5.1: Individual Perceptions and Behavior

5.1.1: The Perceptual Process

Perception is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information to represent and understand the environment.

Learning Objective

Outline the internal and external factors that influence the perceptual selection process

Key Points

- The perceptual process consists of six steps: the presence of objects, observation, selection, organization, interpretation, and response.

- Perceptual selection is driven by internal (personality, motivation) and external (contrast, repetition) factors.

- Perceptual organization includes factors that influence how a person connects perceptions into wholes or patterns. These include proximity, similarity, and constancy, among others.

Key Terms

- Perception

-

That which is detected by the five senses; that which is detected within consciousness as a thought, intuition, or deduction.

- factor

-

An integral part.

Perceptual Process

The perceptual process is the sequence of psychological steps that a person uses to organize and interpret information from the outside world. The steps are:

- Objects are present in the world.

- A person observes.

- The person uses perception to select objects.

- The person organizes the perception of objects.

- The person interprets the perceptions.

- The person responds.

The selection, organization, and interpretation of perceptions can differ among different people . Therefore, when people react differently in a situation, part of their behavior can be explained by examining their perceptual process, and how their perceptions are leading to their responses.

Multistability

The Necker cube and Rubin vase can be perceived in more than one way. The vase can be seen as either a vase or two faces.

Perceptual Selection

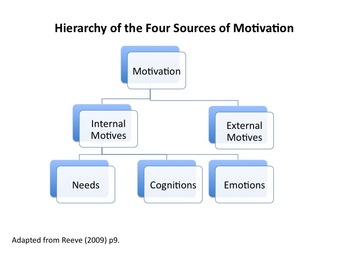

Perceptual selection is driven by internal and external factors.

Internal factors include:

- Personality – Personality traits influence how a person selects perceptions. For instance, conscientious people tend to select details and external stimuli to a greater degree.

- Motivation – People will select perceptions according to what they need in the moment. They will favor selections that they think will help them with their current needs, and be more likely to ignore what is irrelevant to their needs.

- Experience – The patterns of occurrences or associations one has learned in the past affect current perceptions. The person will select perceptions in a way that fits with what they found in the past.

External factors include:

- Size – A larger size makes it more likely an object will be selected.

- Intensity – Greater intensity, in brightness, for example, also increases perceptual selection.

- Contrast – When a perception stands clearly out against a background, there is a greater likelihood of selection.

- Motion – A moving perception is more likely to be selected.

- Repetition – Repetition increases perceptual selection.

- Novelty and familiarity – Both of these increase selection. When a perception is new, it stands out in a person’s experience. When it is familiar, it is likely to be selected because of this familiarity.

Perceptual Organization

After certain perceptions are selected, they can be organized differently. The following factors are those that determine perceptual organization:

- Figure-ground – Once perceived, objects stand out against their background. This can mean, for instance, that perceptions of something as new can stand out against the background of everything of the same type that is old.

- Perceptual grouping – Grouping is when perceptions are brought together into a pattern.

- Closure – This is the tendency to try to create wholes out of perceived parts. Sometimes this can result in error, though, when the perceiver fills in unperceived information to complete the whole.

- Proximity – Perceptions that are physically close to each other are easier to organize into a pattern or whole.

- Similarity – Similarity between perceptions promotes a tendency to group them together.

- Perceptual Constancy – This means that if an object is perceived always to be or act a certain way, the person will tend to infer that it actually is always that way.

- Perceptual Context – People will tend to organize perceptions in relation to other pertinent perceptions, and create a context out of those connections.

Each of these factors influence how the person perceives their environment, so responses to their environment can be understood by taking the perceptual process into account.

5.1.2: Cognitive Biases

Perceptual distortions, such as cognitive bias, can result in poor judgement and irrational courses of action.

Learning Objective

Analyze the complex cognitive patterns that can complicate employee perception and behavior

Key Points

- Cognitive biases are instances of evolved mental behavior that can cause deviations in judgement that produce negative consequences for an organization.

- Understanding how perception can be distorted is particularly relevant for managers because they make many decisions, and deal with many people making assessments and judgments, on a daily basis.

- Bias arises from various processes that are sometimes difficult to distinguish. These include information-processing shortcuts (heuristics), mental noise and the mind’s limited information processing capacity, emotional and moral motivations, and social influence.

- A few examples of perceptual distortions include confirmation bias, self-serving bias, causality, framing, and belief bias.

Key Terms

- heuristic

-

Experience-based techniques for problem solving, learning, and discovery. An exhaustive search is impractical, so heuristic methods are used to speed up the process of finding a satisfactory solution.

- cognitive

-

The area of mental function that deals with logic, as opposed to affective functions which deal with emotion.

A cognitive bias is a pattern of deviation in judgment that occurs in particular situations and can lead to perceptual distortion, inaccurate judgment, illogical interpretation, or what is broadly called irrationality. Implicit in the concept of a pattern of deviation is a standard of comparison with what is normative or expected; this may be the judgment of people outside those particular situations, or a set of independently verifiable facts. Essentially, there must be an objective observer to identify cognitive bias in a subjective individual.

Optical illusion

In this optical illusion all lines are actually parallel. Perceptual distortion makes them seem crooked.

Bias arises from various processes that can be difficult to distinguish. Bias is not inherently good or bad–it is pointedly subjective or contrary to reactions or decisions that one might objectively expect. Ways in which biases are derived include:

- Information-processing shortcuts (heuristics)

- Mental noise

- The mind’s limited information processing capacity

- Emotional and moral motivations

- Social influence

The notion of cognitive biases was introduced by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in 1972 and grew out of their experience of people’s innumeracy, or inability to reason intuitively with greater orders of magnitude. They and their colleagues demonstrated several replicable ways in which human judgments and decisions differ from rational choice theory. They explained these differences in terms of heuristics, rules which are simple for the brain to compute but which introduce systematic errors.

Perceptual Distortions and Management

The ways in which we distort our perception are particularly relevant for managers because they make many decisions, and deal with many people making assessments an judgments, on a daily basis. Managers must be aware of their own logical and perceptive fallacies and the biases of others. This requires a great deal of organizational behavior knowledge. A few useful perceptual distortions managers should be aware of include:

- Confirmation bias – Simply put, humans have a strong tendency to manipulate new information and facts until they match their own preconceived notions. This inappropriate confirmation allows for poor decision-making that ignores the true implications of new data.

- Self-serving bias – Another common bias is the tendency to take credit for success while passing the buck on failure. Managers must monitor this in employees and realize when they are guilty themselves. Being objective about success and failure enables growth and ensures proper accountability.

- Belief bias – Individuals often make a decision before they have all the facts. In this situation, they believe that their confidence in their decision is founded on a rational and logical assessment of the facts when it is not.

- Framing – It is quite easy to be right about everything if you carefully select the context and perspective on a given issue. Framing enables people to ignore relevant facts by narrowing down what is considered applicable to a given decision.

- Causality – Humans are pattern-matching organisms. People analyze past events to predict future outcomes. Sometimes their analysis is accurate, but sometimes it is not. It is easy to see the cause-effect relationship in completely random situations. Statistical confidence intervals are useful in mitigating this perceptive distortion.

5.1.3: Impression Management

Impression management is a goal-directed conscious or unconscious process in which people attempt to influence the perceptions of others.

Learning Objective

Outline the way in which impressions and impressions management affect management, organizations, and branding

Key Points

- Influencing others and gaining rewards, along with other motives, govern impression management from a general perspective.

- Impression management theory states that an individual or organization must establish and maintain impressions that are congruent with the perceptions they want to convey to their stakeholder groups.

- Organizations use branding and other impressions management strategies to convey a consistent and repeatable image to external and internal audiences.

- Management must also consider the impressions they make on others, both subordinates and business partners. Every organization has an image to maintain—and so does its management.

Key Term

- impression

-

The overall effect of something, e.g., on a person.

In sociology and social psychology, impression management is a goal-directed conscious or unconscious process in which people attempt to influence the perceptions of others about a person, object, or event. Impression management is performed by controlling or shaping information in social interactions. It is usually synonymous with self-presentation, in which a person tries to influence how others perceive their image. Impression management is used by communications and public relations professionals to shape an organization’s public image.

While impression management and self-presentation are often used interchangeably, some argue that they are not the same. In particular, Schlenker believed that self-presentation should be used to describe attempts to control “self-relevant” images projected in “real or imagined social interactions.” This was because people manage impressions of entities other than themselves, such as businesses, cities, and other individuals.

Application to Management

From the managerial and/or organizational frame, the basic premise is the same. Organizations put forward a self-proclaimed (and strategized and refined) organizational perception. This is most commonly referred to as brand image or brand perception. Management must ensure that all aspects of the organization conform to and fulfill the desired brand image, and communicate it to the public.

Managers must also consider the impressions they make on others, both subordinates and business partners. Managers have to ensure that they too are promoting the company brand image. Maintaining a consistent and reliable impression in a professional context that is conducive to the organizational impression is a central communicative skill managers must practice to be successful.

Impression Management Theory

Impression management theory states that any individual or organization must establish and maintain impressions that are congruent with the perceptions they want to convey to their stakeholder groups. From both a communications and public relations viewpoint, impression management encompasses ways of communicating congruence between personal or organizational goals and their intended actions in order to influence public perception.

The idea that perception is reality is the basis for this sociological and social psychology theory. Perception of an individual—a manager or employee—fundamentally shapes how the public perceives an organization and its products.

Motives and Strategies

There are several motives that govern impression management. One is instrumental: we want to influence others and gain rewards. Giving the right impression facilitates desired social and material outcomes. Social outcomes can include approval, friendship, assistance, or power, and conveying an impression of competency in the workforce. These can trigger positive material rewards like higher salaries or better working conditions.

The second motive of self-presentation is expressive. We construct an image of ourselves to claim personal identity, and present ourselves in a manner that is consistent with that image. If people feel that their ability to express themselves is restricted, they react negatively, often by becoming defiant. People resist those who seek to curtail self-presentation expressiveness by adopting many different impression management strategies. One of them is ingratiation, the use of flattery or praise to highlight positive characteristics and increase social attractiveness. Another strategy is intimidation, which is aggressively showing anger to get others to hear and obey.

Basic Factors Governing Impression Management

There are a range of factors governing impression management. Impression management occurs in all social situations because people are always aware of being observed by others. The unique characteristics of a given social situation are important: cultural norms determine the appropriateness of particular verbal and nonverbal behaviors in different situations. These behaviors and actions have to be appropriate to the culture and the audience in order to positively influence impression management.

A person’s goals are another factor governing impression management. Depending on how they want to influence their audience regarding a certain topic, presenting themselves in different ways can shape different impressions and reactions in their audience.

Self-efficacy is also important to consider; this describes whether a person is confident that s/he can convey the intended impression successfully. If they aren’t confident, the audience will be able to tell.

5.2: Personality

5.2.1: The Big Five Personality Traits

The Big Five personality traits are openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.

Learning Objective

Apply the “Big Five” personality traits identified in psychology to organizational behavior

Key Points

- The concept of the “Big Five” personality traits is taken from psychology and includes five broad domains that describe personality. The Big Five personality traits are openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.

- These five factors are assumed to represent the basic structure behind all personality traits. They were defined and described by several different researchers during multiple periods of research.

- Employees are sometimes tested on the Big Five personality traits in collaborative situations to determine what strong personality traits they can add to a group dynamic.

- Businesses need to understand their people as well as their operations and processes. Understanding the personality components that drive the employee behavior is a very useful informational data point for management.

Key Term

- neuroticism

-

The tendency to easily experience unpleasant emotions such as anger, anxiety, depression, or vulnerability.

The concept of the “Big Five” personality traits is taken from psychology and includes five broad domains that describe personality. These five personality traits are used to understand the relationship between personality and various behaviors.

These five factors are assumed to represent the basic structure behind all personality traits. These five factors were defined and described by several different researchers during multiple periods of research. However, as a result of their broad definitions, the Big Five personality traits are not nearly as powerful in predicting and explaining actual behavior as are the more numerous lower-level, specific traits.

The Five Traits

The traits are:

- Openness – Openness to experience describes a person’s degree of intellectual curiosity, creativity, and preference for novelty and variety. Some disagreement remains about how to interpret this factor, which is sometimes called intellect.

- Conscientiousness – Conscientiousness is a tendency to show self-discipline, act dutifully, and aim for achievement. Conscientiousness also refers to planning, organization, and dependability.

- Extraversion – Extraversion describes energy, positive emotions, assertiveness, sociability, talkativeness, and the tendency to seek stimulation in the company of others.

- Agreeableness – Agreeableness is the tendency to be compassionate and cooperative towards others rather than suspicious and antagonistic.

- Neuroticism – Neuroticism describes vulnerability to unpleasant emotions like anger, anxiety, depression, or vulnerability. Neuroticism also refers to an individual’s level of emotional stability and impulse control and is sometimes referred to as emotional stability.

Applicability to Organizational Behavior

When scored for individual feedback, these traits are frequently presented as percentile scores. For example, a conscientiousness rating in the 80th percentile indicates a relatively strong sense of responsibility and orderliness, whereas an extraversion rating in the 5th percentile indicates an exceptional need for solitude and quiet.

Questionnaires for the Big Five personality traits

The Big Five personality traits are typically examined through surveys and questionnaires.

Employees are sometimes tested on the Big Five personality traits in collaborative situations to determine what strong personality traits they can add to the group dynamic. Personality tests can also be part of the behavioral interview process when a company is hiring to determine an individual’s ability to act on certain personality characteristics.

Understanding its people is as important to a company as understanding its operations and processes. Understanding what personality components drive the behavior of subordinates is a highly useful informational data point for management that can be used to determine what type of assignments should be set, how motivation should be pursued, what team dynamics may arise, and how to best approach conflict and/or praise when applicable.

5.2.2: The Myers-Briggs Personality Types

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator is a commonly used personality test exploring 16 personality types.

Learning Objective

Summarize the Myers-Briggs (MBTI) personality assessment perspective and the four personality types it measures

Key Points

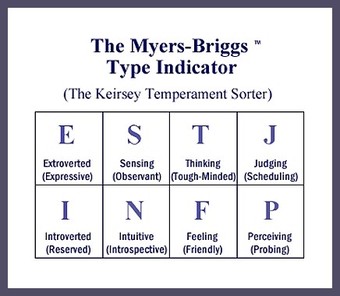

- The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) assessment is a questionnaire that measures the psychological preferences that influence how people perceive the world and make decisions. The MBTI sorts psychological differences into four opposite pairs, resulting in 16 possible personality types.

- None of these types are good or bad; however, Briggs and Myers theorized that societies as a whole naturally prefer one overall type.

- The four type preferences are Extraversion vs. Introversion, Sensing vs. Intuition, Thinking vs. Feeling, and Judgment vs. Perception. One possible classification of a personality type could be ESTJ: extraversion (E), sensing (S), thinking (T), judgment (J).

- Myers-Briggs tests are frequently used in the areas of career counseling, team building, group dynamics, professional development, marketing, leadership training, executive coaching, life coaching, personal development, marriage counseling, and workers’ compensation claims.

Key Term

- Forced-choice

-

A type of question used in psychological tests that only allows the individual to choose between one of two possible answers to each question.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) assessment is a questionnaire designed to measure the psychological preferences that shape how people perceive the world and make decisions. The original developers of the personality inventory were Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter, Isabel Briggs Myers. They began work on a questionnaire during World War II to help women who were entering the industrial workforce as part of the war effort to understand their own personality preferences and use that knowledge to identify the jobs that would be best for them. That initial questionnaire grew into the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, which was first published in 1962. The MBTI focuses on normal populations and emphasizes the value of naturally occurring differences between people.

MBTI personality types

The dimensions of the MBTI are seen here, along with temperament descriptions associated with each personality trait.

MBTI Defined

The MBTI sorts psychological differences into four opposite pairs, or dichotomies, resulting in 16 possible psychological personality types. None of these types are good or bad; however, Briggs and Myers theorized that societies as a whole naturally prefer one overall type. In the same way that writing with the left hand is hard work for a right-handed person, people find that using their opposite psychological preferences is difficult, even if they can become proficient by practicing and developing those different ways of thinking and behaving.

The 16 Personality Types

The 16 personality types are typically referred to by an abbreviation of four letters—the initial letters of each of their four type preferences. The four type preferences are: Extraversion vs. Introversion, Sensing vs. Intuition, Thinking vs. Feeling, and Judgment vs. Perception.

One possible classification of a personality type is ESTJ: extraversion (E), sensing (S), thinking (T), judgment (J). Another example is INFP: introversion (I), intuition (N), feeling (F), perception (P); and so on for all 16 possible type combinations. In this situation, extroversion means “outward turning” and introversion means “inward turning.” People who prefer judgment over perception are not necessarily more judgmental or less perceptive; they simply prefer one over the other. The most common combination from the Myers-Briggs test is ISFJ or Introvert, Sensing, Feeling, and Judgment.

The current North American English version of the Myers-Briggs test includes 93 forced-choice questions. Forced-choice means that the individual has to choose only one of two possible answers to each question. Myers-Briggs tests are frequently used in the areas of career counseling, team building, group dynamics, professional development, marketing, leadership training, executive coaching, life coaching, personal development, marriage counseling, and workers’ compensation claims.

Relevance to Management

One of the most common contexts for using the MBTI is team-building and employee personality identification. Managers are tasked with creating work groups and teams with a variety of human resources, which is a complicated social process of intuitively estimating who would complement who in group dynamics. The MBTI test is an excellent tool to measure and more accurately predict how individuals will interact in a group and what types of skills they may bring to the table.

One particularly good example is in the IE relationship. Understanding which employees in a team are naturally introverted is a useful way to ensure that a manager doesn’t miss out on these employees’ opinions just because they are naturally quiet. The manager could meet with them privately and informally—over coffee, for instance—and get their opinions. Similarly, knowing which members tend to be intuitive thinkers (NT) and which tend to understand emotions and be observant (SF) can lead the manager to give them very different tasks, though the two might work well together in a group setting since they balance each other. Management can use this tool to minimize conflict and optimize performance.

5.2.3: Other Important Trait Theories

The disposition theory, three fundamental traits, and HEXACO model of personality structure are applicable to the work place.

Learning Objective

Examine various perspectives on personality and how to measure it in the context of organizational behavior

Key Points

- Some important personality trait theories are: Gordon Allport’s dispositions, Hans Eysenck’s three fundamental traits and Michael Aston and Kibeom Lee’s six-dimensional HEXACO model of personality structure.

- Gordon Allport’s disposition theory includes cardinal traits, central traits, and secondary traits. Cardinal traits dominate an individual’s behavior, central traits are common to all individuals, and secondary traits are peripheral.

- Hans Eysenck rejected the idea that there are “tiers” of personality traits, theorizing instead that there are just three traits that describe human personality: extroversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism.

- The HEXACO model of personality identifies six factors of personality: Honesty, Emotionality, Extroversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Openness to Experience.

Key Terms

- extroversion

-

Concern with or an orientation toward others or what is outside oneself; behavior expressing such an orientation.

- trait

-

An identifying characteristic, habit, or trend.

- Disposition

-

A tendency or inclination to respond a certain way under given circumstances.

The “Big Five” describes five important personality traits, and the Myers-Briggs Test identifies a number of different personality types, but there are other important traits that have been studied by psychologists. Some of these traits include Gordon Allport’s dispositions, Hans Eysenck’s three fundamental traits, and Michael Aston and Kibeom Lee’s six dimensional HEXACO model of personality structure. All of these theories discuss important personality traits that have been studied and identified.

Allport’s Disposition Theory

Gordon Allport’s disposition theory includes cardinal traits, central traits, and secondary traits.

Gordon Allport

American psychologist Gordon Allport wrote an influential work on prejudice, The Nature of Prejudice, published in 1979.

- Cardinal trait: A trait that dominates and shapes a person’s behavior. These are the ruling passions/obsessions, such as the desire for money, fame, love, etc.

- Central trait: A general characteristic that every person has to some degree. These are the basic building blocks that shape most of our behavior, although they are not as overwhelming as cardinal traits. An example of a central trait would be honesty.

- Secondary trait: a characteristic seen only in certain circumstances (such as particular likes or dislikes that only very close friend might know). They must be included to provide a complete picture of human complexity.

Eysenck’s Extroversion and Neuroticism Theory

Hans Eysenck rejected the idea that there are “tiers” of personality traits, theorizing instead that there are just three traits that describe human personality. These traits are extroversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism. Extroversion and neuroticism provide a two-dimensional space to describe individual differences in behavior. Eysenck described these as analogous to latitude and longitude describing a point on the Earth. An individual could rate high on both neuroticism and extroversion, low on both traits, or somewhere in between. Where an individual falls on the spectrum determines her/his overall personality traits.

The third dimension, psychoticism, was added to the model in the late 1970s as a result of collaborations between Eysenck and his wife, Sybil B. G. Eysenck.

Aston and Lee’s HEXACO Model of Personality

Aston and Lee’s six-dimensional HEXACO model of personality structure is based on a lexical hypothesis that analyzes the adjectives used in different to describe personality, beginning with English. Subsequent research was conducted in other languages, including Croatian, Dutch, Filipino, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Korean, Polish, and Turkish. Comparisons of the results revealed six emergent factors. The six factors are generally named Honesty-Humility (H), Emotionality (E), Extroversion (X), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C), and Openness to Experience (O). After the adjectives that describe each of these six factors were collected using self-reports, they were distilled to four traits that describe each factor.

- Honesty-Humility (H): Sincerity, Fairness, Greed Avoidance, Modesty

- Emotionality (E): Fearfulness, Anxiety, Dependence, Sentimentality

- Extroversion (X): Social Self-Esteem, Social Boldness, Sociability, Liveliness

- Agreeableness (A): Forgivingness, Gentleness, Flexibility, Patience

- Conscientiousnes (C): Organization, Diligence, Perfectionism, Prudence

- Openness to Experience (O): Aesthetic Appreciation, Inquisitiveness, Creativity, Unconventionality

These three personality trait theories, among others, are used to describe and define personalities today in psychology and in organizational behavior.

5.3: Stress in Organizations

5.3.1: Defining Stress

Stress is defined in terms of its physical and physiological effects on a person, and can be a mental, physical, or emotional strain.

Learning Objective

Define stress within the field of organizational behavior and workplace dynamics

Key Points

- Differences in individual characteristics, such as personality and coping skills, can be very important predictors of whether certain job conditions will result in stress.

- Stress-related disorders include a broad array of conditions, including psychological disorders and other types of emotional strain, maladaptive behaviors, cognitive impairment, and various biological reactions – each of which can eventually compromise a person’s physical health.

- Categories of work demands that may cause stress include task demands, role demands, interpersonal demands, and physical demands.

Key Term

- stress

-

Mental, physical, or emotional strain caused by a demand that challenges or exceeds the individual’s coping ability.

Stress

Stress is defined in terms of how it impacts physical and psychological health; it includes mental, physical, and emotional strain. Stress occurs when a demand exceeds an individual’s coping ability and disrupts his or her psychological equilibrium. Stress occurs in the workplace when an employee perceives a situation to be too strenuous to handle, and therefore threatening to his or her well-being.

Stress

A black and white photo of a woman that captures her high level of stress.

Stress at Work

While it is generally agreed that stress occurs at work, views differ on the importance of worker characteristics versus working conditions as its primary cause. The differing viewpoints suggest different ways to prevent stress at work. Different individual characteristics, like personality and coping skills, can be very important predictors of whether certain job conditions will result in stress. In other words, what is stressful for one person may not be a problem for someone else.

Stress-related disorders encompass a broad array of conditions, including psychological disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder) and other types of emotional strain (e.g., dissatisfaction, fatigue, tension), maladaptive behaviors (e.g., aggression, substance abuse), and cognitive impairment (e.g., concentration and memory problems). Job stress is also associated with various biological reactions that may ultimately lead to compromised physical health, such as cardiovascular disease.

Categories of Work Stress

Four categories of stressors underline the different causal circumstances for stress at work:

- Task Demands – This is the sense of not knowing where a job will lead you and whether the activities and tasks will change. This uncertainty causes stress that manifests itself in feelings of lack of control, concern about career progress, and time pressures.

- Role Demands – Role conflict happens when an employee is exposed to inconsistent or difficult expectations. Examples include: interole conflict (when there are two or more expectations or separate roles for one person), intrarole conflict (varying expectations of one role), person-role conflict (ethics are challenged), and role ambiguity (confusion about their experiences in relation to the expectations of others).

- Interpersonal Demands – Examples include: emotional issues (abrasive personalities, offensive co-workers), sexual harassment (directed mostly toward women), and poor leadership (lack of management experience, poor style, cannot handle having power).

- Physical Demands – Many types of work are physically demanding, including strenuous activity, extreme working conditions, travel, exposure to hazardous materials, and working in a tight, loud office.

5.3.2: Causes of Workplace Stress

Work stress is caused by demands and pressure from both within and outside of the workplace.

Learning Objective

Evaluate the role of work conditions, economic factors, and organizational social dynamics in the experience of stress in the workplace

Key Points

- Job stress can result from interactions between the worker and the conditions of the work. This can include factors such as long work hours and an employee’s status in the organization.

- Economic factors that employees are facing in the 21st century, such as company layoffs in response to economic conditions, have been linked to increased stress levels.

- Uncertainty around the future of one’s job, lack of clarity about responsibilities, inconsistent or difficult expectations, interpersonal issues between workers, and physical demands of the work can also impact stress levels.

- Non-work demands, such as personal or home demands, can also contribute to stress both inside and outside of work.

Key Term

- stress

-

Mental, physical, or emotional strain due to a demand that exceeds an individual’s coping ability.

Work-Related Stress

Problems caused by stress have become a major concern to both employers and employees. Symptoms of stress can manifest both physiologically and psychologically. Work-related stress is typically caused by demands and pressure from either within or outside of the workplace; it can be derived from uncertainty over where the job will take the employee, inconsistent or difficult expectations, interpersonal issues, or physical demands.

Although the importance of individual differences cannot be ignored, scientific evidence suggests that certain working conditions are stressful to most people. Such evidence argues that working conditions are a key source of job stress and job redesign should be used as a primary prevention strategy.

Studies of Work-Related Stress

Large-scale surveys of working conditions—including conditions recognized as risk factors for job stress—were conducted in member states of the European Union in 1990, 1995, and 2000. Results showed a time-related trend that suggested an increase in work intensity. In 1990, the percentage of workers reporting that they worked at high speeds for at least one-quarter of their working time was 48%; this increased to 54% in 1995 and 56% in 2000. Similarly, 50% of workers reported that they worked against tight deadlines at least one-fourth of their working time in 1990; this increased to 56% in 1995 and 60% in 2000. However, no change was noted in the period from 1995 to 2000 in the percentage of workers reporting sufficient time to complete tasks (data was not collected in 1990 for this category).

A substantial percentage of Americans work very long hours. By one estimate, more than 26% of men and more than 11% of women worked 50 hours or more per week (outside of the home) in 2000. These figures represent a considerable increase over the previous three decades—especially for women. According to the Department of Labor, there has been an upward trend in hours worked among employed women, an increase in work weeks of greater than forty hours by men, and a considerable increase in combined working hours among working couples, particularly couples with young children.

Power and Stress

A person’s status in the workplace can also affect levels of stress. Stress in the workplace has the potential to affect employees of all categories, and managers as well as other kinds of workers are vulnerable to work overload. However, less powerful employees (those who have less control over their jobs) are more likely to experience stress than employees with more power. This indicates that authority is an important factor complicating the work stress environment.

Economics and Stress

Economic factors that employees are facing in the 21st century have been linked to increased stress levels as well. Researchers and social commentators have pointed out that advances in technology and communications have made companies more efficient and more productive than ever before. This increase in productivity has resulted in higher expectations and greater competition, which in turn place more stress on employees.

The following economic factors can contribute to workplace stress:

- Pressure from investors who can quickly withdraw their money from company stocks

- Lack of trade and professional unions in the workplace

- Inter-company rivalries caused by global competition

- The willingness of companies to swiftly lay off workers to cope with changing business environments

Social Interactions and Stress

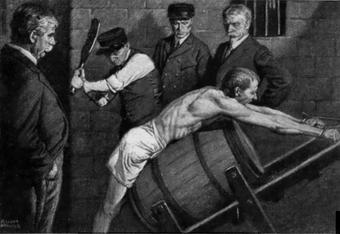

Bullying in the workplace can also contribute to stress. Workplace bullying can involve threats to an employee’s professional or personal image or status, deliberate isolation, or giving an employee excess work.

Another type of workplace bullying is known as “destabilization.” Destabilization can occur when an employee is not given credit for their work or is assigned meaningless tasks. In effect, destabilization can create a hostile work environment for employees, negatively affecting their work ethic and therefore their contributions to the organization.

Stress Outside of the Workplace

Non-work demands can create stress both inside and outside of work. Stress is inherently cumulative, and it can be difficult to separate our personal and professional stress inducers. Examples of non-work stress that can be carried into the workplace include:

- Home demands: Relationships, children, and family responsibilities can add stress that is hard to leave behind when entering the workplace. The Academy of Management Journal states that this constitutes “an individual’s lack of personal resources needed to fulfill commitments, obligations, or requirements.”

- Personal demands: Personal demands are brought on by the person when he or she takes on too many responsibilities, either inside or outside of work.

5.3.3: Consequences of Workplace Stress

Stress can impact an individual mentally and physically and so can decrease employee efficiency and job satisfaction.

Learning Objective

Recognize the potentially severe consequences of work-related stress on an individual, particularly over time

Key Points

- Problems at work are more strongly associated with health complaints than any other life stressor.

- Participation problems such as absenteeism, tardiness, strikes, and turnover take a severe toll on a company.

- Individual distress manifests in three basic forms: psychological disorders, medical illnesses, and behavioral problems.

- When individual workers within an organization suffer from a high degree of stress, overall efficiency can substantially decrease. Stressed workers will ultimately foster a negative culture and show reduce operational capabilities.

Key Terms

- stress

-

Mental, physical, or emotional strain due to a demand that exceeds an individual’s ability to cope.

- psychosomatic

-

Pertaining to physical diseases or symptoms that have psychological causes.

Stress

Symptoms of stress

Stress can manifest as various symptoms affecting one’s body, mind, behavior, and/or emotions.

Negative or overwhelming work experiences can cause a person substantial distress. Burnout, depression, and psychosomatic disorders are particularly common outcomes of work-related stress. In general, individual distress manifests in three basic forms: psychological disorders, medical illnesses, and behavioral problems.

Psychological Disorders

Psychosomatic disorders are a type of psychological disorder. They are physical problems with a psychological cause. For example, a person who is extremely anxious about public speaking might feel extremely nauseated or may find themselves unable to speak at all when faced with the prospect of presenting in front of a group. Since stress of this type is often difficult to notice, managers would benefit from carefully monitoring employee behavior for indications of discomfort or stress.

Medical Illnesses

Physiological reactions to stress can have a long-term impact on physical health. In fact, stress is one of the leading precursors to long-term health issues. Backaches, stroke, heart disease, and peptic ulcers are just a few physical ailments that can arise when a person is under too much stress.

Behavioral Problems

A person can also exhibit behavioral problems when under stress, such as aggression, substance abuse, absenteeism, poor decision making, lack of creativity, or even sabotage. A stressed worker may neglect their duties, impeding workflows and processes so that the broader organization slows down and loses time and money. Managers should keep an eye out for such behaviors as possible indicators of workplace stress.

Organizational Effects of Stress

Stress in the workplace can be, so to speak, “contagious”—low job satisfaction is often something employees will discuss with one another. If stress is not noted and addressed by management early on, team dynamics can erode, hurting the social and cultural synergies present in the organization. Ultimately, the aggressive mentality will be difficult to remedy.

Managers are in a unique position when it comes to workplace stress. As they are responsible for setting the pace, assigning tasks, and fostering the social customs that govern the work group, management must be aware of the repercussions of mismanaging and inducing stress. Managers should consistently discuss job satisfaction and professional and personal health with each of their subordinates one on one.

5.3.4: Reducing Workplace Stress

A combination of organizational change and stress management is a productive approach to preventing stress at work.

Learning Objective

Examine the various ways in which job stress can be prevented or reduced in an organization

Key Points

- Stress management refers to a wide spectrum of techniques and therapies that aim to control a person’s levels of stress, especially chronic stress, to improve everyday functioning.

- To reduce workplace stress, managers can monitor each employee’s workload to ensure it is in line with their capabilities and resources.

- Managers can also be clear and explicit about general expectations and long-term objectives to ensure there is no discrepancy between what the manager is looking for and what the employee is working toward.

- Managers must keep culture in mind when approaching issues of workplace stress. They must quickly dismantle any negative workplace culture that arises, such as bullying or harassment, and replace it with a constructive working environment.

Key Term

- stress

-

Mental, physical, or emotional strain due to a demand that exceeds an individual’s ability to cope.

Stress management refers to a wide spectrum of techniques and therapies that aim to control a person’s levels of stress, especially chronic stress, to improve everyday functioning.

Preventing Job Stress

If employees are experiencing unhealthy levels of stress, a manager can bring in an objective outsider, such as a consultant, to suggest a fresh approach. But there are many ways managers can prevent job stress in the first place. A combination of organizational change and stress management is often the most effective approach. Among the many different techniques managers can use to effectively prevent employee stress, the main underlying themes are awareness of possibly stressful elements of the workplace and intervention when necessary to mitigate any stress that does arise.

Specifically, organizations can prevent employee stress in the following ways:

Intentional Job Design

- Design jobs that provide meaning and stimulation for workers as well as opportunities for them to use their skills.

- Establish work schedules that are compatible with demands and responsibilities outside the job.

- Consider flexible schedules—many organizations allow telecommuting to reduce the pressure of being a certain place at a certain time (which enables people to better balance their personal lives).

- Monitor each employee’s workload to ensure it is in line with their capabilities and resources.

Clear and Open Communication

- Teach employees about stress awareness and promote an open dialogue.

- Avoid ambiguity at all costs—clearly define workers’ roles and responsibilities.

- Reduce uncertainty about career development and future employment prospects.

Positive Workplace Culture

- Provide opportunities for social interaction among workers.

- Watch for signs of dissatisfaction or bullying and work to combat workplace discrimination (based on race, gender, national origin, religion, or language).

Employee Accountability

- Give workers opportunities to participate in decisions and actions that affect their jobs.

- Introduce a participative leadership style and involve as many subordinates as possible in resolving stress-producing problems.

Stress Prevention Programs

St. Paul Fire and Marine Insurance Company conducted several studies on the effects of stress prevention programs in a hospital setting. Program activities included educating employees and management about workplace stress, changing hospital policies and procedures to reduce organizational sources of stress, and establishing of employee assistance programs. In one study, the frequency of medication errors declined by 50% after prevention activities were implemented in a 700-bed hospital. In a second study, there was a 70% reduction in malpractice claims among 22 hospitals that implemented stress prevention activities. In contrast, there was no reduction in claims in a matched group of 22 hospitals that did not implement stress prevention activities.

5.4: Drivers of Behavior

5.4.1: Defining Attitude

An attitude is generally defined as the way a person responds to his or her environment, either positively or negatively.

Learning Objective

Define attitude within the context of behavioral norms for employees in an organization

Key Points

- An attitude could be generally defined as a way a person responds to his or her environment, either positively or negatively. The precise definition of attitude is nonetheless a source of some discussion and debate.

- Work environment can affect a person’s attitude.

- Some attitudes are a dangerous element in the workplace, one that can spread to those closest to the employee and affect everyone’s performance.

- Attitudes are the confluence of an individual and external stimuli, and therefore everyone is in a position of responsibility to improve them (managers, employees, and organizations).

- A strong work environment is vital for an effective and efficient workplace.

Key Term

- attitude

-

Disposition or state of mind.

Overview

An attitude could be generally defined as the way a person responds to his or her environment, either positively or negatively. The definition of attitude is nonetheless a source of some discussion and debate.

When defining attitude, it is helpful to bear two useful conflicts in mind. The first is the existence of ambivalence or differences of attitude towards a given person, object, situation etc. from the same person, sometimes at the same time. This ambivalence indicates that attitude is inherently more complex than a simple sliding scale of positive and negative, and defining these axes in different ways is integral to identifying the essence of attitude. The second conflict to keep in mind is the degree of implicit versus explicit attitude, which is to say subconscious versus conscious. Indeed, people are often completely ignorant of their implicit attitudes, complicating the ability to study and interpret them accurately.

The takeaway here is to be specific when discussing attitudes, and define terms carefully. For a manager to say that somebody has attitude, or that somebody is being negative or positive about something, is vague and nonconstructive. Instead, a manager’s job is to observe and to try to pinpoint the possible causes and effects of a person’s perspective on something.

Attitudes in the Workplace

Everyone has attitudes about many things; these are not necessarily a bad thing. One aspect of employees’ attitude is the impact it can have on the people around them. People with a positive attitude can lift the spirits of their co-workers, while a person with a negative attitude can lower their spirits. Sometimes, though, this principle works in reverse, and attitudes are often more complex than positive or negative. Attitudes may affect both the employee’s work performance and the performances of co-workers .

Attitude

A person’s attitude can be influenced by his or her environment, just as a person’s attitude affects his or her environment.

Can Management Change People’s Attitudes?

Some attitudes represent a dangerous element in the workplace that can spread to those closest to the employee and affect everyone’s performance. Is it a manager’s responsibility to help change the person’s attitude? Should the employee alone be responsible? The answer is that attitudes are the confluence of an individual and external stimuli, and therefore everyone is in a position of responsibility.

Still, a manager may be able to influence a employee’s attitude if the root cause relates to work conditions or work environment. For example, employees may develop poor attitudes if they work long hours, if the company is having difficulties, or if they have relationship issues with the manager or another employee. Similarly, if employees feel believe there is little chance for advancement or that their efforts go unappreciated by the organization, they may develop a negative attitude. To the extent they are able, managers should strive to remedy these situations to encourage an effective work environment.

A strong work environment is vital for an effective and efficient workplace. Employees who are in a positive, encouraging work environment are more likely to seek solutions and remain loyal, even if the company is having financial difficulties. Even so, employees have some responsibility to alter their own attitudes. If management does everything in its power to create a positive environment and the employee refuses to participate, then managers can do little else to help. At times, attitudes are beyond the reach of the business to improve.

5.4.2: How Attitude Influences Behavior

Attitudes can positively or negatively affect a person’s behavior, regardless of whether the individual is aware of the effects.

Learning Objective

Explain how differing attitudes can have a meaningful effect on employee behavior

Key Points

- Attitudes are infectious and can affect the people that are near the person exhibiting a given attitude, which in turn can influence their behavior as well.

- Understanding different types of attitudes and their likely implications is useful in predicting how individuals’ attitudes influence their behavior.

- Daniel Katz identifies four categories of attitudes: utilitarian, knowledge, ego-defensive and value-expressive.

- Organizations can influence a employee’s attitudes and behavior by using different management strategies and by creating strong organizational environments.

- As people are affected in different ways by varying influences, an organization may want to implement multiple strategies.

Key Term

- behavior change

-

Any transformation or modification of human habits or patterns of conduct.

Individual Attitudes and Behaviors

Attitudes can positively or negatively affect a person’s behavior. A person may not always be aware of his or her attitude or the effect it is having on behavior. A person who has positive attitudes towards work and co-workers (such as contentment, friendliness, etc.) can positively influence those around them. These positive attitudes are usually manifested in a person’s behavior; people with a good attitude are active and productive and do what they can to improve the mood of those around them.

In much the same way, a person who displays negative attitudes (such as discontentment, boredom, etc.), will behave accordingly. People with these types of attitudes towards work may likewise affect those around them and behave in a manner that reduces efficiency and effectiveness.

Attitudinal Categories

Attitude and behavior interact differently based upon the attitude in question. Understanding different types of attitudes and their likely implications is useful in predicting how individuals’ attitudes may govern their behavior. Daniel Katz uses four attitude classifications:

- Utilitarian: Utilitarian refers to an individual’s attitude as derived from self or community interest. An example could be getting a raise. As a raise means more disposable income, employees will have a positive attitude about getting a raise, which may positively affect their behavior in some circumstances.

- Knowledge: Logic, or rationalizing, is another means by which people form attitudes. When an organization appeals to people’s logic and explains why it is assigning tasks or pursuing a strategy, it can generate a more positive disposition towards that task or strategy (and vice versa, if the employee does not recognize why a task is logical).

- Ego-defensive: People have a tendency to use attitudes to protect their ego, resulting in a common negative attitude. If a manager criticizes employees’ work without offering suggestions for improvement, employees may form a negative attitude and subsequently dismiss the manager as foolish in an effort to defend their work. Managers must therefore carefully manage criticism and offer solutions, not simply identify problems.

- Value-expressive: People develop central values over time. These values are not always explicit or simple. Managers should always be aware of what is important to their employees from a values perspective (that is, what do they stand for? why do they do what they do?). Having such an awareness can management to align organizational vision with individual values, thereby generating passion among the workforce.

Organizational Attitudes and Behaviors

Attitudes can be infectious and can influence the behavior of those around them. Organizations must therefore recognize that it is possible to influence a person’s attitude and, in turn, his or her behavior. A positive work environment, job satisfaction, a reward system, and a code of conduct can all help reinforce specific behaviors.

One key to altering an individual’s behavior is consistency. Fostering initiatives that influence behavior is not enough; everyone in the organization needs to be committed to the success of these initiatives. It is also important to remember that certain activities will be more effective with some people than with others. Management may want to outline a few different behavior-change strategies to have the biggest effect across the organization and take into consideration the diversity inherent in any group.

5.4.3: Defining Values

Values are guiding principles that determine individual morality and conduct.

Learning Objective

Define values in the context of organizational ethics and organizational behavior

Key Points

- Personal values are people’s internal conception of what is good, beneficial, important, useful, beautiful, desirable, constructive, etc.

- Values such as honesty, hard work, and discipline can increase an employee’s efficacy in the workplace and help them serve as a positive role model to others.

- Employees should not impose their own values on their co-workers.

- Management must take values into consideration when hiring to ensure that employee values align with the company’s, as well as those of other co-workers.

Key Term

- values

-

A collection of guiding principles; what an individual considers to be morally right and desirable in life, especially regarding personal conduct.

Overview

Personal values can be influenced by culture, tradition, and a combination of internal and external factors. Values determine what individuals find important in their daily life and help to shape their behavior in each situation they encounter. Since values often strongly influence both attitude and behavior, they serve as a kind of personal compass for employee conduct in the workplace. Values help determine whether an employee is passionate about work and the workplace, which in turn can lead to above-average returns, high employee satisfaction, strong team dynamics, and synergy.

How Are Values Formed?

Values are usually shaped by many different internal and external influences, including family, traditions, culture, and, more recently, media and the Internet. A person will filter all of these influences and meld them into a unique value set that may differ from the value sets of others in the same culture.

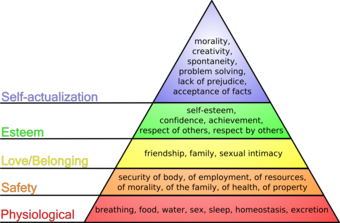

Values are thought to develop in various stages during a person’s upbringing, and they remain relatively consistent as children mature into adults. Sociologist Morris Massey outlines three critical development periods for an individual’s value system:

- Imprint period (birth to age seven): Individuals begin establishing the template for what will become their own values.

- Modeling period (ages eight to thirteen): The individual’s value template is sculpted and shaped by parents, teachers, and other people and experiences in the person’s life.

- Socialization period (ages thirteen to twenty-one): An individual fine-tunes values through personal exploration and comparing and contrasting with other people’s behavior.

Values in the Workplace

Values can strongly influence employee conduct in the workplace. If an employee values honesty, hard work, and discipline, for example, he will likely make an effort to exhibit those traits in the workplace. This person may therefore be a more efficient employee and a more positive role model to others than an employee with opposite values.

Conflict may arise, however, if an employee realizes that her co-workers do not share her values. For example, an employee who values hard work may resent co-workers who are lazy or unproductive without being reprimanded. Even so, additional conflicts can result if the employee attempts to force her own values on her co-workers.

Hiring for Values

If the managers of a business create a mission statement, they have likely decided what values they want their company to project to the public. The mission statement can help them seek out candidates whose personalities match these values, which can help reduce friction in the workplace and foster a positive work environment.

Skills-based hiring is important for efficiency and is relatively intuitive. However, hiring for values is at least as important. Because individual values have such strong attitudinal and behavioral effects, a company must hire teams of individuals whose values do not conflict with either each other’s or those of the organization.

Hard work

A strong work ethic is a personal value.

5.4.4: How Values Influence Behavior

Values influence behavior because people emulate the conduct they hold valuable.

Learning Objective

Discuss the positive relationship between meaningful corporate and employee values and behavior in the workplace

Key Points

- Values are an important element that affects individuals and how they behave towards others.

- Companies can influence a person’s behavior with codes of conduct, ethics and vision statements, ethics committees, and a punishment-and-reward system.

- A gap sometimes exists between a person’s values and behavior. Organizational strategies, such as a reward system, can close that gap.

- Culture is also largely relevant to how values shape behavior, as a given organizational culture can create camaraderie and social interdependence.

Key Term

- behavior

-

The way a living creature acts.

Overview

Values are defined as perspectives about an appropriate course of action. If a person values honesty, then he or she will strive to be honest. People who value transparency will work hard to be transparent. Values are one important element that affects individual character and behavior towards others. The relationship between values and behavior is intimate, as values create a construct for appropriate actions.

Values and Behavior in the Workplace

A work environment should strive to encourage positive values and discourage negative influences that affect behavior. All individuals possess a moral compass, defined via values, which direct how they treat others and conduct themselves. People who lack strong or ethical values may participate in negative behavior that can hurt the organization. While a company cannot do anything about the influences that shape a person’s values and behavior before hiring, the organization can try to influence employee behavior in the workplace.

Means of Encouraging or Discouraging Behavior

Training programs, codes of conduct, and ethics committees can inform employees of the types of behavior that the company finds acceptable and unacceptable. While these efforts will not necessarily not change an individual’s values, they can help them decide not to participate in unethical behavior while at work. Managers must emphasize not only an employee’s responsibilities, but also what the organization expects with respect to values and ethics. Ethics statements and vision statements are useful tools in communicating to employees what the company stands for and why.

A system of punishments and rewards can also help foster the type of values the company wants to see in its employees, essentially filtering behavior through conditioning. If people see that certain behaviors are rewarded, then they may decide to alter their behavior and in turn alter their values. In addition, a gap sometimes exists between a person’s values and behavior. This gap can stem from a conscious decision not to follow a specific value with a corresponding action. This decision can be influenced by how deeply this value affects the person’s character and by the surrounding environment.

Culture is also largely relevant to how values shape behavior, as a given organizational culture can create camaraderie and social interdependence. Conforming to the expectations and values of the broader organization is a common outcome of organizations with strong ethos and vision. Such an organization promotes passion and positive behavior in their employees. Of course, a company’s culture can work in both directions. Some industries are inherently competitive, valuing individual dominance over other individuals (for example, sales, stock trading, etc.). While some may view such a culture as objectively negative, it is subjectively useful for the organization to instill and develop these values to create certain behaviors (such as hard work and high motivation).

5.4.5: Defining Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction is the level of contentment employees feel about their work, which can affect performance.

Learning Objective

Define job satisfaction in the context of the driving forces in organizational behavior

Key Points

- Job satisfaction can be influenced by a person’s ability to complete required tasks, the level of communication in an organization, and the way management treats employees.

- Measuring job satisfaction can be challenging, as the definition of satisfaction can be different for different people.

- If an organization is concerned about employee job satisfaction, management may conduct surveys to determine what type of strategies to implement. This approach helps management define job satisfaction objectively.

- Superior-subordinate communication, or the relationship between supervisors and their direct report(s), is another important influence on job satisfaction in the workplace.

Key Term

- job satisfaction

-

The level of contentment a person feels regarding his or her work.

What Is Job Satisfaction?

Job satisfaction is the level of contentment a person feels regarding his or her job. This feeling is mainly based on an individual’s perception of satisfaction. Job satisfaction can be influenced by a person’s ability to complete required tasks, the level of communication in an organization, and the way management treats employees.

Job satisfaction falls into two levels: affective job satisfaction and cognitive job satisfaction. Affective job satisfaction is a person’s emotional feeling about the job as a whole. Cognitive job satisfaction is how satisfied employees feel concerning some aspect of their job, such as pay, hours, or benefits.

Measuring Job Satisfaction

Many organizations face challenges in accurately measuring job satisfaction, as the definition of satisfaction can differ among various people within an organization. However, most organizations realize that workers’ level of job satisfaction can impact their job performance, and thus determining metrics is crucial to creating strong efficiency.

Despite widespread belief to the contrary, studies have shown that high-performing employees do not feel satisfied with their job simply as a result of to high-level titles or increased pay. This lack of correlation is an significant concern for organizations, since studies also reveal that the implementation of positive HR practices results in financial gain for the organizations. The cost of employees is quite high, and creating satisfaction relevant to the return on this investment is paramount. Simply put: positive work environments and increased shareholder value are directly related.

Some factors of job satisfaction may rank as more important than others, depending on each worker’s needs and personal and professional goals. To create a benchmark for measuring and ultimately creating job satisfaction, managers in an organization can employ proven test methods such as the Job Descriptive Index (JDI) or the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ). These assessments help management define job satisfaction objectively.

Important Factors

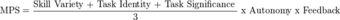

Typically, five factors can be used to measure and influence job satisfaction:

1. Pay or total compensation

2. The work itself (i.e., job specifics such as projects, responsibilities)

3. Promotion opportunities (i.e., expanded responsibilities, more prestigious title)

4. Relationship with supervisor

5. Interaction and work relationship with coworkers

Management and Communication

In addition to these five factors, one of the most important aspects of an individual’s work in a modern organization concerns communication demands that the employee encounters on the job. Demands can be characterized as a communication load: “the rate and complexity of communication inputs an individual must process in a particular time frame.” If an individual receives too many messages simultaneously, does not receive enough input on the job, or is unsuccessful in processing these inputs, the individual is more likely to become dissatisfied, aggravated, and unhappy with work, leading to a low level of job satisfaction.

Superior–subordinate communication, or the relationship between supervisors and their direct report(s), is another important influence on job satisfaction in the workplace. The way in which subordinates perceive a supervisor’s behavior can positively or negatively influence job satisfaction. Communication behavior—such as facial expression, eye contact, vocal expression, and body movement—is crucial to the superior–subordinate relationship.

5.4.6: How Job Satisfaction Influences Behavior

Job satisfaction can affect a person’s level of commitment to the organization, absenteeism, and job turnover.

Learning Objective

Discuss the way in which job satisfaction reflects upon work behaviors in an organization

Key Points

- If people are satisfied with the work they are doing, it feels less like work, thus motivating a more positive attitude and higher levels of passion.

- Individuals who are committed to their job will likely be more willing to work longer hours or take on additional responsibilities without an increase in pay.

- Satisfaction can be improved through effective management strategies. Managers are responsible for understanding what motivates employee satisfaction and creating a positive work environment conducive to it.

Key Terms

- job turnover

-

The number of employees who leave an organization of their own free will and need to be replaced.

- job description

-

An outline of the tasks and responsibilities in a post within an organization.

The Influence of Job Satisfaction on Behavior

Job satisfaction can affect a person’s level of commitment to the organization, absenteeism, and job turnover rate. It can also affect performance levels, employee willingness to participate in problem-solving activities, and the amount of effort employees put in to perform activities outside their job description. When people are satisfied with the work they are doing, then their job feels less like work and is a more enjoyable experience. Those who are satisfied in their jobs usually do not find it difficult to get up and go to work.

Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction can affect relationships.

Job satisfaction also reduces stress, which can affect job performance, mental well-being, and physical health. Stress can also affect decision-making—possibly leading to unethical or nonstrategic choices. Satisfied employees, on the other hand, maintain a more positive and carefree perspective about work. This positive outlook often spreads to co-workers and can have a positive experience on everyone’s performance. There are some indications that job satisfaction is directly tied to job performance; nonetheless, feeling less stressed can positively affect a person’s behavior.

Methods for Increasing Job Satisfaction

To determine if employees are actually satisfied with the work they do, organizations frequently conduct surveys to measure employees’ level of job satisfaction and to identify areas—on-boarding, job training, employee incentive programs, etc.—for improvement and job enrichment. Because job satisfaction varies for each individual, management teams employ several different strategies to help the majority of employees within an organization feel satisfied with their place in the company.

One proven way to enhance job satisfaction is rewarding employees based on performance and positive behavior. When employees go above and beyond their job description to complete a project or assist a colleague, their actions can be referred to as organizational citizenship behavior or OCB (see Bommer, Miles, and Grover, 2003). Bommer, Miles, and Grover state:

Social-information processing is predicated on the notion that people form ideas based on information drawn from their immediate environment, and the behavior of co-workers is a very salient component of an employee’s environment. Therefore, observing frequent citizenship episodes with in a workgroup is likely to lead to attitudes that such OCB is normal and appropriate. Consequently, the individual is likely to replicate this ‘normal’ behavior.

These positive changes in behavior show that people learn from their environments and that corporate culture plays a large part in creating job satisfaction. Managers are tasked with managing this positive culture and understanding how each employee is affected by cultural influences in the workplace. No two people are the same; this is where managers come into play. Managers must be insightful and observant, identifying what motivates high levels of job satisfaction in each individual and ensuring employees get what they need. In some ways, a manager’s customers are their subordinates. Understanding this dynamic is an important component of the role of management.

5.4.7: How Emotion and Mood Influence Behavior

Emotion and mood can affect temperament, personality, disposition, motivation, and initial perspectives and reactions.

Learning Objective

Describe the importance of employee moods and emotions on overall performance from an organizational perspective

Key Points

- The poor decision-making effects of a given mood can hinder a person’s job performance and lead to bad decisions that affect the company.

- Emotion is a subjective lens on an objective world; decision-making should discard emotion whenever possible. This is particularly important for managers, who make significant decisions on a daily basis.

- As emotion is largely a chemical balance (or imbalance) in the mind, emotions can quickly cloud judgment and complicate social interactions without the individual being consciously aware that it is happening.

Key Terms

- emotions

-

Subjective, conscious experiences that are characterized primarily by psycho-physiological expressions, biological reactions, and mental states.

- mood

-

A mental or emotional state.

Emotions in the Workplace

Emotions and mood can affect temperament, personality, disposition, and motivation. They can affect a person’s physical well-being, judgement, and perception. Emotions play a critical role in how individuals behave and react to external stimuli; they are often internalized enough for people to fail to notice when they are at work. Emotions and mood can cloud judgment and reduce rationality in decision-making.

Mood

All moods can affect judgment, perception, and physical and emotional well-being. Long-term exposure to negative moods or stressful environments can lead to illnesses such as heart disease, diabetes, and ulcers. The decision-making effects of any kind of bad mood can hinder a person’s job performance and lead to poor decisions that affect the company. In contrast, a positive mood can enhance creativity and problem solving. However, positive moods can also create false optimism and negatively influence decision making.

Emotion

Emotions are reciprocal with mood, temperament, personality, disposition, and motivation. Emotions can be influenced by hormones and neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and seratonin. Dopamine can affect a person’s energy level and mood, while seratonin can affect critical-thinking skills. As emotion is largely a chemical balance (or imbalance) in the mind, emotions can quickly cloud judgment and complicate social interactions without the individual being consciously aware that it is happening.

Plutchik Wheel

Emotions are complex and move in various directions. Modeling emotional feelings and considering their behavioral implications are useful in preventing emotions from having a negative effect on the workplace.

The implication for behavior is important for both managers and subordinates to understand. Workers must try to identify objectively when an emotional predisposition is influencing their behavior and judgement and ensure that the repercussions of the emotion are either positive or neutralized. Positive emotions can be a great thing, producing extroversion, energy and job satisfaction. However, both positive and negative emotions can distort the validity of a decision. Being overconfident, for example, can be just as dangerous as being under-confident.

Organizational Implications