5.1: Commas

5.1.1: Introduction to Commas

The comma is a punctuation mark that indicates a slight break, pause, or transition.

Learning Objective

Identify situations that require commas

Key Points

- The comma is a punctuation mark that indicates a slight break, pause, or transition.

- Commas are necessary before a coordinating conjunction (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so) that separates two independent clauses.

- Commas are necessary after introductory words, phrases, or clauses in a sentence.

- Commas are necessary to set off elements that interrupt or add information in a sentence.

Key Terms

- participle

-

A form of a verb that may function as an adjective or noun. English has two types of participles: the present participle and the past participle.

- preposition

-

Any of a closed class of non-inflecting words typically employed to connect a noun or a pronoun, in an adjectival or adverbial sense, with some other word: a particle used with a noun or pronoun (in English always in the objective case) to make a phrase limiting some other word.

- adverb

-

A word that modifies a verb, adjective, another adverb, or various other types of words, phrases, or clauses.

- adjective

-

A word that modifies a noun or describes a noun’s referent.

- infinitive

-

The uninflected form of a verb. In English, this is usually formed with the verb stem preceded by “to.” For Example: “to sit.”

- nonrestrictive

-

Describes a modifier that can be dropped from a sentence without changing the meaning.

The comma is a punctuation mark that indicates a slight pause or a transition of some kind. It serves many different grammatical functions and provides clarity for readers. Commas have many uses, but the situations in which they are used can be broken down into four major categories:

- Put a comma before a coordinating conjunction (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so) that separates two independent clauses.

- Put a comma after introductory words, phrases, or clauses in a sentence.

- Use commas to set off elements that interrupt or add information in a sentence.

- Use commas to visually separate distinct but related items.

Coordinating Conjunctions

Coordinating conjunctions are conjunctions, or joining words, that are placed between words and phrases of equal importance. Used with coordinating conjunctions, commas allow writers to express how their complete thoughts relate to one another. They also help avoid the choppy, flat style that arises when every thought stands as a separate sentence.

When joining two independent clauses, or clauses that could stand on their own as full sentences, place a comma before the conjunction. If the second independent clause is very short, or if it is an imperative, the comma can be omitted.

Example: He was looking forward to the dance, but he was not sure what he would wear.

Both clauses are independent and could stand on their own as complete sentences. When they are joined in the same sentence, however, they must be connected with a comma and a coordinating conjunction.

Introductory Phrases and Clauses

Put a comma after introductory words, phrases, or clauses that introduce a sentence.

Dependent Clauses

A dependent clause is a group of words that can’t stand on its own as a sentence because it does not express a complete thought. Sometimes a dependent clause can be used to introduce a sentence. In this situation, use a comma after the dependent clause.

Example: Because I was running late, I did not have time to eat breakfast.

The first phrase could not stand on its own as a sentence, but when joined to the independent clause by the comma, the sentence is complete.

Note that a dependent clause can come later in the sentence, but in that case, you would not use a comma:

Example: I did not have time to eat breakfast because I was running late.

Only use a comma to separate a dependent and independent clause if the dependent clause is first!

Introductory Words and Phrases

Writers can give readers information that limits or otherwise modifies a main idea that follows. To do so, writers can use introductory words or introductory phrases. These introductory elements can be one word or several. Common introductory elements include transition words and statements about time, place, manner, or condition.

Often, introductory words are also adverbs. Commas are always used to set off certain adverbs, including the following:

- however

- in fact

- therefore

- nevertheless

- moreover

- furthermore

- still

Example: Therefore, it is obvious that we should fund the dam-building project.

If one of these adverbs appears in the middle of a sentence, within one clause, it should be set off by a pair of commas.

Example: The dam, however, will take seven years to construct.

For some adverbs, using a comma is optional. In these situations, say the sentence to yourself. If you think a pause makes your sentence more clear or emphasizes what you want to emphasize, use the comma; otherwise, drop it.

- then

- so

- yet

- instead

- too

- first, second, etc.

Example: First we’ll go to the mall. Then we’ll go to the pet store.

Example: First, we’ll go to the mall. Then, we’ll go to the pet store.

Both of those sentence pairs are correct!

Adding Information: Modifiers and Appositives

Modifiers are words or phrases that are added to sentences in order to make their meaning more specific. In order to understand what kind of modifiers require commas, first we have to understand the concept of “restrictiveness.”

Nonrestrictive Modifiers

Some modifiers are nonrestrictive, meaning that the sentence would still have essentially the same meaning, topic, and structure without them. They simply add a little extra information.

Example: Katy’s new fishbowl is growing some weird algae.

In this sentence, “new” and “weird” are nonrestrictive. The sentence without them would be grammatically correct and have essentially the same meaning. They do not require any commas.

Restrictive Modifiers

Restrictive modifiers, on the other hand, are those whose use is essential to the overall meaning of the sentence. In other words, if you dropped a restrictive modifier from a sentence, the meaning of the sentence would change.

Example: The man who scratched your car left a note on your windshield.

The phrase “who scratched your car” is a restrictive modifier because it explains which man the sentence refers to, and because the sentence would be unclear without it.

Appositives

An appositive is a grammatical construction in which two noun phrases are placed side by side, with one identifying the other.

Example: My sister, Alice Smith, likes jelly beans.

In this sentence, “Alice Smith” is an appositive modifying the noun phrase “my sister.” Because the name Alice Smith is just adding information, and the sentence would still have the same basic meaning without it, this is an example of a nonrestrictive appositive. Nonrestrictive appositives do require commas.

On the other hand, a restrictive appositive provides information essential to identifying the noun being described. It limits or clarifies that noun phrase in some crucial way, and the meaning of the sentence would change if the appositive were removed. In English, restrictive appositives are not set off by commas.

Example: He loves the television show Iron Chef.

In this sentence, “Iron Chef” is an appositive modifying the noun phrase “television show.” Because the meaning of the sentence would be unclear without “Iron Chef,” it is considered restrictive and thus does not require a comma.

Separating Related But Distinct Information

Attribution

Use a comma to set off the attribution (i.e., who said or wrote a quotation) from the quotation itself. If the attribution comes at the end of the quotation, then the comma should go inside the quotation marks, even if the quotation is a complete sentence.

Example: “We really messed up this time,” he said.

A pair of commas should be used to set off the attribution when it appears in the middle of the quotation.

Example: “Well,” she said, “I think I would prefer to have hamburgers tonight.”

Do not replace a question mark or exclamation point in a quotation with a comma.

Example: “Where are we going now?” Eugene asked.

Lists

When there are three or more items in a list, commas should be used between the items.

Example: Buy apples, bananas, and grapefruit at the store.

The final comma, the one before and or or, is known as a serial comma (also called the Oxford or Harvard comma). The serial comma should always be used where it is needed to avoid confusion. Can you see the ambiguity in the example below?

Example: “Thank you for the award. I’d like to thank my parents, Charles Darwin and Lindsay Lohan.”

It looks like the speaker’s parents are Darwin and Lohan, when in reality, the speaker meant to thank her parents and Charles Darwin and Lindsay Lohan. In this situation, the serial comma needs to be used.

Otherwise, depending on the chosen style guide, it is considered optional. Still, not using the serial comma is relatively uncommon in American English, except in newspapers and magazines.

Accumulation

Another type of relationship between ideas that writers signal to readers with a comma is that of accumulation. Occurring at the end of a sentence, cumulative clauses hook up to a main clause and add further information. They often include additional descriptive details.

Example, “The sun rose slowly over the mountains, warming the faces of the miners in the valley, inviting the jays out from their nests, shimmering in the morning dew, inching the day forward one shadow at a time.”

As in this example, accumulative phrases should be separated by commas.

Dates

Commas should also be used when writing dates. There should always be a comma between the day and the year and between the year and the rest of the sentence.

Example: “On December 7, 1941, Japanese planes attacked the U.S. Naval base in Hawaii.”

Even when the date is not a dependent clause, as it is in the previous example, the last item in the date should be followed by a comma.

Calling in sick for work, Beth hoped her boss would not suspect anything

The title contains a verb in its introductory phrase, which warrants a comma before the final clause. The comma serves a variety of grammatical functions, including to indicate pauses or set off introductory phrases, as in the title example.

5.1.2: Common Comma Mistakes

By understanding the rules of correct comma usage, you can avoid common comma errors.

Learning Objective

Recognize common mistakes when using commas

Key Points

- Avoiding unnecessary commas is simply a matter of understanding the rules of correct comma usage.

- A comma splice occurs when two independent clauses are joined only by a comma instead of an acceptable form of punctuation, such as a comma with a coordinating conjunction, a semicolon, or a period.

- A run-on sentence occurs when two or more independent clauses fuse together without punctuation to separate them.

Key Terms

- preposition

-

Any of a closed class of non-inflecting words typically employed to connect a noun or a pronoun, in an adjectival or adverbial sense, with some other word: a particle used with a noun or pronoun (in English always in the objective case) to make a phrase limiting some other word.

- participle

-

A form of a verb that may function as an adjective or noun. English has two types of participles: the present participle and the past participle.

- comma

-

Punctuation mark, usually indicating a pause between parts of a sentence or between elements in a list.

Rules of Thumb

Comma usage errors fall into two categories: using unnecessary commas and failing to use necessary commas. To avoid making errors when using commas in your writing, you must understand when commas belong (and when they don’t).

Keep the following rules of thumb in mind for when to not use commas.

Do not use a comma to separate a subject from its predicate.

- Incorrect: Registering for our fitness programs before September 15, will save you thirty percent of the membership cost.

- Correct: Registering for our fitness programs before September 15 will save you thirty percent of the membership cost.

Do not use a comma to separate a verb from its object, or a preposition from its object.

- Incorrect: I hope to mail to you before Christmas, a current snapshot of my dog Benji.

- Incorrect: She traveled around the world with, a small backpack, a bedroll, a pup tent, and a camera.

- Correct: I hope to mail to you before Christmas a current snapshot of my dog Benji.

- Correct: She traveled around the world with a small backpack, a bedroll, a pup tent, and a camera.

Do not misuse a comma after a coordinating conjunction.

- Incorrect: Sleet fell heavily on the tin roof but, the family was used to the noise and paid it no attention.

- Correct: Sleet fell heavily on the tin roof, but the family was used to the noise and paid it no attention.

Do not use commas to introduce restrictive (i.e., necessary) modifiers.

- Incorrect: The fingers, on his left hand, are bigger than those on his right.

- Correct: The fingers on his left hand are bigger than those on his right.

Do not use a comma before a dependent clause that comes after an independent clause. This is called a disruptive comma.

- Incorrect: The future of print newspapers appears uncertain, due to rising production costs and the increasing popularity of online news sources.

- Incorrect: Some argue that print newspapers will never disappear, because of their many readers.

- Correct: The future of print newspapers appears uncertain due to rising production costs and the increasing popularity of online news sources.

- Correct: Some argue that print newspapers will never disappear because of their many readers.

Do not use a comma after a short introductory prepositional phrase unless you mean to add extra emphasis.

- Incorrect: Before the parade, I want to eat pizza.

- Correct: Before the parade I want to eat pizza.

Do not use a comma between adjectives that work together to modify a noun.

- Incorrect: I like your dancing, cat t-shirt.

- Correct: I like your dancing cat t-shirt.

Do not use a comma to set off quotations that occupy a subordinate position in a sentence, often signaled by the words “that,” “which,” or “because.”

- Incorrect: Participating in a democracy takes a strong stomach because, “it requires a certain relish for confusion,” writes Molly Ivins.

- Correct: Participating in a democracy takes a strong stomach because “it requires a certain relish for confusion,” writes Molly Ivins.

Do not use a comma when naming only a month and a year.

- Incorrect: The next presidential election will take place in November, 2016.

- Correct: The next presidential election will take place in November 2016.

Do not use a comma in street addresses or page numbers, or before a ZIP or other postal code.

- Correct: The table appears on page 1397.

- Correct: The fire occurred at 5509 Avenida Valencia.

- Correct: Write to the program advisor at 645 5th Street, Minerton, Indiana 55555.

Comma Splice Errors

A comma splice occurs when two independent clauses (that is, two complete sentences) are joined only by a comma. In those situations, an acceptable form of punctuation would be a semicolon or a period. For example:

- Incorrect: Every day, millions of children go to daycare with millions of other kids, there is no guarantee that none of them are harboring infectious conditions.

- Incorrect: Many daycares have strict rules about sick children needing to stay away until they are no longer infectious, enforcing those rules can be very difficult.

- Incorrect: Daycare providers often undergo extreme pressure to accept a sick child “just this once,” the parent has no other care options and cannot miss work.

Once you discover where the two independent clauses are “spliced,” there are several ways to separate them. You can make two complete sentences by inserting a period. This is the strongest level of separation. You can use a semicolon between the two clauses if they are of equal importance; this allows your reader to consider the points together. You can use a semicolon with a transition word to indicate a specific relation between the two clauses; however, you should use this sparingly. You can use a coordinating conjunction following the comma, and this also will indicate a relationship. Or, you can add a word to one clause to make it dependent.

For example:

- Correct: Every day, millions of children go to daycare with millions of other kids. There is no guarantee that none of them are harboring infectious conditions.

- Correct: Many daycares have strict rules about sick children needing to stay away until they are no longer infectious; enforcing those rules can be very difficult.

- Correct: Many daycares have strict rules about sick children needing to stay away until they are no longer infectious, but enforcing those rules can be very difficult.

- Correct: Daycare providers often undergo extreme pressure to accept a sick child “just this once” because the parent has no other care options and cannot miss work.

Run-On Errors

While a run-on sentence, also known as a fused sentence, might just seem like a type of sentence that goes on and on without a clear point, the technical grammatical definition of a run-on sentence is one that fuses, or “runs together,” two or more independent clauses without using punctuation to separate them. The independent clauses may not have any punctuation separating them, or they may have a coordinating conjunction between them, but without the comma that needs to accompany it to separate the independent clauses. For example:

- Incorrect: Every day, millions of children go to daycare with millions of other kids there is no guarantee that none of them are harboring infectious conditions.

- Incorrect: Many daycare centers have strict rules about sick children needing to stay away until they are no longer infectious but enforcing those rules can be very difficult.

- Incorrect: Daycare providers often undergo extreme pressure to accept a sick child “just this once” the parent has no other care options and cannot miss work.

If you locate a run-on sentence and find where the two independent clauses “collide,” you can decide how best to separate the clauses. Fixing run-on sentences is very similar to fixing comma splices. You can make two complete sentences by inserting a period. This is the strongest level of separation. You can use a semicolon between the two clauses if they are of equal importance; this allows your reader to consider the points together. You can use a semicolon with a transition word to indicate a specific relation between the two clauses; however, you should use this sparingly. You can use a coordinating conjunction and a comma, and this also will indicate a relationship. Or, you can add a word to one clause to make it dependent.

For example:

- Correct: Every day, millions of children go to daycare with millions of other kids. There is no guarantee that none of them are harboring infectious conditions.

- Correct: Many daycares have strict rules about sick children needing to stay away until they are no longer infectious; however, enforcing those rules can be very difficult.

- Correct: Many daycares have strict rules about sick children needing to stay away until they are no longer infectious, but enforcing those rules can be very difficult.

- Correct: Daycare providers often undergo extreme pressure to accept a sick child “just this once” because the parent has no other care options and cannot miss work.

5.2: Colons and Semicolons

5.2.1: Colons

Colons are used to introduce detailed lists or phrases and to show relationships between numbers, facts, words, and lists.

Learning Objective

Identify sentences that require colons

Key Points

- A colon can introduce the logical consequence, or effect, of a previously stated fact.

- A colon can introduce the elements of a set or list.

- Colons separate chapter and verse numbers in citations of passages in widely studied texts, such as epic poetry, religious texts, and the plays of William Shakespeare. A colon can also separate the subtitle of a work from its principal title.

- Colons may also

separate the numbers indicating hours, minutes, and seconds in abbreviated measures of time. - Sometimes, a colon can introduce speech or dialogue.

Key Terms

- enumeration

-

A detailed account in which each thing is noted.

- appositive

-

A word or phrase that is placed with another as an explanatory equivalent.

Using Colons in Sentences

Some punctuation marks, such as periods, question marks, and exclamation points, indicate the end of a sentence. However, commas, semicolons, and colons all can appear within a sentence without ending it.

The colon has a wide range of uses. The most common use is to inform the reader that whatever follows the colon proves, explains, defines, describes, or lists elements of what preceded the colon. Essentially, sentences that are divided by colons are of the form, “Sentence about something: list or definition related to that sentence.”

In modern American English usage, a colon must be preceded by a complete sentence with a list, a description, an explanation, or a definition following it. The elements that follow the colon may or may not be complete sentences. Because the colon is preceded by a sentence, it is a complete sentence whether what follows the colon is another sentence or not.

In American English, many writers capitalize the word following a colon if it begins an independent clause—that is, a clause that can stand as a complete sentence. The Chicago Manual of Style, however, requires capitalization only when the colon introduces speech or a quotation, a direct question, or two or more complete sentences.

Other Uses of the Colon

In addition to being used in the middle of sentences, colons can also be used to visually separate information.

Separating Chapters and Verses

A colon should be used to separate chapter and verse numbers in citations of passages in widely studied texts, such as epic poetry, religious texts, and the plays of William Shakespeare.

- Example: John 3:14–16 refers to verses 14 through 16 of chapter three of the Gospel of John.

Separating Numbers in Time Abbreviations

- Example: The concert begins at 11:45 PM.

- Example: The rocket launched at 09:15:05 AM.

Separating Titles and Subtitles

An appositive colon also separates the subtitle of a work from its principal title.

- Example: Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope

Introducing Speech

Similar to a dash and a quotation mark, a segmental colon can introduce speech.

- Example: Benjamin Franklin proclaimed the virtue of frugality: “A penny saved is a penny earned.”

This form can also be used in written dialogues, such as plays. The colon indicates that the words following an individual’s name are spoken by that individual.

- Example:

Patient: Doctor, I feel like a pair of curtains.

Doctor: Pull yourself together!

5.2.2: Semicolons

Semicolons are used to link related clauses and to separate information in lists that contain additional punctuation.

Learning Objective

Identify when and how to use semicolons properly

Key Points

- Semicolons connect two closely related, independent clauses (complete sentences) and turn them into a single sentence.

- Semicolons take the place of periods or commas followed by coordinating conjunctions (FANBOYS: for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so).

- Semicolons should be used before conjunctive adverbs (however, meanwhile, therefore, otherwise, in addition, and others) to link together sentences. Follow conjunctive adverbs with a comma.

- Semicolons can be used in lists that include lots of commas.

Key Terms

- coordinating conjunction

-

Simple words that connect two independent clauses together or connect an independent clause to a dependent clause (sentence fragment). They are remembered by the acronym FANBOYS.

- dependent clause

-

This group of words also contains a subject and/or verb, but do not create a complete, stand-alone sentence.

- conjunctive adverbs

-

These words are preceded by a semicolon and followed by a comma. There is a long list, but here are some examples: however, meanwhile, in addition, and therefore.

- independent clause

-

A group of words that contains a subject (noun) and a verb and can stand as a complete sentence.

Semicolons link together independent clauses that are closely related, making them flow into a single sentence. Often, using a period to separate related sentences makes them seem choppy. A semicolon is an alternative to using a period or a comma plus coordinating conjunction. Semicolons used before conjunctive adverbs also replace periods. It is important to understand that using a semicolon in place of a period fuses two independent clauses into one; therefore, make sure you don’t start the second independent clause with a capital letter. The final use of semicolons is to separate items in a list or series with lots of commas or other punctuation.

Linking Independent Clauses

Semicolons can be used to join closely related, independent clauses. There are three ways to link independent clauses: with a period, a semicolon, or a comma plus coordinating conjunction (FANBOYS).

- With a period: John finished his homework. He forgot to pass it in.

- With a semicolon: John finished his homework; he forgot to pass it in.

- With a comma plus a coordinating conjunction: John finished his homework, but he forgot to pass it in.

Remember, use of a semicolon is only appropriate if the sentences have a strong relationship to each other.

Independent Clauses Linked with Conjunctive Adverbs

Semicolons can also be used between independent clauses linked with a conjunctive adverb. Follow the conjunctive adverbs with a comma. This usage is very formal, and is typically found in academic tests.

- Example: Everyone knows he committed the crime; accordingly, we expect the jury to agree on a guilty verdict.

- Example: The students failed to finish their in-class assignment; therefore, they are required to remain after school.

Listing Items in a Series

Semicolons are used between items in a list or series when those items themselves contain internal punctuation.

- Example: Several fast-food restaurants can be found within the following cities: London, England; Paris, France; Dublin, Ireland; and Madrid, Spain.

- Example: Here are three examples of familiar sequences: one, two, three; a, b, c; first, second, third.

- Example:

Dental hygienists perform clerical jobs such as bookkeeping, answering phones, and filing; administrative jobs such as filing out insurance claims and maintaining patient

files; and clinical jobs such as making impressions of the teeth and gums, taking x-rays, and removing sutures.

Formatting with Semicolons

Capitalization

Semicolons are typically followed by a lowercase letter, unless that letter is the first letter of a proper noun like “I” or “Paris.” In some style guides, such as APA, however, the first word of the joined independent clause should be capitalized.

Spacing

Modern style guides recommend no space before semicolons and one space after. Modern style guides also typically recommend placing semicolons outside of ending quotation marks.

5.3: Apostrophes and Quotation Marks

5.3.1: Apostrophes

Apostrophes are used to mark contractions, possessives, and some plurals.

Learning Objective

Identify words which require apostrophes

Key Points

- Apostrophes can be used to indicate possessives (for example, “my dad’s recipe.”)

- Apostrophes can be used to form contractions, where they indicate the omission of characters (for example, “don’t” instead of “do not.”)

- Apostrophes can also be used to form plurals for abbreviations, acronyms, and symbols in cases where forming a plural in the conventional way would make the sentence ambiguous.

Key Term

- apostrophe

-

A punctuation mark, and sometimes a diacritic mark, in languages that use the Latin alphabet or certain other alphabets.

Using Apostrophes to Show Possession

Apostrophes can be used to show who owns or possesses something.

For Nouns Not Ending in -s

The basic rule is that to indicate possession, add an apostrophe followed by an “s” to the end of the word.

- The car belonging to the driver = the driver’s car.

- The sandwich belonging to Lois = Lois’s sandwich.

- Hats belonging to children = children’s hats.

For Nouns Ending in -s

However, if the word already ends with “s,” just use the apostrophe with no added “s.” For example:

- The house belonging to Ms. Peters = Ms. Peters’ house. (Even though Ms. Peters is singular. )

The same holds true for plural nouns, if their plural ends in “s.” Just use an apostrophe for these!

- Three cats’ toys are on the floor.

- The two ships’ lights shone through the dark.

For More Than One Noun

In sentences where two individuals own one thing jointly, add the possessive apostrophe to the last noun. If, however, two individuals possess two separate things, add the apostrophe to both nouns. For example:

- Joint: I went to see Anthony and Anders’ new apartment. (The apartment belongs to both Anthony and Anders.)

- Individual: Anders’ and Anthony’s senses of style were quite different. (Anders and Anthony have individual senses of style.)

For Compound Nouns

In cases of compound nouns composed of more than one word, place the apostrophe after the last noun. For example:

- Dashes: My brother-in-law’s house is down the block.

- Multi-word: The Minister for Justice’s intervention was required.

- Plural compound: All my brothers-in-law’s wives are my sisters.

For Words Ending in Punctuation

If the word or compound includes, or even ends with, a punctuation mark, an apostrophe and an “s” are still added in the usual way. For example:

- Westward Ho!’s railway station

- Louis C.K.’s HBO special

For Words Ending in -‘s

If an original apostrophe, or apostrophe with s, is already included at the end of a noun, it is left by itself to perform double duty. For example:

- Our employees are better paid than McDonald’s employees.

- Standard & Poor’s indexes are widely used.

The fixed, non-possessive forms of McDonald’s and Standard & Poor’s already include possessive apostrophes.

Don’t Use Apostrophes For …

Nouns that are not possessive. For example:

- Incorrect: Some parent’s are more strict than mine.

Possessive pronouns such as its, whose, his, hers, ours, yours, and theirs. These are the only words that are able to be possessive without apostrophes. For example:

- Incorrect: That parakeet is her’s.

Using Apostrophes to Form Contractions

In addition to serving as a marker for possession, apostrophes are also commonly used to indicate omitted characters. For example:

- can’t (from cannot)

- it’s (from it has or it is)

- you’ve (from you have)

- gov’t (from government)

- ’70s, (from 1970s)

- ’bout (from about)

An apostrophe is also sometimes used when the normal form of an inflection seems awkward or unnatural. For example:

- K.O.’d rather than K.O.ed (where K.O. is used as a verb meaning “to knock out”)

Using Apostrophes to Form Plurals

Apostrophes are sometimes used to form plurals for abbreviations, acronyms, and symbols where adding just s as opposed to ‘s may leave things ambiguous or inelegant. For example, when you are pluralizing a single letter:

- All of your sentences end with a’s. (As opposed to “All of your sentences end with as.”)

- She tops all of her i’s with hearts. (As opposed to “She tops all of her is with hearts.”)

In such cases where there is little or no chance of misreading, however, it is generally preferable to omit the apostrophe. For example:

- He scored three 8s for his floor routine. (As opposed to “three 8’s.”)

- She holds two MAs, both from Princeton. (As opposed to “two MA’s.”)

5.3.2: Quotation Marks

Quotation marks are most often used to mark direct speech or words from another author or speaker.

Learning Objective

Identify situations which require quotation marks

Key Points

- Quotation marks indicate words that are spoken by someone who is not the author.

- Quotation marks are also used to title short literary works such as poems, short stories, essays, and newspaper and magazine articles.

- Quotation marks can also be used to show irony or highlight specific words.

- In research papers, it is important to use quotation marks to highlight the work of another author when directly quoting that author.

Key Term

- quotation mark

-

A punctuation mark used to denote speech or when words are copied from another author or speaker; can be double quotations (“) or single quotations (‘).

Quotation marks are most commonly used

to mark direct speech or identify the words of another author or speaker.

Quotation marks can also be used to highlight specific words, express the title of a short literary work, or to emphasize irony.

Speech

Single or double quotation

marks denote either speech or a quotation. Double quotes are preferred in the

United States. Regardless, the style of opening and closing quotation marks

must match. For example:

- Single quotation marks: ‘Good

morning, Frank,’ said Hal. -

Double quotation marks: “Good

morning, Frank,” said Hal.

For speech within speech,

use double quotation marks on the outside, and single marks on the inner quotation. For example:

-

“Hal said, ‘Good morning,

Dave,'” recalled Frank.

When

quoted text is interrupted, a closing quotation mark is used before the interruption, and an

opening quotation mark is used after the interruption. Commas are often used

before and after the phrase as well. For example:

- “Hal said everything was going well,” noted Frank,

“but also that he could use a little help.”

Quotation marks are not

used for paraphrased speech because a paraphrase is not a direct quote. Quotation marks represent another person’s exact words.

Quoting Literature and Research

In most cases, quotations

that span multiple paragraphs should be set as block quotations, and thus do

not require quotation marks. When quotation marks are used for

multiple-paragraph quotations, the convention in English is to give opening

quotation marks to the first and each subsequent paragraph, using closing

quotation marks only for the final paragraph of the quotation.

In research papers and

literary analyses writers often need to quote a sentence or a phrase. One

will need to use quotation marks when quoting authors to show which words are

from the other work. Here is an example sentence:

- When J. K. Rowling began

writing the Harry Potter series, she never expected “the boy who lived” to

become known worldwide.

In this example, it is clear that the phrase “the

boy who lived” is from J. K. Rowling’s book.

Titles

As

a rule, a whole publication should be italicized. For example, Harry

Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone is

italicized because it is a book. The titles of sections within a larger publication or of smaller works (such as poems, short stories, named chapters,

journal papers, newspaper articles, TV show episodes, editorial sections of

websites, etc.) should be written within quotation marks. Thus, when

referencing a chapter from the book one would use quotation marks: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone begins with the chapter entitled “The Chosen

One.”

Let’s explore some other

examples.

- Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet

- Dahl’s “Taste” in Completely Unexpected Tales

- Arthur C. Clarke’s “The

Sentinel” - The first chapter of 3001: The Final Odyssey is “Comet Cowboy”

- “Extra-Terrestrial

Relays,” Wireless

World, October 1945 - David Bowie’s song “Space

Oddity” from the album David Bowie

Nicknames

Quotation marks can also

offset a nickname embedded in an actual name, or a false or ironic title

embedded in an actual title. For example:

-

Nat “King” Cole

-

Miles “Tails” Prower

-

Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson

Use-Mention Distinctions

Either quotation marks or

italics can indicate when a word refers to the word itself rather than its associated concept (i.e., when the word is “mentioned” rather than “used”).

- Cheese is derived from milk. [Use]

- Cheese has calcium, protein, and phosphorus. [Use]

- “Cheese” is derived from

a word in Old English. [Mention] - Cheese has three e’s. [Mention]

Irony

Quotes indicating verbal

irony or another special use are sometimes called scare quotes. For example:

- He shared his “wisdom”

with me. -

The lunch lady plopped a glob of

“food” onto my tray.

Quotation marks are also

sometimes used to indicate that the writer realizes that a word is not being

used in its current commonly accepted sense. In these cases, the quotation

marks can call attention to slang, special terminology, a neologism, or they

can indicate words or phrases that are unusual, colloquial,

folksy, startling, humorous, metaphoric, or that contain a pun. For example:

- Crystals somehow “know”

which shape to grow into. - I hope your diving meet goes

“swimmingly”!

Using quotation marks in

these ways should be avoided when possible.

Punctuating Quotations

In English, question marks and exclamation marks are placed inside or outside quoted material depending on whether they apply to the whole sentence or just the quoted portion. Commonly, they apply to the quoted portion and will be included inside the quotation marks. In some situations, however, the exclamation mark or question mark will apply to the sentence as a whole and will come after the quotation mark. In contrast, colons and semicolons are always placed outside of the quotation marks. Let’s explore this punctuation rule further with some examples.

- Did he say, “Good morning, Dave”? (The question mark does not refer to the phrase within the quotation marks so the question mark is placed outside of the quotation marks.)

- No, he said, “Where are you, Dave?” (Here, the question mark is part of the question posed within the quotation marks.)

- There are three major definitions of the word “gender”: vernacular, sociological, and linguistic. (Colons and semicolons always come after the quotation mark.)

In American English, commas and periods are usually placed inside quotation marks, except in the few cases where they may cause serious ambiguity. For example:

- “Carefree,” in general, means “free from care or anxiety.”

- The name of the song was “Gloria,” which many already knew.

- She said she felt “free from care and anxiety.”

- “Today,” said the Prime Minister, “I feel free from care and anxiety.”

- To use a long dash on Wikipedia, type in “—”. (Here, the period comes after the quotation mark because quotation marks are used to highlight specifically what should be typed.)

The style used in the UK contains only punctuation used by the original source, placing commas, periods, question marks, and exclamation marks inside or outside quotation marks depending on where they were placed in the material that is being quoted.

- “Carefree” means “free from care or anxiety.” (American style)

- “Carefree” means “free from care or anxiety”. (British style)

5.4: Hyphens and Dashes

5.4.1: Hyphens

Hyphens are often used to connect two words into a single term.

Learning Objective

Identify situations which require a hyphen

Key Points

- Hyphens connect two words to make a single word.

- Hyphens are also used to attach a prefix to a word.

- In some situations, hyphens connect adverbs and adjectives to describe a noun. This can be avoided by rewording the sentence.

- The placement of a hyphen can greatly change the meaning of a word and thus the entire sentence.

Key Terms

- hyphen

-

The symbol “-“, typically used to join two or more words to form a new word.

- homograph

-

A word that is spelled the same as another but has a different meaning and usually sounds different.

Hyphens (“-“) connect two words to make a single

word. Though they look similar to dashes (“–” and “—”), they serve a different purpose. The dash is

a form of punctuation that comes in between words whereas hyphens combine words.

Like most components of English punctuation, hyphens have general rules

regarding how they should be used. Hyphens are often used to connect adverbs and adjectives

when describing a noun. Let’s explore these concepts in greater detail.

Linking Prefixes

Hyphens can be used to link prefixes such as non-, sub-, and

super- to their main words. While it is possible (especially in American

English) to attach these prefixes without hyphens, it is generally helpful to

hyphenate when the letters brought into contact are the same. It’s also helpful

when the letters are vowels, when a word is uncommon, or when the word could

easily be misread. For example:

- Non-negotiable

- Sub-basement

- Pre-industrial

Units

In general, values and

units are hyphenated when the unit is given as a whole word:

- 30-year-old man

- One half-dose

Homographs

Homographs are words that are spelled the same, but mean different

things and may be pronounced differently. To prevent confusion, hyphens can be

used to distinguish between homographs. For example:

- Re-dress (to

dress again) - Redress (to

remedy or set right)

Combining Adverbs and Adjectives

Hyphens can be used to combine an adverb and adjective to describe

a noun. In this situation, the adverb is describing the adjective, and the

adjective is describing the noun. However, when the adverb ends with -ly, a hyphen should not be used.

- Disease-causing

nutrition - Beautiful-looking

flowers - A well-meaning

gesture

It is not always necessary to use a hyphenated word. Sentences can be rearranged to avoid the need for a hyphen. If the adverb

and adjective come after the noun being described, a hyphen is not needed. For

example:

- A light-blue

handbag sat on the bench. - The handbag was

light blue.

Remember that using hyphens to combine adverbs and adjectives in

this way creates a new word. The placement of hyphens can greatly change the

meaning of a word, thus changing the entire sentence. Let’s look at some

examples of how removing a hyphen changes the meaning.

- Disease-causing poor nutrition. (Poor nutrition that causes disease.)

- Disease causing poor nutrition. (A

disease that causes poor nutrition.) - Little-celebrated paintings (Paintings that are underappreciated.)

- Little celebrated paintings (Small,

appreciated paintings.) - Government-monitoring program (A

program that monitors the government.) - Government monitoring program (A

program the government monitors.)

Using hyphens correctly is important

to clarifying these phrases.

5.4.2: Em Dashes and En Dashes

Dashes are often used to mark interruptions within sentences and show relationships between words.

Learning Objective

Use em dashes and en dashes correctly in your writing

Key Points

- Dashes are commonly used to indicate an unexpected or emphatic pause, but they serve other specific functions as well.

- Dashes are often used to mark interruptions within sentences, illustrate relationships between words, and demarcate value ranges.

- There are two kinds of dashes: em dashes (—) and shorter en dashes (–).

- Dashes should not be confused with hyphens (-).

Dashes

There are two

kinds of dashes: em dashes (—) and shorter en dashes

(–).

The Em Dash

Em dashes are often used to mark interruptions within sentences. They can be used with or without spacing.

For example:

Three unlikely companions—a canary, an eagle, and a parrot—flew by my window in an odd flock. (Chicago Style)

Three unlikely companions — a canary, an eagle and a parrot — flew by my window in an odd flock. (AP Style)

Em dashes are also used to

indicate that a sentence is unfinished because the speaker has been

interrupted. Similarly, they can be used in place of an ellipsis to illustrate an

instance where a sentence is stopped short because the speaker is too emotional

to continue.

For example:

- “Hey,” said Paul,

“where do you think—” - “I never understood why you—” Cesar trailed off.

Em dashes are sometimes

used to summarize or define prior information in a sentence.

For example:

-

When he saw his brother—his

long-lost brother who disappeared six years prior—he broke down in tears. (Chicago Style) -

Today is St. Patrick’s Day — a day

for family. (AP Style)

The En Dash

En dashes are used

to demonstrate definite ranges of values. In these cases, there should not be

any spaces around the en dash.

For example:

-

June–July 1967

-

1:00–2:00 p.m.

-

For ages 3–5

-

pp. 38–55

-

President Jimmy Carter (1977–1981)

The en dash can also be

used to contrast values, or illustrate a relationship between two things. There are no spaces around the en dashes in these instances.

For

example:

-

Radical–Unionist coalition

-

New York–London flight

-

Mother–daughter relationship

-

The Supreme Court voted 5–4 to

uphold the decision -

The McCain–Feingold bill

An exception to the use of

en dashes is made, however, when combined with an already hyphenated compound.

In these cases, using an en dash is distracting. Use a hyphen instead.

For

example:

- Non-English-speaking air traffic controllers

- Semi-labor-intensive industries

When he saw his brother—his long-lost brother who disappeared six years prior—he broke down in tears.

The title contains an example of em dash usage, which, in this case, shows a break in the sentence.

5.5: Other Punctuation

5.5.1: Parentheses

Parentheses can be used to interject remarks or other information into a sentence.

Learning Objective

List the uses of parentheses

Key Points

- Parentheses can be used to set off supplementary, interjected, explanatory or illustrative remarks.

- The words placed inside the parentheses are not necessary to understanding or completing the sentence.

- Square brackets are mainly used to enclose explanatory or missing material, which is usually added by someone other than the original author.

- Parentheses are sometimes used to enclose numbers within a sentence.

Key Term

- parentheses

-

Punctuation marks used in matched pairs to set apart or interject additional text into a sentence.

Example

Parentheses

Parentheses can be used to

set off supplementary, interjected, explanatory, or illustrative remarks. They are tall punctuation marks “()” used in matched pairs within text, to set apart or interject other text.

The words placed inside the parentheses are not necessary to understanding or completing the sentence. The words within the parentheses could be removed and a complete sentence would still exists.

Parentheses may also be nested (usually with one set (such as this) inside another set). This is not common in formal writing (though sometimes other brackets [especially square brackets] will be used for one or more inner set of parentheses [in other words, secondary {or even tertiary} phrases can be found within the main parenthetical sentence]).

There are many ways to use parentheses.

Interrupted Sentence

- Jimmy (who we all know is

smart) said we should keep searching. - Be sure to call me

(extension 2104) when you get this message. - Copyright affects how much

regulation is enforced (Lessig 2004). - Sen. John McCain (R.,

Arizona) ran for president in 2008.

Any punctuation inside

parentheses or other brackets is independent of the rest of the text. When

several sentences of supplemental material are used in parentheses, the ending punctuation is placed within the parentheses. For example:

- Mrs. Pennyfarthing (What?

Yes, that was her name!) was my landlady.

Enumeration

Parentheses are sometimes used to enclose numbers within a sentence. The purpose of using numbers within parentheses is to highlight multiple points in one sentence.

- All applicants must submit (1) a cover letter, (2) a resume, (3) a list of references, (4) an essay, and (5) letters of recommendation.

The numbers within parentheses highlight the items applicants need to include. They are intended to add clarity to the sentence.

Square Brackets

Square

brackets are mainly used to enclose explanatory or missing material, which is

usually added by someone other than the original author. This is especially

prevalent in quoted text. For example:

“I appreciate it [i.e., the

honor], but I must refuse. “

“The future of

psionics [i.e., mental powers that affect physical matter] is in doubt.”

Modifying Quotations

Square brackets may also

be used to modify quotations. For example, if referring to someone’s statement

“I hate to do laundry,” one could write: He “hate[s] to do

laundry.”

The bracketed expression

“[sic]” is used after a quote or reprinted text to indicate the

passage appears exactly as in the original source; a bracketed ellipsis

“[…]” is often used to indicate deleted material; bracketed

comments indicate when original text has been modified for clarity. For

example:

- “I’d like to thank

[several unimportant people] and my parentals [sic] for their love, tolerance

[…] and assistance [emphasis added].”

5.5.2: Ending Punctuation

Ending punctuation identifies the end of a sentence, and most commonly includes periods, question marks, and exclamation marks.

Learning Objective

Identify the correct punctuation to end a given sentence

Key Points

- Ending punctuation comprises symbols that indicate the end of a sentence, such as periods, question marks, and exclamation points.

- Periods are used at the end of declarative or imperative sentences.

- Question marks come at the end of sentences that make a request or ask a direct question. Declarative sentences sometimes contain direct questions.

- A sentence ending in an exclamation mark may be an exclamation, an imperative, or may indicate astonishment.

Key Terms

- exclamation mark

-

A punctuation mark usually used after an interjection or exclamation to indicate strong feelings or high volume (shouting).

- question mark

-

Punctuation at the end of a sentence that asks a direct question.

- period

-

The punctuation mark that indicates the end of a sentence.

Ending punctuation comprises symbols that indicate the end of a sentence. Most commonly, these are periods,

question marks, and exclamation points. Ending punctuation can also be referred to

as end marks, stops, or terminal punctuation.

There are three main types

of ending punctuation: the period, the question mark, and the exclamation mark.

A period (.) is the punctuation mark that indicates the end of a sentence.

The question mark (?) replaces a period at the end of a sentence that asks

a direct question. The exclamation mark (!) is a punctuation mark usually used

after an interjection or exclamation to indicate strong feelings or high volume

(shouting), and often marks the end of a sentence.

Period

Periods are used at the

end of declarative or imperative sentences. Recall that declarative sentences

make statements and imperative sentences give commands. Periods can also be

used at the end of an indirect question. Indirect questions are designed to ask

for information without actually asking a question. Let’s review some examples.

- My

dog is a golden retriever. (declarative sentence) - Go

get your dog and bring him inside the house. (imperative sentence) - Janet’s

mom and dad want to know what she is doing. (indirect question) - “Get

some paper towels,” she ordered. (declarative sentence containing an imperative

statement)

Periods are also used in

abbreviations. For example, “doctor” is abbreviated “Dr.” and “junior” is abbreviated “Jr.” Remember that if an abbreviation that uses a period comes at the end of a

sentence you do not add a period—the period with the abbreviation

serves as the ending punctuation as well.

Question Mark

Question marks come at the

end of sentences that make a request or ask a direct question. Declarative

sentences sometimes contain direct questions.

- What

is Janet doing? (direct question) - Her

mother asked, “What are you doing, Janet?” (declarative sentence with a direct

question)

Exclamation Mark

A sentence ending in an

exclamation mark may be an exclamation, an imperative, or may indicate

astonishment. Like question marks, exclamation marks can be included within

declarative sentences. Let’s review some examples.

- Wow!

(exclamation) - Boo!

(exclamation) - Stop!

(imperative) - They

were the footprints of a gigantic duck! (astonishment) - He

yelled, “Stay off the grass!” (declarative sentence that includes an exclamation)

Exclamation marks are

occasionally placed mid-sentence with a function similar to a comma, for

dramatic effect, although this usage is obsolescent: “On the walk, oh!

there was a frightful noise.”

Informally, exclamation

marks may be repeated for additional emphasis (“That’s great!!!”),

but this practice is generally considered unacceptable in formal prose. The

exclamation mark is sometimes used in conjunction with the question mark. This

can be in protest or astonishment (“Out of all places, the squatter-camp?!”);

again, this is informal. Overly frequent use of the exclamation mark is

generally considered poor style, for it distracts the reader and devalues the

mark’s significance.

Cut out all those exclamation points.

The famous author F. Scott Fitzgerald was not a fan of exclamation points; in his words: “Cut out all those exclamation points. An exclamation point is like laughing at your own jokes.”

5.6: General Mechanics

5.6.1: Common Spelling Errors

It is important to be familiar with common spelling errors to avoid them in your own writing.

Learning Objective

Recognize common spelling errors

Key Points

- It is important to be familiar with spelling errors that writers frequently make so you can avoid them in your own writing.

- Knowing why these mistakes occur will help you write with better awareness.

- Word-processing programs usually have a spell-checker, but you should still carefully check for correct changes in your words. This is because automatic spell-checkers may not always understand the context of a word.

Key Terms

- phonetics

-

The study of the physical sounds of human speech (phones) and the processes of their physiological production, auditory reception, and neurophysiological perception, as well as their representation by written symbols.

- typo

-

A spelling error.

- homophone

-

A word which is pronounced the same as another word but differs in spelling or meaning or origin, for example: carat, caret, carrot, and karat.

The Importance of Spelling

Misspelling a word might seem like a minor mistake, but it can reflect very poorly on a writer. It

suggests one of two things: either the writer does not care enough about his

work to proofread it, or he does not know his topic well enough to properly spell words

related to it. Either way, spelling errors will make a reader less

likely to trust a writer’s authority.

The

best way to ensure that a paper has no spelling errors is to look for them

during the proofreading stage of the writing process. Being familiar with the

most common errors will help you find (and fix) them during the writing

and proofreading stage.

Sometimes,

a writer just doesn’t know how to spell the word she wants to use. This

may be because the word is technical jargon or comes from a language other than

her own. Other times, it may be a proper name that she has not

encountered before. Anytime you want to use a word but are unsure of how to

spell it, do not guess. Instead, check a dictionary or other reference work

to find its proper spelling.

Common Spelling Errors

Phonetic Errors

Phonetics is a field that studies the sounds of a language. However, English phonetics can be tricky: In English, the pronunciation of a word does not always relate to the way it is spelled. This can make spelling a challenge. Here are some common phonetic irregularities:

- A word can sound

like it could be spelled multiple ways. For example: “concede” and

“conceed” are the same phonetically, but only “concede” is

the proper spelling. - A word has silent

letters that the writer may forget to include. You cannot hear the

“a” in “realize,” but you need it to spell the word

correctly. - A word has double

letters that the writer may forget to include. “Accommodate,” for

example, is frequently misspelled as “acommodate” or

“accomodate.” - The writer may

use double letters when they are not needed. The word “amend” has

only one “m,” but it is commonly misspelled with two.

Sometimes,

words just aren’t spelled the way they sound. “Right,” for example,

does not resemble its phonetic spelling whatsoever. Try to become familiar with

words that have unusual or non-phonetic spellings so you can be on the lookout

for them in your writing. But again, the best way to avoid these misspellings

is to consult a dictionary whenever you’re unsure of the correct spelling.

Homophones

“Bread”

and “bred” sound the same, but they are spelled differently, and they mean

completely different things. Two words with different meanings but the same

pronunciation are homophones. If you don’t know which homophone is the right

one to use, look both up in the dictionary to see which meaning (and spelling)

you want. Common homophones include:

- right, rite,

wright, and write - read (most tenses

of the verb) and reed - read (past, past

participle) and red - rose (flower) and

rose (past tense of rise) - carat, caret, and

carrot - to, two, and too

- there, their, and

they’re - its and it’s

Typographical Errors

Some spelling errors are caused by the writer accidentally typing the wrong thing.

Common typos include:

- Omitting letters

from a word (typing “brthday” instead of “birthday,” for

example) - Adding extra

letters (typing “birthdayy”) - Transposing two

letters in a word (typing “brithday”) - Spacing words

improperly (such as “myb irthday” instead of “my birthday”)

Being aware of these

common mistakes when writing will help you avoid spelling errors.

5.6.2: Capital Letters

Capital letters are used to make certain words stand out.

Learning Objective

Identify words that must be capitalized

Key Points

- Three situations in which a capital letter should always be used are at the start of sentences, proper nouns, and for the pronoun “I.”

- Names and nicknames, languages, geographical names, religions, days of the week, months, holidays, and some organizations are considered proper nouns.

- In titled works (such as books, articles, or artwork) the majority of the words are capitalized.

Key Terms

- capitalization

-

Writing a word with its first letter as a capital letter (upper-case letter) and the remaining letters in lower case.

- proper noun

-

A word denoting a particular person, place, organization, ship, animal, event, idea, or other individual entity.

Capital letters identify

proper names, people and their languages, geographical names, and certain government

agencies. Different style manuals have different rules for capitalization, so it’s important to have a style guide on hand while you write in case you have a question about capitalization. There are manuals for MLA, APA, Chicago/Turabian, and other styles.

However, there are general rules for capitalization which apply to all writing.

Starting a Sentence

Always capitalize the very first word of a sentence, no matter what it is.

- Experienced cooks usually

enjoy experimenting with food.

The Pronoun “I”

Always capitalize the first-person singular pronoun “I.”

- Sometimes, I wish I could

cook with them.

Quoting Others

Directly quoted speech is capitalized if it is a full sentence.

- The head chef said to me, “Anyone

can become a good cook if they are willing to learn.”

Proper Nouns

Names or nicknames,

people, languages, geographical names, religions, days of the

week, months, holidays, and some organizations are considered proper nouns.

Proper nouns should always be capitalized.

Names and Nicknames

A name or nickname should

always be capitalized. This includes brand names.

- John Paul II

- Cindy Parker

- Buffalo Bill

- Pepsi

- Nike

- Scotch tape

People and Languages

Names referring to a

person’s culture should be capitalized. Languages are also capitalized.

- African Americans

- Caucasian

- Eskimos

- French

- English

- Japanese

Geographical Names

The names of cities,

states, countries, continents, and other specific geographic locations are capitalized.

- Arctic Circle

- China

- New York

- Europe

Organizations

Government agencies,

institutions, and companies capitalize their names.

- Ford Motor Company

- International Red Cross

- Internal Revenue Service

- University of South

Carolina

Days, Months, and Holidays

Days of the week, months,

and holidays are always capitalized. However, seasons (fall, spring, summer,

and winter) are not capitalized.

- Tuesday

- October

- Independence Day

Religions

Religions and their

adherents, holy books, holy days, and words referencing religious figures are

capitalized.

- Christianity and Christian

- Hinduism and Hindu

- Islam and Muslim

- Judaism and Jew

- Bible, Koran, Talmud, Book

of Mormon - Easter, Ramadan, Yom

Kippur - God, Allah, Buddha

Titled Work

In titled works (such as

books, articles, or artwork) the majority of the words are capitalized. A few

exceptions are a, an, the, and, but, or, nor, for, so, and yet. These words are

only capitalized if they come at the beginning of the title. This can vary

based on style, so be sure to check your manual for specifics.

- The Scarlet Letter

- From Here to Eternity

- Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

- Girl with a Pearl Earring

5.6.3: Abbreviations and Acronyms

An abbreviation is the shortened form of a word or phrase.

Learning Objective

Use abbreviations appropriately in an academic context

Key Points

- There are rules that explain how a writer may shorten a long word or phrase into an abbreviation or acronym.

- Following abbreviation and acronym rules ensures that the reader always understands what these abbreviations mean.

- Phrases like “lol” or “brb” are considered inappropriate for formal papers.

Key Terms

- acronym

-

Abbreviations formed from the initial components in a phrase or a word. These components may be individual letters (as in CEO) or parts of words (as in Benelux and Ameslan).

- abbreviation

-

A shortened form of a word or phrase, used to represent the whole.

Abbreviations

An abbreviation is the

shortened form of a word or phrase. Most abbreviations are formed from a letter

or group of letters taken from the original word. In an academic paper, abbreviations are rarely used to stand in for major concepts or terms. Instead, they are

usually shortened forms of commonly used but relatively minor words, such as

“km” for “kilometer” or “Dr.” for “doctor.”

Most are common enough that a writer does not need to provide the reader with

an expanded definition. If an abbreviation is not particularly well-known,

consider whether you should use it or use the longer (but easier to understand)

word.

Style Conventions for Abbreviations

Style guides may differ

somewhat on how to punctuate abbreviations. Listed below are the most common

guidelines, which cover most of the scenarios for using abbreviations. However,

this is not a completely comprehensive list. If told to use a specific style

manual, such as MLA or Turabian, be sure to check what it says about specific

usage rules. And whatever style you decide to use, remember to be consistent

with how you use and punctuate abbreviations.

Abbreviations should be

capitalized just like their expanded forms would be. If the original word or

phrase is capitalized, then you should capitalize the abbreviation. If the

original is lower case, then the abbreviation should be too. Abbreviations

usually end with a period, particularly if they were formed by dropping the end

of a word (the major exception being the use of acronyms). When a sentence ends

with an abbreviation, use only one period for both the abbreviation and the

sentence.

- She lives in N.Y.

(New York is abbreviated as “N.Y.” In this example, it comes at the end of the

sentence but there is only one period.) - He got a ticket for going 70 mph when the speed limit was 55. (Miles

per hour is abbreviated “mph.” Note that it is not capitalized.) - The CIA is depicted in many action movies as highly secretive. (CIA

is always capitalized because Central Intelligence Agency is always

capitalized.)

Acronyms

Acronyms are abbreviations

that form another word. Laser is so frequently used as a word that

few people know it is an acronym. Laser stands for “light amplification by stimulated

emission of radiation.” Scuba is also an acronym standing for “self-contained underwater breathing apparatus.” Although

this was the foundation for acronyms, they do not always form another word.

More often than not, acronyms are formed from the initial components of a

series of words. These components are usually individual letters, but some may

use the first syllables of words. The main purpose of acronyms is to act as

shorthand for longer terms, particularly those a writer wants to reference

frequently. In the right circumstances, acronyms can make these terms more

manageable for the writer to use and for the reader to understand.

Using Acronyms in Academic Writing

While acronyms can be very

useful, only some of them are considered appropriate for use in scholarly

writing. In general, acronyms can be used to stand in for job titles (such as

CEO), statistical categories (such as RBI) or the names of companies and

organizations (such as FBI). Other instances may arise depending on the type of

paper you are writing—a scientific essay, for example, might have acronyms

for the names of chemical compounds or scientific terms. In most cases, you

will be able to judge whether or not an acronym is appropriate based on the

context of what you are writing. The only category of acronym that you should

never use is slang, especially terms derived from texting. Phrases like

“lol” and “brb” may be fine in casual conversation, but

would make a writer seem unprofessional in a serious paper. For all acronyms

you choose to use, making sure that the reader knows what they mean is

essential. The first time you use any acronym, make sure to use its expanded

form first. For example:

- Johnathan

recently joined the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP). - Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) is known

for fighting for the National Minimum Drinking Age Act. - The Family Research Council (FRC) was founded

in 1981.

Once the abbreviation has been identified, as

shown in these examples, you can use the abbreviated version in the rest of your

document.

Style Conventions for Acronyms

Most acronyms are written

in all-uppercase with no punctuation between letters. This differs from

abbreviations, which are normally written with periods in order to note the

deleted parts of words. A small number of acronyms use slashes to show an ellipsis, as in “w/o” for “without.” Spaces are not used

between the different letters of acronyms. Apostrophes are generally not used

to pluralize abbreviations. They are, however, used to form possessives.

5.6.4: Numbers

Sometimes it is appropriate to write numbers as numerals; other times they should be spelled out.

Learning Objective

List the rules for using numbers in different kinds of writing

Key Points

- In academic writing, numbers that can be expressed in one or two words should be spelled out.

- Numbers that are more than two words long should be written as numerals.

- The proper usage of numbers in technical writing varies considerably.

Key Term

- numeral

-

A symbol that is not a word and represents a number, such as the Arabic numerals 1, 2, 3 and the Roman numerals I, V, X, L.

Style rules for inserting numbers into text vary considerably. Whether numbers should be written out (e.g. two, two hundred) or written as numerals (e.g. 2, 200) depends on what kind of writing is being done.

Numbers as Words

In strictly academic writing, numbers of one or two words should be spelled out with letters. For example:

- Anthony was able to bike five miles in less than an hour.

Notice that 5 is written out as “five” because it is one word.

- Maria bought five bananas, two bunches of grapes, and six oranges for her fruit salad. She needed twenty-one servings for the luncheon.

Notice that each number is written out, including 21, because all of them are one or two words.

Numbers as Numerals

Numbers that are more than two words long should be written as numerals. For example: “Our vacation to North Carolina ended up being 728 miles, as a round trip.” Or, in the case of years: “Tony was born in the fall of 1966.”

Also, the following numbers are written as numerals:

- Dates: December 7, 1941, 32 BC, AD 1066

- Addresses: 119 Lakewood Lane, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue

- Percentages: 45 percent or 45%

- Fractions and decimals: 1/3 and 0.25

- Scores: 20 to 13 or 15–18

- Statistics: average age 25

- Surveys: 2 out of 5

- Exact amounts of money: $861.34 or $0.67

- Divisions of books: volume 6 or chapter 5

- Divisions of plays: act 2, scene 4

- Time of day: 12:00 AM or 4:35 PM

Technical Writing

In technical writing (i.e., research writing or other writing that includes measurements or statistics), the proper usage of numbers varies substantially. Typical rules to follow in technical writing include:

- Technical quantities of any amount are expressed in numerals (3 feet, 12 grams, et cetera).

- Nontechnical quantities of fewer than 10 are expressed in words (three people, six whales).

- Nontechnical quantities of 10 or more are expressed in numerals (300 people, 12 whales).

- Approximations are written out as letters (approximately ten thousand people).

- Decimals are expressed in numerals (3.14).

- Decimals of less than one are usually preceded by zero (0.146); however, this may vary depending on the style you are asked to write in.

- Fractions are written out, unless they are linked to technical units (two-thirds of the members, 3 1/2 hp).

- Page numbers and the titles of figures and tables are expressed in numerals.

- Back-to-back numbers are written using both words and numerals (six 3-inch screws).

Special Cases

There are many special cases for writing numbers. A number at the beginning of a sentence should be spelled out as words. Within a sentence, the same unit of measurement should be expressed consistently in either numerals or words. In general, months should not be expressed in terms of numbers.

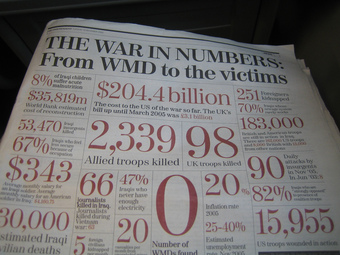

Numbers in the news

When numbers are used in text, many basic formatting rules apply.

5.6.5: Italics

Writers use italics to emphasise certain words such as titles, scientific words, and foreign words.

Learning Objective

Identify situations in which italics should be used

Key Points

- Italics are a typeface feature designed to make words stand out. There are general rules to using italics properly.

- Titles of textbooks, fiction or nonfiction books, newspapers, magazines, academic journals, films, epic poems, plays, operas, musical albums, television shows, movies, works of art, and the names of legal cases should all be italicized.

- Italics can also be used to emphasize certain words.

- Italics should always be used with scientific terms, algebraic equations, and foreign-language words.

Key Term

- italics

-

A typeface style that is used to add emphasis to words.

Italics are letters that slant slightly to the right. When using a word processor (like Microsoft Word) italicized words generally look like this:

This sentence is in italics.

Italics should be used consistently in your writing. In general, italics are used to identify the title of a major publication (such as a book, newspaper, or magazine), for emphasis, for scientific or technical words, and for foreign words.

Titles

The titles of major literary works should be italicized. This includes textbooks, fiction or nonfiction books, newspapers, magazines, academic journals, films, epic poems, plays, operas, musical albums, television shows, movies, works of art, and the names of legal cases.

- My favorite book is July’s People by Nadine Gordimer.

- I read The New York Times to keep up with the political debates.

- I have every Taylor Swift album except Today Was a Fairytale.

- The 1976 version of the movie Carrie was much scarier than the newer version.

- Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey are my two favorite epic poems.

- The Scream by Edvard Munch is a well-known painting.

Keep in mind that smaller published works, such as an individual article from a newspaper/magazine/journal, or a single poem, should be set in quotation marks. For example:

- The magazine Southern Living published an interesting article on traveling in the U.S. called “The South’s Best Roadside Attractions” in the November, 2015 edition.

Emphasis

When you need to emphasize

a word you can use italics to make it stand out. Sometimes, emphasizing certain words gives the sentence a sarcastic tone. It

can also emphasize a fact as true. Let’s review some examples.

- She

only wants to make 100% on every test. -

If

they are offended, then that’s their

problem. - These

are the files we need.

Scientific or Technical Terms

Italics are often used in

scientific and mathematical writing. Algebraic equations are usually

italicized. The scientific (Latin) names of species are also italicized. Here are

some examples.

- Slope

is found by calculating y=mx+b. - Several

more Homo sapiens fossils were discovered

recently. - The

scientific name for the house sparrow is Passer

domesticus.

Foreign Languages

Words in foreign languages should also be italicized. Here are a couple of

examples.

- In an interview, Julia Alvarez once said, “What I can’t push