13.1: The Mongol Empire

13.1.1: Overview of the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire expanded through brutal raids and invasions, but also established routes of trade and technology between East and West.

Learning Objective

Define the significance of the Pax Mongolica

Key Points

- The Mongol Empire existed during the 13th and 14th centuries and was the largest land empire in history.

- The empire unified the nomadic Mongol and Turkic tribes of historical Mongolia.

- The empire sent invasions in every direction, ultimately connecting the East with the West with the Pax Mongolica, or Mongol Peace, which allowed trade, technologies, commodities, and ideologies to be disseminated and exchanged across Eurasia.

- The Mongol raids and invasions were some of the deadliest and most terrifying conflicts in human history.

- Ultimately, the empire started to fragment; it dissolved in 1368, at which point the Han Chinese Ming Dynasty took control.

Key Terms

- tributary states

-

Pre-modern states subordinate to a more powerful state.

- Pax Mongolica

-

Also known as the Mongol Peace, this agreement allowed trade, technologies, commodities, and ideologies to be disseminated and exchanged across Eurasia.

- High Middle Ages

-

A time between the 10th and 12th centuries when the core cultural and social characteristics of the Middle Ages were firmly set.

Rise of the Mongol Empire

During Europe’s High Middle Ages the Mongol Empire, the largest contiguous land empire in history, began to emerge. The Mongol Empire began in the Central Asian steppes and lasted throughout the 13th and 14th centuries. At its greatest extent it included all of modern-day Mongolia, China, parts of Burma, Romania, Pakistan, Siberia, Ukraine, Belarus, Cilicia, Anatolia, Georgia, Armenia, Persia, Iraq, Central Asia, and much or all of Russia. Many additional countries became tributary states of the Mongol Empire.

The empire unified the nomadic Mongol and Turkic tribes of historical Mongolia under the leadership of Genghis Khan, who was proclaimed ruler of all Mongols in 1206. The empire grew rapidly under his rule and then under his descendants, who sent invasions in every direction. The vast transcontinental empire connected the east with the west with an enforced Pax Mongolica, or Mongol Peace, allowing trade, technologies, commodities, and ideologies to be disseminated and exchanged across Eurasia.

Mongol invasions and conquests progressed over the next century, until 1300, by which time the vast empire covered much of Asia and Eastern Europe. Historians regard the Mongol raids and invasions as some of the deadliest and most terrifying conflicts in human history. The Mongols spread panic ahead of them and induced population displacement on an unprecedented scale.

The Mongol Empire

Expansion of the Mongol empire from 1206 CE-1294 CE.

Impact

of the Pax Mongolica

The Pax Mongolica refers to the relative stabilization of the regions under Mongol control during the height of the empire in the 13th and 14th centuries. The Mongol rulers maintained peace and relative stability in such varied regions because they did not force subjects to adopt religious or cultural traditions. However, they still enforced a legal code known as the Yassa (Great Law), which stopped feudal disagreements at local levels and made outright disobedience a dubious prospect. It also ensured that it was easy to create an army in short time and gave the khans access to the daughters of local leaders.

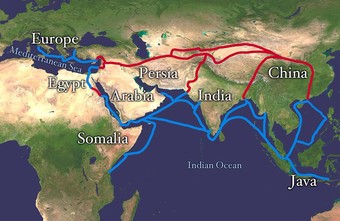

The Silk Road

At its height these trade routes stretched between Europe, Persia, and China. They connected ideas, materials, and people in new and exciting ways that allowed for innovations.

The constant presence of troops across the empire also ensured that people followed Yassa edicts and maintained enough stability for goods and for people to travel long distances along these routes. In this environment the largest empire to ever exist helped one of the most influential trade routes in the world, known as the Silk Road, to flourish. This route allowed commodities such as silk, pepper, cinnamon, precious stones, linen, and leather goods to travel between Europe, the Steppe, India, and China.

Marco Polo in a Tatar costume

This style of dress, with the fur hat, long coat, and saber, would have been popular in regions in and around Russian, Eurasia, and Turkey.

Ideas

also traveled along the trade route, including major discoveries and

innovations in mathematics,

astronomy, paper-making, and banking systems from various parts of the world. Famous explorers, such

as Marco Polo, also enjoyed the freedom and stability the Pax Mongolica provided, and were able to bring

back valuable information about the East and the Mongol Empire to Europe.

The Empire Starts to Fragment

Tatar and Mongol raids against Russian states continued well into the later 1200’s. Elsewhere, the Mongols’ territorial gains in China persisted into the 14th century under the Yuan Dynasty, while those in Persia persisted into the 15th century under the Timurid Dynasty. In India, the Mongols’ gains survived into the 19th century as the Mughal Empire.

However, the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260 was a turning point. It was the first time a Mongol advance had ever been beaten back in direct combat on the battlefield, and it marked the beginning of the fragmentation of the empire due to wars over succession. The grandchildren of Genghis Khan disputed whether the royal line should follow from his son and initial heir Ögedei or one of his other sons. After long rivalries and civil war, Kublai Khan took power in 1271 when he established the Yuan Dynasty, but civil war ensued again as he sought unsuccessfully to regain control of the followers of Genghis Khan’s other descendants.

By the time of Kublai’s death in 1294, the Mongol Empire had fractured into four separate empires, or khanates. This weakness allowed the Han Chinese Ming Dynasty to take control in 1368, while Russian princes also slowly developed independence over the 14th and 15th centuries, and the Mongol Empire finally dissolved.

13.2: Genghis Khan

13.2.1: Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan ruled between 1206 and 1227, expanding trade across Asia and into eastern Europe, enacting relatively tolerant social and religious laws, and leading devastating military campaigns that

left local populations depleted and fearful of the brutal Mongol forces.

Learning Objective

Outline the major

cultural contributions and complex role played by Genghis Khan in

the development of the Mongol Empire

Key Points

- Genghis Khan was the first leader, or Khan, of the Mongol Empire, from 1206 CE–1227 CE.

- Genghis Khan generally advocated literacy, religious freedom, and trade, although many local customs were frowned upon or discarded once Mongol rule was implemented.

- In terms of social policy, he forbade selling of women, theft of property, and fighting.

-

This ruler used groundbreaking siege warfare and spy techniques to understand his enemies and more

successfully conquer and subsume them under his rule. -

Genghis Khan led

merciless conquests of the Western Xia Dynasty, the Jin Dynasty in

1234, the Kara-Khitan Khanate, and the Khwarazmian Empire. Many

local people across Asia considered Genghis Khan a dark historical

figure.

Key Terms

- Khan

-

The universal leader of the Mongol tribes.

- Temujin

-

Ghengis Khan’s birth name.

- Uyghur-Mongolian script

-

The first writing system created specifically for the Mongolian language and the most successful until the introduction of Cyrillic in 1946. This is a true alphabet with separate letters for consonants and vowels, alphabets based on this script are used in Inner Mongolia and other parts of China to this day.

The First Khan and the Mongol Empire

Before Genghis Khan

became the leader of Mongolia, he was known as Temujin.

He was born around 1162 in modern-day northern Mongolia into a nomadic tribe

with noble ties and powerful alliances. These fortunate circumstances

helped him unite dozens of tribes in his adulthood via alliances. In

his early 20s he married his young wife Börte, a bride from another

powerful tribe. Soon, bubbling tensions erupted and she was kidnapped

by a rival tribe. During this era, and possibly spurred by the

capture of his wife, Temujin united the nomadic,

previously ever-rivaling Mongol tribes under his rule through

political manipulation and military might, and also reclaimed his bride from the rebellious tribe.

As Temujin gained

power, he forbade looting of his enemies without permission, and he

implemented a policy of sharing spoils with his warriors and their

families instead of giving it all to the aristocrats. His

meritocratic policies tended to gain a broader range of followers,

compared to his rival brother, Jamukha, who also hoped to rule over greater swaths of Mongolian territory. This split in policies created conflict with his uncles and brothers, who were

also legitimate heirs to Mongol succession, as well as his generals.

War ensued, and

Temujin prevailed, destroying all the remaining rival tribes from

1203–1205 and bringing them under his sway. In 1206, Temujin was

crowned as the leader of the Great Mongol Nation. It was then that he

assumed the title of Genghis Khan, meaning universal leader, marking

the start of the Mongol Empire. The first great khan was able to grasp

power over such varied populations through bloody siege warfare and

elaborate spy systems, which allowed him to better understand his

enemy. He also utilized a lenient policy toward religious and local

traditions, which convinced many people to follow his lead with promises of amnesty and neutrality.

Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan as portrayed in a 14th-century Yuan-era album. He was the first leader of the unified Mongols and first emperor under the Mongolian Empire.

Innovations Under Genghis Khan

As a ruler over a

vast network of tribal groups, Genghis Khan innovated the way he

ruled and garnered power as he expanded his holdings. These unprecedented innovations encouraged a relatively peaceful reign and helped to

develop stabler trading routes and alliances, marking his rule as one of the most successful political entities of the era. He also successfully brought technology, language, and goods farther west. Some of his major accomplishments include:

-

Organizing his

army by dividing it into decimal subsections of 10, 100, 1,000, and

10,000, and discarded the lineage-based, tribal bands that once dominated warfare. -

Founding the

Imperial Guard and rewarding loyalty with high positions as heads of

army units and households no matter the class of the individual. - Proclaiming a new

law of the empire, called the Yassa, which outlawed the theft of property,

fighting amongst the population, and hunting animals during the

breeding season, among many other things. - Forbidding the

selling of women. He also encouraged women to discuss major, public

decisions. Unlike other leaders in the region, Ghengis

allowed his wives to sit at the table with him and encouraged them to

voice their opinions. -

Appointing his

adopted brother as supreme judge, ordering him to keep detailed records of the

empire. -

Decreeing religious

freedom and exempting the poor and the clergy from taxation. Because

of this, Muslims, Buddhists, and Christians from Manchuria, North

China, India, and Persia were more likely to acquiesce to Mongol intrusions and takeovers. -

Encouraging literacy and adopting the Uyghur script, which would form the Empire’s

Uyghur-Mongolian

script.

Destruction and Expansion Under Genghis Khan

Despite his many successful political and social changes, Genghis was also a destructive and intimidating leader. He initially forged the Mongol Empire in Central Asia with the

unification of the Mongol and Turkic confederations on the Mongolian

plateau in 1206. Then Mongol forces invaded westward into Central

Asia including:

- Western Xia Dynasty in 1209

- Kara-Khitan Khanate in 1218

- Khwarazmian Empire

in 1221

These conquests

seriously depopulated large areas of central Asia and northeastern

Iran, complicating the image of Genghis Khan as a peaceful ruler practicing religious

tolerance. Any city or town that resisted the Mongols was subject to

destruction. Each soldier was required to execute a certain number of

persons in cities that did not cooperate. For

example, after the conquest of the city of Urgench, each Mongol

warrior, in an army that might have consisted of 20,000 soldiers, was

required to execute 24 people.

Sack of Baghdad

Illustrations of Mongol advances show the deeply militaristic reality of this empire’s success, and the darker side of Genghis Khan’s rule.

By 1260, the armies of the Mongol Empire had swept across and outward from the Asian steppes. The dark side of Genghis Khan’s rule can be seen in the destruction of ancient and powerful kingdoms in the Middle East, Egypt, and Poland. During the same period, Mongol assaults on China replaced the Sung Dynasty with the Yuan Dynasty. Many local populations in what is now India, Pakistan, and Iran considered the great khan to be a blood-thirsty warlord set on destruction.

The Mongols’ military tactics, based on the swift and ferocious use of mounted cavalry, cannons, and siege warfare crushed even the strongest European and Islamic forces and left a trail of devastation behind. Even populations that appreciated the new legal code and relative religious tolerance did not have much free will when it came to Mongol advances. Many times Jewish kosher traditions and Muslim halal traditions were also cast aside in favor of Mongol dining and social customs.

Genghis Khan died in 1227 under mysterious circumstances in possession of one of the largest empires in history. He left these vast holdings in the hands of his sons and heirs, Ögedei and Jochi, who continued to expand outward with attacks and political alliances in every direction.

13.2.2: Expansion Throughout Eastern Asia

Under Genghis Khan and his son Ögedei, the Mongol Empire conquered both the Western Xia Dynasty and the Jin Dynasty to the west.

Learning Objective

Recall the significance and consequences of the Mongol Empire’s battles with the Western Xia and Jin Dynasties.

Key Points

- Under Genghis Khan, the Mongol Empire conquered the Tanguts’ Western Xia Dynasty in 1209.

- Afterward, Genghis Khan began the conquest of the neighboring Jin Dynasty in 1211.

- The Jin Dynasty would finally be successfully conquered by Genghis’ son, Ögedei Khan, in 1234.

Key Terms

- Zhongdu

-

The capital of the Jin Dynasty before the Mongol attacks, situated where modern-day Beijing sits.

- ethnocide

-

The destruction of a national or localized culture in the wake of a population’s destruction.

- Badger Pass

-

The location of the battle between Genghis Khan’s Mongol Empire and the Jin Dynasty, where the Mongols massacred thousands of Jin troops.

At the time of the political rise of Genghis Khan in 1206 CE, the Mongol Empire shared its western borders with the Western Xia Dynasty of the Tanguts. To the east and south was the Jin Dynasty of northern China. These two regions offered valuable resources and would serve as vassal-states over time as Genghis gained power over these two large territories. His relentless battle tactics also revealed his ruthless viewpoints when it came to disobedient enemy forces and gaining complete control of a region.

Map illustrating the neighboring Xia and Jin regions

These two regions were directly adjacent to Genghis Khan’s newly unified Mongol territories in the late 12th and early 13th centuries.

Conquest of the Western Xia Dynasty

The Western Xia Dynasty (also known as the Xi-Xia Dynasty) was located in what is modern-day northern China and sat along the southern border of the Mongol territories. It emerged in 1038 but often struggled to retain independent status from neighboring dynasties. The Xia Dynasty also shared a complex history with the neighboring Jin Dynasty, even serving as a vassal state to the Jin for a period before the arrival of Mongol forces.

Genghis Khan first planned for war with the Western Xia, correctly believing that the young, more powerful ruler of the Jin Dynasty would not come to the Western Xia Dynasty’s aid. His very first attempt to gain power started in 1205, the year before he was named supreme ruler on Mongol lands, and his initial attacks were based on a flimsy political pretext. However, he realized that this region would be an ideal gateway to conquering the Jin Dynasty to the south and east. Despite initial difficulties in capturing the Western Xia’s well-defended cities, Genghis Khan forced their surrender with multiple siege battles in 1209 and 1210.

Genghis’s relentless battle tactics showed to great effect in the Xia territory. While he initially gained territory in 1209, the second invasion in Western Xia in the 1220s was an example of the bloodshed and slaughter he practiced on cities and populations that did not obey his orders. The population was relatively demolished before his death in 1227 and subsequently under the rule of his son and heir, Ögedei. Some scholars even say this is the first example of ethnocide in history.

Conquest of the Jin Dynasty

The tactics and military might Genghis used in the Western Xia region continued as he went on to conquer the larger and more powerful Jin Dynasty in 1211 CE, beginning a 23-year war known as the Mongol-Jin War. Long before the Mongol invasions, Jin leaders took vassal tribute from the Mongolian tribes along their shared border. These leaders even encouraged disputes between these nomadic tribes in order to bolster their own power along their northern border.

However, the tides for this powerful dynasty decidedly shifted when the war started during the first Mongol invasion. Jin’s army commander made a tactical mistake in not attacking the Mongols at the first opportunity. Instead, he sent a messenger to Mongols. But the messenger defected and told the Mongols that the Jin Dynasty army was waiting for them on the other side of the Badger Pass. This was where the Mongols massacred thousands of Jin troops and began a long and arduous war that would take a heavy toll on the region.

In 1215 CE Genghis captured and sacked the Jin capital of Zhongdu (modern-day Beijing). This forced the Emperor Xuanzong to move his capital south, abandoning the northern half of his kingdom to the Mongols. Between 1232 CE and 1233 CE, Kaifeng fell to the Mongols under the reign of Genghis’ third son, Ögedei Khan. The last major battle between the Jin and the Mongols was the siege of Caizhou in 1234 CE, which marked the collapse of the Jin Dynasty.

The years of war took a heavy toll on the population of the Jin Dynasty, as it had in the Western Xia. Mongol warriors were reported to take the livestock from the small towns and villages along their path and kill the owners.

Despite the hardship of war and the siege and heavy cavalry tactics utilized by Mongol forces, the unifying and centralizing effects of the Mongol Empire created an expansive trade route and opened up these far eastern regions to western influence and goods. More stability along the trade route known as the Silk Road allowed goods and ideas to travel long distances and established a connection between eastern European principalities like the Russian territories.

Jar from the Jin Dynasty

Hunping jar of the Jin Dynasty, with Buddhist figures.

13.2.3: Expansion Throughout Central and Western Asia

Under Genghis Khan, the Mongols, who began using catapaults and gunpowder in their invasions, conquered the Kara-Khitan Khanate and the Khwarazmian Empire.

Learning Objective

Assess the factors in Genghis Khan’s successful conquest of the Khwarazmian Empire and the Kara-Khitan

Key Points

- Under Genghis Khan, the Mongol Empire conquered the Kara-Khitan Khanate in Central Asia in 1218 CE. This was a relatively easy conquest because the prince of Kara-Khitan, Küchlüg, had become unpopular with his people due to his persecution of Islam.

- The empire now had a border with the Khwarazmian Empire, which they proceeded to conquer as well in 1221 CE.

- The Mongol Empire’s conquest of the Khwarazmian Empire saw huge numbers of civilians massacred and enslaved.

- During this time, the empire used catapults to hurl gunpowder bombs. The Mongol Empire is often given credit for introducing gunpowder to Europe.

- By the time of Genghis Khan’s death in 1227 CE, the Mongol Empire was twice the size of the Roman Empire and the Muslim Caliphate.

Key Terms

- catapult

-

A device or weapon for throwing or launching large objects. Used by Genghis Khan during the Mongol invasion of the Khwarazmian Empire.

- Samarkand

-

The capital of the Khwarazm region, which was captured by Mongol forces around 1221.

- gunpowder

-

An explosive substance; can be used to form bombs. Was introduced to Europe by the Mongols.

- huochong

-

A Chinese mortar used in the Central Asia campaign

Genghis Khan created an efficient military regime after his unifying rise to power in the nomadic Mongol territories of northeastern Asia in 1206 CE. These forces were no longer grouped by tribe or familial affiliation, but rather were organized into armies of multiples of ten soldiers that could be sent where needed in the name of Mongol expansion. Genghis Khan sent forces in every direction, including westward into central Asia. While he was fighting the Western Xia and Jin Dynasties in the east, he was also attempting to gain more land to the west in the Kara-Khitan Khanate and the Khwarazmian Empire, regions that comprise modern-day Iran, Iraq, and Uzbekistan.

Conquest of the Kara-Khitan Khanate

The Mongol Empire conquered the Kara-Khitan Khanate, an empire comprised of former nomads in Central Asia, in the years 1216-1218 CE. The khanate was under the rule of Prince Küchlüg, who had converted to Buddhism and had been persecuting the Muslim majority among the Khitan. This alienated him from most of his people, creating ideal circumstances for a takeover by Genghis Khan.

The Kara-Khitai attracted Genghis Khan’s attention when they besieged Almaliq, a city belonging to vassals of the Mongol Empire. Genghis Khan dispatched an army, who, under the command of General Jebe, defeated the Kara-Khitai at their capital, Balasagun, and Küchlüg fled. Jebe gained support from the Kara-Khitan populace by announcing that Küchlüg’s oppressive policy of religious persecution had ended. When his army followed Küchlüg to Kashgar in 1217, the populace revolted and turned on Küchlüg, forcing him to flee again for his life. Jebe pursued Küchlüg into modern Afghanistan. According to Persian historian Ata-Malik Juvayni, a group of hunters caught Küchlüg in 1218 and handed him over to the Mongols, who promptly beheaded him.

With Küchlüg’s death, the Mongol Empire secured control over the Kara-Khitai and surrounding areas. The Mongols now had a firm outpost in Central Asia directly bordering the Khwarazmian Empire, in Greater Iran. Relations with the Khwarazms would quickly break down, leading to the Mongol invasion of that territory in 1219.

Kara-Khitans Hunting

Kara-Khitans using eagles to hunt, painted during the Chinese Song Dynasty.

Conquest of the Khwarazmian Empire

In the early 13th century, the Khwarazmian Empire was governed by Shah Ala ad-Din Muhammad. Genghis Khan saw the potential advantage in Khwarazmia as a commercial trading partner using the Silk Road, and he sent a caravan to establish official trade ties with the empire. However, a Khwarazmian governor attacked the caravan, claiming that it contained spies. Genghis Khan sent a second group of ambassadors to meet the Shah himself instead of the governor. The Shah had all the men shaved and the Muslim ambassador beheaded and sent his head back with the two remaining ambassadors.

Outraged, Genghis Khan organized one of his largest and most brutal invasion campaigns, fought by 200,000 soldiers in three divisions. He left a commander and troops in China, designated his successors to be his family members, and set out for Khwarazmia. Before he left, he divided his empire among his sons and immediate family and declared that his heir should be his charismatic third son, Ögedei. His invasion of Khwarazmia would last from 1219-1221 CE. His son Jochi led the first division into the northeast, and the second division under Jebe marched secretly to the southeast to form, with the first division, a pincer attack on Samarkand. The third division under Genghis Khan and Tolui moved in from the northwest. The Shah’s army, in contrast, was fragmented, a decisive factor in their defeat—the Mongols were not facing a unified defense.

The Mongol tactics were precise and often brutally efficient, including heavy cavalry, siege tactics, and even gunpowder weapons. The attack on the Khwarazm capital, Samarkand, was decisive and left the local population depleted and in tatters. Generally speaking, Mongol forces would enslave or massacre populations after a victorious capture of a city or region, establishing a new rule of law and highlighting Mongol dominance. Legend tells that the often flamboyant Genghis Khan executed the Khwarazm governor by pouring molten silver into his ears and eyes. Eventually the Shah fled rather than surrender, and he died shortly after, possibly killed by the Mongols. After their victory, Genghis Khan ordered two of his generals and their forces to completely destroy the remnants of the empire, including not only royal buildings but entire towns, populations, and even vast swaths of farmland.

The assault on the wealthy trading city of Urgench proved to be the most difficult battle of the Mongol invasion. Mongolian casualties were higher than normal because most battles they fought were in less densely packed urban settings. However, they were successful, and after an extensive invasion such as this one, young women and children were often given to the Mongol soldiers as slaves. Persian scholar Juvayni states that 50,000 Mongol soldiers were given the task of executing 24 Urgench citizens each. If Juvanyi’s estimation is true, 1.2 million people were killed, making it one of the bloodiest invasions in history.

During the invasion of Transoxania in 1219, along with the main Mongol force, Genghis Khan used a Chinese specialist catapult unit in battle, adding to the powerful tactics already in use by Mongol forces. They were used again in 1220 in Transoxania. The Chinese may have used these same catapults to hurl gunpowder bombs. In fact, historians have suggested that the Mongol invasion brought Chinese gunpowder weapons to Central Asia. One of these was the huochong, a Chinese mortar.

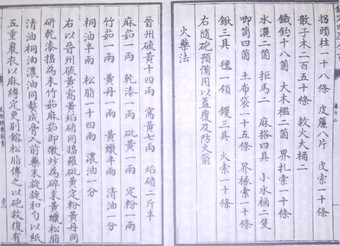

Chinese Formula for Gunpowder

The earliest known written formula for gunpowder, from the Chinese Wujing Zongyao, a military compendium, of 1044 CE.

By the time of Genghis Khan’s death in 1227, the Mongol Empire ruled from the Pacific Ocean to the Caspian Sea, an empire twice the size of the Roman Empire and Muslim Caliphate.

Pushing Farther West

The Mongols conquered the areas today known as Iran, Iraq, Syria, Caucasus and parts of Turkey. Further Mongol raids reached southwards as far as Gaza into the Palestine region in 1260 and 1300. The major battles were the Siege of Baghdad in 1258, when the Mongols sacked the city that for 500 years had been the center of Islamic power, and the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260, when the Muslim Egyptians were for the first time able to stop the Mongol advance.

The Mongols were never able to expand farther west than the Middle East due to a combination of political and environmental factors, such as lack of sufficient grazing room for their horses.

13.3: The Mongol Empire After Genghis Khan

13.3.1: The Mongols in Eastern Europe

Under Ögedei, the Mongol Empire conquered Eastern Europe. Various tactical errors and unexpected cultural and environmental factors stopped the Mongol forces from moving into Western Europe in 1241.

Learning Objective

Recognize the European territories conquered by Ögedei and why the Mongols halted their expansion into Western Europe

Key Points

- Ögedei Khan, Genghis Khan’s third son, ruled the Mongol Empire from 1227 CE-1241 CE.

- Under Ögedei, the Mongol Empire conquered Eastern Europe by invading Russia and Bulgaria; Poland, at the Battle of Legnica; and Hungary, at the Battle of Mohi.

- Changes in the terrain and resources, which limited their cavalry abilities, along with the death of a charismatic leader Ögedei in 1241, brought these forces to a halt before they reached Western Europe.

Key Terms

- steppe

-

The grasslands of Eastern Europe and Asia. Similar to the North American prairie and the African savannah.

- Rus’

-

Early Russia; encompassed modern-day Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Belarus, and the Baltic states.

Expansion of the Mongol Empire Under Ögedei

Ögedei, Genghis Khan’s third son, took over from his father and ruled the Mongol Empire from 1227 CE-1241 CE. One of his most important contributions to the empire was his conquest of Eastern Europe. These conquests involved invasions of Russia, Hungary, Volga Bulgaria, Poland, Dalmatia, and Wallachia. Over the course of four years (1237–1241), the Mongols quickly overtook most of the major eastern European cities, only sparing Novgorod and Pskov. As a result of the successful invasions, many of the conquered territories would become part of the Mongol Empire. This conquered region is sometimes referred to as the Golden Horde.

“Coronation of Ögedei”

“Coronation Of Ögedei,” 1229, by Rashid al-Din.

The operations were masterminded by General Subutai and commanded by Batu Khan and Kadan, both grandsons of Genghis Khan. The Mongols had acquired Chinese gunpowder, which they deployed in battle during the invasion of Europe to great success, in the form of bombs hurled via catapults. The Mongols have been credited for introducing gunpowder and associated weapons into Europe. They were also masters at cavalry invasions and siege warfare, which threatened many of the principalities the Mongols hoped to capture.

Invasion and Conquest of Russian Lands

Ögedei Khan ordered his nephew (and grandson of Genghis Khan) Batu Khan to conquer Russia in 1235. (The territory was then called Rus’ and encompassed modern-day Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Belarus, and the Baltic states. Territories and cities were ruled over by princely dynasties, which often meant these regions were fragmented politically.) The main force arrived at Ryazan in December 1237. Ryazan refused to surrender, and the Mongols sacked it and then stormed through other Russian cities, including Vladimir Suzdal in the north, and Pereyaslav and Chernihiv in the south. Other major Russian cities—such as Torzhok, and Kozelsk—were captured between 1238 and 1240. Some cities, such as Novgorod in the north, were not attacked due to the dense march and forest land surrounding it. However, the princes ruling Novgorod acted as tax collectors for the Mongol Empire in the coming decades.

Afterward, the Mongols turned their attention to the steppe, crushing various tribes and sacking Crimea to the west. They returned to Russia in 1239 and sacked several more cities and finally took the southern Rus’ capital of Kiev, leaving behind their trademark destruction of both the population and city structures. This final attack sealed the Rus’ principalities’ fate, forcing princes to flee their regions or capitulate to Mongol taxation and rule.

Invasion into Central Europe

The Mongols continued to invade Central Europe with three armies. One army defeated the fragmented Poland at the Battle of Legnica in 1241. Two days later the armies regrouped and crushed the Hungarian army at the Battle of Mohi, killing up to a quarter of the population and destroying as much as half of the habitable dwellings. This decisive victory was partially due to the fact that Hungary was unprepared for an invasion and did not having a standing army ready to fight. It took a number of months for the Mongol army to subdue various power centers in Hungary. A major battle called the Mongol’s Siege of Esztergom in the capital of Hungary forced people to flee and a new capital was moved to Budapest. However, the Mongols had a difficult time capturing fortified cities throughout Hungarian territories, which kept a total takeover from occurring. The Hungarian king Bela IV fled to Croatia during the initial attacks on his cities, and fortified structures throughout this territory helped keep the king and the local populations safe. However, Zagreb was sacked and destroyed in pursuit of the fugitive king and further territorial gains.

While the Mongol armies were fighting in Hungary and Croatia, they also pushed their forces into Austria, Dalmatia, and Moravia. Where they found local resistance, they ruthlessly killed the population. Where the locale offered no resistance, they forced the men into servitude in the Mongol army. They also ransacked Moldavia and Wallachia, plundering food stores and leaving the population in a precarious state.

The Battle of Legnica

A depiction of the Battle of Legnica by Matthäus Merian the Elder, painted 1630.

End of the Mongol Advance

Although the Mongol forces were well-versed in cavalry and siege attacks, these two strategies also served as their weak points as they went farther westward. Many people in Hungary, Croatia, and Dalmatia had food stores at the ready for the long siege battles of the Mongol armies. Fortified cities and boggy or mountainous terrain also slowed down the light cavalry of the Mongol forces and gave European cities an advantage. Although politically fractured, European powers were uniting; even Hungarians who had survived the initial attack, or never engaged in battle, had begun a guerilla attack lead by survivors of the Hungarian royal family.

The Klis Fortress in Croatia

This type of rocky, fortified city posed a serious challenge to Mongol forces who were often mounted on horses. This particular city defeated the Mongol army in 1242.

Along with all of these tactical challenges the charismatic Mongol leader, Ögedei, died in December 1241. His death forced the Mongol armies to halt their westward expansion, especially in the face of mounting difficulties, and hasten back the thousands of miles to Karakorum, their capital in Mongolia, to elect his successor. Although the expansion did not extend into Western Europe, the Mongol forces retained power over many major Eastern European cities for many decades. However, after Ögedei’s death, power disputes plagued the Mongol Empire and eventually weakened their extensive hold on such vast territories.

13.3.2: Administrative Reform in the Mongol Empire

Möngke was generally a popular ruler of the Mongol Empire; he met debts, controlled spending, conducted a census, and protected civilians.

Learning Objective

Choose the best summary of Möngke’s achievements

Key Points

- After Ögedei’s death, Genghis Khan’s descendants Güyük and Batu Khan fought about who would rule until Batu Khan’s death, at which point Genghis’ grandson Möngke took control.

- Möngke was generally a popular ruler. He generously met all Güyük’s outstanding debts, an unprecedented move.

- Möngke also forbade extravagant spending, imposed taxes (which incited some rebellions), and punished the unauthorized plundering of civilians. He established the Department of Monetary Affairs and standardized a system of measurement.

- Möngke conducted a census of the Mongol Empire and its land.

Key Terms

- ingot

-

A block of steel, gold, or other metal oblong in shape and used for currency.

- Department of Monetary Affairs

-

Möngke established this body to control the issuance of paper money in order to eliminate the overissue of currency that had been a problem since Ögedei’s reign.

From Ögedei’s death in 1241 CE until 1246 CE the Mongol Empire was ruled under the regency of Ögedei’s widow, Töregene Khatun. She set the stage for the ascension of her son, Güyük, as Great Khan, and he would take control in 1246. He and Ögedei’s nephew Batu Khan (both grandsons of Genghis Khan) fought bitterly for power; Güyük died in 1248 on the way to confront Batu.

Another nephew of Ögedei’s (and so a third grandson of Genghis Khan’s), Möngke, then took the throne in 1251 with Batu’s approval. In 1255, well into Möngke’s reign, Batu had repaired his relationship with the Great Khan and so finally felt secure enough to prepare invasions westward into Europe. Fortunately for the Europeans, however, he died before his plans could be implemented.

The Mongol Empire Under Möngke

Möngke’s rule established some of the most consistent monetary and administrative policies since Genghis Khan. In the mercantile department he:

- Forbade extravagant spending and limited gifts to the princes.

- Made merchants subject to taxes.

- Prohibited the demanding of goods and services from civilian populations by merchants.

- Punished the unauthorized plundering of civilians by generals and princes (including his own son).

In 1253, Möngke established the Department of Monetary Affairs to control the issuance of paper money. This new department contributed to better econimic stability including:

- Limiting the overissue of currency, which had been a problem since Ögedei’s reign.

- Standardizing a system of measurement based on the silver ingot.

- Paying out all debts drawn by high-rank Mongol elites to important foreign and local merchants.

Möngke recognized that if he did not meet his predecessor’s, Güyük’s, financial obligations, it would make merchants reluctant to continue business with the Mongols. Like many other rules around the world at this time, his hope was to take advantage of the budding commercial revolution in Europe and the Middle East. Ata-Malik Juvaini, a 13th-century Persian historian, commented on the virtue of this move, saying, “And from what book of history has it been read or heard…that a king paid the debt of another king? “

The Mongol Empire’s administration followed a trend that was occurring in the Western Europe, in which kings and emperors were finding efficient ways to manage their administrative and legals systems and fund crusades, conquests, and wars. From 1252–1259, Möngke conducted a census of the Mongol Empire including Iran, Afghanistan, Georgia, Armenia, Russia, Central Asia and North China. The new census counted not only households but also the number of men aged 15–60 and the number of fields, livestock, vineyards, and orchards.

Möngke also tried to create a fixed poll tax collected by imperial agents, which could be forwarded to the needy units. He taxed the wealthiest people most severely. But the census and taxation sparked popular riots and resistance in the western districts and in the more independent regions under the Mongol umbrella. These rebellions were ultimately put down, and Möngke would continue to rule.

Expansion and Khanates

At the death of Genghis Khan in 1226, the empire was already large enough that one ruler could not oversee the administrative aspects of each region. Genghis realized this and created appanages, or khanates, for his sons, daughters, and grandsons to rule over in order to keep a consistent rule of law. Möngke’s administrative policies extended to these regions during his reign, often causing local unrest due to Mongol occupation and taxation. Some khanates were more closely linked to centralized Mongol policies than others, depending on their location, who oversaw them, and the amount of resistance in each region.

Painting of the Battle of Mohi in 1241

Möngke might have been present at this battle, which took place in the kingdom of Hungary, during one of the many Mongol invasions and attacks that expanded the Mongol Empire.

It should also be noted that the vast religious and cultural traditions of these khanates, including Islam, Judaism, Taoism, Orthodoxy, and Buddhism, were often at odds with the khanate rulers and their demands. Some of the most essential khanates to exist under Möngke’s administrative years included:

- The Golden Horde, which contained the Rus’ principalities and large chunks of modern-day Eastern Europe, including Ukraine, Belarus, and Romania. Many Russian princes capitulated with Mongol rule and a relatively stable alliance existed in the 1250s in some principalities.

- Chagatai Khanate was a Turkic region which was ruled over by Chagatai, Odegei’s second son, until 1242 at his death. This region was clearly Islamic and functioned as an outlying region of the central Mongol government until 1259, when Möngke died.

- Ilkhanate was the major southwestern khanate of the Mongol Empire and encompassed parts of modern-day Iran, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Turkey and the heartland of Persian culture. Möngke’s brother, Hulagu, ruled over this region and his descendants continued to oversee this khanate into the 14th century.

Möngke’s Death

Möngke died while conducting war in China on August 11, 1259. He was possibly a victim of cholera or dysentery, however there is no confirmed record of the cause of his death. His son Asutai conducted him back to Mongolia to be buried. The ruler’s death sparked the four-year Toluid Civil War between his two younger brothers, Kublai and Ariq Böke, and also spurred on the division of the Mongol Empire.

13.3.3: Kublai Khan

Kublai Khan came to power in 1260. By 1271 he had renamed the Empire the Yuan Dynasty and conquered the Song dynasty and with it, all of China. However, Chinese forces ultimately overthrew the Mongols to form the Ming Dynasty.

Learning Objective

Identify Kublai Khan’s most significant achievements

Key Points

- Möngke’s death led to civil war (or Toluid Civil War) between his two younger brothers; ultimately, Kublai Khan emerged victorious and renamed the empire as the Yuan Dynasty in 1271.

- Kublai also renamed himself Emperor of China in order to win over millions of Chinese subjects.

- Ultimately, under Kublai Khan, the Mongols were the first non-Chinese people to conquer all of China. However, their conquests of Japan and Java failed.

- At the time of Kublai’s death, the Mongol Empire fractured into four separate empires; this made it easy for the Han Chinese to overthrow them in 1368 and establish the Ming Dynasty.

Möngke’s death in 1259 led to civil war (often referred to as the Toluid Civil War) between his two younger brothers, Kublai Khan and Ariq Böke. Kublai Khan emerged victorious and established the Yuan Dynasty in China in 1271, perhaps the Mongols’ greatest triumph, though it would eventually be overthrown in 1368 by the native Han Chinese, who would launch their own Ming Dynasty.

Kublai Khan

A portrait of a young Kublai Khan by Anige, a Nepali artist in Kublai’s court.

Establishment of the Yuan Dynasty

After Kublai took over control of the Chinese territories with the blessings of Möngke Khan around 1251, he sought to establish a firmer hold on these vast regions. Rivaling dynasties loomed throughout the Chinese territories making for a contentious political background to Kublai’s rule. His greatest obstacle was the powerful Song dynasty in the south. He stabilized the northern regions by placing a hostage puppet leader in Korea named Wonjong in 1259. After the death of Möngke in that same year, and the following civil war, Kublai was named the Great Khan and successor of Möngke. This new powerful position allowed Kublai to oversee uprisings and wars between the western khanates and assist rulers (often family members) to oversee these regions. However, his tenuous hold in the east occupied most of his resources.

In 1271, as he continued to consolidate his power over the vast and varying Chinese subjects and outlying regions, Kublai Khan renamed his khanate the Yuan Dynasty. His newly named dynasty appeared to be successful after the fall of the major southern center Xiangyang in 1273 to Mongol forces after five years of struggle. The final piece of the puzzle for Kublai was the conquest of the Song Dynasty in southern China. He finally garnered this sought-after southern region in 1276 and the last Song emperor died in 1279 after years of costly battles. With this success, the Mongols became the first non-Chinese people to conquer all of the Chinese territories. Kublai moved his headquarters to Dadu, what later became the modern city of Beijing. His establishment of a capital there was a controversial move to many Mongols who accused him of being too closely tied to Chinese culture. However, the Yuan Dynasty often functioned as an independent khanate from the rest of the western Mongol-dominated regions.

Yuan Dynasty circa 1292

The sheer scale of this khanate required extensive military support and often strained the Mongol treasury in order to keep populations under its influence.

Extended Invasions

Kublai Khan’s costly invasions of many territories in the east did not go smoothly and some went on for many years, draining the Mongol treasury and utilizing precious resources. Although the invasions of Burma in 1277, 1283, and 1287 forced the population to eventually capitulate, they were never more than a vassal state. Similarly, the Yuan forces invaded Sakhalin Island off the coast of modern-day Russia multiple times between 1264 and 1308, and the various tribal groups also eventually became a vassals after long years of turmoil. Southern Asian regions often agreed to Yuan rule and taxation only in the face of more bloodshed and terror. Conversely, Mongol invasions of Japan (1274 and 1280) and Java (1293) under Kublai Khan ultimately failed and illustrated the costly effects of constant invasive military tactics.

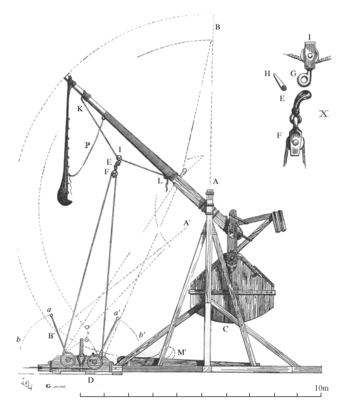

Yuan Dynasty Administration

Kublai Khan made significant reforms to existing institutions under the Yuan Dynasty. He divided the Dynasty’s territory into a central region and peripheral regions that were under the control of various officials. He created an academy, offices, trade ports and canals, and sponsored arts and science. Mongol records also list 20,166 public schools created during his reign. He also, along with engineers, invented the Muslim trebuchet (hui-hui pao), a counterweight-based weapon that was highly successful in battle.

He also continued to welcome trade and travel throughout his empire. Marco Polo, Marco Polo’s father (an Italian merchant), and his father’s trade partner traveled to China during this time. They met Kublai Khan and lived amongst his court to establish trade relations. Polo generally praised the wealth and extravagance of Khan and the Mongol Empire. Some historians also speculate that trade was so accessible between the empire and Europe, that it may have contributed to the flow of disease, especially the black plague in the mid-1300s.

Trebuchet

The scheme of the “Muslim trebuchet” (hui-hui pao), invented during Kublai Khan’s rule.

By the time of Kublai’s death in 1294, the Mongol Empire had fractured into four separate empires, which were based on administrative zones Genghis had created. The four empires were known as khanates, each pursuing its own separate interests and objectives: the Golden Horde Khanate in the northwest, the Chagatai Khanate in the west, the Ilkhanate in the southwest, and the Yuan Dynasty, based in modern-day Beijing. In 1304, the three western khanates briefly accepted the rule of the Yuan Dynasty in name, but when the Dynasty was overthrown by the Han Chinese Ming Dynasty in 1368, and with increasing local unrest in the Golden Horde, the Mongol Empire finally dissolved.