What is it like to be a young man entering adulthood? According to sociologist Michael Kimmel, they are “totally confused,” “cannot commit to their relationships, work, or lives,” and are

“obsessed with never wanting to grow up.”[1] If that sounds like a bunch of malarkey to you, hold on a minute. Kimmel (2008) interviewed 400 young men, ages 16 to 26, over the course of four years across the United States to learn how young men made the transition from adolescence into adulthood. Since the results of Kimmel’s research were published in 2008, his book Guyland made quite a splash. Whatever your take on Kimmel’s research, one thing remains true—we surely would not know nearly as much as we now do about the lives of many young American men were it not for qualitative interview research.

Chapter Outline

- 9.1 Qualitative research: What is it and when should it be used?

- 9.2 Qualitative interviews

- 9.3 Issues to consider for all interview types

- 9.4 Types of Qualitative Research Designs

- 9.5 Spotlight on UTA School of Social Work

- 9.6 Analyzing qualitative data

Content Advisory

This chapter discusses or mentions the following topics: childfree adults, sexual harassment, juvenile delinquency, drunk driving, racist hate groups, ageism, sexism, police interviews, and mental health policy for children and adolescents.

9.1 Qualitative research: What is it and when should it be used?

Learning Objectives

- Define qualitative research

- Explain the differences between qualitative and quantitative research

- Identify the benefits and challenges of qualitative research

Qualitative versus quantitative research methods refers to data-oriented considerations about the type of data to collected and how they are analyzed. Qualitative research relies mostly on non-numeric data, such as interviews and observations to understand their meaning, in contrast to quantitative research which employs numeric data such as scores and metrics. Hence, qualitative research is not amenable to statistical procedures, but is coded using techniques like content analysis. Sometimes, coded qualitative data are tabulated quantitatively as frequencies of codes, but this data is not statistically analyzed. Qualitative research has its roots in anthropology, sociology, psychology, linguistics, and semiotics, and has been available since the early 19th century, long before quantitative statistical techniques were employed.

Distinctions from Quantitative Research

In qualitative research, the role of the researcher receives critical attention. In some methods such as ethnography, action research, and participant observation, the researcher is considered part of the social phenomenon, and her specific role and involvement in the research process must be made clear during data analysis. In other methods, such as case research, the researcher must take a “neutral” or unbiased stance during the data collection and analysis processes, and ensure that her personal biases or preconceptions does not taint the nature of subjective inferences derived from qualitative research.

Analysis in qualitative research is holistic and contextual, rather than being reductionist and isolationist. Qualitative interpretations tend to focus on language, signs, and meanings from the perspective of the participants involved in the social phenomenon, in contrast to statistical techniques that are employed heavily in positivist research. Rigor in qualitative research is viewed in terms of systematic and transparent approaches for data collection and analysis rather than statistical benchmarks for construct validity or significance testing.

Lastly, data collection and analysis can proceed simultaneously and iteratively in qualitative research. For instance, the researcher may conduct an interview and code it before proceeding to the next interview. Simultaneous analysis helps the researcher correct potential flaws in the interview protocol or adjust it to capture the phenomenon of interest better. The researcher may even change her original research question if she realizes that her original research questions are unlikely to generate new or useful insights. This is a valuable but often understated benefit of qualitative research, and is not available in quantitative research, where the research project cannot be modified or changed once the data collection has started without redoing the entire project from the start.

Benefits and Challenges of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research has several unique advantages. First, it is well-suited for exploring hidden reasons behind complex, interrelated, or multifaceted social processes, such as inter-firm relationships or inter-office politics, where quantitative evidence may be biased, inaccurate, or otherwise difficult to obtain. Second, it is often helpful for theory construction in areas with no or insufficient pre-existing theory. Third, qualitative research is also appropriate for studying context-specific, unique, or idiosyncratic events or processes. Fourth, it can help uncover interesting and relevant research questions and issues for follow-up research.

At the same time, qualitative research also has its own set of challenges. First, this type of research tends to be more time and resource intensive than quantitative research in data collection and analytic efforts. Too little data can lead to false or premature assumptions, while too much data may not be effectively processed by the researcher. Second, qualitative research requires well-trained researchers who are capable of seeing and interpreting complex social phenomenon from the perspectives of the embedded participants and reconciling the diverse perspectives of these participants, without injecting their personal biases or preconceptions into their inferences. Third, all participants or data sources may not be equally credible, unbiased, or knowledgeable about the phenomenon of interest, or may have undisclosed political agendas, which may lead to misleading or false impressions. Inadequate trust between participants and researcher may hinder full and honest self-representation by participants, and such trust building takes time. It is the job of the qualitative researcher to “see through the smoke” (hidden or biased agendas) and understand the true nature of the problem. Finally, given the heavily contextualized nature of inferences drawn from qualitative research, such inferences do not lend themselves well to replicability or generalizability.

Key Takeaways

- Qualitative research examines words and other non-numeric media

- Analysis in qualitative research is holistic and contextual

- Qualitative research offers unique benefits, while facing challenges to generalizability and replicability

Glossary

- Qualitative methods – examine words or other media to understand their meaning

9.2 Qualitative interviews

Learning Objectives

- Define interviews from the social scientific perspective

- Identify when it is appropriate to employ interviews as a data-collection strategy

- Identify the primary aim of in-depth interviews

- Describe what makes qualitative interview techniques unique

- Define the term interview guide and describe how to construct an interview guide

- Outline the guidelines for constructing good qualitative interview questions

- Describe how writing field notes and journaling function in qualitative research

- Identify the strengths and weaknesses of interviews

Knowing how to create and conduct a good interview is an essential skill. Interviews are used by market researchers to learn how to sell their products, and journalists use interviews to get information from a whole host of people from VIPs to random people on the street. Police use interviews to investigate crimes.

In social science, interviews are a method of data collection that involves two or more people exchanging information through a series of questions and answers. The questions are designed by the researcher to elicit information from interview participants on a specific topic or set of topics. These topics are informed by the research questions. Typically, interviews involve an in-person meeting between two people—an interviewer and an interviewee — but interviews need not be limited to two people, nor must they occur in-person.

The question of when to conduct an interview might be on your mind. Interviews are an excellent way to gather detailed information. They also have an advantage over surveys—they can change as you learn more information. In a survey, you cannot change what questions you ask if a participant’s response sparks some follow-up question in your mind. All participants must get the same questions. The questions you decided to put on your survey during the design stage determine what data you get. In an interview, however, you can follow up on new and unexpected topics that emerge during the conversation. Trusting in emergence and learning from participants are hallmarks of qualitative research. In this way, interviews are a useful method to use when you want to know the story behind the responses you might receive in a written survey.

Interviews are also useful when the topic you are studying is rather complex, requires lengthy explanation, or needs a dialogue between two people to thoroughly investigate. Also, if people will describe the process by which a phenomenon occurs, like how a person makes a decision, then interviews may be the best method for you. For example, you could use interviews to gather data about how people reach the decision not to have children and how others in their lives have responded to that decision. To understand these “how’s” you would need to have some back-and-forth dialogue with respondents. When they begin to tell you their story, inevitably new questions that hadn’t occurred to you from prior interviews would come up because each person’s story is unique. Also, because the process of choosing not to have children is complex for many people, describing that process by responding to closed-ended questions on a survey wouldn’t work particularly well.

Interview research is especially useful when:

- You wish to gather very detailed information

- You anticipate wanting to ask respondents follow-up questions based on their responses

- You plan to ask questions that require lengthy explanation

- You are studying a complex or potentially confusing topic to respondents

- You are studying processes, such as how people make decisions

Qualitative interviews are sometimes called intensive or in-depth interviews. These interviews are semi-structured; the researcher has a particular topic about which she would like to hear from the respondent, but questions are open-ended and may not be asked in exactly the same way or in exactly the same order to each and every respondent. For in-depth interviews, the primary aim is to hear from respondents about what they think is important about the topic at hand and to hear it in their own words. In this section, we’ll take a look at how to conduct qualitative interviews, analyze interview data, and identify some of the strengths and weaknesses of this method.

Constructing an interview guide

Qualitative interviews might feel more like a conversation than an interview to respondents, but the researcher is in fact usually guiding the conversation with the goal in mind of gathering specific information from a respondent. Qualitative interviews use open-ended questions, which are questions that a researcher poses but does not provide answer options for. Open-ended questions are more demanding of participants than closed-ended questions because they require participants to come up with their own words, phrases, or sentences to respond.

In a qualitative interview, the researcher usually develops an interview guide in advance to refer to during the interview (or memorizes in advance of the interview). An interview guide is a list of questions or topics that the interviewer hopes to cover during the course of an interview. It is called a guide because it is simply that—it is used to guide the interviewer, but it is not set in stone. Think of an interview guide like an agenda for the day or a to-do list—both probably contain all the items you hope to check off or accomplish, though it probably won’t be the end of the world if you don’t accomplish everything on the list or if you don’t accomplish it in the exact order that you have it written down. Perhaps new events will come up that cause you to rearrange your schedule just a bit, or perhaps you simply won’t get to everything on the list.

Interview guides should outline issues that a researcher feels are likely to be important. Because participants are asked to provide answers in their own words and to raise points they believe are important, each interview is likely to flow a little differently. While the opening question in an in-depth interview may be the same across all interviews, from that point on, what the participant says will shape how the interview proceeds. Sometimes participants answer a question on the interview guide before it is asked. When the interviewer comes to that question later on in the interview, it’s a good idea to acknowledge that they already addressed part of this question and ask them if they have anything to add to their response. All of this uncertainty can make in-depth interviewing exciting and rather challenging. It takes a skilled interviewer to be able to ask questions; listen to respondents; and pick up on cues about when to follow up, when to move on, and when to simply let the participant speak without guidance or interruption.

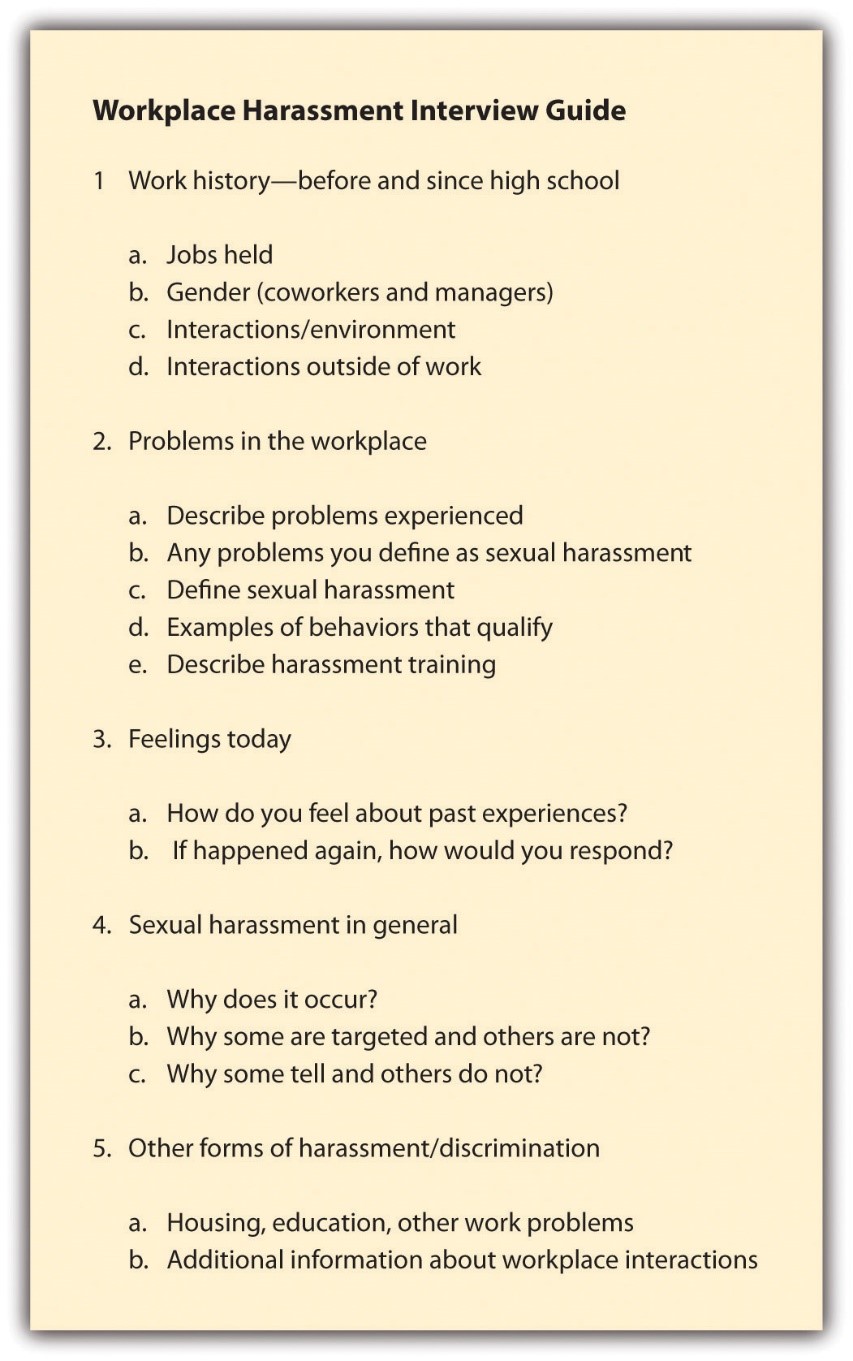

As we’ve discussed, interview guides can list topics or questions. The specific format of an interview guide might depend on your style, experience, and comfort level as an interviewer or with your topic. Figure 9.1 provides an example of an interview guide for a study of how young people experience workplace sexual harassment. The guide is topic-based, rather than a list of specific questions. The ordering of the topics is important, though how each comes up during the interview may vary.

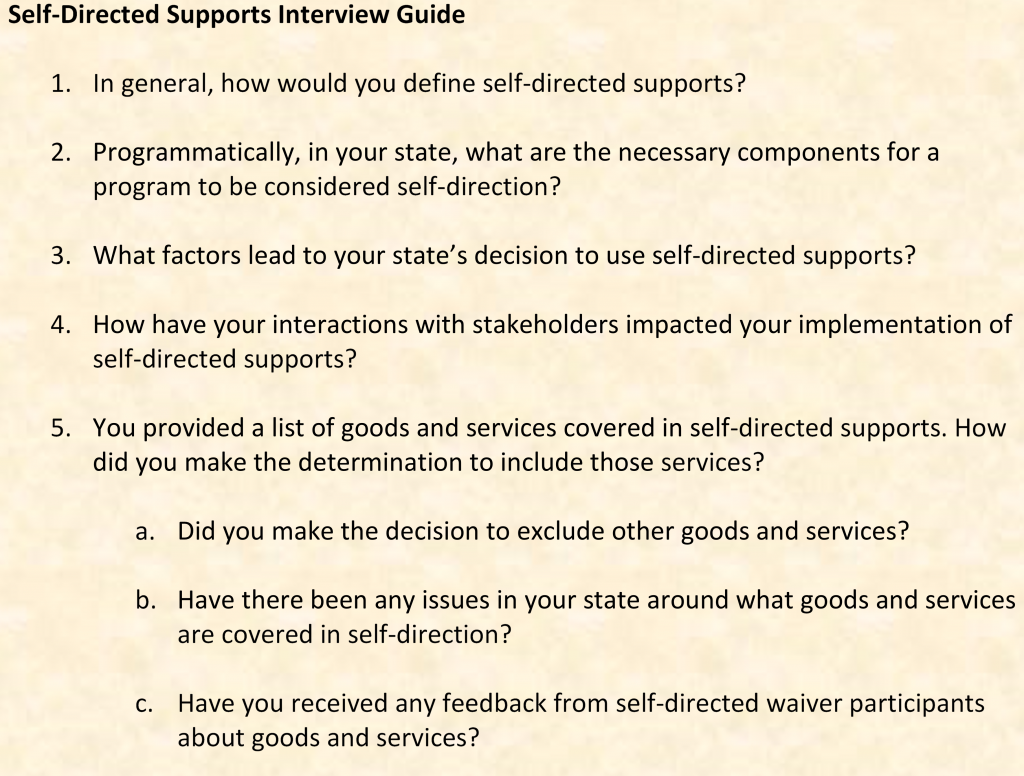

For interview guides that use questions, there can also be specific words or phrases for follow-up in case the participant does not mention those topics in their responses. These probes, as well as the questions are written out in the interview guide, but may not always be used. Figure 9.2 provides an example of an interview guide that uses questions rather than topics.

As you might have guessed, interview guides do not appear out of thin air. They are the result of thoughtful and careful work on the part of a researcher. As you can see in both of the preceding guides, the topics and questions have been organized thematically and in the order in which they are likely to proceed (though keep in mind that the flow of a qualitative interview is in part determined by what a respondent has to say). Sometimes qualitative interviewers may create two versions of the interview guide: one version contains a very brief outline of the interview, perhaps with just topic headings, and another version contains detailed questions underneath each topic heading. In this case, the researcher might use the very detailed guide to prepare and practice in advance of actually conducting interviews and then just bring the brief outline to the interview. Bringing an outline, as opposed to a very long list of detailed questions, to an interview encourages the researcher to actually listen to what a participant is saying. An overly detailed interview guide can be difficult to navigate during an interview and could give respondents the mis-impression the interviewer is more interested in the questions than in the participant’s answers.

Constructing an interview guide often begins with brainstorming. There are no rules at the brainstorming stage—simply list all the topics and questions that come to mind when you think about your research question. Once you’ve got a pretty good list, you can begin to pare it down by cutting questions and topics that seem redundant and group similar questions and topics together. If you haven’t done so yet, you may also want to come up with question and topic headings for your grouped categories. You should also consult the scholarly literature to find out what kinds of questions other interviewers have asked in studies of similar topics and what theory indicates might be important. As with quantitative survey research, it is best not to place very sensitive or potentially controversial questions at the very beginning of your qualitative interview guide. You need to give participants the opportunity to warm up to the interview and to feel comfortable talking with you. Finally, get some feedback on your interview guide. Ask your friends, other researchers, and your professors for some guidance and suggestions once you’ve come up with what you think is a strong guide. Chances are they’ll catch a few things you hadn’t noticed. Once you begin your interviews, your participants may also suggest revisions or improvements.

In terms of the specific questions you include in your guide, there are a few guidelines worth noting. First, avoid questions that can be answered with a simple yes or no. Try to rephrase your questions in a way that invites longer responses from your interviewees. If you choose to include yes or no questions, be sure to include follow-up questions. Remember, one of the benefits of qualitative interviews is that you can ask participants for more information—be sure to do so. While it is a good idea to ask follow-up questions, try to avoid asking “why” as your follow-up question, as this particular question can come off as confrontational, even if that is not your intent. Often people won’t know how to respond to “why,” perhaps because they don’t even know why themselves. Instead of asking “why,” you say something like, “Could you tell me a little more about that?” This allows participants to explain themselves further without feeling that they’re being doubted or questioned in a hostile way.

Also, try to avoid phrasing your questions in a leading way. For example, rather than asking, “Don’t you think most people who don’t want to have children are selfish?” you could ask, “What comes to mind for you when you hear someone doesn’t want to have children?” Finally, remember to keep most, if not all, of your questions open-ended. The key to a successful qualitative interview is giving participants the opportunity to share information in their own words and in their own way. Documenting the decisions made along the way regarding which questions are used, thrown out, or revised can help a researcher remember the thought process behind the interview guide when she is analyzing the data. Additionally, it promotes the rigor of the qualitative project as a whole, ensuring the researcher is proceeding in a reflective and deliberate manner that can be checked by others reviewing her study.

Recording qualitative data

Even after the interview guide is constructed, the interviewer is not yet ready to begin conducting interviews. The researcher has to decide how to collect and maintain the information that is provided by participants. Researchers keep field notes or written recordings produced by the researcher during the data collection process. Field notes can be taken before, during, or after interviews. Field notes help researchers document what they observe, and in so doing, they form the first step of data analysis. Field notes may contain many things—observations of body language or environment, reflections on whether interview questions are working well, and connections between ideas that participants share.

Unfortunately, even the most diligent researcher cannot write down everything that is seen or heard during an interview. In particular, it is difficult for a researcher to be truly present and observant if she is also writing down everything the participant is saying. For this reason, it is quite common for interviewers to create audio recordings of the interviews they conduct. Recording interviews allows the researcher to focus on the interaction with the interview participant.

Of course, not all participants will feel comfortable being recorded and sometimes even the interviewer may feel that the subject is so sensitive that recording would be inappropriate. If this is the case, it is up to the researcher to balance excellent note-taking with exceptional question-asking and even better listening.

Whether you will be recording your interviews or not (and especially if not), practicing the interview in advance is crucial. Ideally, you’ll find a friend or two willing to participate in a couple of trial runs with you. Even better, find a friend or two who are similar in at least some ways to your sample. They can give you the best feedback on your questions and your interview demeanor.

Another issue interviewers face is documenting the decisions made during the data collection process. Qualitative research is open to new ideas that emerge through the data collection process. For example, a participant might suggest a new concept you hadn’t thought of before or define a concept in a new way. This may lead you to create new questions or ask questions in a different way to future participants. These processes should be documented in a process called journaling or memoing. Journal entries are notes to yourself about reflections or methodological decisions that emerge during the data collection process. Documenting these are important, as you’d be surprised how quickly you can forget what happened. Journaling makes sure that when it comes time to analyze your data, you remember how, when, and why certain changes were made. The discipline of journaling in qualitative research helps to ensure the rigor of the research process—that is its trustworthiness and authenticity which we will discuss later in this chapter.

Strengths and weaknesses of qualitative interviews

As we’ve mentioned in this section, qualitative interviews are an excellent way to gather detailed information. Any topic can be explored in much more depth with interviews than with almost any other method. Not only are participants given the opportunity to elaborate in a way that is not possible with other methods such as survey research, but they also are able share information with researchers in their own words and from their own perspectives. Whereas, quantitative research asks participants to fit their perspectives into the limited response options provided by the researcher. And because qualitative interviews are designed to elicit detailed information, they are especially useful when a researcher’s aim is to study social processes or the “how” of various phenomena. Yet another, and sometimes overlooked, benefit of in-person qualitative interviews is that researchers can make observations beyond those that a respondent is orally reporting. A respondent’s body language, and even their choice of time and location for the interview, might provide a researcher with useful data.

Of course, all these benefits come with some drawbacks. As with quantitative survey research, qualitative interviews rely on respondents’ ability to accurately and honestly recall specific details about their lives, circumstances, thoughts, opinions, or behaviors. Further, as you may have already guessed, qualitative interviewing is time-intensive and can be quite expensive. Creating an interview guide, identifying a sample, and conducting interviews are just the beginning. Writing out what was said in interviews and analyzing the qualitative interview data are time consuming processes. Keep in mind you are also asking for more of participants’ time than if you’d simply mailed them a questionnaire containing closed-ended questions. Conducting qualitative interviews is not only labor-intensive but can also be emotionally taxing. Seeing and hearing the impact that social problems have on respondents is difficult. Researchers embarking on a qualitative interview project should keep in mind their own abilities to receive stories that may be difficult to hear.

Key Takeaways

- Understanding how to design and conduct interview research is a useful skill to have.

- In a social scientific interview, two or more people exchange information through a series of questions and answers.

- Interview research is often used when detailed information is required and when a researcher wishes to examine processes.

- In-depth interviews are semi-structured interviews where the researcher has topics and questions in mind to ask, but questions are open-ended and flow according to how the participant responds to each.

- Interview guides can vary in format but should contain some outline of the topics you hope to cover during the course of an interview.

- Qualitative interviews allow respondents to share information in their own words and are useful for gathering detailed information and understanding social processes.

- Field notes and journaling are ways to document thoughts and decisions about the research process

- Drawbacks of qualitative interviews include reliance on respondents’ accuracy and their intensity in terms of time, expense, and possible emotional strain.

Glossary

- Field notes- written notes produced by the researcher during the data collection process

- In-depth interviews- interviews in which researchers hear from respondents about what they think is important about the topic at hand in the respondent’s own words

- Interviews- a method of data collection that involves two or more people exchanging information through a series of questions and answers

- Interview guide- a list of questions or topics that the interviewer hopes to cover during the course of an interview

- Journaling- making notes of emerging issues and changes during the research process

- Semi-structured interviews- questions are open ended and may not be asked in exactly the same way or in exactly the same order to each and every respondent

9.3 Issues to consider for all interview types

Learning Objectives

- Identify the three main issues that interviewers should consider

- Describe how interviewers can address power imbalances

- Describe and define rapport

- Define the term probe

Qualitative researchers are attentive to the complexities that arise during the interview process. Interviews are intimate processes. Your participants will share with you how they view the world, how they understand themselves, and how they cope with events that happened to them. Conscientious researchers should keep in mind the following topics to ensure the authenticity and trust necessary for successful interviews.

Power differential

First and foremost, interviewers must be aware of and attentive to the power differential between themselves and interview participants. The interviewer sets the agenda and leads the conversation. Qualitative interviewers aim to allow participants to have some control over which or to what extent various topics are discussed, but at the end of the day, it is the researcher who is in charge of the interview and how the data are reported to the public. The participant loses the ability to shape the narrative after the interview is over because it is the researcher who tells the story to the world. As the researcher, you are also asking someone to reveal things about themselves they may not typically share with others. Researchers do not reciprocate by revealing much or anything about themselves. All these factors shape the power dynamics of an interview.

A number of excellent pieces have been written dealing with issues of power in research and data collection. Feminist researchers in particular paved the way in helping researchers think about and address issues of power in their work (Oakley, 1981). Suggestions for overcoming the power imbalance between researcher and respondent include having the researcher reveal some aspects of her own identity and story so that the interview is a more reciprocal experience rather than one-sided, allowing participants to view and edit interview transcripts before the researcher uses them for analysis, and giving participants an opportunity to read and comment on analysis before the researcher shares it with others through publication or presentation (Reinharz, 1992; Hesse-Biber, Nagy, & Leavy, 2007). On the other hand, some researchers suggest that sharing too much with interview participants can give the false impression there is no power differential, when in reality, researchers can analyze and present participants’ stories in whatever way they see fit (Stacey, 1988).

However you feel about sharing details about your background with an interview participant, another way to balance the power differential between yourself and your interview participants is to make the intent of your research very clear to the subjects. Share with them your rationale for conducting the research and the research question(s) that frame your work. Be sure that you also share with participants how the data you gather will be used and stored. Also, explain to participants how their confidentiality will be protected including who will have access to the data you gather from them and what procedures, such as using pseudonyms, you will take to protect their identities. Social workers also must disclose the reasons why confidentiality may be violated to prevent danger to self or others. Many of these details will be covered by your IRB’s informed consent procedures and requirements. However, even if they are not, as researchers we should be attentive to how informed consent can help balance the power differences between ourselves and those who participate in our research.

There are no easy answers when it comes to handling the power differential between the researcher and researched. Even social scientists do not agree on the best approach. Because qualitative research involves interpersonal interactions and building a relationship with research participants, power is a particularly important issue.

Location, location, location

One way to address the power between researcher and respondent is to conduct the interview in a location of the participant’s choosing, where they will feel most comfortable answering your questions. Interviews can take place in any number of locations—in respondents’ homes or offices, researchers’ homes or offices, coffee shops, restaurants, public parks, or hotel lobbies, to name just a few possibilities. Each location comes with its own set of benefits and its own challenges. Allowing the respondent to choose the location that is most convenient and most comfortable for them is important, but identifying a location where there will be few distractions is helpful. For example, some coffee shops and restaurants are so loud that recording the interview can be a challenge. Other locations may present different sorts of distractions. For example, if you conduct interviews with parents in their home, they may out of necessity spend more time attending to their children during an interview than responding to your questions (of course, depending on the topic of your research, the opportunity to observe such interactions could be invaluable). As an interviewer, you may want to suggest a few possible locations, and note the goal of avoiding distractions, when you ask your respondents to choose a location.

The extent to which a respondent has control over choosing a location must also be balanced by accessibility of the location to the interviewer, and by the safety and comfort level with the location. You may not feel comfortable conducting an interview in an area with posters for hate groups on the wall. Not only might you fear for your safety, you may be too distracted to conduct a good interview. While it is important to conduct interviews in a location that is comfortable for respondents, doing so should never come at the expense of your safety.

Researcher-Participant rapport

A unique feature of interviews is that they require some social interaction, which means that a relationship is formed between interviewer and interviewee. One essential element in building a productive relationship is respect. You should respect the person’s time and their story. Demonstrating respect will help interviewees feel comfortable sharing with you.

There are no big secrets or tricks for how to show respect for research participants. At its core, the interview interaction should not differ from any other social interaction in which you show gratitude for a person’s time and respect for a person’s humanity. It is crucial that you, as the interviewer, conduct the interview in a way that is culturally sensitive. In some cases, this might mean educating yourself about your study population and even receiving some training to help you learn to effectively communicate with your research participants. Do not judge your research participants; you are there to listen to them, and they have been kind enough to give you their time and attention. Even if you disagree strongly with what a participant shares in an interview, your job as the researcher is to gather the information being shared with you, not to make personal judgments about it. Respect provides a solid foundation for rapport.

Rapport is the sense of connection you establish with a participant. Developing good rapport requires good listening. In fact, listening during an interview is an active, not a passive, practice. Active listening means that you, the researcher, participate with the respondent by showing you understand and follow whatever it is that they are telling you (Devault, 1990). The questions you ask respondents should indicate you’ve actually heard what they’ve just said.

Active listening means you will probe the respondent for more information from time to time throughout the interview. A probe is a request for more information. Probes are used because qualitative interviewing techniques are designed to go with the flow and take whatever direction the respondent goes during the interview. It is worth your time to come up with helpful probes in advance of an interview. You certainly do not want to find yourself stumped or speechless after a respondent has just said something about which you’d like to hear more. This is another reason why practicing your interview in advance with people who are similar to those in your sample is a good idea.

The responsibilities that a social work clinician has to clients differ significantly from a researcher’s responsibilities. Clinicians provide services whereas researchers do not. A research participant is not your client, and your goals for the interaction are different from those of a clinical relationship.

Key Takeaways

- Interviewers should take into consideration the power differential between themselves and their respondents.

- Feminist researchers paved the way for helping interviewers think about how to balance the power differential between themselves and interview participants.

- Attend to the location of an interview and the relationship that forms between the interviewer and interviewee.

- Interviewers should always be respectful of interview participants.

Glossary

- Probe- a request for more information in qualitative research

9.4 Types of qualitative research designs

Learning Objectives

- Define focus groups and outline how they differ from one-on-one interviews

- Describe how to determine the best size for focus groups

- Identify the important considerations in focus group composition

- Discuss how to moderate focus groups

- Identify the strengths and weaknesses of focus group methodology

- Describe case study research, ethnography, and phenomenology.

There are various types of approaches to qualitative research. This chapter presents information about focus groups, which are often used in social work research. It also introduces case studies, ethnography, and phenomenology.

Focus Groups

Focus groups resemble qualitative interviews in that a researcher may prepare a guide in advance and interact with participants by asking them questions. But anyone who has conducted both one-on-one interviews and focus groups knows that each is unique. In an interview, usually one member (the research participant) is most active while the other (the researcher) plays the role of listener, conversation guider, and question-asker. Focus groups, on the other hand, are planned discussions designed to elicit group interaction and “obtain perceptions on a defined area of interest in a permissive, nonthreatening environment” (Krueger & Casey, 2000, p. 5). In focus groups, the researcher play a different role than in a one-on-one interview. The researcher’s aim is to get participants talking to each other, to observe interactions among participants, and moderate the discussion.

There are numerous examples of focus group research. In their 2008 study, for example, Amy Slater and Marika Tiggemann (2010) conducted six focus groups with 49 adolescent girls between the ages of 13 and 15 to learn more about girls’ attitudes towards’ participation in sports. In order to get focus group participants to speak with one another rather than with the group facilitator, the focus group interview guide contained just two questions: “Can you tell me some of the reasons that girls stop playing sports or other physical activities?” and “Why do you think girls don’t play as much sport/physical activity as boys?” In another focus group study, Virpi Ylanne and Angie Williams (2009) held nine focus group sessions with adults of different ages to gauge their perceptions of how older characters are represented in television commercials. Among other considerations, the researchers were interested in discovering how focus group participants position themselves and others in terms of age stereotypes and identities during the group discussion. In both examples, the researchers’ core interest in group interaction could not have been assessed had interviews been conducted on a one-on-one basis, making the focus group method an ideal choice.

Who should be in your focus group?

In some ways, focus groups require more planning than other qualitative methods of data collection, such as one-on-one interviews in which a researcher may be better able to the dialogue. Researchers must take care to form focus groups with members who will want to interact with one another and to control the timing of the event so that participants are not asked nor expected to stay for a longer time than they’ve agreed to participate. The researcher should also be prepared to inform focus group participants of their responsibility to maintain the confidentiality of what is said in the group. But while the researcher can and should encourage all focus group members to maintain confidentiality, she should also clarify to participants that the unique nature of the group setting prevents her from being able to promise that confidentiality will be maintained by other participants. Once focus group members leave the research setting, researchers cannot control what they say to other people.

Group size should be determined in part by the topic of the interview and your sense of the likelihood that participants will have much to say without much prompting. If the topic is one about which you think participants feel passionately and will have much to say, a group of 3–5 could make sense. Groups larger than that, especially for heated topics, can easily become unmanageable. Some researchers say that a group of about 6–10 participants is the ideal size for focus group research (Morgan, 1997); others recommend that groups should include 3–12 participants (Adler & Clark, 2008). The size of the focus group is ultimately the decision of the researcher. When forming groups and deciding how large or small to make them, take into consideration what you know about the topic and participants’ potential interest in, passion for, and feelings about the topic. Also consider your comfort level and experience in conducting focus groups. These factors will help you decide which size is right in your particular case.

It may seem counterintuitive, but in general, it is better to form focus groups consisting of participants who do not know one another than to create groups consisting of friends, relatives, or acquaintances (Agar & MacDonald, 1995). The reason is that group members who know each other may not share some taken-for-granted knowledge or assumptions. In research, it is precisely the taken-for-granted knowledge that is often of interest; thus, the focus group researcher should avoid setting up interactions where participants may be discouraged to question or raise issues that they take for granted. However, group members should not be so different from one another that participants will be unlikely to feel comfortable talking with one another.

Focus group researchers must carefully consider the composition of the groups they put together. In his text on conducting focus groups, Morgan (1997) suggests that “homogeneity in background and not homogeneity in attitudes” (p. 36) should be the goal, since participants must feel comfortable speaking up but must also have enough differences to facilitate a productive discussion. Whatever composition a researcher designs for her focus groups, the important point to keep in mind is that focus group dynamics are shaped by multiple social contexts (Hollander, 2004). Participants’ silences as well as their speech may be shaped by gender, race, class, sexuality, age, or other background characteristics or social dynamics—all of which might be suppressed or exacerbated depending on the composition of the group. Hollander (2004) suggests that researchers must pay careful attention to group composition, must be attentive to group dynamics during the focus group discussion, and should use multiple methods of data collection in order to “untangle participants’ responses and their relationship to the social contexts of the focus group” (p. 632).

The role of the moderator

In addition to the importance of group composition, focus groups also require skillful moderation. A moderator is the researcher tasked with facilitating the conversation in the focus group. Participants may ask each other follow-up questions, agree or disagree with one another, display body language that tells us something about their feelings about the conversation, or even come up with questions not previously conceived of by the researcher. It is just these sorts of interactions and displays that are of interest to the researcher. A researcher conducting focus groups collects data on more than people’s direct responses to her question, as in interviews.

The moderator’s job is not to ask questions to each person individually, but to stimulate conversation between participants. It is important to set ground rules for focus groups at the outset of the discussion. Remind participants you’ve invited them to participate because you want to hear from all of them. Therefore, the group should aim to let just one person speak at a time and avoid letting just a couple of participants dominate the conversation. One way to do this is to begin the discussion by asking participants to briefly introduce themselves or to provide a brief response to an opening question. This will help set the tone of having all group members participate. Also, ask participants to avoid having side conversations; thoughts or reactions to what is said in the group are important and should be shared with everyone.

As the focus group gets rolling, the moderator will play a less active role as participants talk to one another. There may be times when the conversation stagnates or when you, as moderator, wish to guide the conversation in another direction. In these instances, it is important to demonstrate that you’ve been paying attention to what participants have said. Being prepared to interject statements or questions such as “I’d really like to hear more about what Sunil and Joe think about what Dominick and Jae have been saying” or “Several of you have mentioned X. What do others think about this?” will be important for keeping the conversation going. It can also help redirect the conversation, shift the focus to participants who have been less active in the group, and serve as a cue to those who may be dominating the conversation that it is time to allow others to speak. Researchers may choose to use multiple moderators to make managing these various tasks easier.

Moderators are often too busy working with participants to take diligent notes during a focus group. It is helpful to have a note-taker who can record participants’ responses (Liamputtong, 2011). The note-taker creates, in essence, the first draft of interpretation for the data in the study. They note themes in responses, nonverbal cues, and other information to be included in the analysis later on. Focus groups are analyzed in a similar way as interviews; however, the interactive dimension between participants adds another element to the analytical process. Researchers must attend to the group dynamics of each focus group, as “verbal and nonverbal expressions, the tactical use of humour, interruptions in interaction, and disagreement between participants” are all data that are vital to include in analysis (Liamputtong, 2011, p. 175). Note-takers record these elements in field notes, which allows moderators to focus on the conversation.

Strengths and weaknesses of focus groups

Focus groups share many of the strengths and weaknesses of one-on-one qualitative interviews. Both methods can yield very detailed, in-depth information; are excellent for studying social processes; and provide researchers with an opportunity not only to hear what participants say but also to observe what they do in terms of their body language. Focus groups offer the added benefit of giving researchers a chance to collect data on human interaction by observing how group participants respond and react to one another. Like one-on-one qualitative interviews, focus groups can also be quite expensive and time-consuming. However, there may be some savings with focus groups as it takes fewer group events than one-on-one interviews to gather data from the same number of people. Another potential drawback of focus groups, which is not a concern for one-on-one interviews, is that one or two participants might dominate the group, silencing other participants. Careful planning and skillful moderation on the part of the researcher are crucial for avoiding, or at least dealing with, such possibilities. The various strengths and weaknesses of focus group research are summarized in Table 91.

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

| Yield detailed, in-depth data | Expensive |

| Less time-consuming than one-on-one interviews | May be more time-consuming than survey research |

| Useful for studying social processes | Minority of participants may dominate entire group |

| Allow researchers to observe body language in addition to self-reports | Some participants may not feel comfortable talking in groups |

| Allow researchers to observe interaction between multiple participants | Cannot ensure confidentiality |

Grounded Theory

Grounded theory has been widely used since its development in the late 1960s (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Largely derived from schools of sociology, grounded theory involves emersion of the researcher in the field and in the data. Researchers follow a systematic set of procedures and a simultaneous approach to data collection and analysis. Grounded theory is most often used to generate rich explanations of complex actions, processes, and transitions. The primary mode of data collection is one-on-one participant interviews. Sample sizes tend to range from 20 to 30 individuals, sampled purposively (Padgett, 2016). However, sample sizes can be larger or smaller, depending on data saturation. Data saturation is the point in the qualitative research data collection process when no new information is being discovered. Researchers use a constant comparative approach in which previously collected data are analyzed during the same time frame as new data are being collected. This allows the researchers to determine when new information is no longer being gleaned from data collection and analysis — that data saturation has been reached — in order to conclude the data collection phase.

Rather than apply or test existing grand theories, or “Big T” theories, grounded theory focuses on “small t” theories (Padgett, 2016). Grand theories, or “Big T” theories, are systems of principles, ideas, and concepts used to predict phenomena. These theories are backed up by facts and tested hypotheses. “Small t” theories are speculative and contingent upon specific contexts. In grounded theory, these “small t” theories are grounded in events and experiences and emerge from the analysis of the data collected.

One notable application of grounded theory produced a “small t” theory of acceptance following cancer diagnoses (Jakobsson, Horvath, & Ahlberg, 2005). Using grounded theory, the researchers interviewed nine patients in western Sweden. Data collection and analysis stopped when saturation was reached. The researchers found that action and knowledge, given with respect and continuity led to confidence which led to acceptance. This “small t” theory continues to be applied and further explored in other contexts.

Case study research

Case study research is an intensive longitudinal study of a phenomenon at one or more research sites for the purpose of deriving detailed, contextualized inferences and understanding the dynamic process underlying a phenomenon of interest. Case research is a unique research design in that it can be used in an interpretive manner to build theories or in a positivist manner to test theories. The previous chapter on case research discusses both techniques in depth and provides illustrative exemplars. Furthermore, the case researcher is a neutral observer (direct observation) in the social setting rather than an active participant (participant observation). As with any other interpretive approach, drawing meaningful inferences from case research depends heavily on the observational skills and integrative abilities of the researcher.

Ethnography

The ethnographic research method, derived largely from the field of anthropology, emphasizes studying a phenomenon within the context of its culture. The researcher must be deeply immersed in the social culture over an extended period of time (usually 8 months to 2 years) and should engage, observe, and record the daily life of the studied culture and its social participants within their natural setting. The primary mode of data collection is participant observation, and data analysis involves a “sense-making” approach. In addition, the researcher must take extensive field notes, and narrate her experience in descriptive detail so that readers may experience the same culture as the researcher. In this method, the researcher has two roles: rely on her unique knowledge and engagement to generate insights (theory), and convince the scientific community of the trans-situational nature of the studied phenomenon.

The classic example of ethnographic research is Jane Goodall’s study of primate behaviors, where she lived with chimpanzees in their natural habitat at Gombe National Park in Tanzania, observed their behaviors, interacted with them, and shared their lives. During that process, she learnt and chronicled how chimpanzees seek food and shelter, how they socialize with each other, their communication patterns, their mating behaviors, and so forth. A more contemporary example of ethnographic research is Myra Bluebond-Langer’s (1996)14 study of decision making in families with children suffering from life-threatening illnesses, and the physical, psychological, environmental, ethical, legal, and cultural issues that influence such decision-making. The researcher followed the experiences of approximately 80 children with incurable illnesses and their families for a period of over two years. Data collection involved participant observation and formal/informal conversations with children, their parents and relatives, and health care providers to document their lived experience.

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is a research method that emphasizes the study of conscious experiences as a way of understanding the reality around us. Phenomenology is concerned with the systematic reflection and analysis of phenomena associated with conscious experiences, such as human judgment, perceptions, and actions, with the goal of (1) appreciating and describing social reality from the diverse subjective perspectives of the participants involved, and (2) understanding the symbolic meanings (“deep structure”) underlying these subjective experiences. Phenomenological inquiry requires that researchers eliminate any prior assumptions and personal biases, empathize with the participant’s situation, and tune into existential dimensions of that situation, so that they can fully understand the deep structures that drives the conscious thinking, feeling, and behavior of the studied participants.

Some researchers view phenomenology as a philosophy rather than as a research method. In response to this criticism, Giorgi and Giorgi (2003) developed an existential phenomenological research method to guide studies in this area. This method can be grouped into data collection and data analysis phases. In the data collection phase, participants embedded in a social phenomenon are interviewed to capture their subjective experiences and perspectives regarding the phenomenon under investigation. Examples of questions that may be asked include “can you describe a typical day” or “can you describe that particular incident in more detail?” These interviews are recorded and transcribed for further analysis. During data analysis, the researcher reads the transcripts to: (1) get a sense of the whole, and (2) establish “units of significance” that can faithfully represent participants’ subjective experiences. Examples of such units of significance are concepts such as “felt space” and “felt time,” which are then used to document participants’ psychological experiences. For instance, did participants feel safe, free, trapped, or joyous when experiencing a phenomenon (“felt-space”)? Did they feel that their experience was pressured, slow, or discontinuous (“felt-time”)? Phenomenological analysis should take into account the participants’ temporal landscape (i.e., their sense of past, present, and future), and the researcher must transpose herself in an imaginary sense in the participant’s situation (i.e., temporarily live the participant’s life). The participants’ lived experience is described in form of a narrative or using emergent themes. The analysis then delves into these themes to identify multiple layers of meaning while retaining the fragility and ambiguity of subjects’ lived experiences.

Key Takeaways

- In terms of focus group composition, homogeneity of background among participants is recommended while diverse attitudes within the group are ideal.

- The goal of a focus group is to get participants to talk with one another rather than the researcher.

- Like one-on-one qualitative interviews, focus groups can yield very detailed information, are excellent for studying social processes, and provide researchers with an opportunity to observe participants’ body language; they also allow researchers to observe social interaction.

- Focus groups can be expensive and time-consuming, as are one-on-one interviews; there is also the possibility that a few participants will dominate the group and silence others in the group.

- Other types of qualitative research include case studies, ethnography, and phenomenology.

Glossary

- Data saturation – the point in the qualitative research data collection process when no new information is being discovered

- Focus groups- planned discussions designed to elicit group interaction and “obtain perceptions on a defined area of interest in a permissive, nonthreatening environment” (Krueger & Casey, 2000, p. 5)

- Moderator- the researcher tasked with facilitating the conversation in the focus group

9.5 Spotlight on UTA School of Social Work

Dr. Genevieve GrAaf conducts research using interviews and focus groups

As a mental health policy researcher, interviews and focus groups are a critical technique that Dr. Genevieve Graaf of the University of Texas at Arlington’s School of Social Work uses to understand policy making processes and decisions, as well as the intricacies of mental health policy itself. These research tools enable the collection of information that is not readily or easily available, or can help to provide explanation, context, or clarification for information that is public knowledge.

In her most recent study, Dr. Graaf interviewed and conducted focus groups with children’s mental health administrators and policy makers in 32 different states. These interviews focused on understanding how each state organized and funded home and community-based mental health services for children and adolescents with significant emotional or behavioral disorders. Information was also gathered about the historical, political, and financial factors that shaped state approaches to addressing the needs of this population.

In smaller states, interviews were conducted with one policy informant, due to the small scope of the mental health administration. However, in some larger and more complex states, where policy makers collaborated across a variety of departments—child and family services, Medicaid administrations, juvenile justice divisions—focus groups were required to hear the shared perspectives and information available through a variety of stakeholders. Dr. Graaf used semi-structured interviews in which a set of topics and questions included on the interview protocol guided the discussion, but participants were able to change topics, move through topics out of the planned order, and offer information on topics not included in the interview protocol. This allowed for data collection to be comprehensive but also include the depth of nuanced and minor details relevant to aims of the study.

By collecting detailed data directly from knowledgeable informants who are involved in state mental health policy making on a daily basis, these interviews and focus groups provide in-depth illustrations of the variation in mental health policy making, mental health administrations, and the financial and governmental structures that exist across and between states. This type of knowledge can be shared among policy makers across states and nations as inspiration and lessons learned about best practices in the funding and organization of mental health care for children. After completing these interviews and focus groups, and analyzing the data, findings from these interviews and focus groups have been reported in three peer-reviewed journal articles (see for example, Graaf & Snowden, 2019) presented at conferences filled with state mental health policy makers, and shared directly with the state mental health policy makers who participated in the study. Many participants, when interviewed, asked to see the final report because they were very interested to learn about the practices and strategies used in other states.

The in-depth information collected through these interviews and focus groups can also help to advance further research about the accessibility, effectiveness, and quality of mental health services for children and their families by providing detailed contexts in which to examine further questions. For example, Dr. Graaf used interview and focus group findings to shape her approach to analyzing national quantitative data and enhanced her understanding of those quantitative findings. Factors that informants reported as shaping their decision making around their children’s mental health policies were used as control variables in her statistical models. Also, findings that were unexpected or surprising could be partially explained by variations across state mental health systems that were reported in interviews and captured through focus groups.

9.6 Analyzing qualitative data

Learning Objectives

- Describe how to transcribe qualitative data

- Identify and describe the two types of coding in qualitative research

- Assess the rigor of qualitative analysis using the criteria of trustworthiness and authenticity

Analysis of qualitative data typically begins with a set of transcripts of the interviews or focus groups conducted. Obtaining these transcripts requires having either taken exceptionally good notes or, preferably, having recorded the interview or focus group and then transcribed it. Researchers create a complete written copy, or transcript, of the recording by playing it back and typing in each word that is spoken, noting who spoke which words. In general, it is best to aim for a verbatim transcript, one that reports word for word exactly what was said in the recording. If possible, it is also best to include nonverbals in a transcript. Gestures made by participants should be noted, as should the tone of voice and notes about when, where, and how spoken words may have been emphasized by participants. Because these are difficult to capture via audio, it is important to have a note-taker in focus groups or to write useful field notes during interviews.

The goal of qualitative data analysis is to reach some inferences, lessons, or conclusions by condensing large amounts of data into relatively smaller, more manageable bits of understandable information. Analysis of qualitative data often works inductively (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Charmaz, 2006). To move from the specific observations a researcher collects to identifying patterns across those observations, qualitative researchers will often begin by reading through transcripts and trying to identify codes. A code is a shorthand representation of some more complex set of issues or ideas.

Qualitative researcher and textbook author Kristin Esterberg (2002) describes coding as a multistage process. To analyze qualitative data, one can begin by open coding transcripts. This means that you read through each transcript, line by line, and make a note of whatever categories or themes jump out to you. Open coding will probably require multiple rounds. That is, you will read through all of your transcripts multiple times. Once you have completed a few passes and started noticing commonalities, you might begin focused coding. In focused coding a final list of codes is identified from the results of the open coding. Once you come up with a final list of codes, make sure each one has a definition that clearly spells out what the code means. Finally, the dataset is recoded using the final list of codes, making sure to apply the definition of the code consistently throughout each transcript.

Using multiple researchers to code the same dataset can be quite helpful. You may miss something a participant said that another coder catches. Similarly, you may shift your understanding of what a code means and not realize it until another coder asks you about it. If multiple researchers are coding the dataset simultaneously, researchers must come to a consensus about the meaning of each code and ensure that codes are applied consistently by each researcher. We discussed this previously in Chapter 5 as inter-rater reliability. Even if only one person will code the dataset, it is important to work with other researchers. If other researchers have the time, you may be able to have them check your work for trustworthiness and authenticity, which are discussed in detail below.

Table 13.2, presents two codes that emerged from an inductive analysis of transcripts from interviews with child-free adults. It also includes a brief description of each code and a few (of many) interview excerpts from which each code was developed.

| Code | Code definition | Interview excerpts |

| Reify Gender | Participants reinforce heteronormative ideals in two ways: (a) by calling up stereotypical images of gender and family and (b) by citing their own “failure” to achieve those ideals. | “The woman is more involved with taking care of the child. [As a woman] I’d be the one waking up more often to feed the baby and more involved in the personal care of the child, much more involved. I would have more responsibilities than my partner. I know I would feel that burden more than if I were a man.” |

| “I don’t have that maternal instinct.” | ||

| “I look at all my high school friends on Facebook, and I’m the only one who isn’t married and doesn’t have kids. I question myself, like if there’s something wrong with me that I don’t have that.” | ||

| “I feel badly that I’m not providing my parents with grandchildren.” | ||

| Resist Gender | Participants resist gender norms in two ways: (a) by pushing back against negative social responses and (b) by redefining family for themselves in a way that challenges normative notions of family. | “Am I less of a woman because I don’t have kids? I don’t think so!” |

| “I think if they’re gonna put their thoughts on me, I’m putting it back on them. When they tell me, ‘Oh, Janet, you won’t have lived until you’ve had children. It’s the most fulfilling thing a woman can do!’ then I just name off the 10 fulfilling things I did in the past week that they didn’t get to do because they have kids.” | ||

| “Family is the group of people that you want to be with. That’s it.” |

As you might imagine, wading through all these data is quite a process. Just as quantitative researchers rely on the assistance of special computer programs designed to help with sorting through and analyzing their data, so too do qualitative researchers. There are programs specifically designed to assist qualitative researchers with organizing, managing, sorting, and analyzing large amounts of qualitative data. The programs work by allowing researchers to import transcripts contained in an electronic file and then label or code passages, cut and paste passages, search for various words or phrases, and organize complex interrelationships among passages and codes. They even include advanced features that allow researchers to code multimedia files, visualize relationships between a network of codes, and count the number of times a code was applied.

Trustworthiness and authenticity

In qualitative research, the standards for analysis quality differ than quantitative research for an important reason. Analysis in quantitative research can be done objectively or impartially. The researcher chooses a statistical analysis based on the research questions and data, and reads the results. The extent to which the results are accurate and consistent is a problem with the data, not the researcher.

The same cannot be said for qualitative research. Qualitative researchers are deeply involved in the data analysis process. There is no external measurement tool, like a quantitative scale. Rather, the researcher herself is the measurement instrument. Researchers build connections between different ideas that participants discuss and draft an analysis that accurately reflects the depth and complexity of what participants have said. This is a challenging task for a researcher. It involves acknowledging her own biases, either from personal experience or previous knowledge about the topic, and allowing the meaning that participants shared to emerge as the data is analyzed. It’s not necessarily about being objective, as there is always some subjectivity in qualitative analysis, but more about the rigor with which the individual researcher engages in data analysis.

For this reason, researchers speak of rigor in more personal terms. Trustworthiness refers to the “truth value, applicability, consistency, and neutrality” of the results of a research study (Rodwell, 1998, p. 96). Authenticity refers to the degree to which researchers capture the multiple perspectives and values of participants in their study and foster change across participants and systems during their analysis. Both trustworthiness and authenticity contain criteria that help a researcher gauge the rigor with which the results were obtained.

Most analogous to the quantitative concepts of validity and reliability are qualitative research’s trustworthiness criteria of credibility, dependability, and confirmability. Credibility refers to the degree to which the results are accurate and viewed as important and believable by participants. Qualitative researchers will often check with participants before finalizing and publishing their results to make sure participants agree with them. They may also seek out assistance from another qualitative researcher to review or audit their work. As you might expect, it’s difficult to view your own research without bias, so another set of eyes is often helpful. Unlike in quantitative research, the ultimate goal is not to find the Truth (with a capital T) using a predetermined measure, but to create a credible interpretation of the data. Credibility is seen as akin to validity, as it mainly speaks to the accuracy of the research product.

The criterion of dependability, on the other hand, is similar to reliability. As you may recall, reliability is the consistency of a measure (if you give the same measure each time, you should get similar results). However, qualitative research questions, hypotheses, and interview questions may change during the research process. How can one achieve reliability under such conditions? Because qualitative research understands the importance of context, it would be impossible to control all of the things that would make a qualitative measure the same when you give it to each person. The location, timing, or even the weather can and do influence participants to respond differently. Therefore, qualitative researchers assess dependability rather than reliability. Dependability ensures that proper qualitative procedures were followed and that any changes that emerged during the research process are accounted for, justified, and described in the final report. Researchers should document changes to their methodology and the justification for them in a journal or log. In addition, researchers may again use another qualitative researcher to examine their logs and results to ensure dependability.

Finally, the criterion of confirmability refers to the degree to which the results reported are linked to the data obtained from participants. While it is possible that another researcher could view the same data and come up with a different analysis, confirmability ensures that a researcher’s results are actually grounded in what participants said. Another researcher should be able to read the results of your study and trace each point made back to something specific that one or more participants shared. This process is called an audit.

The criteria for trustworthiness were created as a reaction to critiques of qualitative research as unscientific (Guba, 1990). They demonstrate that qualitative research is equally as rigorous as quantitative research. Subsequent scholars conceptualized the dimension of authenticity without referencing the standards of quantitative research at all. Instead, they wanted to understand the rigor of qualitative research on its own terms.

While there are multiple criteria for authenticity, the one that is most important for undergraduate social work researchers to understand is fairness. Fairness refers to the degree to which “different constructions, perspectives, and positions are not only allowed to emerge, but are also seriously considered for merit and worth” (Rodwell, 1998, p. 107). Qualitative researchers, depending on their design, may involve participants in the data analysis process, try to equalize power dynamics among participants, and help negotiate consensus on the final interpretation of the data. As you can see from the talk of power dynamics and consensus-building, authenticity attends to the social justice elements of social work research.

Key Takeaways

- Open coding involves allowing codes to emerge from the dataset.

- Codes must be clearly defined before focused coding can begin, so the researcher applies them in the same way to each unit of data.

- The criteria that qualitative researchers use to assess rigor are trustworthiness and authenticity.

Glossary

- Authenticity- the degree to which researchers capture the multiple perspectives and values of participants in their study and foster change across participants and systems during their analysis

- Code- a shorthand representation of some more complex set of issues or ideas

- Coding- identifying themes across qualitative data by reading transcripts

- Confirmability- the degree to which the results reported are linked to the data obtained from participants

- Credibility- the degree to which the results are accurate and viewed as important and believable by participants

- Dependability- ensures that proper qualitative procedures were followed and that any changes that emerged during the research process are accounted for, justified, and described in the final report

- Fairness- the degree to which “different constructions, perspectives, and positions are not only allowed to emerge, but are also seriously considered for merit and worth” (Rodwell, 1998, p. 107)

- Focused coding- collapsing or narrowing down codes, defining codes, and recoding each transcript using a final code list

- Open coding- reading through each transcript, line by line, and make a note of whatever categories or themes seem to jump out to you

- Transcript- a complete, written copy of the recorded interview or focus group containing each word that is spoken on the recording, noting who spoke which words

- Trustworthiness- the “truth value, applicability, consistency, and neutrality” of the results of a research study (Rodwell, 1998, p. 96)