9.1: Deploying Supporting Materials

9.1.1: Types of Supporting Materials

There are many types of supporting materials, some of which are better suited for logical appeals and some for emotional appeals.

Learning Objective

Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of using different types of supporting materials

Key Points

- Scientific evidence includes all factual information. It is necessary and particularly useful for logical appeals.

- Testimonials, personal experience, intuition, and anecdotal evidence are all great for emotional appeals.

- Non-scientific supporting materials may be useful, but are not necessarily reflective of broader truths.

Key Term

- anecdote

-

An account or story which supports an argument, but which is not supported by scientific or statistical analysis.

There are a number of types of supporting materials, each of which has its own advantages and disadvantages. Not every type of supporting material is useful or effective in every situation, but each has its own niche.

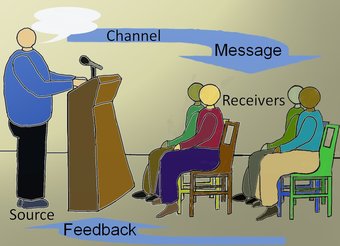

Scientific Evidence

Scientific evidence is evidence which serves to either support or counter a scientific theory or hypothesis. Such evidence is expected to be empirical and in accordance with scientific method. Standards for scientific evidence vary according to the field of inquiry, but the strength of scientific evidence is generally based on the results of statistical analysis and the strength of scientific controls.More broadly, scientific evidence can be any statistic or fact that has been proven to be true through rigorous scientific methods. Facts and figures are necessary for logical appeals .

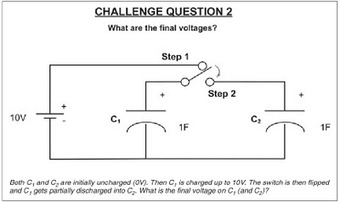

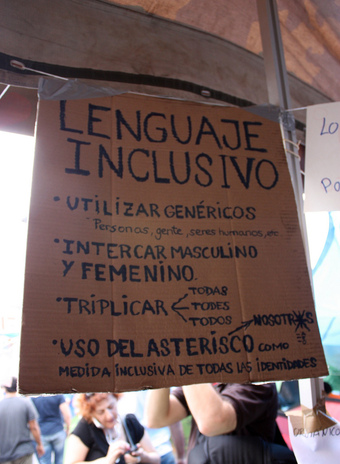

Scientific Evidence

Statistics are a type of scientific evidence that can bolster arguments.

Personal Experience

Personal experience is the retelling of something that actually happened to the speaker. Personal experience is useful for emotional appeals, but is not always good for more scientific arguments.

Anecdotal Evidence

Anecdotal evidence is evidence from anecdotes (stories). Because of the small sample, there is a larger chance that it may be unreliable due to cherry-picked or otherwise non-representative samples of typical cases. Anecdotal evidence is considered dubious support for a claim; it is accepted only in lieu of more solid evidence. However, it is particularly useful for making emotional appeals.

Intuition

Intuition is the ability to acquire knowledge without inference or the use of reason. Intuition provides us with beliefs that we cannot justify in every case. For this reason, intuition is not a particularly strong supporting material.

Testimonial

A testimonial is when someone speaks on behalf of another idea, product, or person. For example, weight loss commercials often utilize testimonials. The power lies in how convincing the person giving the testimonial is.

9.1.2: Using Supporting Materials

Supporting materials bolster arguments and can make them more persuasive to audience members.

Learning Objective

Identify reasons to use supporting materials and which types of materials are appropriate in a given situation

Key Points

- Scientific evidence is used to prove that a set of facts exist in the world.

- Non-scientific evidence is often used to create emotional connections with the audience, which can make them more receptive to the argument.

- Misused supporting materials can ruin your perceived reliability as a speaker and cause the audience to stop taking your argument seriously.

Key Term

- scientific evidence

-

Empirical, true facts or figures.

Supporting materials are necessary to turn an opinion into a persuasive argument. Being able to say something and have others immediately accept it as truth is a privilege afforded few speakers in few settings. In the vast majority of cases, audiences will not just want to hear the view you are asking them to accept, but also why they should accept it.

Supporting materials come in many different forms, from scientific evidence to personal experiences. Each is useful in different situations, but all are used to cause the audience to stop rejecting your idea as foreign and instead internalize it as truth.

Not all supporting evidence, however, is created equally. For example, scientific evidence is absolutely necessary in settings such as an exam. Appealing to the emotions of the professor is unlikely to yield a positive result, while articulating and analyzing the correct facts is. Scientific evidence is used to prove that a set of facts or conditions is present in the world.

Scientific Evidence

In most subjects, exam questions test the individual’s grasp of empirical evidence (scientific evidence).

In other instances, more experiential evidence will help you connect to the audience on a personal level. Personal experiences and anecdotes are great for establishing an emotional connection with the audience. Being able to connect emotionally helps to mitigate some of the boredom that often accompanies appeals that are just facts.

Using non-scientific evidence comes with some dangers, however. Non-scientific information is not often generalizable. That is, just because there is a story (or series of stories) does not mean that they necessarily represent the broader truth. Some audiences are skeptical of non-scientific supporting materials for this very reason. Using an anecdote of a boat sinking, for example, is unlikely to persuade most audiences that all boats sink. Attempting to use this type of evidence can actually weaken the appeal by decreasing your perceived reliability as a source.

9.1.3: Using Supporting Materials Effectively

Supporting materials are effective only if they help persuade the audience.

Learning Objective

Name elements to be considered when deciding what type of supporting materials to deploy

Key Points

- Regardless of the type of supporting material used, they are effective only if they fulfill the speaker’s burden of proof.

- Supporting materials must exist in order to be used; not all types exist for all arguments.

- The supporting evidence used depends on the idea being supported. Some ideas are more effectively supported by certain types of materials.

- Not all types of supporting materials are effective for every appeal. Speakers should select the materials that make their specific appeal most effective.

- The type of supporting material used also depends on the audience. If the audience cannot comprehend the material, it is not effective.

Key Term

- comprehensible

-

Able to be comprehended; understandable.

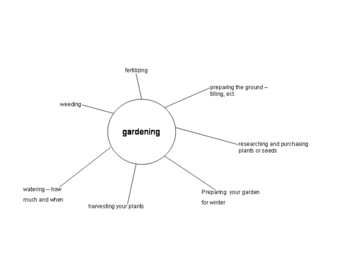

Using Supporting Materials Effectively

Supporting materials are the difference between an opinion and a convincing argument. Supporting materials are effective only if they help to persuade the audience. The type of supporting materials that should be deployed depend on the following:

- Available supporting material: not all types of supporting materials exist for all arguments. If there is no evidence, it obviously cannot be used.

- The idea being supported: if you are trying to explain that your favorite ice cream is chocolate, then scientific evidence about the molecular composition of chocolate ice cream is not as effective as personal accounts .

- The type of appeal: emotional and logical appeals tend to be supported by different types of materials. All types of supporting material can be used for emotional appeals, but providing data may not be as effective as providing anecdotes for connecting with the audience. For logical appeals, all types can again be used, though the most effective support is scientific evidence, because it is empirical and true.

- The audience: different audiences respond differently to different types of supporting evidence. It is the speaker’s job to determine what supporting materials will be most comprehensible and effective.

Gathering Evidence

An individual must have enough supporting material (evidence) in order to write a convincing speech.

Regardless of the type of supporting material used, they are effective only if they fulfill the speaker’s burden of proof. If the supporting materials are not delivered in a way that advances that goal, they are not deployed effectively.

For example, if you are speaking in front of a large crowd, and use a chart printed out on a sheet of paper, it doesn’t really matter what the chart says. If the audience cannot see the chart, then it will not be understood or effective. The same goes for other types of supporting materials; they are only effective if they can convince the audience.

9.2: Using Examples

9.2.1: Types of Examples: Brief, Extended, and Hypothetical

Brief, extended, and hypothetical examples can be used to help an audience better understand and relate to key points of a presentation.

Learning Objective

List the three types of examples

Key Points

- Examples include specific situations, problems or stories intended to help communicate a more general idea.

- Brief examples are used to further illustrate a point that may not be immediately obvious to all audience members but is not so complex that is requires a more lengthy example.

- Extended examples are used when a presenter is discussing a more complicated topic that they think their audience may be unfamiliar with.

- A hypothetical example is a fictional example that can be used when a speaker is explaining a complicated topic that makes the most sense when it is put into more realistic or relatable terms.

Key Term

- Hypothetical

-

A fictional situation or proposition used to explain a complicated subject.

There are many types of examples that a presenter can use to help an audience better understand a topic and the key points of a presentation. These include specific situations, problems, or stories intended to help communicate a more general idea. There are three main types of examples: brief, extended, and hypothetical.

Brief Examples

Brief examples are used to further illustrate a point that may not be immediately obvious to all audience members but is not so complex that is requires a more lengthy example. Brief examples can be used by the presenter as an aside or on its own. A presenter may use a brief example in a presentation on politics in explaining the Electoral College. Since many people are familiar with how the Electoral College works, the presenter may just mention that the Electoral College is based on population and a brief example of how it is used to determine an election. In this situation it would not be necessary for a presented to go into a lengthy explanation of the process of the Electoral College since many people are familiar with the process.

Extended Examples

Extended examples are used when a presenter is discussing a more complicated topic that they think their audience may be unfamiliar with. In an extended example a speaker may want to use a chart, graph, or other visual aid to help the audience understand the example. An instance in which an extended example could be used includes a presentation in which a speaker is explaining how the “time value of money” principle works in finance . Since this is a concept that people unfamiliar with finance may not immediately understand, a speaker will want to use an equation and other visual aids to further help the audience understand this principle. An extended example will likely take more time to explain than a brief example and will be about a more complex topic.

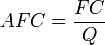

Extended Example

An equation is an extended example that’s used as a visual aid to help the audience understand a complicated topic.

Hypothetical Examples

A hypothetical example is a fictional example that can be used when a speaker is explaining a complicated topic that makes the most sense when it is put into more realistic or relatable terms. For instance, if a presenter is discussing statistical probability, instead of explaining probability in terms of equations, it may make more sense for the presenter to make up a hypothetical example. This could be a story about a girl, Annie, picking 10 pieces of candy from a bag of 50 pieces of candy in which half are blue and half are red and then determining Annie’s probability of pulling out 10 total pieces of red candy. A hypothetical example helps the audience to better visualize a topic and relate to the point of the presentation more effectively.

9.2.2: Communicating Examples

Examples help the audience understand the key points; they should be to the point and complement the topic.

Learning Objective

Use examples to help your audience understand the message being presented

Key Points

- Examples are essential to a presentation that is backed up with evidence, and they help the audience effectively understand the message being presented. An example is a specific situation, problem, or story intended to help communicate a more general idea.

- One method of effectively communicating examples is by using an example to clarify and complement a main point of a presentation.

- A speaker should be careful to not overuse examples, as too many examples may confuse the audience and distract them from focusing on the key points that the speaker is making.

Key Terms

- phenomenon

-

A fact or event considered very unusual, curious, or astonishing by those who witness it.

- abstract

-

Difficult to understand; abstruse.

Communicating Examples

Examples are essential to a presentation that is backed up with evidence, and they help the audience effectively understand the message being presented. An example is a specific situation, problem, or story intended to help communicate a more general idea. Examples are most effective when they are used as a complement to a key point in the presentation and focus on the important topics of the presentation.

Giving an Example

An example can make an abstract idea clearer.

Using Examples to Complement Key Points

One method of effectively communicating examples is by using an example to clarify and complement a main point of a presentation. If an orator is holding a seminar about how to encourage productivity in the workplace, he or she might use an example that focuses on an employee receiving an incentive (such as a bonus) to work harder, and this improved the employee’s productivity. An example like this would act as a complement and help the audience better understand how to use incentives to improve performance in the workplace.

Using Examples That Are Concise and to the Point

Examples are essential to help an audience better understand a topic. However, a speaker should be careful to not overuse examples, as too many examples may confuse the audience and distract them from focusing on the key points that the speaker is making.

Examples should also be concise and not drawn out so the speaker does not lose the audience’s attention. Concise examples should have a big impact on audience engagement and understanding in a small amount of time.

9.3: Using Statistics

9.3.1: Understanding Statistics

Statistics can be a powerful tool in public speaking if the speaker appropriately explains their use and significance.

Learning Objective

Use appropriate statistics in your speech in a way that is easy for your audience to understand

Key Points

- Understanding statistics requires creating a persuasive narrative that explains the data and an adequate explanation of why a statistic is being used, what it means and its source.

- The persuasive use of statistics is one of the most powerful tools in any rational argument, especially in public presentations.

- There are many ways to interpret statistics, however a public speaker should be mindful that they are presenting a statistic in an accurate way and not misleading the audience through a misrepresentation of a statistic.

Key Term

- statistics

-

A systematic collection of data on measurements or observations, often related to demographic information such as population counts, incomes, population counts at different ages, etc.

Understanding Statistics

Using statistics in public speaking can be a powerful tool. It provides a quantitative, objective, and persuasive platform on which to base an argument, prove a claim, or support an idea. Before a set of statistics can be used, however, it must be made understandable by people who are not familiar with statistics. The key to the persuasive use of statistics is extracting meaning and patterns from raw data in a way that is logical and demonstrable to an audience. There are many ways to interpret statistics and data sets, not all of them valid.

Guidelines for Helping Your Audience Understand Statistics

- Use reputable sources for the statistics you present in your speech such as government websites, academic institutions and reputable research organizations and policy/research think tanks.

- Use a large enough sample size in your statistics to make sure that the statistics you are using are accurate (for example, if a survey only asked four people, then it is likely not representative of the population’s viewpoint).

- Use statistics that are easily understood. Many people understand what an average is but not many people will know more complex ideas such as variation and standard deviation.

- When presenting graphs, make sure that the key points are highlighted and the graphs are not misleading as far as the values presented.

- Statistics is a topic that many people prefer to avoid, so when presenting statistical idea or even using numbers in your speech be sure to thoroughly explain what the numbers mean and use visual aids to help you explain.

Common Uses of Statistics in a Speech

Some common uses of statistics in a speech format may include:

- Results from a survey and discussion of key findings such as the mean, median, and mode of that survey.

- Comparisons of data and benchmarking results—also using averages and comparative statistics.

- Presenting findings from research, including determining which variables are statistically significant and meaningful to the results of the research. This will likely use more complicated statistics.

Common Misunderstandings of Statistics

A common misunderstanding when using statistics is “correlation does not mean causation. ” This means that just because two variables are related, they do not necessarily mean that one variable causes the other variable to occur. For example, consider a data set that indicates that there is a relationship between ice cream purchases over seasons versus drowning deaths over seasons. The incorrect conclusion would be to say that the increase in ice cream consumption leads to more drowning deaths, or vice versa. Therefore, when using statistics in public speaking, a speaker should always be sure that they are presenting accurate information when discussing two variables that may be related. Statistics can be used persuasively in all manners of arguments and public speaking scenarios—the key is understanding and interpreting the given data and molding that interpretation towards a convincing statement.

9.3.2: Communicating Statistics

Visual tools can be an effective way of incorporating statistics in your persuasive speech.

Learning Objective

Illustrate your argument by incorporating accurate statistics via visual tools.

Key Points

- Your audience is much more likely to believe you if you incorporate statistics.

- Consider using visual tools such as tables, graphs, and maps to make statistics more understandable for your audience.

Key Term

- statistics

-

A systematic collection of data on measurements or observations, often related to demographic information such as population counts, incomes, population counts at different ages, etc.

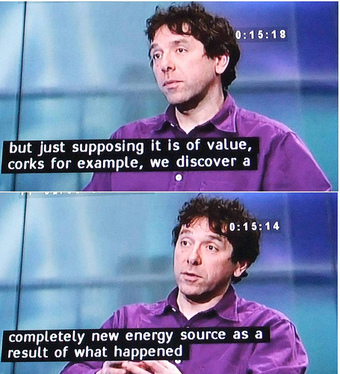

Using Visuals

Statistics is the study of the collection, analysis, interpretation, presentation, and organization of data.

Because data represent facts, incorporating statistics in your persuasive speech can be an effective way of adding both context and credibility to your argument. Your audience is much more likely to believe you if you incorporate statistics.

Statistics can be difficult to understand on their own, though. As a result, consider using visual tools such as tables, graphs, and maps to make statistics more understandable for your audience. These visuals are often easier to understand than raw data.

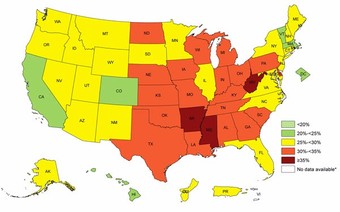

Using a Map

A map, a type of visual representation, can make data easier for the audience to understand.

9.4: Using Testimony

9.4.1: Expert vs. Peer Testimony

There are two types of testimony: expert testimony and peer testimony.

Learning Objective

Differentiate between expert testimony and peer testimony

Key Points

- A testimony is an assertion made by someone who has experience or knowledge of a particular matter.

- Expert testimony is testimony given by a person who is considered an expert by virtue of education, training, certification, skills, and/or experience in a particular matter.

- Peer testimony is given by a person who does not have expertise in a particular matter.

Key Terms

- Expert testimony

-

Testimony given by a person who is considered an expert by virtue of education, training, certification, skills, and/or experience in a particular matter.

- Peer testimony

-

Testimony given by a person who does not have expertise in a particular matter.

- testimony

-

An assertion made by someone who has knowledge or experience in a particular matter.

Introduction

A testimony is an assertion made by someone who has knowledge or experience in a particular matter.

Testimony is used in various contexts for a wide range of purposes. For example, in the law, testimony is a form of evidence that is obtained from a witness who makes a solemn statement or declaration of fact.

There are two major types of testimony: peer testimony and expert testimony.

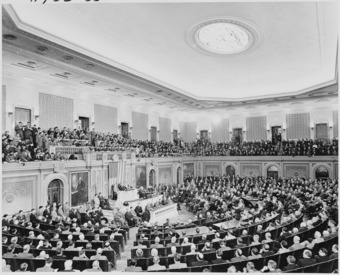

Expert Testimony

Expert testimony, as the name suggests, is testimony given by a person who is considered an expert by virtue of education, training, certification, skills, and/or experience in a particular matter. Because experts have knowledge beyond that of a typical person, expert testimony carries considerable weight. Though an expert is an authority in a particular subject, his or her testimony can certainly be called into question by other facts, evidence, or experts.

Providing Testimony

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Marine Gen. Joseph F. Dunford Jr. provides testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee on counter-ISIL operations and Middle East strategy.

Peer Testimony

Peer testimony, unlike expert testimony, is given by a person who does not have expertise in the subject in question. As a result, those who provide peer testimony are sometimes referred to as “anti-authorities.”

A person who provides peer testimony might not have expertise in a particular area, but he or she likely has personal experience with the issue at hand. Though peer testimony can easily be challenged, it can still be a powerful tool in persuading an audience, particularly when delivered or provided by a well-liked celebrity.

Questions to Consider Before Using Testimony

Before incorporating testimony, ask yourself:

- Are you quoting the testimony accurately?

- Is the testimony biased? In what way?

- Is the person providing the testimony competent and/or well respected?

- Is the testimony current?

- How will your audience respond to the testimony?

9.4.2: How to Incorporate Expert Testimony

Expert testimony can be incorporated after introducing a point of your argument.

Learning Objective

State why it is beneficial to incorporate expert testimony into a speech

Key Points

- Expert testimony should be incorporated to support, defend, or explain the main point or subpoint of a speech.

- Limiting your main points, subpoints, and support points to three or four points each improves the ability for your speech to communicate with the audience.

- Noticing how professionals use the testimony of experts can provide creative examples for how to incorporate expert testimony into a speech.

Key Terms

- expert

-

A person with extensive knowledge or ability in a given subject.

- TED

-

Technology Entertainment Design, a series of global conferences.

Introduction

Once you have found experts to support your ideas, you may wonder how to incorporate their testimony into your speech. The following will give you an idea of how to incorporate expert testimony in order to support your argument and improve your speech.

What the Body of Your Speech Should Include

The body of your speech should help you elaborate and develop your main objectives clearly by using main points, subpoints, and support for your sub points. To ensure that your speech clearly communicates with your audience, try to limit both your main points and subpoints to three or four points each;this applies to your supporting points, as well. Expert testimony is considered supporting point; it is used to support the main and subpoints of your speech.

When a claim or point is made during a speech, the audience initially may be reluctant to concede or agree to the validity of the point. Often this is because the audience does not initially accept the speaker as a trustworthy authority. By incorporating expert testimony, the speaker is able to bolster their own authority to speak on the topic.

Therefore, expert testimony is commonly introduced after a claim is made. For example, if a speech makes the claim, “Manufacturing jobs have been in decline since the 1970s,” it should be followed up with expert testimony to support that claim. This testimony could take a variety of forms, such as government employment statistics or a historian who has written on a particular sector of the manufacturing industry. No matter the particular form of expert testimony, it is incorporated following a claim to defend and support that claim, thus bolstering the authority of the speaker.

Example of Incorporating Expert Testimony

Search for and watch a TED talk by Barry Schwartz, Professor of Social Theory and Social Action at Swarthmore College. Notice how Schwartz references expert testimony in the course of his speech to justify his point to the audience.

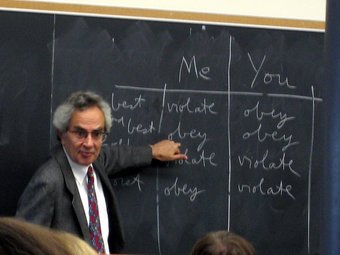

Barry Schwartz

Incorporating testimony from experts supports and clarifies claims made during a speech.

Schwartz begins by showing the job description of a hospital janitor, noting that the tasks do not require interaction with other people. However, Schwartz introduces the expert testimony of actual hospital janitors as a way to complicate the apparent solo nature of janitorial work. Schwartz personalizes the experts with proper names, “Mike,” “Sharleene,” and “Luke,” and uses their testimony to demonstrate that despite the job description, janitors take social interaction to be an important part of their job.

In this instance, Schwartz incorporates the expert testimony of actual janitors as a both a foil and a support. The testimony shows that in fact janitorial work does include interaction with other people, thus foiling the initial presentation of janitorial work as solitary. In addition, Schwartz uses the testimony of these experts to show that they embody the characteristics of wisdom that Schwartz will describe in the remainder of the speech.

9.5: Using Other Supporting Materials

9.5.1: Analogies

Analogies draw comparisons between ideas or objects that share certain aspects or characteristics, but are dissimilar in other areas.

Learning Objective

Define analogies and how they can be used as a linguistic tool in public speaking

Key Points

- Analogies compare something new and different (the main topic of a speech) to people, places, objects, and ideas familiar to audience members.

- Public speakers often use analogies to strengthen political and philosophical arguments, even when the semantic similarity is weak or non-existent.

- Analogies that begin with phrases including “like”, “so on,” and “as if” rely on an analogical understanding by the receiver of a message that includes such phrases.

- Considering audience demographics, and constructing similar rather than extreme analogies, are tactics public speakers use to create effective analogies.

Key Terms

- homomorphism

-

A similar appearance of two unrelated organisms or structures.

- iconicity

-

The state of being iconic (in all meanings).

- isomorphism

-

A one-to-one correspondence.

Example

- Some examples of analogies: the human eye is like a camera, love is a kind of game, sound waves are like the circular ripples that spread from a stone dropped in water.

Analogies

Analogies draw comparisons between ideas or objects that share certain aspects or characteristics, but are dissimilar in other areas. This cognitive process transfers information or meaning from one particular subject (the analogue or source) to another particular subject (the target) to infer meaning or prove an argument. In public speaking, analogy can be a powerful linguistic tool to help speakers guide and influence the perception and emotions of the audience.

Using Analogies

Analogies often use the structure “A is like B.” For example, the human eye is like a camera.

Analogies in Public Speaking

Linguistically, an analogy can be a spoken or textual comparison between two words (or sets of words) to highlight some form of semantic similarity between them. Thus, public speakers often use analogies to strengthen political and philosophical arguments, even when the semantic similarity is weak or non-existent (if crafted carefully for the audience).

Often presenters speak about topics, concepts, or places that may seem alien or abstract for audiences. To build trust and credibility on stage, speakers repeatedly link their main topic or argument to the values, beliefs, and knowledge of their audience. Demonstrating how the relationship between one set of ideas is comparable or similar to a different set ideas helps bridge this gap in understanding for listeners unable to formulate the relationship on their own. Likewise, analogies are sometimes used to persuade those that cannot detect the flawed or non-existent arguments within the speech.

The Construction and Role of Analogies in Language

Analogies that begin with phrases including “like,” “so on,” and “as if” rely on an analogical understanding by the receiver of a message that includes such phrases. Analogy is important not only in ordinary language and common sense (where proverbs and idioms give many examples of its application ), but also in science, philosophy, and the humanities. Presenters and writers also use analogies to enhance and enliven descriptions, and to express thoughts and ideas more clearly and precisely.

The concepts of association, comparison, correspondence, mathematical and morphological homology, homomorphism, iconicity, isomorphism, metaphor, resemblance, and similarity are closely related to analogy. In cognitive linguistics, the notion of conceptual metaphor may be equivalent to that of analogy.

Tips for Using Analogies

- Think about audience demographics. What are their interests, beliefs, and values? Choose a suitable analogy that the audience will be able to connect with and relate to.

- Keep analogies short and simple. Extreme analogies can weaken rather than strengthen an argument.

- Use analogies as a springboard rather than as the main focus of the presentation.

- Use analogies from personal experiences to create authenticity and credibility with the audience.

9.5.2: Definitions

It is easier to support your ideas when you provide definitions ensuring that you and your audience are working with the same meaning.

Learning Objective

State how defining key terms creates credibility for public speakers

Key Points

- Providing the definition of the key terms also works as a signal to your audience that you know what you’re talking about.

- In order to define the key terms, you first have to bluntly state what they are.

- Very often, you’ll use the work of somebody else to help you define the key terms.

Key Term

- concept

-

An understanding retained in the mind, from experience, reasoning and/or imagination; a generalization (generic, basic form), or abstraction (mental impression), of a particular set of instances or occurrences (specific, though different, recorded manifestations of the concept).

Example

- You can define fruit salad as consisting of bananas, pineapples, and yellow apples (ideally you would have a reason for this, too). Having done so, your audience will not object when you later state that fruit salad lacks the vital bits of red. Your definition of a fruit salad has supported this idea.

Introduction

During the introduction to your speech or presentation, you’ve given your audience a promise. You’ve told them that in exchange for their attention, you are going to deliver some information that answers the question which spawned the presentation in the first place.

Now you are giving the main part of your speech, and your audience expects you to deliver as promised.

There’s just one problem. Even though you’ve already decided what to include in the answer, you realize that there are times when the listeners may lose focus because they aren’t following you.

One way to make sure that your answer is focused is to tell your audience what you are talking about. In other words, define your key terms. In doing this, you do two things: First, you show that you know what you are speaking about. Second, you avoid misunderstandings by settling on a single understanding of the key terms. It might be that your audience understands power in a Marxist way, and you want to approach the presentation from a feminist point of view. By providing a brief definition, there will be no misunderstanding. Your audience may not agree with you, but that is not necessary to get your point across.

A definition makes sure you and your audience are talking about the same things.

For example, you can define fruit salad as consisting of bananas, pineapples, and yellow apples (ideally you would have a reason for this, too). Having done so, your audience will not object when you later state that fruit salad lacks the vital bits of red. Your definition of a fruit salad has supported this idea.

Using a Dictionary

A dictionary is the most obvious place to find definitions, but other sources can be used as well.

Providing Definitions

In order to define the key terms, you first have to bluntly state what they are. Always include the key words included in the question. These have been identified as central concepts for you, and by excluding them, you’ll be very likely answering a different question from the one set.

There are often other key terms you want to include, and it’s usually worth spending some time thinking about which ones are the key concept. The number of definitions you include will depend on the length of your speech. Sometimes it takes a bit of time to think which terms are the central ones. This is time worth spending, because you can later use the concepts without giving any further qualifications or comments. For this reason, you should also define the terms carefully.

Having defined “power” in a particular way, every time you use the term in the presentation, it will have the meaning you desire.

Providing the definition of the key terms also works as a signal to your audience that you know what you’re talking about. By defining “power” in a certain way, you demonstrate that you’re aware of other interpretations. In fact, it will usually not be necessary to state what the other interpretations are, unless the distinction is a key aspect of the argument.

It is easy to support your ideas once you’ve created credibility.

Examples

Very often, you’ll use the work of somebody else to help you define the key terms. The following two paragraphs define the concepts “social disadvantage” and “siblings. ” The definitions are taken from a range of sources, and referenced accordingly. In the context of another speech or presentation, these definitions may be too long or too short.

Social disadvantage, to start with, refers to a range of difficulties a person can be exposed to. According to McLanahan and Sandefur, social disadvantages include a lower expectancy in educational attainment, lower prospects at work, or lower status in society. Steinberg demonstrated that social and economic disadvantages in society often come together, leading some sociologists talking about underclasses. Social disadvantage, however, does not necessarily have to be as extreme as that: it describes a relative difficulty in reaching a similar position in society than people not disadvantaged.

Siblings, finally, in the context of this presentation, refer to brothers and sisters of the same birth family. This

means

that siblings are biologically related, as well as living in the same family.

9.5.3: Visual Demonstrations

Visual aids are often used to help audiences of informative and persuasive speeches understand the topic being presented.

Learning Objective

List the different ways visual aids add impact to a presentation

Key Points

- Visual aids are often used to help audiences of informative and persuasive speeches understand the topic being presented.

- The use of objects as visual aids involves bringing the actual object to demonstrate on during the speech.

- Models are representations of another object that serve to demonstrate that object when use of the real object is ineffective for some reason (e.g., the solar system).

- Maps show geographic areas that are of interest to the speech. They often are used as aids when speaking of differences between geographical areas or showing the location of something.

- Drawings or diagrams can be used when photographs do not show exactly what the speaker wants to show or explain.

Visual aids are often used to help audiences of informative and persuasive speeches understand the topic being presented. Visual aids can play a large role in how the audience understands and takes in information that is presented. There are many different types of visual aids that range from handouts to PowerPoints. The type of visual aid a speaker uses depends on their preference and the information they are trying to present. Each type of visual aid has pros and cons that must be evaluated to ensure it will be beneficial to the overall presentation. Before incorporating visual aids into speeches, the speaker should understand that if used incorrectly, the visual will not be an aid, but a distraction.

Planning ahead is important when using visual aids. It is necessary to choose a visual aid that is appropriate for the material and audience. The purpose of the visual aid is to enhance the presentation.

Objects

The use of objects as visual aids involves bringing the actual object to demonstrate on during the speech. For example, a speech about tying knots would be more effective by bringing in a rope.

- Pro: the use of the actual object is often necessary when demonstrating how to do something so that the audience can fully understand procedure.

- Con: some objects are too large or unavailable for a speaker to bring with them.

Models

Models are representations of another object that serve to demonstrate that object when use of the real object is ineffective for some reason. Examples include human skeletal systems, the solar system, or architecture.

- Pros: models can serve as substitutes that provide a better example of the real thing to the audience when the object being spoken about is of an awkward size or composure for use in the demonstration.

- Cons: sometimes a model may take away from the reality of what is being spoken about. For example, the vast size of the solar system cannot be seen from a model, and the actual composure of a human body cannot be seen from a dummy.

Graphs

Graphs are used to visualize relationships between different quantities. Various types are used as visual aids, including bar graphs, line graphs, pie graphs, and scatter plots.

- Pros: graphs help the audience to visualize statistics so that they make a greater impact than just listing them verbally would.

- Cons: graphs can easily become cluttered during use in a speech by including too much detail, overwhelming the audience and making the graph ineffective.

Maps

Maps show geographic areas that are of interest to the speech. They often are used as aids when speaking of differences between geographical areas or showing the location of something.

- Pros: when maps are simple and clear, they can be used to effectively make points about certain areas. For example, a map showing the building site for a new hospital could show its close location to key neighborhoods, or a map could show the differences in distribution of AIDS victims in North American and African countries.

- Cons: inclusion of too much detail on a map can cause the audience to lose focus on the key point being made. Also, if the map is disproportional or unrealistic, it may prove ineffective for the point being made.

Tables

Tables are columns and rows that organize words, symbols, and/or data.

- Pros: Good tables are easy to understand. They are a good way to compare facts and to gain a better overall understanding of the topic being discussed. For example, a table is a good choice to use when comparing the amount of rainfall in 3 counties each month.

- Cons: Tables are not very interesting or pleasing to the eye. They can be overwhelming if too much information is in a small space or the information is not organized in a convenient way. A table is not a good choice to use if the person viewing it has to take a lot of time to be able to understand it. Tables can be visual distractions if it is hard to read because the font is too small or the writing is too close together. It can also be a visual distraction if the table is not drawn evenly.

Photographs

- Pros: Photographs are good tools to make or emphasize a point or to explain a topic. For example, when explaining the shanty-towns in a third word country it would be beneficial to show a picture of one so the reader can have a better understanding of how those people live. A photograph is also good to use when the actual object cannot be viewed. For example, in a health class learning about cocaine, the teacher cannot bring in cocaine to show the class because that would be illegal, but the teacher could show a picture of cocaine to the class. Using local photos can also help emphasize how your topic is important in the audience’s area.[8]

- Cons: If the photograph is too small it just becomes a distraction. Enlarging photographs can be expensive if not using a power point or other viewing device.

Drawings or diagrams

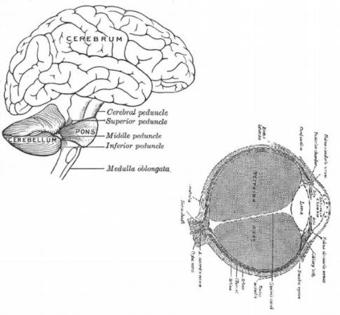

Using a Diagram

Diagrams are used to convey detailed information.

- Pros: Drawings or diagrams can be used when photographs do not show exactly what the speaker wants to show or explain. It could also be used when a photograph is too detailed. For example, a drawing or diagram of the circulatory system throughout the body is a lot more effective than a picture of a cadaver showing the circulatory system.

- Cons: If not drawn correctly a drawing can look sloppy and be ineffective. This type of drawing will appear unprofessional.

9.6: Using Life Experience (Narrative)

9.6.1: The Importance of Stories

Because human life is narratively rooted, incorporating story telling into public speaking can be a powerful way of reaching your audience.

Learning Objective

State why effective storytelling is a key component of public speaking

Key Points

- Storytelling is the conveying of events in words, sound and/or images, often by improvisation or embellishment.

- Stories are universal in that they can bridge cultural, linguistic and age-related divides.

- Communicating by using storytelling techniques can be a more compelling and effective route of delivering information than that of using only dry facts.

Key Term

- Storytelling

-

The conveying of events in words, sound and/or images, often by improvisation or embellishment.

Storytelling

Storytelling is the conveying of events in words, sound and/or images, often by improvisation or embellishment. Stories or narratives have been shared in every culture as a means of entertainment, education, cultural preservation and instilling moral values.

Telling a Story

A seafarer tells the young Sir Walter Raleigh and his brother the story of what happened out at sea.

The Power of Storytelling

Storytelling is a powerful tool, a means for sharing experiences and knowledge. It’s one of the ways we learn. Peter L. Berger says human life is narratively rooted, humans construct their lives and shape their world into homes in terms of these groundings and memories. Stories are universal in that they can bridge cultural, linguistic and age-related divides.

The Utility of Storytelling in Public Speaking

Because human life is narratively rooted, incorporating story telling into public speaking can be a powerful way of reaching your audience. For example, communicating by using storytelling techniques can be a more compelling and effective route of delivering information than that of using only dry facts.

9.6.2: How and When to Use Narrative

Presenters use narratives to support their points and make their speeches more compelling.

Learning Objective

Explain how to use narrative in speeches

Key Points

- A narrative is relayed in the form of a story.

- The greatest story commandment is to make the audience care.

- Your story should not be forced; the audience should perceive it as natural part of your speech.

Key Term

- narrative

-

The systematic recitation of an event or series of events. (see also storytelling)

How and When to Use Narrative

Whatever the purpose of your speech, you’re going to need a way to support your statements to prove their accuracy, but a good speech also makes its points interesting and memorable.

The most common forms of support are facts, statistics, testimony, narrative, examples, and comparisons. In this unit, we are going to address narrative .

Using a Narrative

Narratives can be used to support a point that has been made or is about to be made.

The Narrative

Narrative takes the form of a story. Presenters use narratives to support a point that was already made or to introduce a point that will soon be made. Narratives can be combined with facts or statistics to make them even more compelling.

How to Use a Narrative

- Storytelling points toward a single goal. Your story should not be forced, but should come across as a natural part of your speech. If your audience thinks you’re telling a story just because you read that it was a good idea to do so, your story won’t work.

- The task of a story is to make the audience care. Your narrative should be something that your audience can easily understand and relate to.

- Keep it short and sweet. Limit your narrative to three or four minutes at the most. Remember, you are using it to support or clarify your point. Once you’ve done that, move on.

- Your story is not there to replace information. It is there to put something you have said into perspective.

- The best stories paint a picture. They allow your audience to visualize what you are saying.

- Make sure your story builds over time and doesn’t get boring. Keep your audience interested until the end.

- Don’t overuse stories.

- Of course, as the old adage says, “use what you know.” Stories are not just about facts—they’re also about communicating what you have experienced and what you personally know, and feel, to be true.

Chapter 8: Topic Research: Gathering Materials and Evidence

8.1: Gathering Evidence: An Overview

8.1.1: The Importance of Gathering Information

Gathering information can help speakers gain credibility and make their speech current and relevant.

Learning Objective

Explain how gathering research can provide additional credibility to a speech

Key Points

- Don’t simply rely on your own expertise to carry you through the speech. Seek out information to support your arguments and gain credibility with the audience.

- Instead of relying on generalizations or common sense, find current information to update your interpretation of the topic.

- Gather specialized information that will make your speech more relevant to your particular audience.

Key Term

- evidence

-

The available body of facts or information indicating whether a belief or proposition is true or valid.

Example

- See which of these two statements is more insightful: 1. Teenagers spend too much time with their electronic gadgets. This obsession takes them away from the real world and leaves them unprepared for adult life. 2. According to a recent study from the Kaiser Family Foundation, teenagers spend over seven and a half hours a day using electronic devices—mainly smartphones, computers, and TVs. This preoccupation leaves little time to give undivided attention to homework, family time, and extracurricular activities, all of which are essential steps toward adult life.

Why Gather Information?

If you are already an expert on your topic, why should you take the time to gather more information? Personal expertise is a great source of anecdotes, illustrations, and insights about important issues and questions related to your topic. However, one person’s opinion holds less weight than an opinion that is shared by other experts, supported by evidence, or validated by testimonials. The process of gathering information provides opportunities to step beyond the limitations of your own experience and enrich your own understanding of your topic. Here are a few of the benefits you can reap from gathering information:

Gain Credibility

If you want the audience to trust your claims, back them up. Don’t expect the audience to take your word for it, no questions asked. Find evidence, illustrations, anecdotes, testimonials, or expert opinions that support your claims. Compare these two statements—the first is a personal opinion, and the second is an argument supported with evidence. Which statement sounds more credible?

- I believe that building a parking garage near the town square would bring more traffic to local businesses and boost the local economy. Everyone knows it’s impossible to find parking on weekends here, and that keeps a lot of people at home on weekends.

- Small businesses in our sister city, Springfield, reported losses comparable to ours after the financial crisis. However, everything changed for them last year: businesses reported that sales were up, and a few new businesses opened in the center of town, creating new jobs. Why didn’t we get the same result? The mayor of Springfield credits the change to a new parking garage near the city center, which eased the parking shortage and brought more people into town on weekends. What can we learn from this story? There are people out there who want to patronize local businesses but are being driven away by the lack of parking. The plan for a new parking garage in our town square could bring us the same success we saw in Springfield.

Gaining Credibility

A parking garage in another city provides “concrete” evidence (pun intended) to support your argument that the structure encourages people to shop downtown.

The first statement relies on a “common sense” idea about parking convenience, which the audience may or may not agree with. By providing an example of a similar situation, the second statement lends credibility to the claim that a new parking garage would help the local economy.

Make It Current

If you want to assure your audience that you are well-informed about your topic, provide current information about it. Instead of relying on generalizations, gather up-to-date information about the particulars of your topic. See which of these two statements is more insightful:

- Teenagers spend too much time with their electronic gadgets. This obsession takes them away from the real world and leaves them unprepared for adult life.

- According to a recent study from the Kaiser Family Foundation, teenagers spend over seven and a half hours a day using electronic devices—mainly smartphones, computers, and TVs. This preoccupation leaves little time to give undivided attention to homework, family time, and extracurricular activities, all of which are essential steps toward adult life.

The first statement relies on unfounded opinions, leaving gaping holes in its argument. Perhaps teenagers do spend too much time with their devices, but how much time do they spend and why is it a problem? It sounds like a curmudgeonly rant about “kids these days.” The second statement backs its claim up with evidence from a recent study and lists specific problems. Recent information makes it possible to define the problem clearly.

Keep It Relevant

Different audiences have different needs. When you conduct an audience analysis, you will gain valuable demographic information—and you should use that information to guide the search for supporting evidence and illustrations. What would resonate with that particular group of people?

Let’s say you are counseling an audience of nursing students in Florida about their job prospects. If you have general knowledge about nursing jobs, you have a good starting point. If you seek out information about the current market for nursing jobs in Florida, you will have information that is even more valuable to your audience. Make sure your speech is relevant to your audience: take the time to build on your area of expertise by gathering specialized information to fit the occasion.

8.1.2: Sources of Information

When you begin the research process, explore a variety of sources to discover the most useful information.

Learning Objective

State the best practices for conducting research

Key Points

- Research librarians can help you get started on the research process. They can also help you refine your research and save time.

- If you’re looking for the most current information about your topic, look for articles. Make sure their sources are trustworthy, though!

- When you are evaluating the credibility of a source, use the ADAM protocol: Age (how old is the information), Depth (how detailed is the information), Author (how qualified and reputable is the author), and Money (how monetary benefits may have produced biased information).

Key Term

- bibliography

-

A list of books or documents relevant to a particular subject or author.

Sources of Information

Library

Libraries provide many different resources for research, including research librarians, specialized databases, scholarly journals, and, of books.

Research Librarians

When it comes to research, do you feel completely lost, with no idea how or where to start looking for information? In these cases, a research librarian can be a real godsend. Research librarians are trained to give helpful advice about structuring the research process and looking in the right places for relevant information. Even if you’re comfortable with research, a research librarian may be able to save a lot of time by helping you refine your search.

Bibliographies

A bibliography is a collection of publication information about books, articles, and other resources that address a particular topic. You may be surprised to discover how many topics have bibliographies dedicated specifically to them, from very specific topics such as the novel David Copperfield to broader topics such as American environmental history. Annotated bibliographies are especially helpful, since they provide a summary of each resource listed.

Books

If you are looking for general information about your topic, encyclopedias and other reference books are a great place to start. If you want something more specific, search for informative books about your topic and anthologies that include essays or articles about relevant issues.

Specialized Search Engines and Databases

Specialized search engines and databases make it easier to target specific information and filter out irrelevant material. If you are affiliated with a university, you probably have free access to research databases such as JSTOR, EBSCO, ProQuest, and LexisNexis Academic. These services provide a variety of search criteria for finding relevant academic articles and news stories. If you are conducting independent research, try Google Scholar, which is free for everyone.

Articles

If you want the most up-to-date sources of information about your topic, look for articles in academic journals and news publications. The Internet is a great resource for finding articles, but you have to be careful—make sure your sources are trustworthy. Books and articles published in academic journals usually go through a lengthy peer review process that verifies the author’s expertise and the material’s accuracy. Online publications and blogs may not have such reliable fact-checking procedures. If you find useful information in an unfamiliar online source, try to verify it elsewhere before incorporating it into your speech.

ADAM

The “ADAM” protocol is a great way to evaluate the credibility of a resource. Consider these criteria:

- Age: Is the source recent? For most topics, current articles are more reliable than old articles, although some topics call for older research.

- Depth: How deep and detailed is the analysis? Are its claims supported by valid evidence?

- Author: What are the author’s qualifications? Do the author’s biography and reputation raise the possibility of potential conflicts of interest or biases? What is the author’s agenda in writing the article?

- Money: Are the authors or publishers affiliated with institutions or corporations that have material benefits at stake in the issue?

News Sources vs. Scholarly Sources

News sources often contain both factual content and opinion content. News reporting from less-established outlets is generally considered less reliable for statements of fact. Editorial commentary, analysis and opinion pieces, whether written by the editors of the publication (editorials) or outside authors (op-eds) are reliable primary sources for statements attributed to that editor or author, but are rarely reliable for statements of fact. When taking information from opinion content, the identity of the author may help determine reliability. The opinions of specialists and recognized experts are more likely to be reliable and to reflect a significant viewpoint.

For information about academic topics, scholarly sources and high-quality non-scholarly sources are generally better than news reports. News reports may be acceptable depending on the context. Articles which deal in depth with specific studies, as a specialized article on science, are apt to be of more value than general articles which only tangentially deal with a topic. Frequently, although not always, such articles are written by specialist writers who may be cited by name.

8.1.3: Research Tips: Start Early, Use a Bibliography, and Evaluate Material Critically

Start the research process early, consult a bibliography to find credible sources, and evaluate those sources critically.

Learning Objective

Explain why starting research early, using a bibliography, and evaluating material critically is crucial to the research process

Key Points

- Even seasoned public speakers start preparing early—follow their lead!

- Bibliographies, which compile many different sources that address a particular topic, are great research tools.

- Make sure you understand the context of your research, especially if you are looking at unfamiliar sources.

Key Terms

- critical thinking

-

he application of logical principles, rigorous standards of evidence, and careful reasoning to the analysis and discussion of claims, beliefs, and issues

- bibliography

-

A list of books or documents relevant to a particular subject or author.

By failing to prepare you are preparing to fail. -Benjamin Franklin

Well begun is half done. -Aristotle

Start Early

Mark Twain once said, “It usually takes me more than three weeks to prepare a good impromptu speech. ” If it took that long for Mark Twain, one of the most eloquent speakers in American history, to write a “good impromptu speech,” students of public speaking should take note and get a nice, early start on the research process. American philosopher Wayne Burgraff estimated that speakers should spend one hour of preparation for every minute of presentation .

The Early Bird

As the saying goes, “the early bird gets the worm. ” When you start the research process early, you have time to find and incorporate the most relevant sources.

Use a Bibliography

Consulting a bibliography will make your research process more efficient. Bibliographies compile publication information about books, articles, and other resources that address a particular topic. Some bibliographies appear as standalone books, while others appear in academic journals or online resources. Annotated bibliographies summarize the main argument of each resource. If a bibliography is recent enough, it can be a one-stop shop for all of your research needs, pointing to many credible sources. However, if the bibliography is old, or if you need the most current information about your topic, you should fill the gap between the end of the bibliography and the present time by looking for articles and books from that time period.

Evaluate Material Critically

90% of everything is garbage! -Theodore Sturgeon

“90% of everything” might be an exaggeration, but, sadly, there is a lot of garbage out there. If you carefully evaluate your sources to make sure they are credible, you stand to save yourself a lot of trouble. Here’s a cautionary tale: Iranian news outlet Fars became a laughingstock after it picked up an American news story claiming that the majority of white Americans in rural areas would rather vote for Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad than President Barack Obama. That doesn’t sound quite right, does it? Of course, the original story came from The Onion, a satirical newspaper. If the journalists at Fars had checked out their source, they could have avoided an embarrassing mistake. Use your critical thinking skills to make sure you understand the context of your research!

Reliable sources must be strong enough to support the claim. A lightweight source may sometimes be acceptable for a lightweight claim, but never for an extraordinary claim.Questionable sources are those with a poor reputation for checking the facts, or with no editorial oversight. Such sources include websites and publications expressing views that are widely acknowledged as extremist, that are promotional in nature, or which rely heavily on rumors and personal opinions. Questionable sources are generally unsuitable for citing contentious claims about third parties, which includes claims against institutions, persons living or dead, as well as more ill-defined entities. The proper uses of a questionable source are very limited.

Sometimes “non-neutral” sources are the best possible sources for supporting information about the different viewpoints held on a subject. When dealing with a potentially biased source, editors should consider whether the source meets the normal requirements for reliable sources, such as editorial control and a reputation for fact-checking. Editors should also consider whether the bias makes it appropriate to use in-text attribution to the source. Each source must be carefully weighed to judge whether it is reliable for the statement being made and is an appropriate source for that content. In general, the more people engaged in checking facts, analyzing legal issues, and scrutinizing the writing, the more reliable the publication.

8.2: Library Research

8.2.1: Finding Materials in a Library

Physical materials are categorized by a numbering system, and digital materials are easily searchable on library computers.

Learning Objective

Summarize the best practices for finding library materials

Key Points

- All physical materials such as books and DVDs are labeled according to a system, such as the Dewey Decimal Classification. The label corresponds to the material’s location in the library.

- Digital materials, such as databases, are easily searchable from the library’s computers. The homepage will help you determine which source to use and will then direct you to the source.

- Librarians remain one of the best ways to find materials in a library. Their knowledge and expertise can make research must easier.

Key Terms

- database

-

A structured collection of data, typically organized to model relevant aspects of reality (for example, the availability of rooms in hotels), in a way that supports processes requiring this information (for example, finding a hotel with vacancies).

- Dewey Decimal Classification

-

A system that sorts and organizes all of a library’s physical materials. The most common categorization system in American public libraries.

Introduction

Finding the correct information in a library can be a daunting task given the sheer number of resources. To make things easier, libraries have adopted classification systems.

Searching for Materials

There are a number of ways to begin the search for materials.

- You can just jump right in and start searching which is great if you know where to look, but frustrating if you don’t.

- You can go to the library computers which are linked to the library database of material. This allows you to put in the name of the author, the title, or a keyword to find out what materials might contain the information you are looking for.

- You can also simply ask a librarian. Even as more and more information is digitalized, asking a librarian remains one of the most effective ways to find information.

Finding Physical Materials

Physical materials (e.g., books, manuscripts, CDs) are categorized by a series of numbers and letters. The main systems of classification are the Dewey Decimal Classification, the Library of Congress Classification, and the Colon Classification. Though most public libraries use the Dewey Decimal Classification, all of the systems work in essentially the same way.

Each physical piece of material is assigned a number that relates to a hierarchical structure. The first numbers will be the broad subject (e.g., 300 is economics), the following numbers correspond to a subcategory (e.g., .94 is European economy) and so on.

Dewey Decimal Categorization

Library books have a sticker with a categorization number on them. Books are sorted and organized based on the numbers.

Since the materials are placed in order on the shelves, finding the material is a matter of just finding the section with the corresponding codes.

Of course, not all materials are on the shelves at all times. Libraries can reserve a copy or order it from a partner library. They will contact you when the material comes in so you can come pick it up.

Finding Digital Materials

To use the library’s digital materials, such as e-books or subscription-based databases, you need to use one of the library’s computers. In some libraries, it’s enough to just be using the library’s wifi, but either way, the materials are not accessible without being at the library.

The library computers should provide links to different databases with a brief description of what the database is good for. Then, you can go to the database and search the materials just as you would on Google.

8.2.2: Types of Material in a Library

Libraries offer physical, digital, and human resources which can help you research subjects efficiently.

Learning Objective

Discuss how borrowers can take advantage of physical, digital, and people resources in libraries

Key Points

- Librarians can help you determine the best resources to use and introduce you to any technology or software you might need to access them.

- Libraries have physical resources such as books, maps, manuscripts, and periodicals.

- Libraries can provide free access to digital resources such as e-books and databases that are often inaccessible without a subscription.

Key Term

- database

-

A structured collection of data, typically organized to model relevant aspects of reality (for example, the availability of rooms in hotels), in a way that supports processes requiring this information (for example, finding a hotel with vacancies).

Although libraries are normally associated with books, they have numerous other research resources, many of which are beyond the scope of what is easily accessible at home or on the Internet. Moreover, while libraries have a plethora of both physical and digital resources, some of their most valuable assets are their human resources. Librarians are knowledgeable about what information is accessible from each resource and can make your research efforts easier and more efficient.

Physical Resources

Libraries house a number of resources that you can locate, handle, and use immediately . These physical resources include periodicals, magazines, newspapers, maps, and manuscripts, though some may be used only at the library. In addition, many libraries provide media resources such as films, prints, CDs, cassettes, and videos that you can access during your visit. Of course, libraries also have books on a variety of subjects and often have book-sharing arrangements with other libraries, too. If you need a book that is not on the shelves, ask a librarian to order it for you, if possible. Some libraries can also arrange inter-library loans of media resources, too.

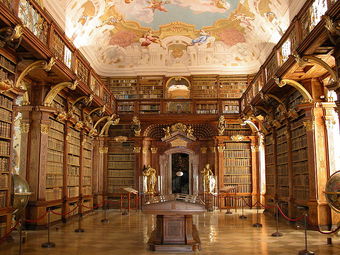

Melk Abbey Library

Books are the primary resource in a library, but there are many more resources that can aid in research.

Digital Resources

The advent of digital resources has greatly expanded the walls of libraries. Now, libraries have resources such as e-books and online databases which are not limited to physical locations within the library.

Databases, in particular, are useful for researchers because they allow you to search for information by topic, category, author, date or other useful traits. However, many of the best databases are subscription based, so unless you work for a company that has a subscription or attend a university with one, the only practical (and affordable) place to get access is in the library.

Databases may specialize in a certain field such as medicine, business, or engineering. These databases provide access to not only historical information, but also information that is not easily found through search engines like Google. The in-depth and historical information makes these databases one of the most valuable resources in the library.

Human Resources

Because libraries can house and/or access so much information, you may not discover what you need until you have spent a lot of time exploring what is available. Enlisting the help of a librarian can often save you time because librarians are trained to evaluate all of their libraries’ resources, including the best ways for you to access them and whether they are the appropriate given your specific needs or interests. Librarians can also help you quickly learn to use technology or software, such as microfiche readers or database search programs, which you may need to complete your research.

8.3: Internet Research

8.3.1: Finding Materials on the Internet

Internet search engines are powerful tools for delivering easily accessible sources of information in the research process.

Learning Objective

Identify ways to use search engines to find information on the Internet

Key Points

- If you find yourself with an unfamiliar topic, you can orient yourself by conducting a general, preliminary overview search using Internet search engines.

- Don’t limit yourself to just one search engine; Google, Bing, Yahoo!, Ask, and AOL Search comprise the top five search engines in the U.S. and each do certain types of searches better than others.

- Use Boolean operators like AND, OR, and NOT to refine and specify your search queries for accurate research results.

Key Terms

- search engine

-

an application that searches for, and retrieves, data based on some criteria, especially one that searches the Internet for documents containing specified words

- keyword

-

To tag with keywords, as for example to facilitate searching.

Using the Internet As a Research Source

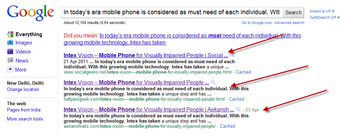

As you gather research for your speech, you’ll want to have a variety of sources from which to compile supporting evidence and facts. With the advent of digital archiving, social media, and open-source education, it’s easier than ever before to find information on the Internet .

Using the Internet

With such widespread accessibility, the Internet allows you to conduct research from just about anywhere.

Why Use the Internet?

The Internet is pervasive, easily accessible, and continually updated. It only makes sense to capitalize on this ever-evolving technology as a resource for your speech research.

In addition to convenience and accessibility, the Internet allows you to access resources to which you may not have the physical means to get previously. You might not be able to just hop on a plane to Paris and see DaVinci’s La Jaconde (more commonly known as the Mona Lisa), but thanks to the Internet, you can now browse the hundreds of works at Le Louvre right from the convenience of your laptop.

The Internet is also an excellent way to familiarize or orient yourself with an unfamiliar speech topic. While you might not be able to cite every informational source you find, using the Internet in your research process is a fast way to get yourself familiar with the basics of your speech topic, thesis, or key supporting points and arguments.

The Art Of the Search Query

When getting started with most Internet research, the first thing you’ll do is open up your Internet browser and open to a search engine. While Google may dominate the search engine market, recognize that Bing, Yahoo!, Ask, and AOL Search round out the top five most popular search engines in the United States. Other popular search engines include Wolfram Alpha and Instagrok.com. Using different search engines may yield different results, so don’t limit yourself to just one search engine. Additionally, some search engines excel at certain types of information and searches more than others.

Internet information, particularly of a certain quality or standard, can be organized in other ways besides word choice and prominence (as attended by global search engines). Some information may also require further search skills to retrieve. A familiarity with midpoints like directories, “invisible” databases and an attentiveness to further types of organization may reveal the key to finding missing information. A thesaurus, for example, may prove critical to connecting information organized under the business term “staff loyalty” to information addressing the preferred nursing term “personnel loyalty” (MeSH entry for Medline by the [US] National Library of Medicine).

While each search engine may have specific search query shorthand, almost all major search engines function by using Boolean logic and Boolean search operators. Boolean logic symbolically represents relationships between entities and uses three key search operators. These operators help you form your search query:

- AND: The AND operator connects two or more terms to retrieve information that matches all of those terms. If, for example, you were searching for information about the freedom of speech in the United States, you might search for “freedom AND United States. “

- OR: The OR operator searches for information that includes at least one of the keywords included in your query. If you were researching on court cases about freedom of speech, you might search for “freedom of speech OR amendment. “

- NOT: The NOT operator excludes any keywords following the operator and retrieves the appropriate information excluding those terms. If you wanted to find out more about free speech in schools but not anything related to Supreme Court cases, you might search for “freedom of speech NOT Supreme Court. “

8.3.2: Types of Material on the Internet

The Internet can provide you with a wealth and variety of resources for your research process.

Learning Objective

List types of sources that can be found using the Internet

Key Points

- The Internet is a constantly expanding virtual library with over a million terabytes of data and information to be found and millions more gigabytes added daily.

- The Internet can provide you with a variety of sources including: scholarly databases and journals, online encyclopedias, books, and videos.

- Even social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook can provide you with unique and comprehensive sources of citizen journalism.

Key Terms

- peer review

-