12.1: Strategic Management

12.1.1: What is Strategy?

A strategy is a plan of action designed to achieve a specific goal or series of goals within an organizational framework.

Learning Objective

Define strategy within the context of a business and their organizational goals

Key Points

- Strategic management is the process of building capabilities that allow a firm to create value for customers, shareholders, and society while operating in competitive markets.

- Strategy entails: specifying the organization’s mission, vision, and objectives; developing policies and plans to execute the vision; and allocating resources to implement those policies and plans.

- Strategy is largely about using internal assets to create a value-added proposition. This helps to capture opportunities in the competitive environment while avoiding threats.

- Experts in the field of strategy define the potential components of strategy and the different forms strategy can take.

Key Terms

- balanced scorecard

-

A strategic performance management tool used by managers to track the execution of activities within their control and monitor the consequences of these actions.

- strategic management

-

The art and science of formulating, implementing, and evaluating cross-functional decisions that will enable an organization to achieve its objectives.

- strategy

-

A plan of action intended to accomplish a specific goal.

Strategy involves the action plan of a company for building competitive advantage and increasing its triple bottom line over the long-term. The action plan relates to achieving the economic, social, and environmental performance objectives; in essence, it helps bridge the gap between the long-term vision and short-term decisions.

Strategic Management

Strategic management is the process of building capabilities that allow a firm to create value for customers, shareholders, and society while operating in competitive markets (Nag, Hambrick & Chen 2006). It entails the analysis of internal and external environments of firms to maximize the use of resources in relation to objectives (Bracker 1980). Strategic management can depend upon the size of an organization and the proclivity to change the organization’s business environment.

The process of strategic management entails:

- Specifying the organization’s mission, vision, and objectives

- Developing policies and plans that are designed to achieve these objectives

- Allocating resources to implement these policies and plans

As an example, let’s take a company that wants to expand its current operations to producing widgets. The company’s strategy may involve analyzing the widget industry along with other businesses producing widgets. Through this analysis, the company can develop a goal for how to enter the market while differentiating from competitors’ products. It could then establish a plan to determine if the approach is successful.

Keeping Score

A balanced scorecard is a tool sometimes used to evaluate a business’s overall performance. From the executive level, the primary starting point will be stakeholder needs and expectations (i.e., financiers, customers, owners, etc.). Following this, inputs such as objectives, operations, and internal processes will be developed to achieve these expectations.

Another way to keep score of a strategy is to visualize it using a strategy map. Strategy maps help to illustrate how various goals are linked and provide trajectories for achieving these goals.

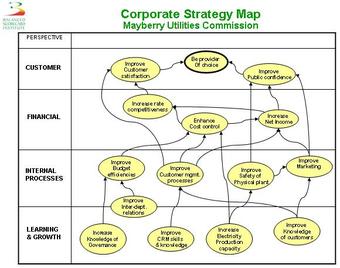

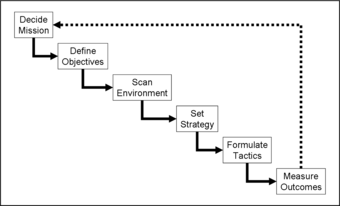

Strategy map

This image is an example of a strategy map for a public-sector organization. It shows how various goals are linked and providing trajectories for achieving these goals.

Common Approaches to Strategy

Richard Rumelt

In 2011, Professor Richard P. Rumelt described strategy as a type of problem solving. He outlined a perspective on the components of strategy, which include:

- Diagnosis: What is the problem being addressed? How do the mission and objectives imply action?

- Guiding Policy: What framework will be used to approach the operations? (This, in many ways, should be the decision of a given competitive advantage relative to the competition.)

- Action Plans: What will the operations look like (in detail)? How will the processes be enacted to align with the guiding policy and address the issue in the diagnosis?

Michael Porter

In 1980, Michael Porter wrote that formulation of competitive strategy includes the consideration of four key elements:

- Company strengths and weaknesses

- Personal values of the key implementers (i.e., management or the board)

- Industry opportunities and threats

- Broader societal expectations

Henry Mintzberg

Henry Mintzberg stated that there are prescriptive approaches (what should be) and descriptive approaches (what is) to strategic management. Prescriptive schools are “one size fits all” approaches that designate best practices, while descriptive schools describe how strategy is implemented in specific contexts. No single strategic managerial method dominates, and the choice between managerial styles remains a subjective and context-dependent process. As a result, Mintzberg hypothesized five strategic types:

- Strategy as plan: a directed course of action to achieve an intended set of goals; similar to the strategic planning concept

- Strategy as pattern: a consistent pattern of past behavior with a strategy realized over time rather than planned or intended (where the realized pattern was different from the intent, Mintzberg referred to the strategy as emergent)

- Strategy as position: locating brands, products, or companies within the market based on the conceptual framework of consumers or other stakeholders; a strategy determined primarily by factors outside the firm

- Strategy as ploy: a specific maneuver intended to outwit a competitor

- Strategy as perspective: executing strategy based on a “theory of the business” or a natural extension of the mindset or ideological perspective of the organization

Example

A company wants to expand its current operations to produce widgets. The company’s strategy may involve analyzing the widget industry along with other businesses producing widgets. Through this analysis, the company can develop a goal for how to enter the market while differentiating from competitors’ products. It could then establish a plan to determine if the approach is successful.

12.1.2: The Importance of Strategy

Strategic management is critical to organizational development as it aligns the mission and vision with operations.

Learning Objective

Evaluate the implications of the three key questions defining strategic planning

Key Points

- Strategic management seeks to coordinate and integrate the activities of the various functional areas of a business in order to achieve long-term organizational objectives.

- The initial task in strategic management is typically the compilation and dissemination of the vision and the mission statement. This outlines, in essence, the purpose of an organization.

- Strategies are usually derived by the top executives of the company and presented to the board of directors in order to ensure they are in line with the expectations of the stakeholders.

- The implications of the selected strategy are highly important. These are illustrated through achieving high levels of strategic alignment and consistency relative to both the external and internal environment.

- All strategic planning deals with at least one of three key questions: “What do we do?” “For whom do we do it?” and “How do we excel?” In business strategic planning, the third question refers more to beating or avoiding competition.

Key Terms

- mission statement

-

A declaration of the overall goal or purpose of an organization.

- board of directors

-

A group of people elected by stockholders to establish corporate policies and make managerial decisions.

Strategic management is critical to the development and expansion of all organizations. It represents the science of crafting and formulating short-term and long-term initiatives directed at optimally achieving organizational objectives. Strategy is inherently linked to a company’s mission statement and vision; these elements constitute the core concepts that allow a company to execute its goals. The company strategy must constantly be edited and improved to move in conjunction with the demands of the external environment.

Strategy and Management

As a result of its importance to the business or company, strategy is generally perceived as the highest level of managerial responsibility. Strategies are usually derived by the top executives of the company and presented to the board of directors in order to ensure they are in line with the expectations of company stakeholders. This is particularly true in public companies, where profitability and maximizing shareholder value are the company’s central mission.

The implications of the selected strategy are also highly important. These are illustrated through achieving high levels of strategic alignment and consistency relative to both the external and internal environment. In this way, strategy enables the company to maximize internal efficiency while capturing the highest potential of opportunities in the external environment.

Key Strategic Questions

The initial task in strategic management is to compile and disseminate the organization’s vision and mission statement. These outline, in essence, the purpose of the organization. Additionally, they specify the organization’s scope of activities. Strategic planning is the formal consideration of an organization’s future course, and all strategic planning deals with at least one of three key questions:

- What do we do?

- How do we do it?

- How do we excel?

In business-related strategic planning, the third question refers more to beating or avoiding competition.

Strategic management is the art, science, and craft of formulating, implementing, and evaluating cross-functional decisions that will enable an organization to achieve its long-term objectives. It involves specifying the organization’s mission, vision, and objectives; developing policies and plans to achieve these objectives; and then allocating resources to implement the policies and plans. Strategic management seeks to coordinate and integrate the activities of a company’s various functional areas in order to achieve long-term organizational objectives.

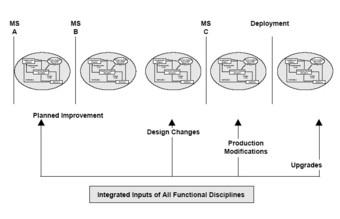

Product improvement strategies

This strategy map illustrates an example of how product improvements are designed and implemented. Improvements move from the original plan, to design changes, to production modification, to deployments, to upgrades.

12.1.3: Making Strategy Effective

Effective strategies must be suitable, feasible, and acceptable to stakeholders.

Learning Objective

Apply the three criteria for strategic efficacy identified by Johnson, Scholes and Whittington and the 11 forces that should be incorporated into strategic consideration as argued by Will Mulcaster

Key Points

- Johnson, Scholes, and Whittington suggest evaluating strategic options based on three key criteria: suitability, feasibility, and acceptability.

- Suitability refers to the overall rationale of the strategy and its fit with the organization’s mission.

- Feasibility refers to whether or not the organization has the resources necessary to implement the strategy.

- Acceptability is concerned with stakeholder expectations and the expected outcomes of implementing the strategy.

- Will Mulcaster provides an additional 11 strategic forces which may impact the effectiveness of a given strategy.

Key Terms

- effectiveness

-

The capability of producing a desired result.

- strategy

-

A plan of action intended to accomplish a specific goal.

Effectiveness is the capability to produce a desired result. Strategy is considered effective when short-term and long-term objectives are accomplished and are in line with the mission, vision, and stakeholder expectations. This requires upper management to recognize how each organizational component combines to create a competitive operational process.

Suitability, Feasibility, and Acceptability

With the above framework in mind, a number of academics have proposed perspectives on strategic effectiveness. Johnson, Scholes, and Whittington suggest evaluating the potential success of a strategy based on three criteria:

- Suitability deals with the overall rationale of the strategy. One method of assessing suitability is using a strength, weakness, opportunity, and threat (SWOT) analysis. A suitable strategy fits the organization’s mission, reflects the organization’s capabilities, and captures opportunities in the external environment while avoiding threats. A suitable strategy should derive competitive advantage(s).

- Feasibility is concerned with whether or not the organization has the resources required to implement the strategy (such as capital, people, time, market access, and expertise). One method of analyzing feasibility is to conduct a break-even analysis, which identifies if there are inputs to generate outputs and consumer demand to cover the costs involved.

- Acceptability is concerned with the expectations of stakeholders (such as shareholders, employees, and customers) and any expected financial and non-financial outcomes. It is important for stakeholders to accept the strategy based on the risk (such as the probability of consequences) and the potential returns (such as benefits to stakeholders). Employees are particularly likely to have concerns about non-financial issues such as working conditions and outsourcing. One method of assessing acceptability is through a what-if analysis, identifying best and worst case scenarios.

SWOT Analysis

Here is an example of the SWOT analysis matrix.

Mulcaster’s Managing Forces Framework

Will Mulcaster argued that while research has been devoted to generating alternative strategies, not enough attention has been paid to the conditions that influence the effectiveness of strategies and strategic decision-making. For instance, it can be seen in retrospect that the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009 could have been avoided if banks had paid more attention to the risky nature of their investments. However, knowing in hindsight cannot address how banks should change the ways they make future decisions.

Mulcaster’s Managing Forces Framework addresses this issue by identifying 11 forces that should be taken into account when making strategic decisions and implementing strategies:

- Time

- Opposing forces

- Politics

- Perception

- Holistic effects

- Adding value

-

Incentives

- Learning capabilities

- Opportunity cost

- Risk

- Style

While this is quite a bit to consider, the key is to be as circumspect as possible when analyzing a given strategy. In many ways it is similar to the potential issues a scientist faces. A scientist must always be objective and conduct experiments without a bias toward a specific outcome. Scientists don’t prove something to be true; they test hypotheses. Similarly, strategists must not create a strategy to get to an end point; they must instead create a series of likely endpoints based on organizational inputs and operational approaches. Uncertainty is key, allowing strategic improvement for higher efficacy.

Example

A firm may perform a break-even analysis to determine if a strategy is feasible. The break-even point (BEP) is the point at which costs or expenses and revenue are equal: there is no net loss or gain, so the company has “broken even.” For example, if a business sells fewer than 200 tables each month, it will make a loss; if it sells more, it will make a profit. With this information, managers could determine if they expected to be able to make and sell 200 tables per month and then implement a strategy that is in accordance with their projections.

12.1.4: Differences Between Strategic Planning at Small Versus Large Firms

The effectiveness of a strategy is heavily dependent upon the size of the organization.

Learning Objective

Apply the size of a firm to the basic strategic management theories

Key Points

- Size is highly relevant to organizational strategy and structure, and understanding the influencing factors is important for management to elect optimal strategic plans.

- A global or transnational organization may employ a more structured strategic management model due to its size, scope of operations, and need to encompass stakeholder views and requirements.

- A small or medium enterprise may employ an entrepreneurial approach due to its comparatively smaller size and scope of operations and its limited access to resources.

- Smaller firms also tend to focus more on differentiation due to an inability to achieve scale economies. Similarly, larger firms tend to have more cost-sensitive strategic capabilities.

- No single strategic managerial method dominates, and the choice of managerial style remains a subjective and context-dependent process.

Key Terms

- structured interview

-

A quantitative research method commonly employed in survey research where each potential employee is asked the same questions in the same order.

- entrepreneurial

-

Having the spirit, attitude or qualities of a person who organizes and operates a business venture.

- structured

-

The state of being organized.

Strategic management can depend on the size of an organization and the proclivity of change in its business environment. In the U.S., an SME (small and medium enterprise) refers to an organization with 500 employees or less, while an MNE (multinational enterprise) refers to a global organization with a much larger operational scope. Size is highly relevant to organizational strategy and structure, and understanding the influencing factors is important for management to elect optimal strategic plans.

Strategic Management in Large Organizations

MNEs (multinational enterprises) may employ a more structured strategic management model due to its size, scope of operations, and need to encompass stakeholder views and requirements. MNEs are tasked with aligning complex and often dramatically different processes, demographic considerations, employees, legal systems, and stakeholders. Due to the wide variance and high volume of business, upper management needs stringent control systems embedded in the managerial strategy to enable predictability and conformity to mission, vision, and values.

For example, McDonald’s operates restaurants all over the globe. They have different menus in China than in France due to differing consumer tastes. They also have different hiring standards, regulations, and sourcing methods. How does management create a strategy that doesn’t confine these geographic regions (and lose localization) yet still maintains each region’s alignment with the mission, vision, and branding of McDonald’s?

Low-cost Strategy

Ideally, McDonald’s can construct careful strategic models and systems which control the critical components of the operations without hindering the localization. From a strategic point of view, this involves creating a system of quality control, reporting, and localization that maintains the competitive advantage of scale economies and strong branding. Large firms such as McDonald’s often achieve better scale economies and thus can pursue low-cost strategies. This requires enormous managerial competency with meticulously crafted strategies at various levels in the organization (including corporate, functional, and regional).

Strategic Management in Small Firms

SMEs (small and medium enterprises) may employ an entrepreneurial approach due to its comparatively smaller size and scope of operations and limited access to resources. A smaller organization needs to be agile, adaptable, and flexible enough to develop new strengths and capture niche opportunities within a competitive industry with bigger players. This requires fluidity in strategy while simultaneously maintaining a predetermined vision and mission statement.

Achieving this requires a great deal of balance; it often requires a strategy that is created to enable multiple paths to the same objectives. Small firm strategies often incorporate flexibility to capture new opportunities as they arise, as opposed to maintaining an already well-established competitive advantage.

Differentiation

In most cases, low-cost strategies require substantial economies of scale. Because of this constraint, smaller firms most often use differentiation strategies that focus on innovation over efficiency. Enabling creativity and innovation is strategically difficult to do as it requires a hands-off approach that empowers autonomy over structure. Innovate ideas are primarily trial and error, and so instilling creativity into a strategic process is also a high-risk approach.

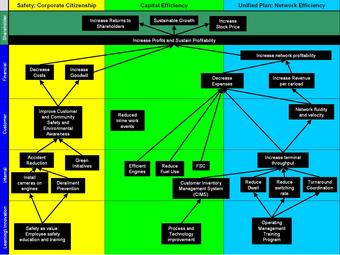

Example of a strategy map

This image is an example of a strategy map that organizes a firm’s stakeholder interests. You can see the firm’s three main goals across the top (corporate citizenship, capital efficiency, and network efficiency) and the categories of potential actions down the left (learning innovation, internal action, customer action, and financial action).

12.1.5: The Impact of External and Internal Factors on Strategy

Analysis of both internal factors and external conditions is central to creating effective strategy.

Learning Objective

Examine the discrepancies between internal proficiency and external factors to capture strategic value

Key Points

- Strategic management is the managerial responsibility to achieve competitive advantage through optimizing internal resources while capturing external opportunities and avoiding external threats.

- While different businesses have different internal conditions, it is easiest to view these potential attributes as generalized categories. A value chain is a common tool used to accomplish this.

- A value chain identifies the supporting activities (employee skills, technology, infrastructure, etc.) and the primary activities (acquiring inputs, operations, distribution, sales, etc.) that can potentially create profit.

- The external environment is even more diverse and complex than the internal environment, and there are many effective models to discuss, measure, and analyze it (i.e., Porter’s Five Force, SWOT Analysis, PESTEL framework, etc.).

- With both the internal value chain and external environment in mind, upper management can reasonably derive a set of strategic principles which internally leverage strengths and externally capture opportunities to create profits.

Key Term

- analysis

-

The process of breaking down a substance into its constituent parts, or the result of this process.

Strategic management is the managerial responsibility to achieve competitive advantage through optimizing internal resources while capturing external opportunities and avoiding external threats. This requires carefully crafting a structure, series of objectives, mission, vision, and operational plan. Recognizing the way in which internally developed organizational attributes will interact with the external competitive environment is central to successfully implementing a given strategy—and thus creating profitability.

Internal Conditions

The internal conditions are many and varied depending on the organization (just as the external factors in any given industry will be). However, management has some strategic control over how these various internal conditions interact. The achievement of synergy in this process derives competitive advantage. While different businesses have different internal conditions, it is easiest to view these potential attributes as generalized categories.

A value chain is a common tool used to identify each moving part. It is a useful mind map for management to fill in during the derivation of internal strengths and weakness. A value chain includes supports activities and primary activities, each with its own components.

Supports Activities

- Firm infrastructure: the organizational structure, mission, hierarchy and upper management

- Human resource management: the skills embedded in the organization through human resources

- Technology: the technological strengths and weaknesses (such as patents, machinery, IT, etc.)

- Procurement: a measure of assets, inventory, and sourcing

Primary Activities

- Inbound logistics: deriving inputs for operational process

- Operations: running inputs through organizational operations

- Outbound logistics: shipping, warehousing, and inventorying final products

- Marketing and sales: building a brand, selling products, and identifying retail strategies and opportunities

- Service: following up with customers to ensure satisfaction, provide and fulfill warranties, etc.

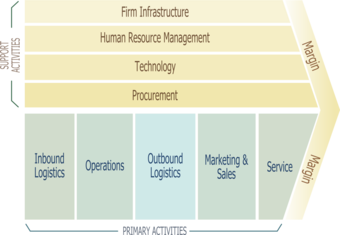

Michael Porter’s value chain

This model, created by Michael Porter, demonstrates how support and primary activities add up to potential margins (and potential competitive advantage). Support activities include HR management and technology; primary activities include operations, marketing and sales, and service.

External Opportunities and Threats

The external environment is even more diverse and complex than the internal environment. There are many effective models to discuss, measure, and analyze the external environment (such as Porter’s Five Force, SWOT Analysis, PESTEL framework, etc.). For the sake of this discussion, we will focus on the following general strategic concerns as they pertain to opportunities and threats:

- Markets (customers): Demographic and socio-cultural considerations, such as who the customers are and what they believe, are critical to capturing market share. Understanding the needs and preferences of the markets is essential to providing something that will have a demand.

- Competition: Knowing who else is competing and how they are strategically poised is also key to success. Consider the size, market share, branding strategy, quality, and strategy of all competitors to ensure a given organization can feasibly enter the market.

- Technology: Technological trajectories are also highly relevant to success. Does the manufacturing process of the product have new technologies which are more efficient? Has a disruptive technology filled the need that was currently being filled?

- Supplier markets: Suppliers have great power as they control the necessary inputs to an organization’s operational process. For example, smartphones require rare earth materials; if these materials are increasingly scarce, the price points will rise.

- Labor markets: Acquiring key talent and satisfying employees (relative to the competition) is critical to success. This requires an understanding of unions and labor laws in regions of operation.

- The economy: Economic recessions and booms can change spending habits drastically, though not always as one might expect. While most industries suffer during recession, some industries thrive. It is important to know which economic factors are opportunities and which are threats.

- The regulatory environment: Environmental regulations, import/export tariffs, corporate taxes, and other regulatory concerns can poise high costs on an organization. Integrating this into a strategy ensures feasibility.

While there are many other external considerations one could take into account during the strategic planning process, this list gives a good outline of what must be considered in order to minimize unexpected threats or missed opportunities.

Strategic Analysis

With both the internal value chain and external environment in mind, upper management can reasonably derive a set of strategic principles that internally leverage strengths while externally capturing opportunities to create profits—and hopefully advantages over the competition.

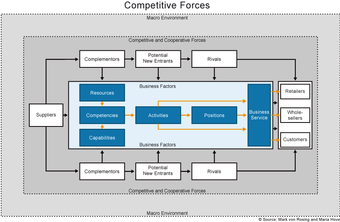

Competitive and cooperative forces

This chart diagrams the external factors that should be considered when analyzing a firm’s strategy. Competitive and cooperative forces include rivals, new entrants, suppliers, and retailers; business factors include resources and capabilities.

12.2: External Inputs to Strategy

12.2.1: Porter’s Five Forces

Michael Porter, a leading business analyst and professor, identified five critical external factors that affect strategy in any industry.

Learning Objective

Apply Porter’s Five Forces to the external landscape to derive optimal strategies

Key Points

- Porter’s Five Forces include: threat of new entrants (also know as barriers to entry), threat of substitutes, rivalry, bargaining power of suppliers, and bargaining power of buyers.

- Managers use the Five Forces model to help identify opportunities and threats or to evaluate decisions in the context of their organization’s environment.

- Attractiveness refers to the overall industry profitability. An “unattractive” industry is one in which the combination of the Five Forces drives down overall profitability.

- In analyzing these five factors, it is useful to rate each category as an external risk factor (i.e., low, medium, or high). Ideal industries have low threats from each of these forces (i.e., low buy power, low rivalry, low risk of new entrants, etc.).

- This model is a useful for the strategic derivation of managers; it allows them to narrow down their focus on specific key issues within a given industry.

Key Terms

- substitute

-

A replacement or stand-in for something that achieves a similar result or purpose.

- entrant

-

Participant.

Michael Porter, a leading business analyst and professor at Harvard Business School, has identified five key forces that affect the strategy of any industry. His list, Porter’s Five Forces, draws upon industrial organization (IO) economics to derive forces that determine the competitive intensity—and therefore attractiveness—of a market.

Industry Attractiveness

Attractiveness refers to the overall industry profitability. An “unattractive” industry is one in which the combination of the Five Forces drives down overall profitability. A very unattractive industry would be one approaching “pure competition.” In this state, available profits for all firms are driven to normal profit rates. In analyzing the following five factors, it is useful to rate each category as an external risk factor (i.e., low, medium, or high). Ideal industries will have low threats from each of these forces (i.e., low buy power, low rivalry, low risk of new entrants, etc.).

The Five Forces

Porter’s Five Forces include:

- Threat of new entrants (or barriers to entry): From the view of current incumbents, profitable markets that yield high returns will attract new firms. This results in many new competitors and eventually decreases profitability for all firms in the industry. Unless the entry of new firms can be blocked by incumbents, the abnormal profit rate will tend toward zero (also known as “perfect competition”). From the perspective of new entrants, high barriers to entry mean that the capital costs of getting into the industry make it difficult to compete with current incumbents.

- Threat of substitute products or services: The existence of products outside of the realm of the common product boundaries, which fulfill the same need, increases the propensity of customers to switch to alternatives. This should not be confused with competitors’ similar products; it is instead a different product that fills the same need. Take transportation as an example: General Motors (GM) would view city subways as a substitute to someone buying a new car.

- Rivalry: For most industries, the intensity of competitive rivalry is the major determinant of the competitiveness of the industry. This involves how many firms are in the industry and how their competitive dynamics reduce profitability. Airlines have extremely high rivalry, for example.

- Bargaining power of buyers: The bargaining power of customers is also described as the market of outputs. It is the ability of customers to put the firm under pressure, which also affects the customer’s sensitivity to price changes. Picture a supply and demand curve: if the supply greatly outstrips the demand, the buyers have more power than the suppliers.

- Bargaining power of suppliers: The bargaining power of suppliers is also described as the market of inputs. When there are few substitutes, suppliers of raw materials, components, labor, and services (such as expertise) to the firm can be a source of power over the firm. Suppliers can refuse to work with the firm or charge excessively high prices for unique resources. Similar to power of buyers, this bargaining power relies on scarcity and basic economics of supply and demand.

Strategic Implications

Managers use the Five Forces model to help identify opportunities or evaluate decisions in the context of the environment. Often, the Five Forces are mapped against a SWOT analysis to develop a corporate strategy. To complete a Five Forces analysis, it is often best to build a grid on a piece of paper and label each section. Filling in each section to develop a view of the industry can help managers determine if the industry is truly competitive, a monopoly, or an oligopoly. An important question to ask is: “What will make a company able to compete in this environment? “

Porter’s Five Forces

This image illustrates the important factors within Porter’s Five Forces model.

12.2.2: Limitations of the Five-Forces View

Like most models, Porter’s Five Forces has advantages and limitations when applied to strategic planning processes.

Learning Objective

Employ Porter’s Five Forces in a meaningful strategic way, with a thorough understanding of the potential limitations

Key Points

- Strategy consultants will use Porter’s Five Forces framework when making a qualitative evaluation of a firm’s strategic position; however, it is only one tool of many and is not infallible.

- According to Porter, the Five Forces model should be used at the broader level of an entire industry; it is not designed to be used at a smaller group or market level.

- Another limitation, which Porter’s model shares with most competitive frameworks, is that of chronological thinking. Porters model is inherently static, representing only aspects of the present day.

- The purpose of the model is brainstorming: a thinking exercise to demonstrate the subjective attractiveness of a given industry landscape. It is not designed to decide optimal industries with certainty.

Key Terms

- Porter’s Five Forces Model

-

A business tool to qualitatively measure business framework.

- framework

-

A basic conceptual structure.

Strategy consultants will use Porter’s Five Forces framework when making a qualitative evaluation of a firm’s strategic position; however, it is only one tool of many and is not infallible. The framework is only a starting point or checklist. Like most models, Porter’s Five Forces has advantages and limitations when applied to strategic planning processes; one must understand how it is designed to be used and recognize its limitations.

Single Industry vs. Multiple Industry Operation

According to Porter, the Five Forces model is best used at the broader level of an entire industry. Assessing at the smaller levels of sectors, competitive groups, or general markets will not yield strategically relevant information. Porter’s factors are specifically determined based on the industry level. Large organizations analyzing markets that are too broad and smaller organizations focusing on specific sectors need to keep this limitation in mind when using this framework.

Some firms operate in only one industry, while others operate in multiple industries. A firm that competes in a single industry will realistically only need to assess the industry it is in (and perhaps other supporting industries depending upon the situation). For diversified companies, however, the first fundamental issue in corporate strategy is the selection of industries (lines of business) in which the company should focus. Following this, each line of business should develop its own industry-specific Five Forces analysis. The average Global 1,000 company competes in approximately 52 industries (lines of business). These large firms require a diversified series of analyses.

Adaptability and Evolution

Another limitation—which Porter’s model shares with most competitive frameworks—is that of chronological thinking. Porters model is inherently static, representing only aspects of the present day (and perhaps those that are easily predicted within the short term). As strategic planning involves long-term objectives and the pursuit of adaptability, Porter’s model is too static to be relied upon outside of short- to medium-term objectives.

Uncertainty

It has been noted that conclusions from the Five Forces model are highly debatable. This is deliberate, as models are designed to spark discussion and underline key concerns. However, false conclusions can be reached when models are taken as certain. The purpose of the model is brainstorming: a thinking exercise to demonstrate the subjective attractiveness of a given industry landscape. It is not designed to decide optimal industries with certainty. In short, conclusions should be taken in the context of the broader strategic discussion and not as opposed to a stand-alone recommendation.

Porter’s Five Forces

This diagram represents the components of Porter’s Five Forces model: (1) threat of new entrants, (2) threat of established rivals, (3) threat of substitute products, (4) bargaining power of buyers, and (5) bargaining power of suppliers.

12.2.3: The PESTEL and SCP Frameworks

PESTEL and SCP frameworks are models for understanding different industry and market factors that impact strategic management.

Learning Objective

Apply PESTEL and SCP frameworks to industries in which incumbents operate

Key Points

- A PESTEL analysis looks at the six most common macro-environmental factors (political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal) in order to understand their interaction with the organization.

- A PESTEL analysis is a part of the external strategic analysis when conducting market research; it gives an overview of the different macro-environmental factors that the company has to take into consideration.

- According to the structure-conduct-performance (SCP) approach, an industry’s performance depends on the conduct of its firm, which is dependent on its structure.

- Components that make up the SCP model for industrial organization include: basic conditions, structure, conduct, performance, and government policy.

- While the PESTEL and SCP models share many similarities, it is useful for managers to view the industry from both frameworks as they decide upon optimal operating strategies.

Key Term

- environmental scanning

-

The study and interpretation of the political, economic, social, and technological events and trends that influence a business, an industry, or even a total market

PESTEL Analysis

A PESTEL analysis looks at the six most common macro-environmental factors to understand their interactions. The acronym stands for political, economic, social, technological changes, ecology, and legislation. A PESTEL analysis is a useful strategic tool for understanding market growth or decline, business position, potential, and direction for operations. The basic premise behind this framework, from a strategy perspective, is to identify opportunities and threats in the market.

PESTEL Factors

- Political factors include how, and to what degree, a government intervenes in the economy. Specifically, political factors include areas such as tariffs, political instability, and other policy-based obstacles that businesses encounter in a given region.

- Economic factors include economic growth, interest rates, exchange rates, and the rate of inflation. Economic factors are by far the easiest to quantify, and they provide a basic framework for capital exchange and consumer purchasing ability.

- Social factors include the cultural aspects of the environment, such as health consciousness, population growth rate, age distribution, career attitudes, and emphasis on safety. Often referred to socio-demographic factors, they largely consist of preferences and attitudes displayed by different groups of individuals within a given market. Social factors can be very difficult to measure with certainty.

- Technological factors include research and development (R&D), automation, technology incentives, and the rate of technological change. Disruptive innovations can dramatically alter an industry and change who is best poised for competition. Carefully monitoring these factors on a daily basis is crucial to a company’s success and has grown in importance over the years.

- Environmental factors include ecological and environmental aspects such as weather, climate, and climate change. Industries like tourism, farming, and insurance are especially affected by these factors. Growing awareness of the potential impacts of climate change is affecting how companies operate and the products they offer, both creating new markets and diminishing or destroying existing ones.

- Legal factors include discrimination laws, consumer laws, antitrust laws, employment laws, and health and safety laws. These factors can affect how a company operates, its costs, and the demand for its products.

SCP Analysis

According to the structure-conduct-performance (SCP) approach, an industry’s performance (or the success of an industry in producing benefits for the consumer) depends on the conduct of its firm. The conduct of the firm, in turn, is dependent on its structure (or factors that determine the competitiveness of the market).

The structure of the industry depends on basic conditions such as technology and demand for a product. This creates a linear relationship of sorts, where the structural inputs can impact the conduct and strategy of the firm, leading to better (or worse) performance.

Taken into account alongside the PESTEL framework, management should carefully consider and define the structure of a given industry. This structure will provide critical inputs for the broader industry, which in turn will impact the conduct of the organization through strategic integration. If this process is accomplished effectively—and management has integrated the external structure with the internal conduct strategically—higher performance can then be derived.

12.2.4: Competitive Dynamics

Crafting an effective strategy requires understanding the competitive dynamics of the space in which the business operates.

Learning Objective

Identify critical competitive components that directly influence strategic development

Key Points

- Competitor analysis is an assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of current and potential competitors. This analysis provides both an offensive and defensive strategic context in order to identify opportunities and threats.

- Competitor analysis requires the specific selection of key success factors within an industry; it also requires the qualitative measurement of accomplishing these for both the firm and its key competitors.

- Competitor profiling coalesces all of the relevant sources of competitor analysis into one framework to support efficient and effective strategy formulation, implementation, monitoring, and adjustment.

- By identifying key competitors and relative strengths and weaknesses, organizations can react more quickly and effectively from a strategic perspective.

Key Terms

- assessment

-

An appraisal or evaluation.

- dynamic

-

Changeable; active; in motion, usually as the result of an external force.

Competition in Business

Merriam-Webster defines competition in business as “the effort of two or more parties acting independently to secure the business of a third party by offering the most favorable terms.” The competition is a moving-target, ever-evolving and adapting to better capture market share and profitability; therefore competition is a critical area of analysis for strategic managers. Observing and predicting competitive movements and dynamics is a key to success and a primary responsibility of upper management.

The Dynamic Model of Competition

The dynamic model of the strategy process is a way of understanding how strategic actions occur. It recognizes that strategic planning is dynamic; that is, strategy-making involves a complex pattern of actions and reactions. It is partially planned and partially unplanned. Competitive dynamics thus looks at how competitive firms act and react.

Competitive Dynamics

In marketing and strategic management, competitor analysis is an assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of current and potential competitors. This analysis provides both an offensive and defensive strategic context in order to identify opportunities and threats. Competitor profiling coalesces all of the relevant sources of competitor analysis into one framework to support efficient and effective strategy formulation, implementation, monitoring, and adjustment.

Components of Competitor Analysis

Competitor analysis is an essential component of corporate strategy. It is argued that most firms do not conduct this type of analysis systematically enough. Instead, many enterprises operate on conjectures and informal impressions gathered from information received about competitors. As a result, traditional environmental scanning places many firms at risk of dangerous competitive “blind spots” due to a lack of robust competitor analysis.

Example of Competitor Profiling

The folio plot visualizes the relative market share of a portfolio of products versus the growth of their market. The circles differ in size by their sales volume. Note that the highest-selling product, Dorian, shows the highest market growth and a high (though not the highest) market share; the lowest-selling, Zodial, shows both low market growth and low market share.

Competitor analysis requires the specific selection of key success factors within an industry. It also requires the qualitative measurement of accomplishing these for both the firm and its key competitors. For example, consider that customer service, quality, and brand perception are the key success factors in retail fashion. In this case, Ralph Lauren should identify key competitors (Liz Claiborne, Calvin Klein, etc.) and provide a numeric score of their success or failure in each category. Through this competitive analysis, Ralph Lauren can improve its competition.

Competitor profiling facilitates this strategic objective in three important ways:

- First, profiling can reveal strategic weaknesses in rivals that the firm may exploit.

- Second, the proactive stance of competitor profiling can allow the firm to anticipate its rivals’ strategic response to the firm’s planned strategies, the strategies of other competing firms, and changes in the environment.

- Third, this proactive knowledge can give the firm strategic agility. Offensive strategy can be implemented more quickly in order to exploit opportunities and capitalize on strengths. Similarly, defensive strategy can be employed more deftly in order to counter the threat of rival firms exploiting the firm’s own weaknesses.

12.3: Internal Analysis Inputs to Strategy

12.3.1: The Mission Statement

A mission statement defines the fundamental purpose of an organization or enterprise.

Learning Objective

Outline the appropriate content necessary to construct a comprehensive mission statement

Key Points

- A mission statement is generated to retain consistency in overall strategy and to communicate core organizational goals to all stakeholders.

- The business’s owners and upper managers develop the mission statement and uphold it as a standard across the organization. It provides a strategic framework by which the organization is expected to abide.

- In a best-case scenario, an organization conducts internal and external assessments relative to the mission statement to ensure it is being upheld.

- A mission statement informs the key market, contribution, and distinction of an organization. It describes what the organization does, why it does so, and how it excels.

Key Terms

- stakeholder

-

A person or organization with a legitimate interest in a given situation, action, or enterprise.

- mission

-

A set of tasks that fulfills a purpose or duty; an assignment set by an employer.

A mission statement defines the purpose of a company or organization. The mission statement guides the organization’s actions, spells out overall goals, and guides decision making. The mission statement is generated to retain consistency in overall strategy and to communicate core organizational goals to all stakeholders. The business’s owners and upper managers develop the mission statement and uphold it as a standard across the organization. It provides a strategic framework by which the organization is expected to abide.

Mission statement

An example of a mission statement, which includes the organization’s aims and stakeholders and how it provides value to these stakeholders.

In a best-case scenario, an organization conducts internal and external assessments relative to the mission statement. The internal assessment should focus on how members inside the organization interpret the mission statement. The external assessment, which includes the business’s stakeholders, is valuable since it offers a different perspective. Discrepancies between these two assessments can provide insight into the effectiveness of the organization’s mission statement.

Contents

Effective mission statements start by articulating the organization’s purpose. Mission statements often include the following information:

- Aim(s) of the organization

- The organization’s primary stakeholders, including clients/customers, shareholders, congregation, etc.

- How the organization provides value to these stakeholders, that is, by offering specific types of products or services

- A declaration of an organization’s core purpose

According to business professor Christopher Bart, the commercial mission statement consists of three essential components:

- Key market – Who is your target client/customer? ( generalize if necessary)

- Contribution – What product or service do you provide to that client?

- Distinction – What makes your product or service so unique that the client would choose you?

Assimilation

To be truly effective, an organizational mission statement must be assimilated into the organization’s culture (as the theory states). Leaders have the responsibility of communicating the vision regularly, creating narratives that illustrate the vision, acting as role-models by embodying the vision, creating short-term objectives compatible with the vision, and encouraging employees to craft their own personal vision that is compatible with the organization’s overall vision.

12.3.2: Porter’s Competitive Strategies

Michael Porter classifies competitive strategies as cost leadership, differentiation, or market segmentation.

Learning Objective

Discuss the value of using Porter’s competitive strategies of cost leadership, differentiation, and market segmentation

Key Points

- Michael Porter defines three strategy types that can attain competitive advantage. These strategies are cost leadership, differentiation, and market segmentation (or focus).

- Cost leadership is about achieving scale economies and utilizing them to produce high volume at a low cost. Margins may be narrower, but quantity is larger, enabling high revenue streams.

- Differentiation is creating a unique service or product offering, either through good branding or strong internal skills. This strategy aims at offering something difficult to copy and is strongly associated with an organization’s brand.

- Market segmentation strategy is narrower in scope. Both cost leadership and differentiation are relatively broad in market scope and can encompass both strategic advantages on a smaller scale.

- Porter warns that companies who try to accomplish both cost leadership and differentiation may fall into the “hole in the middle”; he notes that specializing is the ideal strategic approach.

Key Terms

- Market Share

-

Percentage of a specific market held by a company.

- competitive advantage

-

Something that places a company or a person above the competition.

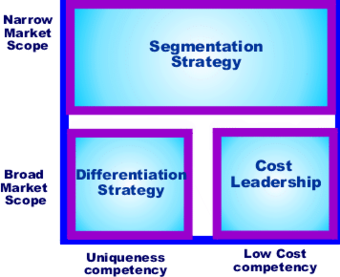

Michael Porter described a category scheme consisting of three general types of strategies commonly used by businesses to achieve and maintain competitive advantage. These three strategies are defined along two dimensions: strategic scope and strategic strength. Strategic scope is a demand-side dimension and considers the size and composition of the market the business intends to target. Strategic strength is a supply-side dimension and looks at the strength or core competency of the firm.

Porter identifies two competencies as most important: product differentiation and product cost (efficiency). He originally ranked each of the three dimensions (level of differentiation, relative product cost, and scope of target market) as either low, medium, or high and juxtaposed them in a three-dimensional matrix. That is, the category scheme was displayed as a 3x3x3 cube; however, most of the twenty-seven combinations were not viable.

Cost Leadership, Differentiation, and Market Segmentation

Porter simplified the scheme by reducing it to the three most effective strategies: cost leadership, differentiation, and market segmentation (or focus). He characterizes each as the following:

- Cost leadership pertains to a firm’s ability to create economies of scale though extremely efficient operations that produce a large volume. Cost leaders include organizations like Procter & Gamble, Walmart, McDonald’s and other large firms generating a high volume of goods that are distributed at a relatively low cost (compared to the competition).

- Differentiation is less tangible and easily defined, yet still represents an extremely effective strategy when properly executed. Differentiation refers to a firm’s ability to create a good that is difficult to replicate, thereby fulfilling niche needs. This strategy can include creating a powerful brand image, which allows the organization to sell its products or services at a premium. Coach handbags are a good example of differentiation; the company’s margins are high due to the markup on each bag (which mostly covers marketing costs, not production).

- Market segmentation is narrow in scope (both cost leadership and differentiation are relatively broad in scope) and is a cross between the two strategies. Segmentation targets finding specific segments of the market which are not otherwise tapped by larger firms.

Porter’s competitive strategies

Porter’s three strategies can be defined along two dimensions: strategic scope and strategic strength.

Avoiding the “Hole in the Middle”

Empirical research on the profit impact of marketing strategy indicates that firms with a high market share are often quite profitable, but so are many firms with low market share. The least profitable firms are those with moderate market share. This is sometimes referred to as the “hole-in-the-middle” problem. Porter explains that firms with high market share are successful because they pursue a cost-leadership strategy, and firms with low market share are successful because they employ market segmentation or differentiation to focus on a small but profitable market niche. Firms in the middle are less profitable because of the lack of a viable generic strategy.

12.3.3: SWOT Analysis

A SWOT analysis allows businesses to assess internal strengths and weaknesses in relation to external opportunities and threats.

Learning Objective

Explain how a SWOT analysis can be used as a tool in strategic decision making

Key Points

- SWOT analysis is a strategic planning method used to evaluate a business’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

- The goal of a SWOT analysis is to analyze the business environment to develop a strategic plan of action that captures opportunities using internal strengths (and avoids threats while addressing weaknesses).

- Businesses set objectives after the SWOT analysis has been performed, which allows the organization to define achievable goals.

Key Term

- environment

-

The surroundings of, and influences on, a particular item of interest.

A method of analyzing the environment in which businesses operate is referred to as a context analysis. One of the most recognized of these is the SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis. Performing a SWOT analysis allows a business to gain insights into its internal strengths and weaknesses and to relate these insights to the external opportunities and threats posed by the marketplace in which the business operates. The main goal of a context analysis, SWOT or otherwise, is to analyze the business environment in order to develop a strategic plan.

SWOT and Strategy

A SWOT analysis is a strategic planning method used to evaluate the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats related to a project or business venture. A SWOT assessment involves specifying the business’s objective and then identifying the internal and external factors that are favorable and unfavorable toward the business’s ability to achieve its objective. Setting the objective, in terms of moving from strategy planning to strategy implementation, should be done after the SWOT analysis has been performed. Doing so allows the organization to set achievable goals and objectives.

Components of SWOT

- Strengths: internal characteristics of the business that give it an advantage over competitors

- Weaknesses: internal characteristics that place the business at a disadvantage against competitors

- Opportunities: external chances to improve performance in the overall business environment

- Threats: external elements in the environment that could cause trouble for the business

SWOT analysis

The SWOT analysis matrix illustrates where the company’s strengths and weaknesses lie relative to factors in the market. Strengths and opportunities (the S and O of SWOT) are both helpful toward achieving company objectives, but strengths originate internally while opportunities originate externally. Similarly, weaknesses and threats (the W and T of SWOT) are harmful toward achieving objectives, but weaknesses originate internally and threats originate externally. Assessing all four points of the SWOT acronym ensures a thorough evaluation.

Identifying SWOTs is essential, as subsequent stages of planning can be derived from the analysis. Decision makers first determine whether an objective is attainable, given the SWOTs. If the objective is not attainable, a different objective must be selected, and then the process can be repeated. Users of SWOT analysis must ask and answer questions that generate meaningful information for each category to maximize the benefits of the evaluation and identify the organization’s competitive advantages.

12.3.4: Forecasting

Forecasting is the process of making statements about expected future events, based upon evidence, research, and experience.

Learning Objective

Demonstrate the value and role of effective forecasting in the development of successful strategies

Key Points

- An important aspect of forecasting is the relationship it holds with planning. Forecasting can be described as predicting what the future will look like, whereas planning predicts what the future should look like.

- As part of the implementation of policies and strategies, the forecasting method develops a reliable picture of the company’s expected future environment.

- Quantitative forecasting generally employs statistical confidence intervals and historical data to project potential future trends that are based upon the criteria being analyzed.

- Qualitative approaches are the opposite: they rely on logical premises, expertise, or past experience to generate estimates of future circumstances.

- Forecasting enables a manager to look at the current environment and identify likely scenarios, each of which may require a deviation from the overall strategy.

Key Terms

- scenario

-

An outline or model of an expected or supposed sequence of events.

- forecast

-

An estimation of a future condition.

- planning

-

The act of formulating a course of action or of drawing up plans.

Forecasting is the process of making statements about expected future events based upon evidence, research, and experience. For example, a business might estimate the exchange rate between the U.S. and the EU one year from now to determine the real financial cost of a project.

An important and often overlooked aspect of forecasting is the relationship it holds with planning. Forecasting can be described as predicting what the future will look like, whereas planning predicts what the future should look like. While both are managerial functions, forecasting is rife with external uncertainty while planning is hindered by internal uncertainty.

Forecasting Methods

Forecasting can be accomplished in a variety of different ways, some more statistically reliable than others. Following are a few critical points of differentiation and specific strategies to keep in mind when forecasting.

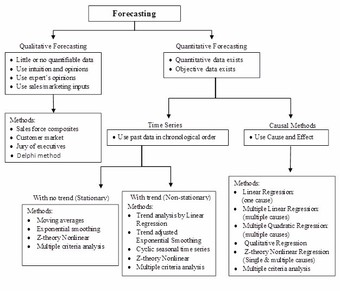

Quantitative vs. Qualitative

One of the simplest points of differentiation between methods is the reliance on numbers for accuracy. Quantitative forecasting generally uses statistical confidence intervals and historical data to project potential future trends that are based upon the criteria being analyzed. In this format, results are expressed in certainty intervals (i.e., how confident can we be that this will be the case?) and often rely on financial data (exchange rates, industry growth, etc.).

Qualitative approaches are the opposite; they rely on logical premises or past experience to generate estimates about future circumstances. The inherent problem with the qualitative approach is simple: subjectivity. While quantitative measure use data to express objective results, qualitative approaches do not have this luxury. Generally this type of forecast will include the opinions of experts, upper management, and market research.

Quantitative vs. qualitative forecasting

This flow chart compares quantitative and qualitative forecasting methods. Qualitative forecasting relies more on opinions than data and can employ market research, sales-force input, or a jury of executives. In contrast, quantitative forecasting relies more on objective, numerical data, and can look at chronological trends and statistical regression to infer cause-and-effect.

Causal Forecasting

Another method of forecasting, which is likely to be both quantitative and qualitative, is the causal/econometric approach. This strategy tasks managers with identifying cause and effect relationships of past instances by defining a series of if/then statements that express the likelihood of the outcome which follows. For example, if consumer spending is down in Q2, then it is likely that gross domestic product (GDP) growth will be down in Q3. Whether or not this is true would have to be supported with data, but the forecast is that Q2 consumer spending results could forecast Q3 GDP growth.

Implications of Forecasting

Keeping these methods in mind, it is important to understand how management uses these forecasts to draw conclusions. Forecasting plays a role in the implementation of policies and strategies. The practice helps businesses create plans for different situations, in addition to contingency plans for adapting if and when necessary.

Forecasting enables a manager to look at the current environment and identify likely scenarios, each of which may require a deviation from the overall strategy. As the management team implements the broader strategy, it must continuously monitor the current environment for deviations and use forecasting to adapt both the primary strategy and contingency plans for potential shifts.

To summarize, forecasts enable businesses to prepare new strategies or reinforce the existing strategy, based upon the projections made.

12.3.5: The Resource-Based View

In the resource-based view (RBV), strategic planning uses organizational resources to generate a viable strategy.

Learning Objective

Describe the intrinsic competitive advantage defined by the resource-based view strategy

Key Points

- Strategic approaches are wide and varied, and the resource-based view is a commonly cited strategic approach to attaining competitive advantage.

- To transform a short-run competitive advantage into a sustained competitive advantage requires that these resources be varied in nature and not perfectly mobile. They also must not be easily imitated or substituted without great effort.

- The RBV theory involves first identifying the firm’s potential key resources and deriving a strategy to apply them to create synergy.

- If key resources are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN), they may enable a strategy for achieving competitive advantage.

Key Terms

- heterogeneous

-

Diverse in kind or nature; composed of diverse parts.

- imitable

-

Capable of being copied.

- substitutable

-

Capable of being replaced.

The resource-based view (RBV) of strategy holds company assets as the primary input for overall strategic planning, emphasizing the way in which competitive advantage can be derived via rare resource combinations. To transform a short-run competitive advantage into a sustained competitive advantage requires that these resources are heterogeneous in nature and not perfectly mobile. Effectively, this principle translates into valuable resources that are cannot be either imitated or substituted without great effort. If the firm’s strategy emphasizes and accomplishes this goal, its resources can help it sustain above-average returns.

Applicability to Strategy

In many ways, business strategy aims to achieve competitive advantage through the proper use of organizational resources. As a result, the resource-based view offers some insight as to what defines strategic resources and furthermore what enables them to generate above-average returns (profit). Upper management must carefully consider what resources are at the company’s disposal and how these assets may equate to operational value through strategic processes.

The VRIN Characteristics

In achieving a competitive advantage, the resource-based view defines characteristics which make a competitive process sustainable. These characteristics are described as valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable, referred to as VRIN:

- Valuable – A resource must enable a firm to employ a value-creating strategy by either outperforming its competitors or reducing its own weaknesses. The value factor requires that the costs invested in the resource remain lower than the future rents demanded by the value-creating strategy.

- Rare – To be of value, a resource must be rare by definition. In a perfectly competitive strategic factor market for a resource, the price of the resource will reflect expected future above-average returns.

- Inimitable – If a valuable resource is controlled by only one firm, it can be a source of competitive advantage. This advantage can be sustained if competitors are not able to duplicate this strategic asset perfectly. Knowledge-based resources are “the essence of the resource-based perspective.”

- Non-substitutable – Even if a resource is rare, potentially value-creating and imperfectly imitable, of equal importance is a lack of substitutability. If competitors are able to counter the firm’s value-creating strategy with a substitute, prices are driven down to the point that the price equals the discounted future rents, resulting in zero economic profits.

A company should care for and protect resources that possess these characteristics, because doing so can improve organizational performance. The VRIN characteristics mentioned are individually necessary, but each is insufficient on its own to sustain competitive advantage. Within the framework of the RBV, the chain is as strong as its weakest link, and therefore requires the resource to display each of the four characteristics to be a viable strategy for competitive advantage.

Example of VRIN resources

Rare earth elements satisfy the requirements of being VRIN, in that they are valuable, rare, largely inimitable due to few extraction sites, and difficult to substitute.

12.4: Creating Strategy: Common Approaches

12.4.1: Strategic Management

Strategic management entails five steps: analysis, formation, goal setting, structure, and feedback.

Learning Objective

Identify the five general steps that allow businesses to develop a strategic process

Key Points

- Strategic management analyzes the major initiatives, involving resources and performance in external environments, that a company’s top management takes on behalf of owners.

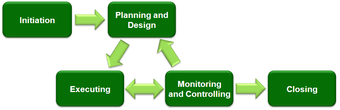

- The first three steps in the strategic management process are part of the strategy formulation phase. These include analysis, strategy formulation, and goal setting.

- The final two steps in strategic management constitute implementation. These steps include creating the structure (internal environment) and obtaining feedback from the process.

- By integrating these steps into the strategic management process, upper management can ensure resource allocation and processes align with broader organizational purpose and values.

Key Terms

- implementation

-

The process of moving an idea from concept to reality. In business, engineering, and other fields, implementation refers to the building process rather than the design process.

- objectives

-

The goals of an organization.

Strategic management analyzes the major initiatives, involving resources and performance in external environments, that a company’s top management takes on behalf of owners. It entails specifying the organization’s mission, vision, and objectives, as well as developing policies and plans which allocate resources to drive growth and profitability. Strategy, in short, is the overarching methodology behind the business operations.

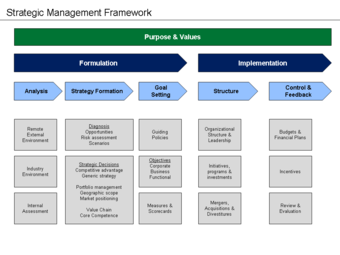

Strategic management framework

The above model is a summary of what is involved in each of the five steps of management: 1. analysis (internal and external), 2. strategy formation (diagnosis and decision-making), 3. goal setting (objectives and measurement), 4. structure (leadership and initiatives), and 5. control and feedback (budgets and incentives).

Five Steps of Strategic Management

As strategic management is a large, complex, and ever-evolving endeavor, it is useful to divide it into a series of concrete steps to illustrate the process of strategic management. While many management models pertaining to strategy derivation are in use, most general frameworks include five steps embedded in two general stages:

Formulation

- Analysis – Strategic analysis is a time-consuming process, involving comprehensive market research on the external and competitive environments as well as extensive internal assessments. The process involves conducting Porter’s Five Forces, SWOT, PESTEL, and value chain analyses and gathering experts in each industry relating to the strategy.

- Strategy Formation – Following the analysis phase, the organization selects a generic strategy (for example, low-cost, differentiation, etc.) based upon the value-chain implications for core competence and potential competitive advantage. Risk assessments and contingency plans are also developed based upon external forecasting. Brand positioning and image should be solidified.

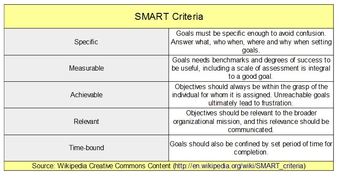

- Goal Setting – With the defined strategy in mind, management identifies and communicates goals and objectives that correlate to the predicted outcomes, strengths, and opportunities. These objectives include quantitative ways to measure the success or failure of the goals, along with corresponding organizational policy. Goal setting is the final phase before implementation begins.

Implementation

- Structure – The implementation phase begins with the strategy in place, and the business solidifies its organizational structure and leadership (making changes if necessary). Leaders allocate resources to specific projects and enact any necessary strategic partnerships.

- Feedback – During the final stage of strategy, all budgetary figures are submitted for evaluation. Financial ratios should be calculated and performance reviews delivered to relevant personnel and departments. This information will be used to restart the planning process, or reinforce the success of the previous strategy.

12.4.2: Combining Internal and External Analyses

Using combined external and internal analyses, companies are able to generate strategies in pursuit of competitive advantage.

Learning Objective

Apply a comprehensive understanding of internal and external analyses to the effective formation of new strategic initiatives

Key Points

- Organizations must carefully consider what internal assets are available that will differentiate them from the competition, within the same competitive environment.

- Similarly, organizations must understand the context in which they operate if they aspire to acquire competitive advantage over other incumbents.

- By understanding how internal and external factors relate, companies can piece together the ideal way in which their strengths can capture opportunities while offsetting threats and rectifying weaknesses.

- Implementing strategies that take into account both the internal and external environments will likely achieve competitive advantage and improve an organization’s ability to adapt. This is profit-generating strategic thinking.

Key Terms

- external

-

Concerned with the public affairs of a company or other organization.

- internal

-

Concerned with the non-public affairs of a company or other organization.

Organizations must carefully consider what internal assets will differentiate them from the competition, within the same competitive environment. This internal analysis requires careful consideration of the following models and factors:

- Core mission

- Overall strategy

- Porter’s competitive strategies

- SWOT analysis

- Forecasts

- Resource-based view

SWOT Analysis

Here is an example of the SWOT analysis matrix, which arranges strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

Similarly, organizations must understand the context in which they operate if they aspire to acquire competitive advantage over other incumbents. Models such as the following outline these concerns effectively:

- Porter’s five forces (and limitations)

- PESTEL and SCP

- Competitive dynamics

Merging Analyses for Competitive Advantage

These inputs generally outline each of the specific analyses a company should conduct to understand its internal and external environments. Combining these two constitutes context analysis, which is a method of analyzing the environment in which a business operates. Environmental scanning focuses mainly on the macro-environment of a business. Context analysis considers the entire environment of a business, both internal and external.

Using context analysis, alongside the necessary external and internal inputs, companies are able to generate strategies which actively capitalize on this knowledge in pursuit of competitive advantage. This strategic development requires companies to understand the opportunities and threats in the external environment and benchmark these against the strengths and weaknesses of their internal environment. By understanding how internal and external factors relate, companies can piece together the ideal way in which their strengths can capture opportunities while offsetting threats and rectifying weaknesses.

This melding of internal and external factors in pursuit of competitive advantage is an ongoing process, as the company must evolve and change in concert with the environment. As a result, strategic management is the process of constantly assessing both environments to ensure that the company retains a unique competitive position in which to generate value for stakeholders and customers. This implementation of strategies that take into account both the internal and external environments eventually achieves dynamic capabilities for the companies involved.

Change is costly, so firms must develop processes to find low pay-off changes. The ability to change depends on the ability to scan the environment, evaluate markets, and quickly accomplish reconfiguration and transformation ahead of the competition. These actions can be supported by decentralized structures, local autonomy, and strategic alliances.

12.4.3: Implementing Strategy

Strategic planning involves managing the implementation process, which translates plans into action.

Learning Objective

Define the necessary processes involved in executing and implementing a newly created strategy

Key Points