8.1: Introduction to Price

8.1.1: Defining Price

Price is both the money someone charges for a good or service and what the consumer is willing to give up to receive a good or service.

Learning Objective

Define price and its relationship to cost

Key Points

- When you ask about the cost of a good or service, you’re really asking how much you will have to give up in order to get it.

- For the business to increase value, it can either increase the perceived benefits or reduce the perceived costs. Both of these elements should be considered elements of price.

- Viewing price from the customer’s perspective helps define value — the most important basis for creating a competitive advantage.

- There are two different ways to look at the role price plays in a society; rational man and irrational man.

Key Terms

- bartering system

-

Barter is a medium of exchange by which goods or services are directly exchanged for other goods or services without using a medium of exchange, such as money.

- benefit

-

an advantage, help or aid from something

- value

-

a customer’s perception of relative price (the cost to own and use) and performance (quality)

Example

- Perceived costs are the opposite of the perceived benefits. When finding a gas station that is selling its highest grade for USD 0.06 less per gallon, the customer must consider the 16 mile (25.75 kilometer) drive to get there, the long line, the fact that the middle grade is not available, and heavy traffic. Therefore, inconvenience, limited choice, and poor service are possible perceived costs.

What Is a Price?

Buying something means paying a price. But what exactly is “price? “

- Price is the money charged for a good or service. For example, an item of clothing costs a certain amount of money. Or a computer specialist charges a certain fee for fixing your computer.

- Price is also what a consumer must pay in order to receive a product or service. Price does not necessarily always mean money. Bartering is an exchange of goods or services in return for goods or services. For example, I teach you English in exchange for you teaching me about graphic design.

- Price is the easiest marketing variable to change and also the easiest to copy.

Even though the question, “How much? ” could be phrased as “How much does it cost? ” price and cost are two different things. Whereas the price of a product is what you, the consumer must pay to obtain it, the cost is what the business pays to make it. When you ask about the cost of a good or service, you’re really asking how much will you have to give up to get it.

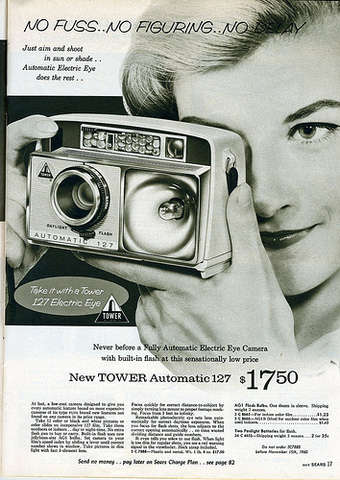

Price

The price is what a consumer pays for a good or service.

Different Perspectives on Price

The perception of price differs based on the perspective from which it is being viewed.

The Customer’s View

A customer can either be the ultimate user of the finished product or a business that purchases components of the finished product. It is the customer that seeks to satisfy a need or set of needs through the purchase of a particular product or set of products. Consequently, the customer uses several criteria to determine how much they are willing to expend, or the price they are willing to pay, in order to satisfy these needs. Ideally, the customer would like to pay as little as possible.

For the business to increase value, it can either increase the perceived benefits or reduce the perceived costs. Both of these elements should be considered elements of price.

To a certain extent, perceived benefits are the opposite of perceived costs. For example, paying a premium price is compensated for by having this exquisite work of art displayed in one’s home. Other possible perceived benefits directly related to the price-value equations are:

- status

- convenience

- the deal

- brand

- quality

- choice

Many of these benefits tend to overlap. For instance, a Mercedes Benz E750 is a very high-status brand name and possesses superb quality. This makes it worth the USD 100,000 price tag. Further, if one can negotiate a deal reducing the price by USD 15,000, that would be his incentive to purchase. Likewise, someone living in an isolated mountain community is willing to pay substantially more for groceries at a local store than drive 78 miles (25.53 kilometers) to the nearest Safeway. That person is also willing to sacrifice choice for greater convenience.

Increasing these perceived benefits are represented by a recently coined term, value-added. Providing value-added elements to the product has become a popular strategic alternative.

Perceived costs include the actual dollar amount printed on the product, plus a host of additional factors. As noted, perceived costs are the mirror-opposite of the benefits. When finding a gas station that is selling its highest grade for USD 0.06 less per gallon, the customer must consider the 16 mile (25.75 kilometer) drive to get there, the long line, the fact that the middle grade is not available, and heavy traffic. Therefore, inconvenience, limited choice, and poor service are possible perceived costs. Other common perceived costs include risk of making a mistake, related costs, lost opportunity, and unexpected consequences.

Ultimately, it is beneficial to view price from the customer’s perspective because it helps define value — the most important basis for creating a competitive advantage.

Society’s View

Price, at least in dollars and cents, has been the historical view of value. Derived from a bartering system (exchanging goods of equal value), the monetary system of each society provides a more convient way to purchase goods and accumulate wealth. Price has also become a variable society employs to control its economic health. Price can be inclusive or exclusive. In many countries, such as Russia, China, and South Africa, high prices for products such as food, health care, housing, and automobiles, means that most of the population is excluded from purchase. In contrast, countries such as Denmark, Germany, and Great Britain charge little for health care and consequently make it available to all.

There are two different ways to look at the role price plays in a society; rational man and irrational man. The former is the primary assumption underlying economic theory, and suggests that the results of price manipulation are predictable. The latter role for price acknowledges that man’s response to price is sometimes unpredictable and pretesting price manipulation is a necessary task.

8.1.2: Terms Used to Describe Price

Depending on whether they are describing a good or a service and the product’s industry, people may use terms other than the word price.

Learning Objective

Name the different terms used to reference pricing

Key Points

- From a customer’s point of view, value is the sole justification for price.

- The price of an item is also called the price point, especially when it refers to stores that set a limited number of price points. The words charge and fee are often used to refer to the price of services.

- The transportation industry charges a fare for its services.

Key Terms

- price point

-

The price of an item, especially seen as one of a number of pricing options.

- price

-

The cost required to gain possession of something.

Example

- Dollar General is a general store or “five and dime” store that sets price points only at even amounts, such as exactly one, two, three, five, or ten dollars (among others).

Introduction

We’ve been using the word “price” a lot. There are, however, other terms you may come across in your studies and daily life that serve as synonyms.

Price Point

The price of an item is also called the price point, especially where it refers to stores that set a limited number of price points.

For example, Dollar General is a general store or “five and dime” store that sets price points only at even amounts, such as exactly one, two, three, five, or ten dollars (among others). Other stores will have a policy of setting most of their prices ending in 99 cents or pence. Other stores (such as dollar stores, pound stores, euro stores, 100-yen stores, and so forth) only have a single price point ($1, £1, 1€, ¥100), though in some cases this price may purchase more than one of some very small items. Price is relatively less than the cost price.

Charge

When someone wants to know the price of a service, they may ask, “How much do you charge? ” In this context, the word “charge” is a synonym for price.

Value

From a customer’s point of view, value is the sole justification for price. Many times customers lack an understanding of the cost of materials and other costs that go into the making of a product. But those customers can understand what that product does for them in the way of providing value. It is on this basis that customers make decisions about the purchase of a product.

Fee

Service providers may present you with a fee list as opposed to a price tag if you ask for the price of their services.

Fare

You pay a price to fly, ride the bus and take the train. The price in these industries is expressed as a fare .

London Bus

A “fare” is the price to ride a bus.

8.1.3: The Importance of Price to Marketers

Since pricing has a direct impact on a company’s revenue, and thus profit, setting the right price is essential to a company’s success.

Learning Objective

Discuss how pricing impacts marketing and business strategy

Key Points

- Price is important to marketers because it represents marketers’ assessment of the value customers see in the product or service and are willing to pay for a product or service.

- Adjusting the price has a profound impact on the marketing strategy, and depending on the price elasticity of the product, it will often affect the demand and sales as well.

- Pricing contributes to how customers perceive a product or a service.

Key Terms

- value

-

a customer’s perception of relative price (the cost to own and use) and performance (quality)

- marketing mix

-

A business tool used in marketing products; often crucial when determining a product or brand’s unique selling point. Often synonymous with the four Ps: price, product, promotion, and place.

Example

- A firm that wants to indicate that it offers products of the highest quality will charge a high price. A high price indicates high quality. The term luxury comes to mind. Louis Vuitton has continued to perform well in the midst of a financial crisis because it offers high quality products and its prices reflect this fact. If, however, a firms wants to position itself as a low-cost provider, it will charge low prices. Just as they do with high-end providers, consumers know what to expect when they see low prices. Someone who goes to a low-cost supermarket, such as Aldi, knows what to expect when he walks into the store.

Pricing and the Marketing Mix

Pricing might not be as glamorous as promotion, but it is the most important decision a marketer can make.

Price is important to marketers because it represents marketers’ assessment of the value customers see in the product or service and are willing to pay for a product or service. The other elements of the marketing mix (product, place and promotion) may seem to be more glamorous than price, and thus get more attention, but determining the price of a product or service is actually one of the most important management decisions. Here’s why.

- While product, place and promotion affect costs, price is the only element that affects revenues, and thus, a business’s profits. Price can lead to a firm’s survival or demise.

- Adjusting the price has a profound impact on the marketing strategy, and depending on the price elasticity of the product, it will often affect the demand and sales as well. Both a price that is too high and one that is too low can limit growth. The wrong price can also negatively influence sales and cash flow.

- Problems occur if the marketer fails to set a price that complements the other elements of the marketing mix and the business objectives, as pricing contributes to how customers perceive a product or a service. A high price indicates high quality. The term luxury comes to mind. If, however, a firm wants to position itself as a low-cost provider, it will charge low prices. Just as they do with high-end providers, consumers know what to expect when they see low prices.

So, as you can see, it is important that a company sets the right price. A company’s success can depend on it. However, with so many factors to consider along with the lack of a crystal ball that will show the effect of a price change, It isn’t so easy to do.

8.1.4: Value and Relative Value

Value is the worth of goods, and relative value is attractiveness measured in terms of utility of one good relative to another.

Learning Objective

Discuss the different concepts of value and how it influences consumer buying decisions

Key Points

- Value is the worth of goods and services as determined by markets.

- Something is only worth what someone is willing to pay for it.

- The utility for the seller is not as an object of usage, but as a source of income.

- In term of pricing, prices of valued items undergo questionable fluctuations.

Key Terms

- Surplus value

-

The part of the new value made by production that is taken by enterprises as generic gross profit.

- marginal utility

-

The additional utility to a consumer from an additional unit of an economic good.

- utility

-

The ability of a commodity to satisfy needs or wants; the satisfaction experienced by the consumer of that commodity.

Example

- Even though housing provides the same utility to the individual over time, and supply and demand are relatively constant and stable, the relative price of housing fluctuates.

What is Value?

Value is the worth of goods and services as determined by markets. Thus, an important part of economics is the study of policies and activities for the generation and transfer of value within markets in the form of goods and services.

Often a measure for the worth of goods and services is units of currency such as the US Dollar. But, unlike the units of measurements in Physics such as seconds for time, there exists no absolute basis for standardizing the units for value.

One of the most complicated and most often misunderstood parts of economy is the concept of value. One of the big problems is the large number of different types of values that seem to exist, such as exchange value, surplus value, and use value.

The Buyer’s Utility

The discussion of values all start with one simple question: What is something worth?

Today’s most common answer is one of those answers that are so deceptively simple that it seems obvious when you know it. But then remember that it took economists more than a hundred years to figure it out: something is worth whatever you think it is worth.

This statement needs some explanation. Take as an example two companies that are thinking of buying a new copying machine. One company does not think they will use a copying machine that much, but the other knows it will copy a lot of papers. This second company will be prepared to pay more for a copying machine than the first one. They find a greater utility in the object.

The companies also have a choice of models. The first company knows that many of the papers will need to be copied on both sides. The second company knows that very few of the papers it copies will need double- sided copying. Of course, the second company will not pay much more for this feature, while the first company will. In this example, we see that a buyer will be prepared to pay more for the increase in utility compared to alternative products.

So we can summarize this with the statement that the economic value of an item is set by the increase in utility for customers. This increase in utility is called marginal utility, and this is all known as the marginal theory of value.

The Seller’s Utility

But how does the seller value things? Well, in pretty much the same way. Of course, most sellers today do not intend to use the object he sells himself. The utility for the seller is not as an object of usage, but as a source of income. And here again it is marginal utility that comes in. For what price can you sell the object? If you put in some more work, can you get a higher price?

Here we also get into the utility for resellers. Somebody who deals in trading will look at an object, and the utility for him is to be able to sell it again. How much work will it take, and what margins are possible?

Subjective Value

Not only do the two different buyers have a different value on an object, the salesman puts his value on it, and the original manufacturer may have put yet another value on it. The value depends on the person who does the valuation–it is subjective.

Relative Value and Pricing

Relative value in the marketing context is attractiveness measured in terms of utility of one product relative to another.

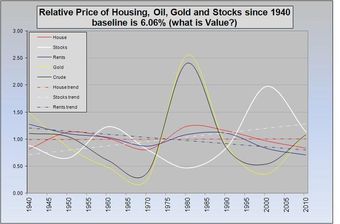

In term of pricing, prices of valued items undergo questionable fluctuations. For example, even though housing provides the same utility to the individual over time, and supply and demand are relatively constant and stable, the relative price of housing fluctuates, even more so than with stocks, oil, and gold.

This price volatility appears to occur in cycles and is caused by a myriad of factors. Figure 1 is an attempt to overlay the prices of housing, stocks, oil, and gold by normalizing the price streams. Normalizing is achieved by applying a discounting formula which converts a price to the price it would be at a certain date, given a certain discount rate. This would normally be used to cancel the effects of inflation, in which case the inflation rate would be used.

Value or Price

This chart shows that commonly valued items of constant utility tend to vary in price over time.

8.2: Competitive Dynamics and Pricing

8.2.1: Price Competition

With competition pricing, a firm will base what they charge on what other firms are charging.

Learning Objective

Discuss price as a competitive strategy in marketing

Key Points

- Price is a very important decision criteria that customers use to compare alternatives. It also contributes to the company’s position.

- The pricing process normally begins with a decision about the company’s pricing approach to the market.

- In general, a business can price itself to match its competition, price higher, or price lower.

Key Terms

- competitor

-

A person or organization against whom one is competing.

- strategy

-

a plan of action intended to accomplish a specific goal

- price war

-

Price war is a term used in the economic sector to indicate a state of intense competitive rivalry accompanied by a multi-lateral series of price reductions. One competitor will lower its price, then others will lower their prices to match. If one of them reduces their price again, a new round of reductions starts.

- off-price retailer

-

firms that purchase goods below wholesale cost and sell below normal retail price

Example

- Many organizations attempt to establish prices that, on average, are the same as those set by their more important competitors. Automobiles of the same size that feature equivalent equipment tend to have similar prices.

Price Competition

Once a business decides to use price as a primary competitive strategy, there are many well-established tools and techniques that can be employed. The pricing process normally begins with a decision about the company’s pricing approach to the market.

Approaches to the Market

Price is a very important decision criteria that customers use to compare alternatives. It also contributes to the company’s position. In general, a business can price itself to match its competition, price higher, or price lower. Each has its pros and cons.

Pricing to Meet Competition

Many organizations attempt to establish prices that, on average, are the same as those set by their more important competitors. Automobiles of the same size that feature equivalent equipment tend to have similar prices. This strategy means that the organization uses price as an indicator or baseline. Quality in production, better service, creativity in advertising, or some other element of the marketing mix are used to attract customers who are interested in products in a particular price category.

The keys to implementing a strategy of meeting competitive prices are an accurate definition of competition and a knowledge of competitor’s prices. A maker of hand-crafted leather shoes is not in competition with mass producers. If this artisan attempts to compete with mass producers on price, higher production costs will make the business unprofitable. A more realistic definition of competition for this purpose would be other makers of hand-crafted leather shoes. After defining this competition, knowing their prices would allow the artisan to put this pricing strategy into effect. Banks shop with competitive banks every day to check their prices.

Pricing Above Competitors

Pricing above competitors can be rewarding to organizations, provided that the objectives of the policy are clearly understood. The marketing mix must also be used to develop a strategy that enables management to implement the policy successfully.

Pricing above competition generally requires a clear advantage on some nonprice element of the marketing mix. In some cases, it is possible due to a high price-quality association on the part of potential buyers. Such an assumption is increasingly dangerous in today’s information-rich environment. Consumer Reports and other similar publications make objective product comparisons much simpler for the consumer. There are also hundreds of dot.com companies that provide objective price comparisons. The key is to prove to customers that your product justifies a premium price.

Pricing Below Competitors

While some firms are positioned to price above competition, others wish to carve out a market niche by pricing below competitors. The goal of such a policy is to realize a large sales volume through a lower price. By controlling costs and reducing services, these firms are able to earn an acceptable profit, even though profit per unit is usually less.

Such a strategy can be effective if a significant segment of the market is price-sensitive and or the organization’s cost structure is lower than competitors. Costs can be reduced by increased efficiency, economies of scale, or by reducing or eliminating such things as credit, delivery, and advertising. For example, if a firm could replace its sales force in the field with telemarketing or online access, this function might be performed at a lower cost. Such reductions often involve some loss in effectiveness, so the tradeoff must be considered carefully.

Historically, one of the worst outcomes that can result from pricing lower than a competitor is a price war. Price wars usually occur when a business believes that price-cutting produces increased market share, but does not have a true cost advantage. Price wars are often caused by companies misreading or misunderstanding competitors. Typically, price wars are overreactions to threats that either are not there at all or are not as big as they seem.

Another possible drawback when pricing below competition is the company’s inability to raise price or image. A retailer such as Kmart, known as a discount chain, found it impossible to reposition itself as a provider of designer women’s clothes. In keeping with this idea, can you imagine Swatch selling a 3,000 dollar watch?

Kmart

Kmart had a hard time selling upscale items because it’s known as a discount chain.

How can companies cope with the pressure created by reduced prices? Some are redesigning products for ease and speed of manufacturing or reducing costly features that their customers do not value. Other companies are reducing rebates and discounts in favor of stable, everyday low prices (ELP). In all cases, these companies are seeking shelter from pricing pressures that come from the discount mania that has been common in the US for the last two decades.

8.2.2: Nonprice Competition

Non-price competition involves firms distinguishing their products from competing products on the basis of attributes other than price.

Learning Objective

Differentiate price competition from non-price competition tactics

Key Points

- Non-price competition can be contrasted with price competition, which is where a company tries to distinguish its product or service from competing products on the basis of a low price.

- Firms will engage in non-price competition, in spite of the additional costs involved, because it is usually more profitable than selling for a lower price and avoids the risk of a price war.

- Although any company can use a non-price competition strategy, it is most common among oligopolies and monopolistic competition, because these firms can be extremely competitive.

Key Terms

- oligopolies

-

An oligopoly is a market form in which a market or industry is dominated by a small number of sellers (oligopolists). Because there are few sellers, each oligopolist is likely to be aware of the actions of the others.

- generic

-

Not having a brand name.

Example

- Common practices in the competition between firms (such as supermarkets and other stores) include the following: traditional advertising and marketing, store loyalty cards, banking and other services (including travel insurance), in-store chemists and post offices, home delivery systems, discounted petrol at hypermarkets, extension of opening hours (24 hour shopping), innovative use of technology for shoppers including self-scanning, and internet shopping services.

Introduction

Since price competition can only go so far, firms often engage in non-price competition. Non-price competition is a marketing strategy “in which one firm tries to distinguish its product or service from competing products on the basis of attributes like design and workmanship. “

The firm can also distinguish its product offering through quality of service, extensive distribution, customer focus, or any other sustainable competitive advantage other than price.

Non-price Competition

Amazon.com makes shopping and researching products, prices, and seller reliability quick and easy for its customers. Its prices are low, but not necessarily the lowest.

The idea is to try to convince consumers that they should buy these products, not just because they are cheaper, but because they are in some way better than those made by competitors.

It can be contrasted with price competition, which is where a company tries to distinguish its product or service from competing products on the basis of a low price.

The Benefits of Non-price Compeition

Non-price competition typically involves promotional expenditures (such as advertising, selling staff, the locations convenience, sales promotions, coupons, special orders, or free gifts), marketing research, new product development, and brand management costs.

Firms will engage in non-price competition, in spite of the additional costs involved, because it is usually more profitable than selling for a lower price and avoids the risk of a price war. For example, brand-name goods often sell more units than do their generic counterparts, despite usually being more expensive. Non-price competition may also promote innovation as firms try to distinguish their product.

Although any company can use a non-price competition strategy, it is most common among oligopolies and monopolistic competition, because these firms can be extremely competitive.

8.3: Demand Analysis

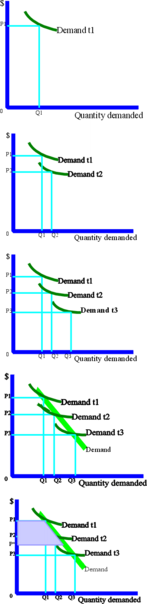

8.3.1: The Demand Curve

A demand curve is a graph showing the relationship between the price of a certain item and what consumers are willing to buy at the price.

Learning Objective

Define the demand curve

Key Points

- Demand does not only have to do with the need to have a product or a service, but it also involves the willingness and ability to buy it at the price charged for it.

- The demand curve for all consumers together follows from the demand curve of every individual consumer. The individual demands at each price are added together.

- The negative slope of the demand curve is often referred to as the “law of demand,” which means people will buy more of a service, product, or resource as its price falls.

Key Terms

- derived demand

-

when demand for a factor of production or intermediate good occurs as a result of the demand for another intermediate or final good

- Giffen good

-

A good which people consume more of as the price rises; Having a positive price elasticity of demand. As price rises, more is consumed which increases demand.

- Veblen good

-

A good for which people’s preference for buying them increases as a direct function of their price, as greater price confers greater status. As the price gets higher, demand rises.

- straight rebuy

-

the repurchase of a good with no changes to the details of the order

Example

- Demand is the willingness and ability of a consumer to purchase a good under the prevailing circumstances. Thus, any circumstance that affects the consumer’s willingness or ability to buy the good or service in question can be a non-price determinant of demand. For example, weather could effect the demand for beer at a baseball game.

Demand

When clients want a product and are willing to pay for it, we say that there is a demand for the specific product. There has to be a demand for a product before a manufacturer can sell it. Demand does not only have to do with the need to have a product or a service, but also with the willingness and ability to buy it at the price charged for it.

Example of Demand: Andrew’s Grape Jam

Andrew and his mother, Mrs. Jeffries, decided to earn extra money by selling grape jam at the local craft market. Mrs. Jeffries would buy the ingredients and make the jam. Andrew would help his mother seal it in jars and they planned to sell it at the market on Saturday mornings.

Before starting to boil the jam, they decided to test the market to see whether people would be interested in buying their product. Mrs. Jeffries therefore boiled a few jars of jam and asked their friends and family if they were interested in buying it and how much they would be willing to pay for it. Everyone was encouraged to taste some of the jam before making a decision.

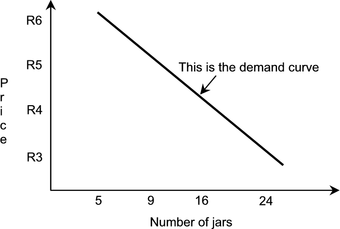

The results Mrs. Jeffries received is are illustrated in the graph which indicates the demand at different prices.

Demand Curve

This graph shows the demand curve based on the number of jars and the price.

The line on the graph indicates the way in which the change in price brought about a change in demand. This is referred to as the demand curve. It specifies the amount of a product according to the demands for it at a specific price.

Demand Curve

In economics, the demand curve is the graph depicting the relationship between the price of a certain commodity (in this case Andrew’s jam) and the amount of it that consumers are willing and able to purchase at that given price. It is a graphic representation of a demand schedule.

The demand curve for all consumers together follows from the demand curve of every individual consumer: the individual demands at each price are added together.

Demand Curve Characteristics

According to convention, the demand curve is drawn with price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis. The demand curve usually slopes downwards from left to right; that is, it has a negative association (two theoretical exceptions, Veblen good and Giffen good). The negative slope is often referred to as the “law of demand”, which means people will buy more of a service, product, or resource as its price falls.

Linear Demand Curve

The demand curve is often graphed as a straight line in the form Q = a – bP where “a” and “b” are parameters. The constant “a” “embodies” the effects of all factors, other than price, that affect demand.

If income were to change, for example, the effect of the change would be represented by a change in the value of “a” and be reflected graphically as a shift on the demand curve. The constant “b” is the slope of the demand curve and shows how the price of the good affects the quantity demanded.

The graph of the demand curve uses the inverse demand function in which price is expressed as a function of quantity. The standard form of the demand equation can be converted to the inverse equation by solving for P or P = a/b – Q/b.

Shift of a Demand Curve

The shift of a demand curve takes place when there is a change in any non-price determinant of demand, resulting in a new demand curve.

Non-price determinants of demand are those things that cause demand to change even if prices remain the same—in other words, changes that might cause a consumer to buy more or less of a good even if the good’s price remained unchanged.

Some of the more important factors are:

- the prices of related goods (both substitutes and complements)

- income

- population

- expectations

However, demand is the willingness and ability of a consumer to purchase a good under the prevailing circumstances. Thus, any circumstance that affects the consumer’s willingness or ability to buy the good or service in question can be a non-price determinant of demand. For example, weather could effect the demand for beer at a baseball game.

8.3.2: The Influence of Supply and Demand on Price

Changes in either supply or demand will move the market clearing point and change the market price for a good.

Learning Objective

Apply the basic laws of supply and demand to different economic scenarios

Key Points

- There are four basic laws of supply and demand.

- Since determinants of supply and demand other than the price of the good in question are not explicitly represented in the supply-demand diagram, changes in the values of these variables are represented by moving the supply and demand curves (often described as “shifts” in the curves).

- Responses to changes in the price of the good are represented as movements along unchanged supply and demand curves.

Key Term

- equilibrium price

-

The price of a commodity at which the quantity that buyers wish to buy equals the quantity that sellers wish to sell.

Example

- Consider a certain commodity, such as gasoline. If there is a strong demand for gas, but there is less gasoline, then the price goes up. If conditions change and there is a smaller demand for gas, due to the presence of more electric cars for instance, then the price of the commodity decreases.

Introduction

The amount of a good in the market is the supply and the amount people want to buy is the demand. Consider a certain commodity, such as gasoline. If there is a strong demand for gas, but there is less gasoline, then the price goes up. If conditions change and there is a smaller demand for gas, due to the presence of more electric cars for instance, then the price of the commodity decreases.

The factors influencing supply include:

- Price – As the price of a product rises, its supply rises because producers are more willing to manufacture the product because it’s more profitable.

- Price of other commodities – There are two types: competitive supply (If a producer switches from producing A to producing B, the price of A will fall and hence the supply will fall because it’s less profitable to make A), and joint supply (A rise in one product may cause a rise in another. For instance, a rise in the price of wooden bedframes may cause a rise in the price of wooden desks and chairs. This means supply of wooden bedframes, chairs, and desks will rise because it’s more profitable. )

- Costs of production – If production costs rise, supply will fall because the manufacture of the product in question will become less profitable.

- Change in availability of resources – If wood becomes scarce, fewer wooden bedframes can be made, so supply will fall.

Factors influencing demand include:

- Income

- Tastes and preferences

- Prices of related goods and services

- Consumers’ expectations about future prices and incomes that can be checked

- Number of potential consumers

Supply and Demand As an Economic Model

Supply and demand is an economic model of price determination in a market. It concludes that in a competitive market, the unit price for a particular good will vary until it settles at a point where the quantity demanded by consumers (at current price) will equal the quantity supplied by producers (at current price). This results in an economic equilibrium of price and quantity.

The four basic laws of supply and demand are:

- If demand increases and supply remains unchanged, then it leads to higher equilibrium price and higher quantity.

- If demand decreases and supply remains unchanged, then it leads to lower equilibrium price and lower quantity.

- If demand remains unchanged and supply increases, then it leads to lower equilibrium price and higher quantity.

- If demand remains unchanged and supply decreases, then it leads to higher equilibrium price and lower quantity.

Graphical Representation of Supply and Demand

Although it is normal to regard the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied as functions of the price of the good, the standard graphical representation, usually attributed to Alfred Marshall, has price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis, the opposite of the standard convention for the representation of a mathematical function.

Since determinants of supply and demand other than the price of the good in question are not explicitly represented in the supply-demand diagram, changes in the values of these variables are represented by moving the supply and demand curves (often described as “shifts” in the curves). By contrast, responses to changes in the price of the good are represented as movements along unchanged supply and demand curves.

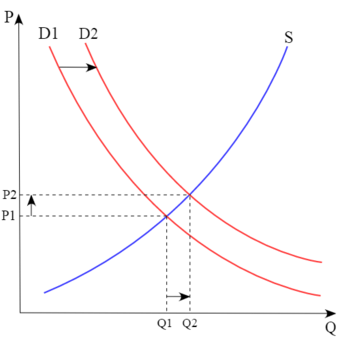

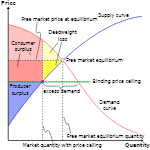

Supply and Demand

The price P of a product is determined by a balance between production at each price (supply S) and the desires of those with purchasing power at each price (demand D).

The diagram shows a positive shift in demand from D1 to D2, resulting in an increase in price (P) and quantity sold (Q) of the product.

Equilibrium

Since the demand curve slopes down and the supply curve slopes up, when they are put on the same graph, they eventually cross one another. The point where the supply line and the demand line meet is called the equilibrium point.

In general, for any good, it is at this point that quantity supplied equals quantity demanded at a set price. If there are more buyers than there are sellers at a certain price, the price will go up until either some of the buyers decide they are not interested, or some people who were previously not considering selling decide that they want to sell their good. This process normally continues until there are sufficiently few buyers and sufficiently many sellers that the numbers balance out, which should happen at the equilibrium point.

8.3.3: Elasticity of Demand

Elasticity of demand is a measure used in economics to show the responsiveness of the quantity demanded of an item to a change in its price.

Learning Objective

Identify the key factors that determine the elasticity of demand for a good

Key Points

- Price elasticities are almost always negative; only goods which do not conform to the law of demand, such as a Veblen good and a Giffen good, have a positive PED.

- In general, the demand for a good is said to be inelastic (or relatively inelastic) when changes in price have a relatively small effect on the quantity of the good demanded.

- The demand for a good is said to be elastic (or relatively elastic) when changes in price have a relatively large effect on the quantity of a good demanded.

- A number of factors can thus affect the elasticity of demand for a good.

Key Terms

- Giffen good

-

A good which people consume more of as the price rises; Having a positive price elasticity of demand. As price rises, more is consumed which increases demand.

- conjoint analysis

-

Conjoint analysis is a statistical technique used in market research to determine how people value different features that make up an individual product or service.

- Veblen good

-

A good for which people’s preference for buying them increases as a direct function of their price, as greater price confers greater status. As the price gets higher, demand rises.

Example

- In general, the more substitues there are for a product, the more elastic it is. For instance, one can get their morning juice from products other than cranberry juice. So if the price of cranberry juice were to increase by $0.25 people would drink a substitute, like apple juice, instead. Cranberry juice, therefore, is an elastic good because a change in price will cause large decrease in demand.

Elasticity of Demand: an Overview

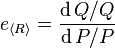

Price elasticity of demand (PED or Ed) is a measure used in economics to show the responsiveness, or elasticity, of the quantity demanded of a good or service to a change in its price.

More precisely, it gives the percentage change in quantity demanded in response to a one percent change in price (holding constant all the other determinants of demand, such as income). It was devised by Alfred Marshall.

Elasticity of Demand

The price elasticity of demand equation shows how the demand for a good or service changes based on the price.

Price elasticities are almost always negative, although analysts tend to ignore the sign even though this can lead to ambiguity. Only goods which do not conform to the law of demand, such as a Veblen good and a Giffen good, have a positive PED.

In general, the demand for a good is said to be inelastic (or relatively inelastic) when the PED is less than one (in absolute value): that is, changes in price have a relatively small effect on the quantity of the good demanded.

The demand for a good is said to be elastic (or relatively elastic) when its PED is greater than one (in absolute value): that is, changes in price have a relatively large effect on the quantity of a good demanded.

Revenue is maximized when price is set so that the PED is exactly one. The PED of a good can also be used to predict the incidence (or “burden”) of a tax on that good. Various research methods are used to determine price elasticity, including test markets, analysis of historical sales data, and conjoint analysis.

Determinants

The overriding factor in determining PED is the willingness and ability of consumers after a price change to postpone immediate consumption decisions concerning the good and to search for substitutes (“wait and look”). A number of factors can thus affect the elasticity of demand for a good:

- Availability of substitute goods: The more and closer the substitutes available, the higher the elasticity is likely to be, as people can easily switch from one good to another if an even minor price change is made. In other words, there is a strong substitution effect. If no close substitutes are available, the substitution of effect will be small and the demand inelastic.

- Breadth of definition of a good: The broader the definition of a good (or service), the lower the elasticity. For example, Company X’s fish and chips would tend to have a relatively high elasticity of demand if a significant number of substitutes are available, whereas food in general would have an extremely low elasticity of demand because no substitutes exist.

- Percentage of income: The higher the percentage of the consumer’s income that the product’s price represents, the higher the elasticity tends to be, as people will pay more attention when purchasing the good because of its cost. The income effect is thus substantial. When the goods represent only a negligible portion of the budget, the income effect will be insignificant and demand inelastic.

- Necessity: The more necessary a good is, the lower the elasticity, as people will attempt to buy it no matter the price, such as in the case of insulin for those that need it.

- Duration: For most goods, the longer a price change holds, the higher the elasticity is likely to be, as more and more consumers find they have the time and inclination to search for substitutes. When fuel prices increase suddenly, for instance, consumers may still fill up their empty tanks in the short run, but when prices remain high over several years, more consumers will reduce their demand for fuel by switching to carpooling or public transportation, investing in vehicles with greater fuel economy, or taking other measures. This does not hold for consumer durables such as the cars themselves, however; eventually, it may become necessary for consumers to replace their present cars, so one would expect demand to be less elastic.

- Brand loyalty: An attachment to a certain brand—either out of tradition or because of proprietary barriers—can override sensitivity to price changes, resulting in more inelastic demand.

- Who pays: Where the purchaser does not directly pay for the good they consume, such as with corporate expense accounts, demand is likely to be more inelastic.

8.3.4: Yield Management Systems

Yield management systems enable organizations to adapt pricing in real-time based on various factors impacting demand.

Learning Objective

Understand the purpose of projecting demand changes, and varying prices to capture opportunities

Key Points

- Yield management systems are predicated on the idea that demand is not consistent over time for certain types of products and services. Predicting shifts in demand will therefore provide potential value to the organization.

- By accurately predicting changes in demand over time or over consumer groups, organizations can produce a profit-maximizing pricing strategy through varying price points with demand.

- Yield management is a multidisciplinary field, which requires buy in from financiers, accountants, marketers, strategists and often technical specialists in big data.

- Knowing when to use yield management and when not to is an important strategic decision. Goods that are perishable, scarce, and which have a high fluctuation in willingness to pay are ideal for this model.

- There are ethical concerns revolving around yield management however, as charging individuals based on their ability to pay and overall demand could be as exploitation.

Key Term

- yield management

-

The marketing strategy of identifying variance in demand, and aligning pricing strategies to maximizing profits.

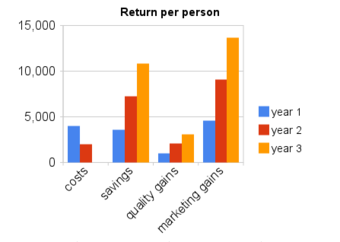

Estimating Demand

When an organization begins determining the price of a given product or service, the objective is to optimize profit through maximizing revenues and minimizing cost. To do so, projections of demand and fulfilling that projected demand with the appropriate supply to maintain the optimal price point is a central strategic endeavor for a marketer. Forecasting demand and understanding the elasticity of the demand for various types of goods is greatly empowered by systems built to manage yield.

Demand Shifts

Understanding fluctuations in demand is a critical component of yield management systems.

Yield Management Systems

A yield management system is based on pricing models which are variable, which is to say that the price of a given product or service will change consistently over time. A good example of this, just as a frame of reference, would be a flight ticket. The prices for a flight from city A to city B will be different per day, per time, per airline and even per website in which you are finding that ticket. This variable pricing model is designed to maximize revenue through identifying supply, demand and optimal yield.

When To Manage Yield

Yield management is quite a complex endeavor, as it takes into account multidisciplinary considerations such as marketing, operations, financial management, statistics, and strategy to build an optimized approach to pricing which iterates and evolves over time. As a result, it is only worth building into practice when it will generate significant returns.

Yield management functions best when the following conditions are met:

- There are a fixed amount of a given resource available (i.e. scarcity)

- The resources are perishable, or time-sensitive in some way

- There is a relatively high amount of fluctuation in regards to what consumers are willing to pay

Combining these three factors, we have scarce products which will likely expire and which are valued differently by different consumers. In these situations, managing yield through pricing properly based on timing and user can optimize profits.

Big Data

Effective yield management, like most intensive research projects, are best left to computers. Machine learning and the capacity to process large data streams (i.e. big data) can create highly reliable statistical models and segmentation of markets to enable an organization to target the appropriate consumer groups with the appropriate price at the appropriate time. This is generally accomplished through building forecasts utilizing huge data streams of past user behaviors.

For example, the price of a flight on a given day can take into account he day of the week, time of year, inflation, market conditions, competitive current pricing, and a wide variety of other data points in order to create a statistical spread of what the price should be set at.

Ethical Concerns

Yield management systems are very useful in specific industries, but are also somewhat controversial. The criticism of yield management is fairly intuitive. If companies can set prices based upon what type of consumer you are, and can identify demand with great accuracy, it is fairly easy for organizations to exploit consumers in specific situations.

For example, say you are stranded in a foreign country after flight cancellations, and need to get home to your two young children. You are there on business, and have an upper-middle class salary. A machine with all of that information can accurately predict that you are willing to pay a great deal more than someone else due to your dire situation. It would not be inaccurate to point out that this is somewhat predatory, and therefore potentially unethical behavior. You may pay thousands for the seat, while the person next to you paid less than 10% of what you paid.

8.4: Inputs to Pricing Decisions

8.4.1: Marginal Analysis

Pricing decisions tend to heavily involve analysis regarding marginal contributions to revenues and costs.

Learning Objective

Identify the characteristics of a marginal price analysis relative to pricing decision making

Key Points

- Firms tend to accomplish their objective of profit maximization by increasing their production until marginal revenue equals marginal cost.

- At the output level at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost, marginal profit is zero and this quantity is the one that maximizes profit.

- In some cases, a firm’s demand and cost conditions are such that marginal profits are greater than zero for all levels of production up to a certain maximum; thus, output should be produced at the maximum level.

Key Terms

- demand curve

-

The graph depicting the relationship between the price of a certain commodity and the amount of it that consumers are willing and able to purchase at that given price.

- game theory

-

A branch of applied mathematics that studies strategic situations in which individuals or organizations choose various actions in an attempt to maximize their returns.

Marginal Analysis

Pricing decisions tend to heavily involve analysis regarding marginal contributions to revenues and costs. Specifically, firms tend to accomplish their objective of profit maximization by increasing their production until marginal revenue equals marginal cost, and then charging a price which is determined by the demand curve.

In business, the practice of setting the price of a product to equal the extra cost of producing an extra unit of output is known as marginal-cost pricing. Businesses often set prices close to marginal cost during periods of poor sales. If, for example, an item has a marginal cost of $1.00 and a normal selling price of $2.00 the firm selling the item might wish to lower the price to $1.10 if demand has waned. The business would choose this approach because the incremental profit of 10 cents from the transaction is better than no sale at all.

In the marginal analysis of pricing decisions, if marginal revenue is greater than marginal cost at some level of output, marginal profit is positive and thus a greater quantity should be produced. Alternatively, if marginal revenue is less than the marginal cost, marginal profit is negative and a lesser quantity should be produced. At the output level at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost, marginal profit is zero and this quantity is the one that maximizes profit.

Since total profit increases when marginal profit is positive and total profit decreases when marginal profit is negative, it must reach a maximum where marginal profit is zero.

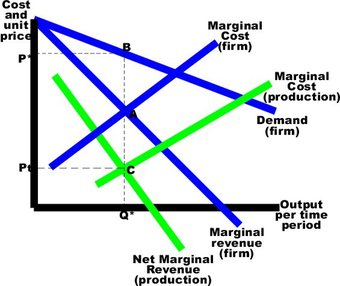

The intersection of MR and MC is shown as point A. If the industry is perfectly competitive (as is assumed in the diagram), the firm faces a demand curve (D) that is identical to its marginal revenue curve (MR). Thus, this is a horizontal line at a price determined by industry supply and demand. If the firm is operating in a non-competitive market, changes would have to be made to the diagram.

Marginal Profit Maximization

This series of cost curves shows the implementation of profit maximization using marginal analysis.

For example, the marginal revenue curve would have a negative gradient, due to the overall market demand curve. In a non-competitive environment, more complicated profit maximization solutions involve the use of game theory. In some cases, a firm’s demand and cost conditions are such that marginal profits are greater than zero for all levels of production up to a certain maximum. In this case, marginal profit plunges to zero immediately after that maximum is reached. Thus, output should be produced at the maximum level, which also happens to be the level that maximizes revenue. In other words, the profit maximizing quantity and price can be determined by setting marginal revenue equal to zero, which occurs at the maximal level of output.

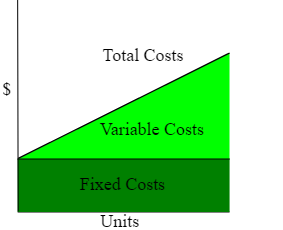

8.4.2: Fixed Costs

Fixed costs are business expenses that are not dependent on the level of goods or services produced by the business.

Learning Objective

Describe the characteristics of fixed costs and they relate to pricing decisions

Key Points

- The distinction between fixed and variable costs is crucial in forecasting the earnings generated by various changes in unit sales and thus the financial impact of proposed marketing campaigns.

- Fixed costs are not permanently fixed – they will change over time – but are fixed in relation to the quantity of production for the relevant period.

- Average fixed cost (AFC) is an economic term that refers to fixed costs of production (FC) divided by the quantity (Q) of output produced.

Key Terms

- lease

-

A contract granting use or occupation of property during a specified period in exchange for a specified rent.

- discretionary

-

Available at one’s discretion; able to be used as one chooses; left to or regulated by one’s own discretion or judgment.

Fixed Costs

Determining the cost of producing a product or service plays a vital role in most pricing decisions. Fixed costs are business expenses that are not dependent on the level of goods or services produced by the business. They tend to be time-related, such as salaries or rents being paid per month. They and are often referred to as overhead costs. This is in contrast to variable costs, which are volume-related and are paid per quantity produced. In management accounting, fixed costs are defined as expenses that do not change as a function of the activity of a business, within the relevant period. For example, a retailer must pay rent and utility bills irrespective of sales. In marketing, it is necessary to know how costs divide between variable and fixed. This distinction is crucial in forecasting the earnings generated by various changes in unit sales and thus the financial impact of proposed marketing campaigns. In a survey of nearly 200 senior marketing managers, 60% responded that they found the “variable and fixed costs” metric very useful.

Fixed Costs and Variable Costs

The graph breaks down the difference between fixed costs and variable costs.

Fixed costs are not permanently fixed – they will change over time – but are fixed in relation to the quantity of production for the relevant period. For example, a company may have unexpected and unpredictable expenses unrelated to production. Warehouse costs and the like are fixed only over the time period of the lease. By definition, there are no fixed costs in the long run. Investments in facilities, equipment, and the basic organization that can’t be significantly reduced in a short period of time are referred to as committed fixed costs. Discretionary fixed costs usually arise from annual decisions by management to spend on certain fixed cost items. Examples of discretionary costs are advertising, machine maintenance, and research and development expenditures.

Average Fixed Costs

For pricing purposes, marketers generally take into account average fixed costs. Average fixed cost (AFC) is an economics term that refers to fixed costs of production (FC) divided by the quantity (Q) of output produced . Average fixed cost is a per-unit-of-output measure of fixed costs. As the total number of goods produced increases, the average fixed cost decreases because the same amount of fixed costs is being spread over a larger number of units of output.

8.4.3: Break-Even Analysis

The break-even point is the point at which costs and revenues are equal.

Learning Objective

Analyze the concept of break even points relative to pricing decisions

Key Points

- In the linear Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis model, the break-even unit of sales can be directly computed in terms of total revenue and total costs.

- Unit contribution margin is the marginal profit per unit, or alternatively the portion of each sale that contributes to fixed costs.

- Break-even analysis is a simple and useful analytical tool, yet has a number of limitations as well.

Key Terms

- break-even point

-

The point where total costs equal total revenue and the organization neither makes a profit nor suffers a loss.

- Opportunity Costs

-

The costs of activities measured in terms of the value of the next best alternative forgone (that is not chosen).

Break-Even Analysis

In economics and business, specifically cost accounting, the break-even point is the point at which costs or expenses and revenue are equal – i.e., there is no net loss or gain, and one has “broken even.”

A profit or a loss has not been made, although opportunity costs have been “paid,” and capital has received the risk-adjusted, expected return. For example, if a business sells fewer than 200 tables each month, it will make a loss. If the business sells more, it will make a profit. With this information, the business managers will then need to see if they expect to be able to make and sell 200 tables per month. If they think they cannot sell that many, to ensure viability they could:

- Try to reduce the fixed costs (by renegotiating rent for example, or keeping better control of telephone bills or other costs)

- Try to reduce variable costs (the price it pays for the tables by finding a new supplier)

- Increase the selling price of their tables

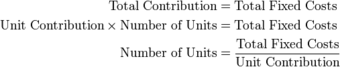

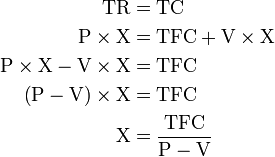

In the linear Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis model, the break-even point – in terms of Unit Sales (X) – can be directly computed in terms of Total Revenue (TR) and Total Costs (TC) as: where TFC is Total Fixed Costs, P is Unit Sale Price, and V is Unit Variable Cost. The quantity (P – V) is of interest in its own right, and is called the Unit Contribution Margin (C). It is the marginal profit per unit, or alternatively the portion of each sale that contributes to Fixed Costs. Thus the break-even point can be more simply computed as the point where Total Contribution = Total Fixed Cost:

Break-Even Analysis

A break-even quantity can also be found using contribution margin.

Break-Even Calculation

We can derive the calculation for the break-even quantity from the relation of total revenue to total costs.

Break-Even and Pricing Decisions

The break-even point is one of the simplest analytical tools in management. It helps to provide a dynamic view of the relationships between sales, costs, and profits. A better understanding of break-even, for example, is expressing break-even sales as a percentage of actual sales. This can give managers a chance to understand when to expect to break even (by linking the percent to when in the week/month this percent of sales might occur). In terms of pricing decisions, break-even analysis can give a company a benchmark quantity of goods to be sold. This quantity can then be used to derive the average fixed and variable costs, the sum of which can be used as the basis for markup pricing, et cetera. Some limitations of break-even analysis include:

- It is only a supply side (i.e. costs only) analysis, as it tells you nothing about what sales are actually likely to be for the product at these various prices.

- It assumes that fixed costs (FC) are constant. Although this is true in the short run, an increase in the scale of production is likely to cause fixed costs to rise.

- It assumes average variable costs are constant per unit of output, at least in the range of likely quantities of sales (i.e. linearity).

- It assumes that the quantity of goods produced is equal to the quantity of goods sold.

- In multi-product companies, it assumes that the relative proportions of each product sold and produced are constant (i.e., the sales mix is constant).

8.4.4: Organizational Objectives

For the vast majority of business entities, the ultimate objective should be to increase profits, often through a better pricing strategy.

Learning Objective

Illustrate how an organization’s objectives impact its pricing decisions

Key Points

- A business can cut its costs, it can sell more, or it can find more profit with a better pricing strategy.

- When costs are already at their lowest and sales are hard to find, adopting a better pricing strategy is a key option to stay viable.

- A pivotal factor in determining a price is how consumers will perceive it.

Key Term

- viable

-

Able to be done, possible.

Organizational Objectives

For the vast majority of business entities, the ultimate objective should be to increase profits. Pricing strategies for products or services encompass three main ways to achieve this. A business can cut its costs, it can sell more, or it can find more profit with a better pricing strategy.

When costs are already at their lowest and sales are hard to find, adopting a better pricing strategy is a key option to stay viable. Merely raising prices is not always the answer, especially in a poor economy. Too many businesses have been lost because they priced themselves out of the marketplace. On the other hand, too many business and sales staff leave “money on the table. ” The objective is to adopt a pricing strategy and manage costs such that profit will be maximized.

One strategy does not fit all, so adopting a pricing strategy is a learning curve when studying the needs and behaviors of customers and clients.

Laws Of Price Sensitivity

A pivotal factor in determining a price is how consumers will perceive it. In their book,The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing, Thomas Nagle and Reed Holden outline nine “laws” that influence how a consumer perceives a given price and how price-sensitive they are likely to be with respect to different purchase decisions. They are:

- Reference price effect – The buyer’s price sensitivity for a given product increases the higher the product’s price relative to perceived alternatives. Perceived alternatives can vary by buyer segment, by occasion, and other factors.

- Difficult comparison effect – Buyers are less sensitive to the price of a known or more reputable product when they have difficulty comparing it to potential alternatives.

- Switching costs effect – The higher the product-specific investment a buyer must make to switch suppliers, the less price sensitive that buyer is when choosing between alternatives.

- Price-quality effect – Buyers are less sensitive to price the more that higher prices signal higher quality. Products for which this effect is particularly relevant include: image products, exclusive products, and products with minimal cues for quality.

- Expenditure effect – Buyers are more price sensitive when the expense accounts for a large percentage of buyers’ available income or budget.

- End-benefit effect – This effect refers to the relationship a given purchase has to a larger overall benefit and is divided into two parts. Derived demand: The more sensitive buyers are to the price of the end benefit, the more sensitive they will be to the prices of those products that contribute to that benefit. Price proportion cost: The price proportion cost refers to the percent of the total cost of the end benefit accounted for by a given component that helps to produce the end benefit, such as with computers. The smaller the given component’s share of the total cost of the end benefit, the less sensitive buyers will be to the component’s price.

- Shared-cost effect – The smaller the portion of the purchase price buyers must pay for themselves, the less price sensitive they will be.

- Fairness effect – Buyers are more sensitive to the price of a product when the price is outside the range they perceive as “fair” or “reasonable” given the purchase context.

- The framing effect – Buyers are more price sensitive when they perceive the price as a loss rather than a forgone gain, and they have greater price sensitivity when the price is paid separately rather than as part of a bundle.

Oil Price Sensitivity

The graph shows the price fluctuation of oil after consumers have significant access to information regarding the commodity.

8.4.5: Other Inputs to Pricing Decisions

Pricing decisions can have a variety of inputs, such as value-added considerations, legal price requirements, competitive positioning, and discounting.

Learning Objective

List a few of the key considerations to pricing aside from simple expense-oriented break-even analyses

Key Points

- Pricing is an important decision, as it impacts both profitability and competitive positioning.

- One particularly important pricing consideration are the legal requirements in some industries (price floors and ceilings). For example, rent-controlled housing will have price limitations an organization will have to adhere to.

- Functional value, social value, monetary value, and psychological value should all be taken into consideration when setting prices.

- Differentiation and competitive positioning relative to other industry incumbents is another important pricing consideration. Differentiation can often lead to higher margins (though often lower volume).

- For perishable goods or items which may go out of fashion (technology, clothing, etc.), discounting is a useful way to ensure that the organization gets some capital back for producing it (even if it sells at a loss on a per unit basis).

Key Term

- perishable

-

Liable to perish, especially naturally subject to quick decomposition or decay.

Pricing Decisions

The pricing decision is an important one, both for profitability and competitive positioning. Organizations must take into account supply, demand, competition, expenses, profit margins, differentiation, quality, and legal concerns. The simplest methods of determining price include concepts such as break-even points, fixed/variable cost analysis, and marginal analysis. However, there are other concerns that need to be investigated when determining price.

Pricing Inputs

Looking at cost structures and determining break-even points is not always enough when it comes to effective pricing strategies. As a result, marketers should be familiar with the legalities of pricing (for certain commodities in particular), the value added to the consumer (willingness to pay), competitive positioning, and potential discounts.

Legal Concerns

For some products, governments will set firm price controls (i.e. price ceilings or price floors) to ensure ethical and/or accessible pricing for a given population. Just as the name implies, price floors and price ceilings will set minimum or maximum prices for some goods. This is particularly applicable to rent, real estate, banking, food and other core necessities. When operating in an industry with price ceilings or price floors, firms must adapt their pricing strategy to these legalities and ensure compliance.

Price Ceiling

When considering pricing decisions, understanding price floors and price ceilings is important.

Value-Added Pricing

In a perfectly practical and efficient market, the expenses would almost always lead to the appropriate price through competitive forces. However, we do not live in a world of perfect markets. As a result, there are a number of value-adds that consumers receive that are not easy or intuitive to measure from a strictly financial perspective. These include:

- Functional Value: This is a typical example of demand, where the product is valued at how well it accomplishes a function (i.e. fulfills the need).

- Monetary Value: This is another typical value example, where the cost of resources and production correlate cleanly with the price.

- Social Value: The value a consumer receives can actually be social as well as economic. This is to say that some products provide intangible value to users. Fashion is a good example here, as some fashion items return margins that are enormous due to the social perception of a given fashion item (expensive bags, for example).

- Psychological Value: Some items have value to an individual for personal reasons. A collector, for example, may pay far more than an item is worth due to a strong love for something. People who collect video game action figures, or deluxe editions, for example.

Competitive Positioning

Another input to pricing is the basic premise of differentiation to achieve higher value. This is not so much an exception to the above mentioned value-added pricing, but more of a facet of this. Branded items, for example, are often quite similar to generic versions of the same item. However, these brands add intangible value to the product above and beyond the cost of producing it. Buying brand name goods may be differentiated based upon celebrity sponsors, premium perception, social value or a wide variety of other differentiated factors. These can enable organizations to differentiate for a price premium (i.e. they can charge more for having a strong brand/position).

Discounting

There are also a number of reasons why an organization may offer discounts. Discounting is particularly useful when it comes to B2B transactions, in which a client might buy a few thousand of a given product and receive a wholesale price that is significantly lower than the price of buying each product individually. There are also situations in which a product may be sold at a price that is actually less than the cost of producing it. This is most often done when a perishable item will soon go bad anyway. In such a situation, selling at a loss is better than getting nothing at all (opportunity cost!).

Conclusion

All and all, pricing is a bit more complicated than simply understanding the expenses involve. Marketers must understand social value, legal considerations, branding, discounting, and the functional value of products and services in order to capture the full potential of a given item. Pricing can be a great opportunity to capture better margins than the competition, or could offer the ability to make a mistake and lose market share!

8.5: Pricing Objectives

8.5.1: Survival

Most executives pursue strategies that align pricing with revenue generation, enabling their organizations to survive and thrive long term.

Learning Objective

Name the different factors that impact a company’s success and survival

Key Points

- New and improved products may hold the key to a firm’s survival and ultimate success.

- All business enterprises must earn a long term profit in order to survive in the long run.

- Just as survival requires a long term profit for a business enterprise, profit requires sales. Sales patterns should be altered to ensure success.

- Management of all firms, large and small, are concerned with maintaining an adequate share of the market so their sales volume will enable the firm to survive and prosper. Prices must be set to attract the appropriate market segment in significant numbers.

Key Term

- Market Share

-

The percentage of a market (defined in terms of either units or revenue) accounted for by a specific entity.

Example

- Companies like McDonald’s and Starbucks were able to survive the recession by being smart about how they conducted business. The both closed down locations in less-favorable neighborhoods and added more products to their menus.

Survival

Firms rely on price to cover the costs of production, pay expenses, and provide the profit incentive necessary to continue to operate the business. These factors help an organization survive. Most managers pursue strategies that enable their organizations to continue in operation for the long term. Thus, survival is one major objective pursued by company executives. For a commercial firm, the price paid by the buyer generates the firm’s revenue. If revenue falls below cost for a long period of time, the firm cannot survive. Survival is closely linked to new product development, profit, sales, market share, and image.

New Products

For several decades, business has come increasingly to the realization that new and improved products may hold the key to their survival and ultimate success. Consequently, professional management has become an integral part of this process. As a result, many firms develop new products based on an orderly procedure, employing comprehensive and relevant data and intelligent decision-making.The continuing development of a successful new product looms as the most important factor in the survival of the firm.

Profit

Making a $500,000 profit during the next year might be a pricing objective for a firm. Anything less will ensure failure. All business enterprises must earn a long term profit. For many businesses, long term profitability also allows the business to satisfy company stakeholders such as investors, employees, customers, and suppliers. Lower-than-expected or no profits will drive down stock prices and may prove disastrous for the company.

Sales

Just as survival requires a long term profit for a business enterprise, profit requires sales. The task of marketing management relates to managing demand. Demand must be managed in order to regulate exchanges or sales. Thus, marketing management’s aim is to alter sales patterns in some desirable way.

Market Share

If the sales of Safeway Supermarkets in the Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan area of Texas account for 30 percent of all food sales in that area, we say that Safeway has a 30 percent market share. Management of all firms, large and small, are concerned with maintaining an adequate share of the market so their sales volume will enable the firm to survive and prosper. Again, pricing strategy is one of the tools that is significant in creating and sustaining market share. Prices must be set to attract the appropriate market segment in significant numbers.

Image

Price policies play an important role in affecting a firm’s position of respect and esteem in its community. Price is a highly visible communicator. It must convey the message to the community that the firm offers good value, that it is fair in its dealings with the public, that it is a reliable place to patronize, and that it stands behind its products and services.

Surviving the Recession

Pricing plays a significant role in attracting and retaining market share during tough economic times.

8.5.2: Profit

If the sole objective of a firm is to maximize profit, there are various profit maximizing pricing methods that can be used.

Learning Objective

Recall formulas for calculating profit maximizing output quantity and marginal profit

Key Points

- In launching new products or considering the pricing of current products, managers often start with an idea of the dollar profit they desire and ask what level of sales will be needed to reach it. This can be done through profit-based sales targets.