8.1: The Etruscans

8.1.1: The Origins of Etruria

The Etruscans were a Mediterranean civilization during the 6th to 3rd century BCE, from whom the Romans derived a great deal of cultural influence.

Learning Objective

Explain the relationship between the Etruscan and Roman civilizations

Key Points

- The prevailing view is that Rome was founded by Italics who later merged with Etruscans. Rome was likely a small settlement until the arrival of the Etruscans, who then established Rome’s urban infrastructure.

- The Etruscans were indigenous to the Mediterranean area, probably stemming from the Villanovan culture.

- The mining and commerce of metal, especially copper and iron, led to an enrichment of the Etruscans, and to the expansion of their influence in the Italian Peninsula and the western Mediterranean Sea. Conflicts with the Greeks led the Etruscans to ally themselves with the Carthaginians.

- The Etruscans governed within a state system, with only remnants of the chiefdom or tribal forms. The Etruscan state government was essentially a theocracy.

- Aristocratic

families were important within Etruscan society, and women enjoyed, comparatively, many freedoms within society. - The

Etruscan system of belief was an immanent polytheism that incorporated

indigenous, Indo-European, and Greek influences. - It is believed that the

Etruscans spoke a non-Indo-European language, probably related to what is

called the Tyrsenian language family, which is itself an isolate family, or in

other words, unrelated directly to other known language groups.

Key Terms

- Etruscan

-

The modern name given to a civilization of ancient Italy in the area corresponding roughly to Tuscany, western Umbria, and northern Latium.

- theocracy

-

A form of government in which a deity is officially recognized as the civil ruler, and official policy is governed by officials regarded as divinely guided, or is pursuant to the doctrine of a particular religion or religious group.

- oligarchic

-

A form of power structure in which power effectively rests with a small number of people. These people could be distinguished by royalty, wealth, family ties, education, corporate, or military control. Such states are often controlled by a few prominent families who typically pass their influence from one generation to the next; however, inheritance is not a necessary condition for the application of this term.

Those who subscribe to an Italic (a diverse group of people who inhabited pre-Roman Italy) foundation of Rome, followed by an Etruscan invasion, typically speak of an Etruscan “influence” on Roman culture; that is, cultural objects that were adopted by Rome from neighboring Etruria. The prevailing view is that Rome was founded by Italics who later merged with Etruscans. In that case, Etruscan cultural objects are not a heritage but are, instead, influences. Rome was likely a small settlement until the arrival of the Etruscans, who then established its initial urban infrastructure.

Origins

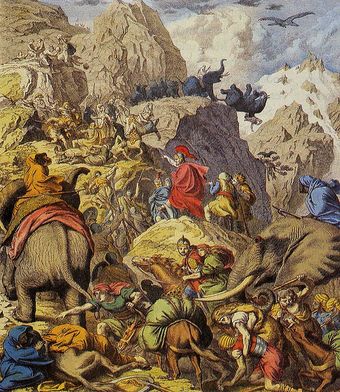

The origins of the Etruscans are mostly lost in prehistory. Historians have no literature, and no original texts of religion or philosophy. Therefore, much of what is known about this civilization is derived from grave goods and tomb findings. The main hypotheses state that the Etruscans were indigenous to the region, probably stemming from the Villanovan culture or from the Near East. Etruscan expansion was focused both to the north, beyond the Apennines, and into Campania. The mining and commerce of metal, especially copper and iron, led to an enrichment of the Etruscans, and to the expansion of their influence in the Italian Peninsula and the western Mediterranean Sea. Here, their interests collided with those of the Greeks, especially in the 6th century BCE, when Phoceans of Italy founded colonies along the coast of Sardinia, Spain, and Corsica. This led the Etruscans to ally themselves with the Carthaginians, whose interests also collided with the Greeks.

Map of the Etruscan Civilization

Extent of Etruscan civilization and the 12 Etruscan League cities.

Around 540 BCE, the Battle of Alalia led to a new distribution of power in the western Mediterranean Sea. Though the battle had no clear winner, Carthage managed to expand its sphere of influence at the expense of the Greeks, and Etruria saw itself relegated to the northern Tyrrhenian Sea with full ownership of Corsica. From the first half of the 5th century BCE, the new international political situation signaled the beginning of Etruscan decline after they had lost their southern provinces. In 480 BCE, Etruria’s ally, Carthage, was defeated by a coalition of Magna Graecia cities led by Syracuse. A few years later, in 474 BCE, Syracuse’s tyrant, Hiero, defeated the Etruscans at the Battle of Cumae. Etruria’s influence over the cities of Latium and Campania weakened, and it was taken over by the Romans and Samnites. In the 4th century, Etruria saw a Gallic invasion end its influence over the Po valley and the Adriatic coast. Meanwhile, Rome had started annexing Etruscan cities. These events led to the loss of the Northern Etruscan provinces. Etruria was conquered by Rome in the 3rd century BCE.

Etruscan Government

The Etruscans governed using a state system of society, with only remnants of the chiefdom and tribal forms. In this way, they were different from the surrounding Italics. Rome was, in a sense, the first Italic state, but it began as an Etruscan one. It is believed that the Etruscan government style changed from total monarchy to an oligarchic republic (as the Roman Republic did) in the 6th century BCE, although it is important to note this did not happen to all city-states.

The Etruscan state government was essentially a theocracy. The government was viewed as being a central authority over all tribal and clan organizations. It retained the power of life and death; in fact, the gorgon, an ancient symbol of that power, appears as a motif in Etruscan decoration. The adherents to this state power were united by a common religion. Political unity in Etruscan society was the city-state, and Etruscan texts name quite a number of magistrates without explanation of their function (the camthi, the parnich, the purth, the tamera, the macstrev, etc.).

Etruscan Families

According to

inscriptional evidence from tombs, aristocratic families were important within

Etruscan society. Most likely, aristocratic families rose to prominence over

time through the accumulation of wealth via trade, with many of the wealthiest

Etruscan cities located near the coast.

The Etruscan name for

family was lautn, and at the center

of the lautn was the married couple.

Etruscans were monogamous, and the lids of large numbers of sarcophagi were

decorated with images of smiling couples in the prime of their life, often

reclining next to each other or in an embrace. Many tombs also included

funerary inscriptions naming the parents of the deceased, indicating the

importance of the mother’s side of the family in Etruscan society. Additionally,

Etruscan women were allowed considerable freedoms in comparison to Greek and

Roman women, and mixed-sex socialization outside the domestic realm occurred.

Etruscan Religion

The Etruscan system of belief was an immanent polytheism; that is, all visible phenomena were considered to be a manifestation of divine power, and that power was subdivided into deities that acted continually on the world of man and could be dissuaded or persuaded in favor of human affairs. Three layers of deities are evident in the extensive Etruscan art motifs. One appears to be divinities of an indigenous nature: Catha and Usil, the sun; Tivr, the moon; Selvans, a civil god; Turan, the goddess of love; Laran, the god of war; Leinth, the goddess of death; Maris; Thalna; Turms; and the ever-popular Fufluns, whose name is related in an unknown way to the city of Populonia and the populus Romanus, the Roman people.

Ruling over this pantheon of lesser deities were higher ones that seem to reflect the Indo-European system: Tin or Tinia, the sky; Uni, his wife (Juno); and Cel, the earth goddess. In addition the Greek gods were taken into the Etruscan system: Aritimi (Artemis), Menrva (Minerva), and Pacha (Bacchus). The Greek heroes taken from Homer also appear extensively in art motifs.

The Greek polytheistic approach was similar to the Etruscan religious and cultural base. As the Romans emerged from the legacy created by both of these groups, it shared in a belief system of many gods and deities.

Etruscan Language and

Etymology

Knowledge of the Etruscan

language is still far from complete. It is believed that the Etruscans spoke a

non-Indo-European language, probably related to what is called the Tyrsenian

language family, which is itself an isolate family, or in other words,

unrelated directly to other known language groups. No etymology exists for Rasna, the Etruscans’ name for

themselves, though Italian historic linguist, Massimo Pittau, has proposed that

it meant “shaved” or “beardless.” The hypothesized etymology for Tusci, a root for “Tuscan” or “Etruscan,” suggests a connection to the Latin and Greek words for “tower,” illustrating

the Tusci people as those who built

towers. This was possibly based upon the Etruscan preference for building hill towns on

high precipices that were enhanced by walls. The word may also be related to the city of

Troy, which was also a city of towers, suggesting large numbers of migrants

from that region into Etruria.

8.1.2: Etruscan Artifacts

Historians have no literature, or original

Etruscan religious or philosophical texts, on which to base knowledge of their

civilization. So much of what is known is derived from grave goods and tomb

findings.

Learning Objective

Explain the importance of Etruscan artifacts to

our understanding of their history

Key Points

- Princely tombs

did not house individuals, but families who were interred over long periods. - Although many

Etruscan cities were later assimilated by Italic, Celtlic, or Roman ethnic

groups, the Etruscan names and inscriptions that survive within the ruins

provide historic evidence as to the range of settlements that the Etruscans

constructed. -

It is unclear

whether Etruscan cultural objects are influences upon Roman culture or part of

native Roman heritage. The criterion for deciding whether or not an object

originated in Rome or descended to the Romans from the Etruscans is the date of

the object and the opinion of ancient sources regarding the provenance of the object’s

style. - Although Diodorus of Sicily wrote, in the 1st century, of the great

achievements of the Etruscans, little survives or is known of it.

Key Terms

- oligarchic

-

A form of power structure in which power

effectively rests with a small number of people. These people could be

distinguished by royalty, wealth, family ties, education, corporate, or

military control. Such states are often controlled by a few prominent families

who typically pass their influence from one generation to the next, but

inheritance is not a necessary condition for the application of this term. - sarcophagi

-

A box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most

commonly carved in stone and displayed above ground.

Historians have no

literature or original Etruscan religious or philosophical texts on which to

base knowledge of their civilization, so much of what is known is derived from

grave goods and tomb findings. Princely tombs did not house individuals, but

families who were interred over long periods. The decorations and objects

included at these sites paint a picture of Etruscan social and political life. For

instance, wealth from trade seems to have supported the rise of aristocratic

families who, in turn, were likely foundational to the Etruscan oligarchic system

of governance. Indeed, at some Etruscan tombs, physical evidence of trade has

been found in the form of grave goods, including fine faience ware cups, which

was likely the result of trade with Egypt. Additionally, the depiction of

married couples on many sarcophagi provide insight into the respect and

freedoms granted to women within Etruscan society, as well as the emphasis

placed on romantic love as a basis for marriage pairings.

Sarcophagus of the Spouses

Sarcophagus of an Etruscan couple in the Louvre, Room 18.

Although many Etruscan

cities were later assimilated by Italic, Celtic, or Roman ethnic groups, the Etruscan

names and inscriptions that survive within the ruins provide historic evidence of the range of settlements constructed by the Etruscans. Etruscan cities flourished

over most of Italy during the Roman Iron Age. According to ancient sources,

some cities were founded by the Etruscans in prehistoric times, and bore

entirely Etruscan names. Others were later colonized by the Etruscans from

Italic groups.

Nonetheless, relatively little is known about the architecture of the

ancient Etruscans. What is known is that they adapted the native Italic styles

with influence from the external appearance of Greek architecture. Etruscan

architecture is not generally considered part of the body of Greco-Roman

classical architecture. Though the houses of the wealthy were evidently very

large and comfortable, the burial chambers of tombs, and the grave-goods that

filled them, survived in greater numbers. In the southern Etruscan area, tombs contain

large, rock-cut chambers under a tumulus in large necropoli.

There is some debate among

historians as to whether Rome was founded by Italic cultures and then invaded

by the Etruscans, or whether Etruscan cultural objects were adopted

subsequently by Roman peoples. In other words, it is unclear whether Etruscan

cultural objects are influences upon Roman culture, or part of native Roman

heritage. Among archaeologists, the main criteria for deciding whether or not

an object originated in Rome, or descended to the Romans from the Etruscans, is

the date of the object, which is often determined by process of carbon dating.

After this process, the opinion of ancient sources is consulted.

Although Diodorus of Sicily wrote in the 1st century of the great

achievements of the Etruscans, little survives or is known of it. Most Etruscan

script that does survive are fragments of religious and funeral texts. However, it is

evident, from Etruscan visual art, that Greek myths were well known.

8.1.3: Etruscan Religion

The Etruscan belief system was heavily

influenced by other religions in the region, and placed heavy emphasis on the divination

of the gods’ wills to guide human affairs.

Learning Objective

Describe some of the key characteristics of the

Etruscan belief system

Key Points

- The Etruscan system of belief was an immanent polytheism, meaning

all visible phenomena were considered to be a manifestation of divine power, and

that power was subdivided into deities that acted continually on the world of

man. - The Etruscan scriptures were a corpus

of texts termed the Etrusca Disciplina,

a set of rules for the conduct of all divination. - Three layers of deities are evident in the extensive Etruscan art

motifs: indigenous, Indo-European, and Greek. - Etruscan beliefs concerning

the afterlife were influenced by a number of sources, particularly those of the

early Mediterranean region.

Key Terms

- polytheism

-

The

worship of, or belief in, multiple deities, usually assembled into a pantheon of

gods and goddesses, each with their own specific religions and rituals. - Etrusca Disciplina

-

A corpus

of texts that comprised the Etruscan scriptures, which essentially provided a

systematic guide to divination.

The

Etruscan system of belief was an immanent polytheism; that is, all visible

phenomena were considered to be a manifestation of divine power and that power

was subdivided into deities that acted continually on the world of man, and

could be dissuaded or persuaded in favor of human affairs. The Greek polytheistic

approach was similar to the Etruscan religious and cultural base. As the Romans

emerged from the legacy created by both of these groups, it shared in a belief

system of many gods and deities.

Etrusca Disciplina

The Etruscan scriptures were a corpus

of texts, termed the Etrusca Disciplina.

These texts were not scriptures in the typical sense, and foretold

no prophecies. The Etruscans did not appear to have a systematic rubric for

ethics or morals. Instead, they concerned themselves with the problem of

understanding the will of the gods, which the Etruscans considered inscrutable.

The Etruscans did not attempt to rationalize or explain divine actions or

intentions, but to simply divine what the gods’ wills were through an elaborate

system of divination. Therefore, the Etrusca Disciplina is mainly a set of

rules for the conduct of all sorts of divination. It does not dictate what laws

shall be made or how humans are to behave, but instead elaborates rules for how

to ask the gods these questions and receive their answers.

Divinations were conducted by

priests, who the Romans called haruspices

or sacerdotes. A special magistrate

was designated to look after sacred items, but every man had religious responsibilities.

In this way, the Etruscans placed special emphasis upon intimate contact with

divinity, consulting with the gods and seeking signs from them before embarking

upon a task.

Spirits and Deities

Three layers of deities are evident in the extensive Etruscan art

motifs. One appears to be divinities of an indigenous nature: Catha and Usil,

the sun; Tivr, the moon; Selvans, a civil god; Turan, the goddess of love;

Laran, the god of war; Leinth, the goddess of death; Maris; Thalna; Turms; and

the ever-popular Fufluns, whose name is related in some unknown way to the city

of Populonia and the populus Romanus (the Roman people). Ruling over this

pantheon of lesser deities were higher ones that seem to reflect the

Indo-European system: Tin or Tinia, the sky; Uni, his wife (Juno); and Cel, the

earth goddess. In addition, the Greek gods were taken into the Etruscan system:

Aritimi (Artemis), Menrva (Minerva), and Pacha (Bacchus). The Greek heroes

taken from Homer also appear extensively in art motifs.

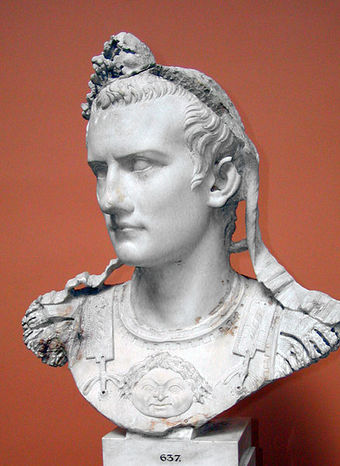

Mars of Todi

The Mars of Todi, a life-sized Etruscan bronze sculpture of a soldier making a votive offering, most likely to Laran, the Etruscan god of war; late 5th to early 4th century BCE.

The Afterlife

Etruscan beliefs concerning the afterlife seem to be

influenced by a number of sources. The Etruscans shared in general early

Mediterranean beliefs. For instance, much like the Egyptians, the Etruscans

believed that survival and prosperity in the afterlife depended on the

treatment of the deceased’s remains. Souls of ancestors are found depicted

around Etruscan tombs, and after the 5th century BCE, the deceased are

depicted in iconography as traveling to the underworld. In several instances,

spirits of the dead are referred to as hinthial,

or one who is underneath. The transmigrational world beyond the grave was

patterned after the Greek Hades and ruled by Aita. The deceased were guided

there by Charun, the equivalent of Death, who was blue and wielded a hammer.

The Etruscan version of Hades was populated by Greek mythological figures, some

of which were of composite appearance to those in Greek mythology.

Etruscan tombs imitated

domestic structures, contained wall paintings and even furniture, and were

spacious. The deceased was depicted in the tomb at the prime of their life, and

often with a spouse. Not everyone had a sarcophagus, however. Some deceased

individuals were laid out on stone benches, and depending on the proportion of

inhumation, versus cremation, rites followed, cremated ashes and bones might be

put into an urn in the shape of a house, or in a representation of the deceased.

Reconstruction of an Etruscan Temple

19th century reconstruction of an Etruscan temple, in the courtyard of the Villa Giulia Museum in Rome, Italy.

8.2: Early Rome

8.2.1: The Founding of Rome

Myths surrounding the founding of Rome describe the city’s origins through the lens of later figures and events.

Learning Objective

Explain how the founding of Rome is rooted in mythology

Key Points

- The national epic poem of mythical Rome, the Aeneid by Virgil, tells the story of how the Trojan prince, Aeneas, came to Italy. The Aeneid was written under the emperor Augustus, who, through Julius Caesar, claimed ancestry from Aeneas.

- The Alba Longan line, begun by Iulus, Aeneas’s son, extends to King Procas, who fathered two sons, Numitor and Amulius.

According to the myth of Romulus and Remus,Amulius captured Numitor, sent him to prison, and forced the daughter of Numitor, Rhea Silvia, to become a virgin priestess among the Vestals.

- Despite Amulius’ best efforts, Rhea Silvia had twin boys, Romulus and Remus, by Mars. Romulus and Remus eventually overthrew Amulius, and restored Numitor.

- In the course of a dispute during the founding of the city of Rome, Romulus killed Remus. Thus Rome began with a fratricide, a story that was later taken to represent the city’s history of internecine political strife and bloodshed.

- According to the archaeological record of the

region, the development of Rome itself is presumed to have coalesced around the

migrations of various Italic tribes, who originally inhabited the Alban Hills as

they moved into the agriculturally-superior valley near the Tiber River. - The discovery of a series of fortification walls

on the north slope of Palatine Hill, most likely dating to the middle of the

8th century BCE, provide the strongest evidence of the original site and

date of the founding of the city of Rome.

Key Terms

- Romulus

-

The founder of Rome, and one of two twin sons of Rhea Silvia and Mars.

- Aeneas

-

A Trojan survivor of the Trojan War who, according to legend, journeyed to Italy and founded the bloodline that would eventually lead to the Julio-Claudian emperors.

- Rome

-

An Italic civilization that began on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BCE. Located along the Mediterranean Sea, and centered on one city, it expanded to become one of the largest empires in the ancient world.

The founding of Rome can be investigated through archaeology, but traditional stories, handed down by the ancient Romans themselves, explain the earliest history of their city in terms of legend and myth. The most familiar of these myths, and perhaps the most famous of all Roman myths, is the story of Romulus and Remus, the twins who were suckled by a she-wolf. This story had to be reconciled with a dual tradition, set earlier in time.

Romulus and the Founding of Rome

The Capitoline Wolf

The iconic sculpture of Romulus and Remus being suckled by the she-wolf who raised them. Traditional scholarship says the wolf-figure is Etruscan, 5th century BCE, with figures of Romulus and Remus added in the 15th century CE by Antonio Pollaiuolo. Recent studies suggest that the wolf may be a medieval sculpture dating from the 13th century CE.

Romulus and Remus were purported to be sons of Rhea Silvia and Mars, the god of war. Because of a prophecy that they would overthrow their great-uncle Amulius, who had overthrown Silvia’s father, Numitor, they were, in the manner of many mythological heroes, abandoned at birth. Both sons were left to die on the Tiber River, but were saved by a number of miraculous interventions. After being carried to safety by the river itself, the twins were nurtured by a she-wolf and fed by a woodpecker, until a shepherd, named Faustulus, found them and took them as his sons.

When Remus and Romulus became adults and learned the truth about their birth and upbringing, they killed Amulius and restored Numitor to the throne.

Rather than wait to inherit Alba Longa, the city of their birth, the twins

decided to establish their own city. They quarreled, however,

over where to locate the new city, and in the process of their dispute, Romulus killed his brother. Thus Rome began with a fratricide, a story that was later taken to represent the city’s history of internecine political strife and bloodshed.

Aeneas and the Aeneid

The national epic of mythical Rome, the Aeneid by Virgil, tells the story of how the Trojan

prince, Aeneas, came to Italy. Although the Aeneid

was written under the emperor Augustus between 29 and 19 BCE, it tells the

story of the founding of Rome centuries before Augustus’s time. The hero, Aeneas, was already well known within Greco-Roman legend and myth, having been a

character in the Iliad. But Virgil

took the disconnected tales of Aeneas’s wanderings, and his vague association

with the foundation of Rome, and fashioned it into a compelling foundation myth

or national epic. The story tied Rome to the legends of Troy, explained the Punic Wars,

glorified traditional Roman virtues, and legitimized the Julio-Claudian

dynasty as descendants of the founders, heroes, and gods of Rome and Troy.

Virgil makes use of symbolism to draw comparisons between the

emperor Augustus and Aeneas, painting them both as founders of Rome. The Aeneid also contains prophecies about Rome’s

future, the deeds of Augustus, his ancestors, and other famous Romans. The

shield of Aeneas even depicts Augustus’s victory at Actium in 31 BCE. Virgil

wrote the Aeneid during a time of

major political and social change in Rome, with the fall of the republic and

the Final War of the Roman Republic tearing through society and causing many to

question Rome’s inherent greatness. In this context, Augustus instituted a new

era of prosperity and peace through the reintroduction of traditional Roman

moral values. The Aeneid was seen as

reflecting this aim by depicting Aeneas as a man devoted and loyal to his country

and its greatness, rather than being concerned with his own personal gains. The Aeneid also gives mythic legitimization

to the rule of Julius Caesar, and by extension, to his adopted son, Augustus, by

immortalizing the tradition that renamed Aeneas’s son Iulus, making him an

ancestor to the family of Julius Caesar.

According to the Aeneid, the survivors from the fallen city of Troy banded together

under Aeneas, underwent a series of adventures around the Mediterranean Sea,

including a stop at newly founded Carthage under the rule of Queen Dido, and

eventually reached the Italian coast. The Trojans were thought to have landed

in an area between modern Anzio and Fiumicino, southwest of Rome, probably at

Laurentum, or in other versions, at Lavinium, a place named for Lavinia, the

daughter of King Latinus, who Aeneas married. Aeneas’ arrival started a series

of armed conflicts with Turnus over the marriage of Lavinia. Before the arrival

of Aeneas, Turnus was engaged to Lavinia, who then married Aeneas, which began

the conflict. Aeneas eventually won the war and killed Turnus, which granted

the Trojans the right to stay and to assimilate with the local peoples. The

young son of Aeneas, Ascanius, also known as Iulus, went on to found Alba Longa

and the line of Alban kings who filled the chronological gap between the Trojan

saga and the traditional founding of Rome in the 8th century BCE.

Toward the end of

this line, King Procas appears as the father of Numitor and Amulius. At Procas’

death, Numitor became king of Alba

Longa, but Amulius captured him and sent him to prison. He also forced the

daughter of Numitor, Rhea Silvia, to become a virgin priestess among the

Vestals. For many years, Amulius was the king. The tortuous nature of the

chronology is indicated by Rhea Silvia’s ordination among the Vestals, whose

order was traditionally said to have been founded by the successor of Romulus,

Numa Pompilius.

The Archaeological Record

According to the archaeological record of the region, the

Italic tribes who originally inhabited the Alban Hills moved down into the

valleys, which provided better land for agriculture. The area around the Tiber

River was particularly advantageous and offered many strategic resources. For

instance, the river itself provided a natural border on one side of the

settlement, and the hills on the other side provided another defensive position

for the townspeople. A settlement in this area would have also allowed for

control of the river, including commercial and military traffic, as well as a

natural observation point at Isola Tiberina. This was especially important, since

Rome was at the intersection of the principal roads to the sea from Sabinum and

Etruria, and traffic from those roads could not be as easily controlled.

The development of Rome itself is presumed to

have coalesced around the migrations of these various tribes into the valley,

as evidenced by differences in pottery and burial techniques. The discovery of

a series of fortification walls on the north slope of Palatine Hill, most

likely dating to the middle of the 8th century BCE, provide the strongest

evidence for the original site and date of the founding of the city of Rome.

8.2.2: The Seven Kings

For its first 200 years, Rome was ruled by seven kings, each of whom is credited either with establishing a key Roman tradition or constructing an important building.

Learning Objective

Explain the significance of the Seven Kings of Rome to Roman culture

Key Points

- Romulus was Rome’s first king and the city’s founder. He is best known for the Rape of the Sabine Women and the establishment of the Senate, as well as various voting practices.

- Numa Pompilius was a just, pious king who established the cult of the Vestal Virgins at Rome, and the position of Pontifex Maximus. His reign was characterized by peace.

- Tullus Hostilius had little regard for the Roman gods, and focused entirely on military expansion. He constructed the home of the Roman Senate, the Curia Hostilia.

- Ancus Marcius ruled peacefully and only fought wars when Roman territories needed defending.

- Lucius Tarquinius Priscus increased the size of the Senate and began major construction works, including the Temple to Jupiter Optimus Maximus, and the Circus Maximus.

- Servius Tullius built the first pomerium—

walls that fully encircled the Seven Hills of Rome. He also made organizational changes to the Roman army, and implemented a new constitution for the Romans, further developing the citizen classes.

- Lucius Tarquinius Superbus’s reign is remembered for his use of violence and intimidation, as well as his disrespect of Roman custom and the Roman Senate. He was eventually overthrown, thus leading to the establishment of the Roman Republic.

Key Terms

- absolute monarchy

-

A monarchical form of government in which the monarch has absolute power

among his or her people. This amounts to unrestricted political power over a

sovereign state and its people. - patrician

-

A group of elite families in ancient Rome.

The first 200 years of Roman history occurred under a monarchy. Rome was ruled by seven kings over this period of time,

and each of their reigns were characterized by

the personality of the ruler in question. Each of these kings is credited either with establishing a key Roman tradition, or constructing an important building.

None of the seven kings were known to be dynasts, and no reference is made to the hereditary nature of kingdom until after the

fifth king, Tarquinius Priscus.

The king of Rome possessed absolute power over

the people, and the Senate provided only a weak,

oligarchic counterbalance to his power, primarily exercising only minor

administrative powers. For these reasons, the kingdom of Rome is considered an

absolute monarchy. Despite this, Roman kings, with the exception of Romulus, were

elected by citizens of Rome who occupied the Curiate Assembly. There, members

would vote on candidates that had been nominated by a chosen member of the Senate, called an interrex. Candidates could be chosen from any source.

Romulus

Romulus was Rome’s legendary first king and the city’s founder. In 753 BCE, Romulus began building the city upon the Palatine Hill. After founding and naming Rome, as the story goes, he permitted men of all classes to come to Rome as citizens, including slaves and freemen, without distinction. To provide his citizens with wives, Romulus invited the neighboring tribes to a festival in Rome where he abducted the young women amongst them (this is known as The Rape of the Sabine Women). After the ensuing war with the Sabines, Romulus shared the kingship with the Sabine king, Titus Tatius. Romulus selected 100 of the most noble men to form the Roman Senate as an advisory council to the king. These men were called patres (from pater: father, head), and their descendants became the patricians. He also established voting, and class structures that would define sociopolitical proceedings throughout the Roman Republic and Empire.

Numa Pompilius

After the death of Romulus, there was an interregnum for one year, during which ten men chosen from the senate governed Rome as successive interreges. Numa Pompilius, a Sabine, was eventually chosen by the senate to succeed Romulus because of his reputation for justice and piety. Numa’s reign was marked by peace and religious reform. Numa constructed a new temple to Janus and, after establishing peace with Rome’s neighbors, shut the doors of the temple to indicate a state of peace. The doors of the temple remained closed for the balance of his reign. He established the cult of the Vestal Virgins at Rome, as well as the “leaping priests,” known as the Salii, and three flamines, or priests, assigned to Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus. He also established the office and duties of Pontifex Maximus, the head priest of the Roman state religion.

Tullus Hostilius

Tullus Hostilius was much like Romulus in his warlike behavior, and completely unlike Numa in his lack of respect for the gods. Tullus waged war against Alba Longa, Fidenae and Veii, and the Sabines. It was during Tullus’ reign that the city of Alba Longa was completely destroyed, after which Tullus integrated its population into Rome. According to the Roman historian Livy, Tullus neglected the worship of the gods until, towards the end of his reign, he fell ill and became superstitious. However, when Tullus called upon Jupiter and begged assistance, Jupiter responded with a bolt of lightning that burned the king and his house to ashes. Tullus is attributed with constructing a new home for the Senate, the Curia Hostilia, which survived for 562 years after his death.

Ancus Marcius

Following the death of Tullus, the Romans elected a peaceful and religious king in his place—Numa’s grandson, Ancus Marcius. Much like his grandfather, Ancus did little to expand the borders of Rome, and only fought war when his territories needed defending.

Lucius Tarquinius Priscus

Lucius Tarquinius Priscus was the fifth king of Rome and the first of Etruscan birth. After immigrating to Rome, he gained favor with Ancus, who later adopted him as his son. Upon ascending the throne, he waged wars against the Sabines and Etruscans, doubling the size of Rome and bringing great treasures to the city.One of his first reforms was to add 100 new members to the Senate from the conquered Etruscan tribes, bringing the total number of senators to 200. He used the treasures Rome had acquired from conquests to build great monuments for Rome, including the Roman Forum, the temple to Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill, and the Circus Maximus. His reign is best remembered for the introduction of Etruscan symbols of military distinction and civilian authority

into the Roman tradition, including the scepter of the king, the rings

worn by senators, and the use of the tuba for military purposes.

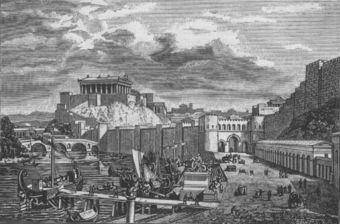

The Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus

19th century illustration depicting the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus above the Tiber River during the Roman Republic.

Servius Tullus

Following Priscus’s death, his son-in-law, Servius Tullius, succeeded him to the throne. Like his father-in-law before him, Servius fought successful wars against the Etruscans. He used the treasure from his campaigns to build the first pomerium—walls that fully encircled the Seven Hills of Rome. He also made organizational changes to the Roman army, and was renowned for implementing a new constitution for the Romans and further developing the citizen classes. Servius’s reforms brought about a major change in Roman life—voting rights were now based on socioeconomic status, transferring much of the power into the hands of the Roman elite. The 44-year reign of Servius came to an abrupt end when he was assassinated in a conspiracy led by his own daughter, Tullia, and her husband, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus.

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus

While in power, Tarquinius conducted a number of wars against Rome’s neighbors, including the Volsci, Gabii, and the Rutuli. Tarquinius also engaged in a series of public works, notably the completion of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill. Tarquin’s reign, however, is best remembered for his use of violence and intimidation in his attempts to maintain control over Rome, as well as his disrespect of Roman custom and the Roman Senate. Tensions came to a head when the king’s son, Sextus Tarquinius, raped Lucretia, wife and daughter to powerful Roman nobles. Lucretia then told her relatives about the attack and subsequently committed suicide to avoid the dishonor of the episode. Four men, led by Lucius Junius Brutus, incited a revolution, and as a result, Tarquinius and his family were deposed and expelled from Rome in 509 BCE. Because of his actions and the way they were viewed by the people, the word for King, rex, held a negative connotation in Roman culture until the fall of the Roman Empire. Brutus and Collatinus became Rome’s first consuls, marking the beginning of the Roman Republic. This new government would survive for the next 500 years, until the rise of Julius Caesar and Caesar Augustus, and cover a period in which Rome’s authority and area of control extended to cover great areas of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.

8.2.3: Early Roman Society

Multiple,

overlapping hierarchies characterized Roman society, which was also highly

patriarchal.

Learning Objective

Describe

what Roman society was like in its early years

Key Points

- Roman society was extremely patriarchal and

hierarchical. The adult male head of a household had special legal powers and

privileges that gave him jurisdiction over all the members of his family. - The status of freeborn Romans was established by

their ancestry, census ranking, and citizenship. - The most important division within Roman society

was between patricians, a small elite who monopolized political power, and

plebeians, who comprised the majority of Roman society. - The Roman census divided citizens into six

complex classes based on property holdings. - Most adult, free-born men within the city limits

of Rome held Roman citizenship. Classes of non-citizens existed and held

different legal rights.

Key Terms

- tax farming

-

A

technique of financial management in which future, uncertain revenue streams are

fixed into periodic rents via assignment by legal contract to a third party. - plebeians

-

A

general body of free Roman citizens who were part of the lower strata of

society. - patricians

-

A

group of ruling class families in ancient Rome.

Roman society was extremely patriarchal and hierarchical. The

adult male head of a household had special legal powers and privileges that

gave him jurisdiction over all the members of his family, including his wife,

adult sons, adult married daughters, and slaves, but there were multiple, overlapping

hierarchies at play within society at large. An individual’s relative position

in one hierarchy might have been higher or lower than it was in another. The status of

freeborn Romans was established by the following:

- Their ancestry

- Their census rank, which in turn was determined by the

individual’s wealth and political privilege -

Citizenship, of which there were grades with

varying rights and privileges

Ancestry

The most important division within Roman society was between

patricians, a small elite who monopolized political power, and plebeians, who

comprised the majority of Roman society. These designations were established at

birth, with patricians tracing their ancestry back to the first Senate

established under Romulus. Adult, male non-citizens fell outside the realms of

these divisions, but women and children, who were also not considered formal

citizens, took the social status of their father or husband. Originally, all

public offices were only open to patricians and the classes could not

intermarry, but, over time, the differentiation between patrician and plebeian statuses

became less pronounced, particularly after the establishment of the Roman

republic.

Census Rankings

The Roman census divided citizens into six complex classes based on property holdings. The richest class was called the senatorial class,

with wealth based on ownership of large agricultural estates, since members of

the highest social classes did not traditionally engage in commercial activity.

Below the senatorial class was the equestrian order, comprised of members who

held the same volume of wealth as the senatorial classes, but who engaged in

commerce, making them an influential early business class. Certain political

and quasi-political positions were filled by members of the equestrian order,

including tax farming and leadership of the Praetorian Guard. Three additional

property-owning classes occupied the rungs beneath the equestrian order.

Finally, the proletarii occupied the bottom rung with the lowest property

values in the kingdom.

Citizenship

Citizenship in ancient Rome afforded political and legal

privileges to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance.

Most adult, free-born men within the city limits of Rome held Roman citizenship.

Men who lived in towns outside of Rome might also hold citizenship, but some

lacked the right to vote. Free-born, foreign subjects during this period were

known as peregrini, and special laws existed to govern their conduct and

disputes, though they were not considered Roman citizens during the Roman

kingdom period. Free-born women in ancient Rome were considered citizens, but

they could not vote or hold political office. The status of woman’s citizenship

affected the citizenship of her offspring. For example, in a type of Roman marriage

called conubium, both spouses must be

citizens in order to marry. Additionally, the phrase ex duobus civibus Romanis natos, translated to mean “children born

of two Roman citizens,” reinforces the importance of both parents’ legal status

in determining that of their offspring.

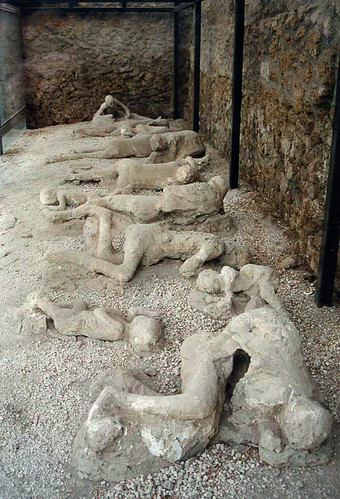

Roman citizenship

The toga, shown here on a statue restored with the head of Nerva, was the distinctive garb of Roman citizens

Classes of non-citizens existed and held different legal

rights. Under Roman law, slaves were considered property and held no rights. However, certain laws did regulate the institution of slavery, and

extended protections to slaves that were not granted to other forms of

property. Slaves who had been manumitted became freedmen and enjoyed largely

the same rights and protections as free-born citizens. Many slaves descended

from debtors or prisoners of war, especially women and children who were

captured during foreign military campaigns and sieges.

Ironically, many slaves originated from Rome’s conquest of

Greece, and yet Greek culture was considered, in some respects by the Romans, to

be superior to their own. In this way, it seems Romans regarded slavery as a

circumstance of birth, misfortune, or war, rather than being limited to, or

defined by, ethnicity or race. Because it was defined mainly in terms of a lack

of legal rights and status, it was also not considered a permanent or

inescapable position. Some who had received educations or learned skills that

allowed them to earn their own living were manumitted upon the death of their

owner, or allowed to earn money to buy their freedom during their owner’s

lifetime. Some slave owners also freed slaves who they believed to be their

natural children. Nonetheless, many worked under harsh conditions, and/or

suffered inhumanely under their owners during their enslavement.

Most freed slaves joined the lower plebeian classes, and

worked as farmers or tradesmen, though as time progressed and their numbers

increased, many were also accepted into the equestrian class. Some went on to

populate the civil service, whereas others engaged in commerce, amassing vast

fortunes that were rivaled only by those in the wealthiest classes.

8.3: The Roman Republic

8.3.1: The Establishment of the Roman Republic

After the public

outcry that arose as a result of the rape of Lucretia, Romans overthrew the unpopular king, Lucius

Tarquinius Superbus, and established a republican form of government.

Learning Objective

Explain why and how Rome transitioned from a

monarchy to a republic

Key Points

- The Roman

monarchy was overthrown around 509 BCE, during a political revolution that

resulted in the expulsion of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the last king of Rome. - Despite waging a

number of successful campaigns against Rome’s neighbors, securing Rome’s

position as head of the Latin cities, and engaging in a series of public works,

Tarquinius was a very unpopular king, due to his violence and abuses of power. - When word spread

that Tarquinius’s son raped Lucretia, the wife of the governor of Collatia, an uprising

occurred in which a number of prominent patricians argued for a change in

government. - A general

election was held during a legal assembly, and participants voted in favor of

the establishment of a Roman republic. - Subsequently, all Tarquins were exiled from Rome and an interrex and two

consuls were established to lead the new republic.

Key Terms

- interrex

-

Literally, this translates to mean a ruler that

presides over the period between the rule of two separate kings; or, in other

words, a short-term regent. - plebeians

-

A

general body of free Roman citizens who were part of the lower strata of

society. - patricians

-

A

group of ruling class families in ancient Rome.

The Roman monarchy was

overthrown around 509 BCE, during a political revolution that resulted in the

expulsion of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the last king of Rome. Subsequently,

the Roman Republic was established.

Background

Tarquinius was the son of

Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, the fifth king of Rome’s Seven Kings period. Tarquinius was married to Tullia Minor, the daughter of Servius Tullius, the sixth king of Rome’s Seven

Kings period. Around 535 BCE, Tarquinius and his wife, Tullia

Minor, arranged for the murder of his father-in-law. Tarquinius became king

following Servius Tullius’s death.

Tarquinius waged a number of

successful campaigns against Rome’s neighbors, including the Volsci, Gabii, and

the Rutuli. He also secured Rome’s position as head of the Latin cities, and

engaged in a series of public works, such as the completion of the Temple of

Jupiter Optimus Maximus. However, Tarquinius remained an unpopular king for a

number of reasons. He refused to bury his predecessor and executed a number of

leading senators whom he suspected remained loyal to Servius. Following these

actions, he refused to replace the senators he executed and refused to consult the

Senate in matters of government going forward, thus diminishing the size and

influence of the Senate greatly. He also went on to judge capital criminal

cases without the advice of his counselors, stoking fear among his political

opponents that they would be unfairly targeted.

The Rape of Lucretia and An

Uprising

Tarquin and Lucretia

Titian’s Tarquin and Lucretia (1571).

During Tarquinius’s war with

the Rutuli, his son, Sextus Tarquinius, was sent on a military errand to

Collatia, where he was received with great hospitality at the governor’s

mansion. The governor’s wife, Lucretia, hosted Sextus while the governor was

away at war. During the night, Sextus entered her bedroom and raped her. The next

day, Lucretia traveled to her father, Spurius Lucretius, a distinguished

prefect in Rome, and, before witnesses, informed him of what had happened.

Because her father was a chief magistrate of Rome, her pleas for justice and

vengeance could not be ignored. At the end of her pleas, she stabbed

herself in the heart with a dagger, ultimately dying in her own father’s arms.

The scene struck those who had witnessed it with such horror that they

collectively vowed to publicly defend their liberty against the outrages of

such tyrants.

Lucius Junius Brutus, a

leading citizen and the grandson of Rome’s fifth king, Tarquinius Priscus, publicly

opened a debate on the form of government that Rome should have in place of the

existing monarchy. A number of patricians attended the debate, in which Brutus

proposed the banishment of the Tarquins from all territories of Rome, and the

appointment of an interrex to nominate new magistrates and to oversee an

election of ratification. It was decided that a republican form of government

should temporarily replace the monarchy, with two consuls replacing the king

and executing the will of a patrician senate. Spurius Lucretius was elected

interrex, and he proposed Brutus, and Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, a leading

citizen who was also related to Tarquinius Priscus, as the first two consuls.

His choice was ratified by the comitia

curiata, an organization of patrician families who primarily ratified

decrees of the king.

In order to rally the

plebeians to their cause, all were summoned to a legal assembly in the forum, and Lucretia’s body was paraded through the streets. Brutus gave a speech and a

general election was held. The results were in favor of a republic. Brutus left

Lucretius in command of the city as interrex, and pursued the king in Ardea

where he had been positioned with his army on campaign. Tarquinius, however,

who had heard of developments in Rome, fled the camp before Brutus arrived, and

the army received Brutus favorably, expelling the king’s sons from their

encampment. Tarquinius was subsequently refused entry into Rome and lived as an

exile with his family.

The Establishment of the

Republic

Brutus and Lucretia

The statue shows Brutus holding the knife and swearing the oath, with Lucretia.

Although there is no

scholarly agreement as to whether or not it actually took place, Plutarch and

Appian both claim that Brutus’s first act as consul was to initiate an oath for

the people, swearing never again to allow a king to rule Rome. What is known

for certain is that he replenished the Senate to its original number of 300

senators, recruiting men from among the equestrian class. The new consuls

also created a separate office, called the rex sacrorum, to carry out and oversee

religious duties, a task that had previously fallen to the king.

The two consuls continued to be elected annually by Roman citizens and

advised by the senate. Both consuls were elected for one-year terms and could

veto each other’s actions. Initially, they were endowed with all the powers of

kings past, though over time these were broken down further by the addition of

magistrates to the governmental system. The first magistrate added was the praetor,

an office that assumed judicial authority from the consuls. After the praetor,

the censor was established, who assumed the power to conduct the Roman census.

8.3.2: Structure of the Republic

The Roman Republic was composed of the Senate, a number of legislative assemblies, and elected magistrates.

Learning Objective

Describe the political structure of the Roman Republic

Key Points

- The Constitution of the Roman Republic was a set of guidelines and principles passed down, mainly through precedent. The constitution was largely unwritten and uncodified, and evolved over time.

-

Roman citizenship was a

vital prerequisite to possessing many important legal rights.The Senate passed decrees that were called senatus consulta, ostensibly “advice” from the senate to a magistrate. The focus of the Roman Senate was usually foreign policy.

- There were two types of legislative assemblies. The first was the comitia (“committees”), which were assemblies of all Roman citizens. The second was the concilia (“councils”), which were assemblies of specific groups of citizens.

- The comitia centuriata was the assembly of the centuries (soldiers), and they elected magistrates who had imperium powers (consuls and praetors). The comitia tributa, or assembly of the tribes (the citizens of Rome), was presided over by a consul and composed of 35 tribes. They elected quaestors, curule aediles, and military tribunes.

- Dictators were sometimes elected during times of military emergency, during which the constitutional government would be disbanded.

Key Terms

- patricians

-

A

group of ruling class families in ancient Rome. - plebeian

-

A general body of free Roman citizens who were part of the lower strata of society.

- Roman Senate

-

A political institution in the ancient Roman Republic. It was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors.

The Constitution of the Roman Republic was a set of guidelines and principles passed down, mainly through precedent. The constitution was largely unwritten and uncodified, and evolved over time. Rather than creating a government that was primarily a democracy (as was ancient Athens), an aristocracy (as was ancient Sparta), or a monarchy (as was Rome before, and in many respects after, the Republic), the Roman constitution mixed these three elements

of governance into their overall political system. The democratic element took the form of legislative assemblies; the aristocratic element took the form of the Senate; and the monarchical element took the form of the many term-limited consuls.

The Roman SPQR Banner

“SPQR” (senatus populusque romanus) was the Roman motto, which stood for “the Senate and people of Rome”.

The Roman Senate

The Senate’s ultimate authority derived from the esteem and prestige of the senators, and was based on both precedent and custom. The Senate passed decrees, which were called senatus consulta, ostensibly “advice” handed down from the senate to a magistrate. In practice, the magistrates usually followed the senatus consulta. The focus of the Roman Senate was usually foreign policy. However, the power of the Senate expanded over time as the power of the legislative assemblies declined, and eventually the Senate took a greater role in civil law-making. Senators were usually appointed by Roman censors, but during times of military emergency, such as the civil wars of the 1st century BCE, this practice became less prevalent, and the Roman dictator, triumvir, or the Senate itself would select its members.

Curia Iulia – The Roman Senate House

The Curia Julia in the Roman Forum, the seat of the imperial Senate.

Legislative Assemblies

Roman citizenship was a vital prerequisite to possessing many important legal rights, such as the rights to trial and appeal, marriage, suffrage, to hold office, to enter binding contracts, and to enjoy special tax exemptions. An adult male citizen with full legal and political rights was called optimo jure. The optimo jure elected assemblies, and the assemblies elected magistrates, enacted legislation, presided over trials in capital cases, declared war and peace, and forged or dissolved treaties. There were two types of legislative assemblies. The first was the comitia (“committees”), which were assemblies of all optimo jure. The second was the concilia (“councils”), which were assemblies of specific groups of optimo jure.

Citizens on these assemblies were organized further on the basis of

curiae

(familial groupings), centuries

(for

military purposes), and tribes (for civil purposes), and each would each gather into their own assemblies.

The

Curiate Assembly served only a symbolic purpose in the late Republic, though

the assembly was used to ratify the powers of newly elected magistrates by

passing laws known as leges curiatae. The comitia centuriata was the assembly of the centuries (soldiers). The president of the comitia centuriata was usually a consul, and the comitia centuriata would elect magistrates who had imperium powers (consuls and praetors). It also elected censors. Only the comitia centuriata could declare war and ratify the results of a census. It also served as the highest court of appeal in certain judicial cases.

The assembly of the tribes, the comitia tributa, was presided over by a consul, and was composed of 35 tribes. The tribes were not ethnic or kinship groups, but rather geographical subdivisions. While it did not pass many laws, the comitia tributa did elect quaestors, curule aediles, and military tribunes. The Plebeian Council was identical to the assembly of the tribes, but excluded the patricians. They elected their own officers, plebeian tribunes, and plebeian aediles. Usually a plebeian tribune would preside over the assembly. This assembly passed most laws, and could also act as a court of appeal.

Since

the tribunes were considered to be the embodiment of the plebeians, they were

sacrosanct. Their sacrosanctness was enforced by a pledge, taken by the plebeians,

to kill any person who harmed or interfered with a tribune during his term of

office. As such, it was considered a capital offense to harm a tribune, to

disregard his veto, or to interfere with his actions. In times of military

emergency, a dictator would be appointed for a term of six months. The

constitutional government would be dissolved, and the dictator would be the

absolute master of the state. When the dictator’s term ended, constitutional

government would be restored.

Executive Magistrates

Magistrates were the

elected officials of the Roman republic. Each magistrate was vested with a

degree of power, and the dictator, when there was one, had the highest level of

power. Below the dictator was the censor (when they existed), and the consuls, the

highest ranking ordinary magistrates. Two were elected every year and wielded

supreme power in both civil and military powers. The ranking among both consuls

flipped every month, with one outranking the other.

Below the consuls were

the praetors, who administered civil law, presided over the courts, and

commanded provincial armies. Censors conducted the Roman census, during which

time they could appoint people to the Senate. Curule aediles were officers

elected to conduct domestic affairs in Rome, who were vested with powers over

the markets, public games, and shows. Finally, at the bottom of magistrate

rankings were the quaestors, who usually assisted the consuls in Rome and the

governors in the provinces with financial tasks. Plebeian tribunes and plebeian

aediles were considered representatives of the people, and acted as a popular

check over the Senate through use of their veto powers, thus safeguarding the

civil liberties of all Roman citizens.

Each magistrate could

only veto an action that was taken by an equal or lower ranked magistrate. The

most significant constitutional power a magistrate could hold was that of imperium

or command, which was held only by consuls and praetors. This gave the

magistrate in question the constitutional authority to issue commands, military

or otherwise.

Election to a magisterial

office resulted in automatic membership in the Senate for life, unless

impeached. Once a magistrate’s annual term in office expired, he had to wait at

least ten years before serving in that office again. Occasionally, however, a

magistrate would have his command powers extended through prorogation, which effectively

allowed him to retain the powers of his office as a promagistrate.

8.3.3: Roman Society Under the Republic

The bulk of Roman politics prior to the 1st century BCE focused on inequalities among the orders.

Learning Objective

Describe the relationship between the government

and the people in the time of the Roman Republic

Key Points

- A number of

developments affected the relationship between Rome’s republican government and

society, particularly in regard to how that relationship differed among

patricians and plebeians. - In 494 BCE, plebeian

soldiers refused to march against a wartime enemy, in order to demand the right

to elect their own officials. - The passage of

Lex Trebonia forbade the co-opting of colleagues to fill vacant positions on

tribunes in order to sway voting in favor of patrician blocs over plebeians. - Throughout the

4th century BCE, a series of reforms were passed that required all laws

passed by the plebeian council to have the full force of law over the entire

population. This gave the plebeian tribunes a positive political impact over the

entire population for the first time in Roman history. - In 445 BCE, the

plebeians demanded the right to stand for election as consul. Ultimately, a

compromise was reached in which consular command authority was granted to a

select number of military tribunes. - The Licinio-Sextian

law was passed in 367 BCE; it addressed the economic plight of the plebeians

and prevented the election of further patrician magistrates. - In the decades following the passage of the Licinio-Sextian law, further legislation was enacted that granted

political equality to the plebeians. Nonetheless, it remained difficult for a

plebeian from an unknown family to enter the Senate, due to the rise of a new

patricio-plebeian aristocracy that was less interested in the plight of the

average plebeian.

Key Terms

- plebeian

-

A general body of free Roman citizens who were

part of the lower strata of society. - patricians

-

A group of ruling class families in ancient

Rome.

In the first few centuries

of the Roman Republic, a number of developments affected the relationship

between the government and the Roman people, particularly in regard to how that

relationship differed across the separate strata of society.

The Patrician Era (509-367

BCE)

The last king of Rome,

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, was overthrown in 509 BCE. One of the biggest

changes that occurred as a result was the establishment of two chief

magistrates, called consuls, who were elected by the citizens of Rome for an

annual term. This stood in stark contrast to the previous system, in which a

king was elected by senators, for life. Built in to the consul system were

checks on authority, since each consul could provide balance to the decisions

made by his colleague. Their limited terms of office also opened them up to the

possibility of prosecution in the event of abuses of power. However, when

consuls exercised their political powers in tandem, the magnitude and influence

they wielded was hardly different from that of the old kings.

In 494 BCE, Rome was at war

with two neighboring tribes, and plebeian soldiers refused to march against the

enemy, instead seceding to the Aventine Hill. There, the plebeian soldiers took

advantage of the situation to demand the right to elect their own officials. The

patricians assented to their demands, and the plebeian soldiers returned to

battle. The new offices that were created as a result came to be known as “plebeian

tribunes,” and they were to be assisted by “plebeian aediles.”

In the early years of the

republic, plebeians were not permitted to hold magisterial office. Tribunes and

aediles were technically not magistrates, since they were only elected by fellow

plebeians, as opposed to the unified population of plebeians and patricians.

Although plebeian tribunes regularly attempted to block legislation they

considered unfavorable, patricians could still override their veto with the

support of one or more other tribunes. Tension over this imbalance of power led

to the passage of Lex Trebonia, which forbade the co-opting of colleagues to

fill vacant positions on tribunes in order to sway voting in favor of one or

another bloc. Throughout the 4th century BCE, a series of reforms were

passed that required all laws passed by the plebeian council to have equal force over the entire population, regardless of status as patrician or

plebeian. This gave the plebeian tribunes a positive political impact over the

entire population for the first time in Roman history.

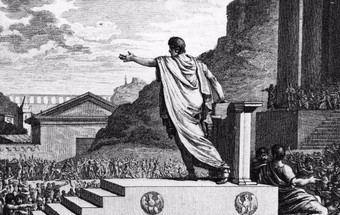

Gaius Gracchus

This 18th century drawing shows Gaius Gracchus, tribune of the people, presiding over the plebeian council.

In 445 BCE, the plebeians

demanded the right to stand for election as consul. The Roman Senate initially refused

them this right, but ultimately a compromise was reached in which consular command

authority was granted to a select number of military tribunes, who, in turn, were

elected by the centuriate assembly with veto power being retained by the

senate.

Around 400 BCE, during a

series of wars that were fought against neighboring tribes, the plebeians

demanded concessions for the disenfranchisement they experienced as

foot soldiers fighting for spoils of war that they were never to see. As a result,

the Licinio-Sextian law was eventually passed in 367 BCE, which addressed the

economic plight of the plebeians and prevented the election of further

patrician magistrates.

The Conflict of the Orders

Ends (367-287 BCE)

In the decades following the passage of the Licinio-Sextian law, further legislation was

enacted that granted political equality to the plebeians. Nonetheless, it

remained difficult for a plebeian from an unknown family to enter the Senate.

In fact, the very presence of a long-standing nobility, and the Roman population’s

deep respect for it, made it very difficult for individuals from unknown

families to be elected to high office. Additionally, elections could be

expensive, neither senators nor magistrates were paid for their services, and

the Senate usually did not reimburse magistrates for expenses incurred during

their official duties, providing many barriers to the entry of high political

office by the non-affluent.

Ultimately, a new

patricio-plebeian aristocracy emerged and replaced the old patrician nobility.

Whereas the old patrician nobility existed simply on the basis of being able to

run for office, the new aristocracy existed on the basis of affluence. Although

a small number of plebeians had achieved the same standing as the patrician

families of the past, new plebeian aristocrats were less interested in the

plight of the average plebeian than were the old patrician aristocrats. For a time,

the plebeian plight was mitigated, due higher employment, income, and patriotism

that was wrought by a series of wars in which Rome was engaged; these things eliminated the

threat of plebeian unrest. But by 287 BCE, the economic conditions of the

plebeians deteriorated as a result of widespread indebtedness, and the

plebeians sought relief. Roman senators, most of whom were also creditors, refused

to give in to the plebeians’ demands, resulting in the first plebeian secession

to Janiculum Hill.

In order to end the plebeian secession, a dictator, Quintus Hortensius,

was appointed. Hortensius, who was himself a plebeian, passed a law known as

the “Hortensian Law.” This law ended the requirement that an auctoritas patrum

be passed before a bill could be considered by either the plebeian council or

the tribal assembly, thus removing the final patrician senatorial check on the

plebeian council. The requirement was not changed, however, in the centuriate

assembly. This provided a loophole through which the patrician senate could still deter

plebeian legislative influence.

8.3.4: Art and Literature in the Roman Republic

Culture flourished during the Roman Republic with the emergence of great authors, such as Cicero and Lucretius, and with the development of Roman relief and portraiture sculpture.

Learning Objective

Recognize the wide extent of art and literature created during the Roman Republic

Key Points

- Roman literature was, from its very inception, influenced heavily by Greek authors. Some of the earliest works we possess are of historical epics that tell the early military history of Rome. However, authors diversified their genres as the Republic expanded.

- Cicero is one of the most famous Republican authors, and his letters provide detailed information about an important period in Roman history.

-

Romans

typically produced historical sculptures in relief, as opposed to Greek

free-standing sculpture. Small sculptures were considered luxury items, while moulded

relief decoration in pottery vessels and small figurines were produced in great

quantities for a wider section of the population. - The most well-known surviving

examples of Roman painting consist of the wall paintings from Pompeii and

Herculaneum that were preserved in the aftermath of the fatal eruption of Mount

Vesuvius in 79 CE. - Veristic portraiture

is a hallmark of Roman art during the Republic, though its use began to diminish during the 1st century BCE as civil wars threatened the empire and individual strong men began amassing more power.

Key Terms

- veristic portraiture

-

A hyper-realistic portrayal of the subject’s facial characteristics; a common style of portraiture in the early to mid-Republic.

- Cicero

-

A Roman philosopher, politician, lawyer, orator, political theorist, consul, and constitutionalist.

Literature

Roman literature was, from its very inception, heavily

influenced by Greek authors. Some of the earliest works we possess are historical epics telling the early military history of Rome, similar to the Greek epic narratives of Homer,

Herodotus, and Thucydides. Virgil, though generally considered to be an Augustan poet, represents the pinnacle of Roman epic poetry.

His Aeneid tells the story of the flight of Aeneas from Troy, and his settlement of the city that would become Rome.

As the Republic expanded, authors began to

produce poetry, comedy, history, and tragedy.

Lucretius, in his De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things), attempted to explicate science in an epic poem. The genre of satire was also common in Rome, and satires were written by, among others, Juvenal and Persius.

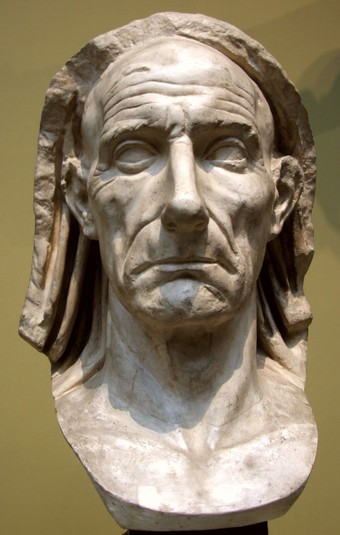

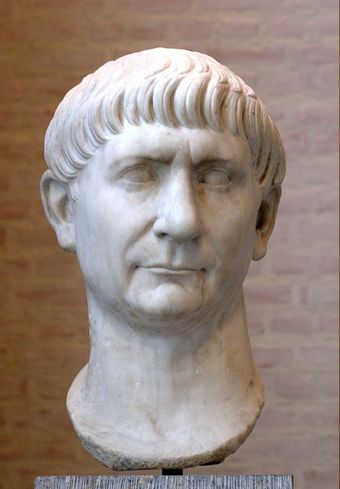

The Age of Cicero

Bust of Cicero

A mid-first century CE bust of Cicero, in the Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Cicero has traditionally been considered the master of Latin prose. The writing he produced from approximately 80 BCE until his death in 43 BCE, exceeds that of any Latin author whose work survives, in terms of quantity and variety of genre and subject matter. It also possesses unsurpassed stylistic excellence. Cicero’s many works can be divided into four groups: letters, rhetorical treatises, philosophical works, and orations. His letters provide detailed information about an important period in Roman history, and offers a vivid picture of public and private life among the Roman governing class. Cicero’s works on oratory are our most valuable Latin sources for ancient theories on education and rhetoric. His philosophical works were the basis of moral philosophy during the Middle Ages, and his speeches inspired many European political leaders, as well as the founders of the United States.

Art

Early Roman art was

greatly influenced by the art of Greece and the neighboring Etruscans, who were

also greatly influenced by Greek art via trade. As the Roman Republic conquered

Greek territory, expanding its imperial domain throughout the Hellenistic world,

official and patrician sculpture grew out of the Hellenistic style that many Romans

encountered during their campaigns, making it difficult to distinguish truly

Roman elements from elements of Greek style. This was especially true since much of what

survives of Greek sculpture are actually copies made of Greek originals by

Romans. By the 2nd century BCE, most sculptors working within Rome were

Greek, many of whom were enslaved following military conquests, and whose names

were rarely recorded with the work they created. Vast numbers of Greek statues

were also imported to Rome as a result of conquest as well as trade.

Rather than create

free-standing works depicting heroic exploits from history or mythology, as the

Greeks had, the Romans produced historical works in relief. Small sculptures

were considered luxury items and were frequently the object of client-patron

relationships. The silver Warren Cup and glass Lycurgus cup are examples of the

high quality works that were produced during this period. For a wider section

of the population, moulded relief decoration in pottery vessels and small figurines

were produced in great quantities, and were often of great quality.

In the 3rd century BCE, Greek art taken during wars became popular, and many Roman homes were decorated with landscapes by Greek artists.

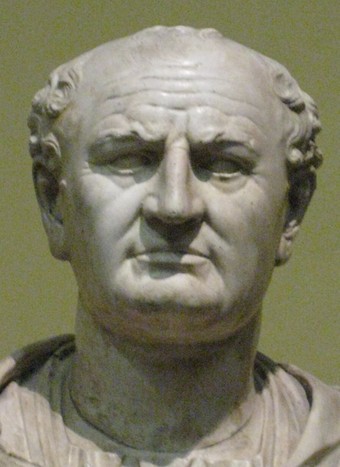

Of the vast body of

Roman painting that once existed, only a few examples survive to the

modern-age. The most well-known surviving examples of Roman painting are the wall paintings from Pompeii and Herculaneum, that were preserved in the

aftermath of the fatal eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. A large number of

paintings also survived in the catacombs of Rome, dating from the 3rd century CE to 400, prior to the Christian age, demonstrating a continuation of

the domestic decorative tradition for use in humble burial chambers.Wall

painting was not considered high art in either Greece or Rome. Sculpture and

panel painting, usually consisting of tempera or encaustic painting on wooden

panels, were considered more prestigious art forms.

A large number of Fayum

mummy portraits, bust portraits on wood added to the outside of mummies by the

Romanized middle class, exist in Roman Egypt. Although these are in some ways

distinctively local, they are also broadly representative of the Roman style of

painted portraits.

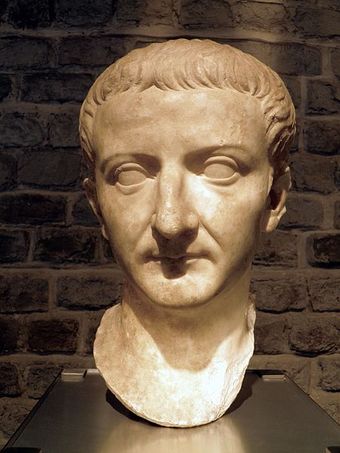

Roman portraiture during the Republic is identified by its considerable realism, known as veristic portraiture. Verism refers to a hyper-realistic portrayal of the subject’s facial characteristics. The style originated from Hellenistic Greece; however, its use in Republican Rome and survival throughout much of the Republic is due to Roman values, customs, and political life. As with other forms of Roman art, Roman portraiture borrowed certain details from Greek art, but adapted these to their own needs. Veristic images often show their male subject with receding hairlines, deep winkles, and even with warts. While the face of the portrait was often shown with incredible detail and likeness, the body of the subject would be idealized, and did not seem to correspond to the age shown in the face .

Bust of an Old Man

Veristic portraiture of an Old Man. Verism refers to a hyper-realistic portrayal of the subject’s facial characteristics.

Portrait

sculpture during the period utilized youthful and classical proportions,