3.1: The Histogram

3.1.1: Cross Tabulation

Cross tabulation (or crosstabs for short) is a statistical process that summarizes categorical data to create a contingency table.

Learning Objective

Demonstrate how cross tabulation provides a basic picture of the interrelation between two variables and helps to find interactions between them.

Key Points

- Crosstabs are heavily used in survey research, business intelligence, engineering, and scientific research.

- Crosstabs provide a basic picture of the interrelation between two variables and can help find interactions between them.

- Most general-purpose statistical software programs are able to produce simple crosstabs.

Key Term

- cross tabulation

-

a presentation of data in a tabular form to aid in identifying a relationship between variables

Cross tabulation (or crosstabs for short) is a statistical process that summarizes categorical data to create a contingency table. It is used heavily in survey research, business intelligence, engineering, and scientific research. Moreover, it provides a basic picture of the interrelation between two variables and can help find interactions between them.

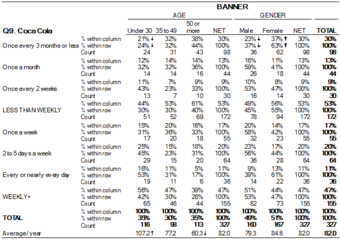

In survey research (e.g., polling, market research), a “crosstab” is any table showing summary statistics. Commonly, crosstabs in survey research are combinations of multiple different tables. For example, combines multiple contingency tables and tables of averages.

Crosstab of Cola Preference by Age and Gender

A crosstab is a combination of various tables showing summary statistics.

Contingency Tables

A contingency table is a type of table in a matrix format that displays the (multivariate) frequency distribution of the variables. A crucial problem of multivariate statistics is finding the direct dependence structure underlying the variables contained in high dimensional contingency tables. If some of the conditional independences are revealed, then even the storage of the data can be done in a smarter way. In order to do this, one can use information theory concepts, which gain the information only from the distribution of probability. Probability can be expressed easily from the contingency table by the relative frequencies.

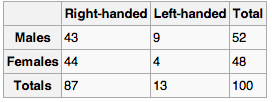

As an example, suppose that we have two variables, sex (male or female) and handedness (right- or left-handed). Further suppose that 100 individuals are randomly sampled from a very large population as part of a study of sex differences in handedness. A contingency table can be created to display the numbers of individuals who are male and right-handed, male and left-handed, female and right-handed, and female and left-handed .

Contingency Table

Contingency table created to display the numbers of individuals who are male and right-handed, male and left-handed, female and right-handed, and female and left-handed.

The numbers of the males, females, and right-and-left-handed individuals are called marginal totals. The grand total–i.e., the total number of individuals represented in the contingency table– is the number in the bottom right corner.

The table allows us to see at a glance that the proportion of men who are right-handed is about the same as the proportion of women who are right-handed, although the proportions are not identical. If the proportions of individuals in the different columns vary significantly between rows (or vice versa), we say that there is a contingency between the two variables. In other words, the two variables are not independent. If there is no contingency, we say that the two variables are independent.

Standard Components of a Crosstab

- Multiple columns – each column refers to a specific sub-group in the population (e.g., men). The columns are sometimes referred to as banner points or cuts (and the rows are sometimes referred to as stubs).

- Significance tests – typically, either column comparisons–which test for differences between columns and display these results using letters– or cell comparisons–which use color or arrows to identify a cell in a table that stands out in some way (as in the example above).

- Nets or netts – which are sub-totals.

- One or more of the following: percentages, row percentages, column percentages, indexes, or averages.

- Unweighted sample sizes (i.e., counts).

Most general-purpose statistical software programs are able to produce simple crosstabs. Creation of the standard crosstabs used in survey research, as shown above, is typically done using specialist crosstab software packages, such as:

- New Age Media Systems (EzTab)

- SAS

- Quantum

- Quanvert

- SPSS Custom Tables

- IBM SPSS Data Collection Model programs

- Uncle

- WinCross

- Q

- SurveyCraft

- BIRT

3.1.2: Drawing a Histogram

To draw a histogram, one must decide how many intervals represent the data, the width of the intervals, and the starting point for the first interval.

Learning Objective

Outline the steps involved in creating a histogram.

Key Points

- There is no “best” number of bars, and different bar sizes may reveal different features of the data.

- A convenient starting point for the first interval is a lower value carried out to one more decimal place than the value with the most decimal places.

- To calculate the width of the intervals, subtract the starting point from the ending value and divide by the number of bars.

Key Term

- histogram

-

a representation of tabulated frequencies, shown as adjacent rectangles, erected over discrete intervals (bins), with an area equal to the frequency of the observations in the interval

To construct a histogram, one must first decide how many bars or intervals (also called classes) are needed to represent the data. Many histograms consist of between 5 and 15 bars, or classes. One must choose a starting point for the first interval, which must be less than the smallest data value. A convenient starting point is a lower value carried out to one more decimal place than the value with the most decimal places.

For example, if the value with the most decimal places is 6.1, and this is the smallest value, a convenient starting point is 6.05 (

). We say that 6.05 has more precision. If the value with the most decimal places is 2.23 and the lowest value is 1.5, a convenient starting point is 1.495 (

). If the value with the most decimal places is 3.234 and the lowest value is 1.0, a convenient starting point is 0.9995 (

). If all the data happen to be integers and the smallest value is 2, then a convenient starting point is 1.5 (

). Also, when the starting point and other boundaries are carried to one additional decimal place, no data value will fall on a boundary.

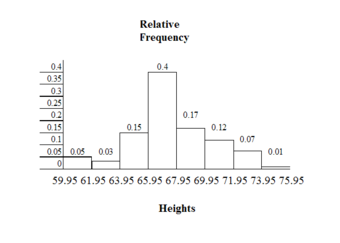

Consider the following data, which are the heights (in inches to the nearest half inch) of 100 male semiprofessional soccer players. The heights are continuous data since height is measured.

60; 60.5; 61; 61; 61.5; 63.5; 63.5; 63.5; 64; 64; 64; 64; 64; 64; 64; 64.5; 64.5; 64.5; 64.5; 64.5; 64.5; 64.5; 64.5; 66; 66; 66; 66; 66; 66; 66; 66; 66; 66; 66.5; 66.5; 66.5; 66.5; 66.5; 66.5; 66.5; 66.5; 66.5; 66.5; 66.5; 67; 67; 67; 67; 67; 67; 67; 67; 67; 67; 67; 67; 67.5; 67.5; 67.5; 67.5; 67.5; 67.5; 67.5; 68; 68; 69; 69; 69; 69; 69; 69; 69; 69; 69; 69; 69.5; 69.5; 69.5; 69.5; 69.5; 70; 70; 70; 70; 70; 70; 70.5; 70.5; 70.5; 71; 71; 71; 72; 72; 72; 72.5; 72.5; 73; 73.5; 74

The smallest data value is 60. Since the data with the most decimal places has one decimal (for instance, 61.5), we want our starting point to have two decimal places. Since the numbers 0.5, 0.05, 0.005, and so on are convenient numbers, use 0.05 and subtract it from 60, the smallest value, for the convenient starting point. The starting point, then, is 59.95.

The largest value is 74.

is the ending value.

Next, calculate the width of each bar or class interval. To calculate this width, subtract the starting point from the ending value and divide by the number of bars (you must choose the number of bars you desire). Note that there is no “best” number of bars, and different bar sizes can reveal different features of the data. Some theoreticians have attempted to determine an optimal number of bars, but these methods generally make strong assumptions about the shape of the distribution. Depending on the actual data distribution and the goals of the analysis, different bar widths may be appropriate, so experimentation is usually needed to determine an appropriate width.

Suppose, in our example, we choose 8 bars. The bar width will be as follows:

We will round up to 2 and make each bar or class interval 2 units wide. Rounding up to 2 is one way to prevent a value from falling on a boundary. The boundaries are:

59.95, 61.95, 63.95, 65.95, 67.95, 69.95, 71.95, 73.95, 75.95

So that there are 2 units between each boundary.

The heights 60 through 61.5 inches are in the interval 59.95 – 61.95. The heights that are 63.5 are in the interval 61.95 – 63.95. The heights that are 64 through 64.5 are in the interval 63.95 – 65.95. The heights 66 through 67.5 are in the interval 65.95 – 67.95. The heights 68 through 69.5 are in the interval 67.95 – 69.95. The heights 70 through 71 are in the interval 69.95 – 71.95. The heights 72 through 73.5 are in the interval 71.95 – 73.95. The height 74 is in the interval 73.95 – 75.95.

displays the heights on the x-axis and relative frequency on the y-axis.

Histogram Example

This histogram depicts the relative frequency of heights for 100 semiprofessional soccer players. Note the roughly normal distribution, with the center of the curve around 66 inches.

3.1.3: Recognizing and Using a Histogram

A histogram is a graphical representation of the distribution of data.

Learning Objective

Indicate how frequency and probability distributions are represented by histograms.

Key Points

- First introduced by Karl Pearson, a histogram is an estimate of the probability distribution of a continuous variable.

- If the distribution of

is continuous, then

is called a continuous random variable and, therefore, has a continuous probability distribution. - An advantage of a histogram is that it can readily display large data sets (a rule of thumb is to use a histogram when the data set consists of 100 values or more).

Key Terms

- frequency

-

number of times an event occurred in an experiment (absolute frequency)

- histogram

-

a representation of tabulated frequencies, shown as adjacent rectangles, erected over discrete intervals (bins), with an area equal to the frequency of the observations in the interval

- probability distribution

-

A function of a discrete random variable yielding the probability that the variable will have a given value.

A histogram is a graphical representation of the distribution of data. More specifically, a histogram is a representation of tabulated frequencies, shown as adjacent rectangles, erected over discrete intervals (bins), with an area equal to the frequency of the observations in the interval. First introduced by Karl Pearson, it is an estimate of the probability distribution of a continuous variable.

A histogram has both a horizontal axis and a vertical axis. The horizontal axis is labeled with what the data represents (for instance, distance from your home to school). The vertical axis is labeled either frequency or relative frequency. The graph will have the same shape with either label. An advantage of a histogram is that it can readily display large data sets (a rule of thumb is to use a histogram when the data set consists of 100 values or more). The histogram can also give you the shape, the center, and the spread of the data.

The categories of a histogram are usually specified as consecutive, non-overlapping intervals of a variable. The categories (intervals) must be adjacent and often are chosen to be of the same size. The rectangles of a histogram are drawn so that they touch each other to indicate that the original variable is continuous.

Frequency and Probability Distributions

In statistical terms, the frequency of an event is the number of times the event occurred in an experiment or study. The relative frequency (or empirical probability) of an event refers to the absolute frequency normalized by the total number of events:

Put more simply, the relative frequency is equal to the frequency for an observed value of the data divided by the total number of data values in the sample.

The height of a rectangle in a histogram is equal to the frequency density of the interval, i.e., the frequency divided by the width of the interval. A histogram may also be normalized displaying relative frequencies. It then shows the proportion of cases that fall into each of several categories, with the total area equaling one.

As mentioned, a histogram is an estimate of the probability distribution of a continuous variable. To define probability distributions for the simplest cases, one needs to distinguish between discrete and continuous random variables. In the discrete case, one can easily assign a probability to each possible value. For example, when throwing a die, each of the six values 1 to 6 has the probability 1/6. In contrast, when a random variable takes values from a continuum, probabilities are nonzero only if they refer to finite intervals. For example, in quality control one might demand that the probability of a “500 g” package containing between 490 g and 510 g should be no less than 98%.

Intuitively, a continuous random variable is the one which can take a continuous range of values — as opposed to a discrete distribution, where the set of possible values for the random variable is, at most, countable. If the distribution of

is continuous, then

is called a continuous random variable and, therefore, has a continuous probability distribution. There are many examples of continuous probability distributions: normal, uniform, chi-squared, and others.

The Histogram

This is an example of a histogram, depicting graphically the distribution of heights for 31 Black Cherry trees.

3.1.4: The Density Scale

Density estimation is the construction of an estimate based on observed data of an unobservable, underlying probability density function.

Learning Objective

Describe how density estimation is used as a tool in the construction of a histogram.

Key Points

- The unobservable density function is thought of as the density according to which a large population is distributed. The data are usually thought of as a random sample from that population.

- A probability density function, or density of a continuous random variable, is a function that describes the relative likelihood for a random variable to take on a given value.

- Kernel density estimates are closely related to histograms, but can be endowed with properties such as smoothness or continuity by using a suitable kernel.

Key Terms

- quartile

-

any of the three points that divide an ordered distribution into four parts, each containing a quarter of the population

- density

-

the probability that an event will occur, as a function of some observed variable

- interquartile range

-

The difference between the first and third quartiles; a robust measure of sample dispersion.

Density Estimation

Histograms are used to plot the density of data, and are often a useful tool for density estimation. Density estimation is the construction of an estimate based on observed data of an unobservable, underlying probability density function. The unobservable density function is thought of as the density according to which a large population is distributed. The data are usually thought of as a random sample from that population.

A probability density function, or density of a continuous random variable, is a function that describes the relative likelihood for this random variable to take on a given value. The probability for the random variable to fall within a particular region is given by the integral of this variable’s density over the region .

Boxplot Versus Probability Density Function

This image shows a boxplot and probability density function of a normal distribution.

The above image depicts a probability density function graph against a box plot. A box plot is a convenient way of graphically depicting groups of numerical data through their quartiles. The spacings between the different parts of the box help indicate the degree of dispersion (spread) and skewness in the data and to identify outliers. In addition to the points themselves, box plots allow one to visually estimate the interquartile range.

A range of data clustering techniques are used as approaches to density estimation, with the most basic form being a rescaled histogram.

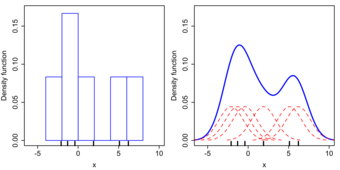

Kernel Density Estimation

Kernel density estimates are closely related to histograms, but can be endowed with properties such as smoothness or continuity by using a suitable kernel. To see this, we compare the construction of histogram and kernel density estimators using these 6 data points:

,

,

,

,

,

For the histogram, first the horizontal axis is divided into sub-intervals, or bins, which cover the range of the data. In this case, we have 6 bins, each having a width of 2. Whenever a data point falls inside this interval, we place a box of height

. If more than one data point falls inside the same bin, we stack the boxes on top of each other .

Histogram Versus Kernel Density Estimation

Comparison of the histogram (left) and kernel density estimate (right) constructed using the same data. The 6 individual kernels are the red dashed curves, the kernel density estimate the blue curves. The data points are the rug plot on the horizontal axis.

For the kernel density estimate, we place a normal kernel with variance 2.25 (indicated by the red dashed lines) on each of the data points

. The kernels are summed to make the kernel density estimate (the solid blue curve). Kernel density estimates converge faster to the true underlying density for continuous random variables thus accounting for their smoothness compared to the discreteness of the histogram.

3.1.5: Types of Variables

A variable is any characteristic, number, or quantity that can be measured or counted.

Learning Objective

Distinguish between quantitative and categorical, continuous and discrete, and ordinal and nominal variables.

Key Points

- Numeric (quantitative) variables have values that describe a measurable quantity as a number, like “how many” or “how much”.

- A continuous variable is an observation that can take any value between a certain set of real numbers.

- A discrete variable is an observation that can take a value based on a count from a set of distinct whole values.

- Categorical variables have values that describe a “quality” or “characteristic” of a data unit, like “what type” or “which category”.

- An ordinal variable is an observation that can take a value that can be logically ordered or ranked.

- A nominal variable is an observation that can take a value that is not able to be organized in a logical sequence.

Key Terms

- continuous variable

-

a variable that has a continuous distribution function, such as temperature

- discrete variable

-

a variable that takes values from a finite or countable set, such as the number of legs of an animal

- variable

-

a quantity that may assume any one of a set of values

What Is a Variable?

A variable is any characteristic, number, or quantity that can be measured or counted. A variable may also be called a data item. Age, sex, business income and expenses, country of birth, capital expenditure, class grades, eye colour and vehicle type are examples of variables. Variables are so-named because their value may vary between data units in a population and may change in value over time.

What Are the Types of Variables?

There are different ways variables can be described according to the ways they can be studied, measured, and presented. Numeric variables have values that describe a measurable quantity as a number, like “how many” or “how much. ” Therefore, numeric variables are quantitative variables.

Numeric variables may be further described as either continuous or discrete. A continuous variable is a numeric variable. Observations can take any value between a certain set of real numbers. The value given to an observation for a continuous variable can include values as small as the instrument of measurement allows. Examples of continuous variables include height, time, age, and temperature.

A discrete variable is a numeric variable. Observations can take a value based on a count from a set of distinct whole values. A discrete variable cannot take the value of a fraction between one value and the next closest value. Examples of discrete variables include the number of registered cars, number of business locations, and number of children in a family, all of of which measured as whole units (i.e., 1, 2, 3 cars).

Categorical variables have values that describe a “quality” or “characteristic” of a data unit, like “what type” or “which category. ” Categorical variables fall into mutually exclusive (in one category or in another) and exhaustive (include all possible options) categories. Therefore, categorical variables are qualitative variables and tend to be represented by a non-numeric value.

Categorical variables may be further described as ordinal or nominal. An ordinal variable is a categorical variable. Observations can take a value that can be logically ordered or ranked. The categories associated with ordinal variables can be ranked higher or lower than another, but do not necessarily establish a numeric difference between each category. Examples of ordinal categorical variables include academic grades (i.e., A, B, C), clothing size (i.e., small, medium, large, extra large) and attitudes (i.e., strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree).

A nominal variable is a categorical variable. Observations can take a value that is not able to be organized in a logical sequence. Examples of nominal categorical variables include sex, business type, eye colour, religion and brand.

Types of Variables

Variables can be numeric or categorial, being further broken down in continuous and discrete, and nominal and ordinal variables.

3.1.6: Controlling for a Variable

Controlling for a variable is a method to reduce the effect of extraneous variations that may also affect the value of the dependent variable.

Learning Objective

Discuss how controlling for a variable leads to more reliable visualizations of probability distributions.

Key Points

- Variables refer to measurable attributes, as these typically vary over time or between individuals.

- Temperature is an example of a continuous variable, while the number of legs of an animal is an example of a discrete variable.

- In causal models, a distinction is made between “independent variables” and “dependent variables,” the latter being expected to vary in value in response to changes in the former.

- While independent variables can refer to quantities and qualities that are under experimental control, they can also include extraneous factors that influence results in a confusing or undesired manner.

- The essence of controlling is to ensure that comparisons between the control group and the experimental group are only made for groups or subgroups for which the variable to be controlled has the same statistical distribution.

Key Terms

- correlation

-

One of the several measures of the linear statistical relationship between two random variables, indicating both the strength and direction of the relationship.

- control

-

a separate group or subject in an experiment against which the results are compared where the primary variable is low or nonexistence

- variable

-

a quantity that may assume any one of a set of values

Histograms help us to visualize the distribution of data and estimate the probability distribution of a continuous variable. In order for us to create reliable visualizations of these distributions, we must be able to procure reliable results for the data during experimentation. A method that significantly contributes to our success in this matter is the controlling of variables.

Defining Variables

In statistics, variables refer to measurable attributes, as these typically vary over time or between individuals. Variables can be discrete (taking values from a finite or countable set), continuous (having a continuous distribution function), or neither. For instance, temperature is a continuous variable, while the number of legs of an animal is a discrete variable.

In causal models, a distinction is made between “independent variables” and “dependent variables,” the latter being expected to vary in value in response to changes in the former. In other words, an independent variable is presumed to potentially affect a dependent one. In experiments, independent variables include factors that can be altered or chosen by the researcher independent of other factors.

There are also quasi-independent variables, which are used by researchers to group things without affecting the variable itself. For example, to separate people into groups by their sex does not change whether they are male or female. Also, a researcher may separate people, arbitrarily, on the amount of coffee they drank before beginning an experiment.

While independent variables can refer to quantities and qualities that are under experimental control, they can also include extraneous factors that influence results in a confusing or undesired manner. In statistics the technique to work this out is called correlation.

Controlling Variables

In a scientific experiment measuring the effect of one or more independent variables on a dependent variable, controlling for a variable is a method of reducing the confounding effect of variations in a third variable that may also affect the value of the dependent variable. For example, in an experiment to determine the effect of nutrition (the independent variable) on organism growth (the dependent variable), the age of the organism (the third variable) needs to be controlled for, since the effect may also depend on the age of an individual organism.

The essence of the method is to ensure that comparisons between the control group and the experimental group are only made for groups or subgroups for which the variable to be controlled has the same statistical distribution. A common way to achieve this is to partition the groups into subgroups whose members have (nearly) the same value for the controlled variable.

Controlling for a variable is also a term used in statistical data analysis when inferences may need to be made for the relationships within one set of variables, given that some of these relationships may spuriously reflect relationships to variables in another set. This is broadly equivalent to conditioning on the variables in the second set. Such analyses may be described as “controlling for variable

” or “controlling for the variations in

“. Controlling, in this sense, is performed by including in the experiment not only the explanatory variables of interest but also the extraneous variables. The failure to do so results in omitted-variable bias.

Controlling for Variables

Controlling is very important in experimentation to ensure reliable results. For example, in an experiment to see which type of vinegar displays the greatest reaction to baking soda, the brand of baking soda should be controlled.

3.1.7: Selective Breeding

Selective breeding is a field concerned with testing hypotheses and theories of evolution by using controlled experiments.

Learning Objective

Illustrate how controlled experiments have allowed human beings to selectively breed domesticated plants and animals.

Key Points

- Unwittingly, humans have carried out evolution experiments for as long as they have been domesticating plants and animals.

- More recently, evolutionary biologists have realized that the key to successful experimentation lies in extensive parallel replication of evolving lineages as well as a larger number of generations of selection.

- Because of the large number of generations required for adaptation to occur, evolution experiments are typically carried out with microorganisms such as bacteria, yeast, or viruses.

Key Terms

- breeding

-

the process through which propagation, growth, or development occurs

- evolution

-

a gradual directional change, especially one leading to a more advanced or complex form; growth; development

- stochastic

-

random; randomly determined

Experimental Evolution and Selective Breeding

Experimental evolution is a field in evolutionary and experimental biology that is concerned with testing hypotheses and theories of evolution by using controlled experiments. Evolution may be observed in the laboratory as populations adapt to new environmental conditions and/or change by such stochastic processes as random genetic drift.

With modern molecular tools, it is possible to pinpoint the mutations that selection acts upon, what brought about the adaptations, and to find out how exactly these mutations work. Because of the large number of generations required for adaptation to occur, evolution experiments are typically carried out with microorganisms such as bacteria, yeast, or viruses.

History of Selective Breeding

Unwittingly, humans have carried out evolution experiments for as long as they have been domesticating plants and animals. Selective breeding of plants and animals has led to varieties that differ dramatically from their original wild-type ancestors. Examples are the cabbage varieties, maize, or the large number of different dog breeds .

Selective Breeding

This Chihuahua mix and Great Dane show the wide range of dog breed sizes created using artificial selection, or selective breeding.

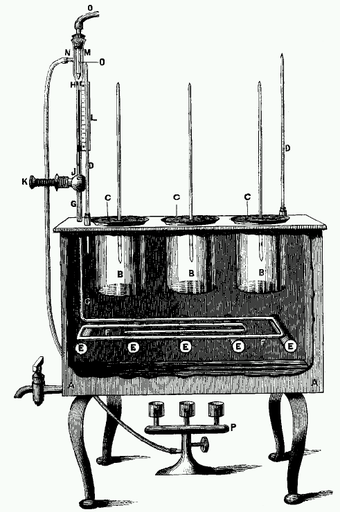

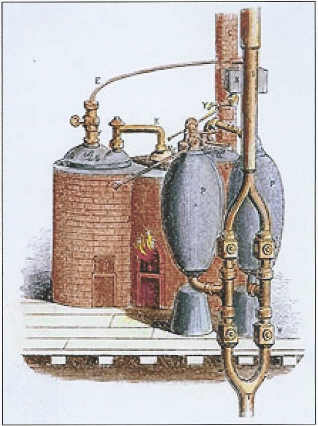

One of the first to carry out a controlled evolution experiment was William Dallinger. In the late 19th century, he cultivated small unicellular organisms in a custom-built incubator over a time period of seven years (1880–1886). Dallinger slowly increased the temperature of the incubator from an initial 60 °F up to 158 °F. The early cultures had shown clear signs of distress at a temperature of 73 °F, and were certainly not capable of surviving at 158 °F. The organisms Dallinger had in his incubator at the end of the experiment, on the other hand, were perfectly fine at 158 °F. However, these organisms would no longer grow at the initial 60 °F. Dallinger concluded that he had found evidence for Darwinian adaptation in his incubator, and that the organisms had adapted to live in a high-temperature environment .

Dallinger Incubator

Drawing of the incubator used by Dallinger in his evolution experiments.

More recently, evolutionary biologists have realized that the key to successful experimentation lies in extensive parallel replication of evolving lineages as well as a larger number of generations of selection. For example, on February 15, 1988, Richard Lenski started a long-term evolution experiment with the bacterium E. coli. The experiment continues to this day, and is by now probably the largest controlled evolution experiment ever undertaken. Since the inception of the experiment, the bacteria have grown for more than 50,000 generations.

3.2: Graphing Data

3.2.1: Statistical Graphics

Statistical graphics allow results to be displayed in some sort of pictorial form and include scatter plots, histograms, and box plots.

Learning Objective

Recognize the techniques used in exploratory data analysis

Key Points

- Graphical statistical methods explore the content of a data set.

- Graphical statistical methods are used to find structure in data.

- Graphical statistical methods check assumptions in statistical models.

- Graphical statistical methods communicate the results of an analysis.

- Graphical statistical methods communicate the results of an analysis.

Key Terms

- histogram

-

a representation of tabulated frequencies, shown as adjacent rectangles, erected over discrete intervals (bins), with an area equal to the frequency of the observations in the interval

- scatter plot

-

A type of display using Cartesian coordinates to display values for two variables for a set of data.

- box plot

-

A graphical summary of a numerical data sample through five statistics: median, lower quartile, upper quartile, and some indication of more extreme upper and lower values.

Statistical graphics are used to visualize quantitative data. Whereas statistics and data analysis procedures generally yield their output in numeric or tabular form, graphical techniques allow such results to be displayed in some sort of pictorial form. They include plots such as scatter plots , histograms, probability plots, residual plots, box plots, block plots and bi-plots.

An example of a scatter plot

A scatter plot helps identify the type of relationship (if any) between two variables.

Exploratory data analysis (EDA) relies heavily on such techniques. They can also provide insight into a data set to help with testing assumptions, model selection and regression model validation, estimator selection, relationship identification, factor effect determination, and outlier detection. In addition, the choice of appropriate statistical graphics can provide a convincing means of communicating the underlying message that is present in the data to others.

Graphical statistical methods have four objectives:

• The exploration of the content of a data set

• The use to find structure in data

• Checking assumptions in statistical models

• Communicate the results of an analysis.

If one is not using statistical graphics, then one is forfeiting insight into one or more aspects of the underlying structure of the data.

Statistical graphics have been central to the development of science and date to the earliest attempts to analyse data. Many familiar forms, including bivariate plots, statistical maps, bar charts, and coordinate paper were used in the 18th century. Statistical graphics developed through attention to four problems:

• Spatial organization in the 17th and 18th century

• Discrete comparison in the 18th and early 19th century

• Continuous distribution in the 19th century and

• Multivariate distribution and correlation in the late 19th and 20th century.

Since the 1970s statistical graphics have been re-emerging as an important analytic tool with the revitalisation of computer graphics and related technologies.

3.2.2: Stem-and-Leaf Displays

A stem-and-leaf display presents quantitative data in a graphical format to assist in visualizing the shape of a distribution.

Learning Objective

Construct a stem-and-leaf display

Key Points

- Stem-and-leaf displays are useful for displaying the relative density and shape of the data, giving the reader a quick overview of distribution.

- They retain (most of) the raw numerical data, often with perfect integrity. They are also useful for highlighting outliers and finding the mode.

- With very small data sets, a stem-and-leaf displays can be of little use, as a reasonable number of data points are required to establish definitive distribution properties.

- With very large data sets, a stem-and-leaf display will become very cluttered, since each data point must be represented numerically.

Key Terms

- outlier

-

a value in a statistical sample which does not fit a pattern that describes most other data points; specifically, a value that lies 1.5 IQR beyond the upper or lower quartile

- stemplot

-

a means of displaying data used especially in exploratory data analysis; another name for stem-and-leaf display

- histogram

-

a representation of tabulated frequencies, shown as adjacent rectangles, erected over discrete intervals (bins), with an area equal to the frequency of the observations in the interval

A stem-and-leaf display is a device for presenting quantitative data in a graphical format in order to assist in visualizing the shape of a distribution. This graphical technique evolved from Arthur Bowley’s work in the early 1900s, and it is a useful tool in exploratory data analysis. A stem-and-leaf display is often called a stemplot (although, the latter term more specifically refers to another chart type).

Stem-and-leaf displays became more commonly used in the 1980s after the publication of John Tukey ‘s book on exploratory data analysis in 1977. The popularity during those years is attributable to the use of monospaced (typewriter) typestyles that allowed computer technology of the time to easily produce the graphics. However, the superior graphic capabilities of modern computers have lead to the decline of stem-and-leaf displays.

While similar to histograms, stem-and-leaf displays differ in that they retain the original data to at least two significant digits and put the data in order, thereby easing the move to order-based inference and non-parametric statistics.

Construction of Stem-and-Leaf Displays

A basic stem-and-leaf display contains two columns separated by a vertical line. The left column contains the stems and the right column contains the leaves. To construct a stem-and-leaf display, the observations must first be sorted in ascending order. This can be done most easily, if working by hand, by constructing a draft of the stem-and-leaf display with the leaves unsorted, then sorting the leaves to produce the final stem-and-leaf display. Consider the following set of data values:

It must be determined what the stems will represent and what the leaves will represent. Typically, the leaf contains the last digit of the number and the stem contains all of the other digits. In the case of very large numbers, the data values may be rounded to a particular place value (such as the hundreds place) that will be used for the leaves. The remaining digits to the left of the rounded place value are used as the stem. In this example, the leaf represents the ones place and the stem will represent the rest of the number (tens place and higher).

The stem-and-leaf display is drawn with two columns separated by a vertical line. The stems are listed to the left of the vertical line. It is important that each stem is listed only once and that no numbers are skipped, even if it means that some stems have no leaves. The leaves are listed in increasing order in a row to the right of each stem. Note that when there is a repeated number in the data (such as two values of

) then the plot must reflect such. Therefore, the plot would appear as

when it has the numbers

). The display for our data would be as follows:

Now, let’s consider a data set with both negative numbers and numbers that need to be rounded:

For negative numbers, a negative is placed in front of the stem unit, which is still the value

. Non-integers are rounded. This allows the stem-and-leaf plot to retain its shape, even for more complicated data sets:

Applications of Stem-and-Leaf Displays

Stem-and-leaf displays are useful for displaying the relative density and shape of data, giving the reader a quick overview of distribution. They retain (most of) the raw numerical data, often with perfect integrity. They are also useful for highlighting outliers and finding the mode.

However, stem-and-leaf displays are only useful for moderately sized data sets (around 15 to 150 data points). With very small data sets, stem-and-leaf displays can be of little use, as a reasonable number of data points are required to establish definitive distribution properties. With very large data sets, a stem-and-leaf display will become very cluttered, since each data point must be represented numerically. A box plot or histogram may become more appropriate as the data size increases.

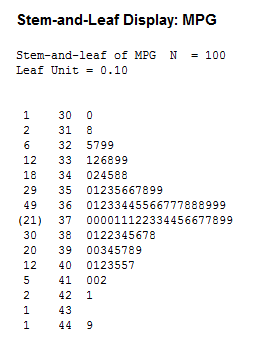

Stem-and-Leaf Display

This is an example of a stem-and-leaf display for EPA data on miles per gallon of gasoline.

3.2.3: Reading Points on a Graph

A graph is a representation of a set of objects where some pairs of the objects are connected by links.

Learning Objective

Distinguish direct and indirect edges

Key Points

- The interconnected objects are represented by mathematical abstractions called vertices.

- The links that connect some pairs of vertices are called edges.

- Vertices are also called nodes or points, and edges are also called lines or arcs.

Key Term

- graph

-

A diagram displaying data; in particular one showing the relationship between two or more quantities, measurements or indicative numbers that may or may not have a specific mathematical formula relating them to each other.

In mathematics, a graph is a representation of a set of objects where some pairs of the objects are connected by links. The interconnected objects are represented by mathematical abstractions called vertices, and the links that connect some pairs of vertices are called edges .Typically, a graph is depicted in diagrammatic form as a set of dots for the vertices, joined by lines or curves for the edges. Graphs are one of the objects of study in discrete mathematics.

The edges may be directed or indirected. For example, if the vertices represent people at a party, and there is an edge between two people if they shake hands, then this is an indirected graph, because if person A shook hands with person B, then person B also shook hands with person A. In contrast, if the vertices represent people at a party, and there is an edge from person A to person B when person A knows of person B, then this graph is directed, because knowledge of someone is not necessarily a symmetric relation (that is, one person knowing another person does not necessarily imply the reverse; for example, many fans may know of a celebrity, but the celebrity is unlikely to know of all their fans). This latter type of graph is called a directed graph and the edges are called directed edges or arcs.Vertices are also called nodes or points, and edges are also called lines or arcs. Graphs are the basic subject studied by graph theory. The word “graph” was first used in this sense by J.J. Sylvester in 1878.

3.2.4: Plotting Points on a Graph

A plot is a graphical technique for representing a data set, usually as a graph showing the relationship between two or more variables.

Learning Objective

Differentiate the different tools used in quantitative and graphical techniques

Key Points

- Graphs are a visual representation of the relationship between variables, very useful because they allow us to quickly derive an understanding which would not come from lists of values.

- Quantitative techniques are the set of statistical procedures that yield numeric or tabular output.

- Examples include hypothesis testing, analysis of variance, point estimates and confidence intervals, and least squares regression.

- There are also many statistical tools generally referred to as graphical techniques, which include: scatter plots, histograms, probability plots, residual plots, box plots, and block plots.

Key Term

- plot

-

a graph or diagram drawn by hand or produced by a mechanical or electronic device

A plot is a graphical technique for representing a data set, usually as a graph showing the relationship between two or more variables. The plot can be drawn by hand or by a mechanical or electronic plotter. Graphs are a visual representation of the relationship between variables, very useful because they allow us to quickly derive an understanding which would not come from lists of values. Graphs can also be used to read off the value of an unknown variable plotted as a function of a known one. Graphs of functions are used in mathematics, sciences, engineering, technology, finance, and many other areas.

Plots play an important role in statistics and data analysis. The procedures here can be broadly split into two parts: quantitative and graphical. Quantitative techniques are the set of statistical procedures that yield numeric or tabular output. Examples of quantitative techniques include:

- hypothesis testing,

- analysis of variance (ANOVA),

- point estimates and confidence intervals, and

- least squares regression.

These and similar techniques are all valuable and are mainstream in terms of classical analysis. There are also many statistical tools generally referred to as graphical techniques. These include:

- scatter plots,

- histograms,

- probability plots,

- residual plots,

- box plots, and

- block plots.

Graphical procedures such as plots are a short path to gaining insight into a data set in terms of testing assumptions, model selection, model validation, estimator selection, relationship identification, factor effect determination, and outlier detection. Statistical graphics give insight into aspects of the underlying structure of the data.

Plotting Points

As an example of plotting points on a graph, consider one of the most important visual aids available to us in the context of statistics: the scatter plot.

To display values for “lung capacity” (first variable) and how long that person could hold his breath, a researcher would choose a group of people to study, then measure each one’s lung capacity (first variable) and how long that person could hold his breath (second variable). The researcher would then plot the data in a scatter plot, assigning “lung capacity” to the horizontal axis, and “time holding breath” to the vertical axis.

A person with a lung capacity of 400 ml who held his breath for 21.7 seconds would be represented by a single dot on the scatter plot at the point

. The scatter plot of all the people in the study would enable the researcher to obtain a visual comparison of the two variables in the data set and will help to determine what kind of relationship there might be between the two variables.

Scatterplot

Scatter plot with a fitted regression line.

3.2.5: Slope and Intercept

The concepts of slope and intercept are essential to understand in the context of graphing data.

Learning Objective

Explain the term rise over run when describing slope

Key Points

- The slope or gradient of a line describes its steepness, incline, or grade — with a higher slope value indicating a steeper incline.

- The slope of a line in the plane containing the

and

axes is generally represented by the letter

, and is defined as the change in the

coordinate divided by the corresponding change in the

coordinate, between two distinct points on the line. - Using the common convention that the horizontal axis represents a variable

and the vertical axis represents a variable

, a

-intercept is a point where the graph of a function or relation intersects with the

-axis of the coordinate system. - Analogously, an

-intercept is a point where the graph of a function or relation intersects with the

-axis.

Key Terms

- intercept

-

the coordinate of the point at which a curve intersects an axis

- slope

-

the ratio of the vertical and horizontal distances between two points on a line; zero if the line is horizontal, undefined if it is vertical.

Slope

The slope or gradient of a line describes its steepness, incline, or grade. A higher slope value indicates a steeper incline. Slope is normally described by the ratio of the “rise” divided by the “run” between two points on a line. The line may be practical (as for a roadway) or in a diagram.

Slope

The slope of a line in the plane is defined as the rise over the run,

.

The slope of a line in the plane containing the x and y axes is generally represented by the letter m, and is defined as the change in the y coordinate divided by the corresponding change in the x coordinate, between two distinct points on the line. This is described by the following equation:

The Greek letter delta,

, is commonly used in mathematics to mean “difference” or “change”. Given two points

and

, the change in

from one to the other is

(run), while the change in

is

(rise).

Intercept

Using the common convention that the horizontal axis represents a variable

and the vertical axis represents a variable

, a

-intercept is a point where the graph of a function or relation intersects with the

-axis of the coordinate system. It also acts as a reference point for slopes and some graphs.

Intercept

Graph with a

-intercept at

.

If the curve in question is given as

, the

-coordinate of the

-intercept is found by calculating

. Functions which are undefined at

have no

-intercept.

Some 2-dimensional mathematical relationships such as circles, ellipses, and hyperbolas can have more than one

-intercept. Because functions associate

values to no more than one

value as part of their definition, they can have at most one

-intercept.

Analogously, an

-intercept is a point where the graph of a function or relation intersects with the

-axis. As such, these points satisfy

. The zeros, or roots, of such a function or relation are the

-coordinates of these

-intercepts.

3.2.6: Plotting Lines

A line graph is a type of chart which displays information as a series of data points connected by straight line segments.

Learning Objective

Explain the principles of plotting a line graph

Key Points

- A line chart is often used to visualize a trend in data over intervals of time – a time series – thus the line is often drawn chronologically.

- A line chart is typically drawn bordered by two perpendicular lines, called axes. The horizontal axis is called the x-axis and the vertical axis is called the y-axis.

- Typically the y-axis represents the dependent variable and the x-axis (sometimes called the abscissa) represents the independent variable.

- In statistics, charts often include an overlaid mathematical function depicting the best-fit trend of the scattered data.

Key Terms

- bell curve

-

In mathematics, the bell-shaped curve that is typical of the normal distribution.

- line

-

a path through two or more points (compare ‘segment’); a continuous mark, including as made by a pen; any path, curved or straight

- gradient

-

of a function y = f(x) or the graph of such a function, the rate of change of y with respect to x, that is, the amount by which y changes for a certain (often unit) change in x

A line graph is a type of chart which displays information as a series of data points connected by straight line segments. It is a basic type of chart common in many fields. It is similar to a scatter plot except that the measurement points are ordered (typically by their x-axis value) and joined with straight line segments. A line chart is often used to visualize a trend in data over intervals of time – a time series – thus the line is often drawn chronologically.

Plotting

A line chart is typically drawn bordered by two perpendicular lines, called axes. The horizontal axis is called the x-axis and the vertical axis is called the y-axis. To aid visual measurement, there may be additional lines drawn parallel either axis. If lines are drawn parallel to both axes, the resulting lattice is called a grid.

Each axis represents one of the data quantities to be plotted. Typically the y-axis represents the dependent variable and the x-axis (sometimes called the abscissa) represents the independent variable. The chart can then be referred to as a graph of quantity one versus quantity two, plotting quantity one up the y-axis and quantity two along the x-axis.

Example

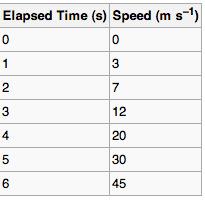

In the experimental sciences, such as statistics, data collected from experiments are often visualized by a graph. For example, if one were to collect data on the speed of a body at certain points in time, one could visualize the data to look like the graph in :

Data Table

A data table showing elapsed time and measured speed.

The table “visualization” is a great way of displaying exact values, but can be a poor way to understand the underlying patterns that those values represent. Understanding the process described by the data in the table is aided by producing a graph or line chart of Speed versus Time:

Line chart

A graph of speed versus time

Best-Fit

In statistics, charts often include an overlaid mathematical function depicting the best-fit trend of the scattered data. This layer is referred to as a best-fit layer and the graph containing this layer is often referred to as a line graph.

It is simple to construct a “best-fit” layer consisting of a set of line segments connecting adjacent data points; however, such a “best-fit” is usually not an ideal representation of the trend of the underlying scatter data for the following reasons:

1. It is highly improbable that the discontinuities in the slope of the best-fit would correspond exactly with the positions of the measurement values.

2. It is highly unlikely that the experimental error in the data is negligible, yet the curve falls exactly through each of the data points.

In either case, the best-fit layer can reveal trends in the data. Further, measurements such as the gradient or the area under the curve can be made visually, leading to more conclusions or results from the data.

A true best-fit layer should depict a continuous mathematical function whose parameters are determined by using a suitable error-minimization scheme, which appropriately weights the error in the data values. Such curve fitting functionality is often found in graphing software or spreadsheets. Best-fit curves may vary from simple linear equations to more complex quadratic, polynomial, exponential, and periodic curves. The so-called “bell curve”, or normal distribution often used in statistics, is a Gaussian function.

3.2.7: The Equation of a Line

In statistics, linear regression can be used to fit a predictive model to an observed data set of

and

values.

Learning Objective

Examine simple linear regression in terms of slope and intercept

Key Points

- Simple linear regression fits a straight line through a set of points that makes the vertical distances between the points of the data set and the fitted line as small as possible.

-

, where

and

designate constants is a common form of a linear equation. - Linear regression can be used to fit a predictive model to an observed data set of

and

values.

Key Term

- linear regression

-

an approach to modeling the relationship between a scalar dependent variable

$y$ and one or more explanatory variables denoted$x$ .

In statistics, simple linear regression is the least squares estimator of a linear regression model with a single explanatory variable. Simple linear regression fits a straight line through the set of

points in such a way that makes the sum of squared residuals of the model (that is, vertical distances between the points of the data set and the fitted line) as small as possible.

The slope of the fitted line is equal to the correlation between

and

corrected by the ratio of standard deviations of these variables. The intercept of the fitted line is such that it passes through the center of mass

of the data points.

The function of a lne

Three lines — the red and blue lines have the same slope, while the red and green ones have same y-intercept.

Linear regression was the first type of regression analysis to be studied rigorously, and to be used extensively in practical applications. This is because models which depend linearly on their unknown parameters are easier to fit than models which are non-linearly related to their parameters and because the statistical properties of the resulting estimators are easier to determine.

A common form of a linear equation in the two variables

and

is:

Where

(slope) and

(intercept) designate constants. The origin of the name “linear” comes from the fact that the set of solutions of such an equation forms a straight line in the plane. In this particular equation, the constant

determines the slope or gradient of that line, and the constant term

determines the point at which the line crosses the

-axis, otherwise known as the

-intercept.

If the goal is prediction, or forecasting, linear regression can be used to fit a predictive model to an observed data set of

and

values. After developing such a model, if an additional value of

is then given without its accompanying value of

, the fitted model can be used to make a prediction of the value of

.

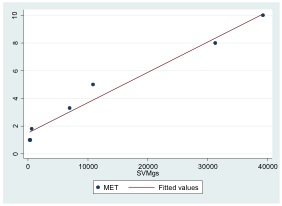

Linear regression

An example of a simple linear regression analysis

Chapter 2: Statistics in Practice

2.1: Observational Studies

2.1.1: What are Observational Studies?

An observational study is one in which no variables can be manipulated or controlled by the investigator.

Learning Objective

Identify situations in which observational studies are necessary and the challenges that arise in their interpretation.

Key Points

- An observational study is in contrast with experiments, such as randomized controlled trials, where each subject is randomly assigned to a treated group or a control group.

- Variables may be uncontrollable because 1) a randomized experiment would violate ethical standards, 2) the investigator may simply lack the requisite influence, or 3) a randomized experiment may be impractical.

- Observational studies can never identify causal relationships because even though two variables are related both might be caused by a third, unseen, variable.

- A major challenge in conducting observational studies is to draw inferences that are acceptably free from influences by overt biases, as well as to assess the influence of potential hidden biases.

- A major challenge in conducting observational studies is to draw inferences that are acceptably free from influences by overt biases, as well as to assess the influence of potential hidden biases.

Key Terms

- causality

-

the relationship between an event (the cause) and a second event (the effect), where the second event is understood as a consequence of the first

- observational study

-

a study drawing inferences about the possible effect of a treatment on subjects, where the assignment of subjects into a treated group versus a control group is outside the control of the investigator

A common goal in statistical research is to investigate causality, which is the relationship between an event (the cause) and a second event (the effect), where the second event is understood as a consequence of the first. There are two major types of causal statistical studies: experimental studies and observational studies. An observational study draws inferences about the possible effect of a treatment on subjects, where the assignment of subjects into a treated group versus a control group is outside the control of the investigator. This is in contrast with experiments, such as randomized controlled trials, where each subject is randomly assigned to a treated group or a control group. In other words, observational studies have no independent variables — nothing is manipulated by the experimenter. Rather, observations have the equivalent of two dependent variables.

In an observational study, the assignment of treatments may be beyond the control of the investigator for a variety of reasons:

- A randomized experiment would violate ethical standards: Suppose one wanted to investigate the abortion – breast cancer hypothesis, which postulates a causal link between induced abortion and the incidence of breast cancer. In a hypothetical controlled experiment, one would start with a large subject pool of pregnant women and divide them randomly into a treatment group (receiving induced abortions) and a control group (bearing children), and then conduct regular cancer screenings for women from both groups. Needless to say, such an experiment would run counter to common ethical principles. The published studies investigating the abortion–breast cancer hypothesis generally start with a group of women who already have received abortions. Membership in this “treated” group is not controlled by the investigator: the group is formed after the “treatment” has been assigned.

- The investigator may simply lack the requisite influence: Suppose a scientist wants to study the public health effects of a community-wide ban on smoking in public indoor areas. In a controlled experiment, the investigator would randomly pick a set of communities to be in the treatment group. However, it is typically up to each community and/or its legislature to enact a smoking ban. The investigator can be expected to lack the political power to cause precisely those communities in the randomly selected treatment group to pass a smoking ban. In an observational study, the investigator would typically start with a treatment group consisting of those communities where a smoking ban is already in effect.

- A randomized experiment may be impractical: Suppose a researcher wants to study the suspected link between a certain medication and a very rare group of symptoms arising as a side effect. Setting aside any ethical considerations, a randomized experiment would be impractical because of the rarity of the effect. There may not be a subject pool large enough for the symptoms to be observed in at least one treated subject. An observational study would typically start with a group of symptomatic subjects and work backwards to find those who were given the medication and later developed the symptoms

Usefulness and Reliability of Observational Studies

Observational studies can never identify causal relationships because even though two variables are related both might be caused by a third, unseen, variable. Since the underlying laws of nature are assumed to be causal laws, observational findings are generally regarded as less compelling than experimental findings.

Observational studies can, however:

- Provide information on “real world” use and practice

- Detect signals about the benefits and risks of the use of practices in the general population

- Help formulate hypotheses to be tested in subsequent experiments

- Provide part of the community-level data needed to design more informative pragmatic clinical trials

- Inform clinical practice

A major challenge in conducting observational studies is to draw inferences that are acceptably free from influences by overt biases, as well as to assess the influence of potential hidden biases.

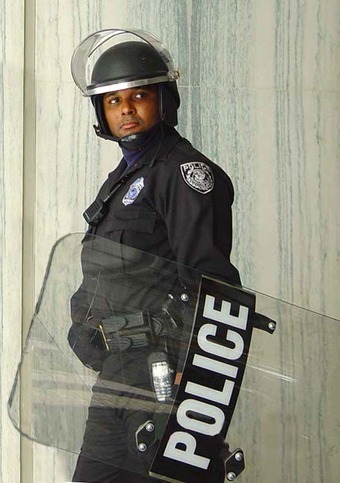

Observational Studies

Nature Observation and Study Hall in The Natural and Cultural Gardens, The Expo Memorial Park, Suita city, Osaka, Japan. Observational studies are a type of experiments in which the variables are outside the control of the investigator.

2.1.2: The Clofibrate Trial

The Clofibrate Trial was a placebo-controlled study to determine the safety and effectiveness of drugs treating coronary heart disease in men.

Learning Objective

Outline how the use of placebos in controlled experiments leads to more reliable results.

Key Points

- Clofibrate was one of four lipid-modifying drugs tested in an observational study known as the Coronary Drug Project.

- Placebo-controlled studies are a way of testing a medical therapy in which, in addition to a group of subjects that receives the treatment to be evaluated, a separate control group receives a sham “placebo” treatment which is specifically designed to have no real effect.

- The purpose of the placebo group is to account for the placebo effect — that is, effects from treatment that do not depend on the treatment itself.

- Appropriate use of a placebo in a clinical trial often requires, or at least benefits from, a double-blind study design, which means that neither the experimenters nor the subjects know which subjects are in the “test group” and which are in the “control group. “.

- The use of placebos is a standard control component of most clinical trials which attempt to make some sort of quantitative assessment of the efficacy of medicinal drugs or treatments.

Key Terms

- regression to the mean

-

the phenomenon by which extreme examples from any set of data are likely to be followed by examples which are less extreme; a tendency towards the average of any sample

- placebo

-

an inactive substance or preparation used as a control in an experiment or test to determine the effectiveness of a medicinal drug

- placebo effect

-

the tendency of any medication or treatment, even an inert or ineffective one, to exhibit results simply because the recipient believes that it will work

Clofibrate (tradename Atromid-S) is an organic compound that is marketed as a fibrate. It is a lipid-lowering agent used for controlling the high cholesterol and triacylglyceride level in the blood. Clofibrate was one of four lipid-modifying drugs tested in an observational study known as the Coronary Drug Project. Also known as the World Health Organization Cooperative Trial on Primary Prevention of Ischaemic Heart Disease, the study was a randomized, multi-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that was intended to study the safety and effectiveness of drugs for long-term treatment of coronary heart disease in men.

Placebo-Controlled Observational Studies

Placebo-controlled studies are a way of testing a medical therapy in which, in addition to a group of subjects that receives the treatment to be evaluated, a separate control group receives a sham “placebo” treatment which is specifically designed to have no real effect. Placebos are most commonly used in blinded trials, where subjects do not know whether they are receiving real or placebo treatment.

The purpose of the placebo group is to account for the placebo effect — that is, effects from treatment that do not depend on the treatment itself. Such factors include knowing one is receiving a treatment, attention from health care professionals, and the expectations of a treatment’s effectiveness by those running the research study. Without a placebo group to compare against, it is not possible to know whether the treatment itself had any effect.

Appropriate use of a placebo in a clinical trial often requires, or at least benefits from, a double-blind study design, which means that neither the experimenters nor the subjects know which subjects are in the “test group” and which are in the “control group. ” This creates a problem in creating placebos that can be mistaken for active treatments. Therefore, it can be necessary to use a psychoactive placebo, a drug that produces physiological effects that encourage the belief in the control groups that they have received an active drug.

Patients frequently show improvement even when given a sham or “fake” treatment. Such intentionally inert placebo treatments can take many forms, such as a pill containing only sugar, a surgery where nothing is actually done, or a medical device (such as ultrasound) that is not actually turned on. Also, due to the body’s natural healing ability and statistical effects such as regression to the mean, many patients will get better even when given no treatment at all. Thus, the relevant question when assessing a treatment is not “does the treatment work? ” but “does the treatment work better than a placebo treatment, or no treatment at all? “

Therefore, the use of placebos is a standard control component of most clinical trials which attempt to make some sort of quantitative assessment of the efficacy of medicinal drugs or treatments.

Results of The Coronary Drug Project

Those in the placebo group who adhered to the placebo treatment (took the placebo regularly as instructed) showed nearly half the mortality rate as those who were not adherent. A similar study of women found survival was nearly 2.5 times greater for those who adhered to their placebo. This apparent placebo effect may have occurred because:

- Adhering to the protocol had a psychological effect, i.e. genuine placebo effect.

- People who were already healthier were more able or more inclined to follow the protocol.

- Compliant people were more diligent and health-conscious in all aspects of their lives.

The Coronary Drug Project found that subjects using clofibrate to lower serum cholesterol observed excess mortality in the clofibrate-treated group despite successful cholesterol lowering (47% more deaths during treatment with clofibrate and 5% after treatment with clofibrate) than the non-treated high cholesterol group. These deaths were due to a wide variety of causes other than heart disease, and remain “unexplained”.

Clofibrate was discontinued in 2002 due to adverse affects.

Placebo-Controlled Observational Studies

Prescription placebos used in research and practice.

2.1.3: Confounding

A confounding variable is an extraneous variable in a statistical model that correlates with both the dependent variable and the independent variable.

Learning Objective

Break down why confounding variables may lead to bias and spurious relationships and what can be done to avoid these phenomenons.

Key Points

- A perceived relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable that has been misestimated due to the failure to account for a confounding factor is termed a spurious relationship.

- Confounding by indication – the most important limitation of observational studies – occurs when prognostic factors cause bias, such as biased estimates of treatment effects in medical trials.

- Confounding variables may also be categorised according to their source: such as operational confounds, procedural confounds or person confounds.

- A reduction in the potential for the occurrence and effect of confounding factors can be obtained by increasing the types and numbers of comparisons performed in an analysis.

- Moreover, depending on the type of study design in place, there are various ways to modify that design to actively exclude or control confounding variables.

Key Terms

- peer review

-

the scholarly process whereby manuscripts intended to be published in an academic journal are reviewed by independent researchers (referees) to evaluate the contribution, i.e. the importance, novelty and accuracy of the manuscript’s contents

- placebo effect

-

the tendency of any medication or treatment, even an inert or ineffective one, to exhibit results simply because the recipient believes that it will work

- prognostic

-

a sign by which a future event may be known or foretold

- confounding variable

-

an extraneous variable in a statistical model that correlates (positively or negatively) with both the dependent variable and the independent variable

Example

- In risk assessments, factors such as age, gender, and educational levels often have impact on health status and so should be controlled. Beyond these factors, researchers may not consider or have access to data on other causal factors. An example is on the study of smoking tobacco on human health. Smoking, drinking alcohol, and diet are lifestyle activities that are related. A risk assessment that looks at the effects of smoking but does not control for alcohol consumption or diet may overestimate the risk of smoking. Smoking and confounding are reviewed in occupational risk assessments such as the safety of coal mining. When there is not a large sample population of non-smokers or non-drinkers in a particular occupation, the risk assessment may be biased towards finding a negative effect on health.

Confounding Variables

A confounding variable is an extraneous variable in a statistical model that correlates (positively or negatively) with both the dependent variable and the independent variable. A perceived relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable that has been misestimated due to the failure to account for a confounding factor is termed a spurious relationship, and the presence of misestimation for this reason is termed omitted-variable bias.

As an example, suppose that there is a statistical relationship between ice cream consumption and number of drowning deaths for a given period. These two variables have a positive correlation with each other. An individual might attempt to explain this correlation by inferring a causal relationship between the two variables (either that ice cream causes drowning, or that drowning causes ice cream consumption). However, a more likely explanation is that the relationship between ice cream consumption and drowning is spurious and that a third, confounding, variable (the season) influences both variables: during the summer, warmer temperatures lead to increased ice cream consumption as well as more people swimming and, thus, more drowning deaths.

Types of Confounding

Confounding by indication has been described as the most important limitation of observational studies. Confounding by indication occurs when prognostic factors cause bias, such as biased estimates of treatment effects in medical trials. Controlling for known prognostic factors may reduce this problem, but it is always possible that a forgotten or unknown factor was not included or that factors interact complexly. Randomized trials tend to reduce the effects of confounding by indication due to random assignment.

Confounding variables may also be categorised according to their source:

- The choice of measurement instrument (operational confound) – This type of confound occurs when a measure designed to assess a particular construct inadvertently measures something else as well.

- Situational characteristics (procedural confound) – This type of confound occurs when the researcher mistakenly allows another variable to change along with the manipulated independent variable.

- Inter-individual differences (person confound) – This type of confound occurs when two or more groups of units are analyzed together (e.g., workers from different occupations) despite varying according to one or more other (observed or unobserved) characteristics (e.g., gender).

Decreasing the Potential for Confounding

A reduction in the potential for the occurrence and effect of confounding factors can be obtained by increasing the types and numbers of comparisons performed in an analysis. If a relationship holds among different subgroups of analyzed units, confounding may be less likely. That said, if measures or manipulations of core constructs are confounded (i.e., operational or procedural confounds exist), subgroup analysis may not reveal problems in the analysis.

Peer review is a process that can assist in reducing instances of confounding, either before study implementation or after analysis has occurred. Similarly, study replication can test for the robustness of findings from one study under alternative testing conditions or alternative analyses (e.g., controlling for potential confounds not identified in the initial study). Also, confounding effects may be less likely to occur and act similarly at multiple times and locations.

Moreover, depending on the type of study design in place, there are various ways to modify that design to actively exclude or control confounding variables:

- Case-control studies assign confounders to both groups, cases and controls, equally. In case-control studies, matched variables most often are age and sex.

- In cohort studies, a degree of matching is also possible, and it is often done by only admitting certain age groups or a certain sex into the study population. this creates a cohort of people who share similar characteristics; thus, all cohorts are comparable in regard to the possible confounding variable.

- Double blinding conceals the experiment group membership of the participants from the trial population and the observers. By preventing the participants from knowing if they are receiving treatment or not, the placebo effect should be the same for the control and treatment groups. By preventing the observers from knowing of their membership, there should be no bias from researchers treating the groups differently or from interpreting the outcomes differently.

- A randomized controlled trial is a method where the study population is divided randomly in order to mitigate the chances of self-selection by participants or bias by the study designers. Before the experiment begins, the testers will assign the members of the participant pool to their groups (control, intervention, parallel) using a randomization process such as the use of a random number generator.

2.1.4: Sex Bias in Graduate Admissions

The Berkeley study is one of the best known real life examples of an experiment suffering from a confounding variable.

Learning Objective

Illustrate how the phenomenon of confounding can be seen in practice via Simpson’s Paradox.

Key Points

- A study conducted in the aftermath of a law suit filed against the University of California, Berkeley showed that men applying were more likely than women to be admitted.

- Examination of the aggregate data on admissions showed a blatant, if easily misunderstood, pattern of gender discrimination against applicants.