Learning Objectives

- Describe how adaptive learning principles and procedures are used in applied behavior analysis (ABA) to treat behavioral excesses and deficits

- Describe the research findings that lead to Seligman’s learned helplessness model of depression

- Describe cognitive behavioral treatment ofmajor depressive disorder

- Describe Marlatt’s findings regarding the likelihood and causes of relapse in addictive disorders

- Describe how multi-systemic interventions applied in the home, school, and community have been used to treat conduct disorder

The Scientist Practitioner Model of Professional Psychology

The most valuable natural resource on the planet earth is not diamonds, gold, or energy; it is the potential of every human being to understand and impact upon nature. Development of this potential resulted in the discovery of diamonds, gold, fossil fuels, and nuclear energy; it resulted in the transformation of Manhattan and much of the rest of the earth since the Scientific Revolution. Development of this potential resulted in the beauty and creativity intrinsic to architecture, music, and the arts. Development of this potential resulted in what we know as civilization.

Over the past 11 chapters, we described how the science of psychology helps us understand the many different ways that experience interacts with our genes to influence our thoughts, emotions, and actions. As humans acquired new knowledge and skills, we altered our environment; as we altered our environment, it became necessary to develop new knowledge and skills. Permanently recording human progress sped up the transformation from the Stone Age to the Information Age (Kurzweil, 2001). Humans are at an unprecedented point in time. Application of the scientific method to understanding nature is a two-edged sword. This knowledge and technological capability has enabled humans to extend our reach beyond our planet. At the same time this capability is threatening our very survival on earth. We need to insure that we continue to eat, survive, and reproduce. Otherwise, it will not matter what we think it is all about!

Often, we contrasted the adaptive requirements of the Stone Age with our current human-constructed conditions. The still existing indigenous tribes often have elders believed to have special powers or knowledge to help those suffering from physical or behavioral problems. As a science, psychology has progressed in the accumulation of knowledge and technology since its beginnings in Wundt’s lab. In the previous chapter, we saw how the profession of clinical psychology uses empirically-validated learning-based procedures to successfully ameliorate severe psychiatric and psychological disorders. In the rainforest, parents, relatives, and band members are responsible for raising children to execute their culturally defined roles. In this chapter, we will examine other examples of the application of professional psychology to assist individuals in adapting to their roles within our complex, technologically-enhanced, cultural institutions.

Academic and Research Psychology

College professors in all disciplines conduct scholarly research in their areas of specialization. Empirical research provides the foundation of the scientist-practitioner model of professional psychology. This model emphasizes the complementary connection between basic and applied research and professional practice. We have seen that if the requirements of internal and external validity are satisfied, it is possible to come to cause-effect conclusions regarding the effectiveness of specific therapeutic procedures in modifying specific behavioral problems. Ethical practice requires remaining current and basing one’s clinical strategy on the results of such research. Throughout this book, we have described the findings and implications of correlational and experimental research conducted in the laboratory and field. Most of the individuals carrying out that research are academic and research psychology faculty members possessing doctoral degrees in departments of Psychology and related disciplines (e.g., Cognitive Science, Human Development, Neuroscience, etc.). Much of the research relates to the basic psychological processes described in Chapters 2 through 7 (biological psychology, perception, motivation, learning, and cognition). Other research relates to the holistic issues involved in normal and problematic human personality and social development described in Chapters 8 through 11.

Prior to the Second World War, psychology was almost exclusively an academic discipline with a small number of practitioners. During and after the war, psychiatrists requested help from psychologists in providing treatment for soldiers. The government funded the development of clinical psychology programs to meet this increased demand for services. It became necessary to develop a standardized curriculum to train psychological practitioners (Frank, 1984). In 1949, a conference was held at the University of Colorado at Boulder to achieve this objective (Baker & Benjamin, 2000). A scientist-practitioner model was adopted for American Psychological Association accreditation in clinical psychology. The rationale was that in the same way that medical practice is based upon research findings from the biological sciences, clinical practice should be based upon findings from the content areas of psychology. After the Second World War, significant changes occurred in another APA division beside clinical psychology. In 1951, the name of the Division of Personnel and Guidance Psychologists was changed to the Division of Counseling Psychology. This change reflected the fact that individuals in this division often worked side-by-side with clinical psychologists on other lifestyle issues beside those related to work.

Although it was not an objective at the time, this grounding in the scientific method was an important first step in the development of the movement to evidence-based practice four decades later. Grounding clinical practice in psychological science was also key to the development of alternatives to the then (by default) prevalent psychodynamic therapeutic model. The Freudian model assumed that psychiatric disorders stemmed from unconscious conflict between impulsive demands of the id and the moral standards of the superego (see Chapter 8). The model postulated the existence of defense mechanisms, such as repression, that prevented the sources of conflict from becoming conscious. Assessment and treatment techniques flowed from this model; it was necessary to circumvent the defense mechanisms in order to bring the sources of conflict to consciousness. The logic of assessment instruments such as the Rorshach inkblots and Thematic Apperception Test was that due to their ambiguity, they would not activate defense mechanisms, thereby enabling individuals to “project” their unconscious thoughts onto the inkblots or pictures.

The reliability of scoring for the Rorshach inkblots has been questioned (Lillenfeld, Wood, & Garb, 2000) and their use challenged in court cases (Gacono & Evans, 2008; Gacono, Evans, & Viglione, 2002). After an enormously influential review of case studies addressing the effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy, it was concluded that they provided no benefit beyond the passage of time (Eysenck, 1952). The time was right after the Second World War to develop an alternative, science-based approach to psychodynamic psychotherapy. This void was filled by learning-principle based behavior modification, applied behavior analysis, and cognitive-behavior modification interventions (Martin & Pear, 2011, chapter 29). Detailed applications of these approaches will be described below.

Contemporary professional psychologists implement evidence-based psychological procedures to assist individuals in developing their potential. Before we consider applications in schools and at the workplace, we will consider those individuals challenged by serious issues. In the prior chapter, applied behavior analysis and cognitive-behavioral procedures were frequently cited as being effective for treating DSM diagnosed psychiatric disorders. We will now provide more detailed descriptions for these procedures and how they are applied.

A Psychological Model of Maladaptive Behavior

DSM disorder labels still constitute the most used terminology for describing behavioral disorders. As we saw in the last chapter, a DSM diagnosis may provide useful information regarding the likely prognosis for behavioral change in the absence of treatment. However, DSM diagnosis provides minimal information regarding specific interventions for specific thoughts, feelings, or behaviors. Despite this, DSM disorder terms are frequently misunderstood as pseudo-explanations in a way which is not usually characteristic of other non-explanatory illness terms. For example, one is unlikely to conclude that high blood pressure readings are caused by hypertension; in comparison, it is common to conclude that hallucinations are caused by schizophrenia. This problem has led some psychologists to suggest an entirely different approach to describing behavioral disorders. Rather than attempting to identify an underlying “mental illness” (e.g., Autism Spectrum Disorder, Major Depressive Disorder, etc.), the behavior itself is considered the target for treatment. Rather than providing DSM diagnoses for different disorders, problematic behavior is categorized according to the following listing:

- Behavioral Excesses (e.g., head-banging, repetitive hand movements, crying, etc.)

- Behavioral Deficits (e.g., lack of speech, failure to imitate, failure to get out of bed in the morning, etc.)

- Inappropriate External Stimulus Control (e.g., speaking out loud at the library, not paying attention to “Stop” signs, etc.)

- Inappropriate Internal Stimulus Control (e.g., thinking that one is a failure, not thinking of someone else’s needs, etc.)

- Inappropriate Reinforcement (e.g., problem drinking, not caring about performance in school, etc.)

One’s thoughts, emotions, or behaviors are maladaptive when they interfere with or prevent achieving personal objectives. A psychological model of maladaptive behavior avoids the issues of pseudo-explanation, reliability, and validity that plague DSM diagnoses. There is no disease to be determined or considered an explanation. Diagnosis consists of a detailed description of the individual’s behaviors and environmental circumstances. Psychologists explain such disorders as resulting from nature/nurture interactions and rely upon experiential treatment approaches (e.g., talking therapies and homework assignments). An underlying assumption is that no matter what the “cause” of maladaptive behavior, it can usually be modified by providing appropriate learning experiences. Assessment of the effectiveness of treatment is based on objective measures of improved adaptation to specific environmental conditions (e.g., performance in school, job performance, interpersonal relations, etc.).

Let us take the example of Major Depressive Disorder. The medical model dictates assessing the extent to which an individual’s symptoms fulfill the requirement of a DSM-5 diagnosis. Different individuals vary, however, in terms of the patterns of their depressed behaviors. Some may not get out of bed in the morning; others might. Some might groom and dress themselves; others not. Some might cry a lot; others not; some may be lethargic; others not. Some may no longer enjoy their hobbies; others might. Some may no longer perform adequately on their jobs; others might; and so on. Given the infinite combination of possibilities, it is not surprising that arriving at a DSM diagnosis requires a good deal of interpretation and prioritization by the psychiatrist. Reliability issues are inevitable. In contrast, the psychological assessment model results in a detailed behavioral and environmental description tailored to each individual. One would not expect differences in interpretation of whether or not someone gets out of bed in the morning, grooms and dresses themselves, cries, etc. It is clear that these behavioral descriptions are defined exclusively on the behavioral (dependent variable) side. No one would make the mistake of concluding that a person fails to get out of bed because they fail to get out of bed; this is obviously circular. A DSM diagnosis, however, is seductive. It is tempting to conclude that the person fails to get out of bed as the result of major depressive disorder. We will now see how a psychological model can be applied to help non-verbal individuals with direct learning-based interventions. This will be followed by an application of the model to verbal individuals using indirect-learning procedures.

Treating Behavioral Problems with Non-Verbal Individuals:

Applied Behavior Analysis with Autistic Children

Autism is a severe developmental disorder. It is characterized by an apparent lack of interest in other people, including parents and siblings. A behavioral excess such as head banging, not only is likely to result in serious injury, but will interfere with a child’s acquiring important linguistic and social skills. That is, an extreme behavioral excess may result in serious behavioral deficits. Autistic children often display excesses and/or deficits of attention. For example, they may stare at the same object for an entire day (stimulus over-selectivity) or seem unable to focus upon anything for more than a few seconds (stimulus under-selectivity). In the absence of treatment, an autistic child may fail to acquire the most basic self-help skills such as dressing or feeding oneself, or looking before crossing the street. They require constant attention from care-givers in order to survive, let alone to acquire the social and intellectual skills requisite to making friends and preparing for school.

The principles of direct learning described in Chapter 5 were predominantly established under controlled conditions with non-verbal animals. It should therefore come as no surprise that procedures based upon these principles have been applied to non-verbal children diagnosed with neurodevelopmental disorders. Ivar Lovaas (1967) pioneered the development and implementation of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) as a comprehensive learning program for autistic children. In the absence of effective biological treatment approaches, ABA continues to be the treatment of choice for individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. An excellent summary of this early work (Lovaas & Newsom, 1976) describes his success in reducing self-destructive behavior (e.g., head-banging) and teaching language using control learning procedures. Reinforcement Therapy, a still inspiring film (Lovaas, 1969), portrays this seminal research.

In Lovaas’s words, “What one usually sees when first meeting an autistic child who is 2, 3, or even 10 years of age is a child who has all the external physical characteristics of a normal child – that is, he has hair, and he has eyes and a nose, and he may be dressed in a shirt and trousers – but who really has no behaviors that one can single out as distinctively “human.” The major job then for a therapist – whether he’s behaviorally oriented or not – would seem to be a very intriguing one, namely the creation or construction of a truly human behavioral repertoire where none exists” (Lovaas & Newsom, 1976, p. 310). Since they are non-verbal and do not imitate, teaching an autistic child can have much in common with training a laboratory animal in a Skinner-box. Initially, one needs to rely on direct learning procedures. Unconditioned reinforcers and punishers (i.e., biologically significant stimuli such as food or shock) serve as consequences for arbitrary (to the child) behaviors.

Behavioral Excesses – Eliminating Self-Injurious Behavior

Some early attempts at eliminating self-injurious behaviors by withdrawing attention (Wolf, Risley, & Mees, 1964) or placing the child in social isolation (Hamilton, Stephens, & Allen, 1967) were successful. However, such procedures tend to be slow-acting and risky in extreme cases. In such instances, presentation of an aversive stimulus (a brief mild shock) may be necessary. Lovaas, Schaeffer, and Simmons (1965) were the first to demonstrate the immediate long-lasting suppressive effect of contingent shock on tantrums and self-destructive acts with two 5-year-old children. These findings have been frequently replicated using a device known as the SIBIS (Self-Injurious Behavior Inhibiting System). The SIBIS was developed through collaboration between psychological researchers, engineers, autism advocates, and medical manufacturers. A sensor module that straps onto the head is attached to a radio transmitter. The sensor can be adjusted for different intensities of impact and contingent shock can immediately be delivered to the arm or leg. Rapid substantial reductions in self-injurious behavior were obtained with five previously untreatable older children and young adults using brief mild shocks (Linscheid, Iwata, Ricketts, Williams, & Griffin, 1990).

Behavioral Deficits – Establishing Imitation and Speech

Once interfering behavioral excesses are reduced to being manageable, it is possible to address behavioral deficits and establish the capability of indirect learning through imitation and language. Perhaps the most disheartening aspect of working with an autistic child is her/his indifference to signs of affection. Smiles, coos, hugs, and kisses are often ignored or rejected. Autistic children are typically physically healthy and good eaters. Therefore, Lovaas and his co-workers were able to work at meal time, making food contingent on specific behaviors. A shaping procedure including prompting and fading was used at first to teach the child to emit different sounds. For example, in teaching the child to say “mama”, the teacher would hold the child’s lips closed and then let go when the child tried to vocalize. This would result in the initial “mmm” (You can try this on yourself). Once this was achieved, the teacher would touch the child’s lips without holding them shut, asking him/her to say “mmm.” Eventually the physical prompt could be eliminated and the verbal prompt would be sufficient. At this point one would ask the child to say “ma”, holding the child’s lips closed while he/she is saying “mmm” and suddenly letting go. This will result in an approximation of “ma” that can be refined on subsequent trials. Repeating “ma”, produces the desired “mama.” With additional examples, the child gradually acquires the ability to imitate different sounds and words and the pace of learning picks up considerably.

Once the child is able to imitate what she/he hears, procedures are implemented to teach meaningful speech. Predictive learning procedures are used in which words are paired with the objects they represent, resulting in verbal comprehension. Verbal expression is achieved by rewarding the child for pointing to objects and saying their name. The child is taught to ask questions (e.g., “Is this a book?”) and make requests (e.g., “May I have ice cream?”). After a vocabulary of nouns is established, the child learns about relationships among objects (e.g., “on top of”, “inside of”, etc.) and other parts of speech are taught (e.g., pronouns, adjectives, etc.). Eventually the child becomes capable of describing his/her life (e.g., “What did you have for breakfast?”) and creative storytelling.

Lovaas assessed the extent to which the treatment gains acquired in his program were maintained over a 4-year follow-up in other environments. If the children were discharged to a state institution, they lost the benefit of training. Self-injurious behavior, language, and social skills all returned to pre-treatment levels. Fortunately, providing “booster” sessions rapidly reinstated the treatment gains. Those children remaining with their parents (who received instruction in the basic procedures) maintained their treatment gains and continued to improve in some instances (Lovaas, Koegel, Simmons, & Long, 1973). An intellectual development disorder often accompanies autism, so it is unrealistic to aspire to the age-appropriate grade level for all children. Still, Lovaas (1987) has achieved this impressive ideal with 50 percent of the children started prior to 30 months of age.

Treating Behavioral Problems with Verbal Individuals: Cognitive Behavior Therapy

It is clear how the Applied Behavior Analysis procedures used with non-verbal individuals such as autistic children flow directly from Skinnerian reinforcement and punishment procedures developed with non-speaking animals. Less obvious is how cognitive behavior modification talking therapies relate to the psychology research literature. Their origin can be traced to two books published for the general population a year apart by Albert Ellis: A Guide to Rational Living (1961) and Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy (1962). Ellis was trained in the Freudian psychodynamic approach to psychotherapy and became dissatisfied with the results obtained with his patients. At best, progress was very slow and often did not occur at all. He attributed these poor results to emphasis upon the past rather than the present and a passive/non-directive as opposed to a more active/directive approach he defined as Rational Emotive Therapy (RET). RET assumed that an individual’s emotional and behavioral reactions to an event resulted from interpretation. For example, if you were walking along a sidewalk and someone bumped into you, you might react with anger until discovering that the person was blind. Ellis developed a systematic approach to therapy based on identifying one’s irrational thoughts and countering them with more adaptive alternatives.

Part of the reason for not connecting Ellis’ verbal approach to psychotherapy with the animal literature is the failure to connect that literature with speech by making the distinction between direct and indirect learning. As described in chapters 5 and 6, word meaning is established through Pavlovian classical conditioning procedures and speech is maintained by its consequences (i.e., may be understood as an operant). Martin Seligman (1975) developed a learned helplessness animal model providing the underpinnings of a cognitive analysis of depression and the psychiatrist Aaron Beck conducted experimental clinical trials comparing the efficacy of cognitive and pharmacologic approaches to the treatment of depression.

Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Depression

One might think that if it is possible to socialize an autistic child with extreme behavioral excesses and severely limiting behavioral deficits, treating a healthy verbal cooperative adult for a psychological problem would be easy in comparison. However, we need to appreciate the logistic and treatment implementation issues that arise when working with a free-living individual. Lovaas was able to create a highly controlled environment during the children’s waking hours. It was possible for trained professionals to closely monitor the children’s behavior and immediately provide powerful consequences. In comparison, adult treatment typically consists of weekly 1-hour “talking sessions” and “homework” assignments where the therapist does not have this degree of access or control. Success depends upon the client following through on suggested actions and accurately reporting what transpires.

Learned Helplessness

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change; courage to change the things I can; and wisdom to know the difference.

The Serenity Prayer, attributed to Friedrich Oetinger (1702-1782) and Reinhold Niebuhr (1892-1971)

From an adaptive learning perspective, there is much wisdom in the serenity prayer. In our continual quest to survive and to thrive, there are physical, behavioral, educational, cultural, economic, political, and other situational factors limiting our options. Research findings suggest that the inability to affect outcomes can have detrimental effects.

In Seligman’s initial research study, dogs were initially placed in a restraining harness with a panel in front of them. One group did not receive shock. A second group received an escape learning contingency in which pressing the panel turned off the shock. A third group was “yoked” to the second group and received inescapable shock. That is, subjects received shock at precisely the same time but could do nothing to control its occurrence. In the second phase, subjects were placed in a shuttle box where they could escape shock by jumping over a hurdle from one side to the other. Dogs not receiving shock or exposed to escapable shock failed to escape on only 10 percent of the trials whereas those exposed to inescapable shock failed to escape on over 50 percent of the trials. Seligman observed that many of these dogs displayed symptoms similar to those characteristic of depressed humans including lethargy, crying, and loss of appetite. Based upon his findings and observations, Seligman formulated a very influential “learned helplessness” model of clinical depression. He suggested that events such as loss of a loved one or losing a job could result in failure to take appropriate action in non-related circumstances as well as development of depressive symptoms. In entertaining and engaging books, Seligman describes how his learned helplessness model helps us understand the etiology (i.e., cause), treatment (Seligman, Maier, and Geer, 1968), and prevention of depression (Seligman, 1975; 1990).

The key factor in the learned helplessness phenomenon is prior exposure to uncontrollable events. Goodkin (1976) demonstrated that prior exposure to uncontrolled food presentations would produce similar detrimental effects to uncontrolled shock presentations on the acquisition of an escape response. The “spoiling” effect with appetitive events has also been demonstrated under laboratory conditions using the learned helplessness model. Pigeons exposed to non-contingent delivery of food were slower to acquire a key pecking response and demonstrated a lower rate of key pecking once it was acquired (Wasserman & Molina, 1975). It is clear from these studies and others that the serenity proverb applies to other animals as well as humans. Successful adaptation requires learning when one does and does not have the ability to control environmental events.

As an example, let us consider someone who becomes depressed after losing a job. Seligman’s learned helplessness research suggests that depression results from a perceived loss of control over significant events. It is as though the person believes “If I do this, it will not matter.” Depression in humans has been related to attributions on three dimensions: internal-external, stable-unstable, and global-specific (Abramson, Seligman, and Teasdale, 1978). With respect to our example, the person is more likely to become depressed if he/she attributes loss of the job to: a personal deficiency such as not being smart (internal) rather than to a downturn in the economy (external); the belief that not being smart is a permanent deficiency (stable) rather than temporary (unstable); and that not being smart will apply to other jobs (global) rather than just the previous one (specific).

Cognitive-behavior therapy for depression would include attempts by the therapist to modify these attributions during therapeutic sessions as well as providing reality-testing exercises as homework assignments. The therapist might challenge the notion that the person is not smart by asking them to recall past job performance successes. They could review the person’s credentials in preparation for a job search. Severe cases of depression might require assignments related to self-care and “small-step” achievements (e.g., making one’s bed, grooming and getting dressed, going out for a walk, etc.). As mentioned previously, homework assignments constitute an essential component of cognitive-behavioral treatment of depression (Jacobson, Dobson, Truax, Addis, Koerner, Gollan, Gortner, & Prince, 1996). Apparently, therapies are effective to the extent that they result in clients experiencing the consequences of their acts under naturalistic circumstances. This finding is consistent with an adaptive learning model of the psychotherapeutic process. That is, therapy is designed to help the individual acquire the necessary skills to cope with their idiosyncratic environmental demands.

Frequently the therapeutic process consists of determining adaptive rules specifying a contingency between a specific behavior and specific consequence. For example, in treating a severely depressed individual, one might start with “If you get out of bed within 30 minutes after the alarm goes off, you can reward yourself with 30 minutes of TV.” This can then be modified to require getting up within 20 minutes, 10 minutes, and 5 minutes. Once this is accomplished, the person may be required to get up and make their bed, get dressed and wash their face, etc. If the person is not severely depressed, it may be sufficient to establish rules such as “After finding appropriate positions in the newspaper and submitting your resume, you can reward yourself with reading your favorite section of the paper.”

Preventing Behavioral Problems and Realizing Human Potential

Relapse Prevention

As indicated in our summaries of the treatment results for DSM disorders last chapter, in several instances (e.g., autism, depression, addictive disorders, etc.) successful results were not maintained. This is often the result of issues other than the failure to generalize beyond the training environment(s). In Chapter 5, we saw that the extinction process does not “undo” prior learning. Rather, an inhibitory response is acquired that counteracts the previously learned behavior. Adaptive learning procedures have been successful in addressing a wide range of behavioral problems. Successful treatments rely upon the establishment of new behaviors to counteract behavioral excesses and eliminate behavioral deficits. Unfortunately, successful treatment may still be subject to relapse. G. Alan Marlatt has published extensively on the conditions likely to result in relapse and developed a strategy for reducing the risk (Marlatt, 1978; Marlatt & Gordon, 1980, 1985; Brownell, Marlatt, Lichtenstein, & Wilson, 1986; Marlatt & Donovan, 2005). Much of this research relates to addictive disorders that have been shown to undergo remarkably similar relapse patterns. Unless provided with additional training, 70 percent of successfully treated smokers, excessive drinkers, and heroin addicts are likely to relapse within six months (Hunt, Arnett, & Branch, 1971). Marlatt conducted follow-up interviews to track the incidence of relapses and attain information regarding the circumstances (e.g., time of day, activity, location, presence of others, associated thoughts and feelings). Approximately 75 percent of the relapses were precipitated by negative emotional states (e.g., frustration, anger, anxiety, depression), social pressure, and interpersonal conflict (e.g., with spouse, family member, friend, employer/employee). Marlatt also described the “abstinence violation effect” in which a minor lapse was followed by a full-blown binge.

Relapse prevention methods involve identifying personal high-risk situations, acquiring, and practicing coping skills. For example, depending upon one’s environmental demands, any combination of the following treatments may be appropriate: relaxation exercises; desensitization for specific fears or sources of anxiety; anger management; time management; assertiveness training; social-skills training; conflict resolution training; training in self-assessment and self-control. A review of research applying relapse prevention methods to difficult recalcitrant substance abuse problems concluded that it was quite successful (Irvin, Bowers, Dunn, & Wang, 1999). It is likely that targeted use of such procedures (e.g., assertiveness training to resist the effects of peer pressure) would improve upon the effectiveness of MST with conduct disorder.

An adaptive learning perspective requires an extensive analysis of an individual’s environmental demands and coping strategies. Whether in the home, the school, or a free-living environment, there may be a mismatch between the demands and the person’s current skill set. Successful treatment provides the necessary skills to not only cope with the current demands, but also to prepare the individual for predictable stressors and setbacks.

Binge drinking and excessive alcohol consumption pose substantial health risks and negatively impact upon class attendance and the academic performance of college students (https://www.alcohol.org/teens/college-campuses/). Based upon his extensive research addressing substance-abuse interventions and relapse prevention, Marlatt developed a comprehensive assessment and intervention program called Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A Harm Reduction Approach (Denerin & Spear, 2012; Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1998; Marlatt, 1996; Marlatt, Baer, & Larimer, 1995). The program consists of two 1-hour interviews presented in an empathic, non-judgmental manner. The first interview is followed by an on-line assessment survey designed to enable the prescription of specific behavioral recommendations based on each student’s responses. In order to reduce the likelihood of relapse, the program provides information and develops skills to counter peer pressure, negative emotions, and other triggers for excessive and binge drinking. A review of randomized controlled trials concluded that the BASICS program resulted in a significant reduction of approximately two drinks per week in college students (Fachini, Aliane, Martinez, & Furtado, 2012).

Prevention of Maladaptive Behavior

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure

The Early Riser

The current state of the art in treating conduct disorder appears to be a long-term recidivism rate of 50%. Hopefully, implementation of relapse prevention techniques and forthcoming research will enable us to improve upon this result. Ideally, we would be able to prevent the problematic behavioral excesses and deficits which comprise the disorder from developing in the first place. The Early Risers “Skills for Success” Conduct Problems Prevention Program attempted to achieve this by working with kindergarten children exhibiting high incidences of aggression (August, Realmuto, Hektner, & Bloomquist, 2001). Similar to MST, Early Risers (ER) focuses upon parent training, peer relations, and school performance: parents are instructed in effective disciplining techniques; children meet with “friendship groups” on a weekly basis during the school year and during a six-week summer session; and a family advocate will work with parents on their child’s academic needs with an emphasis on reading. A 10-year follow-up of the results for high-risk children receiving three intensive years of ER training followed by two booster years found fewer symptoms of conduct, oppositional defiant, or major depressive disorders than a randomized control condition. Behavioral and academic improvements were evident in the ER condition as early as the first two years, even for the most aggressive children. The authors concluded that the Early Risers program was effective in interrupting the “maladaptive developmental cascade” in which aggressive children “turn off” parents, peers, and teachers, resulting in a spiraling down of social and academic performance (Hektner, August, Bloomquist, Lee, & Klimes-Dougan, 2014).

The Good Behavior Game

Children arrive at school with different levels of preparedness and skills. This often results in classroom management challenges for the teacher. Many different adaptive learning procedures have been implemented successfully to address such problems. The Good Behavior Game (GBG) is a comprehensive program recommended by the Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy (www.evidencebasedprograms.org), a member of the Council for Excellence in Government. The GBG was developed by two teachers and Montrose Wolf (Barrish, Saunders, & Wolf, 1969), one of the founders of the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, a very readable and practical publication. In order to play the game, the teacher divides the class into two or three teams of students (it has been implemented as early as pre-school). The GBG is usually introduced for 10-minute sessions, 3 days a week. Gradually, the session times are increased to a maximum of an hour. A chart is posted in front of the room listing and providing concrete examples of inappropriate behaviors such as leaving one’s seat, talking out, or causing disruptions. Any instance of such a behavior is described by the teacher (e.g., “Team 1 gets a check because Mary just talked out without raising her hand”) and a check mark is placed on the chart under the team’s name. The teacher also praises the other groups for behaving (e.g., “Teams 2 and 3 are working very nicely”). At the end of the day, the members of the team with the fewest check marks receive school-related rewards such as free time, lining up first for lunch, or stars on a “winner’s chart. Usually, it is possible for all groups to receive rewards if they remain below a specified number of inappropriate behaviors. This number may then be reduced over sessions.

The Good Behavior Game has been tested in two major randomized controlled studies in an urban environment. It was demonstrated to reduce aggression (Dolan, Kellam, Brown, Werthamer-Larson, Rebok, & Mayer, 1993) and increase on-task behavior (Brown, 1993) in 1st-graders, and reduce aggression (Kellam, Rebok, Ialongo, & Mayer, 1994) and the initiation of smoking (Kellam & Anthony (1998) in middle school students. A follow-up after the 6th-grade, found that students experiencing the GBG in the 1st-grade had a 60% lower incidence of conduct disorder, 35% lower likelihood of suspension, and 29% lower likelihood of requiring mental health services. Perhaps most impressively, 14 years after implementation, the GBG was found to result in a 50% lower rate of lifetime illicit drug abuse, a 59% lower likelihood of smoking 10 or more cigarettes a day, and a 35% lower rate of lifetime alcohol abuse for 19-21 year-old males (Kellam, Brown, Poduska, Ialongo, Petras, Wang, Toyinbo, Wilcox, Ford, & Windham, 2008)! The GBG has been found to significantly reduce disruptive behavior as early as kindergarten (Donaldson, Vollmer, Krous, Downs, & Beard, 2011). Tingstrom and colleagues reviewed more than 30 years of research evaluating variations of the GBG (Tingstrom, Sterling-Turner, and Wilczynski, 2006). The experimental findings for the effectiveness of the Good Behavior Game have been so consistent and powerful that it has been recommended as an extremely cost-efficient “universal behavioral vaccine” (Embry, 2002).

Health Psychology

It is health that is real wealth and not pieces of gold and silver.

Mahatma Gandhi

We can make a commitment to promote vegetables and fruits and whole grains on every part of every menu. We can make portion sizes smaller and emphasize quality over quantity. And we can help create a culture – imagine this – where our kids ask for healthy options instead of resisting them.

Michelle Obama

It is a truism, consistent with Maslow’s pyramid, that one’s health overrides all other factors in one’s life. If one is not healthy it can be impossible to enjoy any of life’s social and vocational pleasures or achieve one’s potential. For practically all of our time on this planet, by today’s standards, humans had relatively brief lifespans. As shown in Kurzweil’s (2001) graph (see Figure 7.7), human life expectancy has doubled from approximately 39 to 78 years since 1850! The major causes of this increase are improved sanitary conditions and inoculations against infectious diseases. We now live at a time where the major causes of death in industrialized countries relate to our health practices. Our nutrition, as implied by our first lady, exercise routines, sleep habits, protective sex practices, use of seat belts, tooth brushing and flossing, adherence to medical regimens, and avoidance of tobacco and excessive alcohol, all impact upon the quality as well as longevity of our lives (Belloc & Breslow, 1972). A preventive approach emphasizing a prudent lifestyle is the most likely path to continued improvements.

Health psychology has emerged as a sub-discipline of psychology dedicated to “the prevention and treatment of illness, and the identification of etiologic and diagnostic correlates of health, illness and related dysfunction” (Matarazzo, 1980). It is hoped that the knowledge acquired through this discipline will enable the development of lifestyle-related technologies essential to the continuation of the upward trend in human life expectancy. Equally important, it is hoped that the quality of life can be improved, resulting in a greater percentage of individuals realizing their potentials. Health psychologist positions exist for those with master’s as well as doctoral degrees. Often training is linked with other specializations in academic/research (e.g., behavioral neuroscience) or practice (e.g., clinical psychology), or attained after earning the doctorate. Sub-specializations include clinical health psychology, community health psychology, occupational health psychology, and public health psychology.

As mentioned in the previous chapter, it has been found that inclusion and completion of homework assignments is essential to the success of cognitive-behavioral procedures (Burns & Spangler, 2000; Garland & Scott, 2002; Ilardi & Craighead, 1994; Kazantzis, Deane, & Ronan, 2000). Albert Bandura (1977b; 1982; 1986, chapter 9; 1997; Bandura & Adams, 1977; Bandura, Adams, Hardy, & Howells, 1980) coined the term “self-efficacy” to refer to an individual’s expectancy that they are able to perform a specific task. Presumably, successful completion of a homework assignment develops this expectancy. Once acquired, the individual is less prone to discouragement and more likely to act upon the desire to change. In the previous chapter, we observed that in several instances (e.g., depression), even though pharmacological treatment was initially as effective as cognitive-behavioral treatment, the benefits were more likely to be sustained with the learning-based treatment. This can be attributed to the self-efficacy beliefs likely to result from the different approaches. In one instance, the person is likely to attribute success to the effects of the drug. Once it is withdrawn, the person may no longer believe that they can cope. In contrast, after cognitive-behavioral therapy, the person is more likely to believe they have acquired the knowledge and skill to address their problem.

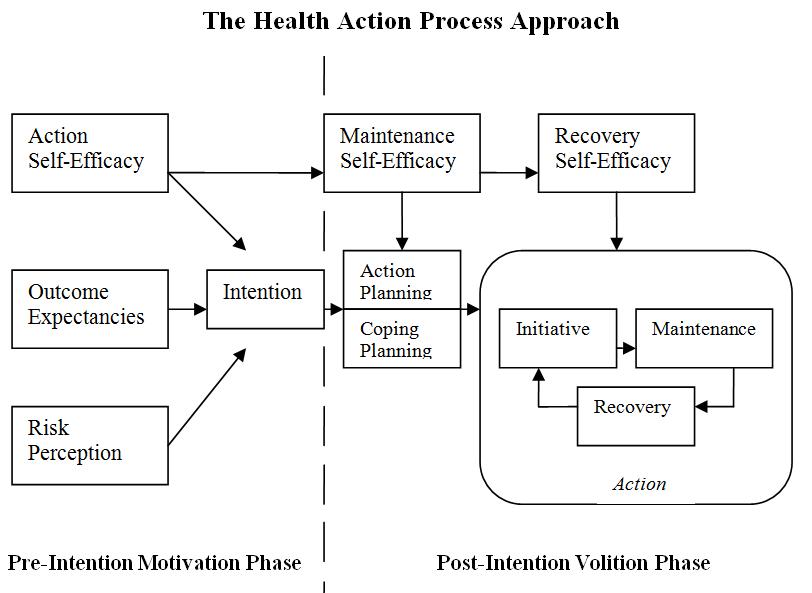

The Health Action Process Approach (see Figure 12.8) emphasizes the importance of different types of self-efficacy in the development of the intent and ability to change health-related behavior (Schwarzer, 2008). We will use smoking as an example. During the motivational stage, even if a smoker perceives it as a problem and expects health to improve as the outcome of quitting, the intent to act requires believing that success is possible. During the volitional stage, even if the smoker formulates an effective plan, success requires believing that quitting can be maintained for an extended period of time and that recovery from any lapses is likely. Relapse prevention techniques should result in increased maintenance and recovery self-efficacy.

Figure 12.1 The Health Action Process Approach (adapted from Schweizer, 2008).

“I think I can, I think I can”

The Little Engine that Could by Watty Piper (1930)

Nothing succeeds like success.

Oscar Wilde

There is an extensive research literature documenting the relationship between self-efficacy and successful change in health habits including: smoking (Dijkstra & De Vries, 2000); dietary changes (Gutiérrez-Doña, Lippke, Renner, Kwon, & Scwarzer, 2009) including Michelle Obama’s desired increase in fruit and vegetable consumption (Luszczynska, Tryburcy, & Schwarzer, 2007); and exercise (Luszczynska, Schwarzer, Lippke, & Mazurkiewicz, 2011). For decades, it was believed that improving students’ self-esteem, as opposed to self-efficacy, would improve their school performance. A comprehensive review of the research literature concluded that the relationship was the result of better school performance improving self-esteem rather than the other way around (Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, 2003). Despite this strong relationship between self-efficacy and successful behavior change, one needs to be careful about concluding cause-and –effect. Self-efficacy can be a seductive pseudo-explanation. Does increased self-efficacy lead to improvement or is it the other way around?

Multisystemic Therapy for Conduct Disorder

It takes a village to raise a child.

African proverb

I chaired the Department of Psychology for 24 years, an unusually long stretch. Often, less-experienced chairs from other departments would ask me about my “administrative style.” Eventually I arrived at the term humanistic ecology to describe my interpretation of the chair’s role (Levy, 2013, pp. 231-232). The same term could be applied to the roles of parent, friend, teacher, mentor, administrator, clergy member, coach, or helping professional. One is even being a “humanistic ecologist” when engaged in a self-control project. From Maslow’s perspective, humanism requires supporting others in their quests to self-actualize. An ecologist studies the relationships between organisms and their environments. Humanistic ecology involves the attempt to identify and create niches in which individuals are able to achieve their self-defined goals and realize their potential while serving the needs of a social group (e.g., family, work colleagues, team, community, nation, etc.).

Sometimes effective treatment for an individual requires coordination between professional psychologists, family, and appropriate community members. We saw that the gains made by autistic children in institutionalized settings could be lost when they returned to their homes. In order to maintain and build upon previously acquired skills, it was necessary to teach family members and significant others to implement direct and indirect learning procedures. In treating conduct disorder, it has been found that successful treatment in one context (e.g., at home) will not necessarily generalize to another context, such as school (Scott, 2002). In Chapter 11, multisystemic therapy (MST) was mentioned as a promising approach to treating severe, intractable cases of conduct disorder. As described, children and adolescents diagnosed with conduct disorder must frequently cope with economic, interpersonal, substance abuse, and criminal justice issues confronting their families and friends. In the same way that treating an individual for malaria would not protect them from contracting the disease when they returned to a mosquito-infested environment, treating a child for conduct disorder would not provide protection from the difficult and discouraging realities they face on a day-to-day basis. Effective long-range treatment requires altering the environmental conditions in order to encourage and sustain desired behavioral changes.

MST is a comprehensive treatment approach to conduct disorder incorporating evidence-based practices in the child’s home, school, and community (Henggeler & Scaeffer, 2010; Scott, 2008; Weiss, Han, Harris, Catron, Ngo, Caron, Gallop, & Guth, 2013). MST targets such serious behavioral excesses as fighting, destroying property, substance abuse, truancy, and running away. Targeted behavioral deficits may include communication (e.g., initiating and sustaining a conversation), social (e.g., sharing and cooperating), and academic (e.g., reading and math) skills. Services are provided in the natural environment as opposed to an office. Treatment is intense, usually consisting of direct contact for about five hours per week for up to six months. Staff members are continuously available at other times to provide assistance and address emergencies. The treatment objective is to transform the child’s environment from one that fosters and sustains the behavioral excesses to one that discourages and eliminates them. This requires a comprehensive, detailed analysis of the antecedents, behaviors, and consequences (i.e., the “ABC”s) within the specific environmental circumstances. Vygotsky’s developmental principles of incorporating zones of proximal development and scaffolding are implemented through the use of prompting, fading, and shaping procedures. A problem-solving process is followed, incorporating the results of continual assessment into an evolving intervention strategy in the different contexts. Family members are taught to systematically monitor the child’s (or adolescent’s) behavior and provide appropriate consequences, including explanations. Communication between parents and consistency in their enforcement of rules is encouraged to prevent a “good cop, bad cop” pattern from emerging. Attempts may be made to monitor and influence choice of friends, encouraging the development of a peer group of positive role models. Regular meetings are scheduled between parents and teachers to discuss the behavioral and academic performance of the child. After-school time is monitored and structured carefully to promote studying and decrease the likelihood of engaging in anti-social activities. Role-playing exercises are designed to prepare the child to resist peer pressure to use drugs or engage in delinquent behavior (Henggeler, Melton, & Smith, 1998; Henggeler, Schoenwald, Borduin, Rowland, & Cunningham, 2009). It may not require a village, but MST typically includes a doctoral-level psychologist supervising three or four master’s-level psychologists, each with a caseload of four to six families. Therapists may initially meet with the family on a daily basis, gradually reducing the frequency to once a week (Henggeler & Schaeffer, 2010). Several randomized outcome studies have found MST effective in reducing rearrests and improving behavioral functioning with youth and adolescents diagnosed with conduct disorder (Butler, Baruch, Hickey, & Fonagy, 2011; Timmons-Mitchell, Bender, Kishna, & Mitchell, 2006; Weiss, et al., 2013). Follow-up studies ranging from two (Ogden & Hagen, 2006) to 14 years (Schaeffer & Borduin, 2005) have found the effects to be long-lasting. Recidivism rates were 50% for individuals receiving MST in comparison to 81% for those receiving standard care. MST treated adults (an average of almost 29 years old at follow-up) were arrested 54% less frequently and confined for 57% fewer days (Schaeffer & Borduin, 2005). Meta-analysis is a statistical procedure used to combine the results of several different research studies to determine patterns of findings and estimates of the size of the effect of independent variables. Meta-analyses have confirmed the short- and long-term effectiveness of MST in treating conduct disorder (Curtis, Ronan, & Borduin, 2004; Woolfenden, Williams, & Peat, 2002).

The proverbial “round peg in a square hole” is a useful metaphor for the human condition and for humanistic ecology. We are all “pegs” doing our best to fit our current environmental circumstances (“holes”). We are born essentially “shapeless”, requiring parents and significant others do their best to “shape us up.” Sometimes, those who care require professional assistance to get us to fit comfortably. Usually, professional assistance consists exclusively of trying to change the shape of the peg to conform to the hole. As we saw with autism spectrum and conduct disorders, this approach can be insufficient. Sometimes it is necessary to also change the shape of the hole. Parent training and the more comprehensive multisystemic therapy are examples of this strategy.

Psychology and Human Potential

Upon completing the discussion of psychological approaches to treating and preventing maladaptive behavior, we have reached the end of our story. We can now consider the implications of what we have learned about the discipline of psychology and human potential. Theoretically, the multi-systemic approach to treatment of conduct disorders could be expanded to achieve al least the first 3 (of 30) articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/) listed in Chapter 7 (repeated below). Our homes, schools, communities, and nations could collaborate to realize the following:

Article 1.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Article 2.

Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty.

Article 3.

Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.

Article 1 implies all humans are born with the same genome. In chapter 1, we saw how the combination of our large frontal cortex and physical features permitting speech and use of tools enabled us to transform the world and human condition. Our imagination combined with communication, collaboration, and manipulation seem unlimited in their application. They could be directed toward achieving the goals of the first three articles. As described in the first article, this requires communicating, collaborating, and manipulating in a spirit of brotherhood. Tragically, human pyramids of hate interfere with climbing Maslow’s human needs pyramid. By emphasizing the article 2 differences of race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status, we fail to recognize and fulfill the potential of our common humanity. Fulfilling our potential will only be achieved when we insure the opportunity for everyone to satisfy the Article 3 human survival, interpersonal, self-esteem, and self-actualization needs. Then “What a wonderful world it would be!”

Afterward

Mighty oaks from tiny acorns grow. Human potential starts with our genome

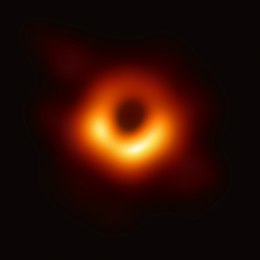

The acorn/mighty oak metaphor was used at the beginning of the first chapter to describe how the realization of human potential results from the impact of experience on our genome. Learning to use our abilities to imagine, communicate and manipulate enabled us to understand and change our world. Technological developments enabled us to overcome the limitations of our genome by enhancing those basic abilities. Our senses are seemingly infinitely expanded by devices such as the telescope and microscope. Digitization has resulted in the soon-to-be-reached reality of every individual having the accumulated knowledge of our species at their fingertips combined with the ability to instantaneously communicate with others, no matter the distance. Dobzhansky (1960) described humans as a supraorganic species. Collaboration enables us to magnify the potential that resides within individuals. It was necessary not only to imagine Manhattan, communicate with each other, and use tools. We had to work as a team to produce the final result. It would appear that the potential of our species is unlimited. In the 1700s, the scientists John Michell and Pierre-Simon Laplace imagined gravitational fields so powerful that not even light could escape. For this reason, these imaginary fields were described as “black holes.” In April of 2019, the first image of a black hole appeared in newspapers throughout the world. More than 200 scientists on four continents collaborated, simultaneously using eight radio telescopes to produce the following image:

Figure 12.2 The supermassive black hole at the core of supergiantelliptical galaxyMessier 87, with a mass ~7 billion times the Sun’s, as depicted in the first image released by the Event Horizon Telescope (10 April 2019).

Unfortunately, these wonderful abilities to imagine, communicate, manipulate and collaborate evolved under conditions where selfishness, greed, impulsivity, fear of strangers and aggression were all adaptive. Now, these tendencies threaten the very survival of our species. At this time, it is not clear that what appears to be our unlimited potential will be realized. It may be that surviving on earth will be the human species’ greatest challenge. Let us collectively imagine, communicate, manipulate and collaborate to protect ourselves and build a better earth while exploring the universe.