9.1: Byzantium: The New Rome

9.1.1: Naming of the Byzantine Empire

While the Western Roman Empire fell, the Eastern Roman Empire, now known as the Byzantine Empire, thrived.

Learning Objective

Describe identifying characteristics of the Byzantine Empire

Key Points

- While the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 CE, the Eastern Roman Empire, centered on the city of Constantinople, survived and thrived.

- After the Eastern Roman Empire’s much later fall in 1453 CE, western scholars began calling it the “Byzantine Empire” to emphasize its distinction from the earlier, Latin-speaking Roman Empire centered on Rome.

- The “Byzantine Empire” is now the standard term used among historians to refer to the Eastern Roman Empire.

- Although the Byzantine Empire had a multi-ethnic character during most of its history and preserved Romano-Hellenistic traditions, it became identified with its increasingly predominant Greek element and its own unique cultural developments.

Key Term

- Constantinople

-

Formerly Byzantium, the capital of the Byzantine Empire as established by its first emperor, Constantine the Great. (Today the city is known as Istanbul.)

The Byzantine Empire, sometimes referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire in the east during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, originally founded as Byzantium). It survived the fragmentation and fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE, and continued to exist for an additional thousand years until it fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. During most of its existence, the empire was the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in Europe. Both “Byzantine Empire” and “Eastern Roman Empire” are historiographical terms created after the end of the realm; its citizens continued to refer to their empire as the Roman Empire, and thought of themselves as Romans. Although the people living in the Eastern Roman Empire referred to themselves as Romans, they were distinguished by their Greek heritage, Orthodox Christianity, and their regional connections. Over time, the culture of the Eastern Roman Empire transformed. Greek replaced Latin as the language of the empire. Christianity became more important in daily life, although the culture’s pagan Roman past still exerted an influence.

Several signal events from the 4th to 6th centuries mark the period of transition during which the Roman Empire’s Greek east and Latin west divided. Constantine I (r. 324-337) reorganized the empire, made Constantinople the new capital, and legalized Christianity. Under Theodosius I (r. 379-395), Christianity became the empire’s official state religion, and other religious practices were proscribed. Finally, under the reign of Heraclius (r. 610-641), the empire’s military and administration were restructured and adopted Greek for official use instead of Latin. Thus, although the Roman state continued and Roman state traditions were maintained, modern historians distinguish Byzantium from ancient Rome insofar as it was centered on Constantinople, oriented towards Greek rather than Latin culture, and characterized by Orthodox Christianity.

Just as the Byzantine Empire represented the political continuation of the Roman Empire, Byzantine art and culture developed directly out of the art of the Roman Empire, which was itself profoundly influenced by ancient Greek art. Byzantine art never lost sight of this classical heritage. For example, the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, was adorned with a large number of classical sculptures, although they eventually became an object of some puzzlement for its inhabitants. And indeed, the art produced during the Byzantine Empire, although marked by periodic revivals of a classical aesthetic, was above all marked by the development of a new aesthetic. Thus, although the Byzantine Empire had a multi-ethnic character during most of its history, and preserved Romano-Hellenistic traditions, it became identified by its western and northern contemporaries with its increasingly predominant Greek element and its own unique cultural developments.

Map of Constantinople

A map of Constantinople, the capital and founding city of the Byzantine Empire, drawn in 1422 CE by Florentine cartographer Cristoforo Buondelmonti. This is the oldest surviving map of the city and the only one that predates the Turkish conquest of the city in 1453 CE.

Nomenclature

The first use of the term “Byzantine” to label the later years of the Roman Empire was in 1557, when the German historian Hieronymus Wolf published his work, Corpus Historiæ Byzantinæ, a collection of historical sources. The term comes from “Byzantium,” the name of the city of Constantinople before it became Constantine’s capital. This older name of the city would rarely be used from this point onward except in historical or poetic contexts. However, it was not until the mid-19th century that the term came into general use in the western world; calling it the “Byzantine Empire” helped to emphasize its differences from the earlier Latin-speaking Roman Empire, centered on Rome.

The term “Byzantine” was also useful to the many western European states that also claimed to be the true successors of the Roman Empire, as it was used to delegitimize the claims of the Byzantines as true Romans. In modern times, the term “Byzantine” has also come to have a pejorative sense, used to describe things that are overly complex or arcane. “Byzantine diplomacy” has come to mean excess use of trickery and behind-the-scenes manipulation. These are all based on medieval stereotypes about the Byzantine Empire that developed as western Europeans came into contact with the Byzantines, and were perplexed by their more structured government.

No such distinction existed in the Islamic and Slavic worlds, where the empire was more straightforwardly seen as the continuation of the Roman Empire. In the Islamic world, the Roman Empire was known primarily as Rûm. The name millet-i Rûm, or “Roman nation,” was used by the Ottomans through the 20th century to refer to the former subjects of the Byzantine Empire, that is, the Orthodox Christian community within Ottoman realms.

9.1.2: The Eastern Roman Empire, Constantine the Great, and Byzantium

The Christian, Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire had its capital at Constantinople, established by Emperor Constantine the Great.

Learning Objective

Explain the role of Constantine in Byzantine Empire history

Key Points

- The Byzantine Empire (the Eastern Roman Empire) was distinct from the Western Roman Empire in several ways; most importantly, the Byzantines were Christians and spoke Greek instead of Latin.

- The founder of the Byzantine Empire and its first emperor, Constantine the Great, moved the capital of the Roman Empire to the city of Byzantium in 330 CE, and renamed it Constantinople.

- Constantine the Great also legalized Christianity, which had previously been persecuted in the Roman Empire. Christianity would become a major element of Byzantine culture.

- Constantinople became the largest city in the empire and a major commercial center, while the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 CE.

Key Terms

- Christianity

-

An Abrahamic religion based on the teachings of Jesus Christ and various scholars who wrote the Christian Bible. It was legalized in the Byzantine Empire by Constantine the Great, and the religion became a major element of Byzantine culture.

- Germanic barbarians

-

An uncivilized or uncultured person, originally compared to the hellenistic Greco-Roman civilization; often associated with fighting or other such shows of strength.

Constantine the Great and the Beginning of Byzantium

It is a matter of debate when the Roman Empire officially ended and transformed into the Byzantine Empire. Most scholars accept that it did not happen at one time, but that it was a slow process; thus, late Roman history overlaps with early Byzantine history. Constantine I (“the Great”) is usually held to be the founder of the Byzantine Empire. He was responsible for several major changes that would help create a Byzantine culture distinct from the Roman past.

As emperor, Constantine enacted many administrative, financial, social, and military reforms to strengthen the empire. The government was restructured and civil and military authority separated. A new gold coin, the solidus, was introduced to combat inflation. It would become the standard for Byzantine and European currencies for more than a thousand years. As the first Roman emperor to claim conversion to Christianity, Constantine played an influential role in the development of Christianity as the religion of the empire. In military matters, the Roman army was reorganized to consist of mobile field units and garrison soldiers capable of countering internal threats and barbarian invasions. Constantine pursued successful campaigns against the tribes on the Roman frontiers—the Franks, the Alamanni, the Goths, and the Sarmatians—, and even resettled territories abandoned by his predecessors during the turmoil of the previous century.

The age of Constantine marked a distinct epoch in the history of the Roman Empire. He built a new imperial residence at Byzantium and renamed the city Constantinople after himself (the laudatory epithet of “New Rome” came later, and was never an official title). It would later become the capital of the empire for over one thousand years; for this reason the later Eastern Empire would come to be known as the Byzantine Empire. His more immediate political legacy was that, in leaving the empire to his sons, he replaced Diocletian’s tetrarchy (government where power is divided among four individuals) with the principle of dynastic succession. His reputation flourished during the lifetime of his children, and for centuries after his reign. The medieval church upheld him as a paragon of virtue, while secular rulers invoked him as a prototype, a point of reference, and the symbol of imperial legitimacy and identity.

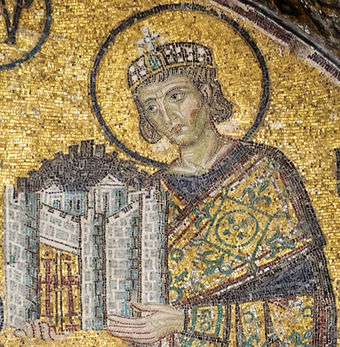

Constantine the Great

Byzantine Emperor Constantine the Great presents a representation of the city of Constantinople as tribute to an enthroned Mary and Christ Child in this church mosaic. St Sophia, c. 1000 CE.

Constantinople and Civil Reform

Constantine moved the seat of the empire, and introduced important changes into its civil and religious constitution. In 330, he founded Constantinople as a second Rome on the site of Byzantium, which was well-positioned astride the trade routes between east and west; it was a superb base from which to guard the Danube river, and was reasonably close to the eastern frontiers. Constantine also began the building of the great fortified walls, which were expanded and rebuilt in subsequent ages. J. B. Bury asserts that “the foundation of Constantinople […] inaugurated a permanent division between the Eastern and Western, the Greek and the Latin, halves of the empire—a division to which events had already pointed—and affected decisively the whole subsequent history of Europe.”

Constantine built upon the administrative reforms introduced by Diocletian. He stabilized the coinage (the gold solidus that he introduced became a highly prized and stable currency), and made changes to the structure of the army. Under Constantine, the empire had recovered much of its military strength and enjoyed a period of stability and prosperity. He also reconquered southern parts of Dacia, after defeating the Visigoths in 332, and he was planning a campaign against Sassanid Persia as well. To divide administrative responsibilities, Constantine replaced the single praetorian prefect, who had traditionally exercised both military and civil functions, with regional prefects enjoying civil authority alone. In the course of the 4th century, four great sections emerged from these Constantinian beginnings, and the practice of separating civil from military authority persisted until the 7th century.

Constantine and Christianity

Constantine was the first emperor to stop Christian persecutions and to legalize Christianity, as well as all other religions and cults in the Roman Empire.

In February 313, Constantine met with Licinius in Milan, where they developed the Edict of Milan. The edict stated that Christians should be allowed to follow the faith without oppression. This removed penalties for professing Christianity, under which many had been martyred previously, and returned confiscated Church property. The edict protected from religious persecution not only Christians but all religions, allowing anyone to worship whichever deity they chose.

Scholars debate whether Constantine adopted Christianity in his youth from his mother, St. Helena,, or whether he adopted it gradually over the course of his life. According to Christian writers, Constantine was over 40 when he finally declared himself a Christian, writing to Christians to make clear that he believed he owed his successes to the protection of the Christian High God alone. Throughout his rule, Constantine supported the Church financially, built basilicas, granted privileges to clergy (e.g. exemption from certain taxes), promoted Christians to high office, and returned property confiscated during the Diocletianic persecution. His most famous building projects include the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and Old Saint Peter’s Basilica.

The reign of Constantine established a precedent for the position of the emperor as having great influence and ultimate regulatory authority within the religious discussions involving the early Christian councils of that time (most notably, the dispute over Arianism, and the nature of God). Constantine himself disliked the risks to societal stability that religious disputes and controversies brought with them, preferring where possible to establish an orthodoxy. One way in which Constantine used his influence over the early Church councils was to seek to establish a consensus over the oft debated and argued issue over the nature of God. In 325, he summoned the Council of Nicaea, effectively the first Ecumenical Council. The Council of Nicaea is most known for its dealing with Arianism and for instituting the Nicene Creed, which is still used today by Christians.

The Fall of the Western Roman Empire

After Constantine, few emperors ruled the entire Roman Empire. It was too big and was under attack from too many directions. Usually, there was an emperor of the Western Roman Empire ruling from Italy or Gaul, and an emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire ruling from Constantinople. While the Western Empire was overrun by Germanic barbarians (its lands in Italy were conquered by the Ostrogoths, Spain was conquered by the Visigoths, North Africa was conquered by the Vandals, and Gaul was conquered by the Franks), the Eastern Empire thrived. Constantinople became the largest city in the empire and a major commercial center. In 476 CE, the last Western Roman Emperor was deposed and the Western Roman Empire was no more. Thus the Eastern Roman Empire was the only Roman Empire left standing.

9.1.3: Justinian and Theodora

Emperor Justinian was responsible for substantial expansion, a legal code, and the Hagia Sophia, but suffered defeats against the Persians.

Learning Objective

Discuss the accomplishments and failures of Emperor Justinian the Great

Key Points

- Emperor Justinian the Great was responsible for substantial expansion of the Byzantine Empire, and for conquering Africa, Spain, Rome, and most of Italy.

- Justinian was responsible for the construction of the Hagia Sophia, the center of Christianity in Constantinople. Even today, the Hagia Sophia is recognized as one of the greatest buildings in the world.

- Justinian also systematized the Roman legal code that served as the basis for law in the Byzantine Empire.

- After a plague reduced the Byzantine population, they lost Rome and Italy to the Ostrogoths, and several important cities to the Persians.

Key Terms

- Hagia Sophia

-

A church built by Byzantine Emperor Justinian; the center of Christianity in Constantinople and one of the greatest buildings in the world to this day. It is now a mosque in the Muslim Istanbul.

- Nika riots

-

When angry racing fans, already angry over rising taxes, became enraged at Emperor Justinian for arresting two popular charioteers, and tried to depose him in 532 CE.

Byzantine Empire from Constantine to Justinian

One of Constantine’s successors, Theodosius I (379-395), was the last emperor to rule both the Eastern and Western halves of the empire. In 391 and 392, he issued a series of edicts essentially banning pagan religion. Pagan festivals and sacrifices were banned, as was access to all pagan temples and places of worship. The state of the empire in 395 may be described in terms of the outcome of Constantine’s work. The dynastic principle was established so firmly that the emperor who died in that year, Theodosius I, could bequeath the imperial office jointly to his sons, Arcadius in the East and Honorius in the West.

The Eastern Empire was largely spared the difficulties faced by the west in the third and fourth centuries, due in part to a more firmly established urban culture and greater financial resources, which allowed it to placate invaders with tribute and pay foreign mercenaries. Throughout the fifth century, various invading armies overran the Western Empire but spared the east. Theodosius II further fortified the walls of Constantinople, leaving the city impervious to most attacks; the walls were not breached until 1204.

To fend off the Huns, Theodosius had to pay an enormous annual tribute to Attila. His successor, Marcian, refused to continue to pay the tribute, but Attila had already diverted his attention to the west. After his death in 453, the Hunnic Empire collapsed, and many of the remaining Huns were often hired as mercenaries by Constantinople.

Leo I succeeded Marcian as emperor, and after the fall of Attila, the true chief in Constantinople was the Alan general, Aspar. Leo I managed to free himself from the influence of the non-Orthodox chief by supporting the rise of the Isaurians, a semi-barbarian tribe living in southern Anatolia. Aspar and his son, Ardabur, were murdered in a riot in 471, and henceforth, Constantinople restored Orthodox leadership for centuries.

When Leo died in 474, Zeno and Ariadne’s younger son succeeded to the throne as Leo II, with Zeno as regent. When Leo II died later that year, Zeno became emperor. The end of the Western Empire is sometimes dated to 476, early in Zeno’s reign, when the Germanic Roman general, Odoacer, deposed the titular Western Emperor Romulus Augustulus, but declined to replace him with another puppet.

Emperor Justinian I

In 527 CE, Justinian I came to the throne in Constantinople. He dreamed of reconquering the lands of the Western Roman Empire and ruling a single, united Roman Empire from his seat in Constantinople.

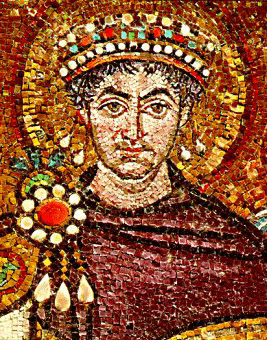

Emperor Justinian

Byzantine Emperor Justinian I depicted on one of the famous mosaics of the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna.

The western conquests began in 533, as Justinian sent his general, Belisarius, to reclaim the former province of Africa from the Vandals, who had been in control since 429 with their capital at Carthage. Belisarius successfully defeated the Vandals and claimed Africa for Constantinople. Next, Justinian sent him to take Italy from the Ostrogoths in 535 CE. Belisarius defeated the Ostrogoths in a series of battles and reclaimed Rome. By 540 CE, most of Italy was in Justinian’s hands. He sent another army to conquer Spain.

The Byzantine Empire under Justinian

The Byzantine Empire at its greatest extent, in 555 CE under Justinian the Great.

Accomplishments in Byzantium

Justinian also undertook many important projects at home. Much of Constantinople was burned down early in Justinian’s reign after a series of riots called the Nika riots, in 532 CE, when angry racing fans became enraged at Justinian for arresting two popular charioteers (though this was really just the last straw for a populace increasingly angry over rising taxes) and tried to depose him. The riots were put down, and Justinian set about rebuilding the city on a grander scale. His greatest accomplishment was the Hagia Sophia, the most important church of the city. The Hagia Sophia was a staggering work of Byzantine architecture, intended to awe all who set foot in the church. It was the largest church in the world for nearly a thousand years, and for the rest of Byzantine history it was the center of Christian worship in Constantinople.

The Hagia Sophia

Byzantine Emperor Justinian built the Greek Orthodox Church of the Holy Wisdom of God, the Hagia Sophia, which was completed in only four and a half years (532 CE-537 CE). Even now, it is universally acknowledged as one of the greatest buildings in the world.

Emperor Justinian’s most important contribution, perhaps, was a unified Roman legal code. Prior to his reign, Roman laws had differed from region to region, and many contradicted one another. The Romans had attempted to systematize the legal code in the fifth century but had not completed the effort. Justinian set up a commission of lawyers to put together a single code, listing each law by subject so that it could be easily referenced. This not only served as the basis for law in the Byzantine Empire, but it was the main influence on the Catholic Church’s development of canon law, and went on to become the basis of law in many European countries. Justinian’s law code continues to have a major influence on public international law to this day.

The impact of a more unified legal code and military conflicts was the increased ability for the Byzantine Empire to establish trade and improve their economic standing. Byzantine merchants traded not only all over the Mediterranean region, but also throughout regions to the east. These included areas around the Black Sea, the Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean.

Theodora

Theodora was empress of the Byzantine Empire and the wife of Emperor Justinian I. She was one of the most influential and powerful of the Byzantine empresses. Some sources mention her as empress regnant, with Justinian I as her co-regent. Along with her husband, she is a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church, commemorated on November 14.

Theodora participated in Justinian’s legal and spiritual reforms, and her involvement in the increase of the rights of women was substantial. She had laws passed that prohibited forced prostitution and closed brothels. She created a convent on the Asian side of the Dardanelles called the Metanoia (Repentance), where the ex-prostitutes could support themselves. She also expanded the rights of women in divorce and property ownership, instituted the death penalty for rape, forbade exposure of unwanted infants, gave mothers some guardianship rights over their children, and forbade the killing of a wife who committed adultery.

Justinian’s Difficulties

A terrible plague swept through the empire, killing Theodora and almost killing him. The plague wiped out huge numbers of the empire’s population, leaving villages empty and crops unharvested. The army was also afflicted, and the Ostrogoths were able to effectively regain Italy in 546 CE, through guerrilla warfare against the Byzantine occupiers.

With Justinian’s army bogged down fighting in Italy, the empire’s defenses against the Persians on its eastern frontiers were weakened. In the Roman-Persian Wars, the Persians invaded and destroyed a number of important cities. Justinian was forced to establish a humiliating 50-year peace treaty with them in 561 CE.

Still, Justinian kept the empire from collapse. He sent a new general, Narses, to Italy with a small force. Narses finally defeated the Ostrogoths and drove them back out of Italy. By the time the war was over, Italy, once one of the most prosperous lands in the ancient world, was wrecked. The city of Rome changed hands multiple times, and most of the cities of Italy were abandoned or fell into a long period of decline. The impoverishment of Italy and the weakened Byzantine military made it impossible for the empire to hold the peninsula. Soon a new Germanic tribe, the Lombards, came in and conquered most of Italy, though Rome, Naples, and Ravenna remained isolated pockets of Byzantine control. At the same time, another new barbarian enemy, the Slavs, appeared from north of the Danube. They devastated Greece and the Balkans, and in the absence of strong Byzantine military might, they settled in small communities in these lands.

9.1.4: The Justinian Code

Justinian I achieved lasting fame through his judicial reforms, particularly through the complete revision of all Roman law that was compiled in what is known today as the Corpus juris civilis.

Learning Objective

Explain the historical significance of Justinian’s legal reforms

Key Points

- Shortly after Justinian became emperor in 527, he decided the empire’s legal system needed repair.

- Early in his reign, Justinian appointed an official, Tribonian, to oversee this task.

- The project as a whole became known as Corpus juris civilis, or the Justinian Code.

- It consists of the Codex Iustinianus, the Digesta, the Institutiones, and the Novellae.

- Many of the laws contained in the Codex were aimed at regulating religious practice.

- The Corpus formed the basis not only of Roman jurisprudence (including ecclesiastical Canon Law), but also influenced civil law throughout the Middle Ages and into modern nation states.

Key Terms

- Corpus juris civilis

-

The modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Eastern Roman Emperor.

- Justinian I

-

A Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565. During his reign, he sought to revive the empire’s greatness and reconquer the lost western half of the historical Roman Empire; he also enacted important legal codes.

Byzantine Emperor Justinian I achieved lasting fame through his judicial reforms, particularly through the complete revision of all Roman law, something that had not previously been attempted. There existed three codices of imperial laws and other individual laws, many of which conflicted or were out of date. The total of Justinian’s legislature is known today as the Corpus juris civilis.

The work as planned had three parts:

- Codex: a compilation, by selection and extraction, of imperial enactments to date, going back to Hadrian in the 2nd century CE.

- Digesta: an encyclopedia composed of mostly brief extracts from the writings of Roman jurists. Fragments were taken out of various legal treatises and opinions and inserted in the Digesta.

- Institutiones: a student textbook, mainly introducing the Codex, although it has important conceptual elements that are less developed in the Codex or the Digesta.

All three parts, even the textbook, were given force of law. They were intended to be, together, the sole source of law; reference to any other source, including the original texts from which the Codex and the Digesta had been taken, was forbidden. Nonetheless, Justinian found himself having to enact further laws, and today these are counted as a fourth part of the Corpus, the Novellae Constitutiones. As opposed to the rest of the Corpus, the Novellae appeared in Greek, the common language of the Eastern Empire.

The work was directed by Tribonian, an official in Justinian’s court. His team was authorized to edit what they included. How far they made amendments is not recorded and, in the main, cannot be known because most of the originals have not survived. The text was composed and distributed almost entirely in Latin, which was still the official language of the government of the Byzantine Empire in 529-534, whereas the prevalent language of merchants, farmers, seamen, and other citizens was Greek.

Many of the laws contained in the Codex were aimed at regulating religious practice, included numerous provisions served to secure the status of Christianity as the state religion of the empire, uniting church and state, and making anyone who was not connected to the Christian church a non-citizen. It also contained laws forbidding particular pagan practices; for example, all persons present at a pagan sacrifice may be indicted as if for murder. Other laws, some influenced by his wife, Theodora, include those to protect prostitutes from exploitation, and women from being forced into prostitution. Rapists were treated severely. Further, by his policies, women charged with major crimes should be guarded by other women to prevent sexual abuse; if a woman was widowed, her dowry should be returned; and a husband could not take on a major debt without his wife giving her consent twice.

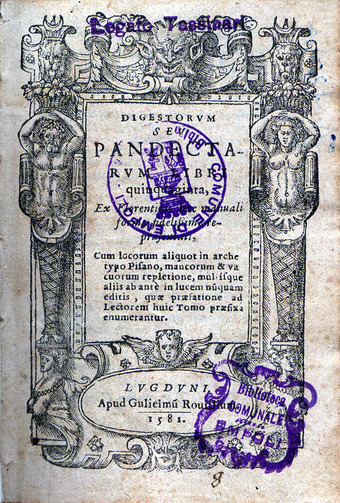

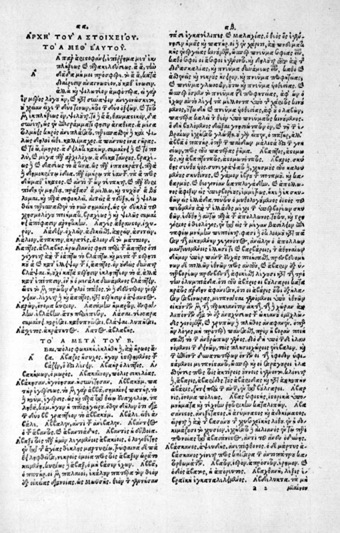

Justinian Digesta

A later copy of Justinian’s Digesta: Digestorum, seu Pandectarum libri quinquaginta. Lugduni apud Gulielmum Rouillium, 1581. From Biblioteca Comunale “Renato Fucini” di Empoli.

Legacy

The Corpus forms the basis of Latin jurisprudence (including ecclesiastical Canon Law) and, for historians, provides a valuable insight into the concerns and activities of the later Roman Empire. As a collection, it gathers together the many sources in which the laws and the other rules were expressed or published (proper laws, senatorial consults, imperial decrees, case law, and jurists’ opinions and interpretations). It formed the basis of later Byzantine law, as expressed in the Basilika of Basil I and Leo VI the Wise. The only western province where the Justinian Code was introduced was Italy, from where it was to pass to western Europe in the 12th century, and become the basis of much European law code. It eventually passed to eastern Europe, where it appeared in Slavic editions, and it also passed on to Russia.

It was not in general use during the Early Middle Ages. After the Early Middle Ages, interest in it revived. It was “received” or imitated as private law, and its public law content was quarried for arguments by both secular and ecclesiastical authorities. The revived Roman law, in turn, became the foundation of law in all civil law jurisdictions. The provisions of the Corpus Juris Civilis also influenced the canon law of the Roman Catholic Church; it was said that ecclesia vivit lege romana—the church lives by Roman law. Its influence on common law legal systems has been much smaller, although some basic concepts from the Corpus have survived through Norman law—such as the contrast, especially in the Institutes, between “law” (statute) and custom. The Corpus continues to have a major influence on public international law. Its four parts thus constitute the foundation documents of the western legal tradition.

9.2: The Heraclian and Isaurian Dynasties

9.2.1: Emperor Heracluis

Emperor Heraclius defended the Byzantine Empire from the Persians, but lost the reconquered land to the Arabs shortly thereafter.

Learning Objective

Identify the reason for the reduction in size of the Byzantine Empire

Key Points

- After Justinian, the Byzantine Empire continued to lose land to the Persians.

- Emperor Heraclius seized the throne in 610 CE, and beat back the Persians by 628 CE.

- However, after Heraclius’ victory against the Persians, he had taken such losses that he was unable to defend the empire against the Arabs, and so they again lost the lands they had just reconquered by 641 CE.

- Heraclius tried to unite all of the various religious factions within the empire with a new formula that was more inclusive and more elastic, called monothelitism, which was eventually deemed heretical by all factions.

Key Terms

- Muhammad

-

The central figure of Islam, widely regarded as its founder.

- Monothelitism

-

The view that Jesus Christ has two natures but only one will, a doctrine developed during Heraclius’ rule to bring unity to the Church.

Conflict with the Persians and Chaos in the Empire

Ever since the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire had continued to see western Europe as rightfully Imperial territory. However, only Justinian I attempted to enforce this claim with military might. Temporary success in the west was achieved at the cost of Persian dominance in the east, where the Byzantines were forced to pay tribute to avert war.

However, after Justinian’s death, much of newly recovered Italy fell to the Lombards, and the Visigoths soon reduced the imperial holdings in Spain. At the same time, wars with the Persian Empire brought no conclusive victory. In 591 however, the long war was ended with a treaty favorable to Byzantium, which gained Armenia. Thus, after the death of Justinian’s successor, Tiberius II, Maurice sought to restore the prestige of the Empire.

Even though the empire had gained smaller successes over the Slavs and Avars in pitched battles across the Danube, both enthusiasm for the army and faith in the government had lessened considerably. Unrest had reared its head in Byzantine cities as social and religious differences manifested themselves into Blue and Green factions that fought each other in the streets. The final blow to the government was a decision to cut the pay of its army in response to financial strains. The combined effect of an army revolt led by a junior officer named Phocas and major uprisings by the Greens and Blues forced Maurice to abdicate. The Senate approved Phocas as the new emperor, and Maurice, the last emperor of the Justinian Dynasty, was murdered along with his four sons.

The Persian King Khosrau II responded by launching an assault on the empire, ostensibly to avenge Maurice, who had earlier helped him to regain his throne. Phocas was already alienating his supporters with his repressive rule (introducing torture on a large scale), and the Persians were able to capture Syria and Mesopotamia by 607.

While the Persians were making headway in their conquest of the eastern provinces, Phocas chose to divide his subjects, rather than unite them against the threat of the Persians. Perhaps seeing his defeats as divine retribution, Phocas initiated a savage and bloody campaign to forcibly convert the Jews to Christianity. Persecutions and alienation of the Jews, a frontline people in the war against the Persians helped drive them into aiding the Persian conquerors. As Jews and Christians began tearing each other apart, some fled the butchery into Persian territory. Meanwhile, it appears that the disasters befalling the empire led the emperor into a state of paranoia.

The Heraclian Dynasty Under Heraclius

Due to the overwhelming crises that had pitched the empire into chaos, Heraclius the Younger now attempted to seize power from Phocas in an effort to better Byzantium’s fortunes. As the empire was led into anarchy, the Exarchate of Carthage remained relatively out of reach of Persian conquest. Far from the incompetent Imperial authority of the time, Heraclius, the Exarch of Carthage, with his brother Gregorius, began building up his forces to assault Constantinople. In 608, after cutting off the grain supply to the capital from his territory, Heraclius led a substantial army and a fleet to restore order in the Empire. The reign of Phocas officially ended in his execution, and the crowning of Heraclius by the Patriarch of Constantinople two days later on October 5, 610. After marrying his wife in an elaborate ceremony and being crowned by the Patriarch, the 36-year-old Heraclius set out to perform his work as emperor. The early portion of his reign yielded results reminiscent of Phocas’ reign, with respect to trouble in the Balkans.

To recover from a seemingly endless string of defeats, Heraclius drew up a reconstruction plan of the military, financing it by fining those accused of corruption, increasing taxes, and debasing the currency to pay more soldiers and forced loans.

Instead of facing the waves of invading Persians, he went around them, sailing over the Black Sea and regrouping in Armenia, where he found many Christian allies. From there, he invaded the Persian Empire. By fighting behind enemy lines, he caused the Persians to retreat from Byzantine lands. He defeated every Persian army sent against him and then threatened the Persian capital. In a panic, the Persians killed their king and replaced him with a new ruler who was willing to negotiate with the Byzantines. In 628 CE, the war ended with Heraclius’ defeat of the Persians.

Emperor Heraclius

A plaque depicting Byzantine Emperor Heraclius overcoming Persian King Khosrau II, c. 1160-1170 CE.

The Arab Invasion

By this time, it was generally expected by the Byzantine populace that the emperor would lead Byzantium into a new age of glory. However, all of Heraclius’ achievements would come to naught, when, in 633, the Byzantine-Arab Wars began.

On June 8, 632, the Islamic Prophet Muhammad died of a fever. However, the religion he left behind would transform the Middle East. In 633, the armies of Islam marched out of Arabia with a goal to spread the word of the prophet, with force if needed. In 634, the Arabs defeated a Byzantine force sent into Syria and captured Damascus. The arrival of another large Byzantine army outside Antioch (some 80,000 troops) forced the Arabs to retreat. The Byzantines advanced in May 636. However, a sandstorm blew in against the Byzantines on August 20, 636, and when the Arabs charged against them, they were utterly annihilated.

Jerusalem surrendered to the Arabs in 637, following a stout resistance; in 638, the Caliph Omar rode into the city. Heraclius stopped by Jerusalem to recover the True Cross whilst it was under siege. The Arab invasions are seen by some historians as the start of the decline of the Byzantine Empire. Only parts of Syria and Cilicia would be recovered.

Religious Controversy

The recovery of the eastern areas of the Roman Empire from the Persians during the early phase of Heraclius’ rule raised the problem of religious unity centering on the understanding of the true nature of Christ. Most of the inhabitants of these provinces were Monophysites who rejected the Council of Chalcedon of 451. The Chalcedonian Definition of Christ as being of two natures, divine and temporal, maintains that these two states remain distinct within the person of Christ and yet come together within his one true substance. This position was opposed by the Monophysites, who held that Christ possessed one nature only; the human and divine natures of Christ were fused into one new single (mono) nature. This internal division was dangerous for the Byzantine Empire, which was under constant threat from external enemies, many of whom were in favor of Monophysitism, people on the periphery of the Empire who also considered the religious hierarchy at Constantinople to be heretical and only interested in crushing their faith.

Heraclius tried to unite all of the various factions within the empire with a new formula that was more inclusive and more elastic. With the successful conclusion to the Persian War, Heraclius would devote more time to promoting his compromise.

The patriarch Sergius came up with a formula, which Heraclius released as the Ecthesis in 638. It forbade all mention of Christ possessing one or two energies, that is, one or two wills; instead, it now proclaimed that Christ, while possessing two natures, had but a single will. This approach seemed to be an acceptable compromise, and it secured widespread support throughout the east. The two remaining patriarchs in the east also gave their approval to the doctrine, now referred to as Monothelitism, and so it looked as if Heraclius would finally heal the divisions in the imperial church.

Unfortunately, he had not counted on the popes at Rome. During that same year of 638, Pope Honorius I had died. His successor, Pope Severinus (640), condemned the Ecthesis outright, and so was forbidden his seat until 640. His successor, Pope John IV (640-42), also rejected the doctrine completely, leading to a major schism between the eastern and western halves of the Chalcedonian Church. When news reached Heraclius of the pope’s condemnation, he was already old and ill, and the news only hastened his death, declaring with his dying breath that the controversy was all due to Sergius, and that the patriarch had pressured him to give his unwilling approval to the Ecthesis.

9.2.2: The Theme System

The Byzantine-Arab wars wrought havoc on the Byzantine Dynasty, but led to the creation of the highly efficient military theme system.

Learning Objective

Diagram the Byzantine military and social structure under Heraclius

Key Points

- In the Byzantine-Arab wars of the Heraclian Dynasty, the Arabs nearly destroyed the Byzantine Empire altogether.

- In order to fight back, the Byzantines created a new military system, known as the theme system, in which land was granted to farmers who, in return, would provide the empire with loyal soldiers. The efficiency of this system allowed the dynasty to keep hold of Asia Minor.

- The Arabs were finally repulsed through the use of Greek fire, but Constantinople had decreased massively in size, due to relocation.

- The empire was now poorer and society was dominated by the military, as a result of the many Arab invasions.

Key Terms

- theme system

-

A new military system created during the Heraclian Dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, in which land was granted to farmers who, in return, would provide the empire with loyal soldiers. Similar to the feudal system of medieval western Europe.

- Greek fire

-

A military weapon invented during the Byzantine Heraclian Dynasty; flaming projectiles that could burn while floating on water, and thus could be used for naval warfare.

- cosmopolitan

-

A city/place or person that embraces multicultural demographics.

- Caliphate

-

Islamic state led by a supreme religious and political leader, known as a caliph (i.e., “successor”) to Muhammad and the other prophets of Islam.

The themes (themata in Greek) were the main administrative divisions of the middle Byzantine Empire. They were established in the mid-7th century in the aftermath of the Slavic invasion of the Balkans, and Muslim conquests of parts of Byzantine territory. The themes replaced the earlier provincial system established by Diocletian and Constantine the Great. In their origin, the first themes were created from the areas of encampment of the field armies of the East Roman army, and their names corresponded to the military units that had existed in those areas. The theme system reached its apogee in the 9th and 10th centuries, as older themes were split up and the conquest of territory resulted in the creation of new ones. The original theme system underwent significant changes in the 11th and 12th centuries, but the term remained in use as a provincial and financial circumscription, until the very end of the empire.

Background

During the late 6th and early 7th centuries, the Eastern Roman Empire was under frequent attack from all sides. The successors of Heraclius had to fight a desperate war against the Arabs in order to keep them from conquering the entire Byzantine Empire; these conflicts were known as the Byzantine-Arab wars. The Arab invasions were unlike any other threat the Byzantines ever faced. Fighting a zealous holy war for Islam, the Arabs defeated army after army of the Byzantines, and nearly destroyed the empire. Egypt fell to the Arabs in 642 CE, and Carthage as well in 647 CE, and the Eastern Mediterranean slightly later. From 674-678 CE the Arabs laid siege to Constantinople itself.

In order to survive and fight back, the Byzantines created a new military system, known as the theme system. Abandoning the professional army inherited from the Roman past, the Byzantines granted land to farmers who, in return, would provide the empire with loyal soldiers. This was similar to the feudal system in medieval western Europe, but it differed in one important way—in the Byzantine theme system, the state continued to own the land, and simply leased it in exchange for service, whereas in the feudal system ownership of the lands was given over entirely to vassals. This efficiency of the theme system allowed the dynasty to keep hold of the imperial heartland of Asia Minor.

Thus, by the turning of the 8th century, the themes had become the dominant feature of imperial administration. Their large size and power, however, made their generals prone to revolt, as had been evidenced in the turbulent period 695-715, and would again during the great revolt of Artabasdos in 741-742.

The Theme System

Map depicting the locations of the themes established during the Heraclian Dynasty of the Byzantine Empire.

Despite the prominence of the themes, it was some time before they became the basic unit of the imperial administrative system. Although they had become associated with specific regions by the early 8th century, it took until the end of the 8th century for the civil fiscal administration to begin being organized around them, instead of following the old provincial system. This process, resulting in unified control over both military and civil affairs of each theme by its strategos, was complete by the mid-9th century, and is the “classical” thematic model.

Structure of the Themes

The term theme was ambiguous, referring both to a form of military tenure and to an administrative division. A theme was an arrangement of plots of land given for farming to the soldiers. The soldiers were still technically a military unit, under the command of a strategos, and they did not own the land they worked, as it was still controlled by the state. Therefore, for its use the soldiers’ pay was reduced. By accepting this proposition, the participants agreed that their descendants would also serve in the military and work in a theme, thus simultaneously reducing the need for unpopular conscription, as well as cheaply maintaining the military. It also allowed for the settling of conquered lands, as there was always a substantial addition made to public lands during a conquest.

The commander of a theme, however, did not only command his soldiers. He united the civil and military jurisdictions in the territorial area in question. Thus the division set up by Diocletian between civil governors (praesides) and military commanders (duces) was abolished, and the empire returned to a system much more similar to that of the Republic or the Principate, where provincial governors had also commanded the armies in their area.

Consequences of the Theme System

Early on, Heraclius had proven himself to be an excellent Emperor—his reorganization of the empire into themes allowed the Byzantines to extract as much as they possibly could to increase their military potential. This became essential after 650, when the Islamic Caliphate was far more resourceful and powerful then the Byzantines were. As a result, a high level of efficiency was needed to combat the Arabs, achieved in part due to the theme system.

The Arabs were finally repulsed through the use of Greek fire, flaming projectiles that could burn while floating on water, and thus, could be used for naval warfare. Greek fire was a closely guarded state secret, a secret that has since been lost. The composition of Greek fire remains a matter of speculation and debate, with proposals including combinations of pine resin, naphtha, quicklime, sulfur, or niter. Byzantine use of incendiary mixtures was especially effective, thanks to the use of pressurized nozzles or siphōn to project the liquid onto the enemy. The Arab-Muslim navies eventually adapted to their use. Under constant threat of attack, Constantinople had dropped substantially in size, due to relocation, from 500,000 to 40,000-70,000.

Greek Fire

Image from an illuminated manuscript (the Skylitzes manuscript) showing the Byzantine Navy’s use of Greek fire against the fleet of the rebel Thomas the Slav, c. 12th century CE. The caption above the left ship reads “the fleet of the Romans setting ablaze the fleet of the enemies.”

By the end of the Heraclian Dynasty in 711 CE, the empire had transformed from the Eastern Roman Empire, with its urbanized, cosmopolitan civilization, to the medieval Byzantine Empire, an agrarian, military-dominated society in a lengthy struggle with the Muslims. The loss of the empire’s richest provinces, coupled with successive invasions, had reduced the imperial economy to a relatively impoverished state, compared to the resources available to the Caliphate. The monetary economy persisted, but the barter economy experienced a revival as well. However, this state was also far more homogeneous than the Eastern Roman Empire; the borders had shrunk, such that many of the Latin-speaking territories were lost and the dynasty was reduced to its mostly Greek-speaking territories. This enabled it to weather these storms and enter a period of stability under the next dynasty, the Isaurian Dynasty.

9.2.3: The Isaurian Dynasty

The Isaurian Dynasty is characterized by relative political stability, after an important defeat of the Arabs by Leo III, and Iconoclasm, which resulted in considerable internal turmoil.

Learning Objective

Describe governmental and religious changes that occured during the Isaurian Dynasty

Key Points

- The Isaurian Dynasty, founded by Leo III, was a time of relative stability, compared to the constant warfare against the Arabs that characterized the preceding Heraclian Dynasty.

- However, the Bulgars, a nomadic tribe, rose up in Europe and took some Byzantine lands.

- The Isaurian Dynasty is chiefly associated with Byzantine Iconoclasm, an attempt to restore divine favor by purifying the Christian faith from excessive adoration of icons, which resulted in considerable internal turmoil.

- The Second Arab siege of Constantinople in 717-718 was an unsuccessful offensive by the Muslim Arabs of the Umayyad Caliphate against the capital city of the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople.

- The outcome of the siege was of considerable macrohistorical importance; the Byzantine capital’s survival preserved the empire as a bulwark against Islamic expansion into Europe until the 15th century, when it fell to the Ottoman Turks.

- By the end of the Isaurian Dynasty in 802 CE, the Byzantines were continuing to fight the Arabs and the Bulgars, and the empire had been reduced from a Mediterranean-wide empire to only Thrace and Asia Minor.

Key Terms

- iconoclasm

-

The deliberate destruction within a culture of the culture’s own religious icons and other symbols or monuments, usually for religious or political motives. It is a frequent component of major political or religious changes.

- Bulgars

-

A nomadic tribe related to the Huns; they presented a threat to the Byzantine Empire.

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by the Isaurian or Syrian Dynasty from 717-802. The Isaurian emperors were successful in defending and consolidating the empire against the Caliphate after the onslaught of the early Muslim conquests, but were less successful in Europe, where they suffered setbacks against the Bulgars, had to give up the Exarchate of Ravenna, and lost influence over Italy and the Papacy to the growing power of the Franks.

The Isaurian Dynasty is chiefly associated with Byzantine Iconoclasm, an attempt to restore divine favor by purifying the Christian faith from excessive adoration of icons, which resulted in considerable internal turmoil.

By the end of the Isaurian Dynasty in 802, the Byzantines were continuing to fight the Arabs and the Bulgars for their very existence, with matters made more complicated when Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Imperator Romanorum (“Emperor of the Romans”), which was seen as making the Carolingian Empire the successor to the Roman Empire, or at least the western half.

Leo III, who would become the founder of the so-called Isaurian Dynasty, was actually born in Germanikeia in northern Syria c. 685; his alleged origin from Isauria derives from a reference in Theophanes the Confessor, which may be a later addition. After being raised to spatharios by Justinian II, he fought the Arabs in Abasgia, and was appointed as strategos of the Anatolics by Anastasios II. Following the latter’s fall in 716, Leo allied himself with Artabasdos, the general of the Armeniacs, and was proclaimed emperor while two Arab armies campaigned in Asia Minor. Leo averted an attack by Maslamah through clever negotiations, in which he promised to recognize the Caliph’s suzerainty. However, on March 25, 717, he entered Constantinople and deposed Theodosios.

Leo III’s Rule

Having preserved the empire from extinction by the Arabs, Leo proceeded to consolidate its administration, which in the previous years of anarchy had become completely disorganized. In 718, he suppressed a rebellion in Sicily and in 719 did the same on behalf of the deposed Emperor Anastasios II.

Leo secured the empire’s frontiers by inviting Slavic settlers into the depopulated districts, and by restoring the army to efficiency; when the Umayyad Caliphate renewed their invasions in 726 and 739, as part of the campaigns of Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik, the Arab forces were decisively beaten, particularly at Akroinon in 740. His military efforts were supplemented by his alliances with the Khazars and the Georgians.

Leo undertook a set of civil reforms, including the abolition of the system of prepaying taxes, which had weighed heavily upon the wealthier proprietors; the elevation of the serfs into a class of free tenants; and the remodeling of family, maritime law, and criminal law, notably substituting mutilation for the death penalty in many cases. The new measures, which were embodied in a new code called the Ecloga (Selection), published in 726, met with some opposition on the part of the nobles and higher clergy. The emperor also undertook some reorganization of the theme structure by creating new themata in the Aegean region.

Byzantine Coin

A gold coin, or solidus, engraved with the emperors of the Byzantine Isaurian Dynasty, from c. 780 CE. Left: Leo IV with his son Constantine VI; Right: Leo III with his son Constantine V on the reverse.

The Siege of Constantinople

The Second Arab siege of Constantinople in 717-718 was a combined land and sea offensive by the Muslim Arabs of the Umayyad Caliphate against the capital city of the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople. The campaign marked the culmination of twenty years of attacks and progressive Arab occupation of the Byzantine borderlands, while Byzantine strength was sapped by prolonged internal turmoil. In 716, after years of preparations, the Arabs, led by Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik, invaded Byzantine Asia Minor. The Arabs initially hoped to exploit Byzantine civil strife, and made common cause with the general Leo III the Isaurian, who had risen up against Emperor Theodosius III. Leo, however, tricked them and secured the Byzantine throne for himself.

After wintering in the western coastlands of Asia Minor, the Arab army crossed into Thrace in early summer 717 and built siege lines to blockade the city, which was protected by the massive Theodosian Walls. The Arab fleet, which accompanied the land army and was meant to complete the city’s blockade by sea, was neutralized soon after its arrival by the Byzantine navy through the use of Greek fire. This allowed Constantinople to be resupplied by sea, while the Arab army was crippled by famine and disease during the unusually hard winter that followed. In spring 718, two Arab fleets sent as reinforcements were destroyed by the Byzantines after their Christian crews defected, and an additional army sent overland through Asia Minor was ambushed and defeated. Coupled with attacks by the Bulgars on their rear, the Arabs were forced to lift the siege on August 15, 718. On its return journey, the Arab fleet was almost completely destroyed by natural disasters and Byzantine attacks.

The Arab failure was chiefly logistical, as they were operating too far from their Syrian bases, but the superiority of the Byzantine navy through the use of Greek fire, the strength of Constantinople’s fortifications, and the skill of Leo III in deception and negotiations, also played important roles.

The siege’s failure had wide-ranging repercussions. The rescue of Constantinople ensured the continued survival of Byzantium, while the Caliphate’s strategic outlook was altered: although regular attacks on Byzantine territories continued, the goal of outright conquest was abandoned. Historians consider the siege to be one of history’s most important battles, as its failure postponed the Muslim advance into Southeastern Europe for centuries. The Byzantine capital’s survival preserved the empire as a bulwark against Islamic expansion into Europe until the 15th century, when it fell to the Ottoman Turks. Along with the Battle of Tours in 732, the successful defense of Constantinople has been seen as instrumental in stopping Muslim expansion into Europe.

9.2.4: Iconoclasm in Byzantium

The Byzantine Iconoclasm was the banning of the worship of religious images, a movement that sparked internal turmoil.

Learning Objective

Understand the reasoning and events that led to iconoclasm

Key Points

- Isaurian Emperor Leo III interpreted his many military failures as a judgment on the empire by God, and decided that it was being judged for the worship of religious images. He banned religious images in about 730 CE, the beginning of the Byzantine Iconoclasm.

- At the Council of Hieria in 754 CE, the Church endorsed an iconoclast position and declared image worship to be blasphemy.

- At the Second Council of Nicaea in 787 CE, the decrees of the previous iconoclast council were reversed and image worship was restored, marking the end of the First Iconoclasm.

- Emperor Leo V instituted a second period of iconoclasm in 814 CE, again possibly motivated by military failures seen as indicators of divine displeasure, but only a few decades later, in 842 CE, icon worship was again reinstated.

Key Terms

- iconoclasm

-

The deliberate destruction within a culture of the culture’s own religious icons and other symbols or monuments.

- Council of Hieria

-

The first church council concerned with religious imagery. On behalf of the church, the council endorsed an iconoclast position and declared image worship to be blasphemy.

- Second Council of Nicaea

-

This council reversed the decrees of the Council of Hieria and restored image worship, marking the end of the First Byzantine Iconoclasm.

Iconoclasm, Greek for “image-breaking,” is the deliberate destruction within a culture of the culture’s own religious icons and other symbols or monuments. Iconoclasm is generally motivated by an interpretation of the Ten Commandments that declares the making and worshipping of images, or icons, of holy figures (such as Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, and saints) to be idolatry and therefore blasphemy.

Most surviving sources concerning the Byzantine Iconoclasm were written by the victors, or the iconodules (people who worship religious images), so it is difficult to obtain an accurate account of events. However, the Byzantine Iconoclasm refers to two periods in the history of the Byzantine Empire when the use of religious images or icons was opposed by religious and imperial authorities. The “First Iconoclasm,” as it is sometimes called, lasted between about 730 CE and 787 CE, during the Isaurian Dynasty. The “Second Iconoclasm” was between 814 CE and 842 CE. The movement was triggered by changes in Orthodox worship that were themselves generated by the major social and political upheavals of the seventh century for the Byzantine Empire.

Byzantine Iconoclasm

A depiction of the destruction of a religious image under the Byzantine Iconoclasm, by Chludov Psalter, 9th century CE.

Causes

Traditional explanations for Byzantine Iconoclasm have sometimes focused on the importance of Islamic prohibitions against images influencing Byzantine thought. According to Arnold J. Toynbee, for example, it was the prestige of Islamic military successes in the 7th and 8th centuries that motivated Byzantine Christians to adopt the Islamic position of rejecting and destroying idolatrous images. The role of women and monks in supporting the veneration of images has also been asserted. Social and class-based arguments have been put forward, such as the assertion that iconoclasm created political and economic divisions in Byzantine society, and that it was generally supported by the eastern, poorer, non-Greek peoples of the empire who had to constantly deal with Arab raids. On the other hand, the wealthier Greeks of Constantinople, and also the peoples of the Balkan and Italian provinces, strongly opposed iconoclasm. In recent decades in Greece, iconoclasm has become a favorite topic of progressive and Marxist historians and social scientists, who consider it a form of medieval class struggle and have drawn inspiration from it. Re-evaluation of the written and material evidence relating to the period of Byzantine Iconoclasm by scholars, including John Haldon and Leslie Brubaker, has challenged many of the basic assumptions and factual assertions of the traditional account.

The First Iconoclasm: Leo III

The seventh century had been a period of major crisis for the Byzantine Empire, and believers had begun to lean more heavily on divine support. The use of images of the holy increased in Orthodox worship, and these images increasingly came to be regarded as points of access to the divine. Leo III interpreted his many military failures as a judgment on the empire by God, and decided that they were being judged for their worship of religious images.

Emperor Leo III, the founder of the Isaurian Dynasty, and the iconoclasts of the eastern church, banned religious images in about 730 CE, claiming that worshiping them was heresy; this ban continued under his successors. He accompanied the ban with widespread destruction of religious images and persecution of the people who worshipped them.

The western church remained firmly in support of the use of images throughout the period, and the whole episode widened the growing divergence between the eastern and western traditions in what was still a unified church, as well as facilitating the reduction or removal of Byzantine political control over parts of Italy.

Leo died in 741 CE, and his son and heir, Constantine V, furthered his views until the end of his own rule in 775 CE. In 754 CE, Constantine summoned the first ecumenical council concerned with religious imagery, the Council of Hieria; 340 bishops attended. On behalf of the church, the council endorsed an iconoclast position and declared image worship to be blasphemy. John of Damascus, a Syrian monk living outside Byzantine territory, became a major opponent of iconoclasm through his theological writings.

The Brief Return of Icon Worship

After the death of Constantine’s son, Leo IV (who ruled from 775 CE-780 CE), his wife, Irene, took power as regent for her son, Constantine VI (who ruled from 780 CE-97 CE). After Leo IV too died, Irene called another ecumenical council, the Second Council of Nicaea, in 787 CE, that reversed the decrees of the previous iconoclast council and restored image worship, marking the end of the First Iconoclasm. This may have been an attempt to soothe the strained relations between Constantinople and Rome.

The Second Iconoclasm (814 CE-842 CE)

Emperor Leo V the Armenian instituted a second period of Iconoclasm in 814 CE, again possibly motivated by military failures seen as indicators of divine displeasure. The Byzantines had suffered a series of humiliating defeats at the hands of the Bulgarian Khan Krum. It was made official in 815 CE at a meeting of the clergy in the Hagia Sophia. But only a few decades later, in 842 CE, the regent Theodora again reinstated icon worship.

9.2.5: The Emperor Irene

Irene of Athens, the first woman emperor of the Byzantine Empire, fought for recognition as imperial leader throughout her rule, and is best known for ending the First Iconoclasm in the Eastern Church.

Learning Objective

Analyze the significance of Emperor Irene

Key Points

- Irene of Athens was an orphan from a noble family, and was married to the son of the current emperor, Leo IV, in 768.

- When Leo died in 780, Irene became regent for their nine-year-old son, Constantine, who was too young to rule as emperor, thereby giving her administrative control over the empire.

- As imperial regent, Irene subdued rebellions and fought the Arabs with mixed success. She also ended the First Iconoclasm in the Eastern Church.

- When Constantine became old enough to become emperor proper, he eventually rebelled against Irene, although he let her keep the title of empress.

- Soon after, Irene organized her own rebellion and eventually killed her son, thereby claiming sole rulership over the empire as empress, the first woman to have that title in the empire.

- Although it is often asserted that, as monarch, Irene called herself “emperor” rather than “empress,” in fact she used “empress” in most of her documents, coins, and seals.

- The pope would not recognize a woman as ruler, and in 800, crowned Charlemagne as imperial ruler over the entire Roman territory, including Byzantium.

- Charlemagne did not attempt to rule Byzantium, but relations between the two empires remained difficult.

- Irene was eventually deposed by her finance minister.

Key Terms

- regent

-

A person appointed to administer a state because the monarch is a minor, is absent, or is incapacitated.

- strategos

-

A military governor in the Byzantine Empire.

- Iconoclasm

-

The destruction of religious icons, and other images or monuments, for religious or political motives.

Irene of Athens (c. 752-803 CE) was Byzantine empress from 797 to 802. Before that, Irene was empress consort from 775 to 780, and empress dowager and regent from 780 to 797. She is best known for ending iconoclasm.

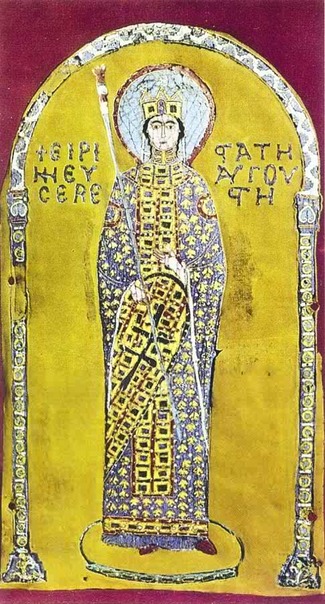

Empress Irene

Image from “Pala d’Oro,” Venice, c. 10th century.

Early Life

Irene was related to the noble Greek Sarantapechos family of Athens. Although she was an orphan, her uncle or cousin, Constantine Sarantapechos, was a patrician and was possibly the strategos of the theme of Hellas at the end of the 8th century. She was brought to Constantinople by Emperor Constantine V on November 1, 768, and was married to his son, Leo IV, on December 17.

On 14 January 771, Irene gave birth to a son, the future Constantine VI. When Constantine V died in September 775, Leo succeeded to the throne at the age of twenty-five years. Leo, though an iconoclast, pursued a policy of moderation towards iconodules, but his policies became much harsher in August 780, when a number of courtiers were punished for venerating icons. According to tradition, he discovered icons concealed among Irene’s possessions and refused to share the marriage bed with her thereafter. Nevertheless, when Leo died on September 8, 780, Irene became regent for their nine-year-old son, Constantine, thereby giving her administrative control over the empire.

Regency

Irene was almost immediately confronted with a conspiracy that tried to raise Caesar Nikephoros, a half-brother of Leo IV, to the throne. To overcome this challenge, she had Nikephoros and his co-conspirators ordained as priests, a status which disqualified them from ruling.

As early as 781, Irene began to seek a closer relationship with the Carolingian Dynasty and the Papacy in Rome. She negotiated a marriage between her son, Constantine, and Rotrude, a daughter of Charlemagne by his third wife, Hildegard. During this time, Charlemagne was at war with the Saxons, and would later become the new king of the Franks. Irene went as far as to send an official to instruct the Frankish princess in Greek; however, Irene herself broke off the engagement in 787, against her son’s wishes.

Irene next had to subdue a rebellion led by Elpidius, the strategos of Sicily. Irene sent a fleet, which succeeded in defeating the Sicilians. Elpidius fled to Africa, where he defected to the Abbasid Caliphate. After the success of Constantine V’s general, Michael Lachanodrakon, who foiled an Abbasid attack on the eastern frontiers, a huge Abbasid army under Harun al-Rashid invaded Anatolia in summer 782. The strategos of the Bucellarian Theme, Tatzates, defected to the Abbasids, and Irene, in exchange for a three-year truce, had to agree to pay an annual tribute of 70,000 or 90,000 dinars to the Abbasids, give them 10,000 silk garments, and provide them with guides, provisions, and access to markets during their withdrawal.

Ending Iconoclasm

Irene’s most notable act was the restoration of the veneration of icons, thereby ending the First Iconoclasm of the Eastern Church. Having chosen Tarasios, one of her partisans and her former secretary, as Patriarch of Constantinople in 784, she summoned two church councils. The first of these, held in 786 at Constantinople, was frustrated by the opposition of the iconoclast soldiers. The second, convened at Nicaea in 787, formally revived the veneration of icons and reunited the Eastern Church with that of Rome.

While this greatly improved relations with the Papacy, it did not prevent the outbreak of a war with the Franks, who took over Istria and Benevento in 788. In spite of these reverses, Irene’s military efforts met with some success: in 782 her favored courtier, Staurakios, subdued the Slavs of the Balkans and laid the foundations of Byzantine expansion and re-Hellenization in the area. Nevertheless, Irene was constantly harried by the Abbasids, and in 782 and 798, had to accept the terms of the respective Caliphs Al-Mahdi and Harun al-Rashid.

Rule as Empress

As Constantine approached maturity, he began to grow restless under her autocratic sway. An attempt to free himself by force was met and crushed by the empress, who demanded that the oath of fidelity should thenceforward be taken in her name alone. The discontent that this occasioned swelled in 790 into open resistance, and the soldiers, headed by the army of the Armeniacs, formally proclaimed Constantine VI as the sole ruler.

A hollow semblance of friendship was maintained between Constantine and Irene, whose title of empress was confirmed in 792; however, the rival factions remained, and in 797, Irene, by cunning intrigues with the bishops and courtiers, organized a conspiracy on her own behalf. Constantine could only flee for aid to the provinces, but even there participants in the plot surrounded him. Seized by his attendants on the Asiatic shore of the Bosphorus, Constantine was carried back to the palace at Constantinople. His eyes were gouged out, and according to most contemporary accounts, he died from his wounds a few days later, leaving Irene to be crowned as first empress regnant of Constantinople.

As empress, Irene made determined efforts to stamp out iconoclasm everywhere in the empire, including within the ranks of the army. During Irene’s reign, the Arabs were continuing to raid into and despoil the small farms of the Anatolian section of the empire. These small farmers of Anatolia owed a military obligation to the Byzantine throne. Indeed, the Byzantine army and the defense of the empire was largely based on this obligation and the Anatolian farmers. The iconodule (icon worship) policy drove these farmers out of the army, and thus off their farms. Thus, the army was weakened and was unable to protect Anatolia from the Arab raids. Many of the remaining farmers of Anatolia were driven from the farm to settle in the city of Byzantium, further reducing the army’s ability to raise soldiers. Additionally, the abandoned farms fell from the tax rolls and reduced the amount of income that the government received. These farms were taken over by the largest land owner in the Byzantine Empire, the monasteries. To make the situation even worse, Irene had exempted all monasteries from all taxation.

Given the financial ruin into which the empire was headed, it was no wonder, then, that Irene was, eventually, deposed by her own minister of finance. The leader of this successful revolt against Irene replaced her on the Byzantine throne under the name Nicephorus I.

Although it is often asserted that, as monarch, Irene called herself “basileus” (emperor), rather than “basilissa” (empress), in fact there are only three instances where it is known that she used the title “basileus“: two legal documents in which she signed herself as “Emperor of the Romans,” and a gold coin of hers found in Sicily bearing the title of “basileus.” She used the title “basilissa” in all other documents, coins, and seals.

Relationship with the Carolingian Empire

Irene’s unprecedented position as an empress ruling in her own right was emphasized by the coincidental rise of the Carolingian Empire in western Europe, which rivaled Irene’s Byzantium in size and power. In 800, Charlemagne was crowned emperor by Pope Leo III, on Christmas Day. The clergy and nobles attending the ceremony proclaimed Charlemagne as “Emperor of the Roman Empire.” In support of Charlemagne’s coronation, some argued that the imperial position was actually vacant, deeming a woman unfit to be emperor. However, Charlemagne made no claim to the Byzantine Empire. Relations between the two empires remained difficult.

9.3: The Late Byzantine Empire

9.3.1: The Macedonian Dynasty

The Macedonian Dynasty saw expansion and the Byzantine Renaissance, but also instability, due to competition among nobles in the theme system.

Learning Objective

Discuss hegemony under the Macedonian Dynasty

Key Points

- Shortly after the extended controversy over the Byzantine Iconoclasm, the Byzantine Empire would recover under the Macedonian Dynasty, starting in 867 CE.

- The Macedonian Dynasty saw the Byzantine Renaissance, a time of increased interest in classical scholarship and the assimilation of classical motifs into Christian artwork.

- The empire also expanded during this period, conquering Crete, Cyprus, and most of Syria.

- However, the Macedonian Dynasty also saw increasing dissatisfaction and competition for land among nobles in the theme system, which weakened the authority of the emperors and led to instability.

Key Term

- Byzantine Renaissance

-

The time during the Macedonian Dynasty when art, literature, science, and philosophy flourished.

Emperor Basil I

Shortly after the extended controversy over iconoclasm, which more or less ended (at least in the east) with the regent Theodora reinstating icon worship in 842 CE, Emperor Basil I founded a new dynasty, the Macedonian Dynasty, in 867 CE. Basil was born a simple peasant in the Byzantine theme of Macedonia; he rose in the Imperial Court, and usurped the imperial throne from Emperor Michael III (r. 842-867). Despite his humble origins, he showed great ability in running the affairs of state, leading to a revival of imperial power and a renaissance of Byzantine art. He was perceived by the Byzantines as one of their greatest emperors, and the Macedonian Dynasty ruled over what is regarded as the most glorious and prosperous era of the Byzantine Empire.

It was under this dynasty that the Byzantine Empire would recover from its previous turmoil, and become the most powerful state in the medieval world. This was also a period of cultural and artistic flowering in the Byzantine world. The cities of the empire expanded, and affluence spread across the provinces because of the new-found security. The population rose, and production increased, stimulating new demand, while also helping to encourage trade. The iconoclast movement experienced a steep decline; the decline was advantageous to the emperors who had softly suppressed iconoclasm, and to the reconciliation of the religious strife that had drained the imperial resources in the previous centuries.

Emperor Basil I

A depiction of Byzantine Emperor Basil I, of the Macedonian Dynasty, on horseback.

Macedonian Renaissance

The time of the Macedonian Dynasty’s rule over the Byzantine Empire is sometimes called the Byzantine Renaissance or the Macedonian Renaissance. A long period of military struggle for survival had recently dominated the life of the Byzantine Empire, but the Macedonians ushered in an age when art and literature once again flourished. The classical Greco-Roman heritage of Byzantium was central to the writers and artists of the period. Byzantine scholars, most notably Leo the Mathematician, read the scientific and philosophical works of the ancient Greeks and expanded upon them. Artists adopted their naturalistic style and complex techniques from ancient Greek and Roman art, and mixed them with Christian themes. Byzantine painting from this period would have a strong influence on the later painters of the Italian Renaissance.

Political and Religious Expansion

The Macedonian Dynasty also oversaw the expansion of the Byzantine Empire, which went on the offensive against its enemies. For example, Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas (who ruled from 912 CE-969 CE) pursued an aggressive policy of expansion. Before rising to the throne, he had conquered Crete from the Muslims, and as emperor he led the conquest of Cyprus and most of Syria.

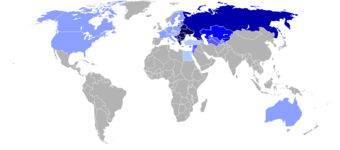

The Macedonian period also included events of momentous religious significance. The conversion of the Bulgarians, Serbs, and Rus’ to Orthodox Christianity permanently changed the religious map of Europe, and still impacts demographics today. Cyril and Methodius, two Byzantine Greek brothers, contributed significantly to the Christianization of the Slavs, and in the process devised the Glagolitic alphabet, ancestor to the Cyrillic script.