22.1: France under Louis XV

22.1.1: Catherine’s Foreign Policy Goals

During Catherine the Great’s reign, Russia significantly extended its borders by absorbing new territories, most notably from the Ottoman Empires and the Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania, as well as

attempted to serve as an international mediator in disputes that could, or did, lead to war.

Learning Objective

Describe Catherine the Great’s foreign policy efforts and to what extent she achieved her goals

Key Points

-

During her reign, Catherine extended the borders

of the Russian Empire southward and westward to absorb New Russia, Crimea, Northern Caucasus,

Right-bank Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, and Courland at the expense, mainly, of

two powers – the Ottoman Empire and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Under

her rule, some 200,000 square miles (520,000 km2)

were added to Russian territory. -

Catherine made Russia the dominant power in

south-eastern Europe after her first Russo-Turkish War against the Ottoman

Empire (1768–74), which saw some of the heaviest defeats in Ottoman history.

In

1786, Catherine conducted a triumphal procession in the Crimea, which helped

provoke the next Russo–Turkish War. This war, catastrophic for the Ottomans,

legitimized the Russian claim to

the Crimea. -

Catherine’s triumph in Crimea is linked to a

concept of Potemkin villages. In politics and economics, Potemkin villages

refer to any construction (literal or figurative) built solely to deceive

others into thinking that a situation is better than it really is. -

Although the idea of partitioning the Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania came from Frederick the Great of Prussia, Catherine took a leading role

in carrying it out (in three separate partitions of 1772, 1793, and 1795).

Russia

completed the partitioning of Poland-Lithuania with Prussia and Austria and the Commonwealth ceased to exist as an independent state. -

Catherine longed for recognition as an

enlightened sovereign. She pioneered for Russia the role that Britain later

played through most of the 19th and early 20th centuries as an international

mediator in disputes that could, or did, lead to war. - In

1780, she established a League of Armed Neutrality, designed to defend neutral

shipping from the British Royal Navy during the American Revolution. After

establishing a league of neutral parties, Catherine the Great attempted to act

as a mediator between the United States and Britain by submitting a ceasefire

plan.

Key Terms

- Potemkin villages

-

In politics and economics, a term referring to any construction (literal or figurative) built solely to deceive others into thinking that a situation is better than it really is. The term comes from stories of a fake portable village, supposedly built only to impress Empress Catherine II during her journey to Crimea in 1787.

- the Confederation of Bar

-

An association of Polish nobles formed at the fortress of Bar in Podolia in 1768 to defend the internal and external independence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth against Russian influence and against King Stanisław II Augustus with Polish reformers, who were attempting to limit the power of the Commonwealth’s wealthy magnates. Its creation led to a civil war and contributed to the First Partition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

- League of Armed Neutrality

-

An alliance of European naval powers between 1780 and 1783, which was intended to protect neutral shipping against the Royal Navy’s wartime policy of unlimited search of neutral shipping for French contraband.

Empress Catherine the Great of Russia began the first League with her declaration of Russian armed neutrality in 1780, during the War of American Independence. She endorsed the right of neutral countries to trade by sea with nationals of belligerent countries without hindrance, except in weapons and military supplies. - Treaty of Jassy

-

A 1792 peace treaty signed at Jassy in Moldavia (presently in Romania) by the Russian and Ottoman Empires that ended the Russo-Turkish War of 1787–92 and confirmed Russia’s increasing dominance in the Black Sea. The treaty formally recognized the Russian Empire’s annexation of the Crimean Khanate via the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca of 1783 and transferred Yedisan (the territory between Dniester and Bug rivers) to Russia making the Dniester the Russo-Turkish frontier in Europe and leaving the Asiatic frontier (Kuban River) unchanged.

- Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca

-

A 1774 peace treaty signed in Küçük Kaynarca (today Kaynardzha, Bulgaria) between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire. Following the recent Ottoman defeat at the Battle of Kozludzha, the document ended the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–74 and marked a defeat of the Ottomans in their struggle against Russia.

- the Targowica Confederation

-

A confederation established by Polish and Lithuanian magnates in 1792 in Saint Petersburg, with the backing of the Russian Empress Catherine the Great. The confederation opposed the progressive Polish Constitution of May 3rd, 1791, especially the provisions limiting the privileges of the nobility. Four days later after the proclamation of the confederation, two Russian armies invaded the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth without a formal declaration of war.

Catherine’s Foreign Policy

During her reign, Catherine extended the borders of the Russian Empire southward and westward to absorb New Russia (a region north of the Black Sea; presently part of Ukraine), Crimea, Northern Caucasus, Right-bank Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, and Courland at the expense, mainly, of two powers – the Ottoman Empire and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Under her rule, some 200,000 square miles (520,000 km2) were added to Russian territory. Catherine’s foreign minister, Nikita Panin (in office 1763–81), exercised considerable influence from the beginning of her reign but eventually Catherine had him replaced with Ivan Osterman (in office 1781–97).

Wars with the Ottoman Empire

While Peter the Great had succeeded only in gaining a toehold in the south on the edge of the Black Sea in the Azov campaigns, Catherine completed the conquest of the south. Catherine made Russia the dominant power in south-eastern Europe after her first Russo-Turkish War against the Ottoman Empire (1768–74), which saw some of the heaviest defeats in Ottoman history, including the 1770 Battles of Chesma and Kagul. The Russian victories allowed Catherine’s government to obtain access to the Black Sea and to incorporate present-day southern Ukraine, where the Russians founded several new cities. The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774) gave the Russians territories at Azov, Kerch, Yenikale, Kinburn, and the small strip of Black Sea coast between the rivers Dnieper and Bug. The treaty also removed restrictions on Russian naval or commercial traffic in the Azov Sea, granted to Russia the position of protector of Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire, and made the Crimea a protectorate of Russia.

Catherine annexed the Crimea in 1783, nine years after the Crimean Khanate had gained nominal independence—which had been guaranteed by Russia—from the Ottoman Empire as a result of her first war against the Turks. The palace of the Crimean khans passed into the hands of the Russians. In 1786, Catherine conducted a triumphal procession in the Crimea, which helped provoke the next Russo–Turkish War. The Ottomans restarted hostilities in the second Russo-Turkish War (1787–92). This war, catastrophic for the Ottomans, ended with the Treaty of Jassy (1792), which legitimized the Russian claim to the Crimea and granted the Yedisan region to Russia.

Catherine’s triumph in Crimea is linked to a concept of Potemkin villages. In politics and economics, Potemkin villages refer to any construction (literal or figurative) built solely to deceive others into thinking that a situation is better than it really is. The term comes from stories of a fake portable village, built only to impress Empress Catherine II during her journey to Crimea in 1787.

The purpose of the trip was to impress Russia’s allies. To help accomplish this in a region devastated by war, Grigory Potemkin (Catherine’s lover and trusted advisor) set up “mobile villages” on the banks of the Dnieper River. As soon as the barge carrying the Empress and ambassadors arrived, Potemkin’s men, dressed as peasants, would populate the village. Once the barge left, the village was disassembled, then rebuilt downstream overnight. Some modern historians, however, claim accounts of this portable village are exaggerated and the story is most likely a myth.

Partitions of Poland

In 1764, Catherine placed Stanisław Poniatowski, her former lover, on the Polish throne. Although the idea of partitioning Poland came from Frederick the Great of Prussia, Catherine took a leading role in carrying it out (in three separate partitions of 1772, 1793, and 1795). In 1768, she formally became protector of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which provoked an anti-Russian uprising in Poland, the Confederation of Bar (1768–72). After the uprising broke down due to internal politics in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, she established a system of government fully controlled by the Russian Empire through a Permanent Council, under the supervision of her ambassadors and envoys.

After the French Revolution of 1789, Catherine rejected many principles of the Enlightenment she had once viewed favorably. Afraid the progressive May 3rd Constitution of Poland (1791) might lead to a resurgence in the power of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the growing democratic movements inside the Commonwealth might become a threat to the European monarchies, Catherine decided to intervene in Poland. She provided support to a Polish anti-reform group known as the Targowica Confederation. After defeating Polish loyalist forces in the Polish–Russian War of 1792 and in the Kościuszko Uprising (1794), Russia completed the partitioning of Poland, dividing all of the remaining Commonwealth territory with Prussia and Austria (1795).

Partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772, 1793 and 1795

The Partitions of Poland were a series of three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place towards the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of the sovereign Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania for 123 years. The partitions were conducted by the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia and Habsburg Austria, which divided up the Commonwealth lands among themselves progressively in the process of territorial seizures.

Relations with Western Europe

Catherine agreed to a commercial treaty with Great Britain in 1766, but stopped short of a full military alliance. Although she could see the benefits of Britain’s friendship, she was wary of Britain’s increased power following its victory in the Seven Years War, which threatened the European balance of power.

Catherine longed for recognition as an enlightened sovereign. She pioneered for Russia the role that Britain later played through most of the 19th and early 20th centuries as an international mediator in disputes that could, or did, lead to war. She acted as mediator in the War of the Bavarian Succession (1778–79) between the German states of Prussia and Austria. In 1780, she established a League of Armed Neutrality, designed to defend neutral shipping from the British Royal Navy during the American Revolution. After establishing a league of neutral parties, Catherine the Great attempted to act as a mediator between the United States and Britain by submitting a ceasefire plan.

A 1791 British caricature of an attempted mediation between Catherine (on the right, supported by Austria and France) and Turkey, by James Gillray, Library of Congress.

Cartoon shows Catherine II, faint and shying away from William Pitt (British prime minister). Seated behind Pitt are the King of Prussia and a figure representing Holland as Sancho Panza. Selim III kneels to kiss the horse’s tail. a gaunt figure representing the old order in France and Leopold II (Holy Roman Emperor) render assistance to Catherine by preventing her from falling to the ground.

From 1788 to 1790, Russia fought a war against Sweden, a conflict instigated by Catherine’s cousin, King Gustav III of Sweden, who expected to simply overtake the Russian armies still engaged in war against the Ottoman Turks, and hoped to strike Saint Petersburg directly. But Russia’s Baltic Fleet checked the Royal Swedish navy in a tied battle of Hogland (1788), and the Swedish army failed to advance. Denmark declared war on Sweden in 1788 (the Theater War). After the decisive defeat of the Russian fleet at the Battle of Svensksund in 1790, the parties signed the Treaty of Värälä (1790), returning all conquered territories to their respective owners.

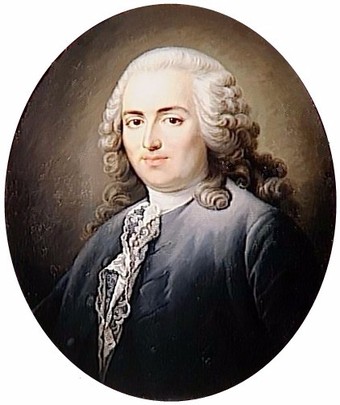

22.1.2: Louis XV

Although Louis XV’s upbringing turned him into a great patron of arts and sciences, his reign was marked by diplomatic, military, and political failures that removed France from the position of one of the most powerful and admired states in Europe.

Learning Objective

Detail Louis XV’s upbringing and his personality as king

Key Points

-

Louis XV (1710 – 1774) was a monarch of the House of Bourbon who ruled as King of France

from 1715 until his death. Until he reached maturity in 1723, his kingdom was ruled by

Philippe d’Orléans, Duke of Orléans as Regent of France, and Cardinal

Fleury was his chief minister from 1726 until

1743. - Although Louis XIV was not born as the Dauphin, the death of his great-grandfather Louis XV, his father, and his older brother made him the heir

to the throne of France at the age of five. - The young king received an excellent education that later resulted in his patronage of arts and sciences. At the age of 15, he was married to Marie Leszczyńska, daughter of Stanisław I, the

deposed king of Poland. In 1729 his wife gave

birth to a male child, an heir to the throne. The birth of a long-awaited heir, which ensured the

survival of the dynasty for the first time since 1712, was welcomed with

tremendous joy and Louis XV became extremely popular . -

In

1723, the king’s majority was declared by the Parlement of Paris, which ended

the regency. Louis XV appointed Louis Henri, Duke of Bourbon, in charge of state affairs. The Duke pursued policies

that resulted in serious economic and social problems in France, so the

king dismissed him in 1726 and selected Cardinal Fleury to

replace him. From

1726 until his death in 1743, Cardinal Fleury ruled France with the king’s

assent. It was the most peaceful and prosperous period of the reign of Louis

XV, despite some unrest. -

Historians agree that in terms of culture and art,

France reached a high point under Louis XV. However, he was blamed for the many

diplomatic, military, and economic reverses. His reign was marked by ministerial

instability and his reputation destroyed by military losses that largely

deprived France of its colonial possessions. - Louis’s XV’s reign sharply contrasts with Louis XIV’s reign. Historians emphasize Louis XIV’s military and

diplomatic successes.

Despite the fact that Louis XIV’s considerable foreign, military, and domestic expenditure

also impoverished and bankrupted France, in comparison to his great

predecessor, Louis XV is commonly seen as one of the least effective rulers of

the House of Bourbon.

Key Term

- Dauphin

-

The title given to the heir apparent to the throne of France from 1350 to 1791 and 1824 to 1830. The word is French for dolphin, as a reference to the depiction of the animal on their coat of arms.

Louis XV (1710 – 1774), known as Louis the Beloved, was a monarch of the House of Bourbon who ruled as King of France from 1715 until his death. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached maturity in 1723, his kingdom was ruled by Philippe d’Orléans, Duke of Orléans as Regent of France (his maternal great-uncle and cousin twice removed patrilineally). Cardinal Fleury was his chief minister from 1726 until the Cardinal’s death in 1743, at which time the young king took sole control of the kingdom.

Early Life

Louis XV was born during the reign of his great-grandfather Louis XIV.

His grandfather and Louis XIV’s son, Louis Le Grand Dauphin (Dauphin being

the title given to the heir apparent to the throne of France), had three sons with his wife Marie Anne Victoire of Bavaria: Louis, Duke of Burgundy; Philippe, Duke of Anjou (who became King of Spain); and Charles, Duke of Berry. Louis XV was the third son of the Duke of Burgundy and his wife Marie Adélaïde of Savoy. At birth, Louis XV received a customary title for younger sons of the French royal family: Duke of Anjou. In April 1711, Louis

Le Grand Dauphin

suddenly died, making Louis XV’s father, the Duke of Burgundy, the new Dauphin. At that time, Burgundy had two living sons, Louis, Duke of Brittany, and his youngest son, the future Louis XV.

A year later, Marie Adélaïde contracted smallpox or measles and died. Her husband, said to be heartbroken by her death, died from the disease the same week. Within a week of his death, it was clear that the couple’s two children had also been infected. Fearing that the Dauphin (the older son) would die, the Court had both the Dauphin and the Duke of Anjou baptized. The Dauphin died the same day. The Duke of Anjou, and now after his brother’s death the Dauphin, survived the smallpox.

Louis XV as a child in coronation robes, portrait by Hyacinthe Rigaud, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In September 1715, Louis XIV died of gangrene after a 72-year reign. In August 1714, he made a will stipulating that the nation was to be governed by a Regency Council made up of fourteen members until the new king reached the age of majority. Philippe, Duke of Orléans, nephew of Louis XIV, was named president of the council, but all decisions were to be made by majority vote.

By French royal tradition, princes were put in the care of men when they reached their seventh birthdays. Louis was taken from his governess, Madame de Ventadour, in 1717 and placed in the care of Francois de Villeroy, who had been designated as his governor in Louis XIV’s will. De Villeroy served under the formal authority of the Duke of Maine, who was charged with overseeing the king’s education. He was aided by André-Hercule de Fleury (later to become Cardinal Fleury), who served as the king’s tutor. Fleury gave the king an excellent education, including lessons from renowned professors (e.g., Guillaume Delisle, a cartographer known for his accurate maps of Europe and the newly explored Americas). Louis XV had an inquisitive and open-minded nature. An avid reader, he developed eclectic tastes. Later in life he advocated the creation of departments in physics (1769) and mechanics (1773) at the Collège de France.

In 1721, 11-year-old Louis XV was betrothed to his first cousin, the Infanta Maria Anna Victoria of Spain. The eleven-year-old king was not interested in the arrival of his future wife, the three-year-old Spanish Infanta.

The king was quite frail as a boy and several medical emergencies led to concern for his life. Many also assumed that the Spanish Infanta, eight years younger than the king, was too young to bear an heir in a timely way. To remedy this situation, the Duke of Bourbon set about choosing a European princess old enough to produce an heir.

Eventually, 21-year-old Marie (Maria) Leszczyńska, daughter of Stanisław I, the deposed king of Poland, was chosen to marry the king. The marriage was celebrated in 1725 when the king was 15, and the couple soon produced many children. In September 1729, in her third pregnancy, the queen finally gave birth to a male child, an heir to the throne, the Dauphin Louis (1729–1765). The birth of a long-awaited heir, which ensured the survival of the dynasty for the first time since 1712, was welcomed with tremendous joy and celebration in all spheres of French society and the young king became extremely popular.

Marie Leszczyńska in 1730, by Alexis Simon Belle.

Marie was on a list of 99 eligible European princesses to marry the young king, but she was far from the first choice on the list. She had been placed there initially because she was a Catholic princess and therefore fulfilled the minimum criteria, but was removed because she was poor when the list was reduced from 99 to 17. However, when the list of 17 was further reduced to four, the preferred choices presented numerous problems and Marie emerged as the best compromise. Queen Marie maintained the role and reputation of a simple and dignified Catholic queen. She functioned as an example of Catholic piety and was famed for her generosity to the poor and needy through her philanthropy, which made her very popular among the public her entire life as queen.

Towards the Personal Reign

In 1723, the king’s majority was declared by the Parlement of Paris, which ended the regency. Initially, Louis XV left the Duke of Orléans in charge of state affairs. The Duke of

Orléans was appointed first minister upon the death of Cardinal Dubois in August 1723, but died in December of the same year. Following the advice of Fleury, Louis XV appointed his cousin Louis Henri, Duke of Bourbon, to replace the late Duke of Orléans.

The ministry of the Duke of Bourbon pursued policies that resulted in serious economic and social problems in France. These included the persecution of Protestants; monetary manipulations; the creation of new taxes; and high grain prices. As a result of Bourbon’s rising unpopularity, the king dismissed him in 1726 and selected Cardinal Fleury, his former tutor, as a replacement.

From 1726 until his death in 1743, Cardinal Fleury ruled France with the king’s assent. It was the most peaceful and prosperous period of the reign of Louis XV, despite some unrest. After the financial and social disruptions suffered at the end of the reign of Louis XIV, the rule of Fleury is seen by historians as a period of recovery. The king’s role in the decisions of the Fleury government is unclear, but he did support Fleury against the intrigues of the court and the conspiracies of the courtiers.

Louis XV, The King

Starting in 1743 with the death of Fleury, the king ruled alone without a first minister. He had read many times the instructions of Louis XIV: “Listen to the people, seek advice from your Council, but decide alone.” His political correspondence reveals his deep knowledge of public affairs as well as the soundness of his judgement. Most government work was conducted in committees of ministers that met without the king. The king reviewed policy only in the High Council, which was composed of the king, the Dauphin, the chancellor, the finance minister, and the foreign minister. Created by Louis XIV, the council was in charge of state policy regarding religion, diplomacy, and war. There, he let various political factions oppose each other and vie for influence and power.

Historians agree that in terms of culture and art, France reached a high point under Louis XV. However, he was blamed for the many diplomatic, military, and economic reverses. His reign was marked by ministerial instability and his reputation destroyed by military losses that largely deprived France of its colonial possessions. Historians have also noted that the king left the country in the hands of his advisors while he engaged in his favorite hobbies, including hunting and womanizing. This sharply contrasts Louis XV’s reign from that of his great-grandfather and predecessor Louis XIV. Historians emphasize Louis XIV’s military and diplomatic successes, particularly placing a French prince on the Spanish throne, which ended the threat of an aggressive Spain that historically interfered in French domestic politics. They also note the effect of Louis’s wars in expanding France’s boundaries and creating more defensible frontiers that preserved France from invasion until the Revolution. Under Louis XIV, Europe came to admire France for its military and cultural successes, power, and sophistication. Europeans began to emulate French manners, values, goods, and deportment. French became the universal language of the European elite. Despite the fact that Louis XIV’s considerable foreign, military, and domestic expenditure also impoverished and bankrupted France, in comparison to his great predecessor, Louis XV is commonly seen as one of the least effective rulers of the House of Bourbon.

22.1.3: The Ancien Regime

The Ancien Régime was the social and political system fin the Kingdom of France from the 15th until the end of the 18th centuries. It was based on the rigid division of the society into three disproportionate and unequally treated classes.

Learning Objective

Describe the structure of the Ancien

Régime

and the societal rules at play

Key Points

- The Ancien Régime (Old Regime or Former Regime) was the social and political system established in the Kingdom of France from approximately the 15th century until the latter part of the 18th century under the late Valois and Bourbon dynasties.

-

The

estates of the realm were the broad orders of social hierarchy used in

Christian Europe from the medieval period to early modern Europe.

Different systems for dividing society members into estates evolved over time. The best-known system is the three-estate system of the

French Ancien Régime. -

The

First Estate comprised the entire clergy, traditionally divided into

“higher” (nobility) and “lower” (non-noble) clergy. In 1789, it numbered around 130,000

(about 0.5% of the population). -

The Second Estate was the French nobility and

(technically, although not in common use) royalty, other than the monarch

himself, who stood outside of the system of estates. It is traditionally

divided into “nobility of the sword” and “nobility of the robe,”

the magisterial class that administered royal justice and civil government. The

Second Estate constituted approximately 1.5% of France’s population -

The Third Estate comprised all of those who were

not members of the above and can be divided into two groups, urban and rural,

together making up 98% of France’s population. The urban included the

bourgeoisie and wage-laborers. The rural included peasants. - The French estates of the realm system was based on massive social injustices that were one of the key factors leading up to the French Revolution.

Key Terms

- the gabelle

-

A very unpopular tax on salt in France that was established during the mid-14th century and lasted, with brief lapses and revisions, until 1946. Because all French citizens needed salt (for use in cooking, for preserving food, for making cheese, and for raising livestock), the tax propagated extreme regional disparities in salt prices and stood as one of the most hated and grossly unequal forms of revenue generation in the country’s history.

- estates of the realm

-

The broad orders of social hierarchy used in Christendom (Christian Europe) from the medieval period to early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into estates evolved over time. The best-known system is a three-estate system of the French Ancien Régime used until the French Revolution (1789–1799). This system was made up of clergy (the First Estate), nobility (the Second Estate), and commoners (the Third Estate).

- the taille

-

A direct land tax on the French peasantry and non-nobles in Ancien Régime France. The tax was imposed on each household based on how much land it held.

- Ancien Régime

-

The social and political system established in the Kingdom of France from approximately the 15th century until the latter part of the 18th century under the late Valois and Bourbon dynasties. The term is occasionally used to refer to the similar feudal social and political order of the time elsewhere in Europe.

Ancien Régime

The Ancien Régime (Old Regime or Former Regime) was the social and political system established in the Kingdom of France from approximately the 15th century until the latter part of the 18th century under the late Valois and Bourbon dynasties. The term is occasionally used to refer to the similar feudal social and political order of the time elsewhere in Europe. The administrative and social structures of the Ancien Régime were the result of years of state-building, legislative acts, internal conflicts, and civil wars, but they remained a patchwork of local privilege and historic differences until the French Revolution ended the system. Despite the notion of absolute monarchy and the efforts by the kings to create a centralized state, Ancien Régime France remained a country of systemic irregularities. Administrative (including taxation), legal, judicial, and ecclesiastic divisions and prerogatives frequently overlapped (for example, French bishoprics and dioceses rarely coincided with administrative divisions).

Estates of the Realm

The estates of the realm were the broad orders of social hierarchy used in Christendom (Christian Europe) from the medieval period to early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into estates evolved over time. The best-known system is the three-estate system of the French Ancien Régime used until the French Revolution (1789–1799). This system was made up of clergy (the First Estate), nobility (the Second Estate), and commoners (the Third Estate).

The First Estate comprised the entire clergy, traditionally divided into “higher” and “lower” clergy. Although there was no formal demarcation between the two categories, the upper clergy were effectively clerical nobility from the families of the Second Estate. In the time of Louis XVI, every bishop in France was a nobleman, a situation that had not existed before the 18th century. At the other extreme, the “lower clergy” (about equally divided between parish priests and monks and nuns) constituted about 90 percent of the First Estate, which in 1789 numbered around 130,000 (about 0.5% of the population).

The Second Estate was the French nobility and (technically, although not in common use) royalty, other than the monarch himself, who stood outside of the system of estates. It is traditionally divided into “nobility of the sword” and “nobility of the robe,” the magisterial class that administered royal justice and civil government. The Second Estate constituted approximately 1.5% of France’s population and were exempt from the corvée royale (forced labor on the roads) and from most other forms of taxation such as the gabelle (salt tax) and most important, the taille (the oldest form of direct taxation). This exemption from paying taxes led to their reluctance to reform.

The Third Estate comprised all who were not members of the above and can be divided into two groups, urban and rural, together making up 98% of France’s population. The urban included the bourgeoisie and wage-laborers. The rural included peasants who owned their own land (and could be prosperous) and peasants who worked on nobles’ or wealthier peasants’ land. The peasants paid disproportionately high taxes compared to the other Estates and simultaneously had very limited rights. In addition, the First and Second Estates relied on the labor of the Third, which made the latter’s unequal status all the more unjust.

The Third Estate men and women shared the hard life of physical labor and food shortages. Most were born within this group and died as part of it. It was extremely rare for individuals of this status to advance to another estate. Those who crossed the class lines did so as a result of either being recognized for their extraordinary bravery in a battle or entering religious life. Some commoners were able to marry into the Second Estate, although that was very rare.

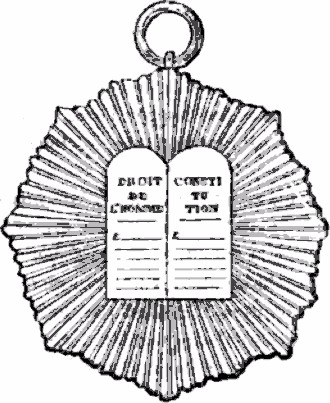

Caricature on the Third Estate carrying the First and Second Estate on its back, Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

France under the Ancien Régime (before the French Revolution) divided society into three estates: the First Estate (clergy); the Second Estate (nobility); and the Third Estate (commoners). The king was considered part of no estate.

Social Injustice

The population of France in the decade prior to the French Revolution was about 26 million, of whom 21 million lived in agriculture. Few of these owned enough land to support a family and most were forced to take on extra work as poorly paid laborers on larger farms. Despite regional differences and French peasants’ generally better economic status than that of their Eastern European counterparts, hunger was a daily problem and the condition of most French peasants was poor.

The fundamental issue of poverty was aggravated by social inequality as all peasants were liable to pay taxes from which the nobility could claim immunity, and feudal dues payable to a local lord. Similarly, the tithes (a form of obligatory tax, at the time often paid in kind), which the peasants were obliged to pay to their local churches, were a cause of grievance as the majority of parish priests were poor and the contribution was being paid to an aristocratic and usually absentee abbot. The clergy numbered about 100,000 and yet owned 10% of the land. The Catholic Church maintained a rigid hierarchy as abbots and bishops were all members of the nobility and canons were all members of wealthy bourgeois families. As an institution, it was both rich and powerful. It paid no taxes and merely contributed a grant to the state every five years, the amount of which was self-determined. The upper echelons of the clergy also had considerable influence over government policy.

Successive French kings and their ministers tried to suppress the power of the nobles but did so with very limited success.

22.1.4: The Rise of the Nobility

Despite attempts to weaken the position of the nobility, Louis XV met with avid resistance and largely failed to reform the system that privileged the aristocracy.

Learning Objective

Explain how the nobility continued to gain power throughout the reign of Louis XV.

Key Points

-

Louis

XIV believed in the divine right of kings, which assert that a monarch is

above everyone except God. He continued his predecessors’ work

of creating a centralized state governed from Paris, sought to eliminate

remnants of feudalism in France, and subjugated and weakened the aristocracy. - Louis XIV eventually failed to reform the unjust tax system that greatly favored the nobility, but instituted reforms in military administration and compelled many members of the nobility, especially the noble

elite, to inhabit Versailles. This created an effective

system of control as the king manipulated the nobility with an elaborate system

of pensions and privileges, minimizing their influence and increasing his own

power. -

Although Louis XV attempted to continue his

predecessor’s efforts to weaken the aristocracy, he failed to establish himself

as an absolute monarch of Louis XIV’s stature. He supported the policy of fiscal

justice, which created a tax on the twentieth of all revenues that

affected the privileged classes as well as commoners. This breach in the

privileged status of the aristocracy and the clergy was another attempt to impose taxes on the privileged, but the new tax

was received with violent protest from the upper classes. -

Pressed and eventually won over by his entourage

at court, the king gave in and exempted the clergy from the twentieth in 1751.

Eventually, the twentieth became a mere increase in the already existing taille,

the most important direct tax of the monarchy from which privileged classes

were exempted. -

During the reign of Louis XV, the parlements

repeatedly challenged the crown for control over policy, especially regarding

taxes and religion, which strengthened the position of the nobility and weakened the authority of the king. -

Chancellor René Nicolas de Maupeou sought to

reassert royal power by suppressing the parlements in 1770. A furious battle

resulted and after King Louis XV died, the parlements were restored.

Key Terms

- Ancien Régime

-

The social and political system established in the Kingdom of France from

approximately the 15th century until the latter part of the 18th century under

the late Valois and Bourbon dynasties. The term is occasionally used to refer

to the similar feudal social and political order of the time elsewhere in

Europe. - lit de justice

-

A particular formal session of the Parlement of Paris, under the presidency of the king, for the compulsory registration of the royal edicts.

- parlements

-

Provincial appellate courts in the France of the Ancien Régime, i.e. before the French Revolution. They were not legislative bodies but rather the court of final appeal of the judicial system. They typically wielded much power over a wide range of subject matter, particularly taxation. Laws and edicts issued by the Crown were not official in their respective jurisdictions until assent was given by publishing them. The members were aristocrats who had bought or inherited their offices and were independent of the King.

- letters patent

-

A type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president, or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, title, or status to a person or corporation.

- taille

-

A direct land tax on the

French peasantry and non-nobles in Ancien Régime France.

The tax was imposed on each household based on how much land it held.

Background: The Nobility under Louis XIV

Louis XIV believed in the divine right of kings, which assert that a monarch is above everyone except God and therefore not answerable to the will of his people, the aristocracy, or the Church. Louis continued his predecessors’ work of creating a centralized state governed from Paris, sought to eliminate remnants of feudalism in France, and subjugated and weakened the aristocracy.

The reign of Louis XIV marked the rise of France of as a military, diplomatic, and cultural power in Europe. However, the ongoing wars, the panoply of Versailles, and the growing civil administration required a great deal of money, and finance was always the weak spot in the French monarchy. Tax-collecting methods were costly and inefficient and the state always received far less than what the taxpayers paid. But the main weakness arose from an old bargain between the French crown and nobility: the king reigned with limited or no opposition from the nobles if only he refrained from taxing them. Only the commoners paid direct taxes and that meant the peasants because many bourgeois obtained exemptions. The system was outrageously unjust in throwing a heavy tax burden on the poor and helpless.

Later after 1700, the French ministers supported by Madame De Maintenon (Louis XIV’s second wife) were able to convince the King to change his fiscal policy. Louis was willing enough to tax the nobles but unwilling to fall under their control. Only towards the close of his reign under extreme stress of war was he able, for the first time in French history, to impose direct taxes on the aristocracy. This was a step toward equality before the law and toward sound public finance, but so many concessions and exemptions were won by nobles and bourgeois that the reform lost much of its value.

Louis XIV also instituted reforms in military administration through Michel le Tellier and his son François-Michel le Tellier, Marquis de Louvois. They helped to curb the independent spirit of the nobility, imposing order on them at court and in the army. Gone were the days when generals protracted war at the frontiers while bickering over precedence and ignoring orders from the capital and the larger politico-diplomatic picture. The old military aristocracy (“the nobility of the sword”) ceased to have a monopoly over senior military positions and rank.

Over time, Louis XIV also compelled many members of the nobility, especially the noble elite, to inhabit Versailles.

Provincial nobles who refused to join the Versailles system were locked out of important positions in the military or state offices. Lacking royal subsides and thus unable to keep up a noble lifestyle, these rural nobles often went into debt.

This created an effective system of control as the king manipulated the nobility with an elaborate system of pensions and privileges, minimizing their influence and increasing his own power.

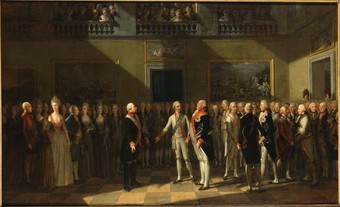

French aristocrats, c. 1774, by Antoine-Jean Duclos.

In the political system of pre-Revolutionary France, the nobility made up the Second Estate (with the Catholic clergy comprising the First Estate and the bourgeoisie and peasants in the Third Estate). Although membership in the noble class was mainly inherited, it was not a closed order. New individuals were appointed to the nobility by the monarchy, or could purchase rights and titles or join by marriage. Sources differ about the actual number of nobles in France, but proportionally it was among the smallest noble classes in Europe.

Louis XV: Attempts to Reform

Although Louis XV attempted to continue his predecessor’s efforts to weaken the aristocracy, he failed to establish himself as an absolute monarch of Louis XIV’s stature. Following the advice of his mistress, Marquise de Pompadour, Louis XV supported the policy of fiscal justice designed by Machault d’Arnouville. In order to finance the budget deficit, which amounted to 100 million livres in 1745, Machault d’Arnouville created a tax on the twentieth of all revenues that affected the privileged classes as well as commoners. This breach in the privileged status of the aristocracy and the clergy, normally exempt from taxes, was another attempt to impose taxes on the privileged. However, the new tax was received with violent protest from the privileged classes in the estates of the few provinces that retained the right to decide taxation (most provinces had long lost their provincial estates and the right to decide taxation). The new tax was also opposed by the clergy and by the parlements (provincial appellate court staffed by aristocrats). Members of these courts bought their positions from the king, together with the right to transfer their positions hereditarily through payment of an annual fee. Membership in such courts and appointment to other public positions often led to elevation to nobility (the so-called nobles of the robe, as distinguished from the nobility of ancestral military origin, the nobles of the sword.) While these two categories of nobles were often at odds, both sought to retain their privileges.

The Role of Parlements

Pressed and eventually won over by his entourage at court, the king gave in and exempted the clergy from the twentieth in 1751. Eventually, the twentieth became a mere increase in the already existing taille, the most important direct tax of the monarchy from which privileged classes were exempted. It was another defeat in the taxation war waged against the privileged classes. As a result of these attempts at reform, the Parlement of Paris, using the quarrel between the clergy and the Jansenists as a pretext, addressed remonstrances to the king in April 1753. In these remonstrances, the Parlement, made up of privileged aristocrats and ennobled commoners, proclaimed itself the “natural defender of the fundamental laws of the kingdom” against the arbitrariness of the monarchy.

During the reign of Louis XV, the parlements repeatedly challenged the crown for control over policy, especially regarding taxes and religion. The parlements had the duty to record all royal edicts and laws. Some, especially the Parlement of Paris, gradually acquired the habit of refusing to register legislation with which they disagreed until the king held a lit de justice or sent letters patent to force them to act. Furthermore, the parlements could pass certain regulations, which were laws that applied within their jurisdiction. In the years immediately before the start of the French Revolution in 1789, their extreme concern to preserve Ancien Régime institutions of noble privilege prevented France from carrying out many simple reforms, especially in the area of taxation, even when those reforms had the support of the king. Chancellor René Nicolas de Maupeou sought to reassert royal power by suppressing the parlements in 1770. A furious battle resulted and after King Louis XV died, the parlements were restored.

22.1.5: France’s Fiscal Woes

Under Louis XIV, France witnessed successful reforms and growth as a global power, but financial strain imposed by multiple wars left the state bankrupt. Under Louis XV, lost wars and limited reforms reversed the gains of the initial years of economic recovery.

Learning Objective

Examine the excessive spending of Louis XIV and Louis XV and the consequences of their actions for the French government.

Key Points

-

Louis

XIV began his personal reign with effective fiscal reforms. He chose

Jean-Baptiste Colbert as Controller-General of Finances in 1665, and Colbert

reduced the national debt through more efficient taxation. However,

the gains were insufficient to support Louis’s policies. During his

reign, France fought three major wars and two

lesser conflicts. In

order to weaken the power of the nobility, Louis attached nobles to his court at

Versailles. These strategies to hold centralized power, although effective,

were very costly. - To

support the reorganized and enlarged army, the panoply of Versailles, and the

growing civil administration, the king needed more money.

Only towards the close of his reign under extreme stress of war was he

able to impose direct taxes on the

aristocratic population. However, so many concessions and exemptions

were won by nobles and bourgeois that the reform lost much of its value. -

Louis encouraged industry, fostered

trade and commerce, and sponsored the founding of an overseas empire, but the powerful position of Louis XIV’s France came at a financial cost that could not be balanced by his reforms. The considerable

foreign, military, and domestic expenditure impoverished and bankrupted France. -

Cardinal

Fleury was Louis XV’s chief minister and his rule was the most peaceful and prosperous period of the reign of Louis XV. After

the financial and social disruptions suffered at the end of the reign of Louis

XIV, the rule of Fleury is seen by historians as a period of

“recovery.” Following Fleury’s death, Louis failed to continue his policies. - Louis XV attempted fiscal reforms that included the taxation of the nobility but his foreign policy failures weakened France and further strained its finances. As a result of lost wars,

Louis was forced to cede many territories, including lucrative overseas colonies. -

Lost

wars and subsequent financial strains, ineffective reforms, and

religious feuds, combined with XV’s reputation as a man interested more

in women and hunting than in ruling France, weakened the monarchy that was left

in a state of economic crisis.

Key Terms

- parlements

-

Provincial appellate courts

in the France of the Ancien Régime, i.e. before the French

Revolution. They were not legislative bodies but rather the court of final

appeal of the judicial system. They typically wielded much power over a wide

range of subject matter, particularly taxation. Laws and edicts issued by the Crown

were not official in their respective jurisdictions until assent was given by publishing them. The members were aristocrats who had bought or

inherited their offices and were independent of the King. - Seven Years’ War

-

A world war fought between 1754 and 1763, the main conflict occurring in the seven-year period from 1756 to 1763. It involved every European great power of the time except the Ottoman Empire, spanning five continents and affecting Europe, the Americas, West Africa, India, and the Philippines. The conflict split Europe into two coalitions, led by Great Britain on one side and France on the other. For the first time, aiming to curtail Britain and Prussia’s ever-growing might, France formed a grand coalition of its own, which ended with failure as Britain rose as the world’s predominant force, altering the European balance of power.

- Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle of 1748

-

A treaty, sometimes called the Treaty of Aachen, that ended the War of the Austrian Succession following a congress assembled in 1748 at the Free Imperial City of Aachen and signed by Great Britain, France, and the Dutch Republic.

- taille

-

A direct land tax on the

French peasantry and non-nobles in Ancien Régime France. The tax

was imposed on each household based on how much land it held.

Louis XIV: Finance Reform vs. High Spending

Louis XIV, known as the “Sun King,” reigned over France from 1643 until 1715. He began his personal reign with effective fiscal reforms. In 1661, the treasury verged on bankruptcy. To rectify the situation, Louis chose Jean-Baptiste Colbert as Controller-General of Finances in 1665. Colbert reduced the national debt through more efficient taxation. Although his tax reform proved difficult, excellent results were achieved and the deficit of 1661 turned into a surplus in 1666. In 1667, the net receipts had risen to 20 million pounds sterling while expenditure had fallen to 11 million, leaving a surplus of 9 million pounds.

However, the gains were insufficient to support Louis’s policies. During his reign, France fought three major wars: the Franco-Dutch War, the War of the League of Augsburg, and the War of the Spanish Succession. There were also two lesser conflicts: the War of Devolution and the War of the Reunions. Warfare defined the foreign policies of Louis XIV, seen by the king as the ideal way to enhance his glory. Even in peacetime, he concentrated on preparing for the next war, including reforms that enlarged and modernized the French military.

Furthermore, in order to centralize his power, Louis recognized that he had to weaken the power of the nobility, which he achieved partly by attaching nobles to his court at Versailles and thus virtually controlling their daily lives. Apartments were built to house those willing to pay court to the king, but the pensions and privileges necessary to live in a style appropriate to their rank were only possible by waiting constantly on Louis. This strategy, although effective, turned out to be very costly, particularly given the king’s extravagant choices and lavish lifestyle.

To support the reorganized and enlarged army, the panoply of Versailles, and the growing civil administration, the king needed more money. Methods of collecting taxes were costly and inefficient. Direct taxes passed through the hands of many intermediate officials; indirect taxes were collected by private individuals called tax farmers who made a substantial profit. The state always received far less than what the taxpayers actually paid. Yet the main weakness arose from an old bargain between the French crown and nobility: the king could rule without much opposition from the nobility if only he refrained from taxing them. Only the lowest classes paid direct taxes and that meant mostly peasants since many bourgeois obtained exemptions. Later after 1700, the French ministers who were supported by Madame De Maintenon (the king’s second wife) were able to convince the King to change his fiscal policy. Louis was willing to tax the nobles but unwilling to fall under their control, and only towards the close of his reign under extreme stress of war was he able, for the first time in French history, to impose direct taxes on the aristocratic elements of the population. This was a step toward equality before the law and sound public finance, but so many concessions and exemptions were won by nobles and bourgeois that the reform lost much of its value.

In addition to successful finance reforms, Louis encouraged industry, fostered trade and commerce, and sponsored the founding of an overseas empire. His political and military victories as well as numerous cultural achievements helped raise France to a preeminent position in Europe. Historians note, however, that the powerful position of Louis XIV’s France came at a financial cost that could not be balanced by his reforms. The considerable foreign, military, and domestic expenditure impoverished and bankrupted France.

Louis XIV in 1690, by Jean Nocret.

Voltaire’s history, The Age of Louis XIV, named Louis’s reign as not only one of the four great ages in which reason and culture flourished, but the greatest ever. The success, however, came at the financial cost that bankrupted France.

Louis XV: The Disintegration of the Empire

Louis XV succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached maturity in 1723, his kingdom was ruled by Philippe d’Orléans, Duke of Orléans as Regent of France. Cardinal Fleury was his chief minister from 1726 until the Cardinal’s death in 1743, at which time the young king took sole control of the kingdom. Fleury’s rule was he most peaceful and prosperous period of the reign of Louis XV. After the financial and social disruptions suffered at the end of the reign of Louis XIV, the rule of Fleury is seen by historians as a period of “recovery.” Fleury stabilized the French currency and balanced the budget in 1738. Economic expansion was a major goal of the government. Communications were improved with the completion of the Saint-Quentin canal in 1738 and the systematic building of a national road network. By the middle of the 18th century, France had the most modern and extensive road network in the world. Modern highways, which stretched from Paris to the most distant borders of France, helped to advance trade. In foreign relations, Fleury sought peace by trying to maintain alliance with England and pursuing reconciliation with Spain.

After Fleury’s death, Louis failed to continue his policies. Following the advice of his mistress, Marquise

de Pompadour, he supported the policy of fiscal justice designed by

Machault d’Arnouville. In order to finance the budget deficit, Machault d’Arnouville

created a tax on the twentieth of all revenues that affected the privileged

classes as well as commoners. This breach in the privileged status of the

aristocracy and the clergy, normally exempt from taxes, was another attempt to

impose taxes on the privileged, but the new tax was received with violent

protest from the privileged classes. It was opposed by the clergy and by the parlements (provincial

appellate court staffed by aristocrats).

Pressed and eventually won over by his entourage

at court, the king gave in and exempted the clergy from the twentieth in 1751.

Eventually, the twentieth became a mere increase in the already existing taille,

the most important direct tax of the monarchy from which privileged classes

were exempted. It was another defeat in the taxation war waged against the

privileged classes.

Louis’s greatest failure was perhaps his foreign policy.

As a result of lost wars, Louis was forced to return the Austrian Netherlands (modern-day Belgium) territory won at the Battle of Fontenoy of 1745 but returned to Austria by the terms of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle of 1748. He also ceded New France in North America to Spain and Great Britain at the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War in 1763. Although he incorporated the territories of Lorraine and Corsica into the kingdom of France, the loss of colonies in North America, the Caribbean, and West Africa as well as the weakening of influence in India demonstrated that France was no longer a colonial European power with access to lucrative overseas opportunities (although France did maintain control over Guadeloupe and Martinique, sources of profitable sugar).

Most historians argue that Louis XV’s decisions damaged the power of France, weakened the treasury, discredited the absolute monarchy, and made it more vulnerable to distrust and destruction. Lost wars and financial strains that they imposed, ineffective reforms, and religious feuds, combined with the king’s reputation as a man interested more in women and hunting than in ruling France, weakened the monarchy that was left in a state of economic crisis.

Louis XV, by Louis Michel van Loo, (Château de Versailles), Library and Archives Canada.

Under Louis XV, financial strain imposed by wars, particularly by the disastrous for France Seven Years’ War and by the excesses of the royal court, contributed to fiscal problems and the national unrest that in the end culminated in the French Revolution of 1789.

22.1.6: Taxes and the Three Estates

The taxation system under the Ancien Régime largely excluded the nobles and the clergy from taxation while the commoners, particularly the peasantry, paid disproportionately high direct taxes.

Learning Objective

Distinguish between the three Estates and their burdens of taxation.

Key Points

-

France under the Ancien Régime was divided society into three estates: the First Estate

(clergy); the Second Estate (nobility); and the Third Estate (commoners). One critical difference between the

estates of the realm was the burden of taxation. The nobles and the clergy were

largely excluded from taxation while the commoners paid disproportionately

high direct taxes. -

The desire for more efficient tax collection was

one of the major causes for French administrative and royal centralization. The

taille became a

major source of royal income. Exempted from the taille were clergy and nobles (with few exceptions). Different kinds of provinces had different taxation obligations and some among the nobility and the clergy paid modest taxes, but the majority of taxes was always paid by the poorest. Moreover, the church separately taxed the commoners and the nobles. -

As the French state continuously struggled with

the budget deficit, some attempts to reform the skewed system took place under

both Louis XIV and Louis XV. The greatest challenge to introduce any

changes was an old bargain between the French crown and the nobility: the king

could rule without much opposition from the nobility if only he refrained from

taxing them. - New taxes introduced under Louis XIV

were a step toward equality before the law and

sound public finance, but so many concessions and exemptions were won by

nobles and bourgeois that the reform lost much of its value. - Although Louis XV also attempted to impose new taxes on the First and Second Estates, with

all the exemptions and reductions won by the privileged classes the

burden of the new tax once again fell on the poorest citizens. -

Historians

consider the unjust taxation system, continued under Louis XVI, to be one of

the causes of the French Revolution.

Key Terms

- the estates of the realm

-

The broad orders of social

hierarchy used in Christendom (Christian Europe) from the medieval period to

early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into

estates evolved over time. The best known system is a

three-estate system of the French Ancien Régime used until the French

Revolution (1789–1799). This system was made up of clergy (the First Estate),

nobility (the Second Estate), and commoners (the Third Estate). - parlements

-

Provincial appellate courts in

the France of the Ancien Régime, i.e. before the French Revolution.

They were not legislative bodies but rather the court of final appeal of the

judicial system. They typically wielded much power over a wide range of subject

matter, particularly taxation. Laws and edicts issued by the Crown were not

official in their respective jurisdictions until assent was given by

publishing them. The members were aristocrats who had bought or inherited their

offices and were independent of the King. - Ancien Régime

-

The

social and political system established in the Kingdom of France from

approximately the 15th century until the latter part of the 18th century under

the late Valois and Bourbon dynasties. The term is occasionally used to refer

to the similar feudal social and political order of the time elsewhere in

Europe. - taille

-

A direct land tax on the

French peasantry and non-nobles in Ancien Régime France.

The tax was imposed on each household and was based on how much land it held. - tithe

-

A one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, the fee is voluntary and paid in cash, checks, or stocks, whereas historically it was required and paid in kind, such as with agricultural products.

Estates of the Realm and Taxation

France under the Ancien Régime (before the French Revolution) divided society into three estates: the First Estate (clergy); the Second Estate (nobility); and the Third Estate (commoners). The king was not considered part of any estate. One critical difference between the estates of the realm was the burden of taxation. The nobles and the clergy were largely excluded from taxation

(with the exception of a modest quit-rent, an ad valorem tax on land) while the commoners paid disproportionately high direct taxes. In practice, this meant mostly the peasants because many bourgeois obtained exemptions. The system was outrageously unjust in throwing a heavy tax burden on the poor and powerless.

Taxation Structure

The desire for more efficient tax collection was one of the major causes for French administrative and royal centralization. The taille, a direct land tax on the peasantry and non-nobles, became a major source of royal income. Exempted from the taille were clergy and nobles (except for non-noble lands they held in “pays d’état;” see below), officers of the crown, military personnel, magistrates, university professors and students, and certain cities (“villes franches”) such as Paris. Peasants and nobles alike were required to pay one-tenth of their income or produce to the church (the tithe).

Although exempted from the taille, the church was required to pay the crown a tax called the “free gift,” which it collected from its office holders at roughly 1/20 the price of the office.

There were three kinds of provinces: the “pays d’élection,” the “pays d’état,” and the “pays d’imposition.” In the “pays d’élection” (the longest held possessions of the French crown) the assessment and collection of taxes were originally trusted to elected officials, but later these positions were bought. The tax was generally “personal,” which meant it was attached to non-noble individuals. In the “pays d’état” (provinces with provincial estates), tax assessment was established by local councils and the tax was generally “real,” which meant that it was attached to non-noble lands (nobles possessing such lands were required to pay taxes on them). “Pays d’imposition” were recently conquered lands that had their own local historical institutions, although taxation was overseen by the royal administrator.

In the decades leading to the French Revolution, peasants paid a land tax to the state (the taille) and a 5% property tax (the vingtième; see below). All paid a tax on the number of people in the family (capitation), depending on the status of the taxpayer (from poor to prince). Further royal and seigneurial obligations might be paid in several ways: in labor, in kind, or rarely, in coin. Peasants were also obligated to their landlords for rent in cash, a payment related to their amount of annual production, and taxes on the use of the nobles’ mills, wine-presses, and bakeries.

Caricature showing the Third Estate carrying the First and Second Estates on its back, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, c. 1788.

The tax system in pre-revolutionary France largely exempted the nobles and the clergy from taxes. The tax burden therefore devolved to the peasants, wage-earners, and the professional and business classes, also known as the Third Estate. Further, people from less-privileged walks of life were blocked from acquiring even petty positions of power in the regime, which caused further resentment.

Attempts at Reform

As the French state continuously struggled with the budget deficit, attempts to reform the skewed system took place under both Louis XIV and Louis XV. The greatest challenge to systemic change was an old bargain between the French crown and the nobility: the king could rule without much opposition from the nobility if only

he refrained from taxing them. Consequently, attempts to impose taxes on the privileged — both the nobility and the clergy —

were a great source of tension between the monarchy and the First and the Second Estates.

Already in

1648, when Louis XIV was still a minor and his mother Queen Anne acted as a regent and Cardinal Mazarin as her chief minister, the two attempted to tax members of the Parlement de Paris. The members not only refused to comply, but also ordered all of Mazarin’s earlier financial edicts burned. The later wars of Louis XIV, although successful politically and militarily, exhausted the state’s budget, which eventually led the King to accept reform proposals. Only towards the end of Louis’s reign did the French ministers supported by Madame De Maintenon (the King’s second wife) convince the King to change his fiscal policy.

Louis was willing to tax the nobles but unwilling to fall under their control, and only under extreme stress of war was he

able, for the first time in French history, to impose direct taxes on the

aristocracy. Several additional tax systems were created, including the “capitation” (begun in 1695), which touched every person including nobles and the clergy (although exemption could be bought for a large one-time sum) and the “dixième” (1710–17, restarted in 1733), enacted to support the military, which was a true tax on income and property value. This was a step toward equality before

the law and sound public finance, but so many concessions and exemptions

were won by nobles and bourgeois that the reform lost much of its value.

Louis XV continued the tax reform initiated by his predecessor.

Following

the advice of his mistress, Marquise de Pompadour, he supported the policy of

fiscal justice designed by Machault d’Arnouville. In order to finance the

budget deficit, in 1749 Machault d’Arnouville created a tax on the twentieth of all

revenues that affected the privileged classes as well as commoners.

Known as the “vingtième” (or “one-twentieth”), it was enacted to reduce the royal deficit. This tax continued throughout the Ancien Régime. It was based solely on revenues, requiring 5% of net earnings from land, property, commerce, industry, and official offices. It was meant to touch all citizens regardless of status. However, the clergy, the regions with “pays d’état,” and the parlements protested. Consequently, the clergy won exemption, the “pays d’état” won reduced rates, and the parlements halted new income statements, effectively making the “vingtième” a far less efficient tax than it was designed to be. The financial needs of the Seven Years’ War led to a second (1756–1780) and then a third (1760–1763) “vingtième” being created. With all the exemptions and reductions won by the privileged classes, however, the burden of the new tax once again fell on the poorest.

Historians consider the unjust taxation system continued under Louis XVI to be one of the causes of the French Revolution.

22.1.7: Territorial Losses

Louis XV’s controversial decision following the War of the Austrian Succession and his loss in the Seven Years’ War weakened the international position of France and lost most of its colonial holdings.

Learning Objective

Describe the land lost under Louis XV

Key Points

-

Louis XV inherited a country with a

reputation of a military, political, colonial, and cultural power. By the end

of his reign, however, the international opinion of France changed

dramatically, largely because of Louis’s controversial foreign policy. -

Louis XV entered the War of the Austrian Succession in 1741 on the side of Prussia in hopes of pursuing its own anti-Austrian

foreign policy goals. In Germany, the French

were forced back to the Rhine and their Bavarian allies were decisively

defeated. In the Netherlands,

France experienced much military success. By 1748, France

occupied the entire Austrian Netherlands (modern-day Belgium) as well as some

parts of the northern Netherlands, then the wealthiest area of Europe. -

Despite his victory, Louis XV, who wanted to

appear as an arbiter and not as a conqueror, agreed to restore all his

conquests back to the defeated enemies with chivalry at the Treaty of

Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748.

The attitude was internationally hailed, but at home the king became unpopular. -

In what is known as diplomatic revolution, the king overruled his ministers and

signed the Treaty of Versailles with Austria in 1756. The new Franco-Austrian alliance

would last intermittently for the next thirty-five years. In 1756, Frederick

the Great invaded Saxony without a declaration of war, initiating the Seven

Years’ War, and Britain declared war on France. -

The French military successes of the War of the

Austrian Succession were not repeated in the Seven Years’ War, except for a few

temporary victories. - The Treaty of Paris forced France to cede Canada, Dominica,

Grenada, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Tobago to Britain. France also

ceded the eastern half of French Louisiana to Britain. In addition, while

France regained its trading posts in India, it recognized British clients as

the rulers of key Indian native states and pledged not to send troops to

Bengal.

Key Terms

- French and Indian War

-

A 1754–1763 conflict that comprised the North American theater of the worldwide Seven Years’ War of 1756-1763. The war pitted the colonies of British America against those of New France, with both sides supported by military units from their parent countries of Great Britain and France as well as by American Indian allies.

- Treaty of Paris of 1763

-

A 1763 treaty signed by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France, and Spain with Portugal in agreement, after Great Britain’s victory over France and Spain during the Seven Years’ War. The signing of the treaty formally ended the Seven Years’ War and marked the beginning of an era of British dominance outside Europe. Great Britain and France each returned much of the territory they had captured during the war, but Great Britain gained much of France’s possession in North America. Additionally, Great Britain agreed to protect Roman Catholicism in the New World. The treaty did not involve Prussia and Austria as they signed a separate agreement, the Treaty of Hubertusburg.

- War of the Austrian Succession

-

A war (1740–1748) that involved most of the powers of Europe over the question of Maria Theresa’s succession to the realms of the House of Habsburg. The war included King George’s War in North America, the War of Jenkins’ Ear, the First Carnatic War in India, the Jacobite rising of 1745 in Scotland, and the First and Second Silesian Wars. It began under the pretext that Maria Theresa was ineligible to succeed to the Habsburg thrones of her father, Charles VI.

- Seven Years’ War

-

A world war fought between 1754 and 1763, the main conflict occurring in the seven-year period from 1756 to 1763. It involved every European great power of the time except the Ottoman Empire, spanning five continents and affecting Europe, the Americas, West Africa, India, and the Philippines. The conflict split Europe into two coalitions, led by Great Britain on one side and France on the other.

- Treaty of Aix-la-Chape

-

A 1748 treaty, sometimes called the Treaty of Aachen, that ended the War of the Austrian Succession following a congress assembled at the Free Imperial City of Aachen. The treaty was signed by Great Britain, France, and the Dutch Republic. Two implementation treaties were signed at Nice in 1748 and 1749 by Austria, Spain, Sardinia, Modena, and Genoa.

- diplomatic revolution

-

The reversal of longstanding alliances in Europe between the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years’ War. Austria went from an ally of Britain to an ally of France. Prussia became an ally of Britain. It was part of efforts to preserve or upset the European balance of power.

Background

The reign of Louis XIV left the French state financially troubled but politically triumphant. Louis’s political and military victories as well as numerous cultural achievements helped raise France to a preeminent position in Europe. Europe came to admire France for its military and cultural successes, power, and sophistication. Europeans generally began to emulate French manners, values, and goods, and French became the universal language of the European elite. Louis XIV’s successor and great-grandson, Louis XV, inherited a country with a reputation of a military, political, colonial, and cultural power. By the end of his reign, however, the international opinion of France changed dramatically, largely because of Louis’s controversial foreign policy.

The War of the Austrian Succession

In 1740, the death of Emperor Charles VI and his succession by his daughter Maria Theresa started the War of the Austrian Succession. Sensing the vulnerability of Maria Theresa’s position, King Frederick the Great of Prussia invaded the Austrian province of Silesia in hopes of annexing it permanently. The elderly Cardinal Fleury had little energy left to oppose the war, which was strongly supported by the anti-Austrian party at court. Renewing the cycle of conflicts typical of Louis XIV’s reign, the king entered the war in 1741 on the side of Prussia in hopes of pursuing its own anti-Austrian foreign policy goals. The war would last seven years and Fleury did not live to see its end. After Fleury’s death in 1743, the king followed his predecessor’s example of ruling without a first minister. In Germany, the French were forced back to the Rhine and their Bavarian allies were decisively defeated. At one point Austria even considered launching an offensive against Alsace, before being compelled to retreat due to a Prussian offensive. In north Italy, the war stalled and did not produce significant results.

These fronts were of lesser importance than the front in the Netherlands. Here, France experienced much military success despite the king’s loss of his trusted advisor. Against an army composed of British, Dutch, and Austrian forces, the French were able to savor a series of major victories at the Battles of Fontenoy (1745), Rocoux (1746), and Lauffeld (1747). In 1746, French forces besieged and occupied Brussels, which Louis entered in triumph. By 1748, France occupied the entire Austrian Netherlands (modern-day Belgium) as well as some parts of the northern Netherlands, then the wealthiest area of Europe.

Despite his victories, Louis XV, who wanted to appear as an arbiter and not as a conqueror, agreed to restore all his conquests back to the defeated enemies with chivalry at the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, arguing that he was “king of France, not a shopkeeper.” He thought it better to cultivate the existing borders of France rather than trying to expand them. The attitude was internationally hailed and he became known as the “arbiter of Europe.” At home, however, this decision, largely misunderstood by his generals and by the French people, made the king unpopular. The news that the king had restored the Southern Netherlands to Austria was met with disbelief and bitterness. Louis’s popularity was also threatened by public exposure of his marital infidelities, which likely could have been kept concealed had France not entered the War of the Austrian Succession (when taking personal command of his armies, the king brought along one of his mistresses). The military successes of the War of the Austrian Succession inclined the French public to overlook Louis’s adulteries, but after 1748, in the wake of the anger over the terms of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, pamphlets against the king’s mistresses became increasingly widely published and read.

Europe in the years after the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748

In the aftermath of the War of Austrian Succession in France, there was a general resentment at what was seen as a foolish throwing away of advantages (particularly in the Austrian Netherlands, which had largely been conquered by the brilliant strategy of Marshal Saxe), and the phrases Bête comme la paix (“Stupid as the peace”) and La guerre pour le roi de Prusse (“The war for the king of Prussia”) became popular in Paris.

Seven Years’ War