16.1: Goals of Economic Policy

16.1.1: The Goals of Economic Policy

There are four major goals of economic policy: stable markets, economic prosperity, business development and protecting employment.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast the policy tools used by governments to achieve economic growth

Key Points

- Sometimes other objectives, like military spending or nationalization are important.

- To achieve these goals, governments use policy tools which are under the control of the government.

- Government and central banks are limited in the number of goals they can achieve in the short term.

Key Terms

- nationalization

-

Nationalization (British English spelling nationalisation) is the process of taking a private industry or private assets into public ownership by a national government or state.

- business development

-

A subset of the fields of Business and commerce, business development comprises a number of tasks and processes generally aiming at developing and implementing growth opportunities.

- economic prosperity

-

Economic prosperity is the state of flourishing, thriving, good fortune in regards to wealth.

Economic policy refers to the actions that governments take in the economic field. It covers the systems for setting interest rates and government budget as well as the labor market, national ownership, and many other areas of government interventions into the economy.

Policy is generally directed to achieve four major goals: stabilizing markets, promoting economic prosperity, ensuring business development, and promoting employment. Sometimes other objectives, like military spending or nationalization, are important.

Economic Growth

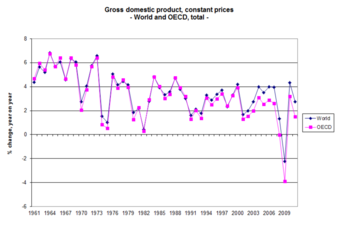

One of the major goals of economic policy is to promote economic growth. How growth is measured though is another question. The above image Rate of change of Gross domestic product, world and OECD, since 1961, is one representation of economic growth.

To achieve these goals, governments use policy tools which are under the control of the government. These generally include the interest rate and money supply, tax and government spending, tariffs, exchange rates, labor market regulations, and many other aspects of government.

Selecting Tools and Goals

Government and central banks are limited in the number of goals they can achieve in the short term. For instance, there may be pressure on the government to reduce inflation, reduce unemployment, and reduce interest rates while maintaining currency stability. If all of these are selected as goals for the short term, then policy is likely to be incoherent, because a normal consequence of reducing inflation and maintaining currency stability is increasing unemployment and increasing interest rates.

For much of the 20th century, governments adopted discretionary policies such as demand management that were designed to correct the business cycle. These typically used fiscal and monetary policy to adjust inflation, output and unemployment.

However, following the stagflation of the 1970s, policymakers began to be attracted to policy rules.

A discretionary policy is supported because it allows policymakers to respond quickly to events. However, discretionary policy can be subject to dynamic inconsistency: a government may say it intends to raise interest rates indefinitely to bring inflation under control, but then relax its stance later. This makes policy non-credible and ultimately ineffective.

A rule-based policy can be more credible, because it is more transparent and easier to anticipate. Examples of rule-based policies are fixed exchange rates, interest rate rules, the stability and growth pact and the Golden Rule. Some policy rules can be imposed by external bodies, for instance, the Exchange Rate Mechanism for currency.

A compromise between strict discretionary and strict rule-based policy is to grant discretionary power to an independent body. For instance, the Federal Reserve Bank, European Central Bank, Bank of England and Reserve Bank of Australia all set interest rates without government interference, but do not adopt rules.

Another type of non-discretionary policy is a set of policies which are imposed by an international body. This can occur (for example) as a result of intervention by the International Monetary Fund.

16.1.2: Fours Schools of Economic Thought: Classical, Marxian, Keynesian, and the Chicago School.

Mainstream modern economics can be broken down into four schools of economic thought: classical, Marxian, Keynesian, and the Chicago School.

Learning Objective

Apply the four main schools of modern economic thought.

Key Points

- Classical economics focuses on the tendency of markets to move towards equilibrium and on objective theories of value.

- As the original form of mainstream economics of the 18th and 19th centuries, classical economics served as the basis for many other schools of economic thought, including neoclassical economics.

- Marxism focuses on the labor theory of value and what Marx considered to be the exploitation of labor by capital.

- Keynesian economics derives from John Maynard Keynes, in particular his book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936), which ushered in contemporary macroeconomics as a distinct field.

- The Chicago School of economics is best known for its free market advocacy and monetarist ideas.

Key Terms

- mainstream economics

-

Mainstream economics is a term used to refer to widely-accepted economics as it is taught across prominent universities, and in contrast to heterodox economics.

- School of thought

-

A school of thought is a collection or group of people who share common characteristics of opinion or outlook regarding a philosophy, discipline, belief, social movement, cultural movement, or art movement.

Throughout the history of economic theory, several methods for approaching the topic are noteworthy enough, and different enough from one another, to be distinguished as particular ‘schools of economic thought. ‘ While economists do not always fit into particular schools, especially in modern times, classifying economists into a particular school of thought is common.

Mainstream modern economics can be broken down into four schools of economic thought:

Classical economics, also called classical political economy, was the original form of mainstream economics in the 18th and 19th centuries. Classical economics focuses on both the tendency of markets to move towards equilibrium and on objective theories of value. Neo-classical economics derives from this school, but differs because it is utilitarian in its value theory and because it uses marginal theory as the basis of its models and equations. Anders Chydenius (1729–1803) was the leading classical liberal of Nordic history. A Finnish priest and member of parliament, he published a book called The National Gain in 1765, in which he proposed ideas about the freedom of trade and industry, explored the relationship between the economy and society, and laid out the principles of liberalism. All of this happened eleven years before Adam Smith published a similar and more comprehensive book, The Wealth of Nations. According to Chydenius, democracy, equality and a respect for human rights formed the only path towards progress and happiness for the whole of society.

Marxian economics descends directly from the work of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. This school focuses on the labor theory of value and what Marx considers to be the exploitation of labor by capital. Thus, in this school of economic thought, the labor theory of value is a method for measuring the degree to which labor is exploited in a capitalist society, rather than simply a method for calculating price.

Marxism

The Marxist school of economic thought comes from the work of German economist Karl Marx.

Keynesian economics derives from John Maynard Keynes, and in particular his book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936), which ushered in contemporary macroeconomics as a distinct field. The book analyzed the determinants of national income, in the short run, during a period of time when prices are relatively inflexible. Keynes attempted to explain, in broad theoretical detail, why high labor-market unemployment might not be self-correcting due to low “effective demand,” and why neither price flexibility nor monetary policy could be counted on to remedy the situation. Because of its impact on economic analysis, this book is often called “revolutionary. “

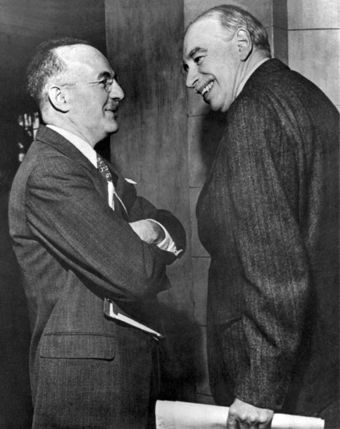

Keynesian Economics

John Maynard Keynes (right), was a key theorist in economics.

A final school of economic thought, the Chicago School of economics, is best known for its free market advocacy and monetarist ideas. According to Milton Friedman and monetarists, market economies are inherently stable so long as the money supply does not greatly expand or contract. Ben Bernanke, current Chairman of the Federal Reserve, is among the significant public economists today that generally accepts Friedman’s analysis of the causes of the Great Depression.

16.2: The History of Economic Policy

16.2.1: The Nineteenth Century

Associated with industrialism and capitalism, the 19th century looms large in the history of economic policy and economic thought.

Learning Objective

Summarize the main currents of economic thought in the 19th-century

Key Points

- The beginning of the 19th century was dominated by classical economists, who concerned themselves with the transformation brought by the Industrial Revolution including rural depopulation, precariousness, poverty, and apparition of a working class.

- Karl Marx’s combination of political theory, represented in the Communist Manifesto and the dialectic theory of history inspired by Friedrich Hegel, provided a revolutionary critique of capitalism as he saw it in the 19th century.

- In the 1860’s, a revolution took place in economics.

- This current of thought was not united. There were three main schools working independently.

Key Terms

- industrialization

-

A process of social and economic change whereby a human society is transformed from a pre-industrial to an industrial state

- capitalism

-

A socio-economic system based on private property rights, including the private ownership of resources or capital, with economic decisions made largely through the operation of a market unregulated by the state.

As the century most associated with industrialization and capitalism in the West, the 19th century looms large in the history of economic policy and economic thought.

The beginning of the 19th century was dominated by “classical economists,” a group not actually referred to by this name until Karl Marx. One unifying part of their theories was the labor theory of value, contrasting to value deriving from a general equilibrium of supply and demand. These economists had seen the first economic and social transformation brought by the Industrial Revolution: rural depopulation, precariousness, poverty, and apparition of a working class. They wondered about the population growth because the demographic transition had begun in Great Britain at that time. They also asked many fundamental questions about the source of value, the causes of economic growth, and the role of money in the economy. They supported a free-market economy. They argued that it was a natural system based upon freedom and property. However, these economists were divided and did not make up a unified group of thought.

A notable current within classical economics was the under-consumption theory, as advanced by the Birmingham School and Malthus in the early 19th century. The theory argued for government action to mitigate unemployment and economic downturns. It was an intellectual predecessor of what later became Keynesian economics in the 1930’s.

Just as the term “mercantilism” had been coined and popularized by its critics like Adam Smith, so was the term “capitalism” or Kapitalismus used by its dissidents, primarily Karl Marx. Karl Marx (1818–1883) was, and in many ways still remains, the pre-eminent socialist economist. His combination of political theory represented in the Communist Manifesto and the dialectic theory of history inspired by Friedrich Hegel provided a revolutionary critique of capitalism as he saw it in the 19th century. The socialist movement that he joined had emerged in response to the conditions of people in the new industrial era and the classical economics which accompanied it. He wrote his magnum opus Das Kapital at the British Museum’s library .

Das Kapital

Karl Marx’s definition and popularizing of the term “capitalism” or Kapitalismus, as defined in “Das Kapital,” first published in 1867, remains one of the most influential works on the subject to this day.

In the 1860’s, a revolution took place in economics. The new ideas were that of the Marginalist school. Writing simultaneously and independently, a Frenchman (Léon Walras), an Austrian (Carl Menger), and an Englishman (Stanley Jevons) were developing the theory that had some antecedents. Instead of the price of a good or service reflecting the labor that has produced it, it reflected the marginal usefulness (utility) of the last purchase. This meant that in equilibrium, people’s preferences determined prices including, indirectly, the price of labor.

This current of thought was not united. There were three main schools working independently. The Lausanne school, whose two main representatives were Walras and Vilfredo Pareto, developed the theories of general equilibrium and optimality. The main written work of this school was Walras’ Elements of Pure Economics. The Cambridge school appeared with Jevons’ Theory of Political Economy in 1871. This English school developed the theories of the partial equilibrium and insisted on markets’ failures. The main representatives were Alfred Marshall, Stanley Jevons, and Arthur Pigou. The Vienna school was made up of Austrian economists Menger, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, and Friedrich von Wieser. They developed the theory of capital and tried to explain the presence of economic crises. It appeared in 1871 with Menger’s Principles of Economics.

16.2.2: The Progressive Era

The Progressive Era was one of general prosperity after the Panic of 1893; a severe depression that ended in 1897.

Learning Objective

Discuss the economic policies of the Progressive Era in the United States.

Key Points

- The weakened economy and persistent federal deficits led to changes in fiscal policy including the imposition of federal income taxes on businesses and individuals and the creation of the Federal Reserve System.

- The progressives voiced the need for government regulation of business practices to ensure competition and free enterprise.

- By the turn of the century, a middle class had developed that was leery of both the business elite and the radical political movements of farmers and laborers in the Midwest and West.

Key Terms

- tariff

-

a system of government-imposed duties levied on imported or exported goods; a list of such duties, or the duties themselves

- laissez-faire

-

an economic environment in which transactions between private parties are free from tariffs, government subsidies, and enforced monopolies with only enough government regulations sufficient to protect property rights against theft and aggression.

- fiscal policy

-

Government policy that attempts to influence the direction of the economy through changes in government spending or taxes.

The Progressive Era was one of general prosperity after the Panic of 1893; a severe depression that ended in 1897. The Panic of 1907 was short and mainly affected financiers. However, Campbell (2005) stresses the weak points of the economy in 1907–1914, linking them to public demands for more progressive interventions. The Panic of 1907 was followed by a small decline in real wages and increased unemployment, with both trends continuing until World War I. This resulted in stress on public finance and impacted the Wilson administration’s policies. The weakened economy and persistent federal deficits led to changes in fiscal policy, including the imposition of federal income taxes on businesses and individuals and the creation of the Federal Reserve System. Government agencies were also transformed in an effort to improve administrative efficiency.

In the Gilded Age (late 19th century) the parties were reluctant to involve the federal government too heavily in the private sector, except in the area of railroads and tariffs. In general, they accepted the concept of laissez-faire, which was doctrine opposing government interference in the economy except to maintain law and order. This attitude started to change during the depression of the 1890’s when small business, farm, and labor movements began asking the government to intercede on their behalf.

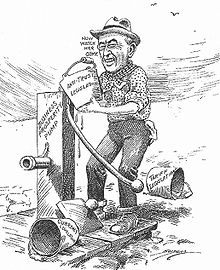

By the turn of the century, a middle class had developed that was leery of both the business elite and the radical political movements of farmers and laborers in the Midwest and West. The progressives voiced the need for government regulation of business practices to ensure competition and free enterprise. Congress enacted a law regulating railroads in 1887 (the Interstate Commerce Act) and one preventing large firms from controlling a single industry in 1890 (the Sherman Antitrust Act). However, these laws were not rigorously enforced until 1900 to 1920, when Republican President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909), Democratic President Woodrow Wilson (1913–1921), and others sympathetic to the views of the Progressives came to power . Many of today’s U.S. regulatory agencies were created during these years including the Interstate Commerce Commission and the Federal Trade Commission. Muckrakers were journalists who encouraged readers to demand more regulation of business. Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle (1906) was influential and persuaded America about the supposed horrors of the Chicago Union Stock Yards (though Sinclair himself never visited the site); a giant complex of meat processing that developed in the 1870’s. The federal government responded to Sinclair’s book and The Neill-Reynolds Report with the new regulatory Food and Drug Administration. Ida M. Tarbell wrote a series of articles against Standard Oil, which was perceived to be a monopoly. This affected both the government and the public reformers. Attacks by Tarbell and others helped pave the way for public acceptance of the breakup of the company by the Supreme Court in 1911.

Anti-Trust Legislation

President Wilson uses tariff, currency, and anti-trust laws to prime the pump and get the economy working.

When Democrat Woodrow Wilson was elected President with a Democratic Congress in 1912, he implemented a series of progressive policies in economics. In 1913, the 16th Amendment was ratified and a small income tax was imposed on high incomes. The Democrats lowered tariffs with the Underwood Tariff in 1913, although its effects were overwhelmed by the changes in trade caused by the World War that broke out in 1914. Wilson proved especially effective in mobilizing public opinion behind tariff changes by denouncing corporate lobbyists, addressing Congress in person in highly dramatic fashion, and staging an elaborate ceremony when he signed the bill into law. Wilson helped end the long battles over the trusts with the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914. He managed to convince lawmakers on the issues of money and banking by the creation in 1913 of the Federal Reserve System, a complex business-government partnership that to this day dominates the financial world.

In 1913, Henry Ford adopted the moving assembly line, with each worker doing one simple task in the production of automobiles. Taking his cue from developments during the progressive era , Ford offered a very generous wage—$5 a day—to his (male) workers. He argued that a mass production enterprise could not survive if average workers could not buy the goods.

16.2.3: The Great Depression and the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic programs enacted in the United States between 1933 and 1936 in response to the Great Depression.

Learning Objective

Describe the Great Depression, the Roosevelt administration’s economic response to it in the New Deal, and its lasting effects

Key Points

- The programs focused on what historians call the “3 Rs”: Relief, Recovery, and Reform.

- The New Deal produced a political realignment.

- By 1942–43 the Conservative Coalition had shut down relief programs such as the WPA and CCC and blocked major liberal proposals.

Key Terms

- economic depression

-

In economics, a depression is a sustained, long-term downturn in economic activity in one or more economies. It is a more severe downturn than a recession, which is seen by some economists as part of the modern business cycle.

- political realignment

-

Realigning election (often called a critical election or political realignment) is a term from political science and political history describing a dramatic change in the political system.

- regulation

-

A law or administrative rule, issued by an organization, used to guide or prescribe the conduct of members of that organization; can specifically refer to acts in which a government or state body limits the behavior of businesses.

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. It was the longest, most widespread, and deepest depression of the 20th century. In the 21st century, the Great Depression is commonly used as an example of how far the world’s economy can decline. The depression originated in the U.S., after the fall in stock prices that began around September 4, 1929, and became worldwide news with the stock market crash of October 29, 1929 (known as Black Tuesday).

Cities all around the world were hit hard, especially those dependent on heavy industry. Construction was virtually halted in many countries. Farming and rural areas suffered as crop prices fell by approximately 60%. Facing plummeting demand with few alternate sources of jobs, areas dependent on primary sector industries such as cash cropping, mining, and logging suffered the most. Some economies started to recover by the mid-1930s. In many countries, the negative effects of the Great Depression lasted until the end of World War II.

Great Depression in Unemployment

Unemployment rate in the US 1910–1960, with the years of the Great Depression (1929–1939) highlighted; accurate data begins in 1939.

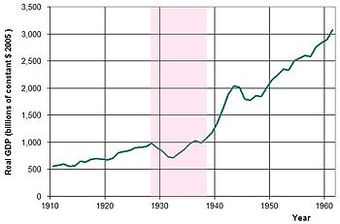

Great Depression in GDP

USA annual real GDP from 1910 to 1960, with the years of the Great Depression (1929–1939) highlighted.

The New Deal was a series of economic programs enacted in the United States between 1933 and 1936. The programs were in response to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call the “3 Rs”: Relief, Recovery, and Reform. That is, Relief for the unemployed and poor; Recovery of the economy to normal levels; and Reform of the financial system to prevent a repeat depression.

The New Deal produced a political realignment, making the Democratic Party the majority (as well as the party that held the White House for seven out of nine Presidential terms from 1933 to 1969). Its basis was liberal ideas, the white South, traditional Democrats, big city machines, and the newly empowered labor unions and ethnic minorities. The Republicans were split, with conservatives opposing the entire New Deal as an enemy of business and growth, and liberals accepting some of it and promising to make it more efficient. The realignment crystallized into the New Deal Coalition that dominated most presidential elections into the 1960s, while the opposing Conservative Coalition largely controlled Congress from 1937 to 1963.

From 1934 to 1938, Roosevelt was assisted in his endeavors by a “pro-spender” majority in Congress. Many historians distinguish a “First New Deal” (1933–34) and a “Second New Deal” (1935–38), with the second one being more liberal and more controversial. It included a national work program, the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which made the federal government by far the largest single employer in the nation. The “First New Deal” (1933–34) dealt with diverse groups, from banking and railroads to industry and farming, all of which demanded help for economic survival. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration, for instance, provided $500 million for relief operations by states and cities, while the short-lived CWA (Civil Works Administration) gave localities money to operate make-work projects in 1933-34.

The “Second New Deal” in 1935–38 included the Wagner Act to promote labor unions, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) relief program, the Social Security Act, and new programs to aid tenant farmers and migrant workers. The final major items of New Deal legislation were the creation of the United States Housing Authority and Farm Security Administration, both in 1937, and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which set maximum hours and minimum wages for most categories of workers.

The economic downturn of 1937–38, and the bitter split between the AFL and CIO labor unions, led to major Republican gains in Congress in 1938. Conservative Republicans and Democrats in Congress joined in the informal Conservative Coalition. By 1942–43 they shut down relief programs such as the WPA and CCC and blocked major liberal proposals. Roosevelt himself turned his attention to the war effort, and won reelection in 1940 and 1944. The Supreme Court declared the National Recovery Administration (NRA) and the first version of the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) unconstitutional, although the AAA was rewritten and then upheld. As the first Republican president elected after FDR, Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953–61) left the New Deal largely intact, even expanding it in some areas. In the 1960s, Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society used the New Deal as inspiration for a dramatic expansion of liberal programs, which Republican Richard M. Nixon generally retained. After 1974, however, the call for deregulation of the economy gained bipartisan support. The New Deal regulation of banking (Glass–Steagall Act) was suspended in the 1990s. Many New Deal programs remain active, with some still operating under the original names, including the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC), the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). The largest programs still in existence today are the Social Security System and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

16.2.4: Social Regulation

Social policy refers to guidelines, principles, legislation and activities that affect the living conditions conducive to human welfare.

Learning Objective

Summarize the broad periods of regulation and deregulation in American history

Key Points

- Social policy aims to improve human welfare and to meet human needs for education, health, housing, and social security.

- Important areas of social policy are the welfare state, social security, unemployment insurance, environmental policy, pensions, health care, social housing, social care, child protection, social exclusion, education policy, crime, and criminal justice.

- With regard to economic policy, regulations may include central planning of the economy, remedying market failure, enriching well-connected firms, or benefiting politicians.

- Informal social control is often not sufficient in a large society in which an individual can choose to ignore the sanctions of an individual group, leading to the use of formal, usually government control.

- With regard to economic policy, regulations may include central planning of the economy, remedying market failure, enriching well-connected firms, or benefiting politicians.

Key Terms

- laissez-faire

-

an economic environment in which transactions between private parties are free from tariffs, government subsidies, and enforced monopolies with only enough government regulations sufficient to protect property rights against theft and aggression.

- social policy

-

Social policy primarily refers to guidelines, principles, legislation, and activities that affect the living conditions conducive to human welfare.

Example

- The Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy at Harvard University describes it as “public policy and practice in the areas of health care, human services, criminal justice, inequality, education, and labor. “

Social Policy

Social policy primarily refers to guidelines, principles, legislation and activities that affect the living conditions conducive to human welfare. The Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy at Harvard University describes it as “public policy and practice in the areas of health care, human services, criminal justice, inequality, education, and labor. “

Types of Social Policy

Social policy aims to improve human welfare and to meet human needs for education, health, housing and social security. Important areas of social policy are the welfare state, social security, unemployment insurance, environmental policy, pensions, health care, social housing, social care, child protection, social exclusion, education policy, crime, and criminal justice.

The term ‘social policy’ can also refer to policies which govern human behavior. In the United States, the term ‘social policy’ may be used to refer to abortion and the regulation of its practice, euthanasia, homosexuality, the rules surrounding issues of marriage, divorce, adoption, the legal status of recreational drugs, and the legal status of prostitution.

Economic Policy

With regard to economic policy, regulations may include central planning of the economy, remedying market failure, enriching well-connected firms, or benefiting politicians. In the U.S., throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the government engaged in substantial regulation of the economy. In the 18th century, the production and distribution of goods were regulated by British government ministries over the American Colonies. Subsidies were granted to agriculture and tariffs were imposed, sparking the American Revolution.

The United States government maintained high tariffs throughout the 19th century and into the 20th century, until the Reciprocal Trade Agreement was passed in 1934 under the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration. Other forms of regulation and deregulation came in waves: the deregulation of big business in the Gilded Age, which led to President Theodore Roosevelt’s trust busting from 1901 to 1909; more deregulation and Laissez-Faire economics in the 1920’s, which was followed by the Great Depression and intense governmental regulation under Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal; and President Ronald Reagan’s deregulation of business in the 1980s.

The Seal of the SEC

Seal of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

16.2.5: Deregulation

Deregulation is the act or process of removing or reducing state regulations.

Learning Objective

Analyze arguments in favor of deregulation

Key Points

- The stated rationale for deregulation is often that fewer and simpler regulations will lead to a raised level of competitiveness, therefore higher productivity, more efficiency and lower prices overall.

- Opposition to deregulation usually involves apprehension regarding environmental pollution and environmental quality standards (these issues are protected against by certain regulations, such as those that limit the use of hazardous materials), financial uncertainty, and constraining monopolies.

- Regulatory reform is a parallel development alongside deregulation.

- Deregulation can be distinguished from privatization, because privatization involves taking state-owned service providers into the private sector.

Key Terms

- privatization

-

The transfer of a company or organization from government to private ownership and control.

- deregulation

-

The process of removing constraints, especially government-imposed economic regulations.

- regulation

-

A law or administrative rule, issued by an organization, used to guide or prescribe the conduct of members of that organization; can specifically refer to acts in which a government or state body limits the behavior of businesses.

Deregulation is the act or process of removing or reducing state regulations. It is therefore the opposite of regulation, which is the process in which the government regulates certain activities. Laissez-faire is an example of a deregulated economic environment in which transactions between private parties are free from government restrictions, tariffs, and subsidies, with only enough regulations to protect property rights. The phrase laissez-faire is French and literally means “let [them] do,” broadly implying “let it be” or “leave it alone. “

The rationale for deregulation, as it is often phrased, is that fewer and simpler regulations will lead to a raised level of competitiveness between businesses, which itself will generate higher productivity, higher efficiency and lower prices. The Financial Times Lexicon states that deregulation, in the sense of a substantial easing of government restrictions on industry, is normally justified in order to promote competition.

Opposition to deregulation usually stems from concerns regarding environmental pollution and environmental quality standards, both of which are protected against by certain types of regulations, such as those that limit the ability of businesses to use hazardous materials. Opposition has also stemmed from fears that a free market, without protective regulations, would become financially unstable or controlled by monopolies.

Regulatory reform is a parallel development alongside deregulation. Regulatory reform refers to efforts, by the government, to review regulations with a view towards minimizing them, simplifying them, and making them more cost effective. Such efforts, given impetus by the Regulatory Flexibility Act of 1980, are embodied in the U.S. Office of Management and Budget’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, and the United Kingdom’s Better Regulation Commission. Cost-benefit analysis is frequently used in such reviews. Another catalyst of reform has been regulatory innovations (such as emissions trading), usually suggested by economists..

Deregulation can be distinguished from privatization, because privatization involves moving state-owned service providers into the private sector.

History

Many industries in the United States became regulated by the federal government in the late 19th and early 20th century. Entry to some markets was restricted to stimulate and protect private companies as they made initial investments into an infrastructure that provided essential public services, such as water, electric and communications utilities. Because the entry of competitors was highly restricted, monopoly situations were created. The government responded by instituting more regulations, this time price and economic controls aimed at protecting the public from these monopolies. Other forms of regulation were motivated by what was seen as the corporate abuse of the public interest by businesses that already existed. This occurred with the railroad industry following the era of the so-called “robber barons”. In the first instance, as markets matured to a point where several providers could be financially viable offering similar services, prices determined by that ensuing competition were seen as more economically efficient than those set by the regulatory process. Under these conditions, deregulation became attractive.

One phenomenon that encouraged deregulation was the fact that regulated industries often controlled the government regulatory agencies and used them to serve the industries’ interests. Even when regulatory bodies started out functioning independently, a process known as regulatory capture often saw industry interests come to dominate those of the consumer. A similar pattern has been observed within the deregulation process itself, which is often effectively controlled by the regulated industries through lobbying the legislative process. Such political forces, however, exist in many other forms for other special interest groups.

After a several decade hiatus, deregulation gained momentum in the 1970s, influenced by research at the University of Chicago and the theories of Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich von Hayek, and Milton Friedman, among others . Two leading ‘think tanks’ in Washington, the Brookings Institution and the American Enterprise Institute, were also active, holding seminars and publishing studies that advocated deregulatory initiatives throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Alfred E. Kahn played an unusual role, because he published as an academic and also participated in the Carter Administration’s efforts to deregulate transportation.

Friedrich Von Hayek

Austrian economist Friedrich von Hayek, along with University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman are two classic liberal economists attributed with the return of laissez-faire economics and deregulation.

The deregulation movement of the late 20th century had substantial economic effects and engendered substantial controversy.

16.3: Economic Policy

16.3.1: Monetary Policy

Monetary policy is the process by which the monetary authority of a country controls the supply of money.

Learning Objective

Describe how central banking authorities use monetary policy to achieve the twin economic goals of relatively stable prices and low unemployment

Key Points

- Expansionary policy is traditionally used to try to combat unemployment in a recession by lowering interest rates in the hope that easy credit will entice businesses into expanding.

- Contractionary policy is intended to slow inflation in hopes of avoiding the resulting distortions and deterioration of asset values.

- Monetary policy differs from fiscal policy, which refers to taxation, government spending, and associated borrowing.

- The primary tool of monetary policy is open market operations. This entails managing the quantity of money in circulation through the buying and selling of various financial instruments, such as treasury bills, company bonds, or foreign currencies.

Key Terms

- Expansionary policy

-

Expansionary policy increases the total supply of money in the economy more rapidly than usual.

- monetary policy

-

Monetary policy is the process by which the monetary authority of a country controls the supply of money, often targeting a rate of interest for the purpose of promoting economic growth and stability.

- Contractionary policy

-

Contractionary policy expands the money supply more slowly than usual or even shrinks it.

Monetary Policy

Monetary policy is the process by which the monetary authority of a country controls the supply of money, often targeting a rate of interest for the purpose of promoting economic growth and stability. The official goals usually include relatively stable prices and low unemployment. Monetary theory provides insight into how to craft optimal monetary policy. It is referred to as either being expansionary or contractionary, where an expansionary policy increases the total supply of money in the economy more rapidly than usual, and contractionary policy expands the money supply more slowly than usual or even shrinks it. Expansionary policy is traditionally used to try to combat unemployment in a recession by lowering interest rates in the hope that easy credit will entice businesses into expanding. Contractionary policy is intended to slow inflation in hopes of avoiding the resulting distortions and deterioration of asset values.

Monetary policy differs from fiscal policy, which refers to taxation, government spending, and associated borrowing.

Monetary policy rests on the relationship between the rates of interest in an economy, that is, the price at which money can be borrowed, and the total supply of money. Monetary policy uses a variety of tools to control one or both of these, to influence outcomes like economic growth, inflation, exchange rates with other currencies and unemployment. Where currency is under a monopoly of issuance, or where there is a regulated system of issuing currency through banks which are tied to a central bank, the monetary authority has the ability to alter the money supply and thus influence the interest rate to achieve policy goals. The beginning of monetary policy as such comes from the late 19th century, where it was used to maintain the gold standard.

Monetary policies are described as follows: accommodative, if the interest rate set by the central monetary authority is intended to create economic growth; neutral, if it is intended neither to create growth nor combat inflation; or tight if intended to reduce inflation.

There are several monetary policy tools available to achieve these ends: increasing interest rates by fiat; reducing the monetary base; and increasing reserve requirements with the effect of contracting the money supply; and, if reversed, expand the money supply.

Within almost all modern nations, special institutions, central banks, (the Federal Reserve System in the United States) have the task of executing the monetary policy and often independently of the executive .

The Federal Reserve Board Building

The Federal Reserve Board Building in Washington D. C.

The primary tool of monetary policy is open market operations. This entails managing the quantity of money in circulation through the buying and selling of various financial instruments, such as treasury bills, company bonds, or foreign currencies. All of these purchases or sales result in more or less base currency entering or leaving market circulation.

Usually, the short term goal of open market operations is to achieve a specific short term interest rate target. In other instances, monetary policy might instead entail the targeting of a specific exchange rate relative to some foreign currency or else relative to gold. For example, in the case of the USA the Federal Reserve targets the federal funds rate, the rate at which member banks lend to one another overnight; however, the monetary policy of China is to target the exchange rate between the Chinese renminbi and a basket of foreign currencies.

The other primary means of conducting monetary policy include:

- Discount window lending (lender of last resort)

- Fractional deposit lending (changes in the reserve requirement)

- Moral suasion (cajoling certain market players to achieve specified outcomes)

- “Open mouth operations” (talking monetary policy with the market).

16.3.2: Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy is the use of government revenue collection or taxation, and expenditure (spending) to influence the economy.

Learning Objective

Review the United States’ stances of fiscal policy, methods of funding, and policies regarding borrowing

Key Points

- There are three main stances of fiscal policy: neutral fiscal policy, expansionary fiscal policy, and contractionary fiscal policy.

- Governments can use a budget surplus to do two things: to slow the pace of strong economic growth and to stabilize prices when inflation is too high.

- However, economists debate the effectiveness of fiscal stimulus. The argument mostly centers on crowding out.

- In the classical view, the expansionary fiscal policy also decreases net exports, which has a mitigating effect on national output and income.

Key Terms

- Neoclassical Economists

-

Neoclassical economists generally emphasize crowding out; when government borrowing leads to higher interest rates that may offset the stimulative impact of spending.

- fiscal policy

-

In economics and political science, fiscal policy is the use of government revenue collection or taxation, and expenditure (spending) to influence the economy.

- Keynesian Economics

-

Keynesian economics suggests that increasing government spending and decreasing tax rates are the best ways to stimulate aggregate demand, and only to decrease spending & increase taxes after the economic boom begins.

Fiscal Policy

In economics and political science, fiscal policy is the use of government revenue collection or taxation, and expenditure (spending) to influence the economy. Changes in the level and composition of taxation and government spending can impact the following variables in the economy: aggregate demand and the level of economic activity; the pattern of resource allocation; and the distribution of income.

Stances of Fiscal Policy

There are three main stances of fiscal policy:

- Neutral fiscal policy is usually undertaken when an economy is in equilibrium. Government spending is fully funded by tax revenue and overall the budget outcome has a neutral effect on the level of economic activity.

- Expansionary fiscal policy involves government spending exceeding tax revenue, and is usually undertaken during recessions.

- Contractionary fiscal policy occurs when government spending is lower than tax revenue, and is usually undertaken to pay down government debt.

However, these definitions can be misleading as, even with no changes in spending or tax laws at all, cyclic fluctuations of the economy cause cyclic fluctuations of tax revenues and of some types of government spending, altering the deficit situation; these are not considered to be policy changes. Thus, for example, a government budget that is balanced over the course of the business cycle is considered to represent a neutral fiscal policy stance.

Methods of Funding

Governments spend money on a wide variety of things, from the military and police to services like education and healthcare, as well as transfer payments such as welfare benefits. This expenditure can be funded in a number of different ways: taxation, printing money, borrowing money from the population or from abroad, consumption of fiscal reserves, or sale of fixed assets (land).

Borrowing

A fiscal deficit is often funded by issuing bonds. These pay interest, either for a fixed period or indefinitely. If the interest and capital requirements are too large, a nation may default on its debts, usually to foreign creditors, while public debt or borrowing refers to the government borrowing from the public.

Economic Effects of Fiscal Policy

Governments use fiscal policy to influence the level of aggregate demand in the economy, in an effort to achieve economic objectives of price stability, full employment, and economic growth. One school of fiscal policy developed by John Maynard Keynes suggests that increasing government spending and decreasing tax rates are the best ways to stimulate aggregate demand, and only to decrease spending & increase taxes after the economic boom begins. Keynesian Economics argues this method be used in times of recession or low economic activity as an essential tool for building the framework for strong economic growth and working towards full employment. In theory, the resulting deficits would be paid for by an expanded economy during the boom that would follow; this was the reasoning behind the New Deal.

John Maynard Keynes and Harry Dexter White

Keynes (right) was the father and founder of Keynesian economics.

Governments can use a budget surplus to do two things: to slow the pace of strong economic growth and to stabilize prices when inflation is too high. Keynesian theory posits that removing spending from the economy will reduce levels of aggregate demand and contract the economy, thus stabilizing prices.

However, economists debate the effectiveness of fiscal stimulus. The argument mostly centers on crowding out; whether government borrowing leads to higher interest rates that may offset the stimulative impact of spending. When the government runs a budget deficit, funds will need to come from public borrowing (government bonds), overseas borrowing, or monetizing the debt. When governments fund a deficit with the issuing of government bonds, interest rates can increase across the market, because government borrowing creates higher demand for credit in the financial markets. This causes a lower aggregate demand for goods and services, contrary to the objective of a fiscal stimulus. Neoclassical economists generally emphasize crowding out while Keynesians argue that fiscal policy can still be effective especially in a liquidity trap where, they argue, crowding out is minimal.

In the classical view, the expansionary fiscal policy also decreases net exports, which has a mitigating effect on national output and income. When government borrowing increases interest rates it attracts foreign capital from foreign investors. This is because, all other things being equal, the bonds issued from a country executing expansionary fiscal policy now offer a higher rate of return. To purchase bonds originating from a certain country, foreign investors must obtain that country’s currency. Therefore, when foreign capital flows into the country undergoing fiscal expansion, demand for that country’s currency increases. The increased demand causes that country’s currency to appreciate. Once the currency appreciates, goods originating from that country now cost more to foreigners than they did before and foreign goods now cost less than they did before. Consequently, exports decrease and imports increase.

16.3.3: Income Security Policy

Fiscal policy is considered to be any change the government makes to the national budget in order to influence a nation’s economy.

Learning Objective

Analyze the transformation of American fiscal policy in the years of the Great Depression and World War II

Key Points

- The Great Depression showed the American population that there was a growing need for the government to manage economic affairs. The size of the federal government began rapidly expanding in the 1930s, growing from 553,000 paid civilian employees in the late 1920s to 953,891 employees in 1939.

- FDR was important because he implicated the New Deal, a program that would offer relief, recovery, and reform to the American nation. In terms of relief, new organizations (such as the Works Progress Administration) saved many U.S. lives.

- In 1971, at Bretton Woods, the U.S. went off the gold standard, allowing the dollar to float. Shortly after that, OPEC pegged the price of oil to gold rather than the dollar. The 70s were marked by oil shocks, recessions, and inflation in the U.S.

- Fixed income refers to any type of investment under which the borrower/issuer is obliged to make payments of a fixed amount on a fixed schedule: for example, if the borrower has to pay interest at a fixed rate once a year, and to repay the principal amount on maturity.

- Fixed-income securities can be contrasted with equity securities, often referred to as stocks and shares, that create no obligation to pay dividends or any other form of income.

- Governments issue government bonds in their own currency and sovereign bonds in foreign currencies. Local governments issue municipal bonds to finance themselves. Debt issued by government-backed agencies is called an agency bond.

Key Terms

- fiscal

-

Related to the treasury of a country, company, region, or city, particularly to government spending and revenue.

- fixed income

-

Fixed income refers to any type of investment under which the borrower/issuer is obliged to make payments of a fixed amount on a fixed schedule: for example, if the borrower has to pay interest at a fixed rate once a year, and to repay the principal amount on maturity.

Background

Any changes the government makes to the national budget in order to influence a nation’s economy is considered fiscal policy. The approach to economic policy in the United States was rather laissez-faire until the Great Depression. The government tried to stay away from economic matters as much as possible and hoped that a balanced budget would be maintained.

Fixed income refers to any type of investment under which the borrower/issuer is obliged to make payments of a fixed amount on a fixed schedule: for example, if the borrower has to pay interest at a fixed rate once a year, and to repay the principal amount on maturity. Fixed-income securities can be contrasted with equity securities, often referred to as stocks and shares, that create no obligation to pay dividends or any other form of income. In order for a company to grow its business, it often must raise money: to finance an acquisition, buy equipment or land or invest in new product development. Governments issue government bonds in their own currency and sovereign bonds in foreign currencies. Local governments issue municipal bonds to finance themselves. Debt issued by government-backed agencies is called an agency bond.

The Great Depression

The Great Depression struck countries in the late 1920s and continued throughout the entire 1930s. It affected some countries more than others, and the effects in the U.S. were detrimental. In 1933, around 25% of all workers were unemployed in America. Many families starved or lost their homes. Some tried traveling to the West to find work, also to no avail. Because of the prolonged recovery of the United States economy and the major changes that the Great Depression forced the government to make, the creation of fiscal policy is often referred to as one of the defining moments in the history of the United States.

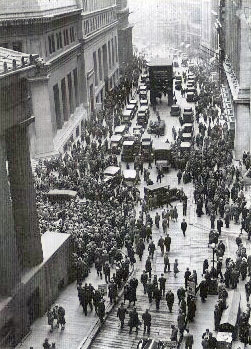

Crowds outside the New York Stock Exchange in 1929.

A solemn crowd gathers outside the Stock Exchange after the crash.

Another contributor to changing the role of government in the 1930s was President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. FDR was important because he implicated the New Deal, a program that would offer relief, recovery, and reform to the American nation. In terms of relief, new organizations (such as the Works Progress Administration) saved the lives of many U.S. citizens. The reform aspect was indeed the most influential in the New Deal, as it forever changed the role of government in the U.S. economy.

FDR

FDR’s “New Deal” policies were based on the principle of government intervention and regulation of the economy.

World War II and Effects

World War II forced the government to run huge deficits, or spend more than they were generating economically, in order to keep up with all of the production the U.S. military needed. By running deficits, the economy recovered, and America rebounded from its drought of unemployment. The military strategy of full employment had a huge benefit: the government’s massive deficits were used to pay for the war, and ended the Great Depression. This phenomenon set the standard and showed just how necessary it was for the government to play an active role in fiscal policy.

Modern Fiscal Policy

In 1971, at Bretton Woods, the U.S. went off the gold standard, allowing the dollar to float. Shortly after that, OPEC pegged the price of oil to gold rather than the dollar. The 70s were marked by oil shocks, recessions, and inflation in the U.S.

In late 2007 to early 2008, the economy would enter a particularly bad recession as a result of high oil and food prices, and a substantial credit crisis leading to the bankruptcy and eventual federal takeover of certain large and well-established mortgage providers. In an attempt to fix these economic problems, the United States federal government passed a series of costly economic stimulus and bailout packages. As a result of this, the deficit would increase to $455 billion and is projected to continue to increase dramatically for years to come, due in part to both the severity of the current recession and the high spending fiscal policy the federal government has adopted to help combat the nation’s economic woes.

16.3.4: Regulation and Antitrust Policy

Antitrust laws are a form of marketplace regulation intended to prohibit monopolization and unfair business practices.

Learning Objective

Assess the balance the federal government attempts to strike between regulation and deregulation

Key Points

- A number of governmental programs review regulatory innovations in order to minimize and simplify those regulations, and to make regulations more cost-effective.

- Government agencies known as competition regulators, as well as private litigants, apply antitrust and consumer protection laws in the hopes of preventing market failure.

- Large companies with huge cash reserves and large lines of credit can stifle competition by engaging in predatory pricing, in which they intentionally sell their products and services at a loss for a time, in order to force smaller competitors out of business.

Key Terms

- Antitrust Law

-

The United States antitrust law is a body of law that prohibits anti-competitive behavior (monopolization) and unfair business practices. Antitrust laws are intended to encourage competition in the marketplace.

- regulation

-

A regulation is a legal provision that creates, limits, or constrains a right; creates or limits a duty; or allocates a responsibility.

A regulation is a legal provision with many possible functions. It can create or limit a right; it can create or limit a duty; or it can allocate a responsibility. Regulations take many forms, including legal restrictions from a government authority, contractual obligations, industry self-regulations, social regulations, co-regulations, and market regulations.

State, or governmental, regulation attempts to produce outcomes which might not otherwise occur. Common examples of this type of regulation include laws that control prices, wages, market entries, development approvals, pollution effects, employment for certain people in certain industries, standards of production for certain goods, the military forces, and services.

The study of formal (legal and/or official) and informal (extra-legal and/or unofficial) regulation is one of the central concerns of the sociology of law. Scholars in this field are particularly interested in exploring the degree to which formal and legal regulation actually changes social behavior.

Deregulation, Regulatory Reform, and Liberalization

According to the Competitive Enterprise Institute, government regulation in the United States costs the economy approximately $1.75 trillion per year, a number that exceeds the combined total of all corporate pretax profits. Because of this, programs exist that review regulatory initiatives in order to minimize and simplify regulations, and to make them more cost-effective. Such efforts, given impetus by the Regulatory Flexibility Act of 1980 in the United States, are embodied in the United States Office of Management and Budget’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. Economists also occasionally develop regulation innovations, such as emissions trading.

U.S. Department of Justice

The Department of Justice is home to the U.S. anti-trust enforcers.

U.S. Antitrust Law

U.S. antitrust law is a body of law that prohibits anti-competitive behavior (monopolization) and unfair business practices. Intended to encourage competition in the marketplace, these laws make it illegal for businesses to employ practices that hurt other businesses or consumers, or that generally violate standards of ethical behavior. Government agencies known as competition regulators, along with private litigants, apply the antitrust and consumer protection laws in hopes of preventing market failure. Originally, these types of laws emerged in the U.S. to combat “corporate trusts,” which were big businesses. Other countries use the term “competition law” for this action. Many countries, including most of the Western world, have antitrust laws of some form. For example, the European Union has provisions under the Treaty of Rome to maintain fair competition, as does Australia under its Trade Practices Act of 1974.

Antitrust Rationale

Antitrust laws prohibit monopolization, attempted monopolization, agreements that restrain trade, anticompetitive mergers, and, in some circumstances, price discrimination in the sale of commodities.

Monopolization, or attempts to monopolize, are offenses that an individual firm may commit. Typically, this behavior involves a firm using unreasonable, unlawful, and exclusionary practices that are intended to secure, for that firm, control of a market. Large companies with huge cash reserves and large lines of credit can stifle competition by engaging in predatory pricing, in which they intentionally sell their products and services at a loss for a time, in order to force smaller competitors out of business. Afterwards, with no competition, these companies are free to consolidate control of an industry and charge whatever prices they desire.

A number of barriers make it difficult for new competitors to enter a market, including the fact that entry requires a large upfront investment, specific investments in infrastructure, and exclusive arrangements with distributors, customers and wholesalers. Even if competitors do shoulder these costs, monopolies will have ample warning and time in which to either buy out the competitor, engage in its own research, or return to predatory pricing long enough to eliminate the upstart business.

Federal Antitrust Actions

The federal government, via the Antitrust Division of the United States Department of Justice, and the Federal Trade Commission, can bring civil lawsuits enforcing the laws. Famous examples of these lawsuits include the government’s break-up of AT&T’s local telephone service monopoly in the early 1980s, and governmental actions against Microsoft in the late 1990s.

The federal government also reviews potential mergers to prevent market concentration. As a result of the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act, larger companies attempting to merge must first notify the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division prior to consummating a merger. These agencies then review the proposed merger by defining what the market is, and then determining the market concentration using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index and each company’s market share. The government is hesitant to allow a company to develop market power, because if unchecked, such power can lead to monopoly behavior.

Exemptions to Antitrust Laws

Several types of organizations are exempt from federal antitrust laws, including labor unions, agricultural cooperatives, and banks. Mergers and joint agreements of professional football, hockey, baseball, and basketball leagues are exempt. Newspapers run by joint operating agreements are also allowed limited antitrust immunity under the Newspaper Preservation Act of 1970.

16.3.5: Subsidies and Contracting

A subsidy is assistance paid to business, economic sectors, or producers; a contract is an agreement between two or more parties.

Learning Objective

Discuss the aims of subsidies and their effects on supply and demand

Key Points

- Subsidies are often regarded as a form of protectionism or trade barrier by making domestic goods and services artificially competitive against imports. Subsidies may distort markets and can impose large economic costs.

- A subsidy may be an efficient means of correcting a market failure. For example, economic analysis may suggest that direct subsidies (cash benefits) would be more efficient than indirect subsidies (such as trade barriers).

- Government procurement in the United States addresses the federal government’s need to acquire goods, services (including construction), and interests in real property.

- The authority of a contracting officer (the Government’s agent) to contract on behalf of the Government is set forth in public documents (a warrant) that a person dealing with the contracting officer can review.

Key Terms

- Contract

-

An agreement entered into voluntarily by two or more parties with the intention of creating a legal obligation, which may have elements in writing, though contracts can be made orally.

- subsidy

-

Assistance paid to a business, economic sector, or producers.

Subsidy

A subsidy is assistance paid to a business, economic sector or producers. Most subsidies are paid by the government to producers or distributed as subventions in an industry to prevent the decline of that industry, to increase the prices of its products, or simply to encourage the hiring of more labor. Some subsidies are to encourage the sale of exports; some are for food to keep down the cost of living; and other subsidies encourage the expansion of farm production.

Subsidies

This graph depicts U.S. farm subsidies in 2005.

Subsidies are often regarded as a form of protectionism or trade barrier by making domestic goods and services artificially competitive against imports. Subsidies may distort markets and can impose large economic costs. Financial assistance in the form of subsidies may come from a government, but the term subsidy may also refer to assistance granted by others, such as individuals or non-governmental institutions.

Examples of industries or sectors where subsidies are often found include utilities, gasoline in the United States, welfare, farm subsidies, and (in some countries) certain aspects of student loans.

Types of Subsidies

Ways to classify subsidies include the reason behind them, the recipients of the subsidy, and the source of the funds. One of the primary ways to classify subsidies is the means of distributing the subsidy. The term subsidy may or may not have a negative connotation. A subsidy may be characterized as inefficient relative to no subsidies; inefficient relative to other means of producing the same results; or “second-best;” implying an inefficient but feasible solution.

In other cases, a subsidy may be an efficient means of correcting a market failure. For example, economic analysis may suggest that direct subsidies (cash benefits) would be more efficient than indirect subsidies (such as trade barriers); this does not necessarily imply that direct subsidies are bad, but they may be more efficient or effective than other mechanisms to achieve the same (or better) results. Insofar as they are inefficient, subsidies would generally be considered bad, as economics is the study of efficient use of limited resources.

Effects

In standard supply and demand curve diagrams, a subsidy shifts either the demand curve up or the supply curve down. Subsidies that increase the production will tend to result in lower prices, while subsidies that increase demand will tend to result in an increase in price. Both cases result in a new economic equilibrium. The recipient of the subsidy may need to be distinguished from the beneficiary of the subsidy, and this analysis will depend on elasticity of supply and demand as well as other factors. The net effect and identification of winners and losers is rarely straightforward, but subsidies generally result in a transfer of wealth from one group to another (or transfer between sub-groups).

Government Procurement

Government procurement in the United States addresses the federal government’s need to acquire goods, services (including construction), and interests in real property. It involves the acquiring by contract, usually with appropriated funds, of supplies, services, and interests in real property by and for the use of the Federal Government. This is done through purchase or lease, whether the supplies, services, or interests are already in existence or must be created, developed, demonstrated, and evaluated.

The authority of a contracting officer (the Government’s agent) to contract on behalf of the Government is set forth in public documents (a warrant) that a person dealing with the contracting officer can review. The contracting officer has no authority to act outside of his or her warrant or to deviate from the laws and regulations controlling Federal Government contracts. The private contracting party is held to know the limitations of the contracting officer’s authority, even if the contracting officer does not. This makes contracting with the United States a very structured and restricted process. As a result, unlike in the commercial arena, where the parties have great freedom, a contract with the U.S. Government must comply with the laws and regulations that permit it, and must be made by a contracting officer with actual authority to execute the contract.

16.3.6: The Public Debt

Government debt, also known as public debt, or national debt, is the debt owed by a central government.

Learning Objective

Describe how countries finance activities by issuing debt

Key Points

- Government debt is one method of financing government operations but not the only method. Governments can also create money to monetize their debts, thus removing the need to pay interest. However, this practice simply reduces government interest costs rather than truly canceling government debt.

- As the government draws its income from much of the population, government debt is an indirect debt of the taxpayers.

- Lending to a national government in the country’s own currency is often considered risk free and is done at a so-called risk-free interest rate. This is because, up to a point, the debt and interest can be repaid by raising tax receipts, a reduction in spending, or by simply printing more money.

Key Terms

- Public Debt

-

Government debt, also known as public debt, or national debt, is the debt owed by a central government.

- Sovereign Debt

-

Sovereign debt usually refers to government debt that has been issued in a foreign currency.

- Government Bond

-

A government bond is a bond issued by a national government. Such bonds are often denominated in the country’s domestic currency.

Government Debt

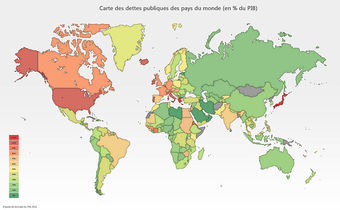

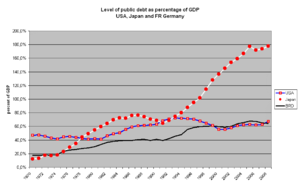

Government debt, also known as public debt, or national debt, is the debt owed by a central government. In the U.S. and other federal states, “government debt” may also refer to the debt of a state or provincial government, municipal or local government. Government debt is one method of financing government operations, but it is not the only method. Governments can also create money to monetize their debts, thereby removing the need to pay interest. However, this practice simply reduces government interest costs rather than truly canceling government debt. shows each country’s public debt as a percentage of their GDP in 2011.

Global Public Debt

This map shows each country’s public debt as a percentage of their GDP.

Governments usually borrow by issuing securities, government bonds and bills. Less creditworthy countries sometimes borrow directly from a supranational organization (the World Bank) or international financial institutions. As the government draws its income from much of the population, government debt is an indirect debt of the taxpayers. Government debt can be categorized as internal debt (owed to lenders within the country) and external debt (owed to foreign lenders). Sovereign debt usually refers to government debt that has been issued in a foreign currency. A broader definition of government debt may consider all government liabilities, including future pension payments and payments for goods and services the government has contracted but not yet paid.

Government and Sovereign Bonds

A government bond is a bond issued by a national government. Such bonds are often denominated in the country’s domestic currency. Most developed country governments are prohibited by law from printing money directly, that function having been relegated to their central banks. However, central banks may buy government bonds in order to finance government spending, thereby monetizing the debt.

Bonds issued by national governments in foreign currencies are normally referred to as sovereign bonds. Investors in sovereign bonds denominated in foreign currency have the additional risk that the issuer may be unable to obtain foreign currency to redeem the bonds.

Denominated in Reserve Currencies

Governments often borrow money in currency in which the demand for debt securities is strong. An advantage of issuing bonds in a currency such as the US dollar, the pound sterling, or the euro is that many investors wish to invest in such bonds.

Risk

Lending to a national government in the country’s own sovereign currency is often considered “risk free” and is done at a so-called “risk-free interest rate. ” This is because, up to a point, the debt and interest can be repaid by raising tax receipts (either by economic growth or raising tax rates), a reduction in spending, or failing that by simply printing more money. It is widely considered that this would increase inflation and reduce the value of the invested capital. A typical example of this is provided by Weimar Germany of the 1920s which suffered from hyperinflation due to its government’s inability to pay the national debt deriving from the costs of World War I.

In practice, the market interest rate tends to be different for debts of different countries. An example is in borrowing by different European Union countries denominated in euros. Even though the currency is the same in each case, the yield required by the market is higher for some countries’ debt than for others. This reflects the views of the market on the relative solvency of the various countries and the likelihood that the debt will be repaid.

A politically unstable state is anything but risk-free as it may cease its payments. Another political risk is caused by external threats. It is mostly uncommon for invaders to accept responsibility for the national debt of the annexed state or that of an organization it considered as rebels. For example, all borrowings by the Confederate States of America were left unpaid after the American Civil War. On the other hand, in the modern era, the transition from dictatorship and illegitimate governments to democracy does not automatically free the country of the debt contracted by the former government. Today’s highly developed global credit markets would be less likely to lend to a country that negated its previous debt, or might require punishing levels of interest rates that would be unacceptable to the borrower.

U.S. Treasury bonds denominated in U.S. dollars are often considered “risk free” in the U.S. This disregards the risk to foreign purchasers of depreciation in the dollar relative to the lender’s currency. In addition, a risk-free status implicitly assumes the stability of the US government and its ability to continue repayments during any financial crisis.

Lending to a national government in a currency other than its own does not give the same confidence in the ability to repay, but this may be offset by reducing the exchange rate risk to foreign lenders. Usually small states with volatile economies have most of their national debt in foreign currency.

16.4: Taxes

16.4.1: The Federal Tax System

The United States is a federal republic with autonomous state and local governments with taxes imposed at each level.

Learning Objective

Describe the various levels of the tax structure in the United States

Key Points

- Taxes are imposed on net income of individuals and corporations by federal, most state, and some local governments. Federal tax rates vary from 10% to 35% of taxable income. State and local tax rates vary widely by jurisdiction, from 0% to 12.696% and many are graduated.

- Payroll taxes are imposed by the federal and all state governments. These include Social Security and Medicare taxes imposed on both employers and employees, at a combined rate of 15.3% (13.3% for 2011).

- Property taxes are imposed by most local governments and many special purpose authorities based on the fair market value of property. Sales taxes are imposed on the price at retail sale of many goods and some services by most states and some localities.

Key Terms

- tariff

-

a system of government-imposed duties levied on imported or exported goods; a list of such duties, or the duties themselves

- autonomous

-

Self-governing. Governing independently.

The Federal Tax System

The United States is a federal republic with autonomous state and local governments. Taxes are imposed at each of these levels. These include taxes on income, payroll, property, sales, imports, estates and gifts, as well as various fees. The taxes collected in 2010 by federal, state and municipal governments amounted to 24.8% of the GDP.

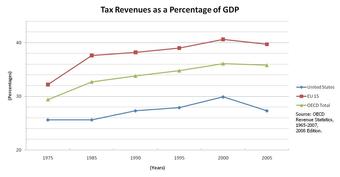

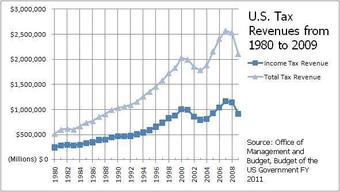

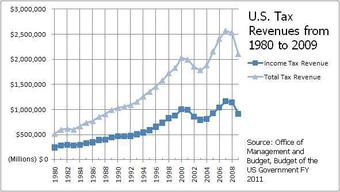

U.S. Tax Revenues

U.S. Tax Revenues as a Percentage of GDP

Taxes are imposed on net income of individuals and corporations by the federal, most state, and some local governments. Citizens and residents are taxed on worldwide income and allowed a credit for foreign taxes. Income subject to tax is determined under tax rules, not accounting principles, and includes almost all income. Most business expenses reduce taxable income, though limits apply to a few expenses. Individuals are permitted to reduce taxable income by personal allowances and certain non-business expenses that can include home mortgage interest, state and local taxes, charitable contributions, medical, and certain other expenses incurred above certain percentages of income. State rules for determining taxable income often differ from federal rules. Federal tax rates vary from 10% to 35% of taxable income. State and local tax rates vary widely by jurisdiction, from 0% to 12.696% and many are graduated. State taxes are generally treated as a deductible expense for federal tax computation. Certain alternative taxes may apply. The United States is the only country in the world that taxes its nonresident citizens on worldwide income or estate, in the same manner and rates as residents.