35.1: Communist China

35.1.1: The Republic of China

Throughout its short existence, the Republic of China (1912-1949)

experienced a nearly continuous power struggle. The eventual war between the nationalists and the communists ended with the Nationalist government retreating to

Taiwan and the communists taking control of the mainland China and establishing the

People’s Republic of China.

Learning Objective

Outline the successes and failures of the Republic of China during its decades in power.

Key Points

-

The

Republic of China was a state in East Asia that existed from 1912 to

1949. It largely occupied the present-day territories of China, Taiwan, and,

for some of its history, Mongolia. As an era of Chinese history, it was

preceded by the last imperial dynasty of China and the Qing dynasty, and ended

with the Chinese Civil War. -

The

Republican Era of China began with the outbreak of revolution on October 10,

1911, in Wuchang among discontented modernized army units whose anti-Qing plot

was uncovered. This would become known as the Wuchang Uprising, celebrated as Double Tenth Day in Taiwan. It was preceded by numerous

abortive uprisings and organized protests in China. -

After a power struggle, on March 10, 1912, in Beijing, Yuan Shikai was sworn in as the second provisional president of the Republic of China. Yuan proceeded to abolish the national and provincial assemblies and declared himself emperor in late 1915, but his imperial ambitions were fiercely opposed by his subordinates. Faced with the prospect of rebellion, he abdicated in 1916 and died the same year. His death left a power vacuum in China and ushered in what would become known as the Warlord Era, during which much of the country was ruled by shifting coalitions of competing provincial military leaders.

-

During the Nanjing Decade of 1928-37, which followed the Warlord Era, the Nationalists under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek attempted to consolidate the divided society and reform the economy. The KMT was criticized as instituting totalitarianism, but claimed it was attempting to establish a modern democratic society.

-

The

bitter struggle between the KMT and the CPC continued, openly or clandestinely,

through the 14-year-long Japanese occupation of various parts of the country

(1931–1945). The two Chinese parties nominally formed a united front to oppose

the Japanese in 1937, during the Second Sino-Japanese

War (1937–1945), which became part of World War II. - Following the

defeat of Japan in 1945, the war between the Nationalist forces and the CPC

resumed after failed attempts at reconciliation and a negotiated settlement. By

1949, the CPC had established control over most of the country. When the

Nationalist government forces were defeated by CPC forces in mainland China in

1949, the Nationalist government retreated to Taiwan along with

Chiang and most of the KMT leadership, and a large number of their supporters.

Key Terms

- Nanjing Decade

-

An informal name for the decade from 1927 (or 1928) to 1937 in the Republic of China. The period began when Nationalist Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek took Nanjing from Zhili clique warlord Sun Chuanfang halfway through the Northern Expedition in 1927. Chiang declared it the national capital despite the left-wing Nationalist government in Wuhan.

- Kuomintang

-

A major political party in the Republic of China, currently the second-largest in the country,

often translated as the Nationalist Party of China or Chinese Nationalist Party. Its predecessor, the Revolutionary Alliance, was one of the major advocates of the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty and the establishment of a republic. The party was founded by Song Jiaoren and Sun Yat-sen shortly after the Xinhai Revolution of 1911. - Beiyang Government

-

The government of the Republic of China, in place in the capital city of Beijing from 1912 to 1928. It was internationally recognized as the legitimate Chinese government but lacked domestic legitimacy.

- Northern Expedition

-

A 1926-1928 military campaign led by Chiang Kai-shek. Its main objective was to unify China, ending the rule of the Beiyang government and that of the local warlords. It led to the end of the Warlord Era, the reunification of China in 1928, and the establishment of the Nanjing government.

- Warlord Era

-

In the history of the Republic of China, the period when the control of the country was divided among its military cliques in the mainland regions. The era lasted from the death of Yuan Shikai in 1916 until 1928.

- Wuchang Uprising

-

The Chinese uprising that served as the catalyst to the Xinhai Revolution, ending the Qing Dynasty – and two millennia of imperial rule – and ushering in the Republic of China (ROC). It began with the dissatisfaction of the handling of a railway crisis, which escalated to an uprising in which the revolutionaries went up against Qing government officials.

The Republic of

China was a state in East Asia that existed from 1912 to 1949. It

largely occupied the present-day territories of China, Taiwan, and, for some of

its history, Mongolia. As an era of Chinese history, it was preceded by the

last imperial dynasty of China, the Qing dynasty, and ended with the Chinese

Civil War. After the war, the losing Kuomintang retreated to the island of

Taiwan to found the modern Republic of China, while the victorious Communist

Party of China established the People’s Republic of China on the

Mainland.

Early Republic

The Republican Era of

China began with the outbreak of revolution on October 10, 1911, in Wuchang

among discontented modernized army units whose anti-Qing plot had been uncovered.

This would be known as the Wuchang Uprising, celebrated as Double

Tenth Day in Taiwan. It was preceded by numerous abortive uprisings and

organized protests in China. The revolt quickly spread to neighboring

cities, and members of underground resistance movement Tongmenghui throughout the country rose in support of the

Wuchang revolutionary forces. After a series of failures of the revolutionary forces, during the 41-day Battle of Yangxia 15 of 24 provinces declared their

independence from the Qing empire. On January 1, 1912, delegates from the

independent provinces elected Sun Yat-sen as the first provisional president

of the Republic of China. The last emperor of China, Puyi, was forced to

abdicate on February 12.

Although Sun was

inaugurated in Nanjing as the first provisional president, power in Beijing

already had passed to Yuan Shikai, who had effective control of the Beiyang

Army, the most powerful military force in China at the time. To prevent civil

war and possible foreign intervention from undermining the infant republic, Sun

agreed to Yuan’s demand for China to be united under Yuan’s Beijing government.

On March 10 in Beijing, Yuan Shikai was sworn in as the second provisional president of the Republic of China.

Although many

political parties were vying for supremacy in the legislature, the revolutionists

lacked an army, and Yuan soon revised the constitution and revealed dictatorial

ambitions. In August 1912, the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party) was founded by

Song Jiaoren, one of Sun’s associates. It was an amalgamation of small political

groups, including Sun’s Tongmenghui. In the national elections held in February

1913 for the new bicameral parliament, Song campaigned against the Yuan

administration and the Kuomintang won a majority of seats.

Over

the next few years, however, Yuan proceeded to abolish the national and

provincial assemblies and declared himself emperor in late 1915, but his imperial

ambitions were fiercely opposed by his subordinates. Faced with the prospect of

rebellion, he abdicated in 1916 and died the same year. His death left a power

vacuum in China and ushered in what would be known as the Warlord

Era, during which much of the country was ruled by shifting coalitions of

competing provincial military leaders.

Yuan Shikai (left) and Sun Yat-sen (right) with flags representing the early republic.

The History of the Republic of China begins after the Qing dynasty in 1912, when the formation of the Republic of China as a constitutional republic put an end to 4,000 years of Imperial rule. The Qing dynasty ruled from 1644–1912. The Republic experienced many trials and tribulations after its founding, including domination by warlord generals and foreign powers.

The Warlord Era

Despite the fact that various warlords gained control of the

government in Beijing during the Warlord Era, a new

form of control or governance did not emerge at the time because other warlords did not acknowledge the

transitory governments of the period. These military-dominated governments were

collectively known as the Beiyang Government. The name derives from the Beiyang

Army, which dominated its politics. Although the government and the state

were nominally under civilian control with a constitution, the Beiyang

generals were effectively in charge, with various factions vying for

power. Although the Beiyang Government’s legitimacy was challenged

domestically, it had international diplomatic recognition and access to the tax and customs revenue, and could apply for foreign

financial loans.

In 1917, China declared war on Germany in the hope of

recovering its lost province, then under Japanese control. On May 4, 1919,

there were massive student demonstrations against the Beijing government and

Japan. The political fervor, student activism, and iconoclastic and reformist

intellectual currents set in motion by the protest developed into a

national awakening known as the May Fourth Movement. The intellectual milieu in

which this movement developed was known as the New Culture Movement. The student

demonstrations of May 4, 1919, were the high point of the New Culture Movement

and the terms are often used as synonyms. Chinese representatives refused to

sign the Treaty of Versailles due to intense

pressure from both the student protesters and public opinion.

The discrediting of liberal Western philosophy among

leftist Chinese intellectuals led to radical lines of thought inspired by

the Russian Revolution and supported by agents of the Comintern sent to China

by Moscow. This created the seeds for the irreconcilable conflict between the

left and right in China that would dominate Chinese history for the rest of the

century.

In the 1920s, Sun Yat-sen established a revolutionary base

in south China and set out to unite the fragmented nation. With assistance

from the Soviet Union, he entered into an alliance with the

fledgling Communist Party of China. After Sun’s

death from cancer in 1925, one of his protégés, Chiang

Kai-shek, seized control of the Kuomintang (Nationalist

Party or KMT) and succeeded in bringing most of south and central China under

its rule in a military campaign known as the Northern Expedition (1926–1927). Having

defeated the warlords in south and central China by military force, Chiang was

able to secure the nominal allegiance of the warlords in the North. In 1927,

Chiang turned on the CPC and chased the CPC armies and its leaders from their

bases in southern and eastern China. In 1934, driven from their mountain bases,

the CPC forces embarked on the Long March across

China’s most desolate terrain to the northwest, where they established a

guerrilla base at Yan’an in Shaanxi Province. During the Long March, the

communists reorganized under a new leader, Mao Zedong (Mao

Tse-tung).

The Nanjing Decade

During the Nanjing Decade of 1928-37, the Nationalists

attempted to consolidate the divided society and reform the economy. The

KMT was criticized for instituting totalitarianism,

but claimed it was attempting to establish a modern democratic society by creating the Academia

Sinica (today’s national academy of Taiwan), the Central Bank of China, and

other agencies. In 1932, China sent its first team to the Olympic Games. Laws

were passed and campaigns mounted to promote the rights of women. Improved

communication also allowed a focus on social problems, including those of the

villages (for example the Rural Reconstruction Movement). Simultaneously,

political freedom was considerably curtailed because of the Kuomintang’s

one-party domination through “political tutelage” and violent shutting

down of anti-government protests.

At the time, a series of massive wars also took place in

western China, including the Kumul

Rebellion, the Sino-Tibetan War, and the Soviet invasion of Xinjiang. Although

the central government was nominally in control of the entire country, large

areas remained under the semi-autonomous rule of local warlords,

provincial military leaders, or warlord coalitions. Nationalist rule was

strongest in the eastern regions around the capital Nanjing, but regional

militarists retained considerable local authority.

The Fall of the Republic and Its Legacy: Taiwan

The bitter struggle between the KMT and the CPC continued,

openly or clandestinely, through the 14-year-long Japanese occupation of

various parts of the country (1931–1945). The two Chinese parties nominally

formed a united front to oppose the Japanese in 1937 during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945),

which became part of World War II. Following the defeat of Japan in 1945, the

war between the Nationalist forces and the CPC resumed after failed attempts at

reconciliation and a negotiated settlement. By 1949, the CPC had established

control over most of the country. When the Nationalist government forces

were defeated by CPC forces in mainland China in 1949, they retreated to Taiwan along with Chiang and most of the KMT leadership

and a large number of their supporters. The Nationalist government had taken

effective control of Taiwan at the end of World War II as part of the overall

Japanese surrender, when Japanese troops in Taiwan surrendered to Republic of

China troops.

Until the early 1970s, the Republic of China was recognized

as the sole legitimate government of China by the United Nations and most

Western nations, refusing to recognize the People’s Republic of China. However,

in 1971, Resolution 2758 was passed by the

UN General Assembly and “the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek” (and

thus the ROC) were expelled from the UN and replaced as “China” by

the PRC. In 1979, the United States switched recognition from Taipei to

Beijing. The KMT ruled Taiwan under martial

law until the late 1980s, with the stated goals of vigilance against Communist infiltration and preparation to retake mainland China.

Therefore, political dissent was not tolerated.

Since the 1990s, the ROC went from one-party rule to a

multi-party system thanks to a series of democratic and governmental reforms

implemented in Taiwan. The first election for provincial

governors and municipality Mayors was in 1994. Taiwan held the first direct presidential election

in 1996.

35.1.2: China in WWII

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) dominated China’s war efforts and although the Republic of China emerged from the war as a member of the victorious Allied forces, the country was ravaged by the economic crisis and continuous conflicts between the Nationalists and the Communists.

Learning Objective

Discuss China’s role as one of the Allied countries during WWII.

Key Points

-

The chaotic internal situation in China and the effort the Chinese government was required to put into the civil wars provided opportunities for Japanese expansionism. Japan saw Manchuria as a source of raw materials, a market for its manufactured goods, and as a protective buffer state against the Soviet Union in Siberia. Japan invaded Manchuria after the 1931 Mukden Incident. With appeasement being the predominant policy of the day, no country was willing to take action against Japan beyond tepid censure. Incessant fighting between Japanese and Chinese forces followed.

-

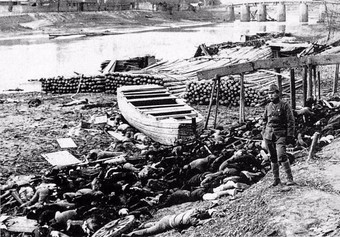

The Chinese resistance stiffened after July 7,

1937, when a clash occurred between Chinese and Japanese troops outside Beijing.

This skirmish led to open, although undeclared, warfare between China and

Japan, which turned into the Second Sino-Japanese War. Shanghai fell after a three-month battle and the capital of Nanking fell in

December 1937, which was followed by the Nanking Massacre. -

The United States and the Soviet Union put an end to the Second Sino-Japanese War by attacking the Japanese with atomic bombs (on America’s part) and an incursion into Manchuria (on the Soviet Union’s part). Japanese Emperor Hirohito officially capitulated to the Allies on August 15, 1945. The Chinese-Japanese conflict lasted for over eight years and its casualties were more than half of total casualties of the Pacific War.

-

During World War II, the United States emerged

as a major player in Chinese affairs. As an ally it embarked in late 1941 on a

program of massive military and financial aid to the hard-pressed Nationalist Government. In 1943, the United States

and Britain led the way in revising their treaties with China, bringing to an

end a century of unequal treaty relations. -

After the end of the war in August 1945, the

Nationalist Government moved back to Nanking. With American help, Nationalist

troops moved to take the Japanese surrender in North China. The Soviet Union,

as part of the Yalta agreement allowing a Soviet sphere of influence in

Manchuria, dismantled and removed more than half the industrial equipment left

there by the Japanese. The Soviet presence in northeast China enabled the

Communists to move in long enough to arm themselves with the equipment

surrendered by the withdrawing Japanese army. -

In 1941, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt devised the name

“United Nations.” He referred to the Big Three and China as a “trusteeship of

the powerful” and then later the “Four

Policemen.” At the Potsdam Conference of 1945, Harry Truman proposed that the foreign

ministers of China, France, the Soviet Union, United Kingdom, and the United

States “should draft the peace treaties and boundary settlements of Europe,”

which led to the creation of the Council of Foreign Ministers of

the “Big Five” and soon thereafter the establishment of those states

as the permanent members of the UN Security Council.

35.1.3: The Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War, fought between forces loyal to the Kuomintang-led government (KMT) and those loyal to the Communist Party of China (CPC),

represented an ideological split between the CPC and the KMT and resulted in the establishment of the People’s Republic of China and the exodus of the nationalists to Taiwan.

Learning Objective

Outline the reasons behind and events of the Chinese Civil War

Key Points

- The Chinese Civil War was fought between forces loyal to the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and those loyal to the Communist Party of China. The war began in 1927 with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s Northern Expedition and ended when major hostilities ceased in 1950. It can generally be divided into two stages separated by the Second Sino-Japanese War: 1927 to 1937 and 1946 to 1950.

-

On

April 7, 1927, Chiang and several other KMT leaders held a meeting where they proposed that Communist activities were socially and economically

disruptive. On

April 12 in Shanghai, the KMT was purged of leftists with the arrest and

execution of hundreds of CPC members (the Shanghai Massacre). The

KMT resumed its campaign against warlords. Soon, most of eastern China was under the control of the

Nanjing central government, which received prompt international recognition as

the sole legitimate government of China. -

The

revolt of the CPC against the Nationalist government began in August 1927 in

Nanchang (the Nanchang Uprising). A CPC meeting confirmed the party’s intention to take

power by force. By the

fall of 1927, there were now three capitals in China: the internationally

recognized republic capital in Beijing, the CPC and left-wing KMT at Wuhan, and

the right-wing KMT regime at Nanjing, which would remain the KMT capital for

the next decade. -

The ten-year armed

struggle ended with the Xi’an Incident when Chiang Kai-shek was forced

to form the Second United Front against invading forces from Japan.

However,

the alliance of the CPC and the KMT was in name only. The level of actual cooperation

and coordination between them during World War II was at best

minimal. In

general, developments in the Second Sino-Japanese War were to the advantage of

the CPC. -

A fragile truce between the competing forces

fell apart in June 1946 when full-scale war between the CPC and the KMT broke

out. On July 20, 1946, Chiang Kai-shek launched a large-scale

assault on Communist territory, which marked the final phase of the

Chinese Civil War. After three years of exhausting military campaigns, on

October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the People’s Republic of China with its

capital in Beijing.

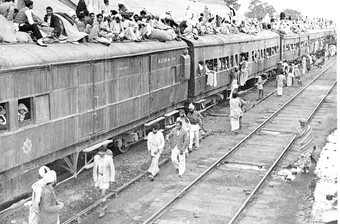

Chiang Kai-shek and approximately two million

Nationalist Chinese retreated from mainland China to the island of Taiwan. - Most

observers expected Chiang’s government to eventually fall in response to a

Communist invasion of Taiwan. Things changed radically

with the onset of the Korean War in 1950. President

Harry Truman ordered the United States Seventh Fleet into the Taiwan Strait to

prevent the ROC and PRC from attacking each other. To this day no armistice or peace treaty has

ever been signed, and there is debate about whether the Civil War has legally

ended.

Key Terms

- Shanghai Massacre

-

The violent suppression of Communist Party organizations in 1927 Shanghai by the military forces of Chiang Kai-shek and conservative factions in the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party, or KMT). Following the incident, conservative KMT elements carried out a full-scale purge of Communists in all areas under their control, and even more violent suppressions occurred in cities such as Guangzhou and Changsha. The purge led to an open split between KMT left and right wings, with Chiang Kai-shek establishing himself as the leader of the right wing at Nanjing in opposition to the original left-wing KMT government led by Wang Jingwei in Wuhan.

- Chinese Civil War

-

A civil war in China fought between forces loyal to the Kuomintang (KMT)-led government of the Republic of China, and forces loyal to the Communist Party of China (CPC). The war began in August 1927 with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s Northern Expedition and ended when major hostilities ceased in 1950.

- Long March

-

A military retreat undertaken by the Red Army of the Communist Party of China, the forerunner of the People’s Liberation Army, to evade the pursuit of the Kuomintang (KMT or Chinese Nationalist Party) army. The Communists, under the eventual command of Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, escaped in a circling retreat to the west and north, which reportedly traversed more than 9,000 kilometers (5,600 miles) over 370 days. The route passed through some of the most difficult terrain of western China by traveling west then north to Shaanxi.

- Xi’an Incident

-

On December 12, 1936, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the Kuomintang, was arrested by Marshal Zhang Xueliang, a former warlord of Manchuria and Commander of the North Eastern Army who had fought against the Japanese occupation of Manchuria and subsequent expansion into Inner Mongolia. The incident led to a truce between the Nationalists and the Communists to form a united front against the threat posed by Japan.

- Kuomintang

-

A major political party in the

Republic of China, currently the second-largest in the country, often

translated as the Nationalist Party of China or Chinese Nationalist Party.

Its predecessor, the Revolutionary Alliance, was one of the major advocates of

the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty and the establishment of a republic. The

party was founded by Song Jiaoren and Sun Yat-sen shortly after the Xinhai

Revolution of 1911. - Northern Expedition

-

A 1926-1928 military campaign led

by Chiang Kai-shek. Its main objective was to unify China, ending the rule

of the Beiyang government and that of local warlords. It led to the end

of the Warlord Era, the reunification of China in 1928, and the

establishment of the Nanjing government. - Second Sino-Japanese War

-

A military conflict fought primarily between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan from 1937 to 1945, which became part of World War II.

The Chinese Civil War: Background

During the Warlord Era, control of the Republic of China was mostly divided among a group of powerful military leaders. The anti-monarchist and nationalist Kuomintang party (KMT) and its leader Sun Yat-sen sought the help of foreign powers to defeat the warlords, who had seized control of much of Northern China. Sun Yat-sen’s efforts to obtain aid from the Western countries were ignored, however, and in 1921 he turned to the Soviet Union. For political expediency, Soviet leadership initiated a dual policy of support for both Sun and the newly established Communist Party of China (CPC), which would eventually found the People’s Republic of China. Thus, the struggle for power in China began between the KMT and the CPC.

Communist members were allowed to join the KMT on an individual basis. However, after Sun died, the KMT split into left- and right-wing movements. Some KMT members worried that the Soviets were trying to destroy the KMT from inside using the CPC. The CPC also began movements in opposition of the Northern Expedition, passing a resolution against it. In March 1927, the KMT held its second party meeting where the Soviets helped pass resolutions against the Expedition and curb Chiang’s power.

Northern Expedition

On April 7, 1927, Chiang and several other KMT leaders held a meeting where they proposed that Communist activities were socially and economically disruptive and had to be curbed for the national revolution to proceed. On April 12 in Shanghai, the KMT was purged of leftists with the arrest and execution of hundreds of CPC members. The CPC referred to this as the April 12 Incident or Shanghai Massacre.

The KMT resumed its campaign against warlords and captured Beijing in June 1928. Soon, most of eastern China was under the control of the Nanjing central government, which received prompt international recognition as the sole legitimate government of China. The KMT government announced, in conformity with Sun Yat-sen, the formula for the three stages of revolution: military unification, political tutelage, and constitutional democracy.

Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, Commander-in-Chief of the National Revolutionary Army (photographer unknown; ca. 1926).

The Chinese Civil War was a major turning point in modern Chinese history, with the CPC gaining control of almost the entire of mainland China, establishing the People’s Republic of China to replace the KMT’s Republic of China. It also caused a lasting political and military standoff between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait, with the ROC in Taiwan and the PRC in mainland China both officially claiming to be the legitimate government of China.

The Civil War Before World War II

During the 1920s, CPC activists retreated underground or to the countryside, where they advocated an armed rebellion. The revolt of the CPC against the Nationalist government began in August 1927 in Nanchang. The Nanchang Uprising saw the formation of a Communist rebel army, the Chinese Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army, which would later become the People’s Liberation Army. A CPC meeting confirmed the party’s intention to take power by force, followed by a violent anti-Communist campaign by Wang Jingwei’s government in Wuhan starting on August 8. On August 14, Chiang Kai-shek fled Nanjing, but KMT forces continued to attempt to suppress the rebellions. By the fall of 1927, there were now three capitals in China: the internationally recognized republic capital in Beijing, the CPC and left-wing KMT at Wuhan, and the right-wing KMT regime at Nanjing, which would remain the KMT capital for the next decade.

This marked the beginning of a ten-year armed struggle, which ended with the Xi’an Incident when Chiang Kai-shek was forced to form the Second United Front against invading forces from Japan. In 1930, the Central Plains War broke out as an internal conflict of the KMT. The attention was turned to rooting out remaining pockets of Communist activity in a series of five encirclement campaigns. In 1934, the CPC broke out of the encirclement. The massive military retreat of Communist forces lasted a year and became known as the Long March, led by Mao Zedong, who soon became the pre-eminent leader of the Party with Zhou in second position.

The march ended when the CPC reached the interior of Shaanxi. Along the way, the Communist army confiscated property and weapons from local warlords and landlords, while recruiting peasants and the poor, solidifying its appeal to the masses. Of the 90,000–100,000 people who began the Long March from the Soviet Chinese Republic, only around 7,000–8,000 made it to Shaanxi.

The Civil War After World War II

The Civil War represented an ideological split between the Communist CPC and the KMT’s brand of Nationalism. It continued intermittently until late 1937, when the two parties came together to form the Second United Front to counter the Japanese threat and prevent the country from crumbling. However, the alliance of the CPC and the KMT was in name only. The level of actual cooperation and coordination between the two parties during World War II was at best minimal. In the midst of the Second United Front, the CPC and the KMT were still vying for territorial advantage in “Free China” (i.e., areas not occupied by the Japanese or ruled by Japanese puppet governments).

In general, developments in the Second Sino-Japanese War were to the advantage of the CPC, as its guerrilla war tactics won them popular support within the Japanese-occupied areas, while the KMT had to defend the country against the main Japanese campaigns since it was the legal Chinese government.

Under the terms of the Japanese unconditional surrender dictated by the United States, Japanese troops were ordered to surrender to KMT troops and not to the CPC, which was present in some of the occupied areas. In Manchuria, however, where the KMT had no forces, the Japanese surrendered to the Soviet Union. Chiang Kai-shek ordered the Japanese troops to remain at their posts to receive the Kuomintang and not surrender their arms to the Communists. However, in the last month of World War II in East Asia, Soviet forces launched the huge strategic offensive operation to attack the Japanese Kwantung Army in Manchuria and along the Chinese-Mongolian border. Chiang Kai-shek realized that he lacked the resources to prevent a CPC takeover of Manchuria following the scheduled Soviet departure.

A fragile truce between the competing forces fell apart on June 21, 1946 when full-scale war between the CPC and the KMT broke out. On July 20, 1946, Chiang Kai-shek launched a large-scale assault on Communist territory, which marked the final phase of the Chinese Civil War. After three years of exhausting military campaigns, on October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the People’s Republic of China with its capital in Beijing. Chiang Kai-shek and approximately two million Nationalist Chinese retreated from mainland China to the island of Taiwan after the loss of Sichuan (at that time, Taiwan was still Japanese territory). In December 1949, Chiang proclaimed Taipei, Taiwan, the temporary capital of the Republic of China and continued to assert his government as the sole legitimate authority in China.

Mao Zedong Proclaiming the Establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949.

On October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the People’s Republic of China with its capital at Beiping, which was renamed Beijing. Chiang Kai-shek and approximately two million Nationalist Chinese retreated from mainland China to the island of Taiwan in December of the same year.

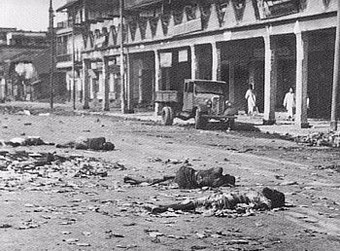

During the war, both the Nationalists and the Communists carried out mass atrocities, with millions of non-combatants deliberately killed by both sides. Benjamin Valentino has estimated atrocities resulted in the deaths of between 1.8 million and 3.5 million people between 1927 and 1949. Atrocities include deaths from forced conscription and massacres.

Aftermath

Most observers expected Chiang’s government to eventually fall in response to a Communist invasion of Taiwan, and the U.S. initially showed no interest in supporting Chiang’s government in its final stand. Things changed radically with the onset of the Korean War in 1950. At this point, allowing a total Communist victory over Chiang became politically impossible for the U.S., and President Harry Truman ordered the United States Seventh Fleet into the Taiwan Strait to prevent the ROC and PRC from attacking each other.

To this day, no armistice or peace treaty has ever been signed, and there is debate about whether the Chinese Civil War has legally ended. Cross-strait relations have been hindered by military threats and political and economic pressure, particularly over Taiwan’s political status, with both governments officially adhering to a “One-China policy.” The PRC still actively claims Taiwan as part of its territory and continues to threaten the ROC with a military invasion if the ROC officially declares independence by changing its name to and gaining international recognition as the Republic of Taiwan. The ROC mutually claims mainland China and they both continue the fight over diplomatic recognition. Today, the war as such occurs on the political and economic fronts in the form of cross-strait relations without actual military action. However, the two separate states have close economic ties.

35.1.4: Chairman Mao and the People’s Republic

Maoism, the guiding

political and military ideology of the Community Party of China,

claimed that peasants should be the essential revolutionary class in China.

Learning Objective

Discuss the key beliefs of the Communist Party of China and Chairman Mao

Key Points

-

Marxist ideas started to spread in China

after the 1919 May Fourth Movement. The Communist Party of China was initially founded by

Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao in the French concession of

Shanghai in 1921 as a study society and an informal network. The Party’s 1st Congress was held in Shanghai and attended by 12 men in July 1921 and later

transferred from Shanghai to Jiaxing. -

In

1922, a proposal that

party members join the Kuomintang (KMT, or Chinese Nationalist Party), on

the grounds that it was easier to transform the Nationalist Party from the

inside than to duplicate its success, was accepted. Under the guidance of the Comintern,

the party was reorganized along Leninist lines in 1923 in preparation for

the Northern Expedition. Mikhail Markovich Borodin of the Comintern negotiated

with Kuomitang’s Sun Yat-sen and Wang Jingwei to implement the 1923 KMT

reorganization and the CPC’s incorporation into the newly expanded party. -

In

1927, as the Northern Expedition approached Shanghai, the Kuomintang leadership

split. The Left Kuomintang at Wuhan kept the alliance with the Communists while

Chiang Kai-shek at Nanking grew increasingly anti-communist. Chiang Kai-shek launched a successful

campaign, and the CPC had to give up their bases and started the Long

March (1934–1935) to search for a new base. During the Long March,

local Communists, such as Mao Zedong and Zhu De, gained power while the

Comintern and the Soviet Union lost control over the CPC. -

After

the conclusion of World War II, the civil war resumed between the Kuomintang

and the Communists. With the Kuomintang’s defeat, Mao Zedong established the

People’s Republic of China (PRC) in Beijing on October 1, 1949. -

Mao’s

revolution that founded the PRC was nominally based on Marxism-Leninism with a

rural focus. During the 1960s

and 1970s, the CPC experienced a significant ideological breakdown with the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union and their allies.

The essential difference between Maoism and

other forms of Marxism is that Mao claimed that peasants should be the

essential revolutionary class in China, because contrary to industrial workers

they were more suited to establish a successful revolution and socialist

society in China. -

Maoism

was widely applied as the guiding political and military ideology of the CPC.

It evolved together with Chairman Mao’s changing views, but its main components

are: the New Democracy, People’s war, Mass line, Cultural revolution, Three Worlds theory, and agrarian socialism.

Key Terms

- Northern Expedition

-

A 1926-1928 military campaign, led

by Chiang Kai-shek. Its main objective was to unify China, ending the rule

of the Beiyang government and that of local warlords. It led to the end

of the Warlord Era, the reunification of China in 1928, and the establishment

of the Nanjing government. - Soviet Republic of China

-

“A state within a state,” referred often in historical sources as the Jiangxi Soviet, established in November 1931 by future Communist Party of China leader Mao Zedong, General Zhu De, and others, that lasted until 1937. Mao Zedong was both its state chairman and prime minister. It was eventually destroyed by the Kuomintang (KMT)’s National Revolutionary Army in a series of 1934 encirclement campaigns.

- Kuomintang

-

A major political party in the

Republic of China, currently the second-largest in the country, often

translated as the Nationalist Party of China or Chinese Nationalist Party.

Its predecessor, the Revolutionary Alliance, was one of the major advocates of

the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty and the establishment of a republic. The

party was founded by Song Jiaoren and Sun Yat-sen shortly after the Xinhai

Revolution of 1911. - Maoism

-

A political theory derived from the teachings of Chinese political leader Mao Zedong (1893–1976). Developed from the 1950s until the Deng Xiaoping reforms in the 1970s, it was widely applied as the guiding political and military ideology of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and as theory guiding revolutionary movements around the world.

- Long March

-

A military retreat undertaken by

the Red Army of the Communist Party of China, the forerunner of the

People’s Liberation Army, to evade the pursuit of the Kuomintang (KMT or

Chinese Nationalist Party) army. The Communists, under the eventual command of

Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, escaped in a circling retreat to the west and

north, which reportedly traversed more than 9,000 kilometers (5,600 miles) over 370

days. The route passed through some of the most difficult terrain of western

China by traveling west then north to Shaanxi. - May Fourth Movement

-

An anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement growing out of student participants in Beijing on May 4, 1919, protesting against the Chinese government’s weak response to the Treaty of Versailles, especially allowing Japan to receive territories in Shandong which was surrendered by Germany after the Siege of Tsingtao.

The Chinese Communist Party: History

Marxist ideas started to spread in China after the 1919 May Fourth Movement, an anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement protesting against the Chinese government’s weak response to the Treaty of Versailles. In June 1920, Comintern agent Grigori Voitinsky was sent to China, where he financed the founding of the Socialist Youth Corps. The Communist Party of China was initially founded by Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao in the French concession of Shanghai in 1921 as a study society and network. There were informal groups in China in 1920 and overseas, but the official beginning was the 1st Congress held in Shanghai and attended by 12 men in July 1921 and later transferred from Shanghai to Jiaxing. The formal and unified name, the Chinese Communist Party, was adopted, and all other names of communist groups were dropped. Mao Zedong was present at the first congress as one of two delegates from a Hunan communist group.

In 1920, Li Dazhao and Chen Duxiu (?) met Comintern agent

Grigori Voitinsky (author unknown).

The Communist Party of China is the founding and ruling political party of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The CPC is the sole governing party of China, although it coexists alongside eight other legal parties that comprise the United Front. These parties, however, hold no real power or independence from the CPC. It was founded in 1921 by Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao.

In 1922, at a surprise special plenum of the central committee, a proposal that party members join the Kuomintang (KMT, or Chinese Nationalist Party), on the grounds that it was easier to transform the Nationalist Party from the inside than to duplicate its success, was issued. Although some leaders opposed the motion, the CPC accepted the decision. Under the guidance of the Comintern, the party was reorganized along Leninist lines in 1923 in preparation for the Northern Expedition. Mikhail Markovich Borodin of the Comintern negotiated with Kuomitang’s Sun Yat-sen and Wang Jingwei to implement the 1923 KMT reorganization and the CPC’s incorporation into the newly expanded party. The death of Sun Yat-sen in 1925 created uncertainty about who would lead the party and whether they would still work with the Communists. Despite these tensions, the Northern Expedition (1926–1927), led by Kuomintang and supported by the CPC, quickly overthrew the warlord government.

In 1927, as the Northern Expedition approached Shanghai, the Kuomintang leadership split. The Left Kuomintang at Wuhan kept the alliance with the Communists while Chiang Kai-shek at Nanking grew increasingly anti-communist. As Chiang Kai-shek consolidated his power, various revolts continued and Communist armed forces created a number of “Soviet Areas.” The largest of these was led by Zhu De and Mao Zedong, who established the Soviet Republic of China in remote areas through peasant riots. Chiang Kai-shek launched a further successful campaign, and the CPC had to give up their bases and started the Long March (1934–1935) to search for a new base. During the Long March, local Communists, such as Mao Zedong and Zhu De, gained power while the Comintern and the Soviet Union lost control over the CPC.

In eight years, CPC membership increased from 40,000 to 1.2 million and its military forces from 30,000 to approximately one million, in addition to more than a million militia support groups. After the conclusion of World War II, the civil war resumed between the Kuomintang and the Communists. With the Kuomintang’s defeat, Mao Zedong established the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in Beijing on October 1, 1949.

Maoism

The CPC’s ideologies have significantly evolved since it established political power in 1949. Mao’s revolution that founded the PRC was nominally based on Marxism-Leninism with a rural focus (based on China’s social situations at the time). During the 1960s and 1970s, the CPC experienced a significant ideological breakdown with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and their allies. Since then, Mao’s peasant revolutionary vision and so-called “continued revolution under the dictatorship of the proletariat” stipulated that class enemies continued to exist even though the socialist revolution seemed to be complete, giving way to the Cultural revolution. This fusion of ideas became known officially as Mao Zedong Thought or Maoism outside of China. It represented a powerful branch of communism that existed in opposition to the Soviet Union’s Marxist revisionism.

The essential difference between Maoism and other forms of Marxism is that Mao claimed that peasants should be the essential revolutionary class in China because they were more suited than industrial workers to establish a successful revolution and socialist society in China. Maoism

was widely applied as the guiding political and military ideology of the CPC. It evolved with Chairman Mao’s changing views, but its main components are:

- The New Democracy

aims to overthrow feudalism and achieve independence from colonialism. However, it dispenses with the rule predicted by Marx and Lenin that a capitalist class would usually follow such a struggle, claiming instead to enter directly into socialism through a coalition of classes fighting the old ruling order. The original symbolism of the flag of China derives from the concept of the coalition. The largest star symbolizes the Communist Party of China’s leadership and the surrounding four smaller stars symbolize “the bloc of four classes”: proletarian workers, peasants, the petty bourgeoisie (small business owners), and the nationally-based capitalists. This is the coalition of classes for Mao’s New Democratic Revolution. - People’s war: Holding that “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun,” Maoism emphasizes the “revolutionary struggle of the vast majority of people against the exploiting classes and their state structures,” which Mao termed “People’s war.” Mobilizing large parts of rural populations to revolt against established institutions by engaging in guerrilla warfare, Maoism focuses on “surrounding the cities from the countryside.” It views the industrial-rural divide as a major division exploited by capitalism, involving industrial urban developed “First World” societies ruling over rural developing “Third World” societies.

- Mass line: This theory holds, contrary to the Leninist vanguard model employed by the Bolsheviks, that party must not be separate from the popular masses, either in policy or in revolutionary struggle. To conduct a successful revolution the needs and demands of the masses must be paramount.

- Cultural revolution: This theory states that the proletarian revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat does not wipe out bourgeois ideology. The class struggle continues, and even intensifies, during socialism. Therefore, a constant struggle against these ideologies and their social roots must be conducted.

The revolution’s stated goal was to preserve “true” Communist ideology in the country by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society, and to re-impose Maoist thought as the dominant ideology within the Party. The concept was applied in practice in 1966, which marked the return of Mao Zedong to a position of power after the Great Leap Forward (a 1958-1961 failed economic and social campaign aimed to rapidly transform the country from an agrarian economy into a socialist society through rapid industrialization and collectivization). The movement paralyzed China politically and negatively affected the country’s economy and society to a significant degree. - Three Worlds: This theory states that during the Cold War, two imperialist states formed the First World: the United States and the Soviet Union. The Second World consisted of the other imperialist states in their spheres of influence. The Third World consisted of the non-imperialist countries. Both the First and the Second World exploit the Third World, but the First World more aggressively.

- Agrarian socialism: Maoism departs from conventional European-inspired Marxism in that its focus is on the agrarian countryside rather than the industrial urban forces. This is known as agrarian socialism. Although Maoism is critical of urban industrial capitalist powers, it views urban industrialization as a prerequisite to expand economic development and socialist reorganization to the countryside, with the goal of rural industrialization that would abolish the distinction between town and countryside.

Portrait of Mao Zedong at Tiananmen Gate attributed to Zhang Zhenshi (1914–1992).

Mao Zedong,

known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary and founding father of the People’s Republic of China, which he ruled as an autocrat Chairman of the Communist Party of China from its establishment in 1949 until his death in 1976. His Marxist-Leninist theories, military strategies, and political policies are collectively known as Maoism or Marxism-Leninism-Maoism.

Following the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, the CPC under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping moved towards Socialism with Chinese characteristics and instituted Chinese economic reform. In reversing some of Mao’s “extreme-leftist” policies, Deng argued that a socialist country and the market economy model were not mutually exclusive.

35.1.5: The Cultural Revolution

The

Cultural Revolution (1966-76) was a sociopolitical movement, set into motion by Mao Zedong,

whose stated goal was to

preserve ‘true’ Communist ideology in China by purging remnants of

capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society. In practice, it led to the persecution and abuse of millions.

Learning Objective

List the key events of the Cultural Revolution

Key Points

-

In

1958, Mao Zedong launched

the Great Leap Forward, an economic and social campaign

to transform the country’s largely agrarian structure into a

socialist society through rapid industrialization and

collectivization. Restrictions on rural populations were enforced

through forced labor, public struggle sessions, and social pressure.The

Great Leap was a social and economic disaster that removed Mao from the position of power in the Communist Party of China. -

During

the early 1960s, a group of moderate pragmatists in the Party favored the idea that Mao be removed from actual power but maintain his

symbolic role. Most historians agree that launching the

Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in 1966 was Mao’s response to the group’s increasing political and economic influence.

The Revolution marked the return of Mao to a position of

power after the Great Leap Forward. -

The

Cultural Revolution was a sociopolitical movement, set into motion by Mao, that

started in 1966 and ended in 1976. Its stated goal was to preserve “true” Communist ideology in China by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional

elements from society and reimposing Maoism as the dominant ideology

within the Party. -

During the Revolution, millions of people were persecuted in the

violent struggles that ensued across the country and suffered abuses including public humiliation, arbitrary imprisonment, torture, sustained

harassment, and seizure of property. A large segment of the population was

forcibly displaced.

The Cultural Revolution also wreaked havoc on

minority cultures in China. -

The Cultural Revolution led to the destruction

of much of China’s traditional cultural heritage and the imprisonment of a huge

number of Chinese citizens as well economic and

social chaos.

Nearly all of the schools and universities in

China were closed. The Revolution also

brought to the forefront numerous internal power

struggles within the Party, many of which had little to do with the larger

battles between Party leaders. -

Although the effects of the Cultural Revolution

were disastrous for millions of people in China, there were some positive

outcomes, particularly in the rural areas, including access to basic education and health care.

Key Terms

- struggle sessions

-

A form of public humiliation and torture used by the Communist Party of China in the Mao Zedong era, particularly during the Cultural Revolution, to shape public opinion and humiliate, persecute, or execute political rivals and class enemies. In general, victims were forced to admit to various crimes before a crowd of people who would verbally and physically abuse the victim until he or she confessed.

- Cultural Revolution

-

A sociopolitical movement in China from 1966 until 1976. Set into motion by Mao Zedong, then Chairman of the Communist Party of China, its stated goal was to preserve “true” Communist ideology in the country by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society and reimposing Maoist thought as the dominant ideology within the Party. The movement paralyzed China politically and had significant negative effects on its economy and society.

- Red Guards

-

A fanatic student mass paramilitary social movement mobilized by Mao Zedong in 1966 and 1967 during the Cultural Revolution.

- Great Chinese Famine

-

A period in the People’s Republic of China between the years 1959 and 1961 characterized by widespread famine. Drought, poor weather, and the policies of the Communist Party of China (Great Leap Forward) contributed, although the relative weights of these contributions are disputed. Scholars have estimated the number of famine victims to be between 20 and 43 million.

- Gang of Four

-

A political faction composed of four Chinese Communist Party officials that came to prominence during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) and was later charged with a series of treasonous crimes. The group’s leading figure was Mao Zedong’s last wife, Jiang Qing. It remains unclear which major decisions were made by Mao Zedong and carried out by the group and which were the result of its own planning.

- Down to the Countryside Movement

-

A policy instituted in the People’s Republic of China in the late 1960s and early 1970s. As a result of what Mao Zedong perceived as anti-bourgeois thinking prevalent during the Cultural Revolution, he declared certain privileged urban youth would be sent to mountainous areas or farming villages to learn from the workers and farmers there. Approximately 17 million youth were sent to rural areas as a result of the movement.

- Great Leap Forward

-

An economic and social campaign by the Communist Party of China (CPC) that took place from 1958 to 1961 and was led by Mao Zedong. It aimed to rapidly transform the country from an agrarian economy into a socialist society through rapid industrialization and collectivization. It is widely considered to have caused the Great Chinese Famine.

Background: The Great Leap Forward

In 1958, Mao Zedong, the Chairman of the Communist Party of China, called for “grassroots socialism” with the aim of accelerating his plans to turn China into a modern industrialized state. In this spirit, he launched the Great Leap Forward, an economic and social campaign to transform the country’s largely agrarian structure into a socialist society through rapid industrialization and collectivization.

Main changes in the lives of rural Chinese included the incremental introduction of mandatory agricultural collectivization. Private farming was prohibited and those engaged in it were persecuted and labeled counter-revolutionaries. Restrictions on rural populations were enforced through forced labor, public struggle sessions (a form of public humiliation and torture), and social pressure. Many communities were assigned the production of a single commodity—steel.

The Great Leap was a social and economic disaster. Farmers attempted to produce steel on a massive scale, partially relying on backyard furnaces to achieve the production targets set by local cadres. The steel produced was of low quality and largely useless. The Great Leap reduced harvest sizes and led to a decline in the production of most goods, except substandard pig iron and steel. Further, local authorities frequently exaggerated production numbers, hiding and intensifying the problem for several years. Simultaneously, chaos in the collectives, bad weather, and exports of food necessary to secure hard currency resulted in the Great Chinese Famine. Historians agree that the Great Leap resulted in tens of millions of deaths, with estimates ranging from 18 to 55 million. Historian Frank Dikötter notes, “coercion, terror, and systematic violence were the foundation of the Great Leap Forward,” which “motivated one of the most deadly mass killings of human history.”

The Party forced Mao to take major responsibility for the Great Leap’s failureIn 1959, Mao resigned as the President of the People’s Republic of China, China’s de jure head of state, and was succeeded by Liu Shaoqi. By the early 1960s, many of the Great Leap’s economic policies were reversed by initiatives spearheaded by Liu and other moderate pragmatists, who were unenthusiastic about Mao’s utopian visions. By 1962, Mao had effectively withdrawn from economic decision-making and focused much of his time on further developing his contributions to Marxist-Leninist social theory, including the idea of “continuous revolution.” This theory’s ultimate aim was to set the stage for Mao to restore his brand of communism and his personal prestige within the Party.

Development of the Revolution

During the early 1960s, State Chairman Liu Shaoqi and General Secretary Deng Xiaoping favored the idea that Mao be removed from actual power but maintain his ceremonial and symbolic role, with the Party upholding all of his positive contributions to the revolution. Most historians agree that

launching the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in 1966 was Mao’s response to Liu and Deng’s increasing political and economic influence (some scholars, however, note that the case for this is overstated). Dikötter argues that Mao launched the Cultural Revolution to wreak revenge on those who had dared to challenge him over the Great Leap Forward.

The Cultural Revolution was a sociopolitical movement, set into motion by Mao, that started in 1966 and ended in 1976 and whose stated goal was to preserve ‘true’ Communist ideology in China by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society and reimposing Maoism as the dominant ideology within the Party. The Revolution marked the return of Mao to a position of power after the Great Leap Forward.

The Revolution was launched after Mao alleged that bourgeois elements had infiltrated the government and society at large, aiming to restore capitalism. He insisted that these “revisionists” be removed through violent class struggle. China’s youth responded to Mao’s appeal by forming Red Guard groups around the country. The movement spread into the military, urban workers, and the Communist Party leadership itself. It resulted in widespread factional struggles in all walks of life. In the top leadership, it led to a mass purge of senior officials, most notably Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping. During the same period, Mao’s personality cult grew to immense proportions.

Millions of people were persecuted in the violent struggles that ensued across the country and suffered a wide range of abuses, including public humiliation, arbitrary imprisonment, torture, sustained harassment, and seizure of property. A large segment of the population was forcibly displaced, most notably the transfer of urban youth to rural regions during the Down to the Countryside Movement.

A poster from the Cultural Revolution, featuring an image of Chairman Mao and published by the government of the People’s Republic of China.

Mao set the scene for the Cultural Revolution by “cleansing” Beijing of powerful officials of questionable loyalty. His approach was less than transparent. He achieved this purge through newspaper articles, internal meetings, and skillfully employing his network of political allies.

The start of the Cultural Revolution brought huge numbers of Red Guards to Beijing, with all expenses paid by the government. The revolution aimed to destroy the “Four Olds” (old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas) and establish the corresponding “Four News,” which ranged from the changing of names and hair cuts to ransacking homes, vandalizing cultural treasures, and desecrating temples. In a few years, countless ancient buildings, artifacts, antiques, books, and paintings were destroyed by the members of the Red Guards.

Believing that certain liberal bourgeois elements of society continued to threaten the socialist framework, the Red Guards struggled against authorities at all levels of society and even set up their own tribunals. Chaos reigned in much of the nation.

During the Cultural Revolution, nearly all of the schools and universities in China were closed and the young intellectuals living in cities were ordered to the countryside to be “re-educated” by the peasants, where they performed hard manual labor and other work.

Mao officially declared the Cultural Revolution to have ended in 1969, but its active phase lasted until the death of the military leader Lin Biao in 1971. After Mao’s death and the arrest of the Gang of Four in 1976, reformers led by Deng Xiaoping gradually began to dismantle the Maoist policies associated with the Cultural Revolution.

Consequences

The Cultural Revolution led to the destruction of much of China’s traditional cultural heritage and the imprisonment of a huge number of citizens as well as general economic and social chaos. Millions of lives were ruined during this period as the Cultural Revolution pierced every part of Chinese life. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, perished in the violence of the Cultural Revolution.

The Revolution aimed to get rid of those who allegedly promoted bourgeois ideas as well as those who were seen as coming from an exploitative family background or belonged to one of the Five Black Categories (landlords, rich farmers, counter-revolutionaries, bad-influencers or “bad elements,” and rightists). Many people perceived to belong to any of these categories, regardless of guilt or innocence, were publicly denounced, humiliated, and beaten. In their revolutionary fervor, students denounced their teachers and children denounced their parents.

The remains of Ming Dynasty Wanli Emperor at the Ming tombs. Red Guards dragged the remains of the Wanli Emperor and Empresses to the front of the tomb, where they were posthumously “denounced” and burned.

During the Cultural Revolution,

libraries full of historical and foreign texts were destroyed and books were burned. Temples, churches, mosques, monasteries, and cemeteries were closed down and sometimes converted to other uses, looted, and destroyed. Among the countless acts of destruction, Red Guards from Beijing Normal University desecrated and badly damaged the burial place of Confucius.

Although the effects of the Cultural Revolution were disastrous for millions of people in China, there were some positive outcomes, particularly in the rural areas. For example, the upheavals of the Cultural Revolution and the hostility towards the intellectual elite are widely accepted to have damaged the quality of education in China, especially the higher education system. However, some policies also provided many in the rural communities with middle school education for the first time, which facilitated rural economic development in the 1970s and 80s. Similarly, a large number of health personnel was deployed to the countryside. Some farmers were given informal medical training and healthcare centers were established in rural communities. This led to a marked improvement in the health and the life expectancy of the general population.

The Cultural Revolution also brought to the forefront numerous internal power struggles within the Party, many of which had little to do with the larger battles between Party leaders but resulted instead from local factionalism and petty rivalries that were usually unrelated to the Revolution itself. Because of the chaotic political environment, local governments lacked organization and stability, if they existed at all. Members of different factions often fought on the streets and political assassinations, particularly in predominantly rural provinces, were common. The masses spontaneously involved themselves in factions and took part in open warfare against other factions. The ideology that drove these factions was vague and sometimes non-existent, with the struggle for local authority being the only motivation for mass involvement.

The Cultural Revolution wreaked havoc on minority cultures in China. In Inner Mongolia, some 790,000 people were persecuted. In Xinjiang, copies of the Qur’an and other books of the Uyghur people were burned. Muslim imams were reportedly paraded around with paint splashed on their bodies. In the ethnic Korean areas of northeast China, language schools were destroyed. In Yunnan Province, the palace of the Dai people’s king was torched and a massacre of Muslim Hui people at the hands of the People’s Liberation Army in Yunnan, known as the Shadian Incident, reportedly claimed over 1,600 lives in 1975.

35.1.6: The Sino-Soviet Split

The Sino-Soviet split was the deterioration and eventual breakup of political and ideological relations between China and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, which had massive domestic and geopolitical consequences.

Learning Objective

Discuss why the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic broke their relations and the consequences of the split

Key Points

-

Mao and his supporters argued that traditional

Marxism was rooted in industrialized European society and could not be applied

to Asian peasant societies. However, although Mao continued to develop his own thought

based on that presumption, in the 1950s, Soviet-guided China followed Stalin’s model of centralized economic development. -

After Stalin’s death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev

made an effort to further the burgeoning relations with China begun by Stalin, traveling to the country and making various deals with the

Chinese leadership that expanded the economic and political alliances between

the two countries. The 1953-56 period

has

been called the “golden age” of Sino-Soviet relations. -

Relations between the USSR and the PRC began to

deteriorate in 1956 after Khrushchev revealed his “Secret Speech” at the 20th

Communist Party Congress. The “Secret Speech” criticized many of Stalin’s

policies, especially his purges of Party members, and marked the beginning of

Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization process. This created a serious domestic problem

for Mao, who had supported many of Stalin’s policies and modeled many of his

own after them. -

At

first, the Sino-Soviet split manifested indirectly as criticism towards each

other’s client states. By 1960, the mutual criticism became public when Khrushchev and Peng Zhen had an open argument at the Romanian

Communist Party congress.After

a series of unconvincing compromises and explicitly hostile gestures, in 1962,

the PRC and the USSR finally broke relations. - The split, seen by historians as one of the key

events of the Cold War, had massive consequences for the two powers and for the

world. The USSR had a network of communist parties it supported. China now

created its own rival network to battle it out for local control of the left in

numerous countries.

Mao launched the Cultural

Revolution (1966–76), largely to prevent the development of Russian-style

bureaucratic communism of the USSR. The ideological split also escalated

to small-scale warfare between Russia and China. -

After

the regime of Mao Zedong, the PRC–USSR ideological schism no longer shaped

domestic politics but continued to impact geopolitics, including such global developments as the establishment of post-colonial Indochina, the

Cambodian-Vietnamese War (1975–79) that deposed Pol Pot in 1978, the Sino-Vietnamese War (1979), and the 1979 invasion of the USSR on

Afghanistan. Relations

between China and the Soviet Union remained tense until the visit of Soviet

leader Mikhail Gorbachev to Beijing in 1989.

Key Terms

- Cultural Revolution

-

A sociopolitical

movement that took place in China from 1966 until 1976. Set into

motion by Mao Zedong, then Chairman of the Communist Party of China, its stated

goal was to preserve ‘true’ Communist ideology in the country by purging

remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society

and reimposing Maoist thought as the dominant ideology within the

Party. The movement paralyzed China politically and had significant negative effects on economy and society. - Hundred Flowers Campaign

-

A period in 1956 in the People’s Republic of China during which the Communist Party of China (CPC) encouraged its citizens to openly express their opinions of the communist regime. Differing views and solutions to national policy were encouraged based on the famous expression by Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong: “The policy of letting a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend is designed to promote the flourishing of the arts and the progress of science.” After this brief period of liberalization, Mao abruptly changed course.

- Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech”

-

A report by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev made to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on February 25, 1956. Khrushchev was sharply critical of the reign of deceased General Secretary and Premier Joseph Stalin, particularly with respect to the purges which marked the late 1930s.

- Five Year Plan

-

A nationwide centralized economic plan in the Soviet Union developed by a state planning committee that was part of the ideology of the Communist Party for the development of the Soviet economy. A series of these plans was developed in the Soviet Union while similar Soviet-inspired plans emerged across other communist countries during the Cold War era.

- Great Leap Forward

-

An economic and social

campaign by the Communist Party of China (CPC) that took place from 1958

to 1961 and was led by Mao Zedong. It aimed to rapidly transform the country

from an agrarian economy into a socialist society through rapid

industrialization and collectivization. It is widely considered to have

caused the Great Chinese Famine. - Cuban missile crisis

-

A 13-day (October 16–28, 1962) confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union concerning American ballistic missile deployment in Italy and Turkey with consequent Soviet ballistic missile deployment in Cuba. The confrontation, elements of which were televised, was the closest the Cold War came to escalating into a full-scale nuclear war.

Background: Mao and Joseph Stalin

During both the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45) against the Japanese Empire and the ongoing Chinese Civil War against the Nationalist Kuomintang, Mao Zedong ignored much of the politico-military advice and direction from Soviet General Secretary Joseph Stalin and the Comintern because of the practical difficulty in applying traditional Leninist revolutionary theory to China. After World War II, Stalin advised Mao against seizing power because the Soviet Union had signed a Treaty of Friendship and Alliance with the Nationalists in 1945. This time, Mao obeyed Stalin’s advice, calling him “the only leader of our party.” However, Stalin broke the treaty, requiring Soviet withdrawal from Manchuria three months after Japan’s surrender, and gave Manchuria to Mao. After the CPC’s victory over the KMT, a Moscow visit by Mao from December 1949 to February 1950 culminated in the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance (1950), which included a $300 million low-interest loan and a 30-year military alliance clause.

However, Mao and his supporters argued that traditional Marxism was rooted in industrialized European society and could not be applied to Asian peasant societies. Although Mao continued to develop his own thought based on that presumption, in the 1950s, Soviet-guided China followed the Soviet model of centralized economic development, emphasizing heavy industry and not treating consumer goods as a priority. Simultaneously, by the late 1950s, Mao had developed ideas that became the basis for the Great Leap Forward (1958–61), a campaign based on the assumption of the centrality of the rural working class to China’s economy and political system.

Communism after Stalin’s Death

After Stalin’s death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev made an effort to further the burgeoning relations with China begun by Stalin, traveling to the country in 1954 and making deals with the Chinese leadership that expanded the economic and political alliances between the two countries. Khrushchev also acknowledged Stalin’s unfair trade deals and revealed a list of active KGB agents placed in China during Stalin’s reign. Khrushchev was able to reach many prominent economic agreements during his visit, including an additional loan for economic development from the USSR to the PRC and a trade of human capital that included sending Soviet economic experts and political advisors to China and Chinese economic experts and unskilled labor to the USSR.

In 1955, relations only continued to improve. Economic trade collaboration began to develop to the point that 60% of Chinese exports were to the USSR. Mao also began to implement the Chinese but USSR-modeled Five Year Plan. Mao also promoted and encouraged the collectivization of agriculture in the PRC, applauding Stalin’s policies towards agriculture and industrialization. Finally, the two countries collaborated when setting their respective foreign policies. This period, from roughly Stalin’s death in 1953 to Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech” in 1956, has been called the “golden age” of Sino-Soviet relations.

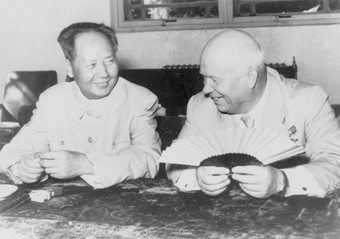

Photograph of Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Nikita Khrushchev: publicly, international allies; privately, ideological enemies. (China,1958, author unknown).

Although before 1956 Mao and Khrushchev managed to sign numerous agreements between China and the Soviet Union, the two leaders did not develop a positive personal relationship. Mao found Khrushchev’s personality grating and Khrushchev was unimpressed by Chinese culture.

The Sino-Soviet Split

Relations between the USSR and the PRC began to deteriorate in 1956 after Khrushchev revealed his “Secret Speech” at the 20th Communist Party Congress. The “Secret Speech” criticized many of Stalin’s policies, especially his purges of Party members, and marked the beginning of Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization process. This created a serious domestic problem for Mao, who had supported many of Stalin’s policies and modeled many of his own after them. With Khrushchev’s denouncement of Stalin, many people questioned Mao’s decisions. Moreover, the emergence of movements fighting for the reforms of the existing communist systems across East-Central Europe after Khrushchev’s speech worried Mao. Brief political liberalization introduced to prevent similar movements in China, most notably lessened political censorship known as the Hundred Flowers Campaign, backfired against Mao, whose position within the Party only weakened. This convinced him further that de-Stalinization was a mistake. Mao took a sharp turn to the left ideologically, which contrasted with the ideological softening of de-Stalinization. With Khrushchev’s strengthening position as Soviet leader, the two countries were set on two different ideological paths.

Mao’s implementation of the Great Leap Forward, which utilized communist policies closer to Stalin than to Khrushchev, including forming a personality cult around Mao as well as more Stalinist economic policies. This angered the USSR, especially after Mao criticized Khrushchev’s economic policies through the plan while also calling for more Soviet aid. The Soviet leader saw the new policies as evidence of an increasingly confrontational and unpredictable China.

At first, the Sino-Soviet split manifested indirectly as criticism towards each other’s client states. China denounced Yugoslavia and Tito, who pursued a non-aligned foreign policy, while the USSR denounced Enver Hoxha and the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania, which refused to abandon its pro-Stalin stance and sought its survival in alignment with China.

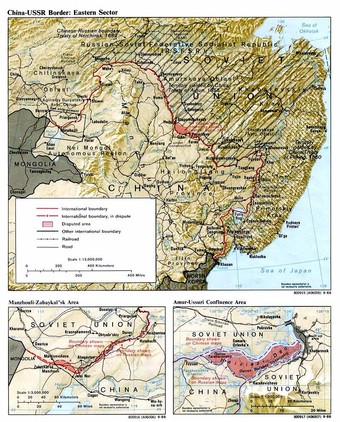

The USSR also offered moral support to the Tibetan rebels in their 1959 Tibetan uprising against China. By 1960, the mutual criticism moved out in the open, when Khrushchev and Peng Zhen had an open argument at the Romanian Communist Party congress. Khrushchev characterized Mao as “a nationalist, an adventurist, and a deviationist.” In turn, China’s Peng Zhen called Khrushchev a Marxist revisionist, criticizing him as “patriarchal, arbitrary and tyrannical.” Khrushchev denounced China with an 80-page letter to the conference and responded to Mao by withdrawing around 1,400 Soviet experts and technicians from China, leading to the cancellation of more than 200 scientific projects intended to foster cooperation between the two nations.