15.1: Diversity in Organizations

15.1.1: The Importance of Organizational Diversity

In the modern global market, diversity is essential to generating innovative ideas, understanding local markets, and acquiring talent.

Learning Objective

Identify the advantages and challenges inherent in employing diversity within organizations

Key Points

- The business case for diversity is driven by the view that diversity brings substantial potential benefits that outweigh the organizational drawbacks and costs incurred.

- Diversity leads to a deeper level of innovation and creativity, the ability to localize to new markets, and the ability to be adaptable through access to top-level talent pools and rapid decision-making.

- In a global marketplace, organizations must be careful to adhere to all diversity-related laws and regulations. They must also be wary of mismanaging localization, ensuring that they maintain an ethical and culturally-sensitive integration with new regions.

Key Terms

- discrimination

-

Distinct treatment of an individual or group to their disadvantage; treatment or consideration based on class or category rather than individual merit; partiality; prejudice; bigotry.

- groupthink

-

A process of reasoning or decision-making by a group, especially one characterized by uncritical acceptance of or conformity to a perceived majority view.

There are many arguments for diversity in business, including the availability of talent, the enhancing of interpersonal innovation, risk avoidance, and appealing to a global customer base. The business case for diversity is driven by the view that diversity brings substantial potential benefits, such as better decision making, improved problem solving, and greater creativity and innovation, which lead to enhanced product development and more successful marketing to different types of customers.

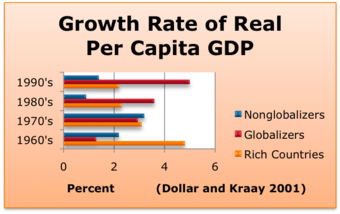

Globalizing and non-globalizing countries’ GDP growth

As noted in the chart above, globalizing organizations capture significantly better revenues in modern markets. “Nonglobalizing” countries averaged around 1.5% GDP growth in the 1990s, while globalizing countries averaged around 5% GDP growth.

Arguments for Diversity

Innovation

It is widely noted that diverse teams lead to more innovative and effective ideas and implementation. The logic behind this is relatively simple. Innovative thinking inherently requires individuals to go outside of the normal paradigms of operation, utilizing diverse perspectives to craft new and unique conclusions. A group of similar individuals with similar skills are much less likely to stumble across a series of new ideas that may lead to innovative progress. Indeed, similarity breeds groupthink, which diminishes creativity.

Localization

Some theorize that, in a global marketplace, a company that employs a diverse workforce is better able to understand the demographics of the global consumer-marketplace it serves, and is therefore better equipped to thrive in that marketplace than a company that has a more limited range of employee demographics. With the emerging markets across the globe demonstrating substantial GDP and market growth, organizations need local talent to enter the marketplace and communicate effectively. Individuals from a certain region will have a deep awareness of the needs in that region, as well as a similar culture, enabling them to add considerable value to the organizational development of strategy.

Adaptability

Finally, organizations must be technologically and culturally adaptable in the modern economy. This is crucial to reacting to competitive dynamics quickly and staying ahead of industry trends. Diversity enables unique thinking and improved decision making through a deeper and more comprehensive worldview. Diversity also enables hiring of various individuals with diverse skill sets, creating a larger talent pool. The value of this, particularly at the managerial level, is enormous. Staying quick on one’s feet (as an organization, that is) by leveraging the strength of diversity is critical to capturing opportunities and dodging external threats.

Mismanaging Diversity

While diversity has clear benefits from an organizational perspective, the threat in diversity comes from mismanagement. Due to the legal framework surrounding diversity in the workplace, the underlying threat to mismanaging diversity arises through neglect of relevant rules and regulations. Equity of pay for all employees, as well as ethical hiring practices that do not give preference one candidate over another for discriminatory reasons, are absolutely essential for managers and human resource professionals to understand. The legal ramifications of missteps in this particular arena can have high fiscal and branding costs.

15.1.2: The Inclusive Workplace

Corporate cultures that display characteristics of global awareness and inclusion capture critical benefits of workplace diversity.

Learning Objective

Identify how corporate culture can enable inclusion internally

Key Points

- Organizational culture is the collective behavior of an organization’s members and the meaning attached to that behavior. Inclusive cultures demonstrate organizational practices and goals in which those having different backgrounds are welcomed and treated equally in the organization.

- Inclusive cultures are focused on values that empower open-mindedness, promote healthy conflict, value new perspectives, and avoid judgmental attitudes.

- Creating an inclusive culture means not only stating cultural components the organization wishes to emphasize, but also working towards an ideal level of open and inclusive behavior.

- There are a number of paradigms underlined by experts in diversity management that demonstrate the linear movement from acceptance of diversity to active integration of inclusion with the corporate culture.

Key Terms

- multiculturalism

-

The characteristics of a society, city, or organization that has many different ethnic or national cultures mingling freely; political or social policies that support or encourage such coexistence.

- inclusion

-

The act of including someone or something in a group, set, or total.

- culture

-

The beliefs, values, behavior, and material objects that constitute a people’s way of life.

Corporate culture is the collective behavior of people who are part of an organization and the meanings that these people attach to their actions. Organizational culture affects the way people and groups interact with each other internally, as well as with clients and other stakeholders. Enabling an inclusive culture is highly advantageous in capturing the value of diversity.

Characteristics of Inclusion

Inclusive cultures are focused on values that empower open-mindedness, promote healthy conflict, value new perspectives, and avoid judgmental attitudes. The primary threats to an inclusive culture are groupthink, discrimination, stereotyping, and defensiveness.

Inclusive cultures

Inclusive cultures accommodate a variety of perspectives.

An inclusive culture may include a variety of tangible elements, such as acceptance and appreciation of diversity, regard for and fair treatment of each employee, respect for each employee’s contribution to the company, and equal opportunity for each employee to realize his or her full potential within the company. An organization may also adhere to a policy of multiculturalism, integrating diversity into the mission and vision statements and various other internal policies.

Paradigms of Diversity Management

With this in mind, the question of how to integrate these concepts into the organization’s culture is the primary concern for management. Creating an inclusive culture means not only stating support for it via various corporate-wide outlets, but also working towards an ideal level of open and inclusive behavior. Culture is a matter of organizational behavior because it is inherently about how people act (mostly subconsciously), and thus requires a great deal of energy and effort to alter.

The following paradigms are a result of extensive academic research by experts in diversity. The list below can be seen as a linear progression in achieving inclusion, the first being the simplest and least effective and the last being the most complex and most effective:

- Resistance paradigm: In this phase, there is a natural cultural resistance to change and equity across diverse groups. This paradigm requires extensive managerial efforts to overhaul, and corporate policies must be put into place to create a structure for corporate inclusion.

- Discrimination-and-fairness paradigm: In this phase, the organization focuses simply on adherence to social and legal expectations. The diversity team and inclusion culture primarily come out of human resource and legal professionals fulfilling minimum requirements, so they are still fairly weak.

- Access-and-legitimacy paradigm: At this phase, management has successfully elevated the culture from acceptance to active inclusion. Now the organization is looking at the overall benefits derived through diversity and utilizing them to capture maximum competitiveness.

- Learning-and-effectiveness paradigm: In this final stage, management has successfully integrated inclusion in a way that is proactive and learning-based. Groups are designed to not only capture the innovative and creative aspects of diversity, but also to share diverse skill sets and grow in efficacy through the learning process.

15.1.3: Cultural Intelligence

Cultural intelligence is the ability to display intercultural competence within a given group through adaptability and knowledge.

Learning Objective

Analyze the key components inherent in developing strong cultural competence as a manager in a diverse global economy

Key Points

- The components of cultural intelligence, from a general perspective, can be described in terms of linguistics, culture (religion, holidays, social norms, etc.), and geography (or ethnicity).

- Intercultural competence highlights the importance of grasping the varying facets of cultural identity to effectively understand other cultures.

- It is useful to apply the components of cultural intelligence to varying theoretical frameworks, such as Hofstede’s theory. Hofstede notes six measurable variables that can be applied across all cultures to illustrate predispositions.

- By combining cultural-intelligence frameworks with organizational objectives and strategy, managers are given strong resources to approach the global economy.

Key Terms

- Intercultural Competence

-

The ability to communicate effectively with people of other cultures.

- cultural quotient

-

A measurement (similar to IQ) of cultural intelligence.

- crowdsourcing

-

Delegating a task to a large, diffuse group, usually without substantial monetary compensation.

Diversity in a rapidly globalizing economy is a central field within organizational behavior and managerial development, underlining the critical importance of deriving synergy through cultural intelligence.

Defining Cultural Intelligence

The concept of cultural intelligence is exactly what it sounds like—the ability to display intercultural competence within a given group through adaptability and knowledge. Studying the components of culture, the theories pertaining to cultural dimensions and competencies, and the current initiatives in promoting these concepts are all powerful resources for managers involved in foreign assignments.

Components of Cultural Intelligence

The components of cultural intelligence, from a general perspective, can be described in terms of linguistics, culture (religion, holidays, social norms, etc.), and geography (or ethnicity). As a result, individuals interested in developing their cultural quotient (CQ) are tasked with studying each of these facets of cultural intelligence in order to accurately recognize the beliefs, values, and behaviors of the culture in which they are immersed.

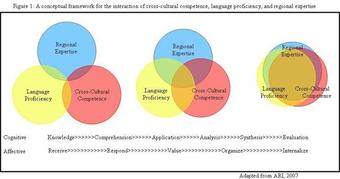

An interesting perspective on cultural intelligence is well represented in the intercultural-competence diagram, which highlights the way that each segment of cultural knowledge can create synergy when applied to the whole of cultural intelligence, where overlapping generates the highest potential CQ.

Intercultural competence

This diagram illustrates the three factors that constitute an effectively intercultural understanding for management: Regional Expertise, Language Proficiency, and Cross-Cultural Competence.

Cultural Intelligence and Cultural Framework

With these components in mind, it is useful to apply them to varying theoretical frameworks designed to illuminate the cultural dimensions and value differences across the globe.

Hofstede’s theory of cultural dimensions is particularly interesting, as it allows for a direct quantification of specific cultural values in order to measure and benchmark cultural norms in a relative and meaningful way. Hofstede’s theory was designed in the 1960s and 1970s, and has remained a relevant perspective in international business, international politics, and cross-cultural psychology. His theory notes six specific variables to measure:

- Power distance index (PDI): Simply put, this measures the level of acceptance of authority naturally present in a culture. Less powerful members must accept leadership just as more powerful individuals must bear the responsibility of leading.

- Individualism (IDV) vs. collectivism:Just as it sounds, this measurement denotes the way in which cultures tend towards group work to accomplish tasks versus individual and more independent contributions.

- Uncertainty avoidance index (UAI): Tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity is a critical element of a society’s ability to react to certain management styles and situations, providing an important measurement for understanding how much micromanagement may be useful.

- Masculinity vs. femininity: Somewhat less clear than the other factors, this identifies specific gender roles and measures the ways in which cultures reflect these roles. This is a highly debatable measurement because it innately stereotypes.

- Long-term orientation:Perhaps most critical of all to businesses is the concept of a longer- or shorter-term focus, particularly as it pertains to objectives. Understanding cultural predispositions in this regard assists in goal setting and understanding projected timelines.

- Indulgence vs. restraint: The ability of individuals within a given culture to control their desires. This is relevant to consumption, self-control, and frugality.

These theoretical variables help in analyzing what is currently being done in pursuit of higher CQ, as well as what challenges lay ahead for international managers. Understanding linguistics, cultural norms, and varying values will allow for higher localization and efficiency within global businesses.

15.1.4: Trends in Organizational Diversity

To capitalize on ethical and economic benefits, businesses are promoting increased diversity in the workplace.

Learning Objective

Analyze the social and legislative trends that define the trajectory towards higher levels of diversity and equality in the workplace

Key Points

- Diversity in the workplace creates both ethical and economic value, resulting in trends towards a more equal-opportunity workplace.

- In the 1960s, the United States implemented affirmative-action policies to enforce equal opportunity in the workplace.

- Following the implementation of various affirmative-action policies, social justice developed as an ethical norm (as opposed to a legal stipulation). This development resulted in more inclusive measures for a larger variety of groups.

- Empirical evidence of the trend toward diversity is well illustrated by gender wage gaps between males and females, which have been consistently narrowing since the early 1970s.

- In addition to its ethical bases, diversity in an increasingly global marketplace is substantially more effective and productive, allowing for higher levels of synergy.

Key Terms

- affirmative action

-

Advantages for traditionally discriminated against minority groups, with the aim of creating a more equal society through preferential access to education, employment, health care, social welfare.

- Homogeneous

-

Having a uniform make up, or the same composition throughout.

- Diversity

-

The state of being different; achieving variability.

Diversity within the workplace is a broad topic, incorporating both the need for social justice and the high potential value of employing a workforce diverse enough to compete in an increasingly global economic environment.

As a result, the workplace has undergone a number of trends that promote diversity and minimize group biases, as the ethical and economic importance of diversity is well-established. Analyzing trends in equality and value in diversity is useful for managers seeking to incorporate both.

Equality of Opportunity

Affirmative Action

The early stages of pursuing equality in the workplace arose in the 1960s, most notably with the concept of affirmative action. Affirmative action essentially establishes legal quotas—set by the U.S. government—for the number or percentage of representation by minority populations in a company’s hiring practices.

Minority populations are generally defined according to race, ethnicity, or gender. One difficulty with affirmative action is that it can encourage employers to fill quotas rather than avoid bias, potentially motivating some employers to hire specifically by race, ethnicity, or gender; hiring based upon any of these characteristics is illegal.

Social Justice

As a result of this criticism, the equal-opportunity movement evolved towards a model based more on social justice. This perspective still promotes the active seeking out of diversity in the workplace, but does so primarily based on the intrinsic value of employees with different backgrounds and skill sets.

The social-justice trend also meant a shift from a more limited viewpoint of what constituted a “minority” towards a more comprehensive one that places age, physical ability, and sexual orientation alongside traditional categories of race and gender. The social justice model of diversity is distinct from the older affirmative action in that it focuses less on employing minorities and more on the value of a diverse workforce.

Gender differences offer a strong statistical example of this trend, as male and female wage equality has been consistently trending towards equilibrium. Wage equality shows distinct improvement as a result of equal-opportunity ethics, a trend that supporters of equality hope continues toward equilibrium.

Gender wage trend

This chart illustrates that while gender wage inequality is diminishing, further efforts are necessary to promote parity.

Value of Diversity

The ethics of diversity in the workplace are rightly emphasized. The natural value achieved through varying perspectives in the workplace complements social justice well. Organizations that lack a culture inclusive of any and all potential groups generally have lower productivity and higher turnover. Promoting an environment conducive to a global and internationalized economy through diverse hiring and management practices potentially results in increased productivity.

A homogeneous workforce has a much lower capacity to achieve synergy. Upper management, recognizing the strategic value of diversity, continues to pursue the knowledge and skills necessary for a truly inclusive workplace.

15.2: Creating a Diverse Workforce

15.2.1: Considering Cultural and Interpersonal Differences

Managers capable of contemplating the varying cultural, gender, or ethnic backgrounds of their workforce can optimize collaboration.

Learning Objective

Employ cross-cultural competence to ensure interactions between diverse individuals create optimal results

Key Points

- Intercultural competence is an individual’s ability to communicate with, and adapt to, the cultural norms and expectations of each employee or customer. Competence is understanding the differences between people of different backgrounds and cultures.

- Cross-cultural competence, language proficiency, and regional expertise are three critical building blocks to attaining a high level of intercultural competence.

- Cross-cultural competence is a set of cognitive, behavioral, and motivational components that enable individuals to adapt to intercultural environments.

- Manager who are able to recognize the differences among their employees must be aware of their own cultural identity and employ empathy when dealing with differences.

- Those who achieve a high level of intercultural competency while possessing a strong understanding of their own strengths, weaknesses, and cultural identity will more effectively immerse themselves into the cultures of co-workers.

Key Terms

- predisposition

-

An intrinsic personal characteristic or susceptibility.

- Intercultural Competence

-

The ability to communicate effectively with people of other cultures.

- Immersion

-

Being completely surrounded by another culture (including language, geography, customs, etc.).

With an understanding of the high value of diversity, managers must next contemplate what differentiates employees. Managers who are capable of understanding the varying cultural, gender, or ethnic backgrounds of their workforce can optimize collaboration and minimize any friction that may arise as a result of these differences.

Intercultural competence is an individual’s ability to communicate with, and adapt to, the cultural norms and expectations of each employee or customer. This cultural competence is imperative for managers to succeed in a globalized world.

A Model of Intercultural Approach

Perspectives vary as to what constitutes intercultural understanding. The following figure highlights the three building blocks of one intercultural approach: cross-cultural competence, language proficiency, and regional expertise. This model suggests that the development of each building block allows for the largest potential crossover between the sections, and that employing them in concert provides the largest potential level of competence for an intercultural manager.

Intercultural competence

This chart illustrates the three factors that constitute an effectively intercultural understanding for management: Regional Expertise, Language Proficiency, and Cross-Cultural Competence

The blue and yellow circles in the diagram highlight the importance of understanding the local language and visiting regions to achieve immersion in a particular cultural mentality.

Still, cross-cultural competence is a relatively vague concept. The wide spectrum of academic studies that have addressed it have only served to complicate ideas about what constitutes a well-rounded cultural perspective. The U.S. Army Research Institute may have come closest to summarizing what it means to be cross-culturally competent: “A set of cognitive, behavioral, and affective/motivational components that enable individuals to effectively adapt in intercultural environments.”

Development of Intercultural Competence

Managers who are interested in developing the capacity to think about and isolate differences between people must be open to immersing themselves into as many cultures as possible.

Immersion is best achieved through interacting and communicating with people from other cultures often enough to face and overcome the intrinsic obstacles that may present themselves. These experiences serve as motivators for each individual involved. Intercultural exchange drives both manager and employee to think further about what predispositions each holds and how best to maximize the positives and minimize the negatives.

Individual Strengths in Accepting Differences

On a more individualistic note, the exercise of a few key introspective skills may also serve to lessen friction:

- Knowledge – Acquiring a thorough understanding of history, cultural norms, basic language, and religion is valuable.

- Empathy – Trying to understand the views and feelings of others from their perspective is important in all forms of management, but particularly relevant when differences in cultures are present.

- Self-confidence – Understanding personal weaknesses and difficulties in adapting to situations is important in controlling reactions.

- Cultural identity – Coming to terms with another culture requires cultural self-awareness, which creates a critical benchmark. Objectivity in this respect is highly valuable.

To attain a high level of cultural awareness, along with intercultural communication skills, requires thinking about and understanding different people and their respective cultures. Managers who pursue intercultural competency while possessing a strong understanding of their own strengths, weaknesses, and cultural identity will more effectively immerse themselves into the cultures of co-workers.

15.2.2: Building a Diverse Workforce

A diverse workforce is achieved by identifying, attracting, training, and retaining individuals through effective management.

Learning Objective

Diagram a step by step process enabling companies to effectively integrate diversity into their organizations to align with globalization and identify the processes and procedures used to on-board culturally diverse employees

Key Points

- The importance of developing strong intercultural competence is a top priority for multinational corporations.

- Attracting a diverse workforce requires a corporate structure supportive of varying backgrounds, including the availability of employees who can effectively identify with a variety of cultures.

- Diversity training allows for understanding of an individual’s cultural norms and values, a capability that must be applied in constructing effective teams with adaptable mentalities.

- In a complex global workplace, capitalizing on training investment takes the form of employee retention and effective incentive programs to maintain employee satisfaction.

- Companies that attain and retain a diverse workforce stand to capture substantial value.

- Employees with intercultural intelligence will be better prepared to establish working relationships and business partnerships globally

Key Terms

- retention

-

The act of maintaining an employee (or customer) through effectively filling that individual’s needs.

- corporate scouting

-

Seeking new talent for a business; isolating new employee potential.

As the global economy continues to evolve, the challenge of developing an efficient and synergistic cross-cultural workforce is of growing importance. Diversity in the workplace is optimally achieved through effectively identifying and attracting diverse talent, training that talent to maximize its contributions to the business, and retaining that workforce through effective management and compensation. Therefore, it is a top priority for multinational corporations to develop a strong intercultural competence in their management and apply this competence to the human resource framework.

Managing diversity

This chart illustrates the three steps necessary to manage a diverse workforce: Attracting a Diverse Workforce, Training a Diverse Workforce, and Retaining a Diverse Workforce.

Attracting a Diverse Workforce

Attracting a diverse workforce requires a corporate structure supportive of varying backgrounds and predispositions, as well as the internal resources and knowledge necessary to effectively identify with a variety of cultures. When defining the roles and responsibilities of a given position in the company, a human resources department must actively consider what they mean for the individual filling that position. Understanding what motivates and attracts a diverse workforce in this regard is critical in order to entice the appropriate talent pool.

Once the role is effectively and accurately defined by the company, there are a large number of resources specifically designed to identify diverse talent. Using technological advances such as search engines, job posting boards, and social networks is an excellent way to find people worth approaching to fill that role. Headhunters and corporate scouting initiatives are also an important attribute of a well-designed diversity-recruitment initiative.

Training a Diverse Workforce

Following the process involved in identifying talent, the managers and human resource representatives are then tasked with training various new hires from a number of different backgrounds and cultural predispositions. Diversity training is heavily dependent on identifying an individual’s cultural norms and values. This understanding must be applied in constructing effective teams and adaptable mentalities that will remain highly compatible with a complex global workplace. Not only should new hires be trained to understand and adapt to diversity, but managers should also be made aware of these cultural trends and be trained to effectively manage them.

Retaining a Diverse Workforce

Finally, retaining diverse employees is critical to the success of an international human resource department. This is particularly relevant to a global workforce, as the costs associated with recruiting and training diverse talent are high. Training new employees is one of the largest sources of selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) costs that businesses encounter. Capitalizing on this investment comes in the form of employee retention and effective incentive programs to maintain employee satisfaction.

From a general standpoint, retaining diverse employees begins with constructing a workplace conducive to variance in ethnic backgrounds and values. A homogeneous workplace environment will only cater to the dominant group, and this type of workplace will likely result in lower retention rates for diverse talent. Incorporating and localizing the workplace to best cater to the needs of minorities is therefore of central importance to managers intent on effectively filling the needs of diverse talent.

Combining these three strategies—attracting diverse talent, training a diverse workforce, and achieving high levels of retention—stands to capture substantial value for multinational organizations. Keeping this human resources framework in mind for constructing a multicultural workplace is a critical element to the success of businesses in a rapidly globalizing market.

15.2.3: Managing Organizational Diversity

Managing diversity and inclusion in organizations is a critical management responsibility in the modern, global workplace.

Learning Objective

Outline the way in which the HR framework approaches diversity in the workplace, capturing opportunity and avoiding threats.

Key Points

- Global business demands management that can work in a diverse environment, minimizing friction while capturing the value of different perspectives and skills.

- First and foremost, diversity must be defined organizationally from the top down and confirmed from the bottom up. This includes the mission and vision statements, the employee handbook, values statements, human resource policies, human resource training, and press releases.

- Following the above expressions of strategy, leaders and managers must integrate diversity in a meaningful way.

- From the diversity-management perspective, a diversity scorecard, which both identifies how diversity interacts with other long-term objectives and how observation/feedback could be implemented to assess it, is of high value to managers looking to improve their diversity management skills.

- The human resources department specifically has a great deal of responsibility in managing the overall diversity of the organization, including hiring, compensation equity, training, policy and legalities, and contracts.

Key Terms

- stereotype

-

A conventional, formulaic, and oversimplified conception, opinion, or image.

- diverse

-

Consisting of many different elements; various.

Management may encounter significant challenges in incorporating diverse perspectives in group settings, but managing this diversity in the workplace is essential to success. A team or organization’s diversity can include diversity across religion, sex, age, and race, but can also include diversity across work skills or personality types. All of these differences can affect team interactions and performance. Global business demands management that can work in a diverse environment, minimizing friction while capturing the value of different perspectives and skills.

Operating globally

Global business demands management that can work in a diverse environment.

Diversity-Alignment Management Strategies

Due to the wide variety of benefits inherent in employing a global workforce (new perspectives, innovation, localization, unique skill sets, etc.), managers must carefully attune their management strategies in a way that is inclusive and effective. There are a number of management-strategy models to consider in this pursuit.

Define Diversity

First and foremost, diversity must be defined organizationally from the top down and confirmed from the bottom up. This includes, but is not limited to, incorporating diversity initiatives into the mission and vision statements, the employee handbook, values statements, human resource policies, human resource training, and press releases. Having a separate diversity statement (similar to a mission statement) is also a good way to underline how an organization is committed to diversity. Following this process, upper management must also align resource allocation with diversity—committing time, efforts, capital, and staff to promoting it.

Establish Leadership Accountability

Following the above expressions of strategy, leaders and managers must now be held accountable. This means that management will carefully control diversity, minimizing the negative elements (stereotyping, discrimination, inequity, groupthink, etc.) while empowering the positive elements (innovative thinking, health conflict, inclusive culture, etc.). Managers must also actively work to achieve diversity in work groups, arranging assignments strategically to capture the inherent value of diversity. When failures in diversity management occur, managers must be accountable in taking corrective action.

Utilize a Diversity Scorecard

Scorecards are used in various aspects of management strategy, and are particularly useful in working both financial and nonfinancial objectives into specific business processes. From the diversity-management perspective, a diversity scorecard, which identifies both how diversity interacts with other long-term objectives and how observation/feedback could be implemented to assess it, is of high value to managers looking to improve their diversity management skills. It can help to identify the outcomes expected from integrating more diverse skills and perspectives as well as to assess the effectiveness of diversity management.

The Role of Human Resource Management

Upper management and departmental managers are not the only individuals involved in diversity management, however. The human resource department specifically has a great deal of responsibility in managing the overall diversity of the organization. Human resources can consider diversity within the following areas:

- Hiring

- Compensation equality

- Training

- Employee policies

- Legal regulations

- Ensuring accessibility of important documents (e.g., translating human resource materials into other languages so all staff can read them)

- Contracts

The role of human resources is to ensure that all employee concerns are being met and that employee problems are solved when they arise. Human resource professionals must also pursue corporate strategy and adhere to legal concerns when hiring, firing, paying, and regulating employees. This requires careful and meticulous understanding of both the legal and organizational contexts as they pertain to diversity management.

15.3: Challenges to Achieving Diversity

15.3.1: Barriers to Organizational Diversity

Companies seeking a diverse workforce face issues of assimilation into the majority group and wage equality for minorities.

Learning Objective

Identify key barriers to integrating diversity within the business environment

Key Points

- Despite various trends towards a more diverse workplace, barriers continue to limit progress. These barriers can be addressed by knowledgeable diversity management.

- Communication within teams and work groups can be a substantial challenge when there is a high variance in employee background, as differing predispositions and cultures often result in different forms of expression.

- When diverse employees do most of the acclimating, the value of having varying perspectives is diminished.

- One example of a barrier to diversity is the glass ceiling. The gap between wages and education level in males and females offers concrete evidence that diversity barriers in the workplace still affect equal opportunities.

- Understanding the barriers to effective assimilation, with a particular focus on communication and avoiding group biases, is a critical step in creating a more conducive environment.

Key Terms

- glass ceiling

-

An unwritten, uncodified barrier to further promotion or progression for a member of a specific demographic group.

- assimilation

-

The absorption of new ideas into an existing cognitive structure.

Despite various trends towards a more diverse workplace, some barriers still limit progress. Though the advantages of diversity are well established, difficulties from a managerial and organizational perspective can reduce optimal incorporation of different cultures. The implementation of a more diverse workforce faces obstacles in both the assimilation of new cultures into the majority and wage-equality and upper-level opportunities across the minority spectrum.

Communication Barriers

The challenges of assimilating a large workforce can be summarized as difficulties in communication and resistance to change from dominant groups. Avoiding miscommunication within teams and work groups can be a substantial challenge when there is a high variance in employee background, as differing predispositions and cultures often result in different forms of expression. These differences can lead to less effective teams and reduced synergy in work groups. Solving communication issues requires self-monitoring and empathy. Put simply, individuals need the presence of mind to think carefully about both themselves and their audience when working in groups.

Resistance to Change

Resistance to change is a slightly different barrier to assimilating more diversity in work groups, as it pertains more to the momentum of company culture. Diversity affects organizational norms by creating the need for flexibility and evolution towards a broader culture—a need that is sometimes met with resistance. Resistance forces minorities to bear the burden of changing to fit the existing culture, thereby limiting the initial value of having new perspectives in the first place.

In the organizational journal article “Cultural Diversity in the Workplace: The State of the Field,” Marlene G. Fine comments that “those who assimilate are denied the ability to express their genuine selves in the workplace; they are forced to repress significant parts of their lives within a social context that frames a large part of their daily encounters with other people.”

Fine expands upon this concept by pointing to the energy involved in assimilating to these situational cultures, emphasizing how minorities have less energy to deal with their actual job responsibilities as a result. Arguably the largest downside of assimilation, however, is that when diverse employees do most of the acclimating, the value of having varying perspectives is diminished.

Wage Equity

The barriers discussed so far support the idea that opportunities, particularly at the higher level, are not equally distributed. This misallocation of human resources is called the glass ceiling. The glass ceiling represents an invisible barrier to employees of minority backgrounds, one that keeps them from achieving executive positions in corporations.

The consistency of the gap between wage and education levels in males and females offers concrete evidence that the barriers to diversity in the workplace still exist. Though this gap highlights gender inequality in particular, the strength of the empirical data suggests that a glass ceiling could apply to any minority group.

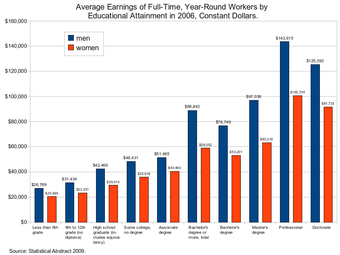

Average Earnings by Educational Attainment in 2006

Wages grouped by gender and education reveal a “glass ceiling” for women in the workplace, and the wage gap between men and women only grows as educational attainment increases. Men with doctorate degrees earned an average of $125k and women with doctorate degrees only $92k in 2006.

Developing a heterogeneous company culture, through effective communication and well-informed organizational behavior concepts, is the most effective approach to achieving a more equitable and diverse workplace. Understanding the barriers to effectively assimilating, with a particular focus on communication and avoiding group biases, is a critical step in creating a more conducive environment.

15.3.2: Challenges to Achieving Organizational Diversity

There are various challenges to achieving diversity at individual, interpersonal, and organizational levels.

Learning Objective

Recognize the difficulties involved in achieving higher levels of diversity in the workplace

Key Points

- Diversity can include elements across religion, gender, age, race, sexual orientation, disability status, and other related factors. It can also include work skills and personality types.

- Identifying which components of diversity are to be overtly emphasized and discussed, along with how to confine their definitions, is the first substantial challenge in diversity management.

- One challenge of creating diversity is the various cognitive biases individuals in the organization may have about others similar to or different from them.

- Managers encounter challenges in managing diversity as differences in cultural customs and norms emerge.

- Offsetting these challenges while growing more international is an important focal point for companies.

Key Term

- Diversity

-

The quality of being different.

There are various challenges to achieving diversity, ranging from the difficulties of defining the term to the individual, interpersonal, and organizational challenges involved in implementing diversity practices. Due to the rapidly increasing amount of diversity in varying countries and companies, achieving diversity is of extremely high business value.

Difficulty in Defining Diversity

Diversity can include elements across religion, gender, age, race, sexual orientation, disability status, and other related factors. It can also include work skills and personality types. There are many ways, therefore, that people can be categorized into different “groups,” and so identifying what categorization is most useful can be challenging.

Identifying which components of diversity should be overtly emphasized and discussed, along with how to confine their definitions, is the first substantial challenge in diversity management.

Cognitive Biases and Stereotypes

Once the definition of diversity has been decided and its different elements have been prioritized, the organization faces challenges in incorporating different groups. One challenge of creating diversity is the various cognitive biases individuals in the organization may have about others similar to or different from them. This is essentially a tendency to stereotype, which significantly narrows the worldview of the individuals within the organization. This reduces all of the potential benefits of diversity and empowers groupthink.

Homophily

Another challenge is related to a social behavior called homophily—the tendency of individuals to associate with others who are similar to them. This tendency can manifest not only in the recruitment and hiring processes within organizations, but also in the informal socialization patterns of individuals within the firm. It is quite common for individuals of similar backgrounds or beliefs to form bonds, and use these bonds to create preferential group settings. Managers must tackle this challenge through awareness, promotion of grouping based on differences, and clever delegation.

Interpersonal Miscommunication and Conflict

Another challenge faced by organizations striving to foster a more diverse workforce is the management of a diverse population. Managing diversity is more than simply acknowledging differences in people. Managers must understand the customs and cultural predispositions of their subordinates and carefully ensure they do not violate crucial cultural rules. It is the role of the managers to change the existing organizational culture to one of diversity and inclusion.

Communication, be it via language or cultural signals, is also a critical challenge in the interpersonal arena. Ensuring that all professionals (human resources, management, etc.) have access to resources which can assist in localizing or translating issues is a significant challenge in many situations. Communication issues can create complex misinterpretations, which can reduce efficiency in the workplace.

Diversity takes careful consideration to implement effectively. Offsetting the challenges involved in growing more international is an important focal point for companies.

15.3.3: Diversity Bias

Cognitive biases carried by individuals in organizations can create negative outcomes and reduce diversity of perspective.

Learning Objective

Apply the four false consensus biases commonly identified to the value of avoiding diversity risks in business.

Key Points

- Individuals face various cognitive biases that can affect organizational life. A cognitive bias is the human tendency to make systematic decisions in certain circumstances based on cognitive factors rather than evidence.

- The false-consensus bias is a cognitive bias whereby people tend to overestimate how much other people agree with them, and to assume that their own opinions, beliefs, preferences, values, and habits are normal and that others think so as well.

- Status quo bias is a cognitive bias in which the current baseline (or status quo) is taken as a reference point, and any change from that baseline is perceived as a loss.

- In-group favoritism is the tendency of individuals to provide preferential treatment to those of a similar perspective or disposition.

- A stereotype is a thought that may be adopted about specific types of individuals or certain ways of doing things, the basis of which may not reflect reality. Stereotypes can lead to misunderstandings, stifled innovation, and potentially damaging group behaviors, including discrimination.

- These biases should be actively prevented and screened for within the work environment of any multinational corporation.

Key Terms

- homophily

-

A tendency towards similarity in groups.

- bias

-

An inclination towards something; predisposition, partiality, prejudice, preference, predilection.

- diverse

-

Consisting of many different elements; various.

Individuals face various cognitive biases that can affect organizational life. A cognitive bias is the human tendency to make systematic decisions in certain circumstances based on cognitive factors rather than evidence.

Bias arises from various processes that are sometimes difficult to distinguish. These processes include information-processing shortcuts, motivational factors, and social influence. Several of these biases have especially impactful intersections with diverse groups. Examples include the false-consensus bias, status quo bias, in-group favoritism, and stereotyping.

Diversity Bias Types

False-Consensus Bias

A cognitive bias whereby people tend to overestimate how much other people agree with them, and to assume that their own opinions, beliefs, preferences, values, and habits are normal and that others think so as well.

This bias is especially prevalent in group settings where people think the collective opinion of their own group matches that of the larger population and, sometimes by extension, that those who do not agree with them are somehow defective. This can impair the integration of diverse perspectives and lead to misunderstandings.

Status Quo Bias

A cognitive bias in which the current baseline (or status quo) is taken as a reference point, and any change from that baseline is perceived as a loss. Status quo bias should be distinguished from a rational preference for the status quo, as when the current state of affairs is objectively superior to the available alternatives, or when imperfect information is a significant problem. A large body of evidence, however, shows that an irrational preference for the status quo—a status quo bias—frequently has a negative affect on decision-making.

In-Group Favoritism

A social process that may have links to cognitive biases but also to other social dynamics. This bias relies on a tendency toward homophily (the tendency of similar types of individuals to form groups), as in-group favoritism is the tendency for individuals to provide preferential treatment to those of a similar perspective or disposition. As this can include the allocation of resources, promotions and other critical organizational attributes, it poses a serious threat to inclusion (and the benefits of inclusion).

U.S. male/female wage comparison 1979–2005

Women consistently make less than men in the workplace. It is likely a result, at least in part, of in-group favoritism.

Stereotyping

Stereotyping is categorizing—in ways that may or may not accurately reflect reality—specific types of individuals or certain ways of doing things. While stereotypes do not necessarily lead to prejudice and/or discrimination, expectations and beliefs about the characteristics of members of groups perceived as different from one’s own can lead to misunderstandings, inflexibility, stifled innovation, and potentially damaging group behaviors.

Taking these biases into account with regard to the business environment highlights some of the pitfalls that must be avoided in a diverse business environment. These biases should be actively prevented and screened for within the work environment of any multinational corporation.