18.1: Ratio Analysis and Statement Evaluation

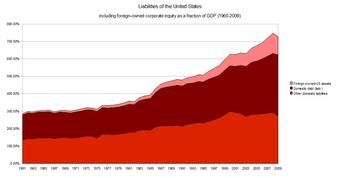

18.1.1: Financial Statements Across Periods

Companies prepare three financial statements according to GAAP rules: the income statement, the balance sheet, and the cash flow statement.

Learning Objective

Identify the three main financial statements that companies generally submit

Key Points

- The income statement gives an account of what the company sold and spent in the year (revenues and expenses).

- The balance sheet is a financial snapshot of the company’s assets and liabilities, and informs shareholders about its financial health.

- The cash flow statement shows what came into and went out of the company in cash. It gives a better idea than the other two financial statements about how well the company can meet its cash obligations.

- The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulates these financial statements. Companies must file extensive reports annually (known as a 10K), as well as quarterly reports (10Q).

- A company may report its financials in a fiscal year that is different from the calendar year.

Key Terms

- 10Q

-

A quarterly report mandated by the United States federal Securities and Exchange Commission to be filed by publicly traded corporations.

- generally accepted accounting principles

-

The standard framework of guidelines for financial accounting used in any given jurisdiction; generally known as accounting standards. GAAP includes the standards, conventions, and rules accountants follow in recording and summarizing, and in the preparation of financial statements.

- 10K

-

An annual report, required by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), that gives a comprehensive summary of a public company’s performance.

Example

- Publicly traded companies must make their financial statements available for all to see. These can be found on a financial website, such as finance.yahoo.com.

Financial statements are records that outline the financial activities of a business, individual, or any other entity . Corporations report financial statements following Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). The rules about how financial statements should be put together are set by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). Standardized rules ensure, to some extent, that a firm’s financial statements accurately represent the company’s financial status.

Financial Statements Analysis

Corporations report financial statements following Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

Companies generally submit three forms of financial statements. The information contained in these statements, and how this information fluctuates across periods, is very telling for investors and government regulatory agencies. These three financial statements are:

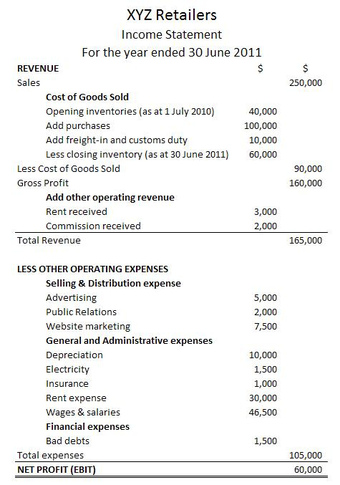

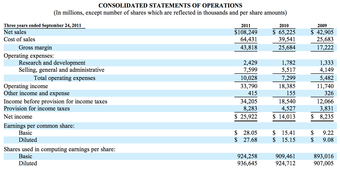

The income statement (also called the “profit and loss statement”): This gives an account of what the company sold and spent in the year. Sales (also called “revenues”), or what the company sold in products and services, less any expenses (expenses are divided into a number of categories) and less taxes, gives the company’s income. The income statement summarizes all this type of activity for the year.

The balance sheet: This is a financial snapshot of what the company owns (assets), what it owes (liabilities), and its worth free and clear of debt (or the value of its equity). Analyzing a balance sheet informs shareholders about the company’s financial health.

The cash flow statement: It tells what transactions went into and came out of the company in the form of cash. This is necessary because accounting sometimes deals with revenues and expenses which are not real cash, such as accounts receivable and accounts payable. Looking at the actual cash flow gives a better idea of how well the company can meet its cash obligations.

The period represented in a given financial statement can vary. A company may report its financials in a fiscal year that is different from the calendar year. While some firms do follow the calendar year, others–such as retail companies–prefer not to follow the calendar year due to seasonality of sales or expenses, et cetera.

The reporting of these financial statements is regulated by the federal agency, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). According to SEC regulations, companies have to file an extensive report (called the 10K) on what happened during the year. In addition to the 10K, companies have to file 10Qs every three months, which give their quarterly financial performance. These reports can be accessed through the SEC’s website, www.sec.gov, the company’s website, or various financial websites, such as finance.yahoo.com.

18.1.2: Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios are used to assess a business’s ability to generate earnings.

Learning Objective

Compare the information given by calculating the various profitability ratios

Key Points

- Profitability ratios are used to compare companies in the same industry, since profit margins will vary widely from industry to industry.

- Taxes should not be included in these ratios, since tax rates will vary from company to company.

- The profit margin shows the relationship between profit and sales and is mostly used for internal comparison.

- Profit Margin = Net Profit / Net Sales. It shows the relationship between profit and sales and is mostly used for internal comparison.

- ROE = Net Income / Shareholder Equity. It measures a firm’s efficiency at generating profits from every unit of shareholders’ equity.

- The BEP ratio compares earnings before income and taxes to total assets. BEP = EBIT / Total Assets.

Key Terms

- financial leverage

-

The degree to which an investor or business is utilizing borrowed money.

- Cost of Goods Sold

-

Cost of goods sold (COGS) refer to the inventory costs of those goods a business has sold during a particular period.

- profitability

-

The capacity to make a profit.

Example

- Company A had a net income last year of ten thousand dollars. It operated with two thousand five hundred dollars worth of assets. Thus, its ROA = 10000 / 2500 = 4. Therefore, it derives four dollars for each dollar of assets it owns. In that time, its net sales were fifty thousand dollars. Thus, the Profit Margin = 10000 / 50000 = 20 percent. This figure should be compared to its competitors in order to determine whether this is healthy or not.

Profitability Ratios

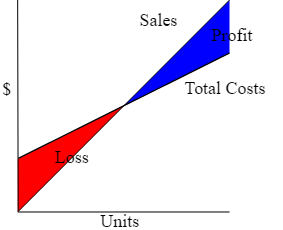

Profitability ratios show how much profit the company takes in for every dollar of sales or revenues. They are used to assess a business’s ability to generate earnings as compared to expenses over a specified time period .

Increasing Profits

Profitability ratios are used to assess a business’s ability to generate earnings.

Profitability ratios are going to vary from industry to industry, so comparisons should be between other companies in the same field. When comparing companies in the same industry, the company with the higher profit margin is able to sell at a higher price or lower expenses. They tend to be more attractive to investors.

Net Profit Margins and Returns on Sales

Many analysts focus on net profit margins or returns on sales, which are calculated by taking the net income after taxes and dividing by the revenues or sales. This ratio uses the bottom line on the income statement to calculate profit for every dollar of sales or revenues. The operating margin takes the profit before taxes further up the income statement and divides by revenues. Operating margins are also important, since they focus on the operating income and operating expenses. Other profitability ratios include:

- Return on Assets: The return on assets ratio (ROA) is found by dividing the net income by total assets. The higher the ratio, the better the company is at using their assets to generate income (i.e., how many dollars of earnings they derive from each dollar of assets they control). It is also a measure of how much the company relies on assets to generate profit. The return on assets gives an indication of the company’s capital intensity, which will depend on the industry. Companies that require large initial investments will generally have reduced return on assets.

- Profit Margin: The profit margin is one of the most used profitability ratios. The profit margin refers to the amount of profit that a company earns through sales. The profit margin ratio is broadly the ratio of profit to total sales times one hundred percent. The higher the profit margin, the more profit a company earns on each sale. The profit margin is mostly used for internal comparison. It is difficult to accurately compare the net profit ratio for different entities. A low profit margin indicates a low margin of safety and a higher risk that a decline in sales will erase profits and result in a net loss or a negative margin.

- Return on Equity: The return on equity (ROE) measures profitability related to ownership. It measures a firm’s efficiency at generating profits from every unit of the shareholders’ equity. ROEs between 15 percent and 20 percent are generally considered good. The ROE is equal to the net income divided by the shareholder equity.

- Basic Earning Power Ratio: The basic earning power ratio (or BEP ratio) compares earnings separately from the influence of taxes or financial leverage to the assets of the company. The BEP is equal to the earnings before interest and taxes divided by the total assets. The BEP differs from the ROA in that it includes the non-operating income.

- Gross Profit Ratio: This indicates what portion of each sales dollar is available to meet expenses and generate profit after taking into account the cost of goods sold. Generally, it is calculated as the selling price of an item minus the cost of goods sold (production or acquisition costs).

18.1.3: Liquidity Ratios

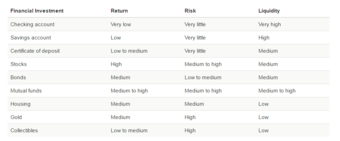

Liquidity ratios measure how quickly assets can be turned into cash in order to pay the company’s short-term obligations.

Learning Objective

Compare the current ratio to the quick ratio

Key Points

- Liquidity ratios should fall within a certain range—too low and the company cannot pay off its obligations, or too high and the company is not utilizing its cash efficiently.

- Current Ratio = Current Assets / Current Liabilities. This ratio examines whether a firm can cover its short-term debts. If below 1, the company may have difficulty meeting short-term obligations.

- Acid Test Ratio (or Quick Ratio) = [Current Assets – Inventories] / Current Liabilities. More stringent and meaningful than the Current Ratio, since it does not include inventory. A ratio of 1:1 is recommended, but not necessarily a minimum.

- A company can improve its liquidity ratios by raising the value of its current assets, reducing current liabilities by paying off debt, or negotiating delayed payments to creditors.

Key Terms

- liquidity ratio

-

total cash and equivalents divided by short-term borrowings

- liquidity

-

An asset’s ability to become solvent without affecting its value; the degree to which it can be easily converted into cash.

- creditor

-

A person to whom a debt is owed.

Example

- Company X has $1,000 dollars in cash, and $2,000 worth of inventory to be sold. Company X owed Company Y $1,000 dollars. X’s Current Ratio = 3000 / 1,000 = 3, and so can be considered healthy. X’s Acid Test Ratio = 1,000 / 1,000 = 1, which means that it can pay off short-term obligations. It is also not too high, and so cash is not idle.

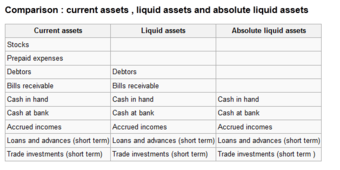

Liquidity ratios measure a company’s ability to pay short-term obligations of one year or less (i.e., how quickly assets can be turned into cash). A high liquidity ratio indicates that a business is holding too much cash that could be utilized in other areas. A low liquidity ratio means a firm may struggle to pay short-term obligations.

One such ratio is known as the current ratio, which is equal to:

Current Assets ÷ Current Liabilities.

This ratio reveals whether the firm can cover its short-term debts; it is an indication of a firm’s market liquidity and ability to meet creditor’s demands. Acceptable current ratios vary from industry to industry. For a healthy business, a current ratio will generally fall between 1.5 and 3. If current liabilities exceed current assets (i.e., the current ratio is below 1), then the company may have problems meeting its short-term obligations. If the current ratio is too high, the company may be inefficiently using its current assets or its short-term financing facilities. This may also indicate problems in working capital management.

The acid test ratio (or quick ratio) is similar to current ratio except in that it ignores inventories. It is equal to:

(Current Assets – Inventories) Current Liabilities.

Typically the quick ratio is more meaningful than the current ratio because inventory cannot always be relied upon to convert to cash. A ratio of 1:1 is recommended. Low values for the current or quick ratios (values less than 1) indicate that a firm may have difficulty meeting current obligations. Low values, however, do not indicate a critical problem. If an organization has good long-term prospects, it may be able to borrow against those prospects to meet current obligations.

A firm may improve its liquidity ratios by raising the value of its current assets, reducing the value of current liabilities, or negotiating delayed or lower payments to creditors.

Cash

Cash is the most liquid asset in a business.

18.1.4: Debt Utilization Ratios

Debt ratios provide information about a company’s long-term financial health.

Learning Objective

Explain the methods and usage of debt utilization ratios

Key Points

- Generally speaking, the more debt a company has (as a percentage of assets), the less healthy it is financially.

- Debt Ratio = Total Debt / Total Assets. It shows the percentage of a company’s assets that are provided through debt. The higher the ratio, the greater the risk the company has undertaken.

- Debt-to-Equity Ratio (D/E) = Debt (i.e. Liabilities) / Equity. It shows the split of shareholders’ equity and debt that are used to finance the company’s assets.

- The DCR shows the ratio of cash available for debt servicing to interest, principal, and lease payments. The higher this ratio, the easier it is for a company to take on new debt.

Key Terms

- debt financing

-

funding obtained by borrowing assets

- amortization

-

The reduction of loan principle over a series of payments.

- debt

-

Money that one person or entity owes or is required to pay to another, generally as a result of a loan or other financial transaction.

- Interest

-

The price paid for obtaining or price received for providing money or goods in a credit transaction, calculated as a fraction of the amount or value of what was borrowed.

Example

- If Company F has $100,000 in assets, and $10,000 in total liabilities, it would have a debt ratio of 10,000 / 100,000 = 10%. Company G, on the other hand, may have $100,000 worth of assets and $200,000 worth of liabilities. In this case, it has a debt ratio of 200%.

Debt utilization ratios provide a comprehensive picture of the company’s solvency or long-term financial health. The debt ratio is a financial ratio that indicates the percentage of a company’s assets that are provided via debt. It is the ratio of total debt (the sum of current liabilities and long-term liabilities) and total assets (the sum of current assets, fixed assets, and other assets such as “goodwill”).

Debt Ratio = Total Debt / Total Assets

For example, a company with $2 million in total assets and $500,000 in total liabilities would have a debt ratio of 25%. The higher the ratio, the greater the risk associated with the firm’s operation. In addition, high debt to assets ratio may indicate low borrowing capacity of a firm, which in turn will lower the firm’s financial flexibility. Like all financial ratios, a company’s debt ratio should be compared with their industry average or other competing firms.

The debt-to-equity ratio (D/E) is a financial ratio indicating the relative proportion of shareholders’ equity and debt used to finance a company’s assets. When used to calculate a company’s financial leverage, the debt usually includes only the Long Term Debt (LTD). D/E = Debt(liabilities)/Equity.

The debt service coverage ratio (DSCR), also known as debt coverage ratio (DCR), is the ratio of cash available for debt servicing to interest, principal, and lease payments. It is a popular benchmark used in the measurement of an entity’s ability to produce enough cash to cover its debt (including lease) payments. The higher this ratio is, the easier it is to obtain a loan. In general, it is calculated as:

DSCR = (Annual Net Income +

Amortization

/

Depreciation

+ Interest

Expense

+ other non-cash and discretionary items (such as non-contractual

management

bonuses)) / (Principal Repayment + Interest payments + Lease payments)

A similar debt utilization ratio is the times interest earned (TIE), or interest coverage ratio. It is a measure of a company’s ability to honor its debt payments. It may be calculated as either EBIT or EBITDA, divided by the total interest payable. EBIT is earnings before interest and taxes, and EBITDA is earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization.

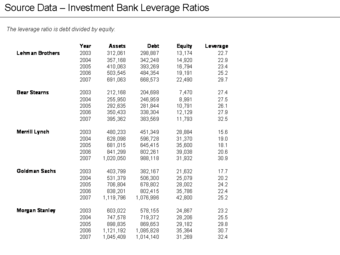

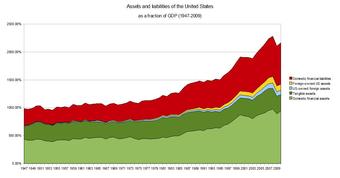

Leverage Ratios

Leverage ratios for some investment banks

18.1.5: Comparisons Within an Industry

Most financial ratios have no universal benchmarks, so meaningful analysis involves comparisons with competitors and industry averages.

Learning Objective

Explain how to effectively use financial statement analysis

Key Points

- Ratios allow easier comparison between companies than using absolute values of certain measures. They negate the impact of scale in profitability or solvency.

- Firms should generally try to meet or exceed the industry average, over time, in their ratios.

- Industry trends, changes in price levels, and future economic conditions should all be considered when using financial ratios to analyze a firm’s performance.

Key Terms

- solvency

-

The state of having enough funds or liquid assets to pay all of one’s debts; the state of being solvent.

- bankruptcy

-

A legally declared or recognized condition of insolvency of a person or organization.

Example

- Suppose Company Z has $100,000 in assets and $40,000 in total liabilities, it would have a debt ratio of 40,000 / 100,000 = 40%. If the industry average is 50%, then Company Z is in a good financial position debt-wise. Alternatively, if the industry average over time is only 25%, then Company Z should consider ways to reduce its debt.

Financial statement analysis (or financial analysis) is the process of reviewing and analyzing a company’s financial statements to make better economic decisions. These statements include the income statement, balance sheet, statement of cash flows, and a statement of retained earnings. Financial statement analysis is a method or process involving specific techniques for evaluating risks, performance, financial health, and future prospects of an organization.

Financial statements can reveal much more information when comparisons are made with previous statements, rather than when considered individually. Horizontal analysis compares financial data, such as an income statements, over a period of several quarters or years. When comparing past and present financial information, one will want to look for variations such as higher or lower earnings. Moreover, it is often useful to compare the financial statements of companies in related industries.

Ratios of risk such as the current ratio, the interest coverage, and the equity percentage have no theoretical benchmarks. It is, therefore, common to compare them with the industry average over time. If a firm has a higher equity ratio than the industry, this is considered less risky than if it is below the average. Similarly, if the equity ratio increases over time, it is a good sign in relation to insolvency risk.

The main purpose of conducting financial analysis is to measure a business’s profitability and solvency. The actual metrics tracked and methods applied vary from stakeholder to stakeholder, depending on his or her interests and needs. For example, equity investors are interested in the long-term earnings power of the organization and perhaps the sustainability and growth of dividend payments. Creditors want to ensure the interest and principal is paid on the organizations debt securities (e.g., bonds) when due.

Most analytical measures are expressed as percentages or ratios, which allows for easy comparison with other businesses in the industry regardless of absolute company size. Vertical analysis, which is a proportional analysis of financial statements, lists each line item in the financial statement as the percentage of another line item. For example, on an income statement each line item will be listed as a percentage of gross sales. This technique is also referred to as normalization or common-sizing.

When using these analytical measures, one should take the following factors into consideration:

- Industry trends;

- Changes in price levels;

- Future economic conditions.

Ratios must be compared with other firms in the same industry to see if they are in line .

Refining Operation

Ratio analyses can be used to compare between companies within the same industry. For example, comparing the ratios of BP and Exxon Mobil would be appropriate, whereas comparing the ratios of BP and General Mills would be inappropriate.

18.1.6: Performance per Share

Valuation ratios describe the value of shares to shareholders, and include the EPS ratio, the P/E ratio, and the dividend yield ratio.

Learning Objective

Identify the ratio analysis tools used for shares of stock

Key Points

- EPS (Earnings Per Share) = Net Income / Average Common Shares. This ratio gives the earnings per outstanding share of a company’s stock.

- P/E Ratio = Market Price per Share / Annual Earnings per Share. This ratio is widely used to measure the relative value of companies. The higher the P/E ratio, the more investors are paying for each unit of net income.

- Current Dividend Yield = Most Recent Full Year Dividend / Current Share Price. Displays the earnings distributed to stock holders in relation to the value of the stock.

- Market To Book ratio is used to compare a company’s current market price to its book value.

Key Terms

- stockholder

-

One who owns stock.

- dividend

-

A pro rata payment of money by a company to its shareholders, usually made periodically (e.g., quarterly or annually).

Company Performance Per Share

The below ratios describe the value of shares of stock to stockholders, both in terms of dividends and their general ownership value:

- Earnings Per Share (EPS) is the amount of earnings per each outstanding share of a company’s stock. Companies are required to report EPS for each of the major categories of the income statement, including: continuing operations, discontinued operations, extraordinary items, and net income. EPS = Net Income / Average Common Shares.

- Price to Earnings (P/E) ratio relates market price to earnings per share. The P/E ratio is a widely used metric used for measuring the relative value of companies. A higher P/E ratio means that investors are paying more for each unit of net income; therefore, the stock is more expensive compared to one with a lower P/E ratio. The P/E ratio also shows the number of years of earnings which would be required to pay back the purchase price—ignoring inflation, earnings growth and the time value of money. P/E Ratio = Market Price Per Share / Annual Earnings Per Share .

- Dividend Yield ratio shows the earnings distributed to stockholders related to the value of the stock, as calculated on a per-share basis. The dividend yield or the dividend-price ratio of a share is the company’s total annual dividend payments divided by its market capitalization—or the dividend per share, divided by the price per share. It is often expressed as a percentage. Current Dividend Yield = Most Recent Full Year Dividend / Current Share Price.

- Dividend Payout ratio shows the portion of earnings distributed to stockholders. Dividend payout ratio is the fraction of net income a firm pays to its stockholders in dividends: Dividend Payout Ratio = Dividends / Net Income for the Same Period. The part of earnings not paid to investors is left for investment to provide for future earnings growth. Investors seeking high current income and limited capital growth prefer companies with a high dividend payout ratio. However, investors seeking capital growth may prefer a lower payout ratio, because capital gains are taxed at a lower rate. High growth firms in early life generally have low or zero payout ratios. As they mature, they tend to return more of the earnings back to investors.

- Market To Book ratio is used to compare a company’s current market price to its book value. The calculation can be performed in two ways, but the result should be the same using either method. In the first method, the company’s market capitalization can be divided by the company’s total book value from its balance sheet (Market Capitalization / Total Book Value). The second method, using per-share values, is to divide the company’s current share price by the book value per share, which is its book value divided by the number of outstanding shares (Share Price / Book Value Per Share). A higher market to book ratio implies that investors expect management to create more value from a given set of assets, all else equal. This ratio also gives some idea of whether an investor is paying too much for what would be left if the company went bankrupt immediately.

18.1.7: Activity Ratios

Activity ratios provide useful insights regarding an organization’s ability to leverage existing assets efficiently.

Learning Objective

Calculate activity ratios to determine organizational efficiency

Key Points

- Organizations are largely systems of assets that produce outputs. The efficiency of how those assets are used can be measured via activity ratios.

- There are a number of different activity ratios commonly used by stakeholders and managers to assess overall organizational efficiency, most importantly asset turnover, inventory turnover, and degree of operating leverage.

- Different businesses and industries tend to focus more on some activity ratios than others. Knowing what ratio is relevant based on the operation or process is an important consideration for managerial accountants.

- Inventory turnover is highly relevant for industries selling perishable or time sensitive goods. On the other hand, manufacturing facilities tend to be more concerned with fixed asset turnover.

Key Terms

- leverage

-

To use in such a way to capture maximum value.

- perishable

-

A good that has an expiration date, or can go bad.

Why Firms Measure Activity

Activity ratios are essentially indicators of how a given organization leverages their existing assets to generate value. When considering the nature of a business, the general concept is to generate value through utilizing various production processes, employee talent, and intellectual property. Through identifying the profit compared to the investment in these core assets, the overall efficiency of the organization’s utilization can be derived.

How to Measure Activity

There are a number of ways to measure activity. Each calculation has different inputs and different implications. Some examples include:

- Average collection period – (Accounts Receivable)/(Daily Average Credit Sales)

- Degree of Operating Leverage (DOL) – (Percent Change in Net Operating Income)/(Percent Change in Sales)

- DSO Ratio – (Accounts Receivable)/(Daily Average Sales)

- Average Payment Period – (Accounts Payable)/(Average Daily Credit Purchases)

- Asset Turnover – (Net Sales)/(Total Assets)

- Stock Turnover Ratio – (Cost of Goods Sold)/(Average Inventory)

- Receivables Turnover Ratio – (Net Credit Sales)/(Average Net Receivables)

- Inventory Conversion Ratio – (365 Days)/(Inventory Turnover)

- Receivables Conversion Period – (Receivables/Net Sales)(365 Days)

- Payable Conversion Period – (Receivables/Net Sales)(365 Days)

- Cash Conversion Cycle – Inventory Conversion Period + Receivable Conversion Period – Payable Conversion Period

Using Activity Ratios

By tracking these metrics over time, and comparing them to the competition, organizations and stakeholders can gauge their competitiveness and overall capacity to leverage assets in the current industry. Understanding how to use these ratios, and what the implications are, is central to financial and managerial accounting at the strategic level.

For some business, inventory turnover is an incredibly important metric. A business selling farmed produce, for example, must have a highly sophisticated value chain with minimal warehousing and storage. Inventory turnover must be rapid, as the goods being sold are perishable. Fashion industries are similarly reliant on inventory turnover, as the seasonality of both fashion styles and climate create a strong necessity for careful activity management.

For other businesses, asset turnover is a central activity metric. A manufacturing facility producing semiconductors, for example, will invest heavily in the production facility and related equipment. Ensuring maximum production and annual sales contracts is integral to maintaining profitability, and maximizing utilization of those fixed assets will enormously impact profitability.

18.1.8: Sample Evaluation

Most of the ratios discussed can be calculated using information found in the three main financial statements.

Learning Objective

Apply financial ratio analysis to Bounded Inc.

Key Points

- Keep in mind that for most ratios, the number must be compared against competitors and industry standards for it to be meaningful.

- The ROE (Return on Equity) measures the firm’s ability to generate profits from every unit of shareholder equity.

- ROEs between 15 percent and 20 percent are generally considered good.

Key Term

- ROA

-

The return on assets (ROA) percentage shows how profitable a company’s assets are in generating revenue.

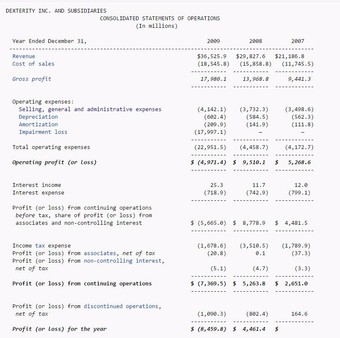

Consider the company Bounded Inc., a magazine publisher, to illustrate the financials of a company. The following information is based on the company’s FY (financial year) 2011 performance:

- Cash: $3,230

- Cost of Goods Sold: $2,390

- Current Assets: $1,000

- Current Liabilities: $3,500

- Depreciation: $800

- Fixed Assets: $8,600

- Interest Payments: $300

- Inventory: $2,010

- Long-term Debt: $3,000

- Sales: $5,000

Using the information above, we can compile the balance sheet and the income statement. We can also calculate some financial ratios to determine the company’s financial situation. Keep in mind that for most ratios, the number must be compared against competitors and industry standards for it to be meaningful:

ROA (Return on Assets) = Net Income / Total Assets = 1,057 / 13,840 = 7.6%

This means that for every dollar of assets the company controls, it derives $0.076 of profit. This would need to be compared to others in the same industry to determine whether this is a high or low figure.

Profit Margin = Net Income / Net Sales = 1,057/5,000 = 21.1 percent

This figure would need to be compared to competitors. A lower profit margin indicates a low margin of safety.

ROE (Return on Equity) = Net Income / Shareholder Equity = 1,057/7,340 = 14.4 percent

The ROE measures the firm’s ability to generate profits from every unit of shareholder equity. 0.144 (or 14 percent) is not a bad figure, but by no means a very good once, since ROE’s between 15 to 20 percent are generally considered good.

BEP Ratio = EBIT / Total Assets = 1,810/13,840 = 0.311

Current Ratio = Current Assets / Current Liabilities = 5,240/3,500 = 1.497

This demonstrates that the company does not seem to be in a tight position in terms of liquidity.

Quick Ratio = (Current Assets-Inventories) / Current Liabilities = (5,240 – 2,010) / 3,500 = 0.923

Despite having a current ratio of about 1.0, the quick ratio is slightly below 1.0. This means that the company may face liquidity problems should payment of current liabilities be demanded immediately. But it does not seem to be a huge cause for concern.

Debt Ratio = Total Debt / Total Assets = 6,500/13,840 = 47 percent

This indicates the percentage of a company’s assets that are provided via debt. The higher the ratio, the greater risk will be associated with the firm’s operation.

D/E Ratio = Long-term Debt/Equity = 3,000/7,340 = 40.9 percent

This shows the relative proportion of shareholders’ equity and debt used to finance a company’s assets. Once again, comparisons should be made between companies in the same industry in order to determine whether this is a low or high figure.

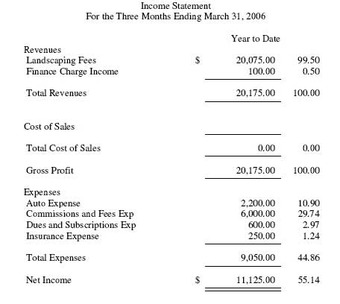

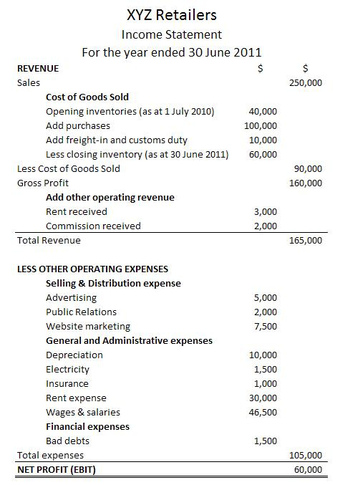

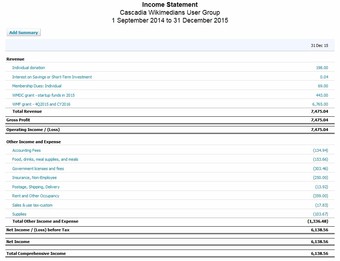

Financial Statement

One form of financial statement is the income statement.

18.2: Accounting Information

18.2.1: Usage of Accounting Information

Accounting is the vehicle for reporting financial information about a business entity to many different groups of people.

Learning Objective

Explain the history of accounting and how accounting information is useful

Key Points

- The American Accounting Association defines accounting as “the process of identifying, measuring and communicating economic information to permit informed judgements and decisions by users of the information.”

- Accounting involves two main elements: (1) an information process summarizing financial events; and (2) a reporting system that communicates financial information to interested parties.

- Double-entry bookkeeping first emerged in Northern Italy in the 14th century, where trading ventures began to require transactions that involved more than one investor.

- Management (or internal) accounting and financial (or external) accounting are generally the two key branches of accounting.

- Management accounting provides relevant and useful information to people inside the business, such as employees, managers, owners and auditors. It provides information for decision making and company strategy.

- Financial accounting, on the other hand, also provides information to people outside the business, such as investors, regulators, analysts, economists, and government agencies.

Key Terms

- double-entry bookkeeping

-

A method of bookkeeping in which each transaction must have at least one debit and one credit.

- Financial statements

-

Standardized documents that include the financial information of a person, company, government, or organization; this information is used to make financial decisions.

- accounting

-

The process of identifying, measuring and communicating economic information to permit informed judgements and decisions by users of the information. (definition by the American Accounting Association)

- stakeholders

-

People outside of a company who have a special interest in the company. Some examples are suppliers, customers, and the community.

Using Accounting Information

The American Accounting Association defines accounting as “the process of identifying, measuring and communicating economic information to permit informed judgements and decisions by users of the information.” In other words, it is the process of communicating financial information about a business entity to stakeholders and managers. Economic information is generally displayed in the form of financial statements that show the economic resources that a business currently has; the goal of the business is to determine which information is useful to the outside world.

Accounting involves two main elements:

- An information process that identifies, classifies and summarizes the financial events that take place within an organization

- A reporting system that communicates relevant financial information to interested persons, allowing them to assess performance, make decisions, and/or control the economic resources in the organization.

It is important to note that accounting is not the end of the decision making process; it provides the most relevant and reliable information possible to allow for goals to be developed, implemented, and revised.

Accounting History

Early accounts served mainly to assist a businessperson in recalling financial transactions. The proprietor or record keeper was usually the only person to see this information. Cruder forms of accounting were inadequate when a business needed multiple investors. As a result, double-entry bookkeeping first emerged in northern Italy in the 14th century, where trading ventures began to require more capital than a single individual was able to invest.

The development of joint stock companies created wider audiences for accounts, as investors without firsthand knowledge of their operations relied on accounts to provide additional information. This development resulted in the division of accounting systems for internal (i.e. management accounting) and external (i.e. financial accounting) purposes. This also led to the separation of internal and external accounting and disclosure regulations.

Accounting Today

Today, accounting is referred to as “the language of business” because it is the vehicle for reporting financial information about a business entity to many different groups of people. Accounting that concentrates on reporting to people inside the business entity is called management accounting. It is used to provide information to employees, managers, and auditors. Management accounting is concerned primarily with providing a basis for making management or operating decisions.

Accounting that provides information to people outside the business entity is called financial accounting. It provides information to present and potential shareholders, creditors, vendors, financial analysts, and government agencies. Because these users have different needs, the presentation of financial accounts is very structured and subject to many more rules than management accounting. The body of rules that governs financial accounting is called Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, or GAAP. The International Financial Reporting Standards, or IFRS, provides another set of accounting rules.

Accounting

Accounting allows a business to track its financial information.

18.2.2: Managerial Accounting

Through integrating accounting knowledge with strategic decision-making, organizations can improve performance, refine strategy, and mitigate risk.

Learning Objective

Integrate a knowledge of accounting with its impact on strategic decision-making

Key Points

- Through utilizing managerial accounting perspectives, strategic managers can vastly improve their understanding of performance and recognize areas of potential improvement.

- One critical difference between financial and managerial accounting is that managerial accounting is designed to flexibly align to current operations, while financial accounting sticks to global formats.

- Another key difference between financial and managerial accounting is chronological focal point. Managerial accounting is forward-looking, while financial accounting tends to look at the past.

- A few examples of managerial accounting include cost benefit analysis, life cycle costs, developing new business metrics, and geographically segmented reporting.

Key Terms

- financial accounting

-

Accounting that focuses on preparation of stakeholder documents (particularly for publicly traded companies) and collecting data on past operational performance.

- managerial accounting

-

Accounting that combines strategic decision-making with accounting knowledge through providing specific tools to measure the financial implications of various internal activities.

Management accounting is one of the most interesting and broad-minded applications of the accounting perspective. There exists a strong relationship between the knowledge accounting delivers to managerial teams, and the strategic and tactical decisions made by management. Through this integration, organizations can improve their decision-making to strategic value in the form of improved performance and mitigated risks.

Differentiating Managerial Accounting

When looking at traditional financial accounting, managerial accounting differs in a few key ways:

- For public organizations, a variety of reports are released quarterly and annually for stakeholders. Managerial accounting creates additional documents used for internal, strategic decision-making.

- Financial accounting is generally historical, while managerial accounting is about forecasting.

- Managerial accounting tends to lean a bit more on abstraction, utilizing various models to support financial decisions.

- While financial accounting fits the mold expected by stakeholders, managerial accounting is flexible and strives to meet the needs of management exclusively.

- Financial accounting looks at the company holistically, while financial accounting can zoom in at various levels (i.e. product level, division level, etc.)

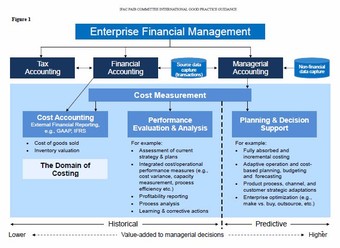

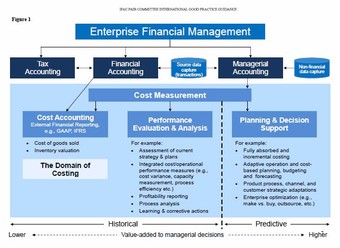

Differences between Financial and Managerial Accounting

This is a great image depicting the various differences in perspective found between different accounting methodologies. Looking at managerial accounting in this diagram, one can better understand its place in the organization.

Examples of Managerial Accounting

There are countless specific examples of managerial accounting practices. Taking a look at a few will provide additional scope and perspective on the field:

Throughput Accounting: Production processes have a great deal of inter-dependency. This can create opportunity costs, as interdependent resources are being restrained. Measuring the contribution per unit of constrained resource is called throughput accounting.

Lean Accounting: During the days when the Toyota Production System was just becoming celebrated as a leaner process, accountants began to consider the restrictions of traditional accounting methods on lean processes. As a result, managerial accounts began constructing a better way to measure just-in-time manufacturing process success.

Some simpler examples of common managerial accounting tasks include developing business metrics, cost-benefit analyses, IT cost transparency, life cycle cost analysis, strategic management advice, sales forecasting, geographically segmented reporting, and rate and volume analysis.

Managerial accounting is inherently flexible, and drives towards maximizing internal efficiency through careful consideration of opportunity costs and various customized metrics.

18.2.3: Financial Accounting

Financial accounting is a core organizational function in which accountants prepare a variety of documents to inform stakeholders of the financial health of operations.

Learning Objective

List the various expectations of a financial accounting statement, along with the three common statements produced

Key Points

- The role of financial accounting is of high importance, both for informing external stakeholders and for providing critical information to management.

- Financial accounting statements must be relevant, material, reliable, understandable, and comparable.

- The balance sheet measures all assets, liabilities, and stakeholder equity to identify and understand the organizations leverage position.

- The income statement is a top down statement, in which revenues are considered in the context of the costs and expenses required to obtain them. This ultimately demonstrates profitability.

- The statement of cash flows is all about liquidity, and identifying how much free cash is available to the organization for investment purposes.

- Taking all of these documents into account, stakeholders can derive a clear view of the health and efficiency of operation of a given organization.

Key Terms

- chronological

-

In order of time, usually earliest to latest.

- materiality

-

The state of being consequential in the making of a decision.

The Role of Financial Accounting

Financial accounting focuses on the tracking and preparation of financial statements for internal management and external stakeholders, such as suppliers, investors, government agencies, owners, and other interest groups. These financial statements are consistent with accounting guidelines and formatting, particularly for publicly traded organizations. This allows individuals unfamiliar with day to day operations to see the overall performance, health, and relative profitability of a given organization.

Characteristics of Financial Accounting

Generally speaking, it is expected by financial accounting standards that an organization maintain the following qualities when submitting financial accounting information:

- Relevance – Financial statements must be applicable to the decisions being made, and presented in a way that allows for distilling useful insights.

- Materiality – The information present must be of the quality that indicates consequence in strategic or legal decisions. This is to say that nothing of materiality should be omitted as well.

- Reliability – All information must be free of error, and reported with pinpoint accuracy.

- Understandability – Clarity and efficiency in presentation is important, as it must be immediately readable and without the possibility of being misinterpreted.

- Comparability – Finally, all presented financial statements should align with current best practices in accounting to ensure that the material presented is validly compared to that of other organizations.

How to Conduct Financial Accounting

Financial accountants are tasked with producing three primary documents that indicate a health check on various aspects (or at times all aspects) of the organization. These three statements are the balance sheet, the income statement, and the statement of cash flows.

Balance Sheet

A balance sheet demonstrates the overall value of organizational assets by listing current and long-term assets (fixed or otherwise) alongside short term and long term liabilities and stakeholder equity. Through balancing the assets against the combination of liabilities and stakeholder equity, the financial accounting should encounter a zero sum game.

Simply put: Assets = Liabilities + Shareholder Equity. This is the golden rule of balance sheets (hence the name: balance). The items on a balance sheet can range from long term debt to current inventory to dividends to accounts receivable to cash on hand. Anything and everything that can be valued should be included in this calculation.

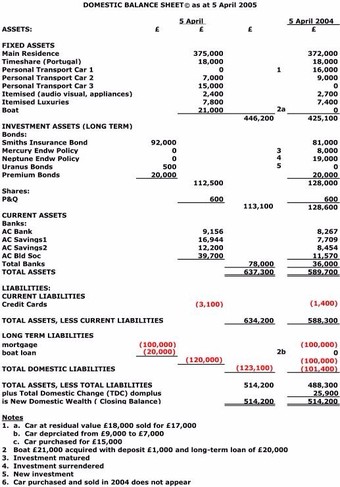

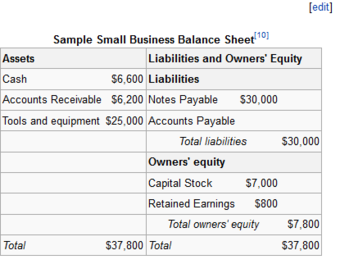

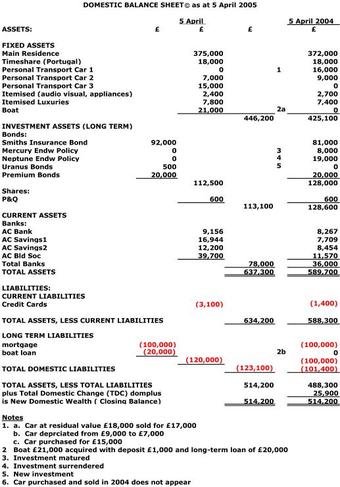

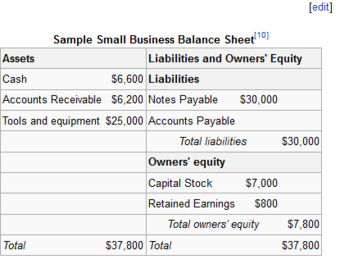

Balance Sheet Example

This balance sheet demonstrates such common line items an account will be populated and measuring when creating and releasing this financial statement.

Income Statement

As opposed to something that balances, the income statement is more of a one directional document. Picture this as a mathematical illustration of the organizations operations, from the production floor all the way to the hands of the consumer. When organizations go through such a process (producing, shipping, storing, paying taxes, selling, providing service, etc.), the expectation is that the price point established will cover all relevant costs while producing some percentage of net income. An income statement calculates whether or not a business is accomplishing this.

To picture it, let’s create a simple example. You own a pizza shop. You sold 1000 pizzas last month. Each pizza sold for $10 on average. That gives you $10,000, but this is your revenue, not your profit. For each pizza, it costs $4 in cheese, dough, sauce and toppings. That brings you down to $6,000. You have to pay your bills and your rent, which is takes you down another $2,000. Now, you’re at $4,000, and you end up paying $1,500 to your employees in wages. Of your $2,500 remaining, 40% goes to state and federal taxes. Your overall net income for the month is $1,500. This process is what an income statement does.

Statement of Cash Flows

The final statement is the statement of cash flows, which aims to identify how much capital in the organization is liquid (i.e. easily converted into spend). This is more of a chronological statement, as it takes the previous pay period and the current pay period, and identifies the difference in overall available cash.

The purpose of this document is quite interesting. An organizations available cash could be considered their flexibility in capturing external opportunities (e.g., investing in new opportunities, such as offering a new product or acquiring a competitor).

Combine these three documents, and stakeholders have a fairly clean view of what goes on in the organization. The balance of their assets, the overall profitability of their operations, and the availability of capital for expansion. This is the role of financial accountants.

18.2.4: Tax Accounting

Tax accounting couples legal obligations with financial accounting to ensure adherence to current tax laws.

Learning Objective

Understand the role of tax accounting in both small and large organizations

Key Points

- Every region has specific tax accounting rules and regulations. Adhering to these rules and regulations is critical to avoiding penalties and ensuring ethical behavior in the country (and/or state) of operation.

- Tax accountants act as a bridge between the organization and the governments that collect financial obligations. As a result, it requires a combination of financial and legal knowledge.

- On the financial side, tax accounts must understand the legal implications of decisions, as both opportunities and threats exist.

- On the legal side, the preparation, assessment, and delivery of tax documents is a time-sensitive and detail-oriented process that must be regularly maintained.

- Some unique situations exist in tax accounting, such as accounting for non-profit organizations (who don’t pay taxes). This still requires considerable legal know how and operational alignment with governmental regulations.

Key Term

- Tax accounting

-

The activity that focuses on satisfying legal accounting obligations through the preparation, analysis, and presentation of required tax documentation.

Tax accounting is relatively simple to explain, though nuanced in execution. In short, every region has specific tax accounting rules and regulations. Adhering to these rules and regulations is critical to avoiding penalties and ensuring ethical behavior in the country (and/or state) of operation. Tax accounting is therefore a combination of legal and financial knowledge.

The Financial Side

Tax accountants act as the bridge between an organization’s accounting team and the reporting bodies in the region. As a result, the primary role of a tax accountant is to understand the business’ current operating status, distill profitability before tax, and report earnings.

On the strategic side of this, tax accountants can consider any tax implications as it pertains to certain strategic decisions or tactics. Identifying and understanding opportunities in a region’s tax code is a win win. For example, some manufacturers can receive tax breaks for environmentally friendly operations, often high enough tax breaks to offset the cost of implementing them. Tax accountants should be aware of these opportunities in the legal environment.

The Legal Side

More tangibly, tax accounts will focus on the preparation, analysis, and presentation of tax payments and tax returns at all times. There are specialized accounting principles and obligations for each area of operation which must be met. Keeping up to date on what is expected, and ensuring alignment on across the organization, is their primary responsibility.

Some exceptions exist, of course, such as non-profit organizations. Non-profits have unique tax preparation requirements due to their no-tax status. This comes along with its fair share of obligations, paperwork, and approvals from the governing bodies.

Various Accounting Perspectives

This image demonstrates the various responsibilities and perspectives of different forms of accounting (those being tax accounting, managerial accounting and financial accounting).

18.2.5: Government and Nonprofit Accounting

Governmental and nonprofit accounting follow different rules from those of commercial enterprises.

Learning Objective

Compare public vs. private accounting

Key Points

- Public sector entities have different goals to the private sector, who’s main goal is to make a profit. Public entities must be more fiscally responsible. The usage of government accounting processes also differs significantly from the use in the private sector.

- Publicly elected officials and their employees must be accountable to the public, and thus government accounting provides information on whether taxpayer funds are used responsibly or not.

- Government accounting must also serve the same purpose as commercial accounting, that is to provide information for decision-making purposes. The difference in this case is the recipient of the information is a government official, with different priorities and goals.

- Nonprofits also have unique accounting systems and standards. They generally use accrual basis accounting for their funds.

- Nonprofit financial statements generally include a balance sheet, a statement of activities or statement of support, a statement of functional expenses, and a cash flow statement.

Key Terms

- budget

-

An itemized summary of intended expenditure; usually coupled with expected revenue.

- Governmental accounting

-

Governmental accounting is an umbrella term which refers to the various accounting systems used by various public sector entities.

Public Sector Accounting

Governmental accounting is an umbrella term which refers to the various accounting systems used by various public sector entities. In the United States, for instance, there are two levels of government which follow different accounting standards set forth by independent, private sector boards. At the federal level, the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB) sets forth the accounting standards to follow. Similarly, there is the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) for state and local level government .

Accounting

Governmental and Nonprofit accounting follow different rules to those of commercial enterprises.

Public vs. Private Accounting

There is an important difference between private sector accounting and governmental accounting. The main reasons for this difference is the environment of the accounting system. In the government environment, public sector entities have differing goals, as opposed to the private sector entities’ one main goal of gaining profit. Also, in government accounting, the entity has the responsibility of fiscal accountability which is demonstration of compliance in the use of resources in a budgetary context. In the private sector, the budget is a tool in financial planning and it is not mandatory to comply with it.

Government accounting refers to the field of accounting that specifically finds application in the public sector or government. The unique objectives of government accounting do not preclude the use of the double entry accounting system. There can, however, be other significant differences with private sector accounting practices, especially those that are intended to arrive at a net income result. Thus, a special field of accounting exists because:

- The objectives to which accounting reports to differ significantly from that for which generally accepted accounting practice has been developed for in the private (business) sector; and

- The usage of the results of accounting processes of government differs significantly from the use thereof in the private sector.

The objectives for which government entities apply accountancy can be organized in two main categories:

- The accounting of activities for accountability purposes. In other words, the representatives of the public, and officials appointed by them, must be accountable to the public for powers and tasks delegated. The public, who have no other choice but to delegate, are in a position that differs significantly from that of shareholders and therefore need financial information, to be supplied by accounting systems, that is applicable and relevant to them and their purposes.

- Decision-making purposes. The relevant role-players, especially officials and representatives, need financial information that is accounted, organized and presented for the objectives of their decision-making. These objectives bear, in many instances, no relation to net income results but are rather about service delivery and efficiency. The taxpayer, a very significant group, simply wants to pay as little taxes as possible for the essential services for which money is being coerced by law.

The governmental accounting system has a different focus for measuring accounting than private sector accounting. Rather than measuring the flow of economic resources, governmental accounting measures the flow of financial resources. Instead of recognizing revenue when they are earned and expenses when they are incurred, revenue is recognized when there is money available to liquidate liabilities within the current accounting period, and expenses are recognized when there is a drain on current resources.

Nonprofit Organizations

Nonprofit organizations generally use the following five categories of funds:

- Current fund – unrestricted. This fund is used to account for current assets that can be used at the discretion of the organization’s governing board.

- Current funds – restricted use current assets subject to restrictions assigned by donors or grantors.

- Land, building and equipment fund. Cash and investments reserved specifically to acquire these assets, and related liabilities, should also be recorded in this fund.

- Endowment funds are used to account for the principal amount of gifts the organization is required, by agreement with the donor, to maintain intact in perpetuity or until a specific future date or event.

- Custodian funds are held and disbursed according to the donor’s instructions.

18.2.6: Consumers of Accounting Information

Most of a company’s stakeholders consume its accounting information in one form or another.

Learning Objective

Explain the history of accounting

Key Points

- Double-entry bookkeeping first emerged in Northern Italy in the fourteenth century.

- As companies grew bigger, accounting standards were required for those without firsthand knowledge of operations to be able to understand the finances and operations of the company.

- Managers, employees, owners, and auditors all desire the information provided by management accounting.

- On the other hand, external auditors, potential and actual shareholders, creditors, analysts, economists, and government agencies rely on financial accounting statements to provide them with the information they need.

Key Terms

- IFRS

-

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) are designed as a common global language for business affairs so that company accounts are understandable and comparable across international boundaries.

- GAAP

-

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) refer to the standard framework of guidelines for financial accounting used in any given jurisdiction; generally known as accounting standards.

Early accounts served mainly to assist the memory of the businessperson, and the audience for the account was the proprietor or record keeper alone. Cruder forms of accounting were inadequate for the problems created by a business entity involving multiple investors, so double-entry bookkeeping first emerged in northern Italy in the fourteenth century, where trading ventures began to require more capital than a single individual was able to invest.

The development of joint stock companies created wider audiences for accounts, as investors without firsthand knowledge of their operations relied on accounts to provide the requisite information. This development resulted in a split of accounting systems for internal (i.e., management accounting) and external (i.e., financial accounting) purposes and, subsequently, also in accounting and disclosure regulations and a growing need for independent attestation of external accounts by auditors.

Today, accounting is called “the language of business” because it is the vehicle for reporting financial information about a business entity to many different groups of people. Accounting that concentrates on reporting to people inside the business entity is called “management accounting” and is used to provide information to employees, managers, owner-managers, and auditors.

Management accounting is concerned primarily with providing a basis for making management or operating decisions. Accounting that provides information to people outside the business entity is called “financial accounting” and provides information to present and potential shareholders and creditors, such as banks or vendors, financial analysts, economists, and government agencies. Because these users have different needs, the presentation of financial accounts is very structured and subject to many more rules than management accounting. The body of rules that governs financial accounting in a given jurisdiction is the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, or GAAP. Other rules include International Financial Reporting Standards, or IFRS, or U.S. GAAP.

A Sample Income Statement

Expenses are listed on a company’s income statement.

18.3: The Accounting Process

18.3.1: The Accounting Equation

The accounting equation is a general rule used in business transactions where the sum of liabilities and owners’ equity equals assets.

Learning Objective

Break down the fundamental accounting equation

Key Points

- This equation is kept in balance after every business transaction. Everything falls under these three elements (assets, liability, owners’ equity) in a business transaction.

- Assets = Liabilities + Equity.

- The fundamental accounting equation is the foundation of the balance sheet.

Key Terms

- Accounting Equation

-

The “basic accounting equation” is the foundation for the double-entry bookkeeping system. For each transaction, the total debits equal the total credits.

- equity

-

Ownership interest in a company as determined by subtracting liabilities from assets.

- liabilities

-

An amount of money in a company that is owed to someone and has to be paid in the future, such as tax, debt, interest, and mortgage payments.

Example

- A company with $30,000 in liabilities and $10,000 in owners’ equity would have $40,000 in assets according to the accounting equation.

The fundamental accounting equation, which is also known as the balance sheet equation, looks like this:

. On the left side of the equation are the assets of the business, including cash, accounts receivable, notes receivable, property, plants, and equipment. Or more correctly, the term “assets” represents the value of the resources of the business.

On the right side of the equation are claims of ownership on those assets: liabilities are the claims of creditors (those “outside” the business); and equity, or owners’ equity, is the claim of the owners of the business (those “inside” the business). The fundamental accounting equation is kept in balance after every business transaction because everything falls under these three elements in a business transaction.

For example, when a company intends to purchase new equipment, its owner or board of directors has to choose how to raise funds for the purchase. Looking at the fundamental accounting equation, one can see how the equation stays is balance. If the funds are borrowed to purchase the asset, assets and liabilities both increase. If the company issues stock to obtain the funds for the purchase, then assets and equity both increase.

Additionally, changes is the accounting equation may occur on the same side of the equation. For example, if the company uses cash to purchase inventory, cash is decreased (credited) and inventory is increased (debited); thus, assets as a whole remain unchanged and the equation remains in balance. Likewise, as the company receives payment from its customers, accounts receivable is credited and cash is debited.

Sample Balance Sheet

A balance sheet shows how the accounting equation is applied.

18.3.2: Double-Entry Bookkeeping

A double-entry bookkeeping system requires that every transaction be recorded in at least two different nominal ledger accounts.

Learning Objective

Explain the fundamentals of accounting bookkeeping

Key Points

- In the double-entry accounting system, each accounting entry records related pairs of financial transactions for asset, liability, income, expense, or capital accounts.

- There are two different approaches to the double entry system of bookkeeping. They are Traditional Approach and Accounting Equation Approach.

- Recording of a debit amount to one account and an equal credit amount to another account results in total debits being equal to total credits for all accounts in the general ledger.

Key Terms

- debit

-

Debit and credit are the two fundamental aspects of every financial transaction in the double-entry bookkeeping system in which every debit transaction must have a corresponding credit transaction(s) and vice versa.

- debit card

-

a product that can be used to make payments by drawing money directly from the user’s bank account

Double-Entry Bookkeeping

A double-entry bookkeeping system is a set of rules for recording financial information in a financial accounting system in which every transaction or event changes at least two different nominal ledger accounts.

In the double-entry accounting system, each accounting entry records related pairs of financial transactions for asset, liability, income, expense, or capital accounts. Recording of a debit amount to one account and an equal credit amount to another account results in total debits being equal to total credits for all accounts in the general ledger. If the accounting entries are recorded without error, the aggregate balance of all accounts having positive balances will be equal to the aggregate balance of all accounts having negative balances. Accounting entries that debit and credit related accounts typically include the same date and identifying code in both accounts, so that in case of error, each debit and credit can be traced back to a journal and transaction source document, thus preserving an audit trail.

The “Golden Rules of Accounting”

The rules for formulating accounting entries are known as “Golden Rules of Accounting”. The accounting entries are recorded in the “Books of Accounts”. Regardless of which accounts and how many are impacted by a given transaction, the fundamental accounting equation A = L + OE (assets equals liabilities plus owner’s equity) will hold.

There are two different approaches to the double entry system of bookkeeping. They are the Traditional Approach and the Accounting Equation Approach. Irrespective of the approach used, the effect on the books of accounts remain the same, with two aspects (debit and credit) in each of the transactions.

Traditional Approach (British)

Following this approach, accounts are classified as real, personal, or nominal accounts. Real accounts are assets. Personal accounts are liabilities and owners’ equity and represent people and entities that have invested in the business. Nominal accounts are revenue, expenses, gains, and losses.

Transactions are entered in the books of accounts by applying the following golden rules of accounting:

- Personal account: Debit the receiver and credit the giver

- Real account: Debit what comes in and credit what goes out

- Nominal account: Debit all expenses & losses and credit all incomes & gains

Accounting Equation Approach (American)

Under this approach, transactions are recorded based on the accounting equation, i.e., Assets = Liabilities + Capital. The accounting equation is a statement of equality between the debits and the credits. The rules of debit and credit depend on the nature of an account. For the purpose of the accounting equation approach, all the accounts are classified into one of the following five types:

- Assets

- Liabilities

- Income/revenues

- Expenses

- Capital gains/losses

If there is an increase or decrease in one account, there will be an equal decrease or increase in another account. There may be equal increases to both accounts, depending on what kind of accounts they are. There may also be equal decreases to both accounts. Accordingly, the following rules of debit and credit in respect to the various categories of accounts can be obtained.

The rules may be summarized as below:

- Assets accounts: Debit increases in assets and credit decreases in assets

- Capital account: Credit increases in capital and debit decreases in capital

- Liabilities accounts: Credit increases in liabilities and debit decreases in liabilities

- Revenues or Incomes accounts: Credit increases in incomes and gains and debit decreases in incomes and gains

- Expenses or Losses accounts: Debit increases in expenses and losses and credit decreases in expenses and losses

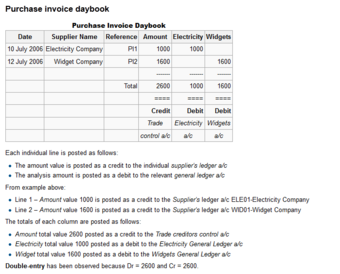

Example of Double entry bookkeping

Purchase Invoice Daybook

18.3.3: The Accounting Cycle

The accounting cycle includes analysis of transactions, transferring journal entries into a general ledger, revenue, and expense closed.

Learning Objective

Outline the accounting cycle from point of transaction to financial statements

Key Points

- When a transaction occurs, a document is produced. Most of the time these documents are external to the business, however, they can also be internal documents, such as inter-office sales. These documents are referred to as a source document.

- The Journal entries are then transferred to a Ledger. The group of accounts is called ledger, or a book of accounts. The purpose of a Ledger is to bring together all of the transactions for similar activity.

- Financial statements are drawn from the trial balance which may include: the Income statement, the Balance sheet, and the Cash flow statement.

- 3. prepare trial balance

- 4. post adjusting entries

- 5. prepare adjusted trial balance

- 6. prepare financial statements

- 7. post closing entries

- 8. prepare a post closing trial balance

Key Term

- Journal entries

-

A journal entry, in accounting, is a logging of transactions into accounting journal items. The journal entry can consist of several items, each of which is either a debit or a credit.

When a transaction occurs, a document is produced. Most of the time these documents are external to the business, however, they can also be internal documents, such as inter-office sales.

These documents are referred to as a source document. Some examples are: the receipt you get when you purchase something at the store, interest you earned on your savings account which is documented in your monthly bank statement, and the monthly electric utility bill that comes in the mail. These source documents are then recorded in a Journal. This is also known as a book of first entry. It records both sides of the transaction recorded by the source document. These write-ups are known as Journal entries.

These Journal entries are then transferred to a Ledger, which is the group of accounts, also known as a book of accounts. The purpose of a Ledger is to bring together all of the transactions for similar activity. For example, if a company has one bank account, then all transactions that include cash would then be maintained in the Cash Ledger. This process of transferring the values is known as posting. Once the entries have all been posted, the Ledger accounts are added up in a process called Balancing.

A particular working document called an unadjusted Trial balance is created. This lists all the balances from all the accounts in the Ledger. Notice that the values are not posted to the trial balance, they are merely copied. At this point accounting happens. The accountant produces a number of adjustments which make sure that the values comply with accounting principles. These values are then passed through the accounting system resulting in an adjusted Trial balance. This process continues until the accountant is satisfied.

Financial statements are drawn from the trial balance which may include: the Income statement, the Balance sheet, and the Cash flow statement.

Finally, all the revenue and expense accounts are closed.

18.4: The Balance Sheet

18.4.1: Defining the Balance Sheet

The balance sheet is a summary of the financial balances of a company.

Learning Objective

Explain the fundamental elements of the balance sheet

Key Points

- The balance sheet is often described as a snapshot of a company’s financial condition.

- Unlike the other basic financial statements, the balance sheet only applies to a single point in time of the calendar year.

- It shows the assets, liabilities, and ownership equity of the company, and allows for an analysis of the company’s financial health.

Key Terms

- balance sheet

-

A summary of a person’s or organization’s assets, liabilities and equity as of a specific date.

- calendar year

-

The amount of time between corresponding dates in adjacent years in any calendar.

The Balance Sheet

In financial accounting, a balance sheet is a snapshot of a company’s (sole proprietorship, a business partnership, a corporation, or other business organization, such as an LLC or an LLP) financial situation. Assets, liabilities, and ownership equity are listed as of a specific date, such as the end of the company’s financial year. Of the four basic financial statements, the balance sheet is the only statement which applies to a single point in time of a business’ calendar year. A standard company balance sheet has three parts: assets, liabilities, and ownership equity. The main categories of assets are usually listed first, and typically in order of liquidity. Assets are followed by the liabilities. The difference between the assets and the liabilities is known as the equity (or the net assets, or the net worth, or capital) of the company, and according to the accounting equation, net worth must equal assets minus liabilities.

Another way to look at the same equation is that assets equals liabilities plus owner’s equity. Looking at the equation in this way shows how assets were financed: either by borrowing money (liability) or by using the owner’s money (owner’s equity). Balance sheets are usually presented with assets in one section and liabilities and net worth in the other section with the two sections “balancing. “

A business operating entirely in cash can measure its profits by withdrawing the entire bank balance at the end of the period, plus any cash in hand. However, many businesses are not paid immediately; they build up inventories of goods and they acquire buildings and equipment. In other words: businesses have assets and so they cannot, even if they want to, immediately turn these into cash at the end of each period. Often, these businesses owe money to suppliers and to tax authorities, and the proprietors do not withdraw all their original capital and profits at the end of each period. In other words, businesses also have liabilities.

Example Domestic Balance Sheet

This balance sheet shows the company’s assets, liabilities, and shareholder equity.

18.4.2: Assets

Assets are resources as a result of past events and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the enterprise.

Learning Objective

Define assets in financial accounting

Key Points

- Anything tangible or intangible that can be owned to produce positive economic value is considered an asset. Examples are cash, inventory, machinery, etc.

- Assets are recorded on the balance sheet. The accounting equation relating assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity is: Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ Equity.

- Tangible assets are actual physical assets, and include both current and fixed assets. Examples are inventory, buildings, and equipment.

- Intangible assets are nonphysical resources which give the firm an advantage in the marketplace. Examples are copyrights, computer programs, financial assets, and goodwill.

Key Terms

- International Accounting Standards Board

-

The independent, accounting standard-setting body of the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation.

- tangible asset

-

Any asset, such as buildings, land, equipment etc., that has physical form.

- intangible asset

-