How do social workers know the right thing to do? It’s an important question. Incorrect social work actions may actively harm clients and communities. Timely and effective social work interventions further social justice and promote individual change. To do make the right choices, we must have a basis of knowledge, the skills to understand it, and the commitment to growing that knowledge. The source of social work knowledge is social science and this book is about how to understand and apply it to social work practice.

Chapter outline

- 1.1 How do social workers know what to do?

- 1.2 Science and social work

- 1.3 Why should we care?

- 1.4 Understanding research

Content advisory

This chapter discusses or mentions the following topics: stereotypes of people on welfare, sexual harassment and sexist job discrimination, sexism, poverty, homelessness, mental illness, substance abuse, and child maltreatment.

1.1 How do social workers know what to do?

Learning Objectives

- Reflect on how we know what to do as social workers

- Differentiate between micro-, meso-, and macro-level analysis

- Describe intuition, its purpose in social work, and its limitations

- Identify specific types of cognitive biases and how the influence thought

- Define scientific inquiry

What would you do?

Imagine you are a clinical social worker at a children’s mental health agency. Today, you receive a referral from your town’s middle school about a client who often skips school, gets into fights, and is disruptive in class. The school has suspended him and met with the parents multiple times, who say they practice strict discipline at home. Yet, the client’s behavior only gotten worse. When you arrive at the school to meet with the boy, you notice he has difficulty maintaining eye contact with you, appears distracted, and has a few bruises on his legs. At the same time, he is also a gifted artist, and you two spend the hour in which you assess him painting and drawing.

- Given the strengths and challenges you notice, what interventions would you select for this client and how would you know your interventions worked?

Imagine you are a social worker in an urban food desert, a geographic area in which there is no grocery store that sells fresh food. Many of your low-income clients rely on food from the dollar store or convenience stores in order to live or simply order takeout. You are becoming concerned about your clients’ health, as many of them are obese and say they are unable to buy fresh food. Because convenience stores are more expensive and your clients mostly survive on minimum wage jobs or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, they often have to rely on food pantries towards the end of the month once their money runs out. You have spent the past month building a coalition composed of members from your community, including non-profit agencies, religious groups, and healthcare workers to lobby your city council.

- How should your group address the issue of food deserts in your community? What intervention do you suggest? How would you know if your intervention worked?

You are a social worker working at a public policy center focused on homelessness. Your city is seeking a large federal grant to address the growing problem of homelessness in your city and has hired you as a consultant to work on the grant proposal. After conducting a needs assessment in collaboration with local social service agencies and interviewing people who are homeless, you meet with city councilmembers to talk about your options to create a program. Local agencies want to spend the money to build additional capacity at existing shelters in the community. They also want to create a transitional housing program at an unused apartment complex where people can live after the shelter and learn independent living skills. On the other hand, the clients you interview want to receive housing vouchers so they can rent an apartment from a landlord in the community. They also fear the agencies running the shelter and transitional housing program would dictate how to live their lives and impose unnecessary rules, like restrictions on guests or quiet hours. When you ask the agencies about client feedback, they state that clients could not be trusted to manage in their own apartments and need the structure and supervision provided by agency support workers.

- What kind of program should your city choose to implement? Which program is most likely to be effective?

Assuming you’ve taken a social work course before, you will notice that the case studies cover different levels of analysis in the social ecosystem—micro, meso, and macro. At the micro-level, social workers examine the smallest levels of interaction; even in some cases, just “the self” alone. That is our child in case 1. When social workers investigate groups and communities, such as our food desert in case 2, their inquiry is at the meso-level. At the macro-level, social workers examine social structures and institutions. Research at the macro-level examines large-scale patterns, including culture and government policy, as in case 3. These domains interact with each other, and it is common for a social work research project to address more than one level of analysis. Moreover, research that occurs on one level is likely to have implications at the other levels of analysis.

How do social workers know what to do?

Welcome to social work research. This chapter begins with three problems that social workers might face in practice and three questions about what a social worker should do next. If you haven’t already, spend a minute or two thinking about how you would respond to each case and jot down some notes. How would you respond to each of these cases?

For many of you this textbook will likely come at an early point in your social work education, so it may seem unfair to ask you what the right answers are. And to disappoint you further, this course will not teach you the right answer to these questions. It will, however, teach you how to answer these questions for yourself. Social workers must learn how to examine the literature on a topic, come to a reasoned conclusion, and use that knowledge in their practice. Similarly, social workers engage in research to make sure their interventions are helping, not harming, clients and to contribute to social science as well as social justice.

Again, assuming you did not have advanced knowledge of the topics in the case studies, when you thought about what you might do in those practice situations, you were likely using intuition (Cheung, 2016). Intuition is a way of knowing that is mostly unconscious. You simply have a gut feeling about what you should do. As you think about a problem such as those in the case studies, you notice certain details and ignore others. Using your past experiences, you apply knowledge that seems to be relevant and make predictions about what might be true.

In this way, intuition is based on direct experience. Many of us know things simply because we’ve experienced them directly. For example, you would know that electric fences can be pretty dangerous and painful if you touched one while standing in a puddle of water. We all probably have times we can recall when we learned something because we experienced it. If you grew up in Minnesota, you would observe plenty of kids learning each winter that it really is true that your tongue will stick to metal if it’s very cold outside. Similarly, if you passed a police officer on a two-lane highway while driving 20 miles over the speed limit, you would probably learn that that’s a good way to earn a traffic ticket.

Intuition and direct experience are powerful forces. Uniquely, social work is a discipline that values intuition, though it will take quite a while for you to develop what social workers refer to as practice wisdom. Practice wisdom is the “learning by doing” that develops as one practices social work over a period of time. Social workers also reflect on their practice, independently and with colleagues, which sharpens their intuitions and opens their mind to other viewpoints. While your direct experience in social work may be limited at this point, feel confident that through reflective practice you will attain practice wisdom.

However, it’s important to note that intuitions are not always correct. Think back to the first case study. What might be your novice diagnosis for this child’s behavior? Does he have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) because he is distractible and getting into trouble at school? Or are those symptoms of autism spectrum disorder or an attachment disorder? Are the bruises on his legs an indicator of ADHD, or do they indicate possible physical abuse at home? Even if you arrived at an accurate assessment of the situation, you would still need to figure out what kind of intervention to use with the client. If he has a mental health issue, you might say, “give him therapy.” Well…what kind of therapy? Should we use cognitive-behavioral therapy, play therapy, art therapy, family therapy, or animal assisted therapy? Should we try a combination of therapy and medication prescribed by a psychiatrist?

We could guess which intervention would be best…but in practice, that would be highly unethical. If we guessed wrong, we could be wasting time, or worse, actively harming a client. We need to ground our social work interventions with clients and systems with something more secure than our intuition and experience.

Cognitive biases

Although the human mind is a marvel of observation and data analysis, there are universal flaws in thinking that must be overcome. We all rely on mental shortcuts to help us make sense of a continuous stream of new information. All people, including me and you, must train our minds to be aware of predictable flaws in thinking, termed cognitive biases. Here is a link to the Wikipedia entry on cognitive biases. As you can see, it is quite long. We will review some of the most important ones here, but take a minute and browse around to get a sense of how baked-in cognitive biases are to how humans think.

The most important cognitive bias for social scientists to be aware of is confirmation bias. Confirmation bias involves observing and analyzing information in a way that confirms what you already think is true. No person is a blank slate. We all arrive at each moment with a set of beliefs, experiences, and models of how the world works that we develop over time. Often, these are grounded in our own personal experiences. Confirmation bias assumes these intuitions are correct and ignores or manipulates new information order to avoid challenging what we already believe to be true.

Confirmation bias can be seen in many ways. Sometimes, people will only pay attention to the information that fits their preconceived ideas and ignore information that does not fit. This is called selective observation. Other times, people will make hasty conclusions about a broad pattern based on only a few observations. This is called overgeneralization. Let’s walk through an example and see how they each would function.

In our second case study, we are trying to figure out how to help people who receive SNAP (formerly Food Stamps) who live in a food desert. Let’s say that we have arrived at a solution and are now lobbying the city council to implement it. There are many people who have negative beliefs about people who are “on welfare.” These people believe individuals who receive social welfare benefits spend their money irresponsibly, are too lazy to get a job, and manipulate the system to maintain or increase their government payout. People expressing this belief may provide an example like Louis Cuff, who bought steak and lobster with his SNAP benefits and resold them for a profit.

City council members who hold these beliefs may ignore the truth about your client population—that people experiencing poverty usually spend their money responsibly and genuinely need help accessing fresh and healthy food. This would be an example of selective observation, only looking at the cases that confirm their biased beliefs about people in poverty and ignoring evidence that challenges that perspective. Likely, these are grounded in overgeneralization, in which one example, like Mr. Cuff, is applied broadly to the population of people using social welfare programs. Social workers in this situation would have to hope that city council members are open to another perspective and can be swayed by evidence that challenges their beliefs. Otherwise, they will continue to rely on a biased view of people in poverty when they create policies.

But where do these beliefs and biases come from? Perhaps, someone who the person considers an authority told them that people in poverty are lazy and manipulative. Naively relying on authority can take many forms. We might rely on our parents, friends, or religious leaders as authorities on a topic. We might consult someone who identifies as an expert in the field and simply follow what they say. We might hop aboard a “bandwagon” and adopt the fashionable ideas and theories of our peers and friends.

Now, it is important to note that experts in the field should generally be trusted to provide well-informed answers on a topic, though that knowledge should be receptive to skeptical critique and will develop over time as more scholars study the topic. There are limits to skepticism, however. Disagreeing with experts about global warming, the shape of the earth, or the efficacy and safety of vaccines does not make one free of cognitive biases. On the contrary, it is likely that the person is falling victim to the Dunning-Kruger effect, in which unskilled people overestimate their ability to find the truth. As this comic illustrates, they are at the top of Mount Stupid. Only through rigorous, scientific inquiry can they progress down the back slope and hope to increase their depth of knowledge about a topic.

Scientific Inquiry

Cognitive biases are most often expressed when people are using informal observation. Until you read the question at the beginning of this chapter, you may have had little reason to formally observe and make sense of information about children’s mental health, food deserts, or homelessness policy. Because you engaged in informal observation, it is more likely that you will express cognitive biases in your responses. The problem with informal observation is that sometimes it is right, and sometimes it is wrong. And without any systematic process for observing or assessing the accuracy of our observations, we can never really be sure that our informal observations are accurate. In order to minimize the effect of cognitive biases and come up with the truest understanding of a topic, we must apply a systematic framework for understanding what we observe.

The opposite of informal observation is scientific inquiry, used interchangeably with the term research methods in this text. These terms refer to an organized, logical way of knowing that involves both theory and observation. Science accounts for the limitations of cognitive biases—not perfectly, though—by ensuring observations are done rigorously, following a prescribed set of steps. Scientists clearly describe the methods they use to conduct observations and create theories about the social world. Theories are tested by observing the social world, and they can be shown to be false or incomplete. In short, scientists try to learn the truth. Social workers use scientific truths in their practice and conduct research to revise and extend our understanding of what is true in the social world. Social workers who ignore science and act based on biased or informal observation may actively harm clients.

Key Takeaways

- Social work research occurs on the micro-, meso-, and macro-level.

- Intuition is a power, though woefully incomplete, guide to action in social work.

- All human thought is subject to cognitive biases.

- Scientific inquiry accounts for cognitive biases by applying an organized, logical way of observing and theorizing about the world.

Glossary

- Authority- learning by listening to what people in authority say is true

- Cognitive biases- predictable flaws in thinking

- Confirmation bias- observing and analyzing information in a way that confirms what you already think is true

- Direct experience- learning through informal observation

- Dunning-Kruger effect- when unskilled people overestimate their ability and knowledge (and experts underestimate their ability and knowledge)

- Intuition- your “gut feeling” about what to do

- Macro-level- examining social structures and institutions

- Meso-level- examining interaction between groups

- Micro-level- examining the smallest levels of interaction, usually individuals

- Overgeneralization- using limited observations to make assumptions about broad patterns

- Practice wisdom- “learning by doing” that guides social work intervention and increases over time

- Research methods- an organized, logical way of knowing based on theory and observation

1.2 Science and social work

Learning Objectives

- Define science

- Describe the the difference between objective and subjective truth(s)

- Describe the role of ontology and epistemology in scientific inquiry

Science and social work

Science is a particular way of knowing that attempts to systematically collect and categorize facts or truths. A key word here is systematically–conducting science is a deliberate process. Scientists gather information about facts in a way that is organized and intentional, usually following a set of predetermined steps. More specifically, social work is informed by social science, the science of humanity, social interactions, and social structures. In other words, social work research uses organized and intentional procedures to uncover facts or truths about the social world. And social workers rely on social scientific research to promote individual and social change.

Philosophy of social science

This approach to finding truth probably sounds similar to something you heard in your middle school science classes. When you learned about the gravitational force or the mitochondria of a cell, you were learning about the theories and observations that make up our understanding of the physical world. These theories rely on an ontology, or a set of assumptions about what is real. We assume that gravity is real and that the mitochondria of a cell are real. Mitochondria are easy to spot with a powerful enough microscope and we can observe and theorize about their function in a cell. The gravitational force is invisible, but clearly apparent from observable facts, like watching an apple fall. The theories about gravity have changed over the years, but improvements in theory were made when observations could not be correctly interpreted using existing theories.

If we weren’t able to perceive mitochondria or gravity, they would still be there, doing their thing because they exist independent of our observation of them. This is a philosophical idea called realism, and it simply means that the concepts we talk about in science really and truly exist. Ontology in physics and biology is focused on objectivetruth. Chances are you’ve heard of “being objective” before. It involves observing and thinking with an open mind, pushing aside anything that might bias your perspective. Objectivity also means we want to find what is true for everyone, not just what is true for one person. Certainly, gravity is true for everyone and everywhere. Let’s consider a social work example, though. It is objectively true that children who are subjected to severely traumatic experiences will experience negative mental health effects afterwards. A diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is considered to be objective, referring to a real mental health issue that exists independent of the social worker observing it and that is highly similar in its presentation with our client as it would be with other clients.

So, an objective ontological perspective means that what we observe is true for everyone and true even when we aren’t there to observe it. How do we come to know objective truths like these? This is the study of epistemology, or our assumptions about how we come to know what is real and true. The most relevant epistemological question in the social sciences is whether truth is better accessed using numbers or words. Generally, scientists approaching research with an objective ontology and epistemology will use quantitative methods to arrive at scientific truth. Quantitative methods examine numerical data to precisely describe and predict elements of the social world. This is due to the epistemological assumption that mathematics can represent the phenomena and relationships we observe in the social world.

Mathematical relationships are uniquely useful, in that they allow comparisons across individuals as well as across time and space. For example, while people can have different definitions for poverty, an objective measurement such as an annual income of less than $25,100 for a family of four provides (1) a precise measurement, (2) that can be compared to incomes from all other people in any society from any time period, (3) and refer to real quantities of money that exist in the world. In this book, we will review survey and experimental methods, which are the most common designs that use quantitative methods to answer research questions.

It may surprise you to learn that objective facts, such as income or age, are not the only facts in the social sciences. Indeed, social science is not only concerned with objective truth. Social science also describes subjective truth, or the truths that are unique to individuals, groups, and contexts. Unlike objective truth, which is true for all people, subjective truths will vary based on who you are observing and the context in which you are observing them. The beliefs, opinions, and preferences of people are actually truths that social scientists measure and describe. Additionally, subjective truths do not exist independent of human observation because they are the product of the human mind. We negotiate what is true in the social world through language, arriving at a consensus and engaging in debate.

Epistemologically, a scientist seeking subjective truth assumes that truth lies in what people say, their words. A scientist uses qualitative methods to analyze words or other media to understand their meaning. Humans are social creatures, and we give meaning to our thoughts and feelings through language. Linguistic communication is unique. We share ideas with each other at a remarkable rate. In so doing, ideas come into and out of existence in a spontaneous and emergent fashion. Words are given a meaning by their creator. But anyone who receives that communication can absorb, amplify, and even change its original intent. Because social science studies human interaction, subjectivists argue that language is the best way to understand the world.

This epistemology is based on some interesting ontological assumptions. What happens when someone incorrectly interprets a situation? While their interpretation may be wrong, it is certainly true to them that they are right. Furthermore, they act on the assumption that they are right. In this sense, even incorrect interpretations are truths, even though they are only true to one person. This leads us to question whether the social concepts we think about really exist. They might only exist in our heads, unlike concepts from the natural sciences which exist independent of our thoughts. For example, if everyone ceased to believe in gravity, we wouldn’t all float away. It has an existence independent of human thought.

Let’s think through an example. In the Diagnositic and Statistical Manual (DSM) classification of mental health disorders, there is a list of culture-bound syndromes which only appear in certain cultures. For example, susto describes a unique cluster of symptoms experienced by people in Latin American cultures after a traumatic event that focus on the body. Indeed, many of these syndromes do not fit within a Western conceptualization of mental health because they differentiate less between the mind and body. To a Western scientist, susto may seem less real than PTSD. To someone from Latin America, their symptoms may not fit neatly into the PTSD framework developed within Western society. This conflict raises the question–do either susto or PTSD really exist at all? If your answer is “no,” you are adopting the ontology of anti-realism, that social concepts do not have an existence apart from human thought. Unlike the realists who seek a single, universal truth, the anti-realists see a sea of truths, created and shared within a social and cultural environment.

Let’s consider another example: manels or all-male panel discussions at conferences and conventions. Check out this National Public Radio article for some hilarious examples, ironically including panels about diversity and gender representation. Manels are a problem in academic gatherings, Comic-Cons, and other large group events. A holdover of sexist stereotypes and gender-based privilege, manels perpetuate the sexist idea that men are the experts who deserve to be listened to by other, less important and knowledgeable people. At least, that’s what we’ve come to recognize over the past few decades thanks to feminist critique. However, let’s take the perspective of a few different participants at a hypothetical conference and examine their individual, subjective truths.

When the conference schedule is announced, we see that of the ten panel discussions announced, there are only two that contain women. Pamela, an expert on the neurobiology of child abuse, thinks that this is unfair and as she was excluded from a panel on her specialty. Marco, an event organizer, feels that since the organizers simply went with who was most qualified to speak and did not consider gender, the results could not be sexist. Dionne, a professor who specializes in queer theory and indigenous social work, agrees with Pamela that manels are sexist but also feels that the focus on gender excludes and overlooks the problems with race, disability, sexual and gender identity, and social class among the conference panel members. Given these differing interpretations, how can we come to know what is true about this situation?

Honestly, there are a lot of truths here, not just one truth. Clearly, Pamela’s truth is that manels are sexist. Marco’s truth is that they are not necessarily sexist, as long as they were chosen in a sex-blind manner. While none of these statements is objectively true—a single truth for everyone, in all possible circumstances—they are subjectively true to the people who thought them up. Subjective truth consists of the the different meanings, understandings, and interpretations created by people and communicated throughout society. The communication of ideas is important, as it is how people come to a consensus on how to interpret a situation, negotiating the meaning of events, and informing how people act. Thus, as feminist critiques of society become more accepted, people will behave in less sexist ways. From a subjective perspective, there is no magical number of female panelists conferences much reach to be sufficiently non-sexist. Instead, we should investigate using language how people interpret the gender issues at the event, analyzing them within a historical and cultural context. But how do we find truth when everyone had their own unique interpretation? By finding patterns.

Science means finding patterns in data

Regardless of whether you are seeking objective truth or subjective truths, research and scientific inquiry aim to find and explain patterns. Most of the time, a pattern will not explain every single person’s experience, a fact about social science that is both fascinating and frustrating. Even individuals who do not know each other and do not coordinate in any deliberate way can create patterns that persist over time. Those new to social science may find these patterns frustrating because they may believe that the patterns that describe their gender, age, or some other facet of their lives don’t really represent their experience. It’s true. A pattern can exist among your cohort without your individual participation in it. There is diversity within diversity.

Let’s consider some specific examples. One area that social workers commonly investigate is the impact of a person’s social class background on their experiences and lot in life. You probably wouldn’t be surprised to learn that a person’s social class background has an impact on their educational attainment and achievement. In fact, one group of researchers (Ellwood & Kane, 2000) in the early 1990s found that the percentage of children who did not receive any postsecondary schooling was four times greater among those in the lowest quartile (25%) income bracket than those in the upper quartile of income earners (i.e., children from high- income families were far more likely than low-income children to go on to college). Another recent study found that having more liquid wealth that can be easily converted into cash actually seems to predict children’s math and reading achievement (Elliott, Jung, Kim, & Chowa, 2010).

These findings—that wealth and income shape a child’s educational experiences—are probably not that shocking to any of us. Yet, some of us may know someone who may be an exception to the rule. Sometimes the patterns that social scientists observe fit our commonly held beliefs about the way the world works. When this happens, we don’t tend to take issue with the fact that patterns don’t necessarily represent all people’s experiences. But what happens when the patterns disrupt our assumptions?

For example, did you know that teachers are far more likely to encourage boys to think critically in school by asking them to expand on answers they give in class and by commenting on boys’ remarks and observations? When girls speak up in class, teachers are more likely to simply nod and move on. The pattern of teachers engaging in more complex interactions with boys means that boys and girls do not receive the same educational experience in school (Sadker & Sadker, 1994). You and your classmates, of all genders, may find this news upsetting.

People who object to these findings tend to cite evidence from their own personal experience, refuting that the pattern actually exists. However, the problem with this response is that objecting to a social pattern on the grounds that it doesn’t match one’s individual experience misses the point about patterns. Patterns don’t perfectly predict what will happen to an individual person. Yet, they are a reasonable guide that, when systematically observed, can help guide social work thought and action.

A final note on qualitative and quantitative methods

There is no one superior way to find patterns that help us understand the world. There are multiple philosophical, theoretical, and methodological ways to approach uncovering scientific truths. Qualitative methods aim to provide an in-depth understanding of a relatively small number of cases. Quantitative methods offer less depth on each case but can say more about broad patterns in society because they typically focus on a much larger number of cases. A researcher should approach the process of scientific inquiry by formulating a clear research question and conducting research using the methodological tools best suited to that question.

Believe it or not, there are still significant methodological battles being waged in the academic literature on objective vs. subjective social science. Usually, quantitative methods are viewed as “more scientific” and qualitative methods are viewed as “less scientific.” Part of this battle is historical. As the social sciences developed, they were compared with the natural sciences, especially physics, which rely on mathematics and statistics to find truth. It is a hotly debated topic whether social science should adopt the philosophical assumptions of the natural sciences—with its emphasis on prediction, mathematics, and objectivity—or use a different set of tools—understanding, language, and subjectivity—to find scientific truth.

You are fortunate to be in a profession that values multiple scientific ways of knowing. The qualitative/quantitative debate is fueled by researchers who may prefer one approach over another, either because their own research questions are better suited to one particular approach or because they happened to have been trained in one specific method. In this textbook, we’ll operate from the perspective that qualitative and quantitative methods are complementary rather than competing. While these two methodological approaches certainly differ, the main point is that they simply have different goals, strengths, and weaknesses. A social work researcher should choose the methods that best match with the question they are asking.

Key Takeaways

- Social work is informed by science.

- Social science is concerns with both objective and subjective knowledge.

- Social science research aims to understand patterns in the social world.

- Social scientists use both qualitative and quantitative methods. While different, these methods are often complementary.

Glossary

- Epistemology- a set of assumptions about how we come to know what is real and true

- Objective truth- a single truth, observed without bias, that is universally applicable

- Ontology- a set of assumptions about what is real

- Qualitative methods- examine words or other media to understand their meaning

- Quantitative methods- examine numerical data to precisely describe and predict elements of the social world

- Science- a particular way of knowing that attempts to systematically collect and categorize facts or truth

- Subjective truth- one truth among many, bound within a social and cultural context

1.3 Why should we care?

Learning Objectives

- Describe and discuss four important reasons why students should care about social scientific research methods

- Identify how social workers use research as part of evidence-based practice

At this point, you may be wondering about the relevance of research methods to your life. Whether or not you choose to become a social worker, you should care about research methods for two basic reasons: (1) research methods are regularly applied to solve social problems and issues that shape how our society is organized, thus you have to live with the results of research methods every day of your life, and (2) understanding research methods will help you evaluate the effectiveness of social work interventions, an important skill for future employment.

Consuming research and living with its results

Another New Yorker cartoon depicts two men chatting with each other at a bar. One is saying to the other, “Are you just pissing and moaning, or can you verify what you’re saying with data?” Which would you rather be, just a complainer or someone who can actually verify what you’re saying? Understanding research methods and how they work can help position you to actually do more than just complain. Further, whether you know it or not, research probably has some impact on your life each and every day. Many of our laws, social policies, and court proceedings are grounded in some degree of empirical research and evidence (Jenkins & Kroll-Smith, 1996). That’s not to say that all laws and social policies are good or make sense. However, you can’t have an informed opinion about any of them without understanding where they come from, how they were formed, and what their evidence base is. All social workers, from micro to macro, need to understand the root causes and policy solutions to social problems that their clients are experiencing.

A recent lawsuit against Walmart provides an example of social science research in action. A sociologist named Professor William Bielby was enlisted by plaintiffs in the suit to conduct an analysis of Walmart’s personnel policies in order to support their claim that Walmart engages in gender discriminatory practices. Bielby’s analysis shows that Walmart’s compensation and promotion decisions may indeed have been vulnerable to gender bias. In June 2011, the United States Supreme Court decided against allowing the case to proceed as a class-action lawsuit (Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes, 2011). While a class-action suit was not pursued in this case, consider the impact that such a suit against one of our nation’s largest employers could have on companies and their employees around the country and perhaps even on your individual experience as a consumer.

In addition to having to live with laws and policies that have been crafted based on social science research, you are also a consumer of all kinds of research, and understanding methods can help you be a smarter consumer. Ever notice the magazine headlines that peer out at you while you are waiting in line to pay for your groceries? They are geared toward piquing your interest and making you believe that you will learn a great deal if you follow the advice in a particular article. However, since you would have no way of knowing whether the magazine’s editors had gathered their data from a representative sample of people like you and your friends, you would have no reason to believe that the advice would be worthwhile. By having some understanding of research methods, you can avoid wasting your money by buying the magazine and wasting your time by following inappropriate advice.

Pick up or log on to the website for just about any magazine or newspaper, or turn on just about any news broadcast, and chances are you’ll hear something about some new and exciting research results. Understanding research methods will help you read past any hype and ask good questions about what you see and hear. In other words, research methods can help you become a more responsible consumer of public and popular information. And who wouldn’t want to be more responsible?

Evidence-based practice

Probably the most asked questions, though seldom asked directly, are “Why am I in this class?” or “When will I ever use this information?“ While it may seem strange, the answer is “pretty often.” Social work supervisors and administrators at agency-based settings will likely have to demonstrate that their agency’s programs are effective at achieving their goals. Most private and public grants will require evidence of effectiveness in order to continue receiving money and keep the programs running. Social workers at community-based organization commonly use research methods to target their interventions to the needs of their service area. Clinical social workers must also make sure that the interventions they use in practice are effective and not harmful to clients. Social workers may also want to track client progress on goals, help clients gather data about their clinical issues, or use data to advocate for change. All social workers in all practice situations must also remain current on the scientific literature to ensure competent and ethical practice.

In all of these cases, a social worker needs to be able to understand and evaluate scientific information. Evidence-based practice (EBP) for social workers involves making decisions on how to help clients based on the best available evidence. A social worker must examine the literature, understanding both the theory and evidence relevant to the practice situation. According to Rubin and Babbie (2017), EBP also involves understanding client characteristics, using practice wisdom and existing resources, and adapting to environmental context. Plainly said, EBP consists of four main components: (1) the best evidence available for the practice-related question or concern, (2) client values and preferences, (3) practitioner expertise, and (4) client circumstances.

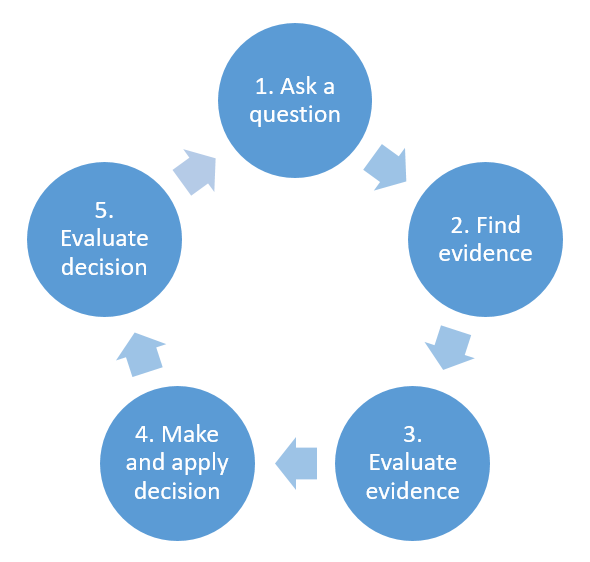

EBP is not simply “doing what the literature says,” but rather a process by which practitioners examine the literature, client, self, and context to inform interventions with clients and systems. As we discussed in Section 1.2, the patterns discovered by scientific research are not perfectly applicable to all situations. Instead, we rely on the critical thinking of social workers to apply scientific knowledge to real-world situations. Social workers apply their critical thinking to the process of EBP by starting with a question about their practice, seeking evidence to answer the question, critically reviewing the evidence they find, making and implementing a decision based on the four components of EBP, and then evaluating the outcome of the decision. EBP is a continual process in which new practice questions continually arise.

Let’s consider an example of a social work administrator at a children’s mental health agency. The agency uses private grant funds to fund a program that provides low-income children with bicycles, teaches the children how to repair and care for their bicycles, and leads group bicycle outings after school. Physical activity has been shown to improve mental health outcomes in scientific studies, but is this social worker’s program improving mental health in their clients? Ethically, the social worker should make sure that the program is achieving its goals. If the program is not beneficial, the resources should be spent on more effective programs. Practically, the social worker will also need to demonstrate to the agency’s funders that bicycling truly helps children deal with their mental health concerns.

The example above demonstrates the need for social workers to engage in evaluation research or research that evaluates the outcomes of a policy or program. She will choose from many acceptable ways to investigate program effectiveness, and those choices are based on the principles of scientific inquiry you will learn in this textbook. As the example above mentions, evaluation research is baked into how nonprofit human service agencies are funded. Government and private grants need to make sure their money is being spent wisely. If your program does not work, then the money should go to a program that has been shown to be effective or a new program that may be effective. Just because a program has the right goal doesn’t mean it will actually accomplish that goal. Grant reporting is an important part of agency-based social work practice. Agencies, in a very important sense, help us discover what approaches actually help clients.

In addition to engaging in evaluation research to satisfy the requirements of a grant, your agency may engage in evaluation research for the purposes of validating a new approach to treatment. Innovation in social work is incredibly important. Sam Tsemberis relates an “aha” moment from his practice in this Ted talk on homelessness. A faculty member at the New York University School of Medicine, he noticed a problem with people cycling in and out of the local psychiatric hospital wards. Clients would arrive in psychiatric crisis, stabilize under medical supervision in the hospital, and end up back at the hospital back in psychiatric crisis shortly after discharge. When he asked the clients what their issues were, they said they were unable to participate in homelessness programs because they were not always compliant with medication for their mental health diagnosis and they continued to use drugs and alcohol. Collaboratively, the problem facing these clients was defined as a homelessness service system that was unable to meet clients where they were. Clients who were unwilling to remain completely abstinent from drugs and alcohol or who did not want to take psychiatric medications were simply cycling in and out of psychiatric crisis, moving from the hospital to the street and back to the hospital.

The solution that Sam Tsemberis implemented and popularized was called Housing First, and it is an approach to homelessness prevention that starts by, you guessed it, providing people with housing first. Similar to an approach to child and family homelessness created by Tanya Tull, Tsemberis created a model of addressing chronic homelessness with people with co-occurring disorders (substance abuse and mental illness). The Housing First model holds that housing is a human right, one that should not be denied based on substance use or mental health diagnosis. Clients are given housing as soon as possible. The Housing First agency provides wraparound treatment from an interdisciplinary team, including social workers, nurses, psychiatrists, and former clients who are in recovery. Over the past few decades, this program has gone from one program in New York City to the program of choice for federal, state, and local governments seeking to address homelessness in their communities.

The main idea behind Housing First is that once clients have an apartment of their own, they are better able to engage in mental health and substance abuse treatment. While this approach may seem logical to you, it is backwards from the traditional homelessness treatment model. The traditional approach began with the client stopping drug and alcohol use and taking prescribed medication. Only after clients achieved these goals were they offered group housing. If the client remained sober and medication compliant, they could then graduate towards less restrictive individual housing.

Evaluation research helps practitioners establish that their innovation is better than the alternatives and should be implemented more broadly. By comparing clients who were served through Housing First and traditional treatment, Tsemberis could establish that Housing First was more effective at keeping people housed and progressing on mental health and substance abuse goals. Starting first with smaller studies and graduating to much larger ones, Housing First built a reputation as an effective approach to addressing homelessness. When President Bush created the Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness in 2003, Housing First was used in a majority of the interventions and demonstrated its effectiveness on a national scale. In 2007, it was acknowledged as an evidence-based practice in the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Policies (NREPP).

Try browsing around the NREPP website and looking for interventions on topics that interest you. Other sources of evidence-based practices include the Cochrane Reviews digital library and Campbell Collaboration. The use of systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials are particularly important in this regard.

So why share the story of Housing First? Well, it may help you think about what you hope to contribute to our knowledge on social work practice. What is your bright idea and how can it change the world? Practitioners innovate all the time, often incorporating those innovations into their agency’s approach and mission. Through the use of research methods, agency-based social workers can demonstrate to policymakers and other social workers that their innovations should be more widely used. Without this wellspring of new ideas, social services would not be able to adapt to the changing needs of clients. Social workers in agency-based practice may also participate in research projects happening at their agency. Partnerships between schools of social work and agencies are a common way of testing and implementing innovations in social work. Clinicians receive specialized training, clients receive additional services, agencies gain prestige, and researchers can study how an intervention works in the real world.

While you may not become a scientist in the sense of wearing a lab coat and using a microscope, social workers must understand science in order to engage in ethical practice. In this section, we reviewed many ways in which research is a part of social work practice, including:

- Determining the best intervention for a client or system

- Ensuring existing services are accomplishing their goals

- Satisfying requirements to receive funding from private agencies and government grants

- Testing a new idea and demonstrating that it should be more widely implemented

Spotlight on UTA School of Social Work

An Evidence-Based Program to Prevent Child Maltreatment

We all know that preventing a problem is better than trying to fix the effects afterwards. Child maltreatment is a problem that social workers often encounter—wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could keep it from happening? Is there an effective intervention for parents who are feeling overwhelmed and are perhaps on the edge of maltreating their children? University of Texas at Arlington’s Dr. Richard Hoefer and (at the time Ph.D. student) Dante Bryant conducted a program evaluation to find out if that is possible. While more research is needed to verify the findings, their work points out a possible way of preventing child maltreatment for some families.

A private nonprofit received a grant to develop and test the “Multi-disciplinary Approach to Prevention Services” program (MAPS). Program staff worked with parents at-risk of committing acts of maltreatment. The overall evaluation question was whether the program had a positive impact.

Before evaluators answer an outcome question like this, they must understand the logic behind a program and test whether that model is correct. In this program, developers believed that parents at-risk of maltreating their children did not have the knowledge and skills needed to be successful parents. Thus, parents were frustrated and unhappy with their children and their own parenting. This leads to a higher risk of maltreatment.

The program’s logic was that if the parents learned and applied skills of effective parenting, positive changes would ensue. Parents’ perception of their children’s behavior would improve, their dissatisfaction would decrease, and maltreatment would not occur. In the longer term, parents would not be involved with Child Protective Services and money would be saved. The program was thus implemented to reduce the need for Child Protective Services (with its costs) by targeting negative parental behavior, strengthening parent-child relations, improving the family environment, and keeping families together.

The evaluation of MAPS answered these questions: (1) Did program participants increase their resource engagement? (2) Did program participants improve parenting knowledge, skills and satisfaction? (3) Did program participants report additional involvement with CPS?

The authors used a one group pretest-posttest design (which you will learn about later in this textbook) to assess program outcomes and achievement levels. Questionnaires were administered as a during the client intake and assessment process; the same questions were later used after the program as a posttest. Hoefer and Bryant (2017) used the Parenting Scale (Arnold, O’Leary, Wolff, & Acker, 1993) to measure actual parental behavior, the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (Burns & Patterson, 1990) to measure both the children’s behavior and how parents perceived it (how much they were bothered by what the child did), and the Kansas Parental Satisfaction scale (James, Schumm, Kennedy, Grigsby, & Shectman, 1985) to understand how parents felt about their own parenting.

At the end of the program, Hoefer and Bryant used data from 64 families to determine results. Parents did receive more resources (primarily parenting skills classes) than they had before the program. All measures of parenting knowledge, skills and satisfaction showed positive changes at a statistically significant level, when comparing pretests and post-tests. Importantly, by the end of the program, only one family of the 64 in the program was further involved with Child Protective Services.

We need more research, though, because the one-group pre-test/post-test design of the evaluation cannot show a causal relationship for the outcomes. In addition, this evaluation was not able to follow families beyond the program’s end to look at long-term effects. Still, along with other research on the efficacy of improving parenting skills to reduce child maltreatment, it builds on a good case to use such interventions on a widespread basis to reduce harm to children.

Key Takeaways

- Whether we know it or not, our everyday lives are shaped by social scientific research.

- Understanding research methods is important for competent and ethical social work practice.

- Understanding social science and research methods can help us become more astute and more responsible consumers of information.

- Knowledge about social scientific research methods is important for ethical practice, as it ensures interventions are based on evidence.

Glossary

- Evaluation research- research that evaluates the outcomes of a policy or program

- Evidence-based practice- making decisions on how to help clients based on the best available evidence

1.4 Understanding research

Learning Objectives

- Describe common barriers to engaging with social work research

- Identify alternative ways to thinking about research methods

Sometimes students struggle to see the connection between research and social work practice. Most students enjoy a social work theory class because they can better understand the world around them. Students also like practice because it shows them how to conduct clinical work with clients—i.e., what most social work students want to do. It can be helpful to look critically at the potential barriers to embracing the study of social work. Most student barriers to research come from the following beliefs:

Research is useless!

Students who say that research methods is not a useful class to them are saying something important. As a scholar (or student), your most valuable asset is your time. You give your time to the subjects you consider important to you and your future practice. Because most social workers don’t become researchers or practitioner-researchers, students feel like a research methods class is a waste of time.

Our discussion of evidence-based practice and the ways in which social workers use research methods in practice brought home the idea that social workers play an important role in creating new knowledge about social services. On a more immediate level, research methods will also help you become a stronger social work student. Upcoming chapters of this textbook will review how to search for literature on a topic and write a literature review. These skills are relevant in every classroom during your academic career. The rest of the textbook will help you understand the mechanics of research methods so you can better understand the content of those pesky journal articles your professors force you to cite in your papers.

Research is too hard!

Research methods involves a lot of terminology that is entirely new to social workers. Other domains of social work, such as practice, are easier to apply your intuition towards. You understand how to be an empathetic person, and your experiences in life can help guide you through a practice situation or even theoretical or conceptual question. Research may seem like a totally new area in which you have no previous experience. It can seem like a lot to learn. In addition to the normal memorization and application of terms, research methods also has wrong answers. There are certain combinations of methods that just don’t work together.

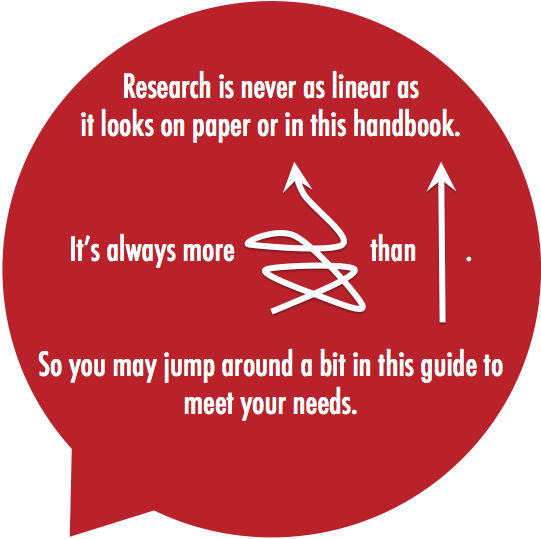

The fear is entirely understandable. Research is not straightforward. As Figure 1.1 shows, it is a process that is non-linear, involving multiple revisions, wrong turns, and dead ends before you figure out the best question and research approach. You may have to go back to chapters after having read them or even peek ahead at chapters your class hasn’t covered yet.

Moreover, research is something you learn by doing…and stumbling a few times. It’s an iterative process, or one that requires lots of tries to get right. There isn’t a shortcut for learning research, but hopefully your research methods class is one in which your research project is broken down into smaller parts and you get consistent feedback throughout the process. No one just knows research. It’s something you pick up by doing it, reflecting on the experiences and results, redoing your work, and revising it in consultation with your professor.

Research is boring!

Research methods is sometimes seen as a boring topic by many students. Practice knowledge and even theory are fun to learn because they are easy to apply and give you insight into the world around you. Research just seems like its own weird, remote thing.

Your social work education will present some generalist material, which is applicable to nearly all social work practice situations, and some applied material, which is applicable to specific social work practice situations. However, no education will provide you with everything you need to know. And certainly, no education will tell you what will be discovered over the next few decades of your practice. Our exploration of research methods will help you further understand how the theories, practice models, and techniques you learn in your other classes are created and tested scientifically. The material you learn in research class will allow you to think critically about material throughout your entire program and into your social work career.

Get out of your own way

Together, the beliefs of “research is useless, boring, and hard” can create a self-fulfilling prophecy for students. If you believe research is boring, you won’t find it interesting. If you believe research is hard, you will struggle more with assignments. If you believe research is useless, you won’t see its utility. Let’s provide some reframing of how you might think about research using these touchstones:

- All social workers rely on social science research to engage in competent practice.

- No one already knows research. It’s something I’ll learn through practice. And it’s challenging for everyone.

- Research is relevant to me because it allows me to figure out what is known about any topic I want to study.

- If the topic I choose to study is important to me, I will be more interested in research.

Structure of this textbook

While you may not have chosen this course, by reframing your approach to it, you increase the likelihood of getting a lot out of it. To that end, here is the structure of this book:

In Chapters 2-5, you’ll learn about how research informs and tests theory. We’ll discuss how to conduct research in an ethical manner, create research questions, and measure concepts in the social world.

Chapters 6-10 will describe how to conduct research, whether it’s a quantitative survey or experiment, or alternately, a qualitative interview or focus group. We’ll also review how to analyze data that someone else has already collected.

Finally, Chapters 11 and 12 will review the types of research most commonly used in social work practice, including evaluation research and action research, and how to report the results of your research to various audiences.

Key Takeaways

- Anxiety about research methods is a common experience for students.

- Research methods will help you become a better scholar and practitioner.