10.1: Decision Making in Management

10.1.1: Defining Decision Making

Decision making is the mental process of selecting a course of action from a set of alternatives.

Learning Objective

Identify the steps and analyze alternatives in a decision-making process

Key Points

- Decision making is a process of choosing between alternatives.

- Problem solving and decision making are distinct but related activities.

- Time pressure and personal emotions can affect the quality of decision-making outcomes.

Key Term

- Problem

-

A difficulty that has to be resolved or dealt with.

Decision making is the mental process of choosing from a set of alternatives. Every decision-making process produces an outcome that might be an action, a recommendation, or an opinion. Since doing nothing or remaining neutral is usually among the set of options one chooses from, selecting that course is also making a decision.

Difference Between Problem Analysis and Decision Making

While they are related, problem analysis and decision making are distinct activities. Decisions are commonly focused on a problem or challenge. Decision makers must gather and consider data before making a choice. Problem analysis involves framing the issue by defining its boundaries, establishing criteria with which to select from alternatives, and developing conclusions based on available information. Analyzing a problem may not result in a decision, although the results are an important ingredient in all decision making.

Steps in Decision Making

Decision making comprises a series of sequential activities that together structure the process and facilitate its conclusion. These steps are:

- Establishing objectives

- Classifying and prioritizing objectives

- Developing selection criteria

- Identifying alternatives

- Evaluating alternatives against the selection criteria

- Choosing the alternative that best satisfies the selection criteria

- Implementing the decision

Analysis of Alternatives

Many choices

Too many choices increase the difficulty of making a decision.

A major part of decision making involves the analysis of a defined set of alternatives against selection criteria. These criteria usually include costs and benefits, advantages and disadvantages, and alignment with preferences. For example, when choosing a place to establish a new business, the criteria might include rental costs, availability of skilled labor, access to transportation and means of distribution, and proximity to customers. Based on the relative importance of these factors, a business owner makes a decision that best meets the criteria.

The decision maker may face a problem when trying to evaluate alternatives in terms of their strengths and weaknesses. This can be especially challenging when there are many factors to consider. Time limits and personal emotions also play a role in the process of choosing between alternatives. Greater deliberation and information gathering often takes additional time, and decision makers often must choose before they feel fully prepared. In addition, the more that is at stake the more emotions are likely to come into play, and this can distort one’s judgment.

10.1.2: Decision-Making Styles

Decisions are driven by psychological, cognitive, and normative styles, each of which take into account varying influences on the final decision.

Learning Objective

Recognize the various factors which influence a leader’s decision-making style

Key Points

- The ability to make effective decisions that are rational, informed, and collaborative can greatly reduce opportunity costs while building a strong organizational focus.

- A psychological style to decision-making favors individual values, desires, and needs to determine the best course of action.

- A cognitive style to decision-making is heavily influenced by external factors and repercussions, such as how a given course of action will impact the broader environment in which the organization functions.

- Normative decision-making relies on logic and communicative rationality, aligning people based upon a logical progression from premises to conclusion.

- Regardless of the style or perspective, managers, and leaders must create organizational alignment in decision-making through building consensus.

Key Term

- communicative rationality

-

A theory or set of theories which describes human rationality as a necessary outcome of successful communication.

Why Decision-making Matters

Decision-making is a truly fascinating science, incorporating organizational behavior, psychology, sociology, neurology, strategy, management, philosophy, and logic. The ability to make effective decisions that are rational, informed, and collaborative can greatly reduce opportunity costs while building a strong organizational focus. As a prospective manager, effective decision-making is a central skill necessary for success. This requires the capacity to weigh various paths and determine the optimal trajectory of action.

Decision-making Styles

There are countless perspectives and tactics to effective decision-making. However, there are a few key points in decision-making theory that are central to understanding how different styles may impact organizational trajectories. Decision-making styles can be divided into three broad categories:

- Psychological: Decisions derived from the needs, desires, preferences, and/or values of the individual making the decision. This type of decision-making is centered on the individual deciding.

- Cognitive: This is an integrated feedback system between the individual/organization making a decision, and the broader environment’s reactions to those decisions. This type of decision-making process involves iterative cycles and constant assessment of the reactions and impacts of the decision.

- Normative: In many ways, decision making (particularly in groups, such as within an organization) is about communicative rationality. This is to say that decisions are derived based on the ability to communicate and share logic, using firms premises and conclusions to drive behavior.

Cognitive Theories

While the above styles give a general sense of the logic that drives choices, it is more useful to recognize that each of these three styles can play a role in any individual’s decision-making process. From the cognitive perspective, there are a few specific stylistic models that are useful to keep in mind:

Optimizing vs. Satisficing

Decision-making is limited to the finite amount of information an individual has access to. With limitations on information, true objectivity is impossible. Decisions are therefore intrinsically flawed. A satisficer will recognize this necessary imperfection, and prefer faster but less perfect decisions while a maximizer will take a longer time trying to find the optimal choice. This can be viewed as a spectrum, and each decision (depending on the risk of a mistake) can be viewed with varying levels of perfection.

Intuitive vs. Rational

Daniel Kahneman puts forward the idea of two separate minds that compete for influence within each of us. One way to describe this is a conscious and a subconscious perspective. The subconscious mind (referred to as System 1) is automatic and intuitive, rapidly consolidating data and producing a decision almost immediately. The conscious mind (referred to as System 2) requires more effort and input, utilizing logic and rationale to make an explicit choice.

Combinatorial vs. Positional

This relationship was put forward by Aron Katsenelinboigen based on how the game of chess is played, and an individual’s relationship with uncertainty. A combinatorial player has a final outcome, making a series of decisions that try to link the initial position with the final outcome in a firm, narrow, and concrete way (i.e. certainty). The positional decision-making approach is ‘looser’, with a sense of setting up for an uncertain future as opposed to pursuing a concrete object. Each move from this type of player would maximize options as opposed to pursue an outcome.

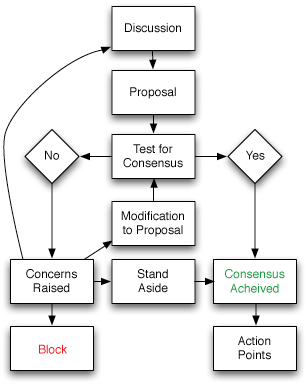

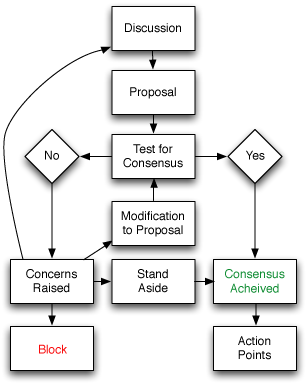

Consensus Flowchart

Regardless of perspective or style, all leaders must make decisions that create consensus. This model underlines how a manager or leader can discuss various options within a group setting, make proposals for action, and iterate until agreement is reached.

10.1.3: Types of Decisions

Three approaches to decision making are avoiding, problem solving and problem seeking.

Learning Objective

Differentiate between the three primary decision-making approaches: avoiding, problem solving, and problem seeking

Key Points

- One approach to decision making is to not make a choice—that is, to avoid making a decision altogether.

- Identifying and selecting a solution to a problem is a frequent type of decision outcome.

- Sometimes decision making results in the need to restate the purpose and subject of the choice; this is known as problem seeking.

Key Terms

- problem solving

-

Problem solving involves using generic or ad hoc methods, in an orderly manner, for finding solutions to specific problems.

- problem seeking

-

The process of clarifying, understanding, and restating the problem.

Every decision-making process reaches a conclusion, which can be a choice to act or not to act, a decision on what course of action to take and how, or even an opinion or recommendation. Sometimes decision making leads to redefining the issue or challenge. Accordingly, three decision-making processes are known as avoiding, problem solving, and problem seeking.

Avoiding

One decision-making option is to make no choice at all. There are several reasons why the decision maker might do this:

- There is insufficient information to make a reasoned choice between alternatives.

- The potential negative consequences of selecting any alternative outweigh the benefits of selecting one.

- No pressing need for a choice exists and the status quo can continue without harm.

- The person considering the alternatives does not have the authority to make a decision.

One example of avoiding a decision occurs routinely at the Supreme Court of the United States (as well as other appellate courts). The Supreme Court will decline to hear a case because, in their judgment, the issues have not been sufficiently considered in lower courts.

Problem Solving

Most decisions consists of problem-solving activities that end when a satisfactory solution is reached. In psychology, problem solving refers to the desire to reach a definite goal from a present condition. Problem solving requires problem definition, information analysis and evaluation, and alternative selection.

Problem Seeking

On occasion, the process of problem solving brings the focus or scope of the problem itself into question. It may be found to be poorly defined, of too large or small a scope, or missing a key dimension. Decision makers must then step back and reconsider the information and analysis they have brought to bear so far. We can regard this activity as problem seeking because decision makers must return to the starting point and respecify the issue or problem they want to address.

10.2: Rational and Nonrational Decision Making

10.2.1: Rational Decision Making

Rational decision making is a multi-step process, from problem identification through solution, for making logically sound decisions.

Learning Objective

Explain the characteristics of the rational decision-making process

Key Points

- Rational decision making favors objective data and a formal process of analysis over subjectivity and intuition.

- The model of rational decision making assumes that the decision maker has full or perfect information about alternatives; it also assumes they have the time, cognitive ability, and resources to evaluate each choice against the others.

- This model assumes that people will make choices that will maximize benefits for themselves and minimize any cost.

Key Terms

- perfect information

-

A situation in which all data that is relevant to a particular decision is known and available to the decision maker.

- Rational decision making

-

A logical, multi-step model for choosing between alternatives that follows an orderly path from problem identification through solution.

The Process of Rational Decision Making

Rational decision making is a multi-step process for making choices between alternatives. The process of rational decision making favors logic, objectivity, and analysis over subjectivity and insight. The word “rational” in this context does not mean sane or clear-headed as it does in the colloquial sense.

The approach follows a sequential and formal path of activities. This path includes:

- Formulating a goal(s)

- Identifying the criteria for making the decision

- Identifying alternatives

- Performing analysis

- Making a final decision.

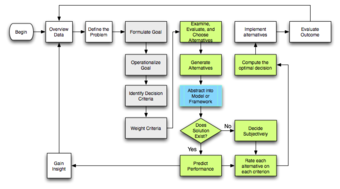

Rational-decision-making model

This flowchart illustrates the process of rational decision making.

Assumptions of the Rational Decision-Making Model

The rational model of decision making assumes that people will make choices that maximize benefits and minimize any costs. The idea of rational choice is easy to see in economic theory. For example, most people want to get the most useful products at the lowest price; because of this, they will judge the benefits of a certain object (for example, how useful is it or how attractive is it) compared to those of similar objects. They will then compare prices (or costs). In general, people will choose the object that provides the greatest reward at the lowest cost.

The rational model also assumes:

- An individual has full and perfect information on which to base a choice.

- Measurable criteria exist for which data can be collected and analyzed.

- An individual has the cognitive ability, time, and resources to evaluate each alternative against the others.

The rational-decision-making model does not consider factors that cannot be quantified, such as ethical concerns or the value of altruism. It leaves out consideration of personal feelings, loyalties, or sense of obligation. Its objectivity creates a bias toward the preference for facts, data and analysis over intuition or desires.

10.2.2: Problems with the Rational Decision-Making Model

Critics of the rational model argue that it makes unrealistic assumptions in order to simplify possible choices and predictions.

Learning Objective

Summarize the inherent flaws and arguments against the rational model of decision-making within a business context

Key Points

- Critics of the rational decision-making model say that the model makes unrealistic assumptions, particularly about the amount of information available and an individual’s ability to processes this information when making decisions.

- Bounded rationality is the idea that an individual’s ability to act rationally is constrained by the information they have, the cognitive limitations of their minds, and the finite amount of time and resources they have to make a decision.

- Because decision-makers lack the ability and resources to arrive at optimal solutions, they often seek a satisfactory solution rather than the optimal one.

Key Terms

- Rational choice theory

-

A framework for understanding and often formally modeling social and economic behavior.

- bounded rationality

-

The idea that decision-making is limited by the information available, the decision-maker’s cognitive limitations, and the finite amount of time available to make a decision.

- satisficer

-

One who seeks a satisfactory solution rather than an optimal one.

Critiques of the Rational Model

Critics of rational choice theory—or the rational model of decision-making—claim that this model makes unrealistic and over-simplified assumptions. Their objections to the rational model include:

- People rarely have full (or perfect) information. For example, the information might not be available, the person might not be able to access it, or it might take too much time or too many resources to acquire. More complex models rely on probability in order to describe outcomes rather than the assumption that a person will always know all outcomes.

- Individual rationality is limited by their ability to conduct analysis and think through competing alternatives. The more complex a decision, the greater the limits are to making completely rational choices.

- Rather than always seeking to optimize benefits while minimizing costs, people are often willing to choose an acceptable option rather than the optimal one. This is especially true when it is difficult to precisely measure and assess factors among the selection criteria.

Alternative Theories of Decision-Making

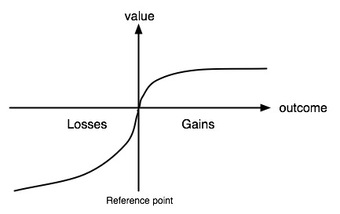

Prospect Theory

Alternative theories of how people make decisions include Amos Tversky’s and Daniel Kahneman’s prospect theory. Prospect theory reflects the empirical finding that, contrary to rational choice theory, people fear losses more than they value gains, so they weigh the probabilities of negative outcomes more heavily than their actual potential cost. For instance, Tversky’s and Kahneman’s studies suggest that people would rather accept a deal that offers a 50% probability of gaining $2 over one that has a 50% probability of losing $1.

Bounded Rationality

Other researchers in the field of behavioral economics have also tried to explain why human behavior often goes against pure economic rationality. The theory of bounded rationality holds that an individual’s rationality is limited by the information they have, the cognitive limitations of their minds, and the finite amount of time they have to make a decision. This theory was proposed by Herbert A. Simon as a more holistic way of understanding decision-making. Bounded rationality shares the view that decision-making is a fully rational process; however, it adds the condition that people act on the basis of limited information. Because decision-makers lack the ability and resources to arrive at the optimal solution, they instead apply their rationality to a set of choices that have already been narrowed down by the absence of complete information and resources.

10.2.3: Non-Rational Decision Making

People frequently employ alternative, non-rational techniques in their decision making processes.

Learning Objective

Examine alternative perspectives on decision making, such as that of Herbert Simon and Gerd Gigerenzer, which outline non-rational decision-making factors

Key Points

- The rationality of individuals is limited by the information they have, the cognitive limitations of their minds, and the finite amount of time they have to make a decision.

- Simon defined two cognitive styles: maximizers and satisficers. Maximizers try to make an optimal decision, whereas satisficers simply try to find a solution that is “good enough” for the situation.

- Some research has shown that simple heuristics frequently lead to better decisions than the theoretically optimal procedure.

- Emotion appears to aid the decision-making process; decisions often occur in the face of uncertainty about whether one’s choices will lead to benefit or harm.

- Robust Decision Making (RDM) is a particular set of methods and tools that is designed to support decision making under conditions of uncertainty.

Key Terms

- cognitive

-

The part of mental functions that deals with logic, as opposed to affective functions, which deal with emotion.

- rational

-

Logically sound; not contradictory or otherwise absurd.

- heuristic

-

An experience-based technique for problem solving, learning, and discovery; examples include using a rule of thumb, an educated guess, an intuitive judgment, or common sense.

The rational model of decision making holds that people have complete information and can objectively evaluate alternatives to select the optimal choice. The rationality of individuals is limited, however, by the information they have, the cognitive limitations of their minds, and the finite amount of time they have to make a decision. To account for these limitations, alternative models of decision making offer different views of how people make choices.

Herbert A. Simon

American psychology and economics researcher Herbert A. Simon defined two cognitive styles: maximizers and satisficers. Maximizers try to make an optimal decision, whereas satisficers simply try to find a solution that is “good enough.” Maximizers tend to take longer making decisions due to the need to maximize performance across all variables and make trade-offs carefully. They also tend to regret their decisions more often (perhaps because they are more able than satisficers to recognize when a decision has turned out to be sub-optimal). On the other hand, satisficers recognize that decision makers lack the ability and resources to arrive at an optimal solution. They instead apply their rationality only after they greatly simplify the choices available. Thus, a satisficer seeks a satisfactory solution rather than an optimal one.

Gerd Gigerenzer

German psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer goes beyond Simon in dismissing the importance of optimization in decision making. He argues that simple heuristics—experience-based techniques for problem-solving—can lead to better decision outcomes than more thorough, theoretically optimal processes that consider vast amounts of information. Where an exhaustive search is impractical, heuristic methods are used to speed up the process of finding a satisfactory solution.

The Role of Emotion

Emotion is a factor that is typically left out of the rational model; however, it has been shown to have an influential role in the decision-making process. Because decisions often involve uncertainty, individual tolerance for risk becomes a factor. Thus, fear of a negative outcome might prohibit a choice whose benefits far outweigh the chances of something going wrong.

Robust Decision Making

The Brain’s Heuristics for Emotions

Emotions appear to aid the decision-making process.

Robust decision making (RDM) is a particular set of methods and tools developed over the last decade—primarily by researchers associated with the RAND Corporation—that is designed to support decision making and policy analysis under conditions of deep uncertainty. RDM focuses on helping decision makers identify and develop alternatives through an iterative process. This process takes into account new information and considers multiple scenarios of how the future will evolve.

10.3: Conditions for Making Decisions

10.3.1: Evidence-Based Decision Making

The practice of evidence-based decision making involves using current information to make empirically supported decisions.

Learning Objective

Describe the concept and strategic implications of evidence-based decision making in management (EBMgt)

Key Points

- Evidence-based protocols have been adopted in fields such as business, education, and law enforcement, demonstrating the usefulness of this approach.

- Evidence-based decision making in management (EBMgt) requires that managers and their organizations procure and organize enough empirical and objective data to implement a scientific decision-making process.

- Critics argue that evidence-based approaches do not take ethics into consideration. As a result, managers must take an active role in implementation.

- Overall, EBMgt is a useful tool for managers to generate informed and intelligent perspectives, decisions, and strategies as they lead a company.

Key Term

- EBMgt

-

A management practice that emphasizes a rational, objective, and empirical approach to addressing business issues.

Defining Evidence-Based Decision Making

Evidence-based management entails making decisions and creating organizational practices that are informed by analyzing the best available data. The practice of evidence-based decision making in management (often abbreviated as EBMgt) evolved from medicine and emphasizes a rational, objective, and empirical approach to addressing business issues. It is analogous to the scientific method which uses experiments and data collection to advance knowledge.

Scientific theories

Scientific theories are the result of analysis applied to data, records, insights, and experiments. Evidence is gathered, is analyzed, and from there a theory is developed.

The EBMgt Collaborative—sponsored by a number of universities and foundations throughout the U.S., U.K., and Canada—is an organization devoted to expanding the practice of EBMgt. The EBMgt Collaborative’s mission statement includes a comprehensive definition of the practice:

Evidence-Based Management (EBMgt) enhances the overall

quality

of organizational decisions and practices through deliberative use of relevant and best available scientific evidence. EBMgt combines conscientious, judicious use of best evidence with individual expertise; ethics; valid, reliable business and organizational facts; and consideration of

impact

on

stakeholders

.

Pros and Cons of EBMgt

Evidence-based protocols have been adopted in non-scientific fields such as business, education, and law enforcement, demonstrating usefulness of this approach. Because the evidence approach examines outcomes, it supports the careful consideration of the relationship between cause and effect. Managers can have more confidence in their choices when they can point to data that supports the likelihood of that choice leading to desired results.

The adoption of EBMgt also creates advantages in how an organization operates. The formal processes of EBMgt require managers and other decision makers to be disciplined and organized in their decision-making process. The degree of structure in collecting and analyzing data helps create a working environment that favors facts over intuition or guess-work.

Critics of EBMgt argue that evidence may not always be complete or appropriately measured; they also argue that analysis is not always neutral or without bias. It is not always possible to agree on what counts as credible evidence; even if data on a certain factor is desirable, it may not exist or be readily available. The idea of objectivity is obscured because data is subject to interpretation, and those with different levels of experience or backgrounds can reach different conclusions about the implication of a given set of findings. Critics also argue that evidence-based approaches do not take ethics into consideration.

Though it has its limitations, EBMgt can be an effective approach to informing the decisions of managers. By acquiring sufficient data that support conclusions, EBMgt can help decision makers distinguish between alternatives and choose the most promising option. It can also help influence others to support a decision once it has been made.

10.3.2: The Value of Analytics in Decision Making

Analytics help decision makers determine risk, weigh outcomes, and quantify costs and benefits associated with decisions.

Learning Objective

Recognize the decision-making value of utilizing statistics and analytics to create accurate predictions

Key Points

- Predictive and descriptive analytics are two methods of using data to inform and evaluate alternatives during decision making. They can also be used to explain performance outcomes.

- Predictive analytics encompass a variety of statistical techniques (such as modeling, machine learning, and data mining) that analyze current and historical facts to make predictions about future events.

- Descriptive analytics focus on developing new insights and understanding of business performance based on data and statistical methods; these analytics are then used to make strategic decisions for the company.

Key Term

- analytics

-

The use of skills, technologies, and practices to explore and investigate past performance, gain insight, and drive business decision making.

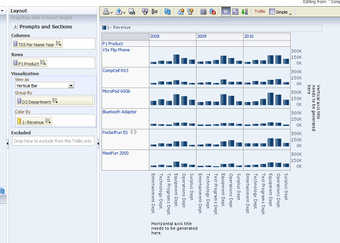

Analytics refer to the use of skills, technologies, and practices to explore and investigate past performance, gain insight, and drive business decision making. Predictive and descriptive analytics are two methods of using data and statistical methods to assess actual outcomes against target standards and goals. These types of analysis can explain the relationship between factors that influence outcomes; they can also help prioritize improvement and other planning efforts. Companies can use their analytic capabilities to create advantages over competitors and better perform in the marketplace.

Analytical Tools

Quantitative metrics and analysis can help decision makers make more accurate decisions and better predict risks associated with decisions.

Predictive Analytics and Decision Making

Predictive analytics encompass a variety of statistical techniques (such as modeling, machine learning, and data mining) that analyze current and historical facts to make estimates about future events. Models capture relationships among many factors, allowing an assessment of risk or potential associated with a particular set of conditions. This helps to guide decision making for candidate transactions. Data mining draws on large numbers of records to identify patterns that can then be identified as opportunities or risks. For example, by analyzing grades for an entire class of first-year students, academic advisers can predict which students are most likely to struggle in the class.

Predictive analytics help decision makers to predict the outcome(s) of a decision before it is implemented. Using these probabilities, decision makers can calculate the expected value of alternatives once risks and benefits are taken into account. Predictive analytics are particularly useful when there is a high degree of uncertainty. By carefully considering what is not known, decision makers can build confidence in the estimates that inform their choices. Forecasting consumer behavior in response to a new product or marketing initiative are examples of the use of predictive analytics.

Descriptive Analytics and Decision Making

Descriptive analytics answer the questions, “What happened and why did it happen?” This approach seeks to understand past performances by using historical data to analyze the reasons behind past success or failure. Understanding cause and effect can help refine business and operational strategies. Most management reporting—such as sales, marketing, operations, and finance—uses this type of analysis. Descriptive analytics are used in quality management techniques and other methods of statistical process control.

Analytics in the Modern Business World

Descriptive and predictive analytics have increased greatly in popularity due to advances in computing technology, techniques for data analysis, and mathematical modeling. Desktop tools can easily create reports and summaries of analytic results that help decision makers readily understand the findings and their implications. These tools create tables, charts, and graphs to present the data visually, which can help to clearly communicate the meaning of the data.

10.3.3: Making Decisions Under Conditions of Risk and Uncertainty

Conditions of risk and uncertainty frame most decisions rendered by management.

Learning Objective

Outline the various risks that influence the decision-making process

Key Points

- Uncertainty and risk are not the same thing. Whereas uncertainty deals with possible outcomes that are unknown, risk is a certain type of uncertainty that involves the real possibility of loss. Risks can be more comprehensively accounted for than uncertainty.

- Decision-making under conditions of risk should seek to identify, quantify, and absorb risk whenever possible.

- The quantity of risk is equal to the sum of the probabilities of a risky outcome (or various outcomes) multiplied by the anticipated loss as a result of the outcome.

- A firm’s ability to absorb, transfer, and manage risk will often define management’s risk appetite; once risks are identified and quantified, decisions may be made as to what extent risky outcomes may be tolerated.

Key Terms

- hedge

-

A contract or arrangement reducing one’s exposure to risk.

- force majeure

-

An unavoidable catastrophe, especially one that prevents someone from fulfilling a legal obligation; an unforeseeable act of nature.

Uncertainty is a state of having limited knowledge of current conditions or future outcomes. It is a major component of risk, which involves the likelihood and scale of negative consequences. Managers often deal with uncertainty in their work; to minimize the risk that their decisions will lead to undesired outcomes, they must develop the skills and judgment necessary for reducing this uncertainty. Managing uncertainty and risk also involves mitigating or even removing things that inhibit effective decision-making or adversely effect performance.

One cause of uncertainty is proximity: things that are about to happen are easier to estimate than those further out in the future. One approach to dealing with uncertainty is to put off decisions until data become more accessible and reliable. Of course, delaying some decisions can bring its own set of risks, especially when the potential negative consequences of waiting are great.

Identifying Risks

Managing uncertainty in decision-making relies on identifying, quantifying, and analyzing the factors that can affect outcomes. This enables managers to identify likely risks and their potential impact. Types of risk include:

- Strategic risks: These are risks that arise from the investments an organization makes to pursue its mission and objectives. They are often associated with competition and can include macroeconomic risks (the alignment of buyers and sellers consistent with the principles of supply and demand), transaction risks (the operational risks from merger and acquisition activity, divestitures, or partnerships), and investor relations risk (the risks associated with communicating effectively or ineffectively with the investment community).

- Financial risks: These relate to potential economic losses that can result from poor allocation of resources, changes in interest rates, shifts in tax policy, increases or decreases in the price of commodities, or fluctuations in the value of currency.

- Operational risks: These risks can arise due to choices about design and use of processes to create and deliver goods and services. They can include production errors, substandard raw materials, and technology malfunctions.

- Legal risks: These risks stem from the threat of litigation or ambiguity in applicable laws and regulations (including whether they are likely to change); these threats create uncertainty in the steps an organization should take to address its obligations to customers, employees, suppliers, stockholders, communities, and governments.

- Other risks: Risks are very commonly associated with force majeure, or events beyond the control of the organization. These can include weather disasters, floods, earthquakes, and war or other hostilities.

Quantifying Risks

Once management has identified the appropriate risk category that may impact a certain decision, it may go about quantifying these risks. In other words, management will ascertain the costs incurred if a risky outcome were to happen. This can be mathematically daunting for many types of risk, especially financial risk. Generally speaking, however, risk is equal to the sum of the probabilities of a risky outcome (or various outcomes) multiplied by the anticipated loss as a result of the outcome. This is similar to performing a sensitivity analysis if the universe of outcomes is known.

Managing Risks

The ability of a firm to absorb, transfer, and manage risk is critical in management’s decision-making process when risky outcomes are involved. This will often define management’s risk appetite and help to determine, once risks are identified and quantified, whether risky outcomes may be tolerated. For example, many financial risks can be absorbed or transferred through the use of a hedge, while legal risks might be mitigated through unique contract language. If managers believe that the firm is suited to absorb potential losses in the event the negative outcome occurs, they will have a larger appetite for risk given their capabilities to manage it.

The Deepwater Horizon Oil Rig on Fire.jpg

The Deepwater Horizon oil rig fire is an example of a risk faced by a management team.

10.4: Decision Making Process

10.4.1: Identify and Define the Problem

Identifying, defining, and understanding a problem is essential to analyzing and choosing between alternatives.

Learning Objective

Express the importance of properly framing and defining the problem prior to pursuing a decision

Key Points

- Decision makers must first make sure that they completely understand the problem.

- It is a good idea to be able to look at a decision from multiple perspectives. This can be accomplished through selecting a group of people who will look at and define the problem from different perspectives.

- Data should be gathered on how the current problem is affecting people now. Some examples of important data to gather include efficiency levels, satisfaction levels, and output metrics.

Key Term

- Output metrics

-

Standards or data points that showm the rate and speed of production over a certain period of time.

Decision making is a central responsibility of managers and leaders. It requires defining the issue or the problem and identifying the factors related to it. Doing so helps create a clear understanding of what needs to be decided and can influence the choice between alternatives.

An important aspect of any decision is its purpose, or objective. This is different from identifying a specific decision outcome; rather, it has to do with the motivation to make the decision in the first place. For instance, customer complaints can imply the need to change aspects of how service is delivered, so decisions must be made to address them. Factors that are not related to service delivery would not be in consideration in that decision.

There are a number of ways to define a problem, such as creating a team to tackle it and gathering relevant data by interviewing employees and customers.

Developing a Group to Define the Problem

It is a good idea to be able to approach decision definition from different perspectives. Doing so can capture dimensions of the issue that might otherwise have been overlooked. Involving two or more people can bring different information, knowledge, and experience to a decision. This can be accomplished through forming a group to consider and define the problem or issue, and then to frame the decision based on their collective ideas. Having a shared definition and understanding of a decision helps the decision-making process by creating focus for discussions and making them more efficient.

Gathering Data to Define the Decision

Most decisions require a good understanding of the current state in order to understand all implications of the potential choices. For this reason it can be valuable to consider the views of all parties that will be affected by the decision. These may include customers, employees, or suppliers. Data should be gathered on how the current problem is affecting people now. Some examples of important data to gather include efficiency levels, satisfaction levels, and output metrics. Interviews, focus groups, or other qualitative methods of data collection can be used to identify existing conditions that may be connected to the decision in question. As much information as possible should be gathered to build confidence that a decision has been accurately and appropriately formulated before additional analysis and assessment of alternatives begin.

10.4.2: Generate Alternatives

Identifying a range of potential choices is essential to any decision-making process.

Learning Objective

Discuss methods for identifying alternatives and why doing so is an important part of decision making.

Key Points

- Decision makers should identify the many alternative choices they face before beginning to conduct analysis for a decision.

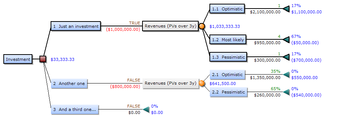

- A decision tree is a decision support tool that uses a tree-like graph or model of decisions and their possible consequences, including chance event outcomes and resource costs. A decision tree can help lay out the alternatives and determine the best ones to consider.

- When dealing with information in decision analysis, there are often biases and errors in judgment, such as the fact that people pay more attention to information that is easily available.

- It is important for a decision maker to receive plenty of input from others to avoid any bias.

Key Terms

- bias

-

An inclination towards something; predisposition, partiality, prejudice, preference, predilection.

- decision tree

-

A visualization of a complex decision-making situation in which the possible decisions and their likely outcomes are organized in the form of a graph that resembles a tree.

Once a decision has been defined, the next step is to identify the alternatives for decision makers to select from. It is rare for there to be only one alternative; in fact, a goal should be to identify as many different alternatives as possible without making too narrow a distinction between them. The decision maker can then narrow the list based on analysis, resource limitations, or time constraints. Often, doing nothing is an alternative worthy of consideration.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a good technique for identifying alternatives. Making lists of possible combinations of actions can generate ideas that can be shaped into alternatives. Often this is best done with a small group of people with different perspectives, knowledge, and experience. A formal approach to capturing the results of brainstorming can help make sure options are not overlooked.

Another way to evaluate alternatives is through a decision tree.

Decision Trees

A decision tree is a decision support tool that uses a structured graphical depiction of alternatives. This method creates a visual depiction of choices so decision makers can have a clearer understanding of them. Decision trees help divide larger decisions into smaller ones and are useful for uncovering all available options.

Decision trees have a starting point and then branch out, with each branch representing a different event, action, or outcome. Resource costs, benefits, and probabilities can be recorded by each option.

Applied decision tree

Decision trees can improve investment decisions by optimizing them for maximum payoff.

Decision trees have three types of nodes at each part of the diagram:

- Decision nodes: these are the alternatives themselves and represent the point where a decision must be made.

- Change nodes: these are points where choices must be made; in their simplest form these may be represented by Yes/No or Go/No Go options.

- Conclusion or end nodes: these are the points that appear when there are no more alternatives or choices to be made, and they state the outcome of a particular decision branch.

When generating alternatives, decision makers use information gathered by defining the problem. The list of alternatives can then only be as good, complete, and accurate as the quality of that data. Overlooking factors or dimensions of an issue or problem can mean missing viable alternatives. The alternatives identified become the basis for subsequent analysis and ultimately the decision itself.

10.4.3: Evaluate Alternatives

In order to eliminate bias in a decision, one can use tools such as influence diagrams and decision trees to evaluate alternatives.

Learning Objective

Model potential decision alternatives through utilizing pro/con analysis, influence diagrams, decision trees and Bayesian networks

Key Points

- There are a few tools available to decision makers that can be used to help quantify the potential alternatives to and outcomes of a decision. These tools include a simple pro-and-con analysis, an influence diagram, and a decision tree.

- A decision tree is used to lay out the alternatives and then assign a utility, or a relative value of importance, to a particular alternative.

- Another tool that decision makers can use to quantify a decision is an influence diagram, which is a compact graphical and mathematical representation of a decision situation.

Key Terms

- Bayesian network

-

A probabilistic model that represents a set of random variables and their conditional dependencies (e.g., a Bayesian network could calculate the probabilities between symptoms and a disease).

- decision tree

-

A visualization of a complex decision-making situation in which the possible decisions and their likely outcomes are organized in the form of a graph that resembles a tree.

When a decision maker has successfully and accurately defined the problem and generated alternatives, he or she can then conduct analysis useful to evaluating and assessing each. This typically involves analysis of quantitative data such as costs or revenues. Qualitative data is also used to be sure that considerations such as consistency with strategy, effects on relationships, or ethical implications are taken into account.

A first step in analysis is identifying all the sources of data needed to understand the various alternatives and their potential outcomes. Finding this data often involves research if relevant data do not exist. The results of data analysis are typically gathered, summarized, and synthesized as the basis for discussions and deliberations by decision makers.

There are a few approaches that can be used to help structure the analysis and assessment of potential decision alternatives. These range from simple tools such as lists of pros and cons to more complex models such as decision trees and influence diagrams, which can capture more variables and include more data.

A decision tree specifies alternatives visually and creates paths of subdecisions to be made or uncertainties to be considered in order to estimate the outcome of a given choice. It includes a value for each alternative, such as a financial outcome, and notes the probabilities that each outcome will occur. Decision trees sometime include the results of financial analysis such as net present value, which determines the present or current value of a stream of incoming cash flows that a project will bring in sometime in the future. One limitation to using decision trees is that they can become highly complicated as decisions become more complex or outcomes involve greater numbers of variables.

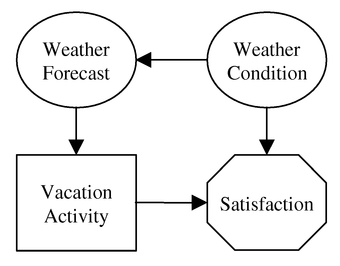

Another tool that decision makers can use to analyze alternatives is an influence diagram. An influence diagram is a compact graphical and mathematical representation of a decision situation. It groups sets of variables into things that are known and factors that are uncertain and links them to the choice to be made and the criteria for assessing it. Influence diagrams are directly applicable in group decisions because they allow incomplete sharing of information among team members to be modeled and for estimates to be made explicitly.

Influence diagram example

This is a simple example of an influence diagram used to evaluate the alternatives of a decision.

In the scenario depicted by the influence diagram above, a person is choosing between vacation alternatives. Her goal is a satisfactory vacation, which will be influenced by how good the weather is. She cannot have direct knowledge at the time of the decision what the weather will be, but she can gather information on the weather forecast or other climate patterns to help her make the choice of vacation location.

10.4.4: Determine a Course

A good decision maker will always try to eliminate personal biases and understand his personal risk tolerance when determining a course.

Learning Objective

Evaluate the importance of bias and prospect theory in effectively ensuring decision makers arrive at the ideal option

Key Points

- Decision makers should use clear selection criteria to evaluate and choose among alternatives.

- Bias is inherent in making decisions, but decision makers should do their best to identify emotional and other personal factors that may affect their judgment and adjust their deliberations to take biases into account.

- Prospect theory identifies aversion to loss as a common bias that can cause people to overstate the downside of alternatives.

Key Term

- bias

-

The human tendency to make systematic decisions in certain circumstances based on cognitive factors rather than evidence; an inclination or prejudice toward something.

Once decision alternatives have been identified and analyzed, the decision maker is ready to make a choice. To do so it is important to have a set of criteria against which to evaluate and even rank the alternatives. Selection criteria might include total cost, time to implement, risk, and the organization’s ability to successfully implement the decision. Categorizing criteria in terms of importance helps to differentiate between options that might have similar disadvantages but different advantages, or vice versa. For example, consider two alternatives that are equally risky, but one will cost more and the other will take longer to implement. In this case, the decision would depend on whether cost or time is more important. On occasion, decision makers may believe they do not have sufficient information about a particular alternative, so additional analysis may be needed.

Decision makers should do their best to minimize their biases, or preconceived ideas about which alternative is preferable, until they complete the analysis. The benefit of using data to support decisions is that when analysis is done correctly it is objective and factual, not based on emotions or subjective preferences. While it is natural to have biases based on experience or feelings, it is important for managers and leaders to recognize them and take steps to keep them from butting their judgment. People may be unable to eliminate all of their biases, especially when it comes to their tolerance for risk. It is therefore important to be explicit about assumptions and biases to the extent possible, so that people involved in making the decision are aware of them and can adjust their deliberations accordingly.

Bias and Prospect Theory

One of the best-known theories about bias in decision making is Kahneman and Tversky’s prospect theory. Prospect theory is based on the notion that people think about decisions in terms of potential gains and losses and tend to be more averse to losses than they are favorable to gains. This means that decision makers may overstate the downside of an alternative, since they have a greater fear of negative consequences. As a result, people are biased toward less risky decisions, even when the benefits of a different alternative would outweigh the risks of the chosen one. Prospect theory also suggests that people consider how others would benefit or be hurt by the outcome of their decision. This contradicts traditional economic theory, which states that individuals make decisions based only on their own well-being.

Prospect theory and risk aversion

This graph represents Kahneman and Tversky’s theory. The distance between the x-axis and the curve is smaller in the positive direction (i.e., for positive outcomes, or gains) than it is in the negative direction (i.e., for negative outcomes, or losses). This means that people’s positive value of gains is less than people’s negative value of losses. In other words, people are more sensitive to possible risk than to possible gain.

10.4.5: Implement the Course

Implementing a decision requires the decision maker to make and execute a plan of action.

Learning Objective

Describe the three central steps to effectively implementing a decision upon the selection of a particular perspective or course

Key Points

- Three essential actions to implementing a decision include creating an implementation plan, informing stakeholders, and executing the plan.

- It is common to adjust a plan once the work of implementing a decision begins. Throughout the implementation of the decision, there may be situations and issues that the decision maker did not consider initially.

- During the implementation phase, decision makers should be aware that they may be persuaded by pressures from stakeholders and employees to change the decision that they have made or to reconsider their decision.

Key Term

- stakeholder

-

A person or group that affects or can be affected by an organization’s actions.

After all of the alternatives have been analyzed and one has been selected, it is time to implement the decision. Three essential actions to implementing a decision are: developing a plan, communicating with stakeholders, and executing the plan (which includes assessing outcomes and making adjustments as needed).

Developing a Plan

A decision is reached with a certain objective in mind. Once it is made, managers identify the steps needed to reach that objective. These can include listing necessary actions and activities, considering required financial and other resources, and making a schedule for completing the work. The more thought that goes into developing a plan, the less likely it is that important factors will be overlooked.

Communicating with Stakeholders

An implementation plan requires the involvement of different people, and the consequences of decisions affect various stakeholders. For these reasons it is important to have a plan for communicating important information related to the decision and its implementation. This usually involves talking with employees, but may also mean letting customers or suppliers know about the decision and any effects it may have on them.

Executing the Plan

Accomplishing the decision’s objective requires completing the steps outlined in the implementation plan. Once this work is underway, managers assess progress and may identify areas for improvement. Circumstances can change or new issues might arise that had not been thought of during the planning process. These may require additions to, or other changes in, the plan. Because most decisions are made under conditions of uncertainty, as time passes what was once unknown can become known. Where estimates were incorrect or the unexpected happens, adjustments need to be made to the implementation plans. If the new facts are significant enough, it can even require reconsideration of the decision.

During the implementation phase, decision makers should be aware that they may be persuaded by pressures from stakeholders and employees to change their decision, or to reconsider. A few of these pressures include coercive pressures and normative pressures. Coercive pressures come from the social sanctions that can be applied if one does not act in socially legitimate ways. Normative pressures arise from broad social values, and they concern what people think they should do. Both coercive and normative pressures will likely be felt by the decision maker during the implementation of the decision, especially if the decision is an unpopular one. However, the decision maker should fall back on the analyses that originally brought them to the decision and strive not to be swayed by these pressures.

10.4.6: Evaluate the Results

Decision makers must evaluate the results of a decision to improve the processes and outcomes of future decisions.

Learning Objective

Recognize the appraisal stage and the development of future insights as the final stage in the decision-making process

Key Points

- Evaluation is the final step of the formal decision process. Evaluating outcomes may help the decision maker learn lessons that will improve her decision-making abilities.

- Self-esteem is an important factor in evaluating results because it may lead to decision makers viewing the results of their decision with favorable bias. This can cause people to filter out or discount information that might show the decision in an unfavorable light.

- It can also be valuable to assess the process by which a decision was made to make future decisions more effective.

Key Terms

- appraisal

-

A judgment or assessment—especially a formal one—of the value of something.

- insight

-

An extended understanding of a subject resulting from identification of relationships and behaviors within a model, context, or scenario.

After a decision has been made and implemented it is important to assess both the outcome of the decision and the process by which the decision was reached. Doing so confirms whether the decision actually led to the desired outcomes and also provides important information that can benefit future decision making. Learning from experience is important to continuous improvement and effectiveness.

Evaluating Outcomes

The objective of evaluating outcomes is for the decision maker to develop insight into the decision. Many of the lessons developed in this stage come out of examining the implications of the decision. Insight can be obtained by referencing key business metrics such as increased revenue, lowered costs, larger market share, or greater consumer awareness. One can also consider whether a decision had the desired effect. For example, a decision to hold additional training seminars may have been intended to make it more convenient for people to learn a new technology. However, if overall attendance did not increase, then the decision may not have addressed the underlying cause of why people did not go to training events. Once the outcome of a decision is known, the results may imply a need to revise the decision and try again.

When decision outcomes are not clearly measurable or have ambiguous results—some parts good, some bad—is not uncommon for people to emphasize the favorable data and discount the negative. Maintaining self-esteem also may cause decision makers to attribute good outcomes to their actions and bad outcomes to factors outside their control. This type of bias can limit an honest assessment of what went right and what didn’t, and thus reduce what can be learned by carefully evaluating outcomes.

Appraising the Decision Process

It can also be valuable for decision makers to step back and examine the process by which a decision was made. Often they can learn lessons that will benefit future decisions. If the decision was made by a group, having a conversation with all participants is often worthwhile. Whether enough information was gathered and whether its quality was high enough are two questions that should be considered. How the decision maker dealt with uncertainty or bias can be examined in the face of the results that have transpired. If estimates were off, or it becomes clear that emotions played too large a role in making a choice, it is important to learn from those mistakes so they won’t happen again. Finally, it is important to question whether all the relevant parties contributed information and knowledge needed for the decision, and whether everyone who should have been involved was given the chance to participate.

10.5: Considering Ethics in Decision Making

10.5.1: Moral Principles in Management

Business ethics deals with the beliefs and principles that guide management decisions.

Learning Objective

Recognize the importance of ethics in the business environment, particularly how individual managers should employ these principles

Key Points

- Business ethics concerns the duties and obligations an organization has to its stakeholders, including employees, customers, suppliers, and communities.

- The corporate world has taken steps to improve ethical compliance in the workplace after major corporate scandals like WorldCom, Tyco, and Enron.

- While compliance with laws is coerced trough the threat of sanctions or litigation, ethical behavior is voluntary.

- It is the duty of all managers to see that their organization maintains ethical practices and behaviors.

Key Terms

- ethics

-

The study of principles relating to right and wrong conduct.

- moral

-

Of or relating to principles of right and wrong in behavior, especially for teaching right behavior.

Morality (from the Latin moralitas, meaning “manner, character, proper behavior”) is the differentiation of intentions, decisions, and actions between those that are good (or right) and those that are bad (or wrong). Ethics, also known as moral philosophy, is a branch of philosophy that involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong conduct.

Business Ethics

Business ethics (also corporate or professional ethics) is a form of applied ethics that examines the principles and moral beliefs that guide management decisions. Ethical issues include the obligations a company has to its employees, suppliers, customers and neighbors. In particular, business ethics is concerned with situations when those obligations are inconsistent with economic or strategic choices, or are in conflict with each other. Legal obligations are not the same as ethical ones; laws are enforced through the threat or imposition of punishment by a government or through civil litigation. All individuals and organizations must follow the law, but complying with ethical beliefs is voluntary, not coerced.

Business ethics applies to all aspects of business conduct by individuals and organizations as a whole. Ethical behavior is conduct that follows one’s personal beliefs or shared organizational or institutional values. When individuals take action on behalf of an organization, they represent its ethics to society. Businesses are dependent on their reputations, so it is important for them to have clear and consistent expectations regarding ethical standards to guide employee behavior. Many employees prefer to work for organizations that share their own moral beliefs. A company’s ethical practices can thus have an effect on the recruitment and retention of employees.

In recent decades there has been widespread attention to business ethics due to highly visible cases of corporate malfeasance, such as the WorldCom, Enron, and Tyco scandals. To protect their reputations, companies have begun to form more comprehensive corporate policies concerning ethics. These policies generally offer guidance to employees and state the expectations of the company. Some companies require that employees sign a contract stating that they will follow the procedures within the handbook.

To be viewed by the public as having high moral standards, many companies have created a position called the corporate ethics officer or the corporate compliance officer. This person ensures their organization has statements of ethical principals, clear guideline about acceptable and unacceptable practices, and means of reporting ethical breaches. These executives also have the specific responsibility of monitoring ethical behavior and addressing breaches.

Promoting an Ethical Business Climate

There are at least four elements that create an atmosphere conducive to ethical behavior within an organization:

- A written code of ethics and standards

- Ethics training for executives, managers, and employees

- Availability for advice on ethical situations (i.e., advice lines or offices)

- Systems for confidential reporting

It is the duty of all managers to see that their organization maintains ethical practices and behaviors. Good leaders strive to create a better and more ethical organization. Promoting an ethical climate in an organization is critical, since it is a key component in addressing many other issues facing the organization.

10.5.2: Applying the Ethical Decision Tree

Decision trees are useful analytic tools for considering the ethical dimensions of a decision.

Learning Objective

Define the concept of a decision tree as it applies to the ethical dimensions of a decision.

Key Points

- Decision trees are used to identify alternatives and estimate their likely outcomes.

- Managers can use decision-tree analysis to consider the effect of each alternative on stakeholders such as employees, customers, shareholders, and communities.

- Decision-tree analysis can help identify or uncover the potential impacts of alternatives so that a decision maker can select the option that is most consistent with her ethical and moral beliefs.

Key Terms

- ethics

-

The study of principles relating to right and wrong conduct.

- decision tree

-

A visualization of a complex decision-making situation in which the possible decisions and their likely outcomes are organized in the form of a graph that resembles a tree.

Ethics are moral principles that guide a person’s behavior. These morals are shaped by social norms, cultural practices, and religious influences. All decisions have an ethical or moral dimension for a simple reason—they have an effect on others. Managers and leaders need to be aware of their own ethical and moral beliefs so they can draw on them when they face decisions. They can then effectively think through an ethical issue with the same types of approaches they use for other decisions.

Decision Trees

Decision trees are graphical representations of alternatives and possible outcomes. The decisions are represented by the branches of the tree. Organizations and individuals often use decision trees as part of their decision-making process because they are a means for adding formal structure to information about a decision. Identifying the range of possibilities and their potential consequences helps clarify the decision and facilitates selection of an alternative.

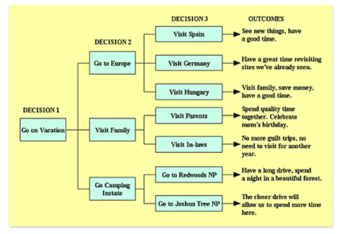

Decision tree

An example of a decision tree.

Decision trees can be applied to ethical matters as well. If confronted with an ethical dilemma, creating a decision tree is a useful method for analyzing what the potential outcomes of each action would be, and ultimately, how to proceed. It is a particularly useful tool for considering stakeholders such as employees, customers, shareholders, and communities. The answers to questions about what stakeholders will be affected and what the effects will be help build the case for or against each alternative. Often there will be competing interests, or situations in which two different values are in competition. For instance, a decision to close a coal mine because coal contributes to global warming may be positive for society at large, but it imposes high costs on the employees who will lose their jobs. Decision-tree analysis can help identify or uncover the potential impacts of alternatives so that a decision maker can select the one that is most consistent with her ethical and moral beliefs.

10.5.3: Applying the Decision Tree

Decision tree analysis can be a useful tool for evaluating ethical decisions.

Learning Objective

Express decision factors in an organized and structured view, allowing for systematic, ethical, and logical decision making

Key Points

- Decision tree analysis can be a useful tool for evaluating choices involved in ethical decisions.

- Laying out each consideration, potential action, and potential outcome can be useful in deciding which alternative is most likely to be consistent with your ethical and moral beliefs and values.

- Decision tree analysis should capture both quantitative and qualitative consequences of each alternative.

Key Terms

- utility

-

In economics, utility is a representation of preferences over some set of goods and services. Preferences have a utility representation so long as they are transitive, complete, and continuous.

- decision tree

-

A visualization of a complex decision-making situation in which the possible decisions and their likely outcomes are organized in the form of a branched graph.

Decision tree analysis provides a visual tool to help individuals quantify and weigh options against one another when making a decision. A decision tree calculates the expected values of competing alternative. This tells the decision maker which decision has the highest utility (i.e., is the most preferred) to the decision maker.

Decision tree

This example of a decision tree shows the decision maker trying to choose where to go on vacation.

Creating a Decision Tree

A decision tree consists of 3 types of nodes:

- Decision nodes: These are commonly represented by squares. Decision nodes are used when a decision needs to be made between at least two alternatives.

- Chance nodes: These may be represented by circles. Chance nodes represent points on the decision tree where there is uncertainty about outcomes (so there must be at least two possible outcomes represented).

- End nodes: These may be represented by triangles. An end node is where a decision is made and its value or utility is identified.

Applications of Decision Trees

Decision trees can be applied to ethical considerations. Consider an ethical dilemma involving a colleague. You are considering three options: report your colleague to a superior, confront the colleague yourself, or ignore the situation completely. The top box of the decision tree would state “Colleague Dilemma.”

The next three nodes would then read: “Report colleague to superiors,” “Confront colleague,” and “Ignore situation. ” Each of these nodes would then have a “Yes” arrow and a “No” arrow. For each “Yes” and “No,” you would list what the outcome would be, realizing that in some cases the nodes may need to continue to account for potential outcomes, some of which may link back to previous options. For example, a “Yes” decision arrow for “Report colleague to superiors” may result in the situation being taken care of—or, it could result in an investigation that would impact your standing within the company and with your peers. If you chose to ignore the colleague and his unethical behavior is discovered in the future, you could end up in trouble for choosing not to act earlier.

A decision tree for a tough problem allows the decision maker to visually lay out each scenario and make a detailed consideration. Decision trees therefore support the evaluation process and can help clarify often-complex ethical dilemmas.

10.6: Barriers to Decision Making

10.6.1: Cognitive Biases as a Barrier to Decision Making

Individual cognitive biases will influence decision making.

Learning Objective

Examine the complex individual influences central to the way in which decision making is pursued, most notably the cognitive, normative, and psychological perspectives

Key Points

- Decision making is shaped by individual personality and behavioral characteristics.

- Subjective biases can influence decisions by disrupting objective judgments.

- Common cognitive biases include confirmation, anchoring, halo effect, and overconfidence.

Key Term

- dichotomies

-

Two elements, often mutually exclusive, that stand in juxtaposition to one another.

Decision making is inherently a cognitive activity, the result of thinking that may be either rational or irrational (i.e., based on assumptions not supported by evidence). Individual characteristics including personality and experience influence how people make decisions. As such, an individual’s predispositions can either be an obstacle or an enabler to the decision-making process.

From the psychological perspective, decisions are often weighed against a set of needs and augmented by individual preferences. Abraham Maslow’s work on the needs-based hierarchy is one of the best known and most influential theories on the topic of motivation—according to his theory, an individual’s most basic needs (e.g., physiological needs such as food and water; a sense of safety) must be met before an individual will strongly desire or be motivated by higher-level needs (e.g., love; self-actualization.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is a widely used diagnostic for identifying personality characteristics. By categorizing individuals in terms of four dichotomies—thinking and feeling, extroversion and introversion, judging and perception, and sensing and intuition—the MBTI provides a map of the individual’s orientation toward decision making.

Types of Cognitive Bias

Biases in how we think can be major obstacles in any decision-making process. Biases distort and disrupt objective contemplation of an issue by introducing influences into the decision-making process that are separate from the decision itself. We are usually unaware of the biases that can affect our judgment. The most common cognitive biases are confirmation, anchoring, halo effect, and overconfidence.

1. Confirmation bias: This bias occurs when decision makers seek out evidence that confirms their previously held beliefs, while discounting or diminishing the impact of evidence in support of differing conclusions.

2. Anchoring: This is the overreliance on an initial single piece of information or experience to make subsequent judgments. Once an anchor is set, other judgments are made by adjusting away from that anchor, which can limit one’s ability to accurately interpret new, potentially relevant information.

3. Halo effect: This is an observer’s overall impression of a person, company, brand, or product, and it influences the observer’s feelings and thoughts about that entity’s overall character or properties. It is the perception, for example, that if someone does well in a certain area, then they will automatically perform well at something else regardless of whether those tasks are related.

4. Overconfidence bias: This bias occurs when a person overestimates the reliability of their judgments. This can include the certainty one feels in her own ability, performance, level of control, or chance of success.

10.6.2: Time Pressure as a Barrier to Decision Making

Time pressure forces decision makers to shift from logical processes (ideal) to intuitive processes (sub-ideal).

Learning Objective

Explain the way in which time pressure can influence decision making

Key Points

- Time pressure can distort decision-making processes and individual judgment and make them less objective and more influenced by intuition.

- Heuristics, or mental shortcuts, can deliver workable decisions under time pressure and in the absence of logical decision-making processes.

- Decision makers who feel as though they have ample time tend to arrive at more logically crafted, higher quality decisions than those who felt as though they had insufficient amounts of time, even if confronted by similar time pressure in real terms.

- While generally considered a barrier to decision making, time pressures may also have the opposite effect in terms of creating organizational motivation to render decisions and move on. In this way time pressure, real or perceived, may act as a deadline and encourage organizational dexterity.

Key Term

- heuristic

-

A “shortcut” method of problem solving that makes assumptions based on past experiences. Examples include going by “rule of thumb,” when you apply your experience of something having happened a certain way enough times that it’s likely to continue happening that way. It is not guaranteed to be accurate every single time, but it cuts out processing time by avoiding detailed analysis of every particular situation.

Just as individual characteristics and cognitive biases can shape decision making, time pressure can also distort how we consider and choose between alternatives. Severe time constraints can make decision processes and individual judgment less objective and more influenced by intuition as more formal and rigorous approaches are ignored. All decisions are time-bound in the sense that we do not have an infinite amount of time to make a selection. Still, firm and proximate deadlines and limited resources are common causes of time pressure. Information overload is another. While considering all relevant factors is important to build support for the decision, data collection can eat up time better spent analyzing alternatives and making the decision itself.

There are some effective approaches to dealing with time pressure. Clearly defining the decision and its parameters early on can reduce ambiguity and make it easier to hone in on relevant data. Setting clear boundaries on matters such as who will participate and how long discussions will continue can similarly manage the amount of time given to a decision. In many instances, the use of heuristics can be applied to complex decisions to serve as shortcuts in conducting analysis and weighing alternatives.

Time pressure

Time pressure often forces decision makers to look for intuitive shortcuts rather than logically processing all of the required data.

There is evidence that suggests the perception of time pressure may impact decision quality. Decision makers who believe they have ample time to make a decision tend to arrive at more logically crafted decisions than those who feel as though they have an insufficient amount of time. While time pressure is generally perceived as being a barrier to effective decision making, it may also have the exact opposite effect. A limited time frame can focus mental energy and effort to bring the appropriate resources to bear on a decision more quickly and efficiently than otherwise might have been the case.