5.1: Understanding Listening

5.1.1: The Importance of Listening

Listening is an active process by which we make sense of, assess, and respond to what we hear.

Learning Objective

Define active listening and list the five stages of the listening process

Key Points

- The listening process involves five stages: receiving, understanding, evaluating, remembering, and responding.

- Active listening is a particular communication technique that requires the listener to provide feedback on what he or she hears to the speaker.

- Three main degrees of active listening are repeating, paraphrasing, and reflecting.

Key Terms

- Listening

-

The active process by which we make sense of, assess, and respond to what we hear.

- active listening

-

A particular communication technique that requires the listener to provide feedback on what he or she hears to the speaker.

Example

- Fully engaged listening might involve listening to a lecture, taking notes, considering what’s being said, and asking questions.

Listening Is More than Just Hearing

Learning to Listen

Antony Gormley’s statue “Untitled [Listening],” Maygrove Peace Park

Listening is a skill of critical significance in all aspects of our lives–from maintaining our personal relationships, to getting our jobs done, to taking notes in class, to figuring out which bus to take to the airport. Regardless of how we’re engaged with listening, it’s important to understand that listening involves more than just hearing the words that are directed at us. Listening is an active process by which we make sense of, assess, and respond to what we hear.

The listening process involves five stages: receiving, understanding, evaluating, remembering, and responding. These stages will be discussed in more detail in later sections. Basically, an effective listener must hear and identify the speech sounds directed toward them, understand the message of those sounds, critically evaluate or assess that message, remember what’s been said, and respond (either verbally or nonverbally) to information they’ve received.

Effectively engaging with all five stages of the listening process lets us best gather the information we need from the world around us.

Active Listening

Active listening is a particular communication technique that requires the listener to provide feedback on what he or she hears to the speaker, by way of restating or paraphrasing what they have heard in their own words. The goal of this repetition is to confirm what the listener has heard and to confirm the understanding of both parties. The ability to actively listen demonstrates sincerity, and that nothing is being assumed or taken for granted. Active listening is most often used to improve personal relationships, reduce misunderstanding and conflicts, strengthen cooperation, and foster understanding.

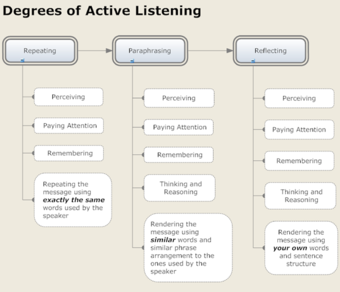

When engaging with a particular speaker, a listener can use several degrees of active listening, each resulting in a different quality of communication with the speaker. This active listening chart shows three main degrees of listening: repeating, paraphrasing, and reflecting.

Degrees of Active Listening

There are several degrees of active listening.

Active listening can also involve paying attention to the speaker’s behavior and body language. Having the ability to interpret a person’s body language lets the listener develop a more accurate understanding of the speaker’s message.

5.1.2: Listening and Critical Thinking

Critical thinking skills are essential and connected to the ability to listen effectively and process the information that one hears.

Learning Objective

Illustrate the relationship between critical thinking and listening

Key Points

- Critical thinking is the process by which people qualitatively and quantitatively assess the information they accumulate.

- Critical thinking skills include observation, interpretation, analysis, inference, evaluation, explanation, and metacognition.

- The concepts and principles of critical thinking can be applied to any context or case, including the process of listening.

- Effective listening lets people collect information in a way that promotes critical thinking and successful communication.

Key Terms

- critical thinking

-

The process by which people qualitatively and quantitatively assess the information they have accumulated.

- Metacognition

-

“Cognition about cognition”, or “knowing about knowing. ” It can take many forms, including knowledge about when and how to use particular strategies for learning or for problem solving.

Example

- The first step in thinking critically about the contents of a lecture is to listen to the lecture thoughtfully and without distraction. Using a technique such as active listening, wherein one is able to repeat or paraphrase what has been said, one will better be able to cognitively process the information to draw independent conclusions and think critically.

Critical Thinking

Roosevelt and Churchill in Conversation

Effective listening leads to better critical understanding.

One definition for critical thinking is “the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. “

In other words, critical thinking is the process by which people qualitatively and quantitatively assess the information they have accumulated, and how they in turn use that information to solve problems and forge new patterns of understanding. Critical thinking clarifies goals, examines assumptions, discerns hidden values, evaluates evidence, accomplishes actions, and assesses conclusions.

Critical thinking has many practical applications, such as formulating a workable solution to a complex personal problem, deliberating in a group setting about what course of action to take, or analyzing the assumptions and methods used in arriving at a scientific hypothesis. People use critical thinking to solve complex math problems or compare prices at the grocery store. It is a process that informs all aspects of one’s daily life, not just the time spent taking a class or writing an essay.

Critical thinking is imperative to effective communication, and thus, public speaking.

Connection of Critical Thinking to Listening

Critical thinking occurs whenever people figure out what to believe or what to do, and do so in a reasonable, reflective way. The concepts and principles of critical thinking can be applied to any context or case, but only by reflecting upon the nature of that application. Expressed in most general terms, critical thinking is “a way of taking up the problems of life. ” As such, reading, writing, speaking, and listening can all be done critically or uncritically insofar as core critical thinking skills can be applied to all of those activities. Critical thinking skills include observation, interpretation, analysis, inference, evaluation, explanation, and metacognition.

Critical thinkers are those who are able to do the following:

- Recognize problems and find workable solutions to those problems

- Understand the importance of prioritization in the hierarchy of problem solving tasks

- Gather relevant information

- Read between the lines by recognizing what is not said or stated

- Use language clearly, efficiently, and with efficacy

- Interpret data and form conclusions based on that data

- Determine the presence of lack of logical relationships

- Make sound conclusions and/or generalizations based on given data

- Test conclusions and generalizations

- Reconstruct one’s patterns of beliefs on the basis of wider experience

- Render accurate judgments about specific things and qualities in everyday life

Therefore, critical thinkers must engage in highly active listening to further their critical thinking skills. People can use critical thinking skills to understand, interpret, and assess what they hear in order to formulate appropriate reactions or responses. These skills allow people to organize the information that they hear, understand its context or relevance, recognize unstated assumptions, make logical connections between ideas, determine the truth values, and draw conclusions. Conversely, engaging in focused, effective listening also lets people collect information in a way that best promotes critical thinking and, ultimately, successful communication.

5.1.3: Causes of Poor Listening

Listening is negatively affected by low concentration, trying too hard, jumping ahead, and/or focusing on style instead of substance.

Learning Objective

Give examples of the four main barriers to effective listening

Key Points

- Low concentration can be the result of various psychological or physical situations such as visual or auditory distractions, physical discomfort, inadequate volume, lack of interest in the subject material, stress, or personal bias.

- When listeners give equal weight to everything they hear, it makes it difficult to organize and retain the information they need. When the audience is trying too hard to listen, they often cannot take in the most important information they need.

- Jumping ahead can be detrimental to the listening experience; when listening to a speaker’s message, the audience overlooks aspects of the conversation or makes judgments before all of the information is presented.

- Confirmation bias is the tendency to pick out aspects of a conversation that support one’s own preexisting beliefs and values.

- A flashy speech can actually be more detrimental to the overall success and comprehension of the message because a speech that focuses on style offers little in the way of substance.

- Recognizing obstacles ahead of time can go a long way toward overcoming them.

Key Terms

- confirmation bias

-

The tendency to pick out aspects of a conversation that support our one’s own preexisting beliefs and values.

- Vividness effect

-

The phenomenon of how vivid or highly graphic and dramatic events affect an individual’s perception of a situation.

Example

- An audience member who is trying to listen to a lecture when he is tired, there’s construction in the hallway, his pet just died, and he doesn’t like the professor or the tie he’s wearing would find it difficult or impossible to be an effective listener.

Causes of Poor Listening

Causes of Poor Listening

There are many barriers that can impede effective listening.

The act of “listening” may be affected by barriers that impede the flow of information. These barriers include distractions, an inability to prioritize information, a tendency to assume or judge based on little or no information (i.e., “jumping to conclusions), and general confusion about the topic being discussed. Listening barriers may be psychological (e.g., the listener’s emotions) or physical (e.g., noise and visual distraction). However, some of the most common barriers to effective listening include low concentration, lack of prioritization, poor judgement, and focusing on style rather than substance.

Low Concentration

Low concentration, or not paying close attention to speakers, is detrimental to effective listening. It can result from various psychological or physical situations such as visual or auditory distractions, physical discomfort, inadequate volume, lack of interest in the subject material, stress, or personal bias. Regardless of the cause, when a listener is not paying attention to a speaker’s dialogue, effective communication is significantly diminished. Both listeners and speakers should be aware of these kinds of impediments and work to eliminate or mitigate them.

When listening to speech, there is a time delay between the time a speaker utters a sentence to the moment the listener comprehends the speaker’s meaning. Normally, this happens within the span of a few seconds. If this process takes longer, the listener has to catch up to the speaker’s words if he or she continues to speak at a pace faster than the listener can comprehend. Often, it is easier for listeners to stop listening when they do not understand. Therefore, a speaker needs to know which parts of a speech may be more comprehension intensive than others, and adjust his or her speed, vocabulary, and sentence structure accordingly.

Lack of Prioritization

Just as lack of attention to detail in a conversation can lead to ineffective listening, so can focusing too much attention on the least important information. Listeners need to be able to pick up on social cues and prioritize the information they hear to identify the most important points within the context of the conversation.

Often, the information the audience needs to know is delivered along with less pertinent or irrelevant information. When listeners give equal weight to everything they hear, it makes it difficult to organize and retain the information they need. For instance, students who take notes in class must know which information to writing down within the context of an entire lecture. Writing down the lecture word for word is impossible as well as inefficient.

Poor Judgement

When listening to a speaker’s message, it is common to sometimes overlook aspects of the conversation or make judgments before all of the information is presented. Listeners often engage in confirmation bias, which is the tendency to isolate aspects of a conversation to support one’s own preexisting beliefs and values. This psychological process has a detrimental effect on listening for several reasons.

First, confirmation bias tends to cause listeners to enter the conversation before the speaker finishes her message and, thus, form opinions without first obtaining all pertinent information. Second, confirmation bias detracts from a listener’s ability to make accurate critical assessments. For example, a listener may hear something at the beginning of a speech that arouses a specific emotion. Whether anger, frustration, or anything else, this emotion could have a profound impact on the listener’s perception of the rest of the conversation.

Focusing on Style, Not Substance

The vividness effect explains how vivid or highly graphic an individual’s perception of a situation. When observing an event in person, an observer is automatically drawn toward the sensational, vivid or memorable aspects of a conversation or speech.

In the case of listening, distracting or larger-than-life elements in a speech or presentation can deflect attention away from the most important information in the conversation or presentation. These distractions can also influence the listener’s opinion. For example, if a Shakespearean professor delivered an entire lecture in an exaggerated Elizabethan accent, the class would likely not take the professor seriously, regardless of the actual academic merit of the lecture.

Cultural differences (including speakers’ accents, vocabulary, and misunderstandings due to cultural assumptions) can also obstruct the listening process. The same biases apply to the speaker’s physical appearance. To avoid this obstruction, listeners should be aware of these biases and focus on the substance, rather than the style of delivery, or the speaker’s voice and appearance.

5.2: Stages of Listening

5.2.1: The Receiving Stage

The first stage of the listening process is the receiving stage, which involves hearing and attending.

Learning Objective

Define the receiving stage of the listening process

Key Points

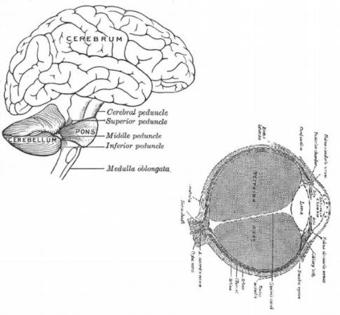

- Hearing is the physiological process of registering sound waves as they hit the eardrum.

- Attending is the process of accurately identifying particular sounds we hear as words.

- Attending also involves being able to discern breaks between words, or speech segmentation.

Key Terms

- Attending

-

The process of accurately identifying particular sounds as words.

- Hearing

-

The physiological process of registering sound waves as they hit the eardrum.

- Receiving stage

-

The first stage of the listening process, which involves hearing and attending.

The Receiving Stage

The first stage of the listening process is the receiving stage, which involves hearing and attending.

Use Your Ears!

The first stage of the listening process is receiving.

Hearing is the physiological process of registering sound waves as they hit the eardrum. As obvious as it may seem, in order to effectively gather information through listening, we must first be able to physically hear what we’re listening to. The clearer the sound, the easier the listening process becomes.

Paired with hearing, attending is the other half of the receiving stage in the listening process. Attending is the process of accurately identifying and interpreting particular sounds we hear as words. The sounds we hear have no meaning until we give them their meaning in context. Listening is an active process that constructs meaning from both verbal and nonverbal messages.

The Challenges of Reception

Listeners are often bombarded with a variety of auditory stimuli all at once, so they must differentiate which of those stimuli are speech sounds and which are not. Effective listening involves being able to focus in on speech sounds while disregarding other noise. For instance, a train passenger that hears the captain’s voice over the loudspeaker understands that the captain is speaking, then deciphers what the captain is saying despite other voices in the cabin. Another example is trying to listen to a friend tell a story while walking down a busy street. In order to best listen to what she’s saying, the listener needs to ignore the ambient street sounds.

Attending also involves being able to discern human speech, also known as “speech segmentation. “1 Identifying auditory stimuli as speech but not being able to break those speech sounds down into sentences and words would be a failure of the listening process. Discerning speech segmentation can be a more difficult activity when the listener is faced with an unfamiliar language.

5.2.2: The Understanding Stage

The understanding stage is the stage during which the listener determines the context and meanings of the words that are heard.

Learning Objective

Define the understanding stage of the listening process

Key Points

- The understanding stage is the second stage in the listening process.

- Determining the context and meaning of each word is essential to understanding a sentence.

- Understanding what we hear is essential to gathering information.

- Asking questions can help a listener better understand a speaker’s message or main point.

Key Terms

- comprehension

-

The totality of intentions or attributes, characters, marks, properties, or qualities, that the object possesses; the totality of intentions that are pertinent to the context of a given discussion.

- Understanding stage

-

The stage of listening during which the listener determines the context and meanings of the words that are heard.

Stages of Listening: The Understanding Stage

Puzzled

After receiving information through listening, the next step is understanding what you heard.

The second stage in the listening process is the understanding stage. Understanding or comprehension is “shared meaning between parties in a communication transaction” and constitutes the first step in the listening process. This is the stage during which the listener determines the context and meanings of the words he or she hears. Determining the context and meaning of individual words, as well as assigning meaning in language, is essential to understanding sentences. This, in turn, is essential to understanding a speaker’s message.

Once the listeners understands the speaker’s main point, they can begin to sort out the rest of the information they are hearing and decide where it belongs in their mental outline. For example, a political candidate listens to her opponent’s arguments to understand what policy decisions that opponent supports.

Before getting the big picture of a message, it can be difficult to focus on what the speaker is saying. Think about walking into a lecture class halfway through. You may immediately understand the words and sentences that you are hearing, but not immediately understand what the lecturer is proving or whether what you’re hearing in the moment is a main point, side note, or digression.

Understanding what we hear is a huge part of our everyday lives, particularly in terms of gathering basic information. In the office, people listen to their superiors for instructions about what they are to do. At school, students listen to teachers to learn new ideas. We listen to political candidates give policy speeches in order to determine who will get our vote. But without understanding what we hear, none of this everyday listening would relay any practical information to us.

One tactic for better understanding a speaker’s meaning is to ask questions. Asking questions allows the listener to fill in any holes he or she may have in the mental reconstruction of the speaker’s message.

5.2.3: The Evaluating Stage

The evaluating stage is the listening stage during which the listener critically assesses the information they received from the speaker.

Learning Objective

Define the evaluating stage of the listening process

Key Points

- The listener assesses the information they have gathered from the speaker both qualitatively and quantitatively.

- Evaluating allows the listener to form an opinion of what they heard.

- Evaluating is important for a listener in terms of how what she’s heard will affect her own ideas, decisions, actions, and/or beliefs.

Key Terms

- tangential

-

Merely touching, referring to a tangent, only indirectly related.

- Evaluating stage

-

The stage of the listening process during which the listener critically assesses the information they received from the speaker.

- assess

-

To determine, estimate or judge the value of; to evaluate.

The Evaluating Stage

Focus

Once you understand what you hear, you can focus in on the relevant information.

This stage of the listening process is the one during which the listener assesses the information they received, both qualitatively and quantitatively. Evaluating allows the listener to form an opinion of what they heard and, if necessary, to begin developing a response.

During the evaluating stage, the listener determines whether or not the information they heard and understood from the speaker is well constructed or disorganized, biased or unbiased, true or false, significant or insignificant. They also ascertain how and why the speaker has come up with and conveyed the message that they delivered. This may involve considerations of a speaker’s personal or professional motivations and goals. For example, a listener may determine that a co-worker’s vehement condemnation of another for jamming the copier is factually correct, but may also understand that the co-worker’s child is sick and that may be putting them on edge. A voter who listens to and understands the points made in a political candidate’s stump speech can decide whether or not those points were convincing enough to earn their vote.

The evaluating stage occurs most effectively once the listener fully understands what the speaker is trying to say. While we can, and sometimes do, form opinions of information and ideas that we don’t fully understand—or even that we misunderstand—doing so is not often ideal in the long run. Having a clear understanding of a speaker’s message allows a listener to evaluate that message without getting bogged down in ambiguities or spending unnecessary time and energy addressing points that may be tangential or otherwise nonessential.

This stage of critical analysis is important for a listener in terms of how what they heard will affect their own ideas, decisions, actions, and/or beliefs.

5.2.4: The Responding Stage

The responding stage is when the listener provides verbal and/or nonverbal reactions to what she hears.

Learning Objective

Define the responding stage of the listening process

Key Points

- The speaker looks for responses from the listener to determine if her message is being understood and/or considered.

- When a listener responds verbally to what she hears, the speaker/listener roles are reversed.

- Based on the listener’s responses, the speaker can choose to either adjust or continue with the delivery of her message.

Key Term

- Responding stage

-

The listening stage wherein the listener provides verbal and/or nonverbal reactions to what she hears.

Example

- During a training session, a new employee nods and says “okay” to indicate that she understand what her boss is telling her.

The Responding Stage

The responding stage is the stage of the listening process wherein the listener provides verbal and/or nonverbal reactions based on short- or long-term memory. Following the remembering stage, a listener can respond to what they hear either verbally or non-verbally. Nonverbal signals can include gestures such as nodding, making eye contact, tapping a pen, fidgeting, scratching or cocking their head, smiling, rolling their eyes, grimacing, or any other body language. These kinds of responses can be displayed purposefully or involuntarily. Responding verbally might involve asking a question, requesting additional information, redirecting or changing the focus of a conversation, cutting off a speaker, or repeating what a speaker has said back to her in order to verify that the received message matches the intended message.

Nonverbal responses like nodding or eye contact allow the listener to communicate their level of interest without interrupting the speaker, thereby preserving the speaker/listener roles. When a listener responds verbally to what they hear and remember—for example, with a question or a comment—the speaker/listener roles are reversed, at least momentarily.

Responding adds action to the listening process, which would otherwise be an outwardly passive process. Oftentimes, the speaker looks for verbal and nonverbal responses from the listener to determine if and how their message is being understood and/or considered. Based on the listener’s responses, the speaker can choose to either adjust or continue with the delivery of her message. For example, if a listener’s brow is furrowed and their arms are crossed, the speaker may determine that she needs to lighten their tone to better communicate their point. If a listener is smiling and nodding or asking questions, the speaker may feel that the listener is engaged and her message is being communicated effectively.

The listener

By holding her hand up to her chin, this woman is giving a nonverbal signal that she is concentrating on what the speaker (not pictured) is saying.

5.2.5: The Remembering Stage

The remembering stage occurs as the listener categorizes and retains the information she’s gathering from the speaker.

Learning Objective

Define the remembering stage of the listening process

Key Points

- Memory is essential throughout the listening process.

- Memory lets the speaker put what she hears in the context of what she’s heard before.

- Using information immediately after receiving it enhances information retention.

- Distracted or mindless listening reduces information retention.

Key Terms

- memory

-

The ability of an organism to record information about things or events with the facility of recalling them later at will.

- recall

-

Memory; the ability to remember.

- Remembering stage

-

The stage of listening wherein the listener categorizes and retains the information she’s gathering from the speaker.

The Remembering Stage

Memory

Remembering what you hear is key to effective listening.

In the listening process, the remembering stage occurs as the listener categorizes and retains the information she’s gathered from the speaker for future access. The result–memory–allows the person to record information about people, objects and events for later recall. This happens both during and after the speaker’s delivery.

Memory is essential throughout the listening process. We depend on our memory to fill in the blanks when we’re listening and to let us place what we’re hearing at the moment in the context of what we’ve heard before. If, for example, you forgot everything that you heard immediately after you heard it, you would not be able to follow along with what a speaker says, and conversations would be impossible. Moreover, a friend who expresses fear about a dog she sees on the sidewalk ahead can help you recall that the friend began the conversation with her childhood memory of being attacked by a dog.

Remembering previous information is critical to moving forward. Similarly, making associations to past remembered information can help a listener understand what she is currently hearing in a wider context. In listening to a lecture about the symptoms of depression, for example, a listener might make a connection to the description of a character in a novel that she read years before.

Using information immediately after receiving it enhances information retention and lessens the forgetting curve, or the rate at which we no longer retain information in our memory. Conversely, retention is lessened when we engage in mindless listening, and little effort is made to understand a speaker’s message.

Because everyone has different memories, the speaker and the listener may attach different meanings to the same statement. In this sense, establishing common ground in terms of context is extremely important, both for listeners and speakers.

5.3: Barriers to Listening

5.3.1: Culture

Cultural differences between listeners and speakers can create barriers to effective communication.

Learning Objective

Identify ways in which an effective communicator will approach communicating with a person from another culture

Key Points

- Cultural differences can include speakers’ accents, vocabulary, and assumptions about shared information or the roles of listeners and speakers in conversation.

- Effective communicators understand that they grow up with cultural biases for and against certain modes of communication.

- Suspending judgments, exercising empathy, and focusing on content rather than style can help overcome cultural barriers to effective communication.

Key Term

- culture

-

The arts, customs, lifestyles, background, and habits that characterize a particular society or nation. The beliefs, values, behavior and material objects that constitute a people’s way of life.

Example

- When listening to a speaker who comes from a different cultural background, work to set aside any preexisting ideas about that culture and focus on best understanding the speaker’s specific message.

Keeping an Open Mind to Cultural Differences

Handshake

Different cultures can have different methods of communication.

What defines culture? Culture certainly includes race, nationality, and ethnicity, but it goes beyond those identity markers as well. When we talk about culture, we are referring to belief systems, values, and behaviors that support a particular ideology or social arrangement. The following are various aspects of our individual identity that we use to create membership in a shared cultural identity: race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, sexual orientation, and class. Culture guides language use, appropriate forms of dress, and views of the world. The concept is broad and encompasses many areas of society such as the role of the family, the role of the individual, educational systems, employment, and gender.

Different cultures have different modes and patterns of communication that can hinder effective listening if the listener is either unfamiliar with the speaker’s patterns or holds a mistaken view about them. These kinds of cultural differences include speakers’ accents and vocabulary, as well as assumptions about shared information and the roles of listeners and speakers in conversation.

In a broad sense, we all grow up immersed in various cultures all at once—family, country, region, sexual orientation, religion, socioeconomic class, etc.—and sometimes the specifics of those cultures seem to be hard-wired into our thinking and the ways in which we communicate. Without meaning to, we may bring assumptions or judgments into a conversation that don’t actually align with the thoughts or beliefs of our conversational partner, and this can create a barrier to effective communication.

Effective communicators understand that they grow up with cultural biases for and against certain modes of communication. Because of this, an open-minded listener will work hard to focus on what the speaker is actually saying regardless of how they’re saying it. Cultural filters and frameworks may be useful later in an analysis of what someone said, but the starting point of effective listening should be to understand the perspective of the speaker as fully as possible.

Maintaining this kind of cultural sensitivity requires some basics of open-minded listening: suspending judgment and employing empathy whenever possible. By meeting the speaker on his or her own grounds and taking care to focus on the content rather than the style of the communication, we can best assure more effective understanding.

5.3.2: Gender

All of us can and do speak the language of multiple gender cultures, and we can use this knowledge to communicate effectively.

Learning Objective

Distinguish between communicating in a feminine style with communicating in a masculine style

Key Points

- As a social construct, gender is learned, symbolic, and dynamic.

- Starting in childhood, girls and boys are generally socialized to belong to distinct cultures and thus, speak in ways particular to their own gender’s rules and norms.

- For those socialized in a feminine community, the purpose of communication is to create and foster relational connections with other people.

- The goal for typically masculine communication is to establish individuality.

Key Term

- gender

-

The socio-cultural phenomenon of the division of people into various categories, such as “male” and “female,” with each having associated clothing, roles, stereotypes, etc.

Example

- When addressing an audience composed primarily of women versus one composed mostly of men, a political candidate may alter her communicative style to be more or less direct or responsive while still communicating the same information.

Gender and Culture

Invisible Couple

Differences in gender communication styles can sometimes lead to less effective communication.

In our society, we often use the gendered terms “women” and “men” instead of “male” and “female. ” What’s the difference between these two sets of terms? One pair refers to the biological categories of male and female. The other pair, men and women, refers to what are now generally regarded as socially constructed concepts that convey the contextually fluid cultural ideals or values of masculinity and femininity. Gender exists on a continuum because feminine males and masculine females are not only possible but common, and the varying degrees of masculinity and femininity we see (and embody ourselves) are often separate from sexual orientation or preference. In other words, as a social construct, gender is learned, symbolic, and dynamic.

Gender and Speech

Starting in childhood, girls and boys are generally socialized to belong to distinct cultures and thus, speak in ways particular to their own gender’s rules and norms (Johnson, 2000; Tannen 1986, 1990, 1995). This pattern of gendered socialization continues throughout our lives. As we’ve previously discussed, culturally diverse ways of speaking can cause miscommunication between members of each culture or speech community. As such, men and women often interpret the same conversation differently.

“Masculine” and “Feminine” Communication Styles

For those socialized in a feminine community, the purpose of communication is to create and foster relational connections with other people (Johnson, 2000; Wood, 2005). On the other hand, the goal for typically masculine communication is to establish individuality. This is done in a number of ways, such as indicating independence, showing control, and entertaining or performing for others.

When the goal is connection, members of a speech community are likely to engage in the following six strategies–equity, support, conversational “maintenance work,” responsiveness, a personal style, and tentativeness. When the goal is independence, on the other hand, members of this speech community are likely to communicate in ways that exhibit knowledge, refrain from personal disclosure, are abstract, are focused on instrumentality, demonstrate conversational command, are direct and assertive, and are less responsive.

All of us are capable of speaking, and do speak, the language of multiple gender cultures. Again, this is one of the reasons it is important to make a distinction between gender and sex. Both men and women may make conscious choices to speak more directly and abstractly at work, but more personal at home. Such strategic choices indicate that we can use our knowledge about various communication styles or options to make us successful in many different contexts.

As with other cultural differences, when listening to a speaker who is communicating in a particularly gendered style, try to focus on the content of the message while suspending judgment and exercising empathy.

5.3.3: Technology

Technology can assist the audience with listening, but can also be a distraction at the same time.

Learning Objective

Identify methods for avoiding technological distractions

Key Points

- Technology can help the audience listen to the speech’s message by making them physically able to hear the speaker’s words, such as through electronic amplification.

- However, malfunctioning technological equipment can disrupt the listening process.

- Personal electronics like laptops and cell phones can distract listeners from a speaker, particularly when used by audience members during the presentation.

- Do not be afraid to do a test run of any and all technology that will be used during the presentation to ensure it works smoothly when the time comes.

- Before the beginning of the speech, both the speaker and the audience should silence their cell phones or other noise-making devices.

Key Term

- technology

-

A device, material, or sequence of mathematical coded electronic instructions created by a person’s mind that is built, assembled, or produced and which is not part of the natural world.

Example

- To most effectively listen to a lecture, try turning off your cell phone and Internet connection to avoid potential distractions.

Technological Distractions

Lasers

If a speaker uses technology, they must get their message across without distracting the audience.

Everyone has experienced the benefits technology can provide to the listening experience. Hearing aid technology can help those who are hard of hearing more easily engage in a conversation or listen to a lecture. Electronic presentations can incorporate photographs, sounds, charts, guided outlines, and other features to help maintain audience attention and clarify or demonstrate complicated ideas. An engaged audience member is more likely to pay attention to the material and therefore listen more actively to a presentation.

When not used properly, however, technology can become a barrier to effective listening. Poor or outdated equipment can malfunction, causing disruptions to the listening process. If a conversation is taking place via an electronic medium, problems with technology (like a buzzing phone line or slow Internet connection) can likewise limit communication. In a non-virtual setting, excessive or unnecessary audio/visual components to a technological presentation can become distracting, particularly if they are directly related to the message being communicated by the person making the presentation.

Beyond technology being utilized by the presented, technology used by the listener can also hinder effective listening. Taking lecture notes on a laptop is convenient, but it is also convenient to check Facebook or the latest sports scores. Cell phones and tablets can provide similar distractions. If someone in the audience is talking or texting during the speech, technology becomes a major distraction for everyone involved.

Ultimately, the onus lies with both the speaker and the listener to anticipate potential technological problems or distractions to the listening process, and to do what they can to eliminate or mitigate their effects. Technology should simplify communication, not make it more complicated.

Speakers can avoid distractions caused by technology by doing the following:

- Before the presentation, the speaker should silence his or her cell phone or any other device that might make noise and provide an interruption.

- The audience should to do the same. The speaker has the right to request that the audience comply with his or her desire to have a distraction-free environment.

- If using technology as part of the presentation, the speaker should do a test run to make sure that everything is set up properly to avoid malfunction later during the speech.

- If possible, the speaker should do a sound check. Amplified or not, at the beginning of the speech, the speaker should ask, “Can you hear me in the back? ” or something to that effect.

- The speech should not include too many sources of visual stimulation such as visual aids, PowerPoints, charts, laser pointers, etc. This can actually cause a message overload for the audience as they try to divide their attention between what they hear and what they see.

5.4: Enhancing Your Listening

5.4.1: Be a Serious Listener: Resist Distractions and Listen Actively

Resisting distractions and listening actively are two ways to become a more effective listener.

Learning Objective

Explain how resisting distractions and listening actively can make you a more effective listener

Key Points

- Distractions can be internal or external. External distractions include auditory, visual, or physical noise. Internal distractions may be psychological or emotional.

- In order to best focus in on a speaker’s message, try to eliminate as many distractions as possible.

- Active listening is a communication technique that requires the listener to feed back what they hear to the speaker.

- Active listening also involves observing and assessing the speaker’s behavior and body language.

Key Term

- active listening

-

A particular communication technique that requires the listener to provide feedback on what he or she hears to the speaker.

Example

- To best listen to Troy, Penelope turned off the television and her cell phone, let him speak his mind while noticing his crossed arms and frown, then verified what she’d heard him say by re-stating it and also mentioning that he seemed a little unhappy about the situation.

Resisting Distraction

Distractions Are Everywhere

Learning how to tune out distractions enables people to be better listeners.

Distractions can come in all shapes and sizes. To be serious, effective listeners, people must learn how to resist the distractions that cross their path so they can better focus in on what they are trying to hear. Distractions and noise come in two broad types: internal and external.

External distractions often come in the form of physical noise in the physical environment. Auditory and visual distractions are often the most easily identifiable types of external distractions. Loud or extraneous noises can inhibit effective listening, as can unnecessary or excessive images. Think about trying to have a meaningful conversation with a friend while someone else is watching an action movie in the same room. Pretty impossible, right?

Internal distractions often refer to psychological and emotional noise. Distractions can also originate internally or can be physical responses to the environment. Feeling hungry, upset, or physically uncomfortable can be just as detrimental to effective listening as extraneous things in the physical environment. If a speaker is nervous about presenting a speech, he or she may have a litany of negative thoughts in his or her inner monologue, or the “little voice in your head. ” Internal distractions also occur when someone is thinking about plans for after your speech, or thinking about topics and things completely unrelated to the speech at hand. These are all examples of internal distractions.

In order to best focus in on a speaker’s message, try to eliminate as many possible distractions as possible. Turn off all mobile devices, relocate to a quiet space, and close unnecessary windows on the computer.

Active Listening

Active listening is a communication technique that requires the listener to feed back what they hear to the speaker. Most often, listeners will do this by re-stating or paraphrasing what they have heard in their own words. This activity confirms what the listener heard and, moreover, confirms that both parties understand each other. It is important to note, however, that by paraphrasing the speaker’s message, the listener is not necessarily agreeing with the speaker. Paraphrasing also helps the listener better retain that information for future access.

If someone is actively listening, then he or she is typically not distracted. Speakers can also cultivate the habit of avoiding distractions (for example, by addressing questions after the presentation, not during).

In addition to internalizing what a speaker says, active listening also involves observing and assessing the speaker’s behavior and body language, and relaying that information back to the speaker as well. Having the ability to interpret a speaker’s body language lets the listener develop a more accurate understanding of the speaker’s message. When the listener does not respond to the speaker’s nonverbal language, he or she engages in a content-only response that ignores the emotions that guide the message; this can limit understanding.

The ability to listen actively demonstrates sincerity on the part of the listener and helps to make sure that no information is being assumed or taken for granted. Active listening is most often used to improve personal relationships, reduce misunderstanding and conflicts, strengthen cooperation, and foster understanding.

5.4.2: Be an Open-Minded Listener: Suspend Judgment and Exercise Empathy

Open-minded listening requires empathy and a suspension of judgment on the part of the listener.

Learning Objective

Explain how to listen with an open mind

Key Points

- Listening with an open mind means being receptive to being influenced by what one hears.

- Suspend judgment by becoming aware of pre-conceived notions; listening to the entire speech before jumping to conclusions; and listening to what the speaker has to say for understanding, not just to determine whether the speaker is right or wrong.

- Listening with empathy lets the listener better understand where the speaker is coming from, emotionally and conceptually.

- To be an effective open-minded listener, learn to leave ego at the door, and instead strive to find common ground with your speaker.

Key Terms

- empathy

-

The capacity to understand another person’s point of view or the result of such understanding.

- Judgment

-

The evaluation of evidence in the making of a decision.

Example

- Though Kate was annoyed that Jackson had left the car windows open in the rain, after listening to his explanation with an open mind, she understood that he’d been under a lot of stress at work lately and that he was sorry for the mishap.

Suspending Judgment

Be an Open-Minded Listener

Open mindedness is essential to effective listening.

Someone who listens with an open mind is willing to be influenced by what he or she hears. It does not mean that the listener should not have strong views of his or her own, but it does require the listener to be willing to consider the merit of what other people say. This can be difficult when listening to something one does not want to hear or something about which one has pre-conceived notions.

All people have their own opinions on just about everything, so when people listen, they are tempted to immediately judge what someone else is saying from their own perspectives. However, this kind of pre-judging can lead to misunderstanding. People who listen with an open mind avoid anticipating what they think their conversational partners are going to say. They do not jump to conclusions, but rather hear the speaker out entirely and make an effort to understand his or her lines of argument.

Judgmental listening also occurs when the listener is only listening to the speaker in order to determine whether he or she is right or wrong, rather than listening to understand the speaker’s ideas and where they come from. This kind of judgmental listening prevents the listener from fully engaging with the speaker on his or her own terms, and therefore limits the scope of the conversation.

Carrying pre-conceived notions about the speaker or the content of a speech into a conversation further limits effective listening. Listeners may have overwhelmingly positive or negative associations with particular people or ideas, and those associations can affect how listeners interpret. To listen effectively, one must work to temporarily suspend those associations in order to understand the speaker on his or her own terms.

Exercising Empathy

Exercising empathy while listening to a speaker is related to suspending judgment in that it requires the listener to work to understand what the speaker says from his or her point of view. This does not mean that the listener must automatically agree with the speaker; rather, the listener should simply put him- or herself in the speaker’s shoes and try to see the presented arguments from that perspective. One of the primary jobs of an effective listener is to get in touch with the speaker’s perspective and not to color it with his or her own.

Empathetic listening helps promote effective listening because it allows the listener to take into account where the speaker is coming from, both emotionally and in terms of the content of his or her speech. This lets the listener assess what the speaker says and how it is presented more accurately, which ultimately leads to better understanding.

Tips for Being an Open-Minded Listener

- Leave ego at the door. Come to the presentation with a mind like a blank slate.

- When disagreeing with the speaker, write down the objections rather than tuning out the presenter.

- Be open to new ideas or new ways of thinking.

- Look for opportunities to share common ground with the speaker, such as beliefs, ideologies, or experiences.

5.5: Helping Your Audience Listen More

5.5.1: Read Feedback Cues

Feedback is the verbal and non-verbal responses from an audience which help the speaker modify and regulate what s/he is saying.

Learning Objective

Apply your observations of feedback from your audience to modify your speech

Key Points

- Verbal feedback–during the speech you may solicit feedback from the audience by asking a simple question to get feedback from the audience.

- Non-verbal feedback–When you are in front of the audience, non-verbal behavior can be an important cue to what the audience understands, the level of attentiveness, excitement or agreement, or confusion or disagreement.

- Audience Response System– capture feedback from a large or remote audience by using an audience response system to ask questions and then display the answers. Audience members can respond using a wireless keypad such as a clicker, SMS, or text using a smartphone.

- You can use the responses as personal feedback to modify your message or you can share them with the audience by displaying the tabulated responses on a web page or projected as part of a PowerPoint presentation.

Key Term

- feedback

-

The receivers’ verbal and nonverbal responses to a message, such as a nod for understanding (nonverbal), a raised eyebrow for being confused (nonverbal), or asking a question to clarify the message (verbal).

Read Feedback Cues

Feedback is the response from the listeners

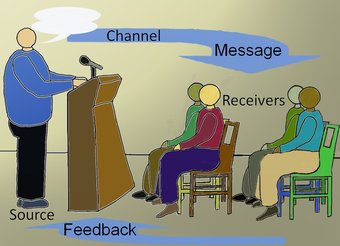

Feedback is the response that listeners provide to the sender of the message. Feedback is a cue to the speaker to modify or regulate what is being said. Feedback can take the form of verbal or non-verbal responses to an in-person speech, or verbal responses which are electronically captured for large or remote audiences .

Receiving Feedback

It is important for the speaker to receive feedback from the audience.

In-Person Verbal and Non-Verbal Feedback

Verbal Feedback

During the speech you may solicit feedback from the audience by asking a simple question. Audience members may respond verbally or they may nod or raise their hands. Additionally, audience members may ask a question or let you know if they do not understand. You may also receive direct positive or negative feedback from members of the audience who agree or disagree with what you are saying. Listen for the verbal feedback and acknowledge it.

Non-Verbal Feedback

When you are in front of the audience, non-verbal behavior can be an important cue to what the audience understands, the level of attentiveness, excitement or agreement, or confusion or disagreement. The non-verbal feedback may be intentional vocalizations, such as groans or encouragement (such as clapping). However, much of the non-verbal feedback may be unconscious physical body language, which can provide feedback for you. Here are some examples of body language that you may notice displayed consciously or subconsciously by members of the audience:

- Boredom: boredom is indicated by the head tilting to one side, or by the eyes looking straight at the speaker but becoming slightly unfocused.

- Disbelief: this is often indicated by averted gaze or by touching the ear or scratching the chin. When a person is not being convinced by what someone is saying, the attention invariably wanders and the eyes will stare away for an extended period.

- Attentive eye contact: Are audience members looking directly at you attentively or are they looking around? Consistent eye contact can indicate that a person is interested and thinking positively about the speaker’s subject. However, if a person is fiddling with something, even while directly looking at you, it could indicate that the attention is elsewhere.

- Body position and posture: Audience members will generally face the speaker while listening intently; if the audience members are not interested they may shift the body position to the side rather than toward the speaker.

If you maintain eye contact with your audience while speaking, you can observe the cues and adapt your message. What is your audience telling you? All the non-verbal feedback needs to be processed with knowledge of the cultural context of the speaker and the audience. Remember that people from different cultures do interpret body language in different ways. For example, eye contact can be misleading because cultural norms about it vary widely. Direct eye contact may show attentiveness to the North American speaker but be considered a confrontation in another culture. And, certain hand gestures that are perfectly acceptable to one group may be disrespectful to another audience.

Feedback Electronically Captured from Large or Remote Audiences

You can also capture the responses from the audience by using an audience response system that you can view privately as you speak or display to the audience. You can solicit feedback directly by asking multiple choice, true-false, or numerical questions from audience members who respond using a wireless keypad such as a clicker, SMS, or text using a smartphone. The feedback from the audience is then sent back to your computer and processed by the audience response software. For a large or remote audience, you can plan to include different questions or polls to capture feedback from your audience and adapt your message accordingly. It is necessary to structure the questions to get the feedback you want. For example, if a large percentage of your audience answers a question with a certain wrong answer, you will know that you need to explain that concept differently. Conversely, if a large percentage of the audience agrees with an opinion, you can use that feedback to adapt your message.

Timing of Feedback

Assessment, or the tactics speakers and audience members use to facilitate learning, is often divided into initial, formative, and summative categories.

- Initial assessment, also referred to as pre-assessment or diagnostic assessment, is conducted prior to instruction or intervention to establish a baseline from which an individual’s growth can be measured.

- Formative assessment is generally carried out throughout a course or project. Formative assessment, also referred to as “educative assessment,” is used to aid learning. For example, in an educational setting, formative assessment might be a teacher (or peer) or the learner, providing feedback on a student’s work and would not necessarily be used for grading purposes. Formative assessments can take the form of diagnostic, standardized tests.

- Summative assessment is generally carried out at the end of a course, project or speech. In an educational setting, summative assessments are typically used to assign students a course grade. Whereas following a speech or presentation, summative assessment can be provided in the form of positive feedback, applause or a standing ovation.

5.5.2: Hold the Audience’s Attention

To hold the audience’s attention, consider their readiness to perceive, the selection of stimuli, and how to maintain current awareness.

Learning Objective

Employ strategies for maintaining audience focus

Key Points

- If the speaker can establish readiness by getting the audience’s attention during the first 25-30 seconds of the speech, he or she can then direct and focus that attention to the important parts of the message.

- The speaker can direct the attention of the audience to what is important by using changes in rate and volume, body movement, and gesture to emphasize what is important.

- It is important to read the non-verbal clues of the audience to understand if they have shifted their attention somewhere else.

- If the audience’s attention is shifting from the speech, challenge the audience with an inquiry to stimulating thinking.

- There are many strategies to employ to hold the attention of the audience, but the most important is the ability to establish and maintain a genuine connection with the people in the audience.

Key Terms

- awareness

-

The state or ability to perceive, to feel, or to be conscious of events, objects, or sensory patterns. In this level of consciousness, sense data can be confirmed by an observer without necessarily implying understanding.

- Perception

-

Conscious understanding of something; acuity.

To hold the attention of the audience, a public speaker should consider three important aspects of the process of perception: readiness to perceive, selection of certain stimuli for focus of attention, and state of current awareness.

Readiness to Perceive

The speaker is responsible for setting the stage. The speaker does this with the opening introduction in the the first 25 to 30 sections. If the speaker can secure the attention of the audience at the very beginning of the speech, he or she can then direct and focus that attention to the important parts of the message, as follows:

- Make sure that the room is free of noise and other distractions, to ensure that the audience is focused on the speech, rather than what is happening in the room.

- Speakers are often introduced by a host. This brief introduction is important because it helps to establish the speaker’s credentials and prepares the audience members so their attention is properly directed.

- Remember that the first important function of the introduction is to “capture the attention of the audience” and them immediately direct attention to the speech’s main message.

Selection of Certain Stimuli for Focus

While delivering the speech, the speaker wants the audience to concentrate on his or her message, and directs their attention to what is important through the use of voice, body, and gesture. This is done by emphasizing the important points by changing the rate, volume, or pitch of the voice. Using vocal variety purposely helps the audience know what is important and directs their attention to those elements. In addition, the speaker’s body and gestures can direct attention to important aspects of the message (for example, by pointing to, walking to, or touching a visual aid or diagram). Additional examples include the following:

- To understand where he or she wants the audience to direct their attention, the speaker can consider a quick internal summary of an idea.

- Use signposts, such as “Now get this…” or “Here is the important point, which I want you to remember. “

- When using a visual aid, use additional audio cues or color changes to highlight specific areas.

State of Current Awareness

Speakers must read the non-verbal clues of the audience to understand if they have shifted their focus somewhere else. If the audience members are glancing at their watches, texting, or glancing at other people in the audience, the speaker should recognize the current state and redirect the attention back to the speech’s message. To change the current state of the audience’s awareness and re-gain their attention, try the following:

- Challenge the audience with an inquiry to stimulating thinking. Ask for a show of hands to vote or to give answers, use clickers or an audience response system to get a response and then share the result, or ask a relevant question to stimulate thought.

- Engage in narrative as a change of pace from message delivery. Create a narrative that is relevant to the topic and is dramatic for the audience, and use a surprise ending to direct the audience attention to the message.

- Provide concrete examples of a concept or main point that is directly relevant and engaging for the audience. Make a comparison to something that has recently happened in the community or nationally.

- Stimulate the audience’s imagination or take them on a fantasy journey that stimulates the different senses. The more the senses are stimulated, the more the current focus is on the speech’s message.

There are many strategies that the speaker can employee to hold the attention of the audience, but the most important is the ability to establish and maintain a genuine connection with the people in your audience. Speakers don’t need to use a choke-hold to keep the audience’s attention.

Choke-hold

Speakers don’t need to use a choke -hold to keep the audience’s attention.

5.5.3: Maximize Understanding

To maximize understanding, use general rhetorical strategies and other approaches that build upon the audience’s prior experiences.

Learning Objective

Give examples of ways to help your audience understand your ideas

Key Points

- We depend on the use of words applied in various rhetorical strategies to exchange understandings.

- You can apply prior knowledge of the audience to choose the right vocabulary, to make comparisons with things familiar to them, to show the origin of things, to group things into categories meaningful to them, and to number the steps or events in the order that they occur.

- To increase understanding during a speech, you can take the perspective of the audience to restate ideas, to ask the audience questions, and to paraphrase what you have just said using different examples and choice of words.

Key Terms

- comparison

-

An evaluation of the similarities and differences of one or more things relative to each other.

- understanding

-

The mental (sometimes emotional) process of comprehension, or the assimilation of knowledge, which is subjective by its nature.

- classification

-

The act of forming into a class or classes; a distribution into groups, as classes, orders, families, etc., according to some common relations or attributes.

The Elements of Understanding

Understanding involves comprehending or knowing about an object, idea, concept, or process. In essence, you want the audience to comprehend and share the same understanding. It would be a very simple process if you could just exchange memory modules for your audience to upload, but we are not there yet. Today, you will use words to explain your thoughts. Here we are concerned with how you might use different rhetorical strategies to maximize what the audience understands.

Applying Prior Knowledge about the Audience

Apply what you already know about the demographics, background, and life experiences of the audience. Ask yourself, “What does my audience already understand or know? ” You can apply the knowledge to maximize understanding.

- Language choice and vocabulary: You’ll want to begin your explanation at the right level; ask yourself, “What vocabulary will my audience understand and what do I need to explain before I can explain other concepts? “

- Compare and contrast based upon shared knowledge: When you are showing how two things are alike, create connections with what the audience already knows. In order to maximize understanding, you’ll want to compare those things that are already familiar against the new and unfamiliar things. Then, you can demonstrate how they are the same or different.

- Visualize transformation by cause and origin: Where did something come from and how did it get to its present state or condition? Help the audience picture the change from one state or condition to another.

- Classification and grouping alike things to form a concept: First, you’ll want to cite examples that are familiar to the audience and put them into the same classification. Then you can put other less familiar objects or ideas into the same class or grouping while using the same label. You can even help the audience generalize to create a classification. For example, let’s say you see a fir, a willow, and a linden. By comparing these objects, you notice that they are different from one another in respect to the trunk, branches, leaves, and the like; a further comparison, however, reveals what they have in common: the trunk, branches, and leaves themselves, which form the abstraction from their size, shape, and so forth. Thus, you gain a concept of a tree .

- Sequence and origin: Here you help the audience understand the process or sequence of events in time. You can clearly list and number the steps or events in the order in which they occur. In addition to using sequencing words, you can also use simple mnemonics, like the knuckle mnemonic, which helps the listeners sequence things such as how many days are in each month .

Applying General Strategies

- Perspective-taking: Practice perspective-taking so you can frame and reframe your examples in a way that the audience members will understand. You’ll want to see how the members of the audience organize the world cognitively in order to reframe your concepts so that the audience understands them. If your initial explanation is not effective with a particular audience, you may reframe and refocus on different aspects of what you are explaining.

- Repetition: Build upon prior understanding of concepts by repeating and using internal summaries. This ensures the audience does not miss an important idea that is critical to understanding the whole message.

- Questioning: Question your audience to see if they understand what you are saying, and adjust your explanation in order to clarify misunderstandings.

- Paraphrase: Paraphrase what you said for the audience and restate the ideas using different examples. Different audience members may not understand one idea but may understand another that relates more directly to their prior knowledge.

Simply put, you’ll want to learn how the audience conceptualizes the world and then use that knowledge to maximize understanding. Use your skills of restating, questioning, perspective-taking, and paraphrasing to help clarify and reinforce understanding as you speak.

5.5.4: Build Credibility

Aristotle established three methods of proof to build credibility: initial, derived, and terminal.

Learning Objective

Give examples of ways to build credibility before, during, and after your speech

Key Points

- Credibility is not a characteristic of the source or speaker but an attitude in the mind of the listener(s). You may have high credibility with one group of listeners and low credibility with another.

- Building initial credibility—your initial credibility is your personal brand. The audience may know you prior to the speech. If not, have someone introduce you or provide relevant background as a self-introduction.

- Building derived credibility—When you speak confidently and assertively you inspire others with your energy and words. To build credibility you want to look at everything you do in the speech such as appearance, delivery, word choice, and in general how you handle yourself.

- Building derived credibility—You establish common ground with the audience by sharing aspects of your background that are similar to the audience, by using supporting examples or experiences that you and the audience have in common, and by creating a bond with the audience.

- Terminal credibility—You can build credibility for your next speech by establishing a rapport with the audience so they walk away with a more positive view of you than when you started.

Key Terms

- ethos

-

A rhetorical appeal to an audience based on the speaker/writer’s credibility.

- Aristotle

-

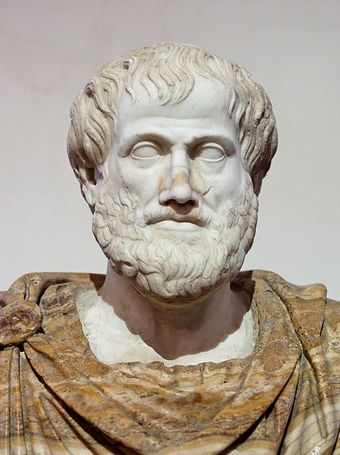

An ancient Greek philosopher (382–322 BC), student of Plato, and teacher of Alexander the Great.

- credibility

-

The objective and subjective components of the believability of a source or message.

Build Credibility

Building Credibility through Character and Competence

Aristotle, the classical Greek philosopher and rhetorician, established three methods of proof—logos, ethos, and pathos.

Logos is the logical development of the message, pathos is the emotional appeals employed by the speaker, and ethos is the moral character of the speaker as perceived by the audience. Our focus on credibility relates to ethos, the ethical character and competence of the speaker. To build credibility you want to focus on three stages: (1) Initial credibility is what the audience knows and their opinion prior to the speech, (2) Derived (during) credibility is how the audience perceives you while delivering the speech, and (3) Terminal is the lasting impression that the audience has of you as they leave the speech.

Bust of Aristotle

Marble, Roman copy after a Greek bronze original by Lysippos from 330 BC; the alabaster mantle is a modern addition.

Building Initial Credibility

Here we look at who you are as a person; what the audience knows about your expertise and whether the audience thinks you are trustworthy. You may think about initial credibility as your personal branding: who you are and what you audience knows about you. Your reputation may precede you but if it does not, you may rely on an introduction prior to the speech. Often a host or moderator will introduce you and provide relevant information about your background. If there is no moderator to provide an introduction, you may include a brief self-introduction about yourself as it relates to the topic and your motivation for speaking. Building initial credibility helps prepare the audience for what is to come during the speech.

Building Derived Credibility

This is where you want to look at how the audience perceives you during the speech. You derive credibility during the speech by what you do. Your credibility with the audience derives from how the audience responds to what you wear, the words you use, your delivery, and in general the way you handle yourself during the speech. If you use strong supporting evidence and explain it to the audience, you will enhance your perceived competence. If you communicate sincerely and honestly with the audience, you will enhance the perception of your character. If you speak confidently and assertively, while demonstrating a genuine concern for the audience, you will increase your credibility with the audience.

Another important aspect of credibility during the speech is your ability to establish common ground with the audience. You can establish common ground by sharing aspects of your background that are similar to the audience. You may also establish common ground through the selection of examples that you and the audience share in experience.

Establish common ground by creating a bond with the audience that will help the audience identify with you. For example, “I am like you, I share your concerns. ” The audience is more likely to trust a speaker that they feel they know and who knows them.

Terminal Credibility

As a speaker, you want to build a rapport with the audience so they leave with as good or a better impression of you than when you began your speech. Rapport occurs when two or more people feel that they are in sync or on the same wavelength because they feel similarly or relate well to each other. In a sense, what you send out—the audience sends back. For example, they may realize they share similar values, beliefs, knowledge, or behaviors around sports or politics as you deliver your speech and regard you more favorably than before you started your speech. You can build credibility for your next speech by establishing rapport with the audience. If you are honest and ethical with your audience and share your values and beliefs, you establish a rapport that will carry over beyond the speech.

Ask yourself, “Will my audience trust me ?” We are not really talking about a characteristic of the source or speaker, but an attitude in the mind of the listeners. You may have high credibility with one listener or group of listeners and low credibility with another.

5.5.5: Make Messages Easy to Remember

Encoding (or registration), storage, and recollection comprise the three main stages in the formation and retrieval of memory.

Learning Objective

Demonstrate methods for helping your audience remember your message

Key Points

- Creating mental images of objects, people, and things is one of the oldest memory tools presented in classic rhetoric.

- Creating an organizational scheme and positioning ideas, objects, or processes into a specific order makes it easier for audiences to remember and reinforce through the scheme.

- Breaking up long lists or series into smaller and manageable groupings of four to five items helps audiences recall the items.

- Associating your new idea with ideas that are similar and/or familiar to the audience ensures that the associations are meaningful and memorable.

- Repeating important ideas helps the audience remember and include internal summaries.

- Creating a short poem, special word, or link system such as a story helps audiences visualize a connection between previously unconnected objects, ideas, or events.

Key Terms

- singularity

-

A proposed point in the technological future at which artificial intelligences become capable of augmenting and improving themselves, leading to an explosive growth in intelligence.

- mnemonic

-

Anything (especially something in verbal form) used to help remember something.

- memory

-

The ability of an organism to record information about things or events with the facility of recalling them later at will.

Make Messages Easy to Remember

Memory refers to the process by which information is encoded, stored, and retrieved. From an information processing perspective, there are three main stages in the formation and retrieval of memory:

- Encoding or registration : allows information that is from the outside world to reach our senses in the form of chemical or physical stimuli

- Storage: creates a permanent record of the encoded information

- Retrieval, recall or recollection: calls back the stored information in response to some cue for use in a process or activity

If you could simply transfer your memory modules to the brains of your audience, speaking would be obsolete. Cyborg memory transfer is not feasible yet, and we have not reached singularity with the audience, but we can develop our ideas and deliver them in such a way as to facilitate the transfer of information.

Remembering Information

Like electronic memory cards, humans employ storage methods to permanently record thoughts and memories.

Principles for supporting memory