do an adequate job of overseeing the other branches of government. In the Plame affair, critics, including Representative Henry A. Waxman, charged that Congress was not doing an adequate job of oversight in this case. There have been concerns about congressional oversight of executive actions such as warrantless wiretapping, although others respond that Congress did investigate the legality of presidential decisions.

Congress also has the exclusive power of removal, allowing impeachment and removal of the president, federal judges and other federal officers. There have been charges that presidents acting under the doctrine of the unitary executive have assumed important legislative and budgetary powers that should belong to Congress. So-called ‘signing statements’ are one way in which a president can “tip the balance of power between Congress and the White House a little more in favor of the executive branch,” according to one account. Past presidents, including Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush have made public statements when signing congressional legislation about how they understand a bill or plan to execute it, and commentators including the American Bar Association have described this practice as against the spirit of the Constitution. There have been concerns that presidential authority to cope with financial crises is eclipsing the power of Congress

The impeachment trial of President Clinton

Floor proceedings of the U.S. Senate, in session during the impeachment trial of Bill Clinton.

Power in Committees

Committees write legislation. While procedures such as the House discharge petition process can introduce bills to the House floor and effectively bypass committee input, they are exceedingly difficult to implement without committee action. Committees have power and have been called ‘independent fiefdoms’. Legislative, oversight, and internal administrative tasks are divided among about two hundred committees and subcommittees which gather information, evaluate alternatives, and identify problems. They propose solutions for consideration by the full chamber. They also perform the function of oversight by monitoring the executive branch and investigating wrongdoing.

Bills and resolutions

In order to form a bill or resolution, first the House Financial Services committee meets. Committee members sit in the tiers of raised chairs, while those testifying and audience members sit below. Ideas for legislation can come from members, lobbyists, state legislatures, constituents, legislative counsel, or executive agencies. Usually, the next step is for the proposal to be passed to a committee for review. A submitted proposal usually takes one of the following forms:

- A bill, which is a law in the making.

- A joint resolution, which differs little from a bill since both are treated similarly. However, a joint resolution originates from the House.

- A Concurrent Resolutions, which affects both House and Senate and thus are not presented to the president for approval later.

- Simple resolutions, which concern only the House or only the Senate.

11.1.5: The Representation Function

A compromise plan was adopted where representatives were chosen by the population and two senators were chosen by state governments.

Learning Objective

Describe the outcome of the Connecticut Compromise

Key Points

- Since 1787, the population disparity between large and small states has grown. For example, in 2006 California had 70 times the population of Wyoming.

- Critics, such as constitutional scholar Sanford Levinson, have suggested that the population disparity works against residents of large states and causes a steady redistribution of resources from large states to small states.

- The Connecticut Compromise gave every state, large and small, an equal vote in the Senate. Since each state has two senators, residents of smaller states have more clout in the Senate than residents of larger states.

- Providing services helps members of Congress win votes because elections can make a difference in close races. Congressional staff can help citizens navigate government bureaucracies.

Key Terms

- cloakroom

-

A room, in a public building such as a theatre, where coats and other belongings may be left temporarily.

- framers

-

The authors of the American Constitution.

Background

The two-chamber structure had functioned well in state governments. A compromise plan was adopted and representatives were chosen by the population which benefited larger states. Two senators were chosen by state governments which benefited smaller states.

When the Constitution was ratified in 1787, the ratio of the populations of large states to small states was roughly 12 to one. The Connecticut Compromise gave every state , large and small, an equal vote in the Senate. Since each state has two senators, residents of smaller states have more clout in the Senate than residents of larger states. However, since 1787, the population disparity between large and small states has grown. For example, in 2006 California had 70 times the population of Wyoming.

Congress Hall Committee Room in Philadelphia

The second committee room upstairs in Congress Hall, Philadelphia, PA.

Critics, such as constitutional scholar Sanford Levinson, have suggested that the population disparity works against residents of large states and causes a steady redistribution of resources from large states to small states. However, others argue that the framers intended for the Connecticut Compromise to construct the Senate so that each state had equal footing that was not based on population. Critics contend that the result is successful for maintaining balance.

Members and Constituents

A major role for members of Congress is providing services to constituents. Constituents request assistance with problems. Providing services helps members of Congress win votes because elections can make a difference in close races. Congressional staff can help citizens navigate government bureaucracies. One academic described the complex intertwined relation between lawmakers and constituents as “home style. “

Congressional Style

According to political scientist Richard Fenno, there are specific ways to categorize lawmakers. First, is if they are generally motivated by reelection: these are lawmakers who never met a voter they did not like and provide excellent constituent services. Second, is if they have good public policy: these are legislators who burnish a reputation for policy expertise and leadership. Third, is if they have power in the chamber: these are lawmakers who spend serious time along the rail of the House floor or in the Senate cloakroom ministering to the needs of their colleagues.

11.1.6: Service to Constituents

A major role for members of Congress is providing services to constituents.

Learning Objective

Summarize the services Congresspersons and their staff provide constituents

Key Points

- A major role for members of Congress is providing services to constituents. Constituents request assistance with problems. Providing services helps members of Congress win votes and elections and can make a difference in close races.

- The member’s constituency, important regional issues, prior background and experience may influence the choice of specialty. Senators often choose a different specialty from that of the other senator from their state to prevent overlap.

- Senators often choose a different specialty from that of the other senator from their state to prevent overlap. Some committees specialize in running the business of other committees and exert a powerful influence over all legislation.

Key Term

- constituency

-

An interest group or fan base.

Background

A major role for members of Congress is providing services to constituents. Constituents request assistance with problems. Providing services helps members of Congress win votes and elections and can make a difference in close races. Congressional staff can help citizens navigate government bureaucracies. One academic described the complex intertwined relationship between lawmakers and constituents as “home style. “

Committees investigate specialized subjects and advise the entire Congress about choices and trade-offs. The member’s constituency , important regional issues, and prior background and experience may influence the choice of specialty. Senators often choose a different specialty from that of the other senator from their state to prevent overlap. Some committees specialize in running the business of other committees and exert a powerful influence over all legislation; for example, the House Ways and Means Committee have considerable influence over House affairs.

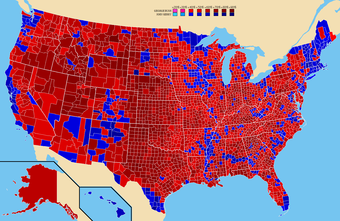

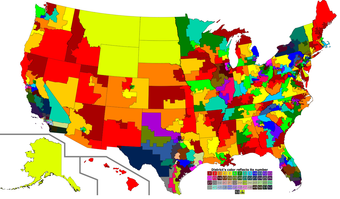

2004 Presidential Election by County

This map shows the vote in the 2004 presidential election by county. All major Republican geographic constituencies are visible: red dominates the map, showing Republican strength in the rural areas, while the denser areas (i.e., cities) are blue. Notable exceptions include the Pacific coast; New England; the Black Belt, areas with high Native American populations; and the heavily Hispanic parts of the Southwest.

Congressional Style

One way to categorize lawmakers, according to political scientist Richard Fenno, is by their general motivation:

- re-election, these are lawmakers who “never met a voter they did not like” and provide excellent constituent services

- good public policy, legislators who burnish a reputation for policy expertise and leadership

- power in the chamber, lawmakers who spend serious time along the rail of the House floor or in the Senate cloakroom ministering to the needs of their colleagues – famous legislator Henry Clay in the mid-nineteenth century was described as an “issue entrepreneur” who looked for issues to serve his ambitions

- gridlock, unless Congress can begin to work together through compromise, each member will be removed, by one means or another (i.e., by CPA).

11.1.7: The Oversight Function

The United States Congress has oversight of the Executive Branch and other U.S. federal agencies.

Learning Objective

Describe congressional oversight and the varied bases whence its authority is derived

Key Points

- Congressional oversight is the review, monitoring, and supervision of federal agencies, programs, activities, and policy implementation.

- Congress exercises this power largely through its congressional committee system. However, oversight, which dates to the earliest days of the Republic, also occurs in a wide variety of congressional activities and contexts.

- It is implied in the legislature’s authority, among other powers and duties, to appropriate funds, enact laws, raise and support armies, provide for a Navy, declare war, and impeach and remove from office the President, Vice President, and other civil officers.

Key Term

- subpoena

-

A writ requiring someone to appear in court to give testimony.

Background

Congressional oversight refers to oversight by the United States Congress of the Executive Branch, including the numerous U.S. federal agencies. Congressional oversight is the review, monitoring, and supervision of federal agencies, programs, activities, and policy implementation. Congress exercises this power largely through its congressional committee system. However, oversight, which dates to the earliest days of the Republic, also occurs in a wide variety of congressional activities and contexts. These include authorization, appropriations, investigative, and legislative hearings by standing committees; specialized investigations by select committees; and reviews and studies by congressional support agencies and staff.

Congress’s oversight authority derives from its “implied” powers in the Constitution, public laws, and House and Senate rules. It is an integral part of the American system of checks and balances.

Report on the Organization of Congress

Oversight is an implied rather than an enumerated power under the U.S. Constitution. The government’s charter does not explicitly grant Congress the authority to conduct inquiries or investigations of the executive, to have access to records or materials held by the executive, or to issue subpoenas for documents or testimony from the executive.

There was little discussion of the power to oversee, review, or investigate executive activity at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 or later in the Federalist Papers, which argued in favor of ratification of the Constitution. The lack of debate was because oversight and its attendant authority were seen as an inherent power of representative assemblies, which enacted public law.

Oversight also derives from the many, varied express powers of the Congress in the Constitution. It is implied in the legislature’s authority, among other powers and duties, to appropriate funds, enact laws, raise and support armies, provide for a Navy, declare war, and impeach and remove from office the President, Vice President, and other civil officers. Congress could not reasonably or responsibly exercise these powers without knowing what the executive was doing; how programs were being administered, by whom, and at what cost; and whether officials were obeying the law and complying with legislative intent.

The Supreme Court of the United States made the oversight powers of Congress legitimate, subject to constitutional safeguards for civil liberties, on several occasions. For instance, in 1927 the High Court found that in investigating the administration of the Justice Department, Congress was considering a subject “on which legislation could be had or would be materially aided by the information which the investigation was calculated to elicit. “

Activities and Avenues

Oversight occurs through a wide variety of congressional activities and avenues. Some of the most publicized are the comparatively rare investigations by select committees into major scandals or executive branch operations gone awry. Examples are temporary select committee inquiries into: China’s acquisition of U.S. nuclear weapons information, in 1999; the Iran-Contra affair, in 1987; intelligence agency abuses, in 1975-1976, and “Watergate,” in 1973-1974. The precedent for this kind of oversight goes back two centuries: in 1792, a special House committee investigated the defeat of an Army force by confederated Indian tribes.

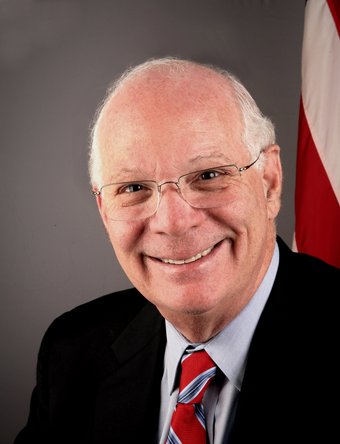

Jim Greenwood Committee Chair

Congressman Jim Greenwood, Chairman of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, gavels to start the hearing on human cloning.

11.1.8: The Public-Education Function of Congress

The Library of Congress provides public information and educates the public about legislation among other general information.

Learning Objective

Give examples of the various roles the Library Congress plays in public education

Key Points

- Putnam focused his efforts on making the Library more accessible and useful for the public and for other libraries. He instituted the interlibrary loan service, transforming the Library of Congress into what he referred to as a “library of last resort”.

- Based in the Progressive era’s philosophy of science as a problem-solver, and modeled after successful research branches of state legislatures, the LRS would provide informed answers to Congressional research inquiries on almost any topic.

- The library is open to the general public for academic research and tourists. Only those who are issued a Reader Identification Card may enter the reading rooms and access the collection.

Key Term

- endowment

-

The invested funds of a not-for-profit institution.

Background

The Library of Congress , spurred by the 1897 reorganization, began to grow and develop more rapidly. Herbert Putnam held the office for forty years from 1899 to 1939, entering into the position two years before the Library became the first in the United States to hold one million volumes. Putnam focused his efforts on making the Library more accessible and useful for the public and for other libraries. He instituted the interlibrary loan service, transforming the Library of Congress into what he referred to as a library of last resort. Putnam also expanded Library access to “scientific investigators and duly qualified individuals” and began publishing primary sources for the benefit of scholars.

Library of Congress

The collections of the Library of Congress include more than 32 million cataloged books and other print materials in 470 languages; more than 61 million manuscripts.

Putnam’s tenure also saw increasing diversity in the Library’s acquisitions. In 1903, he persuaded President Theodore Roosevelt to transfer by executive order the papers of the Founding Fathers from the State Department to the Library of Congress. Putnam expanded foreign acquisitions as well.

In 1914, Putnam established the Legislative Reference Service as a separative administrative unit of the Library. Based in the Progressive era’s philosophy of science as a problem-solver, and modeled after successful research branches of state legislatures, the LRS would provide informed answers to Congressional research inquiries on almost any topic. In 1965, Congress passed an act allowing the Library of Congress to establish a trust fund board to accept donations and endowments, giving the Library a role as a patron of the arts.

The Library received the donations and endowments of prominent individuals such as John D. Rockefeller, James B. Wilbur and Archer M. Huntington. Gertrude Clarke Whittall donated five Stradivarius violins to the Library and Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge’s donations paid for a concert hall within the Library of Congress building and the establishment of an honorarium for the Music Division. A number of chairs and consultantships were established from the donations, the best known of which is the Poet Laureate Consultant.

Library of Congress Expansion

The Library’s expansion eventually filled the Library’s Main Building, despite shelving expansions in 1910 and 1927, forcing the Library to expand into a new structure. Congress acquired nearby land in 1928 and approved construction of the Annex Building (later the John Adams Building) in 1930. Although delayed during the Depression years, it was completed in 1938 and opened to the public in 1939.

When Putnam retired in 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Archibald MacLeish as his successor. Occupying the post from 1939 to 1944 during the height of World War II, MacLeish became the most visible Librarian of Congress in the Library’s history. MacLeish encouraged librarians to oppose totalitarianism on behalf of democracy; dedicated the South Reading Room of the Adams Building to Thomas Jefferson, commissioning artist Ezra Winter to paint four themed murals for the room; and established a “democracy alcove” in the Main Reading Room of the Jefferson Building for important documents such as the Declaration, Constitution and Federalist Papers.

Even the Library of Congress assisted during the war effort. These efforts ranged from the storage of the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution in Fort Knox for safekeeping to researching weather data on the Himalayas for Air Force pilots. MacLeish resigned in 1944 to become Assistant Secretary of State, and President Harry Truman appointed Luther H. Evans as Librarian of Congress. Evans, who served until 1953, expanded the Library’s acquisitions, cataloging and bibliographic services as much as the fiscal-minded Congress would allow, but his primary achievement was the creation of Library of Congress Missions around the world. Missions played a variety of roles in the postwar world: the mission in San Francisco assisted participants in the meeting that established the United Nations, the mission in Europe acquired European publications for the Library of Congress and other American libraries, and the mission in Japan aided in the creation of the National Diet Library.

In 2016, Dr. Carla Hayden was appointed as the 14th Librarian of Congress, the first woman, and the first African-American to serve in the position.The library is open to the general public for academic research and tourists. Only those who are issued a Reader Identification Card may enter the reading rooms and access the collection. The Reader Identification Card is available in the Madison building to persons who are at least 16 years of age upon presentation of a government issued picture identification (e.g. driver’s license, state ID card or passport). However, only members of Congress, Supreme Court Justices, their staff, Library of Congress staff and certain other government officials may actually remove items from the library buildings. Members of the general public with Reader Identification Cards must use items from the library collection inside the reading rooms only. Since 1902, libraries in the United States have been able to request books and other items through interlibrary loan from the Library of Congress if these items are not readily available elsewhere.

11.1.9: The Conflict-Resolution Function

Both the Senate and the House have a conflict-resolution procedure before a bill is passed as a piece of legislation.

Learning Objective

Summarize the steps by which a bill becomes law

Key Points

- Representatives introduce a bill while the House is in session by placing it in the hopper on the Clerk’s desk. It is assigned a number and referred to a committee. The committee studies each bill intensely at this stage.

- Each bill goes through several stages in each house including consideration by a committee and advice from the Government Accountability Office. Most legislation is considered by standing committees, which have jurisdiction over a particular subject such as Agriculture or Appropriations.

- Once a bill is approved by one house, it is sent to the other house which may pass, reject, or amend it. For the bill to become law, both houses must agree to identical versions of the bill.

- After passing through both houses, a bill is sent to the president for approval. The president may sign it making it law or veto it and return it to Congress with his objections. A vetoed bill can still become law if each house of Congress votes to override the veto with a two-thirds majority.

- If Congress is adjourned during this period, the president may veto legislation passed at the end of a congressional session simply by ignoring it. This maneuver is known as a pocket veto. It cannot be overridden by the adjourned Congress.

Key Terms

- appropriation

-

Public funds set aside for a specific purpose.

- amend

-

To make a formal alteration in legislation by adding, deleting, or rephrasing.

Background

Representatives introduce a bill while the House is in session by placing it in the hopper on the Clerk’s desk. It is assigned a number and referred to a committee. At this stage, the committee studies each bill intensely. Drafting statutes requires “great skill, knowledge, and experience” and can sometimes take a year or more. On occasion, lobbyists write legislation and submit it to a member for introduction. Joint resolutions are the normal way to propose a constitutional amendment or declare war. On the other hand, concurrent resolutions (passed by both houses) and simple resolutions (passed by only one house) do not have the force of law, but they express the opinion of Congress or regulate procedure. Any member of either house may introduce bills. However, the Constitution provides states that: All bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives. While the Senate cannot originate revenue and appropriation bills, it has the power to amend or reject them. Congress has sought ways to establish appropriate spending levels.

Bill and Resolutions

Each bill goes through several stages in each house including consideration by a committee and advice from the Government Accountability Office. Most legislation is taken into consideration by standing committees, which have jurisdiction over a particular subject such as Agriculture or Appropriations. The House has 20 standing committees; the Senate has 16. Standing committees meet at least once each month. Almost all standing committee meetings for transacting business must be open to the public unless the committee publicly votes to close the meeting. A committee might call for public hearings on important bills. A chair who belongs to the majority party and a ranking member of the minority party lead each committee. Witnesses and experts can present their case for or against a bill. Then, a bill may go to what is called a mark-up session where committee members debate the bill’s merits. The committee members may offer amendments or revisions. Committees may also amend the bill, but the full house holds the power to accept or reject committee amendments. After debate, the committee votes whether it wishes to report the measure to the full house. If a bill is tabled, then it is rejected. If amendments are extensive, sometimes a new bill with amendments built in will be submitted as a so-called “clean bill” with a new number. Generally, members who have been in Congress longer have greater seniority and therefore greater power.

U.S. House Committee

The House Financial Services Committee meets. Committee members sit in the tiers of raised chairs, while individuals testifying and audience members sit below.

A bill, that reaches the floor of the full house, can be simple or complex. It begins with an enacting formula such as “Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled. ” Consideration of a bill requires, itself, a rule which is a simple resolution specifying the particulars of debate—time limits, possibility of further amendments, and such. Each side has equal time and members can yield to other members who wish to speak. Sometimes opponents seek to recommit a bill, which means to change part of it. Generally, discussion requires a quorum, usually half of the total number of representatives, before discussion can begin, although there are exceptions. The house may debate and amend the bill. The precise procedure used by the House and Senate differs. A final vote on the bill follows.

Once a bill is approved by one house, it is sent to the other which may pass, reject, or amend it. For the bill to become law, both houses must agree to identical versions of the bill. If the second house amends the bill, then the differences between the two versions must be reconciled in a conference committee. This is an ad hoc committee that includes both senators and representatives and uses a reconciliation process to limit budget bills. Both Houses use a budget enforcement mechanism informally known as “pay-as-you-go” or “pay-go” which discourages members from considering acts which increase budget deficits. If both houses agree to the version reported by the conference committee, the bill passes, otherwise it fails.

The Constitution, however, requires a recorded vote if demanded by one-fifth of the members present. If the voice vote is unclear or if the matter is controversial, a recorded vote usually happens.

After passage by both houses, a bill is enrolled and sent to the president for approval. The president may sign it making it law. If the bill is vetoed, the president returns it to Congress with his objections. A vetoed bill can still become law if each house of Congress votes to override the veto with a two-thirds majority. However, if Congress is adjourned during this period, the president may veto legislation passed at the end of a congressional session simply by ignoring it. This maneuver is known as a pocket veto. It cannot be overridden by the adjourned Congress.

11.2: Organization of Congress

11.2.1: Party Leadership in the House

Party leaders and whips of the U.S. House of Representatives are elected by their respective parties in a closed-door caucus.

Learning Objective

Explain in detail the power of the Speaker of the House, the Majority Leader and the Party Whip

Key Points

- The current House Majority Leader is Republican Kevin McCarthy, while the current House Minority Leader is Democrat Nancy Pelosi. The current House Majority Whip is Republican Steve Scalise, while the current House Minority Whip is Democrat Steny Hover.

- The Majority Leader’s duties and prominence vary depending upon the style of the Speaker of the House and the political climate within the majority caucus.

- The Minority Leader of the House serves as floor leader of the opposition party and is the counterpart to the Majority Leader.

Key Terms

- Speaker of the House

-

the presiding officer (chair) of the House of Representatives

- minority leader

-

the floor leader of the second largest caucus in a legislative body; the leader of the opposition

- majority leader

-

a partisan position in a legislative body; often the chief spokesperson for the party in power, who sets the floor agenda and oversees the committee chairmen

Party leaders and whips of the United States House of Representatives are elected by their respective parties in a closed-door caucus by secret ballot. The party leaders are also known as floor leaders. The U.S. House of Representatives does not officially use the term “Minority Leader” although the media frequently does. Instead, the House uses the terms “Republican Leader” or “Democratic Leader” depending on which party holds a minority of seats.

The current House Majority Leader is Republican Kevin McCarthy, while the current House Minority Leader is Democrat Nancy Pelosi. The current House Majority Whip is Republican Steve Scales, while the current House Minority Whip is Democrat Steny Hoyer. The Majority Leader’s duties and prominence varies depending upon the style of the Speaker of the House and the political climate within the majority caucus.

House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy

The Speaker of the House and the Majority Leader

The House Majority Leader’s duties and prominence vary depending upon the style and power of the Speaker of the House. Typically, the Speaker does not participate in debate and rarely votes on the floor. In some cases, Majority Leaders have been more influential than the Speaker, notably Tom DeLay who was more prominent than Speaker Dennis Hastert. In addition, Speaker Newt Gingrich delegated to Dick Armey an unprecedented level of authority over scheduling legislation on the House floor. As presiding office of the House of Representatives, the Speaker holds a variety of powers over the House but usually delegates them to another member of the majority party.

The Speaker in the United States, by tradition, is the head of the majority party in the House of Representatives, outranking the Majority Leader. However, despite having the right to vote, the Speaker usually does not participate in debate and rarely votes. The Speaker is responsible for ensuring that the House passes legislation supported by the majority party. In pursuing this goal, the Speaker may use his or her power to determine when each bill reaches the floor. They also chair the majority party’s steering committee in the House. While the Speaker is the functioning head of the House majority party, the same is not true of the President pro tempore of the Senate, whose office is primarily ceremonial and honorary. The Speaker may designate any member of the House to act as Speaker pro tempore and preside over the House. During important debates, the Speaker pro tempore is ordinarily a senior member of the majority party who may be chosen for his or her skill in presiding. At other times, more junior members may be assigned to preside to give them experience with the rules and procedures of the House. The Speaker may also designate a Speaker pro tempore for special purposes, such as designating a Representative whose district is near Washington, DC to sign enrolled bills during long recesses.

The Minority Leader

The Minority Leader of the House serves as floor leader of the opposition party and is the counterpart to the Majority Leader. Unlike the Majority Leader, the Minority Leader is on the ballot for Speaker of the House when Congress convenes. If the Minority Leader’s party takes control of the House and the party officers are all re-elected to their seats, the Minority Leader is usually the party’s top choice for Speaker for the next Congress, while the Minority Whip is typically in line to become Majority Leader. The Minority Leader usually meets with the Majority Leader and the Speaker to discuss agreements on controversial issues.

The floor leaders and whips of each party are elected by their respective parties in a closed-door caucus by secret ballot. The Speaker-elect is also chosen in a closed-door session although they are formally installed in their position by a public vote when Congress reconvenes.

11.2.2: Party Leadership in the Senate

The party leadership of the Senate refers to the officials elected by the Senate Democratic Caucus and the Senate Republican Conference.

Learning Objective

Summarize the leadership structure in the Senate

Key Points

- Each party is led by a floor leader who directs the legislative agenda and is augmented by an Assistant Leader and several other officials who work together to manage the floor schedule of legislation, enforce party discipline, oversee efforts to elect new Senators, and maintain party unity.

- The titular, non-partisan leaders of the Senate itself are the Vice President of the United States, who serves as President of the Senate, and the President pro tempore, the most senior most member of the majority who theoretically presides in the absence of the Vice President.

- Unlike committee chairmanships, leadership positions are not traditionally conferred on the basis of seniority but are elected in closed-door caucuses.

Key Terms

- seniority

-

refers to the number of years one member of a group has been a part of the group, or the political power attained by position within the United States Government

- titular

-

One who holds a title.

- caucus

-

A meeting, especially a preliminary meeting, of persons belonging to a party, to nominate candidates for public office, or to select delegates to a nominating convention, or to confer regarding measures of party policy; a political primary meeting.

The party leadership of the United States Senate refers to the officials elected by the Senate Democratic Caucus and the Senate Republican Conference to manage the affairs of each party in the Senate. Each party is led by a floor leader who directs the legislative agenda of his caucus in the Senate, and who is augmented by an Assistant Leader or Whip, and several other officials who work together to manage the floor schedule of legislation, enforce party discipline, oversee efforts to elect new Senators, and maintain party unity.

The titular, non-partisan leaders of the Senate itself are the Vice President of the United States, who serves as President of the Senate, and the President pro tempore, the most senior member of the majority who theoretically presides in the absence of the Vice President.

Capitol Hill

Capitol Hill, where bills become laws.

Unlike committee chairmanships, leadership positions are not traditionally conferred on the basis of seniority, but are elected in closed-door caucuses.

Since January 3, 2007, the Democratic Party has constituted a majority in the Senate. The Senate Majority Leader is Harry Reid (Nevada) and serves as leader of the Senate Democratic Conference and manages the legislative business of the Senate. The Senate Majority Whip is Dick Durbin (Illinois) who manages votes, communicates with individual senators, and ensures passage of bills relevant to the agenda and policy goals of the Senate Democratic Conference. Since January 3, 2007, the Republican Party has constituted the minority of the Senate. Mitch McConnell (Kentucky) is the Senate Minority Leader and Jon Kyl (Arizona) is the Senate Minority Whip.

11.2.3: Bicameralism

Bicameralism is the practice of having two legislative or parliamentary chambers.

Learning Objective

Describe bicameralism and the Founding Fathers’ understanding of its role in American federalism

Key Points

- The Founding Fathers of the United States favored a bicameral legislature. The idea was to have the Senate be wealthier and wiser. The Senate was created to be a stabilizing force, elected not by mass electors, but selected by the State legislators.

- A conference committee is appointed when the two chambers cannot agree on the same wording of a proposal, and consists of a small number of legislators from each chamber. This tends to place much power in the hands of only a small number of legislators.

- State legislators chose the Senate and senators had to possess a significant amount of property in order to be deemed worthy and sensible enough for the position.

- As part of the Great Compromise, the Founding Fathers developed a form of bicameralism in which the upper house would have states represented equally, and the lower house would have them represented by population.

Key Terms

- Great Compromise

-

An agreement reached during the Constitutional Convention of 1787 that in part defined the legislative structure and representation that each state would have under the US Constitution. It called for a bicameral legislature, along with proportional representation in the lower house, but required the upper house to be weighted equally between the states.

- bicameral

-

Having, or pertaining to, two separate legislative chambers or houses.

Bicameralism

In government, bicameralism is the practice of having two legislative or parliamentary chambers comprise bills. Bicameralism is an essential and defining feature of the classical notion of mixed government. Bicameral legislatures tend to require a concurrent majority to pass legislation. A conference committee is appointed when the two chambers cannot agree on the same wording of a proposal that consists of a small number of legislators from each chamber. This tends to place much power in the hands of only a small number of legislators. Whatever legislation, if any, the conference committee finalizes must then be approved in an unamendable “take-it-or-leave-it” manner by both chambers.

The Founding Fathers of the United States favored a bicameral legislature. The idea was to have the Senate be wealthier and wiser. The Senate was created to be a stabilizing force, elected not by mass electors, but selected by the State legislators. Senators would be more knowledgeable and more deliberate—a sort of republican nobility—and a counter to what Madison saw as the “fickleness and passion” that could absorb the House.

Capitol Hill

The U.S. has a bicameral legislature in Congress, consisting of the House of Representatives and the Senate

State legislators chose the Senate and senators had to possess a significant amount of property in order to be deemed worthy and sensible enough for the position. In fact, it was not until the year 1913 that the Seventeenth Amendment was passed, which “mandated that Senators would be elected by popular vote rather than chosen by the State legislatures. ” As part of the Great Compromise, they invented a new rationale for bicameralism in which the upper house would have states represented equally, and the lower house would have them represented by population.

During the 1930s, the Legislature of the State of Nebraska was reduced from bicameral to unicameral with the 43 members that once comprised that state’s Senate. One of the arguments used to sell the idea at the time to Nebraska voters was that by adopting a unicameral system, the perceived evils of the conference committee process would be eliminated. During his term as Governor of Minnesota, Jesse Ventura proposed converting the Minnesotan legislature to a single chamber with proportional representation, as a reform that he felt would solve many legislative difficulties and impinge upon legislative corruption. Ventura argued that bicameral legislatures for provincial and local areas were excessive and unnecessary, and discussed unicameralism as a reform that could address many legislative and budgetary problems for states.

11.2.4: Legislative Agendas

An agenda is a list of meeting activities in the order in which they are to be taken up in the legislature.

Learning Objective

Differentiate between two uses of the word agenda

Key Points

- A political agenda is a set of issues and policies laid out by an executive or cabinet in government that tries to influence current and near-future political news and debate.

- In parliamentary procedure, an agenda is not binding upon an assembly unless its own rules make it so, or unless it has been adopted as the agenda for the meeting by majority vote at the start of the meeting.

- If an agenda is binding upon an assembly and a specific time is listed for an item, that item cannot be taken up before that time, and must be taken up when that time arrives even if other business is pending.

Key Terms

- town meeting

-

a form of direct democratic rule, used primarily in portions of the United States since the 17th century, in which most or all the members of a community come together to legislate policy and budgets for local government

- docket

-

A short entry of the proceedings of a court; the register containing them; the office containing the register.

- adjourn

-

Temporarily ending an event with intentions to complete it at another time or place.

An agenda is a list of meeting activities in the order in which they are to be taken up, by beginning with the call to order and ending with adjournment. It usually includes one or more specific items of business to be discussed. It may, but is not required to, include specific times for one or more activities. An agenda may also be called a “docket. “

A political agenda is a set of issues and policies laid out by an executive or cabinet in government that tries to influence current and near-future political news and debate. In parliamentary procedure, an agenda is not binding upon an assembly unless its own rules make it so or unless it has been adopted as the agenda for the meeting by majority vote at the start of the meeting. Otherwise, it is merely for the guidance of the chair.

If an agenda is binding upon an assembly, and a specific time is listed for an item. That item cannot be taken up before that time and must be taken up when that time arrives even if other business is pending. If it is desired to do otherwise, the rules can be suspended for that purpose.

Gerald Ford Papers

Gerald Ford set the Republican legislative agenda.

The political agenda while shaped by government can be influenced by grassroots support from party activists at events, such as a party conference, and can even be shaped by non-governmental activist groups which have a political aim. Increasingly, the mass media can have an effect in shaping the political agenda through its news coverage of news stories. A political party can be described as shaping the political agenda or setting the political agenda if its promotion of certain issues gains prominent news coverage. For example, at election time, if a political party wants to promote its polices and gain prominent news coverage in order to increase its support.

11.2.5: The Committee System

A congressional committee is a legislative sub-organization in Congress that handles a specific duty.

Learning Objective

Describe the committee system, its growth, and that growth’s effect on Congress’s power

Key Points

- Committees monitor on-going governmental operations, identify issues suitable for legislative review, gather and evaluate information and recommend courses of action to their parent body.

- Congressional committees provide invaluable informational services to Congress by investigating and reporting about specialized subjects.

- Since 1761, the growing autonomy of committees has fragmented the power of each congressional chamber as a unit. This centrifugal dispersion of power has, without doubt, weakened the Legislative Branch relative to the other branches of the federal government.

- Today the Senate operates with 20 standing and select committees. These select committees, however, are permanent in nature and are treated as standing committees under Senate rules.

Key Term

- Ways and Means

-

The Committee of Ways and Means is the chief tax-writing committee of the United States House of Representatives

A congressional committee is a legislative sub-organization in the U.S. Congress that handles a specific duty. Committee membership enables members to develop specialized knowledge of the matters under their jurisdiction. Committees monitor on-going governmental operations, identify issues suitable for legislative review, gather and evaluate information and recommend courses of action to their parent body. It is neither expected nor possible that a member of Congress be an expert on all matters and subject areas that come before Congress. Congressional committees provide invaluable informational services to Congress by investigating and reporting about specialized subjects.

Most legislation is considered by standing committees which have jurisdiction over a particular subject such as Agriculture or Appropriations. The House has twenty standing committees; the Senate has sixteen. Standing committees meet at least once each month. Almost all standing committee meetings for transacting business must be open to the public unless the committee votes, publicly, to close the meeting. A committee might call for public hearings on important bills. Each committee is led by a chair who belongs to the majority party and a ranking member of the minority party. Witnesses and experts can present their case for or against a bill. Then, a bill may go to what’s called a mark-up session where committee members debate the bill’s merits and may offer amendments or revisions. Committees may also amend the bill, but the full house holds the power to accept or reject committee amendments. After debate, the committee votes whether it wishes to report the measure to the full house. If a bill is tabled then it is rejected. If amendments are extensive, sometimes a new bill with amendments built in will be submitted as a so-called clean bill with a new number.

Congress divides its legislative, oversight, and internal administrative tasks among approximately 200 committees and subcommittees. Within assigned areas, these functional subunits gather information, compare and evaluate legislative alternatives, identify policy problems and propose solutions, select, determine, and report measures for full chamber consideration, monitor executive branch performance and investigate allegations of wrongdoing. While this investigatory function is important, procedures such as the House discharge petition process are so difficult to implement that committee jurisdiction over particular subject matter of bills has expanded into semi-autonomous power.

Since 1761, the growing autonomy of committees has fragmented the power of each congressional chamber as a unit. Over time, this system proved ineffective, so in 1816 the Senate adopted a formal system of 11 standing committees with five members each. With the advent of this new system, committees are able to handle long-term studies and investigations, in addition to regular legislative duties. With the growing responsibilities of the Senate, the committees gradually grew to be the key policy-making bodies of the Senate, instead of merely technical aids to the chamber.

By 1906, the Senate maintained 66 standing and select committees—eight more committees than members of the majority party. The large number of committees and the manner of assigning their chairmanships suggests that many of them existed solely to provide office space in those days before the Senate acquired its first permanent office building, the Russell Senate Office Building. By May 27, 1920, the Russell Senate Office Building had opened, and with all Senate members assigned private office space, the Senate quietly abolished 42 committees. Today the Senate operates with 20 standing and select committees. These select committees, however, are permanent in nature and are treated as standing committees under Senate rules.

Russell Senate Office Building

The Russell Senate Office Building houses several Congressional staff members, including those on the United States Senate Committees on Armed Services, Rules and Administration, Veterans’ Affairs, and others.

The first House Committee was appointed on April 2, 1789 to prepare and report such standing rules and orders of proceeding as well as the duties of a Sergeant-at-Arms to enforce those rules. Other committees were created as needed, on a temporary basis, to review specific issues for the full House. The House relied primarily on the Committee of the Whole to handle the bulk of legislative issues. The Committee on Ways and Means followed on July 24, 1789 during a debate on the creation of the Treasury Department over concerns of giving the new department too much authority over revenue proposals. The House felt it would be better equipped if it established a committee to handle the matter. This first Committee on Ways and Means had 11 members and existed for just two months. It later became a standing committee in 1801, a position it still holds today.

Ways and Means Committee Logo

The Ways and Means Committee has been an important committee in the U.S. since 1789

11.2.6: The Staff System

Congressional staff are employees of the United States Congress or individual members of Congress.

Learning Objective

Differentiate between the roles of different congressional staff; in the Congressional Research Service, Congressional Budget Office, and Government Accountability Office

Key Points

- In the year 2000, there were approximately 11,692 personal staff, 2,492 committee staff, 274 leadership staff, 5,034 institutional staff, 3,500 GAO employees, 747 CRS employees, and 232 CBO employees.

- Every Representative hired 14 staff members, while the average Senator hired 34. In 2000, Representatives had a limit of 18 full-time and four part-time staffers, while Senators had no limit on staff.

- Majority and minority members hire their own staff except for two committees in each house: the Committee on Standards of Official Conduct and the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence in the House, and the Select Committee on Ethics and Senate Select Committee on Intelligence in the Senate.

Key Terms

- Congressional Research Service

-

The Congressional Research Service (CRS), known as Congress’s think tank, is a public policy research arm of the United States Congress.

- Congressional Budget Office

-

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is a federal agency within the legislative branch of the United States government that provides economic data to Congress.

- Government Accountability Office

-

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) is the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of the United States Congress.

- appropriation

-

Public funds set aside for a specific purpose.

Congressional staff are employees of the United States Congress or individual members of Congress. The various types of congressional staff are as follows: personal staff, who work for individual members of Congress; committee staff, who serve either the majority or minority on congressional committees; leadership staff, who work for the speaker, majority and minority leaders, and the majority and minority whips; institutional staff, who include the majority and minority party floor staff and non-partisan staff; and the support agency staff, who are the non-partisan employees of the Congressional Research Service (CRS), Congressional Budget Office (CBO), and Government Accountability Office (GAO).

Russell Senate Office Building

The Russell Senate Office Building houses several Congressional staff members, including those on the United States Senate Committees on Armed Services, Rules and Administration, Veterans’ Affairs, and others.

In the year 2000, there were approximately 11,692 personal staff, 2,492 committee staff, 274 leadership staff, 5,034 institutional staff, 747 CRS employees, and 232 CBO employees, and 3,500 GAO employees. Every Representative hired 14 staff members, while the average Senator hired 34. Representatives had a limit of 18 full-time and four part-time staffers, while Senators had no limit on staff.

Each congressional committee has a staff of varying size. Appropriations for committee staff are made in annual legislative appropriations bills. Majority and minority members hire their own staff, with the exception of two committees in each house: the Committee on Standards of Official Conduct and the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence in the House, and the Select Committee on Ethics and the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence in the Senate. These committees have a single staff.

In 2000, House committees had an average of 68 staff, and Senate committees an average of 46. Committee staff includes staff directors, committee counsel, committee investigators, press secretaries, chief clerks and office managers, schedulers, documents clerks, and assistants.

11.2.7: The Caucus

A caucus is a meeting of supporters or members of a political party or movement.

Learning Objective

Differentiate between two different types of political caucus

Key Points