3.1: Standardizing Financial Statements

3.1.1: Balance Sheets

A standard balance sheet has three parts: assets, liabilities, and ownership equity; Asset = Liabilities + Equity.

Learning Objective

Identify the basics of a balance sheet

Key Points

- Of the four basic financial statements, the balance sheet is the only statement which applies to a single point in time of a business’ calendar year.

- The main categories of assets are usually listed first (in order of liquidity) and are followed by the liabilities.

- The difference between the assets and the liabilities is known as “equity”.

- Balance sheets can either be in the report form or the account form.

- A balance sheet is often presented alongside one for a different point in time (typically the previous year) for comparison.

- Guidelines for balance sheets of public business entities are given by the International Accounting Standards Board and numerous country-specific organizations/companies.

Key Terms

- asset

-

Something or someone of any value; any portion of one’s property or effects so considered.

- equity

-

Ownership, especially in terms of net monetary value, of a business.

- balance sheet

-

A summary of a person’s or organization’s assets, liabilities and equity as of a specific date.

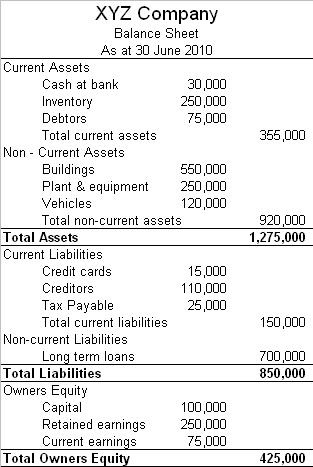

Balance sheet

In financial accounting, a balance sheet or statement of financial position is a summary of the financial balances of a sole proprietorship, a business partnership, a corporation or other business organization, such as an LLC or an LLP. Assets, liabilities and ownership equity are listed as of a specific date, such as the end of its financial year. A balance sheet is often described as a “snapshot of a company’s financial condition. ” Of the four basic financial statements, the balance sheet is the only statement which applies to a single point in time of a business’ calendar year.

A standard company balance sheet has three parts: assets, liabilities, and ownership equity. The main categories of assets are usually listed first, and typically in order of liquidity. Assets are followed by the liabilities. The difference between the assets and the liabilities is known as “equity. ” Equity is the net assets or net worth of the capital of the company. According to the accounting equation, net worth must equal assets minus liabilities.

Balance Sheet Example

Types

A balance sheet summarizes an organization or individual’s assets, equity, and liabilities at a specific point in time. We have two forms of balance sheet. They are the report form and the account form. Individuals and small businesses tend to have simple balance sheets. Larger businesses tend to have more complex balance sheets, and these are presented in the organization’s annual report. Large businesses also may prepare balance sheets for segments of their businesses. A balance sheet is often presented alongside one for a different point in time (typically the previous year) for comparison.

Personal Balance Sheet

A personal balance sheet lists current assets, such as cash in checking accounts and savings accounts; long-term assets, such as common stock and real estate; current liabilities, such as loan debt and mortgage debt due; or long-term liabilities, such as mortgage and other loan debt. Securities and real estate values are listed at market value rather than at historical cost or cost basis. Personal net worth is the difference between an individual’s total assets and total liabilities.

U.S. Small Business Balance Sheet

A small business balance sheet lists current assets, such as cash, accounts receivable and inventory; fixed assets, such as land, buildings, and equipment; intangible assets, such as patents; and liabilities, such as accounts payable, accrued expenses, and long-term debt. Contingent liabilities, such as warranties, are noted in the footnotes to the balance sheet. The small business’s equity is the difference between total assets and total liabilities.

Public Business Entities Balance Sheet

Structure

Guidelines for balance sheets of public business entities are given by the International Accounting Standards Board and numerous country-specific organizations/companies.

Balance sheet account names and usage depend on the organization’s country and the type of organization. Government organizations do not generally follow standards established for individuals or businesses.

If applicable to the business, summary values for the following items should be included in the balance sheet: Assets are all the things the business owns, including property, tools, cars, etc.

Assets:

1. Current assets

- Cash and cash equivalents

- Accounts receivable

- Inventories

- Prepaid expenses for future services that will be used within a year

2. Non-current assets (fixed assets)

- Property, plant, and equipment.

- Investment property, such as real estate held for investment purposes.

- Intangible assets.

- Financial assets (excluding investments accounted for using the equity method, accounts receivables, and cash and cash equivalents).

- Investments accounted for using the equity method

- Biological assets, which are living plants or animals. Bearer biological assets are plants or animals which bear agricultural produce for harvest, such as apple trees grown to produce apples and sheep raised to produce wool.

Liabilities:

- Accounts payable.

- Provisions for warranties or court decisions.

- Financial liabilities (excluding provisions and accounts payable), such as promissory notes and corporate bonds.

- Liabilities and assets for current tax.

- Deferred tax liabilities and deferred tax assets.

- Unearned revenue for services paid for by customers but not yet provided.

Equity:

- Issued capital and reserves attributable to equity holders of the parent company (controlling interest).

- Non-controlling interest in equity.

Regarding the items in equity section, the following disclosures are required:

- Numbers of shares authorized, issued and fully paid, and issued but not fully paid.

- Par value of shares.

- Reconciliation of shares outstanding at the beginning and the end of the period/

- Description of rights, preferences, and restrictions of shares.

- Treasury shares, including shares held by subsidiaries and associates.

- Shares reserved for issuance under options and contracts.

- A description of the nature and purpose of each reserve within owners’ equity

3.1.2: Income Statements

Income statement is a company’s financial statement that indicates how the revenue is transformed into the net income.

Learning Objective

Describe the different methods used for presenting data in a company’s income statement

Key Points

- Income statement displays the revenues recognized for a specific period, and the cost and expenses charged against these revenues, including write offs (e.g., depreciation and amortization of various assets) and taxes.

- The income statement can be prepared in one of two methods: The Single Step income statement and Multi-Step income statement.

- The income statement includes revenue, expenses, COGS, SG&A, depreciation, other revenues and expenses, finance costs, income tax expense, and net income.

Key Term

- intangible asset

-

Intangible assets are defined as identifiable non-monetary assets that cannot be seen, touched, or physically measured, and are created through time and effort, and are identifiable as a separate asset.

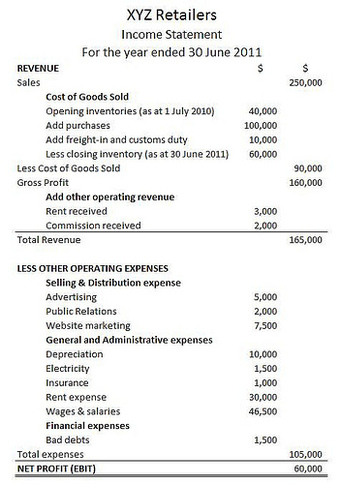

Income Statement

Income statement (also referred to as profit and loss statement [P&L]), revenue statement, a statement of financial performance, an earnings statement, an operating statement, or statement of operations) is a company’s financial statement. This indicates how the revenue (money received from the sale of products and services before expenses are taken out, also known as the “top line”) is transformed into the net income (the result after all revenues and expenses have been accounted for, also known as “Net Profit” or the “bottom line”). It displays the revenues recognized for a specific period, and the cost and expenses charged against these revenues, including write offs (e.g., depreciation and amortization of various assets) and taxes. The purpose of the income statement is to show managers and investors whether the company made or lost money during the period being reported.

The important thing to remember about an income statement is that it represents a period of time. This contrasts with the balance sheet, which represents a single moment in time.

Income statement

GAAP and IRS accounting can differ.

Two Methods

- The Single Step income statement takes a simpler approach, totaling revenues and subtracting expenses to find the bottom line.

- The Multi-Step income statement (as the name implies) takes several steps to find the bottom line, starting with the gross profit. It then calculates operating expenses and, when deducted from the gross profit, yields income from operations. Adding to income from operations is the difference of other revenues and other expenses. When combined with income from operations, this yields income before taxes. The final step is to deduct taxes, which finally produces the net income for the period measured.

Operating Section

- Revenue – cash inflows or other enhancements of assets of an entity during a period from delivering or producing goods, rendering services, or other activities that constitute the entity’s ongoing major operations. It is usually presented as sales minus sales discounts, returns, and allowances. Every time a business sells a product or performs a service, it obtains revenue. This often is referred to as gross revenue or sales revenue.

- Expenses – cash outflows or other using-up of assets or incurrence of liabilities during a period from delivering or producing goods, rendering services, or carrying out other activities that constitute the entity’s ongoing major operations.

- Cost of Goods Sold (COGS)/Cost of Sales – represents the direct costs attributable to goods produced and sold by a business (manufacturing or merchandizing). It includes material costs, direct labor, and overhead costs (as in absorption costing), and excludes operating costs (period costs), such as selling, administrative, advertising or R&D, etc.

- Selling, General and Administrative expenses (SG&A or SGA) – consist of the combined payroll costs. SGA is usually understood as a major portion of non-production related costs, in contrast to production costs such as direct labour.

- Selling expenses – represent expenses needed to sell products (e.g., salaries of sales people, commissions, and travel expenses; advertising; freight; shipping; depreciation of sales store buildings and equipment, etc.).

- General and Administrative (G&A) expenses – represent expenses to manage the business (salaries of officers/executives, legal and professional fees, utilities, insurance, depreciation of office building and equipment, office rents, office supplies, etc.).

- Depreciation/Amortization – the charge with respect to fixed assets/intangible assets that have been capitalized on the balance sheet for a specific (accounting) period. It is a systematic and rational allocation of cost rather than the recognition of market value decrement.

- Research & Development (R&D) expenses – represent expenses included in research and development.

- Expenses recognized in the income statement should be analyzed either by nature (raw materials, transport costs, staffing costs, depreciation, employee benefit, etc.) or by function (cost of sales, selling, administrative, etc.).

Non-operating Section

- Other revenues or gains – revenues and gains from other than primary business activities (e.g., rent, income from patents).

- Other expenses or losses – expenses or losses not related to primary business operations, (e.g., foreign exchange loss).

- Finance costs – costs of borrowing from various creditors (e.g., interest expenses, bank charges).

- Income tax expense – sum of the amount of tax payable to tax authorities in the current reporting period (current tax liabilities/tax payable) and the amount of deferred tax liabilities (or assets).

- Irregular items – are reported separately because this way users can better predict future cash flows – irregular items most likely will not recur. These are reported net of taxes.

Bottom Line

Bottom line is the net income that is calculated after subtracting the expenses from revenue. Since this forms the last line of the income statement, it is informally called “bottom line. ” It is important to investors as it represents the profit for the year attributable to the shareholders.

3.2: Overview of Ratio Analysis

3.2.1: Classification

Ratio analysis consists of calculating financial performance using five basic types of ratios: profitability, liquidity, activity, debt, and market.

Learning Objective

Classify a financial ratio based on what it measures in a company

Key Points

- Ratio analysis consists of the calculation of ratios from financial statements and is a foundation of financial analysis.

- A financial ratio, or accounting ratio, shows the relative magnitude of selected numerical values taken from those financial statements.

- The numbers contained in financial statements need to be put into context so that investors can better understand different aspects of the company’s operations. Ratio analysis is one method an investor can use to gain that understanding.

Key Terms

- liquidity

-

Availability of cash over short term: ability to service short-term debt.

- ratio

-

A number representing a comparison between two things.

- ratio analysis

-

the use of quantitative techniques on values taken from an enterprise’s financial statements

- shareholder

-

One who owns shares of stock.

Classification

Financial statements are generally insufficient to provide information to investors on their own; the numbers contained in those documents need to be put into context so that investors can better understand different aspects of the company’s operations. Ratio analysis is one of three methods an investor can use to gain that understanding.

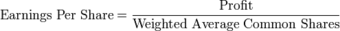

Business analysis and profitability

Financial ratio analysis allows an observer to put the data provided by a company in context. This allows the observer to gauge the strength of different aspects of the company’s operations.

Financial statement analysis is the process of understanding the risk and profitability of a firm through analysis of reported financial information. Ratio analysis is a foundation for evaluating and pricing credit risk and for doing fundamental company valuation. A financial ratio, or accounting ratio, is derived from a company’s financial statements and is a calculation showing the relative magnitude of selected numerical values taken from those financial statements.

There are various types of financial ratios, grouped by their relevance to different aspects of a company’s business as well as to their interest to different audiences. Financial ratios may be used internally by managers within a firm, by current and potential shareholders and creditors of a firm, and other audiences interested in understanding the strengths and weaknesses of a company, especially compared to the company over time or compared to other companies.

Types of Ratios

Most analysts think of financial ratios as consisting of five basic types:

- Profitability ratios measure the firm’s use of its assets and control of its expenses to generate an acceptable rate of return.

- Liquidity ratios measure the availability of cash to pay debt.

- Activity ratios, also called efficiency ratios, measure the effectiveness of a firm’s use of resources, or assets.

- Debt, or leverage, ratios measure the firm’s ability to repay long-term debt.

- Market ratios are concerned with shareholder audiences. They measure the cost of issuing stock and the relationship between return and the value of an investment in company’s shares.

3.3: Profitability Ratios

3.3.1: Operating Margin

The operating margin is a ratio that determines how much money a company is actually making in profit and equals operating income divided by revenue.

Learning Objective

Calculate a company’s operating margin

Key Points

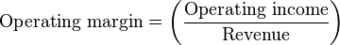

- The operating margin equals operating income divided by revenue.

- The operating margin shows how much profit a company makes for each dollar in revenue. Since revenues and expenses are considered ‘operating’ in most companies, this is a good way to measure a company’s profitability.

- Although It is a good starting point for analyzing many companies, there are items like interest and taxes that are not included in operating income. Therefore, the operating margin is an imperfect measurement a company’s profitability.

Key Term

- operating income

-

Revenue – operating expenses. (Does not include other expenses such as taxes and depreciation).

Operating Margin

The financial job of a company is to earn a profit, which is different than earning revenue. If a company doesn’t earn a profit, their revenues aren’t helping the company grow. It is not only important to see how much a company has sold, it is important to see how much a company is making.

The operating margin (also called the operating profit margin or return on sales) is a ratio that shines a light on how much money a company is actually making in profit. It is found by dividing operating income by revenue, where operating income is revenue minus operating expenses .

Operating margin formula

The operating margin is found by dividing net operating income by total revenue.

The higher the ratio is, the more profitable the company is from its operations. For example, an operating margin of 0.5 means that for every dollar the company takes in revenue, it earns $0.50 in profit. A company that is not making any money will have an operating margin of 0: it is selling its products or services, but isn’t earning any profit from those sales.

However, the operating margin is not a perfect measurement. It does not include things like capital investment, which is necessary for the future profitability of the company. Furthermore, the operating margin is simply revenue. That means that it does not include things like interest and income tax expenses. Since non-operating incomes and expenses can significantly affect the financial well-being of a company, the operating margin is not the only measurement that investors scrutinize. The operating margin is a useful tool for determining how profitable the operations of a company are, but not necessarily how profitable the company is as a whole.

3.3.2: Profit Margin

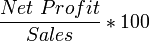

Profit margin measures the amount of profit a company earns from its sales and is calculated by dividing profit (gross or net) by sales.

Learning Objective

Calculate a company’s net and gross profit margin

Key Points

- Profit margin is the profit divided by revenue.

- There are two types of profit margin: gross profit margin and net profit margin.

- A higher profit margin is better for the company, but there may be strategic decisions made to lower the profit margin or to even have it be negative.

Key Terms

- gross profit

-

The difference between net sales and the cost of goods sold.

- net profit

-

The gross revenue minus all expenses.

Profit Margin

Profit margin is one of the most used profitability ratios. Profit margin refers to the amount of profit that a company earns through sales.

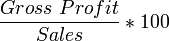

The profit margin ratio is broadly the ratio of profit to total sales times 100%. The higher the profit margin, the more profit a company earns on each sale.

Since there are two types of profit (gross and net), there are two types of profit margin calculations. Recall that gross profit is simply the revenue minus the cost of goods sold (COGS). Net profit is the gross profit minus all other expenses. The gross profit margin calculation uses gross profit and the net profit margin calculation uses net profit . The difference between the two is that the gross profit margin shows the relationship between revenue and COGS, while the net profit margin shows the percentage of the money spent by customers that is turned into profit.

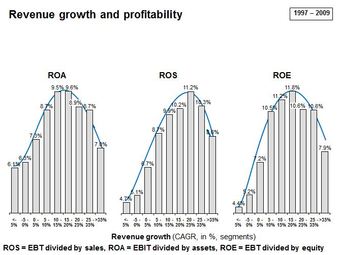

Net Profit Margin

The percentage of net profit (gross profit minus all other expenses) earned on a company’s sales.

Gross Profit Margin

The percentage of gross profit earned on the company’s sales.

Companies need to have a positive profit margin in order to earn income, although having a negative profit margin may be advantageous in some instances (e.g. intentionally selling a new product below cost in order to gain market share).

The profit margin is mostly used for internal comparison. It is difficult to accurately compare the net profit ratio for different entities. Individual businesses’ operating and financing arrangements vary so much that different entities are bound to have different levels of expenditure. Comparing one business’ arrangements with another has little meaning. A low profit margin indicates a low margin of safety. There is a higher risk that a decline in sales will erase profits and result in a net loss or a negative margin.

3.3.3: Return on Total Assets

The return on assets ratio (ROA) measures how effectively assets are being used for generating profit.

Learning Objective

Calculate a company’s return on assets

Key Points

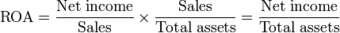

- ROA is net income divided by total assets.

- The ROA is the product of two common ratios: profit margin and asset turnover.

- A higher ROA is better, but there is no metric for a good or bad ROA. An ROA depends on the company, the industry and the economic environment.

- ROA is based on the book value of assets, which can be starkly different from the market value of assets.

Key Terms

- net income

-

Gross profit minus operating expenses and taxes.

- asset

-

Something or someone of any value; any portion of one’s property or effects so considered.

Return

on Assets

The return on assets ratio (ROA) is found by dividing net income by total assets. The higher the ratio, the better the company is at using their assets to generate income. ROA was developed by DuPont to show how effectively assets are being used. It is also a measure of how much the company relies on assets to generate profit.

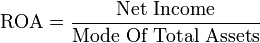

Return on Assets

The return on assets ratio is net income divided by total assets. That can then be broken down into the product of profit margins and asset turnover.

Components of ROA

ROA can be broken down into multiple parts. The ROA is the product of two other common ratios – profit margin and asset turnover. When profit margin and asset turnover are multiplied together, the denominator of profit margin and the numerator of asset turnover cancel each other out, returning us to the original ratio of net income to total assets.

Profit margin is net income divided by sales, measuring the percent of each dollar in sales that is profit for the company. Asset turnover is sales divided by total assets. This ratio measures how much each dollar in asset generates in sales. A higher ratio means that each dollar in assets produces more for the company.

Limits of ROA

ROA does have some drawbacks. First, it gives no indication of how the assets were financed. A company could have a high ROA, but still be in financial straits because all the assets were paid for through leveraging. Second, the total assets are based on the carrying value of the assets, not the market value. If there is a large discrepancy between the carrying and market value of the assets, the ratio could provide misleading numbers. Finally, there is no metric to find a good or bad ROA. Companies that operate in capital intensive industries will tend to have lower ROAs than those who do not. The ROA is entirely contextual to the company, the industry and the economic environment.

3.3.4: Basic Earning Power (BEP) Ratio

The Basic Earning Power ratio (BEP) is Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) divided by Total Assets.

Learning Objective

Calculate a company’s Basic Earning Power ratio

Key Points

- The higher the BEP ratio, the more effective a company is at generating income from its assets.

- Using EBIT instead of operating income means that the ratio considers all income earned by the company, not just income from operating activity. This gives a more complete picture of how the company makes money.

- BEP is useful for comparing firms with different tax situations and different degrees of financial leverage.

Key Terms

- EBIT

-

Earnings before interest and taxes. A measure of a business’s profitability.

- Return on Assets

-

A measure of a company’s profitability. Calculated by dividing the net income for an accounting period by the average of the total assets the business held during that same period.

BEP Ratio

Another profitability ratio is the Basic Earning Power ratio (BEP). The purpose of BEP is to determine how effectively a firm uses its assets to generate income.

The BEP ratio is simply EBIT divided by total assets . The higher the BEP ratio, the more effective a company is at generating income from its assets.

Basic Earnings Power Ratio

BEP is calculated as the ratio of Earnings Before Interest and Taxes to Total Assets.

This may seem remarkably similar to the return on assets ratio (ROA), which is operating income divided by total assets. EBIT, or earnings before interest and taxes, is a measure of how much money a company makes, but is not necessarily the same as operating income:

EBIT = Revenue – Operating expenses+

Non-operating

income

Operating income = Revenue – Operating expenses

The distinction between EBIT and Operating Income is non-operating income. Since EBIT includes non-operating income (such as dividends paid on the stock a company holds of another), it is a more inclusive way to measure the actual income of a company. However, in most cases, EBIT is relatively close to Operating Income.

The advantage of using EBIT, and thus BEP, is that it allows for more accurate comparisons of companies. BEP disregards different tax situations and degrees of financial leverage while still providing an idea of how good a company is at using its assets to generate income.

BEP, like all profitability ratios, does not provide a complete picture of which company is better or more attractive to investors. Investors should favor a company with a higher BEP over a company with a lower BEP because that means it extracts more value from its assets, but they still need to consider how things like leverage and tax rates affect the company.

3.3.5: Return on Common Equity

Return on equity (ROE) measures how effective a company is at using its equity to generate income and is calculated by dividing net profit by total equity.

Learning Objective

Calculate the Return on Equity (ROE) for a business

Key Points

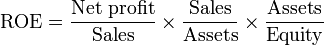

- ROE is net income divided by total shareholders’ equity.

- ROE is also the product of return on assets (ROA) and financial leverage.

- ROE shows how well a company uses investment funds to generate earnings growth. There is no standard for a good or bad ROE, but a higher ROE is better.

Key Term

- equity

-

Ownership, especially in terms of net monetary value, of a business.

Return on Equity

Return on equity (ROE) is a financial ratio that measures how good a company is at generating profit.

ROE is the ratio of net income to equity. From the fundamental equation of accounting, we know that equity equals net assets minus net liabilities. Equity is the amount of ownership interest in the company, and is commonly referred to as shareholders’ equity, shareholders’ funds, or shareholders’ capital.

In essence, ROE measures how efficient the company is at generating profits from the funds invested in it. A company with a high ROE does a good job of turning the capital invested in it into profit, and a company with a low ROE does a bad job. However, like many of the other ratios, there is no standard way to define a good ROE or a bad ROE. Higher ratios are better, but what counts as “good” varies by company, industry, and economic environment.

ROE can also be broken down into other components for easier use. ROE is the product of the net margin (profit margin), asset turnover, and financial leverage. Also note that the product of net margin and asset turnover is return on assets, so ROE is ROA times financial leverage.

Return on Equity

The return on equity is a ratio of net income to equity. It is a measure of how effective the equity is at generating income.

Breaking ROE into parts allows us to understand how and why it changes over time. For example, if the net margin increases, every sale brings in more money, resulting in a higher overall ROE. Similarly, if the asset turnover increases, the firm generates more sales for every unit of assets owned, again resulting in a higher overall ROE. Finally, increasing financial leverage means that the firm uses more debt financing relative to equity financing. Interest payments to creditors are tax deductible, but dividend payments to shareholders are not. Thus, a higher proportion of debt in the firm’s capital structure leads to higher ROE. Financial leverage benefits diminish as the risk of defaulting on interest payments increases. So if the firm takes on too much debt, the cost of debt rises as creditors demand a higher risk premium, and ROE decreases. Increased debt will make a positive contribution to a firm’s ROE only if the matching return on assets (ROA) of that debt exceeds the interest rate on the debt.

3.4: Asset Management Ratios

3.4.1: Inventory Turnover Ratio

Inventory turnover is a measure of the number of times inventory is sold or used in a time period, such as a year.

Learning Objective

Calculate inventory turnover and average days to sell inventory for a business

Key Points

- Inventory turnover = Cost of goods sold/Average inventory.

- Average days to sell the inventory = 365 days /Inventory turnover ratio.

- A low turnover rate may point to overstocking, obsolescence, or deficiencies in the product line or marketing effort.

- Conversely, a high turnover rate may indicate inadequate inventory levels, which may lead to a loss in business as the inventory is too low.

Key Term

- holding cost

-

In business management, holding cost is money spent to keep and maintain a stock of goods in storage.

Inventory Turnover

In accounting, the Inventory turnover is a measure of the number of times inventory is sold or used in a time period, such as a year. The equation for inventory turnover equals the cost of goods sold divided by the average inventory. Inventory turnover is also known as inventory turns, stockturn, stock turns, turns, and stock turnover.

Inventory Turnover Equation

- The formula for inventory turnover:

Inventory turnover = Cost of goods sold/Average inventory

- The formula for average inventory:

Average inventory = (Beginning inventory + Ending inventory)/2

- The average days to sell the inventory is calculated as follows:

Average days to sell the inventory = 365 days / Inventory turnover ratio

Application in Business

A low turnover rate may point to overstocking, obsolescence, or deficiencies in the product line or marketing effort. However, in some instances a low rate may be appropriate, such as where higher inventory levels occur in anticipation of rapidly rising prices or expected market shortages.

Inventory

A low turnover rate may point to overstocking, obsolescence, or deficiencies in the product line or marketing effort.

Conversely, a high turnover rate may indicate inadequate inventory levels, which may lead to a loss in business as the inventory is too low. This often can result in stock shortages.

Some compilers of industry data (e.g., Dun & Bradstreet) use sales as the numerator instead of cost of sales. Cost of sales yields a more realistic turnover ratio, but it is often necessary to use sales for purposes of comparative analysis. Cost of sales is considered to be more realistic because of the difference in which sales and the cost of sales are recorded. Sales are generally recorded at market value (i.e., the value at which the marketplace paid for the good or service provided by the firm). In the event that the firm had an exceptional year and the market paid a premium for the firm’s goods and services, then the numerator may be an inaccurate measure. However, cost of sales is recorded by the firm at what the firm actually paid for the materials available for sale. Additionally, firms may reduce prices to generate sales in an effort to cycle inventory. In this article, the terms “cost of sales” and “cost of goods sold” are synonymous.

An item whose inventory is sold (turns over) once a year has a higher holding cost than one that turns over twice, or three times, or more in that time. Stock turnover also indicates the briskness of the business. The purpose of increasing inventory turns is to reduce inventory for three reasons.

- Increasing inventory turns reduces holding cost. The organization spends less money on rent, utilities, insurance, theft, and other costs of maintaining a stock of good to be sold.

- Reducing holding cost increases net income and profitability as long as the revenue from selling the item remains constant.

- Items that turn over more quickly increase responsiveness to changes in customer requirements while allowing the replacement of obsolete items. This is a major concern in fashion industries.

When making comparison between firms, it’s important to take note of the industry, or the comparison will be distorted. Making comparison between a supermarket and a car dealer, will not be appropriate, as a supermarket sells fast moving goods, such as sweets, chocolates, soft drinks, so the stock turnover will be higher. However, a car dealer will have a low turnover due to the item being a slow moving item. As such, only intra-industry comparison will be appropriate.

3.4.2: Days Sales Outstanding

Days sales outstanding (also called DSO or days receivables) is a calculation used by a company to estimate their average collection period.

Learning Objective

Calculate the days sales outstanding ratio for a business

Key Points

- Days sales outstanding is a financial ratio that illustrates how well a company’s accounts receivables are being managed.

- DSO ratio = accounts receivable / average sales per day, or DSO ratio = accounts receivable / (annual sales / 365 days).

- Generally speaking, higher DSO ratio can indicate a customer base with credit problems and/or a company that is deficient in its collections activity. A low ratio may indicate the firm’s credit policy is too rigorous, which may be hampering sales.

Key Terms

- days in inventory

-

the average value of inventory divided by the average cost of goods sold per day

- average collection period

-

365 divided by the receivables turnover ratio

- outstanding check

-

a check that has been written but has not yet been deposited in the receiver’s bank account

- business cycle

-

The term business cycle (or economic cycle) refers to economy-wide fluctuations in production or economic activity over several months or years.

Days Sales Outstanding

In accountancy, days sales outstanding (also called DSO or days receivables) is a calculation used by a company to estimate their average collection period. It is a financial ratio that illustrates how well a company’s accounts receivables are being managed. The days sales outstanding figure is an index of the relationship between outstanding receivables and credit account sales achieved over a given period.

Typically, days sales outstanding is calculated monthly. The days sales outstanding analysis provides general information about the number of days on average that customers take to pay invoices. Generally speaking, though, higher DSO ratio can indicate a customer base with credit problems and/or a company that is deficient in its collections activity. A low ratio may indicate the firm’s credit policy is too rigorous, which may be hampering sales.

Days sales outstanding is considered an important tool in measuring liquidity. Days sales outstanding tends to increase as a company becomes less risk averse. Higher days sales outstanding can also be an indication of inadequate analysis of applicants for open account credit terms. An increase in DSO can result in cash flow problems, and may result in a decision to increase the creditor company’s bad debt reserve.

A DSO ratio can be expressed as:

- DSO ratio = accounts receivable / average sales per day, or

- DSO ratio = accounts receivable / (annual sales / 365 days)

For purposes of this ratio, a year is considered to have 365 days.

Days sales outstanding can vary from month to month and over the course of a year with a company’s seasonal business cycle. Of interest, when analyzing the performance of a company, is the trend in DSO. If DSO is getting longer, customers are taking longer to pay their bills, which may be a warning that customers are dissatisfied with the company’s product or service, or that sales are being made to customers that are less credit worthy or that sales people have to offer longer payment terms in order to generate sales. Many financial reports will state Receivables Turnover defined as Net Credit Account Sales / Trade Receivables; divide this value into the time period in days to get DSO.

However, days sales outstanding is not the most accurate indication of the efficiency of accounts receivable department. Changes in sales volume influence the outcome of the days sales outstanding calculation. For example, even if the overdue balance stays the same, an increase of sales can result in a lower DSO. A better way to measure the performance of credit and collection function is by looking at the total overdue balance in proportion of the total accounts receivable balance (total AR = Current + Overdue), which is sometimes calculated using the days’ delinquent sales outstanding (DDSO) formula.

3.4.3: Fixed Assets Turnover Ratio

Fixed-asset turnover is the ratio of sales to value of fixed assets, indicating how well the business uses fixed assets to generate sales.

Learning Objective

Calculate the fixed-asset turnover ratio for a business

Key Points

- Fixed asset turnover = Net sales / Average net fixed assets.

- The higher the ratio, the better, because a high ratio indicates the business has less money tied up in fixed assets for each unit of currency of sales revenue. A declining ratio may indicate that the business is over-invested in plant, equipment, or other fixed assets.

- Fixed assets, also known as a non-current asset or as property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), is a term used in accounting for assets and property that cannot easily be converted into cash.

Key Term

- IAS

-

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) are designed as a common global language for business affairs so that company accounts are understandable and comparable across international boundaries.

Fixed Assets

Fixed assets, also known as a non-current asset or as property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), is a term used in accounting for assets and property that cannot easily be converted into cash. This can be compared with current assets, such as cash or bank accounts, which are described as liquid assets. In most cases, only tangible assets are referred to as fixed.

Moreover, a fixed/non-current asset also can be defined as an asset not directly sold to a firm’s consumers/end-users. As an example, a baking firm’s current assets would be its inventory (in this case, flour, yeast, etc.), the value of sales owed to the firm via credit (i.e., debtors or accounts receivable), cash held in the bank, etc. Its non-current assets would be the oven used to bake bread, motor vehicles used to transport deliveries, cash registers used to handle cash payments, etc. Each aforementioned non-current asset is not sold directly to consumers.

These are items of value that the organization has bought and will use for an extended period of time; fixed assets normally include items, such as land and buildings, motor vehicles, furniture, office equipment, computers, fixtures and fittings, and plant and machinery. These often receive favorable tax treatment (depreciation allowance) over short-term assets. According to International Accounting Standard (IAS) 16, Fixed Assets are assets which have future economic benefit that is probable to flow into the entity and which have a cost that can be measured reliably.

The primary objective of a business entity is to make a profit and increase the wealth of its owners. In the attainment of this objective, it is required that the management will exercise due care and diligence in applying the basic accounting concept of “Matching Concept.” Matching concept is simply matching the expenses of a period against the revenues of the same period.

The use of assets in the generation of revenue is usually more than a year–that is long term. It is, therefore, obligatory that in order to accurately determine the net income or profit for a period depreciation, it is charged on the total value of asset that contributed to the revenue for the period in consideration and charge against the same revenue of the same period. This is essential in the prudent reporting of the net revenue for the entity in the period.

Fixed-asset Turnover

Fixed-asset turnover is the ratio of sales (on the profit and loss account) to the value of fixed assets (on the balance sheet). It indicates how well the business is using its fixed assets to generate sales.

Turn Tables

Turn tables should help you remember turnover. Fixed-asset turnover indicates how well the business is using its fixed assets to generate sales.

Fixed asset turnover = Net sales / Average net fixed assets

Generally speaking, the higher the ratio, the better, because a high ratio indicates the business has less money tied up in fixed assets for each unit of currency of sales revenue. A declining ratio may indicate that the business is over-invested in plant, equipment, or other fixed assets.

3.4.4: Total Assets Turnover Ratio

Total asset turnover is a financial ratio that measures the efficiency of a company’s use of its assets in generating sales revenue.

Learning Objective

Calculate the total assets turnover ratio for a business

Key Points

- Total assets turnover = Net sales revenue / Average total assets.

- Net sales are operating revenues earned by a company for selling its products or rendering its services.

- Anything tangible or intangible that is capable of being owned or controlled to produce value and that is held to have positive economic value is considered an asset.

- Companies with low profit margins tend to have high asset turnover, while those with high profit margins have low asset turnover.

Key Term

- profit margins

-

Profit margin, net margin, net profit margin or net profit ratio all refer to a measure of profitability. It is calculated by finding the net profit as a percentage of the revenue.

Example

- Examples of intangible assets are goodwill, copyrights, trademarks, patents, computer programs, and financial assets, including such items as accounts receivable, bonds and stocks.

Total assets turnover

This is a financial ratio that measures the efficiency of a company’s use of its assets in generating sales revenue or sales income to the company.

Assets

Asset turnover measures the efficiency of a company’s use of its assets in generating sales revenue or sales income to the company.

Companies with low profit margins tend to have high asset turnover, while those with high profit margins have low asset turnover. Companies in the retail industry tend to have a very high turnover ratio due mainly to cut-throat and competitive pricing.

Total assets turnover = Net sales revenue / Average total assets

- “Sales” is the value of “Net Sales” or “Sales” from the company’s income statement”.

- Average Total Assets” is the average of the values of “Total assets” from the company’s balance sheet in the beginning and the end of the fiscal period. It is calculated by adding up the assets at the beginning of the period and the assets at the end of the period, then dividing that number by two.

Net sales

- In bookkeeping, accounting, and finance, Net sales are operating revenues earned by a company for selling its products or rendering its services. Also referred to as revenue, they are reported directly on the income statement as Sales or Net sales.

- In financial ratios that use income statement sales values, “sales” refers to net sales, not gross sales. Sales are the unique transactions that occur in professional selling or during marketing initiatives.

Total assets

In financial accounting, assets are economic resources. Anything tangible or intangible that is capable of being owned or controlled to produce value, and that is held to have positive economic value, is considered an asset. Simply stated, assets represent value of ownership that can be converted into cash (although cash itself is also considered an asset).

The balance sheet of a firm records the monetary value of the assets owned by the firm. It is money and other valuables belonging to an individual or business.

Two major asset classes are tangible assets and intangible assets.

- Tangible assets contain various subclasses, including current assets and fixed assets. Current assets include inventory, while fixed assets include such items as buildings and equipment.

- Intangible assets are non-physical resources and rights that have a value to the firm because they give the firm some kind of advantage in the market place.

3.5: Liquidity Ratios

3.5.1: Current Ratio

Current ratio is a financial ratio that measures whether or not a firm has enough resources to pay its debts over the next 12 months.

Learning Objective

Use a company’s current ratio to evaluate its short-term financial strength

Key Points

- The liquidity ratio expresses a company’s ability to repay short-term creditors out of its total cash. The liquidity ratio is the result of dividing the total cash by short-term borrowings.

- The current ratio is a financial ratio that measures whether or not a firm has enough resources to pay its debts over the next 12 months.

- Current ratio = current assets / current liabilities.

- Acceptable current ratios vary from industry to industry and are generally between 1.5 and 3 for healthy businesses.

Key Terms

- working capital management

-

Decisions relating to working capital and short term financing are referred to as working capital management [19]. These involve managing the relationship between a firm’s short-term assets and its short-term liabilities.

- current ratio

-

current assets divided by current liabilities

Liquidity Ratio

Liquidity ratio expresses a company’s ability to repay short-term creditors out of its total cash. The liquidity ratio is the result of dividing the total cash by short-term borrowings. It shows the number of times short-term liabilities are covered by cash. If the value is greater than 1.00, it means it is fully covered .

Liquidity

High liquidity means a company has the ability to meet its short-term obligations.

Liquidity ratio may refer to:

- Reserve requirement – a bank regulation that sets the minimum reserves each bank must hold.

- Acid Test – a ratio used to determine the liquidity of a business entity.

The formula is the following:

LR = liquid assets / short-term liabilities

Current Ratio

The current ratio is a financial ratio that measures whether or not a firm has enough resources to pay its debts over the next 12 months. It compares a firm’s current assets to its current liabilities. It is expressed as follows:

Current ratio = current assets / current liabilities

- Current asset is an asset on the balance sheet that can either be converted to cash or used to pay current liabilities within 12 months. Typical current assets include cash, cash equivalents, short-term investments, accounts receivable, inventory, and the portion of prepaid liabilities that will be paid within a year.

- Current liabilities are often understood as all liabilities of the business that are to be settled in cash within the fiscal year or the operating cycle of a given firm, whichever period is longer.

The current ratio is an indication of a firm’s market liquidity and ability to meet creditor’s demands. Acceptable current ratios vary from industry to industry and are generally between 1.5 and 3 for healthy businesses. If a company’s current ratio is in this range, then it generally indicates good short-term financial strength. If current liabilities exceed current assets (the current ratio is below 1), then the company may have problems meeting its short-term obligations. If the current ratio is too high, then the company may not be efficiently using its current assets or its short-term financing facilities. This may also indicate problems in working capital management. In such a situation, firms should consider investing excess capital into middle and long term objectives.

Low values for the current or quick ratios (values less than 1) indicate that a firm may have difficulty meeting current obligations. However, low values do not indicate a critical problem. If an organization has good long-term prospects, it may be able to borrow against those prospects to meet current obligations. Some types of businesses usually operate with a current ratio less than one. For example, if inventory turns over much more rapidly than the accounts payable do, then the current ratio will be less than one. This can allow a firm to operate with a low current ratio.

If all other things were equal, a creditor, who is expecting to be paid in the next 12 months, would consider a high current ratio to be better than a low current ratio. A high current ratio means that the company is more likely to meet its liabilities which fall due in the next 12 months.

3.5.2: Quick Ratio (Acid-Test Ratio)

The Acid Test or Quick Ratio measures the ability of a company to use its assets to retire its current liabilities immediately.

Learning Objective

Calculate a company’s quick ratio

Key Points

- Quick Ratio = (Cash and cash equivalent + Marketable securities + Accounts receivable) / Current liabilities.

- Acid Test Ratio = (Current assets – Inventory) / Current liabilities.

- Ideally, the acid test ratio should be 1:1 or higher, however this varies widely by industry. In general, the higher the ratio, the greater the company’s liquidity.

Key Term

- Treasury bills

-

Treasury bills (or T-Bills) mature in one year or less. Like zero-coupon bonds, they do not pay interest prior to maturity; instead they are sold at a discount of the par value to create a positive yield to maturity.

Quick ratio

In finance, the Acid-test (also known as quick ratio or liquid ratio) measures the ability of a company to use its near cash or quick assets to extinguish or retire its current liabilities immediately. Quick assets include those current assets that presumably can be quickly converted to cash at close to their book values. A company with a Quick Ratio of less than 1 cannot pay back its current liabilities.

Quick Ratio = (Cash and cash equivalent + Marketable securities + Accounts receivable) / Current liabilities.

Cash and cash equivalents are the most liquid assets found within the asset portion of a company’s balance sheet. Cash equivalents are assets that are readily convertible into cash, such as money market holdings, short-term government bonds or Treasury bills, marketable securities, and commercial paper. Cash equivalents are distinguished from other investments through their short-term existence. They mature within 3 months, whereas short-term investments are 12 months or less and long-term investments are any investments that mature in excess of 12 months. Another important condition that cash equivalents need to satisfy, is the investment should have insignificant risk of change in value. Thus, common stock cannot be considered a cash equivalent, but preferred stock acquired shortly before its redemption date can be.

Cash

Cash is the most liquid asset in a business.

Acid test ratio

Acid test often refers to Cash ratio instead of Quick ratio: Acid Test Ratio = (Current assets – Inventory) / Current liabilities.

Note that Inventory is excluded from the sum of assets in the Quick Ratio, but included in the Current Ratio. Ratios are tests of viability for business entities but do not give a complete picture of the business’ health. A business with large Accounts Receivable that won’t be paid for a long period (say 120 days), and essential business expenses and Accounts Payable that are due immediately, the Quick Ratio may look healthy when the business could actually run out of cash. In contrast, if the business has negotiated fast payment or cash from customers, and long terms from suppliers, it may have a very low Quick Ratio and yet be very healthy.

The acid test ratio should be 1:1 or higher, however this varies widely by industry. The higher the ratio, the greater the company’s liquidity will be (better able to meet current obligations using liquid assets).

3.6: Debt Management Ratios

3.6.1: Total Debt to Total Assets

The debt ratio is expressed as Total debt / Total assets.

Learning Objective

Use a company’s debt ratio to evaluate its financial strength

Key Points

- The debt ratio measures the firm’s ability to repay long-term debt by indicating the percentage of a company’s assets that are provided via debt.

- Debt ratio = Total debt / Total assets.

- The higher the ratio, the greater risk will be associated with the firm’s operation.

Key Terms

- goodwill

-

Goodwill is an accounting concept meaning the value of an asset owned that is intangible but has a quantifiable “prudent value” in a business for example a reputation the firm enjoyed with its clients.

- debt to total assets ratio

-

after tax income divided by liabilities

Example

- For example, a company with 2 million in total assets and 500,000 in total liabilities would have a debt ratio of 25%.

Financial Ratios

Financial ratios quantify many aspects of a business and are an integral part of the financial statement analysis. Financial ratios are categorized according to the financial aspect of the business which the ratio measures.

Financial ratios allow for comparisons:

- Between companies

- Between industries

- Between different time periods for one company

- Between a single company and its industry average

Ratios generally are not useful unless they are benchmarked against something else, like past performance or another company. Thus, the ratios of firms in different industries, which face different risks, capital requirements, and competition, are usually hard to compare.

Debt ratios

Debt

Debt ratio is an index of a business operation.

Debt ratios measure the firm’s ability to repay long-term debt. It is a financial ratio that indicates the percentage of a company’s assets that are provided via debt. It is the ratio of total debt (the sum of current liabilities and long-term liabilities) and total assets (the sum of current assets, fixed assets, and other assets such as ‘goodwill’).

- Debt ratio = Total debt / Total assets

Or alternatively:

- Debt ratio = Total liability / Total assets

The higher the ratio, the greater risk will be associated with the firm’s operation. In addition, high debt to assets ratio may indicate low borrowing capacity of a firm, which in turn will lower the firm’s financial flexibility. Like all financial ratios, a company’s debt ratio should be compared with their industry average or other competing firms.

Total liabilities divided by total assets. The debt/asset ratio shows the proportion of a company’s assets which are financed through debt. If the ratio is less than 0.5, most of the company’s assets are financed through equity. If the ratio is greater than 0.5, most of the company’s assets are financed through debt. Companies with high debt/asset ratios are said to be “highly leveraged,” not highly liquid as stated above. A company with a high debt ratio (highly leveraged) could be in danger if creditors start to demand repayment of debt.

3.6.2: Times-Interest-Earned Ratio

Times Interest Earned ratio (EBIT or EBITDA divided by total interest payable) measures a company’s ability to honor its debt payments.

Learning Objective

Use a company’s index coverage ratio to evaluate its ability to meet its debt obligations

Key Points

- Times interest earned (TIE) or Interest Coverage ratio is a measure of a company’s ability to honor its debt payments. It may be calculated as either EBIT or EBITDA divided by the total interest payable.

- Interest Charges = Traditionally “charges” refers to interest expense found on the income statement.

- EBIT = Revenue – Operating expenses (OPEX) + Non-operating income.

- EBITDA = Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization.

- Times Interest Earned or Interest Coverage is a great tool when measuring a company’s ability to meet its debt obligations.

Key Term

- Non-operating income

-

Non-operating income, in accounting and finance, is gains or losses from sources not related to the typical activities of the business or organization. Non-operating income can include gains or losses from investments, property or asset sales, currency exchange, and other atypical gains or losses.

Times interest earned (TIE), or interest coverage ratio, is a measure of a company’s ability to honor its debt payments. It may be calculated as either EBIT or EBITDA, divided by the total interest payable.

Times-Interest-Earned = EBIT or EBITDA / Interest charges

Interest

Interest rates of working capital financing can be largely affected by discount rate, WACC and cost of capital.

Times-Interest-Earned = EBIT or EBITDA / Interest charges

- Interest Charges = Traditionally “charges” refers to interest expense found on the income statement.

- EBIT = Earnings Before Interest and Taxes, also called operating profit or operating income. EBIT is a measure of a firm’s profit that excludes interest and income tax expenses. It is the difference between operating revenues and operating expenses. When a firm does not have non-operating income, then operating income is sometimes used as a synonym for EBIT and operating profit.

- EBIT = Revenue – Operating Expenses (OPEX) + Non-operating income.

- Operating income = Revenue – Operating expenses.

- EBITDA = Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization. The EBITDA of a company provides insight on the operational profitability of the business. It shows the profitability of a company regarding its present assets and operations with the products it produces and sells, taking into account possible provisions that need to be done.

If EBITDA is negative, then the business has serious issues. A positive EBITDA, however, does not automatically imply that the business generates cash. EBITDA ignores changes in Working Capital (usually needed when growing a business), capital expenditures (needed to replace assets that have broken down), taxes, and interest.

Times Interest Earned or Interest Coverage is a great tool when measuring a company’s ability to meet its debt obligations. When the interest coverage ratio is smaller than 1, the company is not generating enough cash from its operations EBIT to meet its interest obligations. The Company would then have to either use cash on hand to make up the difference or borrow funds. Typically, it is a warning sign when interest coverage falls below 2.5x.

3.7: Market Value Ratios

3.7.1: Price/Earnings Ratio

Price to earnings ratio (market price per share / annual earnings per share) is used as a guide to the relative values of companies.

Learning Objective

Calculate a company’s Price to Earnings Ratio

Key Points

- P/E ratio = Market price per share / Annual earnings per share.

- The P/E ratio is a widely used valuation multiple used as a guide to the relative values of companies; for example, a higher P/E ratio means that investors are paying more for each unit of current net income, so the stock is more expensive than one with a lower P/E ratio.

- Different types of P/E include: trailing P/E or P/E ttm, trailing P/E from continued operations, and forward P/E or P/Ef.

Key Terms

- time value of money

-

The value of money, figuring in a given amount of interest, earned over a given amount of time.

- inflation

-

An increase in the general level of prices or in the cost of living.

Example

- As an example, if stock A is trading at 24 and the earnings per share for the most recent 12 month period is three, then stock A has a P/E ratio of 24/3, or eight.

Price/Earnings Ratio

In stock trading, the price-to-earnings ratio of a share (also called its P/E, or simply “multiple”) is the market price of that share divided by the annual earnings per share (EPS).

The P/E ratio is a widely used valuation multiple used as a guide to the relative values of companies; a higher P/E ratio means that investors are paying more for each unit of current net income, so the stock is more “expensive” than one with a lower P/E ratio. The P/E ratio can be regarded as being expressed in years. The price is in currency per share, while earnings are in currency per share per year, so the P/E ratio shows the number of years of earnings that would be required to pay back the purchase price, ignoring inflation, earnings growth, and the time value of money.

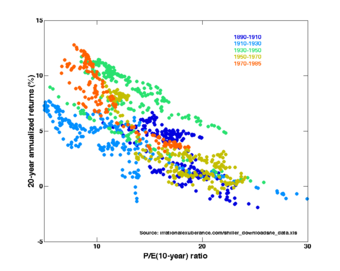

Price-Earning Ratios as a Predictor of Twenty-Year Returns

The horizontal axis shows the real price-earnings ratio of the S&P Composite Stock Price Index as computed in Irrational Exuberance (inflation adjusted price divided by the prior ten-year mean of inflation-adjusted earnings). The vertical axis shows the geometric average real annual return on investing in the S&P Composite Stock Price Index, reinvesting dividends, and selling twenty years later. Note that over the last century, as the P/E ratio has decreased, annualized returns have increased.

P/E ratio = Market price per share / Annual earnings per share

The price per share in the numerator is the market price of a single share of the stock. The earnings per share in the denominator may vary depending on the type of P/E. The types of P/E include the following:

- Trailing P/E or P/E ttm: Here, earning per share is the net income of the company for the most recent 12 month period, divided by the weighted average number of common shares in issue during the period. This is the most common meaning of P/E if no other qualifier is specified. Monthly earnings data for individual companies are not available, and usually fluctuate seasonally, so the previous four quarterly earnings reports are used, and earnings per share are updated quarterly. Note, each company chooses its own financial year so the timing of updates will vary from one to another.

- Trailing P/E from continued operations: Instead of net income, this uses operating earnings, which exclude earnings from discontinued operations, extraordinary items (e.g. one-off windfalls and write-downs), and accounting changes. Longer-term P/E data, such as Shiller’s, use net earnings.

- Forward P/E, P/Ef, or estimated P/E: Instead of net income, this uses estimated net earnings over the next 12 months. Estimates are typically derived as the mean of those published by a select group of analysts (selection criteria are rarely cited). In times of rapid economic dislocation, such estimates become less relevant as the situation changes (e.g. new economic data is published, and/or the basis of forecasts becomes obsolete) more quickly than analysts adjust their forecasts.

By comparing price and earnings per share for a company, one can analyze the market’s stock valuation of a company and its shares relative to the income the company is actually generating. Stocks with higher (or more certain) forecast earnings growth will usually have a higher P/E, and those expected to have lower (or riskier) earnings growth will usually have a lower P/E. Investors can use the P/E ratio to compare the value of stocks; for example, if one stock has a P/E twice that of another stock, all things being equal (especially the earnings growth rate), it is a less attractive investment. Companies are rarely equal, however, and comparisons between industries, companies, and time periods may be misleading. P/E ratio in general is useful for comparing valuation of peer companies in a similar sector or group.

The P/E ratio of a company is a significant focus for management in many companies and industries. Managers have strong incentives to increase stock prices, firstly as part of their fiduciary responsibilities to their companies and shareholders, but also because their performance based remuneration is usually paid in the form of company stock or options on their company’s stock (a form of payment that is supposed to align the interests of management with the interests of other stock holders). The stock price can increase in one of two ways: either through improved earnings, or through an improved multiple that the market assigns to those earnings. In turn, the primary driver for multiples such as the P/E ratio is through higher and more sustained earnings growth rates.

Companies with high P/E ratios but volatile earnings may be tempted to find ways to smooth earnings and diversify risk; this is the theory behind building conglomerates. Conversely, companies with low P/E ratios may be tempted to acquire small high growth businesses in an effort to “rebrand” their portfolio of activities and burnish their image as growth stocks and thus obtain a higher P/E rating.

3.7.2: Market/Book Ratio

The price-to-book ratio is a financial ratio used to compare a company’s current market price to its book value.

Learning Objective

Calculate the different types of price to book ratios for a company

Key Points

- The calculation can be performed in two ways: 1) the company’s market capitalization can be divided by the company’s total book value from its balance sheet, 2) using per-share values, is to divide the company’s current share price by the book value per share.

- A higher P/B ratio implies that investors expect management to create more value from a given set of assets, all else equal.

- Technically, P/B can be calculated either including or excluding intangible assets and goodwill.

Key Term

- outstanding shares

-

Shares outstanding are all the shares of a corporation that have been authorized, issued and purchased by investors and are held by them.

Price/Book Ratio

The price-to-book ratio, or P/B ratio, is a financial ratio used to compare a company’s current market price to its book value. The calculation can be performed in two ways, but the result should be the same either way.

In the first way, the company’s market capitalization can be divided by the company’s total book value from its balance sheet.

- Market Capitalization / Total Book Value

The second way, using per-share values, is to divide the company’s current share price by the book value per share (i.e. its book value divided by the number of outstanding shares).

- Share price / Book value per share

As with most ratios, it varies a fair amount by industry. Industries that require more infrastructure capital (for each dollar of profit) will usually trade at P/B ratios much lower than, for example, consulting firms. P/B ratios are commonly used to compare banks, because most assets and liabilities of banks are constantly valued at market values.

A higher P/B ratio implies that investors expect management to create more value from a given set of assets, all else equal (and/or that the market value of the firm’s assets is significantly higher than their accounting value). P/B ratios do not, however, directly provide any information on the ability of the firm to generate profits or cash for shareholders.

This ratio also gives some idea of whether an investor is paying too much for what would be left if the company went bankrupt immediately. For companies in distress, the book value is usually calculated without the intangible assets that would have no resale value. In such cases, P/B should also be calculated on a “diluted” basis, because stock options may well vest on the sale of the company, change of control, or firing of management.

It is also known as the market-to-book ratio and the price-to-equity ratio (which should not be confused with the price-to-earnings ratio), and its inverse is called the book-to-market ratio.

Total Book Value vs Tangible Book Value

Technically, P/B can be calculated either including or excluding intangible assets and goodwill. When intangible assets and goodwill are excluded, the ratio is often specified to be “price to tangible book value” or “price to tangible book”.

3.8: The DuPont Equation, ROE, ROA, and Growth

3.8.1: The DuPont Equation

The DuPont equation is an expression which breaks return on equity down into three parts: profit margin, asset turnover, and leverage.

Learning Objective

Explain why splitting the return on equity calculation into its component parts may be helpful to an analyst

Key Points

- By splitting ROE into three parts, companies can more easily understand changes in their returns on equity over time.

- As profit margin increases, every sale will bring more money to a company’s bottom line, resulting in a higher overall return on equity.

- As asset turnover increases, a company will generate more sales per asset owned, resulting in a higher overall return on equity.

- Increased financial leverage will also lead to an increase in return on equity, since using more debt financing brings on higher interest payments, which are tax deductible.

Key Term

- competitive advantage

-

something that places a company or a person above the competition

Example

- A company has sales of 1,000,000. It has a net income of 400,000. Total assets have a value of 5,000,000, and shareholder equity has a value of 10,000,000. Using DuPont analysis, what is the company’s return on equity? Profit Margin = 400,000/1,000,000 = 40%. Asset Turnover = 1,000,000/5,000,000 = 20%. Financial Leverage = 5,000,000/10,000,000 = 50%. Multiplying these three results, we find that the Return on Equity = 4%.

The DuPont Equation

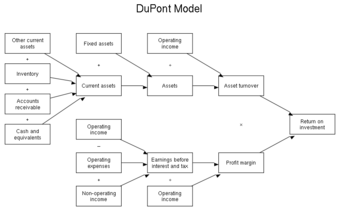

DuPont Model

A flow chart representation of the DuPont Model.

The DuPont equation is an expression which breaks return on equity down into three parts. The name comes from the DuPont Corporation, which created and implemented this formula into their business operations in the 1920s. This formula is known by many other names, including DuPont analysis, DuPont identity, the DuPont model, the DuPont method, or the strategic profit model.

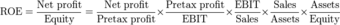

The DuPont Equation

In the DuPont equation, ROE is equal to profit margin multiplied by asset turnover multiplied by financial leverage.

Under DuPont analysis, return on equity is equal to the profit margin multiplied by asset turnover multiplied by financial leverage. By splitting ROE (return on equity) into three parts, companies can more easily understand changes in their ROE over time.

Components of the DuPont Equation: Profit Margin

Profit margin is a measure of profitability. It is an indicator of a company’s pricing strategies and how well the company controls costs. Profit margin is calculated by finding the net profit as a percentage of the total revenue. As one feature of the DuPont equation, if the profit margin of a company increases, every sale will bring more money to a company’s bottom line, resulting in a higher overall return on equity.

Components of the DuPont Equation: Asset Turnover

Asset turnover is a financial ratio that measures how efficiently a company uses its assets to generate sales revenue or sales income for the company. Companies with low profit margins tend to have high asset turnover, while those with high profit margins tend to have low asset turnover. Similar to profit margin, if asset turnover increases, a company will generate more sales per asset owned, once again resulting in a higher overall return on equity.

Components of the DuPont Equation: Financial Leverage

Financial leverage refers to the amount of debt that a company utilizes to finance its operations, as compared with the amount of equity that the company utilizes. As was the case with asset turnover and profit margin, Increased financial leverage will also lead to an increase in return on equity. This is because the increased use of debt as financing will cause a company to have higher interest payments, which are tax deductible. Because dividend payments are not tax deductible, maintaining a high proportion of debt in a company’s capital structure leads to a higher return on equity.

The DuPont Equation in Relation to Industries

The DuPont equation is less useful for some industries, that do not use certain concepts or for which the concepts are less meaningful. On the other hand, some industries may rely on a single factor of the DuPont equation more than others. Thus, the equation allows analysts to determine which of the factors is dominant in relation to a company’s return on equity. For example, certain types of high turnover industries, such as retail stores, may have very low profit margins on sales and relatively low financial leverage. In industries such as these, the measure of asset turnover is much more important.

High margin industries, on the other hand, such as fashion, may derive a substantial portion of their competitive advantage from selling at a higher margin. For high end fashion and other luxury brands, increasing sales without sacrificing margin may be critical. Finally, some industries, such as those in the financial sector, chiefly rely on high leverage to generate an acceptable return on equity. While a high level of leverage could be seen as too risky from some perspectives, DuPont analysis enables third parties to compare that leverage with other financial elements that can determine a company’s return on equity.

3.8.2: ROE and Potential Limitations

Return on equity measures the rate of return on the ownership interest of a business and is irrelevant if earnings are not reinvested or distributed.

Learning Objective

Calculate a company’s return on equity

Key Points

- Return on equity is an indication of how well a company uses investment funds to generate earnings growth.

- Returns on equity between 15% and 20% are generally considered to be acceptable.

- Return on equity is equal to net income (after preferred stock dividends but before common stock dividends) divided by total shareholder equity (excluding preferred shares).

- Stock prices are most strongly determined by earnings per share (EPS) as opposed to return on equity.

Key Term

- fundamental analysis

-

An analysis of a business with the goal of financial projections in terms of income statement, financial statements and health, management and competitive advantages, and competitors and markets.

Example

- A small business’ net income after taxes is $10,000. The total shareholder equity in the business is $50,000. What is the return on equity? ROE = 10,000/50,000 ROE = 20%

Return On Equity

Return on equity (ROE) measures the rate of return on the ownership interest or shareholders’ equity of the common stock owners. It is a measure of a company’s efficiency at generating profits using the shareholders’ stake of equity in the business. In other words, return on equity is an indication of how well a company uses investment funds to generate earnings growth. It is also commonly used as a target for executive compensation, since ratios such as ROE tend to give management an incentive to perform better. Returns on equity between 15% and 20% are generally considered to be acceptable.

The Formula

Return on equity is equal to net income, after preferred stock dividends but before common stock dividends, divided by total shareholder equity and excluding preferred shares.

Return On Equity

ROE is equal to after-tax net income divided by total shareholder equity.

Expressed as a percentage, return on equity is best used to compare companies in the same industry. The decomposition of return on equity into its various factors presents various ratios useful to companies in fundamental analysis.

ROE Broken Down

This is an expression of return on equity decomposed into its various factors.