2.1: The Research Process

2.1.1: Defining the Problem

Defining a sociological problem helps frame a question to be addressed in the research process.

Learning Objective

Explain how the definition of the problem relates to the research process

Key Points

- The first step of the scientific method is to ask a question, describe a problem, and identify the specific area of interest. The topic should be narrow enough to study within the context of a particular test but also broad enough to have a more general practical or theoretical merit.

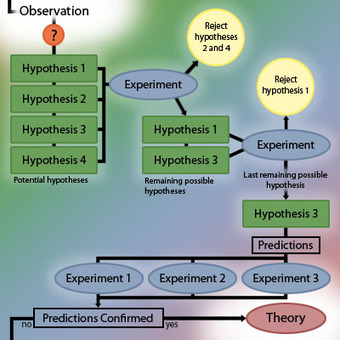

- For many sociologists, the goal is to conduct research which may be applied directly to social policy and welfare, while others focus primarily on refining the theoretical understanding of social processes. Subject matter ranges from the micro level to the macro level.

- Like other sciences, sociology relies on the systematic, careful collection of measurements or counts of relevant quantities to be considered valid. Given that sociology deals with topics that are often difficult to measure, this generally involves operationalizing relevant terms.

Key Terms

- operationalization

-

In humanities, operationalization is the process of defining a fuzzy concept so as to make the concept clearly distinguishable or measurable and to understand it in terms of empirical observations.

- operational definition

-

A showing of something — such as a variable, term, or object — in terms of the specific process or set of validation tests used to determine its presence and quantity.

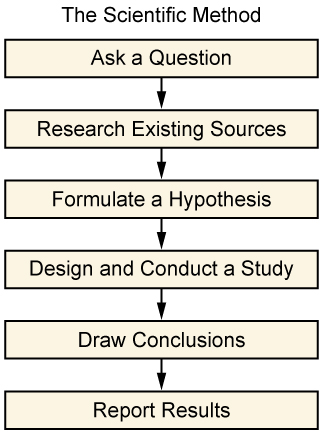

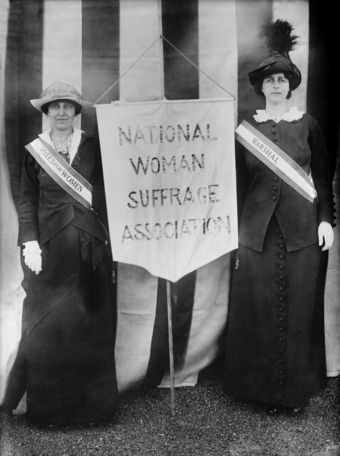

Defining the problem is necessarily the first step of the research process. After the problem and research question is defined, scientists generally gather information and other observations, form hypotheses, test hypotheses by collecting data in a reproducible manner, analyze and interpret that data, and draw conclusions that serve as a starting point for new hypotheses .

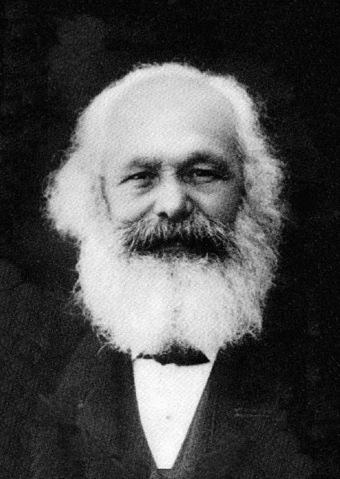

The Scientific Method is an Essential Tool in Research

This image lists the various stages of the scientific method.

The first step of the scientific method is to ask a question, describe a problem, and identify the specific area of interest. The topic should be narrow enough to study within the context of a particular test but also broad enough to have a more general practical or theoretical merit. For many sociologists, the goal is to conduct research which may be applied directly to social policy and welfare, while others focus primarily on refining the theoretical understanding of social processes. Subject matter ranges from the micro level of individual agency and interaction to the macro level of systems and the social structure.

Like other sciences, sociology relies on the systematic, careful collection of measurements or counts of relevant quantities to be considered valid. Given that sociology deals with topics that are often difficult to measure, this generally involves operationalizing relevant terms. Operationalization is a process that describes or defines a concept in terms of the physical or concrete steps it takes to objectively measure it, as opposed to some more vague, inexact, or idealized definition. The operational definition thus identifies an observable condition of the concept. By operationalizing a variable of the concept, all researchers can collect data in a systematic or replicable manner.

For example, intelligence cannot be directly quantified. We cannot say, simply by observing, exactly how much more intelligent one person is than another. But we can operationalize intelligence in various ways. For instance, we might administer an IQ test, which uses specific types of questions and scoring processes to give a quantitative measure of intelligence. Or we might use years of education as a way to operationalize intelligence, assuming that a person with more years of education is also more intelligent. Of course, others might dispute the validity of these operational definitions of intelligence by arguing that IQ or years of education are not good measures of intelligence. After all, a very intelligent person may not have the means or inclination to pursue higher education, or a less intelligent person may stay in school longer because they have trouble completing graduation requirements. In most cases, the way we choose to operationalize variables can be contested; few operational definitions are perfect. But we must use the best approximation we can in order to have some sort of measurable quantity for otherwise unmeasurable variables.

2.1.2: Reviewing the Literature

Sociological researchers review past work in their area of interest and include this “literature review” in the presentation of their research.

Learning Objective

Explain the purpose of literature reviews in sociological research

Key Points

- Literature reviews showcase researchers’ knowledge and understanding of the existing body of scholarship that relates to their research questions.

- A thorough literature review demonstrates the ability to research and synthesize. Furthermore, it provides a comprehensive overview of what is and is not known, and why the research in question is important to begin with.

- Literature reviews offer an explanation of how the researcher can contribute toward the existing body of scholarship by pursuing their own thesis or research question.

Key Terms

- disciplinary

-

Of or relating to an academic field of study.

- Theses

-

A dissertation or thesis is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author’s research and findings. The term thesis is also used to refer to the general claim of an essay or similar work.

- essay

-

A written composition of moderate length exploring a particular issue or subject.

A literature review is a logical and methodical way of organizing what has been written about a topic by scholars and researchers. Literature reviews can normally be found at the beginning of many essays, research reports, or theses. In writing the literature review, the purpose is to convey what a researcher has learned through a careful reading of a set of articles, books, and other relevant forms of scholarship related to the research question. Furthermore, creating a literature review allows researchers to demonstrate the ability to find significant articles, valid studies, or seminal books that are related to their topic as well as the analytic skill to synthesize and summarize different views on a topic or issue .

Library Research

Good literature reviews require exhaustive research. Online resources make this process easier, but researchers must still sift through stacks in libraries.

A strong literature review has the following properties:

- It is organized around issues, themes, factors, or variables that are related directly to the thesis or research question.

- It demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the body of knowledge by providing a good synthesis of what is and is not known about the subject in question, while also identifying areas of controversy and debate, or limitations in the literature sharing different perspectives.

- It indicates the theoretical framework that the researcher is working with.

- It places the formation of research questions in their historical and disciplinary context.

- It identifies the most important authors engaged in similar work.

- It offers an explanation of how the researcher can contribute toward the existing body of scholarship by pursuing their own thesis or research question .

2.1.3: Formulating the Hypothesis

A hypothesis is a potential answer to your research question; the research process helps you determine if your hypothesis is true.

Learning Objective

Explain how hypotheses are used in sociological research and the difference between dependent and independent variables

Key Points

- Hypotheses are testable explanations of a problem, phenomenon, or observation.

- Both quantitative and qualitative research involve formulating a hypothesis to address the research problem.

- Hypotheses that suggest a causal relationship involve at least one independent variable and at least one dependent variable; in other words, one variable which is presumed to affect the other.

- An independent variable is one whose value is manipulated by the researcher or experimenter.

- A dependent variable is a variable whose values are presumed to change as a result of changes in the independent variable.

Key Terms

- hypothesis

-

Used loosely, a tentative conjecture explaining an observation, phenomenon, or scientific problem that can be tested by further observation, investigation, or experimentation.

- dependent variable

-

In an equation, the variable whose value depends on one or more variables in the equation.

- independent variable

-

In an equation, any variable whose value is not dependent on any other in the equation.

Examples

- In his book Making Democracy Work, Robert Putnam developed a theory that social capital makes government more responsive. To demonstrate his theory, he tested several hypotheses about the ways that social capital influences government. One of his hypotheses was that regions with strong traditions of civic engagement would have more responsive, more democratic, and more efficient governments, regardless of the institutional form that government took. This is an example of a causal hypothesis. In this hypothesis, the independent (causal) variable is civic engagement and the dependent variables (or effects) are the qualities of government. To test this hypothesis, he compared twenty different regional Italian governments. All of these governments had similar institutions, but the regions had different traditions of civic engagement. In southern Italy, politics were traditionally patrimonial, whereas in northern Italy, politics were traditionally more open and citizens were more engaged. Putnam’s evidence supported his hypothesis: in the north, which had a stronger tradition of civic engagement, government was indeed more responsive and more democratic.

- To test this hypothesis, he compared twenty different regional Italian governments. All of these governments had similar institutions, but the regions had different traditions of civic engagement. In southern Italy, politics were traditionally patrimonial, whereas in northern Italy, politics were traditionally more open and citizens were more engaged. Putnam’s evidence supported his hypothesis: in the north, which had a stronger tradition of civic engaegment, government was indeed more responsive and more democratic.

A hypothesis is an assumption or suggested explanation about how two or more variables are related. It is a crucial step in the scientific method and, therefore, a vital aspect of all scientific research . There are no definitive guidelines for the production of new hypotheses. The history of science is filled with stories of scientists claiming a flash of inspiration, or a hunch, which then motivated them to look for evidence to support or refute the idea.

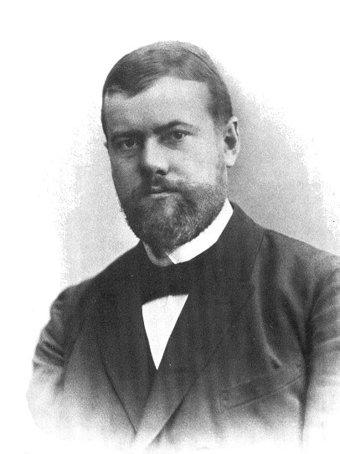

The Scientific Method is an Essential Tool in Research

This image lists the various stages of the scientific method.

While there is no single way to develop a hypothesis, a useful hypothesis will use deductive reasoning to make predictions that can be experimentally assessed. If results contradict the predictions, then the hypothesis under examination is incorrect or incomplete and must be revised or abandoned. If results confirm the predictions, then the hypothesis might be correct but is still subject to further testing.

Both quantitative and qualitative research involve formulating a hypothesis to address the research problem. A hypothesis will generally provide a causal explanation or propose some association between two variables. Variables are measurable phenomena whose values can change under different conditions. For example, if the hypothesis is a causal explanation, it will involve at least one dependent variable and one independent variable. In research, independent variables are the cause of the change. The dependent variable is the effect, or thing that is changed. In other words, the value of a dependent variable depends on the value of the independent variable. Of course, this assumes that there is an actual relationship between the two variables. If there is no relationship, then the value of the dependent variable does not depend on the value of the independent variable.

2.1.4: Determining the Research Design

The research design is the methodology and procedure a researcher follows to answer their sociological question.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast quantitive methods and qualitative methods

Key Points

- Research design defines the study type, research question, hypotheses, variables, and data collection methods. Some examples of research designs include descriptive, correlational, and experimental. Another distinction can be made between quantitative and qualitative methods.

- Sociological research can be conducted via quantitative or qualitative methods. Quantitative methods are useful when a researcher seeks to study large-scale patterns of behavior, while qualitative methods are more effective when dealing with interactions and relationships in detail.

- Quantitative methods include experiments, surveys, and statistical analysis, among others. Qualitative methods include participant observation, interviews, and content analysis.

- An interpretive framework is one that seeks to understand the social world from the perspective of participants.

- Although sociologists often specialize in one approach, many sociologists use a complementary combination of design types and research methods in their research. Even in the same study a researcher may employ multiple methods.

Key Terms

- scientific method

-

A method of discovering knowledge about the natural world based in making falsifiable predictions (hypotheses), testing them empirically, and developing peer-reviewed theories that best explain the known data.

- qualitative methods

-

Qualitative research is a method of inquiry employed in many different academic disciplines, traditionally in the social sciences, but also in market research and further contexts. Qualitative researchers aim to gather an in-depth understanding of human behavior and the reasons that govern such behavior. The qualitative method investigates the why and how of decision making, not just what, where, and when. Hence, smaller but focused samples are more often needed than large samples.

- quantitative methods

-

Quantitative research refers to the systematic empirical investigation of social phenomena via statistical, mathematical, or computational techniques.

Examples

- One of the best known examples of a quantitative research instrument is the United States Census, which is taken every 10 years. The Census form asks every person in the United States for some very basic information, such as age and race. These responses are collected and added together to calculate useful statistics, such as the national poverty rate. These statistics are then used to make important policy decisions.

- One of the most intensive forms of qualitative research is participant observation. In this method of research, the researcher actually becomes a member of the group she or he is studying. In 1981, sociologist Elijah Anderson published a book called A Place on the Corner, which was based on participant observation of an urban neighborhood. Anderson spent three years hanging out on the south side of Chicago, blending in with the neighborhood’s other regulars. He frequented a bar and liquor store, which he called “Jelly’s corner. ” His book is based on his interactions with and more formal interviews with the men who were regulars at Jelly’s corner. By essentially becoming one of them, Anderson was able to gain deep and detailed insight into their small community and how it worked.

A research design encompasses the methodology and procedure employed to conduct scientific research. Although procedures vary from one field of inquiry to another, identifiable features distinguish scientific inquiry from other methods of obtaining knowledge. In general, scientific researchers propose hypotheses as explanations of phenomena, and design research to test these hypotheses via predictions which can be derived from them.

The design of a study defines the study type, research question and hypotheses, independent and dependent variables, and data collection methods . There are many ways to classify research designs, but some examples include descriptive (case studies, surveys), correlational (observational study), semi-experimental (field experiment), experimental (with random assignment), review, and meta-analytic, among others. Another distinction can be made between quantitative methods and qualitative methods.

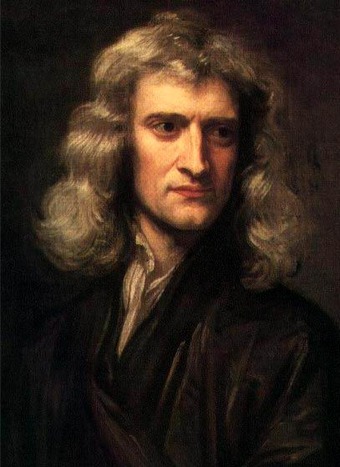

The Scientific Method is an Essential Tool in Research

This image lists the various stages of the scientific method.

Quantitative Methods

Quantitative methods are generally useful when a researcher seeks to study large-scale patterns of behavior, while qualitative methods are often more effective when dealing with interactions and relationships in detail . Quantitative methods of sociological research approach social phenomena from the perspective that they can be measured and quantified. For instance, socio-economic status (often referred to by sociologists as SES) can be divided into different groups such as working-class, middle-class, and wealthy, and can be measured using any of a number of variables, such as income and educational attainment.

Qualitative Methods

Qualitative methods are often used to develop a deeper understanding of a particular phenomenon. They also often deliberately give up on quantity, which is necessary for statistical analysis, in order to reach a greater depth in analysis of the phenomenon being studied. While quantitative methods involve experiments, surveys, secondary data analysis, and statistical analysis, qualitatively oriented sociologists tend to employ different methods of data collection and hypothesis testing, including participant observation, interviews, focus groups, content analysis, and historical comparison .

Qualitative sociological research is often associated with an interpretive framework, which is more descriptive or narrative in its findings. In contrast to the scientific method, which follows the hypothesis-testing model in order to find generalizable results, the interpretive framework seeks to understand social worlds from the point of view of participants.

Although sociologists often specialize in one approach, many sociologists use a complementary combination of design types and research methods in their research. Even in the same study a researcher may employ multiple methods.

2.1.5: Defining the Sample and Collecting Data

Defining the sample and collecting data are key parts of all empirical research, both qualitative and quantitative.

Learning Objective

Describe different types of research samples

Key Points

- It is important to determine the scope of a research project when developing the question. The choice of method often depends largely on what the researcher intends to investigate. Quantitative and qualitative research projects require different subject selection techniques.

- It is important to determine the scope of a research project when developing the question. While quantitative research requires at least 30 subjects to be considered statistically significant, qualitative research generally takes a more in-depth approach to fewer subjects.

- For both qualitative and quantitative research, sampling can be used. The stages of the sampling process are defining the population of interest, specifying the sampling frame, determining the sampling method and sample size, and sampling and data collecting.

- There are various types of samples, including probability and nonprobability samples. Examples of types of samples include simple random samples, stratified samples, cluster samples, and convenience samples.

- Good data collection involves following the defined sampling process, keeping the data in order, and noting comments and non-responses. Errors and biases can result in the data. Sampling errors and biases are induced by the sample design. Non-sampling errors can also affect results.

Key Terms

- bias

-

The difference between the expectation of the sample estimator and the true population value, which reduces the representativeness of the estimator by systematically distorting it.

- data collection

-

Data collection is a term used to describe a process of preparing and collecting data.

- sample

-

A subset of a population selected for measurement, observation or questioning, to provide statistical information about the population.

Social scientists employ a range of methods in order to analyze a vast breadth of social phenomena. Many empirical forms of sociological research follow the scientific method . Scientific inquiry is generally intended to be as objective as possible in order to reduce the biased interpretations of results. Sampling and data collection are a key component of this process.

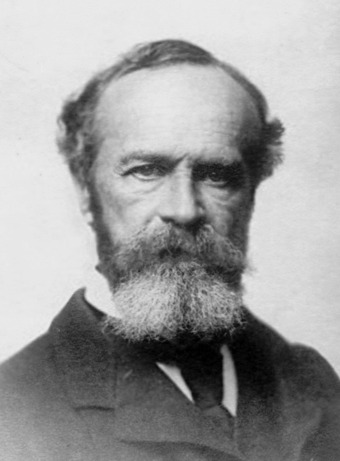

The Scientific Method is an Essential Tool in Research

This image lists the various stages of the scientific method.

It is important to determine the scope of a research project when developing the question. The choice of method often depends largely on what the researcher intends to investigate. For example, a researcher concerned with drawing a statistical generalization across an entire population may administer a survey questionnaire to a representative sample population. By contrast, a researcher who seeks full contextual understanding of the social actions of individuals may choose ethnographic participant observation or open-ended interviews. These two types of studies will yield different types of data. While quantitative research requires at least 30 subjects to be considered statistically significant, qualitative research generally takes a more in-depth approach to fewer subjects.

In both cases, it behooves the researcher to create a concrete list of goals for collecting data. For instance, a researcher might identify what characteristics should be represented in the subjects. Sampling can be used in both quantitative and qualitative research. In statistics and survey methodology, sampling is concerned with the selection of a subset of individuals from within a statistical population to estimate characteristics of the whole population . The stages of the sampling process are defining the population of interest, specifying the sampling frame, determining the sampling method and sample size, and sampling and data collecting.

Collecting Data

Natural scientists collect data by measuring and recording a sample of the thing they’re studying, such as plants or soil. Similarly, sociologists must collect a sample of social information, often by surveying or interviewing a group of people.

There are various types of samples. A probability sampling is one in which every unit in the population has a chance (greater than zero) of being selected in the sample, and this probability can be accurately determined. Nonprobability sampling is any sampling method where some elements of the population have no chance of selection or where the probability of selection can’t be accurately determined. Examples of types of samples include simple random samples, stratified samples, cluster samples, and convenience samples.

Good data collection involves following the defined sampling process, keeping the data in time order, noting comments and other contextual events, and recording non-responses. Errors and biases can result in the data. Sampling errors and biases, such as selection bias and random sampling error, are induced by the sample design. Non-sampling errors are other errors which can impact the results, caused by problems in data collection, processing, or sample design.

2.1.6: Analyzing Data and Drawing Conclusions

Data analysis in sociological research aims to identify meaningful sociological patterns.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast the analysis of quantitative vs. qualitative data

Key Points

- Analysis of data is a process of inspecting, cleaning, transforming, and modeling data with the goal of highlighting useful information, suggesting conclusions, and supporting decision making. Data analysis is a process, within which several phases can be distinguished.

- One way in which analysis can vary is by the nature of the data. Quantitative data is often analyzed using regressions. Regression analyses measure relationships between dependent and independent variables, taking the existence of unknown parameters into account.

- Qualitative data can be coded–that is, key concepts and variables are assigned a shorthand, and the data gathered are broken down into those concepts or variables. Coding allows sociologists to perform a more rigorous scientific analysis of the data.

- Sociological data analysis is designed to produce patterns. It is important to remember, however, that correlation does not imply causation; in other words, just because variables change at a proportional rate, it does not follow that one variable influences the other.

- Without a valid design, valid scientific conclusions cannot be drawn. Internal validity concerns the degree to which conclusions about causality can be made. External validity concerns the extent to which the results of a study are generalizable.

Key Terms

- correlation

-

A reciprocal, parallel or complementary relationship between two or more comparable objects.

- causation

-

The act of causing; also the act or agency by which an effect is produced.

- Regression analysis

-

In statistics, regression analysis includes many techniques for modeling and analyzing several variables, when the focus is on the relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables. More specifically, regression analysis helps one understand how the typical value of the dependent variable changes when any one of the independent variables is varied, while the other independent variables are held fixed.

Example

- When analyzing data and drawing conclusions, researchers look for patterns. Many hope to find causal patterns. But they must be cautious not to mistake correlation for causation. To better understand the difference between correlation and causation, consider this example. In a certain city, when more ice cream cones are sold, more shootings are reported. Surprised? Don’t be. This relationship is a correlation and it does not necessarily imply causation. The shootings aren’t necessarily caused by the ice cream cone sales. They just happen to occur at the same time. Why? In this case, it’s because of a third variable: temperature. Both shootings and ice cream cone sales tend to increase when the temperature goes up. This may be a causal relationship, not just correlation.

The Process of Data Analysis

Analysis of data is a process of inspecting, cleaning, transforming, and modeling data with the goal of highlighting useful information, suggesting conclusions, and supporting decision making. In statistical applications, some people divide data analysis into descriptive statistics, exploratory data analysis (EDA), and confirmatory data analysis (CDA). EDA focuses on discovering new features in the data and CDA focuses on confirming or falsifying existing hypotheses. Predictive analytics focuses on the application of statistical or structural models for predictive forecasting or classification. Text analytics applies statistical, linguistic, and structural techniques to extract and classify information from textual sources, a species of unstructured data.

Data analysis is a process, within which several phases can be distinguished. The initial data analysis phase is guided by examining, among other things, the quality of the data (for example, the presence of missing or extreme observations), the quality of measurements, and if the implementation of the study was in line with the research design. In the main analysis phase, either an exploratory or confirmatory approach can be adopted. Usually the approach is decided before data is collected. In an exploratory analysis, no clear hypothesis is stated before analyzing the data, and the data is searched for models that describe the data well. In a confirmatory analysis, clear hypotheses about the data are tested.

Regression Analysis

The type of data analysis employed can vary. One way in which analysis often varies is by the quantitative or qualitative nature of the data.

Quantitative data can be analyzed in a variety of ways, regression analysis being among the most popular . Regression analyses measure relationships between dependent and independent variables, taking the existence of unknown parameters into account. More specifically, regression analysis helps one understand how the typical value of the dependent variable changes when any one of the independent variables is varied, while the other independent variables are held fixed.

Linear Regression

This graph illustrates random data points and their linear regression.

A large body of techniques for carrying out regression analysis has been developed. In practice, the performance of regression analysis methods depends on the form of the data generating process and how it relates to the regression approach being used. Since the true form of the data-generating process is generally not known, regression analysis often depends to some extent on making assumptions about this process. These assumptions are sometimes testable if a large amount of data is available. Regression models for prediction are often useful even when the assumptions are moderately violated, although they may not perform optimally. However, in many applications, especially with small effects or questions of causality based on observational data, regression methods give misleading results.

Coding

Qualitative data can involve coding–that is, key concepts and variables are assigned a shorthand, and the data gathered is broken down into those concepts or variables . Coding allows sociologists to perform a more rigorous scientific analysis of the data. Coding is the process of categorizing qualitative data so that the data becomes quantifiable and thus measurable. Of course, before researchers can code raw data such as taped interviews, they need to have a clear research question. How data is coded depends entirely on what the researcher hopes to discover in the data; the same qualitative data can be coded in many different ways, calling attention to different aspects of the data.

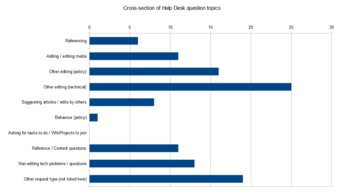

Coding Qualitative Data

Qualitative data can be coded, or sorted into categories. Coded data is quantifiable. In this bar chart, help requests have been coded and categorized so we can see which types of help requests are most common.

Sociological Data Analysis

Sociological data analysis is designed to produce patterns. It is important to remember, however, that correlation does not imply causation; in other words, just because variables change at a proportional rate, it does not follow that one variable influences the other .

Conclusions

In terms of the kinds of conclusions that can be drawn, a study and its results can be assessed in multiple ways. Without a valid design, valid scientific conclusions cannot be drawn. Internal validity is an inductive estimate of the degree to which conclusions about causal relationships can be made (e.g., cause and effect), based on the measures used, the research setting, and the whole research design. External validity concerns the extent to which the (internally valid) results of a study can be held to be true for other cases, such as to different people, places, or times. In other words, it is about whether findings can be validly generalized. Learning about and applying statistics (as well as knowing their limitations) can help you better understand sociological research and studies. Knowledge of statistics helps you makes sense of the numbers in terms of relationships, and it allows you to ask relevant questions about sociological phenomena.

2.1.7: Preparing the Research Report

Sociological research publications generally include a literature review, an overview of the methodology followed, the results and an analysis of those results, and conclusions.

Learning Objective

Describe the main components of a sociological research paper

Key Points

- Like any research paper, a sociological research report typically consists of a literature review, an overview of the methods used in data collection, and analysis, findings, and conclusions.

- A literature review is a creative way of organizing what has been written about a topic by scholars and researchers.

- The methods section is necessary to demonstrate how the study was conducted, including the population, sample frame, sample method, sample size, data collection method, and data processing and analysis.

- In the findings and conclusion sections, the researcher reviews all significant findings, notes and discusses all shortcomings, and suggests future research.

Key Terms

- literature review

-

A literature review is a body of text that aims to review the critical points of current knowledge including substantive findings as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to a particular topic.

- quantitative

-

Of a measurement based on some quantity or number rather than on some quality.

- methodology

-

A collection of methods, practices, procedures, and rules used by those who work in some field.

Like any research paper, sociological research is presented with a literature review, an overview of the methods used in data collection, and analysis, findings, and conclusions. Quantitative research papers are usually highly formulaic, with a clear introduction (including presentation of the problem and literature review); sampling and methods; results; discussion and conclusion. In striving to be as objective as possible in order to reduce biased interpretations of results, sociological esearch papers follow the scientific method . Research reports may be published as books or journal articles, given directly to a client, or presented at professional meetings .

The Scientific Method is an Essential Tool in Research

The scientific method is a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge.

A literature review is a creative way of organizing what has been written about a topic by scholars and researchers. You will find literature reviews at the beginning of many essays, research reports, or theses. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what you have learned through a careful reading of a set of articles related to your research question.

A strong literature review has the following properties:

- It is organized around issues, themes, factors, or variables that are related directly to your thesis or research question.

- It shows the path of prior research and how the current project is linked.

- It provides a good synthesis of what is, and is not, known.

- It indicates the theoretical framework with which you are working.

- It identifies areas of controversy and debate, or limitations in the literature sharing different perspectives.

- It places the formation of research questions in their historical context.

- It identifies the list of the authors that are engaged in similar work.

The methodssection is necessary to demonstrate how the study was conducted, and that the data is valid for study. Without assurance that the research is based on sound methods, readers cannot countenance any conclusions the researcher proposes. In the methodology section, be sure to include: the population, sample frame, sample method, sample size, data collection method, and data processing and analysis. This is also a section in which to clearly present information in table and graph form.

In the findings and conclusion sections, the researcher reviews all significant findings, notes and discusses all shortcomings, and suggests future research. The conclusion section is the only section where opinions can be expressed and persuasive writing is tolerated.

2.2: Research Models

2.2.1: Surveys

The goal of a survey is to collect data from a representative sample of a population to draw conclusions about that larger population.

Learning Objective

Assess the various types of surveys and sampling methods used in sociological research, appealing to the concepts of reliability and validity

Key Points

- The sample of people surveyed is chosen from the entire population of interest. The goal of a survey is to describe not the smaller sample but the larger population.

- To be able to generalize about a population from a smaller sample, that sample must be representative; proportionally the same in all relevant aspects (e.g., percent of women vs. men).

- Surveys can be distributed by mail, email, telephone, or in-person interview.

- Surveys can be used in cross-sectional, successive-independent-samples, and longitudinal study designs.

- Effective surveys are both reliable and valid. A reliable instrument produces consistent results every time it is administered; a valid instrument does in fact measure what it intends to measure.

Key Terms

- sample

-

A subset of a population selected for measurement, observation or questioning, to provide statistical information about the population.

- cross-sectional study

-

A research method that involves observation of a representative sample of a population at one specific point in time.

- successive-independent-samples design

-

A research method that involves observation of multiple random samples from a population over multiple time points.

- longitudinal design

-

A research method that involves observation of the same representative sample of a population over multiple time points, generally over a period of years or decades.

Selecting a Sample to Survey

The sample of people surveyed is chosen from the entire population of interest. The goal of a survey is to describe not the smaller sample but the larger population. This generalizing ability is dependent on the representativeness of the sample.

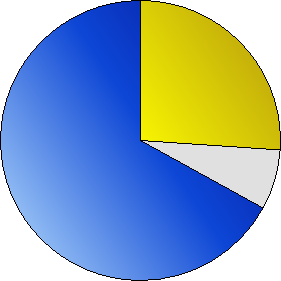

Nuclear Energy Support in the U.S.

This pie chart shows the results of a survey of people in the United States (February 2005, Bisconti Research Inc.). According to the poll, 67 percent of Americans favor nuclear energy (blue), while 26 percent oppose it (yellow).

There are frequent difficulties one encounters while choosing a representative sample. One common error that results is selection bias—when the procedures used to select a sample result in over- or under-representation of some significant aspect of the population. For instance, if the population of interest consists of 75% females, and 25% males, and the sample consists of 40% females and 60% males, females are under represented while males are overrepresented. In order to minimize selection biases, stratified random sampling is often used. This is when the population is divided into sub-populations called strata, and random samples are drawn from each of the strata, or elements are drawn for the sample on a proportional basis.

For instance, a Gallup Poll, if conducted as a truly representative nationwide random sampling, should be able to provide an accurate estimate of public opinion whether it contacts 2,000 or 10,000 people.

Modes of Administering a Survey

There are several ways of administering a survey. The choice between administration modes is influenced by several factors, including

- costs,

- coverage of the target population,

- flexibility of asking questions,

- respondents’ willingness to participate and

- response accuracy

Different methods create mode effects that change how respondents answer, and different methods have different advantages. The most common modes of administration can be summarized as:

- Telephone

- Mail (post)

- Online surveys

- Personal in-home surveys

- Personal mall or street intercept survey

- Hybrids of the above

Participants willing to take the time to respond will convey personal information about religious beliefs, political views, and morals. Some topics that reflect internal thought are impossible to observe directly and are difficult to discuss honestly in a public forum. People are more likely to share honest answers if they can respond to questions anonymously.

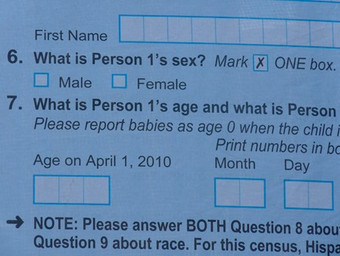

Questionnaire

Questionnaires are a common research method; the U.S. Census is a well-known example.

Types of Studies

Cross-Sectional Design

In a cross-sectional study, a sample (or samples) is drawn from the relevant population and studied once. A cross-sectional study describes characteristics of that population at one time, but cannot give any insight as to causes of population characteristics.

Successive-Independent-Samples Design

A successive-independent-samples design draws multiple random samples from a population at one or more times. This design can study changes within a population, but not changes within individuals because the same individuals are not surveyed more than once. Such studies cannot, therefore, identify the causes of change over time necessarily.

For successive independent samples designs to be effective, the samples must be drawn from the same population, and must be equally representative of it. If the samples are not comparable, the changes between samples may be due to demographic characteristics rather than time. In addition, the questions must be asked in the same way so that responses can be compared directly.

Longitudinal Design

A study following a longitudinal design takes measure of the same random sample at multiple time points. Unlike with a successive independent samples design, this design measures the differences in individual participants’ responses over time. This means that a researcher can potentially assess the reasons for response changes by assessing the differences in respondents’ experiences. However, longitudinal studies are both expensive and difficult to do. It’s harder to find a sample that will commit to a months- or years-long study than a 15-minute interview, and participants frequently leave the study before the final assessment. This attrition of participants is not random, so samples can become less representative with successive assessments.

Reliability and Validity

Reliable measures of self-report are defined by their consistency. Thus, a reliable self-report measure produces consistent results every time it is executed.

A test’s reliability can be measured a few ways. First, one can calculate a test-retest reliability. A test-retest reliability entails conducting the same questionnaire to a large sample at two different times. For the questionnaire to be considered reliable, people in the sample do not have to score identically on each test, but rather their position in the score distribution should be similar for both the test and the retest.

Self-report measures will generally be more reliable when they have many items measuring a construct. Furthermore, measurements will be more reliable when the factor being measured has greater variability among the individuals in the sample that are being tested. Finally, there will be greater reliability when instructions for the completion of the questionnaire are clear and when there are limited distractions in the testing environment.

Contrastingly, a questionnaire is valid if what it measures is what it had originally planned to measure. Construct validity of a measure is the degree to which it measures the theoretical construct that it was originally supposed to measure.

2.2.2: Fieldwork and Observation

Ethnography is a research process that uses fieldwork and observation to learn about a particular community or culture.

Learning Objective

Explain the goals and methods of ethnography

Key Points

- Ethnographic work requires intensive and often immersive long-term participation in the community that is the subject of research, typically involving physical relocation (hence the term fieldwork).

- In participant observation, the researcher immerses himself in a cultural environment, usually over an extended period of time, in order to gain a close and intimate familiarity with a given group of individuals and their practices.

- Such research involves a range of well-defined, though variable methods: interviews, direct observation, participation in the life of the group, collective discussions, analyses of personal documents produced within the group, self-analysis, and life-histories, among others.

- The advantage of ethnography as a technique is that it maximizes the researcher’s understanding of the social and cultural context in which human behavior occurs.

- The advantage of ethnography as a technique is that it maximizes the researcher’s understanding of the social and cultural context in which human behavior occurs. The ethnographer seeks out and develops relationships with cultural insiders, or informants, who are willing to explain aspects of their community from a native viewpoint. A particularly knowledgeable informant who can connect the ethnographer with other such informants is known as a key informant.

Key Terms

- qualitative

-

Of descriptions or distinctions based on some quality rather than on some quantity.

- ethnography

-

The branch of anthropology that scientifically describes specific human cultures and societies.

Example

- Key informants are usually well-connected people who can help an ethnographer gain access to and better understand a community. For example, Sudhir Venkatesh’s key informant, JT, was the leader of the street gang Venkatesh was studying. As the leader of the gang, JT had a privileged vantage point to see, understand, and explain how the gang worked, as well as to introduce Venkatesh to other members.

Fieldwork and Observation

Ethnography is a qualitative research strategy, involving a combination of fieldwork and observation, which seeks to understand cultural phenomena that reflect the knowledge and system of meanings guiding the life of a cultural group. It was pioneered in the field of socio-cultural anthropology, but has also become a popular method in various other fields of social sciences, particularly in sociology.

Ethnographic work requires intensive and often immersive long-term participation in the community that is the subject of research, typically involving physical relocation (hence the term fieldwork). Although it often involves studying ethnic or cultural minority groups, this is not always the case. Ideally, the researcher should strive to have very little effect on the subjects of the study, being as invisible and enmeshed in the community as possible.

Participant Observation

One of the most common methods for collecting data in an ethnographic study is first-hand engagement, known as participant observation . In participant observation, the researcher immerses himself in a cultural environment, usually over an extended period of time, in order to gain a close and intimate familiarity with a given group of individuals (such as a religious, occupational, or sub-cultural group, or a particular community) and their practices.

Fieldwork and Observation

One of the most common methods for collecting data in an ethnographic study is first-hand engagement, known as participant observation.

Methods

Such research involves a range of well-defined, though variable methods: interviews, direct observation, participation in the life of the group, collective discussions, analyses of personal documents produced within the group, self-analysis, and life-histories, among others.

Interviews can be either informal or formal and can range from brief conversations to extended sessions. One way of transcribing interview data is the genealogical method. This is a set of procedures by which ethnographers discover and record connections of kinship, descent, and marriage using diagrams and symbols. Questionnaires can also be used to aid the discovery of local beliefs and perceptions and, in the case of longitudinal research where there is continuous long-term study of an area or site, they can act as valid instruments for measuring changes in the individuals or groups studied.

Advantages

The advantage of ethnography as a technique is that it maximizes the researcher’s understanding of the social and cultural context in which human behavior occurs. The ethnographer seeks out and develops relationships with cultural insiders, or informants, who are willing to explain aspects of their community from a native viewpoint. The process of seeking out new contacts through their personal relationships with current informants is often effective in revealing common cultural common denominators connected to the topic being studied.

2.2.3: Experiments

Experiments are tests designed to prove or disprove a hypothesis by controlling for pertinent variables.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast how hypotheses are being tested in sociology and in the hard sciences

Key Points

- Experiments are controlled tests designed to prove or disprove a hypothesis.

- A hypothesis is a prediction or an idea that has not yet been tested.

- Researchers must attempt to identify everything that might influence the results of an experiment, and do their best to neutralize the effects of everything except the topic of study.

- Since social scientists do not seek to isolate variables in the same way that the hard sciences do, sociologists create the equivalent of an experimental control via statistical techniques that are applied after data is gathered.

- A control is when two identical experiments are conducted and the factor being tested is varied in only one of these experiments.

Key Terms

- experiment

-

A test under controlled conditions made to either demonstrate a known truth, examine the validity of a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy of something previously untried.

- control

-

A separate group or subject in an experiment against which the results are compared where the primary variable is low or nonexistent.

- hypothesis

-

Used loosely, a tentative conjecture explaining an observation, phenomenon, or scientific problem that can be tested by further observation, investigation, or experimentation.

Example

- To conduct an experiment, a scientist must be able to control experimental conditions so that only the variable being studied changes. For example, a scientist might have two identical bacterial cultures. One is the control and it remains unchanged. The other is the experimental culture and it will be subjected to a treatment, such as an antibiotic. The scientist can then compare any differences that develop and safely assume those differences are due to the effects of the antibiotic. But social life is complicated and it would be difficult for a social scientist to find two identical groups of people in order to have both an experimental and a control group. Imagine, for instance, that a sociologist wants to know whether small class size improves academic achievement. For a true experiment, she would need to find identical students and identical teachers, then put some in large classes and some in small classes. But finding identical students and teachers would be impossible! Instead, the sociologist can statistically control for differences by including variables such as students’ socioeconomic status, family background, and teachers’ evaluation scores in a regression. This technique does not make the students or teachers identical, but it allows the research to calculate how much of the difference in students’ achievement is due to background factors like socioeconomic status and how much is actually due to differences in class size.

Scientists form a hypothesis, which is a prediction or an idea that has not yet been tested. In order to prove or disprove the hypothesis, scientists must perform experiments. The experiment is a controlled test designed specifically to prove or disprove the hypothesis . Before undertaking the experiment, researchers must attempt to identify everything that might influence the results of an experiment and do their best to neutralize the effects of everything except the topic of study. This is done through the introduction of an experimental control: two virtually identical experiments are run, in only one of which the factor being tested is varied. This serves to further isolate any causal phenomena.

An Experiment

An experiment is a controlled test designed specifically to prove or disprove a hypothesis.

Of course, an experiment is not an absolute requirement. In observation based fields of science, actual experiments must be designed differently than for the classical laboratory based sciences. Due to ethical concerns and the sheer cost of manipulating large segments of society, sociologists often turn to other methods for testing hypotheses.

Since sociologists do not seek to isolate variables in the same way that hard sciences do, this kind of control is often done via statistical techniques, such as regressions, applied after data is gathered. Direct experimentation is thus fairly rare in sociology.

Scientists must assume an attitude of openness and accountability on the part of those conducting an experiment. It is essential to keep detailed records in order to facilitate reporting on the experimental results and provide evidence of the effectiveness and integrity of the procedure.

2.2.4: Documents

Documentary research involves examining texts and documents as evidence of human behavior.

Learning Objective

Describe different kinds of documents used in sociological research

Key Points

- This kind of sociological research is generally considered a part of media studies.

- Unobtrusive research involves ways of studying human behavior without affecting it in the process.

- Documents can either be primary sources, which are original materials that are not created after the fact with the benefit of hindsight, or secondary sources that cite, comment, or build upon primary sources.

- Typically, sociological research involving documents falls under the cross-disciplinary purview of media studies, which encompasses all research dealing with television, books, magazines, pamphlets, or any other human-recorded data. The specific media being studied are often referred to as texts.

- Sociological research involving documents, or, more specifically, media studies, is one of the less interactive research options available to sociologists. It can provide a significant insight into the norms, values, and beliefs of people belonging to a particular historical and cultural context.

- Content analysis is the study of recorded human communications.

Key Terms

- media studies

-

Academic discipline that deals with the content, history, meaning, and effects of various media, and in particular mass media.

- content analysis

-

Content analysis or textual analysis is a methodology in the social sciences for studying the content of communication.

- documentary research

-

Documentary research involves the use of texts and documents as source materials. Source materials include: government publications, newspapers, certificates, census publications, novels, film and video, paintings, personal photographs, diaries and innumerable other written, visual, and pictorial sources in paper, electronic, or other “hard copy” form.

Documentary Research

It is possible to do sociological research without directly involving humans at all. One such method is documentary research. In documentary research, all information is collected from texts and documents. The texts and documents can be either written, pictorial, or visual in form.

The material used can be categorized as primary sources, which are original materials that are not created after the fact with the benefit of hindsight, and secondary sources that cite, comment, or build upon primary sources.

Media Studies and Content Analysis

Typically, sociological research on documents falls under the cross-disciplinary purview of media studies, which encompasses all research dealing with television, books, magazines, pamphlets, or any other human-recorded data. Regardless of the specific media being studied, they are referred to as texts.

Media studies may draw on traditions from both the social sciences and the humanities, but mostly from its core disciplines of mass communication, communication, communication sciences, and communication studies.

Researchers may also develop and employ theories and methods from disciplines including cultural studies, rhetoric, philosophy, literary theory, psychology, political economy, economics, sociology, anthropology, social theory, art history and criticism, film theory, feminist theory, information theory, and political science .

Government Documentary Research

Sociologists may use government documents to research the ways in which policies are made.

Content analysis refers to the study of recorded human communications, such as paintings, written texts, and photos. It falls under the category of unobtrusive research, which can be defined as ways for studying human behavior without affecting it in the process. While sociological research involving documents is one of the less interactive research options available to sociologists, it can reveal a great deal about the norms, values, and beliefs of people belonging to a particular temporal and cultural context.

2.2.5: Use of Existing Sources

Studying existing sources collected by other researchers is an essential part of research in the social sciences.

Learning Objective

Explain how the use of existing sources can benefit researchers

Key Points

- Archival research is the study of existing sources. Without archival research, any research project is necessarily incomplete.

- The study of sources collected by someone other than the researcher is known as archival research or secondary data research.

- The importance of archival or secondary data research is two-fold. By studying texts related to their topics, researchers gain a strong foundation on which to base their work. Secondly, this kind of study is necessary in the development of their central research question.

Key Terms

- primary data

-

Data that has been compiled for a specific purpose, and has not been collated or merged with others.

- Archival research

-

An archive is a way of sorting and organizing older documents, whether it be digitally (photographs online, e-mails, etc.) or manually (putting it in folders, photo albums, etc.). Archiving is one part of the curating process which is typically carried out by a curator.

- secondary data

-

Secondary data is data collected by someone other than the user. Common sources of secondary data for social science include censuses, organizational records, and data collected through qualitative methodologies or qualitative research.

Example

- Harvard sociologist Theda Skocpol is well known for her work in comparative historical sociology, a sub-field that tends to emphasize the use of existing sources because of its often wide geographical and historical scope. For example, in her 1979 book States and Social Revolutions, Skocpol compared the history of revolution in three countries: France, Russia, and China. Direct research methods such as interviews would have been impossible, since many of the events she analyzed, such as the French Revolution, took place hundreds of years in the past. But even gathering primary historical documents for each of the three countries would have been a daunting task. Instead, Skocpol relied heavily on secondary accounts of the histories of each country, which allowed her to analyze and compare hundreds of years of history from countries thousands of miles apart.

Using Existing Sources

The study of sources collected by someone other than the researcher, also known as archival research or secondary data research, is an essential part of sociology . In archival research or secondary research, the focus is not on collecting new data but on studying existing texts.

Existing Sources

While some sociologists spend time in the field conducting surveys or observing participants, others spend most of their research time in libraries, using existing sources for their research.

By studying texts related to their topics, researchers gain a strong foundation on which to base their work. Furthermore, this kind of study is necessary for the development of their central research question. Without a thorough understanding of the research that has already been done, it is impossible to know what a meaningful and relevant research question is, much less how to position and frame research within the context of the field as a whole.

Types of Existing Sources

Common sources of secondary data for social science include censuses, organizational records, field notes, semi-structured and structured interviews, and other forms of data collected through quantitative methods or qualitative research. These methods are considered non-reactive, because the people do not know they are involved in a study. Common sources differ from primary data. Primary data, by contrast, are collected by the investigator conducting the research.

Researchers use secondary analysis for several reasons. The primary reason is that secondary data analysis saves time that would otherwise be spent collecting data. In the case of quantitative data, secondary analysis provides larger and higher-quality databases that would be unfeasible for any individual researcher to collect on his own. In addition, analysts of social and economic change consider secondary data essential, since it is impossible to conduct a new survey that can adequately capture past change and developments.

2.3: Ethics in Sociological Research

2.3.1: Confidentiality

Sociologists should take all necessary steps to protect the privacy and confidentiality of their subjects.

Learning Objective

Give examples of how the anonymity of a research subject can be protected

Key Points

- When a survey is used, the data should be coded to protect the anonymity of subject.

- For field research, anonymity can be maintained by using aliases (fake names) on the observation reports.

- The types of information that should be kept confidential can range from a person’s name or income, to more significant details (depending on the participant’s social and political contexts), such as religious or political affiliation.

- The kinds of information that should be kept confidential can range from relatively innocuous facts, such as a person’s name, to more sensitive information, such as a person’s religious affiliation.

- Steps to ensure that the confidentiality of research participants is never breached include using pseudonyms for research subjects and keeping all notes in a secure location.

Key Terms

- confidentiality

-

Confidentiality is an ethical principle of discretion associated with the professions, such as medicine, law, and psychotherapy.

- research

-

Diligent inquiry or examination to seek or revise facts, principles, theories, and applications.

- pseudonym

-

A fictitious name, often used by writers and movie stars.

In any sociological research conducted on human subjects, the sociologists should take all the steps necessary to protect the privacy and confidentiality of their subjects. For example, when a survey is used, the data should be coded to protect the anonymity of the subjects.

In addition, there should be no way for any answers to be connected with the respondent who gave them . These rules apply to field research as well. For field research, anonymity can be maintained by using aliases (fake names) on the observation reports.

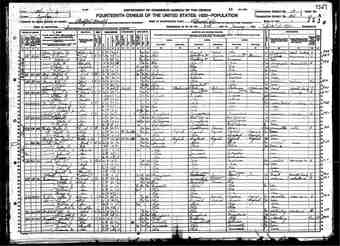

Cuyahoga County U.S. Census Form from 1920

Following ethical guidelines, researchers keep individual details confidential for decades. This form, from 1920, has been released because the information contained is too old to have any likely consequences for people who are still alive.

The types of information that should be kept confidential can range from something as relatively mundane and innocuous as a person’s name (pseudonyms are often employed in both interview transcripts and published research) or income, to more significant details (depending on the participant’s social and political contexts), such as religious or political affiliation.

Even seemingly trivial information should be kept safe, because it is impossible to predict what the repercussions would be in the event that this information becomes public. Unless subjects specifically and explicitly give their consent to be associated with the published information, no real names or identifying information of any kind should be used. Any research notes that might identify subjects should be stored securely. It is the obligation of the researcher to protect the private information of the research subjects, particularly when studying sensitive and controversial topics like deviance, the results of which may harm the participants if they were to be personally identified. By ensuring the safety of sensitive information, researchers ensure the safety of their subjects.

2.3.2: Protecting Research Subjects

There are many guidelines in place to protect human subjects in sociological research.

Learning Objective

Identify the core tenet of research ethics, the importance of research ethics, and examples of ethical practice

Key Points

- Sociologists have a responsibility to protect their subjects by following ethical guidelines. Organizations like the American Sociological Association maintain, oversee, and enforce a code of ethics for sociologists to follow.

- In the context of sociological research, a code of ethics refers to formal guidelines for conducting sociological research, consisting of principles and ethical standards.

- The core tenet of research ethics is that the subjects not be harmed; principles such as confidentiality, anonymity, informed consent, and honesty follow from this premise.

- Institutional review boards are committees designated to approve, monitor, and review research involving people. They are intended to assess such factors as conflicts of interest and potential emotional distress caused to subjects.

- Institutional Review Boards are committees designated to approve, monitor, and review research involving people. They are intended to assess such factors as conflicts of interest–for instance, a funding source that has a vested interest in the outcome of a research project–and potential emotional distress caused to subjects.

Key Terms

- institutional review board

-

An institutional review board (IRB), also known as an independent ethics committee or ethical review board, is a committee that has been formally designated to approve, monitor, and review biomedical and behavioral research involving humans.

- confidentiality

-

Confidentiality is an ethical principle of discretion associated with the professions, such as medicine, law, and psychotherapy.

- informed consent

-

Informed consent is a phrase often used in law to indicate that the consent a person gives meets certain minimum standards. In order to give informed consent, the individual concerned must have adequate reasoning faculties and be in possession of all relevant facts at the time consent is given.

Examples

- Today’s ethical standards were developed in response to previous studies that had deleterious results for participants. One of the most infamous was the Stanford prison experiment. The Stanford prison experiment, conducted by researchers at Stanford in 1971, was funded by the military and meant to shed light on the sources of conflict between military guards and prisoners. For the experiment, researchers recruited 24 undergraduate students and randomly assigned each of them to be either a prisoner or a guard in a mock prison in the basement of the Stanford psychology department building. The participants adapted to their roles well beyond expectations, as the guards enforced authoritarian measures and ultimately subjected some of the prisoners to psychological torture. Many of the prisoners passively accepted psychological abuse and, at the request of the guards, readily harassed other prisoners who attempted to prevent it. Two of the prisoners quit the experiment early and the entire experiment was abruptly stopped after only six days. The experiment was criticized as being unethical and unscientific. Subsequently-adopted ethical standards would make it a breach of ethics to conduct such a study.

- The Stanford prison experiment, conducted by researchers at Stanford in 1971, was funded by the military and meant to shed light on the sources of conflict between military guards and prisoners. For the experiment, researchers recruited 24 undergraduate students and randomly assigned each of them to be either a prisoner or a guard in a mock prison in the basement of the Stanford psychology department building. The participants adapted to their roles well beyond expectations, as the guards enforced authoritarian measures and ultimately subjected some of the prisoners to psychological torture. Many of the prisoners passively accepted psychological abuse and, at the request of the guards, readily harassed other prisoners who attempted to prevent it. Two of the prisoners quit the experiment early and the entire experiment was abruptly stopped after only six days. The experiment was criticized as being unethical and unscientific. Subsequently-adopted ethical standards would make it a breach of ethics to conduct such a study.

Ethical considerations are of particular importance to sociologists because sociologists study people. Thus, sociologists must adhere to a rigorous code of ethics. In the context of sociological research, a code of ethics refers to formal guidelines for conducting research, consisting of principles and ethical standards concerning the treatment of human individuals.

The most important ethical consideration in sociological research is that participants in a sociological investigation are not harmed in any way. Exactly what this entails can vary from study to study, but there are several universally recognized considerations. For instance, research on children and youth always requires parental consent . All sociological research requiresinformed consent, and participants are never coerced into participation. Informed consent in general involves ensuring that prior to agreeing to participate, research subjects are aware of details of the study including the risks and benefits of participation and in what ways the data collected will be used and kept secure. Participants are also told that they may stop their participation in the study at any time.

Ethical Guidelines for Research Involving Children

Sociologists must follow strict ethical guidelines, especially when working with children or other vulnerable populations.

Institutional review boards (IRBs) are committees that are appointed to approve, monitor, and review research involving human subjects in order to make sure that the well-being of research participants is never compromised. They are thus intended to assess such factors as conflicts of interest–for instance, a funding source that has a vested interest in the outcome of a research project–and potential emotional distress caused to subjects. While often primarily oriented toward biomedical research, approval from IRBs is now required for all studies dealing with humans.

2.3.3: Misleading Research Subjects

If a researcher deceives or conceals the purpose or procedure of a study, they are misleading their research subjects.

Learning Objective

Identify two problems with intentionally deceiving research subjects

Key Points

- Although deception introduces ethical concerns because it threatens the validity of the subjects’ informed consent, there are certain cases in which researchers are allowed to deceive their subjects.

- Some studies involve intentionally deceiving subjects about the nature of the research, especially in cases in which full disclosure to the research subject could either skew the results of the study or cause some sort of harm to the researcher.

- In most instances, researchers are required to debrief (reveal the deception and explain the true purpose of the study to) subjects after the data is gathered.

- Some possible ways to address concerns are collecting pre-consent from participants and minimizing deception.

Key Terms

- subject

-

A human research subject is a living individual about whom a research investigator (whether a professional or a student) obtains data.

- debrief

-

To question someone, or a group of people, after the implementation of a project in order to learn from mistakes.

Example

- Asch’s study of conformity is an example of research that required deception. Asch put a subject in a room with other participants who appeared to be normal subjects but who were actually part of the experiment. All participants were shown three lines of different length and asked to identify which was the same length as a fourth line. All experimenters would answer correctly until the last question, at which point they would choose the wrong answer. In most cases, the subject would conform and agree with the others, choosing a line that was clearly incorrect. If subjects knew beforehand that the study was investigating conformity, they would have reacted differently. In this case, deception was justified.

Some sociology studies involve intentionally deceiving subjects about the nature of the research. For instance, a researcher dealing with an organized crime syndicate might be concerned that if his subjects were aware of the researcher’s academic interests, his physical safety might be at risk . A more common case is a study in which researchers are concerned that if the subjects are aware of what is being measured, such as their reaction to a series of violent images, the results will be altered or tempered by that knowledge. In the latter case, researchers are required to debrief (reveal the deception and explain the true purpose of the study to) subjects after the data is gathered.

Dangerous Elements

Researchers working in dangerous environments may deceive participants in order to protect their own safety.

The ethical problems with conducting a trial involving an element of deception are legion. Valid consent means a participant is aware of all relevant context surrounding the research they are participating in, including both risks and benefits. Failure to ensure informed consent is likely to result in the harm of potential participants and others who may be affected indirectly. This harm could occur either in terms of the distress that subsequent knowledge of deception may cause participants and others, or in terms of the significant risks to which deception may expose participants and others. For example, a participant in a medical trial could misuse a drug substance, believing it to be a placebo.

Two approaches have been suggested to minimize such difficulties: pre-consent (including authorized deception and generic pre-consent) and minimized deception. Pre-consent involves informing potential participants that a given research study involves an element of deception without revealing its exact nature. This approach respects the autonomy of individuals because subjects consent to the deception. Minimizing deception involves taking steps such as introducing words like “probably” so that statements are formally accurate even if they may be misleading.

2.3.4: Research Funding

Research funding comes from grants from private groups or governments, and researchers must be careful to avoid conflicts of interest.

Learning Objective

Examine the process of receiving research funding, including avoiding conflicts of interest and the sources of research funding

Key Points

- Most research funding comes from two major sources: corporations (through research and development departments) and government (primarily carried out through universities and specialized government agencies).

- If the funding source for a research project has an interest in the outcome of the project, this represents a conflict of interest and a potential ethical breach.

- A conflict of interest can occur if a sociologist is granted funding to conduct research on a topic, which the source of funding is invested in or related to in some way.

Key Terms

- research

-

Diligent inquiry or examination to seek or revise facts, principles, theories, and applications.

- conflict of interest

-

A situation in which someone in a position of trust has competing professional or personal interests.

Example