Learning Objectives

- Describe the different origins of psychiatry and clinical psychology

- Describe differences between psychiatric (biological) and psychological (experiential) approaches to assessment and treatment of maladaptive behavior

- Describe some of the behavioral excesses and deficits associated with DSM 5 major developmental (intellectual disability and autism spectrum) disorders

- Describe examples of the extreme symptoms that characterize schizophrenia and the effects of drugs and experiential treatments in addressing behavioral excesses and deficits

- Describe some of the symptoms of major depressive and anxiety disorders

Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology

Life is complicated – A Lot Can Go Wrong

Eat, survive, reproduce, and think about the meaning of life. Every human addresses these concerns. We have seen how our genes and experiences interact to enable us to survive, perceive, learn, think, develop, and adapt to the current physical and social environment. Humans have attained varying degrees of success in achieving their potential under extraordinarily different conditions throughout their history on the planet. This is the fourth and final chapter in the nature/nurture section of the book. We have seen how nature and nurture interact during different developmental stages to influence our individual personalities and interpersonal relationships.

Tragically, some fetuses inherit genes or encounter environmental conditions resulting in their not surviving till birth. For most of our history, the birth process itself was extremeley dangerous and many infants did not survive. Until recently, humans lived under harsh geographic and climatic conditions including life-threatening predators. Many perished during childhood and early adulthood. Thankfully, a sufficient number managed to survive long enough to reproduce and sustain our species.

The Nukak survived for thousands of years under some of the least habitable conditions on earth. Over the millennia, it is likely that some of the Nukak inherited characteristics that made it difficult for them to learn to eat, survive, or reproduce. Some children may have exhibited unusual, or annoying, or disturbing behaviors. Such children were dependent upon caretakers for greater investments in time and energy. As mentioned earlier, some Stone-Age nomadic tribes abandoned unwanted children. If caretakers were unsuccessful in efforts to modify problematic behaviors, these children might be subject to shunning, abandonment, or worse. These natural and social selection processes probably resulted in extremely hardy, low-maintenance tribe members.

With the advent of agriculture and animal domestication, human communities increased in size, from dozens, to hundreds, to thousands, to millions. Different social arrangements and institutions became necessary. Governments were formed to create and enforce consensually agreed upon norms for behavior. As a species, we became increasingly tolerant of individual differences and implemented laws to protect infants and children inheriting or developing medical and behavioral problems.

Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology

Some medical and behavioral problems are sufficiently serious to be considered illnesses or disorders. I have described psychology as the science of human potential. Achieving one’s potential is an adaptive process taking place within a specific environmental context. A mental illness or a psychological disorder is usually inferred when a person’s thoughts, emotions, or behavior appear to interfere with or prevent adapting to the current environment and fulfilling one’s potential.

Two different professions emerged to address the wide spectrum of problems that can interfere with adaptation or self-fulfillment. Because of the very different histories, traditions, explanatory models, and professional organizations, there has frequently been confusion and sometimes controversy concerning the appropriate boundaries and relationships between these two professions. Fortunately, both professions have evolved to the point that these boundaries are becoming increasingly clarified and the relationships increasingly collaborative and synergistic.

The medical profession applies the findings of the basic biological sciences to conditions that threaten the health or vitality of individual animals. Veterinarians treat animals other than humans. As disciplines, including sciences, advance and acquire more knowledge, they typically fragment into specialized sub-disciplines. There are a number of such specializations for the medical treatment of humans. Some address problems with specific parts of human structure, such as nephrology (kidneys), ophthalmology (eyes), orthopedics (muscles and bones), and otolaryngology (ear, nose, and throat). Other medical specializations address problems with specific biological functions such as cardiology (circulation), endocrinology (glandular functions), gastroenterology (digestion), and neurology (the nervous system). Some specializations are specific to certain times of one’s life; obstetrics for birth, pediatrics for childhood, and gerontology for the aged. Speaking of the aged, Dr. Seuss (Geisel, 1986) wrote a book for adults entitled You’re Only Old Once! It describes the types of medical doctors one acquires as they get older. I used to think the book was funny! Similar to medicine, professional psychology has evolved and developed specialized, applied, sub-disciplines. The practices of some of these professions will be described in Chapter 12.

Psychiatry and clinicalpsychology are the specializations within professional medicine and psychology that address problems related to adaptation and personal fulfillment. Although both disciplines recognize the importance of nature and nurture in the understanding of human behavior, they have different emphases. Each specialization employs the schematic framework of its parent discipline. Psychiatry assumes the causes and treatment for adaptive problems are based on biological mechanisms. Clinical psychology assumes that although problems may be based on nature/nurture interactions, effective treatment can be entirely experiential. One would expect that each discipline would employ treatment methods exclusively based upon its underlying science. This has not always been the case in the past, which is part of the reason for the confusion regarding the roles and boundaries of the two professions.

The Separate Histories of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology

Although it is commonly understood that biology and psychology are separate disciplines, the separation between psychiatry and clinical psychology is less familiar. The contributions of the early schools of psychology (structuralism, functionalism, Gestalt psychology, and behaviorism) were reviewed in Chapter 1. Over time, the basic content areas comprising most of the chapters in this book developed and evolved. Contemporary approaches to clinical psychology apply the research findings from these content areas, particularly the principles of direct and indirect learning (Chapters 5 and 6). In general, psychological approaches involve assessing and providing experiences to improve an individual’s ability to adapt to their environmental conditions and realize their potential.

The word psychiatry, initially defined as “medical treatment of the soul”, was introduced by the physician Johann Reil in 1808 (Shorter, 1997). At that time, when families could not provide the necessary care or individuals displayed unusual, self-destructive, or dangerous behaviors, they were often placed in monasteries or jailed. As communities increased in size and the numbers of such individuals overwhelmed existing facilities, asylums were created to house them. The negligent, frequently abusive treatment of individuals in asylums, led to this approach eventually being abandoned. Asylums were replaced in the latter half of the 19th century, for those who could afford them, by more fashionable spas (Shorter, 1997). Over the next century, two distinct psychiatric approaches emerged, one based on advances in the biological sciences; the other on Freud’s personality theory (see Chapters 9 and 12). Advances in the biological sciences and controversies regarding the scientific basis for Freudian theory and treatment led to the emergence of anti-psychiatry initiatives in the 1960s (Cooper, 1967; Szasz, 1960). The development of effective pharmacological treatments and the reluctance of insurance companies to pay for frequent “talk therapy” sessions resulted in eventual rejection of the Freudian model in favor of a purely biological model of psychiatry (Shorter, 1997). A benefit of these developments has been increased clarity concerning the complimentary roles played by psychiatry and clinical psychology. It is necessary to assess the appropriate balance of biological and experiential approaches to treatment for every client. We will now consider the historical, disease-model approach to diagnosis of disorders implemented by the American Psychiatric Association. Toward the end of the chapter, an alternative, psychological approach to assessment of maladaptive behavior will be described.

The Medical Model and DSM 5

Is psychiatry a medical enterprise concerned with treating diseases, or a humanistic enterprise concerned with helping persons with their personal problems? Psychiatry could be one or the other, but it cannot–despite the pretensions and protestations of psychiatrists–be both

Thomas Szasz

A medical model treats adaptive disorders as though they are diseases; thus, the term “mental illness.” The medical model has been enormously successful in the treatment of biological disorders ranging from broken bones, to common colds, to infectious diseases, to heart disease, and cancer. Thomas Szasz (1960), a psychiatrist, wrote an extremely controversial, provocative, and influential book entitled The Myth of Mental Illness. He argued that illnesses result from biological malfunctions but that behavioral disorders do not. Szasz considered the labels for different mental illnesses to be pseudo-explanations; labels for the behaviors they purport to explain. That is, the different labels used for mental illnesses are defined exclusively by a constellation of behaviors as opposed to an underlying biological pathology. Recalling the example from Chapter 1, the disease term “influenza” stands for the relationship between a specific pathogen (virus or bacteria) and a syndrome of symptoms. In comparison, the disease term “schizophrenia” is defined exclusively as a constellation of behaviors (i.e., on the dependent variable side). No cause (i.e., independent variable) is specified. Remember the opening line of this book. There are things I think I know, things I think I might know, and things I know I do not know. Szasz is telling us that we know less than we think when we are given a mental illness label.

If one approaches a disorder as an illness, the function of assessment is to determine a medical diagnosis. A useful diagnosis provides information concerning the etiology (i.e., initial cause and/or maintaining conditions), prognosis (i.e., course of the disorder in the absence of treatment), and treatment of a biological syndrome (i.e., collection of symptoms occurring together). Many disease names (e.g., influenza, malaria, polio, etc.) provide information about the underlying mechanisms that cause and sustain a syndrome of specific symptoms. However, this is not always the case, even for biological disorders. For example, hypertension is exclusively defined by the magnitude of one’s blood pressure readings. Despite the fact that the term does not explain the elevated pressure, it is still useful since it provides information concerning prognosis and treatment. If hypertension is left untreated, blood pressure remains elevated. Treatment usually follows a course from least to increasing levels of invasiveness. It might begin with the recommendation to decrease sodium (e.g., salt) in your diet and to increase exercise. Psychiatric illness labels are also defined exclusively on the dependent variable (in this instance, behavioral) side. One might be diagnosed as schizophrenic based on the report of hallucinations (see below). Even though the term “schizophrenia” provides no information about the cause(s) of hallucinations, it does provide information about prognosis and treatment. Hallucinations will continue in the absence of treatment; anti-psychotic medications will probably help.

The American Psychiatric Association (2013) compiles a comprehensive listing of mental illness disease labels and definitions (i.e., criteria) in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The DSM, published initially in 1952, has undergone periodic revision; DSM-II in 1968, DSM-III in 1980, DSM-III-R (revised) in 1987, DSM-IV in 1994, DSM-IV-TR (text revision) in 2000, and DSM-V in 2013. Starting with DSM-III, the Freudian psychoanalytic influence was reduced and the attempt made to establish consistency with the World Health Organization publication, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. Recognition of the overlap between psychiatry and psychology and the limitations of the illness labels are indicated in the DSM-III Task Force quote, “Each of the mental disorders is conceptualized as a clinically significant behavioral or psychological syndrome.” Some considered DSM-III to represent a significant advance from the prior DSMs (Mayes & Horwitz, 2005; Wilson, 1993). It became the international standard for psychiatric classification and for such practical concerns as informing legal decisions (e.g., whether an individual was competent to stand trial) and the determination of health insurance payments.

DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) lists the following types of psychiatric disorders:

- Neurodevelopmental disorders

- Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders

- Bipolar and related disorders

- Depressive disorders

- Anxiety disorders

- Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders

- Trauma- and stressor-related disorders

- Dissociative disorders

- Somatic symptom and related disorders

- Feeding and eating disorders

- Sleep–wake disorders

- Sexual dysfunctions

- Gender dysphoria

- Disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders

- Substance-related and addictive disorders

- Neurocognitive disorders

- Paraphilic disorders

- Personality disorders

The next sections provide summaries of these major DSM-5 listings, including suspected causes and current treatment approaches.

DSM 5 – Neurodevelopmental and Schizophrenic Spectrum Disorders

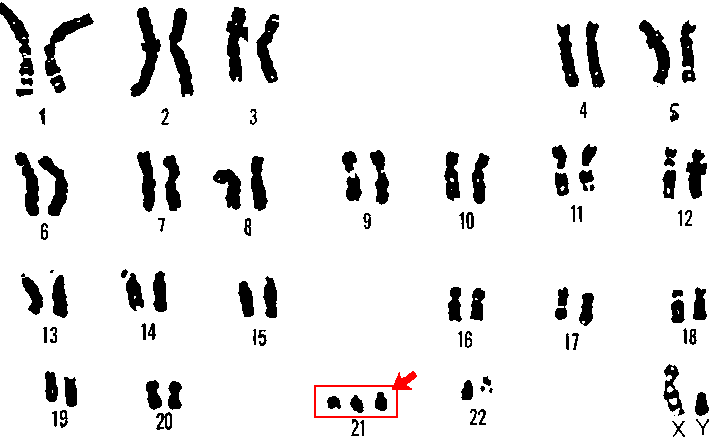

The diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders is based on clinical and behavioral observations made during childhood and adolescence. These disorders are suspected to be the result of impairments in the brain or central nervous system resulting from heredity or problems occurring during fetal development. Debilitating neurodevelopmental disorders with known genetic causes are Down syndrome (an intellectual disability disorder) and fragile-X syndrome (an autism spectrum disorder). Down syndrome (Figure 11.1) occurs when a child inherits a fragment or entire third copy of the 21st chromosome (Figure 11.2).

Figures 11.1 and 11.2 Chromosome 21 and Down’s syndrome.

Fragile-X syndrome results when there is a mutation of a known specific gene on the X chromosome (Santoro, Bray, & Warren, 2012). The following videos provide information regarding Fragile-X and autism spectrum disorders in young children.

The goal of psychiatry, to determine the biological mechanisms underlying DSM disorders, is gradually being realized. The initiatives in neuroscience described in Chapter 2, promise to speed up the acquisition of such knowledge. For example, it has recently been determined that autism results from an increase of patches of irregular cells in the frontal and temporal cortexes during fetal development (Stoner, Chow, & Boyle, et al., 2014). These are the parts of the brain involved in complex social relationships and language, both of which are problematic in those suffering from autism spectrum disorders. The parents of 11 autistic children who died donated their brain tissue for analysis. Recently developed imaging techniques detected irregular patches of cells in these areas in 10 of the 11 brains. In comparison, similar patches were observed in the brain tissue of these areas for only 1 of 11 children without autism. No such patches were discovered in the visual cortex for either sample. This is consistent with the fact that autistic individuals do not suffer from visual deficits (Stoner, Chow, & Boyle, et al., 2014). Such findings increase hope that advances in our understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders will result in more targeted and effective treatments in the future. At present, these disorders substantially impact a child’s potential intellectual, social, and vocational achievements.

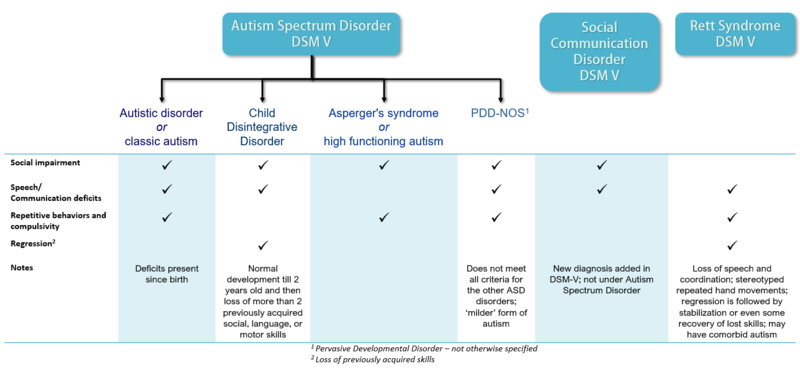

DSM-5 incorporates several significant changes from previous editions. One important change was making the diagnosis of intellectual development disorder based on deficits in intellectual (e.g., language, reading, math), social (e.g., quality of friendships, interpersonal skills, empathy), and practical (e.g., personal grooming, time management, money management) functioning. In the past, scoring below 70 on an IQ-test was the exclusive criterion. Another significant change in DSM-5 is the collapsing of categories that had historically been sub-divided into types. For example, both autism and schizophrenia are now considered “spectrum” disorders requiring determination of severity rather than type. Figure 11.3 portrays the range of debilitation in autism spectrum disorders. Those diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome or Pervasive Developmental Disorder in prior DSMs, are considered to be on the “mild” part of the spectrum. Those previously diagnosed as autistic are considered to be on the severe end of the spectrum, based on the nature and extent of behavioral symptomology and learning disability.

Figure 11.3 Autism spectrum disorders.

The previous categories of autism and schizophrenia spectrum disorders were collapsed because of the poor reliability of diagnoses for the sub-types of disorders. Reliability refers to the likelihood that two psychiatrists arrive at the same diagnosis for an individual. For example, if two physicians took your temperature, they should both obtain the same reading. Otherwise, the thermometer would have no value. It has been demonstrated that psychiatrists are reliable in their diagnoses of the generic disorders (e.g., autism or schizophrenia) but not the different sub-types that had been listed in prior editions of the DSM (e.g., Asperger’s Syndrome, PDD, etc.).

Throughout this book we have seen the utility of the scientific method in establishing cause-effect relationships in psychology. We have come a long way in understanding how nature and nurture interact to influence feeling, thought, and behavior. Just as success in the basic sciences of physics and chemistry led to technologies enabling transformation of our environmental conditions, success in psychology has resulted in technologies of behavior change. For decades, practice in the helping professions, including psychology, was based on tradition, anecdotal evidence, and case studies. In the early 1990s, an approach to clinical practice based on application of the scientific method known as evidence-based practice emerged in medicine, psychology, education, nursing, and social work (Hjørland, 2011). The discipline of psychology only considers the results from experimentally controlled outcome studies including a plausible baseline control condition as credible evidence (Chambless & Hollon, 1998). The APA issued initial recommendations and later established a Task Force describing psychology’s commitment to evidence-based practice (American Psychological Association, 1995; APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice, 2006). The APA Division of Clinical Psychology maintains a website listing current evidence-based treatments for behavioral disorders (http://www.div12.org/PsychologicalTreatments/index.html). It is an excellent resource for determining the current state-of-the-art in clinical psychology.

Currently, there is no known effective medical treatment for autism spectrum disorders. It is hoped that progress in the neurosciences will produce effective interventions in the future. Until we are able to address the underlying biological mechanisms for the disorder(s), the best we can do is to try to address the behavioral symptoms. The learning-based treatment known as applied behavior analysis (ABA) has been successful in this regard. This approach will be described in depth in the following chapter. For now, it is important to note that even if a behavioral disorder stems from biological mechanisms, it can still be successfully treated with non-biological, learning-based procedures. The reverse may also be true. That is, in some instances it may be possible to address non-biological behavioral disorders medically, for example with drugs.

The most commonly diagnosed DSM-5 neurodevelopmental disorder is attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), affecting approximately six percent of children all over the world (Wilcutt, 2012). ADHD is diagnosed when instances of attention-related problems (e.g., distractibility, daydreaming, etc.) occur in multiple settings. Inattentive children tend to have more difficulty in school than at home or with friends whereas the reverse is true for impulsive children who benefit from structure (Biederman, 1998). ADHD is diagnosed three times as often in boys than girls, resulting in controversy (Sciutto, Nolfi, & Bluhm, 2004). Adolescents and adults frequently learn to cope on their own (Gentile, Atiq, & Gillig, 2004).

ADHD is our first example of the concern expressed by Szasz regarding the appropriateness of applying the medical model to behaviorally-defined problems. Attentional problems are inferred from distractibility, inability to maintain focus on a single task, becoming bored with non-pleasurable activities, daydreaming, or not paying attention to instructions. Hyperactivity can be inferred from fidgeting in one’s seat, non-stop talking, blurting things out, jumping up and down, or impatience. All of these examples of attentional and hyperactivity problems are characteristic of practically all children. There is a saying that “if the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem that comes along looks like a nail.” Psychiatrists are trained as physicians to diagnose and treat illnesses. Treatment usually consists of prescribing medication. Many question the validity of considering ADHD a psychiatric disorder and the ethics of prescribing medications for so many children (Mayes, Bagwell, & Erkulwater, 2008; Schonwald & Lechner, 2006; Singh, 2008). Szasz (2001, p. 212) concluded that ADHD “was invented and not discovered.”

Two comprehensive literature reviews of experimental studies found learning-based treatment effective with children diagnosed as ADHD (Fabiano, Pelham, Coles, Gnagy, Chronis-Tuscano, & O’Connor, 2009; Pelham & Fabiano, 2008). A multi-faceted approach including parent training, teacher-parent classroom intervention, and an individualized program addressing independent work habits and social skills, has demonstrated significant improvements in ADHD second- through fifth-graders (Pfiffner, Villodas, Kaiser, Rooney, & McBurnett, 2013). Learning-based approaches to improving school performance will be described in more detail in the next chapter as we consider the role of professional psychologists in enabling individuals to achieve their potential in different environments.

Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders

Schizophrenia is probably the DSM diagnosis most resembling the stereotype of “mental illness.” It is a disabling disorder characterized by severe cognitive and emotional disturbances. Schizophrenia is most likely to first appear late in adolescence or in early adulthood (van Os & Kapur, 2009). The symptoms are unusual and often bizarre. They may include delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, catatonic behavior, or flat affect (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Delusions are strongly held beliefs having no basis in fact. One common delusion is that one’s behavior is being controlled by external forces (e.g., electric wires or “aliens”). Another is the belief that one has exceptional qualities or talents (i.e., delusions of grandeur). Hallucinations are inferred when an individual behaves as though a non-apparent event is occurring; for example, speaking to someone who is not present. “Word salad”, in which words are spoken in a meaningless fashion, is a common form of disorganized speech. Catatonia is a state of immobilization which can occur for a variety of reasons, including stroke, infection, or withdrawal from addictive substances. Sometimes an individual diagnosed with schizophrenia assumes the posture of a “waxy figure”, remaining still unless manipulated by another person. Flat affect refers to the lacking of emotional expression; the individual does not appear to experience emotions appropriate to the situation. Schizophrenia is commonly misunderstood as referring to a “split personality.” What had been diagnosed as Multiple Personality Disorder in previous editions of the DSM is now considered Dissociative Personality Disorder, and will be discussed below.

Schizophrenia is a chronic disorder with between 80 and 90 percent of the patients retaining the diagnosis over a ten-year period (Haahr, Friis, Larsen, Melle., Johannessen, Opjordsmoen, Simonsen, Rund, Vaglum, & McGlashan, 2008). In extreme forms, schizophrenia can be debilitating. The differences appear to reflect influences by both nature and nurture. The risk of developing schizophrenia increases as a function of the percentage of genes shared (nature) as well as similarity of environment (nurture). Identical twins are almost three times as likely to develop schizophrenia as fraternal twins. Fraternal twins as well as ordinary siblings share half their genes. Fraternal twins are likely to have more similar environments than ordinary siblings and are twice as likely to develop schizophrenia (Gottesman, 1991). Unlike Down and Fragile X syndromes, several genes are thought to be involved in schizophrenia (Picchioni & Murray, 2007).

In 1955, approximately 550 thousand Americans were housed in public psychiatric institutions. Development of anti-psychotic medications and implementation of federally funded treatment programs resulted in a dramatic reduction in this population to 100,00 by 1985 (Torrey, 1991). An unfortunate byproduct of this deinstitutionalization was that many patients diagnosed as schizophrenic were imprisoned or left homeless, without treatment (Eisenberg & Guttmacher, 2010).

The psychological model of maladaptive behavior, described later, distinguishes between behavioral excesses and behavioral deficits. A similar distinction is often made by psychiatrists between positive (i.e., excesses) and negative (i.e. deficits) symptoms of schizophrenia. Reports of delusions, hallucinations, or disordered speech are examples of schizophrenic behavioral excesses (positive symptoms). Behavioral deficits can include flat affect (i.e., little emotionality), poor interpersonal skills, and lack of motivation to succeed. Although behavioral deficits may be less disturbing than behavioral excesses, they actually interfere to a greater extent with daily functioning and are less responsive to medication (Smith, Weston, & Lieberman, 2010; Velligan, Mahurin, Diamond, et al. (1997). Medication suppresses delusions and hallucinations but cannot teach interpersonal skills or motivate an individual to achieve their potential. Although they are limited to positive symptoms, drugs still remain an effective approach to treating those diagnosed as schizophrenic (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2009).

Prior to deinstitutionalization, token economy procedures based on direct and indirect learning principles were successfully applied to schizophrenic populations within large psychiatric facilities (Ayllon & Azrin, 1968; Kazdin, 1977; Paul & Lentz, 1978). Token economies establish contingencies between a tangible generalized reinforcer (i.e. token) and desirable behaviors. Usually, a type of “store” is established, permitting the exchange of tokens for desirable items or opportunities to engage in pleasurable activities (Martin & Pear, 2011, pp. 305-319). After the drastic decline in inpatients resulting from use of anti-psychotic medications, there was a corresponding decline in the need for token economies in institutional settings. Still, additional treatment was necessary to address the behavioral and motivational deficits typically remaining after schizophrenics were released.

In a seminal study, therapy in which families were taught to manage the symptoms of schizophrenia (e.g., by monitoring compliance with taking medications, reducing stress, providing support) combined with medication, was shown to reduce relapse rates beyond that attained with medication alone (Goldstein, Rodnick, Evans, May, & Steinberg, 1978). Medication alone resulted in a 25% reduction in relapse in comparison to the placebo control and the addition of family therapy reduced relapse by an additional 25% (Dixon, Adams, & Lucksted, 2000; Dixon & Lehman, 1995).

Comprehensive reviews of controlled outcome studies evaluating cognitive-behavioral and family intervention treatments in which schizophrenics were taught to re-evaluate their symptoms, develop coping strategies, and engage in reality testing exercises, concluded these approaches were effective for treating negative as well as positive symptoms of schizophrenia (Jauhar, McKenna, Radua, Fung, Salvador, & Laws, 2014; Pilling, Bebbington, Kuipers, Garety, Geddes, Orbach, & Morgan, 2002; Rector & Beck, 2001; Turkington, Dudley, Warman, & Beck, 2004; Wykes, Steel, Everitt, & Tarrier, 2008). In addition, it has been found that fewer drop out of treatment, or relapse afterward, with the learning-based treatment approaches in comparison to when treated exclusively with anti-psychotic medications (Gould, Mueser, Bolton, et al., 2001; Rathod & Kingdon, 2010).

An example of the synergy between psychology and psychiatry is the relationship between basic research in cognition (see Chapter 7) and our current understanding of the nature of the intellectual deficits characterizing different DSM disorders. For example, the percentage of normal functioning for verbal memory, short-term (working) memory, psychomotor speed and coordination, processing speed, verbal fluency, and executive functioning were compared for low- and high-performing schizophrenics (Bechi, Spangaro, Agostoni, Bosinelli, Buonocore, Bianchi, Cocchi, Guglielmino, et. al, 2019).

DSM 5 – Bipolar, Depressive and Anxiety Disorders

Bipolar and Related Disorders

The importance of nature (heredity and biology) in neurodevelopmental and schizophrenia spectrum disorders is readily apparent. Neurodevelopmental disorders appear too early in life for nurture to have a major influence and the symptoms can be physical as well as behavioral. For example, Down syndrome children have distinct anatomical features making them easy to identify. Autistic (including many fragile X) children and schizophrenic adults are usually physically indistinguishable from their peers; however their defining symptoms are extreme and easily identifiable. Individuals with these diagnoses appear to differ from “normal” individuals qualitatively rather than quantitatively. Although it has been proposed in the past (c.f., Kanner, 1943), there is no evidence to suggest that faulty parenting is the cause of autism or schizophrenia. Rather, the evidence supports attributing these severe disorders to an underlying biological problem (Centers for Disease Control, 2011, p. 7).

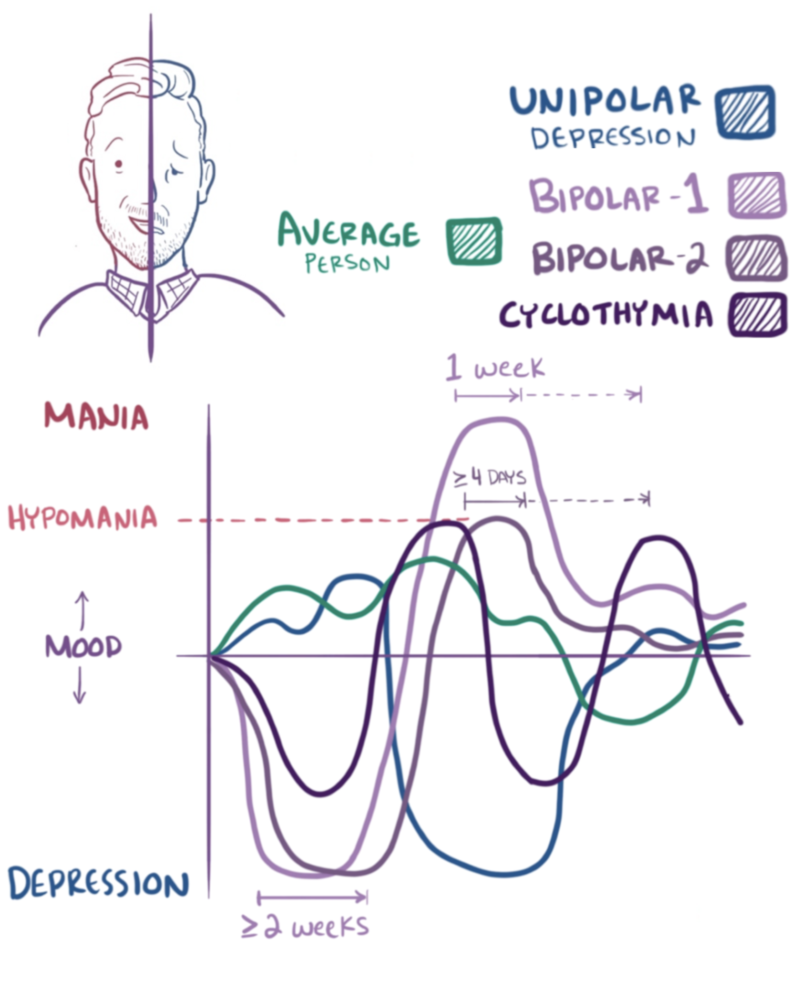

Bipolar disorders are not as obviously influenced by hereditary and biological factors as neurodevelopmental and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Depending upon the severity, those diagnosed with bipolar disorders may appear to differ from others in the extremity, rather than in the type of behavior. The defining characteristic of bipolar disorder is extreme excitability and irritability, referred to as mania. Extreme mania can result in risky life decisions and sleep disorders (Beentjes, Goossens, & Poslawsky, 2012). Figure 11.4 includes sketches of mood changes over a two-month period for individuals displaying the normal pattern as well as those of unipolar depression, bipolar types 1 and 2 as well as cyclothymia. The average person demonstrates relatively mild highs and lows. Unipolar depression is characterized by extreme lows. Bipolar 1 includes extended periods of extreme highs and lows whereas the high is not as extreme in bipolar 2. Cyclothymia is characterized by less severe and more frequent mood swings.

Figure 11.4 Bipolar disorder

Every one experiences “ups” and “downs” in life. Bipolar disorders involve more extreme moods and more frequent mood swings. One’s emotions usually reflect ongoing events in everyday life. The ups and downs of individuals diagnosed as bipolar may be episodic and not dependent upon environmental events. The episodes can be extreme and last as long as six months (Titmarsh, 2013). Evidence suggests there is a genetic component to bipolar disorder. First degree relatives (i.e. parents, offspring, and siblings) are ten times as likely to develop the disorder as the general population (Barnett & Smoller, 2009). Several genes appear mildly to moderately involved (Kerner, 2014). Pharmacologic treatment is often prescribed. Lithium thus far appears to be the most effective drug, particularly for reducing the frequency and intensity of manic episodes (Poolsup, Li Wan Po, & de Oliveira, 2000).

Depressive Disorders

Into every life a little rain must fall.

It is normal to experience sadness and different degrees of depression. Just as manic episodes can be extreme, the same is true for depressive episodes. Depression can be long-lasting and severe in its impact upon everyday functioning. The following are the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder:

At least five of the following symptoms have been present during the same 2-week period and represent a change from previous functioning: at least one of the symptoms is either 1) depressed mood or 2) loss of interest or pleasure.

- Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated either by subjective report (e.g., feels sad or empty) or observation made by others (e.g., appears tearful)

- Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day (as indicated either by subjective account or observation made by others)

- Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain (e.g., a change of more than 5% of body weight in a month), or decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day

- Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day (observable by others, not merely subjective feelings of restlessness or being slowed down)

- Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which may be delusional) nearly every day (not merely self-reproach or guilt about being sick)

- Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day (either by subjective account or as observed by others)

- Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or specific plan for committing suicide (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Due to its high rate of occurrence, major depressive disorder is often referred to as “the common cold of mental illness” (Seligman, 1975). A two-to-one female/male ratio of the incidence of depression has been found across nationality, culture, and ethnicity (Nolen-Hoeskema, 1990). In a review of research addressing these gender differences, Nolen-Hoeskema (2001) cited the higher incidence of the following factors for women; sexual assault during childhood, poverty, and greater responsibilities for child and parental care. She also describes differences in the characteristic ways males and females respond to stressful or disappointing situations. Women are more likely to maintain conscious focus on upsetting events (i.e., ruminate) whereas men are more likely to distract themselves or take action to address the situation (Nolen-Hoeskema, 2001). In the next chapter, we will describe the thinking patterns that are characteristic of those diagnosed with major depressive disorder and the cognitive-behavioral psychological treatments designed to modify these self-defeating patterns. Cognitive-behavioral treatments have been found to be as effective as pharmacological treatments for the short-term treatment of depression and to be more effective in maintaining treatment effects once drugs are withdrawn (Dobson, 1989). Anti-depressive medications may be prescribed for long-lasting episodes or when there are signs of suicidal thinking.

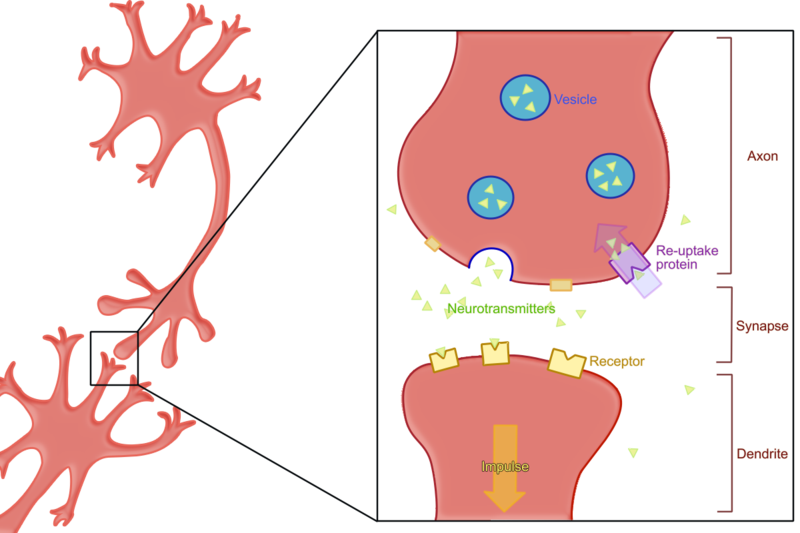

There is consensus among psychologists and psychiatrists that a nature/nurture model is necessary for understanding depression. The popular diathesis-stress model proposes that individuals vary in their susceptibility to depression based on interactions between their genetics and experiences, particularly during childhood (National Institute of Mental Health, 1999). In support of this model, it has been found that variation in the 5-HTT gene influencing the neurotransmitter serotonin increases the likelihood of becoming depressed after experiencing stressful life events (Caspi, Sugden, & Moffitt, 2003). The most popular anti-depressant medications are serum serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) that affect the balance of the neurotransmitters serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine (Nutt, 2008). By inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin, its level is increased in the synaptic cleft enabling it to bind with other neurotransmitter receptor cells (see Figure 11.5).

Figure 11.5 How SSRIs work.

Anxiety Disorders

The transition from high school to college can be very stressful. It requires adapting to a different environment with a host of new responsibilities. If you are not commuting from home, it may be the first time in your life you are living on your own. Your parents are not waking you up in the morning and making sure you are on time for all your scheduled activities. They are not preparing your meals or checking to make sure you did your homework. You probably are experiencing more autonomy and perhaps more problems to solve on your own than ever before.

As we saw in Chapter 5, adaptive learning involves acquiring the ability to predict and where possible, control environmental events. After one is able to predict events, they no longer are surprised or anxious. Anxiety is the name for the feeling that one experiences in anticipation of a possible aversive event. When extreme, anxiety can be accompanied by activation of the autonomic fight-or-flight response including increases in one’s heart rate and rapid breathing. Once one becomes confident they can control events they no longer feel anxious and these physical responses subside. Do you remember your first days on campus when everything was new? How about your first exams? Did it matter what courses your exams were in or did you feel the same about all of them? How did you feel about approaching and speaking to your professors? Do you still feel the same way? I hope you have successfully adjusted to the rhythms and responsibilities of college life. If so, you probably feel a lot less anxious than you did those first days on campus.

The major anxiety disorders listed in DSM-5 include the following:

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- Specific Phobia

- Social Anxiety Disorder (Social Phobia)

- Panic Disorder

Just as we all experience ups and downs, we all experience anxiety and fear. Once again, only when it reaches the point where it interferes with our daily functioning and ability to enjoy life on an ongoing basis, does extreme anxiety or fear become diagnosed as a psychiatric condition. Generalized anxiety disorder occurs across many situations and is chronic. Anxiety and fear are modulated by the primitive part of the brain called the limbic system that was described in chapter 2. General anxiety disorder is thought to be the result of faulty processing of fear between the amygdala and the hypothalamus, brain stem, and cerebellum (Etkin, Prater, Schatzberg, Menon, & Greicius, 2009). These areas are involved in determining the threat level of a stimulus and relaying the information to the cortex for higher-level processing and formulation of a response. Functional MRI imaging was conducted on normal subjects and those suffering from general anxiety disorder. The connections between the amygdala and other brain areas were significantly less distinct in those suffering from the disorder whereas there was increased cortical connectivity. The authors concluded that these results supported a model of general anxiety disorder in which those affected with malfunctioning amygdala were forced to compensate at higher levels of the cortex (Etkin, Prater, Schatzberg, Menon, & Greicius, 2009). Consistent with this cognitive interpretation of general anxiety disorder, as with depression, an extensive review of experimental research evaluating cognitive-behavioral and pharmacologic treatment approaches found them comparable in their short-term effects. Cognitive-behavioral procedures, however, once again demonstrated long-lasting effects whereas pharmacologic improvements disappeared once medication was terminated (Gould, Otto, Pollack, & Yap, 1997).

Unlike general anxiety disorder, which occurs in many situations, the diagnosis of specific phobia applies to an extreme and irrational fear occurring in a specific situation. Common examples of easily acquired fears related to our evolutionary history include spiders, snakes, height, open spaces, confined spaces, strangers, and dead things (Seligman, 1971). Social anxiety disorder (social phobia) refers to extreme and irrational anxiety related to real or imagined situations involving other people. It often involves circumstances in which one is being assessed or judged (e.g., in school, at a party, during interviews, etc.). As described in Chapter 5, desensitization and reality therapy procedures are very effective in treating anxiety and fear disorders. Self-help techniques based on cognitive behavioral strategies have been found effective for some individuals (Lewis, Pearce, & Bisson, 2012).

Panic attacks are unpredictable and can be debilitating. Physical symptoms may include a rapid pulse, shortness of breath, perspiration, and trembling. Symptoms can be so severe as to be interpreted as a heart attack. The person can feel as though they are losing control, going crazy, or dying. Pharmacologic treatment and cognitive behavioral techniques have both been found to be more effective than placebos for the treatment of panic disorders, with the combination producing the best results (van Apeldoorn, van Hout, Mersch, Huisman, Slaap, Hale, & den Boer, 2008).

Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

Obsessions are thoughts that repeatedly intrude upon one’s conscious experience. Compulsions are behaviors one feels the need to repeat despite their interfering with achievement of other tasks. Historically, there has been confusion regarding the different ways in which these terms are used in DSM diagnoses. The distinction is still made in DSM-5 between obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD); the latter will be treated separately under personality disorders. OCD and OCPD can include repetitious behaviors such as hoarding or placing things in neat piles. The OCD individual recognizes these behaviors as problematic whereas the OCPD individual sees them as being appropriate and desirable. OCD is sometimes considered an anxiety disorder with the ritualistic behaviors maintained by stress-reduction (i.e., negative reinforcement). Similar to depression and other anxiety-related disorders, OCD has been successfully treated with SSRIs. The cognitive behavioral technique, exposure and response prevention has been found highly effective in the treatment of OCD (Huppert & Roth, 2003). For example, if a person constantly checks to see if a door is locked, they are permitted to check only once (i.e., they are exposed to the lock and prevented from making the response a second time). A major research study found that exposure and response prevention was as effective alone as when it was combined with medication for OCD (Foa, Liebowitz, Kozak, Davies, Campeas, Franklin, Huppert, Kjernisted, et al., 2005).

Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be acquired through a direct or indirect learning experience. One can experience a traumatic event such as sexual assault, severe injury, or threat of death; or one can observe any of these events occur to someone else, particularly a close friend or relative. Diagnosis of PTSD is usually made when a person reports experiencing recurrent flashbacks of a traumatic event more than a month after it happened. The person may avoid talking about or approaching any reminder of the event (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Similar to major depressive disorder, a diathesis-stress model appears to apply, there being evidence for individual differences in susceptibility to PTSD. In this instance, genes effecting the neurotransmitter GABA were found to be related to the likelihood that individuals experiencing severe trauma as children were diagnosed with PTSD as adults (Skelton, Ressler, Norrholm, Jovanovic, & Bradley-Davino, 2012). Similar findings were obtained with adults who were abused as children. Those having a particular gene were more likely to later develop PTSD (Binder, Bradley, & Liu, 2008). Cognitive-behavior therapy is considered the treatment of choice for PTSD by the United States Departments of Defense (Hassija & Gray, 2007) and Veteran Affairs (Karlin, Ruzek, Chard, Eftekhari, Monson, Hembree, Resick, Foa, & Patricia, 2010).

DSM 5 – Other Disorders

Dissociative Disorders

Dissociative disorders have captured the public’s imagination as the result of several popular books and movies. The disorders are characterized by a disconnect between an individual’s immediate experience and memory of the past. The major dissociative disorders listed in DSM-5 include dissociative identity disorder, dissociative amnesia, and depersonalization disorder.

Dissociative identity disorder is characterized by two or more distinct, integrated personalities appearing at different times. Each personality can exist in isolation from the others, with little or no memory of the other’s existence. Dissociative amnesia is usually a temporary disorder affecting episodic (i.e., autobiographical) memory. It is the most common of the dissociative disorders. Depersonalization disorder is often described as an “out-of-body experience.” You realize it is not true, but feel as though you are watching yourself.

Until the transition to emprically-validated procedures in medicine, Freud’s psychodynamic model was prevalent in psychiatry and still influential in clinical psychology. Multiple personality disorders, amnesia, and out-of-body experiences make wonderful plot lines. The Bird’s Nest (Jackson, 1954), The Three Faces of Eve (Thigpen & Cleckley, 1957), and Sybil (Schreiber, 1973) describe the lives of individuals that fit the DSM criteria for dissociative identity disorder. These books and the movies they spawned (Lizzie, for The Bird’s Nest) were released when the Freudian influence on psychiatry was at its peak. Each told the story of relentless and insightful psychiatrists probing the early childhood experiences of individuals appearing to have different personalities at different times. Eventually, some source of childhood abuse was identified, the person was “cured” and lived happily ever after.

At best, Freud and others, basing their explanations of the causes of maladaptive behavior on uncontrolled case history evidence, offer hypotheses to be tested. No one ever tested Freud’s oedipal conflict interpretation of Little Han’s fear of horses by having a father threaten a child to see if the child projected fear onto another animal. In Chapter 5, we described Watson’s demonstration of the classical conditioning of a fear response to white rats in Little Albert. Watson felt that known, basic learning principles, could account for fear acquisition. He questioned the plausibility of Freud’s interpretation of the development of Little Hans’ fear. Direct and indirect classical conditioning procedures have been found to be effective in producing and eliminating anxiety, fears, and phobias.

Despite the convincing and exciting portrayals of dissociative disorder patients and the therapeutic process, there is now reason to question the Freudian assumptions underlying the narratives. After a comprehensive literature review, it was concluded that there was no credible data supporting the conclusion that dissociative disorders or amnesia result from childhood trauma as opposed to injuries to the brain or disease (Kihlstrom, 2005). The actual person that Sybil was based upon admitted that she faked the symptoms. Analyses of the transcripts of the therapeutic sessions resulted in a very different interpretation of her case and dissociative identity disorders in general (Lynn & Deming, 2010). Recent experimental evidence suggests that sleep deprivation may be an underlying cause of dissociative symptoms. It has been demonstrated that extreme dissociative symptoms can result from a single night’s deprivation of sleep (Giesbrecht, Smeets, Leppink, Jelicic, & Merckelbach, 2007). In another study, half of the patients meeting the criteria for dissociative disorders improved after normalization of their sleep patterns (van der Kloet, Giesbrecht, Lynn, Merckelbach, & de Zutter, 2012; Lynn, Berg, Lilienfeld, Merckelbach, Giesbrecht, Accardi, & Cleere, 2012). It may not be fascinating or provocative, but an effective way to avoid or treat dissociative disorders may be to get a good night’s sleep.

Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders

The diagnosis of somatic symptom disorder is based on the presence of severe medical symptoms (e.g., blindness, loss of the ability to move a hand, etc.) with no indication of a biological cause. The diagnosis of illness anxiety disorder is based on debilitating anxiety resulting from real or imagined health concerns. Health becomes the focus of one’s existence. This often results in spending long periods of time conducting research on a symptom or disease. In the past, such symptoms were described as psychosomatic or hypochondriasis, but these terms are now considered trivializing and demeaning and have been dropped from recent DSM editions. The problem of diagnosing a disorder based on the absence of biological symptoms is recognized as problematic (Reynolds, 2012). DSM-5 emphasizes the presence of behavioral symptoms such as repeated verbalizations or reports of obsessive thinking about health concerns or excessive time spent conducting research regarding medical concerns. As with anxiety and depressive disorders, the most effective treatment for somatic symptom disorders is cognitive-behavior therapy; medications may be prescribed in extreme or unsuccessful cases (Sharma & Manjula, 2013).

Feeding and Eating Disorders

The developmental distinction between feeding and eating disorders has been relaxed somewhat in DSM-5. The feeding disorders, rumination, the regurgitation of food after consumption, and pica, the consumption of culturally disapproved, non-nutritious substances (e.g., ice, dirt, paper, chalk, etc.), are now recognized as occurring in all age groups (Blinder, Barton, & Salama, 2008). The previous diagnosis, feeding disorder of infancy and childhood, has been renamed avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, a broad category applying across the age span (Bryant-Waugh, Markham, Kreipe, & Walsh, 2010).

Direct learning techniques have been used to successfully treat rumination and pica disorders. Rewarding normal eating and punishing the initiation of rumination by placing a sour or bitter tasting substance on the tongue has been found effective in suppressing rumination (Wagaman, Williams, & Camilleri, 1998). Another procedure found to be effective is to teach individuals to breathe from their diaphragm while eating (Chitkara, van Tilburg, Whitehead, & Talley, 2006). Pica disorders have been treated using classical conditioning by pairing the inappropriate substance with a sour or bitter taste. Differential reinforcement procedures in which appropriate eating is followed by presentation of toys but inappropriate eating is not, in addition to time-out procedures, have also been effective treatments with normal individuals (Blinder, Barton, & Salama, 2008) and those with developmental disabilities (McAdam, Sherman, Sheldon, & Napolitano, 2004).

In past DSM editions, anorexia nervosa and bulimia were the only diagnosable psychiatric eating disorders. Women between the ages of 15 and 19 comprise 40% of those diagnosed with these two disorders (Hoek, & van Hoeken, 2003). Binge eating disorder was added as a diagnosable disorder in DSM-5 (Wonderlich , Gordon, Mitchell, Crosby, & Engel, 2009).

Anorexia nervosa is defined in DSM-5 by: 1) low body weight relative to developmental norms; 2) either the expressed fear of weight gain or presence of overt behaviors designed to interfere with gaining weight (e.g., excessive under-eating or extremely intense exercise sessions); and 3) a distorted body image (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Attia & Walsh, 2007).

Anorexia is an insidious and potentially life-threatening disorder. A comprehensive review of 32 studies evaluating the effects of cognitive behavioral procedures alone, medicine alone, and both combined, was inconclusive. Although cognitive behavioral procedures appeared effective for those attaining a normal weight (i.e., preventing relapse), it was not clear that they were effective in helping individuals gain weight in the first place (Bulik, Berkman, Brownley, Sedway, & Lohr, 2007). The treatment results for bulimia nervosa are clearer and better. Bulimia is a disorder characterized by consumption of large quantities of food in a short time (i.e., binging) followed by attempts to lose weight through extreme measures such as induced vomiting or consuming laxatives (i.e., purging). Those diagnosed with binge eating disorder do not engage in purging. In comparison to anorexia, the diagnosis of bulimia or binge eating disorder can be more difficult because the majority of individuals remain close to their recommended weight (Yager, 1991). A review of randomized, controlled studies evaluating cognitive-behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, and medical treatment concluded that although not effective with all individuals, cognitive-behavioral procedures are still the initial treatment of choice (Walsh, Wilson, Loeb, Devlin, Pike, Roose, Fleiss, & Waternaux, 1997). Follow-up studies attempted to determine the predictive factors for an effective treatment outcome. Those exhibiting more severe symptoms and greater impulsivity were more likely to drop out of treatment. In addition, it was found that individuals remaining in treatment and requiring more than six sessions to reduce purging were unlikely to profit from additional cognitive-behavioral treatment. Those with a prior history of substance abuse were also less likely to profit from treatment. Medications were sometimes helpful in treating those not successful with cognitive-behavioral treatment approaches (Agras, Crow, Halmi, Mitchell, Wilson, & Kraemer, 2000; Agras, Walsh, Fairburn, Wilson, & Kraemer, 2000; Wilson, Loeb, Walsh, Labouvie, Petkova, Liu, & Waternaux, 1999).

Promising preliminary results have been obtained with the direct learning procedure, cue-exposure. Binging and purging were reduced in 22 adolescents diagnosed with bulimia who were resistant to other procedures. This was achieved by systematically exposing the adolescents to the specific environmental cues which triggered their binging and purging (Martinez-Mallén, Castro-Fornieles, Lázaro, Moreno, Morer, Font, Julien, Vila, & Toro, 2007). Cue-exposure is an extinction procedure. By repeatedly presenting the specific stimuli without permitting eating to occur, the strength of the cravings produced by these cues is reduced. A recent review describes innovative variations on cue-exposure including virtual reality procedures (Koskina, A., Campbell, L., & Schmidt, U. (2013). Virtual reality techniques have been found effective in simulating idiosyncratic cues, eliciting strong cravings for food in individuals diagnosed with bulimia. Such realism improves the effectiveness of cue-exposure procedures conducted in clinical settings (Gutierrez-Moldanado, Ferrer-Garcia, & Riva, G., 2013; Ferrer-Garcia, Gutierrez-Moldanado, & Pla, 2013).

Sleep–Wake Disorders

We previously saw that a poor night’s sleep could lead to severe psychiatric symptoms. Research has also demonstrated that good sleep habits result in improved health and psychological functioning (Hyyppa & Kronholm, 1989). Worldwide, approximately 30 percent of adults report difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep or experiencing poor sleep quality. Six percent meet the DSM-IV-TR criteria for insomnia disorder of having such symptoms occur at least three times a week and last for at least one month (Roth, 2007).

A National Institute of Health Conference concluded that cognitive-behavioral procedures were at least as effective as medications for treating insomnia and had the advantage of improvements continuing after the procedures were terminated. In addition, learning-based procedures do not pose the risk of undesirable side-effects (NIH, 2005). These conclusions are consistent with the results of several experimental studies and literature reviews (Edinger & Means, 2005; Jacobs, Pace-Schott, Stickgold, & Otto, 2004; Morin, Colecchi, Stone, Sood, & Brink, 1999). A review of six randomized, controlled trials concluded that the computerized self-help administration of cognitive- behavioral procedures was mildly effective and worthy of consideration as a minimally invasive initial approach to treatment (Cheng & Dizon, 2012).

Richard Bootzin (1972) developed an early learning-based approach to the treatment of insomnia based on the principles of stimulus control. Now known as the Bootzin Technique, it requires implementing the following procedures:

- Go to bed only when you are sleepy

- Use the bed only for sleeping

- If you are unable to sleep, get up and do something else; return only when you are sleepy; if you still cannot sleep, get up again. The goal is to associate your bed with sleeping rather than with frustration. Repeat as often as necessary throughout the night.

- Set the alarm and get up at the same time every morning, regardless of how much or how little sleep you’ve had.

- Do not nap during the day (Bootzin, 1972).

There is a substantial amount of empirical support for the effectiveness of stimulus control procedures in addressing insomnia (Bootzin & Epstein, 2000, 2011; Morin & Azrin, 1987, 1988; Morin, Bootzin, Buysse, Edinger, Espie, & Lichstein, 2006; Morin, Hauri, Espie, Spielman, Buysse, & Bootzin, 1999; Riedel, Lichstein, Peterson, Means, Epperson, & Aguillarel, 1998; Turner & Ascher, 1979). Given the documented success of self-help approaches, the Bootzin Technique is certainly worth trying if you ever experience sleep problems.

Sexual Dysfunctions

In Chapter 4, we described Masters and Johnson’s (1966) proposed four-phase human sexual-response cycle consisting of an excitement phase, followed by a plateau, then orgasm, and then a calming phase in which the ability to become excited again is gradually reinstated (see Figure 4.4). A sexual dysfunction refers to a consistent problem occurring during one of the first three phases of normal sexual activity. When occurring during the first stage, problems are defined as sexual desire disorders. When occurring during the second stage, they are defined as sexual arousal disorders, and when during the third phase, as orgasm disorders (e.g., erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation in men).

DSM-5 diagnoses of sexual disorders require durations of at least six months. Sexual desire and performance can be influenced by a multitude of factors including: other psychiatric conditions (e.g., anxiety, depression, etc.); hormonal irregularities (estrogen for women, testosterone for men); aging; fatigue (one more reason for maintaining good sleep habits); medications (e.g, SSRI anti-depressants); and relationship problems. Treatment for sexual dysfunctions can include individual or couples counseling, hormone replacement therapy, prescription of medications, or in extreme cases, implantation of surgical devices.

Gender Dysphoria

It is rare, but sometimes an individual believes their actual gender is different from what they appear to be. This can result in aversion to one’s own body, anxiety, and extreme unhappiness (i.e., dysphoria). A subtle change in DSM-5 was from the term, gender identity disorder, to gender dysphoria. The initial term implied that a problem existed when one felt they were a different gender than the sex assigned at birth. The latter term indicates that this is a problem only when it causes extreme unhappiness and interferes with daily functioning. The evidence suggests that once one establishes a sexual identity as male or female, whether or not it is consistent with one’s hormonally-determined sex, it cannot be altered through counseling (Seligman, 1993, pp. 149-150). All that can be done to reduce psychological distress is to perform sexual reassignment surgery and hormone replacement therapy in accord with the individual’s self-defined sex (Murad, Elamin, Garcia, Mullan, Murad, Erwin, & Montori, 2010). DSM-5 indicates that subsequent to successful reduction in dysphoria, there may still be the need for treatment to facilitate transition to a new lifestyle.

Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders

The chapter on disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders is new to DSM-5. It integrates disorders involving emotional problems and poor self-control that appeared in separate chapters in prior DSM editions, including; oppositional defiant disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, conduct disorder, kleptomania, and pyromania. Diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder depends upon the frequency and intensity of behaviors frequently characteristic of early childhood and adolescence including: actively refusing to comply with requests or rules; intentionally annoying others; arguing; blaming others for one’s mistakes; being spiteful or seeking revenge. Learning-based procedures have been found to be the most effective treatment for oppositional defiant disorder (Eyberg, Nelson, & Boggs, 2008).

The DSM-5 lists the following criteria for intermittent explosive disorder in children at least six years of age:

- Recurrent outbursts that demonstrate an inability to control impulses, including either of the following:

- Verbal aggression (tantrums, verbal arguments or fights) or physical aggression that occurs twice in a weeklong period for at least three months and does not lead to destruction of property or physical injury, or

- Three outbursts that involve injury or destruction within a year-long period

- Aggressive behavior is grossly disproportionate to the magnitude of the psychosocial stressors

- The outbursts are not premeditated and serve no premeditated purpose

- The outbursts cause distress or impairment of functioning, or lead to financial or legal consequences (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

There is evidence for the effectiveness of SSRIs in alleviating some of the symptoms of intermittent explosive disorder (Coccaro, Lee, & Kavoussi, 2009). Overall, however, experimental outcome studies indicate that cognitive-behavioral treatment including relaxation training, cue-exposure to situational triggers, and modifying problematic thought patterns is generally more effective than medication (McCloskey, Noblett, Deffenbacher, Gollan, & Coccaro, 2008).

Conduct disorders are more serious and problematic than the other impulse-control disorders. They are defined by “a repetitive and persistent pattern of behavior in which the basic rights of others or major age-appropriate societal norms or rules are violated” (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Diagnostic criteria require that three or more of the following occur within the span of a year:

Aggression to people and animals

- often bullies, threatens, or intimidates others

- often initiates physical fights

- has used a weapon that can cause serious physical harm to others (e.g., abat, brick, broken bottle, knife, gun)

- has been physically cruel to people

- has been physically cruel to animals

- has stolen while confronting a victim (e.g., mugging, purse snatching, extortion, armed robbery)

- has forced someone into sexual activity

Destruction of property

8. has deliberately engaged in fire setting with the intention of causing serious damage

9. has deliberately destroyed others’ property (other than by fire setting)

Deceitfulness or theft

10. has broken into someone else’s house, building, or car

11. often lies to obtain goods or favors or to avoid obligations (i.e., “cons” others)

12. has stolen items of nontrivial value without confronting a victim (e.g., shoplifting, but without breaking and entering; forgery)

Serious violations of rules

13. often stays out at night despite parental prohibitions, beginning before age 13 years

14. has run away from home overnight at least twice while living in parental or parental surrogate home (or once without returning for a lengthy period)

15. is often truant from school, beginning before age 13 years(American Psychiatric Association 2013).

The diagnosis for conduct disorder distinguishes between childhood-onset and adolescent-onset types. The former requires that at least one of the criteria occur prior to the age of ten. The distinction is also made between severity levels. The conduct disorder is considered mild if there are few problems beyond those required to meet the criteria and only minor harm results. The disorder is considered moderate if the number of problems and harm done is between the levels required for mild and severe. Severe conduct disorder consists of many problems beyond those required to meet the criteria resulting in extreme harm (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Individuals diagnosed with conduct disorder can be extremely destructive and dangerous. In a review of research, rates of conduct disorder ranged from 23% to 87% for incarcerated youth or those in detention facilities (Teplin, Abram, McClelland, Mericle, Dulcan, & Washburn, 2006). It is important to identify the predisposing factors and initiate treatment for conduct disorder as soon as possible. Deficits in intellectual functioning, verbal reasoning, and organizational ability are common (Lynam & Henry, 2001; Moffit & Lynam, 1994). Children and adolescents diagnosed with conduct disorder often live in dangerous neighborhoods under poor financial conditions with a single (possibly divorced) parent and deviant peers. Parental characteristics frequently include: criminal behavior; substance abuse; psychiatric disorders; unemployment; a negligent parenting style with low levels of warmth and affection, poor attachment, and inconsistent discipline (Granic & Patterson, 2006; Hinshaw & Lee, 2003).

Truancy or poor performance in school, frequent fights, or incidents of bullying can be early warning signs for conduct disorder. Medications have been unsuccessful as a treatment approach (Scott, 2008). The results of behavioral training, in which parents are taught to implement the basic principles of direct and indirect learning through instruction, observational learning, and guided practice, have been encouraging (Kazdin, 2010). Necessary skills include systematic and accurate observation of behavior, effective use of prompting, fading, and shaping techniques, and consistent administration of reinforcement, punishment, and extinction procedures (Breston & Eyberg, 1998; Feldman & Kazdin, 1995). Follow-up research has demonstrated treatment effects lasting as long as 14 years (Long, Forehand, Wierson, & Morgan, 1994). Despite the successes of behavioral parent training, it is severely under-utilized due to the lack of availability of a sufficient number of parent-trainers and logistic problems during its implementation. There is the hope that these needs can be addressed by taking advantage of different technologies. Videotapes of expert practitioners can be provided to assist in training. Videotapes of interactions between parents and children may be used to provide feedback on usage of behavioral techniques. Cell phones can be used to maintain communication between the professional staff and parents between meetings (Jones, Forehand, Cuellar, Parent, Honeycutt, Khavou, Gonzalez, & Anton, 2014). In the following chapter, we will describe a comprehensive, “multisystemic” approach to treating conduct disorder (Caron, Catron, Gallop, Han, Harris, Ngo, & Weiss, 2013; Henggeler, Melton, & Smith, 1992) as well as early intervention procedures designed to prevent the disorder from developing in the first place (Hektner, August, Bloomquist, Lee, & Klimes-Dougan, 2014).

Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

The following drugs are considered addictive in DSM-5: alcohol, caffeine, cannabis (marijuana), hallucinogens (e.g., LSD), inhalants, opioids (pain killers), sedatives (tranquilizers), hypnotics (sleep inducers), stimulants (e.g., methamphetamine), cocaine, and tobacco (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Our evolving understanding of the reward mechanisms involved in addictive disorders is an excellent example of the synergy between psychology and psychiatry. For example, the fact that gambling appears to activate the same brain reward mechanisms as drugs, resulted in its inclusion under substance use disorder in DSM-5.

Olds and Milner (1954) discovered that electrical stimulation of certain areas of a rat’s brain served as a powerful reinforcer for a rat’s bar-pressing behavior. Later it was discovered that manipulating the pulse of electrical stimulation produced behavioral effects similar to those resulting from different drug dosages; higher pulse rates acted like higher dosages. The effects were so powerful that rats preferred electrical stimulation to food and would continue to press the bar despite being starved (Wise, 1996)! In this respect, electrical brain stimulation acts in a manner similar to other addictive substances; the individual craves the substance despite self-destructive consequences. The same parts of the brain mediate the reinforcing effects of electrical stimulation and different drugs through the neurotransmitter dopamine (Wise, 1989, 1996).

Similar to autism and schizophrenia, the DSM-5 collapses across previous distinctions between types of substance abuse and addictive disorders and provides criteria for indicating severity. The diagnosis of substance use disorder encompasses the previous diagnoses of substance abuse and substance dependence. The severity of the disorder is based on the number of symptoms identified from the following list (2-3 = mild, 4-5 = moderate, six or more = severe):

- Taking the substance in larger amounts or for longer than the you meant to

- Wanting to cut down or stop using the substance but not managing to

- Spending a lot of time getting, using, or recovering from use of the substance

- Cravings and urges to use the substance

- Not managing to do what you should at work, home or school, because of substance use

- Continuing to use, even when it causes problems in relationships

- Giving up important social, occupational or recreational activities because of substance use

- Using substances again and again, even when it puts the you in danger

- Continuing to use, even when the you know you have a physical or psychological problem that could have been caused or made worse by the substance

- Needing more of the substance to get the effect you want (tolerance)

- Development of withdrawal symptoms, which can be relieved by taking more of the substance (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

The Society of Clinical Psychology website for evidence-based practices lists behavioral marital (couples) therapy as having strong research support for alcohol use disorders. Cognitive therapy and contingency management procedures, in which individuals receive “prizes” for clean laboratory samples, have been effective in treating mixed substance use disorders. A separate website of evidence-based practices for substance use disorders is maintained by the University of Washington Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute (http://adai.uw.edu/ebp/). It lists behavioral self-control training and harm reduction approaches as being effective with adults (including college students) experiencing drinking problems. The Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS) harm reduction approach will be described in the following chapter (Denerin & Spear, 2012; Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1998; Marlatt, 1996; Marlatt, Baer, & Larimer, 1995).

Neurocognitive Disorders

The diagnosis of neurocognitive disorders is based on clinical and behavioral observations made during adulthood. Due to the similarity in names, it is inevitable that neurodevelopmental and neurocognitive disorders will be confused. Although these disorders are both suspected to be the result of impairments in the brain or central nervous system, their effects are at opposite ends of the lifespan and are in opposite directions. Neurodevelopmental disorders, occurring early in life, interfere with normal, age-appropriate cognitive and social development. Neurocognitive disorders are diagnosed later in life when there is deterioration in healthy cognitive functioning impacting on customary daily activities. When deterioration is extreme, as in Alzheimer’s disease, the individual may be unable to maintain an independent lifestyle.

Unlike prior DSM editions, DSM-5 includes the diagnosis of mild as well as severe versions of different neurocognitive disorders based on the underlying medical condition (when known). The listed medical conditions include: Alzheimer’s disease;frontotemporal disorder;disorder with Lewy bodies; vascular disorder;traumatic brain injury; substance or medication-induced disorders; HIV infection; Prion disease; Parkinson’s disease; and Huntington’s disease. The neural and brain damage resulting from the major neurocognitive disorders result in discouraging prognoses and limited to non-existent treatment options. For example, currently existing medications can only slow down, not halt the worsening symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (e.g., severe memory loss). It is not possible to reverse the physical damage and learning-based approaches have not proved effective in improving cognitive functioning.

Paraphilic Disorders

A paraphilia is the experience of intense sexual arousal under non-normative conditions. The DSM-5 diagnosis of paraphilic disorder represents a change from how paraphilia was treated in the past. In prior editions, diagnosis was based on the occurrence of non-normative feelings and actions. The DSM-5 criteria require that, in addition, the feelings and behavior must cause distress or harm to oneself or others. The eight listed disorders include: exhibitionistic disorder (i.e., exposing oneself to strangers), fetishistic disorder (i.e., sexual arousal to unusual objects such as shoes); frotteuristic disorder (i.e., rubbing oneself against another individual without their consent); pedophilic disorder (i.e., sexual attraction to children); sexual masochism disorder (i.e., sexual behavior resulting in bodily harm to oneself); sexual sadism disorder (sexual behavior resulting in bodily harm to another non-consenting individual); transvestic disorder (i.e., sexual arousal resulting from dressing in the clothes of the opposite sex); and voyeuristic disorder (i.e., spying on individuals engaged in private activities).

The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry published guidelines for the biological treatment of paraphilia (Thibaut, De La Barra, Gordon, Cosyns, & Bradford, 2010). The goals of treatment included control of paraphilic fantasies, urges, behaviors, and distress. Cognitive-behavioral therapy was recommended along with six stages of pharmacologic treatment based upon the intensity of the individual’s fantasies, the level of success attained with a less powerful drug, and the risk for potential harm. It has been found that the combination of learning-based procedures and drugs was more effective than either alone (Hall, & Hall, 2007). In extreme instances, it is recommended that drugs or surgery that totally suppresses sexual urges be considered (Thibaut, De La Barra, Gordon, Cosyns, & Bradford, 2010).

Personality Disorders

We have reached the end of the DSM-5 list of psychiatric disorders. To some extent, we can consider the list as progressing from disorders with a strong nature (i.e., underlying genetic) component, such as Down and Fragile X syndromes, to personality disorders that, as described in Chapter 9, are based on nature/nurture interactions. The DSM-5 describes ten specific diagnosable personality disorders divided into three clusters as follows:

Cluster A (odd disorders)

- Paranoid personality disorder: characterized by a pattern of irrational suspicion and mistrust of others, interpreting motivations as malevolent

- Schizoid personality disorder: lack of interest and detachment from social relationships, and restricted emotional expression

- Schizotypal personality disorder: a pattern of extreme discomfort interacting socially, distorted cognitions and perceptions