19.1: The Enlightenment

19.1.1: Introduction to the Enlightenment

The Enlightenment, a philosophical movement that dominated in Europe during the 18th century, was centered around the idea that reason is the primary source of authority and legitimacy, and advocated such ideals as liberty, progress, tolerance, fraternity, constitutional government, and separation of church and state.

Learning Objective

Explain the main ideas of the Age of Enlightenment

Key Points

-

The Enlightenment was a philosophical movement that dominated in Europe during the 18th century. It was centered around the idea that reason

is the primary source of authority and legitimacy, and it advocated such ideals

as liberty, progress, tolerance, fraternity, constitutional government, and

separation of church and state. However, historians of race, gender, and class note that Enlightenment ideals

were not originally envisioned as universal in today’s sense of the word. -

The Philosophic Movement advocated for a society based upon reason rather than

faith and Catholic doctrine, for a new civil order based on natural law, and

for science based on experiments and observation. -

There

were two distinct lines of Enlightenment thought: the radical enlightenment,

advocating democracy, individual

liberty, freedom of expression, and eradication of religious authority. A

second, more moderate variety sought accommodation between reform

and the traditional systems of power and faith. -

While the Enlightenment cannot be pigeonholed

into a specific doctrine or set of dogmas, science came to play a leading role

in Enlightenment discourse and thought. -

The

Enlightenment brought political modernization to the west, in terms of focusing on democratic values and institutions and the

creation of modern, liberal democracies. -

Enlightenment

thinkers sought to curtail the political power of organized religion, and

thereby prevent another age of intolerant religious war. The

radical Enlightenment promoted the concept of separating church and state.

Key Terms

- reductionism

-

The term that refers to several related but distinct philosophical positions regarding the connections between phenomena, or theories, “reducing” one to another, usually considered “simpler” or more “basic.” The Oxford Companion to Philosophy suggests a three part division: ontological (a belief that the whole of reality consists of a minimal number of parts); methodological (the scientific attempt to provide explanation in terms of ever smaller entities); and theory (the suggestion that a newer theory does not replace or absorb the old, but reduces it to more basic terms).

- Newtonianism

-

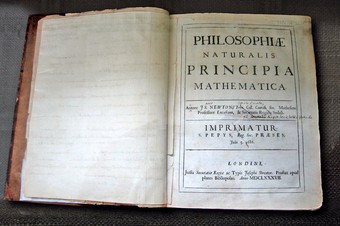

A doctrine that involves following the principles and using the methods of natural philosopher Isaac Newton. Newton’s broad conception of the universe as being governed by rational and understandable laws laid the foundation for many strands of Enlightenment thought.

- Encyclopédie

-

A general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised editions, and translations. It had many writers and was edited by Denis Diderot, and, until 1759, co-edited by Jean le Rond d’Alembert.

It is the most famous for representing the thought of the Enlightenment. - empiricism

-

A theory that states that knowledge comes only or primarily from sensory experience. One of several views of epistemology, the study of human knowledge, along with rationalism and skepticism, it emphasizes the role of experience and evidence (especially sensory experience), in the formation of ideas, over the notion of innate ideas or traditions.

- scientific method

-

A body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge based on empirical or measurable evidence subject to specific principles of reasoning. The Oxford Dictionaries Online define it as “a method or procedure that has characterized natural science since the 17th century, consisting in systematic observation, measurement, and experiment, and the formulation, testing, and modification of hypotheses.”

Introduction

The Enlightenment, also known as the Age of Enlightenment, was a philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe in the 18th century. It was centered around the idea that reason is the primary source of authority and legitimacy, and it advocated such ideals as liberty, progress, tolerance, fraternity, constitutional government, and separation of church and state. The Enlightenment was marked by an emphasis on the scientific method and reductionism, along with increased questioning of religious orthodoxy.

The ideas of the Enlightenment undermined the authority of the monarchy and the church, and paved the way for the political revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries.

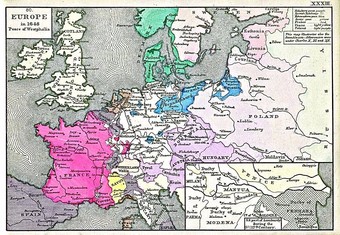

French historians traditionally place the Enlightenment between 1715, the year that Louis XIV died, and 1789, the beginning of the French Revolution. Some recent historians begin the period in the 1620s, with the start of the scientific revolution. However, different national varieties of the movement flourished between the first decades of the 18th century and the first decades of the 19th century.

The ideas of the Enlightenment played a major role in inspiring the French Revolution, which began in 1789 and emphasized the rights of the common men, as opposed to the exclusive rights of the elites. However, historians of race, gender, and class note that Enlightenment ideals were not originally envisioned as universal in the today’s sense of the word. Although they did eventually inspire the struggle for rights of people of color, women, or the working masses, most Enlightenment thinkers did not advocate equality for all, regardless of race, gender, or class, but rather insisted that rights and freedoms were not hereditary. This perspective directly attacked the traditionally exclusive position of the European aristocracy, but was still largely limited to expanding the political and individual rights of white males of particular social standing.

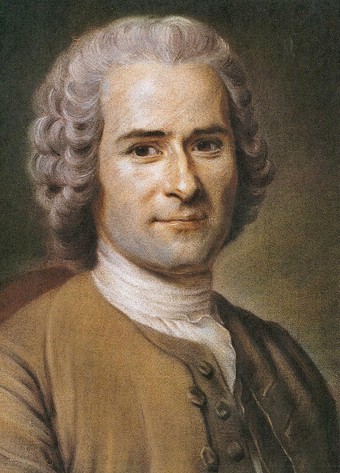

Philosophy

In the mid-18th century, Europe witnessed an explosion of philosophic and scientific activity that challenged traditional doctrines and dogmas. The philosophic movement was led by Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who argued for a society based upon reason rather than faith and Catholic doctrine, for a new civil order based on natural law, and for science based on experiments and observation. The political philosopher Montesquieu introduced the idea of a separation of powers in a government, a concept which was enthusiastically adopted by the authors of the United States Constitution. While the philosophers of the French Enlightenment were not revolutionaries, and many were members of the nobility, their ideas played an important part in undermining the legitimacy of the Old Regime and shaping the French Revolution.

There were two distinct lines of Enlightenment thought: the radical enlightenment, inspired by the philosophy of Spinoza, advocating democracy, individual liberty, freedom of expression, and eradication of religious authority. A second, more moderate variety, supported by René Descartes, John Locke, Christian Wolff, Isaac Newton and others, sought accommodation between reform and the traditional systems of power and faith.

Much of what is incorporated in the scientific method (the nature of knowledge, evidence, experience, and causation), and some modern attitudes towards the relationship between science and religion, were developed by David Hume and Adam Smith. Hume became a major figure in the skeptical philosophical and empiricist traditions of philosophy. Immanuel Kant tried to reconcile rationalism and religious belief, individual freedom and political authority, as well as map out a view of the public sphere through private and public reason. Kant’s work continued to shape German thought, and indeed all of European philosophy, well into the 20th century. Mary Wollstonecraft was one of England’s earliest feminist philosophers. She argued for a society based on reason, and that women, as well as men, should be treated as rational beings.

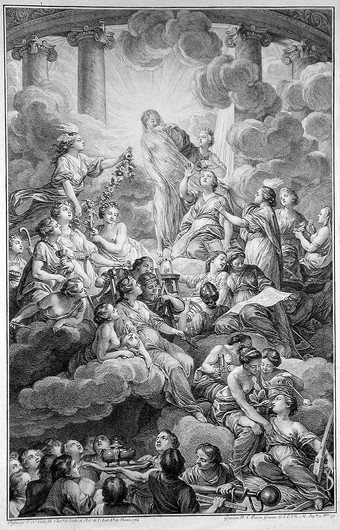

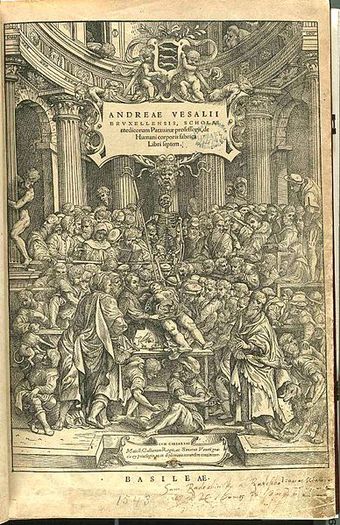

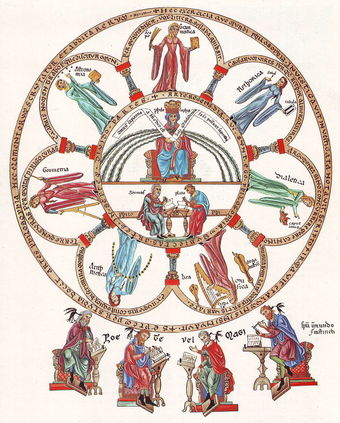

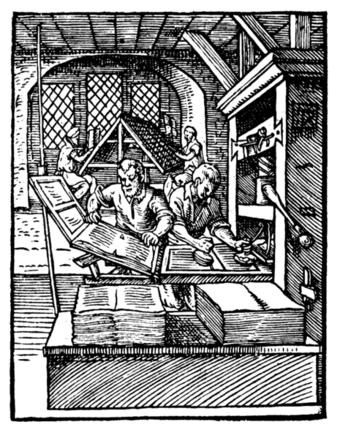

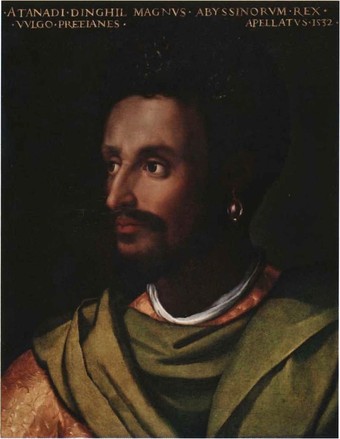

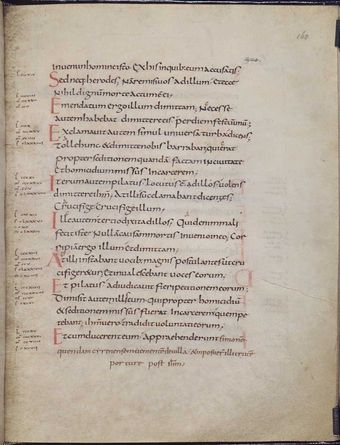

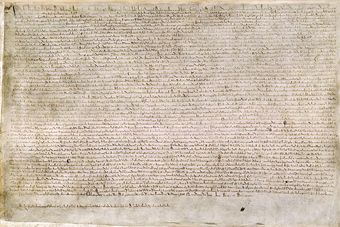

Encyclopedie’s frontispiece, full version; engraving by Benoît Louis Prévost.

“If there is something you know, communicate it. If there is something you don’t know, search for it.” An engraving from the 1772 edition of the Encyclopédie. Truth, in the top center, is surrounded by light and unveiled by the figures to the right, Philosophy and Reason.

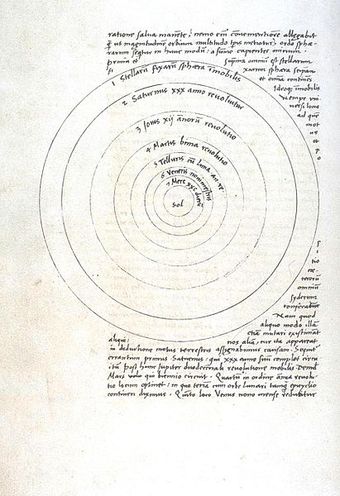

Science

While the Enlightenment cannot be pigeonholed into a specific doctrine or set of dogmas, science came to play a leading role in Enlightenment discourse and thought. Many Enlightenment writers and thinkers had backgrounds in the sciences, and associated scientific advancement with the overthrow of religion and traditional authority in favor of the development of free speech and thought. Broadly speaking, Enlightenment science greatly valued empiricism and rational thought, and was embedded with the Enlightenment ideal of advancement and progress. As with most Enlightenment views, the benefits of science were not seen universally.

Science during the Enlightenment was dominated by scientific societies and academies, which had largely replaced universities as centers of scientific research and development. Societies and academies were also the backbone of the maturation of the scientific profession. Another important development was the popularization of science among an increasingly literate population. Many scientific theories reached the wide public, notably through the Encyclopédie (a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772) and the popularization of Newtonianism.

The 18th century saw significant advancements in the practice of medicine, mathematics, and physics; the development of biological taxonomy; a new understanding of magnetism and electricity; and the maturation of chemistry as a discipline, which established the foundations of modern chemistry.

Modern Western Government

The Enlightenment has long been hailed as the foundation of modern western political and intellectual culture. It brought political modernization to the west, in terms of focusing on democratic values and institutions, and the creation of modern, liberal democracies.

The English philosopher Thomas Hobbes ushered in a new debate on government with his work Leviathan in 1651. Hobbes also developed some of the fundamentals of European liberal thought: the right of the individual; the natural equality of all men; the artificial character of the political order (which led to the later distinction between civil society and the state); the view that all legitimate political power must be “representative” and based on the consent of the people; and a liberal interpretation of law which leaves people free to do whatever the law does not explicitly forbid.

John Locke and Rousseau also developed social contract theories. While differing in details, Locke, Hobbes, and Rousseau agreed that a social contract, in which the government’s authority lies in the consent of the governed, is necessary for man to live in civil society. Locke is particularly known for his statement that individuals have a right to “Life, Liberty and Property,” and his belief that the natural right to property is derived from labor. His theory of natural rights has influenced many political documents, including the United States Declaration of Independence and the French National Constituent Assembly’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Though much of Enlightenment’s political thought was dominated by social contract theorists, some Scottish philosophers, most notably David Hume and Adam Ferguson, criticized this camp. Theirs was the assumption that governments derived from a ruler’s authority and force (Hume) and polities grew out of social development rather than social contract (Ferguson).

Religion

Enlightenment era religious commentary was a response to the preceding century of religious conflict in Europe. Enlightenment thinkers sought to curtail the political power of organized religion, and thereby prevent another age of intolerant religious war. A number of novel ideas developed, including Deism (belief in God the Creator, with no reference to the Bible or any other source)

and atheism. The latter was much discussed but there were few proponents. Many, like Voltaire, held that without belief in a God who punishes evil, the moral order of society was undermined.

The radical Enlightenment promoted the concept of separating church and state, an idea often credited to Locke. According to Locke’s principle of the social contract, the government lacked authority in the realm of individual conscience, as this was something rational people could not cede to the government for it or others to control. For Locke, this created a natural right in the liberty of conscience, which he said must therefore remain protected from any government authority. These views on religious tolerance and the importance of individual conscience, along with the social contract, became particularly influential in the American colonies and the drafting of the United States Constitution.

Mary Wollstonecraft by John Opie (c. 1797), National Portrait Gallery, London.

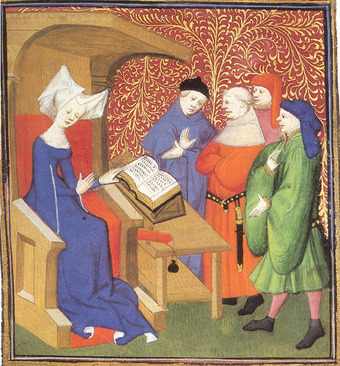

While the philosophy of the Enlightenment was dominated by men, the question of women’s rights appeared as one of the most controversial ideas. Mary Wollstonecraft, one of few female thinkers of the time, was an English writer, philosopher, and advocate of women’s rights. She is best known for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), in which she argues that women are not naturally inferior to men, but appear to be only because they lack education. She suggests that both men and women should be treated as rational beings and imagines a social order founded on reason.

19.1.2: Rationalism

Rationalism, or a belief that we come to knowledge through the use of logic, and thus independently of sensory experience, was critical to the debates of the Enlightenment period, when most philosophers lauded the power of reason but insisted that knowledge comes from experience.

Learning Objective

Define rationalism and its role in the ideas of the Enlightenment

Key Points

-

Rationalism—as an appeal to human reason as a

way of obtaining knowledge—has a philosophical history dating from antiquity.

While rationalism did not dominate the Enlightenment, it laid critical

basis for the debates that developed over the course of the 18th century. -

René

Descartes (1596-1650), the first of the modern rationalists, laid the groundwork for debates developed during the Enlightenment. He thought that

the knowledge of eternal truths could be attained by reason alone (no experience was necessary). -

Since the Enlightenment, rationalism is usually

associated with the introduction of mathematical methods into philosophy as

seen in the works of Descartes, Leibniz, and Spinoza. This is commonly called

continental rationalism, because it was predominant in the continental schools

of Europe, whereas in Britain empiricism dominated. -

Both Spinoza and Leibniz asserted that, in

principle, all knowledge, including scientific knowledge, could be gained

through the use of reason alone, though they both observed that this was not

possible in practice for human beings, except in specific areas, such as mathematics. - While

empiricism (a theory that knowledge comes

only or primarily from a sensory experience) dominated the Enlightenment, Immanuel Kant, attempted to combine the principles of empiricism and rationalism.

He concluded that both reason and

experience are necessary for human knowledge. -

Since the Enlightenment, rationalism in politics

historically emphasized a “politics of reason” centered upon rational

choice, utilitarianism, and secularism.

Key Terms

- cogito ergo sum

-

A Latin philosophical proposition by René Descartes, the first modern rationalist, usually translated into English as “I think, therefore I am.” This proposition became a fundamental element of western philosophy, as it purported to form a secure foundation for knowledge in the face of radical doubt. Descartes asserted that the very act of doubting one’s own existence served, at minimum, as proof of the reality of one’s own mind.

- empiricism

-

A theory that states

that knowledge comes only, or primarily, from sensory experience. One of

several views of epistemology, the study of human knowledge, along with

rationalism and skepticism, it emphasizes the role of experience and

evidence, especially sensory experience, in the formation of ideas over the

notion of innate ideas or traditions. - metaphysics

-

A traditional branch of philosophy concerned with explaining the fundamental nature of being and the world that encompasses it, although the term is not easily defined. Traditionally, it attempts to answer two basic questions in the broadest possible terms: “Ultimately, what is there?” and “What is it like?”

Introduction

Rationalism—as an appeal to human reason as a way of obtaining knowledge—has a philosophical history dating from antiquity. While rationalism, as the view that reason is the main source of knowledge, did not dominate the Enlightenment, it laid critical basis for the debates that developed over the course of the 18th century.

As the Enlightenment centered on reason as the primary source of authority and legitimacy, many philosophers of the period drew from earlier philosophical contributions, most notably those of René

Descartes (1596-1650), a French philosopher, mathematician, and scientist.

Descartes was the first of the modern rationalists. He thought that only knowledge of eternal truths (including the truths of mathematics and the foundations of the sciences) could be attained by reason alone, while the knowledge of physics required experience of the world, aided by the scientific method. He argued that reason alone determined knowledge, and that this could be done independently of the senses. For instance, his famous dictum, cogito ergo sum, or “I think, therefore I am,” is a conclusion reached a priori (i.e., prior to any kind of experience on the matter). The simple meaning is that doubting one’s existence, in and of itself, proves that an “I” exists to do the thinking.

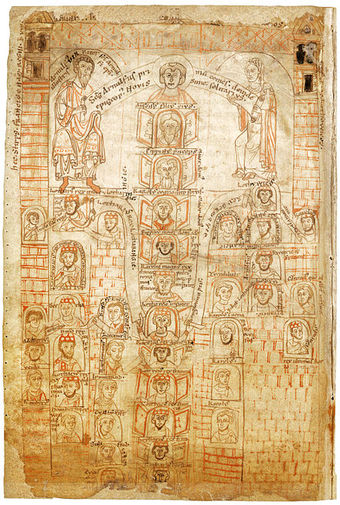

René Descartes, after Frans Hals, 2nd half of the 17th century.

Descartes laid the foundation for 17th-century continental rationalism, later advocated by Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Leibniz, and opposed by the empiricist school of thought consisting of Hobbes, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. Leibniz, Spinoza, and Descartes were all well-versed in mathematics, as well as philosophy, and Descartes and Leibniz contributed greatly to science as well.

Rationalism v. Empiricism

Since the Enlightenment, rationalism is usually associated with the introduction of mathematical methods into philosophy, as seen in the works of Descartes, Leibniz, and Spinoza. This is commonly called continental rationalism, because it was predominant in the continental schools of Europe, whereas in Britain, empiricism, or a theory that knowledge comes only or primarily from a sensory experience, dominated. Although rationalism and empiricism are traditionally seen as opposing each other, the distinction between rationalists and empiricists was drawn at a later period, and would not have been recognized by philosophers involved in Enlightenment debates. Furthermore, the distinction between the two philosophies is not as clear-cut as is sometimes suggested. For example, Descartes and John Locke, one of the most important Enlightenment thinkers, have similar views about the nature of human ideas.

Proponents of some varieties of rationalism argue that, starting with foundational basic principles, like the axioms of geometry, one could deductively derive the rest of all possible knowledge. The philosophers who held this view most clearly were Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Leibniz, whose attempts to grapple with the epistemological and metaphysical problems raised by Descartes led to a development of the fundamental approach of rationalism. Both Spinoza and Leibniz asserted that, in principle, all knowledge, including scientific knowledge, could be gained through the use of reason alone, though they both observed that this was not possible in practice for human beings, except in specific areas, such as mathematics. On the other hand, Leibniz admitted in his book, Monadology, that “we are all mere Empirics in three fourths of our actions.”

Immanuel Kant

Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz are usually credited for laying the groundwork for the 18th-century Enlightenment. During the mature Enlightenment period, Immanuel Kant attempted to explain the relationship between reason and human experience, and to move beyond the failures of traditional philosophy and metaphysics. He wanted to put an end to an era of futile and speculative theories of human experience, and regarded himself as ending and showing the way beyond the impasse between rationalists and empiricists. He is widely held to have synthesized these two early modern traditions in his thought.

Kant named his brand of epistemology (theory of knowledge) “transcendental idealism,” and he first laid out these views in his famous work, The Critique of Pure Reason. In it, he argued that there were fundamental problems with both rationalist and empiricist dogma. To the rationalists he argued, broadly, that pure reason is flawed when it goes beyond its limits and claims to know those things that are necessarily beyond the realm of all possible experience (e.g., the existence of God, free will, or the immortality of the human soul). To the empiricist, he argued that while it is correct that experience is fundamentally necessary for human knowledge, reason is necessary for processing that experience into coherent thought. He therefore concluded that both reason and experience are necessary for human knowledge. In the same way, Kant also argued that it was wrong to regard thought as mere analysis. In his views, a priori concepts do exist, but if they are to lead to the amplification of knowledge, they must be brought into relation with empirical data.

Immanuel Kant, author unknown

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) rejected the dogmas of both rationalism and empiricism, and tried to reconcile rationalism and religious belief, and individual freedom and political authority, as well as map out a view of the public sphere through private and public reason. His work continued to shape German thought, and indeed all of European philosophy, well into the 20th century.

Politics

Since the Enlightenment, rationalism in politics historically emphasized a “politics of reason” centered upon rational choice, utilitarianism, and secularism (later, relationship between rationalism and religion was ameliorated by the adoption of pluralistic rationalist methods practicable regardless of religious or irreligious ideology). Some philosophers today, most notably John Cottingham, note that rationalism, a methodology, became socially conflated with atheism, a worldview. Cottingham writes,

In the past, particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries, the term ‘rationalist’ was often used to refer to free thinkers of an anti-clerical and anti-religious outlook, and for a time the word acquired a distinctly pejorative force (…). The use of the label ‘rationalist’ to characterize a world outlook which has no place for the supernatural is becoming less popular today; terms like ‘humanist’ or ‘materialist’ seem largely to have taken its place. But the old usage still survives.

19.1.3: Natural Rights

Natural rights, understood as those that are not dependent on the laws, customs, or beliefs of any particular culture or government,(and therefore, universal and inalienable) were central to the debates during the Enlightenment on the relationship between the individual and the government.

Learning Objective

Identify natural rights and why they were important to the philosophers of the Enlightenment.

Key Points

-

Natural rights are those that are not dependent

on the laws, customs, or beliefs of any particular culture or government, and

are therefore universal and inalienable (i.e., rights that cannot be repealed

or restrained by human laws). They are usually defined in opposition to legal rights, or

those bestowed onto a person by a given legal

system. -

Although natural rights have been discussed

since antiquity, it was the philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment that

developed the modern concept of natural rights, which has been critical to the

modern republican government and civil society. -

During the Enlightenment, natural rights developed as part of

the social contract theory. The theory addressed the questions of the origin of

society and the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. -

Thomas Hobbes’ conception of natural rights

extended from his conception of man in a “state of nature.” He objected to the

attempt to derive rights from “natural law,” arguing that law

(“lex”) and right (“jus”) though often confused, signify

opposites, with law referring to obligations, while rights refers to the absence

of obligations. -

The most famous natural right formulation comes

from John Locke, who argued that the natural rights include

perfect equality and freedom, and the right to preserve life and property. Other Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment philosophers that developed and complicated the concept of natural rights were John Lilburne, Francis Hutcheson, Georg Hegel, and Thomas

Paine. - The modern European anti-slavery movement drew heavily from the concept of natural rights that became central to the efforts of European abolitionists.

Key Terms

- Natural rights

-

The rights that are not dependent on the laws, customs, or beliefs of any particular culture or government, and are therefore universal and inalienable (i.e., rights that cannot be repealed or restrained by human laws). Some, yet not all, see them as synonymous with human rights.

- natural law

-

A philosophy that certain rights or values are inherent by virtue of human nature, and can be universally understood through human reason. Historically, it refers to the use of reason to analyze both social and personal human nature in order to deduce binding rules of moral behavior. The law of nature, like nature itself, is universal.

- Legal rights

-

The rights bestowed onto a person by a given legal system (i.e., rights that can be modified, repealed, and restrained by human laws).

- social contract theory

-

In moral and political philosophy, a theory or model originating during the Age of Enlightenment that typically addresses the questions of the origin of society and the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. It typically posits that individuals have consented, either explicitly or tacitly, to surrender some of their freedoms and submit to the authority of the ruler or magistrate (or to the decision of a majority), in exchange for protection of their remaining rights.

Natural Rights and Natural Law

Natural rights are usually juxtaposed with the concept of

legal rights. Legal rights are those bestowed onto a person by a given legal system (i.e., rights that can be modified, repealed, and restrained by human laws). Natural rights are those that are not dependent on the laws, customs, or beliefs of any particular culture or government, and are therefore universal and inalienable (i.e., rights that cannot be repealed or restrained by human laws). Natural rights are closely related to the concept of natural law (or laws). During the Enlightenment, the concept of natural laws was used to challenge the divine right of kings, and became an alternative justification for the establishment of a social contract, positive law, and government (and thus, legal rights) in the form of classical republicanism (built around concepts such as civil society, civic virtue, and mixed government). Conversely, the concept of natural rights is used by others to challenge the legitimacy of all such establishments.

The idea of natural rights is also closely related to that of human rights; some acknowledge no difference between the two, while others choose to keep the terms separate to eliminate association with some features traditionally associated with natural rights. Natural rights, in particular, are considered beyond the authority of any government or international body to dismiss.

Natural Rights and Social Contract

Although natural rights have been discussed since antiquity, it was the philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment that developed the modern concept of natural rights, which has been critical to the modern republican government and civil society.

At the time, natural rights developed as part of the social contract theory, which addressed the questions of the origin of society and the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Social contract arguments typically posit that individuals have consented, either explicitly or tacitly, to surrender some of their freedoms and submit to the authority of the ruler or magistrate (or to the decision of a majority), in exchange for protection of their remaining rights. The question of the relation between natural and legal rights, therefore, is often an aspect of social contract theory.

Thomas Hobbes’ conception of natural rights extended from his conception of man in a “state of nature.” He argued that the essential natural (human) right was “to use his own power, as he will himself, for the preservation of his own Nature; that is to say, of his own Life.” Hobbes sharply distinguished this natural “liberty” from natural “laws.” In his natural state, according to Hobbes, man’s life consisted entirely of liberties, and not at all of laws. He objected to the attempt to derive rights from “natural law,” arguing that law (“lex”) and right (“jus”) though often confused, signify opposites, with law referring to obligations, while rights refer to the absence of obligations. Since by our (human) nature, we seek to maximize our well being, rights are prior to law, natural or institutional, and people will not follow the laws of nature without first being subjected to a sovereign power, without which all ideas of right and wrong are meaningless.

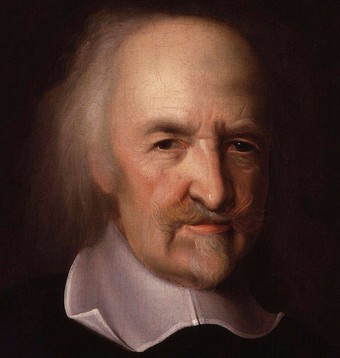

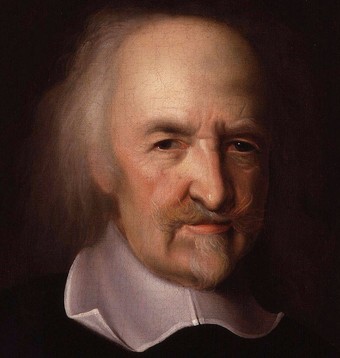

Portrait of Thomas Hobbes by John Michael Wright, National Portrait Gallery, London

Thomas Hobbes’ 1651 book Leviathan established social contract theory, the foundation of most later western political philosophy. Though on rational grounds a champion of absolutism for the sovereign, Hobbes also developed some of the fundamentals of European liberal thought: the right of the individual; the natural equality of all men; the artificial character of the political order (which led to the later distinction between civil society and the state); the view that all legitimate political power must be “representative” and based on the consent of the people; and a liberal interpretation of law that leaves people free to do whatever the law does not explicitly forbid.

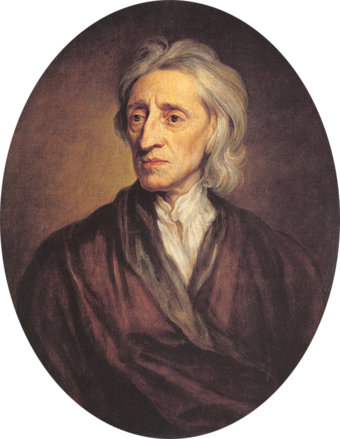

The most famous natural right formulation comes from John Locke in his Second Treatise, when he introduces the state of nature. For Locke, the law of nature is grounded on mutual security, or the idea that one cannot infringe on another’s natural rights, as every man is equal and has the same inalienable rights. These natural rights include perfect equality and freedom and the right to preserve life and property. Such fundamental rights could not be surrendered in the social contract. Another 17th-century Englishman, John Lilburne (known as Freeborn John) argued for level human rights that he called “freeborn rights,” which he defined as being rights that every human being is born with, as opposed to rights bestowed by government or by human law. The distinction between alienable and unalienable rights was introduced by Francis Hutcheson, who argued that “Unalienable Rights are essential Limitations in all Governments.” In the German Enlightenment, Georg Hegel gave a highly developed treatment of the inalienability argument. Like Hutcheson, he based the theory of inalienable rights on the de facto inalienability of those aspects of personhood that distinguish persons from things. A thing, like a piece of property, can in fact be transferred from one person to another. According to Hegel, the same would not apply to those aspects that make one a person. Consequently, the question of whether property is an aspect of natural rights remains a matter of debate.

Thomas Paine further elaborated on natural rights in his influential work Rights of Man (1791), emphasizing that rights cannot be granted by any charter because this would legally imply they can also be revoked, and under such circumstances, they would be reduced to privileges.

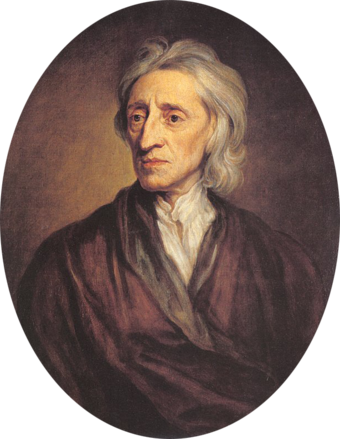

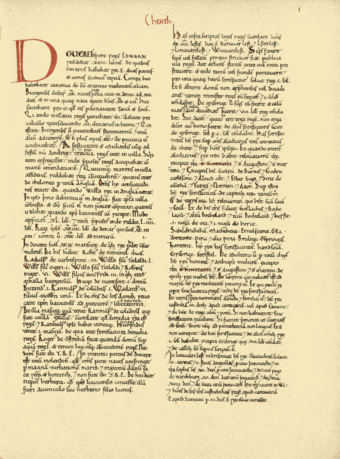

Portrait of John Locke, by Sir Godfrey Kneller, Britain, 1697,

State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

The most famous natural right formulation comes from John Locke in his Second Treatise. For Locke, the natural rights include perfect equality and freedom, and the right to preserve life and property.

Natural Rights, Slavery, and Abolitionism

In discussion of social contract theory, “inalienable rights” were those rights that could not be surrendered by citizens to the sovereign. Such rights were thought to be natural rights, independent of positive law. Some social contract theorists reasoned, however, that in the natural state only the strongest could benefit from their rights. Thus, people form an implicit social contract, ceding their natural rights to the authority to protect the people from abuse, and living henceforth under the legal rights of that authority.

Many historical apologies for slavery and illiberal government were based on explicit or implicit voluntary contracts to alienate any natural rights to freedom and self-determination.

Locke argued against slavery on the basis that enslaving yourself goes against the law of nature; you cannot surrender your own rights, your freedom is absolute and no one can take it from you. Additionally, Locke argues that one person cannot enslave another because it is morally reprehensible, although he introduces a caveat by saying that enslavement of a lawful captive in time of war would not go against one’s natural rights.

The de facto inalienability arguments of Hutcheson and his predecessors provided the basis for the anti-slavery movement to argue not simply against involuntary slavery but against any explicit or implied contractual forms of slavery. Any contract that tried to legally alienate such a right would be inherently invalid. Similarly, the argument was used by the democratic movement to argue against any explicit or implied social contracts of subjection by which a people would supposedly alienate their right of self-government to a sovereign.

19.2: The Age of Discovery

19.2.1: Europe’s Early Trade Links

A prelude to the Age of Discovery was a series of European land expeditions

across Eurasia in the late Middle Ages. These expeditions were undertaken by a number of explorers, including Marco Polo, who left behind a detailed and inspiring record of his travels across Asia.

Learning Objective

Understand the exploration of Eurasia in the Middle Ages by Marco Polo, and why it was a prelude to the advent of the Age of Discovery in the 15th Century

Key Points

- European medieval knowledge about Asia beyond the reach of Byzantine Empire was sourced in partial reports, often obscured by legends.

-

In 1154, Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi

created what would be known as the Tabula Rogeriana—a description

of the world and world map. It contains

maps showing the Eurasian continent in its entirety, but only the northern part

of the African continent. It remained the most accurate world map for the next

three centuries. -

Indian Ocean trade routes were sailed by Arab

traders. Between 1405 and 1421, the Yongle Emperor of Ming China sponsored a

series of long range tributary missions. The fleets visited Arabia, East Africa,

India, Maritime Southeast Asia, and Thailand. -

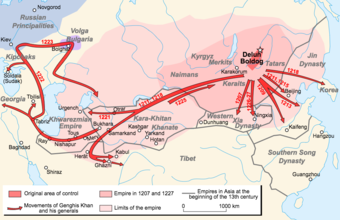

A series

of European expeditions crossing Eurasia by land in the late Middle Ages marked a prelude to the Age of Discovery.

Although the Mongols had threatened Europe with pillage and destruction, Mongol

states also unified much of Eurasia and, from 1206 on, the Pax

Mongolica allowed safe trade routes and communication lines stretching

from the Middle East to China. -

Christian

embassies were sent as far as Karakorum during the Mongol invasions of Syria. The first of these

travelers was Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, who journeyed to Mongolia and back

from 1241 to 1247. Others traveled to various regions of Asia between 13th and the third quarter of the 15th centuries; these travelers included Russian Yaroslav of Vladimir

and his sons Alexander Nevsky and Andrey II of Vladimir, French André

de Longjumeau and Flemish William of Rubruck, Moroccan

Ibn Battuta, and Italian Niccolò de’ Conti. -

Marco Polo, a Venetian merchant, dictated an

account of journeys throughout Asia from 1271 to 1295. Although he was not the first European to

reach China, he was the first to leave a detailed chronicle of his

experience. The book inspired Christopher Columbus and many other travelers in the following Age of Discovery.

Key Terms

- Pax Mongolica

-

A historiographical term, modeled after the original phrase Pax Romana, which describes the stabilizing effects of the conquests of the Mongol Empire on the social, cultural, and economic life of the inhabitants of the vast Eurasian territory that the Mongols conquered in the 13th and 14th centuries. The term is used to describe the eased communication and commerce that the unified administration helped to create, and the period of relative peace that followed the Mongols’ vast conquests.

- Tabula Rogeriana

-

A book containing a description of the world and world map created by the Arab geographer, Muhammad al-Idrisi, in 1154. Written in Arabic, it is divided into seven climate zones and contains maps showing the Eurasian continent in its entirety, but only the northern part of the African continent. The map is oriented with the North at the bottom. It remained the most accurate world map for the next three centuries.

- Maritime republics

-

City-states that flourished in Italy and across the Mediterranean. From the 10th to the 13th centuries, they built fleets of ships both for their own protection and to support extensive trade networks across the Mediterranean, giving them an essential role in the Crusades.

Background

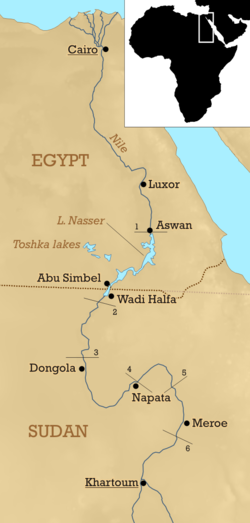

European medieval knowledge about Asia beyond the reach of Byzantine Empire was sourced in partial reports, often obscured by legends, dating back from the time of the conquests of Alexander the Great and his successors. In 1154, Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi created what would be known as the Tabula Rogeriana at the court of King Roger II of Sicily. The book, written in Arabic, is a description of the world and world map. It is divided into seven climate zones and contains maps showing the Eurasian continent in its entirety, but only the northern part of the African continent. It remained the most accurate world map for the next three centuries, but it also demonstrated that Africa was only partially known to either Christians, Genoese and Venetians, or the Arab seamen, and its southern extent was unknown. Knowledge about the Atlantic African coast was fragmented, and derived mainly from old Greek and Roman maps based on Carthaginian knowledge, including the time of Roman exploration of Mauritania. The Red Sea was barely known and only trade links with the Maritime republics, the Republic of Venice especially, fostered collection of accurate maritime knowledge.

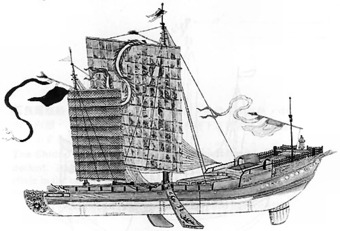

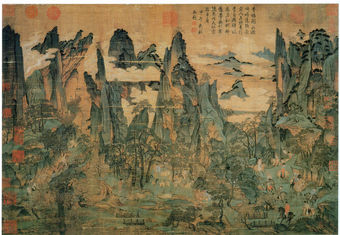

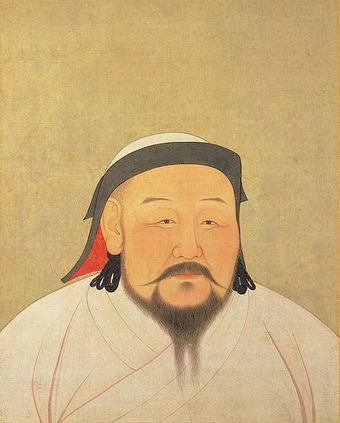

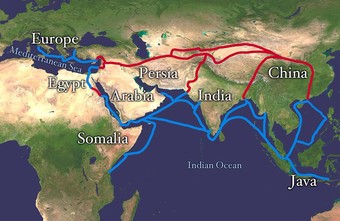

Indian Ocean trade routes were sailed by Arab traders. Between 1405 and 1421, the Yongle Emperor of Ming China sponsored a series of long-range tributary missions. The fleets visited Arabia, East Africa, India, Maritime Southeast Asia, and Thailand. But the journeys, reported by Ma Huan, a Muslim voyager and translator, were halted abruptly after the emperor’s death, and were not followed up, as the Chinese Ming Dynasty retreated in the haijin, a policy of isolationism, having limited maritime trade.

Prelude to the Age of Discovery

A series of European expeditions crossing Eurasia by land in the late Middle Ages marked a prelude to the Age of Discovery. Although the Mongols had threatened Europe with pillage and destruction, Mongol states also unified much of Eurasia and, from 1206 on, the Pax Mongolica allowed safe trade routes and communication lines stretching from the Middle East to China. A series of Europeans took advantage of these in order to explore eastward. Most were Italians, as trade between Europe and the Middle East was controlled mainly by the Maritime republics.

Christian embassies were sent as far as Karakorum during the Mongol invasions of Syria, from which they gained a greater understanding of the world. The first of these travelers was Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, who journeyed to Mongolia and back from 1241 to 1247. About the same time, Russian prince Yaroslav of Vladimir, and subsequently his sons, Alexander Nevsky and Andrey II of Vladimir, traveled to the Mongolian capital. Though having strong political implications, their journeys left no detailed accounts. Other travelers followed, like French André de Longjumeau and Flemish William of Rubruck, who reached China through Central Asia. From 1325 to 1354, a Moroccan scholar from Tangier, Ibn Battuta, journeyed through North Africa, the Sahara desert, West Africa, Southern Europe, Eastern Europe, the Horn of Africa, the Middle East and Asia, having reached China. In 1439, Niccolò de’ Conti published an account of his travels as a Muslim merchant to India and Southeast Asia and, later in 1466-1472, Russian merchant Afanasy Nikitin of Tver travelled to India.

Marco Polo, a Venetian merchant, dictated an account of journeys throughout Asia from 1271 to 1295. His travels are recorded in Book of the Marvels of the World, (also known as The Travels of Marco Polo, c. 1300),

a book which did much to introduce Europeans to Central Asia and China. Marco Polo was not the first European to reach China, but he was the first to leave a detailed chronicle of his experience. The book inspired Christopher Columbus and many other travelers.

The Travels of Marco Polo

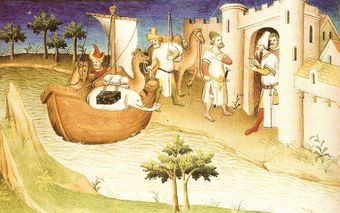

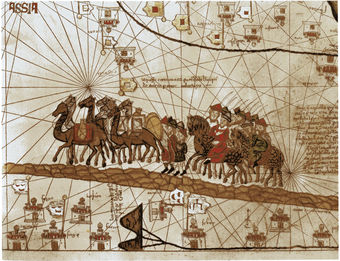

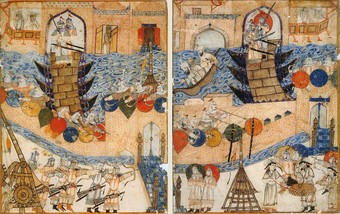

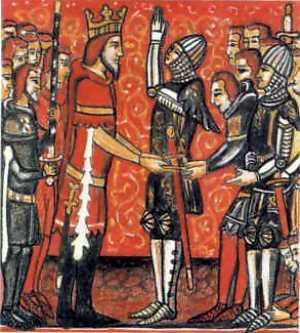

Marco Polo traveling, miniature from the book The Travels of Marco Polo (Il milione), originally published during Polo’s lifetime (c. 1254-January 8, 1324), but frequently reprinted and translated.

The Age of Discovery

The geographical exploration of the late Middle Ages eventually led to what today is known as the Age of Discovery: a loosely defined European historical period, from the 15th century to the 18th century, that witnessed extensive overseas exploration emerge as a powerful factor in European culture and globalization. Many lands previously unknown to Europeans were discovered during this period, though most were already inhabited, and, from the perspective of non-Europeans, the period was not one of discovery, but one of invasion and the arrival of settlers from a previously unknown continent. Global exploration started with the successful Portuguese travels to the Atlantic archipelagos of Madeira and the Azores, the coast of Africa, and the sea route to India in 1498; and, on behalf of the Crown of Castile (Spain), the trans-Atlantic Voyages of Christopher Columbus between 1492 and 1502, as well as the first circumnavigation of the globe in 1519-1522. These discoveries led to numerous naval expeditions across the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific oceans, and land expeditions in the Americas, Asia, Africa, and Australia that continued into the late 19th century, and ended with the exploration of the polar regions in the 20th century.

19.2.2: Portuguese Explorers

During the 15th and 16th centuries, Portuguese explorers were at the forefront of European overseas exploration, which led them to reach India, establish multiple trading posts in Asia and Africa, and settle what would become Brazil, creating one of the most powerful empires.

Learning Objective

Compare the Portuguese Atlantic explorations from 1415-1488 with the Indian Exploration, led by Vasco da Gama from 1497-1542

Key Points

-

Portuguese sailors were at

the vanguard of European overseas exploration, discovering and mapping the

coasts of Africa, Asia, and Brazil. As early as 1317, King Denis made an

agreement with Genoese merchant sailor Manuel Pessanha, laying the basis for the Portuguese Navy and the establishment

of a powerful Genoese merchant community in Portugal. -

In 1415, the city of Ceuta

was occupied by the Portuguese in an effort to control

navigation of the African coast. Henry the Navigator, aware of profit possibilities in the Saharan trade routes, invested

in sponsoring voyages that, within two decades of exploration, allowed Portuguese ships to bypass the Sahara. -

The

Portuguese goal of finding a sea route to Asia was finally

achieved in a ground-breaking voyage commanded by Vasco da Gama, who reached Calicut in western India in 1498, becoming the first European to reach India. -

The

second voyage to India was dispatched in 1500 under Pedro Álvares Cabral. While

following the same south-westerly route as Gama across the Atlantic Ocean,

Cabral made landfall on the Brazilian coast—the territory that he recommended Portugal settle.

- Portugal’s purpose in the Indian Ocean was to ensure the monopoly of the spice

trade. Taking advantage of the rivalries that pitted Hindus against Muslims,

the Portuguese established several forts and trading posts between 1500 and

1510. -

Portugal established

trading ports at far-flung locations like Goa, Ormuz, Malacca, Kochi, the

Maluku Islands, Macau, and Nagasaki. Guarding its trade from both European and

Asian competitors, it dominated not only the trade between Asia and Europe, but

also much of the trade between different regions of Asia, such as India, Indonesia,

China, and Japan.

Key Terms

- Cape of Good Hope

-

A rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula, South Africa, named because of the great optimism engendered by the opening of a sea route to India and the East.

- Vasco da Gama

-

A Portuguese explorer and one of the most famous and celebrated explorers from the Age of Discovery; the first European to reach India by sea.

Introduction

Portuguese sailors were at the vanguard of European overseas exploration, discovering and mapping the coasts of Africa, Asia, and Brazil. As early as 1317, King Denis made an agreement with Genoese merchant sailor Manuel Pessanha (Pesagno), appointing him first Admiral with trade privileges with his homeland, in return for twenty war ships and crews, with the goal of defending the country against Muslim pirate raids. This created the basis for the Portuguese Navy and the establishment of a Genoese merchant community in Portugal.

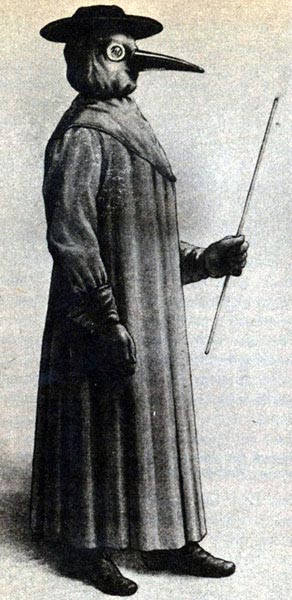

In the second half of the 14th century, outbreaks of bubonic plague led to severe depopulation; the economy was extremely localized in a few towns, unemployment rose, and migration led to agricultural land abandonment. Only the sea offered alternatives, with most people settling in fishing and trading in coastal areas. Between 1325-1357, Afonso IV of Portugal granted public funding to raise a proper commercial fleet, and ordered the first maritime explorations, with the help of Genoese, under command of admiral Pessanha. In 1341, the Canary Islands, already known to Genoese, were officially explored under the patronage of the Portuguese king, but in 1344, Castile disputed them, further propelling the Portuguese navy efforts.

Atlantic Exploration

In 1415, the city of Ceuta (north coast of Africa)

was occupied by the Portuguese aiming to control navigation of the African coast. Young Prince Henry the Navigator was there and became aware of profit possibilities in the Saharan trade routes. He invested in sponsoring voyages down the coast of Mauritania, gathering a group of merchants, shipowners, stakeholders, and participants interested in the sea lanes.

Henry the Navigator took the lead role in encouraging Portuguese maritime exploration, until his death in 1460. At the time, Europeans did not know what lay beyond Cape Bojador on the African coast.

In 1419, two of Henry’s captains, João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira, were driven by a storm to Madeira, an uninhabited island off the coast of Africa, which had probably been known to Europeans since the 14th century. In 1420, Zarco and Teixeira returned with Bartolomeu Perestrelo and began Portuguese settlement of the islands.

A Portuguese attempt to capture Grand Canary, one of the nearby Canary Islands, which had been partially settled by Spaniards in 1402, was unsuccessful and met with protests from Castile. Around the same time, the Portuguese began to explore the North African coast.

Diogo Silves reached the Azores island of Santa Maria in 1427, and in the following years, Portuguese discovered and settled the rest of the Azores. Within two decades of exploration, Portuguese ships bypassed the Sahara.

In 1443, Prince Pedro, Henry’s brother, granted him the monopoly of navigation, war, and trade in the lands south of Cape Bojador. Later, this monopoly would be enforced by two Papal bulls (1452 and 1455), giving Portugal the trade monopoly for the newly appropriated territories, laying the foundations for the Portuguese empire.

India and Brazil

The long-standing Portuguese goal of finding a sea route to Asia was finally achieved in a ground-breaking voyage commanded by Vasco da Gama. His squadron left Portugal in 1497, rounded the Cape and continued along the coast of East Africa, where a local pilot was brought on board who guided them across the Indian Ocean, reaching Calicut in western India in May 1498. Reaching the legendary Indian spice routes unopposed helped the Portuguese improve their economy that, until Gama, was mainly based on trades along Northern and coastal West Africa. These spices were at first mostly pepper and cinnamon, but soon included other products, all new to Europe. This led to a commercial monopoly for several decades.

The second voyage to India was dispatched in 1500 under Pedro Álvares Cabral. While following the same south-westerly route as Gama across the Atlantic Ocean, Cabral made landfall on the Brazilian coast. This was probably an accident but it has been speculated that the Portuguese knew of Brazil’s existence. Cabral recommended to the Portuguese king that the land be settled, and two follow-up voyages were sent in 1501 and 1503. The land was found to be abundant in pau-brasil, or brazilwood, from which it later inherited its name, but the failure to find gold or silver meant that for the time being Portuguese efforts were concentrated on India.

Gama’s voyage was significant and paved the way for the Portuguese to establish a long-lasting colonial empire in Asia. The route meant that the Portuguese would not need to cross the highly disputed Mediterranean, or the dangerous Arabian Peninsula, and that the entire voyage would be made by sea.

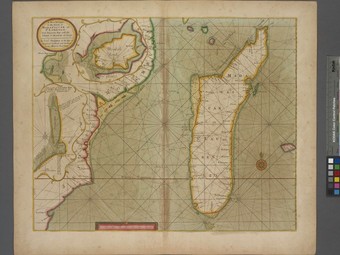

First Voyage of Vasco da Gama

The route followed in Vasco da Gama’s first voyage (1497-1499). Gama’s squadron left Portugal in 1497, rounded the Cape and continued along the coast of East Africa. They reached Calicut in western India in May 1498.

Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia Explorations

The aim of Portugal in the Indian Ocean was to ensure the monopoly of the spice trade. Taking advantage of the rivalries that pitted Hindus against Muslims, the Portuguese established several forts and trading posts between 1500 and 1510. After the victorious sea Battle of Diu, Turks and Egyptians withdrew their navies from India, setting the Portuguese trade dominance for almost a century, and greatly contributing to the growth of the Portuguese Empire. It also marked the beginning of the European colonial dominance in Asia. A second Battle of Diu in 1538 ended Ottoman ambitions in India, and confirmed Portuguese hegemony in the Indian Ocean.

In 1511, Albuquerque sailed to Malacca in Malaysia, the most important eastern point in the trade network, where Malay met Gujarati, Chinese, Japanese, Javan, Bengali, Persian, and Arabic traders. The port of Malacca became the strategic base for Portuguese trade expansion with China and Southeast Asia. Eventually, the Portuguese Empire expanded into the Persian Gulf as Portugal contested control of the spice trade with the Ottoman Empire. In a shifting series of alliances, the Portuguese dominated much of the southern Persian Gulf for the next hundred years.

A Portuguese explorer funded by the Spanish Crown, Ferdinand Magellan, organized the Castilian (Spanish) expedition to the East Indies from 1519 to 1522. Selected by King Charles I of Spain to search for a westward route to the Maluku Islands (the “Spice Islands,” today’s Indonesia), he headed south through the Atlantic Ocean to Patagonia, passing through the Strait of Magellan into a body of water he named the “peaceful sea” (the modern Pacific Ocean). Despite a series of storms and mutinies, the expedition reached the Spice Islands in 1521, and returned home via the Indian Ocean to complete the first circuit of the globe.

In 1525, after Magellan’s expedition, Spain, under Charles V, sent an expedition to colonize the Maluku islands. García Jofre de Loaísa reached the islands and the conflict with the Portuguese was inevitable, starting nearly a decade of skirmishes. An agreement was reached only with the Treaty of Zaragoza (1529), attributing the Maluku to Portugal, and the Philippines to Spain.

Portugal established trading ports at far-flung locations like Goa, Ormuz, Malacca, Kochi, the Maluku Islands, Macau, and Nagasaki. Guarding its trade from both European and Asian competitors, it dominated not only the trade between Asia and Europe, but also much of the trade between different regions of Asia, such as India, Indonesia, China, and Japan. Jesuit missionaries followed the Portuguese to spread Roman Catholic Christianity to Asia, with mixed success.

19.2.3: Spanish Exploration

The voyages of Christopher Columbus initiated the European exploration and colonization of the American continents that eventually turned Spain into the most powerful European empire.

Learning Objective

Outline the successes and failures of Christopher Columbus during his four voyages to the Americas

Key Points

-

Only late in the 15th century

did an emerging modern Spain become fully committed to the search for new trade

routes overseas. In 1492, Christopher Columbus’s expedition was funded in the hope of bypassing

Portugal’s monopoly on west African sea routes, to reach “the Indies.” -

On the evening of August 3, 1492, Columbus

departed from Palos de la Frontera with three ships. Land was sighted on October 12, 1492 and Columbus called the island (now

The Bahamas) San Salvador, in what he thought to be the “West

Indies.” Following

the first American voyage, Columbus made three more. - A division of

influence became necessary to avoid conflict between the Spanish and

Portuguese. An agreement was reached in 1494, with the Treaty of Tordesillas

dividing the world between the two powers. -

After

Columbus, the Spanish colonization of the Americas was led by a series of

soldier-explorers, called conquistadors. The Spanish forces, in addition to

significant armament and equestrian advantages, exploited the rivalries between

competing indigenous peoples, tribes, and nations. -

One

of the most accomplished conquistadors was Hernán Cortés, who achieved the Spanish conquest of the

Aztec Empire. Of equal

importance was the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire under

Francisco Pizarro. -

In

1565, the first permanent Spanish settlement in the Philippines was founded, which added a critical Asian post to the empire. The

Manilla Galleons shipped goods from all over Asia, across the Pacific to

Acapulco on the coast of Mexico.

Key Terms

- Christopher Columbus

-

An Italian explorer, navigator, and colonizer who completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean under the monarchy of Spain, which led to general European awareness of the American continents.

- Treaty of Tordesillas

-

A 1494 treaty that divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between Portugal and the Crown of Castile, along a meridian 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands, off the west coast of Africa. This line of demarcation was about halfway between the Cape Verde islands (already Portuguese) and the islands entered by Christopher Columbus on his first voyage (claimed for Castile and León).

- Treaty of Zaragoza

-

A 1529 peace treaty between the Spanish Crown and Portugal that defined the areas of Castilian (Spanish) and Portuguese influence in Asia to resolve the “Moluccas issue,” when both kingdoms claimed the Moluccas islands for themselves, considering it within their exploration area established by the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. The conflict sprang in 1520, when the expeditions of both kingdoms reached the Pacific Ocean, since there was not a set limit to the east.

- reconquista

-

A period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula, spanning approximately 770 years, between the initial Umayyad conquest of Hispania in the 710s, and the fall of the Emirate of Granada, the last Islamic state on the peninsula, to expanding Christian kingdoms in 1492.

Introduction

While Portugal led European explorations of non-European territories, its neighboring fellow Iberian rival, Castile, embarked upon its own mission to create an overseas empire. It began to establish its rule over the Canary Islands, located off the West African coast, in 1402, but then became distracted by internal Iberian politics and the repelling of Islamic invasion attempts and raids through most of the 15th century. Only late in the century, following the unification of the crowns of Castile and Aragon and the completion of the reconquista, did an emerging modern Spain become fully committed to the search for new trade routes overseas. In 1492, the joint rulers conquered the Moorish kingdom of Granada, which had been providing Castile with African goods through tribute, and decided to fund Christopher Columbus’s expedition in the hope of bypassing Portugal’s monopoly on west African sea routes, to reach “the Indies” (east and south Asia) by traveling west. Twice before, in 1485 and 1488, Columbus had presented the project to king John II of Portugal, who rejected it.

Columbus’s Voyages

On the evening of August 3, 1492, Columbus departed from Palos de la Frontera with three ships: Santa María, Pinta (the Painted) and Santa Clara. Columbus first sailed to the Canary Islands, where he restocked for what turned out to be a five-week voyage across the ocean, crossing a section of the Atlantic that became known as the Sargasso Sea. Land was sighted on October 12, 1492, and Columbus called the island (now The Bahamas) San Salvador, in what he thought to be the “West Indies.” He also explored the northeast coast of Cuba and the northern coast of Hispaniola. Columbus left 39 men behind and founded the settlement of La Navidad in what is present-day Haiti.

Following the first American voyage, Columbus made three more. During the second, 1493, voyage, he enslaved 560 native Americans, in spite of the Queen’s explicit opposition to the idea. Their transfer to Spain resulted in the death and disease of hundreds of the captives. The object of the third voyage was to verify the existence of a continent that King John II of Portugal claimed was located to the southwest of the Cape Verde Islands. In 1498, Columbus left port with a fleet of six ships. He explored the Gulf of Paria, which separates Trinidad from mainland Venezuela, and then the mainland of South America. Columbus described these new lands as belonging to a previously unknown new continent, but he pictured them hanging from China. Finally, the fourth voyage, nominally in search of a westward passage to the Indian Ocean, left Spain in 1502. Columbus spent two months exploring the coasts of Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, before arriving in Almirante Bay, Panama. After his ships sustained serious damage in a storm off the coast of Cuba, Columbus and his men remained stranded on Jamaica for a year. Help finally arrived and Columbus and his men arrived in Castile in November 1504.

The Treaty of Tordesillas

Shortly after Columbus’s arrival from the “West Indies,” a division of influence became necessary to avoid conflict between the Spanish and Portuguese. An agreement was reached in 1494 with the Treaty of Tordesillas, which divided the world between the two powers. In the treaty, the Portuguese received everything outside Europe east of a line that ran 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands (already Portuguese), and the islands reached by Christopher Columbus on his first voyage (claimed for Spain—Cuba, and Hispaniola). This gave them control over Africa, Asia, and eastern South America (Brazil). The Spanish (Castile) received everything west of this line, territory that was still almost completely unknown, and proved to be mostly the western part of the Americas, plus the Pacific Ocean islands.

“The First Voyage”, chromolithograph by L. Prang & Co., published by The Prang Educational Co., Boston, 1893

A scene of Christopher Columbus bidding farewell to the Queen of Spain on his departure for the New World, August 3, 1492.

Further Explorations of the Americas

After Columbus, the Spanish colonization of the Americas was led by a series of soldier-explorers, called conquistadors. The Spanish forces, in addition to significant armament and equestrian advantages, exploited the rivalries between competing indigenous peoples, tribes, and nations, some of which were willing to form alliances with the Spanish in order to defeat their more powerful enemies, such as the Aztecs or Incas—a tactic that would be extensively used by later European colonial powers. The Spanish conquest was also facilitated by the spread of diseases (e.g., smallpox), common in Europe but never present in the New World, which reduced the indigenous populations in the Americas. This caused labor shortages for plantations and public works, and so the colonists initiated the Atlantic slave trade.

One of the most accomplished conquistadors was Hernán Cortés, who led a relatively small Spanish force, but with local translators and the crucial support of thousands of native allies, achieved the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in the campaigns of 1519-1521 (present day Mexico). Of equal importance was the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire. After years of preliminary exploration and military skirmishes, 168 Spanish soldiers under Francisco Pizarro, and their native allies, captured the Sapa Inca Atahualpa in the 1532 Battle of Cajamarca. It was the first step in a long campaign that took decades of fighting, but ended in Spanish victory in 1572 and colonization of the region as the Viceroyalty of Peru. The conquest of the Inca Empire led to spin-off campaigns into present-day Chile and Colombia, as well as expeditions towards the Amazon Basin.

Further Spanish settlements were progressively established in the New World: New Granada in the 1530s (later in the Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1717 and present day Colombia), Lima in 1535 as the capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru, Buenos Aires in 1536 (later in the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata in 1776), and Santiago in 1541. Florida was colonized in 1565 by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés.

The Portuguese Ferdinand Magellan died while in the Philippines commanding a Castilian expedition in 1522, which was the first to circumnavigate the globe. The Basque commander, Juan Sebastián Elcano, would lead the expedition to success. Therefore, Spain sought to enforce their rights in the Moluccan islands, which led a conflict with the Portuguese, but the issue was resolved with the Treaty of Zaragoza (1525). In 1565, the first permanent Spanish settlement in the Philippines was founded by Miguel López de Legazpi, and the service of Manila Galleons was inaugurated. The Manilla Galleons shipped goods from all over Asia across the Pacific to Acapulco on the coast of Mexico. From there, the goods were transshipped across Mexico to the Spanish treasure fleets, for shipment to Spain. The Spanish trading post of Manila was established to facilitate this trade in 1572.

19.2.4: England and the High Seas

Throughout the 17th century, the British established numerous successful American colonies and dominated the Atlantic slave trade, which eventually led to creating the most powerful European empire.

Learning Objective

Explain why England was interested in establishing a maritime empire

Key Points

-

In 1496, King Henry VII of England, following

the successes of Spain and Portugal in overseas exploration, commissioned John

Cabot to lead a voyage to discover a route

to Asia via the North Atlantic. Cabot sailed in 1497 and he successfully made

landfall on the coast of Newfoundland but did not establish a colony. -

In 1562, the English Crown encouraged the

privateers John Hawkins and Francis Drake to engage in slave-raiding attacks

against Spanish and Portuguese ships off the coast of West Africa, with the aim

of breaking into the Atlantic trade system. Drake carried out the second

circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580. -

In

1578, Elizabeth I granted a patent to Humphrey Gilbert for discovery and

overseas exploration. In 1583, he

claimed the harbor of Newfoundland

for England, but no settlers were left

behind. Gilbert did not survive the return journey to England, and was

succeeded by his half-brother, Walter Raleigh, who founded the colony of Roanoke, the first but failed British settlement. - In the first decade of the 17th century, English attention shifted from preying on other

nations’ colonial infrastructures to the business of establishing its own

overseas colonies. The Caribbean initially provided England’s most important

and lucrative colonies. -

The

introduction of the 1951 Navigation Acts led to war with the Dutch Republic, which was the first war

fought largely, on the English side, by purpose-built, state-owned warships.

After the English monarchy was restored in 1660, Charles II re-established the

Navy, but as a national institution known, since then, as “The Royal Navy.” - Throughout the 17th century, the British established numerous successful American colonies, all based largely on slave labor. The colonization of the Americas and the participation in the Atlantic slave trade allowed the British to gradually build the most powerful European empire.

Key Terms

- First Anglo-Dutch War

-

A 1652-1654 conflict fought entirely at sea between the navies of the Commonwealth of England and the United Provinces of the Netherlands. Caused by disputes over trade, the war began with English attacks on Dutch merchant shipping, but expanded to vast fleet actions. Ultimately, it resulted in the English Navy gaining control of the seas around England, and forced the Dutch to accept an English monopoly on trade with England and her colonies.

- Navigation Acts

-

A series of English laws that restricted the use of foreign ships for trade between every country except England. They were first enacted in 1651, and were repealed nearly 200 years later in 1849. They reflected the policy of mercantilism, which sought to keep all the benefits of trade inside the empire, and minimize the loss of gold and silver to foreigners.

- Roanoke

-

Also known as the Lost Colony; a late 16th-century attempt by Queen Elizabeth I to establish a permanent English settlement in the Americas. The colony was founded by Sir Walter Raleigh. The colonists disappeared during the Anglo-Spanish War, three years after the last shipment of supplies from England.

- Plymouth

-

An English colonial venture in North America from 1620 to 1691, first surveyed and named by Captain John Smith. The settlement served as the capital of the colony and at its height, it occupied most of the southeastern portion of the modern state of Massachusetts.

- Jamestown

-

The first permanent English settlement in the Americas, established by the Virginia Company of London as “James Fort” on May 4, 1607, and considered permanent after brief abandonment in 1610. It followed several earlier failed attempts, including the Lost Colony of Roanoke.

Introduction

The foundations of the British Empire were laid when England and Scotland were separate kingdoms. In 1496, King Henry VII of England, following the successes of Spain and Portugal in overseas exploration, commissioned John Cabot (Venetian born as

Giovanni Caboto) to lead a voyage to discover a route to Asia via the North Atlantic.

Spain put limited efforts into exploring the northern part of the Americas, as its resources were concentrated in Central and South America where more wealth had been found.

Cabot sailed in 1497, five years after Europeans reached America, and although he successfully made landfall on the coast of Newfoundland (mistakenly believing, like Christopher Columbus, that he had reached Asia), there was no attempt to found a colony. Cabot led another voyage to the Americas the following year, but nothing was heard of his ships again.

The Early Empire

No further attempts to establish English colonies in the Americas were made until well into the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, during the last decades of the 16th century. In the meantime, the Protestant Reformation had turned England and Catholic Spain into implacable enemies. In 1562, the English Crown encouraged the privateers John Hawkins and Francis Drake to engage in slave-raiding attacks against Spanish and Portuguese ships off the coast of West Africa, with the aim of breaking into the Atlantic trade system. Drake carried out the second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580, and was the first to complete the voyage as captain while leading the expedition throughout the entire circumnavigation. With his incursion into the Pacific, he inaugurated an era of privateering and piracy in the western coast of the Americas—an area that had previously been free of piracy.

In 1578, Elizabeth I granted a patent to Humphrey Gilbert for discovery and overseas exploration. That year, Gilbert sailed for the West Indies with the intention of engaging in piracy and establishing a colony in North America, but the expedition was aborted before it had crossed the Atlantic. In 1583, he embarked on a second attempt, on this occasion to the island of Newfoundland whose harbor he formally claimed for England, although no settlers were left behind. Gilbert did not survive the return journey to England, and was succeeded by his half-brother, Walter Raleigh, who was granted his own patent by Elizabeth in 1584. Later that year, Raleigh founded the colony of Roanoke on the coast of present-day North Carolina, but lack of supplies caused the colony to fail.

Empire in the Americas

In 1603, James VI, King of Scots, ascended (as James I) to the English throne, and in 1604 negotiated the Treaty of London, ending hostilities with Spain. Now at peace with its main rival, English attention shifted from preying on other nations’ colonial infrastructures, to the business of establishing its own overseas colonies. The Caribbean initially provided England’s most important and lucrative colonies. Colonies in Guiana, St Lucia, and Grenada failed but settlements were successfully established in St. Kitts (1624), Barbados (1627), and Nevis (1628). The colonies soon adopted the system of sugar plantations, successfully used by the Portuguese in Brazil, which depended on slave labor, and—at first—Dutch ships, to sell the slaves and buy the sugar. To ensure that the increasingly healthy profits of this trade remained in English hands, Parliament decreed in the 1651 Navigation Acts that only English ships would be able to ply their trade in English colonies.

In 1655, England annexed the island of Jamaica from the Spanish, and in 1666 succeeded in colonizing the Bahamas.

African slaves working in 17th-century Virginia (tobacco cultivation), by an unknown artist, 1670

In 1672, the Royal African Company was inaugurated, receiving from King Charles a monopoly of the trade to supply slaves to the British colonies of the Caribbean. From the outset, slavery was the basis of the British Empire in the West Indies and later in North America. Until the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, Britain was responsible for the transportation of 3.5 million African slaves to the Americas, a third of all slaves transported across the Atlantic.

The introduction of the Navigation Acts led to war with the Dutch Republic. In the early stages of this First Anglo-Dutch War (1652-1654), the superiority of the large, heavily armed English ships was offset by superior Dutch tactical organization. English tactical improvements resulted in a series of crushing victories in 1653, bringing peace on favorable terms. This was the first war fought largely, on the English side, by purpose-built, state-owned warships. After the English monarchy was restored in 1660, Charles II re-established the navy, but from this point on, it ceased to be the personal possession of the reigning monarch, and instead became a national institution, with the title of “The Royal Navy.”

England’s first permanent settlement in the Americas was founded in 1607 in Jamestown, led by Captain John Smith and managed by the Virginia Company. Bermuda was settled and claimed by England as a result of the 1609 shipwreck there of the Virginia Company’s flagship. The Virginia Company’s charter was revoked in 1624 and direct control of Virginia was assumed by the crown, thereby founding the Colony of Virginia. In 1620, Plymouth was founded as a haven for puritan religious separatists, later known as the Pilgrims. Fleeing from religious persecution would become the motive of many English would-be colonists to risk the arduous trans-Atlantic voyage; Maryland was founded as a haven for Roman Catholics (1634), Rhode Island (1636) as a colony tolerant of all religions, and Connecticut (1639) for Congregationalists. The Province of Carolina was founded in 1663. With the surrender of Fort Amsterdam in 1664, England gained control of the Dutch colony of New Netherland, renaming it New York. In 1681, the colony of Pennsylvania was founded by William Penn. The American colonies were less financially successful than those of the Caribbean, but had large areas of good agricultural land and attracted far larger numbers of English emigrants who preferred their temperate climates.

From the outset, slavery was the basis of the British Empire in the West Indies. Until the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, Britain was responsible for the transportation of 3.5 million African slaves to the Americas, a third of all slaves transported across the Atlantic. In the British Caribbean, the percentage of the population of African descent rose from 25% in 1650 to around 80% in 1780, and in the 13 Colonies from 10% to 40% over the same period (the majority in the southern colonies). For the slave traders, the trade was extremely profitable, and became a major economic mainstay.

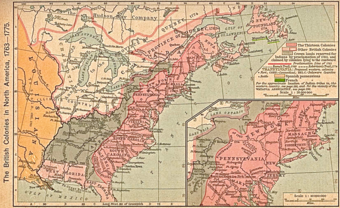

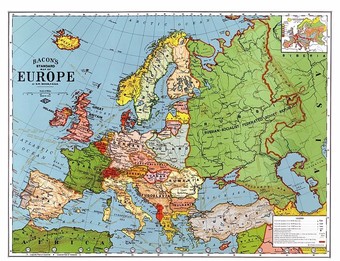

Map of the British colonies in North America, 1763 to 1775. First published in: Shepherd, William Robert (1911) “The British Colonies in North America, 1763–1765” in Historical Atlas, New York, United States: Henry Holt and Company, p. 194.

Although Britain was relatively late in its efforts to explore and colonize the New World, lagging behind Spain and Portugal, it eventually gained significant territories in North America and the Caribbean.

19.2.5: French Explorers

France established colonies in North America, the Caribbean, and India in the 17th century, and while it lost most of its American holdings to Spain and Great Britain before the end of the 18th century, it eventually expanded its Asian and African territories in the 19th century.

Learning Objective

Describe some of the discoveries made by French explorers

Key Points

-

Competing with Spain, Portugal, the Dutch Republic, and later Britain, France began to establish

colonies in North America, the Caribbean, and India in the 17th century.

Major French exploration of North America began under

the rule of Francis I of France. In 1524, he sent Italian-born Giovanni da

Verrazzano to explore the region between Florida and

Newfoundland for a route to the Pacific Ocean. -

In 1534, Francis sent Jacques Cartier on

the first of three voyages to explore the coast of Newfoundland and the St.

Lawrence River. Cartier founded New France and was the first European to travel inland in North America. - Cartier attempted to create the first permanent

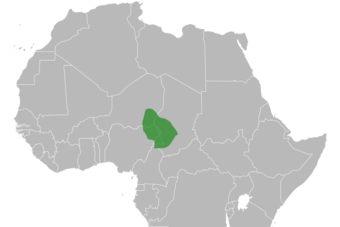

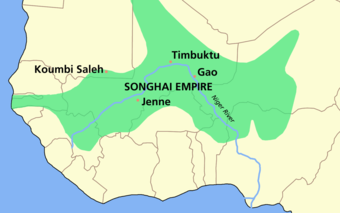

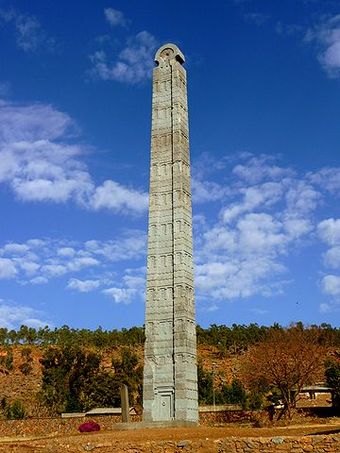

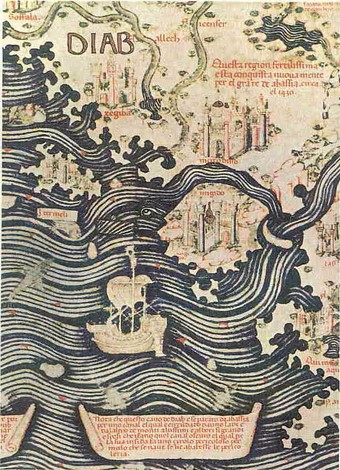

European settlement in North America at Cap-Rouge (Quebec City) in 1541, but the settlement was abandoned the next year. A number of