4.1: Civil Liberties and the Bill of Rights

4.1.1: The Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights is the collective name for the first ten amendments to the US Constitution and they guarantee certain liberties.

Learning Objective

Explain how the Bill of Rights is used to protect natural rights of liberty and property.

Key Points

- The Bill of Rights was introduced by James Madison to the 1st US Congress as a series of legislative articles. Without a Bill of Rights, the Constitution may not have been ratified.

- Originally, the Bill of Rights implicitly and legally protected only white men, excluding American Indians, people considered to be “black” (now described as African Americans), and women.

- The Bill of Rights originally only applied to the federal government, but has since been expanded to apply to the states as well.

- The Bill of Rights includes protections such as freedom of the press, speech, religion, and assembly; the right to due process and fair trials; the right to personal property and other rights.

Key Terms

- Fourteenth Amendment

-

An amendment to the US Constitution containing a clause that has been used to make most of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states, as well as to recognize substantive and procedural rights.

- Bill of Rights

-

The collective name for the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution.

- amendment

-

An addition and/or alteration to the Constitution.

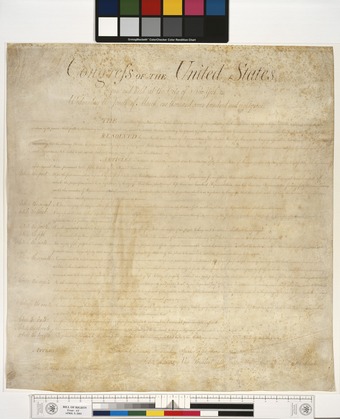

The Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights is the collective name for the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution . These limitations serve to protect the natural rights of liberty and property. They guarantee a number of personal freedoms, limit the government’s power in judicial and other proceedings, and reserve some powers to the states and the public. While the amendments originally applied only to the federal government, most of their provisions have since been held to apply to the states by way of the Fourteenth Amendment.

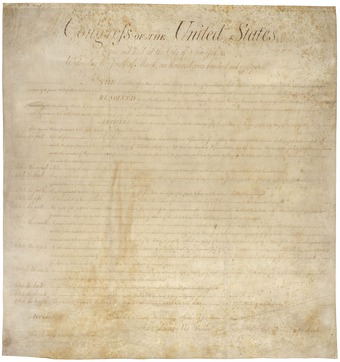

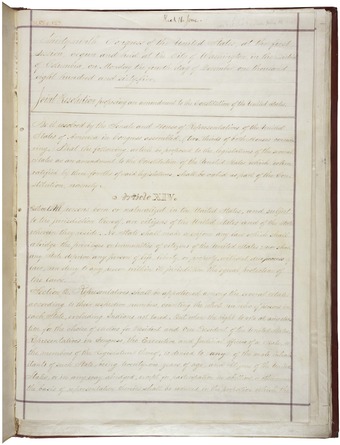

The Bill of Rights of the United States of American

The United States Bill of Rights, which are the first 10 amendments to the US Constitution, and the core of American civil liberties.

History of the Bill of Rights

The Constitution may never have been ratified if a bill of rights had not been added . Most state constitutions adopted during the Revolution had included a clear declaration of the rights of all people, and most Americans believed that no constitution could be considered complete without such a declaration.

Signing the Constitution

This painting depicts the signing of the US Constitution. Without the addition of the Bill of Rights, it is unlikely that the Constitution would have been ratified.

The amendments that would become the Bill of Rights were introduced by James Madison as a series of legislative articles . They were adopted by the House of Representatives on August 21, 1789, and came into effect as Constitutional Amendments on December 15, 1791, through the process of ratification by three-fourths of the States.

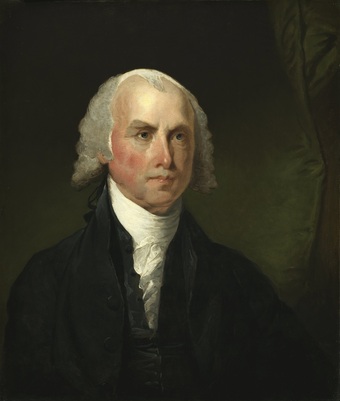

Portrait of James Madison

James Madison, “Father of the Constitution” and first author of the Bill of Rights

Congress passed twelve amendments, yet only ten were originally passed by the states. One of the two rejected amendments dealt with the size of the House of Representatives, and the other rejected amendment provided that Congress could not change the salaries of its members until after an election of representatives had been held (it was ratified 202 years later, becoming the 27th Amendment).

Original Exclusions from the Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights implicitly and legally only protected white land-owning men, excluding American Indians, people considered to be “black” (now described as African Americans), and women. These exclusions were not explicit in the Bill of Right’s text, but were well understood and applied. Gradually, these exclusions were lifted by subsequent interpretations or amendments, so in contemporary times, the Bill of Rights protects all classes of people.

Protected Rights

- The First Amendment protects freedom of religion, speech, press, assembly and petition.

- The Second Amendment protects the right of Americans to bear arms.

- The Third Amendment prevents the government from quartering (housing) soldiers in civilian’s homes during peace time without the consent of the civilian.

- The Fourth Amendment provides protection from unreasonable search and seizure.

- The Fifth Amendment establishes rights related to due process, double jeopardy, self-incrimination, and eminent domain.

- The Sixth Amendment sets out rights of the accused of a crime: a trial by jury, a speedy trial, a public trial, the right to face the accusers, and the right to counsel.

- The Seventh Amendment protects the right to a trial by jury for civil trials.

- The Eighth Amendment prohibits excessive bail and cruel and unusual punishment.

- The Ninth Amendment protects rights not specifically enumerated in the Constitution. Some people feared that the listing of some rights in the Bill of Rights would be interpreted to mean that other rights not listed were not protected. This amendment was adopted to prevent such a misinterpretation.

- The Tenth Amendment confirms that the states or the people retain all powers not given to the national government. This amendment was adopted to reassure people that the national government would not swallow up the states.

4.1.2: Nationalizing the Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights were included into state laws through selective incorporation, rather than through full incorporation or nationalization.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast the difference between nationalization and selective incorporation of the Bill of Rights.

Key Points

- The Bill of Rights were gradually incorporated into state law, through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

- There were two opposing viewpoints that debated how the Bill of Rights should be incorporated at the state level. One argued for total incorporation, or nationalization, of the first eight amendments. Others argued for gradual and selective incorporation.

- Justice Hugo Black argued for the nationalization of the Bill of Rights, but the Supreme Court eventually adopted a practice of selective incorporation.

Key Terms

- selective incorporation

-

the process by which American courts have applied certain portions of the U.S. Bill of Rights to the states

- Bill of Rights

-

The collective name for the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution.

- Fourteenth Amendment

-

An amendment to the US Constitution containing a clause that has been used to make most of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states, as well as to recognize substantive and procedural rights.

- incorporation doctrine

-

The process by which American courts have applied portions of the US Bill of Rights to the states, using the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Incorporating the Bill of Rights

The incorporation of the Bill of Rights (also called the incorporation doctrine) is the process by which American courts have applied portions of the United States’ Bill of Rights to the states. According to the doctrine of incorporation, the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment applies the Bill of Rights to the states.

Prior to the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment and the development of the incorporation doctrine, the Supreme Court held in Barron v. Baltimore (1833) that the Bill of Rights applied only to the federal government, not to any state governments. However, beginning in the 1920s, a series of United States Supreme Court decisions interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment to “incorporate” most portions of the Bill of Rights, making these portions, for the first time, enforceable against the state governments.

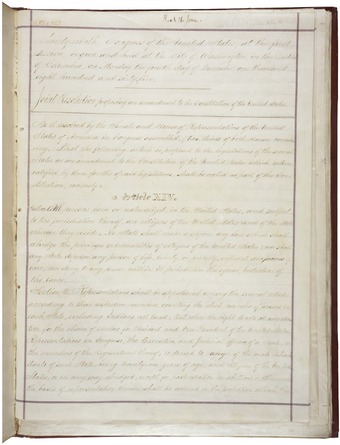

14th Amendment of the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment, depicted here, allowed for the incorporation of the First Amendment against the states.

Nationalization Versus Selective Incorporation

After the Fourteenth Amendment was passed, the Supreme Court debated how to incorporate the Bill of Rights into state legislation. Some argued that the Bill of Rights should be fully incorporated. This is referred to as “total” incorporation, or the “nationalization” of the Bill of Rights. On the other hand, some believed that incorporation should be selective, in that only the rights deemed fundamental (like the rights protected under the First Amendment) should be applied to the states, and it should be a gradual process. The Supreme Court eventually pursued selective incorporation.

Hugo Black: A Champion for Nationalization

Even though the Supreme Court decided on selective incorporation, there were some who advocated for a total incorporation or nationalization of the Bill of Rights. Justice Hugo Black championed this view. Black called for the nationalization of the first eight amendments of the Bill of Rights (Amendments 9 and 10 being patently connected to the powers of the federal government alone), and his most famous expression of this belief is found in his dissenting opinion in the Supreme Court case, Adamson v. California (1947).

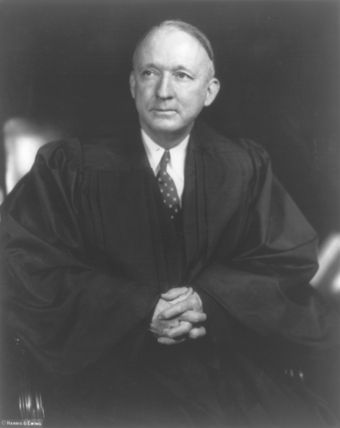

Justice Hugo Black

Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black is noted for the complete nationalization of the Bill of Rights.

4.1.3: Incorporation Doctrine

The incorporation of the Bill of Rights is the process by which American courts have applied portions of the Bill of Rights to the states.

Learning Objective

Indicate how the Bill of Rights was incorporated by the the Federal government in the States

Key Points

- Prior to the 1890s, the Bill of Rights was held only to apply to the federal government, which was a principle solidified even further by a Supreme Court case in 1833 (Barron v. Baltimore).

- The Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause has been used to apply portions of the Bill of Rights to the state through selective incorporation. This amendment is cited in US litigation more than any other amendment.

- By the last half of the 20th century, nearly all of the first 8 amendments have been incorporated into state law (except the 3rd Amendment, and certain parts of the 5th, 7th, and 8th). The 9th and 10th Amendments apply to the federal government, and so have not been incorporated.

- Incorporation of the Bill of Rights into state law began with the case Gitlow v. New York (1925), in which the Supreme Court upheld that states must respect freedom of speech.

Key Terms

- Fourteenth Amendment

-

An amendment to the US Constitution containing a clause that has been used to make most of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states, as well as to recognize substantive and procedural rights.

- due process

-

The limits of laws and legal proceedings, so as to ensure a person fairness, justice, and liberty.

- incorporation doctrine

-

The process by which American courts have applied portions of the US Bill of Rights to the states, using the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

What is the Incorporation Doctrine?

As described, the incorporation of the Bill of Rights is the process by which American courts have applied portions of the U.S. Bill of Rights to the states, by virtue of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution.

The Fourteenth Amendment and Moving Towards Incorporation

In Barron v. Baltimore (1833), the Supreme Court declared that the Bill of Rights applied to the federal government, and not to the states. Some argue that the intention of the creator of the Fourteenth Amendment was to overturn this precedent.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments. Its Due Process Clause prohibits state and local governments from depriving persons of life, liberty, or property without certain steps being taken to ensure fairness. This clause has been used to make most of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states, as well as to recognize substantive and procedural rights .

14th Amendment of the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment, depicted here, allowed for the incorporation of the First Amendment against the states.

The first instance of incorporation include the case Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad v. City of Chicago (1897), in which the Supreme Court required just compensation for property appropriated by state or local authorities (so this was an application of the Fifth Amendment in the Bill of Rights). More commonly, it is argued that incorporation began in the case Gitlow v. New York (1925), in which the Court expressly held that States were bound to protect freedom of speech. Since that time, the Court has steadily incorporated most of the significant provisions of the Bill of Rights.

Selective Incorporation

In Adamson v. California (1947), Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black argued in his dissent that the Supreme Court should pursue nationalization of the Bill of Rights. Despite his opinion, in the following twenty-five years, the Supreme Court employed a doctrine of selective incorporation that succeeded in extending to the States almost of all of the protections in the Bill of Rights, as well as other, unenumerated rights. The Fourteenth Amendment has vastly expanded civil rights protections and is cited in more litigation than any other amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Which Amendments Have Been Incorporated?

By the latter half of the 20th century, nearly all of the rights in the Bill of Rights had been applied to the states, under the incorporation doctrine.

All of the provisions of Amendment I and Amendment II have been incorporated against the state, while the Third Amendment has not yet been incorporated (the Third Amendment refers to the prohibition on quartering of soldiers in civilian homes).

Amendment IV, unreasonable search and seizure, has been incorporated against the states by the Supreme Court’s decision in Wolf v. Colorado (1949). The exclusion of unlawfully seized evidence has been incorporated against the states in Mapp v. Ohio (1961).

Amendment V, the right to indictment by a grand jury, has been held not to be incorporated against the states, but protection against double jeopardy and protection against self-incrimination have been incorporated against the states in Malloy v. Hogan (1964) .

Incorporating Amendment V

Here, a US law enforcement official reads an arrested person his rights. Amendment V, the right to due process, has been incorporated against the states.

Amendment VI, the rights to a speedy, public, and impartial trial have been incorporated against the states, as has the right to counsel in Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) .

Incorporating Amendment VI

Amendment VI, the right to a trial by a jury and the right to counsel, was incorporated against the states in the case Gideon v. Wainwright (1963). Here, this right is exercised as an attorney asks questions during jury selection.

Amendment VII, right to a jury trial in civil cases, has been held not to be applicable to the states.

Amendment VIII, the right to jury trial in civil cases has been held not to be incorporated against the states, but protection against “cruel and unusual punishments” has been incorporated against the states.

Amendments IX and X have not been incorporated against the states, as they apply expressly to the federal government alone.

4.2: The First Amendment: The Right to Freedom of Religion, Expression, Press, and Assembly

4.2.1: The First Amendment

The First Amendment to the US Constitution is part of the Bill of Rights, and protects core American civil liberties.

Learning Objective

Compare and contrast civil rights with civil liberties with respect to the First Amendment

Key Points

- The First Amendment protects Americans’ rights to religious freedom. As part of this, the US cannot establish a religion nor prevent free exercise of religion.

- The First Amendment protects Americans’ rights to the freedom of speech, press, assembly, and petition.

- Originally, the First Amendment applied only to the federal government. However, Gitlow v. New York (1925) used provisions found in the Fourteenth Amendment to apply the First Amendment to the states as well.

- Some of the rights protected in the First Amendment have roots in other countries’ declarations of rights. In particular, the English Bill of Rights, the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, and the Philippine Constitution all have similar elements to the First Amendment.

- Clear and present danger was a doctrine adopted by the Supreme Court of the United States to determine under what circumstances limits can be placed on First Amendment freedoms of speech, press or assembly.

- In the 1919 case Schenck v. United States the Supreme Court held that an anti-war activist did not have a First Amendment right to speak out against the draft.

Key Terms

- French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

-

A fundamental document of the French Revolution and in the history of human rights, defining the individual and collective rights of all the estates of the realm as universal.

- First Amendment

-

The first of ten amendments to the constitution of the United States, which protects freedom of religion, speech, assembly, and the press.

- civil liberties

-

Civil rights and freedoms such as the freedom from enslavement, freedom from torture and right to a fair trial.

The First Amendment

The First Amendment (Amendment I) to the United States Constitution is part of the Bill of Rights and protects American civil liberties. The amendment prohibits the making of any law pertaining to an establishment of a federal or state religion, impeding the free exercise of religion, abridging the freedom of speech, infringing on the freedom of the press , interfering with the right to peaceably assemble, or prohibiting the petitioning for a governmental redress of grievances .

Vietnam War Protest in Washington D.C., April, 1971

The First Amendment established the right to assemble as a core American liberty, as is depicted here in a Vietnam-era assembly.

Freedom of the Press Worldwide

The First Amendment to the Constitution guarantees Americans the right to a free press. This is something that many other countries do not enjoy, as this map illustrates.

The text of the First Amendment reads, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. “

Anti-war protests during World War I gave rise to several important free speech cases related to sedition and inciting violence. Clear and present danger was a doctrine adopted by the Supreme Court of the United States to determine under what circumstances limits can be placed on First Amendment freedoms of speech, press or assembly. Before the twentieth century, most free speech issues involved prior restraint. Starting in the early 1900s, the Supreme Court began to consider cases in which persons were punished after speaking or publishing.

In the 1919 case Schenck v. United States the Supreme Court held that an anti-war activist did not have a First Amendment right to speak out against the draft. The clear and present danger test was established by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. in the unanimous opinion for the case Schenck v. United States, concerning the ability of the government to regulate speech against the draft during World War I. Following Schenck v. United States, “clear and present danger” became both a public metaphor for First Amendment speech and a standard test in cases before the Court where a United States law limits a citizen’s First Amendment rights; the law is deemed to be constitutional if it can be shown that the language it prohibits poses a “clear and present danger.

Incorporating the First Amendment

Originally, the First Amendment applied only to laws enacted by the Congress. However, starting with Gitlow v. New York (1925), the Supreme Court has applied the First Amendment to each state. This was done through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment . The Court has also recognized a series of exceptions to provisions protecting the freedom of speech.

14th Amendment of the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment, depicted here, allowed for the incorporation of the First Amendment against the states.

Background to the First Amendment

Opposition to the ratification of the Constitution was partly based on the Constitution’s lack of adequate guarantees for civil liberties. To provide such guarantees, the First Amendment, along with the rest of the Bill of Rights, was submitted to the states for ratification on September 25, 1789, and adopted on December 15, 1791.

Comparing the First Amendment to Other Rights Protection Instruments

Some provisions of the United States Bill of Rights have their roots in similar documents from England, France, and the Philippines. The English Bill of Rights, however, does not include many of the protections found in the First Amendment. For example, the First Amendment guarantees freedom of speech to the general populace but the English Bill of Rights protected only free speech in Parliament . A French revolutionary document, the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, passed just weeks before Congress proposed the Bill of Rights, contains certain guarantees that are similar to those in the First Amendment. Parts of the Constitution of the Philippines, written in 1987, contain identical wording to the First Amendment regarding speech and religion. Echoing Jefferson’s famous phrase, all three constitutions, in the section on Principles, contain the sentence, “The separation of Church and State shall be inviolable”.

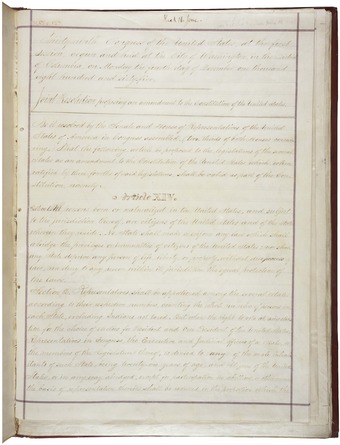

English Bill of Rights

The US Bill of Rights drew many of its First Amendment provisions from other countries’ bill of rights, such as the English Bill of Rights. However, the US Bill of Rights established more liberties than the English Bill of Rights.

Although the First Amendment does not explicitly set restrictions on freedom of speech, other declarations of rights occasionally do. For example, The European Convention on Human Rights permits restrictions “in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or the rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary. ” Similarly, the Constitution of India allows “reasonable” restrictions upon free speech to serve “public order, security of State, decency or morality. “

Lastly, the First Amendment was one of the first guarantees of religious freedom: neither the English Bill of Rights nor the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen contain a similar guarantee.

4.2.2: Freedom of Religion

Freedom of religion is a constitutionally guaranteed right, established in the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights.

Learning Objective

Summarize the meaning of “freedom of religion” in the U.S. constitution

Key Points

- The protection of religious freedom is laid out in the First Amendment, which states that Congress cannot establish a state religion nor prohibit free exercise of religion.

- The Establishment Clause prevents the U.S. from creating a state or national religion, from favoring one religion over another, or entangling the government with religion.

- The Free Exercise Clause gives all Americans the right to practice their religion freely, without interference or persecution by the government.

Key Terms

- Bill of Rights

-

The collective name for the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution.

- freedom of religion

-

The right of citizens to hold any religious or non-religious beliefs, and to carry out any practices in accordance with those beliefs, so long as they do not interfere with another person’s legal or civil rights, or any reasonable laws, without fear of harm or prosecution.

- civil liberties

-

Civil rights and freedoms such as the freedom from enslavement, freedom from torture and right to a fair trial.

The First Amendment

In the United States, freedom of religion is a constitutionally guaranteed right , laid out in the Bill of Rights. The following religious civil liberties are guaranteed by the First Amendment to the Constitution: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. ” Thus, freedom of religion in the U.S. has two parts: the prohibition on the establishment of a state religion, and the right of all citizens to practice their religion.

Monument to the Right to Worship

This monument in Washington, DC honors the right to worship. The inscription reads, “Our liberty of worship is not a concession nor a privilege, but an inherent right. “

No U.S. State Religion

Many countries have made one religion into the established (official) church, and support it with government funds . In what is called the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment (“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion”), Congress is forbidden from setting up, or in any way providing for, an established church. It has been interpreted to forbid government endorsement of, or aid to, religious doctrines. The Federal Government may not establish a national church or religion or excessively involve itself in religion, particularly to the benefit of one religion over another.

No State Religion

The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment prohibits the creation of a state religion in the U.S. Other countries have had state religions; for instance, the Church of England once dominated religious and political life (former Anglican church depicted here).

Freedom to Practice Religion

In addition to the rights afforded under the Establishment Clause, the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment protects the rights of citizens to practice their religions. This clause states that Congress cannot “prohibit the free exercise” of religious practices.

Incorporation of the First Amendment

The Supreme Court has interpreted the 14th Amendment as applying the First Amendment’s provisions on the freedom of religion to states as well as to the Federal Government. Therefore, states must guarantee freedom of religion in the same way the Federal Government must. Many states have freedom of religion established in their constitution, though the exact legal consequences of this right vary for historical and cultural reasons.

Most states interpret “freedom of religion” as including the freedom of long-established religious communities to remain intact and not be destroyed. By extension, democracies interpret “freedom of religion” as the right of each individual to freely choose to convert from one religion to another, mix religions, or abandon religion altogether.

4.2.3: The Establishment Clause: Separation of Church and State

As part of the First Amendment’s religious freedom guarantees, the Establishment Clause requires a separation of church and state.

Learning Objective

Distinguish the Establishment Clause from other clauses of the First Amendment

Key Points

- The Establishment Clause prohibits the creation of a national religion, and also prohibits the US government from favoring one religion over another or excessively entangling itself with religious issues or groups.

- Thomas Jefferson is often cited as being the one who introduced the concept of the separation of church and state.

- The Establishment Clause has been incorporated against the states via the Fourteenth Amendment. However, the process has been tricky, as it is argued that the Fourteenth Amendment speaks to individual rights, while the Establishment Clause does not.

- The Supreme Court has made judgments on three main questions: can the US government give financial assistance to religious groups? Is state-sanctioned prayer in public schools acceptable? Are religious displays in government-affiliated places acceptable?

- The “Lemon Test,” established by Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971) provided a three-part test for determining whether or not a law or act violates the Establishment Clause.

Key Terms

- Lemon Test

-

a method of measuring weather a government action violates the Establishment Clause of the United States’ constitution concerning religion. To pass the test, the action must have a secular legislative purpose, must not have the primary effect of either advancing or inhibiting religion, and must not result in an “excessive government entanglement” with religion.

- Thomas Jefferson

-

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 (April 2, 1743 O.S.) – July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Father, the principal author of the Declaration of Independence (1776) and the third President of the United States (1801–1809).

- First Amendment

-

The first of ten amendments to the constitution of the United States, which protects freedom of religion, speech, assembly, and the press.

- separation of church and state

-

The distance in the relationship between organized religion and the nation state.

- establishment clause

-

a pronouncement in the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution which prohibits both the establishment of a national religion by Congress, and the preference by the U.S. government of one religion over another

The Establishment Clause

The Establishment Clause in the First Amendment to the Constitution states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion. ” Together with the Free Exercise Clause (“… or prohibiting the free exercise thereof”), these two clauses make up what are called the “religion clauses” of the First Amendment.

The Establishment Clause has generally been interpreted to prohibit (1) the establishment of a national religion by Congress, or (2) the preference by the U.S. government of one religion over another. The first approach is called the “separation” or “no aid” interpretation, while the second approach is called the “non-preferential” or “accommodation” interpretation. The accommodation interpretation prohibits Congress from preferring one religion over another, but does not prohibit the government’s entry into religious domain to make accommodations in order to achieve the purposes of the Free Exercise Clause.

The “Wall of Separation”

Thomas Jefferson wrote that the First Amendment erected a “wall of separation between church and state”, likely borrowing the language from Roger Williams, founder of the Colony of Rhode Island . James Madison, often regarded as the “Father of the Bill of Rights”, also often wrote of the “perfect separation”, “line of separation”, and “total separation of the church from the state. “

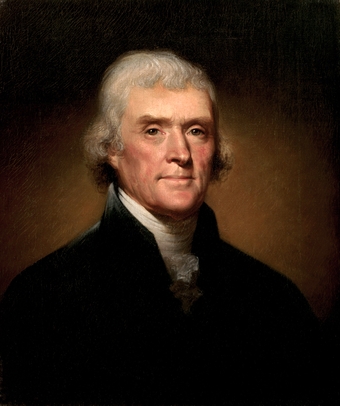

Thomas Jefferson

Founding Father and Third President of the United States. Thomas Jefferson’s phrase “the wall of separation,” is often quoted in debates on the Establishment Clause and the separation of church and state.

Incorporation of the Establishment Clause

Incorporation of the Establishment Clause in 1947 has been tricky and subject to much more critique than incorporation of the Free Exercise Clause. The controversy surrounding Establishment Clause incorporation primarily stems from the fact that one of the intentions of the Establishment Clause was to prevent Congress from interfering with state establishments of religion that existed at the time of the founding.

Critics have also argued that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment is understood to incorporate only individual rights found in the Bill of Rights; the Establishment Clause, unlike the Free Exercise Clause (which critics readily concede protects individual rights), does not purport to protect individual rights.

Controversy Over the Establishment Clause

Controversy rages in the United States between those who wish to restrict government involvement with religious institutions and remove religious references from government institutions and property, and those who wish to loosen such prohibitions. Advocates for stronger separation of church and state emphasize the plurality of faiths and non-faiths in the country, and what they see as broad guarantees of the federal Constitution. Their opponents emphasize what they see as the largely Christian heritage and history of the nation (often citing the references to “Nature’s God” and the “Creator” of men in the Declaration of Independence).

Main Questions of the Establishment Clause

One main question of the Establishment Clause is: does government financial assistance to religious groups violate the Establishment Clause? The Supreme Court first considered this issue in Bradfield v. Roberts (1899). The federal government had funded a hospital operated by a Roman Catholic institution. In that case, the Court ruled that the funding was to a secular organization—the hospital—and was therefore permissible.

Another main question is: should state-sanctioned prayer or religion in public schools be allowed? The Supreme Court has consistently held fast to the rule of strict separation of church and state in this issue. In Engel v. Vitale (1962) the Court ruled that government-imposed nondenominational prayer in public school was unconstitutional. In Lee v. Weisman (1992), the Court ruled prayer established by a principal at a middle school graduation was also unconstitutional, and in Santa Fe Independent School Dist. v. Doe (2000) it ruled that school officials may not directly or indirectly impose student-led prayer during high school football games .

Pledge of Allegiance

In 2002, controversy centered on a California court case that struck down a law providing for the recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance (which includes the phrase “under God”) in classrooms. Congress and the Supreme Court eventually overturned the ruling, demonstrating the controversy that exists in the interpretations of the Establishment Clause.

Lastly, are religious displays in public places allowed under the Establishment Clause? The inclusion of religious symbols in public holiday displays came before the Supreme Court in Lynch v. Donnelly (1984), and again in Allegheny County v. Greater Pittsburgh ACLU (1989). In the former case, the Court upheld a public display, ruling that any benefit to religion was “indirect, remote, and incidental. ” In Allegheny County, however, the Court struck down a display that had more overt religious themes .

Religious Displays

In 2001, the Chief Justice of Alabama installed a monument to the Ten Commandments in the state judicial building (pictured here). In 2003, a court case determined that this was not allowed under the Establishment Clause.

The Lemon Test

The distinction between force of government and individual liberty is the cornerstone of such cases. Each case restricts acts by government designed to establish a religion, while affirming peoples’ individual freedom to practice their religions. The Court has therefore tried to determine a way to deal with church/state questions. In Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), the Court created a three part test for laws dealing with religious establishment. This determined that a law related to religious practices was constitutional if it:

- Had a secular purpose;

- Neither advanced nor inhibited religion; and,

- Did not foster an excessive government entanglement with religion.

4.2.4: The Free Exercise Clause: Freedom of Religion

The Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment establishes the right of all Americans to freely practice their religions.

Learning Objective

Describe how the interpretation of the Free Exercise clause has changed over time.

Key Points

- The Free Exercise Clause and the Establishment Clause (which essentially establishes the separation of church and state), compose the provisions on religious freedom in the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights.

- The interpretation of the Free Exercise Clause has narrowed and widened throughout the past decades. In the late 1800s, the Supreme Court took the view that it acceptable for the government to pass neutral laws that may incidentally impact certain religions.

- During the time of the Warren Court in the 1960s, the Supreme Court took the view that there must be a “compelling interest” in order for religious freedom to be restricted.

- In the 1990s, the Supreme Court moved away from this strict interpretation of the Free Exercise Clause, and removed the idea that there had to be a “compelling interest” in order to violate religious freedom.

- Jehovah Witnesses have been involved in a lot of litigation related to the Free Exercise Clause and, consequently, have helped define its limits.

Key Terms

- strict scrutiny

-

The most stringent standard of legal review in American courts, used to evaluate the constitutionality of laws and government programs.

- Warren Court

-

The Supreme Court of the United States between 1953 and 1969, when Earl Warren served as Chief Justice. Warren led a liberal majority that used judicial power in dramatic fashion, expanding civil rights, civil liberties, judicial power, and the federal power.

- Jehovah’s Witnesses

-

A monotheistic and nontrinitarian Restoration Christian denomination founded in 1879 as a small Bible study group.

- free exercise clause

-

the accompanying clause with the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which prohibits Congress from interfering with the practices of any religion

The Free Exercise Clause

The Free Exercise Clause is the accompanying clause with the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause together read:” Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…” Thus, the Establishment Clause prevents the US from establishing or advocating for a specific religion, while the Free Exercise clause is intended to ensure the rights of Americans to practice their religions without state intervention . The Supreme Court has consistently held, however, that the right to free exercise of religion is not absolute, and that it is acceptable for the government to limit free exercise in some cases.

Church and Political Socialization

Participation in organized religion or church attendance can be another important source of political socialization, as churches often teach certain political values.

Interpreting the Free Exercise Clause

The history of the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Free Exercise Clause follows a broad arc, beginning with approximately 100 years of little attention. Then it took on a relatively narrow view of the governmental restrictions required under the clause. The 1960s saw it grow into a much broader view and later receding again.

In 1878, the Supreme Court was first called to interpret the extent of the Free Exercise Clause in Reynolds v. United States, as related to the prosecution of polygamy under federal law. The Supreme Court upheld Reynolds’ conviction for bigamy, deciding that to do otherwise would provide constitutional protection for a gamut of religious beliefs, including those as extreme as human sacrifice. This case, which also revived Thomas Jefferson’s statement regarding the “wall of separation” between church and state, introduced the position that although religious exercise is generally protected under the First Amendment, this does not prevent the government from passing neutral laws that incidentally impact certain religious practices.

This interpretation of the Free Exercise Clause continued into the 1960s. With the ascendancy of the Warren Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren, a new standard of “strict scrutiny” in various areas of civil rights law was applied. The Court established many requirements that had to be met for any restrictions of religious freedom. For example, in Sherbert v. Verner (1963), the Supreme Court required states to meet the “strict scrutiny” standard when refusing to accommodate religiously motivated conduct. This meant that a government needed to have a “compelling interest” regarding such a refusal. The case involved Adele Sherbert, who was denied unemployment benefits by South Carolina because she refused to work on Saturdays, something forbidden by her Seventh-day Adventist faith.

This view of the Free Exercise Clause would begin to narrow again in the 1980s, culminating in the 1990 case of Employment Division v. Smith. Examining a state prohibition on the use of peyote, the Supreme Court upheld the law despite the drug’s use as part of a religious ritual . In 1993, the Congress passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), which sought to restore the compelling interest requirement applied in Sherbert v. Yoder. In another case in 1997, the Court struck down the provisions of the Act on the grounds that, while the Congress could enforce the Supreme Court’s interpretation of a constitutional right, the Congress could not impose its own interpretation on states and localities.

Peyote Cactus

Native Americans used peyote (a cactus that has psychedelic effects when ingested) in spiritual rituals. In 1990, the Supreme Court banned the use of this drug, demonstrating a move away from the requirement to show “compelling interest” before limiting religious freedom.

Jehovah’s Witnesses Cases

During the twentieth century, many major cases involving the Free Exercise Clause were related to Jehovah’s Witnesses . Many communities directed laws against the Witnesses and their preaching work. From 1938 to 1955, the organization was involved in over forty cases before the Supreme Court, winning a majority of them. For example, the first important victory came in 1938 with Lovell v. City of Griffin. The Supreme Court held that cities could not require permits for the distribution of pamphlets.

Jehovah’s Witnesses

The specific beliefs and practices (such as a belief in door-to-door proselytizing, depicted here) of the Jehovah’s Witnesses has meant that Jehovah’s Witnesses’ litigation has played a key role in defining the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment.

4.2.5: Freedom of Speech

The freedom of speech is a protected right under the First Amendment, and while many categories of speech are protected, there are limits.

Learning Objective

Explain how freedom of speech is protected by the United States Constitution

Key Points

- The Bill of Right’s provision on the freedom of speech was incorporated against the states in Gitlow v. New York (1925).

- Core political speech, expressive speech, and most types of commercial speech are protected under the First Amendment.

- Certain types of speech (particularly, speech that can harm others) is not protected, such as obscenity, fighting words, true threats, child pornography, defamation, or invasion of privacy. Speech related to national security or state secrets may also not be protected.

Key Terms

- defamation

-

Act of injuring another’s reputation by any slanderous communication, written or oral; the wrong of maliciously injuring the good name of another; slander; detraction; calumny; aspersion.

- fighting words

-

agressive words that forseeably may lead to potentially violent confrontation; in law, often considered mitigation for otherwise sanctionable behavior (fighting)

- freedom of speech

-

The right of citizens to speak, or otherwise communicate, without fear of harm or prosecution.

- prior restraint

-

censorship imposed, usually by a government, on expression before the expression actually takes place

- slander

-

a false, malicious statement (spoken or published), especially one which is injurious to a person’s reputation; the making of such a statement

Freedom of Speech

Freedom of speech in the United States is protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution and by many state constitutions as well.

Protesting for Freedom of Speech

This individual is protesting for the right to speak freely. Freedom of speech is a closely guarded liberty in American society.

The freedom of speech is not absolute. The Supreme Court of the United States has recognized several categories of speech that are excluded, and it has recognized that governments may enact reasonable time, place, or manner restrictions on speech.

Criticism of the government and advocacy of unpopular ideas that people may find distasteful or against public policy are almost always permitted. There are exceptions to these general protections. Within these limited areas, other limitations on free speech balance rights to free speech and other rights, such as rights for authors and inventors over their works and discoveries (copyright and patent), protection from imminent or potential violence against particular persons (restrictions on fighting words), or the use of untruths to harm others (slander). Distinctions are often made between speech and other acts which may have symbolic significance.

Despite the exceptions, the legal protections of the First Amendment are some of the broadest of any industrialized nation, and remain a critical, and occasionally controversial, component of American jurisprudence.

Incorporation of Freedom of Speech

Although the text of the Amendment prohibits only the United States Congress from enacting laws that abridge the freedom of speech, the Supreme Court used the incorporation doctrine in Gitlow v. New York (1925) to also prohibit state legislatures from enacting such laws.

Protected Speech

The following types of speech are protected:

- Core political speech. Political speech is the most highly guarded form of speech because of its purely expressive nature and importance to a functional republic. Restrictions placed upon core political speech must weather strict scrutiny analysis or they will be struck down.

- Commercial speech. Not wholly outside the protection of the First Amendment is speech motivated by profit, or commercial speech. Such speech still has expressive value although it is being uttered in a marketplace ordinarily regulated by the state.

- Expressive speech. The Supreme Court has recently taken the view that freedom of expression by non-speech means is also protected under the First Amendment. In 1968 (United States v. O’Brien) the Supreme Court stated that regulating non-speech can justify limitations on speech.

Type of Free Speech Restrictions

The Supreme Court has recognized several different types of laws that restrict speech, and subjects each type of law to a different level of scrutiny.

- Content-based restrictions. Restrictions that require examining the content of speech to be applied must pass strict scrutiny. Restrictions that apply to certain viewpoints but not others face the highest level of scrutiny, and are usually overturned, unless they fall into one of the court’s special exceptions.

- Time, place, or manner restrictions. Time, place, or manner restrictions must withstand intermediate scrutiny. Note that any regulations that would force speakers to change how or what they say do not fall into this category (so the government cannot restrict one medium even if it leaves open another).

- Prior restraint. If the government tries to restrain speech before it is spoken, as opposed to punishing it afterwards, it must: clearly define what’s illegal, cover the minimum speech necessary, make a quick decision, be backed up by a court, bear the burden of suing and proving the speech is illegal, and show that allowing the speech would “surely result in direct, immediate and irreparable damage to our Nation and its people. “

Exceptions to Free Speech

Certain exceptions to free speech exist, usually when it can be justified that restricting free speech is necessary to protect others from harm. These restrictions are controversial, and have often been litigated at all levels of the United States judiciary. These restrictions can include include the incitement to crime (such as falsely yelling “Fire! ” in a crowded movie theater); fighting words (which are words that are likely to induce the listener to get in a fight); true threats; obscenity; child pornography; defamation; invasion of privacy; intentional infliction of emotional distress; or certain kinds of commercial, government, or student speech. Speech related to national security, military secrets, inventions, nuclear secrets or weapons may also be restricted.

The flag of the United States is sometimes symbolically burned, often in protest of the policies of the American government, both within the country and abroad. The United States Supreme Court in Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989), and reaffirmed in U.S. v. Eichman, 496 U.S. 310 (1990), has ruled that due to the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, it is unconstitutional for a government (whether federal, state, or municipality) to prohibit the desecration of a flag, due to its status as “symbolic speech. ” However, content-neutral restrictions may still be imposed to regulate the time, place, and manner of such expression.

Free Speech Zones

The government may set up time, place, or manner restrictions to free speech. This image is a picture of the free speech zone of the 2004 Democratic National Convention.

4.2.6: Freedom of the Press

The First Amendment guarantees the freedom of the press, which includes print media as well as any other source of information or opinion.

Learning Objective

Indicate the role the Freedom of the Press in the U.S. Constitution and discuss violations to and restrictions of it

Key Points

- In a free press, those who own the press or the media have the right to print or say what they want, without persecution or any interference from the government.

- In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, the U.S. government violated its guarantee of a free press by prosecuting Civil War era newspapers and passing the Espionage and Sedition Acts of 1917 and 1918. The Supreme Court argued that a “clear and present danger” justified this suppression.

- In recent times, controversy over free press has been related to WikiLeaks, censoring of U.S. military members’ blogs, and “obscenity” censorship of TV and radio by the FCC.

Key Terms

- federal communications commission

-

A U.S. wireless regulatory authority. The FCC was established by the Communications Act of 1934 and is charged with regulating Interstate and International communications by radio, television, wire, satellite, and cable.

- Alien and Sedition Acts

-

Four bills passed in 1798 in the U.S. Congress in the aftermath of the French Revolution and during an undeclared naval war with France. They granted the federal government more power in dealing with political dissidents.

- WikiLeaks

-

WikiLeaks is an international, online, self-described not-for-profit organization that publishes submissions of secret information, news leaks, and classified media from anonymous news sources and whistleblowers.

Freedom of the Press

Freedom of the press in the United States is protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution . This clause is generally understood to prohibit the government from interfering with the printing and distribution of information or opinions. However, freedom of the press, like freedom of speech, is subject to some restrictions such as defamation law and copyright law .

Freedom of the Press Worldwide

The First Amendment to the Constitution guarantees Americans the right to a free press. This is something that many other countries do not enjoy, as this map illustrates.

Freedom of the Press

Freedom of the press is a primary civil liberty guaranteed in the First Amendment.

In Lovell v. City of Griffin, Chief Justice Hughes defined the press as, “every sort of publication which affords a vehicle of information and opinion. ” This includes everything from newspapers to blogs . The individuals, businesses, and organizations that own a means of publication are able to publish information and opinions without government interference. They cannot be compelled by the government to publish information and opinions that they disagree with. For example, the owner of a printing press cannot be required to print advertisements for a political opponent, even if the printer normally accepts commercial printing jobs.

Blogs and Free Press

Not just print media is protected under the freedom of the press; rather, all types of media, such as blogs, are protected.

Incorporation of the Freedom of the Press

In 1931, the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Near v. Minnesota used the 14th Amendment to apply the freedom of the press to the states.

Violations of the Freedom of the Press in U.S. History

In 1798, not long after the adoption of the Constitution, the governing Federalist Party attempted to stifle criticism with the Alien and Sedition Acts. These restrictions on freedom of the press proved very unpopular in the end and worked against the Federalists, leading to the party’s eventual demise and a reversal of the Acts.

In 1861, four newspapers in New York City were all given a presentment by a Grand Jury of the United States Circuit Court for “frequently encouraging the rebels by expressions of sympathy and agreement. ” This started a series of federal prosecutions of newspapers throughout the northern United States during the Civil War which printed expressions of sympathy for southern causes or criticisms of the Lincoln Administration.

The Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 imposed restrictions on free press during wartime. In Schenck v. United States (1919), the Supreme Court upheld the laws and set the “clear and present danger” standard. In other words, the Supreme Court argued that a “clear and present danger,” like wartime, justified specific free press restrictions. Congress repealed both laws in 1921. Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) revised the “clear and present danger” test to the “imminent lawless action” test, which is less restrictive.

Regulating Press and Media Content

The courts have rarely treated content-based regulation of journalism with any sympathy. In Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo (1974), the court unanimously struck down a state law requiring newspapers criticizing political candidates to publish their responses. The state claimed that the law had been passed to ensure journalistic responsibility. The Supreme Court found that freedom, but not responsibility, is mandated by the First Amendment. So, it ruled that the government may not force newspapers to publish that which they do not desire to publish.

However, content-based regulation of television and radio has been sustained by the Supreme Court in various cases. Since there are a limited number of frequencies for non-cable television and radio stations, the government licenses them to various companies. However, the Supreme Court has ruled that the problem of scarcity does not allow the raising of a First Amendment issue. The government may restrain broadcasters, but only on a content-neutral basis. In Federal Communications Commission v. Pacifica Foundation (1978), the Supreme Court upheld the Federal Communications Commission’s authority to restrict the use of “indecent” material in broadcasting.

Recent Restrictions to Freedom of the Press

Some of the recent issues in restrictions of free press include: the U.S. military censoring blogs written by military personnel; the Federal Communications Commission censoring television and radio, citing obscenity; Scientology suppressing criticism, citing freedom of religion; and censoring of WikiLeaks at the Library of Congress. There has also been some controversy over the U.S. government’s position that the media does not have the right to not reveal its sources. There are other critiques that claim the “war on terror” has been a pretext for further restrictions on free press.

4.2.7: Freedom of Assembly and Petition

The First Amendment establishes the right to assembly and the right to petition the government.

Learning Objective

Recognize the role of the Right to Petition clause in the Constitution.

Key Points

- The right to assembly guarantees that Americans have the right to peaceably come together to protest, and also have the right to come together to express and pursue collective interests.

- The right to petition gives citizens the right to appeal to the government to change its policies. It gives citizens the right to stand up for something they think is wrong, or support certain legislation, etc. that can help right those wrongs.

- The right to petition and assembly are interconnected, as they both relate to the freedom of expression. However, the right to assembly protects citizens’ rights to come together, while the right to petition protects citizens’ rights to address the government.

Key Terms

- right to petition

-

The right of citizens of the United States to freely petition the government to address particular grievances or for any reason.

- Alien and Sedition Acts

-

Four bills passed in 1798 in the U.S. Congress in the aftermath of the French Revolution and during an undeclared naval war with France. They granted the federal government more power in dealing with political dissidents.

- freedom of assembly

-

The right of citizens of the United States to freely congregate or assemble anywhere should they desire.

Right to Petition

The Petition Clause in the First Amendment states, “Congress shall make no law… abridging … the right of the people… to petition the government for a redress of grievances. ” The Petition Clause prohibits Congress from restricting the people’s right to appeal to government in favor of or against policies that affect them or about which they feel strongly, including the right to gather signatures in support of a cause and to lobby legislative bodies for or against legislation. A simplified definition of the right to petition is: the right to present requests to the government without punishment or reprisal.

Petition can be used to describe, “any nonviolent, legal means of encouraging or disapproving government action, whether directed to the judicial, executive, or legislative branch. Lobbying, letter-writing, e-mail campaigns, testifying before tribunals, filing lawsuits, supporting referenda, collecting signatures for ballot initiatives, peaceful protests and picketing: all public articulation of issues, complaints and interests designed to spur government action qualifies under the petition clause.”

The right to petition grants people not only the freedom to stand up and speak out against injustices they feel are occurring, but also grants the power to help change those injustices. It is important to note that in response to a petition from a citizen or citizens, the government is not required to actually respond to or address the issue. Under the Petition Clause, the government is only required to provide a way for citizens to petition, and a method in which they will receive the petition.

Limiting the Right to Petition

In the past, Congress has directly limited the right to petition. During the 1790s, Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, punishing opponents of the Federalist Party; the Supreme Court never ruled on the matter. In 1835, the House of Representatives adopted the Gag Rule, barring abolitionist petitions calling for the end of slavery. The Supreme Court did not hear a case related to the rule, which was abolished in 1844. During World War I, individuals petitioning for the repeal of sedition and espionage laws were punished—again, the Supreme Court did not rule on the matter.

Freedom of Assembly and Association

Freedom of Assembly, sometimes used interchangeably with the freedom of association, is the individual right to come together and collectively express, promote, pursue, and defend common interests . The right to freedom of association is recognized as a human and political right, and a civil liberty. Freedom of assembly and freedom of association may be used to distinguish between the freedom to assemble in public places and the freedom of joining an association, but both are recognized as rights under the First Amendment’s provision on freedom of assembly.

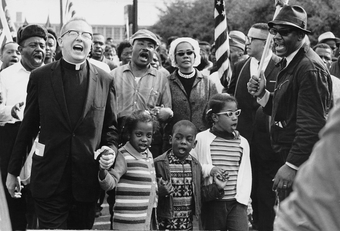

Civil Rights Movement

The right to assembly protects citizens’ rights to gather together to peacefully protest. This right was frequently exercised during the Civil Rights Movement (depicted here).

Freedom of Assembly and Right to Petition

The right of assembly was originally distinguished from the right to petition. In United States v. Cruikshank (1875), the Supreme Court held that “the right of the people peaceably to assemble for the purpose of petitioning Congress for a redress of grievances, or for anything else connected with the powers or duties of the National Government, is an attribute of national citizenship, and, as such, under protection of, and guaranteed by, the United States. ” Justice Waite’s opinion for the Court carefully distinguished the right to peaceably assemble as a secondary right, while the right to petition was labeled to be a primary right. Later cases, however, paid less attention to these distinctions. The right to petition is generally concerned with expression directed to the government seeking redress of a grievance, while the right to assemble is speaking more so to the right of Americans to gather together.

4.3: The Second Amendment: The Right to Bear Arms

4.3.1: The Second Amendment

The Second Amendment gives the right to bear arms, and can arguably apply to individuals or state militias depending on interpretation.

Learning Objective

Summarize the key provision of the Second Amendment and the two rival interpretations of its application

Key Points

- The Second Amendment is part of the US Bill of Rights.

- It gives the right to bear arms in the US, especially for the organization of state militias.

- The right to bear arms was originally seen as a check against the potential tyranny of the new Federal government as well as foreign invasion.

- In the 20th and 21st centuries, there have been conflicts between collective and individual interpretations of the amendment.

- Recent Supreme Court rulings have leaned towards the individual right to bear arms outside of a militia for other legal uses.

Key Term

- militias

-

militia or irregular army is a military force composed of ordinary citizens to provide defense, emergency law enforcement, or paramilitary service, in times of emergency without being paid a regular salary or committed to a fixed term of service.

The Second Amendment: The Right to Bear Arms

The Second Amendment to the US constitution was adopted in 1791 as part of the US Bill of Rights. At the time that the amendment was written, there was controversy around the question of state versus federal rights. Anti-federalists were concerned that the new US government would be able to maintain a standing army, which might be temptation to abuse power. The right to bear arms was seen as a check against tyranny, both domestic and foreign, and was designed to help states easily raise organized militias.

Minute Man

Ideals that helped to inspire the Second Amendment are in part symbolized by the minutemen, civilian colonists who independently organized to form well-prepared militia companies self-trained in weaponry, tactics, and military strategies from the American colonial partisan militia during the American Revolutionary War.

In the 20th century, the wording of Second Amendment has been the focus of controversy. The amendment reads “A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed. ” In some interpretations of the bill the right to bear arms is a collective right, exclusively or primarily given to states to arm a militia. Others interpret it as an individual right enabling people to keep and bear arms outside of any organization for other lawful uses.

Recent Supreme Court rulings, including the District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) have leaned towards the individual interpretation of the amendment. This ruling overturned Washington D.C.’s legislation that banned handguns in personal homes. In McDonald v. Chicago (2010), the Supreme Court ruled that Second Amendment rights could not be limited by state or local governments. However, in both cases the court has still ruled that governments can put some restrictions on gun ownership even if they can not ban it outright.

4.4: The Right to Privacy

4.4.1: The Right to Privacy

The Right to Privacy was an article that advocated for the protection of a citizen’s private matters.

Learning Objective

Examine the historical roots of the right to privacy as a legal concept

Key Points

- The right to privacy noted that it had been found necessary to define anew the exact nature and extent of the individual’s protections of person and property. It stated that the scope of such legal rights broadened over time to now include the right to enjoy life and be let alone.

- The article notes that defenses within the law of defamation, the truthfulness of the information published, or the absence of the publisher’s malice, should not be defenses.

- Although the word “privacy” is actually never used in the text of the United States Constitution, there are Constitutional limits to the government’s intrusion into individuals’ right to privacy.

Key Terms

- common law

-

A legal system that gives great precedential weight to common law on the principle that it is unfair to treat similar facts differently on different occasions.

- tort

-

A wrongful act, whether intentional or negligent, that causes an injury and can be remedied at civil law, usually through awarding damages. A delict.

- law of defamation

-

In the United States, a comprehensive discussion of what is and is not libel or slander is difficult because the definition differs between different states. Some states codify what constitutes slander and libel together into the same set of laws.

Example

- The Supreme Court recognized the 14th Amendment as providing a substantive due process right to privacy. This was first recognized by several Supreme Court Justices in Griswold v. Connecticut, a 1965 decision protecting a married couple’s rights to contraception. It was recognized again in 1973 Roe v. Wade, which invoked the right to privacy to protect a woman’s right to an abortion.

Background

United States privacy law embodies several different legal concepts. One is the invasion of privacy. It is a tort based in common law allowing an aggrieved party to bring a lawsuit against an individual who unlawfully intrudes into his or her private affairs, discloses his or her private information, publicizes him or her in a false light, or appropriates his or her name for personal gain.

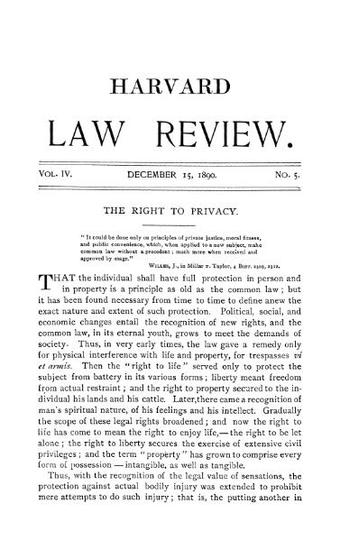

The Right to Privacy is a law review article written by Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis. It was published in the 1890 Harvard Law Review. It is one of the most influential essays in the history of American law. The article is widely regarded as the first publication in the United States to advocate a right to privacy, articulating that right primarily as a right to be left alone. It was written primarily by Louis Brandeis although credited to both men, on a suggestion of Warren based on his deep-seated abhorrence of the invasions of social privacy. William Prosser, in writing his own influential article on the privacy torts in American law, attributed the specific incident to an intrusion by journalists on a society wedding. However, in truth it was inspired by more general coverage of intimate personal lives in society columns of newspapers.

Harvard Law Review, Right to Privacy

The Right to Privacy was published at the Harvard Law Review in 15 December, 1890.

Defining the Necessity of the Right to Privacy

The authors begin the article by noting that it has been found necessary from time to time to define anew the exact nature and extent of the individual’s protections of person and property. The article states that the scope of such legal rights broadens over time — to now include the right to enjoy life — the right to be left alone.

Then the authors point out the conflicts between technology and private life. They note that recent inventions and business methods, such as instant pictures and newspaper enterprise have invaded domestic life, and numerous mechanical devices may make it difficult to enjoy private communications.

The authors discuss a number of cases involving photography, before turning to the law of trade secrets. Finally, they conclude that the law of privacy extends beyond contractual principles or property rights. Instead, they state that it is a right against the world.

Remedies and Defenses

The authors consider the possible remedies available. They also mention the necessary limitations on the doctrine, excluding matters of public or general interest, privileged communications such as judicial testimony, oral publications in the absence of special damage, and publications of information published or consented to by the individual. They pause to note that defenses within the law of defamation — the truthfulness of the information published or the absence of the publisher’s malice — should not be defenses. Finally, they propose as remedies the availability of tort actions for damages and possible injunctive relief.

Modern Tort Law

In the United States today, “invasion of privacy” is a commonly used cause of action in legal pleadings. Modern tort law includes four categories of invasion of privacy:

- Intrusion of solitude: physical or electronic intrusion into one’s private quarters

- Public disclosure of private facts: the dissemination of truthful private information which a reasonable person would find objectionable

- False light: the publication of facts which place a person in a false light, even though the facts themselves may not be defamatory

- Appropriation: the unauthorized use of a person’s name or likeness to obtain some benefits.

Constitutional basis for right to privacy

The Constitution only protects against state actors. Invasions of privacy by individuals can only be remedied under previous court decisions.

The Fourth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States ensures the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

The First Amendment protects the right to free assembly, broadening privacy rights. The Ninth Amendment declares the fact that if a right is not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution it does not mean that the government can infringe on that right. The Supreme Court recognized the 14th Amendment as providing a substantive due process right to privacy. This was first recognized by several Supreme Court Justices in Griswold v. Connecticut, a 1965 decision protecting a married couple’s rights to contraception. It was recognized again in 1973 Roe v. Wade, which invoked the right to privacy in order to protect a woman’s right to an abortion.

4.4.2: Privacy Rights and Abortion

Abortion rights are can be determined by state courts and the Supreme Court and still continues to be a highly debated right for women.

Learning Objective

Identify the legal court cases that established abortion as a right to privacy and discuss the recent cases and policies that have challenged individuals’ legal right to abortion

Key Points

- Abortion in the United States has been legal in every state since the 1973 Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade. Prior to the ruling, the legality of abortion was decided by each state; it was illegal in 30 states and legal under certain cases in 20 states.

- The Supreme Court continues to grapple with cases on the subject. On April 18, 2007 it issued a ruling in the case of Gonzales v. Carhart, involving a federal law entitled the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003, which President George W. Bush had signed into law.

- Voter opposition to these ballot initiatives has proven to be far stronger than the support, despite the fact that American citizens poll as being much more evenly divided on the issue of abortion.

Key Term

- trigger laws

-

It is a nickname for a law that is unenforceable and irrelevant in the present, but may achieve relevance and enforceability if a key change in circumstances occurs.

Example

- North Dakota HB 1572 or the Personhood of Children Act, which passed the North Dakota House of Representatives on February 18, 2009, but was later defeated in the North Dakota Senate, aimed to allocate rights to the pre-born, partially born, and if passed, would likely have been used to challenge Roe v. Wade.

Background

Abortion in the United States has been legal in every state since the 1973 Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade. Prior to the ruling, the legality of abortion was decided by each state; it was illegal in 30 states and legal under certain cases in 20 states. Roe established that the right of personal privacy includes the abortion decision, but that this right is not unqualified, and must be considered against important state interests in regulation.

Before Roe v. Wade, abortion was legal in several areas of the country, but that decision imposed a uniform framework for state legislation on the subject, and established a minimal period during which abortion must be legal (under greater or lesser degrees of restriction throughout the pregnancy). That basic framework, modified in Casey, remains nominally in place, although the effective availability of abortion varies significantly from state to state. Abortion remains one of the most controversial topics in United States culture and politics.

Later judicial decisions

In the 1992 case of Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the Court abandoned Roe’s strict trimester framework. Instead adopting the standard of undue burden for evaluating state abortion restrictions, but reemphasized the right to abortion as grounded in the general sense of liberty and privacy protected under the constitution: “Constitutional protection of the woman’s decision to terminate her pregnancy derives from the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. It declares that no State shall “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law. ” The controlling word in the cases before us is “liberty. “

The Supreme Court continues to grapple with cases on the subject. On April 18, 2007 it issued a ruling in the case of Gonzales v. Carhart, involving a federal law entitled the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003 , which President George W. Bush had signed into law. The law banned intact dilation and extraction, which opponents of abortion rights referred to as “partial-birth abortion,” and stipulated that anyone breaking the law would get a prison sentence up to 2.5 years. The United States Supreme Court upheld the 2003 ban by a narrow majority of 5-4, marking the first time the Court has allowed a ban on any type of abortion since 1973. Justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and the two recent appointees, Samuel Alito and Chief Justice John Roberts, joined the swing vote, which came from moderate justice Anthony Kennedy.

Signing the Partial-Birth Abortion ban.

The Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003 is a United States law prohibiting a form of late-term abortion that the Act calls “partial-birth abortion”, often referred to in medical literature as intact dilation and extraction.

State-by-state legal status

Various states have passed legislation on the subject of feticide. On March 6, 2006, South Dakota Governor Mike Rounds signed into law a pro-life statute, which made performing abortions a felony, and that law was subsequently repealed in a November 7, 2006 referendum. On February 27, 2006, Mississippi’s House Public Health Committee voted to approve a ban on abortion, and that bill died after the House and Senate failed to agree on compromise legislation. Several states have enacted trigger laws, which would take effect if Roe v. Wade were overturned. North Dakota HB 1572 or the Personhood of Children Act, which passed the North Dakota House of Representatives on February 18, 2009, but was later defeated in the North Dakota Senate, aimed to allocate rights to the pre-born, partially born, and if passed, would likely have been used to challenge Roe v. Wade.

Voter opposition to these ballot initiatives has proven to be far stronger than the support, despite the fact that American citizens poll as being much more evenly divided on the issue of abortion. Other states are considering personhood amendments banning abortion, some through legislative methods and others through citizen initiative campaigns. Among these states are Florida, Ohio, Georgia, Texas, and Arkansas.