27.1: The Last Chinese Dynasty

27.1.1: The Qing Dynasty

At the peak of the Qing dynasty (1644-1912),

China ruled more than one-third of the world’s

population, had the largest economy in the world, and

by

area was one of the largest empires ever.

Learning Objective

Describe the lifespan of the Qing Dynasty

Key Points

-

The

Qing dynasty was the last imperial dynasty in China. What would become the Manchu state was founded by Nurhaci, the chieftain of a minor

Jurchen tribe known as Aisin Gioro in Jianzhou (Manchuria) in the early 17th

century. Originally a vassal of the Ming emperors, Nurhachi embarked on an

intertribal feud in 1582 that escalated into a campaign to unify the nearby

tribes. In 1635, Nurchaci’s son and successor Huangtaiji changed the name

of the Jurchen ethnic group to the Manchu. -

In

1618, Nurhachi announced the Seven Grievances and began to rebel against the Ming domination, effectively a declaration of war. Relocating

his court to Liaodong in 1621 brought Nurhachi in close contact with the Khorchin

Mongol domains on the plains of Mongolia. The

Khorchin proved a useful ally in the war. Two of Nurhaci’s critical contributions were ordering the creation of a written

Manchu script based on the Mongolian and the creation of the civil and military administrative system,

which eventually evolved into the Eight Banners. -

At

the same time, the Ming dynasty was fighting for its survival. Ming government

officials fought against each other, against fiscal collapse, and against a

series of peasant rebellions. In

1644, Beijing fell to a rebel army led by Li Zicheng. During the turmoil, the last Ming emperor hanged

himself on a tree in the imperial garden outside the Forbidden City. Li

Zicheng, a former minor Ming official, established a short-lived Shun dynasty. -

Under the reign of Dorgon, whom historians have called “the mastermind of the Qing conquest” and “the principal architect of the great Manchu enterprise,” the Qing continued to subdue all areas previously under the Ming.

The decades of Manchu conquest caused enormous

loss of lives and the economy of China shrank drastically. In total, the

Qing conquest of the Ming (1618–1683) cost as many as 25 million lives. -

The Qianlong reign (1735–96) saw the dynasty’s

apogee and initial decline in prosperity and imperial control. The population

rose to some 400 million, but taxes and government revenues were fixed at a low

rate, virtually guaranteeing eventual fiscal crisis. Corruption set in, rebels

tested government legitimacy, and ruling elites did not change their mindsets

in the face of changes in the world system. -

The early Qing emperors adopted the bureaucratic

structures and institutions from the preceding Ming dynasty but split rule

between Han Chinese and Manchus, with some positions also given to Mongols.

Like previous dynasties, the Qing recruited officials via the imperial

examination system until it was abolished in 1905. To keep routine administration

from subsuming the running of the empire, the Qing emperors made sure that all

important matters were decided in the Inner Court, dominated by the

imperial family and Manchu nobility.

Key Terms

- Forbidden City

-

The Chinese imperial palace from the Ming dynasty to the end of the Qing dynasty (1420 to 1912). It is located in the center of Beijing, China, and now houses the Palace Museum. It served as the home of emperors and their households as well as the ceremonial and political center of Chinese government for almost 500 years.

- Ten Great Campaigns

-

A series of military campaigns launched by the Qing Empire of China in the mid to late 18th century during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (1735–96). They included three campaigns to enlarge the area of Qing control in Central Asia and seven police actions on frontiers already established.

- Revolt of the Three Feudatories

-

A rebellion lasting from 1673 to 1681 in the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) during the early reign of the Kangxi Emperor (1661–1722). The revolt was led by the three lords of the fiefdoms in Yunnan, Guangdong, and Fujian provinces against the Qing central government.

- Eight Banners

-

Administrative/military divisions under the Qing dynasty into which all Manchu households were placed. In war, they functioned as armies, but the system was also the basic organizational framework of Manchu society. Created in the early 17th century by Nurhaci, the armies played an instrumental role in his unification of the fragmented Jurchen people (later renamed the Manchus) and in the Qing dynasty’s conquest of the Ming dynasty.

- Seven Grievances

-

A manifesto announced by Nurhaci in 1618. It

enumerated grievances and effectively declared war against the Ming dynasty. - Qing dynasty

-

The last imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1644 to 1912 with a brief, abortive restoration in 1917. It was preceded by the Ming dynasty and succeeded by the Republic of China. Its multi-cultural empire lasted almost three centuries and formed the territorial base for the modern Chinese state.

Rise to Power

The Qing dynasty (1644–1911) was the last imperial dynasty in China. It was founded not by Han Chinese, who constitute the majority of the Chinese population, but by a sedentary farming people known as the Jurchen. What would become the Manchu state was founded by Nurhaci, the chieftain of a minor Jurchen tribe known as Aisin Gioro in Jianzhou (Manchuria) in the early 17th century. Originally a vassal of the Ming emperors, Nurhachi embarked on an intertribal feud in 1582 that escalated into a campaign to unify the nearby tribes. By 1616, he sufficiently consolidated Jianzhou to be able to proclaim himself Khan of the Great Jin, in reference to the previous Jurchen dynasty. In 1635, Nurchaci’s son and successor Huangtaiji changed the name of the Jurchen ethnic group to the Manchu.

In 1618, Nurhachi announced the Seven Grievances, a document that enumerated grievances against the Ming, and began to rebel against the Ming domination. Nurhaci’s demand that the Ming pay tribute to him to redress the grievances was effectively a declaration of war, as the Ming were not willing to pay a former tributary. Shortly after, Nurhaci began to invade the Ming in Liaoning in southern Manchuria. After a series of successful battles, he relocated his capital from Hetu Ala to successively bigger captured Ming cities in Liaodong Peninsula: first Liaoyang in 1621, then Shenyang (Mukden) in 1625.

Relocating his court to Liaodong brought Nurhachi in close contact with the Khorchin Mongol domains on the plains of Mongolia. Nurhachi’s policy towards the Khorchins was to seek their friendship and cooperation against the Ming, securing his western border from a powerful potential enemy. Further, the Khorchin proved a useful ally in the war, lending the Jurchens their expertise as cavalry archers. To guarantee this new alliance, Nurhachi initiated a policy of inter-marriages between the Jurchen and Khorchin nobilities. This is a typical example of Nurhachi initiatives that eventually became official Qing government policy. During most of the Qing period, the Mongols gave military assistance to the Manchus.

Two of Nurhaci’s critical contributions were ordering the creation of a written Manchu script based on the Mongolian after the earlier Jurchen script was forgotten and the creation of the civil and military administrative system, which eventually evolved into the Eight Banners, the defining element of Manchu identity.

The Eight Banners were administrative/military divisions under the Qing dynasty into which all Manchu households were placed. In war, the Eight Banners functioned as armies, but the banner system was also the basic organizational framework of Manchu society. The banner armies played an instrumental role in his unification of the fragmented Jurchen people and in the Qing dynasty’s conquest of the Ming dynasty.

At the same time, the Ming dynasty was fighting for its survival. Ming government officials fought against each other, against fiscal collapse, and against a series of peasant rebellions. In 1640, masses of Chinese peasants who were starving, unable to pay their taxes, and no longer in fear of the frequently defeated Chinese army began to form huge bands of rebels. The Chinese military, caught between fruitless efforts to defeat the Manchu raiders from the north and huge peasant revolts in the provinces, essentially fell apart. Unpaid and unfed, the army was defeated by Li Zicheng – now self-styled as the Prince of Shun. In 1644, Beijing fell to a rebel army led by Li Zicheng when the city gates were opened from within. During the turmoil, the last Ming emperor hanged himself on a tree in the imperial garden outside the Forbidden City. Li Zicheng, a former minor Ming official, established a short-lived Shun dynasty.

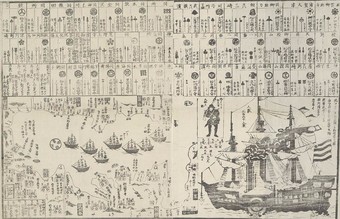

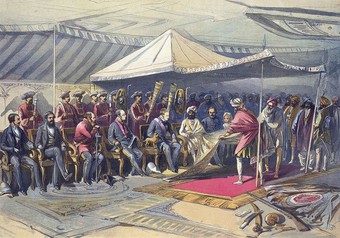

Decisive Battle of Shanhai Pass in 1644 that led to the formation of the Qing dynasty

At the Battle of Shanhai Pass, Qing Prince-Regent Dorgon allied with former Ming general Wu Sangui to defeat rebel leader Li Zicheng of the Shun dynasty, allowing Dorgon and the Manchus to rapidly conquer Beijing and replace the Ming dynasty.

Qing Empire

Under the reign of Dorgon, whom historians have called “the mastermind of the Qing conquest” and “the principal architect of the great Manchu enterprise,” the Qing eventually subdued the capital area, received the capitulation of Shandong local elites and officials, and conquered Shanxi and Shaanxi, then turned their eyes to the rich commercial and agricultural region of Jiangnan south of the lower Yangtze River. They also wiped out the last remnants of rival regimes (Li Zicheng was killed in 1645). Finally, they managed to kill claimants to the throne of the Southern Ming in Nanjing (1645) and Fuzhou (1646) and chased Zhu Youlang, the last Southern Ming emperor, out of Guangzhou (1647) and into the far southwestern reaches of China.

Over the next half-century, all areas previously under the Ming dynasty were consolidated under the Qing. Xinjiang, Tibet, and Mongolia were also formally incorporated into Chinese territory. Between 1673 and 1681, the Kangxi Emperor suppressed the Revolt of the Three Feudatories, an uprising of three generals in Southern China denied hereditary rule of large fiefdoms granted by the previous emperor. In 1683, the Qing staged an amphibious assault on southern Taiwan, bringing down the rebel Kingdom of Tungning, which was founded by the Ming loyalist Koxinga in 1662 after the fall of the Southern Ming and had served as a base for continued Ming resistance in Southern China. The Qing defeated the Russians at Albazin, resulting in the Treaty of Nerchinsk.

The Russians gave up the area north of the Amur River as far as the Stanovoy Mountains and kept the area between the Argun River and Lake Baikal. This border along the Argun River and Stanovoy Mountains lasted until 1860.

The decades of Manchu conquest caused enormous loss of lives and the economy of China shrank drastically. In total, the Qing conquest of the Ming (1618–1683) cost as many as 25 million lives.

Dorgon (1612 – 1650), also known as Hošoi Mergen Cin Wang, the Prince Rui, was Nurhaci’s 14th son and a prince of the Qing Dynasty

Because of his own political insecurity, Dorgon ruled in the name of the emperor at the expense of rival Manchu princes, many of whom he demoted or imprisoned under one pretext or another. Although the period of his regency was relatively short, Dorgon cast a long shadow over the Qing dynasty.

The Ten Great Campaigns of the Qianlong Emperor from the 1750s to the 1790s extended Qing control into Central Asia. The early rulers maintained their Manchu ways and while their title was Emperor, they used khan to the Mongols and were patrons of Tibetan Buddhism. They governed using Confucian styles and institutions of bureaucratic government and retained the imperial examinations to recruit Han Chinese to work under or in parallel with Manchus. They also adapted the ideals of the tributary system in dealing with neighboring territories.

The Qianlong reign (1735–96) saw the dynasty’s apogee and initial decline in prosperity and imperial control. The population rose to some 400 million, but taxes and government revenues were fixed at a low rate, virtually guaranteeing eventual fiscal crisis. Corruption set in, rebels tested government legitimacy, and ruling elites did not change their mindsets in the face of changes in the world system. Still, by the end of Qianlong Emperor’s long reign, the Qing Empire was at its zenith. China ruled more than one-third of the world’s population and had the largest economy in the world. By area it was one of the largest empires ever.

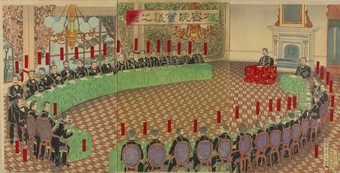

Government

The early Qing emperors adopted the bureaucratic structures and institutions from the preceding Ming dynasty but split rule between Han Chinese and Manchus, with some positions also given to Mongols. Like previous dynasties, the Qing recruited officials via the imperial examination system until the system was abolished in 1905. The Qing divided the positions into civil and military positions. Civil appointments ranged from an attendant to the emperor or a Grand Secretary in the Forbidden City (highest) to prefectural tax collector, deputy jail warden, deputy police commissioner, or tax examiner. Military appointments ranged from a field marshal or chamberlain of the imperial bodyguard to third class sergeant, corporal, or first or second class private.

The formal structure of the Qing government centered on the Emperor as the absolute ruler, who presided over six boards (Ministries), each headed by two presidents and assisted by four vice presidents. In contrast to the Ming system, however, Qing ethnic policy dictated that appointments be split between Manchu noblemen and Han officials who had passed the highest levels of the state examinations. The Grand Secretariat, a key policy-making body under the Ming, lost its importance during the Qing and evolved into an imperial chancery. The institutions inherited from the Ming formed the core of the Qing Outer Court, which handled routine matters and was located in the southern part of the Forbidden City.

In order to keep routine administration from taking over the empire, the Qing emperors made sure that all important matters were decided in the Inner Court, dominated by the imperial family and Manchu nobility and located in the northern part of the Forbidden City. The core institution of the inner court was the Grand Council. It emerged in the 1720s under the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor as a body charged with handling Qing military campaigns against the Mongols, but soon took over other military and administrative duties and centralized authority under the crown. The Grand Councillors served as a sort of privy council to the emperor.

27.1.2: Society Under the Qing

Under Qing rule, the empire’s population expanded rapidly and migrated extensively, the economy grew, and arts and culture flourished, but the development of the military gradually

weakened

central government’s grip on the country.

Learning Objective

Describe the characteristics of Qing society

Key Points

-

During

the early and mid-Qing period, the population grew rapidly and was remarkably

mobile. Evidence suggests that the empire’s expanding population moved in a

manner unprecedented in Chinese history. Migrants relocated hoping for either

permanent resettlement or, at least in theory, a temporary stay. -

The

Qing society was divided into five relatively closed estates. The elites

consisted of the estates of the officials, the comparatively minuscule

aristocracy, and the intelligentsia. There also existed two major categories of

ordinary citizens: the “good” and the “mean.” -

In

the 18th century, markets continued to expand but with more trade between

regions, a greater dependence on overseas markets, and a greatly increased

population.

The

government broadened land ownership by returning land that was sold to

large landowners in the late Ming period by families unable to pay the land

tax. To give people more incentive to participate in the market, the tax

burden was reduced and the corvée system

replaced with a head tax used to hire laborers.

The relative peace and import of new crops to China from the Americas contributed to population growth. -

The

early Qing military was rooted in the Eight Banners first developed by Nurhaci.

During Qianlong’s reign,

the emperor emphasized Manchu ethnicity, ancestry, language, and

culture in the Eight Banners, and in 1754 started a mass discharge of Han bannermen.

This led to a change from Han majority to a Manchu majority within the Eight

Banner system. The eventual decision to turn the banner troops into a

professional force led to their decline. -

After a series of military

defeats in the mid-19th century, the Qing court ordered a Chinese official,

Zeng Guofan, to organize regional and village militias into an emergency army.

Zeng Guofan relied on local gentry to raise a new type of

military organization, known as the Xiang Army. The Xiang Army and its successor the Huai

Army were

collectively called the Yong Ying (Brave Camp). The Yong Ying system signaled

the end of Manchu dominance in Qing military establishment. -

Under the Qing,

traditional forms of art flourished and innovations developed rapidly. High

levels of literacy, a successful publishing industry, prosperous cities, and

the Confucian emphasis on cultivation all fed a lively and creative set of

cultural fields, including literature, fine arts, and even cuisine.

Key Terms

- Eight Banners

-

Administrative/military

divisions under the Qing dynasty into which all Manchu households were

placed. In war, they functioned as armies, but the system was also the basic

organizational framework of Manchu society. Created in the early 17th

century by Nurhaci, the armies played an instrumental role in his unification

of the fragmented Jurchen people (later renamed the Manchus) and

in the Qing dynasty’s conquest of the Ming dynasty. - Great Divergence

-

A term coined by Samuel Huntington (also known as the European miracle, a term coined by Eric Jones in 1981), referring to the process by which the Western world (i.e. Western Europe and the parts of the New World where its people became the dominant populations) overcame pre-modern growth constraints and emerged during the 19th century as the most powerful and wealthy world civilization of all time, eclipsing Qing China, Mughal India, Tokugawa Japan, Joseon Korea, and the Ottoman Empire.

- Xiang Army

-

A standing army organized by Zeng Guofan from existing regional and village militia forces to contain the Taiping rebellion in Qing China (1850 to 1864). The name is taken from the Hunan region where the army was raised. It was financed through local nobles and gentry as opposed to the centralized Manchu-led Qing dynasty. Although it was raised specifically to address problems in Hunan, the army formed the core of the new Qing military establishment and thus forever weakened the Manchu influence within the military.

- Green Standard Army

-

A category of military units under the control of the Qing dynasty. It was made up mostly of ethnic Han soldiers and operated concurrently with the Manchu-Mongol-Han Eight Banner armies. In areas with a high concentration of Hui people, Muslims served as soldiers. After the Qing consolidated control over China, it was primarily used as a police force.

- Yong Ying

-

A type of regional army that emerged in the 1800s in Qing dynasty army, which fought in most of China’s wars after the Opium War and numerous rebellions exposed the ineffectiveness of the Manchu Eight Banners and Green Standard Army. It was created from the earlier tuanlian militias.

During the early and mid-Qing period, the population grew rapidly and was remarkably mobile. Evidence suggests that the empire’s expanding population moved in a manner unprecedented in Chinese history. Migrants relocated hoping for either permanent resettlement or at least in theory, a temporary stay. The latter included the empire’s increasingly large and mobile manual workforce, its densely overlapping internal diaspora of merchant groups, and the movement of Qing subjects overseas, largely to Southeastern Asia, in search of trade and other economic opportunities.

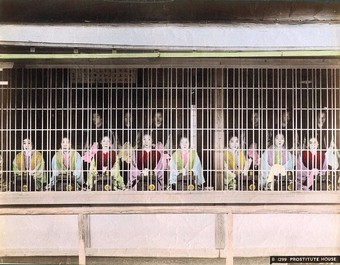

The Qing society was divided into five relatively closed estates. The elites consisted of the estates of the officials, the comparatively minuscule aristocracy, and the intelligentsia. There also existed two major categories of ordinary citizens: the “good” and the “mean.” The majority of the population belonged to the first category and were described as liangmin, a legal term meaning good people, as opposed to jianmin meaning the mean (or ignoble) people. Qing law explicitly stated that the traditional four occupational groups of scholars, farmers, artisans, and merchants were “good,” with the status of commoners. On the other hand, slaves or bonded servants, entertainers (including prostitutes and actors), and low-level employees of government officials were the “mean” people, considered legally inferior to commoners.

Economy

By the end of the 17th century, the Chinese economy had recovered from the devastation caused by the wars in which the Ming dynasty were overthrown. In the 18th century, markets continued to expand but with more trade between regions, a greater dependence on overseas markets, and a greatly increased population. After the re-opening of the southeast coast, which was closed in the late 17th century, foreign trade was quickly re-established and expanded at 4% per annum throughout the latter part of the 18th century. China continued to export tea, silk, and manufactures, creating a large, favorable trade balance with the West. The resulting inflow of silver expanded the money supply, facilitating the growth of competitive and stable markets.

The government broadened land ownership by returning land that was sold to large landowners in the late Ming period by families unable to pay the land tax. To give people more incentives to participate in the market, the tax burden was reduced in comparison with the late Ming and the corvée system replaced with a head tax used to hire laborers. A system of monitoring grain prices eliminated severe shortages and enabled the price of rice to rise slowly and smoothly through the 18th century. Wary of the power of wealthy merchants, Qing rulers limited their trading licenses and usually banned new mines, except in poor areas. Some scholars see these restrictions on the exploitation of domestic resources and limits imposed on foreign trade as a cause of the Great Divergence by which the Western world overtook China economically.

By the end of the 18th century the population had risen to 300 million from approximately 150 million during the late Ming dynasty. This rise is attributed to the long period of peace and stability in the 18th century and the import of new crops China received from the Americas, including peanuts, sweet potatoes, and maize. New species of rice from Southeast Asia led to a huge increase in production. Merchant guilds proliferated in all of the growing Chinese cities and often acquired great social and even political influence. Rich merchants with official connections built up huge fortunes and patronized literature, theater, and the arts. Textile and handicraft production boomed.

Military

The early Qing military was rooted in the Eight Banners first developed by Nurhaci to organize Jurchen society beyond petty clan affiliations. The banners were differentiated by color. The yellow, bordered yellow, and white banners were known as the Upper Three Banners and remained under the direct command of the emperor. The remaining banners were known as the Lower Five Banners. They were commanded by hereditary Manchu princes descended from Nurhachi’s immediate family. Together, they formed the ruling council of the Manchu nation as well as high command of the army.

Nurhachi’s son Hong Taiji expanded the system to include mirrored Mongol and Han Banners. After capturing Beijing in 1644, the relatively small Banner armies were further augmented by the Green Standard Army, made up of Ming troops who had surrendered to the Qing. They eventually outnumbered Banner troops three to one. They maintained their Ming-era organization and were led by a mix of Banner and Green Standard officers.

Banner armies were organized along ethnic lines, namely Manchu and Mongol, but including non-Manchu bonded servants registered under the household of their Manchu masters. During Qianlong’s reign, the Qianlong Emperor emphasized Manchu ethnicity, ancestry, language, and culture in the Eight Banners, and in 1754 started a mass discharge of Han bannermen. This led to a change from Han majority to a Manchu majority within the Eight Banner system. The eventual decision to turn the banner troops into a professional force led to its decline as a fighting force.

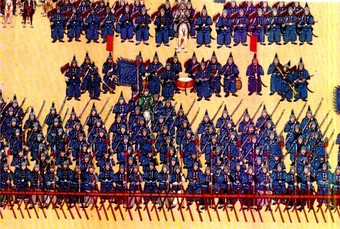

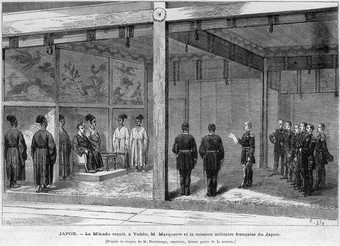

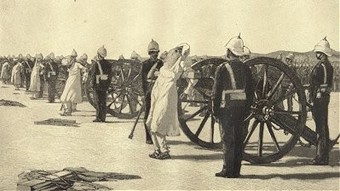

Soldiers of the blue banner parading in front of Emperor Qianlong

Initially, Nurhaci’s forces were organized into small hunting parties of about a dozen men related by blood, marriage, clan, or place of residence, as was the Jurchen custom. In 1601, Nurhaci reorganized his troops. Four banners were originally created: Yellow, White, Red, and Blue, each named after the color of its flag. In 1615, the number of banners was doubled through the creation of “bordered” banners. The troops of each of the original four banners would be split between a plain and a bordered banner. The bordered variant of each flag was to have a red border, except for the Bordered Red Banner, which had a white border instead.

After a series of military defeats in the mid-19th century, the Qing court ordered a Chinese official, Zeng Guofan, to organize regional and village militias into an emergency army. He relied on local gentry to raise a new type of military organization that became known as the Xiang Army, named after the Hunan region where it was raised. The Xiang Army was a hybrid of local militia and a standing army. It was given professional training, but was paid for out of regional coffers and funds its commanders – mostly members of the Chinese gentry – could muster. The Xiang Army and its successor, the Huai Army, created by Zeng Guofan’s colleague and mentee Li Hongzhang, were collectively called the Yong Ying (Brave Camp). The Yong Ying system signaled the end of Manchu dominance in Qing military establishment. The fact that the corps were financed through provincial coffers and were led by regional commanders weakened central government’s grip on the whole country. This structure fostered nepotism and cronyism among its commanders, who laid the seeds of regional warlordism in the first half of the 20th century.

Arts and Culture

Under the Qing, traditional forms of art flourished and innovations developed rapidly. High levels of literacy, a successful publishing industry, prosperous cities, and the Confucian emphasis on cultivation all fed a lively and creative set of cultural fields.

The Qing emperors were generally adept at poetry, often skilled in painting, and offered their patronage to Confucian culture. The Kangxi and Qianlong emperors, for instance, embraced Chinese traditions both to control the people and proclaim their own legitimacy. Imperial patronage encouraged literary and fine arts as well as the industrial production of ceramics and Chinese export porcelain. However, the most impressive aesthetic works were by the scholars and urban elite. Calligraphy and painting remained a central interest to both court painters and scholar-gentry who considered the arts part of their cultural identity and social standing.

Literature grew to new heights in the Qing period. Poetry continued as a mark of the cultivated gentleman, but women wrote in larger numbers and poets came from all walks of life. The poetry of the Qing dynasty is a field studied (along with the poetry of the Ming dynasty) for its association with Chinese opera, developmental trends of classical Chinese poetry, the transition to a greater role for vernacular language, and poetry by women in Chinese culture. In drama, the most prestigious form became the so-called Peking opera, although local and folk opera were also widely popular. Even cuisine became a form of artistic expression. Works that detailed the culinary aesthetics and theory, along with a wide range of recipes, were published.

A full-page delicate gouache painting showing the daily life of family of the officials in the Qing Dynasty. The image is bordered by a bright blue silk ribbon.

The Qing emperors generously supported the arts and sciences. For example, the Kangxi Emperor sponsored the Peiwen Yunfu, a rhyme dictionary published in 1711, and the Kangxi Dictionary published in 1716, which remains to this day an authoritative reference. The Qianlong Emperor sponsored the largest collection of writings in Chinese history, the Siku Quanshu, completed in 1782. Court painters made new versions of the Song masterpiece, Zhang Zeduan’s Along the River During the Qingming Festival, whose depiction of a prosperous and happy realm demonstrated the beneficence of the emperor.

By the end of the 19th century, all elements of national artistic and cultural life recognized and began to come to terms with world culture as found in the West and Japan. Whether to stay within old forms or welcome Western models was now a conscious choice rather than an unchallenged acceptance of tradition.

27.1.3: The Qing Dynasty and the West

The Qing dynasty tightly controlled its relations with Western governments by carefully limiting European states’ access to the Chinese market and establishing foreign relations based on traditions that emphasized the superiority of China.

Learning Objective

Examine the early interactions between the Qing and Western governments

Key Points

-

The

imperial Chinese tributary system was the network of trade and foreign

relations between China and its tributaries. It consisted almost entirely of mutually beneficial economic

relationships; member states were politically autonomous and usually independent. This system was the primary instrument of

diplomatic exchange throughout the Imperial Era. While most member states of

the system during the Qing rule were smaller Asian states, Great

Britain, the Netherlands, and Portugal sent tributes to China at the

time. -

British

ships began to appear sporadically around the coasts of China from 1635. However, trade began to flourish after the Qing dynasty

relaxed maritime trade restrictions in the 1680s and after Taiwan came under

Qing control in 1683. Even rhetoric regarding the tributary status of Europeans

was muted. Official British trade was conducted through the auspices of the

British East India Company, which gradually came to dominate Sino-European

trade from its position in India. -

From 1700–1842, the port of Guangzhou (Canton) came to dominate maritime

trade with China, and this period became known as the Canton System. From the

inception of the Canton System in 1757, goods from China were extremely

lucrative for European and Chinese merchants alike. However, foreign traders

were only permitted to do business through a body of Chinese merchants known as

the Cohong and were restricted to Canton. -

While silk and porcelain drove trade through

their popularity in the west, an insatiable demand for tea existed in Britain.

However, only silver was accepted in payment by China, which resulted in a

chronic trade deficit. Britain had been on the gold standard since the

18th century, so it had to purchase silver from continental Europe and Mexico. By 1817, the British realized they

could reduce the trade deficit and make the Indian colony profitable by

counter-trading in narcotic Indian opium, a critical decision for China’s future relations with the West. -

An issue facing Western embassies to China was

the act of prostration known as the kowtow. Western diplomats understood that

kowtowing meant accepting the superiority of the Emperor of China over their

own monarchs, an act they found unacceptable. Unlike other European partners, China

did not deal with Russia through the Ministry of Tributary Affairs, but rather

through the same ministry as the Mongols, seen by the Chinese as a problematic

partner. -

The

Chinese worldview changed very little during the Qing dynasty as China’s

sinocentric perspectives continued to be informed and reinforced by deliberate

policies and practices designed to minimize evidence of its growing

weakness and West’s evolving power. However, the

consequences of the Opium Wars would change everything.

Key Terms

- The imperial Chinese tributary system

-

The network of trade and foreign relations between China and its tributaries, which helped to shape much of East Asian affairs. It consisted almost entirely of mutually beneficial economic relationships, with politically autonomous and usually independent member states. It facilitated frequent economic and cultural exchange.

- kowtow

-

The act of deep respect shown by prostration: kneeling and bowing so low as to have one’s head touching the ground. In East Asian culture, it is the highest sign of reverence and is widely used for one’s elders, superiors, and especially the emperor, as well as for religious and cultural objects of worship.

- Opium Wars

-

Two wars in the mid-19th century

(1839–1842 and 1856–1860)involving Anglo-Chinese disputes over British trade in China and China’s sovereignty. The wars and events between them weakened the Qing dynasty and forced China to trade with the rest of the world.

- British East India Company

-

An English and later British joint-stock company formed to pursue trade with the East Indies but in actuality trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and Qing China.

Imperial Chinese Tributary System

The imperial Chinese tributary system was the network of trade and foreign relations between China and its tributaries, which helped to shape much of East Asian affairs. Contrary to other tribute systems around the world, the Chinese system consisted almost entirely of mutually beneficial economic relationships. Member states of the system were politically autonomous and usually independent. The system shaped foreign policy and trade for over 2,000 years of imperial China’s economic and cultural dominance of the region and thus played a huge role in the history of Asia, particularly East Asia.

The tributary system was the primary instrument of diplomatic exchange throughout the Imperial Era. While most member states of the system during the Qing rule were smaller Asian states , Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Portugal also sent tributes to China.

European Trade with Qing China

British ships began to appear sporadically around the coasts of China from 1635. Without establishing formal relations through the tributary system, British merchants were allowed to trade at the ports of Zhoushan and Xiamen in addition to Guangzhou (Canton). However, trade began to flourish after the Qing dynasty relaxed maritime trade restrictions in the 1680s and after Taiwan came under Qing control in 1683. Even rhetoric about the tributary status of Europeans was muted.

Official British trade was conducted through the auspices of the British East India Company, which held a royal charter for trade with the Far East. The British East India Company gradually came to dominate Sino-European trade from its position in India.

Guangzhou (Canton) was the port of preference for most foreign trade. From 1700–1842, Guangzhou came to dominate maritime trade with China, and this period became known as the Canton System. From the inception of the Canton System in 1757, trade in goods from China was extremely lucrative for European and Chinese merchants alike. However, foreign traders were only permitted to do business through a body of Chinese merchants known as the Cohong and were restricted to Canton. Foreigners could only live in one of the Thirteen Factories,

a neighborhood along the Pearl River in southwestern Guangzhou, and were not allowed to enter, much less live or trade in, any other part of China.

While silk and porcelain drove trade through popularity in the west, an insatiable demand for tea existed in Britain. However, only silver was accepted in payment by China, which resulted in a chronic trade deficit. From the mid-17th century, around 28 million kilograms of silver were received by China, principally from European powers, in exchange for Chinese goods. Britain had been on the gold standard since the 18th century, so it had to purchase silver from continental Europe and Mexico to supply the Chinese appetite for silver. Attempts at the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th centuries by a British embassy (twice), a Dutch mission, and Russia to negotiate more expansive access to the Chinese market were all vetoed by successive Emperors. By 1817, the British realized they could reduce the trade deficit and turn the Indian colony profitable by counter-trading in narcotic Indian opium. The Qing administration initially tolerated opium importation because it created an indirect tax on Chinese subjects while allowing the British to double tea exports from China to England, thereby profiting the monopoly on tea exports held by the Qing imperial treasury and its agents. The increasingly complex opium trade would eventually become a source of a military conflict between the Qing dynasty and Britain (Opium Wars).

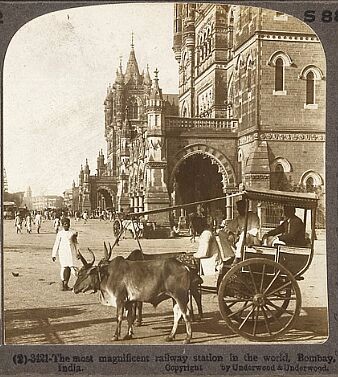

View of the European factories in Canton by William Daniell, late 18th/early 19th century,

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

Canton City (Guangzhou), with the Pearl River and the several of the Thirteen Factories of the Europeans.

These warehouses and stores were the principal and sole legal site of most Western trade with China from 1757 to 1842.

Foreign Relations

An issue facing Western embassies to China was the act of prostration known as the kowtow. Western diplomats understood that kowtowing meant accepting the superiority of the Emperor of China over their own monarchs, an act they found unacceptable.

The British embassies of George Macartney (1793) and William Pitt Amherst (1816) were unsuccessful at negotiating the expansion of trade and interstate relations, partly because kowtowing would mean acknowledging their king as a subject of the Emperor. Dutch ambassador Isaac Titsingh did not refuse to kowtow during the course of his 1794–1795 mission to the imperial court of the Qianlong Emperor. The members of the Titsingh mission made every effort to conform with the demands of complex Imperial court etiquette.

In 1665, Russian explorers met the Manchus in present-day northeastern China. Using the common language of Latin, which the Chinese knew from Jesuit missionaries, the Kangxi Emperor of China and Tsar Peter I of the Russian Empire negotiated the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689. This delineated the borders between Russia and China, some sections of which still exist today. China did not deal with Russia through the Ministry of Tributary Affairs, but rather through the same ministry as the Mongols (seen by the Chinese as a problematic partner), which served to acknowledge Russia’s status as a nontributary nation.

Canton Harbor and Factories with Foreign Flags, unknown Chinese artists, c. 1805, Peabody Essex Museum.

Under the Canton System, between 1757 and 1842, Western merchants in China were restricted to live and conduct business only in the approved area of the port of Guangzhou and through a government-approved merchant houses. Their factories formed a tight-knit community, which the historian Jacques Downs called a “golden ghetto” because it was both isolated and lucrative.

The Chinese worldview changed very little during the Qing dynasty as China’s sinocentric perspectives continued to be informed and reinforced by deliberate policies and practices designed to minimize evidence of its growing weakness and West’s evolving power. After the Titsingh mission, no further non-Asian ambassadors were even allowed to approach the Qing capital until the consequences of the Opium Wars changed everything.

27.1.4: The Opium Wars

The Opium Wars

undermined China’s traditional mechanisms of foreign relations and controlled trade. This made it possible for Western powers, particularly Britain, to exercise influence over China’s economy and diplomatic relations.

Learning Objective

Evaluate the Opium Wars and the motivations of the imperial powers in bringing opium to China

Key Points

- After the British gained control over the Bengal Presidency in the mid-18th century, the former monopoly on opium production held by the Mughal emperors passed to the East India Company. To redress the trade imbalance with China, the EIC began auctions of opium in Calcutta and saw its profits soar from the opium trade. Since importation of opium into China had been virtually banned, the EIC established a complex trading scheme of both legal and illicit markets.

-

A porous Chinese border and rampant

local demand facilitated trade. By the 1820s, China was importing 900

long tons of Bengali opium annually. In

addition to the drain of silver, by 1838 the number of Chinese opium addicts

had grown to between four and 12 million and the Daoguang Emperor demanded

action. -

The Emperor sent the leader of the hard line

faction, Special Imperial Commissioner Lin Zexu, to Canton, where he quickly

arrested Chinese opium dealers and summarily demanded that foreign firms turn

over their stocks with no compensation. When they refused, Lin stopped trade

altogether and placed the foreign residents under virtual siege in their

factories. - The First Opium War over the trade and diplomatic relations between Imperial China and Britain began in 1839. It quickly revealed the outdated state of the Chinese military. The Qing surrender

in 1842 marked a decisive, humiliating blow to China. The Treaty of Nanking

demanded war reparations and forced China to open up the Treaty Ports of Canton,

Amoy, Fuchow, Ningpo, and Shanghai to western trade and missionaries and cede Hong Kong Island to Britain. - The Second Opium War, triggered by further British demands, began in 1856 and ended with the 1860 Convention of Beijing. The

British, French, and Russians were all granted a permanent diplomatic

presence in Beijing. The Chinese had to

pay 8 million taels to Britain and France. Britain acquired Kowloon, next to Hong Kong. The opium trade was legalized and Christians were granted

full civil rights, including the right to own property and to

evangelize. The treaty also ceded parts of Outer Manchuria to the Russian

Empire. -

The

terms of the treaties ending the Opium Wars undermined China’s traditional

mechanisms of foreign relations and methods of controlled trade. More ports

were opened for trade and Hong Kong was seized by

the British to become a free and open port. Tariffs were abolished, preventing the Chinese from raising future duties to protect domestic

industries, and extraterritorial practices exempted Westerners from Chinese law.

In 1858, opium was legalized. The Qing dynasty never recovered from the defeat and the Western powers exercised more and more control over Imperial China.

Key Terms

- Treaty of Nanjing

-

A peace treaty that ended the First Opium War (1839–42) between the United Kingdom and the Qing dynasty of China, signed in August 1842.

It ended the old Canton System and created a new framework for China’s foreign relations and overseas trade that would last for almost 100 years. From the Chinese perspective, the most injurious terms were the fixed trade tariff, extraterritoriality, and the most favored nation provisions. It was the first of what the Chinese later called the unequal treaties in which Britain had no obligations in return. - Treaty of Tientsin

-

A collective name for several documents signed in 1858 that ended the first phase of the Second Opium War. The Qing, Russian, and Second French Empires, the United Kingdom, and the United States were the parties involved. These unequal treaties opened more Chinese ports to foreign trade, permitted foreign legations in the Chinese capital Beijing, allowed Christian missionary activity, and legalized the import of opium. They were ratified by the Emperor of China in the Convention of Peking in 1860 after the end of the war.

- East India Company

-

An English and later British joint-stock

company formed to pursue trade with the East Indies but in actuality trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and Qing China. - Century of Humiliation

-

The period of intervention and imperialism by Western powers and Japan in China between 1839 and 1949. It arose in 1915 in the atmosphere of increased Chinese nationalism.

- Convention of Beijing

-

An agreement comprising three distinct treaties between the Qing Empire (China) and the United Kingdom, France, and Russia in 1860, which ended the Second Opium War.

- Second Opium War

-

A war pitting the British Empire and the French Empire against the Qing dynasty of China, lasting from 1856 to 1860.

- First Opium War

-

An 1839–1842 war fought between the United Kingdom and the Qing dynasty over their conflicting viewpoints on diplomatic relations, trade, and the administration of justice for foreign nationals in China.

Opium Trade in China

The history of opium in China began with the use of opium for medicinal purposes during the 7th century. In the 17th century, the practice of mixing opium with tobacco for smoking spread from Southeast Asia, creating a far greater demand.

After the British gained control over the Bengal Presidency, the largest colonial subdivision of British India, in the mid-18th century, the former monopoly on opium production held by the Mughal emperors passed to the East India Company (EIC) under the The East India Company Act, 1793. However, the EIC was £28 million in debt, partly as a result of the insatiable demand for Chinese tea in the UK market. Chinese tea had to be paid for in silver, so silver supplies had to be purchased from continental Europe and Mexico. To redress the imbalance, the EIC began auctions of opium in Calcutta and saw its profits soar from the opium trade. Considering that importation of opium into China had been virtually banned by Chinese law, the EIC established an elaborate trading scheme, partially relying on legal markets and partially leveraging illicit ones. British merchants bought tea in Canton on credit and balanced their debts by selling opium at auction in Calcutta. From there, the opium would reach the Chinese coast hidden aboard British ships and was smuggled into China by native merchants.

In 1797, the EIC further tightened its grip on the opium trade by enforcing direct trade between opium farmers and the British and ending the role of Bengali purchasing agents. British exports of opium to China grew from an estimated 15 long tons in 1730 to 75 long tons in 1773 shipped in over 2,000 chests. The Qing dynasty Jiaqing Emperor issued an imperial decree banning imports of the drug in 1799. Nevertheless, by 1804, the British trade deficit with China turned into a surplus, leading to seven million silver dollars going to India between 1806 and 1809. Meanwhile, Americans entered the opium trade with less expensive but inferior Turkish opium and by 1810 had around 10% of the trade in Canton.

In the same year the emperor issued a further imperial edict prohibiting the use and trade of opium. The decree had little effect. The Qing government, far away in Beijing in the north of China, was unable to halt opium smuggling in the southern provinces. A porous Chinese border and rampant local demand facilitated the trade and by the 1820s, China was importing 900 long tons of Bengali opium annually. The opium trafficked into China was processed by the EIC at its two factories in Patna and Benares. In the 1820s, opium from Malwa in the non-British controlled part of India became available and as prices fell due to competition, production was stepped up.

In addition to the drain of silver, by 1838 the number of Chinese opium addicts had grown to between four and 12 million and the Daoguang Emperor demanded action. Officials at the court who advocated legalizing and taxing the trade were defeated by those who advocated suppressing it. The Emperor sent the leader of the hard line faction, Special Imperial Commissioner Lin Zexu, to Canton, where he quickly arrested Chinese opium dealers and summarily demanded that foreign firms turn over their stocks with no compensation. When they refused, Lin stopped trade altogether and placed the foreign residents under virtual siege in their factories. The British Superintendent of Trade in China Charles Elliot got the British traders to agree to hand over their opium stock with the promise of eventual compensation for their loss from the British government. While this amounted to a tacit acknowledgment that the British government did not disapprove of the trade, it also placed a huge liability on the exchequer. This promise and the inability of the British government to pay it without causing a political storm was an important casus belli for the subsequent British offensive.

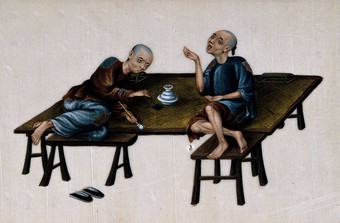

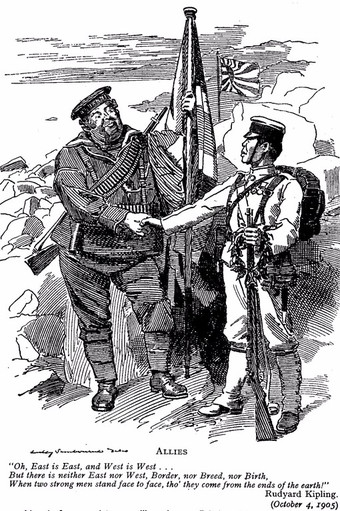

Two poor Chinese opium smokers. Gouache painting on rice-paper, 19th century.

Initially used by medical practitioners to control bodily fluid and preserve qi or vital force, during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), opium also functioned as an aphrodisiac. First listed as a taxable commodity in 1589, opium remained legal until the early Qing dynasty.

First Opium War

In October 1839, the Thomas Coutts arrived in China and sailed to Canton. The ship was owned by Quakers, who refused to deal in opium. The ship’s captain, Warner, believed Elliot had exceeded his legal authority by banning the signing of the “no opium trade” bond and negotiated with the governor of Canton, hoping that all British ships could unload their goods at Chuenpi, an island near Humen. To prevent other British ships from following the Thomas Coutts, Elliot ordered a blockade of the Pearl River. Fighting began on November 3, 1839, when a second British ship, the Royal Saxon, attempted to sail to Canton. Then the British Royal Navy ships HMS Volage and HMS Hyacinth fired warning shots at the Royal Saxon. The Qing navy’s official report claimed that the navy attempted to protect the British merchant vessel and reported a victory for that day. In reality, they had been overtaken by the Royal Naval vessels and many Chinese ships were sunk.

The First Opium War revealed the outdated state of the Chinese military. The Qing navy was severely outclassed by the modern tactics and firepower of the British Royal Navy. British soldiers, using advanced muskets and artillery, easily outmaneuvered and outgunned Qing forces in ground battles. The Qing surrender in 1842 marked a decisive, humiliating blow to China. The Treaty of Nanking demanded war reparations, forced China to open up the Treaty Ports of Canton, Amoy, Fuchow, Ningpo, and Shanghai to western trade and missionaries, and to cede Hong Kong Island to Britain. It revealed weaknesses in the Qing government and provoked rebellions against the regime.

Second Opium War

The 1850s saw the rapid growth of Western imperialism. Some shared goals of the western powers were the expansion of their overseas markets and the establishment of new ports of call. To expand their privileges in China, Britain demanded the Qing authorities renegotiate the 1842 Treaty of Nanking, citing their most favored nation status. The British demands included opening all of China to British merchant companies, legalizing the opium trade, exempting foreign imports from internal transit duties, suppression of piracy, regulation of the coolie trade, permission for a British ambassador to reside in Beijing, and for the English-language version of all treaties to take precedence over the Chinese language.

To give Chinese merchant vessels operating around treaty ports the same privileges accorded British ships by the Treaty of Nanking, British authorities granted these vessels British registration in Hong Kong. In October 1856, Chinese marines in Canton seized a cargo ship called the Arrow on suspicion of piracy, arresting 12 of its 14 Chinese crew members. The Arrow was previously used by pirates, captured by the Chinese government, and subsequently resold. It was then registered as a British ship and still flew the British flag at the time of its detainment, although its registration expired. Its captain, Thomas Kennedy, aboard a nearby vessel at the time, reported seeing Chinese marines pull the British flag down from the ship. The British consul in Canton, Harry Parkes, contacted Ye Mingchen, imperial commissioner and Viceroy of Liangguang, to demand the immediate release of the crew and an apology for the alleged insult to the flag. Ye released nine of the crew members, but refused to release the last three.

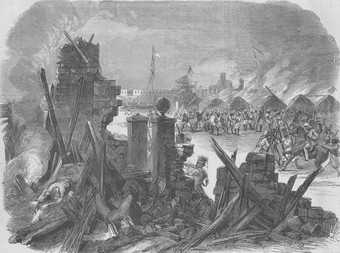

On October 25, the British demanded to enter Canton. The next day, they started to bombard the city, firing one shot every 10 minutes. Ye Mingchen issued a bounty on every British head taken. On October 29, a hole was blasted in the city walls and troops entered, with a flag of the United States of America being planted by James Keenan (U.S. Consul) on the walls and residence of Ye Mingchen. Negotiations failed, the city was bombarded, and the war escalated.

In 1858, with no other options, the Xianfeng Emperor agreed to the Treaty of Tientsin, which contained clauses deeply insulting to the Chinese, such as a demand that all official Chinese documents be written in English and a proviso granting British warships unlimited access to all navigable Chinese rivers. Shortly after the Qing imperial court agreed to the disadvantageous treaties, hawkish ministers prevailed upon the Xianfeng Emperor to resist Western encroachment, which led to a resumption of hostilities. In 1860, with Anglo-French forces marching on Beijing, the emperor and his court fled the capital for the imperial hunting lodge at Rehe. Once in Beijing, the Anglo-French forces looted the Old Summer Palace and, in an act of revenge for the arrest of several Englishmen, burnt it to the ground. Prince Gong, a younger half-brother of the emperor, was forced to sign the Convention of Beijing. The agreement comprised three distinct treaties concluded between the Qing Empire and the United Kingdom, France, and Russia (while Russia had not been a belligerent, it threatened weakened China with a war on a second front). The British, French, and Russians were granted a permanent diplomatic presence in Beijing, something the Qing Empire resisted to the very end as it suggested equality between China and the European powers. The Chinese had to pay 8 million taels to Britain and France. Britain acquired Kowloon (next to Hong Kong). The opium trade was legalized and Christians were granted full civil rights, including the right to own property and the right to evangelize. The treaty also ceded parts of Outer Manchuria to the Russian Empire.

Legacy

The First Opium War marked the start of what 20th century nationalists called the Century of Humiliation. The ease with which the British forces defeated the numerically superior Chinese armies damaged the Qing dynasty’s prestige. The Treaty of Nanking was a step to opening the lucrative Chinese market to global commerce and the opium trade.

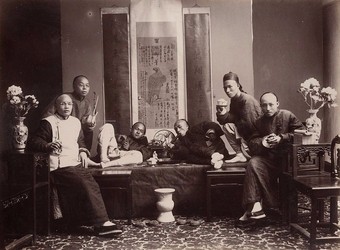

Opium smokers, c. 1880, by Lai Afong.

Historian Jonathan Spence notes that the harm opium caused was clear, but that in a stagnating economy, it supplied fluid capital and created new tax sources. Smugglers, poor farmers, coolies, retail merchants and officials all depended on opium for their livelihoods. In the last decade of the Qing dynasty, however, a focused moral outrage overcame these vested interests.

The terms of the treaties ending the Opium Wars undermined China’s traditional mechanisms of foreign relations and methods of controlled trade. More ports were opened for trade, gunboats, and foreign residence. Hong Kong was seized by the British to become a free and open port. Tariffs were abolished preventing the Chinese from raising future duties to protect domestic industries and extraterritorial practices exempted Westerners from Chinese law. This made them subject to their own civil and criminal laws of their home country. Most importantly, the opium problem was never addressed and after the treaty ending the First War was signed, opium addiction doubled. Due to the Qing government’s inability to control collection of taxes on imported goods, the British government convinced the Manchu court to allow Westerners to partake in government official affairs. In 1858 opium was legalized.

The First Opium War both reflected and contributed to a further weakening of the Chinese state’s power and legitimacy. Anti-Qing sentiment grew in the form of rebellions such as the Taiping Rebellion, a civil war lasting from 1850-64 in which at least 20 million Chinese died.

The opium trade faced intense enmity from the later British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone. As a member of Parliament, Gladstone called it “most infamous and atrocious,” referring to the opium trade between China and British India in particular. Gladstone was fiercely against both Opium Wars, denounced British violence against Chinese, and was ardently opposed to the British trade in opium to China. Gladstone criticized the First War as “unjust in its origin, a war more calculated in its progress to cover this country with permanent disgrace.” His hostility to opium stemmed from the effects of the drug on his sister Helen.

The standard interpretation in the People’s Republic of China presented the war as the beginning of modern China and the emergence of the Chinese people’s resistance to imperialism and feudalism.

27.1.5: Anti-Qing Sentiment

In the mid-19th century, China’s Qing Dynasty suffered a series of natural

disasters, economic problems, and defeats at the hands of the Western powers, which weakened the central imperial authority and led to a rapid development of anti-Qing movements.

Learning Objective

Paraphrase the reasons for rising Anti-Qing sentiment in China

Key Points

-

In the mid-19th century, China’s Qing Dynasty suffered a series

of natural disasters, economic problems, and defeats at the hands of the

Western powers. The terms of the treaties that ended the lost First Opium

War undermined the traditional mechanisms of foreign relations and methods

of controlled trade practiced by China for centuries. Shortly after the

treaties were signed, internal rebellions began to threaten the Chinese state

and its foreign trade. -

The government, led by ethnic Manchus, was seen by many Han

Chinese as ineffective and corrupt. Anti-Manchu sentiment was strongest in southern China among the Hakka community, a Han Chinese

subgroup. The Qing dynasty was blamed for transforming China from the world’s

premiere power to a poor, backwards country. In the broadest sense, an

anti-Qing activist was anyone who engaged in anti-Manchu direct action. -

While the Taiping Rebellion was not the first mass expression of

the anti-Qing sentiment, it turned into a long civil war

that cost millions of lives. It lasted from 1850 to 1864 and was fought between

the Qing dynasty and the millenarian movement of the Heavenly Kingdom

of Peace. It was the largest war in China since the Qing conquest in 1644 and

ranks as one of the bloodiest wars in human history, the bloodiest civil war,

and the largest conflict of the 19th century. -

A string of civil disturbances followed, including the Punti-Hakka

Clan Wars, Nian Rebellion, Dungan Revolt, and Panthay Rebellion. All rebellions

were ultimately put down, but at enormous cost and with millions dead,

seriously weakening the central imperial authority and introducing changes in

the military that would further undermine the influence of the Qing dynasty. -

In response to calamities within the empire and threats from

imperialism, some reformist movements emerged, but were undermined by

corrupt officials, cynicism, and quarrels within the imperial family. The

anti-Qing sentiment only strengthened as the internal chaos and foreign

influences grew.

Key Terms

- Nian Rebellion

-

An armed uprising in northern China from 1851 to 1868, concurrent with the Taiping Rebellion (1851–1864) in South China. The rebellion failed to topple the Qing dynasty, but caused the immense economic devastation and loss of life that became one of the major long-term factors in the collapse of the Qing regime in the early 20th century.

- Taiping Rebellion

-

A civil war in China (1850-1864) between the established Manchu-led Qing dynasty and the millenarian movement of the Heavenly Kingdom of Peace. It began in the southern province of Guangxi when local officials launched a campaign of persecution against a millenarian sect known as the God Worshipping Society led by Hong Xiuquan, who believed himself the younger brother of Jesus Christ. The war ranks as one of the bloodiest wars in human history, the bloodiest civil war, and the largest conflict of the 19th century.

- First Opium War

-

An 1839–1842 war between the

United Kingdom and the Qing dynasty over their conflicting viewpoints

on diplomatic relations, trade, and the administration of justice for foreign

nationals in China. - Panthay Rebellion

-

An 1856-1873 rebellion of the Muslim Hui people and other non-Muslim ethnic minorities against the Manchu rulers in southwestern Yunnan Province, China, as part of a wave of Hui-led multi-ethnic unrest. It started after massacres of Hui perpetrated by the Manchu authorities.

- Dungan Revolt

-

A mainly ethnic and religious war fought in 19th-century western China, mostly during the reign of the Tongzhi Emperor (r. 1861–75) of the Qing dynasty. The term sometimes includes the Panthay Rebellion in Yunnan, which occurred during the same period. The 1862-1877 revolt arose over a pricing dispute involving bamboo poles, when a Han merchant selling to a Hui did not receive the amount demanded for the goods.

- Punti-Hakka Clan Wars

-

The conflict between the Hakka and Punti (Cantonese people) in Guangdong, China, between 1855 and 1867. The wars were particularly fierce around the Pearl River Delta, especially in Taishan of the Sze Yup counties. They resulted in roughly a million dead with many more fleeing for their lives.

- millenarianism

-

The belief by a religious, social, or political group or movement in a major impending societal transformation. It is a concept or theme that exists in many cultures and religions.

In the mid-19th century, China’s Qing Dynasty suffered a series of natural disasters, economic problems, and defeats at the hands of the Western powers. In particular, the humiliating defeat in 1842 by the British Empire in the First Opium War exposed the increasing weakness of the Imperial government and military. The terms of the treaties that ended the First Opium War undermined the traditional mechanisms of foreign relations and methods of controlled trade practiced by China for centuries. Shortly after the treaties were signed, internal rebellions began to threaten the Chinese state and its foreign trade.

The government, led by ethnic Manchus, was seen by many Han Chinese as ineffective and corrupt. Anti-Manchu sentiments were strongest in southern China among the Hakka community, a Han Chinese subgroup.

The Qing dynasty was accused of destroying traditional Han culture by forcing Han to wear their hair in a queue in the Manchu style. It was blamed for suppressing Chinese science, causing China to be transformed from the world’s premiere power to a poor, backwards country.

In the broadest sense, an anti-Qing activist was anyone who engaged in anti-Manchu direct action. This included people from many mainstream political movements and uprisings that developed throughout the second half of the 19th century.

Taiping Rebellion

While the Taiping Rebellion was not the first mass expression of the anti-Qing sentiment, it turned into a long-lasting civil war that cost millions of lives. In 1837, Hong Xiuquan, a Hakka from a poor mountain village, once again failed the imperial examination, which meant that he could not follow his dream of becoming a scholar-official in the civil service. He returned home, fell sick, and was bedridden for several days, during which he experienced mystical visions. In 1842, after more carefully reading a pamphlet he had received years before from a Protestant Christian missionary, Hong declared that he now understood that his vision meant that he was the younger brother of Jesus and that he had been sent to rid China of the “devils,” including the corrupt Qing government and Confucian teachings. It was his duty to spread his message and overthrow the Qing dynasty. In 1843, Hong and his followers founded the God Worshiping Society, a movement that combined elements of Christianity, Taoism, Confucianism, and indigenous millenarianism. Confucianism due to the efforts of the various Chinese dynastic imperial regimes. The movement at first grew by suppressing groups of bandits and pirates in southern China in the late 1840s. The later suppression by Qing authorities led it to evolve into guerrilla warfare and subsequently a widespread civil war.

Hostilities began on January 1, 1851 when the Qing Green Standard Army launched an attack against the God Worshiping Society at the town of Jintian, Guangxi. Hong declared himself the Heavenly King of the Heavenly Kingdom of Peace (or Taiping Heavenly Kingdom), from which the term Taipings has often been applied to them in the English language. For a decade, the Taiping occupied and fought across much of the mid and lower Yangzi valley, some of the wealthiest and most productive lands in the Qing empire. The Taiping nearly managed to capture the Qing capital of Beijing with a northern expedition launched in 1853. Qing imperial troops were ineffective in halting Taiping advances, focusing on a perpetually stalemated siege of Nanjing. In Hunan Province, a local irregular army, called the Xiang Army or Hunan Army, under the personal leadership of Zeng Guofan, became the main armed force fighting for the Qing against the Taiping. Zeng’s Xiang Army gradually turned back the Taiping advance in the western theater of the war.

In 1856, the Taiping were weakened after infighting following an attempted coup led by the East King, Yang Xiuqing. During this time, the Xiang Army managed to gradually retake much of Hubei and Jiangxi province. In 1860, the Taiping defeated the imperial forces that had been besieging Nanjing since 1853, eliminating imperial forces from the region and opening the way for a successful invasion of southern Jiangsu and Zhejiang province, the wealthiest region of the Qing Empire. While Taiping forces were preoccupied in Jiangsu, Zeng’s forces moved down the Yangzi River capturing Anqing in 1861.

In 1862, the Xiang Army began directly sieging Nanjing and managed to hold firm despite numerous attempts by the Taiping Army to dislodge them with superior numbers. Hong died in 1864 and Nanjing fell shortly after that. The remains of the Taiping resistance were eventually defeated in 1866.

A drawing of Hong Xiuquan as the Heavenly King, ca. 1860

The Taiping Rebellion was a total war. Almost every citizen of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom was given military training and conscripted into the army to fight against Qing imperial forces. During this conflict, both sides tried to deprive each other of the resources needed to continue the war and it became standard practice to destroy agricultural areas, butcher the population of cities, and exact a brutal price from captured enemy lands to drastically weaken the opposition’s war effort.

The Taiping Rebellion was the largest war in China since the Qing conquest in 1644 and ranks as one of the bloodiest wars in human history, the bloodiest civil war, and the largest conflict of the 19th century, with estimates of war dead ranging from 20 to 100 million and millions more displaced.

Continuous Crisis

A string of civil disturbances followed the outbreak of Taiping Rebellion, many of which lasted for years and resulted in massive casualties. For instance, the Punti-Hakka Clan Wars pitted the Hakka against Punti (Cantonese people) in Guangdong between 1855 and 1867. The wars resulted in roughly a million dead with many more fleeing for their lives.

The Nian Rebellion was an armed uprising that took place in northern China from 1851 to 1868, contemporaneously with the Taiping Rebellion in southern China. The rebellion caused immense economic devastation and loss of life that eventually became one of the major long-term factors in the collapse of the Qing regime in the early 20th century.

The Dungan Revolt (1862–1877) was a mainly ethnic and religious war fought in western China. The revolt arose over a pricing dispute involving bamboo poles, when a Han merchant selling to a Hui did not receive the amount demanded for the goods. Up to 12 million Chinese Muslims were killed during the revolt as a result of anti-Hui massacres by Qing troops sent to suppress their revolt.

Most civilian deaths were caused by war-induced faneil.

The Panthay Rebellion (1856-1873; discussed sometimes as part of the Dungan Revolt)

was a rebellion of the Muslim Hui people and other non-Muslim ethnic minorities against the Manchu rulers in southwestern Yunnan Province as part of a wave of Hui-led multi-ethnic unrest. It started after massacres of Hui perpetrated by the Manchu authorities.

All rebellions were ultimately put down, but at enormous cost and with millions dead, seriously weakening the central imperial authority. The military banner system that the Manchus had relied upon for so long failed. Banner forces were unable to suppress the rebels and the government called upon local officials in the provinces, who raised “New Armies” that successfully crushed the challenges to Qing authority. As a result of that and with China failing to rebuild a strong central army, many local officials became warlords who used military power to effectively rule independently in their provinces.

General Zeng Guofan, author unknown, scan from Jonathan Spence, In Search for Modern China, 1990.

Zeng Guofan’s strategy to fight anti-Qing rebels was to rely on local gentry to raise a new type of military organization. This new force became known as the Xiang Army, a hybrid of local militia and a standing army. The army’s professional training was paid for out of regional coffers and funds its commanders – mostly members of the Chinese gentry – could muster. This model would eventually lead to the further weakening of the central authority over the military.

In response to calamities within the empire and threats from imperialism, the Self-Strengthening Movement emerged. This institutional reform in the second half of the 19th century aimed to modernize the empire, with prime emphasis on strengthening the military. However, the reform was undermined by corrupt officials, cynicism, and quarrels within the imperial family. The Guangxu Emperor and the reformists then launched a more comprehensive reform effort, the Hundred Days’ Reform (1898), but it was soon overturned by the conservatives under Empress Dowager Cixi in a military coup. The anti-Qing sentiment only strengthened as the internal chaos and foreign influences grew, finally leading to the Boxer Rebellion, a violent

anti-foreign and anti-Christian uprising that was a turning point in the history of Imperial China.

27.1.6: The Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, a violent anti-foreign and anti-Christian uprising that took place in China between 1899 and 1901, both exposed and deepened the weakening of the Qing dynasty’s power.

Learning Objective

Discuss the reasons for and consequences of the Boxer Rebellion

Key Points

-

The Righteous and

Harmonious Fists (Yihetuan) arose in the inland sections of the northern

coastal province of Shandong long known for social unrest, religious sects, and

martial societies. American Christian missionaries were probably the first to

refer to the well-trained young men as Boxers because of the martial

arts they practiced. The excitement and moral

force of the group’s rituals were especially attractive to unemployed and

powerless village men. -

International tension and

domestic unrest fueled the spread of the Boxer movement. A drought

followed by floods in Shandong province in 1897–1898 forced farmers to flee to

cities and seek food. Another major cause of discontent in north China was Christian missionary activity. The killing of two German missionaries in 1897 prompted Germany to occupy

Jiaozhou Bay, which triggered a scramble for concessions by which Britain, France, Russia, and

Japan also secured their own spheres of influence in China. -

The

early growth of the Boxer movement coincided with the Hundred Days’ Reform

(June 11 – September 21, 1898). The Guangxu Emperor’s progressive reforms alienated many conservative officials. The opposition from conservative officials led Empress Dowager Cixi to

intervene and reverse the reforms. The failure of the reform movement

disillusioned many educated Chinese and thus further weakened the Qing

government. -

In January 1900, Empress Dowager Cixi issued edicts in the Boxers’

defense, causing protests from foreign powers. The Boxer movement spread

rapidly. After several months of

growing violence against both the foreign and Christian presence in

Shandong and the North China plain in June 1900, Boxer fighters converged on Beijing.

Foreigners and Chinese Christians sought refuge in the Legation Quarter. The

Eight-Nation Alliance sent the Seymour Expedition to relieve the

siege. The Expedition was stopped by the Boxers at the Battle of

Langfang and forced to retreat. - The Alliance’s attack on the Dagu

Forts led the Qing government and the initially

hesitant Empress Dowager Cixi to side with and support the Boxers. On June 21, 1900, she

issued an Imperial Decree officially declaring war on the foreign powers. The

Alliance formed the second, much larger Gaselee Expedition and finally

reached Beijing. The Qing government evacuated to Xi’an. The

Boxer Protocol ended the war. - As a result of the rebellion, the European powers

ceased their ambitions to colonize China. Concurrently, this period

marks the ceding of European great power interference in Chinese affairs, with

the Japanese replacing the Europeans as the dominant power.

Empress

Dowager Cixi reluctantly started reforms known as the New Policies despite her previous views. The question of the historical interpretation of the rebellion remains controversial.

Key Terms

- Boxer Protocol

-

A treaty signed on September 7, 1901, between the Qing Empire of China and the Eight-Nation Alliance that provided military forces (Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States) plus Belgium, Spain, and the Netherlands, which ended the Boxer Rebellion. It provided for the execution of government officials who supported the Boxers, foreign troops to be stationed in Beijing, and 450 million taels of silver to be paid as indemnity over the next 39 years to the eight nations involved.

- Hundred Days’ Reform

-

A failed 103-day national cultural, political, and educational reform movement from June 11 to September 21, 1898 in late Qing dynasty China. It was undertaken by the young Guangxu Emperor and his reform-minded supporters. The movement was short-lived, ending in a coup d’état by powerful conservative opponents led by Empress Dowager Cixi.

- Boxer Rebellion

-

A violent anti-foreign and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, toward the end of the Qing dynasty. It was initiated by the Militia United in Righteousness (Yihetuan), known in English as the Boxers, and was motivated by proto-nationalist sentiments and opposition to imperialist expansion and associated Christian missionary activity.

- Boxers

-

A martial society, known as the Militia United in Righteousness (Yihetuan), motivated by proto-nationalist sentiments and opposition to imperialist expansion and associated Christian missionary activity in China at the end of the 19th century. Its members practiced martial arts and claimed supernatural invulnerability towards Western weaponry. They believed that millions of soldiers of Heaven would descend to purify China of foreign oppression, a belief characteristic of millenarian movements.

- Seymour Expedition

-

An attempt by a multi-national military force to march to Beijing and protect the diplomatic legations and foreign nationals in the city from attacks by Boxers in 1900. The Chinese army forced it to return to Tianjin (Tientsin).

- New Policies

-