3.1: Understanding the Academic Context of Your Topic

3.1.1: Understanding the Academic Context of Your Topic

Good arguments convince a reader to reconsider previously accepted knowledge or opinions about a topic, also known as the status quo.

Learning Objective

Explain the importance of including a discussion of the status quo in a paper

Key Points

- In writing, “status quo” refers to how earlier scholars have approached an issue.

- In the earlier part of a paper, the writer must explain to the reader the status quo about a subject in order for the reader to understand the stakes of changing the argument.

- The status quo is also common ground between a writer and a reader.

Key Term

- status quo

-

A Latin term meaning the current or existing state of affairs; literally, “the state in which.”

What Is the Status Quo?

“Status quo” refers to the existing and accepted body of academic research and discourse on a given topic. Conducting the appropriate research on this discourse is an important preliminary step to academic essay writing.

Academic papers rely on the status quo to inform and support the writer’s argument. One of the main principles of academic writing is active and creative interpretation of research and arguments that have come before.

Finding the Status Quo

Within the context of academic writing, “status quo” refers primarily to scholarly findings — that is, what other academic experts have published around a particular subject. Prior to writing an academic paper, the writer must investigate and study scholars’ arguments thoroughly and critically. This helps the writer understand how scholars’ arguments fit into the wider context of the paper, and it applies even in cases where the majority of research will be used for knowledge rather than citation purposes.

Examining the status quo

Before you begin writing on any topic, it is important to understand the dominant conversation, or the status quo, associated with the topic. Examining the status quo is a good way of figuring out where to situate your specific insight on a topic.

As the writer continues her research, she will eventually find sources to incorporate into the paper. During the writing process, it can be helpful to form questions focused on a specific work or idea to help set up the paper’s hypothesis. Because the status quo is crucial to the writer’s argument, it is usually included in the paper’s introduction.

Why Does the Status Quo Matter?

Identifying the status quo in the introduction serves several purposes. First, it helps readers immediately understand the context of the argument. When readers are informed about the sources used to support the argument, they can gain a better understanding of it. Second, identifying the status quo also tells readers why the writer’s angle is unique compared to past research.

Accurately summarizing the status quo also demonstrates that the writer has enough knowledge and expertise within the field to confidently make an argument. Audiences have a difficult time trusting a writer who fails to describe or prove that he or she is familiar with the status quo.

Contributing to the Status Quo

The status quo is not fixed and is constantly evolving and growing because new writing adds to and changes it. Whenever a writer puts forth a new argument, draws a new conclusion, or makes new connections, the status quo changes, even if only slightly. As a researcher and writer, you also have the potential to change the status quo through your research and argument.

3.2: Organizing Your Research Plan

3.2.1: Organizing Your Research Plan

To save time and effort, decide on a research plan before you begin.

Learning Objective

Outline the steps of the research process

Key Points

- Your research plan will specify the kinds of sources you want to gather. These may include scholarly publications, journal articles, primary sources, textbooks, encyclopedias, and more. Most search engines will let you filter search results by type of source.

- You can limit your sources by date and time period when planning your research. You can use search engines to find only articles written within a specific time frame to ensure your findings are relevant. You can apply filters such as “written in the past 10 years” to narrow your search results.

Key Term

- research

-

Pursuit of information, such as facts, principles, theories, applications, etc.

A research paper is an expanded essay that relies on existing discourse to analyze a perspective or construct an argument. Because a research paper includes an extensive information-gathering process in addition to the writing process, it is important to develop a research plan to ensure your final paper will accomplish its goals. As a researcher, you have countless resources at your disposal, and it can be difficult to sift through each source while looking for specific information. If you begin researching without a plan, you could find yourself wasting hours reading sources that will be of little or no help to your paper. To save time and effort, decide on a research plan before you begin.

Books, books, books …

Do not start research haphazardly—come up with a plan first.

Creating a Research Plan

A research plan should begin after you can clearly identify the focus of your argument. Narrow the scope of your argument by identifying the specific subtopic you will research. A broad search will yield thousands of sources, which makes it very difficult to form a focused, coherent argument. It is simply not possible to include every topic in your research. If you narrow your focus, however, you can find targeted resources that can be synthesized into a new argument.

After narrowing your focus, think about key search terms that will apply only to your subtopic. Develop specific questions that can be answered through your research process, but be careful not to choose a focus that is overly narrow. You should aim for a question that will limit search results to sources that relate to your topic, but will still result in a varied pool of sources to explore.

If you are studying the Battle of Gettysburg, for example, you might decide to look into any number of topics related to the battle: medical practices on the field, social differences between soldiers, or military maneuvers. If your topic is medical practices in battle, an search for “Battle of Gettysburg” would return far too many general results. You would also not want to search for a single instance of surgery, because you might not be able to find enough information on it. Find a happy medium between very broad and too specific.

Another part of your research plan should include the type of sources you want to gather. The possibilities include articles, scholarly journals, primary sources, textbooks, encyclopedias, and more. Most search engines will let you limit search results by type of source. If you know that you are only looking for articles, you can exclude things like interviews or abstracts from your search. If you are looking for specific kinds of data, like images or graphs, you might want to find a database dedicated to that sort of source.

You can also limit the time period from which you will draw resources. Do you only want articles written in the past ten or twenty years? Do you want them from a specific span of time? Again, most search engines will allow you to limit results to anything written within the years you specify, and the choice to limit the time period will depend on your topic. Determining these factors will help you form a specific research plan to guide your process.

Example of a Research Process

A good research process should go through these steps:

- Decide on the topic.

- Narrow the topic in order to narrow search parameters.

- Create a question that your research will address.

- Generate sub-questions from your main question.

- Determine what kind of sources are best for your argument.

- Create a bibliography as you gather and reference sources.

For example, in step one, you might decide that your topic will be 19th-century literature. Then in step two you may narrow it down to 19th-century British science fiction, and then narrow it down even further to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

Then, in step three, you would come up with a research question. A good research question for this example might be, “How does the novel’s vision of generative life relate to the scientific theories of life that were developed in the 19th century?” Posing a historical question opens up research to more reference possibilities.

Next, in step four, you generate sub-questions from your main question. For instance, “During the 19th century, what were some of the competing theories about how life is created?,” and “Did any of Mary Shelley’s other works relate to the creation of life?” After you know what sub-questions you want to pursue, you’ll be able to move to step five—determine what kind of sources are best for your argument. Our example would lead us to possibly look at newspapers or magazines printed in the late 18th or early 19th century. In addition, books or essays on the topic, both contemporary and older, could be sources. It is likely that someone has researched your topic before, and even possibly a question similar to yours. Books written since your time period on your specific topic could be a great source for further references. When you find a book that is written about your topic, check the bibliography for references that you can try to find yourself.

As you accumulate sources, make sure you create a bibliography, or a list of sources that you’ve used in your research and writing process. And finally, have fun doing the research!

3.3: Finding Your Sources

3.3.1: The Importance of Reliability

Using reliable sources in research papers strengthens your own voice and argument.

Learning Objective

Recognize sources that may be biased

Key Points

- While researching for sources relevant to your topic, you need to critically read a source to identify possible political or other forms of bias, to consider the effects of historical context, and to discover possible bias on the part of the author.

- The age of a source is another factor to consider, the importance of which will differ depending on the topic.

- Consider the possible biases of the author.

- Websites, unlike books, do not necessarily have publishers. Therefore, you should be attentive to who is behind the websites you find.

Key Terms

- research

-

Diligent inquiry or examination to seek or revise facts, principles, theories, applications, et cetera; laborious or continued search after truth.

- source

-

The person, place or thing from which something (information, goods, etc. ) comes or is acquired.

Example

- If you’re working on an essay about current developments in end-of-life care for terminally ill patients, an outdated source, such as a 1997 Detroit Free Press article about Jack Kevorkian, will likely not be relevant for your discussion, except as part of a historical overview of the politics of physician aid-in-dying. Nor would the Wikipedia entry for “euthanasia” be an appropriate place to look for information, since, while it can be useful for collecting colloquial information, Wikipedia is certainly not a scholarly source. Various religious or other non-medical interest-group sources could likely crop up in your search, but in those cases you’d need to take special care to identify potential biases and consider their impact on the information you find.

Using sources in research papers strengthens your own voice and argument, but to do so effectively you must understand your sources and vet their reliability.

When researching, it is important to determine the position and the reliability of every source/author. This will ensure that your source is both credible and relevant, and that the source will enhance your paper rather than undermine it. The following are a few recommendations to approach sources in whatever form they take.

How Old Is the Source?

The guidelines for assessing the usability of print sources and digital sources (i.e., sources accessed through the Internet) are similar. One point to keep in mind for both digital and print sources is age: How old is the source? Examining the source’s age helps you determine whether the information is relevant to your paper topic. Depending on your topic, different degrees of age will be appropriate. For example,

if you are writing on 17th-century British poetry, it is not enough to simply find sources from the era, nor is adequate to reference only early 20th-century scholarly sources. Instead, it will be helpful to combine the older, primary sources with more recent, secondary scholarship. Doing so will make a convincing case for your particular argument. If you are researching public-health theories, however, your argument will depend on more modern scholarly sources. Older articles may include beliefs or facts that are outdated or have been proven wrong by more contemporary research.

With digital sources, be wary of sites with old, outdated information. The point is to avoid presenting inaccurate or outdated information that will negatively impact your paper.

Author Biases

Author bias is another consideration in choosing a source. “Author bias” means that the author feels strongly about the topic one way or another, which prevents the author from taking a neutral approach to presenting findings. For print sources, you can assess bias by considering the publisher of the book. Books published by a university press undergo significant editing and review to increase their validity and accuracy. Be cautious about self-published books or books published by specific organizations like corporations or nonprofit groups. Unlike university presses, these sources may have different guidelines and could be putting out information that is intentionally misleading or uninformed. Similarly, periodicals like scholarly journals or magazines may also have bias. However, scholarly journals tend to be peer-reviewed and contain citations of sources, whereas a magazine article may contain information without providing any sources to substantiate purported claims.

While you want to support your argument with your research, you don’t want to do so at the expense of accuracy or validity.

Online Resources

Websites, unlike books, do not necessarily have publishers. Instead, you should consider who is behind the websites you find. To avoid using information that comes from an unreliable source, stick to scholarly databases. While you can find some articles with general search engines, a search engine will only find non-scholarly articles. If you use broader Internet searches, look closely at domain names. Domain names can tell you who sponsors the site and the purpose of that sponsorship. Some examples include educational (.edu), commercial (.com), nonprofit (.org), military (.mil), or network (.net).

Depending on your topic, you may want to avoid dot-com websites because their primary purpose tends to be commerce, which can significantly affect the content that they publish. Additionally, consider the purpose that the website serves. Is any contact information provided for the website’s author? Does the website provide references to support the claims that it makes? If the answers to these types of questions are not readily available, it may be best to look in other places for a reliable source.

There are increasing numbers of non-scholarly sites that pertain to particular topics, but are not scholarly sources. Blogs, for example, may cater to a particular topic or niche, but they are typically created and managed by an individual or party with an interest in promoting the content of the blog. Some blog writers may have valid credentials, but because their writing is not peer-reviewed or held to an academic standard, sites such as these are typically unreliable sources.

Remember, when researching, the goal is not only to gather sources, but to gather reliable resources. To do this, you should be able to not only track the claims contained within a source, but also consider the stakes that may be involved for the author making those claims. While personal motivation may not always be accessible in a document, in some cases there can be contextual clues, like the type of publisher or sponsor. These may lead you to decide that one source is more reliable than another.

Money and magnifying glass

When you evaluate scholarly sources, look out for potential conflicts of interest and hidden agendas. For example, the sources of funding for research are very important, as they may influence the writers’ interpretation of results.

3.3.2: Scholarly Sources

In academic writing, the sources you use must be reliable; therefore, you should rely mainly on scholarly sources as the foundation for your research.

Learning Objective

List the different types of scholarly sources available to researchers

Key Points

- Not all sources are equal. One way to find reputable scholarly sources is to avoid using general search engines such as Google or Wikipedia.

- Use academic search databases like JStor, EBSCO, or Academic Search Premier.

- Primary sources give the researcher a glimpse into the time period under review and provide opportunities for new analysis.

- In addition, do not hesitate to visit your library in order to ask your librarian about accessing these databases, and also in order to search for print materials.

Key Terms

- secondary source

-

Any document that draws on one or more primary sources and interprets or analyses them; also, sources such as newspapers, whose accuracy is open to question.

- primary source

-

A historical document that was created at or near the time of the events studied, by a known person, for a known purpose.

- database

-

A collection of (usually) organized information in a regular structure, usually but not necessarily in a machine-readable format accessible by a computer.

Reliability

Research is the foundation of a strong argument, theory, or analysis. When constructing your research paper, it is important to include reliable sources in your research. Without reliable sources, readers may question the validity of your argument and your paper will not achieve its purpose.

Academic research papers are typically based on scholarly sources and primary sources. Scholarly sources include a range of documents, source types, and formats, but they share an important quality: credibility. More than any other source you are likely to encounter during your research, a scholarly source is most likely to be reliable and accurate. Primary sources are documents that were written or created during the time period under study. They include letters, newspaper articles, photographs, and other artifacts that come directly from a particular time period.

Scholarly Sources

A scholarly source can be an article or book that was written by an expert in the academic field. Most are by professors or doctoral students for publication in peer-reviewed academic journals. Since the level of expertise and scrutiny is so high for these articles, they are considered to be among the best and most trustworthy sources. Most of these articles will list an author’s credentials, such as relevant degrees, other publications, or employment at a university or research institution. If an article does not, try searching for the author online to see how much expertise he or she has in the field.

You may decide to use sources that are not scholarly articles, such as interviews or newspaper articles. These sources should also be written by an expert in the field and published by a reputable source. An investigative essay in the New Yorker would be fine; an investigative essay in the National Enquirer would not.

Other types of scholarly sources include non-print media such as videos, documentaries, and radio broadcasts. Other sources may include tangible items such as artifacts, art, or architecture. It’s likely that you will find secondary sources that provide analysis of these sources, but you should also examine them to conduct your own analysis.

Primary and Secondary Sources

A primary source is an original document. Primary sources can come in many different forms. In an English paper, a primary source might be the poem, play, or novel you are studying. In a history paper, it may be a historical document such as a letter, a journal, a map, the transcription of a news broadcast, or the original results of a study conducted during the time period under review. If you conduct your own field research, such as surveys, interviews, or experiments, your results would also be considered a primary source. Primary sources are valuable because they provide the researcher with the information closest to the time period or topic at hand. They also allow the writer to conduct an original analysis of the source and to draw new conclusions.

Secondary sources, by contrast, are books and articles that analyze primary sources. They are valuable because they provide other scholars’ perspectives on primary sources. You can also analyze them to see if you agree with their conclusions or not.

Most essays will use a combination of primary and secondary sources.

Where to Find Scholarly Sources

The first step in finding good resources is to look in the right place. If you want reliable sources, avoid general search engines. Sites like Google, Yahoo, and Wikipedia may be good for general searches, but if you want something you can cite in a scholarly paper, you need to find it from a scholarly database.

Popular scholarly databases include JStor, Project Muse, the MLA International Bibliography, Academic Search Premier, and ProQuest. These databases do charge a fee to view articles, but most universities will pay for students to view the articles free of charge. Ask a librarian at your college about the databases to which they offer access.

Most journals will allow you to access electronic copies of articles if you find them through a database. This will not always be the case, however. If an article is listed in a database but can’t be downloaded to your computer, write down the citation anyway. Many libraries will have hard copies of journals, so if you know the author, date of publication, and page numbers, you can probably find a print edition of the source.

At the college or university level, you have another incredible resource at your fingertips: your college’s librarians! For help locating resources, you will find that librarians are extremely knowledgeable and may help you uncover sources you would never have found on your own—maybe your school has a microfilm collection, an extensive genealogy database, or access to another library’s catalog. You will not know unless you utilize the valuable skills available to you, so be sure to find out how to get in touch with a research librarian for support!

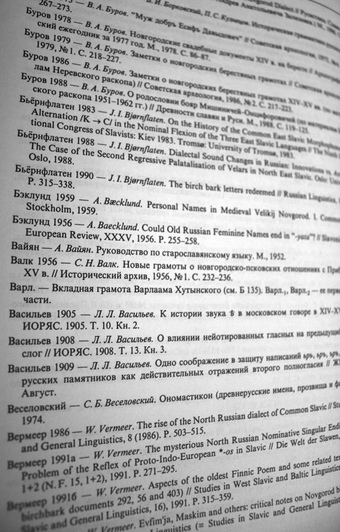

Examples of Scholarly Sources

The exact combination or sources you use in your paper will depend on the discipline in which you are conducting research and the topic of your essay. Here are some examples of the types of sources you might include in a variety of academic fields.

- Politics/Law: You could include text from the Constitution or a Supreme Court decision as a primary source, and you may include a scholarly article that discusses that decision as a secondary source.

- Science: You may include findings from a scientific research study as a primary source, and you may include an article from a medical journal as a secondary source.

- Arts/humanities: You may include a piece of artwork or writing as a primary source, and you may include a scholar’s critical analysis of that work as a secondary source.

- History: You may include correspondence between historical figures as a primary source, and you may include information from a textbook as a secondary source.

These list of examples is meant to illustrate the range of approaches you may take when determining what sources to include in your paper, but it is not an exhaustive list of the possibilities available to you! The researcher’s ability to draw connections between a variety of sources is part of the art of research-paper writing, so you must decide on the best combination of scholarly sources for your essay.

Research

Looks like he’s found a good print source—though it may be too old for us to use today.

3.3.3: Choosing Search Terms for Sources

Conducting searches related to the keywords or subheadings of your topic will help systematize your research.

Learning Objective

Identify useful search terms given a research topic

Key Points

- In the course of your research, your initial keywords may reveal other avenues that could help further your research, especially in situations where the keywords are still vague.

- You can search both online databases and actual library catalogs for sources. Catalogs and databases allow you to organize searches by subject headings and/or key terms.

- The two options for narrowing your search are to use key terms or subject headings. Key terms are words that will appear frequently in the article. Subject headings are categories of articles grouped by theme.

Key Terms

- library catalog

-

A register of all bibliographic items found in a library or group of libraries, such as a network of libraries at several locations.

- database

-

A collection of (typically) organized information in a regular structure, usually but not necessarily in a machine-readable format accessible by a computer.

Example

- If you’re studying 19th-century theories of life, in the course of reading you might find “spontaneous generation,” which was a popular 19th-century theory of how life was formed. This could help open new avenues for searching further sources. If the topic of your paper is 19th-century scientific theories of life and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, some keywords that might be relevant for your search would include “science,” “Frankenstein,” and “life”.

Before you start conducting your research, you should have created a research plan with a specific research question. In addition to this plan, you should begin your search with an objective in mind. What exactly are you looking for? Do you want facts, opinions, statistics, quotations? Is the purpose of your research to find a new idea, find factual information to support a position, or something else? Once you decide what you are looking for, it is much easier to look for sources in the correct places and with the correct words and phrases.

Once you have your research topic and you know which databases you want to search for articles, you need to determine the best way to go about searching. For starters, you can’t just type in a question like, “What were medical practices like during the Battle of Gettysburg?” Instead, you should search one of two ways. The first option is to use key terms, or words that will appear frequently in the article. The second is to use subject headings—categories of articles grouped by theme.

To search key terms, think about important words that will occur in sources you could use. Then, type one or two of those terms into the search bar. Most search engines will generate results based on how frequently those words appear in articles and their abstracts.

Let’s use our topic from the previous section, medical practices at the Battle of Gettysburg, as an example. You might choose keywords like “amputation,” “field medicine,” and “Gettysburg.” This should yield articles that discuss amputations on the field during the Battle of Gettysburg. You could also search something like “anesthesia” and “Civil War,” which would lead you to articles about anesthetics during the war.

While searching with key terms, you may need to get creative. Some articles will use different language than you might expect, so try a variety of related terms to make sure you’re getting back all the possible results.

A lot of options

Phrase your search terms as specifically as possible, so that you only find relevant sources.

3.4: Understanding Your Sources

3.4.1: Understanding Your Sources

When researching, read through your sources twice: once to understand the author’s purpose and argument, and a second time to evaluate the argument.

Learning Objective

Outline the process for reading an academic source

Key Points

- Typically, you will need to read sources twice to get a complete picture of what they say and how you can use them.

- Your first reading should focus on understanding the source’s argument. Start by looking for the topic and the thesis, then consider the author’s stated purpose and the evidence he or she uses to support the argument.

- Your second reading should focus on whether you agree or disagree with the source, and whether you have any commentary that you would like to make about the author’s argument.

- Reading scientific articles requires a different strategy than reading a newspaper article or textbook: you should skim the text, compare the hypothesis to the conclusion, identify key terms and visual aids, and then read the article closely for content.

- Take notes as you read to understand your sources and the questions they raise.

- While reading critically, ask yourself questions to better understand the content, the author’s position, and the value of the source.

Key Terms

- thesis

-

A statement supported by arguments.

- audience

-

The readership of a book or other written publication.

- purpose

-

An object to be reached; a target; an aim; a goal.

Reading Your Sources

Once you’ve found sources to help your research, you must read each source carefully. To develop a sufficient understanding of the source, you will typically need to read it twice before including it in your essay. The first time should be devoted to understanding the argument the source is making. The second reading should focus on how the argument is made. At this stage, you should also determine whether you agree or disagree with the argument that the source is making, and whether it would support the argument you will make in your paper.

The First Reading

Start by looking for the topic and the thesis. What is the author’s stated purpose? What kind of evidence does he or she use to support the argument? What is the author saying? What is her purpose? The author could be trying to explain, inform, anger, persuade, amuse, motivate, sadden, ridicule, attack, or defend. Once you understand the argument and purpose, you can begin to evaluate the argument.

The Second Reading

This is the time to think about whether you agree or disagree with the source, and whether you have any commentary that you would like to make about the author’s argument. During your second reading you should consider the writer’s reputation and their intended audience. Determine whether you find the author credible or not. If you do, and if the author’s purpose and argument support your own, you can begin incorporating the source into your own writing. If you find the author credible but disagree with his purpose, it can still be valuable to consider the source in your own writing so that you can anticipate and acknowledge counterarguments later in your essay.

Finally, remember to pay attention to quotation marks as you read. It’s important to note whether the author of a text is writing, or if they are quoting someone else. Quotation marks are a helpful tool that authors use to help readers in distinguishing their voice from those of others. By paying attention to quotations and other cited material, you may also gain leads on other sources and authors you can incorporate in your paper.

Reading Scientific Articles

Do not read a scientific article as though you’re reading a textbook. Unlike academic articles, science textbooks organize information in chronological order and highlight important terms, definitions, and conclusions with bold text and graphics. Academic articles require a more proactive reading strategy.

Follow these four steps for reading scientific articles:

1. Before you read the entire article, skim it quickly for an overview of its structure.

2. Return to the beginning for a selective reading. Read the abstract, which will summarize the article. Read the beginning and end of the introduction, which will present the main points and explain their importance. Skim the conclusion to see how the results correspond to the hypothesis. As you read, look for keywords that signal important information, such as the following: surprising, unexpected, in contrast with previous work, we hypothesize that, we propose, we introduce, we develop, the data suggest.

3. Skim the entire article for common keywords and also visual aids (such as diagrams and charts), which are good indicators of important information.

4. At this point, you can read the article closely, attempting to draw inferences beyond what it states explicitly. As you read, take notes in a separate notebook, or in a computer document.

Questions for Guided Reading

If you want to make sure you catch the most important features of the article, ask pointed questions while you read. The following questions are essential to a thorough summary of a scientific article:

- What is the topic of the article?

- How is the problem, question, or issue defined?

- What is the purpose of the research? What question, problem, or issue did the article address in relation to the topic?

- Are any assumptions unusual or questionable?

- Why is the question, problem, or issue important? What situation exists that motivated the research?

- What experimental design is used? What methods are used?

- What are the results? How were they interpreted? What did the researcher conclude?

- Why is the article valuable or noteworthy? Does it answer a previously unanswered question, or contradict earlier research? Does it introduces a new method or technique? Does it test an old conclusion in a new way? Does it prove an old assumption false?

Taking Notes

No matter what you are reading, the following strategies are effective:

- Highlight important passages.

- Draw lines between the highlighted parts and briefly describe their connection.

- Map the relationships between key concepts.

- Make a list of keywords.

- Look for words that signal an important piece of information.

- Look for familiar concepts applied to new populations or situations.

- Try to find evidence that might contradict something that was established in your class.

Think about it …

Once you have scanned a source to know what it is about, reread it while thinking critically about its argument.

3.5: Using Your Sources

3.5.1: Taking Useful Notes on Your Sources

Taking organized notes on your sources as you do research will be helpful when you begin writing.

Learning Objective

Describe useful note-taking strategies

Key Points

- Notes should not only include bibliographic information, but also relevant arguments, quotes, and page numbers.

- Systematizing your note-taking while doing research will reduce the need to aimlessly search through all your sources when you transition into writing. Taking notes now, even though it may feel frustrating, is in your best interest in the long run.

- Use the full citation as your heading for each segment of notes you take. That way, you can be sure to have the citation ready when you start writing your paper.

Key Term

- citation

-

A paraphrase of a passage from a book, or from another person, for the purposes of a scholarly paper.

Example

- Consider the following source: Aldiss, Brian W. “On the Origin of Species: Mary Shelley.” Speculations on Speculation: Theories of Science Fiction. Eds. James Gunn and Matthew Candelaria. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow, 2005. Notes for this source might look like this: “Aldiss discusses the relationship between Erasmus Darwin, Charles Darwin’s grandfather, and the text of Frankenstein. See especially page five where Aldiss points out that the introduction includes references to galvanism and electricity.”

Why Take Notes While Researching?

While most of your research will take place before you begin writing, you will still refer to your resources throughout the writing process. This will be much easier if you take thorough notes while reading through your sources during the initial research phase.

The goal of note-taking is to keep a record of whatever information you might want to use later. Your notes should be as thorough as they need to be, but not too long that they are no longer useful to you. If you summarize information, make sure you include whatever you might want to incorporate in your paper. If you think a quote will be useful, write it down in full. Avoid copying whole paragraphs or pages, though; instead, decide exactly what is useful to you on that page and write only that down. You want to be able to look through your notes later on and easily see what information you found useful.

Organizing Your Notes

Organizing your notes is just as important as taking quality notes. You will need to track exactly which source each note came from so that you can properly cite your sources throughout your writing. Thus, the first thing you should do when taking notes is to write down the full citation for the source on which you are taking notes. This will help you find the source later on if you need to, and will ensure that you still have the complete citation even if you lose the source or have to return it to the library. Organizing notes by source also ensures that you will never lose track of how you need to cite them in your paper, so beginning with citation information provides a useful heading.

In addition to labeling each source, always be sure to write down the page numbers where you found whatever information you’ve written down. You will need to know the page number when you cite that information in your paper.

There are several methods for organizing your notes while researching, such as the following:

- Index cards: You may want to create an index card or set of cards for each source you use. You can then store the cards in order and can easily sort through them to find the notes you need.

- Online sources such as Microsoft OneNote: OneNote is a digital notebook that allows you to create new pages, tabs, and notebooks for your notes. You can quickly navigate between pages, and you will have the advantage of already having important quotations and citation information in typed form. This makes it easy to incorporate notes into your paper during the writing process.

- Organize by subtopic: Some sources may provide information on several subtopics that relate to your argument. You can choose to organize your notes for each source by subtopic so that when you get to that topic in your essay, you can easily find the notes on it. You can do this by creating headings or subheadings within your notes.

Taking notes

Some people use index cards to organize their notes while researching.

3.5.2: Maintaining an Annotated Bibliography

An annotated bibliography is a list of all your sources, including full citation information and notes on how you will use the sources.

Learning Objective

List the elements of an annotated bibliography

Key Points

- If you keep an annotated bibliography while you research, it will function as a useful guide. It will be easier for you to revisit sources later because you will already have notes explaining how you want to use them.

- If you find an annotated bibliography attached to one of the sources you are using, you can look at it to find other possible resources.

- It is important that you use the proper format when citing sources. Consult the style manual for whichever format your professor asks that you use.

- When you make notes on your sources, include a summary of the source, an evaluation of its reliability and potential bias, and a reflection on how the source could be used in the essay.

Key Terms

- bibliography

-

A list of books or documents relevant to a particular subject or author.

- annotation

-

A note that is made while reading any form of text that may be as simple as underlining or highlighting passages.

- citation

-

A paraphrase of a passage from a book, or from another person, for the purposes of a scholarly paper.

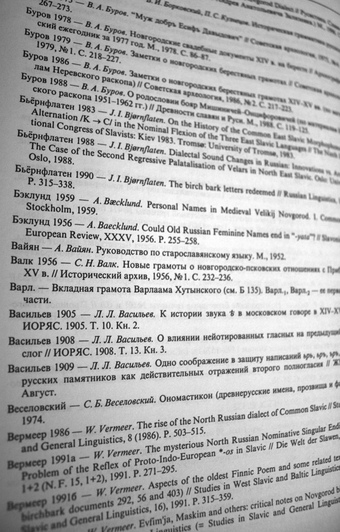

The Purpose of the Annotated Bibliography

An annotated bibliography is a list of all the sources you have researched, including both their full bibliographic citations and some notes on how you might want to use each resource in your work.

Annotated bibliographies are useful for several reasons. If you keep one while you research, the annotated bibliography will function as a useful guide. It will be easier for you to revisit sources later because you will already have notes explaining how you want to use each source. If you find an annotated bibliography attached to one of the sources you are using, you can look at it to find other possible resources.

Understand your notes

Annotated bibliographies include notes that explain what you found useful in each source, making it easier for you to refer back to appropriate sources later.

Constructing Your Citations

The first part of each entry in an annotated bibliography is the source’s full citation. A description of common citation practices can be found in the section entitled “Citing Sources Fully, Accurately, and Appropriately,” and detailed instructions can be found in the style manual for whatever format your professor wants you to use.

What to Include in Each Annotation

A good annotation has three parts, in addition to the complete bibliographic information for the source:

- a brief summary of the source

- a critique and evaluation of credibility, and

- an explanation of how you will use the source in your essay

Start by stating the main idea of the source. If you have space, note the specific information that you want to use from the source, such as quotations, chapters, or page numbers. Then explain if the source is credible, and note any potential bias you observe. Finally, explain how that information is useful to your own work.

You may also consider including:should also include some or all of the following:

- An explanation about the authority and/or qualifications of the author

- The scope or main purpose of the work

- Any detectable bias or interpretive stance

- The intended audience and level of reading

Example Annotation

Source: Farley, John. “The Spontaneous-Generation Controversy (1700–1860): The Origin of Parasitic Worms.” Journal of the History of Biology, 5 (Spring 1972), 95–125.

- Notes: This essay discusses the conversation about spontaneous generation that was taking place around the time that Frankenstein was written. In addition, it introduces a distinction between abiogenesis and heterogenesis. The author argues that the accounts of spontaneous generation from this time period were often based on incorrect assumptions: that the discussion was focused primarily on micro-organisms, and that spontaneous-generation theories were disproved by experiments. The author takes a scientific approach to evaluating theories of spontaneous generation, and the presentation of his argument is supported with sources. It is a reliable and credible source. The essay will be helpful in forming a picture of the early 19th-century conversation about how life is formed, as well as explaining the critical perception of spontaneous-generation theories during the 19th century.

3.5.3: Writing While You Research

Once you have enough notes, you should start writing, even if you intend to keep researching.

Learning Objective

Explain the use of beginning to write your paper during the research process

Key Points

- As you research, let yourself do some preliminary writing. Provide yourself with a space to think through ideas and consider how your ideas are related to each other. This can be a very helpful practice as you move into the writing phase.

- Writing as you read is a way to avoid getting bogged down in researching, which can feel endless as you try to determine what is and is not a relevant source. By causing you to think through your research materials, preliminary writing is a good way to build the specifics of your argument.

- Take notes as you read your sources, since relying on memory will lead to losing information. Similarly, start coming up with the organizational structure and argument of your paper as you gather research.

Key Terms

- drafting

-

The preliminary stage of a writing project in which the author begins to develop a more cohesive product.

- note

-

A mark, or sign, made to call attention to something.

- idea

-

The conception of someone or something as representing a perfect example; an ideal.

We often think of the writing process as a series of discrete steps. We first research, then take notes, then outline, then write. However, in practice, the different phases of writing a paper often overlap. As you research, you begin taking notes. As you take notes, you begin to see how you want to put your argument together and may even start developing an in-depth analysis of some of your sources. Even if you are not officially at the drafting stage of your paper, that’s okay. The research you do will often provide you with insights that you’ll want to include in your argument.

If you have an idea for your essay while taking notes, don’t wait to write it down—start developing it! While the idea is still fresh and clear, take a break from research and start working on your paper’s structure or argument. Writing about issues you discover in your research that you find interesting will take the tedium out of researching and outlining and will help you better understand the format your essay will take.

Once you have enough notes, you should start writing, even if you intend to keep researching. It can be tempting to get bogged down in the research process and avoid moving on to actually writing a first draft. Avoid this impulse by starting to write while still researching. At this early stage, it will still be easy to include new research as you find it.

You may only be able to write one section at a time, or you may start writing a section and realize that you need more support from your sources. Beginning to construct your paper during the research process helps you identify holes in your argument, weaknesses in your evidence or support, and may reveal a need to change the structure or format of your essay. It is often easier to address these issues in an ongoing manner than it is to wait until the end of either the research or writing process.

Active research

Don’t just read passively—take notes throughout the research process.

3.5.4: Incorporating Your Sources Into Your Paper

There are several ways to properly incorporate and give credit to the sources you cite within your paper.

Learning Objective

Name the ways of incorporating outside sources into your paper

Key Points

- There are three methods for referencing a source in the text of your paper: quoting, summarizing, and paraphrasing.

- Direct quotations are words and phrases that are taken directly from another source, and then used word-for-word in your paper.

- A summary is typically a short description that outlines the most important points and general position of the source.

- A paraphrase is when you put another source or part of a source (such as a chapter, paragraph, or page) into your own words.

- You should follow quotes with a description, in your own terms, of what the quote says and why it is relevant to the purpose of your paper.

- Follow the style guide you are using to properly format and cite your quotations and borrowed information.

Key Terms

- quotation

-

A fragment of a human expression that is being referred to by somebody else.

- paraphrase

-

A rewording of something written or spoken by someone else.

- summary

-

A short description that outlines the most important points and general position of the source.

How to Use Your Sources in Your Paper

Within the pages of your paper, it is important to properly reference and cite your sources to avoid plagiarism and to give credit for original ideas. Depending on which style guide you are using (e.g., APA, MLA), you will follow different methods to format your text to refer to others’ work.

There are three methods for referencing a source in the text of your paper: quoting, summarizing, and paraphrasing.

Quoting

Direct quotations are words and phrases that are taken directly from another source, and then used word-for-word in your paper. If you incorporate a direct quotation from another author’s text, you must put that quotation or phrase in quotation marks to indicate that it is not your language.

When writing direct quotations, you can use the source author’s name in the same sentence as the quotation to introduce the quoted text and to indicate the source in which you found the text. You should then include the page number or other relevant information in parentheses at the end of the phrase (the exact format will depend on the formatting style of your essay).

Summarizing

Summarizing involves distilling the main idea of a source into a much shorter overview. A summary outlines a source’s most important points and general position. When summarizing a source, it is still necessary to use a citation to give credit to the original author. You must reference the author or source in the appropriate parenthetical citation at the end of the summary.

Paraphrasing

When paraphrasing, you may put any part of a source (such as a phrase, sentence, paragraph, or chapter) into your own words.

You may find that the original source uses language that is more clear, concise, or specific than your own language, in which case you should use a direct quotation, putting quotation marks around those unique words or phrases you don’t change. It is common to use a mixture of paraphrased text and quoted words or phrases, as long as the direct quotations are inside of quotation marks.

Providing Context for Your Sources

Whether you use a direct quotation, a summary, or a paraphrase, it is important to distinguish the original source from your ideas, and to explain how the cited source fits into your argument. While the use of quotation marks or parenthetical citations tells your reader that these are not your own words or ideas, you should follow the quote with a description, in your own terms, of what the quote says and why it is relevant to the purpose of your paper. You should not let quoted or paraphrased text stand alone in your paper, but rather, should integrate the sources into your argument by providing context and explanations about how each source supports your argument.

The writing process

Signaling who is saying what is an important part of the writing process.

3.6: Citing Your Sources

3.6.1: The Importance of Citing Your Sources

To avoid plagiarism, one must provide an accurate citation every time information is used from an outside source.

Learning Objective

Identify the different types of citations and where they should appear in a paper.

Key Points

- An accurate citation includes complete reference information written in a regulated format. This should allow the reader to find the complete resource that was cited.

- Types of citations include parenthetical (in-text) citation, footnote, endnote, and full citation of all sources.

- A complete reference section (often titled “References” or “Works Cited” depending on citation style) comes at the end of your paper and lists all cited sources in alphabetical order.

- There are several different formats for citations, including MLA, APA, and Turabian style (also known as Chicago style or CMS). Rules for each of these styles are given in style manuals; they include detailed explanations and examples of how to cite sources correctly.

- Ask your teacher what specific style they want you to follow for your citations; typically they will want one style for all work submitted.

Key Terms

- plagiarism

-

The copying of another person’s ideas, text, or other creative work, and presenting it as one’s own, especially without permission.

- in-text citation

-

Reference information for a particular source presented within a paragraph, either as a parenthetical or integrated into a sentence.

- footnote

-

A short piece of text, often numbered, placed at the bottom of a printed page, that adds a comment, citation, reference, etc., to a designated part of the main text.

What Do You Need to Cite?

Any time you use specific material from an outside resource, you need to provide a citation that says exactly where you found that information. “Specific material” refers to quotations, detailed paraphrases, summaries, and images or graphs. If you use any of the above sources without citing them, you are committing plagiarism. If you are ever unsure whether to cite a source or not, you should cite the source. It is best to err on the side of caution to avoid plagiarism.

At the college level, plagiarism is an extremely serious offense. Students who plagiarize, whether intentionally or unintentionally, risk academic consequences that range from failing an assignment or a class to expulsion. Learning how to cite your sources is more than a stylistic requirement—it is a matter of academic integrity.

You will cite resources in two places: a brief citation in the text of your paper (in-text citation), and a full citation in a reference page at the end of your essay.

In-Text Citations

In-text citations come in two forms: the parenthetical, and the footnote (or endnote).

Parentheticals

Parenthetical citations include the necessary information in parentheses after a sentence. Parenthetical citations should include only enough information to direct the reader to the specific information you are citing. Most citations will require only the last name of the author and the page number where the information comes from, but this will vary according to the style manual you are directed to use by your professor. The following is an example of a parenthetical citation:

Aldiss claims Erasmus Darwin was an influence on the Romantic poets who surrounded Mary Shelley, describing his thought as “seminal” (Aldiss, 13).

Footnotes and Endnotes

Footnotes include a number at the end of the sentence that directs the reader to the appropriate note at the bottom of the page. Endnotes are exactly like footnotes, except the notes are at the end of the paper rather than at the bottom of the page. Footnotes and endnotes can be used both to cite a source, to provide additional information, or to provide context for a word or concept in your text.

For more detailed instructions, as well as information on what to do in exceptional circumstances, consult a style manual for whichever format is required.

Reference Section

Since in-text citations are kept brief, you will need to provide the full bibliographic details of your sources outside of the text of your paper. This is done in a reference section at the end of your paper. The name of this page differs depending on the style (MLA calls it the Works Cited section; APA calls it the References section). This page serves the same purpose for each style: it comes at the end of your paper and lists all your cited sources in alphabetical order (typically by the author’s last name).

Citation Style Manuals

Writing citations requires that you follow detailed formatting rules. There are several different formats, including MLA, APA, and Turabian style (also known as Chicago Manuscript Style). Rules for each of these styles are explained in style manuals, which include detailed explanations and many specific examples of how to cite things correctly. Most style guides include sections on citing online sources; writers should pay extra attention to the rules for verifying and citing sources from the web. Many publications and professors now require authors to run their papers through online plagiarism tools to ensure writing is original.

Your professor will most likely indicate the specific style that you should follow depending on the subject for which you are writing, so be sure to follow the correct style guide! You should find a copy of a style manual, either online or in print, and consult it frequently. It may seem tedious and fussy, but accurate citations are a necessary component of any reputable essay.

Understand your notes

Annotated bibliographies include notes that explain what you found useful in a source, making it easier for you to refer back to a source later.